Abstract

Introduction:

Despite increasing evidence of the benefits of spiritual care and nurses' efforts to incorporate spiritual interventions into palliative care and clinical practice, the role of spirituality is not well understood and implemented. There are divergent meanings and practices within and across countries. Understanding the delivery of spiritual interventions may lead to improved patient outcomes.

Aim:

We conducted a systematic review to characterize spiritual interventions delivered by nurses and targeted outcomes for patients in hospitals or assisted long-term care facilities.

Methodology:

The systematic review was developed following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, and a quality assessment was performed. Our protocol was registered on PROSPERO (Registration No. CRD42020197325). The CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed databases were searched from inception to June 2020.

Results:

We screened a total of 1005 abstracts and identified 16 experimental and quasi-experimental studies of spiritual interventions delivered by nurses to individuals receiving palliative care or targeted at chronic conditions, such as advanced cancer diseases. Ten studies examined existential interventions (e.g., spiritual history, spiritual pain assessment, touch, and psychospiritual interventions), two examined religious interventions (e.g., prayer), and four investigated mixed interventions (e.g., active listening, presence, and connectedness with the sacred, nature, and art). Patient outcomes associated with the delivery of spiritual interventions included spiritual well-being, anxiety, and depression.

Conclusion:

Spiritual interventions varied with the organizational culture of institutions, patients' beliefs, and target outcomes. Studies showed that spiritual interventions are associated with improved psychological and spiritual patient outcomes. The studies' different methodological approaches and the lack of detail made it challenging to compare, replicate, and validate the applicability and circumstances under which the interventions are effective. Further studies utilizing rigorous methods with operationalized definitions of spiritual nursing care are recommended.

Keywords: nursing care, palliative care, patient outcome assessment, spirituality, spiritual therapies, systematic review

Introduction

Spiritual care is a growing field of health care and has been associated with various health outcomes.1 Multiple studies have documented the benefits of spiritual interventions, including reduced anxiety and depression,1–4 enhanced well-being,5,6 improved life satisfaction,7 increased quality of life,8 and reduced spiritual distress for patients near death.9

Most Americans (75%) report spirituality is at least somewhat important, and 53% describe it as crucial for their lives.10 Existing evidence suggests that patients become more involved with religious practices in clinical settings and a sense of spirituality magnifies with age11 or when a patient is faced with the uncertainty of events, such as dealing with serious illness or an incurable illness amenable to palliative care. In this way, spiritual interventions deserve further investigation about their applicability across clinical settings and diverse care (e.g., oncology, long-term care, and palliative care) for the seriously ill.12

In delivering spiritual interventions, a discussion about the meaning of spirituality for religious and nonreligious can emerge. Spirituality defines a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity, gives meaning and purpose to life through which individuals seek to experience relationships to self, others, nature, or sacred.13 Spirituality is patient- and family-centered care,13 recognizing the spiritual part of an individual's life.14 According to Paloutzian and Ellison's15 framework, spiritual interventions are usually described as having a religious focus (religious practices organized by individuals who share the same belief for achieving harmony with God) or existential focus (meaning and purpose in one's life).

The scope of nursing practice provides a natural context for spiritual interventions to be delivered to support patients in confronting existential types of questions related to the meaning of life, pain, agony, and death.16,17 Nurses are searching for ways to incorporate spiritual care and alternative therapies based on patients' beliefs into clinical practice to improve their quality of life.18 In fact, the American Holistic Nurses Association describes the holistic nursing practice as focusing on whole-person care that naturally embraces the spiritual dimensions.19 In 2012, the American Nurses Association recognized that nurses provide spiritual interventions focused on presence, guidance, nurturing, or encouraging an individual's or group's ability to achieve personal, spiritual, and social well-being and integrate body, mind, and spirit.20

Across the world, spiritual care is also a growing topic of interest in health care organizations.21 The International Council of Nurses describes nursing care as compassionate and ethical caring that addresses patients' spiritual needs.22 Although nurses' delivery of spiritual interventions is recognized and advocated by different national and international associations, the role of spirituality in nursing practice is not well understood and has divergent meanings and practices within and across countries.

A meta-analysis23 and systematic review24 revealed positive effects of spiritual interventions on spiritual well-being and quality of life of patients with serious illnesses. In these studies, health care professionals delivering such interventions were limited to psychotherapists, chaplains, and multidisciplinary teams. Unfortunately, a psychotherapist's presence might not always be possible in the context of usual clinical practice.25 Nurses are often the first point of reference for individuals in suffering. Being at the front line of care, nurses spend the greatest amount of time with patients26 among health care providers and can offer spiritual interventions as part of their work. Therefore, nurses must be equipped to respond to patients' needs appropriately in diverse settings and contexts. Across the published reviews, our systematic review presents evidence of nurses' delivery of spiritual interventions and their impact on patient outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review was developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see online Supplementary Material).27 Our protocol was registered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=197325). In our review, we sought to answer the following research questions: What studies on nurse-led spiritual interventions for patients hospitalized or institutionalized in long-term care facilities have been conducted? and What is the impact of the spiritual interventions delivered by nurses on patients' quality of life, including physical, psychological, social, and spiritual outcomes?

Data sources and search strategy

To answer the research questions, our team, with the assistance of a librarian with nursing expertise, developed the search strategy, including a comprehensive set of keywords and terms, and searched the databases. Details on the search strategies are presented in Table 1. We conducted a literature search on June 28, 2020, in the databases CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed. The database-specific searches utilized combinations of the following terms: spirituality, existential needs, religious, transcendent, life purpose, nurse-led, nursing, experiment, controlled trial, and randomized studies. We filtered for adult and older patients and English-language publications. The records identified through the searches in each database were downloaded into a reference management program (EndNote version X9). In addition, we analyzed reference lists of included studies as supplementary sources.

Table 1.

Search Strategy by Database

| Database | Search | Number of records |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (Spiritu*[Text Word] OR “Existential needs” [Text Word] OR “Existential need” [Text Word] OR Relig*[Text Word] OR Faith [Text Word] OR “Transcenden*” [Text Word] OR “Life Purpose” [Text Word]) AND (“Nurse-led”[Title/Abstract] OR Nursing [Mesh] OR “Nurs*” [Text Word] OR BSN[Text Word] OR APN[Text Word) AND (experiment* OR “controlled stud*” OR “controlled trial “ OR “control group” OR “comparison group “ OR quasi OR randomized OR randomly OR “before and after stud* “ OR “pretest post* “) |

269 |

| CINAHL | (“Spiritu*” OR “Existential need*” OR “Relig*” OR “Faith” OR “Transcenden*” OR “Life Purpose”) AND (“Nurse-led” OR “Nursing” OR “Nurs*” OR “BSN” OR “APN”) AND (experiment* OR “controlled stud* “ OR “controlled trial “ OR “control group” OR “comparison group “ OR quasi OR randomized OR randomly OR “before and after stud* “ OR “pretest post*”) |

248 |

| PsycINFO | (“Spiritu*” OR “Existential need*” OR “Relig*” OR “Faith” OR “Transcenden*” OR “Life Purpose”) AND (“Nurse-led” OR “Nursing” OR “Nurs*” OR “BSN” OR “APN”) AND (experiment* OR “controlled stud* “ OR “controlled trial “ OR “control group” OR “comparison group” OR quasi OR randomized OR randomly OR “before and after stud* “ OR “pretest post*”) |

274 |

| Embase | (‘spiritu*’ OR ‘existential need*’ OR ‘relig*’ OR ‘faith’/exp OR ‘transcenden*’ OR ‘life purpose’) AND (‘nursing’/exp OR ‘nurs*/exp’ OR ‘bsn’ OR ‘apn’ OR ‘nurse-led’) AND (‘experiment*’ OR ‘controlled stud*’ OR ‘controlled trial’/exp OR ‘control group’/exp OR ‘comparison group’ OR ‘quasi’ OR ‘randomized’ OR ‘randomly’ OR ‘pretest post*’) |

214 |

Filters applied: English. Adult/Older: 19–44 years, Middle aged: 45–64 years, Older aged: 65+ years.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible, included studies had to be either randomized controlled trials (RCT) or quasi-experimental studies that assessed outcomes preintervention and post-intervention or through a control group comparison. Eligible participants were adults (18 years of age or older), hospitalized or resided in an assisted living nursing facility or a nursing home during the study. Studies were required nurse-led spiritual interventions (existential, religious, or mixed) delivered to an individual or group through face-to-face interactions or the Internet. Studies used previously validated tools to measure patient outcomes before and after the intervention or comparison/control groups. Included studies had to be peer-reviewed publications written in English, with no date limits.

We excluded studies that involved spiritual interventions delivered to caregivers or family members, educational interventions for health care professionals or nurses that did not measure patient outcomes, and spiritual interventions delivered in patients' homes, community centers, and dwelling communities. We excluded team interventions provided by the nurse and at least one non-nursing colleague (e.g., chaplain, physician, or psychologist) because we are interested in exploring nurses' participation in spiritual care. Other exclusion criteria included case studies, descriptive studies, editorials, books, reports, letters, literature reviews, dissertations, commentaries, guidelines, protocols, or conference proceedings.

Abstract and full-text screening

A two-step process was employed for abstract and full-text screening. First, two reviewers (F.D.S. and O.O.M.) independently screened abstracts. In step 2, three reviewers (F.D.S., O.O.M., and S.H.) independently examined the full text of the remaining articles to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Inter-rater reliability scores for the abstract and full text reviews were 93% and 85%, respectively, with the consensus reached through discussion on disagreements. This process resulted in a final sample of 16 intervention studies.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extracted from the 16 studies included (1) author, year of publication, and country, (2) study purpose, (3) setting and design, (4) sample size and characteristics, (5) type of spiritual interventions: existential (holistic care and meaning in life), religious (the role of faith and prayer), or mixed (studies including holistic care and prayer or faith related to intervention), (6) scales, (7) study outcomes, and (8) results relevant to the spiritual interventions and outcomes under study. Data were extracted by one reviewer (F.D.S.) and verified for accuracy by the other two reviewers (O.O.M. and S.H.). Any disagreement was noted and resolved through discussion among all reviewers. The results were tabulated and reported, and narrative synthesis was used to group outcomes of interest to spirituality within the nursing context.

Quality assessment

The quality of studies was appraised using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Articles (QualSyst tool).28 Two reviewers (F.D.S. and S.H.) independently assessed the reproducibility of each study by scoring the 14 items under the following categories: research question, sample size, study design, data collection and recruitment strategy, statistical analyses, and results reported for appropriateness of each item. The agreement rate between reviewers was 81%, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

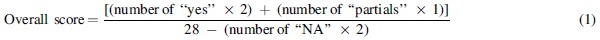

Scoring involved selecting one of four options reflecting the degree to which a study met each item: yes (2 points), partial (1 point), no (0), or NA (not applicable). The following equation calculated the overall score [Eq. (1)].

Details and instructions for the quality assessment scoring can be found elsewhere.28 Based on the overall score, we categorized the quality of each study as low if the overall score is below 60%, moderate if the overall score is between 60% and 79%, and high if it is above 80% (Table 2).29

Table 2.

General Quality Assessment Summary: Review Authors' Judgments for Each Study

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Overall score, % | Qualitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu and Koo7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 79 | Moderate |

| Kwan et al.31 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 86 | High |

| Ayyari et al.35 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 68 | Moderate |

| Mok et al.32 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 68 | Moderate |

| Stinson and Kirk40 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 | Moderate |

| Musarezaie et al.37 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 68 | Moderate |

| Babamohamadi et al.36 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 82 | High |

| Wang et al.33 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 71 | Moderate |

| Butts6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 61 | Moderate |

| Pramesona et al.34 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 71 | Moderate |

| Ichihara et al.25 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 71 | Moderate |

| Elham et al.3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 61 | Moderate |

| Alp and Yucel2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 68 | Moderate |

| Zhang et al.30 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 68 | Moderate |

| Carvalho et al.38 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 64 | Moderate |

| Vlasblom et al.39 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 68 | Moderate |

Studies were scored using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Articles developed by the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.28 Score: yes (2 points), partial (1 point), no (0 points), or NA (not applicable). Q1, question/objective; Q2, design; Q3, method of subject/comparison group; Q4, subject characteristics; Q5, intervention and random allocation; Q6, blinding of investigators; Q7, blinding of subjects; Q8, outcome(s)/robust measurement; Q9, sample size; Q10, analytic methods; Q11, estimate of variance (e.g., confidence intervals, standard errors); Q12, controlled for confounding; Q13, results reported; Q14, conclusions supported by the results.

Quality of each study as low if the overall score is below 60%, moderate if the overall score is between 60% and 79%, and high if it is above 80%.

Results

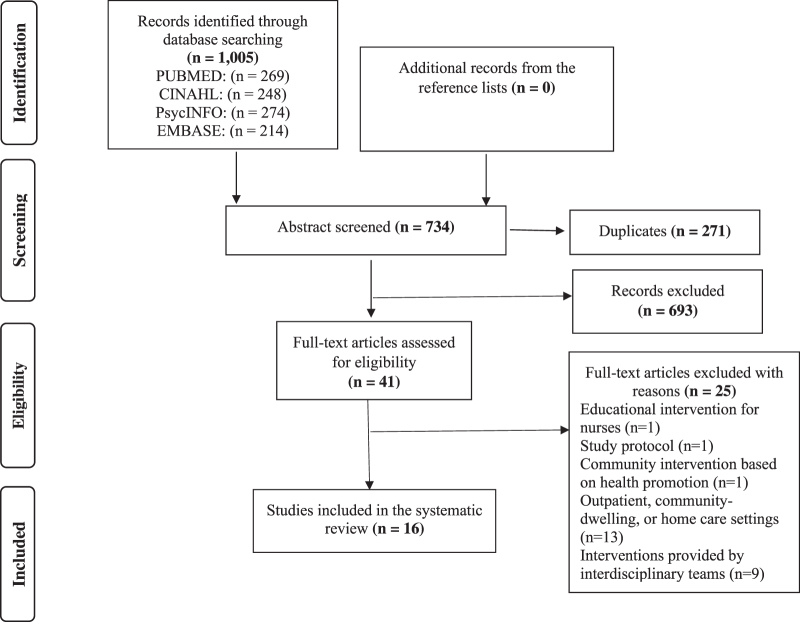

Through our comprehensive literature search, 1005 records were extracted from CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed. After the removal of duplicates, 734 unique records were identified. Through screening of titles and abstracts, 693 records were excluded. Forty-one full-text articles were assessed, resulting in 16 studies (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Characteristics of studies

Country

Ten countries were represented across the studies. Twelve of the 16 studies took place in China,30 Hong Kong,31,32 Turkey,2 Japan,25 Taiwan,7,33 Indonesia,34 and Iran.3,35–37 The remaining four were conducted in Brazil,38 Netherlands,39 and the United States.6,40

Setting and design

Ten studies3,7,25,30–32,36–39 were hospital-based investigations, and the remaining six2,6,33–35,40 were conducted in assisted living facilities or nursing homes. Of hospital-based interventions, six were conducted in palliative care or oncology wards.25,30–32,37,38 Nine6,7,31–33,35–37,40 studies were RCTs and seven2,3,25,30,34,38,39 were of quasi-experimental design.

Participant characteristics

Collectively, the studies included 1079 unique participants, who were primarily individuals with advanced cancer or in palliative care,25,30–32,37,38 suffering from cardiac diseases3,36 or diagnosed with dementia.7

Characteristics of spiritual nursing interventions

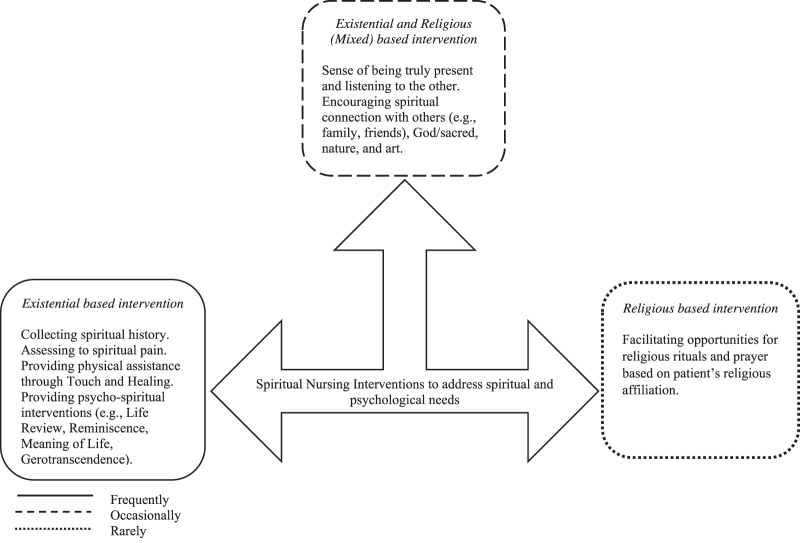

A wide variety of interventions were described. Building on Paloutzian and Ellison's framework,15 we used the study description of the spiritual intervention to categorize each into one of three main types: existential, religious, or mixed (Fig. 2). In studies, spiritual nursing interventions were delivered to improve the spiritual and mental health of patients. A brief description of each spiritual intervention category appears in the following section.

FIG. 2.

Frequency and nature of spiritual interventions provided by nurses to hospitalized patients or institutionalized in long-term care facilities based on intervention studies across countries.

Existential-based intervention (n = 10)

This category represented nursing interventions targeted at the whole person and expressed through meaning in life. These consisted of interventions that collect spiritual history,39 assess spiritual pain,25 provide physical assistance and comfort through touch and healing,2,6 or provide psychospiritual care focused on reminiscence,7,40 life review,30,31 meaning of life,32 gerotranscendence,33 and were delivered to a group or individually. For the group format, the group therapy was facilitated by nurses, in which nurses and patients provide each other with advice or support about handling specific spiritual or emotional distress, independent of religious affiliations. For individual format, nurses assessed patients' spiritual needs and delivered therapeutic touch and holistic care with close interaction between nurses and patients to enhance comfort, meaning, and purpose to their existence.

Religious-based intervention (n = 2)

These interventions34,38 were characterized by interactions between the nurse and an individual patient, including praying and reading religious passages from a patient's faith traditions and religious affiliations and other similar exchanges. In the prayer intervention, patients held hands with the nurse, praying the Psalm 138 of the Bible based on the Catholic religion.38 In another study, a preacher nurse following the Muslim spiritual practice delivered Qur'anic recitation, which patients listened to about their faith.34

Mixed intervention (existential and religious) (n = 4)

Studies were classified as both existential and religious if nursing interventions engaged patients' connections with oneself, environment, others, or God.3,35–37 An example of this type of intervention involves the nurse offering relaxing music and nature connections to encourage a positive attitude and hope and praying with the patient in their faith traditions (e.g., kneeling on a rug reciting passages from the Quran). This type of intervention commonly provides active listening and a supportive presence for patients.

Patient outcomes

We categorized patient outcomes across studies under well-being and human spirituality, and psychological. Further information about outcome measurements is available in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Studies

| Authors/year published/country | Study purpose, design, and setting | Sample |

Intervention provided by nurses |

Outcome measures | Results |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention, n | Control, n | Spiritual | Control | Intervention, mean (SD) | Control, mean (SD) | Treatment Effect, p | |||

| Wu and Koo, 2015, Taiwan7 | Purpose: Investigate the effects of a 6-week spiritual reminiscence intervention on hope, life satisfaction, and spiritual well-being on elderly patients (≥65 yo) with mild/moderate dementia Design: RCT Setting: Geriatric unit Hospital |

n = 53: 64% female, mean age 73.5 (7.3) yo and 70% attending religious activities regularly | n = 50: 74% female, mean age 73.6 (7.6) yo and 68% attending religious activities regularly | Type: Existential Description: Spiritual reminiscence intervention. Six weekly sessions (60 minutes) of scrapbooks, handicrafts, autobiographical writing, observation of growth of plants, storytelling, and singing. These activities were based on MacKinlay's spiritual tasks of the aging model (1. Meaning in life; 2. Relationships and isolation; 3. Hopes, fears, and worries; 4. Growing older and transcendence; 5. Spiritual and religious beliefs; 6. Spiritual and religious practices) Format: Group (3–6 individuals) |

Description: Routine care | Primary Herth Hope Scale No. of items: 12 Response format: 4-point scale IC: 0.89 LSS No. of items: 18 Response format: agree, disagree, or unsure IC: 0.82 Spirituality Index of Well-Being No. of items: 12 Response Format: 5-point scale IC: 0.91 Measured at baseline (start of week 1 session) and post-test (end of week 6 session) |

Hope | ||

| 38.5 (4.6) | 35.6 (3.8) | NR; <0.001a,b | |||||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||||

| 26.4 (5.7) | 24.1 (5.0) | NR; <0.001a,b | |||||||

| Spiritual well-being | |||||||||

| 40.1 (8.0) | 36.7 (7.1) | NR; <0.001a,b | |||||||

| Kwan et al., 2019, Hong Kong31 | Purpose: Examine the effectiveness and applicability of a short-term life review to enhance spiritual well-being and reduce anxiety and depression among adults receiving palliative care Design: RCT Setting: Palliative care units and hospitals |

n = 54: 48% male, 61% married, 33% 61–70 yo, 46% had no religious affiliation | n = 55: 65% male, 78% married, 25% 61–70 yo, 49% had no religious affiliation | Type: Existential Description: Life review. Explore patient's life stories using structured questions, life review booklet with pictures and photographs to enrich the presentation and recall past events with two 45-minute communication sessions 1 week apart Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Primary MQOL-HK No. of items: 17 Response format: 0–10 score Domain: Spiritual IC: 0.83 HADS No. of items: 7/7 Response format: 4-point scale Domains: Anxiety and depression IC: NR Measured at baseline and post-test (1 week later) |

Spiritual well-being (MQOL-HK spiritual) | ||

| Meaning and purpose | |||||||||

| 6.1 (2.8) | 5.8 (3.2) | 0.5; 0.404a,b | |||||||

| Life goals achieved | |||||||||

| 7.2 (2.1) | 5.6 (2.9) | 1.3; 0.002a,b | |||||||

| Feeling that life is worthwhile | |||||||||

| 6.2 (2.9) | 5.5 (3.1) | 0.6; 0.209a,b | |||||||

| Feeling good about myself | |||||||||

| 7.5 (1.9) | 5.7 (3.0) | 1.3; 0.008a,b | |||||||

| Feeling burdened | |||||||||

| 7.6 (3.2) | 7.1 (3.3) | 0.7; 0.334a,b | |||||||

| Anxiety (HADS) | |||||||||

| 2.4 (3.3) | 3.6 (3.7) | −0.3; 0.681a,b | |||||||

| Depression (HADS) | |||||||||

| 8.3 (5.0) | 8.6 (4.9) | −0.3; 0.646a,b | |||||||

| Ayyari et al., 2020, Iran35 | Purpose: Evaluate the effects of 1-month spiritual interventions on the happiness of elderly women (>60 yo) Design: RCT Setting: Nursing home |

n = 19: Mean age 77.9 (7.6) yo, 84% widowed. 84% illiterate, and 63% had active participation in religious rituals | n = 19: Mean age 80.9 (10.0) yo, 84% widowed. 95% illiterate, and 68% had active participation in religious rituals | Type: Existential/Religious Description: Spiritual Health Service. Every day for 4 weeks, acts of worship and religious rituals (e.g., turbah, praying rug, chador, Quran, and Mafatih). Active listening, supportive presence, and motivation for the elderly to write pleasant memories and life events Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Oxford Happiness Questionnaire No. of items: 29 Response Format: 6-point scale IC: 0.97 Measured at baseline and post-test (immediate and 1 month later) |

Happiness | ||

| Pretest: 45.7 (14.1) Immediately post-test: 65.1 (9.9) 1 month post-test: 64.70 (9.7) |

Pretest: 36.5 (11.9) Immediately post-test: 35.3 (9.4) 1 month post-test: 35.1 (8.9) |

NR; 0.900a,c,d | |||||||

| Mok et al., 2012, Hong Kong32 | Purpose: Develop the meaning of life intervention in response to the need for quality of life among patients with advanced-stage cancer receiving palliative care Design: RCT Setting: Oncology ward hospital |

n = 44: 55% male, 64% married, mean age 64.0 (12.4) yo, and 50% of them had no religious affiliation | n = 40: 53% male, 78% married, mean age 65.3 (10.9) yo, and 45% had no religious affiliation | Type: Existential Description: Meaning of Life intervention. Two sessions over 2–3 days (15–60 minutes) involving a semistructured interview to facilitate the search for meaning and review of a summary sheet findings. Activities of the meaning of life proposed in logotherapy and creative, experiential, and attitudinal values Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | QOLC-E No. of items: 28 Response format: 11-point scale IC: 0.56 Single-item QOL scale No. of items: 1 (measure of global QOL) Response format: 11-point scale IC: NR Measured at baseline and post-test (1 day and 2 weeks later) |

Quality of life | ||

| QOLC-E | |||||||||

| Pretest: 6.3 (1.1) D1 post-test: 7.1 (1.0) W2 post-test: 7.1 (1.1) |

Pretest: 6.7 (1.2) D1 post-test: 6.9 (1.3) W2 post-test: 6.8 (1.4) |

0.5; <0.050c,e | |||||||

| Single-item QOL | |||||||||

| Pretest: 5.1 (1.6) D1 post-test: 6.2 (1.5) W2 post-test: 6.3 (1.8) |

Pretest: 6.1 (1.8) D1 post-test: 5.7 (1.5) W2 post-test: 6.0 (2.1) |

0.8; <0.050c,e | |||||||

| Stinson and Kirk, 2005, US40 | Purpose: Evaluate the effects of group reminiscing on depression and self-transcendence of elderly women (≥60 yo) Design: RCT Setting: Assisted living facility |

n = 12: All were Caucasian female. Age varied from 72 to 96 yo |

n = 12: All were female. Age 72–90 yo, and 11 of them were Caucasian | Type: Existential Description: Structured reminiscence. Twice weekly sessions (60 minutes) for 6 weeks of reminiscence sessions, including 1. antecedent, 2. individual assessment, 3. establishing the therapeutic, 4. choosing a reminiscence therapy modality (recommendations of the NIC), and 5. outcome measurements Format: Group (size NR) |

Description: Activity | Primary GDS No. of items: 30 Response Format: yes/no IC: 0.94 STS No. of items: 15 Response Format: 4-point scale IC: 0.93 Measured at baseline and post-test (3 and 6 weeks later) |

Depression | ||

| Pretest: 7.7 (NR) W3 post-test: 6.9 (NR) W6 post-test: 8.5 (NR) |

Pretest: 12.9 (NR) W3 post-test: 11.0 (NR) W6 post-test: 10.0 (NR) |

NR; 0.190a,c | |||||||

| Self-transcendence | |||||||||

| Pretest: 3.0 (NR) W3 post-test: 3.3 (NR) W6 post-test: 3.1 (NR) |

Pretest: 2.8 (NR) W3 post-test: 2.6 (NR) W6 post-test: 3.0 (NR) |

NR; 0.150a,c | |||||||

| Musarezaie et al., 2015, Iran37 | Purpose: Determine the effects of a spiritual intervention on spiritual well-being among adults diagnosed with leukemia Design: RCT Setting: Oncology ward hospital |

n = 32: 59% male, 68% married, and mean age 41.7 (17.2) yo. 47% had not finished high school | n = 32: 63% male, 84% married, and mean age 41.6 (13.5) yo. 50% had not finished high school | Type: Existential/Religious Description: Spiritual based intervention. Supportive presence (active listening) and support for religious rituals (listening and reading to the Quran and pray) for 3 days at 4–8 pm Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Paloutzian and Ellison's Spiritual Well-Being Scale No. of items: 20 Response format: 6-point scale IC: 0.82 Measured at baseline and post-test |

Spiritual well-being | ||

| 93.6 (14.7) | 89.3 (18.4) | NR; <0.001f | |||||||

| Babamohamadi et al., 2020, Iran36 | Purpose: Investigate the effect of spiritual care based on the sound heart model on the spiritual health of Shi'a Muslim patients hospitalized with acute MI Design: RCT Setting: hospital CCU |

n = 46: 50% female, 89% married, mean age 61.3 (8.9) yo. 41% had finished high school | n = 46: 50% female, 91% married, mean age 62.7 (6.9) yo. 41% had finished high school | Type: Existential/Religious Description: Sound heart spiritual care model. An educational booklet containing the program of spiritual care based on the sound heart model: God (worship and prayer), oneself (meditation), others (charitable expenditure, family), and environment. After reading the booklet, the patients selected their desired spiritual care implemented for periods at 5–8 pm during the hospital stay and 1 month after discharge Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Paloutzian and Ellison's Spiritual Well-Being Scale No. of items: 20 Response Format: 6-point scale IC: 0.85 Measured at baseline and post-test (1 month later) |

Spiritual well-being | ||

| 96.0 (12.4) | 78.0 (19.4) | NR; <0.001g | |||||||

| Wang et al., 2010, Taiwan33 | Purpose: Test the clinical use of the gerotranscendence and its influence on gerotranscendence, depression, and life satisfaction of elderly (≥65yo) Design: RCT Setting: Assisted living facilities and nursing home |

n = 35: Mean age 80.5 (7.3). 60% female, 46% widowed, and 46% Buddhist | n = 41: Mean age 80.5 (7.3). 63% female, 51% widowed, and 56% Buddhist | Type: Existential Description: Gerotranscendence support group. Therapy manual to guide the group discussions related to aging signs and changes based on the cosmic, self, and social dimensions of GT. They could raise questions, interact with others, and exchange opinions on aging, transcendence, life, death, and weekly sessions (60 minutes) for 8 weeks Format: Group (8–12 per group) |

Description: Routine care and weekly general chatting activities for 30 minutes | Primary GTS No. of items: 10 Response format: score range from 10 to 40 points Domains: Cosmic, Coherence, and Solitude IC: 0.56 Secondary GDS No. of items: 15 Response Format: yes/no IC: 0.89 LSS No. of items: 10 Response format: 5-point scale IC: 0.88 Measured at baseline and post-test |

Gerotranscendence | ||

| Cosmic | |||||||||

| 15.8 (2.8) | 12.5 (2.0) | NR; 0.001f | |||||||

| Coherence | |||||||||

| 6.5 (1.5) | 6.0 (1.6) | NR; 0.010f | |||||||

| Solitude | |||||||||

| 9.43 (1.36) | 8.7 (1.4) | NR; 0.010f | |||||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||||

| 33.1 (5.2) | 29.8 (6.9) | NR; 0.001f | |||||||

| Depression | |||||||||

| 3.8 (3.2) | 4.7 (4.0) | NR; 0.050f | |||||||

| Butts, 2001, US6 | Purpose: Examine whether comfort touch improved the self-esteem, well-being, health status, life satisfaction, and faith and self-responsibility of elderly (≥65 yo) female nursing home residents Design: RCT Setting: Nursing homes |

n = 15h | C1: n = 15h C2: n = 15h |

Type: Existential Description: Comfort touch. Skin-to-skin touch in the form of handshaking and patting the hand, forearm, and shoulder with verbal interaction for the sole purpose of comfort and producing positive feelings for periods of 5 minutes twice a week for 4 weeks Format: Individual |

Description: C1: No treatment or interaction C2: Verbal interaction |

Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale No. of items: 10 Response format: 5-point scale IC: ranged from 0.88 to 0.90 Bradburn's Affect Balance Scale No. of items: 5/5 Response format: yes or no IC: 0.55 (Positive Affect) and 0.73 (Negative affect) Self-Evaluation of Health No. of items: NR Response Format: NR IC: NR JAREL Spiritual Well-Being Scale No. of items: 21 Response format: 6-point scale IC: NR Measured at baseline and post-test (2 and 4 weeks later) |

Self-esteem | ||

| Pretest: 29.3 (NR) W2 pos-test t: 36.0 (NR) W4 post-test: 37.5 (NR) |

Pretest: C1: 27.0 (NR) C2: 26.7 (NR) W2 post-test: C1: 27.3 (NR) C2: 28.2 (NR) W4 post-test: C1: 27.1 (NR) C2: 28.4 (NR) |

NR | |||||||

| Well-Being | |||||||||

| Pretest: 7.0 (NR) W2 post-test: 9.0 (NR) W4 post-test: 10.2 (NR) |

Pretest: C1: 7.7 (NR) C2: 6.6 (NR) W2 post-test: C1:7.7 (NR) C2: 7.3 (NR) W4 post-test: C1: 7.9 (NR) C2: 7.3 (NR) |

NR | |||||||

| Health Status | |||||||||

| Pretest: 1.6 (NR) W2 post-test: 2.1 (NR) W4 post-test: 2.3 (NR) |

Pretest: C1: 1.8 (NR) C2: 1.7 (NR) W2 post-test: C1: 1.8 (NR) C2: 1.7 (NR) W4 post-test: C1: 1.8 (NR) C2: 1.8 (NR) |

NR | |||||||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||||

| Pretest: 25.7 (NR) W2 post-test: 35.4 (NR) W4 post-test: 39.0 (NR) |

Pretest: C1: 26.6 (NR) C2: 24.3 (NR) W2 post-test: C1: 27.0 (NR) C2: 26.0 (NR) W4 post-test: C1: 27.0 (NR) C2: 27.0 (NR) |

NR | |||||||

| Faith or belief | |||||||||

| Pretest: 60.4 (NR) W2 post-test: 62.7 (NR) W4 post-test: 70.0 (NR) |

Pretest: C1: 62.1 (NR) C2: 58.9 (NR) W2 post-test: C1: 62.3 (NR) C2: 8.4 (NR) W4 post-test: C1: 61.8 (NR) C2: 60.5 (NR) |

NR | |||||||

| Pramesona and Taneepanichskul, 2018, Indonesia34 | Purpose: Investigate the effects of religious intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life of elderly Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Nursing home |

n = 30: 37% <80 yo, 42% female, 47% had no partner, 43% no or low education, 35% had <3physical illness |

n = 30: 40% <80 yo, 35% female, 45% had no partner, 45% no or low education, 25% had <3 physical illness | Type: Religious Description: Religious intervention. 36 sessions of listening to Qur'anic recital plus from 20- to 25-minute sessions of attending a sermon by a Muslim religious preacher/nurse Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care. Activities included praying, watching television, counseling, and playing or listening to music |

Primary GDS No. of items: 15 Response format: yes/no IC: 0.80 Secondary WHOQOL No. of items: 26 Response format: 0–100 IC: ranges between 0.41 and 0.77 Measured at baseline and post-test (4, 8 and 12 weeks later) |

Depression | ||

| Pretest: 6.6 (2.1) W4 post-test: 6.2 (2.0) W8 post-test: 5.3 (1.7) W12 post-test: 4.3 (1.2) |

Pretest: 7.4 (2.2) W4 post-test: 7.3 (2.2) W8 post-test: 6.8 (1.8) W12 post-test: 6.6 (1.7) |

NR; 0.170g NR; 0.042g NR; 0.002g NR; <0.001g |

|||||||

| Quality of life | |||||||||

| Pretest: 44.2 (5.3) W4 post-test: 47.3 (5.0) W8 post-test: 53.5 (4.8) W12 post-test: 58.9 (3.9) |

Pretest: 42.2 (4.1) W4 post-test: 44.2 (3.9) W8 post-test: 48.2 (3.1) W12 post-test: 51.3 (2.5) |

NR; 0.113c NR; 0.007c NR; <0.001c NR; <0.001c |

|||||||

| Ichihara et al., 2019, Japan25 | Purpose: Investigate the effects of spiritual care using the Spiritual Pain Assessment Sheet on spiritual well-being, quality of life, anxiety, and depression of advanced cancer patients Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Hematology/oncology ward, and palliative care units |

n = 22: 59% male, 59% married, mean age of 65.6 (13.1) yo and 73% reported religious affiliation | n = 24: 50% male, 79% married, mean age of 71 (13.3) yo, and 71% reported religious affiliation | Type: Existential Description: Spiritual care using the Spiritual Pain Assessment Sheet. Evaluate spiritual pain and develop a plan of care based on current spiritual status (“Are you at peace?” and “What do you feel is valuable or meaningful from now on?”) and, subsequently, incorporating questions related to relationship, autonomy, and temporality dimensions (e.g., isolation, burden, dependency, loss of control in the future, and hopelessness) for 2 weeks Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care. Basic care for psychosocial and spiritual problems (i.e., listening, consulting with psychotherapist or chaplain as needed) | Primary FACIT-Sp scale No. of items: 12 Response format: 5-point scale IC: ranges between 0.72 and 0.87 Secondary CoQoLo No. of items: 18 Response format: 7-point scale IC: 0.90 HADS No. of items: 7/7 Response format: 4-point scale Domains: Anxiety and depression IC: NR Measured at baseline and post-test (2 weeks later) |

Spiritual well-being | ||

| Peace/meaning | |||||||||

| Pretest: 19.0 (5.2) W2 post-test: 20.1 (6.4) |

Pretest: 19.5 (5.5) W2 post-test: 13.9 (8.3) |

1.0; <0.010i,j | |||||||

| Faith | |||||||||

| Pretest: 7.8 (3.5) W2 post-test: 8.6 (4.3) |

Pretest: 8.0 (3.4) W2 post-test: 7.8 (3.5) |

0.7; 0.045i,j | |||||||

| Quality of life | |||||||||

| Pretest: 81.9 (14.0) W2 post-test: 82.8 (17.0) |

Pretest: 82.6 (12.8) W2 post-test: 78.2 (18.0) |

0.2; 0.540i,j | |||||||

| Anxiety (HADS) | |||||||||

| Pretest: 7.0 (3.8) W2 post-test: 4.7 (2.5) |

Pretest: 6.0 (4.0) W2 post-test: 7.4 (4.4) |

0.9; 0.010i,j | |||||||

| Depression (HADS) | |||||||||

| Pretest: 8.6 (4.3) W2 post-test: 7.4 (4.3) |

Pretest: 8.4 (4.2) W2 post-test: 9.6 (5.0) |

0.5; 0.100i,j | |||||||

| Elham et al., 2015, Iran3 | Purpose: Investigate the effects of spiritual/religious interventions on spiritual well-being and anxiety of patients with cardiovascular diseases (≥60 yo) Design: Quasi-Experimental Setting: CCU hospital |

n = 33: 55% male, 58% married. 76% 60–70 yo. 58% illiterate | n = 33: 64% male, 70% married, 64% 60–70 yo. 58% illiterate | Type: Existential/religious Description: Spiritual/religious intervention. Presence for 30 minutes, giving them hope, talking about spiritual experiences, encouraging the sense of generosity and forgiveness, strengthening their relationships with the family, providing opportunities for worship and prayer, and listening to relaxing music for at least 3 days (60–90 minutes) in the evening shift Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Primary Paloutzian and Ellison's Spiritual Well-Being Scale No. of items: 20 Response format: 6-point scale IC: 0.87 STAI No. of items: 20/20 Response format: 4-point scale IC: 0.97 Measured at baseline and post-test |

Spiritual well-being | ||

| 83.3 (9.4) | 81.0 (8.7) | NR; 0.049i | |||||||

| Anxiety (State-Trait) | |||||||||

| 50.0 (NR) | 58.0 (NR) | NR; <0.001k | |||||||

| Alp and Yucel, 2021, Turkey2 | Purpose: Investigate the impacts of therapeutic touch on the comfort and anxiety of elderly (<89 yo) Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Nursing home |

n = 30: 50% female, 67% widowed, 50% ranged from 75 to 89 yo, and 50% had hypertension | n = 30: 50% female, 63% widowed, 50% ranged from 75 to 89 yo, 73% had hypertension | Type: Existential Description: Therapeutic touch. Touch with the hands for periods of 20 minutes for four successive days Format: Individual |

Description: Routine care | Primary STAI No. of items: 20/20 Response format: 4-point scale Domains: S-Anxiety and T-Anxiety IC: 0.88 General Comfort Questionnaire No. of items:48 Response format: 4-point scale Domain: Comfort subdimensions and levels IC: 0.82 Measured at baseline and post-test (measurement 2 after intervention) |

Anxiety (State-Trait) | ||

| 44.0 (2.1) | 48.4 (1.2) | 0.001g | |||||||

| General comfort p = 0.01g | |||||||||

| Physical | |||||||||

| 2.9 (0.04) | 2.8 (0.02)l | NR | |||||||

| Psychospiritual | |||||||||

| 3.2 (0.08) | 3 (0.02)l | NR | |||||||

| Environmental | |||||||||

| 3.4 (0.05) | 3.2 (0.03)l | NR | |||||||

| Sociocultural | |||||||||

| 2.6 (0.04) | 2.4 (0.02)l | NR | |||||||

| Relief | |||||||||

| 3.2 (0.03) | 3 (0.02)l0 | NR | |||||||

| Relaxation | |||||||||

| 3.0 (0.05) | 2.9 (0.05)l | NR | |||||||

| Superiority | |||||||||

| 3.0 (0.07) | 2.8 (0.02)l | NR | |||||||

| Zhang et al., 2019, China30 | Purpose: Evaluate the feasibility and effects of the WeChat-based life review on anxiety, depression, self-transcendence, meaning in life, and hope Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Oncology ward hospital |

n = 44: 77% male, age ranged from 41 to 60 yo, 93% married, 82% had advanced cancer with metastasis, 55% had no religious affiliation | n = 42: 69% male, age ranged from 41 to 60 yo, 83% married. 86% had advanced cancer with metastasis. 67% had no religious affiliation | Type: Existential Description: WeChat-based life review program. Weekly sessions over 6 weeks (40–60 minutes), in which the modules included Memory Prompts, Review Extraction, Mind Space, and E-legacy products. The interviews covered participants' lives, including the present (cancer experience), adulthood, childhood, and a summary of their lives Format: Virtual face-to-face |

Description: Routine care. Personal care, medical care, health education, free Internet access, and emotional support, all provided by the study hospital |

Self-transcendence scale No. of items: 15 Response format: 4-point scale IC: ranges between 0.83 and 0.87 Meaning-in-Life Questionnaire No. of items: 10 Response format: 7-point scale IC: ranges between 0.79 and 0.93 Herth Hope Scale No. of items: 12 Response format: 4-point scale IC: 0.87 Zung's self-rating anxiety scale No. of items: 20 Response format: 4-point scale IC: 0.79 Zung's self-rating depression scale No. of items: 20 Response format: 4-point scale IC: 0.87 Measured at baseline and post-test |

Self-Transcendence | ||

| 53.5 (4.6) | 43.9 (6.6) | NR; 0.001g | |||||||

| Meaning in life | |||||||||

| 56.6 (10.1) | 49.4 (8.6) | NR; 0.001g | |||||||

| Hope | |||||||||

| 36.4 (3.3) | 35.1 (3.5) | NR; 0.098g | |||||||

| Anxiety | |||||||||

| 25.9 (3.7) | 32.1 (5.5) | NR; 0.001g | |||||||

| Depression | |||||||||

| 30.5 (4.4) | 39.0 (7.5) | NR; 0.001g | |||||||

| Authors/year published/country | Study purpose, design, and setting | Sample, pretest, and post-test (single group) | Intervention provided by nurses | Outcome measures | Results |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest mean (SD)m | Post-test mean (SD)n | Difference between pretest and post-testo | |||||||

| Carvalho et al., 2014, Brazil38 |

Purpose: Evaluate the effect of prayer on anxiety Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Oncology ward Hospital |

n = 20: 75% were male, 55% 51–60 yo, 75% were married, and 65% Catholic |

Type: Religious Description: Prayer intervention. An audio recording of a musician's voice with good diction. The intervention was based on no invocation of saints, citing Psalm 138 of the Bible, which speaks of divine omniscience: God knows all and sees all. Patients held hands with the nurse researcher, who conducted an intercession prayer for periods of 11 minutes Format: Individual |

STAI No. of items: 20/20 Response Format: 4-point scale IC: NR |

Anxiety (state) |

||||

| 33.5 (4.9) |

28.4 (5.6) |

5.1; <0.001g |

|||||||

| Vlasblom et al., 2015, Netherlands39 | Purpose: Investigate the implementation of a spiritual screening and assess the effects on the spiritual well-being Design: Quasi-experimental Setting: Hospital |

n = 106 (pretest), n = 103 (post-test): 58% were female. Mean age was 64 (16.20) yo and 48% of them had any spiritual background | Type: Existential Description: Nurses' Screening of Spiritual Needs. On admission, nurses administer the spiritual screening (questions related to the purpose and the meaning of life, illness, and spiritual beliefs) through an electronic patient history using the software program Mediscore. In the case of a positive spiritual distress score, the Department of Spiritual and Pastoral Care receives notifications Format: Individual |

Primary FACIT-Sp scale No. of items: 12 Response format: 5-point scale IC: NR Spiritual consultation requests (n) |

Spiritual well-being |

||||

| Meaning and peace | |||||||||

| 23.7 (5.8) |

22.8 (4.3) |

0.9; 0.004g |

|||||||

| Faith | |||||||||

| 7.7 (4.4) |

6.1 (4.3) |

1.6; 0.036g |

|||||||

| Spiritual consultation | |||||||||

| n = 2 | n = 33 | NR | |||||||

Interaction effects (group × time).

p Values were calculated using generalized estimating equations.

Repeated measures ANOVA.

Reported p value in the interaction effect (group × time) equal 0.90. However, the study presents discrepancies in report of results.

p < 0.05 to adjusted difference and 95% CI using ANOVA. Each outcome measure was tested individually, with its corresponding baseline score used as a covariate. The results of the study present high attrition (31%) combined with per-protocol analysis (instead of the more rigorous intent to treat analysis) and baseline imbalance on outcome variables.

ANCOVA.

Simple group comparison at post-test.

The study lists demographic characteristics for the entire sample (n = 45) instead of reporting by each group.

Difference in change score between intervention and control groups.

Standardized effect size.

p Value does not report comparison between two groups. Instead, it reported pretest and post-test for the group intervention only.

The study reports a small range of SD by each subdimension and levels of comfort, for instance, Relief subscale: 3.2 (SD = 0.03) and 3 (SD = 0.02), intervention and control group, respectively. We found discrepancies in the SD compared to another Turkey study41 using the same General Comfort Questionnaire, for example, Relief: 2.7 (SD = 0.3) and 2.8 (SD = 0.3).

Mean and standard deviation at pretest.

Mean and standard deviation at post-test.

Difference between pretest and post-test.

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; ANOVA, analysis of variance; CoQoLo, Comprehensive Quality-of-Life Outcome; FACIT-Sp, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GTS, Gerotranscendence Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IC, internal consistency reliability is estimated by Cronbach's coefficient alpha; IC:NR, Cronbach's coefficient alpha did not report in this study; LSS, Life Satisfaction Scale; MQOL-HK, McQill Quality-of-Life Index—Hong Kong version; NIC, Nursing Interventions Classification; NR, not reported; QOLC-E, Quality-of-Life Concerns in the End of Life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STS, Self-Transcendence Scale; WHOQOL, World Health Organization Quality of Life; yo, years old.

Well-being and human spirituality

This category includes spiritual well-being,3,7,25,31,36,37,39 transcendence,30,33,40 quality of life,25,32,34 life satisfaction,6,7,33 and other well-being-related concepts, such as hope,7,30 meaning in life,30 faith,6 health status,6 and comfort.2 The most frequently measured outcome was spiritual well-being,3,7,25,31,36,37,39 with all but one39 of the seven studies utilizing these measures reporting statistically significant positive changes associated with the delivery of spiritual interventions.

Life satisfaction,6,7,33 transcendence,30,33,40 and quality of life,25,32,34 were also utilized as outcomes in studies. Statistically significant improvements for these outcomes were seen in five7,30,32–34 of the eight studies measuring them. Comparisons of outcomes across the studies could not be performed due to the heterogeneity of outcome measures. For instance, spiritual well-being was measured across studies3,7,25,31,36,37,39 using five different validated self-report scales: Paloutzian and Ellison's Spiritual Well-Being, FACIT-Sp (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual), MQOL-HK (McQill Quality-of-Life Index—Hong Kong version), Spirituality Index of Well-Being, and JAREL Spiritual Well-Being Scale.

Psychological outcomes

It comprises anxiety,2,3,25,30,31,38 depression,25,30,31,33,34,40 and other psychological and mood-related concepts.6,35 Anxiety was measured using various scales. Three studies2,3,38 used the validated self-report tool STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), containing 40 items distributed in 2 parts. The first 20 items measure STAI-S (anxiety about an event or situation), and the second 20 items measure STAI-T (anxiety that one experiences daily). These studies2,3,38 reported a statistically significant decrease in total anxiety levels.

Depression was measured in 3 other studies33,34,40 using the GDS (Geriatric Depression Scale), containing 15 items with yes or no answers related to somatic and cognitive complaints, motivation, future/past orientation, mood, and others. Of three studies, only one34 found a statistically significant decrease in depression. Two other articles25,31 utilized the HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), comprising 14 items, 7 questions about anxiety and 7 others related to depression. Both studies25,31 did not find a statistically significant decrease in anxiety and depression.

Quality of studies

The QualSyst tool assessed the overall quality of articles.28 Only two studies31,36 scored high quality with scores greater than 80% (Table 2). Most RCTs6,7,32,33,35,37,40 and all the quasi-experimental2,3,25,30,34,38,39 ranged from 60% to 79% (moderate quality). Although most studies were classified as moderate quality, we found that the general nature of the assessment did not fully capture the limitations of studies when viewed collectively—for instance, the lack of information about the interventions and their fidelity limited group comparison and reproducibility.

Furthermore, several studies presented baseline imbalance31,32 or comparison of demographic variables were not comprehensive,6,40 resulting in selection and performance bias between the groups. In addition, the quality ratings of studies were also adversely impacted by small sample sizes and difficult recruitment plans and follow-up. Most studies2,7,25,30–33,35,36 presented lost to follow-up after randomization. Studies reported most enrolled participants were palliative care and died by the end of the study period31,32 or participant's withdrawal.2,7,25,30–33,35,36

Furthermore, the studies demonstrated weakness in blinding between participants and investigators. The most common sampling method was convenience.2,3,25,30,34,38,39 To estimate the treatment effect, several studies reported simple group comparison at post-test.2,30,34,36,38,39 Others reported generalized estimating equation-based group versus time.7,31 Repeated measures analysis ANOVA (analysis of variance)32,34,35,40 or ANCOVA (analysis of covariance)33,37 studies were used in their analyses. Finally, although all studies provided descriptions of the interventions, data collection methods and descriptions of scales used were not fully operationalized in some studies. All those concerns were particularly notable for assessing spiritual interventions' effectiveness on patient outcomes.

Discussion

This systematic review identified 16 studies to assess existential, religious, or mixed spiritual interventions delivered by nurses for palliative care and other chronic conditions. The studies demonstrated that different spiritual interventions improved individuals' spiritual health and psychological outcomes in hospitals or assisted long-term care facilities.

The spiritual interventions generally seemed to clarify and enhance self-understanding of the meaning and purpose of life, relationships, and death30–32,38 for individuals receiving palliative care or cancer treatment. In addition, the spiritual interventions tended to address patients' emotional and psychological needs, inducing a sense of relief, comfort, and calm spirit.25,32,37,38 In the social context, spiritual interventions helped patients near to death experience connectedness with their inner self (integrity restoration in the final lifespan stage) and others (family).30–32

Across the studies, spiritual interventions delivered by nurses were primarily existential based. For instance, nurses focused on recovering the whole-person health status based on energetic therapies or reviewing life events of individuals in assisted nursing homes, as exemplified by the delivery of touch therapy6 and reminiscence.40 Psychospiritual narratives were also usual existential interventions represented in several cultures.7,30–33,40 Of the six7,30–33,40 psychospiritual intervention studies, three30–32 were delivered to seriously ill patients in palliative care and oncology units. Nurses discussed existential questions and counseled patients with strong emotions in daily care, enhancing a sense of meaning during patients' dying process.32

In approaching the delivery of this type of spiritual care, the patients tend to notice their spirituality. Unlike physical or pharmacologic treatments that are disease stage specific, psychospiritual interventions are usually applicable at all stages of care to improve patient outcomes and support them cope with the disease. Those interventions encourage patients to share pleasant or unpleasant experiences and re-evaluate their spiritual peace state and life satisfaction. Our study supports previous findings reported by Chen et al., evaluating the effects of spiritual care provided by a multidisciplinary team, which found that life review and spiritual group therapy relieve patients' stress and improve inner peace.24

Conversely, religious-based interventions were delivered less often by nurses.34,38 In only one study,38 nurses used prayer to improve psychological outcomes in individuals with advanced-stage cancer. Although researchers found that patients use prayer as a form of spirituality and prefer to receive prayer from their nurses,42 the clinical application of religious practices is limited. Possible reasons may include hospital rules43 or nurses' concerns about approaching their patients in a manner that is comfortable and accessible, no matter their religious-faith affiliation.44 Furthermore, religious-based interventions are rarely covered in the nursing curriculum. Therefore, nurses are encouraged to refer this type of intervention to pastoral care.

Noteworthy, the delivery of mixed interventions3,35–37 have been tested in clinical settings based on Islamic beliefs. Compared to other interventions, mixed based interventions such as active listening and presence helped patients feel that nurses indeed were concerned about them during an existential crisis. Our findings revealed that the nurse's presence induced a sense of relief and increased the patient's connectivity with the faith.3,35–37 In addition, during routine nursing care, patients were encouraged to seek healing by invoking God's mercy through supplication and the connectivity between other individuals and nature. Corroborating our findings, Ghorbani et al. also found that nurses created a spiritually nurturing environment where nurses demonstrated empathy and listened to patients express their feelings, concerns, and spiritual beliefs.16

Our finding is consistent with the nursing interventions derived from the conceptual analysis of spiritual care proposed by Ramezani et al.45 That study includes interventions focused on patients' meaning of life and spiritual growth, healing presence, and exploring spiritual perspectives.45 Agrimson and Taft explain that religion and spirituality are inseparable in many cultures.46 The authors state that understanding individual and cultural differences in spirituality and religion makes it possible to reduce nursing care barriers.46

Despite the variability in spiritual interventions and patient outcomes, nearly all studies reported improved outcomes following the interventions. Increased spiritual well-being was associated with existential based interventions7,25,31 and mixed interventions.3,35–37 Reduced levels of anxiety and depression during a patient's distress were reported for existential,2,25,30,33 religious,34,38 and mixed interventions.3 These findings are similar to those presented in a previous meta-analysis of 14 RCTs that concluded spiritual interventions have a moderate effect on spiritual well-being and meaning in life for cancer patients.23 Our findings should be carefully interpreted and applied to populations outside the studies presented in this review due to the variability of spiritual interventions and their delivery methods and the limited reliability and validity of the outcome measures to answer the questions of fidelity and efficacy of interventions.

The spiritual interventions' characteristics (format, session length, content, and approach) and the comparison groups varied considerably across studies. Most articles did not develop a comprehensive protocol or standards for implementing the spiritual interventions to ensure ease of replicating and evaluating interventions. Even the studies rated with moderate quality presented limited descriptions of their interventions, challenging their generalizability and reproducibility. We also found interventions delivered in the control groups defined as “routine care” without a detailed description of this type of care. Of 16 studies, only four25,30,33,34 cited routine care activities in the control group, including consulting with chaplains or psychotherapists,25 emotional support,30 chatting activities,33 or praying.34

The lack of description of the interventions provided to control groups hinders the interpretability of the impact of spiritual interventions on the patient outcomes. For instance, access to coping management or counseling sessions as part of institutional care may have interfered with the effectiveness of spiritual interventions. Future investigations should include standardized protocols about the type of spiritual intervention, time of sessions, activities included within the interventions, how the nurses perform them, and whether they received previous training, such as those from religious facilities.

The sampling methods across the studies also pose limitations to the study findings. Seven of the studies were quasi-experimental,2,3,25,30,34,38,39 with two of them being single group pre–post-test.38,39 Studies with this type of design typically are at risk of selection bias due to all participants receiving the same intervention and assessments without a group comparison. Conclusions about the efficacy of spiritual interventions delivered by nurses were also limited by the small sample sizes, convenience sampling, and absence of power analysis-reported small effect sizes. The absence of power analyses for the RCTs6,7,32,37,40 was a serious limitation of evaluating the effect of interventions. To improve the generalizability of spirituality studies, we recommend that these studies be replicated in larger multicenter RCTs using a longitudinal design to assess patients' changing experiences and needs over time47,48 and that the intervention's procedure be rigorously defined and monitored to ensure fidelity.

Finally, the studies showed some inconsistency and heterogeneity in the patient outcome measures. Across the studies, the same outcomes, such as spiritual well-being, anxiety, and depression, were assessed with different scales. In addition, the absence of evidence supporting the reliability of scales used in the studies6,25,31,32,38,39 weakens the conclusions that can be drawn. Despite the weaknesses noted, our review is a valuable contribution to understanding the state of the science of spiritual interventions delivered by nurses and subsequent studies needed to advance this important area of science in nursing.

Our systematic review showed limitations. This review did not include studies from the gray literature or other sources outside of electronic databases. For additional literature, we searched the reference lists cited in the studies included in our sample. Only English studies were included, and relevant studies in other languages may have been omitted. Despite these limitations, our review offers an overview of spiritual interventions delivered by nurses across countries and cultures, with suggestive evidence of improved psychological and spiritual outcomes.

Implications for practice and research

The studies in our review varied in scope and design. To overcome the heterogeneity of spiritual interventions and limited generalizability, reliable and validated spiritual interventions found in standardized nursing terminologies (SNTs) should be implemented in practice.

In our review, three studies6,38,40 recommended the spiritual interventions, Therapeutic Touch, Reminiscence, and Spiritual Support, from the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC)49 to assist nurses across cultures in providing existential based interventions and religious based interventions. NIC is a standardized terminology recognized by the American Nurses Association as a nursing classification system that meets consistent data standards.50 Other spiritual interventions, such as Spiritual Growth Facilitation, Presence, and Active Listening, have also been described to provide new knowledge regarding core spiritual care activities and a more concrete way to identify and document patients' spiritual needs.51 A recent systematic review reporting secondary analyses of data coded with SNTs revealed that SNTs are a viable foundation for systematically building knowledge to demonstrate and measure nurses' contribution to health care and advance nursing.52

Other future paths of inquiries about spiritual interventions might include the following: Why should nurses take time to assess the spiritual needs of religious and nonreligious patients? What are the spiritual nursing interventions feasible in short- or long-term care? What are the measured patient outcomes? Are there gold standard spiritual interventions in the palliative care context? What role do nurses play in this care that differs from the other palliative care members (chaplains or psychologists)?

Conclusion

Meaningful conclusions can be drawn from this systematic review, moving the state of the science of spiritual care forward in different patient groups, especially patients presenting fear of death and loss of faith. This study revealed new insights that may positively contribute to increased visibility and interest in using spiritual interventions in palliative care and clinical practice.

As noted, however, additional research is needed to advance our understanding of spiritual interventions within the scope of nursing. Further investigations should include rigorously designed RCTs to answer important questions about spiritual nursing interventions with clearly defined concepts and high-quality measures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Maggie Ansell for her expert literature search assistance and contribution during the review of terms and search strategy in the earlier stages of this review.

Authors' Contributions

Concept and planning of the study, protocol writing, and writing of the first draft: F.D.S., G.K., and TM. Review of abstracts and articles, and data extraction: F.D.S., S.H., and O.M. Quality assessment rating of studies and revising: F.D.S. and S.H. Article preparation, conceptualization, and editing/drafting of the article: F.D.S., T.M., Y.Y., S.H., O.M., K.D.L., H.C., R.B., D.W., and G.K. Revised critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), [1R01NR018416-01]. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NINR.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Grossoehme DH, Friebert S, Baker JN, et al. : Association of religious and spiritual factors with patient-reported outcomes of anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, and pain interference among adolescents and young adults with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e206696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alp FY, Yucel SC: The effect of therapeutic touch on the comfort and anxiety of nursing home residents. J Relig Health 2021;60:2037–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elham H, Hazrati M, Momennasab M, et al. : The effect of need-based spiritual/religious intervention on spiritual well-being and anxiety of elderly people. Holist Nurs Pract 2015;29:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. : Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCarthy VL, Hall LA, Crawford TN: Facilitating self-transcendence: An intervention to enhance well-being in late life. West J Nurs Res 2018;40:854–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butts JB: Outcomes of comfort touch in institutionalized elderly female residents. Geriatr Nurs 2001;22:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu LF, Koo M: Randomized controlled trial of a six-week spiritual reminiscence intervention on hope, life satisfaction, and spiritual well-being in elderly with mild and moderate dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, et al. : Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:635..e642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selman L, Beynon T, Higginson IJ, et al. : Psychological, social, and spiritual distress at the end of life in heart failure patients. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2007;1:260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith GA: US public becoming less religious, https://www.pewforum.org/2015/11/03/u-s-public-becoming-less-religious 2015. (Last accessed March 26, 2021).

- 11. Moberg DO: Research in spirituality, religion, and aging. J Gerontol Soc Work 2005;45:11–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. : Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 4th ed. nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp 2018. (Last accessed August 20, 2020).

- 14. Ferrell B, Munevar C: Domain of spiritual care. Prog Palliat Care 2012;20:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paloutzian R, Ellison C: Loneliness, spiritual wellbeing, and the quality of life. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D (eds): Loneliness: A Source Book of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy, 1st ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1982, pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghorbani M, Mohammadi E, Aghabozorgi R, et al. : Spiritual care interventions in nursing: An integrative literature review. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:1165–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Brien MR, Kinloch K, Groves KE, et al. : Meeting patients' spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses' and healthcare professionals' perceptions of spiritual care training. J Clin Nurs 2019;28:182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cavendish R, Luise B, Home K, et al. : Recognizing opportunities for enhanced spirituality relevant to young adults. Nurs Diagn 2001;12:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Holistic Nurses Association (AHNA): Holistic Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.org, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Nurses Association (ANA): Faith Community Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, 2nd ed. Silver Springs, MD: Nursesbooks.org, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cockell N, McSherry W: Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of published international research. J Nurs Manag 2012;20:958–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. International Council of Nurses (ICN): Code of ethics. www.icn.ch/images/stories/documents/about/icncode_english.pdf 2006. (Last accessed May 13, 2021).

- 23. Oh PJ, Kim SH: The effects of spiritual interventions in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum 2014;41:E290–E301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen J, Lin Y, Yan J, et al. : The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2018;32:1167–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ichihara K, Ouchi S, Okayama S, et al. : Effectiveness of spiritual care using spiritual pain assessment sheet for advanced cancer patients: A pilot non-randomized controlled trial. Palliat Support Care 2019;17:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baird RP: Spiritual care intervention. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice J (eds): Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care Nursing, 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 546–553. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L: Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. https://www.ihe.ca/advanced-search/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields 2004. (Last accessed July 2, 2020).

- 29. Peng JK, Hepgul N, Higginson IJ, et al. : Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med 2019;33:24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang X, Xiao H, Chen Y: Evaluation of a WeChat-based life review programme for cancer patients: A quasi-experimental study. J Adv Nurs 2019;75:1563–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kwan CWM, Chan CWH, Choi KC: The effectiveness of a nurse-led short-term life review intervention in enhancing the spiritual and psychological well-being of people receiving palliative care: A mixed-method study. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;91:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mok E, Lau KP, Lai T, et al. : The meaning of life intervention for patients with advanced-stage cancer: Development and pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012;39:E480–E488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang JJ, Lin YH, Hsieh LY: Effects of gerotranscendence support group on gerotranscendence perspective, depression, and life satisfaction of institutionalized elders. Aging Ment Health 2011;15:580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pramesona BA, Taneepanichskul S: The effect of religious intervention on depressive symptoms and quality of life among Indonesian elderly in nursing homes: A quasi-experimental study. Clin Interv Aging 2018;13:473–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ayyari T, Salehabadi R, Rastaghi S, et al. : Effects of spiritual interventions on happiness level of the female elderly residing in nursing home. Evid Based Care 2020;10:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Babamohamadi H, Kadkhodaei-Elyaderani H, Ebrahimian A, et al. : The effect of spiritual care based on the sound heart model on the spiritual health of patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Relig Health 2020;59:2638–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Musarezaie A, Ghasemipoor M, Momeni-Ghaleghasemi T, et al. : A study on the efficacy of spirituality-based intervention on spiritual well being of patients with leukemia: A randomized clinical trial. Middle East J Cancer 2015;6:97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Carvalho CC, Chaves Ede C, Lunes DH, et al. : Effectiveness of prayer in reducing anxiety in cancer patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2014;48:683–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vlasblom JP, Van der Steen JT, Walton MN, et al. : Effects of nurses' screening of spiritual needs of hospitalized patients on consultation and perceived nurses' support and patients' spiritual well-being. Holist Nurs Pract 2015;29:346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stinson CK, Kirk E: Structured reminiscence: An intervention to decrease depression and increase self-transcendence in older women. J Clin Nurs 2006;15:208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aktaş D: Prevalence and factors affecting dysmenorrhea in female university students: Effect on general comfort level. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16:534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Taylor EJ, Mamier I: Spiritual care nursing: What cancer patients and family caregivers want. J Adv Nurs 2005;49:260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matthews A: Nurses behavioral responses to patient spiritual needs [Podium Presentation]. In: 20th Annual Research Day, Nu Omega Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing. Wilmington, North Carolina, April 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chochinov HM, Cann BJ: Interventions to enhance the spiritual aspects of dying. J Palliat Med 2005;8(Suppl 1):S103–S115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramezani M, Ahmadi F, Mohammadi E, et al. : Spiritual care in nursing: A concept analysis. Int Nurs Rev 2014;61:211–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Agrimson LB, Taft LB: Spiritual crisis: A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2009;65:454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. : Dignity in the terminally ill: A cross sectional cohort study. Lancet 2002;360:2026–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cohen SR, Bultz B, Clarke J, et al. : Well-being at the end of life: Part 1. A research agenda for psychosocial and spiritual aspects of care from the patient's perspective. Cancer Prev Control 1997;1:334–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Butcher H, Bulechek GM, Dochterman JMM (eds): Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50. American Nurses Association (ANA): Recognized terminologies and data element sets. http://nursingworld.org/npii/terminologies.htm 2006. (Last accessed May 13, 2021).

- 51. Cavendish R, Konecny L, Mitzeliotis C, et al. : Spiritual care activities of nurses using Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) labels. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif 2003;14:113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Macieira TGR, Chianca TCM, Smith MB, et al. : Secondary use of standardized nursing care data for advancing nursing science and practice: A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019;26:1401–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.