Abstract

Glycopeptide-resistant enterococci of the VanC type synthesize UDP-muramyl-pentapeptide[d-Ser] for cell wall assembly and prevent synthesis of peptidoglycan precursors ending in d-Ala. The vanC cluster of Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174 consists of five genes: vanC-1, vanXYC, vanT, vanRC, and vanSC. Three genes are sufficient for resistance: vanC-1 encodes a ligase that synthesizes the dipeptide d-Ala-d-Ser for addition to UDP-MurNAc-tripeptide, vanXYC encodes a d,d-dipeptidase–carboxypeptidase that hydrolyzes d-Ala-d-Ala and removes d-Ala from UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[d-Ala], and vanT encodes a membrane-bound serine racemase that provides d-Ser for the synthetic pathway. The three genes are clustered: the start codons of vanXYC and vanT overlap the termination codons of vanC-1 and vanXYC, respectively. Two genes which encode proteins with homology to the VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system were present downstream from the resistance genes. The predicted amino acid sequence of VanRC exhibited 50% identity to VanR and 33% identity to VanRB. VanSC had 40% identity to VanS over a region of 308 amino acids and 24% identity to VanSB over a region of 285 amino acids. All residues with important functions in response regulators and histidine kinases were conserved in VanRC and VanSC, respectively. Induction experiments based on the determination of d,d-carboxypeptidase activity in cytoplasmic extracts confirmed that the genes were expressed constitutively. Using a promoter-probing vector, regions upstream from the resistance and regulatory genes were identified that have promoter activity.

High-level resistance to glycopeptides in enterococci results from the synthesis of peptidoglycan precursors ending in d-lactate (d-Lac) (VanA, VanB, and VanD types) (4, 31) and the elimination of high-affinity d-alanine (d-Ala)-ending precursors synthesized by the host (5, 33). Low-level resistance to vancomycin is found in strains belonging to the VanC and VanE types which incorporate d-Ser into the C-terminal position of UDP-muramyl pentapeptide (9, 17, 34). In strains with VanA, VanB, or VanD phenotypes, synthesis of d-Ala-d-Lac requires the presence of a ligase of altered specificity (11) and a dehydrogenase that reduces pyruvate to d-Lac (6). In VanC-type strains, ligase genes (vanC-1, vanC-2, and vanC-3) (15, 26) that encode proteins necessary for the synthesis of d-Ala-d-Ser have been characterized (29). Synthesis of d-Ser is carried out by a pyridoxal phosphate-dependent and membrane-bound serine racemase (VanT) (2).

Hydrolysis of precursors (ending in d-Ala) synthesized by the host prevents the interaction of the glycopeptide molecule with its target (35). Two enzymes are involved in performing this function: VanX (VanXB) is a d,d-dipeptidase that hydrolyzes d-Ala-d-Ala (33) and VanY (VanYB) is a d,d-carboxypeptidase that hydrolyzes the terminal d-Ala residue of late peptidoglycan precursors that are synthesized if elimination of d-Ala-d-Ala by the host is not complete (5). In Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174, representative of the VanC type of resistance, both activities are encoded by the same gene, vanXYC (36). VanXYC contains consensus sequences for binding zinc, stabilizing the binding of substrate and catalyzing hydrolysis that are present in both VanX- and VanY-type enzymes. The protein has very low dipeptidase activity against d-Ala-d-Ser (unlike VanX) and no activity against UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[d-Ser] (36).

A two-component regulatory system controls the expression of resistance genes in VanA- and VanB-type strains (2, 14). The system comprises genes that encode response regulators (VanR and VanRB) and histidine kinase proteins (VanS and VanSB) (7, 40). The C-terminal kinase domain of VanS undergoes autophosphorylation on a histidine residue in the presence of ATP and transfers the phosphate group to VanR (40). Phospho-VanR (P-VanR and P-VanRB) activate transcription of the resistance genes and of their own genes after binding to promoter regions upstream from the resistance (PvanH) and regulatory (PvanR) genes (20). A similar gene cluster has been described in VanD-type strains (13). We describe here the gene cluster responsible for vancomycin resistance in E. gallinarum BM4174. The cluster comprised five genes: three were necessary and sufficient for resistance (vanC-1, vanXYC, and vanT) and the remaining two (vanRC and vanSC) encoded a two-component regulatory system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are described in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Enterococci were grown in brain-heart-yeast extract (BHY) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) broth or on BHY agar. Gentamicin (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 150 μg/ml, was added to the medium for Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 containing derivatives of plasmid pAT392 (5), and spectinomycin (Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands), 480 μg/ml, was added for E. gallinarum BM4174 containing plasmid derivatives of pAT78 (3). Vancomycin (4 μg/ml) was added to the medium to test for induction of d,d-dipeptidase activity in E. gallinarum BM4174. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (12) was grown in Luria-Bertani (Difco) broth or agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml when derivatives of pUC18 (27) were present, gentamicin (8 μg/ml) when containing derivatives of pAT392 (5), or spectinomycin (60 μg/ml) when containing derivatives of pAT78 (3). Restriction profiles of pAT392 and pAT78 derivatives from enterococci and from E. coli were compared to screen for any DNA rearrangement. MICs of vancomycin and chloramphenicol for E. faecalis JH2-2 and E. gallinarum BM4174 were determined by using twofold dilutions of the antibiotic in BHY broth with an inoculum of 106 cells per ml and after 48 h of incubation at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli XL1-Blue | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA46 thi relA1 lac F′ [proAB+ lacIqlacZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr)] | 12 |

| E. faecalis JH2-2 | JH2 Fusr Rifr | 22 |

| E. gallinarum BM4174 | Vanr human clinical isolate | 15 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAT392 | oriRpAMβ1 oriRpUC oriTRK2 spc lacZα P2 aac(6′)-aph(2") | 5 |

| pAT78 | oriRpAMβ1 oriRpUC oriTRK2 spc lacZα cat | 3 |

| pCA8 | 2.5-kb SacI-XbaI inverse PCR product containing the 3′ end of vanSC cloned into pUC18 | This work |

| pCA9 | 1.4-kb SacI-XbaI inverse PCR product containing the region upstream from vanC-1, cloned into pUC18 | This work |

| pCA10 | 3.6-kb SacI-XbaI vanC-1 vanXYC vanT fragment cloned into pAT392 | This work |

| pCA11 | 0.7-kb BamHI-SalI fragment containing the intergenic region between orf1 and vanC-1, including the 3′ end of orf1 and the 5′ end of vanC-1 cloned into pAT78 | This work |

| pCA12 | 0.47-kb BamHI-SalI fragment containing the intergenic region between vanT and vanRC, including the 3′ end of vanT and the 5′ end of vanRC cloned into pAT78 | This work |

| pUC18 | Plasmid vector AmprlacZα | 27 |

Abbreviations: Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Fusr, fusidic acid resistance; Rifr, rifampin resistance; Vanr, vancomycin resistance.

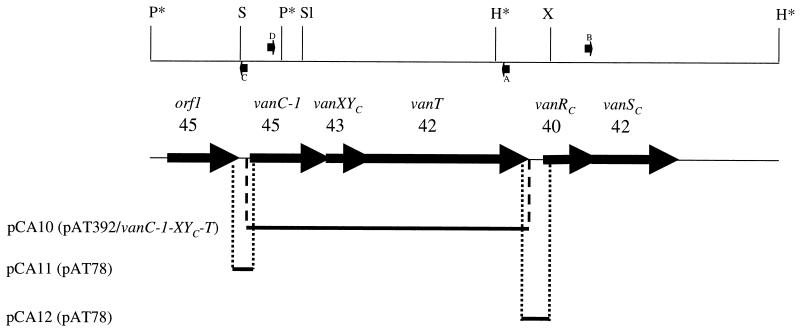

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the vanC gene cluster. The fragments cloned in plasmids pCA10, pCA11, and pCA12 are indicated by thin solid lines. Thick arrows represent coding sequences and indicate the direction of transcription. The fragment cloned into pCA11 contains the intergenic region between orf1 and vanC-1 including the 3′ end of orf1 and the 5′ end of vanC-1. The insert of plasmid pCA12 contains the intergenic region between vanT and vanRC (including the 3′ end of vanT and the 5′ end of vanRC). Cloning of the inserts of pCA8 and pCA9 was performed by inverse PCR using oligonucleotides A, B, C, and D (represented by small arrows) containing SacI and XbaI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, after digestion and self-religation of total DNA from E. gallinarum BM4174 with HindIII and PvuI (asterisks). Numbers above each gene indicate the percentage of GC. Restriction sites: P, PvuI; S, SacI; Sl, SalI; H, HindIII; X, XbaI.

DNA manipulations.

E. gallinarum BM4174 total DNA was extracted as described earlier (32). Cloning, digestion with restriction endonucleases (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), isolation of plasmid DNA (Wizard Plus SV Minipreps; Promega), ligation, and transformation were carried out by standard methods (38). Plasmid constructs based on pAT392 (5) and pAT78 (3) were purified from E. coli and electroporated into E. faecalis JH2-2 and E. gallinarum BM4174, respectively, as described elsewhere (14).

Cloning and sequencing of the vanRC and vanSC genes.

The sequences of the vanRC gene and the 5′ end of the vanSC gene were obtained from plasmid pCA1 (2). The remaining portion of the vanSC gene was obtained by inverse PCR (28) after digestion of chromosomal DNA with HindIII. A digoxigenin (Boehringer-Mannheim)-labeled probe from the 5′ end of the vanSC gene hybridized (41) to a 3.6-kb HindIII fragment of chromosomal DNA. Total DNA was then digested with HindIII and self-ligated at 16°C for 16 h at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. The inverse PCR with Pwo polymerase (Boehringer-Mannheim) was performed with primers A and B (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The PCR product obtained had the expected size of 2.5 kb based on the size of the HindIII fragment and the oligonucleotides used as primers. This product was used in the construction of pCA8.

TABLE 2.

Primers used

| Primer | Sequence | Origin nta (source or reference) | Relevant properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 5′-GTAATCTAGAGAACGGGGCAGTCCGTC | 1915–1899 (1) | XbaI site (underlined) |

| B | 5′-CTAAGAGCTCCTTGCTGGCATTCCTTG | 890–906 (Fig. 2) | SacI site (underlined) |

| C | 5′-GTAATCTAGAGGGCTTGAAGAAAGCAG | 1122–1107 (Fig. 5) | XbaI site (underlined) |

| D | 5′-CTAAGAGCTCAGTATGGCGAGGATGG | 1544–1559 (Fig. 5) | SacI site (underlined) |

| E | 5′-CTCGGAGCTCAAGAAAAAAGGAAAGGAAG | 1227–1245 (Fig. 5) | SacI site (underlined); RBS vanC-1 (italics) |

| F | 5′-GTAATCTAGACTATTTGATCCTAGCAC | 2144–2122 (1) | XbaI site (underlined); stop codon vanT (italics) |

| G | 5′-CTCAGGATCCTCCATGACTGTGATGGC | 655–671 (Fig. 5) | BamHI site (underlined) |

| H | 5′-GCTCGTCGACCTTCATATTTCAGCGGG | 1357–1341 (Fig. 5) | SalI site (underlined) |

| I | 5′-CTCAGGATCCCATCGGCTATTGTGACG | 1886–1902 (1) | BamHI site (underlined) |

| J | 5′-GCTCGTCGACCAATATAGGCGATGGCAC | 269–252 (Fig. 2) | SalI site (underlined) |

Numbers correspond to the position (nucleotides) of the priming oligonucleotides in the relevant gene.

Cloning of DNA upstream from the vanC-1 gene.

Cloning of DNA upstream from the vanC-1 gene (15) was performed by inverse PCR (28). In brief, a digoxigenin-labeled probe from the 5′ end of vanC-1 hybridized (41) to a 1.8-kb PvuI fragment. Chromosomal DNA was digested with PvuI and self-ligated as described above. PCR with Pwo polymerase was performed with primers C and D (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The PCR product obtained was of the expected size of 1.4 kb. The fragment was used in the construction of pCA9.

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid pCA1 has been described (2). For construction of plasmids pCA8 and pCA9, the 2.5- and 1.4-kb SacI-XbaI inverse PCR products were purified with a commercial kit (QIAquick Gel Purification Kit; Qiagen), digested with SacI and XbaI, and ligated with pUC18 DNA digested with the same enzymes: the insert in plasmid pCA8 contained DNA downstream from the extreme 5′ end of vanSC, and the region upstream from vanC-1 was present in plasmid pCA9 (Table 1). Plasmid pCA10 was constructed by cloning a PCR product containing the vanC-1, vanXYC, and vanT genes obtained after amplification of E. gallinarum BM4174 chromosomal DNA with primers E and F (Table 2). The product was digested with SacI and XbaI, purified, and cloned, under the control of the P2 promoter to allow constitutive expression of the gene products, into pAT392 (5) digested with the same enzymes. For construction of plasmid pCA11, DNA containing the orf1–vanC-1 intergenic region and the 3′ and 5′ ends of orf1 and vanC-1, respectively (Fig. 1), was amplified (using Pwo polymerase) with primers G and H (Table 2) using the total DNA of E. gallinarum BM4174 as a template. The 703-bp fragment, corresponding to nucleotides 655 to 1357 (see Fig. 3), was digested with BamHI and SalI and ligated to pAT78 DNA (3) digested with the same enzymes. Similarly, a DNA fragment from E. gallinarum BM4174 containing the vanT-vanRC intergenic region and the 3′ and 5′ ends of vanT and vanRC, respectively (Fig. 1), was amplified using primers I and J (Table 2). The 473-bp PCR fragment was digested with BamHI and SalI, purified, and ligated with pAT78 DNA (3) digested with the same enzymes to obtain plasmid pCA12. The cloning was designed to position both fragments upstream from the promoterless chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene cat in pAT78 (3).

FIG. 3.

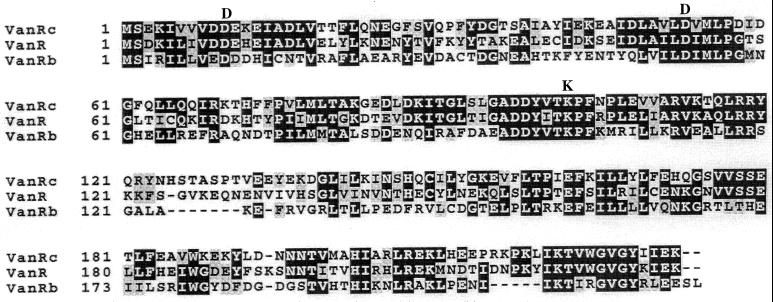

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of VanRc from E. gallinarum BM4174, VanR from E. faecium BM4147 (3), and VanRb from E. faecalis V583 (16). The alignment was made by using CLUSTAL W (18). Numbers at the left correspond to the position of the first amino acid in the corresponding line. Black boxes indicate amino acid identity, and shaded boxes indicate similar amino acids. Asp10, Asp53, and Lys102 in VanRC, which are conserved in the effector domain of other response regulators (42), are indicated above the alignment. Asp53 of VanR is phosphorylated by the associated histidine kinase VanS (40).

DNA sequence and accession numbers.

Sequencing of the inserts in pCA8 and pCA9 (two independent clones of each) was performed by the dideoxy chain terminator method (39) using fluorescent cycle sequencing with dye-labeled terminators (ABI Prism TM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit; Perkin-Elmer) on a 373A automated DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). The nucleotide sequences have been deposited in GenBank (accession number AF162694).

Extraction and analysis of peptidoglycan precursors from E. faecalis JH2-2/pCA10 (vanC-1 vanXYC vanT).

Extraction and analysis of peptidoglycan precursors were performed as described elsewhere (34). In brief, enterococci were grown in BHY medium supplemented with d-Ser or l-Ser or in the absence of any supplement. Ramoplanin was added to inhibit peptidoglycan synthesis and incubation continued for 15 min to cause accumulation of peptidoglycan precursors. Bacteria were harvested, and cytoplasmic precursors were extracted and analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

d,d-Dipeptidase and CAT activities.

d,d-Dipeptidase activity was measured in cytoplasmic extracts of E. gallinarum BM4174 grown in the presence or absence of vancomycin (4 μg/ml). The amount of d-Ala released from d-Ala–d-Ala was determined using a d-amino acid oxidase assay coupled to peroxidase (24). For CAT activity, E. gallinarum BM4174 and the same strain containing pAT78, pCA11, or pCA12 were grown to an optical density of 0.8 at 600 nm in BHY medium supplemented with spectinomycin (480 μg/ml) to prevent the loss of pAT78 and derivatives. The cells were lysed with lysozyme and M1 muramidase as described earlier (2). Cytoplasmic extracts obtained after centrifugation at 40,000 × g for 20 min were tested for the formation of 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate at 37°C in the presence or absence of chloramphenicol in 5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) (3). Protein concentrations were determined according to the method of Bradford (10) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nucleotide sequences of the vanRC and vanSC genes.

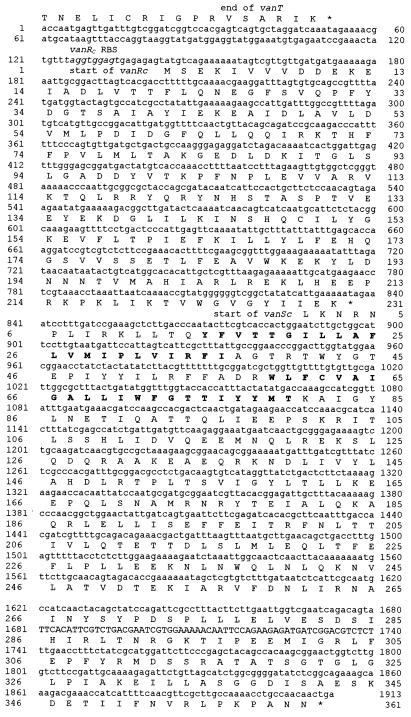

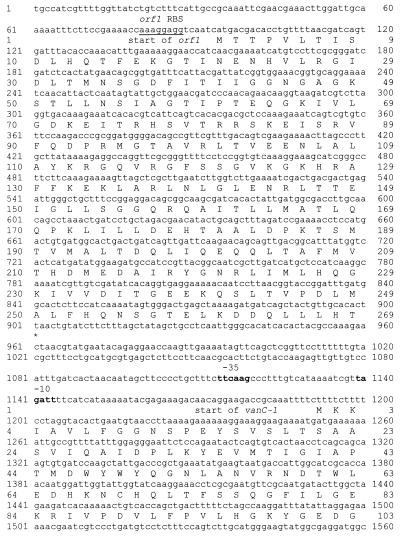

The sequences of the vanRC and vanSC genes (Fig. 2) were obtained by sequencing on both strands the inserts of plasmids pCA1 (2) and pCA8. vanR extended from nucleotides 143 to 838. The proposed initiation codon was preceded by a sequence (5′-TAGGTGGAGT N8 ATG) with similarity to ribosome binding sites (RBS) of gram-positive bacteria (25) and displayed limited complementarity (underlined) to the 3′-OH terminus of Bacillus subtilis 16S rRNA (3′-OH UCUUUCCUCC). The sequence encoded a putative protein of 231 amino acids (Mr, 26,523) designated VanRC. There was no obvious translation start site in the second open reading frame (ORF) downstream from vanRC. The amino acid sequence deduced from the ORF starting at the first putative in-frame initiation codon (TTG at position 828, Fig. 2) would correspond to a protein of 361 amino acids (Mr, 41,462) that was designated VanSC. Other in-frame putative initiation codons (TTG at positions 846 and 861) were also not preceded by obvious RBS. The organization of vanRC-vanSC is similar to that described for vanR-vanS in VanA-type strains, including the overlap of the two genes, the TTG start codon and no obvious RBS preceding the start of the vanS gene (3). Moreover, although the genes encoding the putative regulatory proteins were found downstream from the resistance genes it is likely that they are involved in the regulation of the vancomycin resistance gene cluster: other genes encoding proteins which could be involved in vancomycin resistance were not found downstream from vanRC-vanSC; instead, a gene encoding a putative d-Ala–d-Ala ligase was found downstream from vanSC but in opposite orientation to the five genes of the vanC cluster (C. A. Arias and P. E. Reynolds, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-84, 1998).

FIG. 2.

Sequence of the vanRC and vanSC genes. The deduced amino acid sequences are shown below the nucleotide sequence. The deduced amino acid sequence of the C terminus of VanT is shown above the nucleotide sequence. Clusters of hydrophobic amino acids in VanSC predicted to represent transmembrane regions (21) are shown in boldface. The putative RBS of vanRC is indicated in italics.

Amino acid sequence comparisons of VanRC and VanSC.

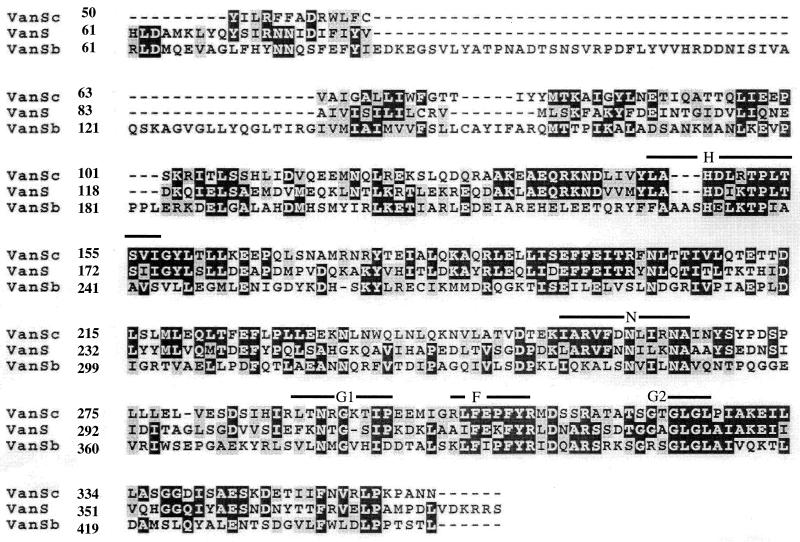

The highest score of a BLAST (1) search of the OWL protein sequence database was obtained with VanR from E. faecium BM4147 (3): VanRC had the same number of amino acid residues (231 residues) as VanR and displayed 50% identity (3). The protein with the next highest degree of identity was the GtcR putative response regulator from Bacillus brevis (43) (41% identity over 229 amino acids). VanRC exhibited only 33% identity with VanRB (16). The conserved lysine and aspartate residues typical of response regulators (42) of two-component regulatory systems were also present in VanRC (Lys102, Asp10, and Asp53) (Fig. 3). The high degree of identity between VanRC and VanR suggests an evolutionary relatedness. VanSC had 40% identity with VanS over a region of 308 amino acids (highest BLAST score) and 24% with VanSB over a region of 285 amino acids. The highest degree of identity between VanSC, VanS, and VanSB was found in the C-terminal region. VanSC contained the five conserved motifs characteristic of transmitter modules of histidine protein kinases (Fig. 4) (19). A hydrophobicity plot (23) of the N-terminal domain of VanSC indicated two clusters of hydrophobic amino acids that may correspond to transmembrane regions (Fig. 2), as in the sensor domains of VanS and VanSB (7). The structural homology of VanRC and VanSC with proteins of the two-component regulatory systems in VanA-type strains further supports the fact that a similar signal-transducing system controlling the expression of proteins involved in vancomycin resistance is likely to be present in E. gallinarum BM4174.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of VanSc from E. gallinarum BM4174, VanS from E. faecium BM4147 (3), and VanSb from E. faecalis V583 (16). The alignment was made using CLUSTAL W (18). Numbers at the left correspond to the position of the first amino acid in the corresponding line. Black boxes indicate the amino acid identity, and shaded boxes indicate similar amino acids. Conserved sequence motifs H, N, G1, F, and G2 (29) are indicated above the alignment. His147 in VanSC corresponds to the putative autophosphorylation site.

Nucleotide sequence upstream from vanC-1.

The sequence upstream from vanC-1 revealed an ORF with a proposed initiation codon preceded by a putative RBS. The 810-bp sequence from position 94 to 903 (Fig. 5) encoded a putative 269-amino-acid protein (Mr, 29,718) that was designated ORF1. The intergenic region between orf1 and the start of vanC-1 contained 348 bp (Fig. 5). ORF1 had homology (32 to 35% identity over 215 to 226 amino acids) to ATP-binding transporter proteins (ABC transporters) from different organisms (PotG from Rickettsia prowazekii, NrtC from Oscillatoriacean cyanobacterium, and PotA from Haemophilus influenzae). This type of protein has not previously been associated with glycopeptide resistance and was not necessary for vancomycin resistance in E. gallinarum BM4174 (see below): therefore, ORF1 is unlikely to be part of the vanC gene cluster.

FIG. 5.

Sequence of orf1 upstream from the vanC-1 gene. The deduced amino acid sequence is shown below the nucleotide sequence. The deduced amino acid sequence of the N terminus of VanC-1 is shown above the nucleotide sequence. The putative RBS of orf1 is underlined. The hexanucleotides exhibiting similarity to the −35 (TTGATC) and −10 (TAGACT) consensus promoter sequences (from PvanH of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium) (20) (underlined above) are shown in boldface.

Constitutive synthesis of d,d-dipeptidase in E. gallinarum BM4174.

The presence of genes encoding a two-component regulatory system, adjacent to the resistance genes, prompted us to study the influence of vancomycin on the expression of the resistance genes. d,d-Dipeptidase activity, used as a reporter, was not increased after growth in the presence of vancomycin, indicating that the antibiotic did not have an upregulating effect on expression of the resistance genes (Table 3) and that vancomycin resistance was expressed constitutively in BM4174. However, strains of E. gallinarum that exhibit inducible expression of resistance have also been described (37). We have characterized 15 strains of vancomycin-resistant E. gallinarum which express the resistance phenotype either constitutively (seven strains) or inducibly (eight strains); using PCR we were able to identify and sequence the vanRC-vanSC genes in all isolates. Additionally, in all strains, the genes were detected downstream from vanT as in E. gallinarum BM4174 (C. A. Arias, D. Panesso, and P. E. Reynolds, unpublished data). These findings indicate that the vanRC and vanSC genes are most likely to play a role in the regulation of the resistance genes. Mutations in the H box of the histidine kinase domain of VanSB have been shown to convert an inducible to a constitutive glycopeptide resistance phenotype (5, 6, 44). Alignment of the predicted amino acid sequence in the H box of VanSC with VanSB (Fig. 4) indicated that these mutations were not present in VanSC. In vivo characterization of VanSB in E. coli has shown that VanSB functioned only as a phosphatase with no kinase activity (38). If VanSC in E. gallinarum BM4174 were to function in a similar way as VanS or VanSB a constitutive phenotype could result from a protein that had kinase but no phosphatase activity or was lacking both activities. A functional analysis of the VanRC-VanSC two-component regulatory system in E. gallinarum is currently in progress to clarify this issue.

TABLE 3.

CAT and d,d-dipeptidase activities of and chloramphenicol MICs for E. gallinarum BM4174 and derivatives

| Strain | Sp acta (nmol/min/mg of protein) of:

|

Chloramphenicol MIC (μg/ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAT | d,d-Dipeptidase | ||

| BM4174 | 0 | 92 ± 15.3 (without Van), 73 ± 8.9 (with Van)b | 8 |

| BM4174/pAT78 | 110 ± 41 | 16 | |

| BM4174/pCA11 | 5,889 ± 2,707 | 64 | |

| BM4174/pCA12 | 5,314 ± 128 | 64 | |

CAT and d,d-dipeptidase activities were determined in the absence of vancomycin. Values are the means and standard deviations from three independent experiments.

Vancomycin (Van) at 4 μg/ml was added to the growth medium to test for the induction of d,d-dipeptidase activity.

trans-activation of transcription of cat.

Plasmids pCA11 and pCA12 (Fig. 1) contained, respectively, the orf1–vanC-1 intergenic region (including the 3′ end of orf1 and the 5′ end of vanC-1) and the vanT-vanRC intergenic region (including the 3′ end of vanT and the 5′ end of vanRC) cloned upstream from the promoterless cat gene of pAT78 (3). Both plasmids increased the MIC of chloramphenicol against E. gallinarum BM4174 eightfold, and the CAT activity was increased ca. 50-fold relative to the strain harboring pAT78 only (Table 3). These data indicated that DNA regions upstream from both the vanC-1 and vanRC genes could function as promoters and allowed trans-activation of cat transcription.

Genes necessary for vancomycin resistance in E. gallinarum BM4174.

Plasmid pCA10 was obtained by cloning into pAT392 a fragment containing the vanC-1, vanXYC, and vanT genes to allow constitutive expression of the genes under the control of the P2 promoter (5). Electroporation of pCA10 DNA into E. faecalis JH2-2 led to a fourfold increase in the vancomycin MIC (Table 3). Analysis of peptidoglycan precursors indicated production of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ser] (23% of total precursor pool), reflecting both VanC-1 and VanT activities and of UDP-MurNAc tetrapeptide (74% of the total precursor pool) resulting from hydrolysis of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ala] by the d,d-carboxypeptidase activity of VanXYC (Table 4). Presence of either l-Ser or d-Ser in the growth medium slightly increased the percentage of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ser] synthesized by the host (40 and 38%, respectively), although it had no effect on the level of resistance to vancomycin (Table 4). The stop codons of vanC-1 and vanXYC overlap the initiation codons of vanXYC and vanT, respectively (2, 36), suggesting that translational coupling may play a role in expression of the resistance proteins. The data also confirm that the metabolic pathway for the synthesis of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ser] in E. gallinarum BM4174 involves racemization of l-serine by VanT (a membrane-bound serine racemase) (2), followed by synthesis of d-Ala-d-Ser (29) which is added to UDP-MurNAc-l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-l-Lys. In order to eliminate “susceptible” precursors (ending in d-Ala), hydrolysis of d-Ala-d-Ala (d,d-dipeptidase activity) and removal of d-Ala from UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide (d,d-carboxypeptidase activity) occurs (36). These two functions are catalyzed by a single protein (VanXYC) (36), unlike the VanA and VanB phenotypes in which two polypeptides (VanX/VanY or VanXB/VanYB) are necessary (5, 33). Peptidoglycan precursor analysis (Table 4) indicates that both activities are required for the successful removal of “susceptible” precursors: a considerable proportion of accumulated tetrapeptide suggests that elimination of d-Ala-d-Ala is not complete.

TABLE 4.

Peptidoglycan precursors and vancomycin MICs for E. faecalis JH2-2 and derivatives under different growth conditions

| E. faecalis strain | Medium supplementa | Peptidoglycan precursors (%)b

|

Vancomycin MIC (μg/ml) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ala] | UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide[Ser] | UDP-MurNAc-tetrapeptide | |||

| JH2-2 | None | 100 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| JH2-2/pCA10 (vanC-1 vanXYC vanT) | None | 3 | 23 | 74 | 8 |

| JH2-2/pCA10 (vanC-1 vanXYC vanT) | d-Serine | 6 | 38 | 56 | 8 |

| JH2-2/pCA10 (vanC-1 vanXYC vanT) | l-Serine | 6 | 40 | 54 | 8 |

The concentrations of d- and l-serine were 50 mM.

Determined by HPLC from the integrated peak areas.

In summary, the vanC gene cluster is considered to comprise five genes, vanC-1, vanXYC, vanT, vanRC, and vanSC. The gene organization differs from that in the vanA, vanB, and vanD gene clusters (12; Arias and Reynolds, 38th ICAAC) in that the vanRC-vanSC genes are positioned downstream from the resistance genes. The presence of VanC-1, VanXYC, and VanT is necessary and sufficient for resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

C.A.A. is funded by COLCIENCIAS (Instituto Colombiano para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y Tecnología, “Francisco José de Caldas”) and the Overseas Research Scheme Award from the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals of Universities in the United Kingdom. Part of this work was carried out while C.A.A. was the recipient of a British Infection Society/Hoechst-Marion-Roussel Travel Bursary held at the Institut Pasteur, Paris, France. This work was supported in part by the Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie, Maladies infectieuses et parasitaires from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie. We are grateful to the Cambridge Overseas Trust and T. Blundell, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, for personal financial assistance to C.A.A.

We thank M. Arthur for helpful discussions and J. Lester and C. Hill, Cambridge Center for Molecular Recognition, for DNA sequencing and synthesis of oligonucleotides, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arias C A, Martín-Martinez M, Blundell T L, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Reynolds P E. Characterization and modelling of VanT, a novel, membrane-bound, serine racemase from vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1653–1664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P. The VanS-VanR two- component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2582–2591. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2582-2591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur M, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Snaith H A, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. Contribution of VanY d,d-carboxypeptidase to glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis by hydrolysis of peptidoglycan precursors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1899–1903. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthur M, Molinas C, Dutka-Malen S, Courvalin P. Structural relationship between the vancomycin resistance protein VanH and 2-hydroxycarboxylic acid dehydrogenases. Gene. 1991;103:133–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90405-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baptista M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P, Arthur M. Mutations leading to increased levels of resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics in VanB-type enterococci. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:93–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4401812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baptista M, Rodrigues P, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Arthur M. Single-cell analysis of glycopeptide resistance gene expression in teicoplanin-resistant mutants of a VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:17–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billot-Klein D, Gutmann L, Sable S, Guitet E, van Heijenoort J. Association constants for the binding of vancomycin and teicoplanin to N-acetyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine and N-acetyl-d-alanyl-d-serine. Biochem J. 1994;304:1021–1022. doi: 10.1042/bj3041021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugg T D H, Wright G D, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh C T. Molecular basis for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147: biosynthesis of a depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursor by vancomycin resistance proteins VanH and VanA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10408–10415. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullock W O, Fernandez J M, Short J M. XL1-Blue—a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta-galactosidase selection. BioTechniques. 1987;5:376. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casadewall B, Courvalin P. Characterization of the vanD glycopeptide resistance gene cluster from Enterococcus faecium BM4339. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3644–3648. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3644-3648.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruz-Rodz A L, Gilmore M S. High efficiency introduction of plasmid DNA into glycine-treated Enterococcus faecalis by electroporation. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:152–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00259462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutka-Malen S, Molinas C, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Sequence of the vanC gene of Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174 encoding a d-alanine:d-alanine ligase-related protein necessary for vancomycin resistance. Gene. 1992;112:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evers S, Courvalin P. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanSB-VanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1302-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fines M, Perichon B, Reynolds P, Sahm D F, Courvalin P. VanE, a new type of acquired glycopeptide resistance in Enterococcus faecalis BM4405. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2161–2164. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins D G, Thompson J D, Gibson T J. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 1996;266:383–402. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)66024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holman T R, Wu Z, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Identification of the DNA-binding site for the phosphorylated VanR protein required for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4625–4631. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmann K, Stoffel W. TMBase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1993;374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob A E, Hobbs S J. Conjugal transfer of plasmid-borne multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus faecalis var. zymogenes. J Bacteriol. 1974;174:5982–5984. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.2.360-372.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Messer J, Reynolds P E. Modified peptidoglycan precursors produced by glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;94:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90608-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran C P, Lang N, LeGrice S F J, Lee G, Stephens M, Sonenshein A L, Pero J, Losick R. Nucleotide sequences that signal the initiation of transcription and translation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;186:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00729452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navarro F, Courvalin P. Analysis of genes encoding d-alanine:d-alanine ligase-related enzymes in Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus flavescens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norrander J, Kempe T, Messing J. Construction of improved M13 vectors using oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Gene. 1983;26:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochman H, Gerber A S, Hart D L. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase reaction. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park I S, Chung-Hung L, Walsh C T. Bacterial resistance to vancomycin: overproduction, purification, and characterization of VanC-2 from Enterococcus casseliflavus as a d-Ala:d-Ser ligase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10040–10044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacterial signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perichon B, Reynolds P E, Courvalin P. VanD-type glycopeptide-resistant Enterococcus faecium BM4339. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2016–2018. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidinium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds P E, Depardieu F, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance mediated by enterococcal transposon Tn1546 requires VanX for hydrolysis of d-alanyl-d-alanine. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1065–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds P E, Snaith H A, Maguire A J, Dutka-Malen S, Courvalin P. Analysis of peptidoglycan precursors in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Biochem J. 1994;301:5–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds P E. Control of peptidoglycan synthesis in vancomycin-resistant enterococci: d,d-peptidases and d,d-carboxypeptidases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s000180050159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reynolds P E, Arias C A, Courvalin P. Gene vanXYC encodes both d,d-dipeptidase (VanX) and d,d-carboxypeptidase (VanY) activities in vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus gallinarum BM4174. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:341–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahm D F, Free L, Handwerger S. Inducible and constitutive expression of vanC-1-encoded resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus gallinarum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1480–1484. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.7.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva J C, Haldimann A, Prahalad M K, Walsh C T, Wanner B L. In vivo characterization of type A and B vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) VanRS two-component systems in Escherichia coli: a nonpathogenic model for studying the VRE signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11951–11956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stock J B, Ninfa A J, Stock A M. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:450–490. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.450-490.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turgay K, Marahiel M A. The gtcRS operon coding for two-component system regulatory proteins is located adjacent to the grs operon of Bacillus brevis. DNA Seq. 1995;5:283–290. doi: 10.3109/10425179509030982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Bambeke F, Chauvel M, Reynolds P E, Fraimow H, Courvalin P. Vancomycin-dependent Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolates and revertant mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:41–47. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]