Abstract

As autistic adolescents and young adults navigate the transition to adulthood, there is a need to partner with them to identify strengths and needed supports to enable goal-directed actions. This article conceptually integrates research on self-determination, defined by Causal Agency Theory, and executive processes in autism to provide direction for future research and practice. We describe how integrating research on self-determination and executive processes could enable autistic adolescents and young adults to be engaged in the process of assessing executive processes and self-determination. We discuss how this can better inform personalization of supports for self-determination interventions by focusing on support needs related to executive processes, including inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility, from a strengths-based perspective. We discuss how this can enable self-determination interventions that promote outcomes aligned with the values of the autistic community.

Keywords: self-determination, executive processes, autistic youth

Lay summary

Why is this topic important?

Self-determination is about having opportunities and supports to make or cause things to happen in your life. Research over the past 25 years has shown that self-determined young people have more positive employment, postsecondary education, and community participation outcomes. Self-determined people set and go after goals that are important to them and use an understanding of their strengths and support needs and the resources available to them in their communities. During the transition to adulthood, autistic adolescents and young adults can benefit from supports for self-determination and executive processes such as inhibitory control (keeping attention on something even if there are distractions) and cognitive flexibility (changing actions based on what goal a person is working toward). To personalize self-determination interventions, understanding self-determination and executive process abilities is important.

What is the purpose of this article?

The purpose of this article was to introduce new ways of thinking about the relationship between self-determination (making or causing things to happen in your life) and executive processes (a set of abilities people use as they work toward goals). This article describes ways that integrating research on self-determination and executive processes can lead to more effective personalized supports for autistic adolescents and young adults. It also highlights how autistic people can be engaged in these efforts.

What do the authors conclude?

We conclude that there is alignment between research on self-determination and executive processes. We describe how assessing self-determination and executive process abilities can be done in partnership with autistic adolescents and young adults and used to personalize interventions. We illustrate ways that supports for inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility can be integrated into existing self-determination interventions, such as the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction (SDLMI). We discuss how this integration can be used to provide meaningful personalized supports that are aligned to each autistic person's identified areas of strengths and need as well as their goals for the future. Better understanding the relationship between executive processes and self-determination can support autistic young people to become more self-determined.

What do the authors recommend for future research on this topic?

We recommend future research focused on using different assessments of self-determination and executive process to identify support needs and personalize self-determination interventions. We also recommend research focus on how to embed supports for executive processes in self-determination intervention, such as the SDLMI. We emphasize the importance of participatory research approaches that directly engage the autistic community and autistic researchers in identifying meaningful supports.

How will these recommendations help autistic adults now or in the future?

New approaches to understanding self-determination and executive process can lead to better ways to support autistic adolescents and young adults to use their strengths to go after goals that matter to them. There are many opportunities to build more effective supports, in partnership with autistic advocates and researchers, that address the values and vision of the autistic community.

Introduction

Studies consistently find that self-determination predicts enhanced outcomes during the transition from school to adult life across disability populations, including for autistic youth and young adults.1,2 Self-determination gained attention in the disability field to actualize the values of the disability rights and self-advocacy movements, namely the inherent right of people with disabilities to direct their own lives with the supports needed to do so.3,4 In the late 1990s, disability leaders began to advocate for grant funding to develop strategies to create opportunities and supports for self-determination, primarily targeting transition-age adolescents in school contexts.5 As a result, a robust literature emerged in early 2000s, demonstrating the feasibility of systemic change to create opportunities for the development of self-determination in special education transition planning across populations.6,7 Initial work drew on multiple theories and research bases including existing literature on self-regulation and executive functioning.8 However, the relationship between self-determination interventions and related theories for understanding executive processes in autism has never been fully explicated.

In this article, we conceptually analyze the research literature to explore the connections between self-determination and specific executive processes in autistic adolescents and young adults. We discuss the potential of using self-report measures of self-determination alongside objective measures of executive processes to provide complementary information to guide personalization of interventions and outcome tracking. We highlight how engaging the autistic community in collecting a range of assessment data can ensure the values and needs of autistic adolescents and young adults are integrated into personalized self-determination interventions to promote greater self-direction of goal-directed actions.

Integrating theory and research on self-determination and executive processes has the potential to advance positive outcomes for autistic young people. First, this integration could create opportunities for the expansion of self-determination assessment and intervention research outside the special education and transition fields through greater alignment with research focused on executive processes. Second, this innovation could expand the focus on the engaging autistic advocates in the process of assessing self-determination and executive processes. Third, identifying and addressing disability-related support needs through assessment has the potential to enable personalization of self-determination interventions to the strengths and needs of autistic adolescents and young adults. Given the highly disparate outcomes experienced by autistic youth in comparison to those without disabilities as well as other disability populations, this line of work is critical to support future research, practice, and policy.9

Why Self-Determination?

It is reasonable to ask, particularly given the range of terminology used to define the executive processes that impact outcomes of young people with disabilities, including autism: Why focus on self-determination? Why is innovation in theory related to self-determination important to guide assessment and intervention to promote positive outcomes across the life course, particularly during the transition from adolescence to adulthood? First, as noted previously, the terminology adopted in self-determination research and practice emerged largely from the voices and advocacy of people with disabilities. Advocates across disability populations have consistently used the term self-determination to describe their right to self-direct their own lives. The impact of this advocacy has been significant, particularly in policy. Self-determination is a key value and outcome targeted in disability policies and human right treaties enacted over the past 30 years. The right to self-determination also continues to be a rallying cry in the self-advocate community.4 For example, the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN) states, “disability is a natural part of human diversity. Autism is something we are born with, and that shouldn't be changed. Autistic children should get the support they need to grow up into happy, self-determined autistic adults.”10

Second, interventions to promote self-determination have been developed that can support people with disabilities to take steps toward self-directed lives. Such interventions can be personalized based on strengths, interests, and supports. There is the inherent diversity in the autistic community (e.g., “There is no one way to be autistic”).11 Understanding each autistic person's strengths and support needs, from their perspective, must be a focus of self-determination interventions particularly during the transition to adulthood when there are new and changing demands.12,13 A focus on engaging autistic adolescents and young adults in assessment and intervention development can maintain the focus on the adage of the disability rights movement, “nothing about us, without us.”14 This focus also recognizes the importance of enabling the dignity of risk15 and broader movements for participatory research.16,17 New conceptual models, as described in this article, that integrate self-determination and executive process research have the potential to advance intervention to promote self-determination and embed disability advocacy in self-determination assessment, intervention, and supports.18–22

Causal Agency Theory

Causal Agency Theory23 updated existing self-determination theories that emerged in the disability field in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Casual Agency Theory integrated the perspectives of people with disabilities on the meaning of self-determination in their lives with research across education and psychology.3,19,24 Causal Agency Theory defines self-determination as a psychological construct within the organizing structure of theories of human agentic behavior.23,25 Agentic theories view humans as active contributors to, or agents of, their behavior. Agentic theories hold that people as engage in self-regulated and goal-directed action they enhance their sense of personal agency.26 The development of a sense of personal agency is facilitated by environments that are supportive of self-determination and limited by environments that create barriers through ableist policies and practices.

Advancing the use of agentic theories creates an opportunity for a greater focus on the role of autistic adolescents in shaping and directing their own lives and goal-directed actions. For example, an autistic adolescent preparing for the transition from school to adult life can actively build self-determination abilities as they continually and iteratively explore postsecondary options (e.g., attending a college/university or nontraditional program), setting goals and taking steps to achieve those goals, with supports (e.g., college and career or transition counselor, peers engaging transition planning). Similarly, an autistic adolescent can build self-determination abilities as they explore ways they prefer to engage socially and in relationships they choose to build in their community. Based on their decision to enhance social relationships, an autistic adolescent might set a goal to explore online discussion forums based on interests or hobbies (e.g., online gaming, sports) to see how getting to know people via online communities works for them and also look into social groups in their community that are interesting to them based on common hobbies or activities (e.g., art, cooking). The autistic adolescent may also ask trusted supporters for their feedback and experiences with various options. Then, the autistic adolescent can decide what works best for them and use that knowledge to work toward their overall goal of creating, enhancing, and maintaining social relationships.

Causal Agency Theory recognizes the interdependence of goal setting for all people and the role of context in shaping the expression of self-determination abilities. A self-determined person has agency over their goal-directed actions, even if that means empowering others to make or implement decisions based the values, preferences, and beliefs communicated by the person. Young people with disabilities frequently identify acting in self-determined ways as critically important during the transition from school to adult life. For example, in one study, when autistic students were asked to rate their strengths and learning priorities they identified goal setting and attainment (two key foci of self-determined actions as defined by Causal Agency Theory) as their highest priorities for life after high school. They also noted the importance of receiving support from teachers and peers aligned with these priorities.22

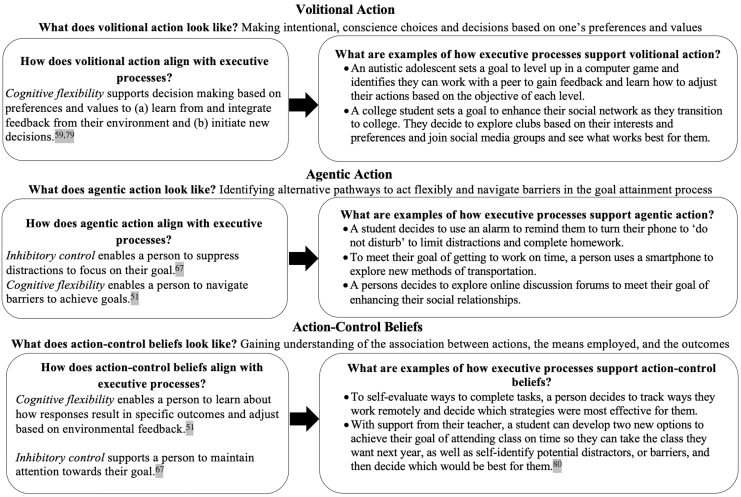

Causal Agency Theory provides a framework for how to support autistic adolescents and young adults to develop self-determination by focusing on the development of three key abilities: volitional action, agentic action, and action-control beliefs (see definitions in Fig. 1). Causal Agency Theory also highlights why young people engaged in self-determined activities by describing the role of environments that support autonomy, competence, and relatedness to create motivation, consistent with self-determination theory.27 As autistic young people gain experience navigating new environments (e.g., postsecondary education, employment, social and community participation) across the life course, they can utilize volitional and agentic actions as well as action-control beliefs to meet their needs related to autonomy, competence, and relatedness to make progress toward freely chosen and personally meaningful goals.

FIG. 1.

Conceptual alignment of self-determination abilities and executive process research: implications for personalized supports.

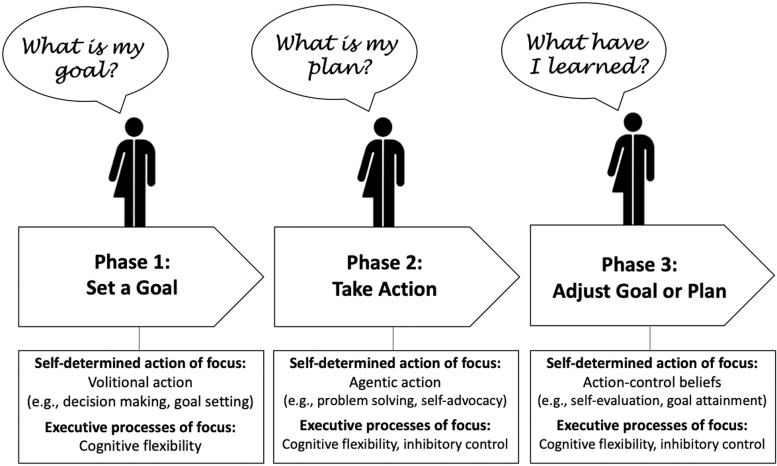

Causal Agency Theory: assessment and intervention

Causal Agency Theory has led to the development of assessments, such as the Self-Determination Inventory28 (SDI). The SDI enables young people to self-report on their perceptions of their self-determination abilities. The SDI includes items that assess three self-determined abilities defined by Causal Agency Theory: volitional action, agentic action, and action-control beliefs. The SDI has been used to guide intervention design as well as to evaluate the impact of self-determination intervention on outcomes of young people with disabilities.29,30 Relatedly, intervention approaches, such as the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction31 (SDLMI), have been developed to support growth in self-determination abilities. The SDLMI has been delivered by trained facilitators (e.g., general and special educators, transition coordinators, disability provider agency case managers, self-advocates) to engage young people with and without disabilities in applying self-determination abilities to self-directed goals. Young people learn a series of questions and practice key abilities as they are supported to work through the three phases of the SDLMI: Set A Goal, Take Action, and Adjust Goal or Plan (Fig. 2). The structured three-phase approach taught through the SDLMI supports self-regulated problem-solving skills in service to a goal and can be used repeatedly by adolescents and young adults as they identify new goals across multiple life domains. Extensive evidence of the impact of SDLMI on outcomes across disability populations exists,32 and more information on the implementation of the SDLMI can be found in various sources.33,34

FIG. 2.

Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction: ways to target self-determination abilities and executive processes. Adapted with permission from Shogren et al.31

Executive Processes

Theories of executive processes draw from cognitive, clinical behavioral, and neurobiological frameworks and describe a range of constructs thought to drive goal-directed action.35 While theories of executive processes have notable distinctions, they also share considerable overlap.36–38 Executive processes consist of a regulatory component that is responsible for the activation and implementation of executive control processes to coordinate and adjust goal-directed behavior, as well as an evaluative component that is responsible for monitoring behavior, identifying when regulatory processes need to be modulated, and signaling when behavioral adjustments are necessary.39 Executive processes are considered essential for self-monitoring and modifying behavior to meet changing environmental demands and contingencies.

Executive processes also can also be subdivided into “cool” and “hot” processes. “Cool” executive processes include operations performed without influence of emotion, whereas “hot” executive processes are those performed during increased emotional arousal. For example, the process of stopping oneself from honking a car horn after being cut off in traffic (cold process) may be more challenging if the driver is stressed because they are going to be late to their destination (hot process). While few studies have systematically compared cool and hot executive processes in autism, numerous studies have documented diverse support needs associated with executive processes and emotion regulation in autistic youth. When effective supports for executive processes and emotion regulation are not available to autistic youth, researchers have found lower levels of adaptive behavior, socialization, and mental health.40,41 Multiple studies also have indicated that supports for executive processes during the transition to adulthood for autistic youth contribute to more positive outcomes.42–44 We posit that these supports should be personalized and informed by the vision and values of autistic adolescents.

Many studies assessing executive processes frame differences among the autistic population from a deficit-based perspective. However, increasingly researchers are recognizing that differences in executive processes may best be understood as reflecting neurodiversity and that any attempts to understand diversity in executive processes should be undertaken to better understand and personalize interventions.45,46 Researchers have suggested several specific patterns of differences that may be important to recognize. For example, some autistic people are more likely to show a risk-avoidance bias during behavioral decision-making compared with neurotypical people who show a greater tendency to select behaviors based on the likelihood that they will be rewarded.47,48 Some autistic people also show differing sensitivity to the context in which behavioral options are presented relative to neurotypical people, suggesting that their decision-making is less affected by emotion processing or regulation.47 These findings suggest that executive processes in autistic youth may be less impacted by emotion processes than in neurotypical youth. Traditional conceptualizations of “executive dysfunction” in autism do not adequately characterize the interacting processes that shape distinct decision-making approaches that are more common among autistic individuals. Meta-analyses in autistic populations have shown both variable expressions across executive processes49 as well as relatively similar component operations35 (e.g., cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, planning, problem solving). These meta-analytic findings suggest that multiple factors may influence executive processes, including a person's age, gender, or level of support needs. Recognizing the distinct decision-making approaches used by some autistic people will have important implications for personalizing interventions. Furthermore, understanding factors that can influence risk taking and risk aversion (e.g., previous trauma and opportunities to experience the dignity of risk) is necessary to make meaningful decisions about intervention personalization.

However, variation in the measures used to assess different executive processes may contribute to inconsistencies in research findings. For example, researchers have found differences on performance-based measures of executive abilities (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) when compared with parent report measures. These findings suggest that different types of measures can result in different indications of a person's executive processing abilities.50 These findings also suggest that ratings made by autistic youth and/or proxy-reporters may tap into distinct abilities that represent separate targets for intervention development and tracking intervention response. Integrating quantitative objective assessments of distinct executive processes with self-determination assessment could represent a novel approach to determine mechanisms of functional outcomes and characterize diversity across all people, as described subsequently. This could allow for more precise examination of the relations between specific executive processes and self-determination abilities, generating hypothesis for future research. Two distinct executive processes, cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control, are conceptually closely linked to self-determination (Fig. 1) and should be more robustly considered in ongoing work to promote self-determination outcomes in autistic youth.

Cognitive Flexibility

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to learn from and integrate feedback from one's environment and then adapt responses to changing contextual demands and relevant feedback.51–53 Cognitive flexibility shows a protracted course of development, including age-associated gains through adolescence and early adulthood.51 Cognitive flexibility has a broad developmental window during which interventions may have a significant impact for autistic adolescents, making cognitive flexibility a critically important area of focus during the transition to adulthood period. Autistic people demonstrate diversity in cognitive flexibility and researchers have linked this diversity with diagnostic criteria for autism: restricted and repetitive behaviors54–58 and social communication behaviors.59 Cognitive flexibility often is assessed in autistic people using traditional neuropsychological tests of executive functions, such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. During the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, people must select from a series of four stimuli the item that is correct. Stimuli vary along multiple dimensions (e.g., size, shape, color), and people must establish the correct sorting rule based on feedback following their selection. After a predetermined number of correct responses, the sorting rule is changed and the person must shift to a new sorting rule.

Studies of autistic people completing the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test consistently have indicated that autistic people show a heightened tendency to repeat errors despite feedback that they should shift to a new response set.60 The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test involves multiple separate cognitive operations (e.g., working memory, abstract thinking). Novel approaches are needed that more specifically assess set shifting and the selection of new choice behaviors. For these reasons, multiple testing strategies have been developed for assessment of cognitive flexibility across a broad range of age groups to more precisely inform differences in responding. For example, the Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) test is designed to assess cognitive flexibility while limiting demands on working memory and planning systems by providing people with explicit information regarding the target sorting rule.61 In studies spanning childhood to adolescence, autistic people show differences from neurotypical peers in flexibly shifting between sorting rules. Researchers have identified similar differences in cognitive flexibility with intradimensional/extradimensional tests, which assess people's ability to generalize and then flexibly shift between sorting rules. These findings suggest that autistic young people frequently generalize sorting rules but show diversity in their abilities to flexibly shift between response sets following a change in the correct sorting dimension.62,63

Building on this work with the goal of better understanding processes associated with cognitive flexibility, researchers developed a novel test of probabilistic reversal learning (PRL). The PRL probes a person's ability to select from two stimuli that vary along one dimension (location) and are reinforced on the majority of trials.64 Studies have documented differences in completion of PRL tasks in autistic people, suggesting a heightened preference for previously reinforced response choices.64,65 Studies have also suggested a greater focus on consistent reinforcement for maintaining new choice behaviors. For example, autistic people returned to a previously reinforced behavior after intermittent non-reinforcement (i.e., lose-shift errors) that was strongly associated with repetitive behavior intensity. These findings highlight the translational power of PRL tests of cognitive flexibility for pinpointing patterns that could inform personalized intervention approaches to enhance self-determination in autistic youth and young adults. For example, these results indicate that some autistic people may focus more on immediate reinforcement, which could inform planning for ways to build supports that promote sustained goal-directed actions.

Inhibitory Control

Inhibitory control is the ability to suppress attention or prepotent behaviors to adapt to environmental demands.66 It applies broadly to the ability to terminate, suppress, or regulate bottom-up processes, including attention and emotion responses. Inhibitory control is a necessary component of self-regulation, regulation of attention, and modifying behavior to meet environmental demands. Researchers have explored different types of inhibitory control in autistic people, including both prepotent response inhibition and distractor interference control.66,67 Prepotent response inhibition involves overriding or interrupting a dominant motor response before it is executed,67 whereas distractor interference control involves ignoring and selectively attending away an irrelevant stimulus (e.g., maintaining attention on a goal and inhibiting attention to extraneous stimuli). For example, if person's goal is to attend and learn from a college lecture, then they must exhibit inhibitory control to consistently filter out irrelevant information through prepotent response inhibition (e.g., refraining from reflexively turning your head when you hear someone drop their water bottle behind you) as well as distractor interference control (e.g., maintaining attention on the lecture, rather than thinking about what you are doing this weekend).

Findings regarding prepotent response inhibition and distractor interference in autistic populations have been mixed. Meta-analytic results suggest differences in inhibiting prepotent responses (g = 0.55) and ignoring distracting information (g = 0.31) across autistic and neurotypical youth.67 Differences in the inhibition of prepotent behaviors appear to lead to differences in strategically delaying response onset during conditions of uncertainty. More specifically, during stop signal tests in which people must execute a simple behavioral response (e.g., saccadic eye movement) during “go” trials and to inhibit these responses on unexpected “stop” trials, autistic people show differences in strategically delaying behavioral responding, and the ability to delay response onset is predictive of inhibitory control.68,69 These findings suggest that some autistic adolescents may have support needs related to selectively ignoring task-irrelevant information. A lack of effective supports for inhibitory control is associated with variability in academic achievement,70 social competence,71 and healthy eating behaviors,72 suggesting that targeting supports for inhibitory control processes may have wide ranging impacts on outcomes for autistic youth. Understanding inhibitory control strengths and growth areas could inform planning for different supports that facilitate delays in responding or enhance attention and focus.

Conceptual Integration of Research on Self-Determination and Executive Processes: Implications for Personalization of Assessment and Intervention

As the previous sections highlight, there is considerable overlap in research on self-determination, defined by Causal Agency Theory, and executive processes research in autism. In Figure 1, we conceptually align self-determination abilities as defined in Causal Agency Theory (i.e., volitional action, agentic action, and action-control beliefs) with key executive processes (i.e., cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control). We use examples to emphasize ways that a greater focus on understanding support needs of autistic adolescents and young adults related to inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility could support personalization of interventions to build self-determination abilities. We posit that by targeting overlapping processes, we can better integrate research and practice to enhance outcomes.

We hypothesize that quantitative measures of executive processes can be used to determine specific patterns of support needs and enable exploration of their relationships with self-determination abilities and allow for personalized supports for autistic youth in self-determination interventions. For example, some autistic people describe strengths in focus, attention to detail, memory, and creativity but greater difficulty in organizing complex information or adjusting to new environmental contingencies.73–75 Autistic people highlight that their strengths are best leveraged within environments where they can engage in interests.73 For example, an autistic youth or young adult can act volitionally by making decisions about goals given their preferences and values (e.g., interest in computers games; Fig. 1). Supports can be integrated into interventions targeting goal setting and attainment that build cognitive flexibility, if this is an area of need, by leveraging the interest in computers to consider new options for building social relationships (e.g., playing computer games with peers online or in person), if this is aligned with the goals of the autistic adolescent.

Understanding the relationships between self-determination and executive processes can advance a strengths-based approach that focuses on maximizing strengths, recognizing neurodiversity, and addressing support needs related to executive process to build self-determination. As another example, if an autistic person identifies that they struggle with initiating tasks related to their work goals (i.e., agentic action) and assessment information suggests a need for supports for inhibitory control, various personalized support options could be identified in partnership, such as using reminders on one's mobile phone. The autistic person is then empowered to choose the preferred support and continue making progress toward their goal and align their abilities with their environmental supports. However, for another autistic adolescent, a different support might be preferred, such as using a timer or checklist, but this can achieve the same outcome (i.e., self-initiating work tasks), reflecting how personalized supports can be leveraged. This approach differs significantly from deficit-based approaches, which typically focus on identifying where executive processes are not being effectively utilized and attempting to change performance in those environments (e.g., using preferred interests as motivators for task initiation, or focusing on emotional control in all decisions, rather than the decisions of greatest importance to the person). As such, considering how to support growth in self-determination will be most effective if variability in executive processes, particularly cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control, is tracked and then addressed at the individual level through assessment and intervention as highlighted in Figure 1.

Using quantitative measures of executive processes to inform self-determination intervention would allow for a more holistic picture of factors that influence self-determination outcomes, guided by the voices and values of the autistic community. It is important to note that the intent of such an approach would be to determine how to personalize interventions and leverage the most impactful factors to target (or not target, if they are not deemed important or necessary). Diversity in executive processes in autistic people (or in any person) should not limit opportunities and supports provided to exercise self-determination. Instead, an understanding of diversity in executive processes should be used to identify the types of supports that will be most useful to enhance self-determination outcomes. This conceptual alignment demonstrates a potential link between goal-directed abilities and skills associated with self-determination and underlying executive processes in autistic youth, as well as the importance of contextual supports to build on individual strengths and interests as summarized in the examples in Figure 1.

Future Research Directions

As highlighted in the previous section, conceptually integrating research on executive processes and self-determination allows for novel approaches that can inform greater personalization of self-determination interventions in autistic people across the life course. Our synthesis of the literature and novel conceptual integration provides a theoretical framework, but more research is needed to evaluate effective approaches. By enabling autistic adolescents and young adults to identify strengths and areas of need, through access to objective and subjective measures of executive processes and self-determination, we can potentially predict variability in outcomes. We can also begin to identify more personalized interventions and supports that are aligned with the strengths and areas of need, consistent with a strengths-based social-ecological approach to disability.76

For example, the SDLMI (Fig. 2) has been identified as a research-based approach to enhance self-determination outcomes for young people with varying disabilities and support needs.32 However, supports for specific executive processes have never been integrated into the delivery of the SDLMI. Our conceptual integration of research on self-determination and executive processes provides directions for such work. Figure 2 provides an overview of the SDLMI. We have highlighted in the boxes below each phase how self-determined actions and executive processes could be aligned and supported during each phase of SDLMI instruction. For example, cognitive flexibility will be critical to the process of setting a goal, particularly as a young person evaluates different types of goals and has to make decisions about what to focus on. To actualize this integration, research in full partnership with the autistic community is needed to develop these supports.

We are currently engaged in a line of work, in partnership with autistic advocates, to take steps to develop a modified version of the SDLMI that addresses the needs of autistic adolescents and young adults by integrating evidence-based practices and supports in autism, focusing on cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control. This work adopts a community-based participatory research (CBPR) model,77 which involves equitable research partnerships between researchers and community members, including autistic advocates. The rationale for a CBPR is abundant as it enables researchers to explore topics important to self-advocates and generate increased feelings of respect and trust, promoting research participation and more representative knowledge.78 For example, an autistic researcher and advocate have facilitated focus groups with autistic young adults to identify values of the autistic community that must be a part of self-determination instruction and meaningful ways to integrate supports for executive processes into existing SDLMI materials.

As an example of an initial outcome of this work, we have begun highlighting the importance of recognizing and honoring neurodiversity in SDLMI training and implementation materials. As an autistic advocate described during a focus group feedback session, “autism is a natural part of the human diversity that does not need to be fixed or just taken from a person or cured in any way but supported alongside the whole human being” (Shogren et al., unpublished data, 2020). We are also developing resources to embed specific instructions for facilitators to support inhibitory control by providing options for engagement during group activities (e.g., utilizing web-based tools for adolescents to share responses, such as Google Docs or Padlet, or low-tech tools such as poster paper to display information) as well as supports for communication preferences (e.g., colored cards for autistic adolescents to feel empowered in deciding how they want to interact during a SDLMI session) (Shogren et al., unpublished data, 2020). Related to supports for decision-making and cognitive flexibility, we are working with autistic advocates to generate a guide for SDLMI facilitators. The guide provides supports in the form of transition-age examples of how adolescents can learn from and integrate feedback from the various environments they will navigate during the transition-to-adulthood period (e.g., postsecondary education, employment, community, social relationships) and then adapt responses to changing contextual demands (Shogren et al., unpublished data, 2020). In addition to these examples, this guide includes specific strategies for how facilitators can engage autistic adolescents in reflecting on their decision-making processes, including learning from a community of their peers. We are also using objective measures of executive processes alongside self-report measures (i.e., SDI) to personalize and track intervention outcomes. We will test if using self-report measures of self-determination alongside objective measures of executive processes can provide complementary information to guide SDLMI intervention implementation and personalization as well as track and identify factors that influence outcomes.

Embedding these processes more explicitly in Causal Agency Theory and interventions such as the SDLMI advances the belief that autistic people are active contributors to, or agents of, their behavior and have the right to be supported in ways that maximize their self-determination. Continuing to examine how supports related to executive processes enhance the development of self-determination and enable autistic adolescents to meet basic psychological needs for autonomy, competency, and relatedness will further theoretical understandings of the relations across these constructs. Relatedly, the connection between self-determination and executive processes will enhance understandings of how to design autonomy-supportive environments across the life course (e.g., school, work, community) so they include supports for executive processes for autistic people. Furthermore, this connection may lead to the development of universal supports that benefit people across environments. We would note that these issues are not unique to the autistic community. This work builds on collaborations with self-advocates with intellectual disability and their supporters. Ongoing work is needed that is driven by researchers, autistic advocates, as well as other self-advocates and supporters to refine understandings of how executive processes relate to self-determination outcomes and how to assess and track these component processes most effectively for all people. This work may assist in determining profiles of strengths and areas for growth, as well as directly engage young people in identifying how to communicate about and plan for areas of strength and support needs during self-determination interventions. The goal of such personalization is to individualized approaches that improve self-determination outcomes and adult outcomes.

In summary, we recommend the following directions for future research and practice:

-

1.

Engage autistic adolescents and young adults in research on how to leverage strengths and areas of needs related to assessing executive processes to advance self-determined goal-directed actions and use knowledge gained to advance decision-making about supports for assessment and intervention.

-

2.

Integrate objective measures of executive processes with subjective measures of self-determination to understand how objective indicators and subjective perceptions change, or do not change, together with interventions and supports.

-

3.

Enhance self-determination interventions, including facilitator training protocols such as those associated with the SDLMI, to explicitly target a range of executive processes, particularly cognitive flexibility and inhibitory control, guided by the values and needs of the autistic community.

-

4.

Recognize the unique issues encountered by all adolescents, including autistic adolescents, and consider how the increased risk taking and impulsivity that may manifest during the transition to adulthood period can be reframed as opportunities to learn and build more lifelong supports for self-determination that will generalize to early adulthood environments, consistent with Causal Agency Theory.

-

5.

Increase understanding of systemic factors (e.g., access to personalized supports, interventions, opportunities) that can be changed to maximize outcomes for autistic adolescents and young adults, with a focus on a strength-based perspective.

-

6.

Recognize and honor neurodiversity in all assessment and intervention design and implementation, as well as in all research activities.

Conclusions

Transition into adulthood presents challenges for all youth. For autistic adolescents and young adults uncertainty about the future, changes in social relationships and demands, and leaving a relatively structured k-12 environment for a less structured adult world can introduce specific support needs that understanding executive processes can help identify. We highlight an innovative conceptual model integrating research on self-determination and executive processes that is focused on empowering autistic adolescents to self-determine their lives. Aligning research in these two areas can support enhancements to self-determination interventions that build on strengths and areas of need related to executive processes, guided by the values of the autistic community.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

K.A.S., M.W.M., S.K.R., E.E.D., B.E., B.B., and A.W. conceptualized and wrote this article. J.C.K. provided support in identifying references, reviewing, and editing the article and preparing for submission. All authors have reviewed and approved this article submission. The article has been submitted solely to Autism in Adulthood.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

No funding was received for this article.

References

- 1. Test DW, Mazzotti VL, Mustian AL, Fowler CH, Kortering L, Kohler P. Evidence-based secondary transition predictors for improving postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Dev Except Individ. 2009;32(3):160–181. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shogren KA, Wehmeyer ML, Palmer SB, Rifenbark GG, Little TD. Relationships between self-determination and postschool outcomes for youth with disabilities. J Spec Educ. 2015;48(4):30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shogren KA, Abery B, Antosh A, et al. Recommendations of the self-determination and self-advocacy strand from the National Goals 2015 conference. Inclusion. 2015;3(4):205–210. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward MJ. Coming of age in the age of self-determination: A historical and personal perspective. In: Sands DJ, Wehmeyer ML, eds. Self-Determination Across the Life Span: Independence and Choice for People with Disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1996; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ward MJ. An historical perspective of self-determination in special education: Accomplishments and challenges. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabl. 2005;30(3):108–112. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Algozzine B, Browder D, Karvonen M, Test DW, Wood WM. Effects of interventions to promote self-determination for individuals with disabilities. Rev Educ Res. 2001;71(2):219–277. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke KM, Raley SK, Shogren KA, et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to promote self-determination for students with disabilities. Remedial Spec Educ. 2020;41(3):176–188. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wehmeyer ML, Abery B, Mithaug DE, Stancliffe R. Theory in Self-Determination: Foundations for Educational Practice. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publishing Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roux AM, Rast JE, Nye-Lengerman K, Purtle J, Lello A, Shattuck PT. Identifying patterns of state vocational rehabilitation performance in serving transition-age youth on the autism spectrum. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(2):101–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Autistic Self-Advocacy Network. Changing how people think about autism. https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/position-statements/ (accessed July 27, 2021).

- 11. Autistic Self-Advocacy Network. About autism. https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/about-autism/ (accessed July 27, 2021).

- 12. Luna B, Garver KE, Urban TA, Lazar NA, Sweeney JA. Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Dev. 2004;75(5):1357–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larsen B, Luna B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;94:179–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charlton JI. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. Vol 1. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perske R. The dignity of risk. Ment Retard. 1971;10:24–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDonald KE, Keys CB. How the powerful decide: Access to research participation by those at the margins. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;42(1–2):79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDonald KE, Kidney CA. What is right? Ethics in intellectual disabilities research. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil. 2012;9(1):27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sosnowy C, Silverman C, Shattuck P. Parents' and young adults' perspectives on transition outcomes for young adults with autism. Autism. 2018;22(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shogren KA, Broussard R. Exploring the perceptions of self-determination of individuals with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2011;49(2):86–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson KA, Sosnowy C, Kuo AA, Shattuck PT. Transition of individuals with autism to adulthood: A review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics. 2018;141(Supplement 4):S318–S327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim SY. The experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder: Self-determination and quality of life. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;60:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hume K, Dykstra Steinbrenner J, Sideris J, Smith L, Kucharczyk S, Szidon K. Multi-informant assessment of transition-related skills and skill importance in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2018;22(1):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shogren KA, Wehmeyer ML, Palmer SB, Forber-Pratt AJ, Little TJ, Lopez S. Causal agency theory: Reconceptualizing a functional model of self-determination. Educ Train Autism Dev Disabil. 2015;50(3):251. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shogren KA, Ward MJ. Promoting and enhancing self-determination to improve the post-school outcomes of people with disabilities. J Vocat Rehabil. 2018;48(2):187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shogren KA, Wehmeyer ML, Palmer SB. Causal agency theory. In: Wehmeyer ML, Shogren KA, Little TD, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook on the Development of Self-Determination. New York: Springer; 2017;55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Little TD, Hawley PH, Henrich CC, Marsland KW. Three views of the agentic self: A developmental synthesis. In: Deci EL, Ryan RM, eds. Handbook of Self-Determination Research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2002;389–404. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deci EL, Ryan RM, eds. Handbook of Self-Determination Research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 2002; No. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shogren KA, Wehmeyer ML. Self-Determination Inventory. Lawrence, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shogren KA, Burke KM, Antosh AA, et al. Impact of the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction on self-determination and goal attainment in adolescents with intellectual disability. J Disabil Policy Stud. 2018;30:22–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shogren KA, Hicks TA, Raley SK, Pace JR, Rifenbark GG, Lane KL. Student and teacher perceptions of goal attainment during intervention with the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction. J Spec Educ. 2020;55:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shogren KA, Raley SK, Burke KM, Wehmeyer ML. The Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction: Teacher's Guide. Lawrence, KS: Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hagiwara M, Shogren K, Leko M. Reviewing research on the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction: Mapping the terrain and charting a course to promote adoption and use. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2017;1:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burke KM, Shogren KA, Antosh AA, LaPlante T, Masterson L. Implementing the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction with students with significant support needs: A guide to practice. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2020;43(2):115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raley SK, Shogren KA, McDonald A. How to implement the Self-Determined Learning Model of Instruction in inclusive general education classrooms. Teach Except Child. 2018;51(1):62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Demetriou E, Lampit A, Quintana D, et al. Autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of executive function. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(5):1198–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kenworthy LY, Anthony BE, Gutermuth L, Wallace GL. Understanding executive control in autism spectrum disorders in the lab and in the real world. Nueropsychol Rev. 2008;18(4):320–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nigg JT, Gustafsson HC, Karalunas SL, et al. Working memory and vigilance as multivariate endophenotypes related to common genetic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(3):165–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zelazo PD. Executive function: Reflection, iterative reprocessing, complexity, and the developing brain. Dev Rev. 2015;38:55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, Nieuwenhuis S. The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2004;306(5695):443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pugliese CE, Anthony LG, Strang JF, et al. Longitudinal examination of adaptive behavior in autism spectrum disorders: Influence of executive function. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(2):467–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zimmerman D, Ownsworth T, O'Donovan A, Roberts J, Gullo MJ. Associations between executive functions and mental health outcomes for adults with autism spectrum disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:360–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nadig A, Flanagan T, White K, Bhatnagar S. Results of a RCT on a transition support program for adults with ASD: Effects on self-determination and quality of life. Autism Res. 2018;11(12):1712–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oswald TM, Winder-Patel B, Ruder S, Xing G, Stahmer A, Solomon M. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the ACCESS Program: A group intervention to improve social, adaptive functioning, stress coping, and self-determination outcomes in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(5):1742–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Odom SL, Boyd B, Hall LJ, Hume K. Evaluation of comprehensive treatment models for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:425–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Robertson SM. Neurodiversity, quality of life, and autistic adults: Shifting research and professional focuses onto real-life challenges. Disabil Stud Q. 2009;30(1). [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ne'eman A. The future (and the past) of Autism advocacy, or why the ASA's magazine, The Advocate, wouldn't publish this piece. Disabil Stud Q. 2010;30(1). [Google Scholar]

- 47. De Martino B, Harrison NA, Knafo S, Bird G, Dolan RJ. Explaining enhanced logical consistency during decision making in autism. J Neurosci. 2008;28(42):10746–10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. South M, Chamberlain PD, Wigham S, et al. Enhanced decision making and risk avoidance in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Neuropsychology. 2014;28(2):222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lai CLE, Lau Z, Lui SSY, et al. Meta-analysis of neuropsychological measures of executive functioning in children and adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2017;10(5):911–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Leung RC, Zakzanis KK. Brief report: Cognitive flexibility in autism spectrum disorders: A quantitative review. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2628–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Crawley D, Zhang L, Jones EJH, et al. Modeling flexible behavior in childhood to adulthood shows age-dependent learning mechanisms and less optimal learning in autism in each age group. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(10):e3000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ragozzino ME. The contribution of the medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsomedial striatum to behavioral flexibility. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1121(1):355–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dajani DR, Uddin LQ. Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38(9):571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hus V, Pickles A, Cook Jr EH, Risi S, Lord C. Using the autism diagnostic interview—revised to increase phenotypic homogeneity in genetic studies of autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(4):438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lam KS, Bodfish JW, Piven J. Evidence for three subtypes of repetitive behavior in autism that differ in familiality and association with other symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(11):1193–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lecavalier L, Bodfish J, Harrop C, et al. Development of the behavioral inflexibility scale for children with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Autism Res. 2020;13(3):489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Miller M, Chukoskie L, Zinni M, Townsend J, Trauner D. Dyspraxia, motor function and visual–motor integration in autism. Behav Brain Res. 2014;269:95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Iversen RK, Lewis C.. Executive function skills are linked to restricted and repetitive behaviors: Three correlational meta analyses. Autism Res. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sethi C, Harrop C, Zhang W, Pritchett J, Whitten A, Boyd BA. Parent and professional perspectives on behavioral inflexibility in autism spectrum disorders: A qualitative study. Autism. 2019;23(5):1236–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Miller HL, Ragozzino ME, Cook EH, Sweeney JA, Mosconi MW. Cognitive set shifting deficits and their relationship to repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45(3):805–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Frye D, Zelazo PD, Palfai T. Theory of mind and rule-based reasoning. Cogn Dev. 1995;10(4):483–527. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sachse M, Schlitt S, Hainz D, et al. Executive and visuo-motor function in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(5):1222–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ozonoff S, Cook I, Coon H, et al. Performance on Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery subtests sensitive to frontal lobe function in people with autistic disorder: Evidence from the Collaborative Programs of Excellence in Autism network. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34(2):139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. D'Cruz A-M, Ragozzino ME, Mosconi MW, Shrestha S, Cook EH, Sweeney JA. Reduced behavioral flexibility in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychology. 2013;27:152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schmitt LM, Ankeny LD, Sweeney JA, Mosconi MW. Inhibitory control processes and the strategies that support them during hand and eye movements. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Geurts HM, van den Bergh SF, Ruzzano L. Prepotent response inhibition and interference control in autism spectrum disorders: Two meta-analyses. Autism Res. 2014;74(4):407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kelly E, Meng F, Fujita H, et al. Regulation of autism-relevant behaviors by cerebellar–prefrontal cortical circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(9):1102–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schmitt LM, White SP, Cook EH, Sweeney JA, Mosconi MW. Cognitive mechanisms of inhibitory control deficits in autism spectrum disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(5):586–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA. Relations among peer acceptance, inhibitory control, and math achievement in early adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2013;34(1):45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ciairano S, Visu-Petra L, Settanni M. Executive inhibitory control and cooperative behavior during early school years: A follow-up study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(3):335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lavagnino L, Arnone D, Cao B, Soares JC, Selvaraj S. Inhibitory control in obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:714–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Russell G, Kapp SK, Elliott D, Elphick C, Gwernan-Jones R, Owens C. Mapping the autistic advantage from the accounts of adults diagnosed with autism: A qualitative study. Autism Adulthood. 2019;1(2):124–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cannon H. Autism: The Positives. Leeds: University of Leeds; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wolman D. The advantages of autism. New Sci. 2010;2758(5):32–35. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Shogren KA. A social-ecological analysis of the self-determination literature. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51:496–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McDonald KE, Stack E. You say you want a revolution: An empirical study of community-based participatory research with people with developmental disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(2):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McDonald KE, Raymaker DM. Paradigm shifts in disability and health: Toward more ethical public health research. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2165–2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Faja S, Murias M, Beauchaine TP, Dawson G. Reward-based decision making and electrodermal responding by young children with autism spectrum disorders during a gambling task. Autism Res. 2013;6(6):494–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kenworthy L, Anthony LG, Naiman DQ, et al. Randomized controlled effectiveness trial of executive function intervention for children on the autism spectrum. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(4):374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]