Abstract

Background:

Compared with adults in the general population, autistic adults are more likely to experience poor mental health, which can contribute to increased suicidality. While the autistic community has long identified autistic burnout as a significant mental health risk, to date, only one study has been published. Early research has highlighted the harmful impact of autistic burnout among autistic adults and the urgent need to better understand this phenomenon.

Methods:

To understand the lived experiences of autistic adults, we used data scraping to extract public posts about autistic burnout from 2 online platforms shared between 2005 and 2019, which yielded 1127 posts. Using reflexive thematic analysis and an inductive “bottom-up” approach, we sought to understand the etiology, symptoms, and impact of autistic burnout, as well as prevention and recovery strategies. Two autistic researchers with self-reported experience of autistic burnout reviewed the themes and provided insight and feedback.

Results:

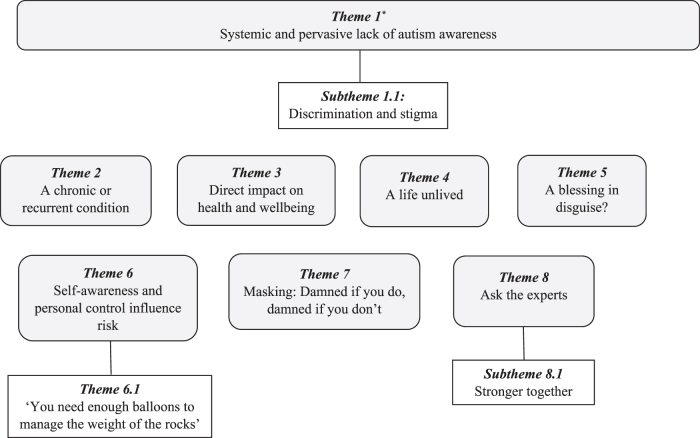

We identified eight primary themes and three subthemes across the data. (1) Systemic, pervasive lack of autism awareness. (1.1) Discrimination and stigma. (2) A chronic or recurrent condition. (3) Direct impact on health and well-being. (4) A life unlived. (5) A blessing in disguise? (6) Self-awareness and personal control influence risk. (6.1) “You need enough balloons to manage the weight of the rocks.” (7) Masking: Damned if you do, damned if you don't. (8) Ask the experts. (8.1) Stronger together. The overarching theme was that a pervasive lack of awareness and stigma about autism underlie autistic burnout.

Conclusions:

We identified a set of distinct yet interrelated factors that characterize autistic burnout as a recurring condition that can, directly and indirectly, impact autistic people's functioning, mental health, quality of life, and well-being. The findings suggest that increased awareness and acceptance of autism could be key to burnout prevention and recovery.

Keywords: autism, autistic burnout, exhaustion, burnout, autistic adults, thematic analysis

Community brief

What was the purpose of this study?

Although the autistic community has talked about autistic burnout for a long time, there has not been much research about the topic. This study aimed to investigate autistic burnout from the perspective of autistic adults to understand what they think causes it, the symptoms and impact on their lives, and what can be done to assist prevention and recovery.

Why is this an important issue?

This issue is important because autistic people have said that autistic burnout can severely affect their quality of life and well-being and contribute to poor mental health, including the risk of suicide.

What did the researchers do?

We used a computer program to collect public posts from two online platforms to look at how autistic adults described autistic burnout. We collected 1127 posts shared over a 12-year period by 683 users. To understand the adults' lived experiences, we analyzed their language at the surface level and looked for common themes across the data.

What were the results of the study?

The adults in this study said that autistic burnout was often first experienced during adolescence, lasted months or years, and was hard to recover from. They described severe direct and indirect consequences for their physical and mental health, capacity to function, and ability to achieve personal goals. They described a general lack of knowledge about autism, especially among health care professionals, which led to misdiagnosis and inadequate or inappropriate treatment. Masking or “camouflaging” to pass as nonautistic was the most common reason participants gave for autistic burnout. Many used strategies to manage energy levels to avoid burnout. The autistic community was an essential source of information and support for participants. Overall, stigma, discrimination, and low awareness and acceptance of autism were responsible for the cycle of autistic burnout.

How do these findings add to what was already known?

As one of the first studies about autistic burnout, we learned that it happens because of factors associated with being autistic and poor autism awareness and acceptance within society. We now know that autistic people often first experience autistic burnout when they are young, but it usually recurs, which can stop autistic people leading fulfilling lives. We learned that difficulty identifying emotions may be a risk factor and that online communication may help autistic people during recovery. We found that some positive consequences of autistic burnout include autism diagnosis in adulthood, finding the autistic community, and making empowering lifestyle changes.

What are the potential weaknesses in the study?

We had limited demographic information, so we do not know how diverse the sample was or how factors such as gender, age, race, or identifying as LGBTQI may have influenced some people's experience of autistic burnout. The adults in this study had access to online platforms and could communicate in writing, and so, people with higher communication support needs may not have been included.

How will these recommendations help autistic adults now or in the future?

The findings reinforce the personal stories of autistic people and show that autistic burnout is a common, consistent, and harmful experience. The findings show it is vital for health professionals to recognize autistic burnout to provide appropriate care and support because prevention and early detection could help stop the harmful cycle of autistic burnout. The findings underscore the importance of reducing discrimination and stigma against autistic people and increased acceptance.

Introduction

Myriad first-person accounts by members of the autistic community indicate the debilitating impact of “autistic burnout” on their mental health and well-being, with one person describing it as: “an integral part of the life of an autistic person that affects us pretty much from the moment we're born to the day we die, yet nobody, apart from autistic people really seem to know about it.”1 The term “burnout” originated within organizational psychology to describe the state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion that develops over time from job-related stress.2 Some researchers posit that this exhaustion is associated with a specific aspect of an individual's life,3 which can be nonwork related, such as a lack of recovery in athletes4 and perfectionism in parents.5 It is, therefore, possible that factors related to autism (e.g., sensory hypersensitivity) may uniquely contribute to autistic burnout.

Until recently, studies about autism-related burnout focused on the experiences of parents, teachers, and peers of autistic children.6–8 The first study of burnout from the perspective of autistic adults recently defined autistic burnout as a syndrome “resulting from chronic life stress and a mismatch of expectations and abilities without adequate supports […] characterised by pervasive, long-term (typically 3+ months) exhaustion, loss of function, and reduced tolerance to stimulus.”9(p9) Life stressors (e.g., masking of autistic traits; significant life changes) and barriers to support (e.g., poor self-advocacy; an imbalance between demands and coping resources) contributed to the onset of autistic burnout, with the authors concluding that burnout has severe consequences for the mental health and quality of life of autistic adults.9

Compared with adults in the general population, autistic adults are more likely to experience poor mental health,10,11 which can contribute to a greater risk for suicidal ideation, self-harm, and death by suicide.12–14 Growing evidence suggests that the use of “camouflaging” or “masking” to hide autistic traits is strongly associated with poor mental health and suicidality in autistic adults.12,15,16 Autistic adults report that masking to “pass” as nonautistic is exhausting over time, but is used to avoid consequences of stigma and discrimination, including bullying and loss of opportunities.15,17 Masking can contribute to missed and delayed diagnosis, and qualitative studies show that prior awareness of being different without knowing why18,19 and the lack of appropriate support after late diagnosis can contribute to poor mental health in autistic adults.12,20 Masking has been identified as a prominent risk factor for autistic burnout and may represent a novel perspective for understanding suicidality among autistic adults9; therefore, this association warrants further investigation.

Poor awareness about the wide-ranging differences among, and within, autistic individuals can add to autistic people's mental health burden through unreasonable expectations. For example, the support needs of an autistic person with uneven cognitive strengths (“spiky profile”), such as above average verbal skills but poor working memory, may go unrecognized at work.21 Health care professionals are not adequately trained in recognizing autism in adulthood (especially in females), leading to missed or misdiagnosis and lost opportunities for support.20,22 It is now widely accepted that autism diagnostic criteria and the gold-standard diagnostic tools have been informed by research about male autistic children, and are thus skewed toward the stereotypical male presentation. Therefore, these tests are not sensitive enough to detect the unique and subtle ways that autism manifests in females, or adults in general.23–27 In addition, health care providers have acknowledged the need to enhance their confidence in communicating with, and accommodating the needs of, autistic clients to improve patient care.28

Autistic people face stigma and discrimination, which can harm their mental health and well-being29 and deter them from disclosing their diagnosis, limiting their access to accommodations.30 Cage et al.31 reported that increased autism acceptance predicted lower symptoms of depression in autistic adults. Feeling supported and accepted may also protect against autistic burnout, as well as reduced expectations, time off, unmasking, and the ability to do things in an autistic way.9 Learning more about risk and protective factors for autistic burnout is vital to help reduce vulnerability to its onset.

The current study* aimed to examine the construct of autistic burnout by examining posts about the topic on two social media platforms. Our objectives were to investigate the etiology and symptoms of autistic burnout, its impact on the lives of autistic adults, and potential strategies for prevention and recovery.

Methods

Data sources

We collected public retroactive posts from the social media platform, Twitter, and discussion forum, Wrong Planet. We sought insight into autistic adults' real-world experiences and discourse about autistic burnout without researcher prompting or interference. The sites were chosen for their different participation styles and potential to reach a broader range of autistic adults. While Twitter enables instant communication between individuals and organizations globally, Wrong Planet was created for the autistic community. Twitter users share short messages (“tweets”) and use hashtags (#) to find tweets about a trend or topic (e.g., #AutisticBurnout) or connect with a community (e.g., #ActuallyAutistic). Alternatively, Wrong Planet facilitates richer descriptions about experiences and discussions among members because post length is not limited. Neither platform required membership to read public posts.

Participants

The study included adults (older than 18 years) who had shared a post to Twitter or Wrong Planet between January 2005 and November 2019 containing various search terms related to burnout (see the Procedure section). While we could not confirm that all individuals met the age requirement, posts were excluded if the user's profile or post content indicated they were younger than 18 years (e.g., explicit reference to their age or school year-level).

The total sample comprised 683 individuals: 559 Twitter users and 124 users from Wrong Planet. Of these, 612 users were self-identified autistic adults, and 71 users (n = 69 from Twitter and n = 2 from Wrong Planet) were nonautistic researchers, disability advocates, parents, or friends of autistic people whose posts were included because they addressed the research objectives. We assumed autistic status if the users referred to themselves as autistic or used the #ActuallyAutistic hashtag. Demographic information for the Wrong Planet users is presented in Table 1. Of the 124 forum users, 80 shared their age, which ranged between 21 and 76 years (M = 41.4 years). Most users disclosed their gender, with an almost equal number of males and females. Privacy regulations prevented us from collecting demographic data about the Twitter users.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Wrong Planet Users

| % | n | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (N = 124) | ||

| Male | 48.4 | 60 |

| Female | 49.2 | 61 |

| Not provided | 2.4 | 3 |

| Age (N = 80) | ||

| 18–24 | 6.25 | 5 |

| 25–34 | 28.75 | 23 |

| 35–49 | 38.75 | 31 |

| 50–76 | 26.25 | 21 |

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC20389). An owner of Wrong Planet approved the collection and use of forum data. The first author sought permission from 35 users to quote excerpts from their posts by sending them a direct message briefly describing the study and asking them to reply for further information. Eight participants responded and were sent a participant information and consent form, which they signed and returned. Where the users did not respond, or their post/account had been deleted since data collection, excerpts were included only if their identity could not be traced via an internet search.

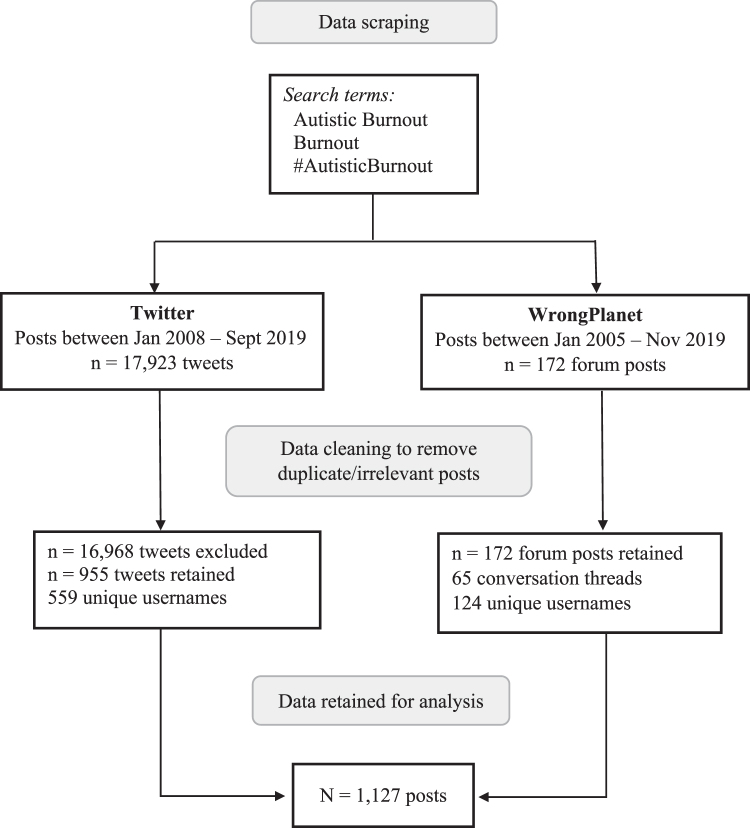

The third author (A.A.) used a computer algorithm to extract the posts (“data scraping”), which were saved in an Excel file. Details regarding the search parameters and data collected from each platform are shown in Figure 1. Twitter users can like, share (“retweet”), and reply to posts, which indicate how strongly a tweet or topic resonates with others. The retained tweets recorded a total of 10,012 likes, 2669 retweets, and 1694 replies.

FIG. 1.

Data collection and refinement process.

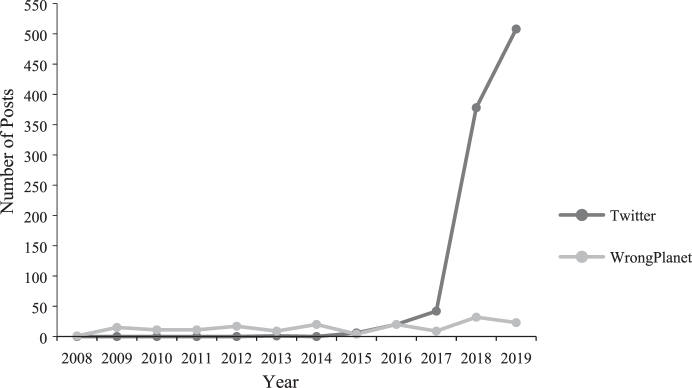

Figure 2 shows the yearly number of posts containing one or more of the data search criteria per platform, starting from the year a term was first located in the data set. An exponential yearly increase in the number of tweets about autistic burnout is observable, with a noticeable spike in 2018. There were fewer mentions of burnout on Wrong Planet, which remained relatively steady, year-on-year. Twitter users regularly used the platform to seek advice and share information and resources about the topic, including links to blogs, videos, and activist campaigns. The forum users shared resources less frequently but engaged in more in-depth discussions about autistic burnout.

FIG. 2.

Yearly posts* about autistic burnout for each online platform. Number of yearly posts containing one or more of the search criteria, from when a term was first mentioned in the data set. *n = 955 Twitter posts; n = 172 Wrong Planet posts.

Data analysis

The first author conducted reflexive thematic analysis and used a critical-realist framework to identify and understand patterns of meaning across the data.32 This approach acknowledges the influence of social and cultural contexts on reality, and that insight can be gained by interpreting the language individuals use to describe their lived experiences.33 The research methodology was informed by the perspective that autistic people are best placed to describe their own experiences of autism and autistic burnout. J.M. generated the codes and themes inductively, or “bottom-up” from the data, rather than using predetermined ideas or theories.34 The motivation for this research came from J.M.'s personal involvement with the autistic community, including informal discussions with people who have experienced autistic burnout. J.M. read the data through the lens of neurodiversity, which views autism as a normal form of human variation with inherent strengths, rather than a condition to be cured.35 Throughout, J.M. reflected on how her pre-existing knowledge about autistic burnout and experiences as a nonautistic parent of young autistic children influenced her reaction to, and interpretation of, the data.

Data analysis followed the six-phase process described by Braun and Clarke.36

-

1.

Data familiarization

-

2.

Generating codes

-

3.

Developing themes

-

4.

Reviewing themes

-

5.

Defining themes

-

6.

Report writing

First, J.M. read each post multiple times and recorded informal reflections and ideas in a journal. Second, excerpts from the data relevant to the research question were selected and organized into common groups (“codes”) using QSR NVivo (Version 12). This was done using a “complete coding” approach where each post was given equal consideration; some posts were assigned to numerous codes, and others were not coded at all.37 Consistent with a realist framework, J.M. used semantic coding to capture a descriptive narrative of people's experiences by interpreting people's language at face-value, rather than searching for implicit meanings.34 A total of 336 unique codes were generated and reviewed, and overlapping codes were merged. Codes containing fewer than 10 excerpts and those not directly relevant to the research question were excluded, which left 99 codes for further analysis. A quantitative measure of coding inter-rater reliability is not appropriate for reflexive thematic analysis because coding is a subjective process, inextricably influenced by individual researchers' theoretical perspectives and personal experiences.34,37

During the third phase, J.M. grouped codes according to patterns identified within the data and generated a list of candidate themes that captured shared meanings. A series of thematic maps were drawn to visually explore and refine the relationships between the provisional themes. To ensure interpretative depth and robustness, J.M. discussed the candidate themes with A.L.R. and C.D. who contributed their ideas and feedback. The large sample size was considered sufficient to achieve theme saturation given the data were “shallow” and comprised short descriptions about lived experiences.37

Fourth, J.M. read the posts again to ensure that the themes captured the essence of the data and worked together to build a cohesive and meaningful narrative. During the fifth phase, J.M. defined each theme and subtheme, specifying their scope and unique characteristics, and chose supporting extracts from the data. Other members of the research team (A.L.R., C.D., J.L.), and an autistic colleague, reviewed the themes and subthemes to ensure readability and provided additional insights. Our team included two autistic adults with self-reported experience of autistic burnout. The sixth phase consisted of writing up the report.37

Results

A thematic map showing the final set of primary themes and subthemes about autistic burnout is presented in Figure 3. Additional quotations to support themes and subthemes are shown in Table 2. Excerpts have been reproduced verbatim; therefore, may contain spelling and grammatical errors.

FIG. 3.

Thematic map of the eight primary themes and three subthemes about autistic burnout. *Theme 1 was both a stand-alone theme and the overarching theme in our study.

Table 2.

Supplementary Quotes to Support the Study Themes and Subthemes

| Theme 1: Systemic and pervasive lack of autism awareness |

| Although I have gone to a therapist, my first one flat out told me she ‘didn't have the ability’ to help me, and after switching to a psychiatrist they treat and worry about my ADHD/Autism while my burnout and depression just drag me further and further down in exhaustion. (T289) |

| People who don't understand Autism are seeing behaviours that they assume are mental health problems. Confusing Burnout for depression, seeing meltdowns & only seeing it as inappropriate negative behaviour, not sensory overwhelm. Using restraints, drugs and ineffective therapy. (T290) |

| Subtheme 1.1: Discrimination and stigma |

| I'm #ActuallyAutistic and I view Autism as a mental health issue, but not a mental illness. Lack of accommodation, stigma, & burnout all affect my MH […] (T260) |

| […] they'll change your schedule suddenly, or ask you to do something you're not comfortable with and when you balk because you're just so stressed out you don't have the flexibility to adapt anymore, you'll get your first warning—then you'll know the end is in sight. […] You have to wait until they fire you for just being you […] (WP115) |

| Theme 2: A chronic or recurrent condition |

| In burnout now and going on Month 15. No end in sight. Experienced it maybe 4 times now. I crashed and burned hard. (T386) |

| A couple of years ago I had a full burnout that could have potentially actually killed me and that left me permanently changed and not for the better. (WP93) |

| Theme 3: Direct impact on health and well-being |

| […] It feels like my thoughts are encased in taffy.[…] (T443) |

| How will she stand? How will she carry on? How can she breathe? The weariness of her spirit can no longer be carried. Her fire has been extinguished. She searches for the peace of nothingness. Its quiet void echoes how she already feels. #AutisticBurnout (T432) |

| Theme 4: A life unlived |

| With an expectation that younger people will work until they are 70 before retiring it's […] important to understand the cumulative effect of repeated burnout on autistic people and develop preventive strategies […] (T75) |

| Theme 5: A blessing in disguise? |

| Burnout […] was huge. 39 months later and my life is very different but much more sustainable. (T476) |

| […] I need to get back into my #actuallyautistic skin and stop letting others separate me from my #autistic self. I died to get here. I must always remember that. (T400) |

| Theme 6: Self-awareness and personal control influence risk |

| […] the only thing that would help me is beyond my control […] I have nowhere to go where I'd avoid being overwhelmed. (WP98) |

| […] I want to do more hours, but I know this will lead to burnout for me […] (T349) |

| Theme 6.1: “You need enough balloons to manage the weight of the rocks” |

| Autism only gives me so much energy to work with and if I overstretch myself, I'll be prone to meltdown and burnout (T427) |

| Hoping to survive today with a lot of self-soothing and self-care […] (T432) |

| Theme 7: Masking: Damned if you do, damned if you don't |

| Masking is a tool that should be used to get things nothing less, nothing more. Like with anything in life overdoing it leads to problems. With masking they can be quite serious burnout, forgetting who you are, constant anxiety from fear of slipping and being exposed. […] (WP9) |

| I get told by everyone that I seem to be managing my autism well […] but the constant masking at work is exhausting and I ended up in burnout this weekend. (T349) |

| Two main problems […] (1) It can lead to a nasty case of burnout. (2) If people don't see the real you they can't love the real you. It alienates you from people; even as it seems your relationships with people are improving, the amount of joy you derive from it decreases. […] (WP108) |

| Theme 8: Ask the experts |

| The autistic community has been saying burnout is a medical problem forever […] (T90) |

| Theme 8.1: Stronger together |

| #AutisticBurnout is being talked about at last. It affects so many of us—who knew? Which is why the conversation matters. Thanks to you I recognised the signs, took care of myself, avoided total crisis (T353) |

Theme 1: systemic and pervasive lack of autism awareness

The lack of awareness about autism was both a stand-alone theme and the underlying factor that connected all themes in the study. Users frequently described a pervasive and systemic lack of knowledge about autism traits and presentation differences that led to negative experiences within health care, education, employment, and family systems. These experiences included missed or late diagnosis of autism, misdiagnosis, unreasonable expectations, insufficient or nonexistent accommodations and supports, and general failure to meet their needs, which increased the burden on individuals and contributed to autistic burnout.

How do I survive autistic burn-out if neither my doctor, nor University, nor psychologist allow me to take the rest I need in order to function? […] (T231)†

Subtheme 1.1: discrimination and stigma

This subtheme captured users' experiences of not being accepted and illustrated how negative stereotypes and stigma surrounding autism contributed to burnout. Many said they tried to “pass” as nonautistic and feared “outing” themselves as autistic because of negative perceptions and stigma about autism. Some had internalized the stigma, which impacted their identity and confidence to self-advocate.

Do I as an #ActuallyAutistic person deserve to not have real-life friends? To be controlled by my family? To fight for accommodations and mental health care? To beg for money? To put education before health? To have a burn-out each year? Is this what I deserve? Survival? (T231)

Users experienced direct and indirect discrimination in the workplace. Some had been dismissed after disclosing their autism diagnosis. In contrast, others perceived that their employers deliberately altered their working conditions to make it harder for them to cope, thus forcing them to resign.

[…] I was dismissed from my last job after I went through autistic burnout and disclosed my autism. They weren't willing to make the necessary accommodations: too burdensome. It's the first time I've ever been fired. (T70)

Theme 2: autistic burnout is a chronic or recurrent condition

Many users discussed the chronic nature of autistic burnout, which many first experienced during childhood or adolescence and which then recurred during adulthood. Burnout was described as an endpoint after a buildup of demands over time that had exceeded their coping abilities. For many, vulnerability to burnout increased at developmental transition stages (e.g., transition to and from high school) and after stressful life events.

My first burnout was in school. The lights, sounds, business of a full 8 hour day was too much. I was physically sick from it. Kids need more down time and the sensory environment needs to be considered […] (T369)

For many of the adults, periods of autistic burnout were long, lasting months or years, and recovery was either protracted or never fully achieved. The users often described a lower threshold for stressors after burnout and that coping resources were depleted more quickly. Many reported that multiple episodes of burnout had a cumulative negative impact on resilience and well-being.

[…] Recovered a bit, but I worry I will never be whole again. It ate part of me. (T355)

Theme 3: direct impact on health and well-being

The overt impact of autistic burnout on the users' mental health and cognitive abilities included widespread descriptions of overwhelming exhaustion and the inability to function. Many experienced a marked reduction in their ability to produce and process speech and heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli. They frequently described a loss of previously acquired skills (including self-care), poorer attention and executive functioning skills, and feeling they had become “more autistic.” Greater difficulty with emotion regulation, including a higher incidence of meltdowns (e.g., excessive crying; becoming aggressive and angry) and shutdowns (e.g., dissociation; becoming withdrawn and unresponsive), before reaching the burnout stage was typical.

I am so low on energy, I can't cope with anything right now. I shut down after only little stimuli…I don't know how to cook, how to clean the house, can't go to the store.[…]I shut down so badly I don't dare to drive anymore (too dangerous). I don't enjoy my special interests anymore, and feel mentally stupid […] (WP59)

Many individuals experienced a decline in their mental health and exacerbated conditions such as anxiety and depression during burnout. Autistic burnout often led to suicidal ideation, especially when it co-occurred with depression. The users described an inability to cope and needing a break from life.

[…] experiencing burnout so severe for so long that you wish you could just not be here anymore. Not really suicidal, just wanting to be finished. (T461)

[…] I was so far into autistic burnout AND a major depressive episode […] I was […] terrified and really, really done with suffering (T61)

Theme 4: a life unlived

This theme captured indirect consequences that the users attributed to autistic burnout. Many individuals indicated that experiencing burnout during adolescence had a ripple effect that altered the trajectory of their lives, limiting education and employment opportunities, which they perceived led to a failure to reach their potential. Autistic burnout also contributed to relationship difficulties, risk of (or actual) institutionalization, and homelessness.

Oh and good luck breaking into a different field if you succumb to autistic burnout. […] goodbye income goodbye lifestyle goodbye independence […] (T280)

Last time I had a major burnout, I ended up first in the mental hospital and then effectively homeless […] (WP26)

Theme 5: a blessing in disguise?

This theme described positive outcomes of the users' autistic burnout experiences. Many individuals reported that burnout was the catalyst for their diagnosis of autism in adulthood, which gave them a new perspective for re-evaluating their lives. Diagnosis often led to improved self-awareness, self-care, self-esteem, and confidence to self-advocate, which had a resultant positive impact on the adults' well-being. Other favorable outcomes included finding the autistic community, connecting with others who shared their lived experiences, and making positive lifestyle and career changes to reduce stress and live more authentically. For many, diagnosis after burnout led to an improved sense of identity and relief at finally understanding why they had felt different throughout their lives.

[…] A massive autistic burnout has probably saved my life […] Trying to […] learn to accept myself better and move on (T12)

At age 37, learning about autism finally gave me the key to understanding my life (T173)

Theme 6: self-awareness and personal control influence risk

This theme explored how self-awareness and control over stressors affected the adults' risk of developing autistic burnout. Throughout, many described a common set of factors that contributed to burnout, including overwhelming sensory and cognitive demands, masking or camouflaging autistic traits, stressful life events, co-occurring conditions, autistic characteristics, and lack of social support. However, their ability to recognize the buildup of pressures and change environmental stressors influenced whether they experienced burnout. For example, adults who recognized sensory overstimulation in the workplace and requested reasonable accommodations (e.g., wearing headphones) could better manage the impact.

[…] I need to respect my own rhythms. If I'm not feeling it then I shouldn't force it. (WP40)

Many users also used self-stimulatory behaviors (“stimming”) and time with special interests to manage sensory and emotion regulation. Stress accumulated when they were prevented from using these strategies, usually because of stigma or fear of standing out, which increased their vulnerability to burnout.

Stimming is the autistic way of dealing with stress. Even a few minutes here and there in the bathroom could be of help. […] (WP9)

Sometimes I think, if I didn't have my interests to keep me going. I would give up and lose control completely (WP41)

During a period of burnout, exhaustion limited the autistic individuals' ability to manage stressors, and social support played an important role in recovery, as illustrated by this participant:

[…], I needed solitude and I needed to remove as much sensory stimuli as possible. It was not possible for me to talk to people or to have them around. The only exception was my brother because […] he spoke to me […] very quietly and calmly and slowly and directly so that I could clearly understand what he was saying and I did not have to spend energy interpreting or trying to understand his words […] (WP93)

Subtheme 6.1: “you need enough balloons to manage the weight of the rocks”

This subtheme described the deliberate use of strategies for managing demands and energy to avoid overload that could lead to autistic burnout over time. Users commonly described the benefits of rest and social and sensory avoidance to offset demands, which helped prevention and recovery.

I was told for years that avoiding things will only make everything worse. And while that is commonly true for my #anxiety it absolutely isn't true for my #autism related problems. Exposure there makes it WORSE because it causes overload, then burnout. Avoidance HELPS this. (T98)

Theme 7: masking: damned if you do, damned if you don't

Masking was a complex and multifaceted theme. Many of the adults identified masking as a leading risk factor for autistic burnout and described it as a “no win” situation. Although masking facilitated access to job opportunities and social inclusion, it was consistently described as exhausting. Long-term masking negatively impacted individuals' mental health and well-being and ultimately led to burnout. For many, masking led to identity confusion and contributed to support needs being unrecognized or disbelieved.

Masking is a skill but can feel like a curse. We need to remind ourselves to unmask, otherwise we risk burning out. And we deserve better. […] (T19)

Many participants described “taking the mask off,” either reluctantly (e.g., unable to keep masking) or by choice (e.g., through self-acceptance). However, unmasking was complex; while it facilitated self-acceptance and reduced cognitive load, the consequences of being openly autistic included ostracism and bullying, which contributed to burnout.

I know that the breakdown and following burnout is because I was simply unable to keep masking my autism, and there's no putting the lid on again (nor would I want to), but it's still a complex set of relations that underpin this change. (T262)

The autistic adults also described the harmful impact of masking on social relationships. After unmasking, some were accused of faking autistic traits, whereas others were criticized for pretending not to be autistic. Some were advised to continue masking.

[…] I have encountered some people who either will not believe my diagnosis or who take the attitude that if I could conceal my traits before, then there is no reason why I shouldn't continue to […] (WP106)

Many users tried to strike a balance between masking, living authentically, exhaustion, and discrimination. They retained masking behaviors to achieve goals, avoid stigma, and attain resources, but dropped the mask with trusted friends and family to try and reduce their risk of autistic burnout.

Theme 8: ask the experts

This theme described the adults' significant insight and knowledge about autistic burnout. They clearly described various characteristics of their burnout experiences, including causes and symptoms, its impact on their lives, and strategies for prevention and recovery. Most decried the lack of knowledge and understanding about autistic burnout outside the autistic community, and many shared links to personal blogs, videos, infographics, and other resources to educate others and bridge the knowledge gap.

Like so much else about autism, I've learnt everything I know about autistic burnout from the insightful descriptions and selfless honesty of autistic people (T191)

Non-autistic Twitter users were encouraged to use the #AskingAutistics hashtag to utilize the expertise of the autistic community to support autistic family members and friends. Some individuals were professional autism advocates, but, ironically, the demands of autism advocacy sometimes contributed to burnout.

Subtheme 8.1: stronger together

This subtheme captured how sharing burnout experiences online fostered empathy, connection, and belonging among the adults. Users across both platforms sought and offered support and advice from fellow members. The Twitter hashtag, #ActuallyAutistic, was widely used to claim an autistic identity, express autistic pride, and bring groups of autistic people together. For many, the compassion and understanding demonstrated by other online users were often an invaluable source of comfort and hope, especially for those who lacked support offline.

As an #ActuallyAutistic woman who did not get diagnosed until age 41… this thread made me cry multiple times because of how SEEN I felt. Particularly the section about Autism Burnout. I lived my whole life that way. I'm so grateful I don't ever have to go through that again […] (T477)

Discussion

We explored the lived experience of autistic burnout in a large cohort of autistic adults to garner a comprehensive understanding of how burnout begins and recurs, and ways to support prevention and recovery. Our findings confirm Raymaker et al.'s9 definition of autistic burnout as a syndrome characterized by long-term exhaustion, reduced ability to function, and increased sensory sensitivity caused by masking and life stressors that negatively impact mental health and quality of life. Their suggested strategies for reducing burnout, including acceptance and peer support, unmasking, social withdrawal, recognizing symptoms of burnout onset, and the benefits of early autism diagnosis were also supported. As our research was conducted independently and commenced before the publication of Raymaker et al.'s9 seminal work, the similarities between findings strengthen and validate our understanding of autistic burnout. Our findings also extend what is currently known.

We found that while autistic burnout is a consequence of chronic life stress,9 it could itself be a chronic condition. Many adults described numerous burnout episodes, with onset usually in adolescence, and a recurring cycle that interfered with personal progress and achievement. The World Health Organization characterizes chronic conditions as persistent and often co-occurring with other health problems caused by multiple, complex, social and economic factors that can impact quality of life and independence, create restrictions and disability, contribute to loss of education and marginalization, and lower life expectancy.38 Some chronic conditions (e.g., insomnia) may manifest as one long episode or as shorter episodes that recur.39 Indeed, research on workplace burnout shows it often follows a chronic and stable pattern.40,41 Collectively, these criteria reflect the characterizations of autistic burnout reported here. Recognition of autistic burnout as a chronic health condition is a first step to raising awareness and improving detection, especially among families and health professionals.

Our findings offer a new perspective on why autistic people report lower educational attainment and higher unemployment than adults in the general population.42–44 The direct impact of burnout on physical and mental health was evident, including overwhelming exhaustion, speech difficulties, loss of skills, and impaired executive functioning. The indirect impact was also significant through its influence on educational achievement in adolescence and early adulthood. The adults described a ripple effect that included fewer employment opportunities later in life and difficulties achieving financial independence. Recovery often took months or years, with many not regaining their preburnout capabilities. Longitudinal studies of burnout among health care professionals show that burnout levels can remain stable 2 to 8 years later.45 Thus, lengthy study or career breaks due to autistic burnout could partly explain lower educational and employment achievement among autistic adults.

Notably, some adults described positive consequences of burnout, especially if it preceded an autism diagnosis, the benefits of which have been reported previously.19,46,47 Late diagnosis helped the adults in our study find the autistic community, form a positive autistic identity, implement positive career and lifestyle changes, improve self-esteem, and increase confidence to self-advocate for accommodations. This finding highlights the importance of early diagnosis and teaching autistic children effective coping mechanisms (especially during key transition stages) to circumvent the burnout cycle before it begins. The positive outcomes of early diagnosis and intervention in childhood are well established.48,49

The benefits of stimming and special interests for regulating emotions, stress management, sensory stimulation,50–55 and avoiding burnout9 have been previously reported; however, our findings suggest that each may have a unique role. Stimming provides accessible and immediate relief against emotional and sensory stressors, which could protect against autistic burnout in the short term. Many adults described masking stims to avoid discrimination and bullying and fit in with peers, which contributed to stress and overload, especially as they got older. Research shows that stimming is more socially acceptable during childhood but is deemed inappropriate in secondary school.50 Notably, many adults first experienced burnout during adolescence, suggesting that restricting stimming during a developmental period of significant change and heightened demands may be particularly harmful. A societal shift from the pathologizing/stigmatizing view of stimming could empower autistic adults to use these protective strategies more openly.

The current findings also suggest that special interests may play a background, maintenance function that contributes to well-being over the longer term. While special interests can improve coping and well-being in autistic adults,52 exhaustion during autistic burnout prevented some adults in our study from engaging with them. Conversely, others indicated that focusing on their interests too intensely contributed to autistic burnout. Previous research shows that hyperfocus can sometimes outweigh the benefits of special interests.52 Thus, the protective qualities of special interests for autistic burnout may depend on finding a balance between being pleasurable and overtaxing. Learning to regulate hyperfocus to avoid exhaustion could also protect against autistic burnout.

Many adults managed their energy strategically, applying a cost/benefit rationale to cognitive, social, and physical tasks. A popular method was “Spoon Theory,”56 which entailed allocating metaphorical spoons representing finite physical and mental energy to activities of daily living, including work, personal hygiene, and food preparation. Spoons are replenished with rest, reduced sensory input, and time with favorite activities, suggesting that using energy management techniques from an early age may be a practical and flexible strategy for preventing autistic burnout.

We identified that alexithymia might be a unique risk factor for autistic burnout. The adults with good self-awareness of their physical and emotional states described signs of looming burnout, including clusters of meltdowns and/or shutdowns and extreme fatigue. It has been estimated that up to 50% of autistic adults experience difficulties identifying, verbalizing, and analyzing emotions associated with bodily sensations.57–59 Alexithymia can affect mental health and emotion regulation and contribute to impaired interoception,60 which is the ability to perceive internal states such as hunger, muscle tension, and heart rate, and is often atypical in autism.61 Indeed, many adults in our study failed to recognize burnout symptoms until it was too late, suggesting that improving cognitive and emotional self-awareness may protect against the onset of autistic burnout.

Our findings suggest that coping strategies used by adults during autistic burnout may differ from adults in the general population. “Avoidant” coping strategies are generally used to distract from stressors and deny their impact on psychological or physical health, whereas “attention” strategies are viewed as adaptive coping as they directly address sources of stress.62 However, in our study, social and sensory avoidance were primarily used to restore energy and recover from autistic burnout. This finding suggests that avoidant behaviors may represent adaptive attention strategies that offset stressors (e.g., too much social contact, overwhelming sensory stimuli) and promote well-being. Coping research among nonautistic adults shows that withdrawal and avoidance may be positive in the short term but are harmful over time.63 Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the long-term efficacy of avoidance as a protective strategy for autistic burnout.

The overarching theme identified herein was that the onset and recurrence of autistic burnout were underpinned by stigma and a lack of awareness and acceptance regarding the diversity of autism among autistic individuals within the health care, education, employment, and social systems. Autism advocates have highlighted the importance of autism acceptance and the meaningful inclusion of autistic people in the society.64 The narrative surrounding mental illness and disabilities is usually controlled by those who do not share the lived experiences of people with these conditions.65 Therefore, amplifying the voices of autistic people and dispelling harmful autism stereotypes are essential to achieve a positive and lasting change.66

The importance of acceptance was evident through the prevalent use of masking, which most adults identified as key to the onset and recurrence of autistic burnout. Echoing previous findings,15,17 masking was used to pass as “normal” and prevent bullying, social exclusion, and discrimination resulting from negative autism stereotypes and stigma. Some adults reported internalized stigma, reported in previous research,29 including feelings of being a burden and unworthy of accommodations. Many attributed recurrent experiences of burnout to the failure of their parents, health care providers, and teachers to recognize their autistic characteristics in childhood, leading to missed or misdiagnosis and inadequate supports. Missed and late diagnoses have been identified as risk factors for mental health difficulties and lack of achievement and independence among autistic adults.67 Promoting autism acceptance may alleviate the motivations for masking and lessen the burden on autistic people.

The consequences of burnout were dire for some adults in our study, including homelessness and institutionalization. Their experiences were similar to a case study of two previously homeless autistic men who described homelessness as a “domino effect” of multiple factors, including discrimination and societal stigma, stressful life events, and employment difficulties,68 highlighting the urgent need for autism acceptance and adequate supports to prevent adverse outcomes.

Like Raymaker et al.,9 we identified a possible link between autistic burnout and suicidality, especially when adults had other mental health conditions (e.g., depression), suggesting that co-occurring conditions may be a unique risk factor for autistic burnout, possibly contributing to suicidality if they coincide. As mental health conditions are common in autistic adults,10 the relationship between co-occurring conditions, autistic burnout, and suicidality merits further investigation.

A strong sense of community and celebration of autistic strengths were evident in the posts, through reclamation of the autism label, widespread use of identity-first language,69 and the #ActuallyAutistic hashtag. The adults demonstrated empathy, offered mutual support and advice, and proactively shared information to educate others about burnout, strengthening previous research that autistic adults are experts about their lived experiences.66 Online media raises awareness, evident in the 2018 Twitter campaign, “#TakeTheMaskOff,” which highlighted the association between masking and autistic burnout and exponentially increased discussion on this topic. Our findings support research about the benefits of online communities for autistic adults, including belonging, shared identity, and positive attachment.19,70 Online communities may also provide vital support during recovery from burnout.

Interestingly, many users actively participated online during self-reported episodes of autistic burnout. Given that burnout has been characterized by overwhelming exhaustion, impaired speech processing, and poorer executive functioning,9 this noteworthy result supports previous findings of the benefits of internet-mediated communication for autistic people.70,71 Online communication alleviates some pressure associated with face-to-face communication, including eye contact and immediacy of response.70,71 This insight could inform creative avenues for supporting autistic adults through recovery from burnout when they may be unable to tolerate face-to-face appointments with health care providers.

Strengths and limitations

A major study strength was direct access to the lived experience of autistic burnout via online communication of a large sample of adults that spanned 12 years. The data provided a rich and nuanced insight into this little-studied phenomenon. Descriptions of burnout were consistent over time and platform and were constructed organically, without prompting or direction from researchers. Risk and protective factors were identified to inform future research into autistic burnout.

Nevertheless, the data were retrospective which prevented follow-up questioning about context and outcomes. As minimal demographic data were available, the sociodemographic characteristics and diversity of the sample remain unknown. Hence, it was not possible to examine the influence of gender and age on autistic burnout or investigate burnout from the perspective of individuals with additional marginalized identities (e.g., LGBTQI; female; Black). The adults had access to online platforms and could communicate in writing, however, the lived experiences of non-English-speaking autistic adults who do not use online platforms or have higher communication support needs remain unknown. Finally, despite investigating an issue of high priority for autistic adults, the study was not codesigned with autistic people.

Conclusion

Typical descriptions of autistic burnout onset during adolescence and its recurrence during transitional stages underscore the importance of educating families and health care practitioners to recognize early symptoms of autism and burnout. Our findings suggest that autism acceptance could reduce the need for effortful masking and have implications for how the education and employment sectors can support the participation of autistic people to improve their long-term well-being and quality of life. At the individual level, learning effective coping, energy management, and self-awareness skills may protect autistic adults from burnout. The adults could communicate online during periods of burnout, which has practical implications for delivering support to autistic people during burnout. Future studies should investigate risk and protective factors for autistic burnout to understand why some individuals may be more vulnerable. Finally, more research is needed to assess the prevalence of autistic burnout, develop effective screening tools, and to explore the relationship between burnout and suicidality.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all our research participants, especially those who allowed us to include extracts from their posts. We thank our autistic colleague, Katherine Gore, for her insightful and valuable feedback.

Authorship Confirmation Statement

J.M., A.L.R., and C.D. contributed to the study design. A.A. extracted the data. J.M. conducted the data analysis and wrote the article. A.L.R., C.D., and J.L. contributed to data analysis and provided critical feedback. All coauthors have reviewed and approved this article before submission. This article has been submitted solely to this journal and is not published, in press, or submitted elsewhere.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Data collection and partial data analysis for this study were completed before the publication of Raymaker et al.'s9 pioneering article about autistic burnout.

Individuals from the two online platforms are distinguished by “T” for Twitter users and “WP” for forum users. For example, (T1) refers to Twitter user number one.

References

- 1. Rose K. An autistic burnout. May 21, 2018. https:/theautisticadvocate.com/2018/05/an-autistic-burnout/ Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 2. Schaufeli WB, Greenglass ER. Introduction to the special issue on burnout and health issue. Psychol Health. 2001;16(5):501–510. 10.1080/08870440108405523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, Christensen KB. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):192–207. 10.1080/02678370500297720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gustafsson H, Kentta G, Hassmen P. Athlete burnout: An integrated model and future research directions. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;4(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mikolajczak M, Roskam I. A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The balance between risks and resources (BR2). Front Psychol. 2018;9:e00886. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boujut E, Popa-Roch M, Palomares EA, Dean A, Cappe E. Self-efficacy and burnout in teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2017;36:8–20. 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reiter S, Vitani T. Inclusion of pupils with autism: The effect of an intervention program on the regular pupils' burnout, attitudes and quality of mediation. Autism. 2007;11(4):321–333. 10.1177/1362361307078130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Varghese RT, Venkatesan S. A comparative study of maternal burnout in autism and hearing impairment. Int J Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;1(2):101–108. 10.5958/j.2320-6233.1.2.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raymaker DM, Teo AR, Steckler NA, et al. “Having all of your internal resources exhausted beyond measure and being left with no clean-up crew”: Defining autistic burnout. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(2):1–12. 10.1089/aut.2019.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:819–829. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uljarević M, Hedley D, Foley KR, et al. Anxiety and depression from adolescence to old age in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2020;50(9):3155–3165. 10.1007/s10803-019-04084-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cassidy S, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S. Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Mol Autism. 2018;9(42):1–14. 10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hedley D, Uljarević M. Systematic review of suicide in autism spectrum disorder: Current trends and implications. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2018;5:65–76. 10.1007/s40474-018-0133-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, et al. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:232–238. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cage E, Troxell-Whitman Z. Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:1899–1911. 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Livingston LA, Shah P, Happé F. Compensatory strategies above and below the behavioural surface in autism: A qualitative study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;6(9):766–777. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30224-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hull L, Petrides KV, Allison C, et al. “Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:2519–2534. 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baldwin S, Costley D. The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(4):483–495. 10.1177/1362361315590805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stagg SD, Belcher H. Living with autism without knowing: Receiving a diagnosis in later life. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2019;7(1):348–361. 10.1080/21642850.2019.1684920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Camm-Crosbie L, Bradley L, Shaw R, Baron-Cohen S, Cassidy S. ‘People like me don't get support’: Autistic adults' experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism. 2019;23(6):1431–1441. 10.1177/1362361318816053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Doyle N. Neurodiversity at work: A biopsychosocial model and the impact on working adults. Br Med Bull. 2020;135(1):108–125. 10.1093/bmb/ldaa021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lewis L F. A mixed methods study of barriers to formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(8):2410–2424. 10.1007/s10803-017-3168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bargiela S, Steward R, Mandy W. The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46(10):3281–3294. 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Duvekot J, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, et al. Factors influencing the probability of a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in girls versus boys. Autism. 2017;21(6): 646–658. 10.1177/1362361316672178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dworzynski K, Ronald A, Bolton P, Happé F. How different are girls and boys above and below the diagnostic threshold for autism spectrum disorders? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(8):788–797. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kreiser NL, White SW. ASD in females: Are we overstating the gender difference in diagnosis? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2014;17:67–84. 10.1007/s10567-013-0148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Auyeung B, Chakrabarti B, Baron-Cohen S. Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(1):11–24. 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nicolaidis C, Schnider G, Lee J, et al. Development and psychometric testing of the AASPIRE Adult Autism Healthcare Provider Self-Efficacy Scale. Autism. 2021;25(3):767–773. 10.1177/1362361320949734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Botha M, Frost DM. Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Soc Ment Health. 2020;10(1):20–34. 10.11177/21568693188044297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thompson-Hodgetts S, Labonte C, Mazumder R, Phelan S. Helpful or harmful? A scoping review of perceptions and outcomes of autism diagnostic disclosure to others. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2020;77:101598. 10.1016/j.rasd.2020.101598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cage E, Di Monaco J, Newell V. Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48:473–484. 10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P, ed. Handbook of Research Methods in Health and Social Sciences. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte. Ltd.; 2019:843–860. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W, eds. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.; 2017:17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238. [DOI]

- 35. Leadbitter K, Leneh Buckle K, Ellis C, Dekker M. Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Front Psychol. 2021;12:635690. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Braun V, Clarke V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London, Sage Publications Ltd.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization. Chronic conditions: The health care challenge of the 21st century. In: Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions: Building Blocks for Action: Global Report. 2002:11–26. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/ Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 39. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 7A00 Chronic insomnia. May, 2021. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/323148092 Accessed May 18, 2021.

- 40. Bakker AB, Costa PL. Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: A theoretical analysis. Burn Res. 2014;1:112–119. 10.1016/j.burn.2014.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kavalieratos D, Siconolfi DE, Steinhauser K, et al. ‘It is like heart failure. It is chronic…and it will kill you”: A qualitative analysis of burnout among hospice and palliative care clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):901–910. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings. October 24, 2019. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/disability/disability-ageing-and-carers-australia-summary-findings/latest-release#autism-in-australia (accessed November 10, 2019).

- 43. Flower RL, Richdale AL, Lawson LP. Brief report: What happens after school? Exploring post-school outcomes for a group of autistic and non-autistic Australian youth. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51(4):1385–1391. 10.1007/s10803-020-04600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Taylor JL, Henninger NA, Mallick MR. Longitudinal patterns of employment and postsecondary education for adults with autism and average-range IQ. Autism. 2015;19(7):785–793. 10.1177/1362361315585643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schaufeli WB, Maassen GH, Bakker AB, Sixma HJ. Stability and change in burnout: A 10-year follow-up study among primary care physicians. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2011;84:248–267. 10.1111/j.2044-83255.2010.02013.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Botha M, Dibb B, Frost DM. “Autism is me”: An investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disabil Soc. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1080/09687599.2020.1822782. [DOI]

- 47. Kock E, Strydom A, O'Brady D, Tantam D. Autistic women's experience of intimate relationships: The impact of an adult diagnosis. Adv Autism. 2019;5(1):38–49. 10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Clark MLE, Vinen Z, Barbaro J, Dissanayake C. School age outcomes of children diagnosed early and later with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(1):92–102. 10.1007/s10803-017-3279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Ashbaugh K, Bradshaw J. The importance of early identification and intervention for children with or at risk for autism spectrum disorders. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(1):50–56. 10.3109/17549507.2013.861511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kapp SK, Steward R, Crane L, et al. ‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults' views and experiences of stimming. Autism. 2019;23(7):1782–1792. 10.1177/1362361319829628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Manor-Binyamini I, Schreiber-Divon M. Repetitive behaviours: Listening to the voice of people with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2019;64:23–30. 10.1016/j.rasd.2019.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grove R, Hoekstra RA, Wierda M, Begeer S. Special interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Res. 2018;135:766–775. 10.1002/aur.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Goldfarb Y, Gal E, Golan O. A conflict of interests: A motivational perspective on special interests and employment success of adults with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:3915–3923. 10.1007/s10803-019-04098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jordan CL, Caldwell-Harris C. Understanding differences in nonautistic and autism spectrum special interests through internet forums. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;50(5):391–402. 10.1352/1934-9556-50.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Teti M, Cheak-Zamora N, Lolli B, Maurer-Batjer A. Reframing autism: Young adults with autism share their strengths through photo-stories. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31:619–629. 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miserandino C. The Spoon Theory. 2003. http://butyoudontlooksick.com/articles/written-by-christine/the-spoon-theory/ (accessed July 10, 2021).

- 57. Berthoz S, Hill EL. The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:291–298. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hill E, Berthoz S, Frith U. Brief report: Cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives. J Autism Dev Disord. 2004;34(2):229–235. 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022613.41399.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Oakley BFM, Jones EJH, Crawley D, et al. Alexithymia in autism: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with social-communication difficulties, anxiety and depression symptoms. Psychol Med. 2020:1–13. [Epub ahead of print]; 10.1017/S0033291720003244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shah P, Hall R, Catmur C, Bird G. Alexithymia, not autism, is associated with impaired interoception. Cortex. 2016;81:215–220. 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. DuBois D, Ameis SH, Lai MC, Casanova MF, Desarkar P. Interoception in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2016;52:1044–1111. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Suls J, Fletcher B. The relative efficacy of avoidant and nonavoidant coping strategies: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 1985;4(3):249–288. 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart. Work Stress. 2005;19(3):256–262. 10.1080/02678370500385913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Autistic Self Advocacy Network. Acceptance is an action: ASAN statement on 10th anniversary of AAM. April 2, 2021. https://autisticadvocacy.org/2021/04/acceptance-is-an-action-asan-statement-on-the-10th-anniversary-of-aam/ Accessed May 18, 2021.

- 65. Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp SK, Brooks PJ, Pickens J, Schwartzman B. Whose expertise is it? Evidence for autistic adults as critical autism experts. Front Psychol. 2017;8:e00438. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Portway SM, Johnson B. Do you know I have Asperger's syndrome? Risks of a non-obvious disability. Health Risk Soc. 2005;7(1):73–83. 10.1080/09500830500042086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stone B. ‘The domino effect’: Pathways in and out of homelessness for autistic adults. Disabil Soc. 2019;34(1):169–174. 10.1080/09687599.2018.1536842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bury SM, Jellett R, Spoor JR, Hedley D. “It defines who I am” or “it is something I have”: What language do [autistic] Australian adults [on the autism spectrum] prefer? J Autism Dev Disord. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]; https://doi.org/0.1007/s10803-020-04425-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haney JL, Cullen JA. Learning about the lived experiences of women with autism from an online community. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2017;16(1):544–573. 10.1080/1536710X.2017.1260518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp SK, Shane-Simpson C, Shane Smith D, Hutman T. Intersections between the autism spectrum and the internet: Perceived benefits and preferred functions of computer-mediated communication. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;52(6):456–469. 10.1352/1934-9556-52.6.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]