Abstract

Background:

Millions of rural U.S. households are heated with wood stoves. Wood stove use can lead to high indoor concentrations of fine particulate matter [airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter ()] and is associated with lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in children.

Objectives:

We assessed the impact of low-cost educational and air filtration interventions on childhood LRTI and indoor in rural U.S. homes with wood stoves.

Methods:

The Kids Air Quality Interventions for Reducing Respiratory Infections (KidsAIR) study was a parallel three-arm (education, portable air filtration unit, control), post-only randomized trial in households from Alaska, Montana, and Navajo Nation (Arizona and New Mexico) with a wood stove and one or more children of age. We tracked LRTI cases for two consecutive winter seasons and measured indoor over a 6-d period during the first winter. We assessed results using two analytical frameworks: a) intervention efficacy on LRTI and (intent-to-treat), and b) association between and LRTI (exposure–response).

Results:

There were 61 LRTI cases from 14,636 child-weeks of follow-up among 461 children. In the intent-to-treat analysis, children in the education arm [; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.35, 2.72] and the filtration arm (; 95% CI: 0.46, 3.32) had similar odds of LRTI vs. control. Geometric mean concentrations were similar to control in the education arm (11.77% higher; 95% CI: , 49.72) and air filtration arm (6.96% lower; 95% CI: , 24.55). In the exposure–response analysis, odds of LRTI were 1.45 times higher (95% CI: 1.02, 2.05) per interquartile range () increase in mean indoor .

Discussion:

We did not observe meaningful differences in LRTI or indoor in the air filtration or education arms compared with the control arm. Results from the exposure–response analysis provide further evidence that biomass air pollution adversely impacts childhood LRTI. Our results highlight the need for novel, effective intervention strategies in households heated with wood stoves. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP9932

Introduction

Nearly homes in the United States (U.S.) burn wood fuel in wood stoves or fireplaces as a primary or secondary heating source (EIA 2015). Approximately half of such homes use freestanding wood stoves with a removable chimney, as opposed to a built-in fireplace (EIA 2015). Many wood stoves are older, inefficient models with inadequate ventilation that can lead to poor indoor air quality (U.S. EPA 2013). Although there is no U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) air quality standard for indoor environments, concentrations of fine particulate matter [airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter ()] within wood stove homes often exceed U.S. EPA health-based ambient air quality standards of over a 24-h period or a annual mean (U.S. EPA 2016). For example, indoor concentrations of 20–, including periods of peak concentrations an order of magnitude higher, have been measured in rural U.S. homes with wood stoves (Noonan et al. 2012a; Semmens et al. 2015; Singleton et al. 2017; Walker et al. 2021; Ward et al. 2008).

Few studies have assessed the health effects of indoor residential wood smoke exposures in developed countries. Associations have been reported between ambient air pollution, primarily from residential wood burning in fireplaces and wood stoves, and outcomes of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and hospital admissions related to asthma (Sigsgaard et al. 2015). Wood stove use is associated with decreased lung function and increased respiratory symptoms in children; however, results have been inconsistent and studies have been limited by self-reported exposure assessment (Guercio et al. 2021; Rokoff et al. 2017). The need for further assessment of the health effects of wood stoves in developed countries among children has been emphasized (Guercio et al. 2021; Rokoff et al. 2017) given that children are especially vulnerable to inhaled pollutants owing to multiple factors, including lung development during childhood and higher minute ventilation relative to body weight compared with adults (Bateson and Schwartz 2008).

In the United States, acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is the leading cause of childhood hospitalization, with disproportionately higher rates among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations (Foote et al. 2015). There is evidence from studies in lower- and middle-income countries that indoor biomass air pollution from cookstoves is a risk factor for LRTI in children of age (Adaji et al. 2019; Bruce et al. 2015; Kinney et al. 2021; Smith et al. 2011). Randomized controlled trials in such settings have assessed the impact of improved cookstove interventions on indoor air pollution and child birth and respiratory outcomes (Clasen et al. 2020; Jack et al. 2015; Mortimer et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2011). Although results are forthcoming from the most recent trials, two previous cleaner cookstove interventions have reported limited success with small (Smith et al. 2011) to no benefit (Mortimer et al. 2017) on child respiratory infections.

In contrast to the work in lower- and middle-income countries, no previous interventions have aimed to reduce childhood LRTI among U.S. homes with wood stoves, although there have been previous interventions targeting indoor concentrations in such households. Portable air filtration units have reduced indoor by over 50% among households with wood stoves (Allen et al. 2011; Hart et al. 2011; Wheeler et al. 2014), and in one study were associated with improved endothelial function and decreased inflammatory biomarkers in healthy adults (Allen et al. 2011). In rural areas of Montana, Idaho, and Alaska, an air filtration unit intervention reduced indoor by 66% relative to control in homes with wood stoves (McNamara et al. 2017; Ward et al. 2017). Improvements in peak flow variability were observed among children with asthma living in the homes, but the intervention was not associated with improved scores from the Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (Noonan et al. 2017). Several communities have engaged in buyback and credit-based programs to upgrade residences to wood-burning stoves with higher combustion efficiencies and lower emissions (Allen et al. 2009; Ward et al. 2010, 2011). The largest such demonstration of wood stove technology upgrades took place in over 1,100 households from a rural community in Montana. The wood stove upgrades resulted in 27.6% lower ambient wintertime (Noonan et al. 2012b) and lower indoor [; 95% confidence interval (CI): , ] in a subset of 21 homes (Noonan et al. 2012a). Promotion of best burn practices has been recommended by the U.S. EPA as a way to reduce emissions from residential wood stoves (U.S. EPA 2021), but scientific studies of education-based interventions that demonstrate changes in indoor air quality and associated health effects are missing.

Overall, the impact of interventions on health outcomes in U.S. wood stove users, particularly among vulnerable populations, such as children, remains largely unknown. We aimed to inform this important gap in the literature by conducting a randomized field trial called the Kids Air Quality Interventions for Reducing Respiratory Infections (KidsAIR) study. The primary aim of the trial was to reduce incidence of LRTI among children of age who resided in the study households. We also evaluated the impact of the interventions on indoor concentrations of and assessed associations between indoor and LRTI.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

A description of the KidsAIR rationale and methods has been published previously (Noonan et al. 2020). KidsAIR was a three-arm randomized, placebo-controlled intervention trial among rural U.S. households that used wood stoves as a primary heating source. KidsAIR took place in rural communities from the three U.S. regions of Alaska (AK), Navajo Nation (NN) in Arizona and New Mexico, and Western Montana (WMT). The trial used a post-only design appropriate for assessing respiratory outcomes that decrease in incidence as children age. Previous trials that have assessed respiratory infections in children have used similar designs (Mortimer et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2011). Participation occurred over the course of two winter seasons during which LRTI events were tracked among the children enrolled in the study. Households and participants were recruited over a 5-y study period (2014–2018), with households within each study area that began during the same winter season considered part of the same study cohort.

Recruitment, Eligibility Criteria, and Informed Consent

The KidsAIR study took place in rural areas of AK, NN, and WMT where wood stoves are a common source of heating during the colder winter months. The recruitment target sample size was 324 households, assuming an average of 1.5 children of age per household, for a total target sample size of 486 children. The target recruitment numbers were based on a combination of previous literature, estimated occurrence of LRTI among the population, and power calculations (Noonan et al. 2020). Eligibility criteria for the trial included households that used a wood stove as a primary heating source and had at least 1 child resident of age. Based on community-informed input, households were not excluded from participation if a household member smoked tobacco products. An adult caregiver in each household provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Participants were compensated for the time they spent performing study tasks and reimbursed for the cost of electricity to use the air filtration units. Following the study, all households received the educational tools as well as the air filtration units used in the Education and Filtration study arms. The KidsAIR study was approved by the University of Montana Institutional Review Board (IRB), the University of Alaska Fairbanks IRB, the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Human Research Protection Office and Human Research Review Committee, the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board, and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation Human Studies Committee and Executive Board. The KidsAIR trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under trial number NCT02240134.

Randomization and Treatment Arms

Treatment arms were randomly assigned at the household level by researchers at the University of Montana, and interventions were implemented by field personnel prior to each cohort’s first winter of observation. Randomization to treatment arms followed a stratified, blocked randomization approach (Noonan et al. 2020). Households were grouped into strata by study area (AK, NN, and WMT) and age of the youngest child in the household ( vs. 1–4 y). As households were enrolled, randomization occurred within blocks of three households in each stratum to ensure treatment arms were similar in size. The three study treatment arms included an educational intervention (Education arm), a portable air filtration unit intervention (Filtration arm), and a control group (Control arm). The Education arm households received an educational intervention that included curriculum on methods for optimally treating (e.g., drying) and burning wood fuel with the help of low-cost tools, such as moisture meters, fire starters, and wood stove thermometers (see the section “Wood Stove Best Burn Summary” in the Supplemental Material for the curriculum summary). At the beginning of the study, field staff delivered individual, in-person training on the education curriculum for each household (Noonan et al. 2020). In the NN and WMT study areas, the training included videos adapted to each location with input from the community. In the AK study area, the training included a flipchart that was based on community feedback. At all study locations, field staff used a checklist after the training to assess knowledge and reinforce concepts. Prior to the second winter of participation for the Education arm, the field staff reviewed the education curriculum and checklist with each household. Filtration arm households received a portable air filtration unit (Filtrete FAP03 and FAP02, 3M Company; Honeywell 50250, Honeywell International Inc.; or Winix 5500 and 5300, Winix America Inc.) and were instructed to leave the unit on continuously, operating on the highest setting in the same room as the wood stove. Initially, the Filtrete unit was chosen for use in the study on the basis of its ideal combination of price, availability, clean air delivery rate (CADR), and ratings for larger room sizes. However, production of the Filtrete unit was discontinued prior to completion of the KidsAIR study, so other models (Winix and Honeywell) were selected for use in the study on the basis of comparable price and CADR relative to the Filtrete unit. Study coordinators assessed the air filtration units and replaced the filters as needed during monthly household visits. Implementation of the Control arm varied by study area depending on culturally appropriate recommendations by community stakeholders (Noonan et al. 2020). The NN and WMT study areas used a sham filtration unit (i.e., with no filter inside the unit) for the Control arm; at the request of Tribal leadership, no intervention was used in the AK Control arm.

Exposure Assessment

Exposure assessment methods and results from homes in the Control arm have been published previously (Walker et al. 2021). Briefly, we measured real-time mass concentrations of over a 6-d period at 60-s intervals using a light-scattering aerosol monitor (DustTrak 8530, TSI). Sampling occurred at least 1 month after the interventions were implemented and during the first winter of the study for each household. The DustTrak monitors sampled continuously over the 6-d period with the instrument located 1– above ground level in the room where the wood stove was located. The DustTrak instruments were cleaned and zero calibrated according to manufacturer standards prior to each sampling event. Given that the indoor sampling was conducted near the wood stoves, our assumption was that the wood stoves were the dominant sources of indoor in the sampling area. A source-specific wood smoke correction factor of 1.65 was applied to the DustTrak concentrations based on previous sampling during wood smoke events alongside reference monitors (McNamara et al. 2011).

LRTI Assessment

Cases of LRTI were identified by a pediatric pulmonologist using medical records, caregiver-reported symptoms, and health assessments conducted by study coordinators during household visits. Study coordinators located within the AK, NN, and WMT areas visited each household once per month to conduct a health assessment on each child enrolled in the study. The health assessments included lung sounds, temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, and oxygen saturation. All field personnel who collected health measures were trained annually by a pediatric pulmonologist (coauthor P.G.S.) or respiratory therapist. Trainings were adapted from standardized methods for case assessment in field settings (WHO 1997) that have been used in previous studies on wood stove interventions and childhood respiratory infection (Bruce et al. 2007). Trainings were primarily conducted in person, although a few refresher trainings in later years were conducted via teleconference for remote study personnel. The study coordinators also administered a Child Symptom Questionnaire (CSQ) with the primary caregiver during household visits. The CSQ first asked if the child had been sick in the past 2 wk. If so, the caregiver was prompted to answer questions about symptoms (i.e., fever, rapid/difficult/noisy breathing, runny nose, cough, wheezing), when the symptoms started, and if the child had seen a medical provider as a result of the illness. If the child had seen a medical provider, the caregiver was asked to report the clinician-provided diagnosis and any new medications prescribed to the child. Caregivers were contacted during the period between monthly household visits so that a CSQ could be administered every 2 wk for LRTI tracking purposes; contact methods varied by community setting/preference and were conducted by telephone, email, or in person. In addition, caregivers were instructed to contact study coordinators in between scheduled visits if a child began showing signs/symptoms of LRTI. In such cases, study coordinators would make a home visit to conduct a health assessment within 48 h.

The pediatric pulmonologist on our study team was masked to treatment arm assignment and reviewed all CSQs, health assessments, and medical records over the duration of the study to identify cases of LRTI. An illness was deemed as an LRTI based on a licensed health care provider’s diagnosis (from medical records) that met the case definition of croup, bronchiolitis, pneumonia (or other lung infections), bronchitis, or tracheitis. We did not include upper respiratory tract infections (e.g., rhinitis or otitis media) in the case definition. The health care providers that the children saw had no knowledge of the study or treatment arm assignment, nor did they have any communication with the pulmonologist on our study team. If medical professionals were not involved in a child’s care during a particular illness, the LRTI case definition was based on criteria from in-home health assessments instead of medical record diagnoses. Specifically, the LRTI definition from in-home health assessments was new onset of lower respiratory tract symptoms (e.g., cough or wheezing) along with fever and upper respiratory tract signs (e.g., coryza). Although low pulse oximetry readings, abnormal breath sounds, or tachypnea were used to support the diagnosis of LRTI, the case definition still required a health professional confirmation or objective lower tract signs.

For purposes of analysis, we identified LRTI events and the number of weeks of follow-up during which each child was considered at-risk of LRTI. Person-time at risk for each child began 14 d after the household intervention date for each winter season and continued through the following 30 April or the date of the final CSQ for each child, whichever came first. Once an LRTI diagnosis was made, start and end dates for each LRTI case were determined using a combination of caregiver-reported symptom onset dates from the CSQs, health assessments, and medical records. Children were not considered at risk of a new LRTI event from the time period between the start date of each LRTI event until 14 d after the LRTI end date; these periods were removed from each child’s person-time at-risk. If an LRTI was confirmed with a start date that fell within 14 d of a previous LRTI end date, they were considered to be a single LRTI event.

Covariates

The overall quality of the wood stoves was assessed by caregiver-reported age of the stoves and by using a novel wood stove quality grading method. For this grading method, an expert, independent wood stove consultant who had no other involvement in the study assessed photos of the wood stove, stovepipe, chimney, and wood storage. Each stove was assigned a grade of high, medium, or low quality based on the wood supply, the integrity and design of the stove and chimney system, and the operation and maintenance of the stove. In general, the stove grade assessment strategy was successful, and wood stove grades were associated with concentrations (i.e., levels went up as stove grade declined). These associations are described in a previous paper from the study on household and exposure characteristics (Walker et al. 2021).

Caregivers self-reported wood stove practices during a typical winter season, including type of wood burned, wood collection method (i.e., purchase or harvest), the length of time they allowed the wood to dry prior to burning, and time since the chimney was last cleaned. During the 6-d sampling period, caregivers self-reported stove use compared with a typical winter season (i.e., no burning, light burning, average burning, heavy burning). Caregivers also reported household activities during each sampling day that may have impacted the measured concentrations (i.e., tobacco/other smoking, opening of windows or doors, and household cleaning). These variables, collected once per day during the 6-d sampling period, were summed to produce a single value for the sampling period for each home. For example, if a caregiver opened windows during three of the six sampling days, they would be assigned a 3 for a variable indicating days with self-reported windows open during the sampling period. In addition, caregivers recorded when each child was present at the study household over the duration of the 6-d sampling period. This information was used to calculate concentrations during the periods when the children were at home, as opposed to somewhere outside the home, such as child care. Kilowatt measurement devices (Kill A Watt, P3 International Corporation) were used in each household to measure kilowatt usage by the air filtration units; measures of compliance were calculated based on percentage expected kilowatt usage compared with laboratory tests for each filter unit/setting.

Study coordinators administered questionnaires to the caregiver at the beginning of each winter season to collect information on demographic and household characteristics. Demographic characteristics included age, sex, and race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Black or African American, White, more than one race) and ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino, not Hispanic or Latino) of children and caregivers, household income, caregiver education level, child influenza vaccination status, and number of total residents in each household. Household characteristics included number of levels in the home, size of the home (in square meters), number of bedrooms in the home, number of pets in the home, age of the home, and whether or not any residents smoked inside or outside the home. Post-winter questionnaires were also administered to assess the frequency of intervention use and the perceived helpfulness of the interventions during the previous winter. We collected ambient temperature and data over the duration of the study from the weather station (National Climatic Data Center 2020) and U.S. EPA monitor (U.S. EPA 2020) nearest to each study household.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was conducted using R (version 3.6.2; R Development Core Team). We calculated descriptive statistics for continuous variables [, mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum (min), median (med), maximum (max)] and categorical variables (, percentage of total) across all study households and separately for each treatment arm and study area. We averaged indoor concentrations of over the 6-d sampling period for each home and for the times during which each child was reported as being at the household.

Primary analyses were conducted within three model frameworks using the lme4 package (Bates et al. 2015): a) intent-to-treat (ITT) framework with LRTI outcome (ITT-LRTI), b) ITT framework with outcome (), and c) exposure–response (ER) framework with LRTI as the outcome and as the exposure of interest. Although LRTI cases were collected as count data, very few children had more than one LRTI, resulting in underdispersed data that violated the assumptions of attempted Poisson and negative binomial regression models. Thus, the ITT-LRTI framework used mixed effects logistic regression models (using the glmer function) with the presence of LRTI (yes or no) as the outcome and assigned treatment as the exposure of interest. The ITT-LRTI models included a covariate for person-time at risk to account for the wide variability of child-weeks at risk across study participants. The models also included a covariate for child age ( vs. 1–4 y) because randomization occurred within strata of this term. A nested random term (i.e., household:cohort:area) was included in the model to account for repeated measures clustered within household, cohort, and study area. The framework used mixed effects linear models (using the lmer function) with mean 6-d indoor concentration as the outcome and assigned treatment as the exposure of interest. Models were adjusted for child age and included a nested random term of cohort:area (there were no repeated measures within household for ). Both ITT models used the study’s randomization and were not adjusted for potential confounding variables in the primary analyses.

The ER framework used mixed effects logistic regression models (using the glmer function) with the presence of LRTI (yes or no) as the outcome and mean 6-d indoor concentration as the exposure of interest. As with the ITT-LRTI models, the ER models were adjusted for person-time at risk and included a nested random term (i.e., household:cohort:area) to account for repeated measures in the analysis. In addition, because the ER models did not use the study’s randomization to help control for confounding, covariates were included in the model to adjust for potential confounders. Confounders were identified a priori through previous literature and by assessing independent associations with the exposure and outcomes of interest (Adaji et al. 2019; Mortimer et al. 2017; Noonan et al. 2020; Smith et al. 2011; Walker et al. 2021). We also used directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) to assess the direction and potential relationship between indoor , LRTI, and covariates (Figure S1). Final ER models were adjusted for child age and sex, caregiver race and sex, household income, caregiver education, whether a household resident smoked, and ambient temperature and .

The primary ITT model framework was prespecified in our previously published methods paper (Noonan et al. 2020). We conducted a number of sensitivity analyses in all model frameworks that were specified a priori (during the initial model development when the analyst was masked to treatment arm assignment) and assessed the impact of including potential confounders in the models and using subsets of the data. We conducted sensitivity analyses by including potential confounders that had some imbalance across study arms (ITT frameworks) or by including additional potential confounders not included in the primary model (ER framework). Because of the different control treatment in AK (no filtration unit), we conducted the ITT-LRTI and analyses with AK households excluded from the data set. For the ITT-LRTI and ER frameworks, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis with a data set restricted to Winter 1 only because this was the only winter of observation when indoor was sampled. For the ER framework, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis that used indoor when each child was at home as the primary exposure variable in place of indoor over the entire sampling period.

We also conducted some post hoc sensitivity analyses for the ITT-LRTI framework with other model variations to provide insight into our primary model selection and results. Specifically, we assessed models that a) used study area (AK, NN, WMT) as a fixed effect rather than a random nested term, b) removed the covariate for person-time at risk, and c) removed the random nested term for household.

We evaluated potential modification of the effect of the treatments by a priori–selected child, caregiver, and home characteristics within each of the model frameworks by including interaction terms in the primary model. We assessed significance of the interaction terms using type II Wald chi-square tests. Model assumptions were evaluated in all analysis frameworks. Indoor concentrations were natural-log transformed in the framework, and estimates are presented as percentage difference in geometric mean .

Results

Household and Demographic Characteristics

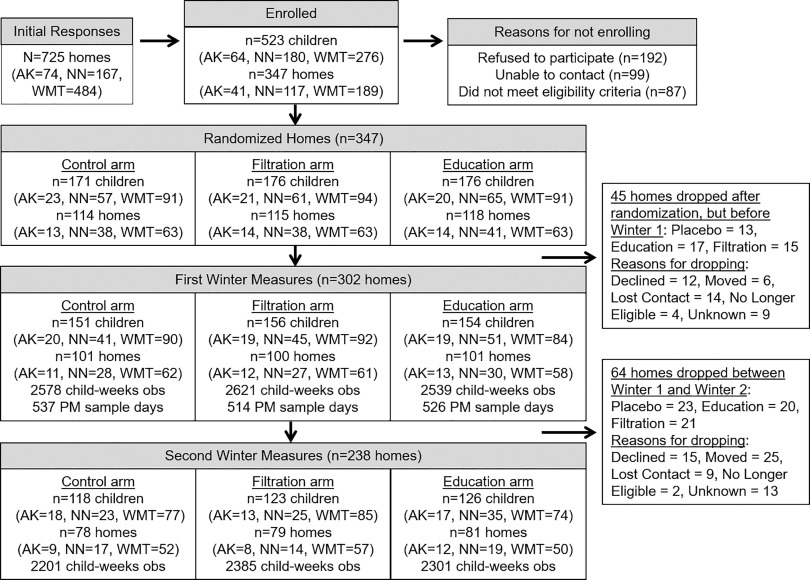

From an initial pool of 725 homes, 347 homes with 523 children were randomized to one of the three study arms (Figure 1). Some enrolled homes were not retained through the initial first winter LRTI assessments (), leaving a total of 302 households and 461 children who participated in at least one winter of the KidsAIR study (Figure 1). Demographic, household, and wood stove characteristics are presented for all study households and by treatment arm in Table 1. The majority of caregivers were female (85%), and most reported their race as either White (54%) or AI/AN (38%). A similar number of caregivers reported household incomes of (30%), (34%), and (34%). Self-reported education was distributed relatively evenly across high school (31%), some college (30%), and college degree (37%). Relatively few households had a resident who smoked tobacco products (17%), and only 2% reported smoking indoors. Caregivers reported a wide range of ages for the wood stoves, with similar numbers reported as (33%), 6–15 (33%), and years of age (26%). Nearly half of the wood stoves were graded as medium quality (48%), with only 7% graded as high quality using the wood stove grading system developed by our wood stove expert consultant. Over half of the caregivers reported that they harvested their own wood fuel (62%), and 50% said they allowed their wood to dry months prior to burning. Further descriptive statistics are included in the Supplemental Material, including indoor concentrations and LRTI cases stratified by sociodemographic characteristics and study arm (Table S1), as well as results from post-winter questionnaires on intervention use (Tables S2 and S3).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment, enrollment, and retention. Note: AK, Alaska study region; NN, Navajo Nation study region; obs, observation; PM, particulate matter; WMT, Western Montana study region.

Table 1.

Household-level demographic and wood stove characteristics among rural U.S. homes participating in the KidsAIR study, 2014–2020.

| Characteristics | All households () | Arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control () | Filter () | Education () | ||

| Caregiver sex [ (%)] | ||||

| Female | 258 (85) | 91 (90) | 85 (85) | 82 (81) |

| Male | 40 (13) | 10 (10) | 14 (14) | 16 (16) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Caregiver race [ (%)] | ||||

| AI/AN | 116 (38) | 38 (38) | 38 (38) | 40 (40) |

| Asian | 1 () | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| White | 163 (54) | 56 (55) | 57 (57) | 50 (50) |

| More than 1 race | 18 (6) | 6 (6) | 4 (4) | 8 (8) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Caregiver ethnicity [ (%)] | ||||

| Hispanic | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Not Hispanic | 292 (97) | 100 (99) | 97 (97) | 95 (94) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Caregiver education [ (%)] | ||||

| High school or less | 95 (31) | 33 (33) | 26 (26) | 36 (36) |

| Some college | 91 (30) | 28 (28) | 34 (34) | 29 (29) |

| College degree | 112 (37) | 40 (40) | 39 (39) | 33 (33) |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Household income [ (%)] | ||||

| < | 91 (30) | 35 (35) | 26 (26) | 30 (30) |

| 103 (34) | 34 (34) | 30 (30) | 39 (39) | |

| 104 (34) | 32 (32) | 43 (43) | 29 (29) | |

| Missing | 4 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Children of age in household () [ (%)] | ||||

| 1 | 183 (61) | 63 (62) | 60 (60) | 60 (59) |

| 2 | 91 (30) | 32 (32) | 31 (31) | 28 (28) |

| 3 | 19 (6) | 3 (3) | 6 (6) | 10 (10) |

| 4 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | NA |

| 5 | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | NA |

| Missing | 5 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Levels in home () [ (%)] | ||||

| 1 | 194 (64) | 64 (63) | 63 (63) | 67 (66) |

| 101 (33) | 35 (35) | 35 (35) | 31 (31) | |

| Missing | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Home area () [ (%)] | ||||

| 137 (45) | 47 (47) | 42 (42) | 48 (48) | |

| 127 (42) | 40 (40) | 48 (48) | 39 (39) | |

| Missing | 38 (13) | 14 (14) | 10 (10) | 14 (14) |

| Bedrooms in home () [ (%)] | ||||

| 0 | 6 (2) | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 22 (7) | 6 (6) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) |

| 2 | 54 (18) | 25 (25) | 15 (15) | 14 (14) |

| 213 (71) | 64 (63) | 74 (74) | 75 (74) | |

| Missing | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Age of home [ (%)] | ||||

| Built before 1985 | 138 (46) | 52 (51) | 39 (39) | 47 (47) |

| Built 1985 or later | 147 (49) | 45 (45) | 56 (56) | 46 (46) |

| Missing | 17 (6) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 8 (8) |

| Pets in home () [ (%)] | ||||

| 0 | 83 (27) | 24 (24) | 28 (28) | 31 (31) |

| 1 | 73 (24) | 24 (24) | 24 (24) | 25 (25) |

| 139 (46) | 51 (50) | 46 (46) | 42 (42) | |

| Missing | 7 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| Resident smokes [ (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 51 (17) | 20 (20) | 13 (13) | 18 (18) |

| No | 221 (73) | 70 (69) | 77 (77) | 74 (73) |

| Missing | 30 (10) | 11 (11) | 10 (10) | 9 (9) |

| Resident smokes inside [ (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

| No | 165 (55) | 60 (59) | 52 (52) | 53 (52) |

| Missing | 130 (43) | 39 (39) | 47 (47) | 44 (44) |

| Age of stove (y) [ (%)] | ||||

| 99 (33) | 31 (31) | 34 (34) | 34 (34) | |

| 6–15 | 99 (33) | 34 (34) | 33 (33) | 32 (32) |

| 78 (26) | 27 (27) | 26 (26) | 25 (25) | |

| Unknown | 13 (4) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Missing | 13 (4) | 4 (4) | 5 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Chimney last cleaned (months ago) [ (%)] | ||||

| 143 (47) | 41 (41) | 53 (53) | 49 (49) | |

| 6–12 | 66 (22) | 27 (27) | 16 (16) | 23 (23) |

| 81 (27) | 28 (28) | 28 (28) | 25 (25) | |

| Missing | 12 (4) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Relative self-reported burn level during sampling [ (%)] | ||||

| No/light burning | 70 (23) | 19 (19) | 24 (24) | 27 (27) |

| Average burning | 155 (51) | 58 (57) | 46 (46) | 51 (50) |

| Heavy burning | 48 (16) | 17 (17) | 18 (18) | 13 (13) |

| Missing | 29 (10) | 7 (7) | 12 (12) | 10 (10) |

| Wood collection method [ (%)] | ||||

| Harvest yourself | 188 (62) | 61 (60) | 65 (65) | 62 (61) |

| Purchase/other | 84 (28) | 32 (32) | 23 (23) | 29 (29) |

| Missing | 30 (10) | 8 (8) | 12 (12) | 10 (10) |

| Wood collection time frame (months before burning) [ (%)] | ||||

| 122 (40) | 42 (42) | 40 (40) | 40 (40) | |

| 150 (50) | 52 (51) | 48 (48) | 50 (50) | |

| Missing | 30 (10) | 7 (7) | 12 (12) | 11 (11) |

| Wood stove grade (quality) [ (%)] | ||||

| High | 20 (7) | 8 (8) | 5 (5) | 7 (7) |

| Medium | 144 (48) | 49 (49) | 45 (45) | 50 (50) |

| Low | 65 (22) | 24 (24) | 19 (19) | 22 (22) |

| Missing | 73 (24) | 19 (19) | 31 (31) | 22 (22) |

Note: AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; KidsAIR, Kids Air Quality Interventions for Reducing Respiratory Infections (study); max, maximum; med, median; min, minimum; , airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter (fine particulate matter); SD, standard deviation.

In general, demographic, household, and wood stove characteristics were evenly distributed across treatment arms (Table 1). However, the Filtration arm had fewer households with residents who smoked (13%) compared with the Control arm (20%) and the Education arm (18%). The Filtration arm also had more households with higher income (; 43%) compared with the Control arm (32%) and the Education arm (29%). Occasionally, participants declined to answer questions related to demographic or household characteristics. Although such instances were rare, missing sociodemographic data, as indicated in Tables 1 and 3, were generally evenly distributed across study arms.

Table 3.

Child characteristics and cases of LRTI among children from rural U.S. homes with wood stoves participating in the KidsAIR study, 2014–2020.

| Characteristics | All children () | Arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control () | Filter () | Education () | ||

| Child age at study start (y) [ (%)] | ||||

| 116 (25) | 38 (25) | 40 (25) | 38 (25) | |

| 1–4 | 344 (75) | 113 (75) | 116 (74) | 115 (74) |

| Missing | 1 () | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Child sex [ (%)] | ||||

| Female | 198 (43) | 64 (42) | 65 (41) | 70 (45) |

| Male | 237 (51) | 80 (53) | 81 (52) | 76 (49) |

| Missing | 26 (6) | 7 (5) | 11 (7) | 9 (6) |

| Child race [ (%)] | ||||

| AI/AN | 192 (42) | 61 (40) | 63 (40) | 68 (44) |

| White | 232 (50) | 81 (54) | 79 (50) | 72 (46) |

| More than 1 race | 32 (7) | 9 (6) | 12 (8) | 11 (7) |

| Missing | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Child ethnicity [ (%)] | ||||

| Hispanic | 14 (3) | 2 (1) | 7 (4) | 5 (3) |

| Not Hispanic | 441 (96) | 149 (99) | 146 (93) | 146 (94) |

| Missing | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Received influenza vaccine [ (%)] | ||||

| Yes | 193 (42) | 68 (45) | 61 (39) | 64 (42) |

| No | 240 (52) | 76 (50) | 83 (53) | 81 (53) |

| Missing | 28 (6) | 7 (5) | 12 (8) | 9 (6) |

| Total child-weeks of follow-up for all participants | 14,636 | 4,781 | 5,005 | 4,849 |

| Child-weeks at risk | ||||

| 461 | 151 | 156 | 154 | |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 21, 36, 41, 67 | 0, 22, 37, 41, 51 | 1, 20, 34, 41, 50 | 0, 23, 36, 40, 67 |

| Children with at least 1 LRTI (winter) [ (%)] | ||||

| 1 | 40 (9) | 15 (11) | 15 (10) | 10 (7) |

| 2 | 15 (4) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | 6 (5) |

| Total | 53 (12) | 17 (11) | 20 (13) | 16 (11) |

| Cases of LRTI per winter (winter) () | ||||

| 1 | 43 | 17 | 16 | 10 |

| 2 | 18 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 61 | 21 | 23 | 17 |

| Cases of LRTI per child (cases) [ (%)] | ||||

| 0 | 401 (88) | 131 (89) | 136 (87) | 134 (89) |

| 1 | 46 (10) | 13 (9) | 18 (12) | 15 (10) |

| 2 | 6 (1) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 1 () | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

Note: AI/AN, American Indian/Alaska Native; KidsAIR, Kids Air Quality Interventions for Reducing Respiratory Infections (study); LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; max, maximum; med, median; min, minimum; SD, standard deviation.

Indoor

A summary of household concentrations, household activity, ambient and temperature during indoor sampling, and filter unit compliance are displayed in Table 2. data from 36 households are missing owing to instrument malfunction during sampling () or households dropping from the study prior to sampling (). Instances of missing sampling data were similar across treatment arms, and there were similar numbers of households across treatment arms with sampling data (Table 2). The concentration measured over the 6-d sampling periods across all study households was , with a median of (range: 1.7–285.9). Control arm households had similar concentrations ( as Filtration arm households (, although Filtration arm households had slightly lower median concentrations than Control arm households (15.7, range: 1.9–235.0 vs. 19.0, range: 1.7–200.1, respectively). Education arm households had slightly higher () and median concentrations (20.6, range: 2.0–285.9) than Control arm households. The majority of caregivers reported that their wood stove burn level during sampling was similar to (51%) or less than (23%) what was typical during the wood stove heating season. Mean compliance based on percentage expected kilowatt hours from filter devices was 101% for Control and Filter arm households combined (), with lower values for Filter arm households (, ) compared with Control arm households (, ).

Table 2.

concentrations and household activity during 6-d indoor sampling events among rural U.S. homes with wood stoves participating in the KidsAIR study, 2014–2020.

| Variables | Total | Arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Filter | Education | ||

| Mean indoor concentration over sampling period () | ||||

| a | 266 | 92 | 86 | 88 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 2, 10, 19, 35, 286 | 2, 10, 19, 34, 200 | 2, 8, 16, 37, 235 | 2, 12, 21, 39, 286 |

| Mean indoor concentration when child was at home () | ||||

| b | 362 | 122 | 120 | 120 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 1, 9, 17, 34, 439 | 2, 10, 18, 31, 206 | 1, 8, 17, 29, 439 | 1, 10, 17, 36, 286 |

| Percentage of time child was at home during sampling period | ||||

| b | 383 | 128 | 126 | 129 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 15, 72, 84, 92, 100 | 15, 68, 83, 91, 100 | 28, 72, 84, 91, 100 | 16, 75, 85, 93, 100 |

| Mean ambient temperature during sampling period (degrees Celsius) | ||||

| a | 256 | 87 | 84 | 85 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | , , , 0, 16 | , , , 0, 12 | , , , 0, 15 | , , , , 16 |

| Mean ambient during indoor sampling period () | ||||

| a | 253 | 87 | 84 | 82 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 2, 3, 6, 15 | 0, 1, 3, 5, 14 | 0, 2, 3, 6, 15 | 0, 2, 3, 5, 15 |

| Days with self-reported smoking indoors during sampling period | ||||

| a | 256 | 85 | 86 | 85 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 0, 0, 0, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 0, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 0, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 0, 6 |

| Days with self-reported windows open during sampling period | ||||

| a | 256 | 85 | 86 | 85 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 0, 0, 2, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 3, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 1, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 3, 6 |

| Days with self-reported sweeping indoors during sampling period | ||||

| a | 257 | 86 | 86 | 85 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 2, 3, 5, 6 | 0, 2, 3, 5, 6 | 0, 2, 3, 5, 6 | 0, 1, 3, 6, 6 |

| Days with self-reported doors open during sampling period | ||||

| a | 256 | 85 | 86 | 85 |

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 0, 0, 0, 2, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 3, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 1, 6 | 0, 0, 0, 1, 6 |

| Compliance based on percentage expected kilowatt hours from filter devicec | ||||

| a | 162 | 78 | 84 | NA |

| NA | ||||

| Min, 25th percentile, med, 75th percentile, max | 1, 37, 75, 117, 964 | 1, 49, 99, 126, 965 | 3, 31, 56, 104, 538 | NA |

Note: KidsAIR, Kids Air Quality Interventions for Reducing Respiratory Infections (study); max, maximum; med, median; min, minimum; NA, not applicable; , airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter (fine particulate matter); SD, standard deviation.

of observations of 302 households (, , ).

of observations of 461 children (, , ).

Compliance assessed over entire Winter 1 study period.

Child Characteristics and LRTI Cases

Child characteristics and a description of LRTI cases are presented in Table 3. Of the 461 children in the study, 116 (25%) were year of age at the time the study began and 43% were female. The children had a similar distribution of race and ethnicity as the primary caregivers (Tables 1 and 3). Fifty-three of the 461 children in the study (11.5%) had at least 1 diagnosed LRTI. Of the 53 children who had an LRTI, 6 had two diagnosed cases of LRTI and 1 had three cases. Similar numbers of LRTI were diagnosed across treatment arms, with slightly lower LRTI cases in the Education arm (17) compared with the Filtration arm (23) and Control arm (21).

Primary Results

Primary model results are presented in Table 4. ITT-LRTI model results indicated that there were similar odds of children having at least one LRTI in the Filtration arm [; 95% CI: 0.46, 3.32] and Education arm (; 95% CI: 0.35, 2.72) compared with the Control arm. In the analysis, geometric mean concentrations were similar in the Filtration arm (6.96% lower; 95% CI: , 24.55) and Education arm (11.77% higher; 95% CI: , 49.72) compared with the Control arm. In the ER analysis, the odds of an LRTI diagnosis was 1.45 times higher (95% CI: 1.02, 2.05) per interquartile range (IQR: ) increase in 6-d mean indoor .

Table 4.

Primary analysis results.

| Model framework | OR or estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Intent-to-treat framework, LRTI outcomea | |

| Control () | Ref |

| Filter () | 1.23 (0.46, 3.32) |

| Education () | 0.98 (0.35, 2.72) |

| Intent-to-treat framework, outcome (data from Winter 1)b | |

| Control () | Ref |

| Filter () | (, 24.55) |

| Education () | 11.77 (, 49.72) |

| Exposure–response framework, LRTI outcomec | |

| IQR () increase in () | 1.45 (1.02, 2.05) |

Note: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; , airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter (fine particulate matter); Ref, reference.

Mixed effects logistic regression model with the presence of LRTI as outcome (yes or no); assigned treatment as primary exposure variable; adjusted for child age and person-time at-risk; nested random term was home:cohort:area. Results presented as ORs with 95% CIs.

Linear mixed model with natural-log transformed 6-d mean indoor as outcome; assigned treatment as primary exposure variable; adjusted for child age; nested random term was cohort:area. Results presented as effect estimates with 95% CIs and reported as percentage differences in geometric mean .

Mixed effects logistic regression model with the presence of LRTI as outcome (yes or no); 6-d mean as primary exposure variable; model adjusted for child age and sex, caregiver race and sex, household income, caregiver education, whether household resident smokes, ambient temperature and , and person-time at-risk; nested random term was home:cohort:area. Results presented as ORs per IQR () increase in with 95% CIs.

Results from analyses that assessed effect modification are presented in Table 5. In general, CIs were wide and largely overlapping in the ITT-LRTI and frameworks, with limited evidence to suggest that the effect of the treatment was modified by the variables we assessed. In the ER analysis framework, there was no evidence of effect modification by child age, sex, or smoking status of household members.

Table 5.

Results from analyses assessing effect modification.

| Categories | OR or estimate (95% CI) | -Value for interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Child age, ITT framework, LRTI outcome (y)a | 0.48 | |

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 2.64 (0.28, 24.80) | |

| Education () | 2.42 (0.25, 23.36) | |

| 1–4 | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 0.87 (0.19, 3.90) | |

| Education () | 0.63 (0.13, 3.05) | |

| Child sex, ITT framework, LRTI outcomea | 0.22 | |

| Female | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 0.78 (0.06, 9.87) | |

| Education () | 0.12 (0.01, 2.82) | |

| Male | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 0.71 (0.05, 9.68) | |

| Education () | 1.42 (0.11, 18.42) | |

| Household smoking, ITT framework, LRTI outcomea | 0.61 | |

| Resident smokes (yes) | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 0.86 (0.06, 12.06) | |

| Education () | 1.70 (0.14, 20.89) | |

| Resident smokes (no) | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 1.25 (0.31, 5.12) | |

| Education () | 0.71 (0.16, 3.22) | |

| Study area, ITT framework, outcomeb | 0.63 | |

| Alaska | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 210.8) | |

| Education () | (, 80.1) | |

| Navajo Nation | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 11.0 (, 122.6) | |

| Education () | 13.4 (, 138.6) | |

| Western Montana | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 42.4) | |

| Education () | 24.7 (, 94.0) | |

| Home area, ITT framework, outcome ()b | 0.20 | |

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 21.9 (, 111.3) | |

| Education () | (, 60.1) | |

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 50.6) | |

| Education () | 22.7 (, 112.3) | |

| Household smoking, ITT framework, outcomeb | 0.52 | |

| Resident smokes (yes) | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 126.7) | |

| Education () | 38.7 (, 213.6) | |

| Resident smokes (no) | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 10.8 (, 65.6) | |

| Education () | 7.5 (, 62.1) | |

| Wood stove burn level relative to typical winter burning, ITT framework, outcomeb | 0.76 | |

| None/light | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 65.5) | |

| Education () | 5.9 (, 117.1) | |

| Average | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 57.0) | |

| Education () | 26.7 (, 103.5) | |

| Heavy | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 131.8) | |

| Education () | (, 106.8) | |

| Wood stove age, ITT framework, outcome (y)b | 0.25 | |

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 73.4) | |

| Education () | 34.4 (, 143.2) | |

| 6–15 | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 7.7 (, 93.0) | |

| Education () | (, 45.3) | |

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 1.9 (, 105.3) | |

| Education () | 69.1 (, 232.4) | |

| Wood stove grade, ITT framework, outcomeb | 0.22 | |

| High quality | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 8.2 (, 316.6) | |

| Education () | 38.8 (, 367.6) | |

| Medium quality | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | (, 27.7) | |

| Education () | 8.8 (, 77.1) | |

| Low quality | ||

| Control () | Ref | |

| Filter () | 73.6 (, 264.2) | |

| Education () | 14.0 (, 145.9) | |

| Child age, exposure–response framework, LRTI outcome (y)c | 0.77 | |

| () | 1.66 (0.63, 4.33) | |

| 1–4 () | 1.44 (0.90, 2.31) | |

| Child sex, exposure–response framework, LRTI outcomec | 0.64 | |

| Female () | 1.36 (0.84, 2.22) | |

| Male () | 1.59 (0.98, 2.59) | |

| Household smoking, exposure–response framework, LRTI outcomec | 0.44 | |

| Resident smokes (yes) () | 1.99 (0.82, 4.83) | |

| Resident smokes (no) () | 1.34 (0.89, 2.03) | |

Note: Significance of the interaction terms (-value) assessed using type II Wald chi-square tests. CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intent-to-treat; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; , airborne particles in aerodynamic diameter (fine particulate matter); Ref, reference.

Mixed effects logistic regression model with the presence of LRTI as outcome (yes or no); assigned treatment as primary exposure variable; adjusted for child age and person-time at-risk; nested random term was home:cohort:area. Results presented as ORs with 95% CIs.

Linear mixed model with natural-log transformed 6-d mean indoor as outcome; assigned treatment as primary exposure variable; adjusted for child age; nested random term was cohort:area. Results presented as effect estimates with 95% CIs and reported as percentage differences in geometric mean .

Mixed effects logistic regression model with the presence of LRTI as outcome (yes or no); 6-d mean as primary exposure variable; model adjusted for child age and sex, caregiver race and sex, household income, caregiver education, whether household resident smokes, ambient temperature and , and person-time at-risk; nested random term was home:cohort:area. Results presented as ORs per IQR () increase in with 95% CIs.

Sensitivity Analyses

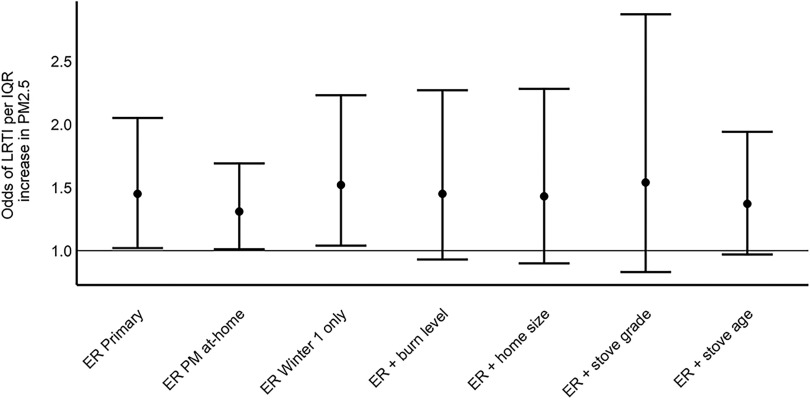

Sensitivity analyses for the ITT-LRTI and frameworks are presented in Figures S2 and S3. In general, sensitivity analyses that included other potential confounders did not meaningfully change the model results in any of the analysis frameworks and CIs were wider than in the primary analysis results. The exception to this was the ITT-LRTI model that included caregiver-reported influenza vaccination status (yes or no) as a covariate. Although CIs were very wide, ORs were somewhat lower in this model compared with the primary model without vaccination status (Figure S2). There were also small differences in ITT-LRTI results from sensitivity analyses conducted with subsets of the data compared with the primary results. When data from the AK study area were excluded (owing to the different control treatment with no filtration unit), children had slightly higher odds of LRTI compared with the primary analysis, although CIs were very wide as a result of the reduced number of observations in the analysis (Figure S2). In the same sensitivity analysis with as the outcome, results were very similar to the primary results (Figure S3). When the ITT-LRTI data set was restricted to Winter 1 only, ORs were slightly lower than the primary analysis that included data from both winters of observation (Figure S2). The ER results were not meaningfully changed when restricting analyses to times when the child was home, when using data from the first winter only, nor when adding additional variables to the primary analysis such as burn level, home size, or stove quality (Figure 2). The post hoc analyses that assessed different model variations did not meaningfully impact results (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Exposure–response analysis framework results from the primary model and sensitivity analyses. ER Primary (): mixed effects logistic regression model with the presence of LRTI as outcome (yes or no); 6-d mean as primary exposure variable; model adjusted for child age and sex, caregiver race and sex, household income, caregiver education, whether household resident smokes, ambient temperature and , and person-time at-risk; nested random term was home:cohort:area. Results presented as ORs per IQR () increase in with 95% CIs. ER PM at-home (): primary model using PM from when the child was at home. ER Winter 1 only (): primary model using data only from Winter 1. level (): primary model plus self-reported burn level compared with typical stove use during winter. size (): primary model plus home size (in square meters). grade (): primary model plus stove grade. age (): primary model plus caregiver-reported stove age. Note: CI, confidence interval; ER, exposure–response analysis framework; IQR, interquartile range; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; OR, odds ratio; PM, airborne particles; , particulate matter in aerodynamic diameter (fine particulate matter).

Discussion

We have reported results from a randomized intervention trial aimed at lowering indoor concentrations and incidence of LRTI among children living in rural U.S. homes with residential wood stoves. Across all study households, we measured 6-d indoor concentrations of , with a median of (range: 1.7–285.9). In the ITT analysis with LRTI as the outcome, we report ORs of 1.23 (95% CI: 0.46, 3.32) for the Filtration arm and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.35, 2.72) for the Education arm compared with control. In the ITT analysis with as the outcome, geometric mean was 6.96% lower (95% CI: , 24.55) in the Filtration arm and 11.77% higher (95% CI: , 49.72) in the Education arm compared with control. If focused on the point estimates, these results seem counterintuitive. The filtration treatment slightly lowered indoor , yet children had higher odds of LRTI in the Filtration arm. The education treatment slightly increased indoor and had no impact on LRTI. Overall, however, the magnitude of these changes for both LRTI and are small, with very wide CIs. As such, we are careful not to overinterpret these results from the ITT analysis, which largely indicate that neither the air filtration intervention nor the education intervention substantially reduced indoor in study households or LRTI in study children relative to the Control arm. In the ER analysis, outside the context of the randomized intervention assignment, we found evidence that a increase in 6-d mean indoor concentrations was associated with the presence of LRTI (; 95% CI: 1.02, 2.05). Our findings, although subject to limitations, are important contributions to the literature surrounding indoor biomass air pollution and childhood LRTI.

Other studies with designs similar to ours have assessed the impact of improved biomass stove interventions on indoor air pollution and respiratory infection among children in lower- and middle-income countries. Our study is the first (that we are aware of) to test interventions aimed at reducing indoor and improving child LRTI among rural U.S. homes with residential wood stoves. The Randomised Exposure Study of Pollution Indoors and Respiratory Effects (RESPIRE) study in Guatemala reported 50% lower personal carbon monoxide (CO) exposures (1.1 vs. ) and 22% lower physician-diagnosed pneumonia (; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.06) among children from households that received a wood stove with a chimney compared with control households that used open indoor wood fires for cooking (Smith et al. 2011). An improved cookstove intervention study in Malawi called the Cooking and Pneumonia Study (CAPS) found no difference in cases of pneumonia among young children in the intervention arm compared with the control arm of the study, although intervention compliance and sustained use in the study may have been limited by intervention cookstove malfunction (Mortimer et al. 2017). The CAPS study also reported no meaningful differences in personal CO exposures in the intervention vs. control arms of the study (Mortimer et al. 2020).

Although there is evidence of associations between indoor biomass air pollution and respiratory infection in children, nearly all of the previous studies that have reported associations have used proxies of exposure such as fuel or stove type (Adaji et al. 2019; Balmes 2019; Guercio et al. 2021; Rokoff et al. 2017). The RESPIRE study found that a 50% reduction in mean CO exposure was associated with a relative risk of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.70, 0.98) for physician-diagnosed pneumonia (Smith et al. 2011). The Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS) reported associations between prenatal and postnatal CO exposure (from cookstoves) and physician-diagnosed pneumonia (Kinney et al. 2021). Risk for pneumonia increased by 10% (; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.16) per increase in average prenatal CO exposure and by 6% (; 95% CI: 0.99, 1.13) per increase in average postnatal CO exposure (Kinney et al. 2021). Our study is among the first to report an association between measured indoor biomass air pollution exposures and childhood LRTI. Other studies have reported stronger associations (i.e., higher ORs) between biomass fuel use and childhood LRTI (Adaji et al. 2019; Bruce et al. 2015; Guercio et al. 2021; Rokoff et al. 2017), although differences in study design and fuel types may contribute to these varying associations. In addition, many previous studies of indoor biomass fuel use and childhood LRTI have assessed cookstoves used in lower- and middle-income countries, which can produce mean indoor concentrations one to two orders of magnitude higher than what we measured in the KidsAIR study households (Clark et al. 2013; Guercio et al. 2021). Our results suggest that elevated indoor , even at lower levels, is still associated with adverse respiratory outcomes in children. Although toxicological evidence is limited for biomass air pollution exposures compared with tobacco smoke and other ambient air pollution sources, there is strong evidence that inhaled particles initiate oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways that can lead to epithelial cellular injury and the increased risk of respiratory tract infection (Balmes 2019; Gordon et al. 2014).

Although air filtration units have successfully reduced indoor air pollution in a number of studies (Cheek et al. 2021), few of these studies have taken place in homes with indoor sources of biomass air pollution from wood heating stoves. Robust indoor air pollution sampling in two Montana homes with wood stoves showed reduction in concentrations of 61–84% during periods with a portable air filtration unit compared with periods with no air filtration (Hart et al. 2011). Although the sample size of homes was small, the results of this study (Hart et al. 2011) demonstrate the effectiveness of air filtration units at reducing indoor under ideal scenarios. The Asthma Randomized Trial of Indoor Wood Smoke (ARTIS) study in rural U.S. regions reported 66% lower geometric mean concentrations (95% CI: , ) in wood stove homes that used air filtration units compared with control homes (Ward et al. 2017). Similar reductions in indoor have been reported in wood stove households in Canada following air filtration interventions compared with control (Allen et al. 2011; Wheeler et al. 2014). In contrast, our results from the KidsAIR study show a difference in indoor of only 7% (95% CI: , 25) in Filtration arm households compared with control. The studies by Allen et al. (2011) and Wheeler et al. (2014) were both short-term studies that assessed within-home differences in with and without an air filtration device using randomized crossover designs. In contrast, the KidsAIR study had a longer duration and assessed intervention efficacy among different households across study arms. The ARTIS study had a longer duration that was more similar to the KidsAIR study; however, homes in the ARTIS study all had older model stoves, household residents did not use tobacco products, and the air filtration intervention included two units (i.e., one in the wood stove room and a smaller one in the child’s bedroom). In contrast, the KidsAIR study included homes with a wider range of stove models, did not exclude participation based on tobacco use, and the Filtration arm included one air filtration unit in the wood stove room only. In addition, ARTIS had baseline winter (i.e., preintervention winter) measurements, and the outcome of interest was change in from the preintervention to intervention winter, whereas the KidsAIR study was a post-only study. This likely is a key difference in the design of the two studies given the wide variability in baseline between treatment arms observed in ARTIS. Specifically, baseline median was 17, 41, and in filter, wood stove changeout, and placebo arms, respectively (Ward et al. 2017). It is possible that such differences in the study designs, duration, and inclusion/exclusion criteria led to the different findings in reduction from air filtration units for the KidsAIR study compared with previous studies.

Regarding the Education arm of the KidsAIR study, although there is some evidence that educational strategies can improve indoor air pollution in wood-burning homes (Hine et al. 2011; Ward et al. 2011), our results suggest that the educational intervention alone was not efficacious in reducing indoor across all study households. There is some evidence that the effect of the education intervention on was modified by size of the homes (Table 5). Larger homes may have required more frequent wood stove use, reducing the impact of the educational interventions aimed at improving burn efficiency. Such explanations are speculative, and our results largely indicate that the educational interventions did not meaningfully impact indoor . More comprehensive educational strategies or further educational reinforcement and follow-up may be more effective in future studies.

The study results may have been impacted by other factors, such as intervention compliance, confounding, or loss to follow-up. Low compliance in the Filtration arm of the study could have impacted the study findings and led to concentrations in Filtration arm homes that were similar to the Control arm homes. We assessed percentage expected kilowatt hours of electricity used by the filter devices compared with laboratory tests as a measure of compliance. Using this measure, mean percentage expected kilowatt hours was 82% (; Table 2), suggesting there was some lack of compliance. We did not observe a decrease in indoor concentrations as compliance (based on quartiles of percentage expected kilowatt usage by the filter devices) increased (Table S1). This is consistent with an earlier study by our group that suggested reductions are fairly constant despite variations in compliance (Ward et al. 2017). For the educational intervention, it is possible that participants did not consistently use the hands-on educational practices, although this is not what was indicated in self-reported post-winter questionnaires (Table S2). A majority of participants reported that they used the wood stove thermometers and fire starters daily. Although the wood moisture meters were used less frequently, participants reported that they generally found all of the educational strategies at least somewhat helpful. Unmeasured confounding could have impacted our study results, although the randomized design should have limited confounding in the ITT analyses. The relatively even distribution of variables across intervention arms (Tables 1 and 3), and the minimal impact on model results with the inclusion of potential confounders (Figures S1 and S2), suggest that the impact of confounding was minimal in the ITT analyses. Although we recruited participants from three distinct study areas across rural U.S. regions, our results may not be generalizable to other population subsets with different demographic, household, and wood stove use characteristics.

Regarding the three study areas, it is also possible that including participants from these distinct regions could have impacted study results. In particular, the AK study area received a different control treatment (no filtration unit) than the NN and WMT study areas (sham filtration unit). In sensitivity analyses, however, we did not find differences in the results across study areas. Removing the AK study households from the ITT analyses did not meaningfully impact the LRTI results (Figures S1 and S2). We also did not observe evidence of effect modification by study area on the impact of the treatments on , although the power to detect such interactions was limited (Table 5).

Losses to follow-up are a concern in prospective studies with high participant involvement such as ours. A number of homes dropped from our study following randomization and prior to the start of Winter 1 data collection () as well as between Winter 1 and Winter 2 data collection (). Of the homes lost to follow-up, nearly half dropped because the families moved (45%), 24% dropped because of lost contact with the primary caregiver, and another 24% dropped because they declined for various reasons ranging from family emergencies to busy schedules. Six of the homes that dropped no longer met eligibility criteria to participate—typically because the wood stove was replaced in the home. Although we cannot be sure that losses to follow-up did not result in a selection bias, the homes that dropped from the study were evenly distributed across treatment arms (Figure 1). As such, the losses to follow-up may have reduced the statistical power of the study but likely did not produce a systematic bias related to treatment arm that could have impacted results. In addition, retention was very good through the first year of the study, with 87% of randomized households having data for Winter 1. Although retention fell after the first year (69% of randomized households had data for both winters), overall conclusions were similar in sensitivity analyses restricted to Winter 1 of follow-up, when retention was high (Figure S2).

Our method for prospectively tracking LRTI events and confirming the diagnoses via medical records was a strength of the KidsAIR study that likely led to highly specific results (i.e., few false-positive LRTI cases). However, we also recognize that these diagnoses are made on a clinical basis rather than a discrete, objective finding. Objective measures such as chest radiographs, blood cultures, or viral detection methods are not routinely done as standard of care. In addition, very few diagnoses of LRTI were made solely based on fieldworker reported signs and symptoms given that medical records were the main source of clinical information. Accordingly, we used objective signs (e.g., pulse oximetry, documented fever, cough) to support diagnoses rather than simply using caregiver-reported symptoms. Although such specific diagnostic methods are important for case determination, they may have led to lower sensitivity (i.e., more false negatives), with the potential that we missed cases of LRTI that were not confirmed by medical record or objective signs. Although we do not believe that the LRTI diagnostic methods were different across study arms and potentially biased the results, the specific nature of the case diagnoses may have led to lower statistical power by identifying fewer LRTI cases than actually occurred. Approximately 12% of the children in the KidsAIR study had at least one LRTI over both winters of follow-up, which is less than half of what was anticipated (Noonan et al. 2020). Future analyses will assess the impact of using less specific LRTI case diagnostic criteria on the study results.

Our study relied on a single 6-d assessment of indoor sampling during the first winter of participation to characterize exposure to wood stove air pollution. There are a number of weaknesses to such measurements, including the equipment used for sampling. Light-scattering aerosol monitors without built-in drying features (such as the DustTrak used in our study) can be impacted by changes in relative humidity, where higher humidity levels can result in erroneously high readings of particle count and concentration (Jayaratne et al. 2018). However, when compared with reference instruments that include built-in dryers/heaters to keep humidity consistent during sampling, deviations typically occur at high humidity levels of or greater (Holder et al. 2020; Jayaratne et al. 2018; Tryner et al. 2020). We reported in a previous publication that maximum indoor humidity during sampling was among study households on average (Walker et al. 2021). It is possible that meteorological conditions impacted our measurements, and our inability to adjust for such factors is a limitation in the study. However, we believe that relative humidity had a minimal impact on the study results. Another consideration from our sampling methods is that area samples of collected near the wood stove may not accurately represent personal exposures. Personal exposures are difficult to measure in infants and children; however, we did have caregivers record when children were at home during the sampling period. We matched these records with the real-time measurements to calculate mean concentrations during the periods when children were inside the home, and analyses with this measurement had similar results as primary analyses with overall mean indoor (Figures 2 and S3). Concentrations of also may not reflect overall exposure to indoor biomass air pollution, which contains thousands of pollutants that vary by stove use and fuel type (Naeher et al. 2007). In addition, a single 6-d sampling period over the 2-y study may not reflect typical exposure to wood stove air pollution. However, we asked participants to self-report their level of wood burning during the sampling period compared with what is typical throughout the wood-burning season to give the measured concentrations context. Nearly 75% of the caregivers reported that wood burning during the sampling period was similar to or less than normal during a typical wood stove heating season, indicating that households likely had elevated concentrations for extended periods during the winter months. We previously reported that mean indoor concentrations in KidsAIR Control homes exceeded the annual National Ambient Air Quality Standard for set by the U.S. EPA () in 70% of households, with 23% of households exceeding the 24-h standard of (Walker et al. 2021). Indoor concentrations in KidsAIR homes were also highly variable, with mean concentrations ranging between 2 and in all three study arms (Table 2). Overall, we captured robust measures of indoor that highlight the high variability and complex nature of indoor air pollution among wood stove households (Tables 2 and S1).

In conclusion, although we did not observe meaningful reductions in indoor or childhood LRTI in our study due to the education or air filtration treatments, our results highlight the importance of reducing indoor air pollution exposures in households with wood heating stoves. The associations we have reported between 6-d mean indoor concentrations and childhood LRTI are an important contribution to the literature on biomass air pollution; these findings provide further evidence of the potential effect of biomass air pollution exposures on childhood LRTI. Further assessment of novel intervention strategies is needed in order to meaningfully improve indoor air pollution exposures and health outcomes in wood stove households, particularly among homes with vulnerable populations such as children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.W.N. and T.J.W. were the co-principal investigators and co-coordinators of the study. E.S.W. conducted statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. J.G. contributed to the statistical methods. C.W.N., T.J.W., E.O.S., D.W., and E.W. contributed to the study concept and design, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript. P.G.S. and E.E. contributed to the lower respiratory tract infection tracking protocol and provided medical record reviews. E.W. trained field technicians and coordinated field work for the Western Montana study area. E.E. and J.L.L. oversaw the Navajo Nation component of the study, providing staffing management and oversight, interface and regular briefings with communities and hospital staff, and compliance reporting to the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. B.B.B. and S.E.H. oversaw the activities and reporting to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation (YKHC). All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript to its final version.

We thank the many families that chose to participate in the KidsAIR study. The project also benefited from the strong support of community members, Tribal leadership, local research assistants from all study locations, M. Kindred, J. Klejka, C. Hester, K. Conway, K. Lutz, B. Smith, J. Watson, J. Yazzie, D. Tsinnijinnie, M. Begay, M. Benally, and K. Henry.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS; 1R01ES022649 to C.W.N.). Development of the educational intervention was also supported by the NIEHS (1R01ES022583 to C.W.N.). Additional support was provided by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes IDeA States Pediatric Clinical Trials Network (8UG1OD024952 to P.G.S.) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1P20GM130418 to C.W.N.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- Adaji EE, Ekezie W, Clifford M, Phalkey R. 2019. Understanding the effect of indoor air pollution on pneumonia in children under 5 in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of evidence. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 26(4):3208–3225, PMID: , 10.1007/s11356-018-3769-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RW, Carlsten C, Karlen B, Leckie S, van Eeden S, Vedal S, et al. 2011. An air filter intervention study of endothelial function among healthy adults in a woodsmoke-impacted community. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183(9):1222–1230, PMID: , 10.1164/rccm.201010-1572OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RW, Leckie S, Millar G, Brauer M. 2009. The impact of wood stove technology upgrades on indoor residential air quality. Atmos Environ 43(37):5908–5915, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balmes JR. 2019. Household air pollution from domestic combustion of solid fuels and health. J Allergy Clin Immunol 143(6):1979–1987, PMID: , 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48, 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateson TF, Schwartz J. 2008. Children’s response to air pollutants. J Toxicol Environ Health A 71(3):238–243, PMID: , 10.1080/15287390701598234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Pope D, Rehfuess E, Balakrishnan K, Adair-Rohani H, Dora C. 2015. WHO indoor air quality guidelines on household fuel combustion: strategy implications of new evidence on interventions and exposure–risk functions. Atmos Environ 106:451–457, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.08.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, Weber M, Arana B, Diaz A, Jenny A, Thompson L, et al. 2007. Pneumonia case-finding in the RESPIRE Guatemala indoor air pollution trial: standardizing methods for resource-poor settings. Bull World Health Organ 85(7):535–544, PMID: , 10.2471/BLT.06.035832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek E, Guercio V, Shrubsole C, Dimitroulopoulou S. 2021. Portable air purification: review of impacts on indoor air quality and health. Sci Total Environ 766:142585, PMID: , 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, et al. 2013. Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment. Environ Health Perspect 121(10):1120–1128, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1206429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T, Checkley W, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, McCracken JP, Rosa G, et al. 2020. Design and rationale of the HAPIN study: a multicountry randomized controlled trial to assess the effect of liquefied petroleum gas stove and continuous fuel distribution. Environ Health Perspect 128(4):047008, PMID: , 10.1289/EHP6407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EIA (U.S. Energy Information Agency). 2015. Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS). 2015 RECS survey data. https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/ [accessed 17 February 2021].

- Foote EM, Singleton RJ, Holman RC, Seeman SM, Steiner CA, Bartholomew M, et al. 2015. Lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations among American Indian/Alaska Native children and the general United States child population. Int J Circumpolar Health 74:29256, PMID: , 10.3402/ijch.v74.29256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KBH, et al. 2014. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med 2(10):823–860, PMID: , 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guercio V, Pojum IC, Leonardi GS, Shrubsole C, Gowers AM, Dimitroulopoulou S, et al. 2021. Exposure to indoor and outdoor air pollution from solid fuel combustion and respiratory outcomes in children in developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 755(pt 1):142187, PMID: , 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]