Abstract

The Paramyxoviridae family includes enveloped single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses such as measles, mumps, human parainfluenza, canine distemper, Hendra, and Nipah viruses, which cause a tremendous global health burden. The ability of paramyxoviral glycoproteins to merge viral and host membranes allows entry of the viral genome into host cells, as well as cell–cell fusion, an important contributor to disease progression. Recent molecular and structural advances in our understanding of the paramyxovirus membrane fusion machinery gave rise to various therapeutic approaches aiming at inhibiting viral infection, spread, and cytopathic effects. These therapeutic approaches include peptide mimics, antibodies, and small molecule inhibitors with various levels of success at inhibiting viral entry, increasing the potential of effective antiviral therapeutic development.

Introduction

The Paramyxoviridae family possesses some of the most infectious and lethal of the enveloped viruses, and although vaccines for a select few paramyxoviruses are available, outbreaks in unvaccinated and vaccinated individuals have increased. For example, measles (MeV) and mumps (MuV) viruses continue to pose a threat to public health, specifically in young children, despite the availability of a vaccine [1,2]. MeV in the genus Morbillivirus causes over 110 000 MeV cases per year [3,4]. The number of outbreaks due to MuV and MeV has also increased due to subpar vaccines, the waning of vaccine-induced immunity, and individuals choosing not to vaccinate themselves or their children [5,6]. Another Morbillivirus for which there is a vaccine and is of great veterinary concern is canine distemper virus (CDV), which causes a major health burden to a wide range of wildlife including dogs, lions, seals, and non-human primates [7-10]. Further, MuV in the genus Rubulavirus has had an increasing number of outbreaks since the early 2000s in both vaccinated and unvaccinated populations [11].

Additionally, there is the threat of emerging paramyxoviruses, for which there are no approved human treatments or vaccines, thus requiring urgent research and development. Such is the case of the deadly Henipaviruses (HNV), with many outbreaks in the past two decades. The initial Nipah virus (NiV) outbreak occurred in December 1998 in Malaysia, and had a mortality rate of ~40%, killing 105 of the 265 infected individuals [12,13]. Since then, there have been nearly annual outbreaks of NiV in Bangladesh [14-16]. Recently, NiV has been reported to have a mortality rate ranging from 40 to 100% depending on the outbreak [17,18,19•]. For example, NiV claimed 21 of the 23 infected individuals during the 2018 outbreak in Kerala, India [20•]. There are experimental treatments for NiV authorized for use during outbreaks. For example, ribavirin, a purine nucleoside analog capable of inhibiting viral RNA polymerases was used to treat NiV encephalitis during the 1998 and 2018 outbreaks. Ribavirin was used as a post-exposure prophylactic that reportedly successfully protected health care workers from contracting NiV [21,22,23•]. The related HNVs, Hendra (HeV) and Mojiang virus, have also claimed several human lives [24-28]. Notably, the major host reservoir for the HNVs is the Pteropus genus of fruit bats which have a large geographic distribution worldwide from Australia, Southern Asia, and Africa [29,30]. This has likely led to increasing spillover events as human activity pushes into the fruit bat territory [31]. There are recent reports of seropositive bats in Brazil, underscoring the growing threat that HNVs pose to global public health [31,32].

MeV and MuV vaccines are archetypes for successful vaccine implementation and disease prevention. Nevertheless, many paramyxoviruses have no approved vaccines, leaving humans and livestock vulnerable [33]. Though there are several means of viral entry, regardless of the specific mechanims, a form of membrane-membrane fusion seems to be the common process by which most enveloped viruses enter naïve cells. Therefore, the development of antivirals targeting paramyxovirus entry is critical. Major hurdles in developing antivirals targeting paramyxoviral entry are the virus’ ability to mutate and the persistent emergence of novel strains. With improved vaccination strategies and effective antivirals, it may be possible that some paramyxoviruses will join smallpox and rinderpest (RPV) on the list of eradicated viruses [34,35].

Herein we review the major themes that have surfaced in the development of paramyxovirus fusion inhibitors. Including peptide, antibody, and small molecule approaches, which seek to interfere with crucial steps of the fusion process from initial receptor binding events to intermediate events in the membrane fusion and viral entry processes.

Paramyxovirus fusion

Paramyxoviruses require specific receptors on target cells for viral binding and entry to occur. Morbilliviruses such as measles, canine distemper, and peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV) commonly use signaling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) and nectin-4 receptors for entry into epithelial tissue [36-38]. The HNVs such as Ghana (GhV), NiV, HeV, and Cedar virus (CeV) can all utilize ephrinB2 and ephrinB3 as entry receptors, however, CeV can also use class A ephrins [39-45,46••,47•], and the receptor for Mojiang virus (MojV) is still unknown. Heparan sulfate has also been reported to function as an attachment factor that aids in the initial interactions of HNV glycoproteins to the target cell [48]. In the Avulavirus, Respirovirus, and Rubulavirus genera the HN glycoproteins require sialic acid-containing proteins as receptors for binding and entry, with sialic acid acting as the receptor [49-54].

Paramyxovirus fusion is coordinated by the action of two membrane glycoproteins, the receptor-binding protein (RBP) or attachment (G, H, HN) and fusion (F) glycoproteins. The RBPs are type II transmembrane (TM) proteins that form tetramers as dimers of dimers [55,56] and bind the host receptor initiating the fusion cascade by triggering the fusion glycoprotein (F) [57-61].

The trimeric paramyxovirus F glycoprotein is a type I TM protein and a class I fusion protein. The precursor F0 protein must be proteolytically cleaved for F to be fusogenically active. HNV fusion proteins are not proteolytically cleaved as they are trafficked through the secretory pathway, and must be endocytosed to be fusogenically active [62]. HNV F0 is endocytosed by Rab5-positive early endosomes to endosomal compartments, where F0 is cleaved by cathepsin B/L or furin proteases and is then transported to the cell surface [63-67]. Fusogenically active F is composed of F1 and F2 subunits linked by a disulfide bond [68]. The F of MeV, HPIV3, and Simian virus 5 (SV5) is proteolytically cleaved in the trans-Golgi network by furin [69,70•,71]. The fusion proteins of Human metapneumovirus (HMPV), a former member of the Paramyxoviridae family now in the Pneumoviridae family, and Sendai virus (SeV) are matured into their fusogenically active form by extracellular proteases [72,73].

The structural core of F contains the heptad repeat (HR) regions HR1/A and HR2/B [74-76]. HR1/A is adjacent to the fusion peptide and HR2/B is located near the TM domain. The F2 subunit of F possesses the fusion peptide and the HR3 domain. HR1/A aids in the stabilization of the metastable prefusion state of F, the helical structure of the F-trimer [77,78]. HR1 transitions into an elongated helix, which develops into a trimeric coiled-coil stalk, causing F to be harpooned into the target membrane forming the pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI). Then membrane fusion occurs when HR1/A and HR2/B regions fold together to form a six-helix bundle (6HB). This action facilitates the merging of the viral and cellular membranes [79,80].

Paramyxoviral fusion begins when the RBP binds to its host receptor and undergoes conformational changes that trigger F to go from the pre-fusion state to the pre-hairpin intermediate (PHI) [81,82]. Such is in the case for Nipah fusion, where G interacts with F by both the stalk and globular head in a bidentate interaction [83]. Triggered F transitions from the pre-fusion to the PHI to the 6-helix bundle conformations, and the latter transition is thought to merge the cellular and virus membranes, allowing for the viral genome to enter the cell to begin the infection, or allowing cell-cell fusion during syncytia formation [84]. After F triggering, F and G are thought to dissociate, however, the mechanism(s) for this event is unknown. Additionally, it has been shown for HeV that F requires dissociation of the TM domain for fusion to proceed [85••]. In summary, paramyxoviral membrane fusion occurs primarily at the plasma membrane and is a pH-independent process requiring the presence of F and the RBP on the effector viral or cellular membrane, and a receptor on the target membrane to initiate the fusion cascade [86,87]. Cell-cell fusion (syncytium formation) occurs when F and RBP are expressed on the surface of an infected cell and interact with the host receptor on an adjacent cell. The formation of giant multi-nucleated cells is a hallmark of paramyxoviral fusion. This is thought by many as a form of viral genome transmission free of viral particles [42,88-90].

Currently, there are five models of F triggering ranging from G promptly dissociating from F after receptor binding, to high-order oligomerization of F with G after receptor binding [80]. Furthermore, the minimal and maximal ratios of F to G necessary to execute paramyxoviral membrane fusion are unknown. However, a recent study by Xu et al. suggests that a greater proportion of NiV F hexamers may be optimal for NiV membrane fusion [91].

Paramyxovirus pathology

Paramyxovirus infections can elicit a wide range of symptoms. Newcastle disease virus (NDV), also known as avian paramyxovirus 1, in the genus Avulavirus, presents clinical signs in birds including diarrhea, lesions in the brain, kidney, and pancreas, head tremors, and ataxia [92]. NDV has been responsible for significant economic loss in the poultry industry [93].

HNV infections severely affect the central nervous system. Humans infected with NiV developed endothelial syncytium formation, vasculitis, and thrombosis [94]. Pigs are susceptible to NiV infection and display respiratory distress that is accompanied by a ‘barking-cough’ [95]. However, pigs are not as severely infected with NiV as humans, though pigs can spread the virus easily amongst themselves. During the 1998 outbreak, over a million pigs were culled to stop the spread of NiV [18,96]. HeV, closely related to NiV, is deadly to both horses and humans. The initial HeV outbreak occurred in 1994 in Queensland, Australia and resulted in the death of two humans and 14 horses. The first human fatality suffered from respiratory hemorrhaging and edema associated with syncytia formation in the lungs, in addition to headaches, sore throat, a stiff neck, vomiting, and seizures, before succumbing to the infection. The second fatality from HeV was an individual that had contracted HeV a year earlier. Giant-multinucleated cells were found in the viscera and brain of this individual at autopsy [97,98].

HPIV infections are usually self-limited and cause bronchiolitis, croup, and pneumonia in children. HPIV 1–3 are responsible for a high mortality rate in immunocompromised adults and young children [99-101]. In the U.S., HPIV related pneumonia was responsible for an annual 10 100 hospitalizations in children younger than five years old [102]. MuV causes painful swelling of the parotid gland, scrotum in males, and breasts in females. Individ-uals infected with MuV also experience nausea, vomiting, headaches, and fever [103]. MuV can also cause a reduction in testes size and infertility in men and premature menopause and infertility in women. However, cases of infertility due to MuV are rare [104,105••,106].

In the Morbillivirus genus, MeV and its persistent cell–cell only variant, Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), can cause life-threatening infections in young children. Following the initial MeV infection, after six years on average, when SSPE develops it causes demyelination within the central nervous system, leading to increasingly severe neurological degeneration culminating in death within four years [107,108]. Additionally, MeV elicits acute immune suppression by infecting memory B, T, and plasma cells, virtually eliminating the antibody repertoire against other pathogens [109•]. Clinical signs of CDV infections are diarrhea, vomiting, respiratory distress, and neurological symptoms, including ataxia and convulsions [110]. CDV infection in the CNS can cause demyelination in the white matter and syncytium formation, leading to neuropathology [111-113]. Feline morbillivirus is a newly emerging virus thought to cause chronic kidney disease and tubular intestinal nephritis in cats [114,115•]. Further, atlantic salmon can be infected by Atlantic salmon paramyxovirus from the Aquaparamyxovirus genus. Infection in the gills induces respiratory distress and a 40% mortality rate in salmon farms [116]. Peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV), a highly contagious Morbillivirus that commonly infects goats and sheep, causing necrotic lesions in epithelial cells and lymphoid tissue [117]. PPRV also causes fever, ocular, and nasal discharge, and has a mortality rate of 70–80% in infected ruminants [118].

Fusion protein peptide antivirals

Paramyxoviral fusion inhibitor peptides target-specific regions of F to arrest membrane fusion. Most of the inhibitory peptides are sequences derived from the HR regions, however, the TM domain and the leucine zipper regions have also been targeted. Most peptide-based inhibitors are mimics of the heptad repeat regions of the fusion protein, which upon binding prevent the formation of the six-helix bundle (6HB) and arrest fusion at an intermediate step. This is the mechanism of action for the class I fusion peptide enfuvirtide which is a 36 amino acid (aa) peptide of the gp41 HR2 domain that inhibits HIV entry. However, native sequence-based peptides have not proven sufficient to successfully inhibit in vivo, prompting further enhancement of inhibitory activity by altering the peptide sequence. These peptide mimics have been remarkably effective as inhibitors of viral entry in vitro and in vivo [119].

The efficiency and bioavailability of these peptide mimics can be improved via various modifications including conjugation to hydrophobic molecules such as cholesterol, which greatly increases membrane intercalation and significantly reduce the amount of self-aggregation [120,121]. This same approach has also been successful in inhibiting in vitro and in vivo infections of HMPV, NiV, and MeV [122-125]. Notably, several peptides have shown the ability to impede fusion across different viral species, families, and orders. The efficacy of peptide-induced inhibition can be enhanced by altering peptide length and/or sequence, and inclusion of hydrophobic moieties to enhance binding to the fusion protein. For example, shorter peptides of the HR2/B region of HPIV2 and HPIV3 showed only reduced levels of infectivity but longer peptides completely inhibited viral entry and spread [126].

Interestingly, an HPIV-HRC peptide yielded a greater reduction in fusion toward live NiV and HeV than that of the HRC peptides of NiV and HeV peptides, respectively. This was thought to be due to the inverse correlation between F-triggering kinetics and peptide efficacy since NiV and HeV have longer fusion protein activation time than HPIV3 [127-130]. To probe the heterotypic anti-HeV efficacy of HPIV3 peptides, HeV-HPIV3 homotypic and chimeric peptides revealed that the HPIV3-HRC peptide interacts with the coiled-coil trimer of HeV-F, thereby blocking the formation of the 6HB [128]. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of the HPIV3-HRC peptide toward HPIV3 entry was improved with the addition of a cholesterol moiety to the C-terminus or N-terminus of the peptide. However, only the HPIV3-HRC peptides that were cholesterol tagged on the C-terminus had improved inhibition toward HeV or NiV pseudotyped virus and live virus entry [131].

Sequence optimization of HPIV3-HRC yielded a peptide, ‘VIKI’, with substitutions (E459V, A463I, Q479K, K480I) that improved inter-helical binding. The VIKI peptide with a cholesterol moiety and a PEG spacer at the C-terminus effectively inhibited infection of HPIV3 and NiV at low nanomolar concentrations in vitro. Prophylactic administration of VIKI-PEG4-chol two days before infection completely protected golden hamsters for up to 21 days after challenge with 100 × LD50 of NiV. Simultaneous infection of NiV in golden hamsters with VIKI-PEG4-chol treatment garnered a survival rate of 80%, while treatment beginning 2 days after infection yielded a survival rate of 40% [130]. Further, a cholesterol-tagged dimer of HPIV3-HRC with a PEGylated linker effectively inhibited viral entry of both HPIV3 and NiV and improved the survival of NiV infected hamsters when intraperitoneally administered [132]. The HPIV3-HRC peptide was further improved with the conjugation of a PEG24-cholesterol linker at the C-terminus, which interestingly greatly improved inhibition of NiV, while the N-terminally conjugated peptide preferentially inhibited HPIV3 [133]. Moreover, HPIV3-HRC with ‘VIKI’ substitutions conjugated to dPEG4 and tocopherol (toco) at the C-terminus produced a lipopeptide with improved protease resistance. The VIKI-dPEG4-toco lipopeptide yielded a survival rate of 50% in Syrian golden hamsters with only 3 administrations after a 100 × LD50 inoculation of NiV. The VIKI-dPEG4-toco peptide was also tested in African green monkeys and resulted in a survival rate of 33% compared to the untreated monkeys which all succumbed to NiV infection [134]. Another HPIV3 36-mer peptide, ‘VIQKI’ (E459V, A463I, D466Q, Q479K, K480I), with substitutions to enhance interactions with the fusion protein’s HRN domain to the PHI, inhibited fusion of HPIV3 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a former member of the Paramyxoviridae family now placed in the Pneumoviridae family [135]. VIQKI peptides with either an I454F or I456F substitution or both had improved antiviral efficacy toward HPIV3 and RSV due to improved binding of the trimeric core [136]. Several versions of HPIV3-HRC peptides inhibit MeV-induced cell–cell fusion at early time points, but could not reduce MeV titers in vivo [137]. Finally, single residue substitutions of α-to-β amino acids within the N-terminal region of VIQKI yielded peptides with comparable inhibitory activity compared to wt VIQKI but induced differing interactions with HPIV3-HRN [138••].

Inhibitory peptides can also block Rubulavirus entry. Peptides derived from the HRA (N-1) and HRB (C-1) regions of SV5 both effectively inhibited syncytium formation during incubation in cells expressing F and HN. However, the N-1 peptide inhibited fusion only at an early fusion intermediate stage; after receptor binding but before F activation. The C-1 peptide inhibited fusion by binding to the PHI before 6HB formation occurred [139].

A dimerized sequence of MeV-HRC conjugated to cholesterol (MeV-HRC4) inhibited MeV entry and spread in Vero cells. Mice prophylactically treated with MeV-HRC4 one day before infection and daily treatments for 1 week after infection protected mice from MeV-induced encephalitis. The brains of infected, non-treated mice revealed the presence of MeV nucleoprotein while mice treated MeV-HRC4 had no detectable viral antigen [140]. A MeV-HR2 peptide effectively inhibited infection of MeV into Vero cells, and interestingly an HPIV3-HRC peptide inhibited MeV entry into SLAM bearing cells [122,137]. Moreover, intranasal delivery of MeV-HRC4 protected mice better than subcutaneous injection by 80% compared to 60%, respectively [137]. Dimerized MeV-HRC peptides conjugated to toco or cholesterol and significantly reduced infection in cotton rats. MeV-HRC conjugated to toco remained in the lungs to a greater extent than the cholesterol conjugated peptide which localized more in the brain. In general, anti-MeV peptides inhibited fusion better in cells expressing receptor CD150 than nectin-4 [137,141].

Furthermore, a MeV-HRC peptide conjugated to 25-hydroxycholesterol demonstrated significant inhibitory activity in vitro [142]. SSPE, a persistent cell-cell only variant of the measles virus, [108] can also be inhibited with peptides generated from the MeV Edmonton strain HR2 domain, which significantly inhibited MeV plaque formation and improved the survival of SSPE infected mice to 67% [143]. A peptide of the α-helical region of MeV F (455–490) effectively inhibited syncytium formation in MeV and CDV infections and significantly reduced MeV entry into Vero cells [119].

Interestingly, peptides from Marek’s disease virus (MDV), from the family Herpesviridae, had inhibitory activity against NDV. To enhance cross-reactivity toward NDV and MDV, these peptides sequences from gH or gB proteins were linked to the HR region of NDV. Interestingly, the tandem peptide constructs had superior inhibitory activity than that of their monomeric peptides [144].

The F TM domain has also been a target for inhibitory fusion peptides. HeV-F TM domain peptides altered F stability, the ability of F to form homo-trimers, expression of F, and significantly inhibited syncytium formation but did not alter F’s ability to be cleaved into its active fusogenic form. This approach was also successful in reducing PIV5 infection with a PIV5 TM domain peptide [145•]. A peptide derived from the Respirovirus, SeV F protein sequence (473–495) inhibited hemolysis of erythrocytes at a low micromolar concentration after SeV had attached to the cell [146].

Anti-paramyxovirus antibodies

Another successful approach to paramyxovirus entry inhibition is antibody therapy. Similar to the approach used for early HIV antivirals, neutralizing antibodies effectively bind regions of the viral glycoproteins necessary for fusion [147].

Rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb) mAb66 binds to NiV-F and inhibits viral entry. Interestingly, antibody neutralization by mAb66 is unhindered by the presence of F glycosylation. However, it was observed that mAb66 has a better binding affinity toward NiV-F than HeV-F [61,148,149•]. The antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of mAb66 was revealed to bind within domain III (DIII) of the globular head of NiV-F. Likewise, mAb36 had a similar binding site to mAb66 but bound only HeV-F. Interestingly, 2 aa substitutions, Q70K + S74T, to NiV-F conferred neutralizing capabilities to mAb36 equivalent to HeV-F. Additionally, another polyclonal antibody, pAb835, also targets the F globular head in neutralizing NiV and HeV, supporting the hypothesis that the immune system commonly targets the apex of the HNV-F globular head for neutralization [149•]. Murine antibodies 1B2, 7G9, and 3D7 inhibited pseudotyped NiV entry by binding to NiV-G. However, these mAbs did not possess cross-reactivity to the closely related HeV [150•].

Human monoclonal antibodies m102 and m102.4 are reactive towards the ephrinB2/ephrinB3 binding sites on NiV-G and HeV-G [151]. Treatment with m102.4 10 hours post-challenge protected ferrets infected with NiV [152]. African green monkeys were completely protected from illness after HeV challenge when m102.4 was administered 3 days post-challenge. Furthermore, m102.4 can neutralize HeV and the Malaysian (M) and Bangladesh (B) strains of NiV and completely protected African green monkeys infected with NiV (M) 5 days and NiV (B) 3 dpi [153-156].

Murine 5B3 and humanized h5B3.1 antibodies inhibited HNV fusion binding to DIII of the globular head thereby locking F in the prefusion state. However, an escapemutant was generated after only three passages of live NiV with 5B3. The NiV-F escapemutant possessed a K55E mutation and was completely uninhibited by antibody 5B3, resulting in wild-type levels of fusion [157•].

The human monoclonal antibodies, 54G10, 17E10 binding to antigenic site IV on HMPV-F and RSV-F, while MPV364 bound to antigen site III of only HMPV-F [158,159••]. Mice prophylactically treated with 54G10 or MPV364 had reduced viral titers in the lungs compared to control mice infected with HMPV [159••,160]. Anti-HMPV-F Fab DS7 can neutralize genotypes A1, A2, and B1. Electron microscopy revealed that DS7 binds the DI and DII domains of the HMPV-F head. DS7 reduced HPMV plaque formation by 60% and significantly reduced viral titers in the lungs of cotton rats when administered 3 days after infection [161,162].

A murine mAb m77.4 that binds to the prefusion state of MeV F was constructed into a single-chained variable fragment (scFV) and inhibited viral fusion at low nanomolar concentrations. Prophylactic administration of the scFV into cotton rats induced significantly lower viral titers in the lungs after infecting with MeV [163].

An anti-HN mAb M1-1A inhibited HPIV2 induced cell-cell fusion by binding to the HN stalk at residues N83 and K91 without altering HA or NA activity. Inhibition of virus-cell fusion by M1-1A occurred after adsorption but before membrane merging [164-167]. Synthetic antibodies (sAb) have also been effective at neutralizing PIV5 entry. SAb 5D inhibited PIV5 fusion by binding to the N-terminal domain thereby stabilizing the prefusion state of F or by blocking F-HN interactions. Anti-PIV5 HN sAbs 1H and 4E bind to the HN stalk region (1–117) while sAb F4 binds to the HN NA domain and each is able to inhibit virus-cell fusion and syncytia formation [168,169].

Though anti-paramyxovirus antibodies are effective at inhibiting viral entry there still exists the possibility of resistance and escape-mutants being generated during their use [60,157•,170]. In addition, the cost and levels of antibodies needed to prevent or cure paramyxoviral infections may prohibit their extensive use in the case of a global pandemic.

Small-molecule antivirals

Several small-molecule antivirals have been discovered that target domains conformationally important in paramyxoviral fusion. For example, small non-peptide mimics, CSC7 and CSC11, induce premature activation of HPIV3 F. Treatment of CSC7 and CSC11 at 3 mM in HPIV3 infected HAE cells reduced viral titers by ~75% and ~100%, respectively. These compounds did not inhibit receptor binding but were found to prematurely activate the HN/F fusion mechanism before receptor binding [171]. Using conformational antibodies against HPIV3 to measure the activity of CSC11 allowed for the development of improved CSC11 derivatives. One such compound, CM9, had significantly improved inhibitory activity (IC50 = 920 μM) compared to CSC11 (IC50 = 2000 μM). A 3 mM treatment of CM9 completely inhibited HPIV3 infection of both laboratory and clinical strains. Structural antibody analysis revealed that CM9 induced F to transition into the 6HB state [172••]. Similar to CM9, compound PAC-0366 was able to trigger HPIV3 F in the absence of receptor binding with an improved IC50 by 100-fold compared to CM9 [173].

There have been reports of antiviral compounds that are effective against the influenza virus being excellent inhibitors of paramyxoviral entry. One such instance is Zanamivir, a neuraminidase inhibitor against HPIV3 infections. The pre-incubation of HPIV3 with Zanamivir during adsorption resulted in a decrease in plaque numbers, but not the size of the plaques. Zanamivir has an affinity toward the NA active site and sites where HN interacts to sialic acid receptor, which inhibts HPIV3 infectivity [174]. However, Zanamivir enhanced the HN receptor avidity in NDV entry, due to the occupation of the binding site I by Zanamivir, which activated the HN binding site II inducing greater receptor avidity [175]. Nevertheless, Zanamivir is an effective inhibitor of HPIV and NDV NA activity, but NDV is resistant to Zanamivir’s inhibitory effects on receptor binding and viral entry [176].

Additionally, glycan-mediated inhibition of fusion with griffithsin (GRFT), a high-mannose oligosaccharide binding lectin, was able to block viral entry and spread of NiV. GRT inhibits NiV-induced membrane fusion by interacting with NiV-G, thereby impeding virus-cell interactions. Trimeric GRFT (3 mG) had superior antiviral potency than monomeric GRFT. Prophylactic administration of 3 mG and an oxidation-resistant GRFT (Q-GRFT) protected hamsters from lethal intranasal challenge with NiV. However, Q-GRFT induced a greater survival rate (35%) than 3 mG (15%) [177].

A novel antiviral method aimed at reducing viral binding used heparan sulfate (HS) to block receptor binding of HMPV. Infection was reduced in BEAS-2B cells when pretreated with sulfated iota-carrageenan before infection with HMPV. This reduction in infectivity was due to iota-carrageenan competing with HS binding sites on HMPV-F. Highly sulfated K5 polysaccharide derivatives that possess a heparan-like structure could also inhibit the ability for HMPV to bind HS [178]. Additionally, the process of NiV particles binding to cells could be inhibited or displaced when cells are pretreated with heparin [48]. Furthermore, an HRA2 analog peptide expressed in Nicotiana tabacum plants was an effective inhibitor of HMPV binding to HS [179].

Recently, Presatovir underwent phase II clinical trials as a fusion inhibitor for RSV [180]. In healthy adults Presatovir successfully reduced viral load and symptom score compared to patients receiving a placebo [181]. Presatovir inhibits RSV induced membrane fusion by binding to the prefusion state of RSV-F thereby preventing conformational changes necessary for membrane fusion [182].

Additionally, small compounds that inhibit MeV infections have been explored. For example, anti-MeV compounds oxazole 1 (OX-1) and its improved variant AM-4 were originally designed to bind MeV-F near the FP. However, despite AM-4’s high inhibitory activity it had a short half-life [183,184]. Nevertheless, structural optimization of AM-4 led to the development of a more stable compound, AS-48, effectively inhibited several MeV genotypes as well as CDV and RPV. Both AS-48 and FIP, a fusion inhibitor peptide, bind to MeV-F in the N-terminal portion of HRB where the head and stalk connect. This protein-inhibitor interaction locks MeV-F in the prefusion state by linking individual F protomers at the hydrophobic pocket, which impedes conformational changes [185]. Interestingly, mutations to the MeV-F HRB region granted MeV resistance to AS-48 and FIP without negatively affecting membrane fusion. However, after several passages of the MeV without the selective pressure of FIP, MeV-F reverted to the wild-type sequence. This suggests that the beneficial MeV-F mutations against FIP came as a detriment to viral fitness [186-188].

Some of the most effective broad-spectrum antivirals are the LJ and JL series. LJ001 is a lipophilic thiazolidine derivative requiring light for activation and, in the presence of oxygen, produces singlet oxygen (1O2) free radicals. 1O2-induced allylic hydroxylation in unsaturated fatty acid chains stimulates trans-isomerization and the addition of a hydroxyl group in the lipid bilayer. LJ001 inserts into the viral membrane and by singlet oxygen (1O2) mechanism causes an increase in lipid packing density, thereby reduce membrane fluidity, which ultimately reduces virus-cell fusion. LJ001 has shown to be effective at reducing the viral spread between fish in an aquaculture environment. LJ001 is effective at inhibiting a variety of enveloped viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, filoviruses, flaviviruses, HIV-1, Influenza A, paramyxoviruses, and poxviruses. Treatment with LJ001 leaves the virus intact but inhibits the viral particle-cell fusion [189,190].

The development of small compound broad-spectrum antivirals such as LJ001 has become an objective of much research amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent studies have aimed to understand the mechanism by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus becomes fusogenically active, and it has been the elucidation of this mechanism that has provided much insight into potential targets for broad-spectrum inhibition of enveloped viruses, notably paramyxoviruses and coronaviruses. For SARS-CoV-2 to invade host cells, the activation of its Spike protein (S protein) is a requirement that is ultimately achieved through the proteolytic cleavage of S by transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), a type II transmembrane serine protease (TTSP), into an S1 and S2 subunit. The S1 subunit binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of the cell membrane, which facilitates the attachment of SARS-CoV-2 to the surface of a host cell. The S2 subunit drives the fusion of viral and cellular membranes that results in viral infection [191,192]. Considering its role in priming the S protein for viral entry, the inhibition of TMPRSS2 is a prime target for the development of antivirals for SARS-CoV-2. In vitro experimentation with camostat mesylate, a clinically proven serine protease inhibitor that is active against TMPRSS2, demonstrated reduced SARS-CoV-2 entry and infection in a Caco-2 cell line [193••]. In vivo experiments with SARS-CoV-2 are still ongoing, in which the efficacy of camostat mesylate, both alone and in combination with other proposed antivirals, will be assessed [194]. These results offer a potential broad-spectrum application when considering the similar role transmembrane serine proteases have been proven to fulfill in the cleavage of hemagglutinin (HA) protein in influenza A virus (IAV) and the fusion protein (F protein) in HPIVs and other paramyxoviruses. Protease inhibitors such as the new broad-spectrum N-0385 may prove useful across viral families [195••]. Camostat mesylate demonstrated a reduction in replication of IAV in human tracheal epithelial cells as a result of a reduction in proteolytic cleavage of HA by TMPRSS2 [196]. To date, there have not been any conclusive studies that have proven the effect of serine protease inhibitors on paramyxovirus entry. This is believed to be a result of a lack of understanding behind the main proteases responsible for pathogenesis. Nonetheless, the evidence provided by present studies indicates that serine protease inhibitors have an immense potential for use as broad-spectrum antivirals. Further elucidation of viral entry mechanisms and the roles of TTSPs will be crucial to assessing this possibility in the future.

Conclusions

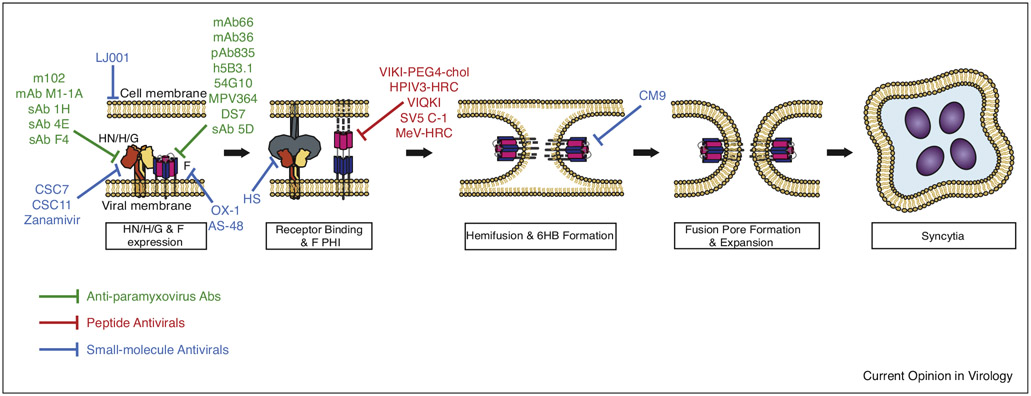

Great strides have been made in the development of potential antivirals towards paramyxovirus fusion as shown in Figure 1. However, given the limited options of vaccines and antivirals, more prophylactic options are needed. The U.S. has had great success in reducing the outbreaks of MeV with an effective vaccine and schools mandated vaccine requirements [197•]. The same cannot be said globally where suboptimal vaccines have left a large population vulnerable to MeV infections. Furthermore, recent serological screenings worldwide of bats and rodents have demonstrated that there is a continuously growing number of viruses that have the potential to causes serious health and economic burden. This underscores the urgency for the development of new antivirals. Since the advent of the first successful peptidomimetic HIV-1 antiviral T-20 (enfuvirtide), there have been a plethora of homologous paramyxovirus peptides capable of inhibiting viral entry. Fortunately, if viruses share enough fusion protein structural homology, a peptide or small molecule for one virus may be effective for another. There have been a few successful attempts at producing broad-spectrum antivirals for enveloped viruses [198]. However, although these antiviral approaches have been successful, they all face the hurdle of the appearance of resistance mutations. To combat the constant emergence of new paramyxoviruses, the future of paramyxovirus and all enveloped viruses’ fusion inhibitors may include having a common target unable to mutate, such as the viral membrane, such as the LJ and JL class of antivirals that protected fish from the horizontal transmission [199]. However, a major downside with these antivirals is the need for light for activation. Nevertheless, they serve as an archetypal antiviral method that should be further explored. An ideal antiviral would be able to target the viral membrane and completely halt the ability of the viral membrane to fuse with the cell membrane. Furthermore, such antivirals should leave the viral proteins and genetic material unaltered. This could potentially allow for large scale inactivation of viruses that may aid inactivated-virus vaccine development. With the viral glycoproteins unaffected, the antigenic sites would remain relatively more intact, allowing for greater immune responses post-challenge.

Figure 1.

Summary of Paramyxovirus antiviral target locations within the membrane fusion cascade model. Green bars indicate anti-paramyxovirus antibody epitopes, Red bars show peptide targets, and blue bars point to small-molecule antiviral interaction sites. PHI = Pre-hairpin Intermediate, 6HB = 6 Helix Bundle.

Acknowledgements

These investigators were funded by N.I.H. grants R01AI109022, R21AI142377, and R21AI156731 to H.A.C. and funding to H.A.C from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) administered through Cooperative Agreement D18AC00031-PREEMPT.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Stein-Zamir C, Shoob H, Abramson N, Zentner G: Who are the children at risk? Lessons learned from measles outbreaks. Epidemiol Infect 2012, 140:1578–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanne JH: Rise in US measles cases is blamed on unimmunized travelers. Br Med J 2014, 348:g3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons E, Ferrari M, Fricks J, Wannemuehler K, Anand A, Burton A, Strebel P: Assessment of the 2010 global measles mortality reduction goal: results from a model of surveillance data. Lancet 2012, 379:2173–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabbagh A, Laws RL, Steulet C, Dumolard L, Mulders MN, Kretsinger K, Alexander JP, Rota PA, Goodson JL: Progress toward regional measles elimination - worldwide, 2000-2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018, 67:1323–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dayan GH, Rubin S, Plotkin S: Mumps outbreaks in vaccinated populations: are available mumps vaccines effective enough to prevent outbreaks? Clin Infect Dis 2008, 47:1458–1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avramovich E, Indenbaum V, Haber M, Amitai Z, Tsifanski E, Farjun S, Sarig A, Bracha A, Castillo K, Markovich MP et al. : Measles outbreak in a highly vaccinated population - Israel, July-August 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018, 67:1186–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterhaus A, Vedder EJ: Identification of virus causing recent seal deaths. Nature 1988, 335:20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.RoelkeParker ME, Munson L, Packer C, Kock R, Cleaveland S, Carpenter M, Obrien SJ, Pospischil A, HofmannLehmann R, Lutz H et al. : A canine distemper virus epidemic in Serengeti lions (Panthera leo). Nature 1996, 379:441–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai K, Nagata N, Ami Y, Seki F, Suzaki Y, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Suzuki T, Fukushi S, Mizutani T, Yoshikawa T et al. : Lethal canine distemper virus outbreak in cynomolgus monkeys in Japan in 2008. J Virol 2013, 87:1105–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rendon-Marin S, Budaszewski RD, Canal CW, Ruiz-Saenz J: Tropism and molecular pathogenesis of canine distemper virus. Virol J 2019, 16:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau RK, Turner MD: Viral mumps: increasing occurrences in the vaccinated population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2019, 128:386–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chua KB, Bellini WJ, Rota PA, Harcourt BH, Tamin A, Lam SK, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Shieh WJ et al. : Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science 2000, 288:1432–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua KB: Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. J Clin Virol 2003, 26:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Homaira N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Epstein JH, Sultana R, Khan MSU, Podder G, Nahar K, Ahmed B, Gurley ES et al. : Nipah virus outbreak with person-to-person transmission in a district of Bangladesh, 2007. Epidemiol Infect 2010, 138:1630–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo MK, Lowe L, Hummel KB, Sazzad HMS, Gurley ES, Hossain MJ, Luby SP, Miller DM, Comer JA, Rollin PE et al. : Characterization of Nipah virus from outbreaks in Bangladesh, 2008-2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2012, 18:248–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulkarni DD, Tosh C, Venkatesh G, Senthil Kumar D: Nipah virus infection: current scenario. Indian J Virol 2013, 24:398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montgomery JM, Hossain MJ, Gurley E, Carroll DS, Croisier A, Bertherat E, Asgari N, Formenty P, Keeler N, Comer J et al. : Risk factors for Nipah virus encephalitis in Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 2008, 14:1526–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramphul K, Mejias SG, Agumadu VC, Sombans S, Sonaye R, Lohana P: The killer virus called Nipah: a review. Cureus 2018, 10:e3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.•. Yadav PD, Shete AM, Kumar GA, Sarkale P, Sahay RR, Radhakrishnan C, Lakra R, Pardeshi P, Gupta N, Gangakhedkar RR et al. : Nipah virus sequences from humans and bats during Nipah outbreak, Kerala, India, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis 2019, 25:1003–1006 Utilizing Nipah virus sequences from 4 human and 3 bat samples, this paper established bats as the source of the Bangladesh strain NiV outbreak in India.

- 20.•. Arunkumar G, Chandni R, Mourya DT, Singh SK, Sadanandan R, Sudan P, Bhargava B: Outbreak investigation of Nipah virus disease in Kerala, India, 2018. J Infect Dis 2019, 219:1867–1878 This report details transmission events that elucidate Nipah virus nosocomial transmission.

- 21.Chong H-T, Kamarulzaman A, Tan C-T, Goh K-J, Thayaparan T, Kunjapan SR, Chew N-K, Chua K-B, Lam S-K: Treatment of acute Nipah encephalitis with ribavirin. Ann Neurol 2001, 49:810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furuta Y, Takahashi K, Kuno-Maekawa M, Sangawa H, Uehara S, Kozaki K, Nomura N, Egawa H, Shiraki K: Mechanism of action of T-705 against influenza virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005, 49:981–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.•. Banerjee S, Niyas VKM, Soneja M, Shibeesh AP, Basheer M, Sadanandan R, Wig N, Biswas A: First experience of ribavirin postexposure prophylaxis for Nipah virus, tried during the 2018 outbreak in Kerala, India. J Infect 2019, 78:497–499 This paper demonstrates the protection of eight Indian healthcare workers (HCW) from Nipah Virus (NiV) through ribavirin post-exposure prophylaxis (rPEP). Should another outbreak occur, rPEP has potential to protect HCWs and civilians.

- 24.Halpin K, Young PL, Field HE, Mackenzie JS: Isolation of Hendra virus from pteropid bats: a natural reservoir of Hendra virus. J Gen Virol 2000, 81:1927–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Field HE, Barratt PC, Hughes RJ, Shield J, Sullivan ND: A fatal case of Hendra virus infection in a horse in north Queensland: clinical and epidemiological features. Aust Vet J 2000, 78:279–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang LF: Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4:23–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Z, Yang L, Yang F, Ren X, Jiang J, Dong J, Sun L, Zhu Y, Zhou H, Jin Q: Novel Henipa-like virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in rats, China, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20:1064–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rissanen I, Ahmed AA, Azarm K, Beaty S, Hong P, Nambulli S, Duprex WP, Lee B, Bowden TA: Idiosyncratic Mòjiāng virus attachment glycoprotein directs a host-cell entry pathway distinct from genetically related henipaviruses. Nat Commun 2017, 8:16060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein JH, Prakash V, Smith CS, Daszak P, McLaughlin AB, Meehan G, Field HE, Cunningham AA: Henipavirus infection in fruit bats (Pteropus giganteus), India. Emerg Infect Dis 2008, 14:1309–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drexler JF, Corman VM, Mueller MA, Maganga GD, Vallo P, Binger T, Gloza-Rausch F, Rasche A, Yordanov S, Seebens A et al. : Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat Commun 2012, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbu’u CM, Mbacham WF, Gontao P, Kamdem SLS, Nloga AMN, Groschup MH, Wade A, Fischer K, Balkema-Buschmann A: Henipaviruses at the interface between bats, livestock and human population in Africa: a review. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2019, 19:455–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Araujo J, Lo MK, Tamin A, Ometto TL, Thomazelli LM, Nardi MS, Hurtado RF, Nava A, Spiropoulou CF, Rota PA et al. : Antibodies against henipa-like viruses in Brazilian bats. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2017, 17:271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin DE: Measles vaccine. Viral Immunol 2018, 31:86–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore ZS, Seward JF, Lane JM: Smallpox. Lancet 2006, 367:425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Normile D: Animal science. Rinderpest, deadly for cattle, joins smallpox as a vanquished disease. Science 2010, 330:435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhlebach MD, Mateo M, Sinn PL, Prufer S, Uhlig KM, Leonard VHJ, Navaratnarajah CK, Frenzke M, Wong XX, Sawatsky B et al. : Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature 2011, 480:530–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pratakpiriya W, Seki F, Otsuki N, Sakai K, Fukuhara H, Katamoto H, Hirai T, Maenaka K, Techangamsuwan S, Lan NT et al. : Nectin4 is an epithelial cell receptor for canine distemper virus and involved in neurovirulence. J Virol 2012, 86:10207–10210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birch J, Juleff N, Heaton MP, Kalbfleisch T, Kijas J, Bailey D: Characterization of ovine nectin-4, a novel peste des petits ruminants virus receptor. J Virol 2013, 87:4756–4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negrete OA, Levroney EL, Aguilar HC, Bertolotti-Ciarlet A, Nazarian R, Tajyar S, Lee B: EphrinB2 is the entry receptor for Nipah virus, an emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Nature 2005, 436:401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguilar HC, Ataman ZA, Aspericueta V, Fang AQ, Stroud M, Negrete OA, Kammerer RA, Lee B: A novel receptor-induced activation site in the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein (G) involved in triggering the fusion glycoprotein (F). J Biol Chem 2009, 284:1628–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsh GA, de Jong C, Barr JA, Tachedjian M, Smith C, Middleton D, Yu M, Todd S, Foord AJ, Haring V et al. : Cedar virus: a novel henipavirus isolated from Australian bats. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krüger N, Hoffmann M, Weis M, Drexler JF, Müller MA, Winter C, Corman VM, Gützkow T, Drosten C, Maisner A et al. : Surface glycoproteins of an African henipavirus induce syncytium formation in a cell line derived from an African fruit bat, Hypsignathus monstrosus. J Virol 2013, 87:13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence P, Escudero Pérez B, Drexler JF, Corman VM, Müller MA, Drosten C, Volchkov V: Surface glycoproteins of the recently identified African henipavirus promote viral entry and cell fusion in a range of human, simian and bat cell lines. Virus Res 2014, 181:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradel-Tretheway BG, Liu Q, Stone JA, McInally S, Aguilar HC: Novel functions of Hendra virus G N-glycans and comparisons to Nipah virus. J Virol 2015, 89:7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee B, Pernet O, Ahmed AA, Zeltina A, Beaty SM, Bowden TA: Molecular recognition of human ephrinB2 cell surface receptor by an emergent African henipavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:E2156–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.••. Laing ED, Navaratnarajah CK, Da Silva SC, Petzing SR, Xu Y, Sterling SL, Marsh GA, Wang LF, Amaya M, Nikolov dB et al. : Structural and functional analyses reveal promiscuous and species specific use of ephrin receptors by Cedar virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:20707–20715 Using CHO-K1 cell lines, these authors showed that Cedar Virus G can bind to class B and A ephrins, particularly utilizing ephrin-A2, ephrin-A5, and ephrin-B1 as receptors. Infection in cells with mouse ephrin-A1 but not human ephrin-A1 also displayed species-specific ephrin receptor usage in this henipavirus.

- 47.•. Voigt K, Hoffmann M, Drexler JF, Muller MA, Drosten C, Herrler G, Kruger N: Fusogenicity of the Ghana virus (Henipavirus: Ghanaian bat henipavirus) fusion protein is controlled by the cytoplasmic domain of the attachment glycoprotein. Viruses 2019, 11:14. Using truncated and chimeric Ghana virus (GhV) G proteins, this study indicates that the cytoplasmic tail of GhV G facilitates the fusogenicity of GhV F, and thus GhV G controls fusogenicity of the GhV glycoproteins.

- 48.Mathieu C, Dhondt KP, Châlons M, Mély S, Raoul H, Negre D, Cosset F-L, Gerlier D, Vivès RR, Horvat B: Heparan sulfate-dependent enhancement of henipavirus infection. mBio 2015, 6:e02427–02414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansson GC, Karlsson KA, Larson G, Stromberg N, Thurin J, Orvell C, Norrby E: A novel-approach to the study of glycolipid receptors for viruses - binding of Sendai virus to thin-layer chromatograms. FEBS Lett 1984, 170:15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moscona A, Peluso RW: Relative affinity of the human parainfluenza virus type 3 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase for sialic acid correlates with virus-induced fusion activity. J Virol 1993, 67:6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki T, Portner A, Scroggs RA, Uchikawa M, Koyama N, Matsuo K, Suzuki Y, Takimoto T: Receptor specificities of human respiroviruses. J Virol 2001, 75:4604–4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villar E, Barroso IM: Role of sialic acid-containing molecules in paramyxovirus entry into the host cell: a minireview. Glycoconj J 2006, 23:5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendoza-Magaña ML, Godoy-Martinez DV, Guerrero-Cazares H, Rodriguez-Peredo A, Dueñas-Jimenez JM, Dueñas-Jiménez SH, Ramírez-Herrera MA: Blue eye disease porcine rubulavirus (PoRv) infects pig neurons and glial cells using sialoglycoprotein as receptor. Vet J 2007, 173:428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ortega V, Stone JA, Contreras EM, Iorio RM, Aguilar HC: Addicted to sugar: roles of glycans in the order Mononegavirales. Glycobiology 2019, 29:2–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bose S, Welch BD, Kors CA, Yuan P, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA: Structure and mutagenesis of the parainfluenza virus 5 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase stalk domain reveals a four-helix bundle and the role of the stalk in fusion promotion. J Virol 2011, 85:12855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong JJW, Young TA, Zhang J, Liu S, Leser GP, Komives EA, Lamb RA, Zhou ZH, Salafsky J, Jardetzky TS: Monomeric ephrinB2 binding induces allosteric changes in Nipah virus G that precede its full activation. Nat Commun 2017, 8:781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stone-Hulslander J, Morrison TG: Detection of an interaction between the HN and F proteins in Newcastle disease virus-infected cells. J Virol 1997, 71:6287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao Q, Hu X, Compans RW: Association of the parainfluenza virus fusion and hemagglutinin-neuraminidase glycoproteins on cell surfaces. J Virol 1997, 71:650–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takimoto T, Taylor GL, Connaris HC, Crennell SJ, Portner A: Role of the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein in the mechanism of paramyxovirus-cell membrane fusion. J Virol 2002, 76:13028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guillaume V, Aslan H, Ainouze M, Guerbois M, Wild TF, Buckland R, Langedijk JPM: Evidence of a potential receptor-binding site on the Nipah virus G protein (NiV-G): identification of globular head residues with a role in fusion promotion and their localization on an NiV-G structural model. J Virol 2006, 80:7546–7554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aguilar HC, Matreyek KA, Choi DY, Filone CM, Young S, Lee B: Polybasic KKR motif in the cytoplasmic tail of Nipah virus fusion protein modulates membrane fusion by inside-out signaling. J Virol 2007, 81:4520–4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cifuentes-Muñoz N, Sun W, Ray G, Schmitt PT, Webb S, Gibson K, Dutch RE, Schmitt AP: Mutations in the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of Hendra virus fusion protein disrupt virus-like-particle assembly. J Virol 2017, 91:e00152–00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakaguchi T, Fujii Y, Kiyotani K, Yoshida T: Correlation of proteolytic cleavage of F protein precursors in paramyxoviruses with expression of the fur, PACE4 and PC6 genes in mammalian cells. J Gen Virol 1994, 75:2821–2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pager CT, Dutch RE: Cathepsin L is involved in proteolytic processing of the Hendra virus fusion protein. J Virol 2005, 79:12714–12720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pager CT, Craft WW Jr, Patch J, Dutch RE: A mature and fusogenic form of the Nipah virus fusion protein requires proteolytic processing by cathepsin L. Virology 2006, 346:251–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welch BD, Liu Y, Kors CA, Leser GP, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA: Structure of the cleavage-activated prefusion form of the parainfluenza virus 5 fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109:16672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Diederich S, Sauerhering L, Weis M, Altmeppen H, Schaschke N, Reinheckel T, Erbar S, Maisner A: Activation of the Nipah virus fusion protein in MdCk cells is mediated by cathepsin B within the endosome-recycling compartment. J Virol 2012, 86:3736–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morrison TG: Structure and function of a paramyxovirus fusion protein. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2003, 1614:73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dutch RE, Hagglund RN, Nagel MA, Paterson RG, Lamb RA: Paramyxovirus fusion (F) protein: a conformational change on cleavage activation. Virology 2001, 281:138–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.•. Liu Y, Chi MM, Wen HL, Zhao L, Song YY, Liu N, Chi LL, Wang ZY: The DI-DII linker of human parainfluenza virus type 3 fusion protein is critical for the virus. Virus Genes 2020, 56:37–48 This paper reports that the DI-DII linker of the human parainfluenza virus type 3 fusion protein is required for membranes to completely fuse.

- 71.Brindley MA, Chaudhury S, Plemper RK: Measles virus glycoprotein complexes preassemble intracellularly and relax during transport to the cell surface in preparation for fusion. J Virol 2015, 89:1230–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murakami M, Towatari T, Ohuchi M, Shiota M, Akao M, Okumura Y, Parry MA, Kido H: Mini-plasmin found in the epithelial cells of bronchioles triggers infection by broad-spectrum influenza A viruses and Sendai virus. Eur J Biochem 2001, 268:2847–2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schowalter RM, Smith SE, Dutch RE: Characterization of human metapneumovirus F protein-promoted membrane fusion: critical roles for proteolytic processing and low pH. J Virol 2006, 80:10931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lou Z, Xu Y, Xiang K, Su N, Qin L, Li X, Gao GF, Bartlam M, Rao Z: Crystal structures of Nipah and Hendra virus fusion core proteins. FEBS J 2006, 273:4538–4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K: Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2008, 43:189–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wong JJW, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS: Structure and stabilization of the Hendra virus F glycoprotein in its prefusion form. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113:1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Joshi SB, Dutch RE, Lamb RA: A core trimer of the paramyxovirus fusion protein: parallels to influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp41. Virology 1998, 248:20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gardner AE, Dutch RE: A conserved region in the F2 subunit of paramyxovirus fusion proteins is involved in fusion regulation. J Virol 2007, 81:8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gardner AE, Martin KL, Dutch RE: A conserved region between the heptad repeats of paramyxovirus fusion proteins is critical for proper F protein folding. Biochemistry 2007, 46:5094–5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Aguilar HC, Henderson BA, Zamora JL, Johnston GP: Paramyxovirus glycoproteins and the membrane fusion process. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep 2016, 3:142–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bishop KA, Stantchev TS, Hickey AC, Khetawat D, Bossart KN, Krasnoperov V, Gill P, Feng YR, Wang L, Eaton BT et al. : Identification of Hendra virus G glycoprotein residues that are critical for receptor binding. J Virol 2007, 81:5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Porotto M, Fornabaio M, Kellogg GE, Moscona A: A second receptor binding site on human parainfluenza virus type 3 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase contributes to activation of the fusion mechanism. J Virol 2007, 81:3216–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stone JA, Vemulapati BM, Bradel-Tretheway B, Aguilar HC: Multiple strategies reveal a bidentate interaction between the Nipah virus attachment and fusion glycoproteins. J Virol 2016, 90:10762–10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Russell CJ, Kantor KL, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA: A dual-functional paramyxovirus F protein regulatory switch segment: activation and membrane fusion. J Cell Biol 2003, 163:363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.••. Slaughter KB, Dutch RE: Transmembrane domain dissociation is required for Hendra virus F protein fusogenic activity. J Virol 2019, 93:e01069–01019 This is the first study to report that HeV F fusogenic activity is dependent on transmembrane domain dissociation.

- 86.Brindley MA, Takeda M, Plattet P, Plemper RK: Triggering the measles virus membrane fusion machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109:E3018–E3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bose S, Welch BD, Kors CA, Yuan P, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA: Structure and mutagenesis of the parainfluenza virus 5 hemagglutinin-neuraminidase stalk domain reveals a four-helix bundle and the role of the stalk in fusion promotion. J Virol 2011, 85:12855–12866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Horvath CM, Paterson RG, Shaughnessy MA, Wood R, Lamb RA: Biological activity of paramyxovirus fusion proteins: factors influencing formation of syncytia. J Virol 1992, 66:4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Okamoto K, Ohgimoto S, Nishio M, Tsurudome M, Kawano M, Komada H, Ito M, Sakakura Y, Ito Y: Paramyxovirus-induced syncytium cell formation is suppressed by a dominant negative fusion regulatory protein-1 (FRP-1)/CD98 mutated construct: an important role of FRP-1 in virus-induced cell fusion. J Gen Virol 1997, 78:775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wong KT, Shieh WJ, Kumar S, Norain K, Abdullah W, Guarner J, Goldsmith CS, Chua KB, Lam SK, Tan CT et al. : Nipah virus infection - pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am J Pathol 2002, 161:2153–2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu K, Chan YP, Bradel-Tretheway B, Akyol-Ataman Z, Zhu Y, Dutta S, Yan L, Feng Y, Wang LF, Skiniotis G et al. : Crystal structure of the pre-fusion Nipah virus fusion glycoprotein reveals a novel hexamer-of-trimers assembly. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11:e1005322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barton JT, Bickford AA, Cooper GL, Charlton BR, Cardona CJ: Avian paramyxovirus type-1 infections in racing pigeons in California .1. Clinical signs, pathology, and serology. Avian Dis 1992, 36:463–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ganar K, Das M, Sinha S, Kumar S: Newcastle disease virus: current status and our understanding. Virus Res 2014, 184:71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wong KT, Shieh WJ, Kumar S, Karim N, Guarner J, Abdullah W, Zaki S: Nipah encephalitis: pathology and pathogenesis of a new, emerging paramyxovirus infection. Brain Pathol 2000, 10:794–795. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mohd Nor MN, Gan CH, Ong BL: Nipah virus infection of pigs in peninsular Malaysia. Rev Sci Tech 2000, 19:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ahmad K: Malaysia culls pigs as Nipah virus strikes again. Lancet 2000, 356:230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.O’Sullivan JD, Allworth AM, Paterson DL, Snow TM, Boots R, Gleeson LJ, Gould AR, Hyatt AD, Bradfield J: Fatal encephalitis due to novel paramyxovirus transmitted from horses. Lancet 1997, 349:93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hooper P, Zaki S, Daniels P, Middleton D: Comparative pathology of the diseases caused hy Hendra and Nipah viruses. Microbes Infect 2001, 3:315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Counihan ME, Shay DK, Holman RC, Lowther SA, Anderson LJ: Human parainfluenza virus-associated hospitalizations among children less than five years of age in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001, 20:646–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Madden JF, Burchette JL, Hale LP: Pathology of parainfluenza virus infection in patients with congenital immunodeficiency syndromes. Hum Pathol 2004, 35:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Weinberg GA, Hall CB, Iwane MK, Poehling KA, Edwards KM, Griffin MR, Staat MA, Curns AT, Erdman DD, Szilagyi PG et al. : Parainfluenza virus infection of young children: estimates of the population-based burden of hospitalization. J Pediatr 2009, 154:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abedi GR, Prill MM, Langley GE, Wikswo ME, Weinberg GA, Curns AT, Schneider E: Estimates of parainfluenza virus-associated hospitalizations and cost among children aged less than 5 years in the United States, 1998-2010. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016, 5:7–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Philip BN, Reinhard KR, Lackman DB: Observations on a mumps epidemic in a “virgin” population. Am J Epidemiol 1959, 69:91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Barták V: Sperm count, morphology and motility after unilateral mumps orchitis. Reproduction 1973, 32:491–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.••. Morrison JC, Givens JR, Wiser WL, Fish SA: Mumps oophoritis: a cause of premature menopause. Fertil Steril 1975, 26:655–659 Supported by Grant RR-211 from the General Clinical Research Center Program at the National Institutes of Health to the University of Tennessee Research Center, where this study was conducted.

- 106.Davis NF, McGuire BB, Mahon JA, Smyth AE, O’Malley KJ, Fitzpatrick JM: The increasing incidence of mumps orchitis: a comprehensive review. BJU Int 2010, 105:1060–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Guler S, Kucukkoc M, Iscan A: Prognosis and demographic characteristics of SSPE patients in Istanbul, Turkey. Brain Dev 2015, 37:612–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mekki M, Eley B, Hardie D, Wilmshurst JM: Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: clinical phenotype, epidemiology, and preventive interventions. Dev Med Child Neurol 2019, 61:1139–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.•. Mina MJ, Kula T, Leng Y, Li M, de Vries RD, Knip M, Siljander H, Rewers M, Choy DF, Wilson MS et al. : Measles virus infection diminishes preexisting antibodies that offer protection from other pathogens. Science 2019, 366:599. These authors demonstrated a reduction in humoral immune memory in unvaccinated children infected by measles virus.

- 110.Machida N, Kiryu K, Oh-ishi K, Kanda E, Izumisawa N, Nakamura T: Pathology and epidemiology of canine distemper in raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides). J Comp Pathol 1993, 108:383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Summers BA, Appel MJG: Syncytia formation: an aid in the diagnosis of canine distemper encephalomyelitis. J Comp Pathol 1985, 95:425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vandevelde M, Zurbriggen A: Demyelination in canine distemper virus infection: a review. Acta Neuropathol 2005, 109:56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Takayama I, Kubo M, Takenaka A, Fujita K, Sugiyama T, Arai T, Yoneda M, Sato H, Yanai T, Kai C: Pathological and phylogenetic features of prevalent canine distemper viruses in wild masked palm civets in Japan. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2009, 32:539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Woo PCY, Lau SKP, Wong BHL, Fan RYY, Wong AYP, Zhang AJX, Wu Y, Choi GKY, Li KSM, Hui J et al. : Feline morbillivirus, a previously undescribed paramyxovirus associated with tubulointerstitial nephritis in domestic cats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109:5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.•. Stranieri A, Lauzi S, Dallari A, Gelain ME, Bonsembiante F, Ferro S, Paltrinieri S: Feline morbillivirus in Northern Italy: prevalence in urine and kidneys with and without renal disease. Vet Microbiol 2019, 233:133–139 This paper demonstrated the genetic diversity of feline morbillivirus (FeMV) through detection of distinct genotypes. These authors did not find a clear relationship between FeMV and chronic kidney disease in cats.

- 116.Kvellestad A, Dannevig BH, Falk K: Isolation and partial characterization of a novel paramyxovirus from the gills of diseased seawater-reared Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). J Gen Virol 2003, 84:2179–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yang B, Qi XF, Guo H, Jia PL, Chen SY, Chen ZJ, Wang T, Wang JY, Xue QH: Peste des petits ruminants virus enters caprine endometrial epithelial cells via the caveolae-mediated endocytosis pathway. Front Microbiol 2018, 9:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Diallo A, Minet C, Le Goff C, Berhe G, Albina E, Libeau G, Barrett T: The threat of peste des petits ruminants: progress in vaccine development for disease control. Vaccine 2007, 25:5591–5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wild TF, Buckland R: Inhibition of measles virus infection and fusion with peptides corresponding to the leucine zipper region of the fusion protein. J Gen Virol 1997, 78:107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Johnston KM, Key DW: Paramyxovirus-1 in feral pigeons (Columba livia) in Ontario. Can Vet J 1992, 33:796–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Augusto MT, Hollmann A, Porotto M, Moscona A, Santos NC: Antiviral lipopeptide-cell membrane interaction is influenced by PEG linker length. Molecules 2017, 22:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lambert DM, Barney S, Lambert AL, Guthrie K, Medinas R, Davis DE, Bucy T, Erickson J, Merutka G, Petteway SR: Peptides from conserved regions of paramyxovirus fusion (F) proteins are potent inhibitors of viral fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93:2186–2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rockstroh JK, Mauss S: Clinical perspective of fusion inhibitors for treatment of HIV. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004, 53:700–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Matthews T, Salgo M, Greenberg M, Chung J, DeMasi R, Bolognesi D: Enfuvirtide: the first therapy to inhibit the entry of HIV-1 into host CD4 lymphocytes. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004, 3:215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Broder CC: Henipavirus outbreaks to antivirals: the current status of potential therapeutics. Curr Opin Virol 2012, 2:176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yao QZ, Compans RW: Peptides corresponding to the heptad repeat sequence of human parainfluenza virus fusion protein are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Virology 1996, 223:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Porotto M, Doctor L, Carta P, Fornabaio M, Greengard O, Kellogg GE, Moscona A: Inhibition of Hendra virus fusion. J Virol 2006, 80:9837–9849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Porotto M, Carta P, Deng Y, Kellogg GE, Whitt M, Lu M, Mungall BA, Moscona A: Molecular determinants of antiviral potency of paramyxovirus entry inhibitors. J Virol 2007, 81:10567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Porotto M, Yokoyama CC, Orefice G, Kim HS, Aljofan M, Mungall BA, Moscona A: Kinetic dependence of paramyxovirus entry inhibition. J Virol 2009, 83:6947–6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Porotto M, Rockx B, Yokoyama CC, Talekar A, Devito I, Palermo LM, Liu J, Cortese R, Lu M, Feldmann H et al. : Inhibition of Nipah virus infection in vivo: targeting an early stage of paramyxovirus fusion activation during viral entry. PLoS Pathog 2010, 6:e1001168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Porotto M, Yokoyama CC, Palermo LM, Mungall B, Aljofan M, Cortese R, Pessi A, Moscona A: Viral entry inhibitors targeted to the membrane site of action. J Virol 2010, 84:6760–6768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pessi A, Langella A, Capito E, Ghezzi S, Vicenzi E, Poli G, Ketas T, Mathieu C, Cortese R, Horvat B et al. : A general strategy to endow natural fusion-protein-derived peptides with potent antiviral activity. PLoS One 2012, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mathieu C, Augusto MT, Niewiesk S, Horvat B, Palermo LM, Sanna G, Madeddu S, Huey D, Castanho M, Porotto M et al. : Broad spectrum antiviral activity for paramyxoviruses is modulated by biophysical properties of fusion inhibitory peptides. Sci Rep 2017, 7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mathieu C, Porotto M, Figueira TN, Horvat B, Moscona A: Fusion inhibitory lipopeptides engineered for prophylaxis of Nipah virus in primates. J Infect Dis 2018, 218:218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Outlaw VK, Bottom-Tanzer S, Kreitler DF, Gellman SH, Porotto M, Moscona A: Dual inhibition of human parainfluenza type 3 and respiratory syncytial virus infectivity with a single agent. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141:12648–12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Outlaw VK, Lemke JT, Zhu Y, Gellman SH, Porotto M, Moscona A: Structure-guided improvement of a dual HPIV3/RSV fusion inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc 2020, 142:2140–2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mathieu C, Huey D, Jurgens E, Welsch JC, DeVito I, Talekar A, Horvat B, Niewiesk S, Moscona A, Porotto M: Prevention of measles virus infection by intranasal delivery of fusion inhibitor peptides. J Virol 2015, 89:1143–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.••. Outlaw VK, Kreitler DF, Stelitano D, Porotto M, Moscona A, Gellman SH: Effects of single alpha-to-beta residue replacements on recognition of an extended segment in a viral fusion protein. ACS Infect Dis 2020, 6:2017–2022 These authors demonstrate lipopeptides extracted from the C-terminal heptad repeat domain of human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) inhibit infection by HPIV3 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

- 139.Russell CJ, Jardetzky TS, Lamb RA: Membrane fusion machines of paramyxoviruses: capture of intermediates of fusion. EMBO J 2001, 20:4024–4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Welsch JC, Talekar A, Mathieu C, Pessi A, Moscona A, Horvat B, Porotto M: Fatal measles virus infection prevented by brain-penetrant fusion inhibitors. J Virol 2013, 87:13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Figueira TN, Palermo LM, Veiga AS, Huey D, Alabi CA, Santos NC, Welsch JC, Mathieu C, Horvat B, Niewiesk S et al. : In vivo efficacy of measles virus fusion protein-derived peptides is modulated by the properties of self-assembly and membrane residence. J Virol 2017, 91:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gomes B, Santos NC, Porotto M: Biophysical properties and antiviral activities of measles fusion protein derived peptide conjugated with 25-hydroxycholesterol. Molecules 2017, 22:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Watanabe M, Hashimoto K, Abe Y, Kodama EN, Nabika R, Oishi S, Ohara S, Sato M, Kawasaki Y, Fujii N et al. : A novel peptide derived from the fusion protein heptad repeat inhibits replication of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis virus in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 2016, 11:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Chi XJ, Wang XJ, Wang CY, Cui XJ: In vitro and in vivo broad antiviral activity of peptides homologous to fusion glycoproteins of Newcastle disease virus and Marek’s disease virus. J Virol Methods 2014, 199:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.•. Barrett CT, Webb SR, Dutch RE: A hydrophobic target: using the paramyxovirus fusion protein transmembrane domain to modulate fusion protein stability. J Virol 2019, 93:15. These authors show that disruption of transmembrane-transmembrane (TM-TM) interactions significantly impacts the stability and function of viral fusion proteins.

- 146.Rapaport D, Ovadia M, Shai Y: A synthetic peptide corresponding to a conserved heptad repeat domain is a potent inhibitor of Sendai virus-cell fusion - an emerging similarity with functional domains of other viruses. EMBO J 1995, 14:5524–5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Kwong PD, Mascola JR: Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity 2012, 37:412–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Johnson JB, Aguilar HC, Lee B, Parks GD: Interactions of human complement with virus particles containing the Nipah virus glycoproteins. J Virol 2011, 85:5940–5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.•. Avanzato VA, Oguntuyo KY, Escalera-Zamudio M, Gutierrez B, Golden M, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Pryce R, Walter TS, Seow J, Doores KJ et al. : A structural basis for antibody-mediated neutralization of Nipah virus reveals a site of vulnerability at the fusion glycoprotein apex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:25057–25067 This paper structurally characterized neutralizing antibodies of paramyxoviruses and produced data supporting a model in which the membrane-distal region of the henipavirus F protein is the target used by the antibody-mediated immune response.

- 150.•. Bae SE, Kim SS, Moon ST, Cho YD, Lee H, Lee JY, Shin HY, Lee HJ, Kim YB: Construction of the safe neutralizing assay system using pseudotyped Nipah virus and G protein-specific monoclonal antibody. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 513:781–786 These authors present the development of a neutralization assay for Nipah virus and Hendra virus, which can be used to design therapeutics and further diagnosis methods.

- 151.Zhu ZY, Dimitrov AS, Bossart KN, Crameri G, Bishop KA, Choudhry V, Mungall BA, Feng YR, Choudhary A, Zhang MY et al. : Potent neutralization of Hendra and Nipah viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 2006, 80:891–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Bossart KN, Zhu Z, Middleton D, Klippel J, Crameri G, Bingham J, McEachern JA, Green D, Hancock TJ, Chan YP et al. : A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against lethal disease in a new ferret model of acute Nipah virus infection. PLoS Pathog 2009, 5:e1000642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Zhu Z, Bossart KN, Bishop KA, Crameri G, Dimitrov AS, McEachern JA, Feng Y, Middleton D, Wang LF, Broder Cc et al. : Exceptionally potent cross-reactive neutralization of Nipah and Hendra viruses by a human monoclonal antibody. J Infect Dis 2008, 197:846–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Geisbert TW, Mire CE, Geisbert JB, Chan YP, Agans KN, Feldmann F, Fenton Ka, Zhu Z, Dimitrov DS, Scott DP et al. : Therapeutic treatment of Nipah virus infection in nonhuman primates with a neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6:242ra282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Mire CE, Satterfield BA, Geisbert JB, Agans KN, Borisevich V, Yan LY, Chan YP, Cross RW, Fenton KA, Broder CC et al. : Pathogenic differences between Nipah virus Bangladesh and Malaysia strains in primates: implications for antibody therapy. Sci Rep 2016, 6:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bossart KN, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H, Zhu Z, Feldmann F, Geisbert JB, Yan L, Feng YR, Brining D, Scott D et al. : A neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects African green monkeys from Hendra virus challenge. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3:105ra103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.•. Dang HV, Chan YP, Park YJ, Snijder J, Da Silva SC, Vu B, Yan LY, Feng YR, Rockx B, Geisbert TW et al. : An antibody against the F glycoprotein inhibits Nipah and Hendra virus infections. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2019, 26:980–987 This study presents a potent monoclonal antibody that is capable of neutralizing both Nipah Virus and Hendra Virus.

- 158.Mousa JJ, Binshtein E, Human S, Fong RH, Alvarado G, Doranz BJ, Moore ML, Ohi MD, Crowe JE Jr: Human antibody recognition of antigenic site IV on Pneumovirus fusion proteins. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14:e1006837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]