Abstract

Background and Aims:

Patients undergoing evaluation for liver transplantation face heavy burdens of symptoms, healthcare utilization, and mortality. In other similarly ill populations, specialist palliative care has been shown to benefit patients, but specialist palliative care is infrequently utilized for liver transplantation patients. This project aims to describe the potential benefits of and barriers to specialist palliative care integration in the liver transplantation process.

Approach and Results:

We performed qualitative analysis of transcripts from provider focus groups followed by a community engagement studio of patients and caregivers. Focus groups consisted of 14 palliative care specialists and 10 hepatologists from 11 institutions across the US and Canada. The community engagement studio comprised patients and caregivers of patients either currently on the liver transplant wait list or recently post-transplant. The focus groups identified 19 elements of specialist palliative care that could benefit this patient population, including exploring patient’s illness understanding and expectations; comprehensive assessment of physical symptoms; discussing patient values; providing caregiver support; providing a safe space to discuss non-curative options; and anticipatory guidance about likely next steps. Identified barriers included role boundaries, differences in clinical cultures, limitations of time and staff, competing goals and priorities, misconceptions about palliative care, limited resources, changes in transplant status, and patient complexity. Community studio participants identified many of the same opportunities and barriers.

Conclusions:

This study found that hepatologists, palliative care specialists, patients, and caregivers identified areas of care for liver transplant patients that specialist palliative care can improve and address.

Keywords: advance care planning, end stage liver disease, cirrhosis, focus groups, community engagement studio

Palliative care specialists improve the quality of life of patients with serious illnesses by managing symptoms, attending to psychosocial and spiritual distress, and facilitating communication around treatment decisions and advance care planning. Specialist palliative care can improve both patient-reported and clinical outcomes for patients with malignancy, and there is a growing body of evidence showing similar benefit in serious illnesses such as end stage organ failure.(1–5) In the case of end-stage liver disease (ESLD), retrospective and small prospective studies have demonstrated benefits from specialist palliative care, and a large multi-center trial of a specialist palliative care intervention for patients with ESLD is ongoing.(6–8)

A challenge in providing specialist palliative care to patients with ESLD is determining how specialist palliative care could be integrated into the care of patients awaiting liver transplantation. Patients undergoing transplant evaluation and those on the wait list have burdensome symptoms and high risks for hospitalization and death, potentially making them excellent candidates for specialist palliative care.(9, 10) However, palliative care is not often part of the transplant paradigm, and evidence is needed on how best to integrate specialist palliative care into the care of those being evaluated for liver transplantation.

To fill this evidence gap, we conducted a series of focus groups with palliative care providers and transplant hepatologists. These focus groups discussed three key questions: how specialist palliative care could be brought into the care of patients awaiting transplant, what are the barriers to palliative care integration, and how specialist palliative care providers might optimally team with hepatologists to provide care for these patients. We then augmented these focus groups with a community engagement studio (CES) of liver transplant patients and caregivers.

Methods

After obtaining IRB approval, we used the investigators’ professional networks, to identify hepatologists and palliative care providers across 12 institutions interested in the intersection of hepatology and palliative care. Using email, the principal investigator (MCS) invited eligible participants to participate in an online focus group.

We conducted three focus groups with hepatologists and palliative care providers via Zoom. The principal investigators (MCS, MV) first presented to the group the elements of palliative care and potential ways that palliative care can fit into a longitudinal setting. (see Appendix A in the online supplement). The subsequent group discussion was led by a focus group moderator trained in qualitative methods (KB).

Using a semi-structured interview guide, the moderator asked open-ended questions along with follow-up questions for clarity and to facilitate detailed discussion. Following each focus group, participants were sent a link to a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) survey hosted at Vanderbilt University to rank elements of palliative care that were discussed in the focus groups.(11) Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed.

Qualitative data coding and analysis was managed by the Vanderbilt University Qualitative Research Core, led by a PhD-level psychologist (DS). Data coding and analysis was conducted by following the COREQ guidelines, an evidence-based qualitative methodology(12). A hierarchical coding system was developed and refined using the interview guide and a preliminary review of the transcripts (See Appendix B). Two experienced qualitative coders first established reliability in using the coding system on one of the transcripts. Coding was compared and discrepancies resolved. Coders then independently coded the remaining two transcripts. The transcripts, quotations, and codes were managed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and SPSS version 27.0.

Quotes were sorted by code, and an iterative inductive/deductive approach was used to identify themes and to make connections between themes(13–15). Deductively, we used knowledge of clinical care, health care systems, and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research(16, 17). Social Cognitive Theory was used to understand psychosocial beliefs, behaviors, and environments for patients(18, 19). Inductively, we used the coded quotes as a source of detailed understanding of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of palliative care and hepatology providers.

Following completion of this analysis, a CES with liver transplant patients and caregivers was conducted. The CES is a “structured program that facilitates project-specific input from community and patient stakeholders to enhance research design, implementation, and dissemination.”(20) In this case, patients and their caregivers with recent experiences of being evaluated for liver transplantation were the target stakeholders. CES staff recruited these stakeholders using a combination of social media, patient advocacy group lists, and contacts from prior studios. The stakeholders were convened via Zoom to hear a brief presentation on the results of our focus groups and then to discuss integrating palliative care into the liver transplantation process. CES staff not affiliated with the research team led discussions and generated summaries.

Results

Participants.

There were 24 participants from 11 institutions across the United States and Canada in the three focus groups. Fourteen of the participants were palliative care specialists and 10 were hepatologists. There were nine males and 15 females. Focus groups lasted an average of 1 hour 37 minutes.

Conceptual Framework.

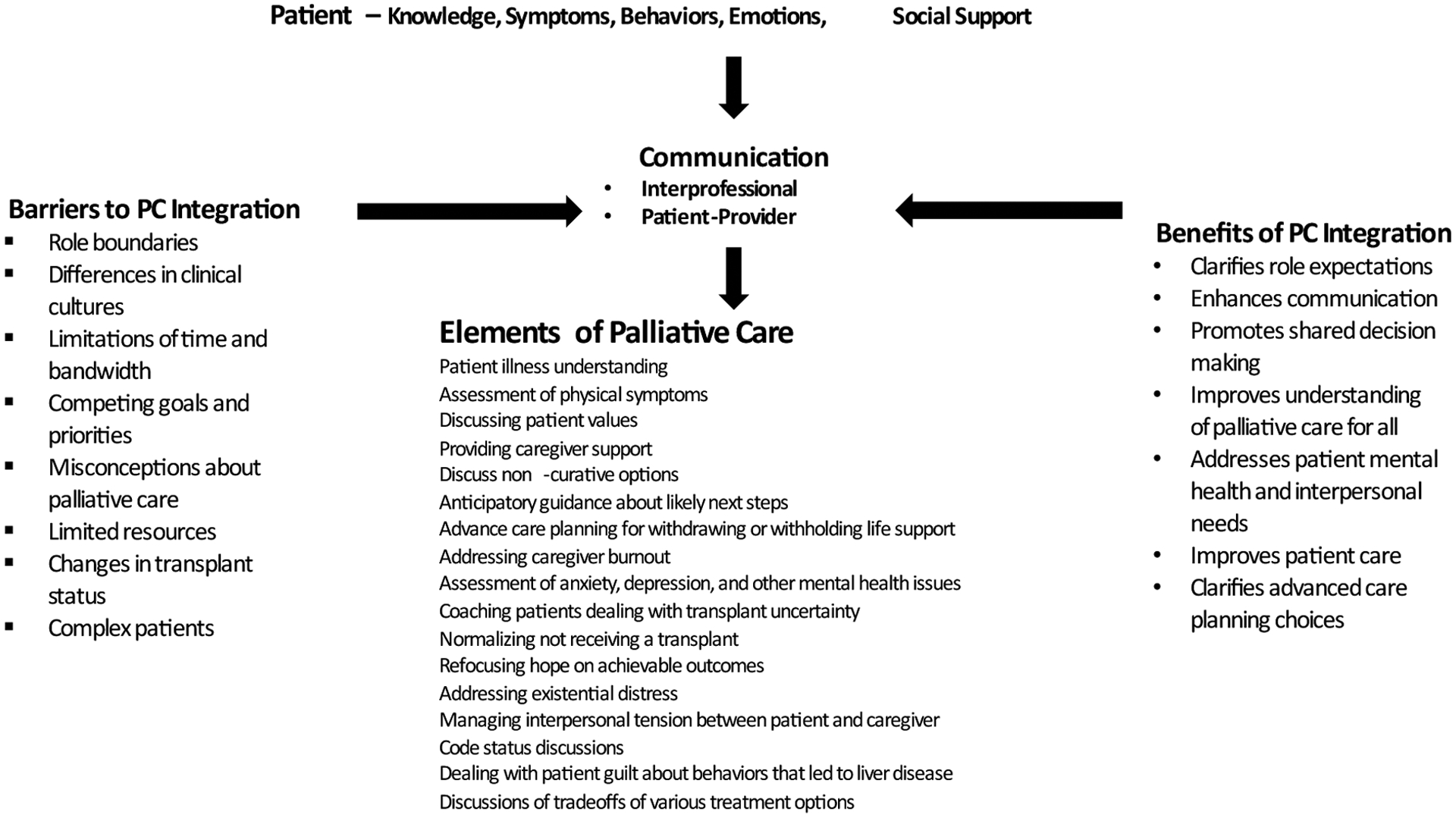

Figure 1 integrates the topics discussed in the focus groups into a framework for understanding the potential for integrating palliative care into the management of patient with severe liver disease. The center of the figure presents the elements of palliative care relevant for this patient population. Integration of palliative care into the treatment of patients with severe liver disease involves these specific tasks.

Figure 1:

Conceptual Framework to Understand Integration of Palliative Care into the Management of Severe Liver Disease

At the top of the figure, the box represents the patient along with the identified important patient-related themes: knowledge, symptoms, behaviors, emotions, and social support. The left of the figure presents themes identified as barriers to integration of the palliative care team into patient management. The right of the figure shows the potential benefits of integrating palliative care into the management of liver disease. The final element of Figure 1 is communication, both interprofessional communication and patient-provider communication. Communication is influenced by patient factors, barriers to palliative care integration, and the potential benefits of integration. These episodes of communication may promote methods for implementation of palliative care.

Elements of Palliative Care.

Table 1 includes the results of the short survey that was administered after the focus groups. Participants ranked the 19 elements of palliative care (identified in the focus groups) and were asked to check which ones they considered high priority. 20 of the 24 participants responded. Seventeen of the 19 elements of palliative care were checked as high priority by at least one participant, and Table 1 includes the percent selecting each of the 17 items as high priority along with quotations from palliative care and hepatology participants talking about each of the elements of palliative care. More than 40% of the group endorsed: 1) Exploring patient’s illness understanding and expectations; 2) Comprehensive assessment of physical symptoms; 3) Discussing patient values; 4) Providing caregiver support; 5) Providing a safe space to discuss non-curative options; and 6) Anticipatory guidance about likely next steps, major milestones or decision points that are upcoming.

Table 1:

Elements of Palliative Care

| Element of Palliative Care | Percent Priority | Palliative Care Quote | Hepatology Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploring patient’s illness understanding and expectations | 75% |

|

|

| Comprehensive assessment of physical symptoms | 55% |

|

|

| Discussing patient values | 55% |

|

|

| Providing caregiver support | 45% |

|

|

| Providing a safe space to discuss non-curative options | 40% |

|

|

| Anticipatory guidance about likely next steps, major milestones or decision points that are upcoming | 40% |

|

|

| Addressing caregiver burnout | 35% |

|

|

| Advance care planning for withdrawing or withholding life support in the future | 35% |

|

|

| Assessment of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues | 30% |

|

|

| Normalizing the possibility of not receiving a transplant | 25% |

|

|

| Coaching patients on how to deal with the uncertainty of whether or not they will get transplanted | 25% |

|

|

| Addressing existential distress | 20% |

|

|

| Refocusing hope on achievable outcomes | 20% |

|

|

| Code status discussions | 15% |

|

|

| Managing interpersonal tension between patient and caregiver | 15% |

|

|

| Dealing with patient guilt about behaviors that led to liver disease, especially substance use | 10% |

|

|

| Engage in nuanced discussions of tradeoffs of various treatment options | 5% |

|

|

The Patient.

Focus groups identified patient attributes that affect health care interactions: knowledge, symptoms, behaviors, emotions, social support. Important aspects of knowledge were the patient’s understanding of their disease and prognosis. Symptoms of liver disease were a frequent subject in the focus group discussions. Important behaviors that were identified included minimizing substance use patterns, self-managing symptoms, maintaining social responsibilities, and attention to nutrition, rest, and physical activity. Coping with liver failure includes a range of emotions including anxiety, depression, guilt, anger, and shame. Social support, both instrumental and emotional, are important for persons with liver disease. Table 2 presents quotes from palliative care and hepatology participants related to knowledge, symptoms, behaviors, emotions, and social support.

Table 2:

Qualitative Themes Describing the Influence of Patient Characteristics

| Patient Characteristics | Palliative Care Quote | Hepatology Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge |

|

|

| Symptoms |

|

|

| Behaviors |

|

|

| Emotions |

|

|

| Social Support |

|

|

| Resources |

|

|

Barriers to Palliative Care Integration.

We identified 8 major themes associated with barriers to integrating palliative care into the management of patients with severe liver disease (Table 3). Four barriers were focused on the interactions between the liver transplant team and the palliative care team: 1) overlap between the roles of the palliative care team and the hepatology team resulting in uncoordinated health care; 2) differing cultures between palliative care and transplant teams; 3) limitations of time and staff which make it difficult to attend to palliative care issues; and 4) competing goals and priorities, such as the best time to introduce the palliative care team, how much time each team should spend with patients, the extent to which palliative care should be involved in symptom management and if so which symptoms, and how to deal with overlap of services offered by both teams such as consults with psychologists, social workers, or dietitians.

Table 3:

Barriers to Integrating Palliative Care into Liver Disease Management

| Barriers | Palliative Care Quote | Hepatology Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Role boundaries |

|

|

| Differences in clinical cultures |

|

|

| Time and Staff limitations |

|

|

| Competing goals and priorities |

|

|

| Misconceptions about palliative care |

|

|

| Limited Resources |

|

|

| Change in transplant status |

|

|

| Complex patients |

|

|

Two barriers applied to both clinicians and patients. Both groups may have misconceptions about why a palliative care consult has been requested for transplant evaluation candidates, and what are the things they are supposed to do or expect. In addition, limited resources also affect patients and providers. Providers identified lack of physical space in the clinic as a resource limitation along with lack of reimbursement for services that focus on emotional and psychosocial needs. Patients and caregivers also face limitations in the resources available at home.

The final two barriers are related primarily to patient status. Being removed from the transplant eligibility list is a major challenge for patients and their caregivers that can negatively affect their physical wellbeing and change their relationship with the healthcare team. Patients with complex symptoms and comorbidities also create challenges for the care team. These complex patients may have needs that cannot be fully met by the transplant surgeons and hepatologists.

Benefits of Palliative Care integration.

We identified seven major themes related to the benefits of integrating palliative care into the treatment of patients with advanced liver diseases (Table 4).

Table 4:

Benefits of Integrating Palliative Care into the Management of Sever Liver Disease

| Benefits | Palliative Care Quote | Hepatology Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Clarifies role expectations |

|

|

| Enhances communication |

|

|

| Promotes shared decision making |

|

|

| Improves understanding of palliative care for all |

|

|

| Addresses patient mental health and interpersonal needs |

|

|

| Improves patient care |

|

|

| Clarifies advance care planning choices |

|

|

Proactively, palliative care providers can work to clarify role expectations and by doing so provide services not currently provided by the hepatology team.

Interprofessional and patient-provider communication around the management of symptoms or psychosocial issues is another potential benefit of integrating palliative care into patient management. The expertise of palliative care clinicians around issues of emotional adjustment and quality of life can inform hepatologists about how their patients are doing.

Integration of palliative care can also enhance shared decision making. The palliative care team may be able to help patients better articulate their needs and preferences thus allowing them to have more input into shared decision-making. The extra time spent with palliative care providers can help patients better understand their values and needs and prepare them for making decisions should their symptoms worsen or should they be de-listed.

Integration of palliative care could reduce misconceptions and misunderstandings about what palliative care is and how the palliative care team can meet the needs of patients.

The integration of palliative care was seen as having the direct benefit of addressing a patient’s mental health, emotional, and interpersonal needs. Palliative care providers are attuned not only to the common experiences of anxiety and depression, but they are also able to address the more existential fear of dying. This level of support is especially important for patients whose condition worsens to the point of having to be de-listed.

The overall quality of patient care might be improved through integration with the palliative care team. This was seen as especially important when a patient’s medical status changes over time which can introduce new emotional and interpersonal challenges. Having clinicians who can follow patients from evaluation to post transplant or to hospice care is an advantage of integrating the palliative care team.

Palliative care could help patients with advance care planning choices. Palliative care specialists have considerable experience with helping patients with advance care planning, especially when the can have an ongoing relationship over time.

CES

Six stakeholders (4 patients and 2 caregivers) participated in the CES, of whom 4 were female and 2 were male. The stakeholders agreed integrating palliative care into the liver transplantation process would be helpful, especially to deal with symptom control and to discuss prognosis, set expectations, and plan for the future, including end-of-life. Stakeholders also noted negative perceptions about palliative care would be a barrier to integration, but felt that with an appropriate introduction palliative care would be accepted and welcomed by both patients and caregivers. The stakeholders agreed that introducing palliative care early in the transplant evaluation process would be most helpful.

The stakeholders also presented needs for supportive care not discussed in much depth in the provider focus groups. They suggested palliative care integration could include informing patients of resources, especially electronic resources, to connect with other similar patients and to gather information on liver disease and liver transplantation. They expressed a desire for information and resources on financial toxicity from liver disease and transplantation. Finally, the stakeholders emphasized an ongoing role for support from palliative care after transplantation to help these patients navigate post-transplant complications, mental health concerns, and overall health management.

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge to elicit the expert opinion of hepatologists and palliative care clinicians on how to integrate specialist palliative care into the liver transplant evaluation and wait-listing process. Prior work has suggested that patients benefit from including specialist palliative care in this treatment paradigm and that specialist palliative care is underutilized for these patients.(6, 21) These focus groups provide insight into how to integrate specialist palliative care into these patients’ management. Additionally, the focus groups illuminate the potential opportunities and pitfalls for such integration from both specialties.

Surveys of transplant physicians have revealed reluctance to consult specialist palliative care for wait-list patients despite widespread recognition that specialist palliative care could help many of these patients.(22–24) Several of the hepatologists in our focus groups reported misgivings about involving specialist palliative care clinicians in the care of wait-list patients. These misgivings included concerns about how patients would perceive these providers and how specialist palliative care involvement could create confusion about who manages which problems or may give patients messages that conflict with the message of the transplant team. Throughout the course of the focus groups, as the hepatologists and palliative care clinicians spoke more about how to integrate the two and how the palliative care clinicians could help, we observed increased enthusiasm for specialist palliative care from the hepatologists. By the end of each of the focus groups, the hepatologists were generally as enthusiastic as the palliative care clinicians for integrating specialist palliative care. This experience suggests dialogue among palliative care clinicians and hepatologists is a powerful means of increasing hepatologists’ openness to including specialist palliative care in the management of wait-list patients.

Transplant listing has been associated with more aggressive end-of-life care compared with non-listed ESLD patients.(21, 25) A recent qualitative study found numerous barriers to effective advance care planning for ESLD patients at transplant centers.(26) Not surprisingly, our focus groups identified one role of specialist palliative care providers would be assisting patients in advance care planning and helping patients who do not receive transplantation to manage their end of life care. Discussions centered around the importance of this aspect of palliative care and how it would fill a vital need in the care of these patients. However, several important points of caution were discussed, including the need to make sure advance care planning did not unduly distress patients and their families and the importance of palliative care specialists’ careful coordination with the transplantation team to make sure patients receive consistent information about their prognoses. Clearly, assisting with advance care planning would be an important role of the palliative care clinician for transplant wait-list patients, but would require a great deal of sensitivity to timing and wording of these discussions so that they do not disrupt the therapeutic alliance between the patient and the transplant team.

These provider perspectives in many ways matched those of the patient and caregivers who participated in the CES. Both CES stakeholders and the provider focus groups shared enthusiasm for the possibilities of palliative care integration for improved symptom management, advance care planning, and communication. The CES stakeholders also noted patient perceptions of palliative care to end of life care as a potentially surmountable barrier to palliative care integration. In addition, the stakeholders identified other supportive care needs amenable to palliative care not discussed by the provider focus groups: dealing with financial toxicity, connecting to information and peer resources, and post-transplantation support.

This qualitative study has several limitations. Although focus group participants were recruited nationally, we cannot guarantee that these participants were representative of the wider hepatology and palliative care communities. Nevertheless, with this number and diversity of participants, we expect that their contributions capture the range of opinions in these larger communities. Both palliative care and transplantation are inherently multidisciplinary, but this project focused on just one type of caregiver from each of these multidisciplinary fields. Further work is needed to receive input from the stakeholders from other disciplines within transplantation (such as transplant surgeons, transplant coordinators, transplant social workers, and transplant psychologists) and within palliative care (such as chaplains and palliative care social workers). The CES was similarly nationally recruited, but not necessarily representative of the wider population of liver transplant patients and caregivers. The CES process also does not allow for the granular analysis of transcripts that the focus groups allowed, which means themes might have been missed in the summary prepared by the CES staff. Future qualitative research on patient and caregiver perspectives on the role of palliative care would be helpful to provide a more thorough understanding of their perspectives. The input from patients or caregivers who were de-listed or deemed ineligible for transplant would be especially important in future research as the CES was not able to recruit any of these stakeholders.

Despite these limitations, this study provides important preliminary information on how to integrate specialist palliative care into the management of ESLD patients awaiting liver transplantation. These results can help leaders design clinical programs of palliative care for this population. These results could also inform the content of specialist palliative care interventions to be tested in the transplant wait list population. These data are an early step in effectively addressing the demonstrated palliative care needs of these patients.

Supplementary Material

Financial Support:

Dr. Shinall was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (K76AG068436). Dr. Schlundt and Ms. Bonnet were supported by a grant from the National Center to Advance Translational Science (UL1TR002243). Dr. Verma was supported by a grant from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PLC1609036714).

Abbreviations

- ESLD

End-stage Liver Disease

- CES

Community Engagement Studio

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1721–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidebottom AC, Jorgenson A, Richards H, Kirven J, Sillah A. Inpatient palliative care for patients with acute heart failure: outcomes from a randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong FKY, Ng AYM, Lee PH, Lam P-T, Ng JSC, Ng NHY, et al. Effects of a transitional palliative care model on patients with end-stage heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2016;102(14):1100–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumann AJ, Wheeler DS, James M, Turner R, Siegel A, Navarro VJ. Benefit of Early Palliative Care Intervention in End-Stage Liver Disease Patients Awaiting Liver Transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(6):882–6 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinall MC, Jr., Karlekar M, Martin S, Gatto CL, Misra S, Chung CY, et al. COMPASS: A Pilot Trial of an Early Palliative Care Intervention for Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(4):614–22 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verma M, Kosinski AS, Volk ML, Taddei T, Ramchandran K, Bakitas M, et al. Introducing Palliative Care within the Treatment of End-Stage Liver Disease: The Study Protocol of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(S1):34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng JK, Hepgul N, Higginson IJ, Gao W. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2019;33(1):24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin JB, Sinclair M, Rahimi RS, Tapper EB, Lai JC. Women on the liver transplantation waitlist are at increased risk of hospitalization compared to men. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(8):980–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azungah T Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bingham AJ, Witkowsky P. Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Qualitative Analysis. In: Vandover C, Mihas P, Saldana J, editor. Analyzing and Interpreting Qualitative Research: After the Interview. Thousand Oaks, Ca.: Sage; 2021. p. 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjora A Qualitative research as stepwise-deductive induction: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science. 2009;4(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implementation Science. 2015;11(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):248–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mischel W Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological review. 1973;80(4):252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, Boone LR, Schlundt DG, Mouton CP, et al. Community Engagement Studios: A Structured Approach to Obtaining Meaningful Input From Stakeholders to Inform Research. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1646–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ufere NN, Halford JL, Caldwell J, Jang MY, Bhatt S, Donlan J, et al. Health Care Utilization and End-of-Life Care Outcomes for Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis Based on Transplant Candidacy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(3):590–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esteban JPG, Rein L, Szabo A, Saeian K, Rhodes M, Marks S. Attitudes of Liver and Palliative Care Clinicians toward Specialist Palliative Care Consultation for Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(7):804–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ufere NN, Donlan J, Waldman L, Patel A, Dienstag JL, Friedman LS, et al. Physicians’ Perspectives on Palliative Care for Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease: A National Survey Study. Liver Transpl. 2019;25(6):859–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck KR, Pantilat SZ, O’Riordan DL, Peters MG. Use of Palliative Care Consultation for Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease: Survey of Liver Transplant Service Providers. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(8):836–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walling AM, Asch SM, Lorenz KA, Wenger NS. Impact of consideration of transplantation on end-of-life care for patients during a terminal hospitalization. Transplantation. 2013;95(4):641–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel AA, Ryan GW, Tisnado D, Chuang E, Walling AM, Saab S, et al. Deficits in Advance Care Planning for Patients With Decompensated Cirrhosis at Liver Transplant Centers. JAMA Intern Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.