Abstract

Progress in therapy has made survival into adulthood a reality for most children, adolescents, and young adults with a cancer diagnosis today. Notably, this growing population remains vulnerable to a variety of long-term therapy-related sequelae. Systematic ongoing follow-up of these patients is, therefore, important to provide for early detection of and intervention for potentially serious late-onset complications. In addition, health counseling and promotion of healthy lifestyles are important aspects of long-term follow-up care to promote risk reduction for physical and emotional health problems that commonly present during adulthood. Both general and subspecialty health care providers are playing an increasingly important role in the ongoing care of childhood cancer survivors, beyond the routine preventive care, health supervision, and anticipatory guidance provided to all patients. This report is based on the guidelines that have been developed by the Children’s Oncology Group to facilitate comprehensive long-term follow-up of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors (www.survivorshipguidelines.org).

BACKGROUND INFORMATION

Cancer is diagnosed in approximately 20 000 children and 80 000 adolescents and young adults annually in the United States.1 Before 1970, almost all children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer died from their primary disease. However, rapid improvements in multimodal treatment regimens (chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, and immunotherapy), coupled with aggressive supportive-care regimens, have resulted in survival rates that continue to increase. The current estimated 5-year overall survival rate for childhood, adolescent, and young adult malignancies exceeds 80%,2 which translates into increasing numbers of long-term survivors, now estimated to approach 500 000 in the United States, who may seek ongoing care from community primary and subspecialty providers.3 The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), the largest and most extensively characterized cohort of 5-year childhood cancer survivors in North America, reported that survivors receive most of their care from primary care providers.4 Furthermore, the proportion of survivors reporting survivor-focused care that includes regular risk-based surveillance and prevention strategies related to their prior cancer and its treatment decreases with increasing time from cancer diagnosis. Thus, primary care providers (pediatricians, family practitioners, internists, practitioners trained in internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds), and advanced practice providers) are likely to have an increasingly vital role in caring for this rapidly growing population.

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM

Cancer and its treatment may result in a variety of physical and psychosocial effects that predispose long-term survivors to excess morbidity and early mortality when compared with the general population.5-10 Virtually every organ system can be affected by the chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, and/or immunotherapy required to achieve cure. Late complications of treatment may include problems with organ function, growth and development, neurocognitive function and academic achievement, and the potential for additional cancers. Cancer and its treatment also have psychosocial consequences that may adversely affect family/peer relationships, educational attainment (both formal and practical knowledge gained from real-world experience), vocational and employment opportunities, and insurance and health care access. In addition, survivors may experience troubling body image changes or suffer from chronic symptoms (eg, fatigue, dyssomnia, pain) that adversely affect emotional health and quality of life. A young person’s and family’s lives are forever changed when touched by the cancer experience, and it is critical to provide rehabilitation services to survivors who highly value good health and unrestricted performance status. Equally important is reaching out to young adult survivors who may be separated from their families and face more challenges in adhering to healthy lifestyles and accessing health care services.

Late effects after childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer are common. Two of every 3 childhood cancer survivors will develop at least 1 late-onset therapy-related complication; in 1 of every 4 cases, the complication will be severe or life threatening.6,11 Among clinically ascertained cohorts, the prevalence of late effects is higher because of the subclinical and undiagnosed conditions detected by screening and surveillance measures.8 Childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors, therefore, require ongoing comprehensive long-term follow-up care to optimize long-term outcomes by successfully monitoring for and treating the late effects that may occur as a result of previous cancer therapies as well as anticipatory guidance and health promotion efforts addressing primary and secondary prevention of chronic disease. Access to care and services that address health risks predisposed by cancer and its treatment can optimize achievement of independent living, employment, and insurance access, which is particularly important for a population at risk of multimorbidity.

Because health risks associated with cancer are unique to the age at treatment and specific therapeutic modality, it is important that follow-up evaluations and health screening be individualized based on treatment history. To facilitate comprehensive and systematic follow-up of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) organized exposure-based health screening guidelines. This clinical report presents pediatricians and other health care professionals with guidance for providing high-quality long-term follow-up care and health supervision for survivors of pediatric, adolescent, and young adult malignancies by incorporating long-term follow-up guidelines developed by the COG into their practice12 and by maintaining ongoing interaction with oncology subspecialists to facilitate communication regarding any changes in follow-up recommendations specific to the cancer survivors under their care.

METHODS: DEVELOPMENT OF LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP GUIDELINES

The COG is a cooperative clinical trials group supported by the National Cancer Institute with more than 200 member institutions. In January 2002, at the request of the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine), a multidisciplinary panel within COG initiated the process of developing comprehensive risk-based, exposure-related recommendations for screening and management of late treatment-related complications potentially resulting from therapy for childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers. The resulting comprehensive resource, the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers (COG LTFU Guidelines),12 is designed to raise awareness of the risk of late treatment-related sequelae to facilitate early identification and intervention for these complications, standardize follow-up care, improve quality of life, and provide guidance to health care professionals, including pediatricians, who supervise the ongoing care of young cancer survivors.

The COG LTFU Guidelines are designed for use in asymptomatic childhood, adolescent, and young adult survivors presenting for routine health maintenance at least 2 years after completion of cancer-directed therapy (eg, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy) whether the survivor is receiving care in a pediatric cancer, a specialized adolescent-young adult program, an adult-focused oncology program, a long-term follow-up program, or community primary care practice. The guidelines are not designed for primary cancer-related surveillance, which is an important component of survivorship care that generally continues under the guidance of the treating oncologist throughout the period when the patient remains at highest risk of relapse but may ultimately be transferred to community primary care providers (pediatricians, family physicians, internists, practitioners trained in internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds), and advanced practice providers). This period of risk varies depending on diagnosis and is generally highest in the first few years, with the risk decreasing significantly as time from diagnosis lengthens.

COG LTFU Guidelines Methodology

The methodology used in developing these guidelines has been described elsewhere.12 Briefly, evidence for development of the COG LTFU Guidelines was collected by conducting a complete search of the medical literature for the previous 20 years via MEDLINE. A panel of experts in the late effects of childhood and adolescent cancer treatment then reviewed and scored the guidelines using a modified version of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network “Categories of Consensus” system. Task forces within COG monitor the literature on an ongoing basis and provide recommendations for guideline revision as new information becomes available. These task forces include general pediatricians and other primary care providers to incorporate a primary care perspective and facilitate effective dissemination of these guidelines into the “real-world” setting.

The COG LTFU Guidelines are updated on an every 5-year cycle to ensure that recommendations reflect currently available evidence published in peer-reviewed journals. Multidisciplinary system-based task forces (>160 COG members) are responsible for monitoring the late effects literature, performing systematic searches, summarizing and evaluating the evidence and presenting recommendations for guideline revisions to a multidisciplinary panel of late effects experts. Task force activities involve senior leaders who mentor early career physicians and other health care professionals in acquiring the leadership and methodologic skills to sustain guideline activities as a task force chair or member. A formal training program has been developed that includes a series of webinars (available live and recorded/archived on COG website) and one-on-one mentorship activities with COG LTFU Guideline task force chairs and leadership.

COG LTFU Guidelines Version 5.0

The COG LTFU Guidelines is an online resource (available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org). The COG LTFU Guidelines Version 5.0 features 165 sections of risk-based exposure-related clinical practice guidelines for screening and management of late effects resulting from treatment for pediatric malignancies related to any cancer experience, blood product transfusion, specific chemotherapeutic agents, radiation exposures to targeted tissues/organs, hematopoietic cell transplantation (as well as transplantation with chronic graft-versus-host disease), specific surgical procedures, and adult-onset cancer screening for standard and high-risk groups. Version 5.0 features key changes including guideline recommendations and content based on new research related to thresholds and risk factors for cardiovascular toxicity following treatment with anthracycline chemotherapy and chest radiation, prevalence data regarding pregnancy associated cardiomyopathy, prevalence data related to occurrence of multiple hormonal deficiencies among survivors treated with cranial irradiation, and improved risk estimates about the contribution of radiation dose and treatment volume to risk of developing subsequent breast and colorectal carcinomas. In addition, previous radiation threshold doses linked to specific screening recommendations have been removed for all but 5 sections, because organ dosimetry is often not available to guide implementation of screening. This approach provides uniform screening recommendations for survivors with target organs receiving radiation exposure at any dose, which the expert panel agreed was reasonable considering that the screening recommendations focus primarily on history and physical examination, with only limited recommendation for laboratory or other diagnostic evaluations. Finally, the guideline format has been substantially simplified to provide clinical users with concise presentation of specific therapeutic exposures, potential late effects, screening recommendations, and relevant counseling and educational resources for the provider and survivors. Each guideline section features a brief summary of patient characteristics (eg, age, sex, pre-existing or comorbid conditions, behavioral, etc) that have been reported to modify the risk of specific late effects and cancer- and treatment-related factors that are important for consideration in the delivery of personalized survivor-focused care,13 clarifying information about the potential late effect or surveillance recommendations, and representative references. The simplified guideline content is also featured in the Passport for Care, a web-based resource that facilitates the generation of personalized surveillance plan based on the COG LTFU Guidelines available at https://cancersurvivor.passportforcare.org/.14

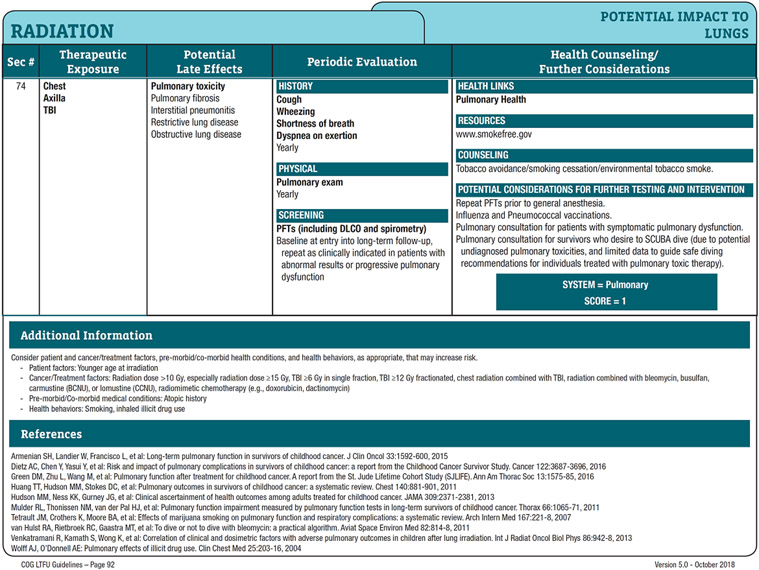

This revised clinical report, “Long-term Follow-up Care for Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors,” has been updated to enhance awareness among health care providers about the content and scope of this comprehensive resource and offer time efficient methods of using the large amount of valuable information in the COG LTFU Guidelines to streamline the provision of care for these survivors. Table 1 provides a summary of selected treatment exposures and associated late effects by organ system as outlined in the COG LTFU Guidelines. Fig 1 provides an example of an exposure-based recommendation from the COG LTFU Guidelines. Full details about 155 cancer treatment-related potential biomedical and psychosocial late effects, surveillance recommendations, patient educational materials and other resources and websites pertinent to the specific health risks are available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org.

Table 1.

Potential Late Effects of Selected Therapeutic Interventions for Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer by Organ

| Organ | Therapeutic Exposures | Potential Late Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | Radiation Therapy Field(s) | Surgery | ||

| Any organ/tissue | All fields | Subsequent neoplasms (skin, breast, thyroid, brain, colon, bone, soft tissues, etc) | ||

| Bones | Corticosteroids Methotrexate |

-- | -- | Osteopenia/osteoporosis Osteonecrosis |

| Bones/soft tissues | -- | All fields | -- | Reduced/uneven growth Reduced function/mobility Hypoplasia, fibrosis Radiation-induced fracture Scoliosis/kyphosis (trunk fields only) |

| Bones/soft tissues | -- | -- | Amputation Limb sparing |

Reduced/uneven growth Reduced function/mobility Chronic pain |

| Bowel | -- | Abdomen1 Pelvis Spine (lumbar, sacral, whole) |

Laparotomy Pelvic/spinal surgery |

Chronic enterocolitis GI tract strictures Adhesions/obstruction Fecal incontinence |

| Bladder | Cyclophosphamide Ifosfamide |

Pelvic Spine (sacral, whole) |

Spinal surgery Cystectomy |

Hemorrhagic cystitis Bladder fibrosis Dysfunctional voiding Neurogenic bladder |

| Brain (cognitive function) | Methotrexate (intrathecal administration or IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) Cytarabine (IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) |

Head/Brain Total body |

Neurosurgery | Neurocognitive deficits (executive function, attention, memory, processing speed, visual motor integration) Learning deficits Diminished intelligence quotient |

| Brain (motor and sensory function) | Methotrexate, cytarabine (intrathecal administration or IV doses ≥1000 mg/m2) | Head/Brain | Neurosurgery | Cranial nerve dysfunction Motor and sensory deficits including paralysis Cerebellar dysfunction Seizures |

| Brain (hypothalamic-pituitary axis) | -- | Head/Brain Total body |

Neurosurgery | Growth hormone deficiency Precocious puberty (altered gonadotropin secretion) Gonadotropin insufficiency Central adrenal insufficiency (XRT ≥30 Gy) |

| Brain (vascular) | -- | Head/Brain | Neurosurgery | Cerebrovascular complications (stroke, moya moya, occlusive cerebral vasculopathy) |

| Breast | -- | Chest Axilla Total body |

-- | Breast tissue hypoplasia Breast cancer |

| Ear | Cisplatin Carboplatin (in myeloablative doses only) |

Head/Brain | -- | Sensorineural hearing loss (XRT doses ≥30 Gy) Conductive hearing loss (XRT only) Eustachian tube dysfunction (XRT only) |

| Esophagus | Neck Chest Abdomen Spine (cervical, thoracic, whole) |

Esophageal stricture | ||

| Eye | Busulfan Corticosteroids |

Head/Brain Total body |

Neurosurgery | Cataracts Retinopathy (XRT only) Ocular nerve palsy (neurosurgery only) |

| Heart | Anthracycline agents (eg, doxorubicin, daunorubicin) | Chest Abdomen Spine (thoracic, whole) Total body |

-- | Cardiomyopathy Congestive heart failure Arrhythmia Subclinical left ventricular dysfunction XRT only:

|

| Kidney | Cisplatin Carboplatin Ifosfamide Methotrexate |

Abdomen Total body |

Nephrectomy | Glomerular toxicity Tubular dysfunction Renal insufficiency Hypertension |

| Liver/biliary tract | Antimetabolites (mercaptopurine, thioguanine, methotrexate) | Abdomen | -- | Hepatic dysfunction Veno-occlusive disease Hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis Cholelithiasis |

| Lungs | Bleomycin Busulfan Carmustine Lomustine |

Chest Axilla Total body |

Pulmonary resection Lobectomy |

Pulmonary fibrosis Interstitial pneumonitis Restrictive/obstructive lung disease Pulmonary dysfunction |

| Nerves (peripheral) | Plant alkaloids (vincristine, vinblastine) Cisplatin, carboplatin |

-- | Spinal surgery | Peripheral sensory or motor neuropathy |

| Ovary | Alkylating agents (eg, busulfan, carmustine, lomustine, cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine, melphalan, procarbazine) | Pelvis Spine (sacral, whole) Total body |

Oophorectomy | Ovarian hormone insufficiency Delayed/arrested puberty Premature menopause Diminished ovarian reserve Infertility Uterine vascular insufficiency (XRT only) Vaginal fibrosis/stenosis (XRT only) |

| Skin | -- | All fields | -- | Permanent alopecia Altered skin pigmentation Telangiectasias Fibrosis Dysplastic nevi |

| Spleen | Abdomen (doses ≥40 Gy) | Splenectomy | Life-threatening infection related to functional or anatomic aspleniaa | |

| Teeth | Any chemotherapy before development of secondary dentition | Head/Brain Neck Spine (cervical, whole) Total body |

-- | Dental maldevelopment (tooth/root agenesis, microdontia, enamel dysplasia) Periodontal disease Dental caries Osteoradionecrosis (XRT doses ≥40 Gy) |

| Testes | Alkylating agents (eg, busulfan, carmustine, lomustine, cyclophosphamide, mechlorethamine, melphalan, procarbazine) | Testes Total body |

Pelvic/spinal surgery Orchiectomy |

Testosterone insufficiency Delayed/arrested puberty Impaired spermatogenesis Infertility Erectile/ejaculatory dysfunction |

| Thyroid | Head/Brain Neck Spine (cervical, whole) Total body |

Thyroidectomy | Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism Thyroid nodules (XRT only) |

|

Gy indicates Gray; IV, intravenous; XRT, radiation therapy.

Note: This table briefly summarizes potential late effects for selected therapeutic exposures only; the complete set of Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group, including screening recommendations, is available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org. In addition to organ/tissue-specific late effects, any cancer experience may increase the risk of adverse psychosocial and quality-of-life outcomes summarized at www.survivorshipguidelines.org (sections 1-6).

Functional asplenia can also occur as a consequence of active chronic graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplant

Fig 1. Example of an exposure-based recommendation from the COG LTFU Guidelines.

(From the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 5.0, October 2018, used with permission).

CLINICAL APPLICATION OF COG LTFU GUIDELINES

Malignancies presenting in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood encompass a spectrum of diverse histologic subtypes that have been managed with heterogeneous and evolving treatment approaches. Over the last 20 years, treatment protocols for localized and biologically favorable presentations of cancers have been modified substantially to reduce the risk of therapy-related complications. Conversely, therapy has been intensified for many advanced and biologically unfavorable cancers to optimize disease control and long-term survival. Thus, not all childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors have similar risks of late treatment effects, including those with the same diagnosis. Importantly, cancer treatment strategies continue to evolve as a result of discoveries in cancer biology and therapeutics as well as improved understanding about late effects.

Evaluating a Survivor’s Risk of Late Effects

In general, the risk of late effects is directly proportional to the intensity of therapy required to achieve and maintain disease control. Longer treatment with higher cumulative doses of chemotherapy and radiation, multimodal therapy, and relapse therapy increase the risk of late treatment effects. Specifically, the risk of late effects is related to the type and intensity of cancer therapy (eg, surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) and the patient’s age at the time of treatment. Chemotherapy most often results in acute effects, some of which may persist and cause problems as the survivor ages. Many radiation-related effects on growth and development, organ function, and carcinogenesis may not manifest until many years after cancer treatment. The young child is especially at risk of delayed treatment toxicity affecting linear growth, skeletal maturation, intellectual function, sexual development, and organ function. It is important that health care professionals who provide care across a continuum of developmental periods also recognize that childhood cancer survivors face unique vulnerabilities related to their age at diagnosis and treatment. Table 2 provides examples of clinical and treatment factors that influence the risk of specific late effects after treatment for a common childhood (acute lymphoblastic leukemia) and adolescent-young adult (osteosarcoma) cancer. The diversity and potential interplay of factors contributing to cancer-related morbidity are further illustrated in the case presentations summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Clinical and Treatment Factors Influencing Risk of Late Effects after Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer

| Factor | Reason | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of cancer | Age at diagnosis influences vulnerability to specific cancer treatment-related complications. | Young children experience a higher risk of neurocognitive deficits following cranial irradiation compared to adolescents.36 Young girls, compared with older adolescents, are less vulnerable to alkylating agent-induced ovarian insufficiency because of their larger primordial follicular pool.37 |

| Sex | The risk of some cancer treatment-related toxicities varies by sex. | Boys are more sensitive to gonadal injury following alkylating agents compared with girls.38 Breast cancer risk in women treated with chest radiation is comparable to BRCA mutation carriers and warrants early initiation of breast cancer surveillance.39 |

| Tissues and organs involved by cancer | Malignant infiltration of normal tissues may result in permanent deficits. | Survivors of central nervous system tumors may have long-term neurologic, neurosensory, or neuroendocrine late effects related to tumor location.40 Survivors of retroperitoneal tumors (eg, Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma) experience increase risk of scoliosis.41 |

| Surgery | Specific surgical procedures may be associated with increased risks for chronic symptoms or health conditions. | Sarcoma survivors treated with limb-sparing surgeries may have chronic pain or performance restrictions.42 Survivors of Wilms tumor have an increased risk of hypertension after nephrectomy.43 |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Chemotherapeutic agents have unique organ/tissue toxicity profiles, many of which are dose-related. Knowledge of specific chemotherapy agents received is needed to determine type and magnitude of late effects risk. | Anthracyclines are associated with increased risk of cardiomyopathy.44 Cisplatin increases the risk of hearing loss and renal dysfunction.45 Alkylating agents increase the risk of gonadal injury and infertility.37 |

| Radiation therapy | The potential for radiation injury to normal tissues is directly related to the organs and tissues in the radiation treatment field and dose delivered. | Hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA) dysfunction is common after cranial radiation. HPA systems affected show relationships to dose with growth hormone deficiency presenting at much lower dose exposure compared to gonadotropin deficiency.46 |

| Hematopoietic cell transplant | In addition to risks associated with chemotherapy and radiation, survivors may experience health risks associated with immune system alterations following hematopoietic cell transplantation. | Survivors who are transplant recipients have higher risks of subsequent malignancies involving epithelial and mucosal tissues.47 |

| Pre-existing/comorbid conditions | Common comorbid conditions can exacerbate cancer treatment-related toxicity. Management of ongoing comorbidities should be addressed during follow-up visits. | Hypertension potentiates anthracycline-associated risk for heart failure.48 Diabetes and hypertension potentiate radiation-associated risk for stroke.49 |

| Health behaviors and lifestyle | Health behaviors can mitigate or magnify risk of cancer treatment-related toxicities. | Adherence to recommended levels of moderate to vigorous physical activity reduces risk of major cardiac events and mortality in childhood cancer survivors.50,51 Smoking increases the risk of pulmonary function deficits and subsequent malignancies.52 |

| Psychosocial | Sociodemographic factors may affect survivors’ access to health care and resources to prevent or remediate late effects. Pre-morbid and co-morbid emotional health conditions are associated with adverse outcomes. |

Survivors with (of those from households with) lower income and educational levels are more vulnerable to impaired health status and financial toxicity.9,53 Survivors experiencing psychological distress are more likely to participate in health risking behaviors (eg, tobacco, alcohol, and substance use).54,55 |

| Genetics | Cancer predisposition genes as well as common genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms) are associated with increased risk of subsequent neoplasms and other treatment-related organ dysfunction. | Survivors of retinoblastoma with RB1 mutation (all bilateral/familial cases) have an increased risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms, especially osteosarcoma.56 Several genetic variations that may modify risk for cardiomyopathy in anthracycline-exposed survivors (eg, SLC28A3, UGT1A6, RARG, CELF4, HAS3) have been identified.57 |

Table 3.

Examples of 2 Survivors: Factors Contributing to Cancer-Related Morbidity After a Childhood and Adolescent-Young Adult Cancera

| Factor | Example 1. Leukemia | Example 2. Solid Tumor |

|---|---|---|

| Patient | 3-year-old male | 16-year-old female |

| Tumor | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, B lineage, average risk, without CNS involvement | Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the chest wall, stage II |

| Treatment | Antimetabolites (PO, IV, intrathecal) Asparaginase Corticosteroids Cyclophosphamide (moderate dose) Doxorubicin (low dose) Vincristine |

Dactinomycin Vincristine Chest radiation (36 Gy) |

| Potential late effects | Peripheral neuropathy Osteopenia/osteoporosis Osteonecrosis (rare for this age) Cataracts (rare) Hepatic dysfunction (very rare) Renal insufficiency (very rare) Neurocognitive deficits Leukoencephalopathy Hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder malignancy (very rare) Secondary myelodysplasia or myeloid leukemia (very rare) Gonadal dysfunction (rare) Cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia (very rare) Dental maldevelopment, periodontal disease, excessive dental caries |

Peripheral neuropathy Subclavian artery disease Cardiac complications (cardiomyopathy, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, subclinical left ventricular dysfunction, valvular disease, atherosclerotic heart disease, myocardial infarction, pericarditis, pericardial fibrosis) Pulmonary complications (fibrosis, interstitial pneumonitis, restrictive/obstructive lung disease) Esophageal stricture Breast tissue hypoplasia Breast cancer Scoliosis/kyphosis Shortened trunk height Secondary benign or malignant neoplasms in radiation field |

| Genetics/familial | Diabetes mellitus, type 2 | Hypertension Early coronary artery disease |

| Comorbid conditions | Obesity Anxiety |

Hypertension Depression |

| Health behaviors | Sedentary lifestyle | Smoker |

| Aging | Reduced bone mineral density | Cardiomyopathy |

CNS indicates central nervous system; IV, intravenous; Gy, Gray; PO, oral.

Recognition of dose-related toxicities has resulted in modification of therapies have substantially reduced risk of some late effects.

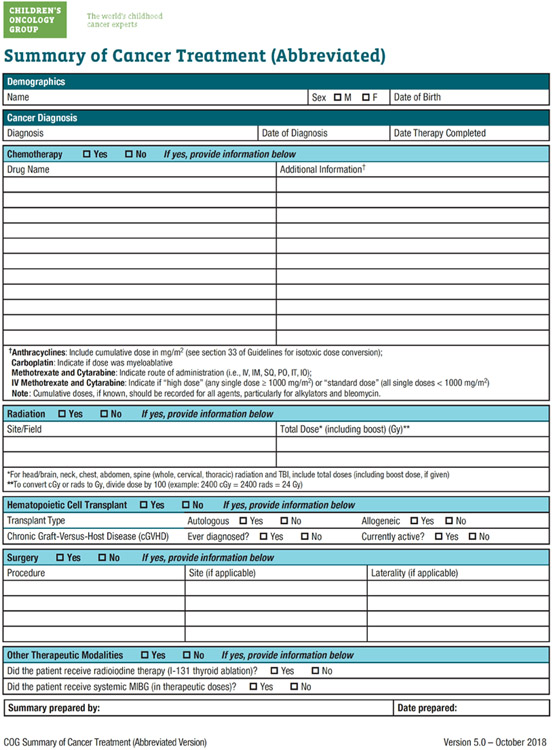

Using the COG LTFU Guidelines to Plan Survivorship Care

Risk-based care involving a systematic plan for lifelong screening, surveillance, and prevention that incorporates risks on the basis of previous cancer, cancer therapy, genetic predispositions, lifestyle behaviors, and comorbid health conditions is recommended for all survivors.13 Information critical to the coordination of risk-based care includes the date of cancer diagnosis, cancer histology, organs/tissues affected by cancer, and specific treatment modalities such as surgical procedures, chemotherapeutic agents, and radiation treatment fields and doses and history of bone marrow or stem cell transplant and blood product transfusion. Knowledge of cumulative chemotherapy dosages (eg, for anthracycline agents), or dose intensity of administration (eg, for methotrexate), also is important in estimating risk and screening frequency. This pertinent clinical information can be organized into a treatment summary that interfaces with the COG LTFU Guidelines to facilitate identification of potential late complications and recommended follow-up care (Fig 2). Because of the diversity and complexity of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer therapies, the treating oncology center represents the optimal resource for this treatment information. Furthermore, the need for ongoing, open lines of communication between the cancer center and the primary care provider is critical.

Fig 2. Sample template for cancer treatment summary containing essential data elements necessary for generating long-term follow-up guidelines.

(From the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 5.0, October 2018, used with permission).

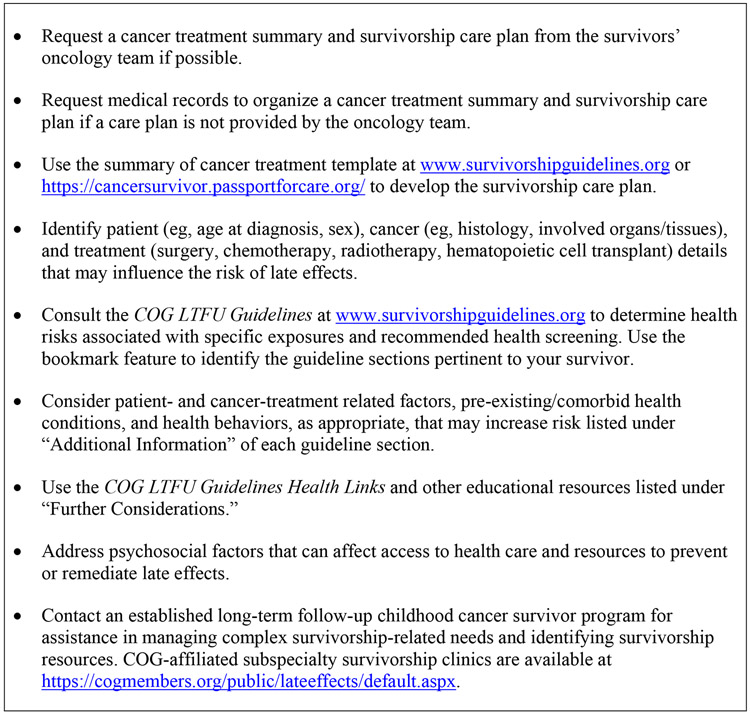

Coordination of risk-based care for childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors requires a working knowledge about cancer-related health risks and appropriate screening evaluations, or access to a resource that contains this information. Often, late effects present as a distinct clinical entity (eg, growth failure, heart failure, academic underachievement, etc) remote from cancer diagnosis and treatment. The primary care physician should consistently consider the contribution of cancer and its treatment to physical and emotional health conditions presenting in survivors, use the COG LTFU Guidelines to identify linkages of late effects and therapeutic exposures, and consult with local pediatric oncologists/late effects specialists to develop a strategy for further investigation. The COG LTFU Guidelines represent a comprehensive resource that can be utilized to plan cancer survivorship care as outlined in Fig 3. Individualized recommendations for long-term follow-up care of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors can be customized from the COG LTFU Guidelines based on each patient’s treatment history, age, and gender into a “survivorship care plan” that is ideally developed by, or in coordination with, the oncology subspecialist. The survivorship care plan is a living document that is meant to be reviewed by survivors and their health care providers at least yearly and updated as new health conditions emerge and health behaviors change over time. In addition, the COG LTFU Guidelines provide information to assist with risk stratification, allowing the health care provider to address specific treatment-related health risks that may be magnified in individual patients because of familial or genetic predisposition, sociodemographic factors, or maladaptive health behaviors. The patient education materials, known as “health links,” that accompany the COG LTFU Guidelines, are specifically tailored to enhance health supervision and promotion in this population by providing simplified explanations of guideline-specific topics in lay language.15 The COG LTFU Guidelines, associated patient education materials, and supplemental resources to enhance guideline application, including clinical summary templates, can be downloaded from www.survivorshipguidelines.org. A web-based platform that generates online therapeutic summaries with simultaneous output of patient-specific guidelines on the basis of exposure history, age, and gender is now accessible to institutions providing pediatric oncology follow-up care (https://cancersurvivor.passportforcare.org/).14

Fig 3. How to use the COG LTFU Guidelines to plan cancer survivorship care.

DISCUSSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

Pediatricians and other primary care health care professionals are uniquely qualified to deliver ongoing health care to childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors, because they are already familiar with health maintenance and supervision for healthy populations and provide care for patients with complex chronic medical conditions. The concept of the “medical home” has been endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics as an effective model for coordinating the complex health care requirements of children with special needs, such as childhood cancer survivors, to provide care and preventive services that are accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective.16 Within this framework, the pediatrician is able to view the cancer survivor in the context of the family and to assist not only the survivor but also the parents and siblings in adapting to the “new normal” of cancer survivorship. The focus of care for the childhood cancer survivor seen in a primary care practice is not the cancer from which the patient has now recovered but, rather, the actual and potential physical and psychosocial sequelae of cancer and its therapy and its impact on family functioning. Childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors are at a substantially increased risk of morbidity and mortality when compared with the general population.5-10 This updated clinical report delineates recommendations that aim to facilitate this vulnerable population’s access to high-quality survivorship.

Recommendation #1: Primary health care professionals should work collaboratively with the oncology subspecialist, to develop and implement the survivorship care plan and coordinate survivorship care.

Ideally, the survivorship care plan is developed through a shared partnership that includes the primary care and oncology subspecialty providers, the survivor, and the family. Community providers can request a cancer treatment summary and survivorship care plan from the oncology center if this is not provided at the time that the survivor transitions back to the primary care setting. If a survivorship care plan is not provided by the primary oncology team, COG-affiliated subspecialty survivorship clinics can be consulted for assistance in coordinating survivorship care (https://cogmembers.org/public/lateeffects/default.aspx). In addition to the COG LTFU Guideline recommendations for late effects screening, the ideal survivorship care plan delineates provider(s) who will be coordinating the indicated screening evaluations and identifies provider(s) responsible for communicating and explaining the results to the patient and/or caregivers.

Recommendation #2: The COG LTFU Guidelines should be used to guide the development of an individualized follow-up plan (survivorship care plan) based on the childhood, adolescent, or young adult survivor’s specific cancer treatment and risk of late complications.

Although late treatment effects can be anticipated in many cases based on therapeutic exposures, the risk to an individual patient is modified by multiple factors. The cancer patient may present with premorbid health conditions that influence tolerance to therapy and increase the risk of treatment-related toxicity. Cancer-related factors, including histology, tumor site, and tumor biology/response, often dictate treatment modality and intensity. Patient-related factors, such as age at diagnosis, and sex, may affect the risk of several treatment-related complications. Sociodemographic factors, such as household income, educational attainment, and socioeconomic status, often influence access to health insurance, remedial services, and appropriate risk-based health care. Organ senescence in aging survivors may accelerate presentation of age-related health conditions in survivors with subclinical organ injury or dysfunction resulting from cancer treatment. Genetic or familial characteristics may also enhance susceptibility to treatment-related complications. Problems experienced during and after treatment may further increase morbidity. Health behaviors, including tobacco and alcohol use, sun exposure, and dietary and exercise habits, may increase the risk of specific therapy-related complications. The COG LTFU Guidelines can assist the physician in maintaining a balance between overscreening (which could potentially cause undue fear of unlikely but remotely plausible complications as well as higher medical costs resulting from unnecessary screening) and underscreening (which could miss potentially life-threatening complications, thus resulting in lost opportunities for early intervention that could minimize morbidity).

Recommendation #3: The survivorship care plan should include screening for potential adverse medical and psychosocial effects of the cancer experience.

The follow-up evaluations of childhood adolescent and young adult cancer survivors should be individualized on the basis of their treatment history and may include screening for such potential complications as thyroid or cardiac dysfunction, second malignant neoplasms, neurocognitive difficulties, and many others.13 In addition, providers should be mindful of the psychosocial late effects experienced by youth treated for cancer, particularly those that may affect educational and vocational progress, because provider advocacy and intervention can facilitate survivor access to remedial resources and programs in 504 and individual education plans and vocational training.17 Likewise, as emotional health and family functioning may be affected by the cancer experience, proactive assessment of and referral to mental health services are important to optimize the quality of survivorship. Finally, personalized risk assessment would not be complete without consideration of socioeconomic and community factors that may affect access to survivorship resources and health care.

Recommendation #4: The survivorship care plan should address the contribution of comorbid health conditions, familial/genetic factors, and health behaviors that affect the risk of chronic disease and provide interventions and resources to remediate and prevent late effects of cancer and promote healthy lifestyle behaviors.

In addition to screening for late effects predisposed by previous therapeutic exposures, promotion of physical and mental health and well-being as part of a healthy lifestyle are important aspects of long-term follow-up care in this population. Numerous investigations have shown that survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer have a high rate of chronic health conditions when followed long-term,6,8 yet many lack awareness of their treatment-related health risks.18-20 For this reason, it is recommended that health care professionals provide anticipatory guidance regarding health promotion and disease prevention aimed at minimizing the risk of future morbidity and mortality attributable to chronic physical and mental health conditions. For example, counseling survivors who are at risk of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis about the importance of adhering to healthful dietary guidelines, limiting sedentary lifestyle with or without screen time, and having regular physical activity is important. Education about cancer- and disease-prevention benefits offered through vaccination can also reduce health risks.

Recommendation #5: Primary health care professionals should work collaboratively with the oncology subspecialist to educate survivors and their families about cancer treatment-related health risks, recommended health screening, and methods for risk reduction.

Adolescent and young adult survivors need appropriate knowledge, skills, and opportunities to learn and make decisions about their own health maintenance needs, their potential physical and mental health risks, recommended health screening related to these risks, the impact of health behaviors on physical and mental health risks, and strategies to reduce health risks. Collaboration between the oncology and primary care teams can help to ensure that survivors’ educational needs are addressed. Innovative electronic and mobile health platforms represent evolving technologies that can be leveraged to educate and empower survivors preparing for health care transitions by promoting self-management of chronic health conditions and connecting them with survivorship communities and resources.21 The COG LTFU Guidelines can be used as a resource to facilitate targeted education regarding cancer and treatment-related health risks and health promotion. The COG LTFU Guideline Health Links (available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org) can be printed for distribution in the primary care office setting and are available for viewing by patients and their caregivers on the Internet.15 In this process, it is important for health care professionals to be aware that some survivors, given their young age at diagnosis, may not remember their cancer diagnosis or the treatment that they received, or may not have been told about their cancer history.22-24

Recommendation #6: Primary health care professionals should work collaboratively with the oncology subspecialist to prepare survivors and their families for health care transitions.

Ensuring a smooth transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care services poses additional challenges in the care of childhood cancer survivors as they age out of the pediatric health care system. Because adults treated for childhood cancer represent a rare population in primary care practices, practical and educational efforts of clinicians may be focused on more prevalent primary care issues. Consequently, family physicians, internists, practitioners trained in internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds), and advanced practice providers who ultimately assume care of most adults treated for childhood cancer endorse low comfort levels and a desire for resources and guidance in managing survivors.25,26 These data underscore the importance of communication between oncology and primary care providers in health care transition planning. Pretransition planning is a critical element in the successful transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care for all adolescents and young adults with special health care needs, including cancer survivors. The medical home model provides a strong foundation for this planning.27 The updated American Academy of Pediatrics clinical report “Supporting the Health Care Transition From Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home” emphasizes the critical role of adult care clinicians in accepting and partnering with young adults to optimize health care transitions.28 In addition, the report provides practical guidance on the key elements of transition planning and implementation for medically vulnerable populations. For childhood cancer survivors, a pretransition plan ideally outlines the roles of patient, family, subspecialty, and community health care providers in the ongoing care of the survivor to ensure a successful transition. Importantly, in this process providers should respect the evolving autonomy and privacy concerns of adolescents and young adults in health care discussions and decision making, particularly related to sexual and reproductive health that may be adversely affected by the cancer experience in some survivors.29,30

Recommendation #7: Primary health care professionals should work collaboratively with the oncology subspecialist to educate survivors and their families about resources to facilitate their access to survivorship care.

Laws that extend medical coverage into young adulthood can facilitate survivors’ access to timely, high-quality, and affordable survivorship care.31 This is particularly relevant as survivors experience increased risk for multimorbidity as they age, and health conditions often present at a younger age of onset compared with individuals who have not had cancer. For example, primary care providers may not be aware of the need for early initiation of breast cancer surveillance among young adult women treated with chest radiation for childhood cancer. Delineating this risk in the survivorship care plan and providing appropriate letters of medical necessity can facilitate awareness by providers and insurance coverage of recommended surveillance imaging.32 Finally, considering research demonstrating that a substantial proportion of young adult survivors are uninsured or underinsured, transition planning should identify community resources to address medical needs, including emotional health and rehabilitation services. Payers should facilitate communication among providers in the design of their provider networks and by adequate payment for care coordination.33

SUMMARY

Given the high incidence of late effects experienced by cancer survivors, individuals treated for cancer during childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood require long-term follow-up care from knowledgeable providers so their care is appropriately tailored to their specific treatment-related risk factors. Models of survivorship care vary substantially across clinical settings based on resource availability. Because multidisciplinary late effects clinics are not consistently accessible to or utilized by cancer survivors, pediatricians and other primary care providers represent critical participants in delivery of survivorship care.34,35 The COG LTFU Guidelines provide a readily accessible resource to address knowledge deficits related to health risks associated with treatment for childhood, adolescent or young adult cancer. Availability of this resource is particularly important as the population of long-term survivors continues to increase as a result of the effectiveness of contemporary treatment approaches.

Ultimately, the goal of this clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics is to increase the awareness of general pediatricians and other primary health care professionals regarding the readily available resource of the COG LTFU Guidelines and the ability to consult with multidisciplinary long-term follow up clinics for childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors. These guidelines can, in turn, be used to develop a comprehensive yet individualized survivorship care plan for each cancer survivor who can be supported to work toward a planned transition to adult health care providers in primary and specialty care.

The survivorship care plan is a “road map” for primary health care professionals for providing risk-based, long-term follow-up care in the community setting. Ongoing communication between the cancer center and the primary care provider is the cornerstone for providing high-quality care to this vulnerable patient population.

RESEARCH GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by the National Clinical Trials (NCTN) Network Operations Center Grant (U10CA180886; PI-Adamson) and by the St. Baldrick’s Foundation. Dr. Hudson is also supported by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

ABBREVIATIONS:

- COG

Children’s Oncology Group

- COG LTFU Guidelines

Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers

Appendix

Lead Authors

Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH

Jacqueline Casillas, MD, MSHS

Melissa M. Hudson, MD, FAAP

Wendy Landier, PhD, RN, CPNP

Children’s Oncology Group

Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH

Jacqueline Casillas, MD, MSHS

Melissa M. Hudson, MD

Wendy Landier, PhD, RN, CPNP

Section on Hematology/Oncology Executive Committee, 2019-2020

Zora R. Rogers, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Carl Allen, MD, PhD, FAAP

James Harper, MD, FAAP

Jeffrey Hord, MD, FAAP

Juhi Jain, MD, FAAP

Anne Warwick, MD, MPH, FAAP

Cynthia Wetmore, MD, PhD, FAAP

Amber Yates, MD, FAAP

Past Executive Committee Members

Jeffrey Lipton, MD, PhD, FAAP

Hope Wilson, MD, FAAP

Liaison

David Dickens, MD, FAAP – Alliance for Childhood Cancer

Staff

Suzanne Kirkwood, MS

American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Board of Trustees, 2019-2020

Patrick Leavey, MD, FAAP (President)

Amy Billett, MD, FAAP

Jorge DiPaola, MD

Doug Graham, MD, PhD

Caroline Hastings, MD

Dana Matthews, MD

Betty Pace, MD

Linda Stork, MD

Maria C. Velez, MD, FAAP

Dan Wechsler, MD, PhD

Staff

Ryan Hooker, MPT

Consultant

Eneida A. Mendonca, MD, PhD, FAAP, FACMI

Footnotes

This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the organizations or government agencies that they represent.

The guidance in this report does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: None.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

Melissa M. Hudson, MD, FAAP, no conflicts

Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH, no conflicts

Jacqueline Casillas, MD, MSHS, no conflicts

Wendy Landier, PhD, RN, CPNP has a relationship with Merck, Sharp and Dohme as a Principal Investigator.

REFERENCES

- 1.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016. SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(1):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casillas J, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Greenberg ML, Yeazel MW, Ness KK, et al. Identifying Predictors of Longitudinal Decline in the Level of Medical Care Received by Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1021–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong GT, Chen Y, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Gibson TM, Mertens AC, et al. Reduction in Late Mortality among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):833–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Stratton K, Stovall M, Hudson MM, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(12):1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fidler MM, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Kelly J, Jenkinson HC, Skinner R, et al. Long term cause specific mortality among 34 489 five year survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2016;354:i4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2371–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson MM, Oeffinger KC, Jones K, Brinkman TM, Krull KR, Mulrooney DA, et al. Age-dependent changes in health status in the Childhood Cancer Survivor cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):479–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, Stratton KK, Bishop K, Krull KR, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, Forte KJ, Sweeney T, Hester AL, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children's Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children's Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4979–4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon SB, Bjornard KL, Alberts NM, Armstrong GT, Brinkman TM, Chemaitilly W, et al. Factors influencing risk-based care of the childhood cancer survivor in the 21st century. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poplack DG, Fordis M, Landier W, Bhatia S, Hudson MM, Horowitz ME. Childhood cancer survivor care: development of the Passport for Care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11(12):740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eshelman D, Landier W, Sweeney T, Hester AL, Forte K, Darling J, et al. Facilitating care for childhood cancer survivors: integrating children's oncology group long-term follow-up guidelines and health links in clinical practice. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21(5):271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J, McClinton A, Oeffinger KC, Tallia A, et al. Cancer Survivors and the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2(3):322–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bitsko MJ, Cohen D, Dillon R, Harvey J, Krull K, Klosky JL. Psychosocial Late Effects in Pediatric Cancer Survivors: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(2):337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cherven B, Mertens A, Meacham LR, Williamson R, Boring C, Wasilewski-Masker K. Knowledge and risk perception of late effects among childhood cancer survivors and parents before and after visiting a childhood cancer survivor clinic. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31(6):339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford JS, Chou JF, Sklar CA. Attendance at a survivorship clinic: impact on knowledge and psychosocial adjustment. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(4):535–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landier W, Chen Y, Namdar G, Francisco L, Wilson K, Herrera C, et al. Impact of Tailored Education on Awareness of Personal Risk for Therapy-Related Complications Among Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(33):3887–3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casillas JN, Schwartz LF, Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Kahn KL, Stuber ML, et al. The use of mobile technology and peer navigation to promote adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer survivorship care: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(4):580–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, Neglia JP, Yasui Y, Hayashi R, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287(14):1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindell RB, Koh SJ, Alvarez JM, Koyama T, Esbenshade AJ, Simmons JH, et al. Knowledge of diagnosis, treatment history, and risk of late effects among childhood cancer survivors and parents: The impact of a survivorship clinic. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(8):1444–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Syed IA, Klassen AF, Barr R, Wang R, Dix D, Nelson M, et al. Factors associated with childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their diagnosis, treatment, and risk for late effects. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(2):363–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson TO, Hlubocky FJ, Wroblewski KE, Diller L, Daugherty CK. Physician preferences and knowledge gaps regarding the care of childhood cancer survivors: a mailed survey of pediatric oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(5):878–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh E, Daugherty CK, Wroblewski K, Lee H, Kigin ML, Rasinski KA, et al. General internists' preferences and knowledge about the care of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(1):11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Physicians, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group, Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White PH, Cooley WC, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring G, American Academy Of P, American Academy Of Family P, American College Of P. Supporting the Health Care Transition From Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klipstein S, Fallat ME, Savelli S, AAP Committee on Bioethics ASoHO, AAP Section on Surgery. Fertility Preservation for Pediatric and Adolescent Patients With Cancer: Medical and Ethical Considerations. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcell AV, Burstein GR, Committee On A. Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services in the Pediatric Setting. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park ER, Kirchhoff AC, Perez GK, Leisenring W, Weissman JS, Donelan K, et al. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study participants' perceptions and understanding of the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oeffinger KC, Ford JS, Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Henderson TO, Hudson MM, et al. Promoting Breast Cancer Surveillance: The EMPOWER Study, a Randomized Clinical Trial in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(24):2131–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Committee On Child Health Financing. Guiding Principles for Managed Care Arrangements for the Health Care of Newborns, Infants, Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1452–e1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eshelman-Kent D, Kinahan KE, Hobbie W, Landier W, Teal S, Friedman D, et al. Cancer survivorship practices, services, and delivery: a report from the Children's Oncology Group (COG) nursing discipline, adolescent/young adult, and late effects committees. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(4):345–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nathan PC, Agha M, Pole JD, Hodgson D, Guttmann A, Sutradhar R, et al. Predictors of attendance at specialized survivor clinics in a population-based cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merchant TE, Conklin HM, Wu S, Lustig RH, Xiong X. Late effects of conformal radiation therapy for pediatric patients with low-grade glioma: prospective evaluation of cognitive, endocrine, and hearing deficits. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3691–3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Santen HM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van de Wetering MD, Wallace WH. Hypogonadism in Children with a Previous History of Cancer: Endocrine Management and Follow-Up. Horm Res Paediatr. 2019;91(2):93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudson MM. Reproductive outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1171–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong GT, Sklar CA, Hudson MM, Robison LL. Long-term health status among survivors of childhood cancer: does sex matter? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4477–4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King AA, Seidel K, Di C, Leisenring WM, Perkins SM, Krull KR, et al. Long-term neurologic health and psychosocial function of adult survivors of childhood medulloblastoma/PNET: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(5):689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gawade PL, Hudson MM, Kaste SC, Neglia JP, Wasilewski-Masker K, Constine LS, et al. A systematic review of selected musculoskeletal late effects in survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2014;10(4):249–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandez-Pineda I, Hudson MM, Pappo AS, Bishop MW, Klosky JL, Brinkman TM, et al. Long-term functional outcomes and quality of life in adult survivors of childhood extremity sarcomas: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibson TM, Li Z, Green DM, Armstrong GT, Mulrooney DA, Srivastava D, et al. Blood Pressure Status in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(12):1705–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulrooney DA, Armstrong GT, Huang S, Ness KK, Ehrhardt MJ, Joshi VM, et al. Cardiac Outcomes in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer Exposed to Cardiotoxic Therapy: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(2):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clemens E, de Vries AC, Pluijm SF, Am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen A, Tissing WJ, Loonen JJ, et al. Determinants of ototoxicity in 451 platinum-treated Dutch survivors of childhood cancer: A DCOG late-effects study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;69:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chemaitilly W, Armstrong GT, Gajjar A, Hudson MM. Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis Dysfunction in Survivors of Childhood CNS Tumors: Importance of Systematic Follow-Up and Early Endocrine Consultation. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4315–4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leisenring W, Friedman DL, Flowers ME, Schwartz JL, Deeg HJ. Nonmelanoma skin and mucosal cancers after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, Kawashima T, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3673–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mueller S, Fullerton HJ, Stratton K, Leisenring W, Weathers RE, Stovall M, et al. Radiation, atherosclerotic risk factors, and stroke risk in survivors of pediatric cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(4):649–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones LW, Liu Q, Armstrong GT, Ness KK, Yasui Y, Devine K, et al. Exercise and risk of major cardiovascular events in adult survivors of childhood hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3643–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott JM, Li N, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Leisenring W, Nathan PC, et al. Association of Exercise With Mortality in Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(10):1352–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oancea SC, Gurney JG, Ness KK, Ojha RP, Tyc VL, Klosky JL, et al. Cigarette smoking and pulmonary function in adult survivors of childhood cancer exposed to pulmonary-toxic therapy: results from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(9):1938–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, Klosky JL, Krull KR, Srivastava D, et al. Determinants and Consequences of Financial Hardship Among Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(2):189–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, Foster RH, Mertens AC, Robison LL, et al. Risky health behavior among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(6):634–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lown EA, Hijiya N, Zhang N, Srivastava DK, Leisenring WM, Nathan PC, et al. Patterns and predictors of clustered risky health behaviors among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2016;122(17):2747–2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong JR, Morton LM, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, Seddon JM, Sampson JN, et al. Risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms in long-term hereditary retinoblastoma survivors after chemotherapy and radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(29):3284–3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Armenian S, Bhatia S. Predicting and preventing anthracycline-related cardiotoxicity. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]