Abstract

Background:

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) is a rare but serious event following definitive radiation for prostate cancer. Radiation-associated MIBC (RA-MIBC) can be difficult to manage given the challenges of delivering definitive therapy to a previously irradiated pelvis. The genomic landscape of RA-MIBC and whether it is distinct from non–RA-MIBC are unknown.

Objective:

To define mutational features of RA-MIBC and compare the genomic landscape of RA-MIBC with that of non–RA-MIBC.

Design, setting, and participants:

We identified patients from our institution who received radiotherapy for prostate cancer and subsequently developed MIBC.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

We performed whole exome sequencing of bladder tumors from RA-MIBC patients. Tumor genetic alterations including mutations, copy number alterations, and mutational signatures were identified and were compared with genetic features of non–RA-MIBC. We used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate recurrence-free (RFS) and overall (OS) survival.

Results and limitations:

We identified 19 RA-MIBC patients with available tumor tissue (n = 22 tumors) and clinical data. The median age was 76 yr, and the median time from prostate cancer radiation to RA-MIBC was 12 yr. The median RFS was 14.5 mo and the median OS was 22.0 mo. Compared with a cohort of non–RA-MIBC analyzed in parallel, there was no difference in tumor mutational burden, but RA-MIBCs had a significantly increased number of short insertions and deletions (indels) consistent with previous radiation exposure. We identified mutation signatures characteristic of APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis, aging, and homologous recombination deficiency. The frequency of mutations in many known bladder cancer genes, including TP53, KDM6A, and RB1, as well as copy number alterations such as CDKN2A loss in RA-MIBC was similar to that in non–RA-MIBC.

Conclusions:

We identified unique mutational properties that likely contribute to the distinct biological and clinical features of RA-MIBC.

Patient summary:

Bladder cancer is a rare but serious diagnosis following radiation for prostate cancer. We characterized genetic features of bladder tumors arising after prostate radiotherapy, and identify similarities with and differences from bladder tumors from patients without previous radiation.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Bladder cancer, Radiation, Radiation-associated cancer, Second malignancy, DNA sequencing, Genomics, Mutational signatures

Radiation-associated muscle-invasive bladder cancers arising after prostate cancer radiotherapy have mutational evidence of radiation exposure but share many driver alterations with non–radiation-associated muscle-invasive bladder cancers.

1. Introduction

Radiation-associated malignancies are a rare but potentially lethal late toxicity following definitive radiotherapy [1]. Accurate estimation of the frequency of radiation-associated secondary malignancies is challenging, and true rates likely depend upon patient and treatment characteristics, including patient age, anatomic site, and radiation dose and technique. Although limited by their retrospective nature, several studies have reported an increased risk of bladder cancer in men treated with definitive prostate cancer radiotherapy [2–6]. For example, in a study of >84 000 men treated with radical prostatectomy (RP) or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for localized prostate cancer, the 10-yr cumulative risk of a bladder cancer diagnosis was 1.63% with RP versus 2.34% with EBRT [7]. In addition, radiation-associated bladder cancer patients may be more likely to present with locally advanced disease than bladder cancer patients without previous pelvic radiation [8,9].

For patients diagnosed with radiation-associated muscle-invasive bladder cancer (RA-MIBC), limited retrospective data suggest that clinical outcomes are inferior to those for patients with non–RA-MIBC [8,9], but the underlying reasons are poorly understood. One possible explanation for inferior outcomes among RA-MIBC patients is that radical locoregional treatment such as radical cystectomy can be more difficult to deliver in the setting of prior prostate radiation [10]. Consistent with this, a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) analysis showed that RA-MIBC patients were less frequently treated with radical surgery than age- and stage-matched patients with non–RA–MIBC [9].

Another possible explanation for poor outcomes among RA-MIBC patients is that RA-MIBC may represent a molecularly distinct entity from non–RA-MIBC. While large-scale genomic studies such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have systematically defined the genomic landscape of non–RA-MIBC [11], little is known about the genomic features of RA-MIBC. In an effort to improve the understanding of RA-MIBC, we performed whole exome sequencing (WES) of 22 bladder tumors from 19 muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) patients who had previously received radiotherapy for prostate cancer. We identify several distinct mutational features of RA-MIBC, including an increased frequency of short insertions and deletions (indels), but also find that the frequency of many common bladder tumor driver alterations in RA-MIBC was similar to that in non–RA-MIBC.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients and samples

We queried the Dana-Farber/Brigham & Women’s Cancer Center database to identify patients treated with definitive prostate radiotherapy or postprostatectomy adjuvant/salvage radiotherapy, who were subsequently diagnosed with MIBC and who had banked formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) MIBC tumor tissue at our institution. Transurethral resection or radical cystectomy specimens were used in all cases. For the two patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the radical cystectomy specimen was used. For each case, the bladder tumor specimen was reviewed by a board-certified genitourinary pathologist (M.H.) to identify the region of highest tumor density, and two 1.5-mm punch cores were harvested from this region. All work was approved by the institutional review board.

2.2. Clinical characteristics and survival analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the 19 RA-MIBC patients were collected and reviewed. For survival analysis, overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from surgery (either transurethral resection of the bladder tumor [TURBT] or cystectomy) until death from any cause. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from surgery until death from any cause or disease recurrence observed in radiographic imaging. For the OS analysis, patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. For the RFS analysis, patients without death or disease recurrence were censored at the time of last radiographic follow-up. Clinical data for the TCGA cohort was downloaded from cBioPortal (www.cbioportal.org/datasets). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to assess point estimates of survival and was computed using the “survival” and “survminer” packages in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

2.3. DNA extraction and WES

Genomic DNA was purified from FFPE punch cores from each tumor specimen at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Genomics Platform (Cambridge, MA, USA) using a commercial kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany; catalog no. 56404). Normal (germline) DNA samples were not available. Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) was quantified using a PicoGreen assay (Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples with at least 100 ng of dsDNA were used to generate libraries for WES. WES was also performed at the Genomics Platform of the Broad Institute. The sequencing protocol has been described previously [12]. Briefly, whole exome capture libraries were constructed from tumor DNA after sample shearing, end repair, phosphorylation, and ligation to barcoded sequencing adaptors. An Illumina bait set with all coding regions of Gencode hg19, all coding regions of RefSeq gene, and KnownGene tracks from the UCSC genome browser was used [13]. The samples were multiplexed and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq technology (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

2.4. Data processing and analysis

A WES characterization pipeline (https://github.com/broadinstitute/CGA_Production_Analysis_Pipeline) developed at the Broad Institute was used to call, filter, and annotate somatic mutations and copy number variations. Cross-individual contamination was estimated using ContEst [14], and only samples with <4% estimated contamination were included in the study. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels in targeted exons were identified using MuTect [15] and Strelka [16] algorithms, respectively. Alterations were annotated using Oncotator [17]. Possible sequencing artifacts due to orientation bias, DNA oxidation, FFPE storage, and mapping were filtered using a pipeline developed at the Broad Institute [18]. Alterations in prespecified frequently mutated MIBC genes (TP53, KMT2D, KDM6A, ARID1A, PIK3CA, KMT2C, RB1, EP300, FGFR3, STAG2, ATM, FAT1, ELF3, CREBBP, ERBB2, SPTAN1, KMT2A, ERBB3, ERCC2, CDKN1A, ASXL2, TSC1, and FBXW7) and 34 DNA repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS1, PMS2, ERCC2, ERCC3, ERCC4, ERCC5, BRCA1, BRCA2, MRE11A, NBN, RAD50, RAD51, RAD51B, RAD51D, RAD52, RAD54L, BRIP1, FANCA, FANCC, PALB2, RAD51C, BLM, ATM, ATR, CHEK1, CHEK2, MDC1, POLE, MUTYH, PARP1, and RECQL4) were identified in the RA-MIBC cohort, and alteration frequencies were compared with those of the non–RA-MIBC cohort, as described below. Gene mutations across the cohort were summarized in comutation plots [19].

For the non–RA-MIBC cohort, we processed whole exomes (n = 50) from MIBC previously published by our group [20]. Radiation-associated and non–radiation-associated cohorts were sequenced using different libraries (ICE and Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA respectively); therefore, to perform adequate comparisons between the two cohorts, we created an intersection of target and bait intervals, and verified panel of normals (PoNs) for both ICE and Agilent. BAM files from both cohorts were processed with the CGA tumor-only pipeline, and samples with tumor/germline DNA pairs from “non–RA-MIBC” were also processed with original CGA pipeline to account for mutation calls due to the absence of matched germline DNA. In addition, we also implemented a common variant filtering strategy to remove likely germline artifacts leveraging the ExAC database, now a part of gnomAD, which was also used by AACR GENIE. Specifically, common variants are annotated and soft filtered if the variant appears in at least ten alleles across any ancestral subpopulation in ExAC. SNVs (missense, splice site, nonsense, and translation start site), indels (frame shift deletions, frame shift insertions, inframe deletion, inframe insertion, stop codon deletion, start codon deletion, start codon insertion, and stop codon insertion), and tumor mutational burden (TMB; missense, splice site, nonsense, translation start site, and nonstop mutations) were determined in both non–RA-MIBC and RA-MIBC. Differences in SNVs, indels, and TMB between the two cohorts were calculated using Fisher’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test. Findings were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05.

2.5. Total and allelic copy numbers

Copy number events were inferred using GATK4 CNV and interrogated using GISTIC 2, to identify copy number segments that were significantly amplified or deleted in our cohort [21]. Each alteration was assigned a G-score that considers its amplitude and frequency across the cohort. False discovery rate q values were calculated for aberrant regions and considered significant below a 0.99 threshold. For each significant region, an aberrant “peak” corresponding to genomic location was then identified. Baseline was called for amplitude threshold peaks between −0.3 and 0.3. Deletions and amplifications called for peak values <−0.3 and >0.3, respectively. Copy number PoNs previously created were used to match tumor samples [22].

2.6. Mutation signature analysis

To identify mutational processes present in radiation-associated tumors, we used the SigMA algorithm (https://github.com/parklab/SigMA), a likelihood-based approach that can detect mutational signatures (COSMIC Signatures, version 2) from SNVs of whole exome data and small mutation counts [23]. Differences in SNVs between groups were calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Wilcoxon rank sum test, with a Bonferroni correction used to compare significant differences in SNVs across the mutational signatures. We also performed a signature analysis using Signal Analyze2 (https://signal.mutationalsignatures.com) to identify mutational signatures in each sample [24].

2.7. Data availability and code

Figures were created in R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and the code is available on GitHub (https://github.com/CarvalhoFilipeL/Mouw_RABC). Genomic data are being deposited in the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (https://www.cbioportal.org/).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical characteristics of RA-MIBC

We queried our institutional database to identify patients who had received definitive or adjuvant/salvage radiation for localized prostate cancer and subsequently developed MIBC (ie, RA-MIBC). We identified a total of 19 patients with muscle-invasive bladder tumor tissue available for genomic analysis (see Patients and methods section). Clinical characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. The median age of patients at the time of RA-MIBC diagnosis was 76 yr, and the median time from prostate cancer radiation to RA-MIBC diagnosis was 12 yr. Twelve patients (63.2%) underwent radical cystectomy for RA-MIBC, whereas one patient (5.2%) underwent partial cystectomy and six patients (31.6%) had TURBT. Two patients (10.5%) received neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to radical cystectomy and another two patients (10.5%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. Five patients (26.3%) had a component of squamous, mucinous, or sarcomatoid histology; the remaining 14 patients (73.7%) had pure urothelial histology.

Table 1 –

RA-MIBC patient characteristics

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 19 | |

| Age at RA-MIBC diagnosis (yr), median (IQR) | 76 (73–82) | |

| Time from prostate RT to MIBC diagnosis (yr), median (range) | 12 (9–18) | |

| Age at prostate RT (yr), median (IQR) | 67 (62–70) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current/former | 13 | 68 |

| Never smoker | 4 | 21 |

| Unknown | 2 | 11 |

| NMIBC (prior to RA-MIBC) | 6 | 32 |

| Intravesical therapy for NMIBC | 4 | 21 |

| RA-MIBC T stage | ||

| T2 | 12 | 63 |

| T3 | 2 | 11 |

| T4 | 5 | 26 |

| RA-MIBC nodal status | ||

| Node negative | 10 | 53 |

| Node positive | 3 | 16 |

| Nx | 6 | 31 |

| RA-MIBC histology | ||

| Urothelial only | 14 | 74 |

| Urothelial with a squamous component | 2 | 11 |

| Urothelial with a sarcomatoid component | 2 | 11 |

| Urothelial with a mucinous component | 1 | 5 |

| Surgery for RA-MIBC | ||

| TURBT | 6 | 32 |

| Partial cystectomy | 1 | 5 |

| Radical cystectomy | 12 | 63 |

| Chemotherapy for RA-MIBC | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 2 | 11 |

| Adjuvant | 2 | 11 |

| None | 15 | 79 |

| Prostate cancer radiation type | ||

| Brachytherapy | 3 | 16 |

| Definitive EBRT | 7 | 37 |

| Definitive EBRT + ADT | 2 | 11 |

| EBRT plus brachytherapy | 1 | 5 |

| Salvage EBRT | 6 | 32 |

ADT = androgen deprivation therapy; EBRT = external beam radiation therapy; IQR = interquartile range; NMIBC = non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer; RA-MIBC = radiation-associated muscle-invasive bladder cancer; RT = radiation therapy; TURBT = transurethral resection of bladder tumor.

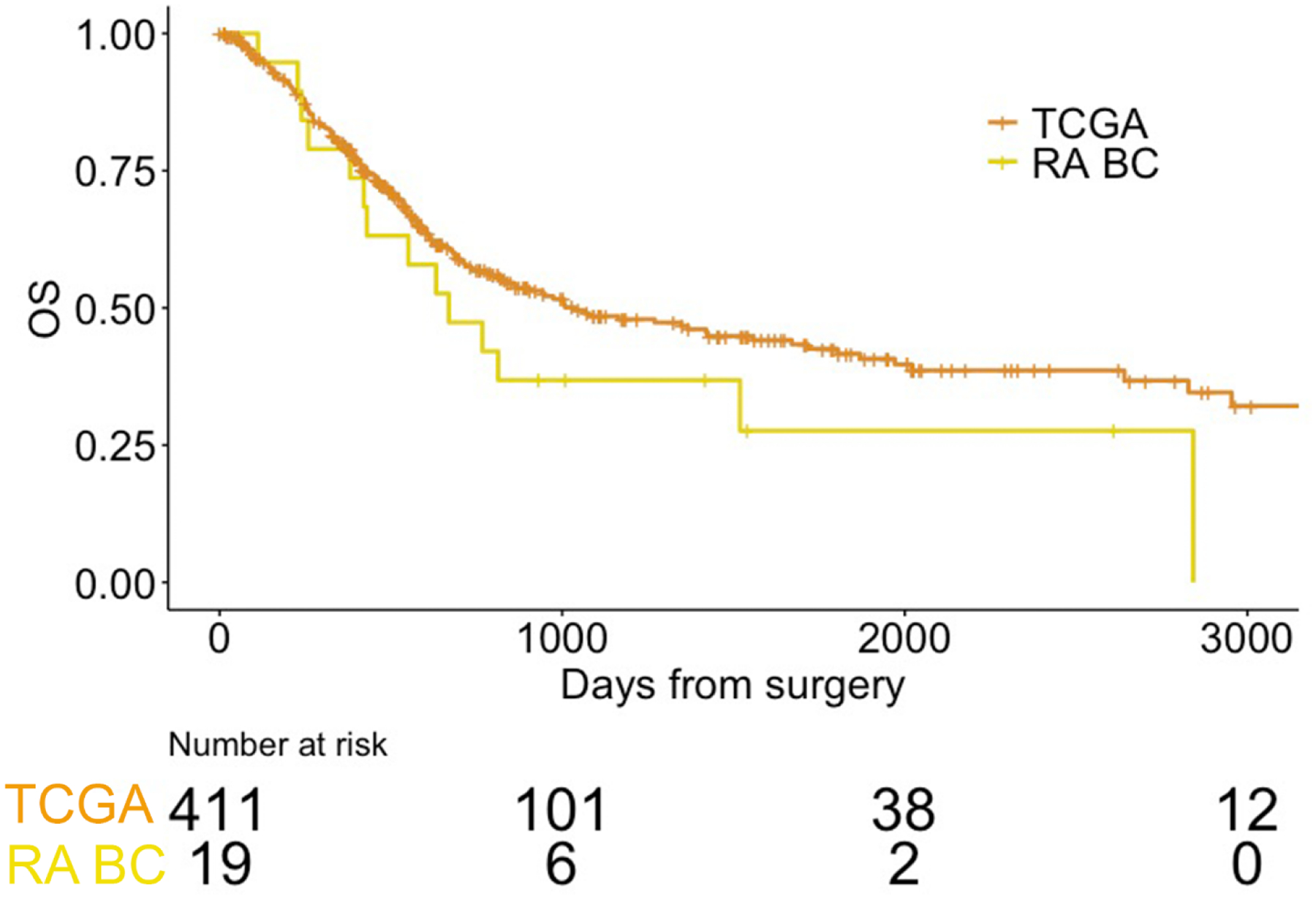

The median RFS and OS for the cohort were, respectively, 14.5 and 22.0 mo following RA-MIBC diagnosis (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The median OS did not differ significantly for patients receiving cystectomy versus TURBT (22.0 vs 20.8 mo, p = 0.34) or for patients who received chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy (11.4 vs 20.2 mo, p = 0.73). Compared with patients with pure urothelial histology, patients with any variant histology (eg, squamous, mucinous, or sarcomatoid features) had worse median RFS (3.3 vs 18.1 mo, p = 0.03) and median OS (12.5 vs 26.7 mo, p = 0.02). There was no statistically significant difference in OS between the RA-MIBC cohort and the patients with non–RA-MIBC from the TCGA cohort (p = 0.14; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 –

Overall survival of patients in the RA-MIBC cohort compared with that in MIBC patients from the TCGA cohort. Survival times were calculated from the date of surgery (cystectomy or TURBT).

MIBC = muscle-invasive bladder cancer; OS = overall survival; RA BC = radiation-associated MIBC cohort; RA-MIBC = radiation-associated MIBC; TCGA = The Cancer Genome Atlas; TURBT = transurethral resection of the bladder tumor.

3.2. Genomic landscape of RA-MIBC

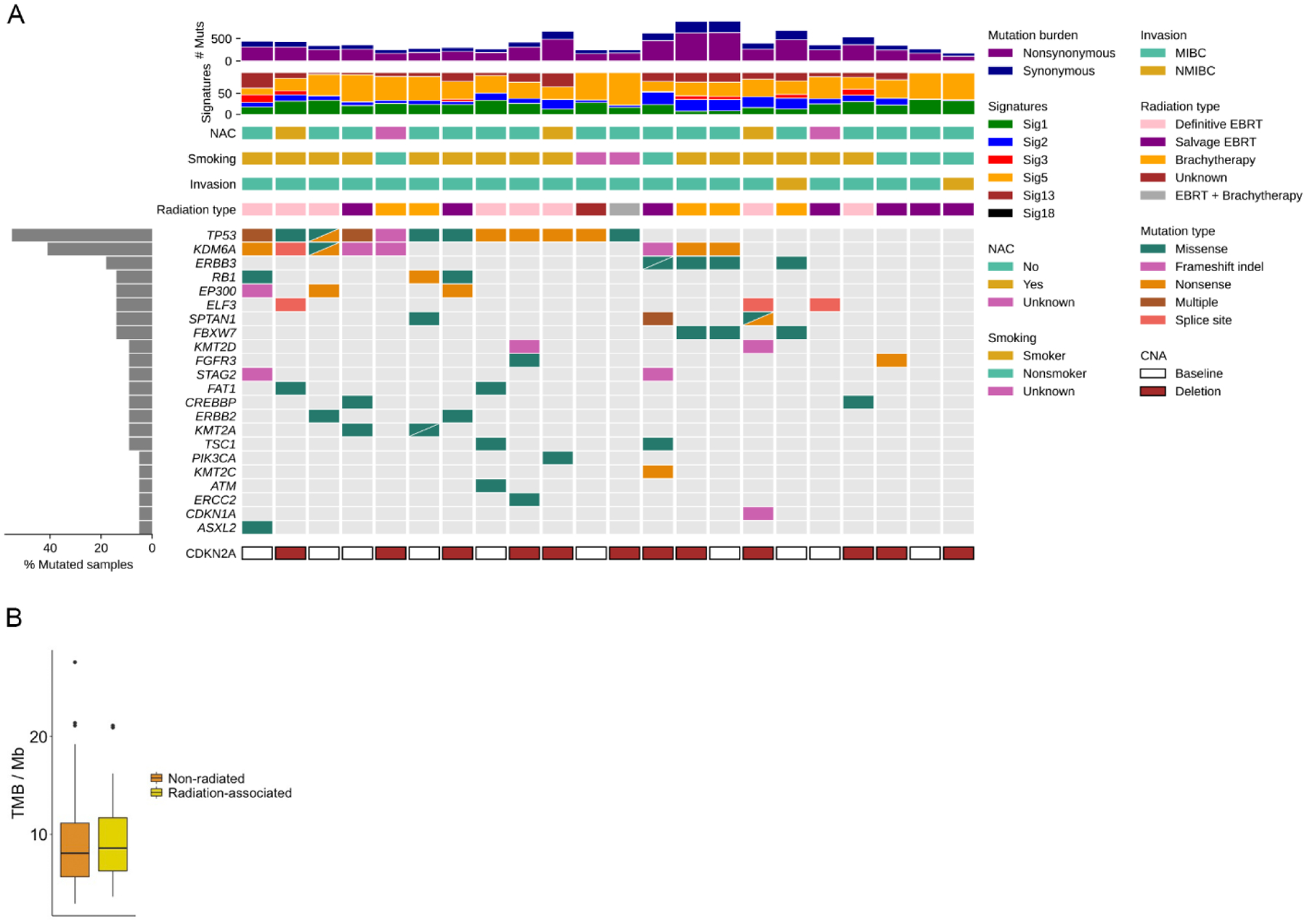

We performed WES of the radiation-associated bladder tumor for all 19 patients in the cohort (see Patients and methods section; Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 2). Each patient had at least one RA-MIBC sample that underwent WES. In addition, one patient had a non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) tumor sample that also underwent WES, and one patient had three sequenced samples (one NMIBC and two MIBC). The mean target coverage was 177× for somatic tumor DNA (Supplementary Table 1). A total of 13 624 variants were identified, including 6425 missense, 461 nonsense, 410 frameshift, and 5556 silent mutations. In parallel, we used a similar workflow to perform a tumor-only analysis of a cohort of 50 non–RA-MIBC patients previously reported by our group (“nonradiated” cohort) [20]. The mean nonsynonymous somatic tumor burden (TMB) in the RA-MIBC cohort was 10.0 mutations/Mb (range, 4–21), which was similar to the TMB in the nonradiated cohort (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2 –

Mutational landscape of the RA-MIBC cohort. (A) Tumor mutational burden (TMB), mutational signatures, select clinical characteristics, and alterations in select bladder cancer genes for each tumor in the cohort (n = 22). (B) TMB was not significantly different but similar between the RA-MIBC and non–radiation-associated MIBC cohorts.

CNA = copy-number alteration; EBRT = external beam radiation therapy; MIBC = muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NMIBC = non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

We first evaluated genes known to be recurrently mutated in bladder cancer [11]. We identified alterations in many known bladder cancer genes including TP53 (in 12/19 patients and 12/22 tumors) and KDM6A (eight out of 19 patients and nine out of 22 tumors; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Most of the alterations in TP53 and KDM6A were predicted loss-of-function mutations, consistent with the known tumor suppressor roles for these genes. The mutation frequency of TP53 and KDM6A, as well as several other known bladder cancer genes including RB1, ERBB2, PIK3CA, and ERCC2, was not significantly different between the RA-MIBC tumors and the 50 non–RA-MIBC tumors (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Matched RA-MIBC and RA-NMIBC samples were available for two patients (Supplementary Fig. 4). In one case, we observed mutations in FBXW7 and ERBB3 in MIBC and NMIBC samples; however, the RA-MIBC samples also had a nonsense (truncating) mutation in KDM6A. In the other case, both the NMIBC and the MIBC tumors had a low TMB and no shared alterations in genes commonly mutated in bladder cancer. These examples highlight the complex molecular relationships that can exist between noninvasive and invasive tumors from the same patient.

In addition to identifying mutations in known bladder cancer genes, we also investigated the somatic copy number landscape of RA-MIBC (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 5). Twelve of 19 RA-MIBCs had focal loss of chromosome 9p21, which harbors the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A. Chromosome 9p21 deletion is also the most common copy number alteration in non–RA-MIBC, occurring in 30% of TCGA cases [11]. We identified several additional focally amplified regions that are also amplified in non–RA-MIBC and harbor known bladder cancer genes such as chromosome 8q22 (YWHAZ), chromosome 4p16 (FGFR3), chromosome 19q12 (CCNE1), and others (Supplementary Fig. 5). Overall, the most common and characteristic copy number alterations of non–radiation-associated bladder cancer also appear to be present in RA-MIBC.

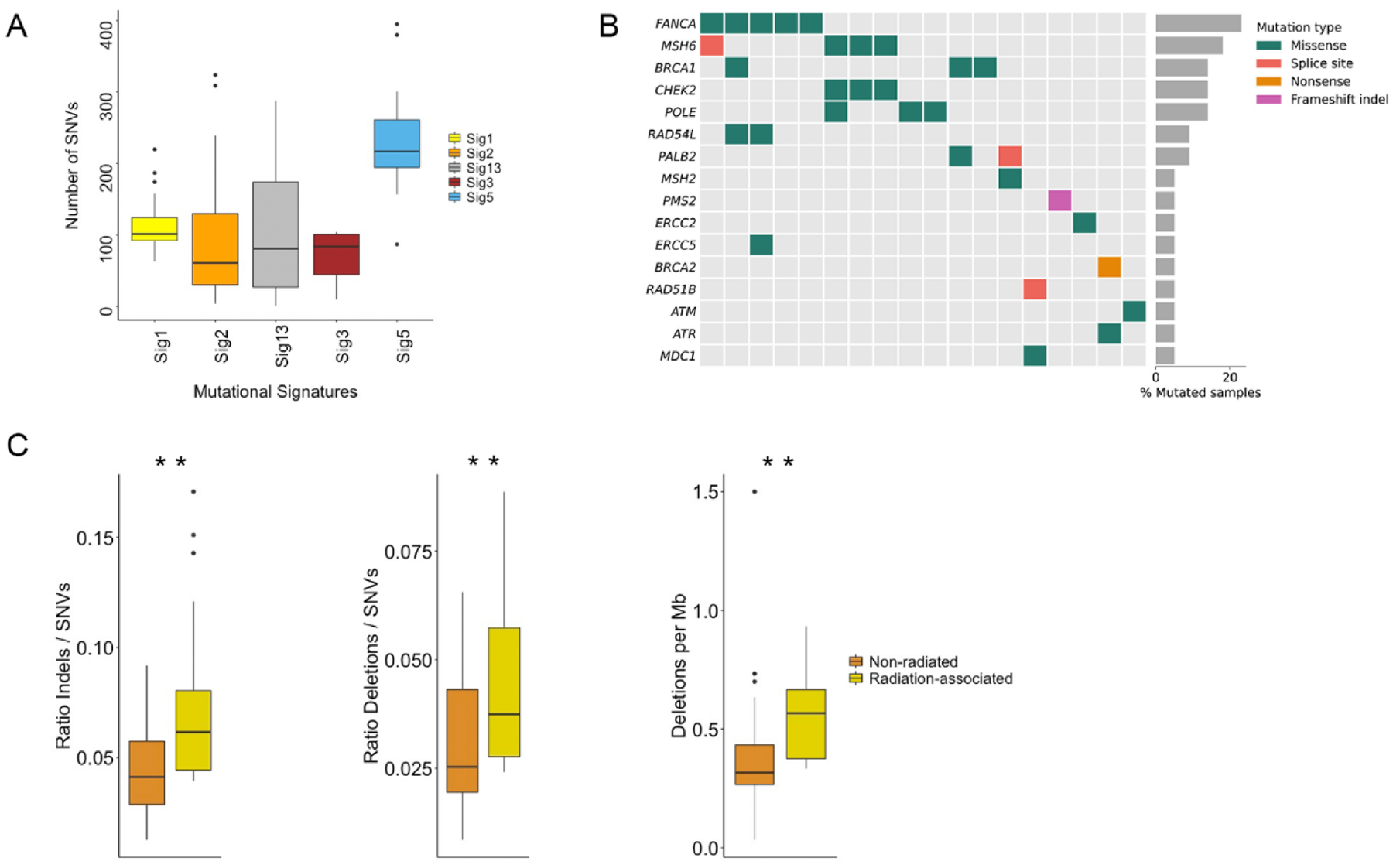

3.3. Mutational signatures and DNA repair gene alterations in RA-MIBC

To gain further insights regarding the underlying mutational processes in RA-MIBC, we performed mutational signature analysis (see Patients and methods section). We identified five mutational signatures in the RA-MIBC cohort (Fig. 3A) [25]. Signatures 1 and 5 are present across tumor types and increase with patient age (“clock-like” signatures) [11]. Signature 1 is thought to arise via spontaneous deamination of 5-methylcytosine, whereas signature 5 has also been associated with ERCC2 mutations and tobacco exposure in bladder cancer [26]. Signatures 2 and 13 are attributed to APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis [27,28]. APOBEC-related mutations are implicated in NMIBC disease progression and are also present in non–RA-MIBC [11,29,30]. Signature 3 has been associated with deficiencies in the homologous recombination (HR) DNA repair pathway [31]. Although HR deficiency (HRD) mutational signatures are present in a limited number of bladder tumors [32], the prognostic and therapeutic implications of HRD in MIBC have not been well characterized. One of the five cases with ≥5% of mutations attributed to signature 3 harbored a BRCA2 nonsense mutation, and another case had a BRCA1 missense mutation, but no discernable HR gene defects were present in the other three cases (Supplementary Fig. 6). We also observed an increased frequency of alterations in several other DNA repair genes, such as FANCA, MSH6, and CHEK2, in the RA-MIBC cohort compared with the nonradiated cohort; however, these differences were not statistically significant, and other DNA repair genes had a lower alteration frequency in the RA-MIBC cohort than in the nonradiated cohort (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, many of the observed alterations in DNA repair genes in the RA-MIBC cohort were missense mutations and therefore of uncertain functional significance. A separate de novo signature analysis using the signal pipeline [24] also identified signatures 1, 2, 5, and 13 (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 3 –

Mutational features of RA-MIBC. (A) Five mutational signatures were identified in the RA-MIBC cohort. Signatures 1 and 5 (age related) were present in all 22 tumors, signatures 2 and 13 (APOBEC-mediated mutagenesis) were identified in 21 tumors, and signature 3 (homologous recombination deficiency) was identified in eight tumors. Signature 18 (unknown etiology) was identified in two tumors (not shown). There were significant differences in the number of single nucleotide variants (SNVs) across mutational signatures (Kruskal-Wallis, p < 0.001), and signature 5 had a significantly higher number of SNVs than all other signatures (Wilcoxon rank sum, adjusted p < 0.001). (B) Mutations in select DNA repair genes in the RA-MIBC cohort (only tumors with at least one alteration in a listed DNA repair gene are included [n = 18]). (C) The RA-MIBC cohort had a significantly higher ratio of short insertions/deletions (indels) to SNVs than the nonradiated MIBC cohort (left). The ratio of deletions to SNVs as well as the number of deletions per megabase (Mb) were also significantly higher in the RA-MIBC cohort than in the non–radiation-associated MIBC cohort (middle and right panels). MIBC = muscle-invasive bladder cancer; RA BC = radiation-associated MIBC cohort; RA-MIBC = radiation-associated MIBC.

In other radiation-associated solid tumor cohorts, including radiation-associated breast tumors, sarcomas, and gliomas, an increased frequency of short indels has been reported and is driven by an increase in the frequency of short deletions [33–35]. The ratio of indels to SNVs was significantly higher in the RA-MIBC cohort than in the nonradiated MIBC cohort (mean 0.075 vs 0.044, Wilcoxon test p < 0.001; Fig. 3C), as was the ratio of deletions to SNVs (0.045 vs 0.031, Wilcoxon rank sum p = 0.003) and the number of deletions per megabase (0.56 vs 0.37, Wilcoxon rank sum p < 0.001). These results indicate a role for radiation exposure in shaping the mutational landscape of RA-MIBC and suggest that a high indel-to-SNV ratio may be a common feature of radiation-associated tumors across histological subtypes.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used WES to examine the mutational characteristics of MIBCs arising after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive mutational analysis performed to date for this unique and clinically challenging patient population. We found that RA-MIBCs harbor mutational features that are distinct from non–RA-MIBCs, including an increased frequency of short indels. However, the frequency of mutations in many known bladder cancer genes as well as the frequency of common focal copy number alterations was not significantly different between RA-MIBCs and non–RA-MIBCs.

The mechanisms underlying radiation-associated tumor formation are poorly understood, and comprehensive genomic studies are challenging given the relative rarity and significant clinical heterogeneity of radiation-associated tumors [1]. However, a recent large study analyzed thousands of genomes from radiation-treated gliomas and metastatic tumors, and identified a pattern of genome-wide deletions consistent with classical nonhomologous end-joining (cNHEJ)-mediated repair of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks [35]. A similar pattern of increased deletions was observed in this RA-MIBC cohort as well as in other radiation-treated tumor cohorts and preclinical models [33,34,36], suggesting a common mutagenic signature of radiation exposure across tumor types. Upregulation of cNHEJ activity may be a mechanism of cell survival following radiation, and genomic instability caused by the error-prone cNHEJ pathway may contribute to RT-associated tumor formation. However, a direct mechanistic link between indel signatures arising from error-prone repair processes and tumorigenesis in previously irradiated tissues remains to be established.

Interestingly, we did not observe significant differences in the mutation frequency of known bladder cancer genes between RA-MIBCs and non–RA-MIBCs [11]. Specifically, genes such as TP53 and KDM6A that are among the most commonly mutated genes in non–RA-MIBCs were also the most commonly mutated genes in RA-MIBC. Similarly, copy number alterations such as CDKN2A deletions and TERT amplifications that frequently occur in non–RA-MIBCs were also present in RA-MIBCs. Although the comparison of non–RA-MIBCs versus RA-MIBCs is limited by the small size of the RA-MIBC cohort and the lack of matched germline DNA, these findings suggest that the genetic drivers of RA-MIBC largely overlap with those of non–RA-MIBC and that targeted therapies that are approved or being investigated in non–RA-MIBC may also be active in RA-MIBC.

Several studies suggest that clinical outcomes of RA-MIBC patients are inferior to those of patients with non–RA-MIBC, and although the RA-MIBC cohort was small, the median RFS and OS were shorter than reported in many published MIBC cohorts [11,37,38]. Our analyses identify genomic differences between RA-MIBC and non–RA-MIBC that may contribute to the differences in outcomes. However, in addition to radiation exposure, specific genetic features of the radiation-associated cohort analyzed here, such as all patients being male and all also having had prostate cancer, may also contribute to the observed genomic and clinical differences. Finally, challenges associated with salvage local therapy for patients who have previously received high-dose radiation may contribute to inferior clinical outcomes observed in this population [9].

5. Conclusions

Future efforts should focus on reducing the risk of radiation-associated cancers through genomics-informed patient selection and improved radiation techniques. These prevention strategies should be coupled with additional clinical and biological investigations aimed at identifying and targeting therapeutic vulnerabilities of RA-MIBCs.

Supplementary Material

Financial disclosures:

Kent W. Mouw certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Matthew Mossanen reports receiving writing/editor fees from the Editorial Board of Elsevier Practice Update Bladder Cancer Center of Excellence. Guru Sonpavde reports being in the advisory boards of BMS, Genentech, EMD Serono, Merck, Sanofi, Seattle Genetics/Astellas, AstraZeneca, Exelixis, Janssen, Bicycle Therapeutics, Pfizer, Immunomedics/Gilead, Scholar Rock, and G1 Therapeutics; receiving research support to institution from Sanofi, AstraZeneca, Immunomedics/Gilead, QED, Predicine, and BMS; being a member of the steering committee of studies of BMS, Bavarian Nordic, Seattle Genetics, QED, and G1 Therapeutics (all unpaid), and of AstraZeneca, EMD Serono, and Debiopharm (paid); being in the data safety monitoring committee of Mereo; receiving travel costs from BMS (2019) and AstraZeneca (2018); receiving writing/editor fees from Uptodate, Editor of Elsevier Practice Update Bladder Cancer Center of Excellence; and receiving speaker fees from Physicians Education Resource (PER), Onclive, Research to Practice, and Medscape (all educational). Adam S. Kibel reports advisory/consulting activities for AstraZeneca, Bayer, General Electric, Merck, Insight Diagnostics, Janssen, and Profound. Eliezer Van Allen reports advisory/consulting activities for Tango Therapeutics, Genome Medical, Invitae, Enara Bio, Janssen, Manifold Bio, and Monte Rosa; receiving research support from Novartis and BMS; equity in Tango Therapeutics, Genome Medical, Syapse, Enara Bio, Manifold Bio, Microsoft, and Monte Rosa; receiving travel reimbursement from Roche/Genentech; and filing of institutional patents on chromatin mutations and immunotherapy response, and methods for clinical interpretation. Kent Mouw reports being in the advisory boards of Pfizer and EMD Serono; receiving research support to institution from Pfizer; receiving writing/editor fees from Uptodate; receiving speaker fees from Onclive; and filing institutional patent on mutational signatures of DNA repair deficiency. None of these are directly related to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Kamran SC, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Ng A, Haas-Kogan D, Viswanathan AN. Therapeutic radiation and the potential risk of second malignancies. Cancer 2016;122:1809–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Moon K, Stukenborg GJ, Keim J, Theodorescu D. Cancer incidence after localized therapy for prostate cancer. Cancer 2006;107:991–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nieder AM, Porter MP, Soloway MS. Radiation therapy for prostate cancer increases subsequent risk of bladder and rectal cancer: a population based cohort study. J Urol 2008;180:2005–9; discussion 2009–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keehn A, Ludmir E, Taylor J, Rabbani F. Incidence of bladder cancer after radiation for prostate cancer as a function of time and radiation modality. World J Urol 2017;35:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liauw SL, Sylvester JE, Morris CG, Blasko JC, Grimm PD. Second malignancies after prostate brachytherapy: incidence of bladder and colorectal cancers in patients with 15 years of potential follow-up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;66:669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Neugut AI, Ahsan H, Robinson E, Ennis RD. Bladder carcinoma and other second malignancies after radiotherapy for prostate carcinoma. Cancer 1997;79:1600–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moschini M, Zaffuto E, Karakiewicz PI, et al. External beam radiotherapy increases the risk of bladder cancer when compared with radical prostatectomy in patients affected by prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Eur Urol 2019;75:319–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bostrom PJ, Soloway MS, Manoharan M, Ayyathurai R, Samavedi S. Bladder cancer after radiotherapy for prostate cancer: detailed analysis of pathological features and outcome after radical cystectomy. J Urol 2008;179:91–5; discussion 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sha ST, Dee EC, Mossanen M, et al. Clinical characterization of radiation-associated muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urology 2021;154:208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nguyen DP, Al Hussein Al Awamlh B, Faltas BM, et al. Radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in patients with and without a history of pelvic irradiation: survival outcomes and diversion-related complications. Urology 2015;86:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Robertson AG, Kim J, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cell 2017;171:540–556 e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Stojanov P, et al. Whole-exome sequencing and clinical interpretation of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples to guide precision cancer medicine. Nat Med 2014;20:682–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fisher S, Barry A, Abreu J, et al. A scalable, fully automated process for construction of sequence-ready human exome targeted capture libraries. Genome Biol 2011;12:R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cibulskis K, McKenna A, Fennell T, Banks E, DePristo M, Getz G. ContEst: estimating cross-contamination of human samples in next–generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2011;27:2601–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cibulskis K, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:213–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Saunders CT, Wong WS, Swamy S, Becq J, Murray LJ, Cheetham RK. Strelka: accurate somatic small–variant calling from sequenced tumor-normal sample pairs. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1811–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ramos AH, Lichtenstein L, Gupta M, et al. Oncotator: cancer variant annotation tool. Hum Mutat 2015;36:E2423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Costello M, Pugh TJ, Fennell TJ, et al. Discovery and characterization of artifactual mutations in deep coverage targeted capture sequencing data due to oxidative DNA damage during sample preparation. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Crowdis J, He MX, Reardon B, Van Allen EM. CoMut: visualizing integrated molecular information with comutation plots. Bioinformatics 2020;36:4348–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2014;4:1140–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mermel CH, Schumacher SE, Hill B, Meyerson ML, Beroukhim R, Getz G. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol 2011;12:R41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Liu D, Schilling B, Liu D, et al. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med 2019;25:1916–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gulhan DC, Lee JJ, Melloni GEM, Cortés-Ciriano I, Park PJ. Detecting the mutational signature of homologous recombination deficiency in clinical samples. Nat Genet 2019;51:912–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Degasperi A, Amarante TD, Czarnecki J, et al. A practical framework and online tool for mutational signature analyses show inter-tissue variation and driver dependencies. Nat Cancer 2020;1:249–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature 2020;578:94–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim J, Mouw KW, Polak P, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations are associated with a distinct genomic signature in urothelial tumors. Nat Genet 2016;48:600–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Petljak M, Alexandrov LB, Brammeld JS, et al. Characterizing mutational signatures in human cancer cell lines reveals episodic APOBEC mutagenesis. Cell 2019;176:1282–1294 e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell 2012;149:979–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nassar AH, Umeton R, Kim J, et al. Mutational analysis of 472 urothelial carcinoma across grades and anatomic sites. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2458–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hedegaard J, Lamy P, Nordentoft I, et al. Comprehensive transcriptional analysis of early-stage urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2016;30:27–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013;500:415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Borcsok J, Diossy M, Sztupinszki Z, et al. Detection of molecular signatures of homologous recombination deficiency in bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:3734–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Behjati S, Gundem G, Wedge DC, et al. Mutational signatures of ionizing radiation in second malignancies. Nat Commun 2016;7:12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lee CL, Mowery YM, Daniel AR, et al. Mutational landscape in genetically engineered, carcinogen-induced, and radiation-induced mouse sarcoma. JCI Insight 2019;4:e128698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kocakavuk E, Anderson KJ, Varn FS, et al. Radiotherapy is associated with a deletion signature that contributes to poor outcomes in patients with cancer. Nat Genet 2021;53:1088–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kucab JE, Zou X, Morganella S, et al. A compendium of mutational signatures of environmental agents. Cell 2019;177:821–836 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Giacalone NJ, Shipley WU, Clayman RH, et al. Long-term outcomes after bladder-preserving tri-modality therapy for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer: an updated analysis of the Massachusetts General Hospital experience. Eur Urol 2017;71:952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Iyer G, Tully CM, Zabor EC, et al. Neoadjuvant gemcitabine-cisplatin plus radical cystectomy-pelvic lymph node dissection for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a 12-year experience. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2020;18:387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Figures were created in R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and the code is available on GitHub (https://github.com/CarvalhoFilipeL/Mouw_RABC). Genomic data are being deposited in the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (https://www.cbioportal.org/).