Abstract

Primary cilia are ubiquitous mechanosensory organelles that specifically coordinate a series of cellular signal transduction pathways to control cellular physiological processes during development and in tissue homeostasis. Defects in the function or structure of primary cilia have been shown to be associated with a large range of diseases called ciliopathies. Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E (INPP5E) is an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase that is localized on the ciliary membrane by anchorage via its C-terminal prenyl moiety and hydrolyzes both phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, leading to changes in the phosphoinositide metabolism, thereby resulting in a specific phosphoinositide distribution and ensuring proper localization and trafficking of proteins in primary cilia. In addition, INPP5E also works synergistically with cilia membrane-related proteins by playing key roles in the development and maintenance homeostasis of cilia. The mutation of INPP5E will cause deficiency of primary cilia signaling transduction, ciliary instability and ciliopathies. Here, we present an overview of the role of INPP5E and its coordination of signaling networks in primary cilia.

Keywords: INPP5E, cilia, membrane-associated proteins, ciliopathies, signaling networks

Introduction

The cilium is an antenna-like organelle that is ubiquitous in various cell types. They can be divided into two classes: motile cilia and non-motile cilia (also called primary cilia). Motile cilia have an axoneme that contains a central pair of microtubules surrounded by nine pairs of microtubules in a configuration called 9 + 2 and mainly distribute in the respiratory tract epithelium, ventricular ependymal epithelium, sperm and fallopian tube epithelium (Gudis and Cohen, 2010). However, primary cilia does not contain the central pair of microtubules and mainly distribute in the cone tube, vestibular sensory hair cells and olfactory epithelium (Takeda and Narita, 2012; Toriello and Parisi, 2009). The microtubule-based axoneme protruding from the basal body is enclosed by a bilayer lipid membrane (ciliary membrane) that is rich in membrane-associated proteins (Singla and Reiter, 2006). These proteins are pivotal in ciliary function and structure. Firstly, as a cell signal receiver and transmitter, cilia play essential roles in the reception and transmission of signals from extracellular stimuli. Signals are received through membrane proteins on the ciliary membrane and transmitted to downstream pathways, resulting in cascade reactions, such as Hedgehog (HH) and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) pathway (Singla and Reiter, 2006). Moreover, cilia are unable to synthesize their own proteins and require intraciliary transport systems to transport these proteins. This process was conducted in a transition zone (TZ) which is maintained by the cilia membrane proteins. Within the TZ, the entry, localization of the transmembrane receptors and other proteins mediated formation and maintenance homeostasis of cilia are also elaborately regulated by membrane transport protein (Williams et al., 2011; Chih et al., 2012).

The localisation and activity of membrane associated proteins were dictated by phosphoinositides (PI). Due to distinct PI compositions, the protein composition of the ciliary membrane is different from that of the surrounding, contiguous plasma membrane. In additional, the distribution and abundance of PI were tightly modulated by the activity of PI kinases and PI phosphatases. Among these regulatory enzymes, INPP5E play critical roles in regulating the distribution and quantity of PI on cilia membrane. INPP5E is an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase with a specific affinity for lipid substrates (Dyson et al., 2012). As a lipid signaling molecule, INPP5E regulates many cellular processes, including vesicle trafficking, cytoskeletal dynamics, protein synthesis, proliferation, and survival (Ooms et al., 2009). Here, we detailed summarize the roles of INPP5E in ciliary homeostasis and signal transduction.

Cilia Associated Cellular Signalling

Cilia are ancient organelles with hair-like structures that extend from the cell body into the fluid surrounding the cell (Eley et al., 2005). Traditionally, motile cilia were thought to be a motor organ that generation of movement (Ran et al., 2021). In contrast, primary cilia serve an essential sensory purpose in transducing stimuli from extracellular environment to the cell interior to modulate the basic cellular processes (Singla and Reiter, 2006; Song and Zhou, 2020). These indicated that the main function of primary cilia is detection and transduction of cellular signalling. Among these pathways, Hedgehog (HH) and G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) pathway play critical roles in fulfiling the function of primary cilia (Ko, 2016; Loskutov et al., 2018).

The Hh pathway is a leading paradigm for ciliary signaling, and has diversity of functions in tissue homeostasis and proliferation (Briscoe and Thérond, 2013). It is initiated by Hh lipoprotein ligand binds to its transmembrane receptor protein patched (Ptch). Then, Ptch is inactivated and relieves smoothening (SMO), resulting in the activation of downstream targets through Gli transcription factors, which are processed from repressors to activators that organize the Hh transcriptional program (Bangs and Anderson, 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). GPCR signaling play critical roles in the sensory function of primary cilia (Schou et al., 2015). GPCRs are largest receptor superfamily in cilia which involve in numerous physiological functions. Once activated by heterotrimeric G proteins, the specific sites of GPCRs are phosphorylated by GRKs and recruit and bind with β-arrestins which sequencely activate downstream signal pathway, such as c-SRC and ERK1/2 (Eichel and von Zastrow, 2018).

Ciliary Membrane-Associated Proteins and Ciliopathies

The composition of membrane-associated proteins confer the cilia with specific functions and structure. Due to lack of the ability to synthesis own proteins, the intracellular ciliogenesis pathway requires transportation, fusion and reorganization of ciliary proteins. And, membrane-associated proteins can modulate the structure and molecular composition of the cilia. Many studies have demonstrated that membrane-associated proteins, small Rabs, play critical roles in modulating ciliary structure. Currently, at least nine of the 66 Rabs have been reported to be involved in cilium formation and control of ciliary membrane protein levels (Hor and Goh, 2019). Rab8, which plays critical roles in polarized exocytosis in polarized epithelial cells and neurons, has been reported to promote extension of the ciliary membrane. Disruption of Rab8 function in zebrafish inhibited ciliogenesis. Another study demonstrated that Rab8 must coordinate with Rab11 to execute this function. Knockdown of Rab11 expression inhibited primary ciliogenesis (Knodler et al., 2010). ARL13B, highly enriched in cilia, stabilizes ciliary membrane integrity and anterograde IFT. Knock out this gene disrupts cilia architecture (Gigante et al., 2020). The mutation of ARL13B may cause Joubert Syndrome, a human disease now classified under the cluster of ciliopathies (Dilan et al., 2019). Furthermore, ciliary development and homeostasis are highly related to dynamic changes of ciliary membrane associated proteins. The BBS proteins were also involve in these process. They comprise a family of at least 11 proteins that localize to cilia and/or ciliary basal bodies (Blacque and Leroux, 2006; He and Axelrod, 2006). Evidence from studies in model organisms such as C. elegans, Chlamydomonas, Xenopus laevis and mice indicates that BBS proteins assist in the organization of intracellular trafficking and in coordinating motors responsible for anterograde IFT (Snow et al., 2004), as well as in recruiting PCP proteins to the ciliary basal body and cilium (Ross et al., 2005; Park et al., 2006). Mutution in these proteins are characterized by a series of disorders associated with ciliary dysfunction, such as obesity, pigmentary retinopathy, polydactyly, mental and growth retardation and renal failure (Mykytyn and Sheffield, 2004).

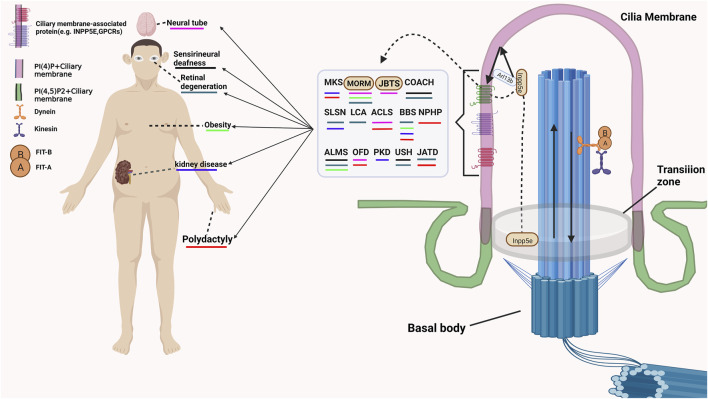

Except for modulating the structure and molecular composition of the cilia, many membrane-associated proteins also involve in receiving and transmitting extracellular signals. The G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which are specifically located in the membrane compartment of the primary cilia, are involved in receiving various extracellular signals (Schou et al., 2015; Watabe et al., 2020). Multiple mutations of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) cause functional disorders of cilia and lead to ciliary diseases. Some membrane-associated protein family not only participate in maintaining the structure and homeostasis of cilia, but also involve in regulating the cilia associated signalling. Rab23, one of small Rabs, inhibits Shh signaling by regulating Smoothened levels. However, the mechanism by which Rab23 modulates the expression of smoothened remains unknown elusive. The mutation of Rab23 in humans was characterized by carpenter’s syndrome (Hor and Goh, 2019). A recent study demonstrated that ARL13B is also a regulator of the Hh signaling pathway (Gigante et al., 2020). However, the regulatory mechanism of Hh signaling mediated by ARL13B was different from that of other ciliary genes that promote the Hh response and the production of Gli repressors and activators. Loss function of ARL13B may lead to an impaired response to Hh signaling and the production of activators but has no effect on the expression of the repressor Gli3 (Gigante et al., 2020). The mutation of ARL13B may cause Joubert Syndrome, a human disease now classified under the cluster of ciliopathies (Dilan et al., 2019). Arl6, also named as BBS3, is necessary for localization of the BBSome complex on cilia. Inhibition the expression of Arl6 cause reduction of ciliogenesis and Hh activity (Liu et al., 2016). Abnormalities in these functions of these proteins will cause various ciliary diseases (Pal et al., 2016; Long and Huang, 2019). The detaied ciliopathies and related symptom are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The example of cilia associated disease and related Symptom. MKS, Meckel-Gruber syndrome; MORM, Mental retardation, truncal obesity, retinal dystrophy, and micropenis; JBTS, Joubert syndrome; COACH, Cerebellar vermis hypo/aplasia, oligophrenia, congenital ataxia, ocular coloboma, and hepatic fibrosis; SLSN, Senior-Løken syndrome Arima syndrome; LCA, Leber congenital amaurosis; ACLS, Acrocallosal syndrome; BBS, Bardet-Biedl syndrome; NPHP, Nephronophthisis, truncal obesity, retinal dystrophy, and micropenis; ALMS, Alström Syndrome; OFD, Orofaciodigital syndromes; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; USH, Usher syndrome; JATD, Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy.

INPP5E Modulates Signaling Networks in Primary Cilia

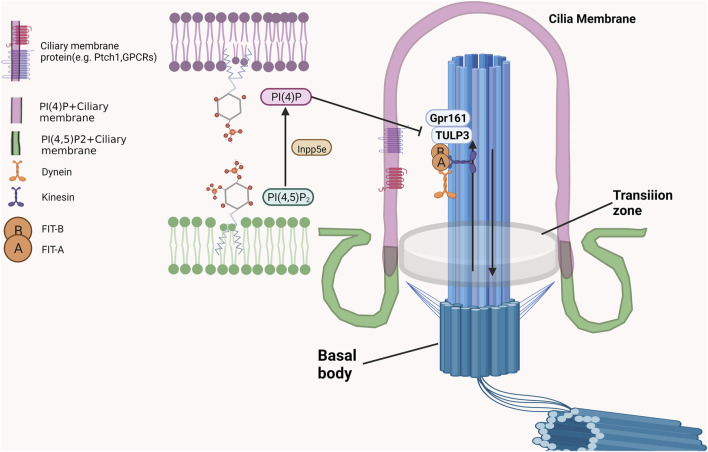

As an inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase, INPP5E is mainly located in cilia in quiescent cells to maintain it is function and stability (Conduit et al., 2021; Kosling et al., 2018). A portion of INPP5E is also located in the lysosome, and its membrane anchoring and enzymatic activity are necessary for autophagy (Hasegawa et al., 2016; Sierra Potchanant et al., 2017). INPP5E located in the ciliary membrane could dephosphorylate phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4, 5)P2) to generate phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PtdIns(4)P) to maintain a PtdIns(4)P-high, PtdIns(4,5)P2-low environment, which was necessary for transmission of hedgehog signalling and blockage the entry of TULP3 and Gpr161 into cilia just as showed in Figure 2 (Chavez et al., 2015; Garcia-Gonzalo et al., 2015). After INPP5E inactivation, PI(4, 5)P2 accumulates at the apex of the ciliary body, while PtdIns (4)P is depleted. This process was accompanied by the recruitment of the PI (4, 5) P2-interacting proteins TULP3 and Gpr161 into cilia, and results in increased production of cAMP and repression of the Shh transcriptional gene Gli1, which affects the transmission of Shh signaling. (Han et al., 2019). Moreover, the ciliary needed a higher shh response to activate Smo when the function of INPP5E was lost. INPP5E regulates the shh response by adjusting the production of GliA/GliR in a time-dependent manner (Constable et al., 2020). By regulating SHH signaling, INPP5E could promote medulloblastoma progression through the PtdIns (3,4,5) P3/AKT/GSK3β signaling axis (Conduit et al., 2017). Other biological functions of cilia could also be regulated by the production or substrate of INPP5E. Recent studies have demonstrated that PIs in olfactory cilia participate in recognizing chemical odorants. The interplay (including relative abundance and localization) between phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) and phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2), which are tightly regulated by INPP5E, play critical roles in these biological processes (Bielas et al., 2009). Furthermore, INPP5E regulate ciliary protein transport by controlling the interaction of the phosphoinositide component of the ciliary membrane with several centrosome proteins.

FIGURE 2.

The critical roles of INPP5E in maintaining the PIs on cilia membrane.

INPP5E Functions Synergistically With Other Cilia Membrane-Associated Proteins

Although playing critical roles in biological processes of cilia, INPP5E may need to interact with membrane associated proteins to perform its function. On one hand, the ciliary membrane localization of INPP5E is determined by the membrane associated proteins. INPP5E, which lacks the sequence to which AR.L13B binds, was not detectable within cilia (Qiu et al., 2021). PDE6δ which is essential for the classification and entry of cilia of INPP5E also affect the retaining of INPP5E on the ciliary membrane (Fansa et al., 2016; Kosling et al., 2018). INPP5E targets primary cilia through a PDE6δ-dependent mechanisms. The mutation of PDE6δ, which loses the ability to bind with INPP5E, fails to target primary cilia (Thomas et al., 2014).

On the other hand, INPP5E could modulate the functions of membrane associated proteins in a direct or indirect manner. For example, the ability of Aurora kinase A (AURKA) in promoting the stability of cilia increases when binds with INPP5E. The transcription of AURK is also partly regulated by INPP5E which affect the activity of AKT (Plotnikova et al., 2015). INPP5E also plays critical roles in rod photoreceptor cells. Mutations in the RPGR gene are highly related to retinitis pigmentosa. Further investigation demonstrated that these mutations lost the ability to bind with INPP5E (Han et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Moreover, Tulp3, which localizes to primary cilia, is a negative regulatory factor in the Hh signaling pathway. The activation of Tulp3 was modulated by the substrate of INPP5E: PtdIns(4,5)P2, PtdIns(3,4)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, which bind with the phosphoinositide binding domain of Tulp3 to promote MCHR1 trafficking to primary cilia (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2010). The product of INPP5E also participate in the initiation of ciliogenesis through modulate the function of ciliary membrane associated proteins. PtdIns(4)P, which is tightly regulated by INPP5E and PIPKIγ, could bind to TTBK2 and CEP164 which inhibits the localization of TTBK2 in M-centriole and the TTBK2-CEP164 interaction (Xu et al., 2016).

Conclusion and Perspectives

Traditionally, motile cilia were thought to function by acting as mechanical sweepers. For example, motile cilia in brain ventricles promote the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid (Ringers et al., 2020); the debris and mucociliary of lungs and upper respiratory tract were cleared by cilia on epithelial surface of the respiratory tract (Legendre et al., 2021); and oviduct cilia transfer the fertilized egg to the uterus (Yuan et al., 2021). On the contrary, the primary cilium is a biosensor that transmits extracellular stimuli signals through ciliary membrane proteins to intracellularly. Recent investigations on the biology of cilia unveil many new functions and roles of both primary and motile cilia. Such as the role of motile cilia in organ homeostasis. And, primary cilia have been confirmed to be pivotal in tumorigenesis and chemosensation (Cao et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2019). These physiological processes are tightly modulated by ciliary membrane-associated proteins. To fulfill these special functions, the ciliary membrane need to have a diffferent composition of proteins that from that of the contiguous plasma membrane (Simons and Toomre, 2000). The quantity and localization of ciliary membrane-associated proteins are precisely regulated by the synergistic activity of PI kinases and PI phosphatases. Among these PI enzymes, INPP5E plays critical roles in ciliogenesis. An increasing number of findings demonstrate that INPP5E executes its function by interacting with membrane-associated proteins on cilia. However, the detailed mechanisms by which INPP5E and membrane-associated proteins cooperatively regulate the functions and structure of the cilium still remain elusive. It is necessary to elucidate these molecular mechanisms in the future investigations. Furthermore, more studies should focus on screening more membrane-associated proteins involved in regulating the function and structure of the cilium. A comprehensive understanding of how INPP5E and other membrane-associated proteins affect protein transport inside and outside the cilia and membrane protein structure as well as how they change the trend aggregation of second messengers may provide new insight for the diagnosis and treatment of ciliary diseases.

Author Contributions

RZ and JT wrote the manuscript. RZ drew the graphics by using with “BioRender.com” which is permits by “BioRender’s Academic License Terms”. TL, JZ, and WP edited and finalized the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (32170727) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR202103010337).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Bangs F., Anderson K. V. (2017). Primary Cilia and Mammalian Hedgehog Signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 9, a028175. 10.1101/cshperspect.a028175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielas S. L., Silhavy J. L., Brancati F., Kisseleva M. V., Al-Gazali L., Sztriha L., et al. (2009). Mutations in INPP5E, Encoding Inositol Polyphosphate-5-Phosphatase E, Link Phosphatidyl Inositol Signaling to the Ciliopathies. Nat. Genet. 41, 1032–1036. 10.1038/ng.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacque O. E., Leroux M. R. (2006). Bardet-Biedl Syndrome: an Emerging Pathomechanism of Intracellular Transport. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63, 2145–2161. 10.1007/s00018-006-6180-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J., Thérond P. P. (2013). The Mechanisms of Hedgehog Signalling and its Roles in Development and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol 14, 416–429. 10.1038/nrm3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H.-T., Liu M.-M., Shao Q.-N., Jiao Z.-Y. (2021). The Role of the Primary Cilium in Cancer. neo 68, 899–906. 10.4149/neo_2021_210210n204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez M., Ena S., Van Sande J., de Kerchove d’Exaerde A., Schurmans S., Schiffmann S. N. (2015). Modulation of Ciliary Phosphoinositide Content Regulates Trafficking and Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Output. Dev. Cel. 34, 338–350. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chih B., Liu P., Chinn Y., Chalouni C., Komuves L. G., Hass P. E., et al. (2012). A Ciliopathy Complex at the Transition Zone Protects the Cilia as a Privileged Membrane Domain. Nat. Cel Biol 14, 61–72. 10.1038/ncb2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduit S. E., Davies E. M., Fulcher A. J., Oorschot V., Mitchell C. A. (2021). Superresolution Microscopy Reveals Distinct Phosphoinositide Subdomains within the Cilia Transition Zone. Front. Cel Dev. Biol. 9, 634649. 10.3389/fcell.2021.634649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduit S. E., Ramaswamy V., Remke M., Watkins D. N., Wainwright B. J., Taylor M. D., et al. (2017). A Compartmentalized Phosphoinositide Signaling axis at Cilia Is Regulated by INPP5E to Maintain Cilia and Promote Sonic Hedgehog Medulloblastoma. Oncogene 36, 5969–5984. 10.1038/onc.2017.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable S., Long A. B., Floyd K. A., Schurmans S., Caspary T. (2020). The ciliary phosphatidylinositol phosphatase Inpp5e plays positive and negative regulatory roles in Shh signaling. Development 147, dev183301. 10.1242/dev.183301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilan T. L., Moye A. R., Salido E. M., Saravanan T., Kolandaivelu S., Goldberg A. F. X., et al. (2019). ARL13B, a Joubert Syndrome-Associated Protein, Is Critical for Retinogenesis and Elaboration of Mouse Photoreceptor Outer Segments. J. Neurosci. 39, 1347–1364. 10.1523/jneurosci.1761-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson J. M., Fedele C. G., Davies E. M., Becanovic J., Mitchell C. A. (2012). Phosphoinositide Phosphatases: Just as Important as the Kinases. Sub-cellular Biochem. 58, 215–279. 10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichel K., von Zastrow M. (2018). Subcellular Organization of GPCR Signaling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 39, 200–208. 10.1016/j.tips.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley L., Yates L. M., Goodship J. A. (2005). Cilia and Disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 308–314. 10.1016/j.gde.2005.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fansa E. K., Kösling S. K., Zent E., Wittinghofer A., Ismail S. (2016). PDE6δ-mediated Sorting of INPP5E into the Cilium Is Determined by Cargo-Carrier Affinity. Nat. Commun. 7, 11366. 10.1038/ncomms11366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalo F. R., Phua S. C., Roberson E. C., Garcia G., 3rd, Abedin M., Schurmans S., et al. (2015). Phosphoinositides Regulate Ciliary Protein Trafficking to Modulate Hedgehog Signaling. Dev. Cel. 34, 400–409. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigante E. D., Taylor M. R., Ivanova A. A., Kahn R. A., Caspary T. (2020). ARL13B Regulates Sonic Hedgehog Signaling from outside Primary Cilia. eLife 9, 50434. 10.7554/eLife.50434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudis D. A., Cohen N. A. (2010). Cilia Dysfunction. Otolaryngologic Clin. North America 43, 461–472. 10.1016/j.otc.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Miyoshi K., Shikada S., Amano G., Wang Y., Yoshimura T., et al. (2019). TULP3 Is Required for Localization of Membrane-Associated Proteins ARL13B and INPP5E to Primary Cilia. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 509, 227–234. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa J., Iwamoto R., Otomo T., Nezu A., Hamasaki M., Yoshimori T. (2016). Autophagosome-lysosome Fusion in Neurons Requires INPP 5E, a Protein Associated with Joubert Syndrome. Embo J. 35, 1853–1867. 10.15252/embj.201593148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Axelrod J. D. (2006). A WNTer Wonderland in Snowbird. Development (Cambridge, England) 133, 2597–2603. 10.1242/dev.02452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hor C. H., Goh E. L. (2019). Small GTPases in Hedgehog Signalling: Emerging Insights into the Disease Mechanisms of Rab23-Mediated and Arl13b-Mediated Ciliopathies. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 56, 61–68. 10.1016/j.gde.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knödler A., Feng S., Zhang J., Zhang X., Das A., Peränen J., et al. (2010). Coordination of Rab8 and Rab11 in Primary Ciliogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 6346–6351. 10.1073/pnas.1002401107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J. Y. (2016). Functional Study of the Primary Cilia in ADPKD. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 933, 45–57. 10.1007/978-981-10-2041-4_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kösling S. K., Fansa E. K., Maffini S., Wittinghofer A. (2018). Mechanism and Dynamics of INPP5E Transport into and inside the Ciliary Compartment. Biol. Chem. 399, 277–292. 10.1515/hsz-2017-0226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre M., Zaragosi L.-E., Mitchison H. M. (2021). Motile Cilia and Airway Disease. Semin. Cel Dev. Biol. 110, 19–33. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Shen Q., Yu T., Huang H., Zhang Z., Ding J., et al. (2016). Small GTPase Arl6 Controls RH30 Rhabdomyosarcoma Cell Growth through Ciliogenesis and Hedgehog Signaling. Cell Biosci 6, 61. 10.1186/s13578-016-0126-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H., Huang K. (2019). Transport of Ciliary Membrane Proteins. Front Cel Dev Biol 7, 381. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loskutov Y. V., Griffin C. L., Marinak K. M., Bobko A., Margaryan N. V., Geldenhuys W. J., et al. (2018). LPA Signaling Is Regulated through the Primary Cilium: a Novel Target in Glioblastoma. Oncogene 37, 1457–1471. 10.1038/s41388-017-0049-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S., Wen X., Chih B., Nelson C. D., Lane W. S., Scales S. J., et al. (2010). TULP3 Bridges the IFT-A Complex and Membrane Phosphoinositides to Promote Trafficking of G Protein-Coupled Receptors into Primary Cilia. Genes Dev. 24, 2180–2193. 10.1101/gad.1966210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykytyn K., Sheffield V. C. (2004). Establishing a Connection between Cilia and Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. Trends Molecular Medicine 10, 106–109. 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooms L. M., Horan K. A., Rahman P., Seaton G., Gurung R., Kethesparan D. S., et al. (2009). The Role of the Inositol Polyphosphate 5-phosphatases in Cellular Function and Human Disease. Biochem. J. 419, 29–49. 10.1042/bj20081673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal K., Hwang S.-h., Somatilaka B., Badgandi H., Jackson P. K., DeFea K., et al. (2016). Smoothened Determines β-arrestin-mediated Removal of the G Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr161 from the Primary Cilium. J. Cel Biol 212, 861–875. 10.1083/jcb.201506132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T. J., Haigo S. L., Wallingford J. B. (2006). Ciliogenesis Defects in Embryos Lacking Inturned or Fuzzy Function Are Associated with Failure of Planar Cell Polarity and Hedgehog Signaling. Nat. Genet. 38, 303–311. 10.1038/ng1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikova O. V., Seo S., Cottle D. L., Conduit S., Hakim S., Dyson J. M., et al. (2015). INPP5E Interacts with AURKA, Linking Phosphoinositide Signaling to Primary Cilium Stability. J. Cel Sci 128, 364–372. 10.1242/jcs.161323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu H., Fujisawa S., Nozaki S., Katoh Y., Nakayama K. (2021). Interaction of INPP5E with ARL13B Is Essential for its Ciliary Membrane Retention but Dispensable for its Ciliary Entry. Biol. open 10, bio057653. 10.1242/bio.057653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran J., Li H., Zhang Y., Yu F., Yang Y., Nie C., et al. (2021). A Non-mitotic Role for Eg5 in Regulating Cilium Formation and Sonic Hedgehog Signaling. Sci. Bull. 66, 1620–1623. 10.1016/j.scib.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringers C., Olstad E. W., Jurisch-Yaksi N. (2020). The Role of Motile Cilia in the Development and Physiology of the Nervous System. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190156. 10.1098/rstb.2019.0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. J., May-Simera H., Eichers E. R., Kai M., Hill J., Jagger D. J., et al. (2005). Disruption of Bardet-Biedl Syndrome Ciliary Proteins Perturbs Planar Cell Polarity in Vertebrates. Nat. Genet. 37, 1135–1140. 10.1038/ng1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schou K. B., Pedersen L. B., Christensen S. T. (2015). Ins and Outs of GPCR Signaling in Primary Cilia. EMBO Rep. 16, 1099–1113. 10.15252/embr.201540530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Ma Z., Zhang G., Wang C., Jiao Z. (2019). Novel Functions of the Primary Cilium in Bone Disease and Cancer. Cytoskeleton 76, 233–242. 10.1002/cm.21529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Potchanant E. A., Cerabona D., Sater Z. A., He Y., Sun Z., Gehlhausen J., et al. (2017). INPP5E Preserves Genomic Stability through Regulation of Mitosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 37, e00500-16. 10.1128/mcb.00389-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K., Toomre D. (2000). Lipid Rafts and Signal Transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol 1, 31–39. 10.1038/35036052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla V., Reiter J. F. (2006). The Primary Cilium as the Cell's Antenna: Signaling at a Sensory Organelle. Science 313, 629–633. 10.1126/science.1124534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow J. J., Ou G., Gunnarson A. L., Walker M. R. S., Zhou H. M., Brust-Mascher I., et al. (2004). Two Anterograde Intraflagellar Transport Motors Cooperate to Build Sensory Cilia on C. elegans Neurons. Nat. Cel Biol 6, 1109–1113. 10.1038/ncb1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Zhou J., Zhou J. (2020). Primary Cilia in Corneal Development and Disease. Zoolog. Res. 41, 495–502. 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Narita K. (2012). Structure and Function of Vertebrate Cilia, towards a New Taxonomy. Differentiation 83, S4–S11. 10.1016/j.diff.2011.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Wright K. J., Corre S. L., Micalizzi A., Romani M., Abhyankar A., et al. (2014). A HomozygousPDE6DMutation in Joubert Syndrome Impairs Targeting of Farnesylated INPP5E Protein to the Primary Cilium. Hum. Mutat. 35, 137–146. 10.1002/humu.22470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toriello H. V., Parisi M. A. (2009). Cilia and the Ciliopathies: an Introduction. Am. J. Med. Genet. 151c, 261–262. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe M., Yoshimura H., Arjunan S. N. V., Kaizu K., Takahashi K. (2020). Signaling Activations through G-Protein-Coupled-Receptor Aggregations. Phys. Rev. E 102, 032413. 10.1103/PhysRevE.102.032413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. L., Li C., Kida K., Inglis P. N., Mohan S., Semenec L., et al. (2011). MKS and NPHP Modules Cooperate to Establish Basal Body/transition Zone Membrane Associations and Ciliary Gate Function during Ciliogenesis. J. Cel Biol. 192, 1023–1041. 10.1083/jcb.201012116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q., Zhang Y., Wei Q., Huang Y., Hu J., Ling K. (2016). Phosphatidylinositol Phosphate Kinase PIPKIγ and Phosphatase INPP5E Coordinate Initiation of Ciliogenesis. Nat. Commun. 7, 10777. 10.1038/ncomms10777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Wang Z., Peng H., Ward S. M., Hennig G. W., Zheng H., et al. (2021). Oviductal Motile Cilia Are Essential for Oocyte Pickup but Dispensable for Sperm and Embryo Transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. United States America 118, e2102940118. 10.1073/pnas.2102940118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Liu Z., Jia J. (2021). Mechanisms of Smoothened Regulation in Hedgehog Signaling. Cells 10, 2138. 10.3390/cells10082138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Giacalone J. C., Searby C., Stone E. M., Tucker B. A., Sheffield V. C. (2019). Disruption of RPGR Protein Interaction Network Is the Common Feature of RPGR Missense Variations that Cause XLRP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 1353–1360. 10.1073/pnas.1817639116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]