Abstract

Individuals with a history of opioid use are disproportionately represented in Illinois jails and prisons and face high risks of overdose and relapse at community reentry. Case management and peer recovery coaching are established interventions that may be leveraged to improve linkage to substance use treatment and supportive services during these critical periods of transition. We present the protocol for the Reducing Opioid Mortality in Illinois (ROMI), a type I hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomized trial of a case management, peer recovery coaching and overdose education and naloxone distribution (CM/PRC+OEND) critical time intervention (CTI) compared to OEND alone. The CM/PRC+OEND is a novel, 12-month intervention that involves linkage to substance use treatment and support for continuity of care, skills building, and navigation and engagement of social services that will be implemented using a hub-and-spoke model of training and supervision across the study sites. At least 1,000 individuals released from jails and prisons spanning urban and rural settings will be enrolled. The primary outcome is engagement in medication for opioid use disorder. Secondary outcomes include health insurance enrollment, mental health service engagement, and rearrest/recidivism, parole violation, and/or reincarceration. Mixed methods will be used to evaluate process and implementation outcomes including fidelity to, barriers to, facilitators of, and cost of the intervention. Videoconferencing and other remote processes will be leveraged to modify the protocol for safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results of the study may improve outcomes for vulnerable persons at the margin of behavioral health and the criminal legal system.

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2018, more than 2,000 Illinois residents died from opioid overdose, twice the annual toll observed before 2014 (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2020; Chicago Department of Public Health [CDPH], 2020). While cities account for most such fatalities, Illinois’ highest rates of increase were observed in rural counties (Illinois Department of Public Health, 2017). Despite widespread opioid prescribing, Illinois’ southern region features minimal access to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), with only one licensed opioid treatment program in a 16-county area (Illinois Department of Human Services, 2020).

Individuals who use opioids are disproportionately represented in the corrections system. People exiting jails and prisons face escalated risks of opioid use relapse, renewed offending, and mortality immediately post-incarceration (Binswanger, et al., 2013). An estimated one in twenty criminal-legal referred adults with opioid use disorder (OUD) receive medication, despite MOUD being standard of care (Krawczyk, et al., 2017). The Reducing Opioid Mortality in Illinois (ROMI) study seeks to test the effectiveness of a critical time intervention (CTI) linking individuals with a history of OUD post incarceration to MOUD. ROMI employs case management and peer recovery coaching (CM/PRC) to provide support and service linkages upon release in rural and urban settings.

1.1. Study Frameworks

1.1.1. Critical Time Intervention (CTI) of Case Management and Peer Recovery Coaching

CTI assists vulnerable individuals (Shaw et al., 2017) during critical transitions. In ROMI CTI is delivered by CM/PRCs who will forge and reinforce collaborative relationships with formal (e.g., mental health, corrections, drug treatment, and entitlement programs) and informal (e.g., churches, local businesses, and friends/family members) interventions and ties after release (Shaw et al., 2017). CMs will focus on “service linkages” such as insurance and MOUD navigation. PRCs will provide interpersonal support such as motivational interviewing for individuals to overcome recovery barriers.

1.1.2. Hub-and-Spoke Training and Supervision

The hub-and-spoke organizational design arranges service delivery into a network of a full-service facility, or “hub,” complemented by secondary facilities, or “spokes” with established mechanisms to route patients between hubs and spokes (Brooklyn & Sigmon, 2017, Elrod & Fortenberry, 2017). ROMI adapts this model with centralized infrastructure that extends resources, training, technical assistance, administrative support, and clinical supervision to each site’s CM/PRC team.

1.1.3. Type I Hybrid Effectiveness-Implementation Clinical Trial Design

This type I hybrid design will investigate both ROMI’s intervention effectiveness and implementation (Curran et al., 2012). The design tests outcome effects while observing and gathering implementation information. Evaluation of CM/PRC implementation is essential, as services will be delivered in varied study settings across Illinois. Rather than sequential evaluation of efficacy followed by implementation studies, the type I hybrid design will yield information on site-specific barriers and facilitators, and illuminates modifications to optimize ROMI for real-world implementation. Our implementation evaluation employs a robust fidelity monitoring plan, the Stages of Implementation Change (SIC) framework, a valid and reliable measure to track time spent from start to completion across eight stages (Saldana, 2014), and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a comprehensive determinants framework, to understand multi-level factors affecting implementation success (Damschroder et al., 2009). Costs will be examined using the Costs of Implementing New Strategies (COINS) tool (Saldana, et al., 2013), and micro-costing of CM/PRC activities.

While our team has previously deployed CM/PRC and CTI to improve outcomes for criminal-legal involved individuals, ROMI is innovative in the implementation of such interventions using a video-conferencing hub and spoke model of supervision; this is an unintended strength in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Systematic evaluation of factors impacting delivery in rural and urban settings and protocol adaptations related to aspects of virtual service provision will be an additional benefit to the hybrid study design.

2. METHODS

2.1. Overview

ROMI (NIDA 1UG1DA050066) is a 5-year study led by University of Chicago investigators in partnership with the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Community Outreach Intervention Projects and Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority. ROMI is one of twelve grants awarded within the NIDA Justice Community Opioid Innovation Network (JCOIN) to support research on OUD treatment in criminal legal settings nationwide.

2.2. Study Aims

- Aim 1: Compare the effectiveness of a CM/PRC CTI plus overdose education and naloxone distribution (CM/PRC+OEND) as compared to OEND alone on MOUD treatment engagement using a type I hybrid effectiveness-implementation randomized trial design.

- Aim 1a: Secondary effectiveness outcomes include insurance enrollment, mental health services engagement, and re-arrest.

- Aim 1b. Examine urban-rural differences in treatment engagement and retention and subsequent outcomes.

Aim 2: Evaluate the implementation and process outcomes, including measures of fidelity to, barriers to, facilitators of, and cost of the intervention.

We will randomize at least 1,000 individuals leaving jails and prisons in Illinois with OUD, across five geographically distinct sites in urban to rural settings.

2.3. Hypothesis

We hypothesize that a unified CM/PRC+OEND approach would improve MOUD treatment engagement and retention, insurance enrollment, use of mental health services and decrease re-arrest.

2.4. Procedures: Randomized Clinical Trial

2.4.1. CM/PRC+OEND Condition

CM/PRC + OEND activities include: 1) immediate connection to services as participants re-enter the community; 2) establishment of caseworker-participant relationships before re-entry; 3) support for uninterrupted linkage to OUD treatment, 4) identification of short and long-term goals, 5) skills building for independent pursuit and self-advocacy of services, and 6) OEND.

CM/PRCs are providers from the local spokes whereas the clinical and administrative supervisors are employed at the hub. All CM/PRC training will be provided by the hub and will include 17 sessions covering case management basics, CTI, working with criminal legal-engaged individuals, trauma-informed care, harm reduction, motivational interviewing, infectious diseases, MOUD, stigma, and co-occurring disorders. Refresher trainings will be informed by fidelity evaluations. Clinical supervisors will provide bi-weekly support to each CM/PRC team and administrative supervisors will provide operations and coordination support.

CM/PRCs will work directly on-site at jails, community organizations or other locations that best facilitate access to the intervention participants. During the initial intake, the CM will identify primary, secondary, and tertiary barriers to treatment initiation and completion, create an individually tailored action plan, and provide OEND. Teams will provide follow-up phone calls and home visits to facilitate service linkages. Contact frequency will depend on participants’ individual barriers, but will include at least weekly check-ins for first six months, followed by monthly check-ins.

PRCs with lived experience of opioid use may face elevated relapse risk, particularly if they are recently recovered or lack access to a support system. All PRCs will have readily available support resources, including colleagues with lived experience with whom they may discuss their recovery and wellbeing, clinical supervisors who have experience providing recovery support and referrals to additional resources, and a licensed clinical social worker assigned to providing crisis management for the ROMI team. ROMI CMs and PRCs can access the UIC Employee Assistance Program, which provides free professional confidential assessments, counseling and follow-up for employees and their families who are experiencing a broad range of mental or behavioral health concerns and life challenges.

2.4.2. OEND Condition

Individuals randomized to the OEND condition will be trained on naloxone administration by research staff at the time of randomization. Participants will be given a naloxone kit and information on local harm reduction resources, MOUD, and supportive services.

2.4.3. Study Setting

Research staff will recruit participants leaving Illinois county jails and prisons that represent a spectrum of urban, suburban and rural settings that span nearly 400 miles across the state.

2.4.4. Participants and Eligibility

We plan to enroll at least 1000 participants who are at least 18 years old, English-speaking, able to provide consent, and reside in or have anticipated return to select Illinois counties and catchment areas. Participants must satisfy criteria for likely OUD based upon nonmedical use of prescription opioids, heroin, or synthetic opioids. In particular, individuals are eligible for study participation if they score six or higher on the DAST-10 for likely OUD, or if they satisfy OUD screening criteria based on a computer-assisted screener (NIDA CTN Common Data Elements; Skinner, 1982). Individuals who have received OUD treatment within two years would also be eligible.

2.4.5. Recruitment and Screening:

Recruitment will occur in designated consultation areas in each correctional facility, e.g. medical units, treatment program spaces, and living spaces. Potential participants may be referred by correctional staff and medical providers. Alternatively, research staff stationed in designated areas will collaborate with correctional staff to approach and recruit eligible individuals. Flyers and online postings will be posted.

2.4.6. Informed Consent

Consent forms will clearly indicate that participation is voluntary and will not impact living conditions or opportunities during custody, criminal-legal status, charges, likelihood of conviction, sentence, or conditions of parole or probation. A teach-back method will be implemented to ensure participant understanding. Consent forms have been approved by the IRB and the Federal Office of Human Research Protection.

2.4.7. Randomization

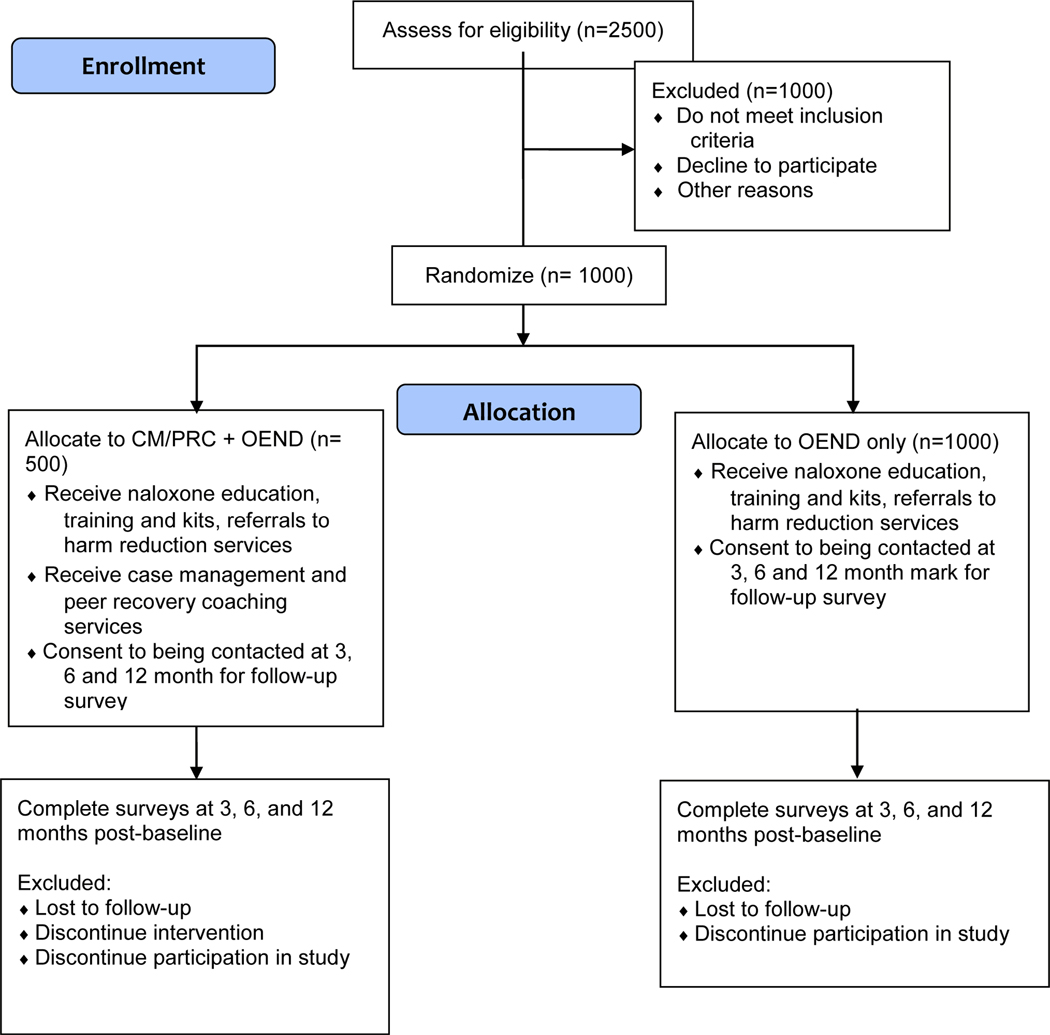

Following registration and baseline assessment, all participants will undergo randomization by research staff into the CM/PRC + OEND or OEND-only arms, stratified by site. Each site will have 100 CM/PRC + OEND and at-least 100 OEND participants. Research staff will directly link participants to CM/PRC staff at the time of randomization (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

ROMI CONSORT Flow Diagram for an assumed sample size of 1,500).

2.4.8. Baseline and Follow up Assessments

Research staff will consent and administer baseline assessment within 30 days of screening. Baseline assessment includes survey modules assessing socio-demographic information, quality of life, risk behaviors, substance use, treatment utilization and preferences, criminal legal involvement, and the Computerized Adaptive Test for Mental Health (CAT-MH) (Gibbons et al., 2019; Gibbons & deGruy, 2019; Gibbons et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2019). Surveys will be administered on password-protected, WIFI-enabled tablets using REDCap (Harris et al., 2009).

Follow-up assessments will be performed by research staff at 3, 6, and 12-months post-enrollment. Arrest records in the Illinois Criminal History Record Information (CHRI) System will be used in statistical analyses of rearrests. Illinois Department of Corrections data will be used to explore reincarceration. For confidentiality, these data will not be available to CM/PRCs.

2.4.9. Outcomes

Our primary outcome is MOUD treatment engagement, defined as two or more provider encounters and/or filled prescription in the 30 days prior to follow up assessment. Data for treatment engagement will be based on self-report using a harmonized survey instrument developed across JCOIN hubs. We will also access records from treatment providers.

Secondary outcomes include health insurance enrollment, mental health service engagement, and recidivism defined by probability and count of subsequent arrest, probation or parole violation, or reincarceration. The time frame for outcome assessments is 12 months.

2.4.10. Adverse Events (AEs)

AEs are specified in the data safety and monitoring plan and include loss of confidentiality, overdose, arrest, hospitalization or emergency department visit, and death. PI’s determination of relatedness to the study will be based upon the temporal relationship of the event to the study, a plausible pathway between the event and study, reasonable alternative explanations, and estimated baseline prevalence of the AE. Serious AEs will be reported to NIDA through a common reporting system for all JCOIN hubs.

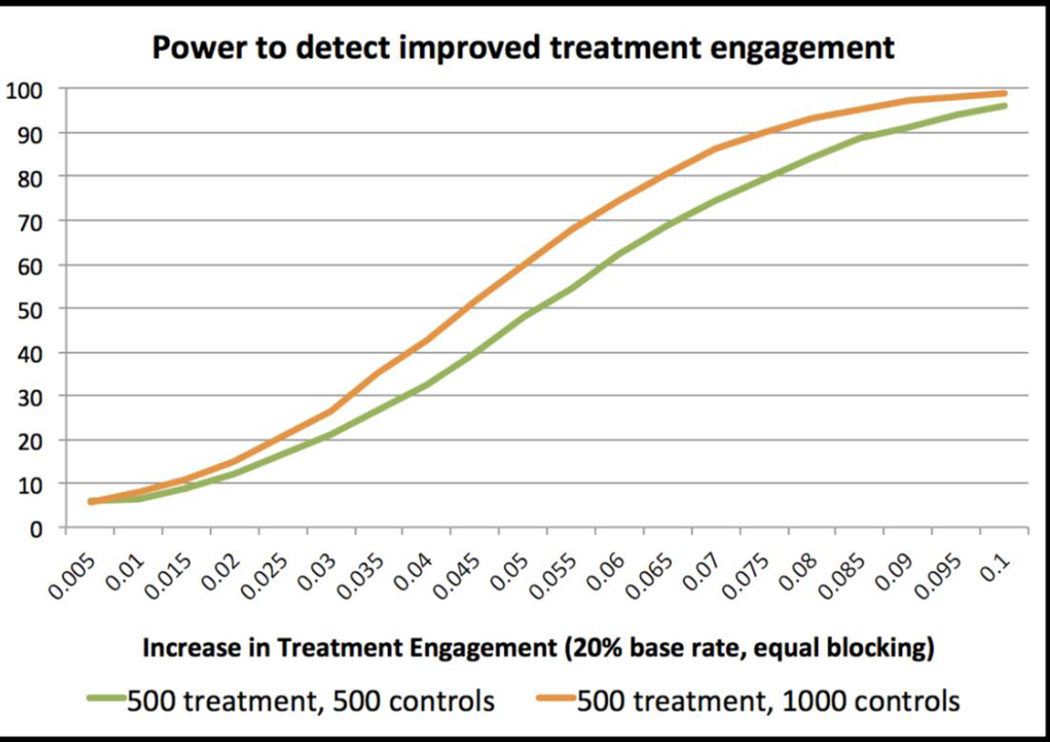

2.4.11. Sample size and statistical power

We used Monte Carlo simulations to examine our ability to detect primary and secondary outcomes, modeling MOUD uptake as a binary variable. Assuming 20% uptake within the OEND group, we find 80% power to detect an 8.0 percentage-point increase, and 90% power to detect a 9.0 percentage-point increase in uptake. Doubling each site’s control group to 200 modestly increases power. We will therefore explore opportunities to expand the control group, keeping the treatment group at n=500 given resource constraints (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Power calculation for MOUD treatment engagement outcome

We examined statistical power for our secondary arrest outcome, using data from detainees with self-reported drug use studied in the Supportive Release Center trial (Meltzer, et al 2020). In this sample, re-arrests are negative-binomially distributed with mean 1.0 rearrests/yr, and variance 4.0. (Baseline covariate adjustments likely improve power. We did not model this, given state-wide data limitations.) We find 80% power to detect reductions of 0.34 arrests/yr, and 90% power to detect reduction of 0.38 arrests/yr. Again, 2:1 control to treatment ratio modestly increases power.

2.4.12. Piloting

We will pilot at one study site to examine feasibility and acceptability. Pilot data will inform protocol modifications including recruitment, mechanisms to optimize hand offs to CM/PRCs, and strategies to improve engagement and retention given COVID-19 related limitations on in-person activities.

2.5. Community Partner Engagement

Individuals with lived experience, local criminal justice leaders, and treatment providers will provide guidance and perspective at all implementation stages. Longitudinal engagement through regular site visits allows for priority setting and alignment of ROMI interventions with extant services. Three community advisory boards comprised of persons with lived experience with SUD and the criminal legal system based in urban, suburban and rural areas serve as sounding boards for study activities and community feedback (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Israel, et al,, 1998; Chene et al., 2005; Newman et al., 2011).

2.6. Process and Implementation Evaluation

2.6.1. Eligibility and Recruitment

Staff participants involved in process and implementation evaluation (interviews, focus group, and surveys) will be over age 18, English-speaking, and will include CM/PRC staff and key stakeholders, i.e., organizational leaders, mental health providers, SUD treatment providers, harm reduction providers, prison/jail and community corrections staff. Staff participants will be recruited through a voluntary convenience sample referred by study leadership, as well as corrections and treatment partners.

2.6.2. Implementation Outcomes and Measures

The primary implementation outcome is fidelity to the ROMI intervention model, as measured by the level of adherence and competence that each CM and PRC demonstrate with respect to delivering client services aligned with ROMI principles. To assess fidelity to the CTI model, CM/PRCs will record the timing, frequency and type of services delivered, which will be evaluated relative to client acuity. All CM/PRCs will receive monthly group case consultation, which will be recorded. We will use behavioral rehearsal in CM and PRC case consultation groups as a feasible and generalizable approach to assess fidelity (Beidas, et al., 2014). Analogue fidelity will be rated using adapted versions of fidelity instruments in the following domains: (1) motivational interviewing (Moyers et al., 2016), (2) harm reduction, and (3) trauma-informed care. To further assess relational competence within motivational interviewing, ROMI participants will complete a post-intervention measure assessing their perceptions of the degree to which their PRC and CM is autonomy supportive (Simmons, et al., 1995). Fidelity will be evaluated by site and all fidelity ratings will be conducted by staff not associated with implementing the intervention.

Secondary implementation outcomes will include quantitative and qualitative data on site-specific implementation and stakeholder feedback on intervention feasibility and sustainability. Time spent from start to completion across eight implementation stages will be entered into the SIC website (http://www.sic.oslc.org), allowing real-time observation of activities completed, time spent, and the proportion of activities completed in each stage (See Table 1). These data can be used to benchmark future replication of ROMI. Using the CFIR, members of the implementation evaluation team will conduct focus groups and interviews with intervention staff after the pilot, then every 6 months. Intervention staff will rate satisfaction with training and support (Tello, et al., 2006), and intervention staff and key stakeholders will complete surveys at baseline and study end. The baseline survey will assess MOUD attitudes (Knudsen, et al.,, 2005), organizational climate (Lehman, et al,, 2002) and readiness for implementation (Shea Jacobs, et al., 2014). The second survey will include items on intervention acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility (Weiner et al., 2017) and sustainability (Luke Calhoun, et.al., 2014).

Table 1:

Sample Activities, Stages of Implementation Completion (SIC) for Reducing Opioid Mortality in Illinois (ROMI) Intervention

| Stage | SIC Activity | Adapted ROMI Activity |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1. Engagement | Date site informed/learns that service/program is available Date of interest indicated Date agreed to consider implementation |

Date Criminal Justice Partner (CJP) informed of opportunity to participate in ROMI Date CJP indicates interest in ROMI Date CJP indicates desire to move forward with ROMI |

| 2. Consideration of Feasibility | Date of 1st site planning contact Date liaison/program champion identified to purveyor |

Date of first in-person meeting with at least one administrator at CJP site to discuss ROMI Date CJP site staff or administrator formally appointed as ROMI liaison through written communication |

| 3. Readiness Planning | Date of staff sequence, timeline, hire plan review Date written implementation plan completed |

Date of first planning meeting to discuss staff qualifications and hiring timeline Date written ROMI implementation plan completed |

| 4. Staff hired and trained | Date first clinical staff hired Date expert consultant assigned to site |

Date first service staff member hired/assigned Date ROMI implementation leader/clinical supervisor hired |

| 5. Adherence monitoring processes in place | Date fidelity system training held Dates of first “developer”/Program Administrator call |

Date of initial fidelity review team training Date of first post-recruitment call with each CJP site liaison |

| 6. Services and consultation begin | Date first client served Date of first consultation call |

Date first client meets with a ROMI service staff member Date of first group phone supervision with clinician supervisor |

| 7. Ongoing services, consultation, fidelity monitoring and feedback | Date implementation review #2 Date program fidelity assessment |

Second date CFIR interview data collected to document implementation Date of first fidelity assessment |

| 8. Competency | Date first non-supervisory clinical staff certified | Date first peer recovery coach meets both conditions: (1) certified in coaching and (2) trained in MOUD knowledge. |

3. COVID-19 PROTOCOL MODIFICATIONS

Study protocols were adapted to promote staff and participant safety, accommodate organizational demands of the correctional system and other partners, and to address the declining census of correctional sites. Modifications will be reviewed during the pilot prior to all site implementation. The training schedule for CM/PRC staff was adapted to interactive video-conferencing. We will implement all supervision online. Research staff may recruit participants recently- released from incarceration (up to 2 months) through referral from community organizations, community corrections and public defenders. Research staff will contact potential participants remotely to determine eligibility, obtain informed consent, enroll and randomize participants. Naloxone kits, cell phones for those who need them, and harm reduction materials will be mailed to an address of participants’ choosing or picked up at designated locations. All data collection for efficacy and implementation evaluation will be remote. Consent and surveys will be conducted via REDCap (Harris et al., 2009). As COVID-19 is impacting organizational response times, the interpretation of completion dates within the SIC will be contextualized for future implementation, a feature that the Oregon Social Learning Center is currently developing.

4. Limitations

Potential enrollment challenges include declines in jail and prison populations and facility restrictions prohibiting on-site study staff. We have modified our protocol to include community-based recruitment. While participants randomized to OEND will receive less interaction than the CM/PRC arm, the purpose of OEND is to honor our team’s ethical obligations to participants, not to provide an equivalent experience in both arms. Potential confounders include differential availability of MOUD, mental health treatment, and other services across study sites. Policing practices may also differ and impact rates of re-arrest. Randomization as well as CFIR evaluation of contextual barriers in the outer setting will be important to understand whether the intervention impact could be diminished or outsized when baseline resources are limited.

5. DISCUSSION OF POTENTIAL STUDY IMPACT

ROMI will examine the efficacy of a case manager/peer recovery coach critical time intervention in assisting individuals leaving jails and prisons who face high risks of overdose, relapse and re-arrest. We utilize an innovative hub-and-spoke structure for centralized training and supervision of the intervention and will evaluate implementation to inform future replication in different settings. This approach is responsive with the barriers imposed by COVID-19—a pandemic which lays bare systemic deficiencies that exist for communities experiencing disproportionate disease and which poses a profound threat to individuals at the intersection of addiction and the criminal legal system.

Highlights.

Reducing Opioid Mortality in Illinois (ROMI) is a randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of hub and spoke case management and peer recovery coaching services on individuals involved in the criminal legal system upon release from jail or prison.

Procedures critical to the success of the project include community partner engagement and implementation evaluation.

Multiple modifications to protocol are being considered and implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

ROMI hopes to inform the treatment of vulnerable persons at the intersection of addiction and the criminal legal system.

Author Statement

Below are our team members’ contributions to the submitted manuscript. All categories alphabetical.

| Item | Team member |

|---|---|

| Conceptualization | Boodram, Bouris, Claypool, Epperson, Erzouki, Gastala, Jimenez, Pineros, Pho, Pollack, Salisberry-Afshar, Schneider, Shuman |

| Methodology | Bouris, Claypool, Pho, Pollack, Reichert |

| Investigation | Boodram, Bouris, Claypool, Erzouki, Gastala, Jimenez, Pineros, Pho, Pollack, Reichert, Schneider, Shuman |

| Resources | Kelly, Gibbons, Reichert |

| Data Curation | Bouris, Claypool, Erzouki, Reichert |

| Writing-Original draft | Boodram, Bouris, Claypool, Epperson, Erzouki, Pho, Pollack, Salisberry-Afshar, Schneider |

| Writing-Review and editing | Boodram, Bouris, Claypool, Jimenez, Pineros, Pho, Pollack, Salisberry-Afshar, Schneider, Shuman |

| Funding Acquisition | Pho, Pollack, Schneider |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mai Pho, Department of Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases and Global Health, University of Chicago Medical Center, 5841 S. Maryland, MC 5065, Chicago, IL 60637, United States; Medical Advisor for Health Research and Policy, Illinois Department of Public Health, 69 W Washington St, Suite 35 Chicago, IL 60307.

Farah Erzouki, University of Chicago Urban Labs, 33 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 1600, Chicago, IL 60602, United States.

Basmattee Boodram, School of Public Health, Division of Community Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor Street, 689 SPHPI, MC923, Chicago, IL 60612, United States.

Antonio D. Jimenez, Community Outreach Intervention Projects, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor Street, 851 SPHPI, MC 923, Chicago, IL 60612, United States.

Juliet Pineros, Community Outreach Intervention Projects, School of Public Health, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor Street, 856 SPHPI MC 923, Chicago, IL 60612, United States.

Valery Shuman, JCOIN ROMI project, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1603 W. Taylor Street, SPHPI MC 923, Chicago, IL 60612, United States.

Emily Jane Claypool, Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy and Practice, The University of Chicago, 969 E. 60th St, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

Alida M. Bouris, Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy and Practice, Co-Director, Chicago Center for HIV Elimination, Co-Director, Behavioral, Social, and Implementation Sciences, Core, Third Coast Center for AIDS Research, Co-Director, Transmedia Story Lab, Ci3, The University of Chicago, 969 E 60th St, Chicago, IL 60637, United States; Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, Center for Human Potential and Public Policy, Ci3: Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry and Innovation in Sexual and Reproductive Health, The University of Chicago.

Nicole Gastala, University of Illinois at Chicago Mile Square Health Center 1220 S. Wood St., Chicago, IL 60608, United States.

Jessica Reichert, Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, 300 W. Adams St. Suite 200, Chicago, IL 60606, United States.

Marianne Kelly, Community Resource Center (CRC), Cook County Sheriff’s Office, 50 W. Washington St, Rm 701, Chicago, IL 60602, United States.

Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin Madison, School of Medicine and Public Health, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715, United States.

Matthew W. Epperson, Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, The University of Chicago, E. 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

Robert D. Gibbons, Department of Medicine and Public Health Sciences (Biostatistics), Director, Center for Health Statistics, Faculty Associate, Department of Comparative Human Development, Founding Member, Committee on Quantitative Methods in Social Behavioral and Health Sciences, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Avenue, MC 2007, Office W260, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

John A. Schneider, Department of Medicine and Public Health Sciences, The University of Chicago, 5841 S. Maryland Ave MC2000, Chicago, IL 60637, United States; The Chicago Center for HIV Elimination, 5837 S. Maryland Ave, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

Harold A. Pollack, Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Chicago Urban Labs, Affiliate Professor, Biological Sciences Collegiate Division, 969 East 60th St, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

References

- Bagley SM, Schoenberger SF, Waye KM, & Walley AY (2019). A scoping review of post opioid-overdose interventions. Preventive Medicine, 128, 105813. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Cross W, & Dorsey S. (2014). Show me, don’t tell me: Behavioral rehearsal as a training and analogue fidelity tool. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, & Stern MF (2013). Mortality after prison release: Opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of Internal Medicine, 159(9), 592–600. 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooklyn J, & Sigmon S. (2017). Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: Development, implementation, and impact. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 11(4), 286–292. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Principles of community engagement. 2nd Ed. CDC/ATSDRCommittee on Community Engagement. Available from: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityen-gage-ment/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf [cited August 20, 2020] [Google Scholar]

- Chene R, Garcia L, Goldstrom M, Pino M, Roach DP, Thunderchief W, & Waitzkin H. (2005). Mental health research in primary care: Mandates from a community advisory board. Annals of Family Medicine, 3(1), 70–72. 10.1370/afm.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH). (2020). Opioid concerns: Increase in opioid overdose in Chicago. Health Alert. June 30, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.chicagohan.org/home?p_p_id=hanpublicalerts_WAR_hanpublicalerts. [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, & Stetler C. (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical Care, 50(3), 217–226. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science, 4(1), 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod J, & Fortenberry J. (2017). The hub-and-spoke organization design: An avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 25–33. 10.1186/s12913-017-2341-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Smith JD, Brown CH, Sajdak M, Tapia NJ, Kulik A, … & Csernansky J. (2019). Improving the evaluation of adult mental disorders in the criminal justice system with computerized adaptive testing. Psychiatric Services, 70(11), 1040–1043. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, & deGruy FV (2019). Without wasting a word: Extreme improvements in efficiency and accuracy using computerized adaptive testing for mental health disorders (CAT-MH). Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(8), 67. 10.1007/s11920-019-1053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Alegria M, Markle S, Fuentes L, Zhang L, Carmona R,… Baca-Garcia E. (2020). Development of a computerized adaptive substance use disorder scale for screening and measurement: The CAT-SUD. Addiction, 115(7), 1382–1394. 10.1111/add.14938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham AK, Minc A, Staab E, Beiser DG, Gibbons RD, & Laiteerapong N. (2019). Validation of the computerized adaptive test for mental health in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine, 17(1), 23–30. 10.1370/afm.2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn BP, Li X, Mamun S, McCrady B, & French MT (2018). The economic costs of jail-based methadone maintenance treatment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 44(6), 611–618. 10.1080/00952990.2018.1491048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IDPH. (2019). Drug overdose deaths by sex, age group, race/ethnicity and county, Illinois residents, 2013–2018. Retrieved from http://www.dph.illinois.gov/sites/default/files/Drug%20Overdose%20Deaths%20-%20August%202019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Human Services. (2020). Division of Substance Use Prevention and Recovery Licensed Sites Sorted by County/ City/ Township – CCA/Program Name. http://www.dhs.state.il.us/OneNetLibrary/27896/documents/By_Division/OASA/Licensure/LicenseDirectorybyCountyCityCCA_08232018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH). (2017). State of Illinois comprehensive opioid data report. Retrieved from http://www.dph.illinois.gov/sites/default/files/publications/publicationsdoil-opioid-data-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM, & Link T. (2005). Buprenorphine diffusion: The attitudes of substance abuse treatment counselors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 29(2), 95–106. 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk N, Picher CE, Feder KA, & Saloner B. (2017). Only one In twenty justice-referred adults in specialty treatment for opioid use receive methadone or buprenorphine. Health Affairs, 36(12), 2046–2053. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langabeer J, Champagne-Langabeer T, Luber SD, Prater SJ, Stotts A, Kirages K, …Chambers KA (2020). Outreach to people who survive opioid overdose: Linkage and retention in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 111, 11–15. 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WE, Greener JM, & Simpson DD (2002). Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 22(4), 197–209. 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke DA, Calhoun A, Robichaux CB, Elliott MB, & Moreland-Russell S. (2014). The program sustainability assessment tool: A new instrument for public health programs. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, 130184. 10.5888/pcd11.130184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer DO, et al. Conducting a Randomized Control Trial in Cook County Jail – Implementation and Methods. Association for Public Policy and Management, annual conference, 2020. https://appam.confex.com/appam/2020/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/35883 [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Rowell LN, Manuel JK, Ernst D, & Houck JM (2016). The motivational interviewing treatment integrity code (MITI 4): rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2020). Illinois: Opioid-involved deaths and related harms. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugtopics/opioids/opioid-summaries-by-state/illinois-opioid-involved-deaths-related-harms. [Google Scholar]

- Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, & Williamson DC (2011). Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(3):A70. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/may/10_0045.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA CTN Common Data Elements. (n.d.). Instrument: Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10). Retrieved August 31, 2020, from https://cde.drugabuse.gov/instrument/e9053390-ee9c-9140-e040-bb89ad433d69 [Google Scholar]

- Saldana L. (2014). The stages of implementation completion for evidence-based practice: Protocol for a mixed methods study. Implementation Science, 9(1), 1–11. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana L, Chamberlain P, Bradford WD, Campbell M, & Landsverk J. (2013). The cost of implementing new strategies (COINS): A method for mapping implementation resources using the stages of implementation completion. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 177–182. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J, Conover S, Herman D, Jarrett M, Leese M, Mccrone P, … Stevenson C. (2017). Critical time Intervention for Severely mentally ill Prisoners (CrISP): A randomised controlled trial. Health Services and Delivery Research, 5(8), 1–138. doi: 10.3310/hsdr05080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea CM, Jacobs SR, Esserman DA, Bruce K, & Weiner BJ (2014). Organizational readiness for implementing change: a psychometric assessment of a new measure. Implementation Science, 9(1), 7. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons J, Roberge L, Kendrick SB Jr, & Richards B. (1995). The interpersonal relationship in clinical practice: The Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory as an assessment instrument. Evaluation & the health professions, 18(1), 103–112. 10.1177/016327879501800108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors, 7(4), 363–371. 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tello FPH, Moscoso SC, García IB, & Chaves SS (2006). Training Satisfaction Rating Scale: Development of a measurement model using polychoric correlations. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22(4), 268. 10.1027/1015-5759.22.4.268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villapiano N, Winkelman T, Kozhimannil K, MM D, & SW P. (2017). Rural and urban differences in neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid use, 2004 to 2013. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(2), 194–196. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, … & Halko H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, & Fouts A. (2007). A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(2), 189–198. 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]