Abstract

Objective

To estimate the economic cost associated with implementing the Results Based Financing for Maternal and Newborn Health (RBF4MNH) Initiative in Malawi. No specific hypotheses were formulated ex-ante.

Setting

Primary and secondary delivery facilities in rural Malawi.

Participants

Not applicable. The study relied almost exclusively on secondary financial data.

Intervention

The RBF4MNH Initiative was a results-based financing (RBF) intervention including both a demand and a supply-side component.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Cost per potential and for actual beneficiaries.

Results

The overall economic cost of the Initiative during 2011–2016 amounted to €12 786 924, equivalent to €24.17 per pregnant woman residing in the intervention districts. The supply side activity cluster absorbed over 40% of all resources, half of which were spent on infrastructure upgrading and equipment supply, and 10% on incentives. Costs for the demand side activity cluster and for verification were equivalent to 14% and 6%, respectively of the Initiative overall cost.

Conclusion

Carefully tracing resource consumption across all activities, our study suggests that the full economic cost of implementing RBF interventions may be higher than what was previously reported in published cost-effectiveness studies. More research is urgently needed to carefully trace the costs of implementing RBF and similar health financing innovations, in order to inform decision-making in low-income and middle-income countries around scaling up RBF approaches.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, HEALTH ECONOMICS, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We estimated full economic costs of results-based financing intervention combining both supply and demand-side incentives.

We adopted activity-based costing methodology, to trace all resources and related costs associated with designing and implementing an intervention.

We identify and evaluate costs across activities and different cost categories to give a comprehensive cost assessment and overcome limitations of previous analyses.

Due to the retrospective nature of our work, it is possible that we did not capture all costs or assigned them to the respective activities as accurately as it would have been possible had we collected data prospective.

Introduction

Results-based financing (RBF) interventions are gaining increased attention as a means of improving access to care and enhancing the quality of service provision across low-income and middle-income countries.1 With specific reference to health service delivery, RBF approaches include demand-side interventions, chiefly conditional cash transfers (CCT) and supply-side interventions, most notably performance-based financing (PBF). CCT are payments to healthcare users tied to compliance with a specific health behaviour, most frequently utilisation of a given service, such as facility-based delivery or vaccinations.2 Performance-based financing refers to the implementation of performance contracts, whereby healthcare providers and/or managers are paid on the attainment of predefined quantity and quality indicators.3

The widespread implementation of RBF has drawn attention to the need to assess the costs associated with these interventions. A recent publication by Chi et al and colleagues invites the research and policy community to be mindful of the identification, measurement and validation of the costs of RBF implementation as an integral element of research to inform investments in the health sector. To date, the scientific evidence base on the costs associated with RBF is extremely limited; it is mostly generated by studies that have focused exclusively on supply-side PBF interventions, and has largely neglected the estimation of costs associated with implementing demand-side programmes, such as CCT.4 This paucity of evidence is somewhat surprising considering that demand and supply-side RBF interventions are increasingly being combined in a single programme design intended to address both sets of barriers to accessing health services.5

Moreover, the available literature suffers from two limitations. First, existing costing studies on RBF struggle to accurately trace full costs across activities and cost categories, hence, providing only limited information for policy makers as to which activities drive implementation costs.6 Second, existing studies often aim to assess cost-effectiveness, relating the costs of implementing RBF approaches to their benefits, measured in terms of improved health service utilisation and/or health gains.7–9 While cost-effectiveness studies are instrumental in enabling policy makers to select interventions that generate the greater health benefits at lower costs, the evidence they generate does not provide guidance on the full cost structure of such programmes, which is needed to inform further implementation and scale-up pilot interventions.

It is against this background that we aimed to fill the aforementioned gaps in knowledge by estimating the costs associated with implementing the Results Based Financing for Maternal and Newborn Health (RBF4MNH) Initiative in Malawi. This was an RBF intervention encompassing both a demand and a supply-side component to tackle maternal and newborn mortality by increasing access to better quality institutional delivery services. Our objective was to estimate the economic costs of the intervention, including both demand and supply-side components, clearly differentiating the costs across project phases, activities and cost categories.

Methods

Study setting

With an estimated 2020 GDP per capita of US$412 (current USD), Malawi is one of the poorest countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2010, prior to the launch of the RBF4MNH Initiative, maternal and neonatal mortality were estimated, respectively, at 639 deaths per 100 00010 and at 27 deaths per 1000 live births.11 Obstetric care services are provided through the country’s essential health package offered free of charge at public and contracted not-for-profit faith-based health facilities. Facility-based delivery utilisation rates have increased dramatically over the course of the last two decades, increasing from 55% in 2000 to 91% in 2016.12

In spite of the high rates of institutional delivery, in 2014, unmet need for emergency obstetric care (EmOC) among women with obstetric complications was estimated at 75%, given that the majority of health facilities still did not meet EmOC standards. The healthcare system was at the time, and continues to be, characterised by poor infrastructure, and severe shortages in human resources and medical supplies, largely linked to insufficient funding capacity.13 In 2013, annual per capita total health expenditure amounted to US$39,14 with donor funding covering nearly 70% of this amount.

Intervention design

The RBF4MNH Initiative has been described extensively in the literature, since sustained research efforts have been channelled towards assessing its impact on providers’ motivation,15 effective coverage,16 quality of service delivery17 18 and maternal mortality at birth.19 Hereafter, we synthetize the Initiative’s main features to allow the reader to follow the rationale of the methodological decisions we made for the cost analysis and to contextualise the findings we present.

The RBF4MNH Initiative was implemented between 2013 and 2018 by the Reproductive Health Directory (RHD) of the Ministry of Health (MoH), with financing from the Governments of Germany and Norway, and technical and management assistance by Options Consultancy Services. Initially implemented in 18 EmOC facilities, it was later expanded to a total of 33 facilities, including 28 basic EmOC facilities and 5 comprehensive EmOC facilities, distributed across four districts (Balaka, Dedza, Mchinji, Ntcheu). Not all health facilities in each district participated. The Initiative aimed at reducing maternal and neonatal deaths by targeting the quality of obstetric services, encouraging utilisation of facility-based delivery and 48 hours in-facility postpartum stays. To achieve these objectives, the Initiative included a supply and a demand-side component, specifically: (a) performance contracts with health facilities and district health management teams (DHMTs) linked to defined obstetric and neonatal care quality and utilisation targets and (b) CCT to pregnant women arriving at a participating facility for delivery, intended as partial reimbursement for the costs associated with delivering at a health facility. An additional integral component of the RBF4MNH Initiative, setting it aside from other RBF interventions, was the investment made to support infrastructure works and supply of essential medical equipment to participating public health facilities (eg, renovation of labour rooms, construction of maternity waiting homes).

The participating facilities and the respective DHMTs received performance payments on top of the usual budget and in-kind resources (ie, staff salaries, drugs and medical supplies) allocated by central and district governments. Approximately two-thirds of performance payments could be redistributed among staff as personal incentives, while one-third was to be re-invested by the staff to support quality improvements at the facility (ie, using the funds to purchase drugs and basic supplies, hiring contract staff and paying for minor infrastructure works and repairs).

In a departure from the current system whereby health facilities are not designated as cost centres and districts are largely responsible for all expenditures related to health facility functioning, the RBF Initiative worked to enable participating health facilities to manage the additional funds acquired autonomously. Health workers were also directly in charge of disbursing the CCT to women at the facility (paid in instalments on arrival and before/after delivery), and to register women for eligibility during antenatal care.

Study design

Our retrospective cost analysis aimed at estimating the full economic cost of the RBF4MNH Initiative. Hence, we captured the full value of all resources used by any of the parties involved in the design and implementation of all activities related to the Initiative.20 We adopted a health system perspective, accounting for costs incurred by the MoH and their development and implementing partners. These included: the MoH Malawi as key implementing lead, Options Consultancy Services (providing programme management and technical assistance), the German Development Bank KfW (as co-funder) and Norwegian cooperation (represented by both Norad and the Norwegian Embassy in Lilongwe). Our analysis captures the costs incurred by the Initiative in the four concerned districts as well as costs incurred in any other relevant settings, including the capital Lilongwe, where both the MoH and the central RBF4MNH office were located, as well as London, Frankfurt and Oslo, where monitoring and oversight activities were undertaken.

Our work covers the period from 2011, the year when the initial feasibility study was commissioned marking the onset of the Initiative’s design, to 2016. Hence, our analysis covers 2 years related to the Initiative design and start-up (2011–2012) and 4 years related to its implementation (2013–2016). While the Initiative was extended into 2018, our analysis concludes at 2016, since our research funding was aligned with the initial timeline of the Initiative and could not be prolonged to match its extension. Since the Initiative was also subject to some design modifications during implementation, we continued tracing design costs for the period 2013–2016. To the extent possible, we attempted to differentiate the cost of supply-side from demand-side activities. Given the retrospective nature of the study and the lack of relevant details in the financial data at our disposal, however, this was not always possible, so some activities, such as management, are not directly attributable to either the supply-side or the demand-side component.

Data sources and data collection strategies

To trace all costs pertaining to the design and implementation of the RBF4MNH Initiative, we adopted anactivity-based costing approach. Accordingly, we started by retrospectively mapping all microlevel activities related to the design and implementation of the Initiative and then traced all resources being consumed by these activities. We completed these first two steps by reviewing the complete documentation of the intervention and engaging in a series of repeated exchanges with key stakeholders, who had been involved in the implementation of the Initiative.

To attribute value to either single resources (where possible) or complete activities (when the former was not possible), we extracted relevant cost information from the financial data of the different implementing partners. These included: (a) options’ financial data reporting central level costs related to implementation, including personnel costs; (b) the RBF4MNH Initiative financial data, reporting costs for all activities related to field implementation, including incentive payments; (c) financial data contributed by the development partners, including cost information on specific activities, such as the early feasibility study and the consultancies conducted during the course of the implementation.

To estimate resource consumption for activities that could not be traced in financial data, we conducted key informant interviews with MoH and development and implementing partners’ staff. These interviews allowed us to quantify the extent to which these staff had contributed towards the Initiative, although the value of their engagement was not directly reflected in the financial data. To value the days of work contributed by MoH staff, we used official national-level cadre-specific salary information. To value the days of work contributed by development and implementing partner staff, we used level-specific average international and national consultancy rates. In addition, to value material contributions by development partners not included in the financial data, such as flights and other transport, we used average market price items. In line with the literature, we applied a 15% overhead rate to the costs incurred by MoH, Norwegian Embassy and Norad, as well as KfW, to account for overarching costs (such as overall management) not easily traceable when accounting only for crude salaries and/or consultancy rates.

The RBF4MNH office provided us with the number of women who benefitted from the Initiative while the National Office of Statistics provided us with the number of expecting mothers estimated for the RBF4MNH district catchment areas over the 2013–2016 period. This information served as basis to compute the size of the actual and the potential beneficiary population, respectively.

Analytical approach: cost analysis

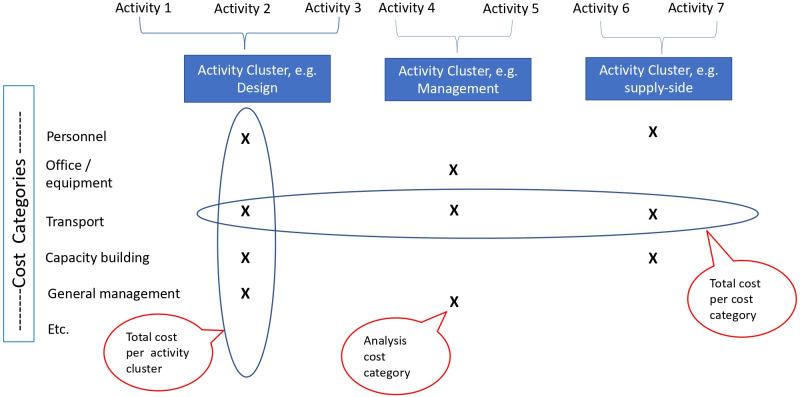

To complete the cost analysis, aggregating information across data sources, we proceeded in steps, exemplified in figure 1. First, once we had identified all single microlevel activities, we aggregated them into activity clusters, that is, a series of broader activity groups to facilitate policy appraisal of the intervention costs (see online supplemental appendix 1 for details). The activity clusters were identified in consultation with the RBF4MNH implementation team as follows: design, management, promotion, operations research, monitoring and evaluation, verification, demand-side and supply-side costs.

Figure 1.

Activity-based costing approach.

bmjopen-2021-050885supp001.pdf (144.8KB, pdf)

In order to estimate costs for each activity cluster identified above, we then adopted the following approach. We aggregated detailed cost information across specific microlevel activities into broader meaningful cost categories. Normally, cost categories refer to general cost items, such as transport, staff, office supplies, etc. In our case, however, due to the structure of the data available, we had to work with cost categories that were broader and more inclusive. Then, we further aggregated these cost categories into analysis cost categories, to draw a link between cost categories and activity clusters. We attributed analysis cost categories to the single activity clusters and then aggregated values within a given activity cluster. This process was designed to inform decision-making by indicating which broad activity area absorbed what portion of the overall costs of the Initiative.

Similar to what was reported by De Allegri et al, one challenge we faced was the attribution of staff costs to single activities. Staff costs were easily traceable to the individuals involved in implementation, but they were documented as salaries or consultancy fees and did not provide any indication of the breakdown of activities undertaken by staff who worked across more than one activity cluster. Hence, to attribute staff costs to single activity clusters, we interviewed key implementers to reconstruct their engagement in the project. We attributed all time contributed by MoH, Norway and KfW partners to general management activities, since we could confirm that staff employed at this level were not involved directly in other activities.

Finally, to allow the reader a better sense of the ‘value’ of the RBF4MNH Initiative, we computed the cost per beneficiary, accounting for both actual beneficiaries, that is, the actual number of delivering women served each year, and potential beneficiaries, that is, the expected annual total number of delivering women across the four districts, within and beyond the direct catchment areas of the intervention facilities (since mobility across catchment areas is allowed and we know that women moved to receive care at RBF4MNH facilities).

We purposely focused on costs related to the implementation of the RBF programme, including those born directly by the MoH, but excluded the costs related to the routine provision of Maternal and Child Health (MCH) services, since those did not change as a function of the introduction of RBF. Our objective was not to cost MCH service provision with or without RBF, but to look more specifically at the costs related to implementing RBF per se. Our choice is motivated by lack of adequate evidence on the costs of RBF programmes.

All costs were adjusted to the base year 2016. We used a GDP deflator for the Euro area to adjust for inflation from 2011 to 2016. The cost items expressed in local currency were converted to Euros using official yearly average conversion rates to account for the extreme fluctuations in exchange rates which occurred during the period of our analysis.

Patients and public involvement

Given the nature of the work conducted, patients and the public were not involved in any phase of the project.

Results

Table 1 presents a synthesis of the Initiative costs, across all years and all activity clusters. Under management, we purposely differentiate costs incurred by the RBF4MNH implementation unit, by the MoH and by its development and implementing partners. The overall economic cost of the Initiative for the period 2011–2016 amounted to €12 786 924. The MoH financial contribution when comparing to that of the RBF4MNH implementation unit which, while situated within the MoH, and financed by development partners was (0.04% vs 20.5% of the total costs).

Table 1.

Total costs by activity over time in four districts (real values in €, base year 2016)

| Activity cluster | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total |

| Design | 261 684 | 228 319 | 52 619 | 26 289 | 9627 | 0 | 578 537 |

| Management | 3 112 263 | ||||||

| Contracted implementation unit (set within MoH) | 69 095 | 355 224 | 347 065 | 477 790 | 537 819 | 830 828 | 2 617 821 |

| MoH own resources | 1425 | 882 | 737 | 689 | 662 | 515 | 4909 |

| Development partners (KfW, Norad) | 88 260 | 82 464 | 81 439 | 80 000 | 78 838 | 78 532 | 489 533 |

| Promotion | 2246 | 3703 | 40 300 | 58 478 | 238 202 | 278 128 | 621 058 |

| Operations research | 15 024 | 14 862 | 17 263 | 12 164 | 11 987 | 43 304 | 114 604 |

| M&E | 25 417 | 115 859 | 179 822 | 154 114 | 156 171 | 107 590 | 738 973 |

| Verification | 0 | 0 | 59 803 | 157 818 | 321 833 | 207 956 | 747 410 |

| Demand side | 8103 | 45 752 | 269 044 | 290 987 | 574 657 | 507 354 | 1 695 897 |

| Supply side | 30 136 | 173 001 | 1 105 949 | 1 340 743 | 1 423 795 | 1 104 558 | 5 178 181 |

| Total by year | 501 390 | 1 020 064 | 2 154 041 | 2 599 073 | 3 353 592 | 3 158 765 | 12 786 924 |

M&E, monitoring and evaluation; MoH, Ministry of Health.

Table 2 differentiates costs between the start-up (all costs incurred in 2011–2012 period) and the implementation phase (all costs incurred in 2013–2016 period), with start-up costs absorbing €1 521 454 and implementation costs across the 4 years we followed absorbing a total of €11 265 470. Implementation costs rose in the initial years, but then stabilised and started to decrease by 2016. Reflecting the pattern observed for total costs, implementation costs per beneficiary increased in the early years, but stabilised and started to decrease in 2016.

Table 2.

Total start-up and implementation costs by year in four districts (real values €, base year 2016)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | |

| Start-up costs | 501 390 | 1 020 064 | 1 521 454 | ||||

| Implementation costs | 2 154 041 | 2 599 073 | 3 353 592 | 3 158 765 | 11 265 470 | ||

| Expected births (beneficiaries) (n) | 111 181 | 114 739 | 118 283 | 121 838 | 466 041 | ||

| Women served per year (n) | 28 042 | 41 801 | 52 399 | 57 948 | 180 190 | ||

| Implementation cost by potential beneficiary | 19.37 | 22.65 | 28.35 | 25.93 | 24.17 | ||

| Implementation cost by actual beneficiary | 76.81 | 62.18 | 64.00 | 54.51 | 62.52 |

Combining start-up and implementation costs, table 3 shows which activity cluster absorbed which portion of total costs and which analysis cost category contributed towards each activity. The supply side activity cluster absorbed over 40% of all resources devoted to the project. Within this figure, the incentives only represented approximately 10% of the total value of this activity while considerable infrastructural investment represented nearly half. In 2016, once the programme reached full maturity, the value of the incentives relative to the total value of the supply side activity cluster increased substantially, reaching one-third of the overall value of the activity.

Table 3.

Costs by activity cluster, cost category and by year (real values in €, base year 2016)

| Activity cluster | Analysis cost category | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total | % of total cost |

| Design | Personnel | 58 541 | 228 319 | 52 619 | 26 289 | 9627 | 0 | 375 394 | |

| Feasibility study | 203 143 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 203 143 | ||

| Total by year | 261 684 | 228 319 | 52 619 | 26 289 | 9627 | 0 | 578 537 | 4.52 | |

| Management | Personnel | 83 069 | 167 956 | 195 200 | 180 326 | 172 410 | 187 107 | 986 069 | |

| External audit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3760 | 3760 | ||

| Capacity building | 0 | 0 | 20 704 | 84 902 | 153 830 | 394 662 | 654 099 | ||

| Office/equipment | 18 584 | 97 812 | 41 899 | 46 385 | 49 342 | 103 218 | 357 241 | ||

| General management | 17 916 | 12 810 | 62 575 | 105 746 | 150 134 | 140 438 | 489 619 | ||

| Transport/accommodation | 39 211 | 159 992 | 108 862 | 141 118 | 91 604 | 80 689 | 621 475 | ||

| Total by year | 158 780 | 438 570 | 429 240 | 558 479 | 617 319 | 909 875 | 3 112 263 | 24.34 | |

| Promotion | Personnel | 2246 | 3703 | 35 600 | 40 685 | 47 884 | 54 400 | 184 519 | |

| Awareness campaign | 0 | 0 | 4700 | 17 793 | 190 318 | 223 728 | 436 540 | ||

| Total by year | 2246 | 3703 | 40 300 | 58 478 | 238 202 | 278 128 | 621 058 | 4.86 | |

| Operation research | Personnel | 15 024 | 14 862 | 14 677 | 12 164 | 11 987 | 11 804 | 80 518 | |

| Operation research | 0 | 0 | 2586 | 0 | 0 | 31 500 | 34 086 | ||

| Total by year | 15 024 | 14 862 | 17 263 | 12 164 | 11 987 | 43 304 | 114 604 | 0.90 | |

| M&E | Personnel | 25 417 | 115 859 | 79 251 | 87 514 | 66 147 | 65 790 | 439 977 | |

| Baseline assessment | 0 | 0 | 72 622 | 16 399 | 17 480 | 0 | 106 502 | ||

| Capacity building | 0 | 0 | 27 949 | 50 201 | 72 543 | 41 800 | 192 494 | ||

| Total by year | 25 417 | 115 859 | 179 822 | 154 114 | 156 171 | 107 590 | 738 973 | 5.78 | |

| Verification | Personnel | 0 | 0 | 38 452 | 34 104 | 35 275 | 37 192 | 145 023 | |

| Agent | 0 | 0 | 20 628 | 123 715 | 82 167 | 159 347 | 385 857 | ||

| Internal audit | 0 | 0 | 722 | 0 | 204 391 | 11 417 | 216 531 | ||

| Total by year | 0 | 0 | 59 803 | 157 818 | 321 833 | 207 956 | 747 410 | 5.85 | |

| Demand side | Personnel | 8103 | 45 752 | 89 982 | 104 773 | 111 471 | 123 972 | 484 053 | |

| Incentives | 0 | 0 | 42 701 | 128 158 | 246 210 | 159 750 | 576 819 | ||

| Capacity building | 0 | 0 | 17 882 | 58 056 | 204 592 | 136 060 | 416 590 | ||

| General management | 0 | 0 | 118 479 | 0 | 12 385 | 87 571 | 218 435 | ||

| Total by year | 8103 | 45 752 | 269 044 | 290 987 | 574 657 | 507 354 | 1 695 897 | 13.26 | |

| Supply side | Personnel | 30 136 | 173 001 | 165 311 | 108 437 | 81 060 | 85 021 | 642 964 | |

| Infrastructure investments | 0 | 0 | 698 783 | 796 371 | 583 137 | 334 021 | 2 412 312 | ||

| Equipment investment | 0 | 0 | 52 372 | 170 323 | 142 342 | 99 138 | 464 174 | ||

| Incentives | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 805 | 66 709 | 427 057 | 505 571 | ||

| Capacity building | 0 | 0 | 189 484 | 253 807 | 550 548 | 159 322 | 1 153 161 | ||

| Total by year | 30 136 | 173 001 | 1 105 949 | 1 340 743 | 1 423 795 | 1 104 558 | 5 178 181 | 40.50 | |

| Grand total | 413 130 | 937 600 | 2 072 602 | 2 519 072 | 3 274 753 | 3 080 233 | 12 786 924 |

M&E, monitoring and evaluation.

The demand side activity cluster absorbed nearly 14% of the intervention value, with incentives in this case representing nearly one-third of all activity-specific costs. Verification costs, referring exclusively to supply-side verification (since demand-side verification was incorporated in demand-side supervision), only absorbed 6% of the overall value of the intervention. Overall management costs absorbed over one-fifth of the intervention value. Design activities absorbed less than 5% of the total value of the initiative, with the cost being driven exclusively by the initial feasibility study and by personnel costs.

Table 4 presents the same cost data in a different form, looking at the cost of the single Cost Categories and pooling across costs pertaining to both the start-up and the implementation phase across all activities included in table 3. Personnel costs for contracted RBF4MNH staff represented the most substantial cost driver, absorbing nearly 23% of the intervention value. Structural investments absorbed nearly one-fourth of the intervention cost. Here, supply-side verification appears to have absorbed only slightly above 3% of the intervention costs, while in table 3, this is shown to be 6%. This difference can be explained by the fact that in table 3, we look at the value of the entire Activity Cluster, including the value of personnel time devoted towards verification. In table 4, instead, the term supply-side verification is used as a Cost Category, reflecting only the payments directly made by the implementation unit (either to external verification agencies or to district teams) to execute the verification procedures. Supply-side and demand-side incentives accounted for approximately 15% of the value of the intervention, with supply-side incentives accounting for 10% and demand-side incentives accounting for 5%.

Table 4.

Overall distribution of costs across cost categories (all years and all activities together; real values in €, base year 2016)

| Cost category | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | Total (all years) | Percentage of total costs |

| Personnel_RBF4MNH | 145 009 | 673 219 | 595 924 | 522 482 | 465 107 | 489 735 | 2 891 476 | 22.61 |

| Structural investment—infrastructure | 0 | 0 | 698 783 | 796 371 | 583 137 | 334 021 | 2 412 312 | 18.87 |

| Supply-side incentives | 0 | 0 | 103 551 | 171 450 | 516 356 | 479 811 | 1 271 168 | 9.94 |

| Capacity building—management | 0 | 0 | 63 714 | 160 482 | 338 841 | 407 933 | 970 969 | 7.59 |

| Transport/accommodation | 39 211 | 159 992 | 108 862 | 141 118 | 91 604 | 80 689 | 621 475 | 4.86 |

| Demand-side incentives | 0 | 0 | 42 701 | 128 158 | 246 210 | 159 750 | 576 819 | 4.51 |

| General management | 0 | 0 | 53 631 | 94 107 | 169 957 | 247 362 | 565 056 | 4.42 |

| Structural investment—equipment | 0 | 0 | 52 372 | 170 323 | 142 342 | 99 138 | 464 174 | 3.63 |

| Communications | 0 | 0 | 4700 | 17 793 | 190 318 | 223 728 | 436 540 | 3.41 |

| Supply-side verification | 0 | 0 | 20 628 | 123 715 | 82 167 | 159 347 | 385 857 | 3.02 |

| Office and equipment | 18 584 | 97 812 | 41 899 | 46 385 | 49 342 | 103 218 | 357 241 | 2.79 |

| Personnel (DP) | 61 264 | 60 603 | 59 850 | 59 048 | 58 190 | 57 300 | 356 254 | 2.79 |

| Capacity building—supportive supervision | 0 | 0 | 69 140 | 73 004 | 43 223 | 69 258 | 254 625 | 1.99 |

| Internal data audit | 0 | 0 | 722 | 0 | 204 391 | 11 417 | 216 531 | 1.69 |

| Initial feasibility study | 203 143 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 203 143 | 1.59 |

| Operations/administration | 0 | 0 | 118 479 | 0 | 12 385 | 0 | 130 864 | 1.02 |

| Governance | 0 | 0 | 1741 | 1651 | 10 577 | 92 029 | 105 998 | 0.83 |

| Baseline assessment | 0 | 0 | 72 622 | 16 399 | 17 480 | 0 | 106 502 | 0.83 |

| Fraud mitigation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 831 | 43 070 | 13 757 | 93 658 | 0.73 |

| General management (DP) | 17 730 | 12 695 | 12 537 | 12 021 | 11 847 | 12 566 | 79 395 | 0.62 |

| Consultancy (supportive) | 15 024 | 14 862 | 14 677 | 12 164 | 11 987 | 17 804 | 86 518 | 0.68 |

| Investment—human resources | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 39 037 | 22 323 | 61 360 | 0.48 |

| Capacity building—data collection and analysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1737 | 17 342 | 36 806 | 55 885 | 0.44 |

| Operations research | 0 | 0 | 2586 | 0 | 0 | 31 500 | 34 086 | 0.27 |

| Quality assurance | 0 | 0 | 13 105 | 13 144 | −47 | 0 | 26 201 | 0.20 |

| Capacity building—financial management | 0 | 0 | 1080 | 0 | 8066 | 5001 | 14 147 | 0.11 |

| Personnel (MoH) | 1239 | 767 | 641 | 599 | 575 | 448 | 4268 | 0.03 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3760 | 3760 | 0.03 |

| Management (MoH) | 186 | 115 | 96 | 90 | 86 | 67 | 640 | 0.01 |

MoH, Ministry of Health; RBF4MNH, Results Based Financing for Maternal and Newborn Health.

Discussion

This study makes an important contribution to the literature, being the first to describe in detail start-up and implementation costs of an RBF intervention, including both a demand-side and a supply-side component. Not only have prior analyses of similar programmes focused almost exclusively on costs related to supply-side incentive systems, but they were also rather limited and not comprehensive of all cost items, thus not fully reflecting the opportunity costs of implementing RBF programmes. The available studies have been conducted primarily with the objective of assessing cost-effectiveness of such programmes in relation to status quo service provision thus focusing more on the estimation of consequences, related to process or health outcomes, and costs related to provision of health services in the presence or absence of RBF.7–9 With our analysis, we aimed to trace all costs associated with designing and implementing an RBF intervention, beyond the focus on service provision. This is valuable not only to inform full economic evaluations, that is, cost-effectiveness analyses but also for informing policy decisions on further implementation of RBF programmes by describing the cost of single activities and the comparative weight of the single cost categories in detail. As such, our work complements existing literature on the economic evaluation of RBF interventions.

The first important finding emerging from our study is the substantial cost of the intervention, estimated at a total of €12 786 924, distributed across the 6 years of the evaluation period, including two start-up and four implementation years. It should be noted, however, that unlike other RBF programmes, this value includes a sizeable investment in infrastructure up-grading and provision of equipment to all participating public health facilities. The fact that implementation costs (across all activities) increased between 2013 and 2015 is likely to be a reflection of the fact that the RBF4MNH Initiative grew in size from 18 facilities in 2013, to 28 in 2014 and to 33 in 2015. The decrease in implementation costs observed in 2016 is a potential indication that programme management became more efficient as the intervention settled. This would not be surprising, given that the intensive efforts to enable RBF to function as expected, characterised the early implementation years. However, longer-term data would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

When considering the total number of women reached by the programme, the cost of the RBF4MNH Initiative is equivalent to €24.17 per potential beneficiary and €62.52 per actual beneficiary. We ought to specify that, when looking at cost per potential beneficiary, we did not account only for women who delivered in a healthcare facility, but for all women who were expected to experience a birth during a given year. We adopted this approach since the RBF4MNH Initiative aimed at reaching all women and encourage each one of them to deliver in a safe environment, hence all expecting months are potential beneficiaries. Our estimates stand out as being somewhat higher than estimates produced by prior economic analyses of RBF programmes, including the prior cost-effectiveness analysis of the RBF4MNH Initiative, which detected lower unit costs for delivery services.7 This discrepancy may seem particularly surprising considering that our analysis did not include the cost of providing care so we would have expected our estimates to be lower than previous estimates. However, it may also indicate that our work captured costs associated with RBF implementation, such as those related to design and human resource inputs by development partners, which can easily go unnoticed in studies focused on the cost-effectiveness of providing care under PBF. While this emerging hypothesis deserves further empirical verification, it would be aligned with the arguments postulated by Chi et al6 in calling for the application of more rigorous cost tracing to determine the actual economic value of RBF.

The second finding of interest is the fact that domestic resources only accounted only for a very limited portion of the total costs of the intervention, while development and implementing partners contributed most resources. In line with literature on RBF programmes21 22 as well as other complex health interventions,23 24 this high reliance on donor funding has turned out to be a key challenge for the sustainability of the RBF4MNH Initiative. In spite of the positive effects reported by both the scientific literature15–19 and by the implementation team,25 the Initiative was discontinued in 2018, once the relevant development cooperation agreement reached the end of its current funding cycle. Although the RBF4MNH Initiative was well-integrated within MoH structures and systems, the combination of human resource capacity constraints and very low operating budgets at the RHD of the MoH, meant that only a very small portion of the human resources deployed towards managing the Initiative were contributed by staff already stationed at the RHD. Such reliance on external funding has been recognised before as a key challenge to the sustainability of RBF interventions.22 26–29

Looking at findings in relation to the different activities which made up the RBF4MNH Initiative, we bring the reader’s attention again to the fact that the supply side activity cluster absorbed over 40% of all resources devoted to the project, although the incentives only represented approximately 10% of the total value of this activity while the infrastructural investment represented nearly half of its value. The high proportion of costs absorbed by the supply side activity likely reflects the strong focus on improving the quality rather than the quantity of care at participating facilities. The fact that the value of the incentives relative to the total value of the supply side activity cluster increased substantially over time suggests that as facilities become confident with working within the framework of an RBF intervention, their payoff increases, while the overall investments needed to operate the system (such as those in capacity building) decrease. While this pattern has been reported before in the literature,30 data from further implementation years would have been needed to confirm a trend towards increasing investments in incentives and decreasing investments in capacity building over time.

Nonetheless, the cost of the incentives compared with the overall cost of the intervention captured by our analysis is substantially lower than that observed in previous studies focused on supply-side RBF programmes. In Zambia, for instance, incentives accounted for nearly half of all costs of the PBF programme.8 In a separate PBF programme funded by United States Agency for International Development in Malawi, the SSDI-PBI programme, incentives took up nearly one-third of the overall cost of the intervention.30 In Afghanistan, incentives were observed to absorb two-thirds of all economic costs.9 Two factors may explain the differences observed between our findings and prior evidence. First, as discussed earlier, discrepancies may emerge as a consequence of different methodological approaches, specifically our focus on tracing and costing each and every activity making up the RBF programme rather than solely estimating the costs of providing services under RBF. Second, the RBF4MNH Initiative included substantial capital investment in infrastructure and purchase of large amounts of equipment for participating health facilities which the other programmes it has been compared with may have not.

The demand side activity cluster absorbed nearly 14% of the intervention value, with incentives in this case representing nearly one-third of all activity-specific costs. The fact that the value of the demand-side incentives decreased in 2016 compared with 2015 is attributable to the fact that the programme switched from offering CCT to all women delivering in an intervention facility to offering cash transfers only to the women most in need. This measure was introduced at the request of the MoH in order to align better with the government’s targeted social cash transfer programme. Analyses conducted after the end of the official impact evaluation indicated that this shift did not affect utilisation of delivery services, which remained high even once the universal cash transfers were discontinued.

Somewhat surprisingly, verification costs, referring exclusively to supply-side verification, only absorbed 6% of the overall value of the intervention. This value appears low considering that prior research has found verification costs to account for as much as 23% of overall costs of supply-side RBF programmes9 and that the costs associated with verification are often raised as an intrinsic challenge to the effective implementation of PBF programmes.30–33 The low verification cost observed in our study may be an indication that the verification processes within the framework of the RBF4MNH Initiative were managed efficiently. This was probably largely due to the fact that during the early stages of the intervention, the central management staff largely undertook the verification function (due to challenges in identifying and contracting a suitable verification strategy) while later the contract was awarded to a local agency, avoiding the high costs charged by international agencies in other settings.

Of additional interest is the fact that over the entire 6-year period, design activities absorbed less than 5% of the total value of the initiative, with the cost being driven largely by the initial feasibility study (we had no beak down of the feasibility study in specific cost categories) and by personnel costs. Comparatively, design activities absorbed one-third of the total costs of the parallel RBF intervention being rolled out in Malawi.30 The fact that costs were incurred over time for design activities is indicative of the adaptive and dynamic nature of the intervention, which as observed in the impact evaluation final report, represents one of its key success features. Still, the reduction in design costs observed overtime suggests that by 2015, the Initiative had reached its full form and did not necessitate substantial further adjustments. This element ought to be considered in light of a possible scale up, since design decisions may need to be made to expand geographical scope, but assuming that the experience of the four pilot districts is representative of the country, the intervention may not necessitate extensive re-shaping, hence design costs could be kept to a minimum.

Methodological considerations

Beyond its value as the first cost analysis carefully tracing all activities of a complex RBF intervention including both a supply-side and a demand-side component, we ought to recognise some important methodological limitations to our study. First, the retrospective nature of data collection made it impossible for us to trace resource consumption across activities as accurately as we would have wished to. Nonetheless, we engaged closely with the implementation team to reconstruct to the extent possible the roll-out of the intervention, complementing information from documents and financial data with information emerging from key informant interviews. This process was facilitated by the close relationship between the implementation and the research team, having worked together on the impact evaluation already. Second, given the paucity of similar studies focused specifically on the costs of RBF interventions, we recognise an inability to appraise our findings more comprehensively in relation to the experience of other settings. Third, since our study adopted a health system perspective, the resulting findings represent an underestimation of the total costs of the intervention, neglecting what costs might have been incurred at community level to enable its functioning (eg, community leaders mobilisation, identification of poor women, etc). Fourth, we need to acknowledge that the computation of the cost per potential beneficiary is based on the estimated number of deliveries in the district. Hence, any imperfection in this population-based estimate is also reflected in our own cost estimate. Finally, we need to acknowledge that due to the timing of our data collection, we could not include costs related to 2017 and 2018. Our research funding was aligned with the original funding of the intervention and we had no means to continue data collection once the intervention was unexpectedly extended with additional funding.

Conclusions

Our study represents the first comprehensive effort to assess the costs of setting up an RBF intervention, including both a demand and a supply-side component, examining all activity clusters and cost categories in detail. We have purposely not related these efforts to the benefits generated by the intervention, because, as documented by the literature, those have been very diverse and not easily reducible to a single matrix. Carefully tracing resource consumption across both start-up and design phases, our work suggests that the costs of bringing such an intervention into reality may be higher than what has been indicated by prior cost-effectiveness analyses. This observation calls for further research in the field, monitoring start-up and implementation costs of RBF programmes as well as those of comparable health financing interventions, aimed at reforming purchasing structures. Furthermore, this observation inevitably draws attention to the sustainability of such programmes, when one considers that even excluding the costs of service delivery, for every woman served, the RBF4MNH Initiative absorbed more than half the annual per capita health budget available at country level. Finally, we note that to overcome the challenges we have faced due to the retrospective nature of our work, we would argue in favour of integrating such research efforts in the infrastructure of the intervention evaluation from its very onset.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This would have not been possible had the staff at the Ministry of Health Malawi, the RBF4MNH implementation unit, the consulting agency Options, and both German and Norwegian cooperation agencies not supported us, sharing all documentation with us and answering our frequent questions. The authors are indebted to Jobiba Chinkhumba for his support with logistics and with data collection during the early phases of the project and to Bjarne Robberstad for his valuable comments on our study design and analytical approach.

Footnotes

Contributors: MDA and AT were responsible for the initial study design, data collection strategy and analytical approach. AT, MDA and EO shared the responsibility for data acquisition, including both the retrieval of information from existing documents and the interviews with key informants. AT and MDA were in charge of analysis, with contributions by CG and EO. MDA drafted the manuscript, with support from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MDA acts as guarantor for this manuscript.

Funding: This research was made possible by funding from the Ministry of Health Malawi and the KfW, the German Development Bank.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Corinne Grainger and Elena Okada worked for the agency that supported the implementation of the RBF4MNH Initiative, Options Consultancy Services (Options) during the data collection phase of the study. Subsequent contributions to this work have been purely voluntary and as such, the views expressed in this paper represent her own views and not those of Options.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The original data used for this study are not publicly available and would need to be obtained by the Ministry of Health Malawi and its development partners.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Both the Ethics Committee at the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University and the Ethics Committee in Malawi waived ethical approval since the study was based exclusively on secondary costing data.

References

- 1.Gautier L, De Allegri M, Ridde V. How is the discourse of performance-based financing shaped at the global level? A poststructural analysis. Global Health 2019;15:6. 10.1186/s12992-018-0443-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carrin G, Doetinchem O, Xu K. Conditional cash transfers: what’s in it for health? Technical Brief for Policy-Makers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritsche GB, Soeters R, Meessen B. Performance-Based financing toolkit. World Bank Publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oxman AD, Fretheim A. NIPH Systematic Reviews. In: An overview of research on the effects of Results-Based financing. Oslo, Norway: Knowledge Centre for the Health Services at The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH), 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowser D, Gupta J, Nandakumar A. The effect of demand- and supply-side health financing on infant, child, and maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries. Health Syst Reform 2016;2:147–59. 10.1080/23288604.2016.1166306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chi Y-L, Gad M, Bauhoff S, et al. Mind the costs, too: towards better cost-effectiveness analyses of PBF programmes. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000994. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinkhumba J, De Allegri M, Brenner S, et al. The cost-effectiveness of using results-based financing to reduce maternal and perinatal mortality in Malawi. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002260. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng W, Shepard DS, Nguyen H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of results-based financing, Zambia: a cluster randomized trial. Bull World Health Organ 2018;96:760–71. 10.2471/BLT.17.207100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salehi AS, Borghi J, Blanchet K, et al. The cost-effectiveness of using performance-based financing to deliver the basic package of health services in Afghanistan. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002381. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO . Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and the United nations population division. 104. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evelyn Z, Mary VK, Fannie K, et al . Newborn survival in Malawi: a decade of change and future implications for the Malawi Newborn Change and Future Analysis Group Author Notes Health Policy and Planning 2010;27:88–103. 10.1093/heapol/czs043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Statistical Office Malawi; DHS Program . Malawi demographic and health survey 2015-16 key indicators report, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller DH, Lungu D, Acharya A, et al. Constraints to implementing the essential health package in Malawi. PLoS One 2011;6:e20741. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organization WH . Global health expenditure database, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lohmann J, Muula AS, Houlfort N, et al. How does performance-based financing affect health workers' intrinsic motivation? A Self-Determination Theory-based mixed-methods study in Malawi. Soc Sci Med 2018;208:1–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner S, Mazalale J, Wilhelm D, et al. Impact of results-based financing on effective obstetric care coverage: evidence from a quasi-experimental study in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:791. 10.1186/s12913-018-3589-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kambala C, Lohmann J, Mazalale J, et al. How do Malawian women rate the quality of maternal and newborn care? experiences and perceptions of women in the central and southern regions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:169. 10.1186/s12884-015-0560-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brenner S, Wilhelm D, Lohmann J, et al. Implementation research to improve quality of maternal and newborn health care, Malawi. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:491–502. 10.2471/BLT.16.178202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Allegri M, Chase RP, Lohmann J, et al. Effect of results-based financing on facility-based maternal mortality at birth: an interrupted time-series analysis with independent controls in Malawi. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001184. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drummond MF, Drummond MFM, Sculpher MJ. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Witter S, Bolton L. Towards sustainability of RBF in the health sector – learning from experience in high and middle income countries. In: TASRI report for the world bank, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seppey M, Ridde V, Touré L, et al. Donor-funded project's sustainability assessment: a qualitative case study of a results-based financing pilot in Koulikoro region, Mali. Global Health 2017;13:86. 10.1186/s12992-017-0307-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muluh GN, Kimengsi JN, Azibo NK. Challenges and prospects of sustaining Donor-Funded projects in rural Cameroon. Sustainability 2019;11:6990. 10.3390/su11246990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossert TJ. Can they get along without us? sustainability of donor-supported health projects in central America and Africa. Soc Sci Med 1990;30:1015–23. 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90148-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Development FM for EC . How rewards improve health practice in Malawi, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertone MP, Wurie H, Samai M, et al. The bumpy trajectory of performance-based financing for healthcare in Sierra Leone: agency, structure and frames shaping the policy process. Global Health 2018;14:99. 10.1186/s12992-018-0417-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ridde V, Yaogo M, Zongo S, et al. Twelve months of implementation of health care performance-based financing in Burkina Faso: a qualitative multiple case study. Int J Health Plann Manage 2018;33:e153–67. 10.1002/hpm.2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertone MP, Falisse J-B, Russo G, et al. Context matters (but how and why?) a hypothesis-led literature review of performance based financing in fragile and conflict-affected health systems. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195301. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMahon SA, Muula AS, De Allegri M. "I wanted a skeleton … they brought a prince": A qualitative investigation of factors mediating the implementation of a Performance Based Incentive program in Malawi. SSM Popul Health 2018;5:64–72. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Allegri M, Makwero C, Torbica A. At what cost is performance-based financing implemented? novel evidence from Malawi. Health Policy Plan 2019;34:282–8. 10.1093/heapol/czz030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gergen J, Josephson E, Vernon C, et al. Measuring and paying for quality of care in performance-based financing: experience from seven low and middle-income countries (Democratic Republic of Congo, Kyrgyzstan, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Zambia). J Glob Health 2018;8:21003. 10.7189/jogh.08.021003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antony M, Bertone MP, Barthes O. Exploring implementation practices in results-based financing: the case of the verification in Benin. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:204.. 10.1186/s12913-017-2148-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grover D, Bauhoff S, Friedman J. Using supervised learning to select audit targets in performance-based financing in health: an example from Zambia. PLoS One 2019;14:e0211262. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050885supp001.pdf (144.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The original data used for this study are not publicly available and would need to be obtained by the Ministry of Health Malawi and its development partners.