Abstract

Background:

In patients with kidney failure, living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the best treatment option; yet, LDKT rates have stagnated in Canada and vary widely across provinces. We aimed to identify barriers and facilitators to LDKT in a high-performing health system.

Methods:

This study was conducted using a qualitative exploratory case study of British Columbia. Data collection, conducted between October 2020 and January 2021, entailed document review and semistructured interviews with key stakeholders, including provincial leadership, care teams and patients. We recruited participants via purposive sampling and snowballing technique. We generated themes using thematic analysis.

Results:

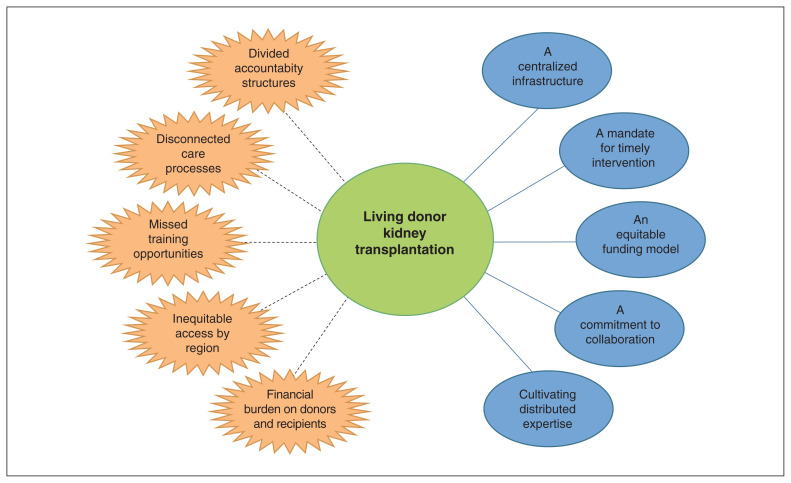

After analysis of interviews conducted with 22 participants (5 representatives from provincial organizations, 7 health care providers at transplant centres, 8 health care providers from regional units and 2 patients) and document review, we identified the following 5 themes as facilitators to LDKT: a centralized infrastructure, a mandate for timely intervention, an equitable funding model, a commitment to collaboration and cultivating distributed expertise. The relationship between 2 provincial organizations (BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency) was identified as key to enabling the mandate and processes for LDKT. Five barriers were identified that arose from silos between provincial organizations and manifested as inconsistencies in coordinating LDKT along the spectrum of care. These were divided accountability structures, disconnected care processes, missed training opportunities, inequitable access by region and financial burden for donors and recipients.

Interpretation:

We found strong links between provincial infrastructure and the processes that facilitate or impede timely intervention and referral of patients for LDKT. Our findings have implications for policy-makers and provide opportunities for cross-jurisdictional comparative analyses.

Patients with kidney failure have substantially higher morbidity and mortality than the general population and need high-cost treatments.1–6 Patients currently on dialysis have extremely poor survival when compared with the general population (unadjusted survival rate at 5 yr is < 45% and 10 yr is < 15%).4 In these patients, living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the best therapeutic option, especially when done pre-emptively (i.e., before requirement for renal replacement therapy).3,7–13 Living donor kidney transplantation can provide early access to a transplant; the graft has a superior survival when compared with a graft from a deceased donor; and patients live longer and report a better quality of life.1,2,4,14

Despite these well-known advantages to LDKT, the living donor rate in Canada has stayed the same since 2010 (about 15 donors per 1 000 000 population) and varies substantially across provinces (ranging from 6 to 23 donors per 1 000 000 population).3,4,15,16 British Columbia is recognized to be a high-performing health system in this regard as their living donor rate has been consistently 20 donors or more per 1 000 000 population.4,16,17 In addition, 50%–60% of all kidney transplantations performed annually in the province are from living donors. This is much higher than in Quebec or Ontario, for example, where this fraction is less than 15% and 30%–40%, respectively.4 Even when analyzing national initiatives such as the Kidney Paired Donation Program managed by Canadian Blood Services, BC is a leader in contributing to this effort. British Columbia has the highest number of registered recipients per 1 000 000 population, total transplantations performed via the registry, total transplants to registered recipients and altruistic donors who come forward to participate in this program.18

We previously conducted an interpretive descriptive study to understand the perspectives of health care providers in BC, Ontario and Quebec.19 Our work suggested that there are provincial differences in health system processes and attributes. We noted that the provision of transplantation is at the provincial level, and there is a lack of national legislation and policy frameworks to guide provincial programs.3,20 Thus, we aimed to conduct an exploratory case study of a high-performing health system, and to learn barriers and facilitators to LDKT.

Methods

Study design

We used a qualitative case study approach, which triangulated interview and document data, to conduct this study. Case studies are useful when studying complex phenomena within their environmental context,21 and are the preferred methodology for evaluating health systems that perform at one quality extreme or the other.22 Our exploratory approach was designed to produce inductively derived themes and explanations,23,24 about how structural arrangements and patterns of behaviour are linked with the provision of LDKT in BC and, by extension, Yukon, because BC also provides transplant services to this territory.

Our team included clinicians and qualitative experts (M.-C.F., M.C., S.S.) and social science researchers (A.H., P.N.). A patient partner was recruited with the help of the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program and assisted with refinement of the interview guides. Our collaborator from BC (D.L., a physician active in pretransplant, posttransplant and in-hospital transplant care) assisted with gathering documents for review and identifying and recruiting participants. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guideline and checklist to ensure rigour in our study.25

Setting and case selection

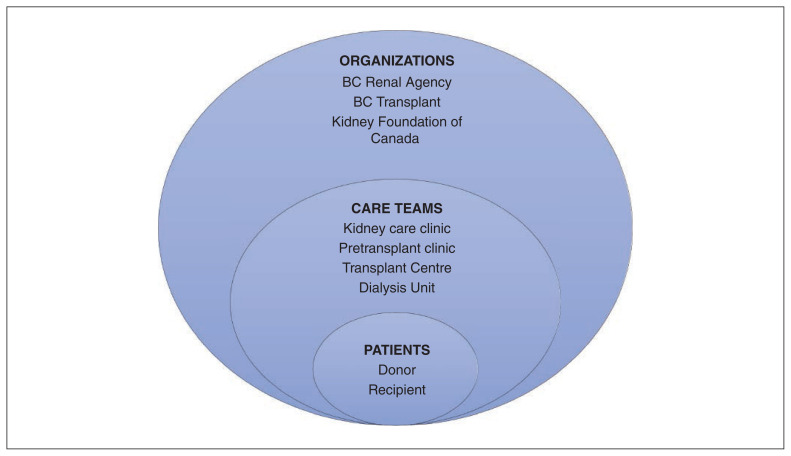

We chose BC as the setting for this case study because it is recognized as a high-performing system in the national context. 3,4,15 The “case” comprised the people and organizations that are involved with enabling LDKT in BC. Following a complex adaptive systems approach to health systems as multilevel and interconnected networks,26 we mapped out the organization spectrum for LDKT (Figure 1). The 2 main organizations involved in facilitating LDKT are BC Renal Agency (provides all kidney care services) and BC Transplant (oversees all aspects of organ donation and transplant).27 The Kidney Foundation of Canada is a charity with provincial branches that provides funding for research and patient services. British Columbia has 2 adult transplant programs (located in Vancouver) and several Kidney Care Clinics across the province.

Figure 1:

The organization spectrum of living donor kidney transplantation in British Columbia (based on a complex adaptive systems approach to health systems as multilevel and interconnected networks).

Participants

We used purposive sampling and snowballing techniques to invite stakeholders (patients, health care providers and organizational representatives) for interviews.22,28 An initial list of eligible interview participants was formed by our research team. This list included representation along the organizational spectrum of LDKT in BC (Figure 1) and was based on our collective knowledge of the health care system and literature review. Our collaborator in BC (D.L.) helped to identify participants in each represented role, who were contacted by email with an invitation to participate in an interview. We used a snowball technique, in which interviewees were asked to identify other potential participants.

Data collection

Interviews

The purpose of the interviews was to understand the system for LDKT in BC and to glean stakeholder perspectives about organizational structures, processes and care. Two authors (A.H. and S.S.) drafted initial interview guides (example for health care providers in Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/2/E348/suppl/DC1) based on themes pertinent to our aim,19,28 the organizational spectrum of LDKT in BC, and policies and programs identified in the initial document review. We developed separate interview guides (Appendix 1) for each participant category. Participants were categorized by their role and their place on the organizational spectrum of LDKT in BC. Guides were then reviewed by our patient partner and research team and modified accordingly (A.H.).

Video interviews were conducted from October 2020 to January 2021 by 1 author (A.H.), who is experienced in conducting qualitative research and was previously unknown to interview participants. The interviews were semistructured, in that guides provided focused guidance for the discussion but allowed room for improvised follow-up questions based on the interviewees’ responses.28 We used an iterative approach in which issues and attitudes were discussed with subsequent participants to enable verification and refinement of themes. The interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed by A.H.

Document review

The purpose of document review was to understand the operational framework and resources for LDKT better and served as means of triangulation with interview data.29 Document collection was conducted between August 2020 and January 2021. Documents for review were identified in consultation with our collaborator in BC, during interviews and using Web searches. We included documents if they were a resource, guideline, policy, program outline, announcement or report pertaining to LDKT.

During preliminary phases of the study, we asked collaborators in BC to send documents pertaining to the facilitation of LDKT and used these to inform our organizational spectrum (A.H., S.S.) (Figure 1). We also collected documents from interviewees, such as guidelines and resources, that they identified as relevant to the provision of LDKT. We conducted Web searches to collect information pertaining to LDKT from provincial agency websites and information about the transplant programs from hospital websites (A.H., S.S.). Documents were read as they were gathered, with new themes or issues highlighted for discussion with subsequent interview participants (A.H.). They were clustered thematically (A.H.), and these categorizations were reviewed by 1 author (P.N.).

Data analysis

Interviews

We conducted interviews until data saturation was reached (i.e., until interviews no longer yielded new information). Interview data were coded inductively by A.H., using a thematic analysis approach.23 NVivo version 1.5.1 (QSR International) software was used to manage the data. Interview data were organized into codes that were identified iteratively from the data set. Codes were then compared across the data set for regularities and divergences and modified accordingly. Through this process of inductive analysis, patterned responses developed into themes, which retained strong links with the original data set.30

Document analysis

We considered data saturation for document review to be when document collection from interviewees and collaborators and Web searches no longer yielded new information. Because the documents gathered were mostly unsuited to line-by-line coding, we read them closely and highlighted the relevant information, before they were clustered thematically following the principles of thematic analysis (A.H.).31

Data triangulation

The document and interview analyses were then compared for regularities and variations (A.H.). A subset of 7 interviews and the full data set of documents were independently reviewed by 1 author (P.N.) for coding and emergent themes to ensure consistency and reliability in the analysis. Two authors (A.H. and P.N.) then discussed the coding and reached consensus on final themes. Another author (S.S.) was consulted to resolve any disagreements.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the McGill University Health Centre Research Ethics Board.

Results

Of the 45 people we contacted for an interview by email, 22 agreed to participate (Table 1). Interviews were conducted via video call (in English) and lasted, on average, 52 minutes (range 32–77 min).

Table 1:

Participants who were interviewed for data collection within each category of the organization spectrum

| Participant category and role | No. of participants n = 22 |

|---|---|

| Provincial organization (n = 5) | |

| Representative from BC Transplant | 2 |

| Representative from BC Renal Agency | 2 |

| Representative from the Kidney Foundation of Canada | 1 |

| Transplant centre care team (n = 7) | |

| Nephrologist | 2 |

| Social worker | 2 |

| Nurse | 3 |

| Regional unit care team (n = 8) | |

| Pretransplant clinic nurse | 3 |

| Kidney Care Clinic nephrologist | 1 |

| Kidney Care Clinic nurse | 1 |

| Kidney Care Clinic social worker | 2 |

| Dialysis centre social worker | 1 |

| Patients (n = 2) | |

| Donor | 1 |

| Recipient | 1 |

We clustered the reviewed documents into 4 themes: infrastructure, health care provider resources, donor resources and recipient resources (Appendix 2, Supplementary Table 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/2/E348/suppl/DC1). Categorizing documents into these preliminary themes allowed us to contextualize the data from interviewees from across the organizational spectrum of LDKT.

After data triangulation with results of the interview and document analyses, we identified 10 final themes that we divided into 2 main categories (facilitators and barriers to LDKT in BC) with 5 themes in each category (Figure 2). Themes under each category are organized and presented separately for clarity but were largely interdependent. Selected quotes that illustrate each theme are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Figure 2:

Health-system barriers (orange) and facilitators (blue) to living donor kidney transplantation in a high-performing health system in British Columbia.

Table 2:

Participant quotes that illustrate each theme that was identified as a facilitator to living donor kidney transplantation in British Columbia

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| A centralized infrastructure | In BC, there is one provincial health authority, which funds BC Renal [Agency] and BC Transplant through MOH [Ministry of Health] dollars and has the mandate to enable provincial services. The centralization of funding and clarity of mandate; helps break down the silos to some extent. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) I think that’s a huge strength in BC, is the communication with the Kidney Care Clinics and the provincial renal agency as well as BC Transplant. We are lucky that it’s one big program here. And that the communication is the same and that we work and have the same messaging across centres and sites. (Transplant centre nurse 1) We have the provincial renal agency, which does a lot and they promote a lot. And we have our database and we have — they are always working on new teaching and patient materials and DVDs and stuff. (Kidney Care Clinic nurse) |

| A mandate for timely intervention | So generally speaking, the Kidney Care Clinics in our province try to refer people that are transplant suitable, are eligible, when their GFR [glomerular filtration rate] is around 20–25. So the thinking is that gives us enough time to be assessing them and helping them find a donor in time. (Transplant centre social worker 1) We’re seeing that recipients are being referred a little bit earlier for their transplant assessments, but conversations are also starting earlier about living donation. So, we will see and hear from living donors much earlier in the process so that they have time to work through it prior, ideally, before their recipient needing to start dialysis. So, we’re really trying to support pre-emptive living donor transplant where we can. (Transplant centre nurse 1) It was just going so perfectly down the road as things went along. And it was sort of nice maybe, not to be flooded with all the information, too. (Living donor recipient) |

| An equitable funding model | So, in BC, we use let’s call it an activity-based funding model, meaning you get a certain bundle of funding per patient-year of services. And what’s built into that is all the activities that are assumed to take place through the year. And so, yeah, [in 2015] that’s when they added a lift to specifically say that one of the items, once people got down to a certain GFR [glomerular filtration rate], is that they would be assessed for transplant. It’s relevant because even though it’s just a small amount for each patient, in aggregate, it can become a large amount. And that’s what, it actually let some places — like, for example, where I work in xxxx — it let us set up a dedicated, we have a couple of dedicated nurses, who specifically do this transplant work. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 2) It’s a lot easier to lobby a transplant organization to give you funding for transplant than it is to lobby a hospital, who has to support everything. (Representative from BC Transplant 1) |

| A commitment to collaboration | I think everybody in the renal world is pretty well-connected to ask questions or provide good care and figure out how we can make things work better. We are always kind of asking that question. (Kidney Care Clinic social worker) There’s a large working group that includes nurses, patients, doctors, transplanters and social workers. And they’ve come up with a work plan [for Transplant First] and they’ve come up with tools. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) That’s, I think, the key piece of it. Working together, working collaboratively, bringing in the regions, working with the Kidney Care Clinics. (Pretransplant clinic nurse 1) |

| Cultivating distributed expertise | So there is an initiative, a pretransplant initiative, training all our CKD [chronic kidney disease] nurses in terms of recognizing patients that would benefit from pre-emptive transplant and beginning the whole workup. So, the nephrologists are aware of this as well. But this comes from the ground up. So when I walk in to see a patient for clinic, my nurse might say, “hey, so-and-so has a donor. I was talking to her about transplant. Can we refer her?” So it’s not only got the nephrologists thinking about it, but we’ve also got our nurses prompting us. (Kidney Care Clinic nephrologist) Everyone’s open to talking about it – all of our team members are open to talking about transplant and feel, you know, some comfort level in doing that (Kidney Care Clinic social worker) |

Table 3:

Participant quotes that illustrate each theme that was identified as a barrier to living donor kidney transplantation in British Columbia

| Theme | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|

| Divided accountability structures | The other challenge, though, with doing that collaboration — you know, we would see it as being a spectrum of care. And as a clinician, I see kidney transplant as just being a spectrum of care for [a] kidney patient. Right? It’s part of their trajectory. But when [BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency] are different groups … there can be a predisposition to, kind of silo things. Which is trying to break apart, whose dollar is it that’s paid for which task, as opposed to just say, well, it’s a patient, it needs to get done and just get on with it. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) There are processes at BCT [BC Transplant] over which we at BC Renal [Agency] do not have authority. But some of the processes are a little bit inefficient, but part of that is because they don’t have the funding. But I can’t give them the funding because that’s not how it works. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) |

| Disconnected care processes | … a big challenge for us is — from the recipient side — is making sure that all the tasks that need to be done for them to get approved, worked up and approved, get done. It’s challenging just making sure that it’s clear who’s doing what, because the way it works here, a lot of it is done regionally and then they get referred to the transplant centre downtown. Sometimes there is a bit of confusion of who’s doing what and when things are being done. You’re sitting around waiting for tests and nobody knows if it’s done or not. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 2) Like, 3 years of me saying he’s failing and — anyways, that’s the problem, right? The system is clunky and doesn’t have a way to prioritize. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) [The pretransplant process] can be very disjointed and pieces go missing. (Dialysis centre social worker) I know that there is donor fatigue. There’s definitely donor fatigue there. (Transplant centre nurse) There is a lack of consistency between VGH [Vancouver General Hospital] and St. Paul’s, in terms of multiple areas actually, which is a problem. (Kidney Care Clinic nephrologist) |

| Missed training opportunities | I see other social workers that are new to the area who don’t understand because they just haven’t been through it, they haven’t learned about it. They don’t understand the transplant process and therefore they can’t support patients with that transplant process. (Dialysis centre social worker) I don’t really see a lot of trained transplant people. It’s basically on-the-job training — the people are here, let me show you what to do. (Pretransplant clinic nurse 2) I’m just frustrated that the people that are actually in the positions, aren’t trained in the positions. And the fact that administration seems to think that, well, everything works, so we’ll just continue on as it is. You know, we’ll bring one person in and we’ll train them and then we’ll bring another one and we’ll train them. And it doesn’t work. I mean, we can see it doesn’t work. (Pretransplant clinic nurse 2) |

| Inequitable access by region | The bad thing is if you live not within driving range of Vancouver, your incentive to get a living donor is potentially marred by the notion, a. you’ve got to be away from home for 3 months, b. your donor has to come from a way. (Representative from BC Renal Agency 1) [Kidney Care Clinics in Vancouver] have access to all that knowledge and education and processes, whereas in the regions it’s a bit different. We don’t have immediate access to that. (Pretransplant clinic nurse 1) |

| Financial burden on donors and recipients | I mean, I think everybody understands the financial benefits of living donor transplant. So, you know, this is a resource we are getting for free. So let’s put some money into it, for God’s sakes. It’s ridiculous. (Transplant nephrologist) But the hardest part for [my donor] was all of that time off and just the financial end of it, you know. Like she doesn’t have a husband, like I say, and 2 kids, and she has to pay rent and — or mortgage, I guess — and it was very hard on her. (Living donor recipient) My challenge is always that we don’t — the health care system and, you know, the clinicians, everybody who works to do transplant — we don’t want transplant or finances to be a barrier to transplant. But the reality is, is that it is. (Kidney Care Clinic social worker) |

Facilitators

A centralized infrastructure

A centralized infrastructure was deemed to be important for coordinating service delivery between regional clinics and transplant centres. The tight formal relationship between BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency enabled the efficient circulation of the mandate for LDKT as the first treatment choice for patients with kidney failure throughout the province. A joint ongoing initiative (Transplant First) helped to further the mandate for pre-emptive LDKT by standardizing early intervention and referral of patients from the Kidney Care Clinics.

BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency are united in joint efforts for accountability and performance monitoring. These include granulated indicators regarding transplant activity throughout the province. There are consistent efforts for performance improvement. Both share a centralized provincial database through which referrals for kidney transplantation are coordinated. Interview participants across the organizational spectrum of LDKT affirmed strong and supportive leadership from BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency as vital for consistent and efficient care.

A mandate for timely intervention

To advance pre-emptive LDKT across the province, BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency have mandated provision of information about LDKT to patients as the preferred treatment modality for kidney failure when estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is 25.90 mL/min/1.73 m2 or less. This intervention generally occurs in regional Kidney Care Clinics. The importance of early intervention was cited by stakeholders along the full organizational spectrum of LDKT.

Recent efforts to strengthen early intervention can be seen in the separation of a single education session for patients about modalities for treatment into multiple, separate sessions. This presents a way to make the information more digestible. Transplantation, with emphasis on LDKT, is the focus of the first session. These efforts also help to alleviate the risk of overwhelming patients with information about treatment options, which was cited as a concern by many stakeholders.

An equitable funding model

BC Transplant uses an activity-based funding model. This means that funding for transplant activity follows patients as they move through the system and enables the decentralization of transplant-specialized services. BC Transplant funds 8 specialized pretransplant clinics that are linked to Kidney Care Clinics around the province. Following each patient through the health care system, including in regional areas, incentivizes dedicated roles for transplant activity and coordination across various services. This also reduces competition for funds among services and assists in mandating early intervention for LDKT.

A commitment to collaboration

High value is placed on facilitating connectivity through collaborative associations in and among local health authorities and organizations. Furthermore, at a less formal level, working groups, committees and cross-provincial events in BC have created strong “communities of practice.” Such collaborative activities are multidisciplinary, include transplant and nontransplant health care providers and patient representatives, and span health authorities across the province. This has supported the consistent implementation of the mandate for LDKT and system-wide sharing of lessons from local innovations. Collaborative networks were also credited for the development and circulation of educational resources about LDKT for health care providers, patients and donors that are used throughout the province.

Cultivating distributed expertise

Interview participants from all participant categories conveyed an awareness of and knowledge about LDKT. The Transplant First initiative delivered training about LDKT in Kidney Care Clinics throughout the province. This was credited by service providers at these clinics as developing expertise about LDKT in regional clinics and fostering a culture of awareness of the benefits of LDKT as the primary treatment modality for kidney failure. Service providers in Kidney Care Clinics felt equipped either to discuss LDKT with patients or to refer them to a colleague. Since 2018, BC Transplant has funded dedicated roles for pretransplant workup, either within Kidney Care Clinics or an adjoining pretransplant clinic. This was cited as helping to facilitate early intervention and smoother coordination between the clinics and transplant centres for LDKT. Efforts are also being made to cultivate champions for transplantation in Kidney Care Clinics.

Barriers

Divided accountability structures

Although the partnership between BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency was generally perceived to be strong, some divisions were cited in identifying which organization was responsible for what work, particularly during the recipient pretransplant workup. Some challenges to the consistent delivery of LDKT existed in having 2 provincial organizations trying to coordinate the “spectrum of care” for patients. Complications occasionally arose from having distinct financial pools and separate leadership. Some perceived barriers to care processes being fully patient centred arose from the distinct purposes and accountabilities of the 2 organizations.

Disconnected care processes

Although the relationship between regional clinics and transplant centres was largely reported as being positive, some silos existed, and the processes for facilitating LDKT were characterized by some as being inefficient. The separation of services sometimes manifested in poor communication between transplant centres and regional clinics. This was mostly discussed with regard to the recipient pretransplant workup; however, some health care providers also expressed concern that the testing process could be depleting for donors. Interview participants from regional clinics also reported inconsistent communication and guidelines between transplant centres, which could result in inconsistent care delivery. There were some calls for national guidelines for donor and recipient testing to be reviewed to ensure they are evidence based and to standardize the care process better.

Missed training opportunities

Training of health care providers was inconsistent and largely obtained in daily practice. Some participants were concerned that a lack of consistency in this training for LDKT undermined the quality of care. Similarly, variations in training were cited as a barrier to consistent realization of the mandate for pre-emptive LDKT across BC. The training and educational resources provided by BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency were highly rated, but many health care providers felt they would benefit from more formalized training. The need for more culturally sensitive educational resources for patients was also highlighted by many.

Inequitable access by region

Despite substantial efforts to standardize care across the province, inequitable access to LDKT between regions exists. Expertise and resources for transplantation are centralized in Vancouver, the site of the 2 transplant centres. The size of BC and Yukon and the remoteness of many communities create challenges in accessing the transplant centres for donors and recipients who live further away from Vancouver. Although some aid is available for travel and accommodation through the Kidney Foundation of Canada, many interview participants noted that this did not fully offset the geographical disadvantages.

Financial burden for donors and recipients

The financial burden on donors and recipients was cited as a substantial barrier to LDKT along the full organizational spectrum. Current reimbursement schemes do not adequately cover costs for either donors or recipients. Financial burden was cited as a barrier for potential recipients to consider LDKT, both in terms of their own expenses and for those of potential donors. Many interview participants called for more comprehensive efforts to neutralize costs for donors and provide better financial support for recipients.

Interpretation

We have identified elements within the organizational spectrum that facilitate LDKT and those that act as barriers. Our data analysis showed strong links between provincial infrastructure and the processes that facilitate LDKT. Specifically, the relationship between BC Transplant and BC Renal Agency was identified as key to enabling the mandate and processes for LDKT to be distributed consistently across the province, and for timely intervention and referral for LDKT. Barriers arose from silos between these organizations, which manifested as inconsistencies in coordinating LDKT along the spectrum of care. Our study derives detailed knowledge of how a Canadian health system governs LDKT.

Previous work on increasing LDKT has focused mainly on interventions that address only patient-level barriers.28,32 Previous surveys of health care providers have pointed to system-level variabilities and inefficiencies.19,33,34 Outside of Canada, others have analyzed system- and centre-level factors that contributed to inequities in access to LDKT.35–38 Our study has built on this body of work by analyzing and learning from a high-performing health system and has shed insight into its successful features (i.e., facilitators) and areas for growth and improvement (i.e., barriers). We have shown that BC is able to address barriers at all levels of a health system via a holistic organizational approach that may explain its consistent success with LDKT.

A high-performing health system recognizes the imperative of addressing interventions that target multiple levels to optimize the performance of the system.39 Despite the recognition of these issues for over a decade, little progress seems to have been made in addressing some of the pervasive issues in LDKT in most jurisdictions of Canada. Patients have identified several health-system level barriers to LDKT that still exist.7 Multilevel approaches that target intervention beyond the patient need to be considered when designing and applying interventions and assessment.40 It is argued that this can better address multiple determinants of health at the same time within complex systems.40,41 Our future work will focus on a similar analysis in lower-performing provinces to understand barriers and facilitators to LDKT in different health systems better.

Limitations

Given the need for participants to agree to participate in the study, we acknowledge the risk of selection bias. Missing from our sample were eligible LDKT donors or recipients who had not yet received transplantation. This group might have been able to provide greater insight into the barriers to LDKT. We did not perform member checking (i.e., respondent validation), although this has been criticized for jeopardizing the internal validity of the study given the risk of participants changing their perspective.42,43 Our document review was not exhaustive. Although we feel that the document review enabled us to fulfil our aim of better understanding the operational framework and resources for LDKT and served as a means of triangulation with interview data, more robust inclusion and exclusion criteria would have made for a more comprehensive approach. In addition, although subsets of the data and the data analysis were reviewed by a second author (P.N.), having 2 independent coders for the full data set would have strengthened the rigor in our analysis. Finally, our findings in BC may have limited applicability in other provinces; however, the present study provides a framework for future work.

Conclusion

We have identified elements within the organizational spectrum of a high-performing health system that facilitate LDKT and those that act as barriers. Our findings have implications for policy-makers and provide opportunities for cross-jurisdictional comparative analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank the 22 people who participated in our study, and our patient partner for reviewing the interview guide and helping with recruitment of patients for this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Shaifali Sandal has received an education grant from Amgen Canada outside the submitted work. Marcelo Cantarovich is the current president of the Transplantation Society. David Landsberg was the Medical Director of BC Transplant and chair of the Canadian Blood Services and Health Canada Living Donation Advisory Committees until January 2020. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Shaifali Sandal conceived the study. Shaifali Sandal and Anna Horton drafted the manuscript. Shaifali Sandal, Marie-Chantal Fortin and Anna Horton designed the study. Anna Horton conducted the data collection. David Landsberg, Marcelo Cantarovich and Shaifali Sandal helped with recruitment and data collection. Anna Horton and Peter Nugus verified the data and conducted the data analysis. Marie-Chantal Fortin verified the data analysis. Shaifali Sandal and Anna Horton drafted manuscript, which the other authors critically revised. All of the authors interpreted and analyzed the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by a Research Innovation Grant from the Canadian Donation and Transplant Research Program and the Gift of Life Institute Clinical Faculty Development Research Grant from the American Society of Transplantation. The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; and preparation, writing, review or approval of the manuscript.

Data sharing: Data-sharing requests for de-identified data reported in this article will be considered upon written request to the corresponding author for up to 36 months after publication of this work. Data will be available subject to a written proposal, approval by an independent review committee and a signed data-sharing agreement.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/2/E348/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2019 USRDS Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2019. [accessed 2020 Jan. 20]. Available https://www.usrds.org/annual-data-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manns BJ, Mendelssohn DC, Taub KJ. The economics of end-stage renal disease care in Canada: incentives and impact on delivery of care. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2007;7:149–69. doi: 10.1007/s10754-007-9022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organ donation and transplantation in Canada, System Progress Report 2006–2015. Ottawa: Canadian Blood Services; 2016. [accessed 2022 Feb. 22]. Available: https://profedu.blood.ca/sites/default/files/odt_report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organ replacement in Canada: CORR annual statistics, 2020. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2020. [accessed 2020 Apr. 19]. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/organ-replacement-in-canada-corr-annual-statistics-2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manns B, McKenzie SQ, Au F, et al. Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD) Network. The financial impact of advanced kidney disease on Canada Pension Plan and private disability insurance costs. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117703986. doi: 10.1177/2054358117703986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.High risk and high cost: focus on opportunities to reduce hospitalizations of dialysis patients in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Getchell LE, McKenzie SQ, Sontrop JM, et al. Increasing the rate of living donor kidney transplantation in Ontario: donor- and recipient-identified barriers and solutions. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117698666. doi: 10.1177/2054358117698666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan JC, Gordon EJ, Dew MA, et al. American Society of Transplantation. Living donor kidney transplantation: facilitating education about live kidney donation – recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1670–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, Morgievich M, Cohen DJ, et al. American Society of Transplantation. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving education outside of transplant centers about live donor transplantation – recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1659–69. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00950115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore DR, Serur D, Lapointe Rudow D, et al. American Society of Transplantation. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving efficiencies in live kidney donor evaluation – recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1678–86. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigue JR, Swanson Kazley A, Mandelbrot DA, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation: overcoming disparities in live kidney donation in the US — recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1687–95. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00700115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tushla L, Lapointe Rudow D, Milton J, et al. American Society of Transplantation. Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation — recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1696–702. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klarenbach S, Barnieh L, Gill J. Is living kidney donation the answer to the economic problem of end-stage renal disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terner M, Redding N, Wu J. Increasing rates of kidney failure care in Canada strains demand for kidney donors. Healthc Q. 2016;19:10–2. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2016.24864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arshad A, Anderson B, Sharif A. Comparison of organ donation and transplantation rates between opt-out and opt-in systems. Kidney Int. 2019;95:1453–60. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris S. Organ donation and transplantation in Canada: statistics, trends and international comparisons. Publication No 2020-28-E. Ottawa: Parliament of Canada; 2020. [accessed 2021 Jan. 20]. Available: https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en_CA/ResearchPublications/202028E? [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organ donation and transplant statistics. Vancouver: Transplant BC; [accessed 2021 Feb. 11]. Available: www.transplant.bc.ca/health-info/organ-donation-transplant-statistics#Yearly-summaries. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Interprovincial organ sharing national data report: kidney paired donation program: 2009–2018. Ottawa: Canadian Blood Services; 2018. [accessed 2021 Aug. 3]. Available: https://professionaleducation.blood.ca/sites/default/files/kpd-eng_2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandal S, Charlebois K, Fiore JF, Jr, et al. Health professional-identified barriers to living donor kidney transplantation: a qualitative study. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2019;6:2054358119828389. doi: 10.1177/2054358119828389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray J, Ricketts M. Transplantation: workshop report. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Infection and Immunity; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13:544–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker GS. High performing healthcare systems: delivering quality by design. Toronto: Longwoods Publishing Corporation; 2008. pp. 1–291. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London (UK): SAGE Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stebbins RA. Exploratory research in the social sciences. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandler J, Rycroft-Malone J, Hawkes C, et al. Application of simplified Complexity Theory concepts for healthcare social systems to explain the implementation of evidence into practice. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:461–80. doi: 10.1111/jan.12815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BC Transplant Partnership. Vancouver: BC Renal Agency; [accessed 2020 Feb. 11]. Available: www.bcrenal.ca/about/who-we-are/bc-transplant-partnership. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandal S, Dendukuri N, Wang S, et al. Efficacy of educational interventions in improving measures of living-donor kidney transplantation activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2019;103:2566–75. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. 2009;9:27–40. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritchie J, Spencer L. The qualitative researcher’s companion. London (UK): SAGE Publications Ltd; 2002. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research; pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnieh L, Collister D, Manns B, et al. A scoping review for strategies to increase living kidney donation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:1518–27. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01470217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham J, Cass A, Anderson K, et al. Australian nephrologists’ attitudes towards living kidney donation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1178–83. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beasley CL, Hull AR, Rosenthal JT. Living kidney donation: a survey of professional attitudes and practices. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30:549–57. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reese PP, Feldman HI, Bloom RD, et al. Assessment of variation in live donor kidney transplantation across transplant centers in the United States. Transplantation. 2011;91:1357–63. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821bf138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:244–51. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hall EC, James NT, Garonzik Wang JM, et al. Center-level factors and racial disparities in living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:849–57. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udayaraj U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Roderick P, et al. Social deprivation, ethnicity, and uptake of living kidney donor transplantation in the United Kingdom. Transplantation. 2012;93:610–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318245593f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, et al., editors. Building a better delivery system: a new engineering/health care partnership. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2005. The National Academies Collection reports funded by National Institutes of Health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agurs-Collins T, Persky S, Paskett ED, et al. Designing and assessing multilevel interventions to improve minority health and reduce health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(Suppl 1):S86–93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paskett E, Thompson B, Ammerman AS, et al. Multilevel interventions to address health disparities show promise in improving population health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1429–34. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldblatt H, Karnieli-Miller O, Neumann M. Sharing qualitative research findings with participants: study experiences of methodological and ethical dilemmas. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82:389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1993;16:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.