Abstract

Background

More information is needed about gender-affirming surgery (GAS) in the Philippines because of many self- or peer-prescribed gender-affirming procedures among transgender people.

Aim

To assess the desire of transgender adults for GAS, determined the prevalence, and evaluated factors associated with the desire.

Methods

We did a retrospective study of medical charts of 339 transgender men (TGM) and 186 transgender women (TGW) who attended clinical services at Victoria by LoveYourself, a transgender-led community-based clinic in Metro Manila, from March 2017 to December 2019. The medical charts were reviewed to ascertain data on gender dysphoria (GD), clinical and sociodemographic characteristics, health-seeking behaviors, and gender-affirmation-related practices, including the use of gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT). We also estimated the prevalence and explored factors associated with the desire for GAS using generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution, log link function, and a robust variance.

Main Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was the self-reported desire for GAS.

Results

Almost half were already on GAHT, of whom 93% were self-medicating. Our study's prevalence of GD is 95% and nearly 3 in 4 desire GAS. The prevalence of desiring GAS was related to the specific surgical procedure chosen. Transgender adults opting for breast surgery and genital surgeries have 8.06 [adjusted prevalence ratio, (aPR): 8.06; 95% Confidence Interval, (CI): 5.22–12.45; P value < .001] and 1.19 (aPR: 1.19; 95% CI: 1.11–1.28; P value < .001) times higher prevalence of GAS desire, respectively, compared with otherwise not opting for those procedures. Moreover, the prevalence of GAS desire was higher among patients with GD (aPR 1.09; 95% CI: 1.01–1.18; P value = .03) than individuals without GD.

Clinical Translation

Providers' awareness of patients’ desires, values, and health-seeking preferences could facilitate differentiated guidance on their gender affirmation.

Strengths and Limitations

This quantitative study is the first to explore gender-affirming practices among transgender adults in the Philippines and provide significant insights into their healthcare needs. Our study focused only on TGM and TGW and did not reflect the other issues of transgender people outside of Metro Manila, Philippines. Furthermore, our retrospective study design may have missed essential predictors or factors not captured in the medical charts; hence, our study could never dismiss confounding factor bias due to unmeasured or residual confounding factors.

Conclusions

There is a high prevalence of self- and peer-led attempts from TGM and TGW to facilitate the gender transition, with the desire for GAS being significantly associated with GD and by which specific surgical procedure is chosen.

Eustaquio PC, Castelo AV, Araña YS et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated With Gender-Affirming Surgery Among Transgender Women & Transgender Men in a Community-Based Clinic in Metro Manila, Philippines: A Retrospective Study. Sex Med 2022;10:100497.

Key Words: Community-Based, Gender-Affirming Services, Gender-Affirming Surgery, Gender Dysphoria, Philippines, Transgender Men (TGM), Transgender Women (TGW)

INTRODUCTION

The self-applied umbrella term “transgender” refers to individuals whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth.1 Transgender people, much like the broader population, generally share health concerns, but some may have unique healthcare needs depending on their transition goals. Distinctive health needs may span from non-surgical, such as gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), counseling and support, and sexual health, to surgical services, including gender-affirming surgeries (GAS).2 These needs mostly require a multidisciplinary approach, involving players from primary to tertiary levels of care and even outside the healthcare system, such as legal services.3

Gender Dysphoria (GD), which is common among transgender people, is a clinical manifestation of significant distress, discomfort, and/or depressive states, secondary to the incongruence of one's gender and their sex assigned at birth, markedly affecting one's well-being.4 However, it is essential to note that not all transgender or gender-diverse individuals experience gender dysphoria.1 Likewise, not all people with a GD diagnosis may decide to receive any form of treatment.1 Nevertheless, numerous studies have shown that receiving gender-affirming services is associated with alleviation of GD,5 enhancement of quality of life and well-being,6,7 and decreased incidence of self-harm.8 Decline in the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities among those who initiated GAHT were also suggested.6,9

Despite its known benefits, access to these services in the Philippines10 and elsewhere11,12 has been limited and hindered by barriers. In the Philippines, barriers include the previous direct and vicarious experiences of stigma and discrimination, services remaining within spaces intended for HIV and cisgender men who have sex with men, and the absence of local guidelines or programs.10 These are comparable with barriers identified globally, which also include high out-of-pocket expenses and lack of health insurance coverage.13, 14 As with other countries,15, 16, 17 there is minimal exposure of health professional students and trainees in the Philippines to sexual and gender minority health issues,10 possibly except for being taught as they are at higher risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STI). All these reinforce the culture of self- or peer-prescription and self-performing surgery,18, 19 and increase the risk of poor health outcomes (eg, possible hormone overdosing) among the local transgender community.10, 20

What is known about factors associated with the desire for surgery is scarce, especially in the Philippines. More information is crucial for healthcare providers and the transgender community as GAS is a growing practice.21 GAS, despite its known benefits, may lead to irreversible consequences, regret, and detransition.22 To address this knowledge gap, our study aimed to answer the following questions among transgender men (TGM) and transgender women (TGW) who accessed services at Victoria by LoveYourself (VLY) in Metro Manila, Philippines: (i) what was the prevalence of desire for GAS and (ii) what could be the factors associated with this desire?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and Design

We conducted a retrospective study of health-seeking TGM and TGW at VLY from March 2017 to December 2019. Using routinely collected clinic data, we reviewed all medical records to determine trends in their health-seeking behavior and issues relating to their gender-affirming care. All medical records of the patients were screened using our inclusion criteria, which include (i) 18–60 years old, and (ii) those who identify as transgender. We excluded those who identify as otherwise (ie, including but not limited to cisgender, questioning, or genderqueer/non-binary). Those medical records whose patients’ characteristics fit our criteria were included in data analysis. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from an independent research ethics committee and the implementation of the study followed the Philippines' Data Privacy Act of 2012. The STROBE statement checklist was used as a guide in the conduct of the study.23

Study Site

The study site, VLY, is the first transgender-led community-based clinic in the Philippines that provides gender-affirming services. The needs of the transgender community, mainly on access to comprehensive and quality transgender healthcare services, prompted the initiative to establish this specific clinic. It is an all-inclusive facility providing holistic care and approach which integrates existing HIV and STI services and gender-affirming services, including GAHT, counseling, and referral for GAS, psychosocial counseling and peer support services.

Data Collection

Outcome Data Assessment

Our primary outcome of interest was the desire to undergo gender-affirming surgery (yes or no), which includes vaginoplasty, phalloplasty, hysterectomy with or without oophorectomy, orchiectomy, breast augmentation, or chest reconstruction.24 The outcome was determined through self-reporting of the patients.

Assessment of Patient's Characteristics

Upon enrollment at VLY, patients underwent counseling on sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sexual characteristics. They self-reported their gender identity and were diagnosed by the clinician with gender dysphoria using the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5, the dimensional component of which was measured using the Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adults and Adolescents scale (GIDYQ-AA).25 Transition management plan was discussed and agreed upon between the patient and the provider from VLY. In addition, various characteristics of the patients were collected, including demographic, health-seeking behavior, and gender-affirmation services-related variables. For the demographic characteristics, the age in years and gender identity were collected. The year of the first consultation and frequency of visits of patients were determined for the health-seeking behavior characteristics. From the patient's medical records, the GAHT-provider at baseline (healthcare provider or self-medicating), the type of surgery chosen (breast, genital, and/or laryngeal), and the diagnosis of gender dysphoria (yes or no) were all ascertained for the gender-affirmation services-related characteristics.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the patients’ study characteristics, including mean and standard deviation for the age variable and frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables. Using complete case analyses, bivariable and multivariable regression models were developed to explore associations. Associations between each demographic, health-seeking behavior, and gender-affirmation services-related covariate and the desire for GAS were estimated using bivariable generalized linear models (GLMs) with a Poisson distribution, log link function, and a robust variance, which is a more suitable approach for analyzing common outcomes.26, 27, 28

Furthermore, we estimated the association between the desire for GAS and all the demographic, health-seeking behavior, and gender-affirmation services-related variables using a multivariable GLM with a Poisson distribution, log link function, and a robust variance.26, 27 In the multivariable model, we included age (15–24 years old, 25–34 years old, or > 34 years old); gender identity (transgender man or transgender women); clinic visit frequency (1 visit, 2–3 visits, or 4 visits and above); GAHT provider (healthcare provider or self-medicating); gender dysphoria (yes or no); GAHT status (naïve or current/former); year of initial consult (2017, 2018, or 2019); and chosen type of surgery for breast (yes or no), genital (yes or no) and laryngeal (yes or no). The model was fitted to account for the heterogeneity in the patient's overall desire for GAS.

Moreover, we reported effect size estimates as crude prevalence ratio (cPR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for bivariable models and adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) with 95% CI for the multivariable model. All management of data and analyses were conducted using STATA 17 software (www.stata.com).

RESULTS

Eligible patients included 525 individuals enrolled from 2017 to 2019, of whom 339 were TGM (64.6%), and 186 were TGW (35.4%). The patients were young adults with mean age (±SD) of 25.8 ± 5.8 years old at enrollment. There was an increasing number of individuals being enrolled each year, with a 2.5 and 4.6-fold increase in the number of clients registered in 2018 and 2019, respectively, compared with 2017. Almost half of the patients (48.2%, n = 253) were already on GAHT, 92.9% (n = 235) of whom were self-medicating. In terms of the type of surgery chosen by the patients, most opted for breast surgery (70.1%), whereas less opted for genital (25.7%) and laryngeal (1.1%) surgeries. The frequency of clinic visits was noted to be only once for half of the patients (54.8%), and only 16.7% showed up for four or more clinic visits. The prevalence of GD among TGW and TGM is noted at 95.1% and 73.7% of patients desired GAS (See Table 1 for details).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants (N = 525)

| Characteristics * | Total (N = 525) | Transgender Man (N = 339) | Transgender Woman (N = 186) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 25.8 (5.8) | 26.1 (5.7) | 25.4 (6.1) |

| Age category | |||

| 18 – 24 y old | 245 (46.7) | 153 (45.1) | 92 (49.5) |

| 25 – 34 y old | 242 (46.1) | 162 (47.8) | 80 (43.0) |

| 35 y old & above | 38 (7.2) | 24 (7.1) | 14 (7.5) |

| Gender identity | |||

| Transgender man | 339 (64.6%) | 339 (100.0) | - |

| Transgender woman | 186 (35.4%) | - | 186 (100.0) |

| Year of initial consult | |||

| 2017 | 52 (9.9%) | 13 (3.8) | 39 (21.0) |

| 2018 | 181 (34.5%) | 113 (33.3) | 68 (36.5) |

| 2019 | 292 (55.6%) | 213 (62.9) | 79 (42.5) |

| Total visits | |||

| 1 visit | 288 (54.9%) | 166 (49.0) | 122 (65.6) |

| 2 – 3 visits | 149 (28.4%) | 103 (30.4) | 35 (24.7) |

| 4 visits & above | 88 (16.7%) | 70 (20.6) | 18 (9.7) |

| Gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) status | |||

| Currently/Formerly on GAHT | 253 (48.2%) | 107 (31.6) | 146 (78.5) |

| Naïve | 269 (51.2%) | 229 (67.5) | 40 (21.5) |

| Missing data | 3 (0.6%) | 3 (0.9) | - |

| Preferred type of surgery | |||

| Breast | |||

| Yes | 368 (70.1%) | 258 (76.1) | 110 (59.2) |

| No | 156 (29.7%) | 81 (23.9) | 75 (40.3) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.5) |

| Genital | |||

| Yes | 135 (25.7%) | 71 (20.9) | 64 (34.4) |

| No | 389 (74.1%) | 268 (79.1) | 121 (65.1) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.5) |

| Laryngeal | |||

| Yes | 6 (1.1%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (1.6) |

| No | 518 (98.7%) | 336 (99.1) | 182 (97.9) |

| Missing data | 1 (0.2%) | - | 1 (0.5) |

| GAHT provider | |||

| Healthcare provider | 290 (55.2%) | 242 (71.4) | 48 (25.8) |

| Self-medicating | 235 (44.8%) | 97 (28.6) | 138 (74.2) |

| Gender dysphoria | |||

| Yes | 499 (95.1%) | 322 (95.0) | 177 (95.2) |

| No | 20 (3.8%) | 14 (4.1) | 6 (3.2) |

| Missing data | 6 (1.1%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (1.6) |

| Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) | |||

| Desired | 387 (73.7%) | 263 (77.6) | 124 (66.7) |

| Not desired | 138 (26.3%) | 76 (22.4) | 62 (33.3) |

Distributions of variables are reported as n (%) unless specified otherwise.

Table 2 shows the crude effect estimate of each demographic, health-seeking behavior, and gender-affirmation services-related factor on the desire for GAS. The following factors were associated with the desire for GAS: gender identity, GAHT status, GAHT provider, frequency of visit, and all types of surgeries. Moreover, the prevalence of the desire for GAS was 18% higher among patients who were unexposed to GAHT compared to patients who were formerly or currently on GAHT (cPR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.06–1.30; P value < .001). The extent of the desire for GAS has been found to be related to the type of surgery they chose, with the most robust effect estimate noted among those who opted for breast surgery (cPR = 8.67; 95% CI: 5.61–13.39; P value < .001) and strong effect estimates among those who opted for genital (cPR = 1.55; 95% CI: 1.44–1.67; P value < .001) and laryngeal surgeries (cPR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.29–1.44; P value < .001), than those who did not opt for the breast, genital and laryngeal surgical procedures, respectively.

Table 2.

Crude prevalence ratio (cPR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the associations between the desire for gender-affirming surgery (GAS) and covariates among TGM & TGW

| Characteristics * | Total | Not desired 138 (26.3%) | Desired 387 (73.7%) | cPR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age category | ||||

| 18 – 24 y old | 245 | 60 (43.5%) | 185 (47.8%) | 1.00 |

| 25 – 34 y old | 242 | 63 (45.6%) | 179 (46.3%) | 0.98 (0.88 – 1.09) |

| 35 y old & above | 38 | 15 (10.9%) | 23 (5.9%) | 0.80 (0.61 – 1.05) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Transgender men | 339 | 76 (55.1%) | 263 (68.0%) | 1.00 |

| Transgender women | 186 | 62 (44.9%) | 124 (32.0%) | 0.86 (0.76 – 0.97) ‡ |

| Year of initial consult | ||||

| 2017 | 52 | 19 (13.8%) | 33 (8.5%) | 1.00 |

| 2018 | 181 | 43 (31.1%) | 138 (35.7%) | 1.20 (0.96 – 1.50) |

| 2019 | 292 | 76 (55.1%) | 216 (55.8%) | 1.17 (0.94 – 1.45) |

| Total visits | ||||

| 1 visit | 288 | 83 (60.2%) | 205 (53.0%) | 1.00 |

| 2 – 3 visits | 149 | 30 (21.7%) | 119 (30.7%) | 1.12 (1.01 – 1.25) † |

| 4 visits & above | 88 | 25 (18.1%) | 63 (16.3%) | 1.01 (0.86 – 1.17) |

| GAHT status | ||||

| Currently/formerly on GAHT | 253 | 81 (60.0%) | 172 (44.4%) | 1.00 |

| Naïve | 269 | 54 (40.0%) | 215 (55.6%) | 1.18 (1.06 – 1.30) § |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Breast | ||||

| No | 156 | 138 (100%) | 18 (4.7%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 368 | 0 (0.0%) | 368 (95.3%) | 8.67 (5.61 – 13.39) § |

| Genital | ||||

| No | 389 | 138 (100%) | 251 (65.0%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 135 | 0 (0.0%) | 135 (35.0%) | 1.55 (1.44 – 1.67) § |

| Laryngeal | ||||

| No | 518 | 138 (100%) | 380 (98.4%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 6 | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (1.6%) | 1.36 (1.29 – 1.44) § |

| GAHT provider | ||||

| Healthcare provider | 290 | 63 (45.6%) | 227 (58.7%) | 1.00 |

| Self-medicating | 235 | 75 (54.4%) | 160 (41.3%) | 0.87 (0.78 – 0.97) ‡ |

| Gender dysphoria | ||||

| No | 20 | 6 (4.5%) | 14 (3.6%) | 1.00 |

| Yes | 499 | 127 (95.5%) | 372 (96.4%) | 1.07 (0.80 – 1.43) |

Distributions of variables are reported as n (%).

P ≤ .05

P ≤ .01

P ≤ .001.

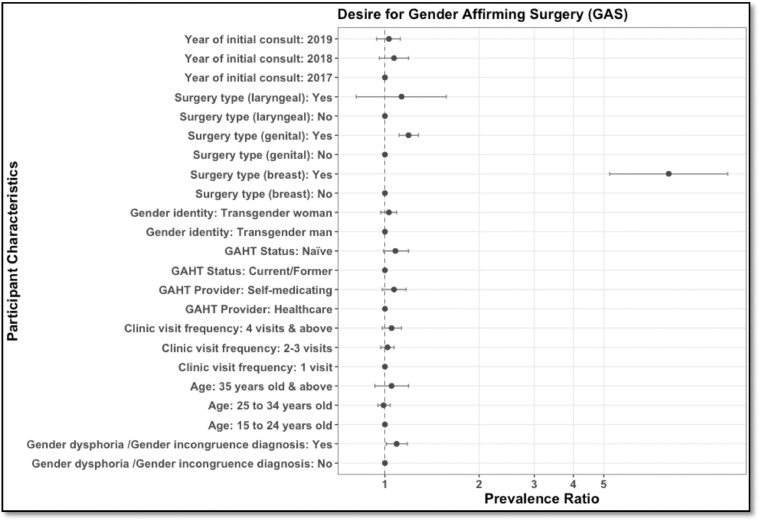

In our adjusted Poisson model (Figure 1), likewise, with our crude analysis, there is evidence that the desire for surgery is also related to which surgical procedure they opted to receive. Patients who opted for breast surgery were associated with 8 times higher desire for GAS (aPR: 8.06; 95% CI: 5.22–12.45; P value < .001) compared to patients who did not opt for breast surgery, whereas patients who opted for genital surgery were associated with 19% higher desire for GAS relative to patients who did not opt for genital surgery (aPR: 1.19; 95% CI:1.11–1.28; P value < .001). Additionally, prevalence of the desire for GAS was 9% higher among patients with GD (aPR 1.09; 95% CI: 1.01–1.18; P value = .03) compared to those who were not diagnosed with GD. In contrast, opting for laryngeal surgery, gender identity, GAHT status, and GAHT provider at baseline had null associations with the desire for GAS (See Supplemental Table 1 for details).

Figure 1.

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio for the effect of age, gender identity, surgery type, gender-affirming. hormone therapy (GAHT) status, GAHT provider, gender dysphoria/incongruence, and initial year and frequency of visits on the desire for gender-affirming surgery (GAS). Model included age (15–24 years old, 25–34 years old, > 34 years old); gender identity (transgender man, transgender women); clinic visit frequency (1 visit, 2–3 visits, 4 visits & above); GAHT provider (healthcare provider, self-medicating); gender dysphoria/incongruence (yes, no); GAHT status (naive, current/former); year of initial consult (2017, 2018, 2019); and preferred type of surgery for breast (yes/no), genital (yes/no) and laryngeal (yes/no). Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Our study describes the demographic and clinical characteristics and the prevalence of desire for GAS and the factors associated with this among TGW and TGM enrolled in a transgender-led community-based clinic in Metro Manila, Philippines. The prevalence of taking hormones for gender affirmation is 48.2% (78.5% of TGW, 31.9% of TGM), which is higher than the reported prevalence rates among referrals to specialty clinics in other countries,18, 29 and relatively similar with a cross-sectional study previously conducted in the Philippines30 and elsewhere.19, 31 Estimates of prevalence of self-prescription or self-medication are likewise high in other countries especially among TGW,18, 32 except for one study in Canada wherein the relatively low prevalence has been attributed to low reporting rates and sampling issues.19 As availing hormones requires a prescription in the Philippines, it is inevitable that high prevalence of self-medication among transgender adults puts them at risk of accessing their hormones from non-medical sources, similar to previous studies where around 7 in 10 TGW access from their peers and the internet.18, 32

Furthermore, in our study, patients demonstrated higher proportions of opting for breast surgery than genital or laryngeal surgeries. These findings are consistent with previous studies done locally,33 and elsewhere,34, 35 which reported that pursuing and opting for breast surgery was consistently more prevalent than genital or laryngeal surgeries. We hypothesize several reasons that may explain our findings. Firstly, breast surgeries are more readily accessible compared to genital surgeries in the Philippines and other countries. Mastectomy is highly available in most countries, considering that it is offered to patients with breast pathology20 regardless of sex assigned at birth and gender. Interestingly, even in Thailand, where genital surgery is highly accessible, only 11% of TGW from a sample of three cities have reported receiving genital surgery.32 Moreover, there are more trained practitioners on breast augmentation or mastectomy than vaginoplasty or phalloplasty.35 This limited number of genital surgery providers could be attributed to the non-inclusion of transgender health in the medical school curricula and the lack of standards of care for transgender people in the Philippines.10 In addition, costs were also determined as a barrier to genital surgery with transgender people in the country prioritizing breast surgery and laryngeal trimming, which are more affordable than genital procedures.33 Secondly, a previous study has suggested that breast surgery may be deemed more valuable for the external presentation of one's gender identity as it is seemingly more evident compared with genitalia.35 In a cohort study among transmasculine individuals, 94% of participants regarded breast surgery with high importance.36 These insights could imply that breast surgery plays a significant role in aligning one's gender expression with their internal sense of self and ultimately alleviating distress for people diagnosed with GD,37 similar to undergoing procedures that feminize or masculinize other external gendered features of oneself.20, 35 Lastly, these breast procedures were considered "life-saving" as this is complementary protection for transgender people against everyday discrimination and hate crimes.37

Interestingly, likewise with previous studies,38, 39 the preference of TGM for breast surgery (76.1% among TGM vs 59.2% among TGW) and of TGW for genital procedures (34.4% among TGW vs 20.9% among TGM) were noted in our cohort. Given the variety of pre-intervention breast size and variable decrease in size with GAHT among TGM, breast surgery remains as staple to alleviate their dysphoria; whereas, considerable breast augmentation among TGW may be achieved by GAHT alone.38, 40 It must be however noted, that, unlike our study, majority of the transgender adults involved in these prior studies were currently and previously on GAHT. This could have influenced their decision or desire for GAS as there might have been some breast changes already, especially among TGW.39 Moreover, in a previous study, transgender adults who received GAHT were found to have more manageable distress symptoms and decreased body dissatisfaction than those who have not yet undergone hormone therapy.41 In our study, more than half were GAHT-naïve, and not being on GAHT is associated with a higher prevalence rate of desiring surgery in the crude bivariable analysis. However, upon adjusting with other predictors, the association turned out to be non-significant. Nevertheless, it is essential to note that transition goals vary by person. While GAHT or GAS are effective interventions in improving well-being and may be medically necessary for others, some transgender adults, even those diagnosed with GD, may opt-out from receiving any treatment at all.1, 42

The analyses performed in our research revealed that having a GD diagnosis was associated with higher prevalence of desire for GAS. Our finding may be explained by the perception that GAS may decrease their GD and improve overall well-being, as seen in previous studies.7, 43 Conversely, the absence of GD has been associated with a lesser desire for GAS.44 Given its benefit for overall well-being of transgender individuals, GAS has been considered as treatment for GD by many different health agencies and organizations.42, 45, 46

This study is the first to provide information on the prevalence of GD and the prevalence of GAS desire and its predictors among transgender adults in the Philippines. Given the high utilization of gender-affirming services in VLY and the high prevalence of self-medication and peer-prescribing, there is a need to upscale peer-led community-based medical interventions to increase healthcare access among transgender adults, especially that this approach facilitates familiarity and decreases the perception of healthcare-related stigma.42, 47 Moreover, the growing evidence of increased uptake of HIV testing, prevention, and care services,48, 49 mental health services, counseling, and peer support in community-based settings,50 have reinforced the idea of a multi-service, one-stop-shop, all-inclusive approach as cost-effective mechanisms to facilitate healthcare access among transgender people.

Furthermore, this study provides evidence that the systematic collection of health information related to gender identity provides opportunity to explore health issues of gender minorities. We would argue that limiting healthcare strategic information to sex assigned at birth as demographic data misses essential health issues. This is significant amid the uniqueness of their needs and the systemic failure of healthcare to address these needs. In terms of statistical analysis, our sample size made it possible to generate regression models without overfitting, optimizing the exploration of the influence of the chosen a priori predictors. Moreover, the application of the Poisson model with robust variance made it possible to use prevalence ratio as the measure of association, which is easier to communicate as it is more intuitive to comprehend and interpret.26, 27, 28

Meanwhile, we do acknowledge a few limitations of our study. Firstly, given its secondary data analysis nature, we have determined that there are many missing data and inadequate, imprecise documentations in the charts that have precluded insightful analysis of other potential predictors (eg, sexual orientation and income) and even the outcomes, particularly in the nuances of genital surgery (eg, gonadectomy, genitoplasty, or both). Furthermore, more information on potential predictors could be collected, including experiences of healthcare-related discrimination. For this reason, our study could neither rule out confounding factor bias due to unmeasured or residual confounding factors nor provide deeper insights into their desire for genital surgery. Secondly, this study focused on TGM and TGW who can access care, although provided for free in VLY, in Metro Manila; hence, it does not reflect the complexity of issues of transgender people who cannot access care and those in locations outside Metro Manila. Hence, the generalization of our findings must be done carefully. Thirdly, unlike a previous study where 25% of the cohort was genderqueer and non-binary,24 we have opted to exclude those who do not identify as transgender as the numbers were very small (n = 5; 0.9% of the total cohort). This limited our capacity to explore the experience of other gender non-conforming groups. Moreover, it must be acknowledged that the GIDYQ-AA has been criticized for its polarized assumptions on gender identity,25 towards non-binary individuals, and as outdated in terms of the DSM-5 definition of gender dysphoria.51 Although DSM-5 could be used to diagnose GD, the choice for supplementary tool could be more updated and inclusive moving forward. Fourthly, as almost half were already self-medicating, the inability to document the current state of secondary sex characteristics prevented us from controlling for this variable if it has an underlying influence on GAS desire.

Future studies may benefit from having a more robust study methodology and standardized data collection mechanism. In addition, the experience of TGM and TGW regarding their medical needs goes beyond clinical factors and is heavily influenced by sociocultural constructs. Qualitative studies on the experience of transgender people with GAHT and GAS may help us contextualize the data further. Intersections of sexual orientation and gender identity are being explored in depth as they have implications for the transgender's health needs and vulnerabilities. Hence, further studies may benefit from further disaggregation of data in terms of sexual orientation and gender identity, whether or not the study is transgender-specific.

CONCLUSION

This study expands the understanding of the health-seeking behavior and transition goals of transgender adults. It also provides prevalence estimates of GD, GAHT, and desire for GAS among transgender adults in a community-based clinic in Metro Manila, Philippines. Our findings suggest that given the high prevalence of self- and peer-led efforts to facilitate gender transition, integration of medical practice and peer-led community-based interventions could be essential to increase access to healthcare services, to alleviate GD, and to improve the well-being of transgender adults. Moreover, the desire for GAS may be influenced by GD and by which specific surgical procedure is chosen, which may be further shaped by sociocultural factors. Therefore, exploring and effectively responding to the health needs of sexual and gender minorities requires systemic changes in medical education and practice.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), along with the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP), E6 (R2), and other ICH-GCP 6 (as amended); National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research (NEGHHRR) of 2017. This protocol has been approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB) (CODE: 2021-105-01).

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

All authors conceived and designed the research question and analysis and provided technical inputs in the draft. Patrick C. Eustaquio, Aisia V. Castelo, John Oliver L. Corciega, Yanyan S. Araña, John Danvic T. Rosadiño, and Ronivin G. Pagtakhan collected the data and contributed to the data analysis. Zypher Jude G. Regencia and Emmanuel S. Baja performed the data analysis. PCE and AVC wrote the paper while all the other authors helped in the revision. All named authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No competing financial interests exist.

Funding: This study was supported by The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria through the Sustainability of HIV Services for Key Populations in Asia (SKPA) Programme, under program grant agreement QMZ-H-AFAO, managed by the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, and implemented in the Philippines by LoveYourself Inc.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2022.100497.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychological Association Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am Psychol. 2015;70:832–864. doi: 10.1037/a0039906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. Lancet. 2016;388:412–436. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cicero EC, Reisner SL, Silva SG, et al. Health care experiences of transgender adults: An integrated mixed research literature review. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2019;42:123–138. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Fifth edition. 2013.

- 5.van de Grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, et al. Effects of medical interventions on gender dysphoria and body image: A follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:815–823. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1:21–31. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2015.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wernick JA, Busa S, Matouk K, et al. A systematic review of the psychological benefits of gender-affirming surgery. Urol Clin North Am. 2019;46:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson EC, Chen YH, Arayasirikul S, et al. Connecting the dots: Examining transgender women's utilization of transition-related medical care and associations with mental health, substance use, and HIV. J Urban Health. 2015;92:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9921-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heylens G, Verroken C, De Cock S, et al. Effects of different steps in gender reassignment therapy on psychopathology: A prospective study of persons with a gender identity disorder. J Sex Med. 2014;11:119–126. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization- Regional Office for the Western Pacific . WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila: 2013. Regional Assessment of HIV, STI and Other Health Needs of Transgender People in Asia and the Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong LSH, Kerklaan J, Clarke S, et al. Experiences and perspectives of transgender youths in accessing health care: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1159–1173. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teti M, Kerr S, Bauerband LA, et al. A qualitative scoping review of transgender and gender non-conforming people's physical healthcare experiences and needs. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.598455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacCarthy S, Reisner SL, Nunn A, et al. The time is now: attention increases to transgender health in the united states but scientific knowledge gaps remain. LGBT Health. 2015;2:287–291. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2014.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safer JD, Coleman E, Feldman J, et al. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23:168–171. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parameshwaran V, Cockbain BC, Hillyard M, et al. Is the lack of specific lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) health care education in medical school a cause for concern? evidence from a survey of knowledge and practice among UK medical students. J Homosex. 2017;64:367–381. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1190218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: Medical students' preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27:254–263. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur S, Jamieson A, Cross H, et al. Medical students' awareness of health issues, attitudes, and confidence about caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender patients: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:56. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mepham N, Bouman WP, Arcelus J, et al. People with gender dysphoria who self-prescribe cross-sex hormones: Prevalence, sources, and side effects knowledge. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2995–3001. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, et al. Nonprescribed hormone use and self-performed surgeries: "do-it-yourself" transitions in transgender communities in Ontario, Canada. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asia Pacific Transgender Network. Blueprint for the Provision of Comprehensive Care for Trans People and Trans Communities in Asia and the Pacific | UNDP in the Asia and the Pacific. 2017.

- 21.Berli JU, Knudson G, Fraser L, et al. What surgeons need to know about gender confirmation surgery when providing care for transgender individuals: A review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:394–400. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bustos VP, Bustos SS, Mascaro A, et al. Regret after gender-affirmation surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9:e3477. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000003477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335:806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckwith N, Reisner SL, Zaslow S, et al. Factors associated with gender-affirming surgery and age of hormone therapy initiation among transgender adults. Transgend Health. 2017;2:156–164. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh D, Deogracias JJ, Johnson LL, et al. The gender identity/gender dysphoria questionnaire for adolescents and adults: further validity evidence. J Sex Res. 2010;47:49–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490902898728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamhane AR, Westfall AO, Burkholder GA, et al. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: Choice comes with consequences. Stat Med. 2016;35:5730–5735. doi: 10.1002/sim.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leinung MC, Urizar MF, Patel N, et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: Extensive personal experience. Endocr Pract. 2013;19:644–650. doi: 10.4158/EP12170.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Health Philippines Epidemiology Bureau. 2018 Integrated HIV Behavioral and Serologic Surveillance (IHBSS). Department of Health; 2021.

- 31.Grant JMM, Lisa A., Tanis Justin, et al. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; Washington: 2012. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guadamuz TE, Wimonsate W, Varangrat A, et al. HIV prevalence, risk behavior, hormone use and surgical history among transgender persons in Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:650–658. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9850-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngalob QT Celito, Barrera Jerome, Nacpil Paulette. The transformation of transsexual individuals. JAFES. 2013;28:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kailas M, Lu HMS, Rothman EF, et al. Prevalence and types of gender-affirming surgery among a sample of transgender endocrinology patients prior to state expansion of insurance coverage. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:780–786. doi: 10.4158/EP161727.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolan IT, Kuhner CJ, Dy GW. Demographic and temporal trends in transgender identities and gender confirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8:184–190. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.04.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson-Kennedy J, Warus J, Okonta V, et al. Chest reconstruction and chest dysphoria in transmasculine minors and young adults: comparisons of nonsurgical and postsurgical cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:431–436. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, et al. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8:219–227. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.06.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sineath RC, Woodyatt C, Sanchez T, et al. Determinants of and barriers to hormonal and surgical treatment receipt among transgender people. Transgend Health. 2016;1:129–136. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spack NP. Management of transgenderism. JAMA. 2013;309:478–484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.165234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, et al. Injustice at every turn. A report of the National. 2011.

- 41.Kuper LE, Stewart S, Preston S, et al. Body dissatisfaction and mental health outcomes of youth on gender-affirming hormone therapy. Pediatrics. 2020;145 doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: A Total Population Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:727–734. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19010080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Sluis WB, Steensma TD, Bouman M-B. Orchiectomy in transgender individuals: A motivation analysis and report of surgical outcomes. Int J Transgend Health. 2020;21:176–181. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2020.1749921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rafferty J. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142 doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drescher J, Haller E, Lesbian G. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2012. Position Statement on Access to Care for Transgender and Gender Variant Individuals. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loo S, Almazan AN, Vedilago V, et al. Understanding community member and health care professional perspectives on gender-affirming care-A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yi S, Sok S, Chhim S, et al. Access to community-based HIV services among transgender women in Cambodia: Findings from a national survey. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:72. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0974-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reback CJ, Ferlito D, Kisler KA, et al. Recruiting, linking, and retaining high-risk transgender women into HIV prevention and care services: An overview of barriers, strategies, and lessons learned. Int J Transgend. 2015;16:209–221. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2015.1081085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sherman ADF, Clark KD, Robinson K, et al. Trans* community connection, health, and wellbeing: A systematic review. LGBT Health. 2020;7:1–14. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2019.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shulman GP, Holt NR, Hope DA, et al. A review of contemporary assessment tools for use with transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4:304–313. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.