Abstract

The human copper-binding protein metallothionein-3 (MT-3) can reduce Cu(II) to Cu(I) and form a polynuclear Cu(I)4-Cys5–6 cluster concomitant with intramolecular disulfide bonds formation, but the cluster is unusually inert toward O2 and redox-cycling. We utilized a combined array of rapid-mixing spectroscopic techniques to identify and characterize the transient radical intermediates formed in the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) to form Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3. Stopped-flow electronic absorption spectroscopy reveals the rapid formation of transient species with absorption centered at 430–450 nm and consistent with the generation of disulfide radical anions (DRAs) upon reduction of Cu(II) by MT-3 cysteine thiolates. These DRAs are oxygen-stable and unusually long-lived, with lifetimes in the seconds regime. Subsequent DRAs reduction by Cu(II) leads to the formation of a redox-inert Cu(I)4-Cys5 cluster with short Cu–Cu distances (<2.8 Å), as revealed by low-temperature (77 K) luminescence spectroscopy. Rapid freeze-quench Raman and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy characterization of the intermediates confirmed the DRA nature of the sulfur-centered radicals and their subsequent oxidation to disulfide bonds upon Cu(II) reduction, generating the final Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster. EPR simulation analysis of the radical g- and A-values indicate that the DRAs are directly coupled to Cu(I), potentially explaining the observed DRA stability in the presence of O2. We thus provide evidence that the MT-3 Cu(I)4-Cys5 cluster assembly process involves the controlled formation of novel long-lived, copper-coupled, and oxygen-stable disulfide radical anion transient intermediates.

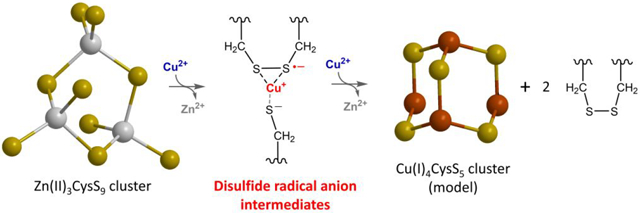

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Copper is an essential trace element in biology as a key cofactor in cuproenzymes for catalysis of otherwise challenging reactions such as molecular oxygen activation, electron transfer, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) inactivation.1 Due to its redox ability to cycle between Cu(I) and Cu(II) oxidation states at physiological redox potentials, cells require tightly controlled copper uptake and distribution mechanisms to prevent aberrant binding to proteins. This prevents redox-cycling and O2 activation via Fenton-type and Haber–Weiss chemistry that leads to toxic ROS production.2

Cu(I) is buffered and distributed in the reducing cytosolic environment via a network of copper binding proteins and small molecules (glutathione, GSH) responsible for Cu(I) delivery (chaperones) and potential buffering and storage (e.g., metallothioneins, MTs), maintaining free copper to less than one atom per cell.3 The characteristic Cu(I) coordination chemistry properties determine the nature of the Cu(I) sites in chaperones, MTs, and GSH complexes.4 While mononuclear digonal/trigonal Cu(I) sites via cysteines and methionines predominate in Cu-chaperones, polynuclear Cu(I) centers are generated in copper buffering/storage cuproproteins where they are often found as Cu(I)-thiolate clusters.4–7

Cu(I)-thiolate clusters are generally prone to oxidation in the presence of O2 via Cu(I) redox cycling, leading to oxygen reduction and disulfide formation, and their integrity is guaranteed by the reducing intracellular potentials. In selected cases, geometrical constraints from protein scaffolds can also provide additional shielding as in bacterial Csp3, possessing a four α-helix bundle with cysteine-lined cavities that bind Cu(I) as [Cu(I)4Cys5]−, [Cu(I)4Cys6]2−, and [Cu(I)4Cys5Asn]− clusters.8

In mammalian cells, MTs represent major Zn(II) and Cu(I) binding metalloproteins playing central metal homeostatic roles, with functions ranging from metal buffering (as demonstrated for Zn(II)) to metal detoxification and putative metal storage activities as well as possible metal chaperone-like functions.9–11 Human MTs are small proteins (6–7 kDa; 61–68 amino acids) that bind Zn(II) and Cu(I) with high affinity (KD, Zn(II) = 10−10/−11 M; KD, Cu(I) = 10−19/−21 M) via 20 conserved cysteines.5,12,13 Apo MTs are unstructured, and a characteristic protein fold develops upon metal coordination in two separate domains linked by a hinge region—the N-terminal β-domain and C-terminal α-domain.10 Zn7MTs feature a Zn3Cys9 cluster in the β-domain and a Zn4Cys11 cluster in the α-domain, with each Zn(II) tetrahedrally coordinated by terminal and μ2-bridging thiolates. Contrarily, Cu(I)4 and Cu(I)6-thiolate clusters can be formed in each domain by Cu(I) digonal/trigonal coordination, with the β-domain showing a higher Cu(I)-binding stability and cooperative formation of a Cu(I)4 Cys5–9 cluster.14–16 However, MTs are also secreted from cells where the oxidizing extracellular environment promotes copper redox-cycling, disulfide formation, and cluster collapse.10 Peculiarly, in the latter case, the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster in MT’s β-domain is inert to oxidation in the presence of O2.16

In humans, four main MT isoforms exist (MT-1 through MT-4), possessing a fully conserved array of 20 cysteines that participate in metal coordination to generate partially and fully metalated MT forms.11 While MT-1/−2 isoforms are ubiquitously expressed in different organs and tissues, the MT-3 isoform is predominantly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and possesses biochemical properties not shared by other isoforms.10,17 MT-3 was originally discovered in 1991 by Uchida et al. as a neuronal growth inhibitory factor (originally named nGIF), downregulated in Alzheimer’s disease patients, and capable of inhibiting neuritic sprouting of neurons.18 Upon determining its amino acid sequence, GIF was classified as MT-3 based on the conserved cysteine array and pattern as other MT isoforms. Among all mammalian MTs, MT-3 shows the highest Cu(I)-thionein character, and it is purified as Cu(I)4Zn(II)3–4 species when isolated from native sources (human and cow brain), suggesting that it might play important functions as a copper buffering and storage metalloprotein.10,12,17–19 MT-3 cooperatively forms a tetranuclear Cu(I)4-Cys5–9 cluster with short Cu–Cu distances (<2.8 Å) in the β-domain by either direct Cu(I) insertion or Cu(II) reduction.16 Under copper dysregulation and in the extracellular space, MT-3 can react with Cu(II), reducing it to Cu(I) and forming a similar Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster with concomitant formation of two intramolecular disulfide bonds in the same domain.16,20–23 Short Cu–Cu distances, allowing d10–d10 overlap and metal–metal bonding, result in an unusual redox stability. The cluster resists oxidation in the presence of O2 and biological reductants.16 This stability is deemed necessary for MT-3’s protective role in the CNS and in neurodegenerative diseases when Cu(II) homeostasis is dysregulated.16,20–24 Thus, MT-3 can efficiently scavenge free Cu(II) or remove aberrantly bound Cu(II) from target proteins.17 The pathway by which Cu(II) ions are reduced with concomitant disulfide formation and how the electron-transfer processes (involving protein-based radicals) take place in a controlled fashion without aberrant redox-activity, cluster oxidation, and collapse are unique and remain elusive.

To address this process, we characterized the pathway of Cu(I)4-cluster assembly upon reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) to form Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 and identified the transient intermediates in the process. As the reduction of four Cu(II) ions involves four one-electron transfers, three general schemes can be envisaged according to how each of the Cu(II)/Cu(I) and thiolate-disulfide couple, leading to copper reduction and disulfide formation: (1) two Cu(II) are simultaneously reduced by thiolates forming two thiyl radicals, which then react to form a disulfide bond, resulting in Cu(I) binding and Zn(II) release; (2) Cu(II) is initially reduced by a thiolate to Cu(I), forming a thiyl radical that sequentially reacts with an adjacent thiolate to form a disulfide radical anion (DRA), which then reduces a second Cu(II) to Cu(I) leading to disulfide bond formation; and (3) Cu(II) binds to thiolates and reacts via a concerted inner-sphere electron transfer resulting in DRA generation (without a thiyl radical intermediate) and subsequent Cu(II) reduction to generate a disulfide bond (a general scheme on how Cu(II)/Cu(I) and thiolate-disulfide can redox couple is presented in Figure S1). In this work, by utilizing a combined array of rapid-mixing spectroscopic techniques, we demonstrate that the Cu(I)-thiolate cluster assembly proceeds through the formation of novel long-lived, Cu-coupled, and redox-inert DRAs. This process provides a molecular mechanism for controlled Cu(I)-clusters assembly and stabilization of radical species in the oxidative biological milieu, thereby representing a central process for Cu(II) scavenging and redox silencing by a cuproprotein.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Recombinant Human MT-3 Expression, Purification, and Metal Reconstitution.

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)-pLys cells (Agilent) were transformed with a pET-3d plasmid (Novagen) encoding for human MT-3 and used for protein expression, following the method of Faller et al.25 Thirty min after 1 mM IPTG induction, 0.4 mM CdSO4 was added to the media to express the protein as the Cd-bound form. The CdMT was purified by ethanol/chloroform precipitation, size exclusion chromatography (SEC, Superdex 75 10/300), and ion exchange chromatography (HiPrep DEAE FF 16/10), using an Äkta Pure Chromatographic System (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), as reported in Faller et al.25 The apoprotein was subsequently generated by dropping the pH to 1.5–2.0 by concentrated HCl addition in the presence of guanidine-HCl (2 M) and the reducing agent DTT (20 times in excess over the thiols concentration), followed by SEC (HighPrep 26/10 Desalting) to remove free metals. Reconstitution to the Zn7MT form was performed by addition of 8 equiv of ZnCl2 followed by a slow adjustment of pH to 8.0, using 1 M Tris.26 Chelex 100 resin (10 mg/mL) was added to remove any unbound or weakly bound zinc, then the resin was filtered from the protein solution using a 0.45 μm vacuum filter unit. A final SEC step was conducted using a Superdex 75 10/300 column to generate the reconstituted Zn7MT-3 in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0). This buffer has been used for all experiments, unless stated. The protein concentration was quantified photometrically in 0.1 M HCl using ε220 = 53000 M−1 cm−1 (Cary 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer, Agilent). The concentration of free thiols was determined upon their reaction with 2,2-dithiodipyridine in 0.2 M sodium acetate/1 mM EDTA (pH 4.0) using ε343 = 7600 M−1 cm−1.27 The zinc content was determined by ICP-MS (Agilent 7900) on samples digested in 1% HNO3. The purity of the protein was confirmed by SDS-PAGE on samples subjected to monobromobimane modification following the method of Meloni et al.28

Reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II) followed by Stopped-Flow UV–vis Electronic Absorption Spectroscopy.

The reaction of Zn7MT-3 with 4 Cu(II) equiv (CuCl2, >99% purity) was analyzed by electronic absorption spectroscopy using a SX-20 stopped-flow spectrometer (Applied Photophysics). Absorption kinetic traces were recorded for 301 s upon mixing, at wavelengths between 220 and 800 nm (10 nm steps, 25 or 37 °C) using 10 mm path length and 2.325 nm bandpass. Zn7MT-3 stocks in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl (70 μL, 20 μM), and CuCl2 (70 μL, 80 μM in 80 μM HCl) were simultaneously injected and mixed, and absorbance at each wavelength recorded every 1 ms for the first 1 s and every 100 ms for the following 300 s. Kinetic traces at 220 and 260 nm were analyzed for ligand-to-metal charge-transfer (LMCT) contributions, while the trace at 450 nm was analyzed to characterize the formation of DRA. Kinetic traces at 220 and 260 nm, reflecting Zn(II) release and Cu(I) binding, respectively, showed at least a triphasic behavior and were fitted with a triple exponential function:

| (1) |

To obtain a finer resolution of the kinetic traces, the absorbance at 450 nm was additionally recorded every ms for 10 s. To determine the kinetic parameters of DRA formation and decay, similar experiments were conducted by adjusting the reactant concentrations to mimic pseudo-first-order conditions, with an excess of protein and thiolates over Cu(II), with a final Zn7MT-3 concentration of 72 μM (corresponding to 1.4 mM thiolates) or 100 μM (corresponding to 2 mM thiolates) and CuCl2 40 μM. The traces at 450 nm corresponding to DRA formation and decay were fitted with a combined double growth and exponential decay function (g and d denotes the growth and decay components, td1 and td2 corresponds to τ1 and τ1 of the decay phase, and xc corresponds to the transition time at which the two different equations are applied):

| (2) |

To characterize the sensitivity of the reaction intermediates toward molecular O2, the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) was investigated either with samples saturated with air upon extensive bubbling or oxygen-free samples obtained via degassing on a Schlenk line to remove O2 prior to injection to the stopped-flow spectrometer. The reaction was followed by analyzing the spectroscopic traces at 450 nm as described above. To compare the kinetics of the reaction between GSH and Cu(II), GSH (560 μM) was reacted with Cu(II) (80 μM) and the kinetics monitored between 220 and 750 nm (301 s, 25 °C).

Reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II) followed by Freeze Quenching Raman Spectroscopy.

Raman spectra (512 accumulations, 1 s, 30 mW on sample) were collected on a ThermoFisher DXR3 Raman microscope using a 785 nm laser and a 10× objective (spot size ~3 μm). Zn7MT-3 samples in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl were concentrated to ~1.4 mM in a final volume of ~100 μL using Amicon ultracentrifugal filters (3 kDa cutoff). Concentrated Zn7MT-3 was mixed with a Cu(II) stock (CuCl2 in water) (1:4 mol/mol) and allowed to react for 1 h at 25 °C. Zn7MT-3 and the product of the reaction (Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3) samples were subsequently frozen in liquid N2 and lyophilized using a FreeZone 2.5Plus benchtop freeze-dryer (Labconco) (0.135 Torr, −86 C) for 4–24 h and stored in a liquid N2 tank (Taylor-Wharton HC34 cryogenic storage tank). To trap the intermediates of the reaction, samples were generated by rapid mixing of Zn7MT-3 with the CuCl2 stocks and freeze-quenched in liquid N2 at 1, 5, and 20 s time points after mixing. Upon quenching, the samples were lyophilized and stored in liquid N2. A spectrum of 100 μL of buffer, lyophilized in an identical manner, was also examined. For the Raman spectra data collection, the lyophilized solids were placed on a CaF2 microscope slide and the spectra were acquired at ambient temperature using a second-order fluorescence correction. Spectra were baselined using the interactive baseline function and normalized to the amide signal at ~1660 cm−1 in Spectrum (PerkinElmer). The mean and standard deviation of two to three replicate spectra using separate aliquots of the lyophilized solid, which were kept on dry ice, were plotted in OriginPro 2021b (OriginLab).

Cu(I)4Zn(II)4 MT-3 Stability and β-Domain Cu(I)4 Cluster Formation: Electronic Absorption and Low-Temperature Luminescence Spectroscopies.

To confirm the formation of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 product, Zn7MT-3 in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (500 μL, 10 μM) was reacted with Cu(II) (1:4 mol/mol) for 1 h at 25 °C. A UV–vis electronic absorption spectrum was recorded between 220 and 800 nm using a Cary 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer (Agilent). To determine the stability of the product, the absorption spectra were recorded every 15 min for 24 h.

The formation of the Cu(I)4 cluster in the β-domain was confirmed by recording the low-temperature (77 K) luminescence emission spectra using a FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Scientific). In a 4.2 mm inner diameter quartz tube, Zn7MT-3 (400 μL, 10 μM) was reacted with Cu(II) (1:4, mol/mol) for 1 h before flash freezing the products using liquid N2. The emission spectrum (λexc: 320 nm, slit width: 5 nm) was recorded between 380 and 750 nm (slit width: 5 nm) at 77 K in a quartz dewar, using 10 μs initial delay and a 300 μs sample window. The decay lifetimes of the emissive bands at 425 and 575 nm were determined using a 75 μs initial delay and 300 μs sample window. Delay increments of 10 and 20 μs and maximum delays of 500 and 1000 μs were used for the 425 and 575 nm bands, respectively. To monitor the stability of the Cu(I)4-Cysx cluster, the reaction was quenched after 4, 8, and 24 h by flash freezing the samples in liquid N2, and the emission spectra and decay lifetimes recorded and determined as described above. As low-temperature luminescence is a surface measurement and overall emission intensity is only semiquantitative due to inhomogeneous freezing, multiple spectra were collected upon rotating the sample quartz tube in the LN2 dewar, and the standard deviation calculated on multiple replicates. The relative intensity of the emission bands at 575 and 425 nm for each collected spectra is independent of freezing and sampling position and thus used as indicative parameter to compare the nature of the products.

To determine whether the Cu(I)4-cluster is formed upon mixing, Zn7MT-3 (400 μL, 72 μM) in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0) was reacted with 4 equiv of Cu(II) and quenched at short incubation time points (1, 5, 10, 25, and 250 s) by flash freezing in liquid N2, the emission spectra were recorded and decay lifetimes determined as described above.

Characterization and Stability of the Products of the Reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) or Cu(I) in Absence of O2.

The products of the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) (CuCl2) or Cu(I) (tetrakis(acetonitrile)Cu(I) hexafluorophosphate) in absence of O2 were characterized by electronic absorption spectroscopy and low-temperature (77 K) luminescence. All solutions, including Zn7MT-3 and CuCl2 stocks, were made oxygen-free on a Schlenk-line by three vacuum/nitrogen cycles, while the tetrakis(acetonitrile)Cu(I) hexafluorophosphate stocks in acetonitrile were prepared directly in a nitrogen-purged anaerobic glovebox.

To characterize the products and their stability, absorption spectra were recorded every 15 min for 24 h as described above on samples placed in sealed cuvettes.

The formation of the Cu(I)4 cluster in the β-domain and its stability were confirmed by recording the low-temperature (77 K) luminescence emission spectra as described.

To investigate the cooperative formation and stability of the Cu(I)4-Cysx cluster generated during the aerobic or anaerobic reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II), similar low-temperature luminescence spectral analyses of the reaction products have been performed on samples generated with Zn7MT-3 excess (25 μM) over Cu(II) (10 μM).

Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 Sulfhydryl Content Determination.

To determine the number of reduced thiolates in the products of the aerobic reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) or Cu(I), Cu(I)4Zn-(II)4MT-3 solutions were acidified to pH = 1 to ensure complete metal release. Zn7MT-3 (40 μM, 500 μL) in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl was allowed to react with 4 equiv of Cu(II) (CuCl2 in water) for 1 h at 25 °C. The reaction mixture was concentrated to a final volume of 100 μL using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (cutoff: 3 kDa), washed with water, and further concentrated to 100 μL. The protein sample was then incubated in 1 M HCl for 15 min and then diluted by three washing cycles in 100 mM HCl (3 × 500 μL). The cysteine sulfhydryl groups were quantified photometrically via reaction with 2,2-dithiodipyridine in 0.2 M sodium acetate/1 mM EDTA pH 4.0 at 343 nm using ε = 7600 M−1 cm−1 and reported as [Cys]:[MT-3] (mol/mol) ratios. The protein concentration was quantified photometrically in 0.1 M HCl using ε220 = 53000 M−1 cm−1 (Cary 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer, Agilent).

The reaction of Zn7MT-3 with stoichiometric amounts of Cu(II) or Cu(I) (Cu:MT-3 4:1 mol/mol) was also performed in oxygen-free conditions, and the thiolate content determined following the same procedure.

Cu(I), Zn(II), MT-3 Metal Content Determination.

Metal-to-protein ratios in the products of the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) or Cu(I) and incubated at 25 °C up to 24 h were determined upon removing released metals through size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Samples were injected on a Superdex 75 10/300 Increase column connected to anÄkta FPLC system (GE Healthcare) and eluted with 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl.

Cu and Zn content in the eluted MT-3 samples was determined via ICP-MS (Agilent 7900) upon dilution in 1% HNO3. The protein concentration was quantified photometrically in 0.1 M HCl using ε220 = 53000 M−1 cm−1 (Cary 300 UV–vis spectrophotometer, Agilent), and metal-to-protein ratios were calculated.

Reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II) followed by Freeze Quenching EPR Spectroscopy.

To characterize the presence of radical intermediates, the reaction of Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) was followed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Zn7MT-3 (300 μL, 450 μM) in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0)/20% (v/v) glycerol) was mixed with Cu(II) (250 μM), and the reaction products were quenched at different time points: 1, 5, 10, 25, 250, and 1800 s by flash freezing in liquid N2 in EPR tubes. X-band EPR spectroscopy was performed on a Bruker EMX Plus spectrometer equipped with a bimodal resonator. Samples were run in perpendicular mode at a frequency of 9.64 GHz at both 15 and 30 K using an Oxford ESR900 cryostat and an Oxford ITC 503 temperature controller at microwave power 317 μW and 126 μW, respectively. Simulations on all spectra were performed using the general spin Hamiltonian (eq 3) using SpinCount, developed by Dr. Michael Hendrich at Carnegie Mellon University:

| (3) |

Here, is the g-tensor and is the nuclear hyperfine interaction, which is treated with second-order perturbation theory.29 Simulations take into consideration all intensity factors, both theoretical and experimental. The concentration of species can be used as a constraint during spectral simulation, which allows quantitative determination of the concentration by comparison of the experimental and simulated signal intensities.30 The only unknown factor relating the spin concentration to signal intensity is an instrumental factor that depends on the microwave detection system. This factor is determined using a Cu(II)EDTA spin standard.31

For Cu(II) and DRA signals, microwave powers were selected to achieve the best signal-to-noise ratio while minimizing loss of signal due to microwave saturation. Half-power microwave saturation (P1/2) values reported for selected samples were determined by collecting scans at increasing microwave power and fixed scan rate and field width. The signal area as a function of microwave power was fit using the SpinCount software package according to eq 4:

| (4) |

The software performs least-squares fitting of the normalized derivative signal intensity (S) as a function of microwave power (P). The A term represents the normalized maximum signal amplitude. From this analysis, it was determined that ≥20% attenuation of signal intensity was observed for Cu(II) and DRA at 15 and 30 K, respectively.

To determine if radical intermediates could be chemically trapped, samples of Zn7MT-3 (450 μM) were prepared in a buffer containing 45 mM 5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). This solution was rapidly mixed with the same volume of Cu(II) (250 μM) and quenched at selected time points (1, 5, 25, and 250 s). In principle, DMPO could participate in promiscuous reactions with radicals and/or Cu(II). Therefore, analogues samples were prepared by addition of DMPO after mixing Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) at selected time points (35, 50, and 930 s) for comparison. These samples were subsequently quenched 30 s after DMPO addition.

EPR spectra were also recorded for the reaction of GSH (2 mM in 25 mM tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (pH 8.0)/20% (v/v) glycerol) with Cu(II) (500 μM) and quenched at 1, 5, and 30 s.

Reaction of GSH with Cu(II) followed by UV–vis spectroscopy.

The spectra were recorded every 10 min over a period of 24 h on a Cary 60 spectrophotometer at room temperature (22–24 °C) in the spectral range 250–850 nm in 1 cm quartz cuvettes (Hellma). A 500 mM potassium phosphate buffer stock at pH 7.4 was prepared by mixing potassium dihydrogen phosphate 99% (KH2PO4) with potassium hydrogen phosphate 98% (K2HPO4) in Milli-Q water. Stock solutions were further diluted to the desired 100 mM concentration for the following experiments. 200 mM reduced GSH stock solutions were prepared immediately before the experiment and appropriate portions for the 7:1, 5:1, 3:1, and 1:1 (GSH:Cu) ratios were added to the cuvette containing 1 mM Cu(NO3)2 to obtain final GSH concentration of 0.35–2.45 mM and Cu(II) 0.35 mM. Experiments with such different ratios gave qualitatively the same general results, differing only by the Cu(I) reoxidation time, which was correlated with the excess of GSH not bound to Cu(I). The Cu(I) reoxidation to the Cu(II) complex of GSSG was enabled by oxidative exhaustion of GSH by ambient oxygen, as verified by ESI-MS.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Transient Characterization of Reaction Intermediates by Stopped-Flow Absorption Spectroscopy.

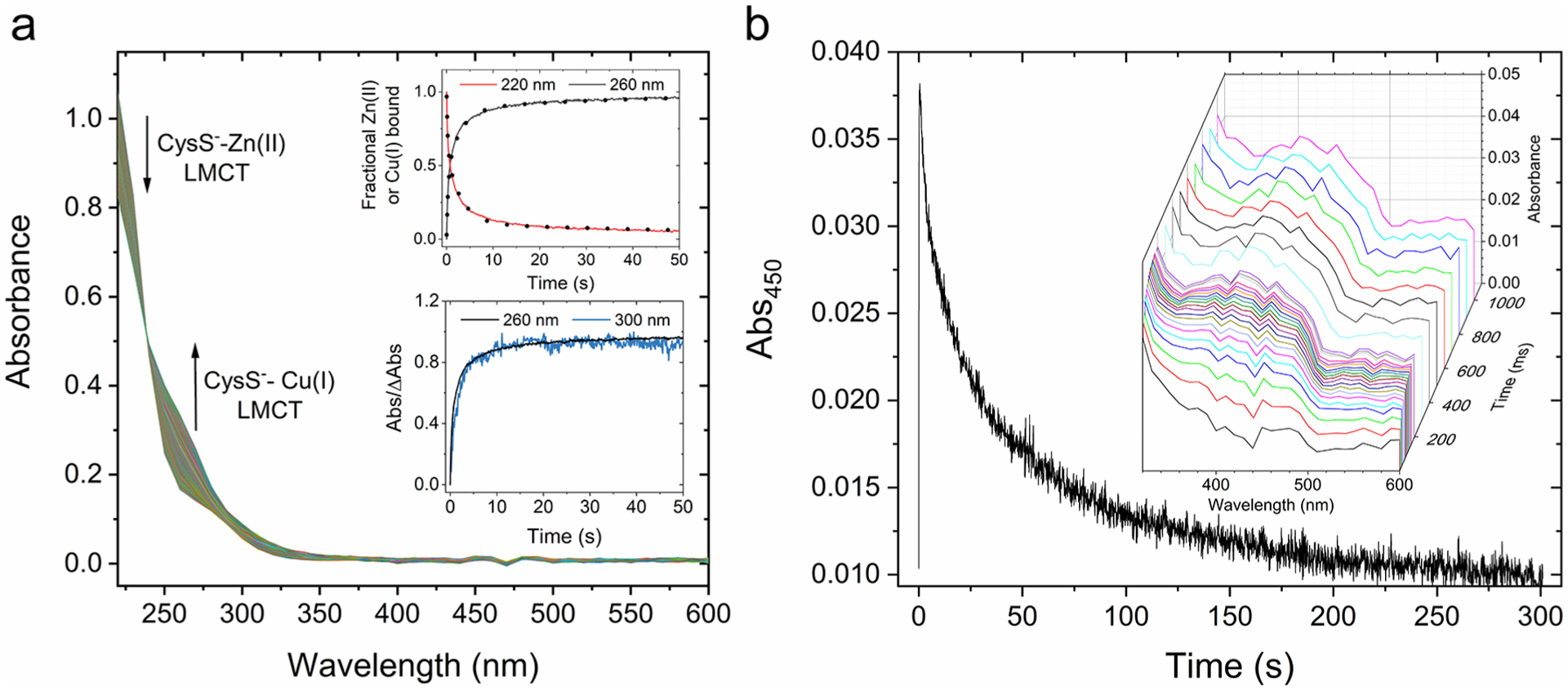

To monitor the evolution of the reaction intermediates between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II), we utilized stopped-flow UV–vis electronic absorption spectroscopy under stoichiometric (4:1 Cu(II):Zn7MT-3, mol/mol) and MT-3 excess over Cu(II) to study the reaction. Kinetic traces upon reaction of Zn7MT-3 with 4 Cu(II) equiv (220–800 nm) were recorded at 10 nm intervals (Figure 1a). The Zn(II)/Cu(I) exchange reaction was followed by the kinetic traces at wavelengths corresponding to the first LMCT transition for Cys-Zn(II) (220 nm) and for Cys-Cu(I) (260 nm). The time-dependent decrease of Cys-Zn(II) LMCT contributions paralleled by the increase in Cys-Cu(I) LMCT at 260 nm confirm Zn(II) release and Cu(II) reduction/Cu(I) binding, respectively (Figure 1a, top inset).12 The normalized Cu(I) binding and Zn(II) release traces could be best fit with a triple exponential equation indicating that the overall metal exchange is at least a triphasic process consistent with the presence of intermediates formed in the reaction (Figure 1a, top inset).

Figure 1.

Reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) followed by stopped-flow electronic absorption spectroscopy. (a) Absorption spectra upon reaction of Zn7MT-3 in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (10 μM) with Cu(II) (40 μM) at 37 °C, recorded every ms for the first 1 s, and 100 ms for the remaining 300 s. Inset: (top) Kinetic traces at 220 and 260 nm monitoring the fraction of bound Zn(II) or Cu(I), respectively, and corresponding fits with eq 1 (dotted line; for traces at 220 nm, t1= 0.23 s, t2 = 3.1 s, t3= 75.6 s, R2 = 0.9994; for traces at 260 nm, t1= 0.31 s, t2 = 2.8 s, t3= 36.0 s, R2 = 0.9996); (bottom) corresponding differential kinetics traces at 260 and 300 nm. The absolute differential absorption at time t is normalized over the total differential absorption at the completion of the reaction (ΔAbst/ΔAbsmax,, with t0 = 0 s and tf = 301 s). (b) Kinetic trace at 450 nm upon reaction of Zn7MT-3 (100 μM) with Cu(II) (40 μM). Inset: Reconvoluted spectra kinetics between 320 and 600 nm in the initial part of the reaction (1 s; 10 ms steps up to 100 ms; 100 ms steps up to 1 s).

In the product of the reaction, Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3, weak absorption contributions extend to approximately 320 nm, resulting from the overlay of LMCT absorptions tails (maximum at 262 nm) and weak cluster-centered transitions at approximately 280–320 nm arising from Cu(I)4-Cys5–6 cluster formation.16 No additional absorption above 350 nm is observed. Analysis of the kinetic spectra through reconvolution of single wavelength traces under both stoichiometric or pseudo-first-order conditions (with more than 10-fold excess of total MT-3 Cys over Cu(II)) revealed, in the course of the reaction, the formation of a transient weak and broad absorption band centered at approximately 430–450 nm (Figure 1b, inset, and Figure S2). The energy of this band is consistent with DRA species,32,33 as also observed when short-lived DRA intermediates (with lifetimes in the μs range) are generated upon HO• reaction with MT thiolates.34 Contrarily, in the reaction between MT and Cu(II), the absorbing species forms rapidly in the milliseconds time scale, peaks at ~1 s, but is then consumed slowly supporting the formation of an unusually long-lived disulfide radical anion (Figure 1b and Figure S2).

Despite potential Cys-Cu(II) LMCT transitions could contribute to strong absorption bands in the visible region (>400 nm) in tetrahedral type-1 Cu(II) centers,35–37 no evidence of transient formation of T1 Cu(II) complexes is observed in the EPR analysis upon Cu(II) binding to MT-3 prior to reduction (vide infra, Table 2). Studies of model mononuclear Cu(II) and mixed valence Cu(I)/Cu(II) complexes containing cis-N(amine)2S(thiolate)2 copper ligands indicate that, for planar tetragonal Cu(II) complexes, typical σ(S)-Cu(II) LMCT are centered below 400 nm, with few examples showing extremely weak π(S)-Cu(II) LMCT contributions extending above 400 nm.38–40 On the other hand, σ- and π(S)-Cu(II) LMCT transitions are red-shifted in the visible region when significant distortion toward tetrahedral coordination and higher covalency in the thiolate-Cu(II) bond occur, resulting in Cu(II) complexes that mimic T1 Cu(II) centers.35,39 Our EPR analysis of the hyperfine splitting in the parallel region observed upon rapid mixing of Cu(II) with Zn7MT-3 (see Table 2 below) shows spectral parameters consistent with standard tetragonal Type-2 Cu(II) complexes. This observation, together with the unambiguous identification of a transient S = 1/2 radical species in the EPR spectrum with comparable decay rates (vide infra), support major contributions to the origin of the observed absorption centered at 430–450 nm by the formation of DRA species (with an estimated ε450 ~ 2000 M−1 cm−1 based on stopped-flow absorption traces). Nevertheless, additional minor absorption contributions in this spectral region originating form weak overlapping π(S)-Cu(II) LMCT as a result of Cu(II) binding to MT-3 prior to reduction cannot be excluded.

Table 2.

EPR parameters for the species formed upon mixing Zn7MT-3 or GSH with Cu(II)a

| g z | g y | g x | A z | A y | A x | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) in buffer | 2.232 | 2.076 | 2.041 | 599 | - | - |

| Cu(II) + MT-3 | 2.231 | 2.064 | 2.019 | 516 | - | - |

| radical | 2.040 | 2.004 | 2.004 | 112 | 112 | 60 |

| Cu(II) + GSH | 2.265 | 2.097 | 2.053 | 555 | 63.4 | 16.6 |

Spectroscopic g- and A-values (MHz) determined by EPR simulations for the paramagnetic species investigated in this work.

Thiyl radicals are generated and observed in MTs upon reaction between hydroxyl radicals (OH•), generated from H2O via pulse radiolysis, and MT cysteine thiolates.34 As observed in this reaction as well as with low molecular weight thiols, thiyl radicals can efficiently react with a second thiolate to generate a disulfide radical anion in an equilibrium reaction preceding the DRA formation:34

| (i) |

To address whether the DRA in MT-3 is formed through Cu(II) reduction by a protein thiolate generating a thiyl radical and consequent reaction with a second thiolate to generate DRA, we analyzed the kinetic traces in the initial part of the reaction. Thiyl radicals possess a weak absorption maximum around 300 nm.41 Kinetic traces at 300 nm did not show evident absorbing intermediate species that are formed and consumed during reaction prior to the DRA formation. Comparison of the kinetics profiles at 300 nm (thiyl radical maximum) with the one at 260 nm centered at the first Cys-Cu(I) LMCT suggests that the residual absorption at 300 nm arise from Cys-Cu(I) LMCT tailing and weak contributions of cluster-centered (CC) transitions resulting from Cu(I)4-thiolate assembly (Figure S3 and 1a, bottom inset). However, due to the significantly more intense absorption contributions at 300 nm by LMCT and CC transitions, we cannot exclude that thiyl radical absorption is masked, and absorption spectroscopy cannot unambiguously exclude the formation of a thiyl radical intermediate in the micro-to-millisecond time scale prior to DRA formation. In addition, stable thiyl radicals have been observed upon UV irradiation in yeast Cu(I)6-MT, resulting in blue color species with a reflection spectra maximum at approximately 600 nm.42,43 In the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II), we did not observe any blue color development in freeze-quenched lyophilized samples, and no absorption maximum at 600 nm was observed in stopped-flow experiments. Thus, no direct evidence for the formation of a similar thiyl radical has been obtained in the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II).

Raman Spectroscopy.

To provide additional evidence for disulfide radical anion formation in the reaction between Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II), the Raman spectrum was acquired for lyophilized Zn7MT-3, for the final product of the reaction (Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3), and for samples freeze-quenched at 1, 5, and 20 s after mixing and immediately lyophilized at ultralow temperature. In proteins, disulfides are expected to possess diagnostic Raman signals between ~510 and ~520 cm−1 due to S–S stretching vibrations.44 Upon mixing Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II), we observe the appearance and evolution of a Raman band in the S–S stretching region (Figure S4). In the initial Zn7MT-3 spectrum, a weak signal at 525 cm–1 is observed that we attribute to amino acid (potentially alanine) vibrations.45 However, in the sample freeze-quenched after 1 s upon Cu(II) addition, a new strong signal at ~507 cm−1 appears. This signal decreases in intensity and progressively blue shifts to ~513 cm−1 in samples freeze quenched at 5 and 20 s after mixing and is present in the final product of the reaction. Based on resonance Raman studies of thiocyanates,46 formation of sulfur-centered radical anion species is expected to red shift the S–S signal due to the electrons occupying antibonding orbitals.46 Thus, the 507 cm−1 signals observed at 1 s after Cu(II) addition are consistent with the formation of a disulfide radical anion. The evolution of the ~507 cm−1 radical anion signal to the typical position at ~513 cm−1 for an S–S bond is also consistent with the presence of disulfide bonds in the final product of the reaction. A number of other changes are observed in the Raman spectra upon reaction with Cu(II) in the amide band region, in the spectral region between 800 and 600 cm−1, where C–S stretching modes are detected, and in spectral region below 500 cm−1, where multiple bands attributable to the metal–S stretching modes occurs. These further support significant changes in protein conformation and metal cluster structure upon formation of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 and will be explored and assigned in detail in future work.

Cu(I)4-Thiolate Cluster Assembly and Stability.

The formation of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 product was confirmed by electronic absorption and low-temperature luminescence spectroscopy (Figure 2). The absorption spectra matched in intensity and position to the characteristic envelope arising from LMCT and cluster-centered contributions distinctive of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 (Figure 2a).16 Analysis of the extinction coefficient at the center of the first Cys-Cu(I) LMCT at 262 nm reveals an ε = 21340 ± 1170 M−1 cm−1. Based on the molar absorptivity of ca. 3750 M−1 cm−1 per cysteine thiolate-Cu(I) bond at 262 nm,15 the number of thiolate ligands involved in Cu(I) coordination can be estimated to be approximately 5–6 (5.69 ± 0.31 Cys-Cu(I)/MT-3, mol/mol) consistent with the formation of a Cu(I)4Cys5 cluster and the presence of two disulfide bonds in the same domain. To further confirm disulfide bond formation in the product of the reaction, we quantified the amount of sulfhydryl groups in the product of the reaction (Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3) vs the reactant (Zn7MT-3). Zn7MT-3 and Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 were subjected to acidification to release Zn(II) and Cu(I), and the free sulfhydryl content determined upon reaction with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine (DTDP). The results revealed 20.18 ± 0.53 Cys in Zn7MT-3 and 16.34 ± 0.21 for Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3, in agreement with the formation of two disulfide bonds upon reduction of 4 Cu(II) (Table S1). Metal-to-protein stoichiometries were also verified upon size exclusion chromatography (SEC) purification of the products of the reactions, confirming the expected metal composition (Table S2).

Figure 2.

Electronic absorption and luminescence spectroscopic characterization of the products of the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) or Cu(I), in the presence and absence of O2. (a) Electronic absorption spectra of Zn7MT-3 (10 μM) and Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by aerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 (10 μM) with Cu(II) (40 μM) incubated in air for 24 h. (b) 77 K luminescence emission spectrum of Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by aerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II) and incubated in air for 24 h. (c) Electronic absorption spectra of Zn7MT-3 (10 μM) and Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by anaerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II) and incubated in N2 atmosphere for 24 h. (d) 77 K luminescence emission spectrum of Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by aerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II)incubated in air for 24 h. (e) Electronic absorption spectra of Zn7MT-3 (10 μM) and Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by anaerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(I) and incubated in N2 atmosphere for 24 h. (f) 77 K luminescence emission spectrum of Cu4Zn4MT-3 (10 μM) generated by anerobic reaction of Zn7MT-3 with Cu(I) incubated in N2 for 24 h.

The presence of the Cu(I)4 cluster in the β-domain was confirmed via low-temperature (77 K) luminescence spectroscopy (Figure 2b). The MT-3 β-domain Cu(I)4-cluster exhibits a sharp emission band at 425 nm with triplet CC origin and a broader emission band at 575 nm with triplet charge-transfer (CT) origin.14,16,47 The presence of the high-energy emission band is diagnostic of Cu(I)4-thiolate clusters with short Cu–Cu distances (<2.8 Å) allowing the d10–d10 overlap (Table S3).14,47 The resulting metal bonding character underlies the unusual stability of Cu4Zn4MT-3 in the presence of O2.

The effect of O2 in the generation of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 was also investigated by performing the same reaction in N2 atmosphere utilizing oxygen-free reactants. The absorption spectra of the product of the reaction matched the characteristic envelope and intensity arising from LMCT and cluster-centered contributions distinctive of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 (Figure 2c). Analysis of the extinction coefficient at the center of the first Cys-Cu(I) LMCT at 262 nm reveals an ε = 21190 ± 1450 M−1 cm−1 identical to the one observed in the presence of oxygen, corresponding to 5–6 thiolate-Cu(I) bonds (5.65 ± 0.39 Cys-Cu(I)/MT-3, mol/mol) present in a Cu(I)4Cys5 cluster. Consistently with 2 disulfide bonds formed in the product of the reaction, sulfhydryl group determination revealed 16.47 ± 0.42 thiolates (Cys/MT-3, mol/mol) present in the product. Thus, O2 does not influence the nature of the products generated in the aerobic reaction between Zn7MT-3 with Cu(II). Consistently, low-temperature (77 K) luminescence spectra, relative band intensity, and band decay lifetimes were identical in the product of the reaction in presence and absence of oxygen (Figure 2d and Tables S3 and S4).

To further confirm that the reaction between Cu(II) and Zn7MT-3 involves redox processes between copper and the cysteine thiolates, as a control, the product of the reaction (Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3) was also generated by direct incorporation of Cu(I), to form the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster, in oxygen-free atmosphere. Under these conditions, no redox processes are expected to occur. The absorption spectra matched the characteristic envelope arising from Cys-Cu(I) LMCT and cluster-centered contributions distinctive of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 (Figure 2e). However, the determined extinction coefficient of the first Cys-Cu(I) LMCT at 262 nm revealed an ε = 33380 ± 910 M−1 cm−1, corresponding to 8.94 ± 0.24 thiolate-Cu(I) bonds. This analysis indicates that all Cys residues in the β-domain are involved in metal coordination to form a Cu(I)4Cys9 cluster, which is thus distinct compared to the one generated upon reduction of Cu(II). In agreement, sulfhydryl groups quantification with DTDP revealed a Cys-to-protein ratio of 20.15 ± 0.40 (Cys/MT-3, mol/mol; Table S1) in the product of the reaction, confirming the absence of disulfide formation and redox processes occurring between copper and thiolates when Cu(I) is used as a source. Consistently, low-temperature (77 K) luminescence spectra showed an increased relative intensity of the emission band at 575 nm (with CT origin) over the triplet CC band at 425 nm, indicating differences in the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster structure upon direct Cu(I) binding to MT-3 compared to cluster formation upon Cu(II) reduction (Figure 2f and Table S5).

The stability of Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 generated upon reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) in the presence of oxygen was also verified by exposing the protein to air and recording the absorption spectra for 24 h (Figure 2). No spectral changes in the course of time confirmed no change in LMCT absorption intensity contribution and absence of metal release in the presence of O2, as observed in anaerobic conditions (upon reaction with Cu(II) or direct Cu(I) binding, Figure 2a,c,e), demonstrating that Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 is significantly inert to oxidation. Consistently, the low-temperature emission spectra of samples incubated in air (1–24 h) revealed similar emission envelopes (Figure 2b). As low-temperature luminescence is only a surface semiquantitative measurement, we determined the decay lifetimes of the emissive bands at 425 and 575 nm and relative band intensities to demonstrate Cu(I)4-cluster integrity, as deviations from the expected values would indicate a change in the cluster structure upon oxidation. Analysis revealed no significant change over 24 h (Table S3), confirming the stability of the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster. Similar behaviors were observed for reaction with Cu(II) or Cu(I) in the absence of oxygen (Tables S4 and S5). Additionally, metal-to-protein ratios determined for the products of the reactions incubated up to 24 h and separated via SEC to remove any released metal, originating from time-dependent cluster oxidation, confirmed constant and correct metal stoichiometries in Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 (Table S2).

To verify rapid Cu(I)4-cluster formation in the products of the reaction between Cu(II) and Zn7MT-3, we monitored the products at short quenching times by luminescence spectroscopy. The reaction was quenched by flash freezing in liquid N2 (1–250 s), and emission spectra and lifetimes were recorded (Figure 3). The development of the characteristic Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 spectra at short time scales (after 1 s approximately 50% of the maximal intensity) mirroring the kinetics of Cu(II) reduction to Cu(I) in the Cys-Cu(I) LMCT traces, together with the preservation of characteristic lifetimes (Table 1), reveal the immediate rearrangement upon reduction to form the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster.

Figure 3.

Time-dependent Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster formation analyzed by low-temperature luminescence spectroscopy. (a) 77 K luminescence emission spectra of the product of the reaction between Zn7MT-3 (72 μM) 40 μM Cu(II) upon freeze-quenching at short incubation times (1–250 s). (b) Determination of emission lifetimes at 425 and 575 nm after 1 s reaction, fitted using a single exponential decay function.

Table 1.

Cu(I)4-Thiolate Cluster Formation Analyzed by Low-Temperature Luminescence Spectroscopya

| time (s) | lifetime (μs) | |

|---|---|---|

| 425 nm | 575 nm | |

| 1 | 40.1 | 104.4 |

| 5 | 40.1 | 108.6 |

| 10 | 40.0 | 107.5 |

| 25 | 39.6 | 109.0 |

| 250 | 41.8 | 120.9 |

Low-temperature (77 K) luminescence lifetimes of the 425 and 575 nm bands of the products of the reaction between Zn7MT-3 (10 μM) and Cu (40 μM), quenched at short time points.

Moreover, similar luminescence spectra and lifetime measurements were conducted to characterize the reaction under pseudo-first-order conditions with MT-3 excess over Cu(II). The occurrence of the two emissive bands diagnostic of the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster formation with identical relative intensity and lifetimes as observed for stoichiometric conditions (4:1 Cu:MT-3, mol/mol) (Figure S5 and Table S6) unambiguously revealed that Cu(I)4-cluster assembly upon Cu(II) reduction is a highly cooperative process in which the metal-cluster formation within MT-3 molecules is thermodynamically favored over formation of intermediate species with lower Cu(I)-binding stoichiometries.

Cu(II) Reduction and Cu(I)-Cluster Assembly and Stability in GSH vs MT-3.

Similar to MT-3, the thiol-containing tripeptide GSH possesses a putative role in protecting cells from Cu(II) toxicity via similar sulfur-centered redox reactivity, acting as a cytosolic reductant, radical scavenger, and a ligand for soft metals such as Cu(I).6,48 Through its cysteine residue, GSH can also reduce Cu(II) to Cu(I). As a consequence of its ability to both directly bind Cu(I) or reduce Cu(II) prior to Cu(I) binding, GSH can form polynuclear Cu(I)x-GSHy species, with Cu(I)4-GSH6 predominant at physiological pH.6 The formation of this species is expected to contribute to limit the free Cu(I) to the subfemtomolar range despite other higher affinity unidentified ligands are expected to maintain cytosolic labile Cu(I) levels below attomolar levels in normal homeostatic conditions.6,49

To address whether the cluster assembly pathway and stability is unique to MT-3, we investigated Cu(II) reduction and binding to GSH. We monitored GSH-mediated Cu(II) reduction and Cu(I) binding to the thiolates and determined the stability of the reaction products by electronic absorption kinetics (Figure S6a). Upon mixing GSH with Cu(II), the initial formation of a complex absorption envelope below 400 nm arising from GSH-Cu(I) LMCT and cluster-centered transition confirmed Cu(II) reduction and Cu(I)-cluster formation. However, the progressive appearance over time of Cu(II) d–d transitions centered at ~620 nm originating from the Cu(II)-GSSG complex50 revealed a time-dependent reoxidation of the Cu(I) centers and concomitant GSH oxidation. Thus, differently than Cu(I)4Zn4(II)MT-3, GSH-Cu(I) clusters are not stable nor redox-inert in the presence of O2.

By stopped-flow spectroscopy, we also addressed whether a long-lived disulfide radical anion is generated in the process. GSH and Cu(II) were mixed, and the kinetics traces at 450 nm were recorded (Figure S6b). In contrast to MT-3, no fast formation and slow consumption of the DRA intermediates were observed, and only the progressive reduction of Cu(II) signals was evident in the EPR spectra. In agreement, the presence of a residual kinetic trace tail at 450 nm indicated that the expected GSH-DRA species are rapidly formed and consumed (<10 ms).

DRA Stability toward O2 in MT-3.

The stoichiometric formation of the Cu(I)4-cluster in MT-3 and its stability toward O2 is striking. Sulfur-centered radicals are effectively quenched upon reaction with O2 to form RSOO• and RSSR, respectively:

| (ii) |

| (iii) |

When HO• reacts with M(II)7MTs (M = Zn(II)/Cd(II)) to produce thiyl radicals and DRA, the presence of O2 results in a decrease of DRA formed as a result of both quenching of thiyl radical (thereby reducing the amount that reacts to form the DRA) and the DRA to form disulfides leading to extensive protein oxidation.34 While the reaction of DRA with O2 in MTs (k ~ 3 × 107 dm3 mol−1 s−1) is an order of magnitude slower than that of cysteine (k = 4.9 × 108 dm3 mol−1 s−1) or glutathione (k = 1.6 × 108 dm3 mol−1 s−1) due to the more screened nature of the radical in the protein structure, its sensitivity to oxidation is responsible for metal-clusters collapse when radicals are generated upon reaction with HO•.34

By contrast, the generation of DRA to form the Cu(I)4-cluster investigated in this work results in an alternative reaction mechanism and insensitivity to dioxygen. We monitored the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) under anaerobic conditions and within air-saturated buffer. Reaction progress was monitored at 450 nm by stopped-flow UV–vis spectroscopy. Remarkably, the presence of molecular oxygen reveals no apparent change in the amount of putative DRA intermediate accumulated in kinetic traces (Figure 4a and inset). This suggests a unique DRA stability and its inertness toward oxidation by O2, underlying its unique long-lived nature.

Figure 4.

DRA intermediates lifetimes and stability toward O2 analyzed by stopped-flow electronic absorption spectroscopy. (a) Kinetic traces at 450 nm of the reaction of Zn7MT-3 in 25 mM Tris-HCl/50 mM NaCl (10 μM) with Cu(II) (40 μM) at 37 °C, in the presence or absence of O2. Inset: First 10 s of reaction. (b) Kinetic trace at 450 nm and corresponding fitting with a double exponential growth and decay function (eq 2 in Material and Methods) upon reaction between Zn7MT-3 (72 μM) with Cu(II) (40 μM) at 25 °C. The observed decay constants (λ) and τ values are reported. (Inset) Experimental and kinetic trace at 450 nm in logarithmic base scale to highlight quality of the fit at ms time scales (R2 = 0.9979; tg1= 0.012 s; tg2= 0.068 s; td1= 3 s; td2= 53 s).

The HO•-mediated formation of MTs DRA follows first-order kinetics with respect to thiolate concentration. Moreover, the observed kinetics are consistent with an intermolecular reaction between a thiyl radical and a thiolate in a second MT molecule, resulting in protein dimerization and oligomerization.34 Moreover, the decay of the DRA radical to generate disulfide bonds is very rapid (half-life in the μs regime).34 Contrarily, in Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3, disulfides are formed intramolecularly upon Cu(II) reduction in a controlled fashion.16 We recorded kinetic traces at 450 nm under pseudo-first-order conditions at 25 °C with an approximately 45-fold excess of protein thiolates over Cu(II), mimicking the conditions utilized for subsequent EPR characterization. The absorption trace at 450 nm was best fitted with a double growth and double exponential decay function (possibly suggesting the existence of 2 distinct DRA species, expected to form and subsequently be consumed in the overall reduction of 4 Cu(II) in the complete reaction), with resulting observed decay constants (λobs) of ~0.02–0.3 s−1, corresponding DRAs decay lifetimes with τ in the seconds regime (Figure 4b and inset). The best fit with a double exponential decay suggesting the existence of 2 DRA species populations is consistent with the final formation of 2 disulfide bonds in each MT-3 molecule, though a reaction bifurcation cannot be completely excluded. The process of DRA generation, that is complete in the millisecond time scale, and the decay occurring in the seconds time scale mirror the multiphasic kinetics observed at 220 and 260 nm diagnostic of Cu(I) binding and Zn(II) release. Thus, the DRAs formed in the reaction with Cu(II) are unusually stable and long-lived and peculiar in the formation of protein-based Cu(I)-clusters systems. This corroborates a unique mechanism for the Cu(I)4-cluster assembly pathway.

DRA Spectroscopic Characterization by EPR Spectroscopy.

Rapid-mix freeze-quench (RFQ) samples were prepared for characterization by X-band EPR spectroscopy to corroborate formation of the DRA during assembly of the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster. In these experiments, an equal volume of Zn7MT-3 (225 μM) and Cu(II) (125 μM) was mixed under pseudo-first-order conditions, and products of the reaction were freeze-quenched in liquid N2 at selected time points ranging from 1 to 1800 s. Analysis of RFQ EPR spectra (Figure 5) reveal two spectroscopically distinct S = 1/2 species within the g ~ 2 region, which can be attributed to an axial Cu(II) species and an anisotropic nonmetallic radical with quartet hyperfine splitting.

Figure 5.

RFQ EPR characterization of the intermediates formed in the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II). X-band EPR spectra recorded at 15 K (a, c) and 30 K (b, d) upon rapid-mixing Zn7MT-3 (225 μM) with Cu(II) (125 μM). Samples were quenched in liquid nitrogen at selected time points ranging from 1 to 1800 s. Quantitative simulations of 1 s RFQ sample at 15 K (c) and 30 K (d) were used to determine the contributions from Cu(II) and DRA species.

The individual contribution from each species was determined by quantitative simulation of Cu(II) (Figure 5c) and radical EPR (Figure 5d) spectra. A summary of spectroscopic parameters determined by simulation is provided in Table 2.

For the purposes of analytical quantitation, EPR data were collected at 15 and 30 K to minimize saturation effects on the Cu(II) and radical signals, respectively (Figure 5a,b). At these temperatures, the microwave power for half-saturation (P1/2) is 0.59 mW for Cu(II) and 0.16 mW for the radical (Figure S7). The deviation in observed g- and A-values for Cu(II) present in buffered solution relative to MT-3 (Figure S8 and Table 2) indicates that the Cu(II) ion binds to MT-3 prior to being reduced to the EPR silent Cu(I). This observation is consistent with an inner-sphere reduction process. The observed g-values exhibited by the radical species are consistent with values reported for DRA species assigned by absorption or EPR spectroscopy.32,51–54 Moreover, these values are inconsistent with the assignment of a thiyl- or persulfide radical.32,55,56

A useful metric for distinguishing thiyl radicals from DRAs is the maximum numerical g-value (gmax). Thiyl radicals typically show much greater anisotropy, with gmax values up to 2.23 reported.55,57–60 By contrast, typical gmax values for DRAs are smaller (2.02–2.04).51–54 Thus the gmax value reported here (2.04) is consistent with the assignment of a DRA. A comparative analysis of g-values observed in thiyl radicals, perthiyl radicals, and disulfide radical anions in a variety of small molecule and proteins and theoretical values calculated by DFT/MCSCF methods is presented in Table S7.

The observed quartet splitting of equally intense nuclear transitions is consistent with the radical coupling to an I = 3/2 nucleus such as 63Cu or 65Cu (natural abundance 69% and 31%). The large axial hyperfine splitting [A∥ ~ 112, A⊥ 60 MHz] could imply direct DRA coordination to the Cu(I) nuclei, which may also explain the observed stability of the DRA in the presence of oxygen, and its long lifetime.

Shown in Figure S9 are the concentrations of Cu(II) and radical species quantified by EPR simulations as a function of quench time. Both species show a decrease over the progression of the reaction and closely match the rate of decay observed for the DRA by stopped-flow UV–vis spectroscopy (Figure 4b), the evolution of the Raman band in the disulfide region, and the development of Cys-Cu(I) LMCT transitions (Figure 1a, top inset). EPR analysis is consistent with the assignment of the transient but long-lived radical species to DRAs. Further, the absence of any other radical intermediate suggests a concerted inner-sphere DRA-based mechanism for the assembly of the MT-3 Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster.

Experiments with the nitrone spin-trap (5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide, DMPO) were performed to evaluate the reactivity of the DRA. Nitrone spin-traps have been successfully used in the identification of sulfur-centered radicals in small molecules and proteins.61 Therefore, these experiments also provide an indirect means to determine if other short-lived radical intermediates are produced (e.g., thiyl radical) in the reaction but do not accumulate to detectable levels. As with previous studies, reactions were initiated by rapid mixing Zn7MT-3 (225 μM) with Cu(II) (125 μM) in buffered solutions in the presence of 45 mM DMPO. Samples were also prepared by addition of DMPO after evolution of the reaction for comparison. However, in all instances, no DMPO-radicals were observed by EPR spectroscopy (Figure S10), further suggesting that the copper-coupling might contribute to the protection and stability of the DRA.

Contrary to what was observed in the reaction with MT-3, no stable and long-lived radicals were detected by EPR upon mixing and freeze-quenching the reaction products when the reaction between GSH and Cu(II) was performed (Figure S6c), in agreement with the electronic absorption and stopped-flow analysis. Thus, while a rich redox chemistry is taking place between the sulfurs of the Cys side chains and Cu(II), the properties in the Cu(I)-thiolate cluster formation in MT-3 are unique and not shared by GSH.

Collectively, stopped-flow UV–vis, low-temperature luminescence, Raman spectroscopy, and RFQ EPR spectroscopy support a mechanism for the assembly of a redox-inert Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster in MT-3 which proceeds through a DRA-based mechanism (Figure 6). Cu(II) is reduced to Cu(I) via a controlled electron-transfer process that potentially directly generates stabilized copper-coupled disulfide radical anion intermediates with no other transient radicals detected in the process. This long-lived species is unprecedented in protein-based copper cluster assembly and may explain the redox-inert properties of Cu(I)4-cluster in MT-3 and its role in controlling abnormal Cu(II)-protein interaction in the CNS.

Figure 6.

Model for the reaction between Zn7MT-3 and Cu(II) involving the formation of Cu-coupled disulfide radical anions. (a) Proposed Cu(II) reduction/Cu(I) binding to MT-3 via a long-lived disulfide radical anion-based mechanism. The scheme represents the redox reaction pathway for Cu(II)/Cu(I) and thiolate/disulfide couples and is adapted from Figure S1 (scheme 3) to highlight the existence of a novel Cu-coupled disulfide radical anion in the cluster assembly process revealed in this work. (b) Schematic representing the structure of the initial β-domain Zn(II)3Cys9 cluster and a model of the resulting Cu(I)4Cys5 cluster product obtained via metal exchange and Cu(II) reductions. The model of the Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster is derived from spectroscopic data, as no atomic-resolution structural data are currently available.

CONCLUSION

Thiolate ligands possess a rich redox chemistry in solution, particularly in the presence of redox active metals (such as copper and iron), molecular oxygen, or ROS. Thiyl radicals, disulfide radical anions, and persulfide (perthiyl) radical intermediates have been identified and characterized in a number of biologically relevant small molecules (e.g., cysteine and glutathione) and proteins, including MTs.32,34,62–67 Sulfur radical species are typically transient, short-lived, and rapidly inactivated, and their reactivity often results in detrimental oxidative processes, disulfide-bond formation, and metal release from metalloproteins, in particular in proteins containing Cu(I)-thiolate clusters.16 Uncontrolled reactivity resulting in metal-cluster collapse and/or formation of reactive sulfur species is highly detrimental in biological processes which lead to metal- and radical-mediated cellular toxicity.16,68 Among sulfur-centered radical species, thiyl radicals were proposed to be generated and stabilized in the yeast Cu(I)6-MT protein matrix compared to other biologically relevant thiols.42,43,69 In these studies, radicals were formed upon reaction of MT thiolates with hydroxyl radical/superoxide generated by UV-irradiation of Cu(I)6-MT solutions or frozen lyophilized samples. The possibility of metal-dependent radical stabilization was postulated.42,43,69 Despite this, no direct coupling between the metal and the sulfur center radical was demonstrated nor the putative role in radical stabilization. Our investigation reveals that the process of cluster assembly in Cu(I)4Zn(II)4MT-3 possesses peculiar kinetics and mechanism that involves the formation of long-lived, copper-stabilized and redox-inert disulfide radical anion species in solution that appears to not be shared by other key biological copper-scavenging biomolecules. These metal-coupled disulfide radical anion intermediates, which are unreactive with molecular oxygen and spin trapping molecules, are unprecedented in “buffering/storage” metalloproteins that form Cu(I)-thiolate clusters. The work provides molecular insights into an elegant stepwise mechanism that controls metal exchange in MT-3 through formation of protected radical intermediates and leads to the formation of a unique redox-stable Cu(I)4-thiolate cluster core. This process substantiates the central protective role of MT-3 against the deleterious chemistry of the Cu(II)/Cu(I) redox pair and their aberrant binding to proteins in the CNS.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Gassensmith and Dr. Ahn laboratories at UT Dallas (Fabian Castro, Tristan Smith, and Kara Kassees) for help with sample lyophilization. We thank Dr. Christoph Fahrni and Dr. Peter Faller for discussion about the content of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Robert A. Welch Foundation (AT-1935-20170325 and AT-2073-20210327 to G.M) and the National Institutes of Health, Institute of General Medical Sciences (R35GM128704 to G.M. and 2 R15 GM117511-01 to B.S.P.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CC

cluster centered

- CNS

central nervous system

- CT

charge transfer

- DMPO

5,5-dimethyl-pyrroline N-oxide

- DRA

disulfide radical anion

- GSH

glutathione

- LMCT

ligand-to-metal charge transfer

- MTs

metallothioneins

- MT-3

metallothionein-3

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.1c03984.

Experimental methods and supplementary figures (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.1c03984

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Jenifer S. Calvo, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080, United States.

Rhiza Lyne E. Villones, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080, United States.

Nicholas J. York, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35401, United States.

Ewelina Stefaniak, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 02-106 Warsaw, Poland; Present Address: National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Molecular Sciences Research Hub, White City Campus, London, W12 0BZ, United Kingdom.

Grace E. Hamilton, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080, United States

Allison L. Stelling, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080, United States.

Wojciech Bal, Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Sciences, 02-106 Warsaw, Poland.

Brad S. Pierce, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35401, United States.

Gabriele Meloni, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, The University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75080, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Festa RA; Thiele DJ Copper: an essential metal in biology. Curr. Biol 2011, 21 (21), R877–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Collin F Chemical Basis of Reactive Oxygen Species Reactivity and Involvement in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20 (10), 2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rae TD; Schmidt PJ; Pufahl RA; Culotta VC; O’Halloran TV Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science 1999, 284 (5415), 805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Boal AK; Rosenzweig AC Structural biology of copper trafficking. Chem. Rev 2009, 109 (10), 4760–4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Calvo J; Jung H; Meloni G Copper metallothioneins. IUBMB Life 2017, 69 (4), 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Morgan MT; Nguyen LAH; Hancock HL; Fahrni CJ Glutathione limits aquacopper(I) to sub-femtomolar concentrations through cooperative assembly of a tetranuclear cluster. J. Biol. Chem 2017, 292 (52), 21558–21567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pushie MJ; Zhang L; Pickering IJ; George GN The fictile coordination chemistry of cuprous-thiolate sites in copper chaperones. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg 2012, 1817 (6), 938–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Baslé A; Platsaki S; Dennison C Visualizing Biological Copper Storage: The Importance of Thiolate-Coordinated Tetranuclear Clusters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56 (30), 8697–8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Scheller JS; Irvine GW; Stillman MJ Unravelling the mechanistic details of metal binding to mammalian metallothioneins from stoichiometric, kinetic, and binding affinity data. Dalton Trans 2018, 47 (11), 3613–3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vašák M; Meloni G Chemistry and biology of mammalian metallothioneins. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2011, 16 (7), 1067–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kråżel A; Maret W The Functions of Metamorphic Metallothioneins in Zinc and Copper Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18 (6), 1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Calvo JS; Lopez VM; Meloni G Non-coordinative metal selectivity bias in human metallothioneins metal-thiolate clusters. Metallomics 2018, 10 (12), 1777–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Scheller JS; Irvine GW; Wong DL; Hartwig A; Stillman MJ Stepwise copper(i) binding to metallothionein: a mixed cooperative and non-cooperative mechanism for all 20 copper ions. Metallomics 2017, 9 (5), 447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Pountney DL; Schauwecker I; Zarn J; Vašák M Formation of mammalian Cu8-metallothionein in vitro: evidence for the existence of two Cu(I)4-thiolate clusters. Biochemistry 1994, 33 (32), 9699–9705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Roschitzki B; Vašák M A distinct Cu4-thiolate cluster of human metallothionein-3 is located in the N-terminal domain. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2002, 7 (6), 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Meloni G; Faller P; Vašák M Redox silencing of copper in metal-linked neurodegenerative disorders: reaction of Zn7metallothionein-3 with Cu2+ ions. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282 (22), 16068–16078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Vašák M; Meloni G Mammalian Metallothionein-3: New Functional and Structural Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2017, 18 (6), 1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Uchida Y; Takio K; Titani K; Ihara Y; Tomonaga M The growth inhibitory factor that is deficient in the Alzheimer’s disease brain is a 68 amino acid metallothionein-like protein. Neuron 1991, 7 (2), 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Bogumil R; Faller P; Pountney DL; Vašák M Evidence for Cu(I) clusters and Zn(II) clusters in neuronal growth-inhibitory factor isolated from bovine brain. Eur. J. Biochem 1996, 238 (3), 698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Meloni G; Sonois V; Delaine T; Guilloreau L; Gillet A; Teissié J; Faller P; Vašák M Metal swap between Zn7-metallothionein-3 and amyloid—Cu protects against amyloid– toxicity. Nat. Chem. Biol 2008, 4 (6), 366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Meloni G; Vašák M Redox activity of alpha-synuclein-Cu is silenced by Zn7-metallothionein-3. Free Radical Biol. Med 2011, 50 (11), 1471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Meloni G; Crameri A; Fritz G; Davies P; Brown DR; Kroneck PM; Vašák M The catalytic redox activity of prion protein-Cu(II) is controlled by metal exchange with the Zn(II)-thiolate clusters of Zn7-metallothionein-3. ChemBioChem 2012, 13 (9), 1261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Calvo JS; Mulpuri NV; Dao A; Qazi NK; Meloni G Membrane insertion exacerbates the alpha-Synuclein-Cu(II) dopamine oxidase activity: Metallothionein-3 targets and silences all alpha-synuclein-Cu(II) complexes. Free Radical Biol. Med 2020, 158, 149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Atrián-Blasco E; Santoro A; Pountney DL; Meloni G; Hureau C; Faller P Chemistry of mammalian metallothioneins and their interaction with amyloidogenic peptides and proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46 (24), 7683–7693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Faller P; Hasler DW; Zerbe O; Klauser S; Winge DR; Vašák M Evidence for a dynamic structure of human neuronal growth inhibitory factor and for major rearrangements of its metal-thiolate clusters. Biochemistry 1999, 38 (31), 10158–10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Vašák M Metal removal and substitution in vertebrate and invertebrate metallothioneins. Methods Enzymol 1991, 205, 452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Pedersen AO; Jacobsen J Reactivity of the thiol group in human and bovine albumin at pH 3–9, as measured by exchange with 2,2′-dithiodipyridine. Eur. J. Biochem 1980, 106 (1), 291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Meloni G; Knipp M; Vašák M Detection of neuronal growth inhibitory factor (metallothionein-3) in polyacrylamide gels and by Western blot analysis. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2005, 64 (1), 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Abragam A; Bleaney B Electron Paramagnetic Resonance of Transition Ions (International Series of Monographs on Physics); Clarendon Press: Oxford, 1970; p 912. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Petasis DT; Hendrich MP Quantitative Interpretation of Multifrequency Multimode EPR Spectra of Metal Containing Proteins, Enzymes, and Biomimetic Complexes. In Methods in Enzymology; Qin PZ, Warncke K, Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, 2015; Vol. 563, pp 171–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Weil JA; Bolton JR; Wertz JE Electron Paramagnetic Resonance: Elementary Theory and Practial Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lawrence CC; Bennati M; Obias HV; Bar G; Griffin RG; Stubbe J High-field EPR detection of a disulfide radical anion in the reduction of cytidine 5′-diphosphate by the E441Q R1 mutant of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96 (16), 8979–8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hoffman MZ; Hayon E One-electron reduction of the disulfide linkage in aqueous solution. Formation, protonation, and decay kinetics of the RSSR- radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1972, 94, 7950–7957. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fang XW; Wu JL; Wei GS; Schuchmann HP; Vonsonntag C Generation and Reactions of the Disulfide Radical-Anion Derived from Metallothionein - a Pulse Radiolytic-Study. Int. J. Radiat. Biol 1995, 68 (4), 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Solomon EI Spectroscopic methods in bioinorganic chemistry: blue to green to red copper sites. Inorg. Chem 2006, 45 (20), 8012–8025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Gray HB; Coyle CL; Dooley DM; Grunthaner PJ; Hare JW; Holwerda RA; McArdle JV; McMillin DR; Rawlings J; Rosenberg RC; Sailasutá N; Solomon EI; Stephens PJ; Wherland S; Wurzbach JA, Structure and Electron Transfer Reactions of Blue Copper Proteins. Bioinorganic Chemistry II. Advances in Chemistry; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1977; No.162, pp 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gray HB; Malmström BG On the Relationship between Protein-Forced Ligand Fields and the Properties of Blue Copper Centers. Comments Inorg. Chem 1983, 2 (5), 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Stibrany RT; Fikar R; Brader M; Potenza MN; Potenza JA; Schugar HJ Charge-transfer spectra of structurally characterized mixed-valence thiolate-bridged Cu(I)/Cu(II) cluster complexes. Inorg. Chem 2002, 41 (20), 5203–5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Mandal S; Das G; Singh R; Shukla R; Bharadwaj PK Synthesis and studies of Cu(II)-thiolato complexes: bioinorganic perspectives. Coord. Chem. Rev 1997, 160, 191–235. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Leu A; Armstrong DA Thiyl Radical Oxidation of Cu(I): Formation and Spectra of Oxidized Copper Thiolates. J. Phys. Chem 1986, 90, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hoffman MZ; Hayon E Pulse radiolysis study of sulfhydryl compounds in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem 1973, 77, 990–996. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Sievers C; Deters D; Hartmann HJ; Weser U Stable thiyl radicals in dried yeast Cu(I)6-thionein. J. Inorg. Biochem 1996, 62 (3), 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hartmann HJ; Sievers C; Weser U Thiyl radicals in biochemically important thiols in the presence of metal ions. Metal Ions in Biological Systems; Routledge: England, 1999; Vol. 36, pp 389–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Torreggiani A; Tinti A Raman spectroscopy a promising technique for investigations of metallothioneins. Metallomics 2010, 2 (4), 246–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Zhu G; Zhu X; Fan Q; Wan X Raman spectra of amino acids and their aqueous solutions. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2011, 78 (3), 1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Wilbrandt R; Jensen NH; Pagsberg P; Sillesen AH; Hansen KB; Hester RE Resonance Raman spectrum of the transient (SCN)−2 free radical anion. Chem. Phys. Lett 1979, 60, 315–319. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Ford PC; Vogler A Photochemical and photophysical properties of tetranuclear and hexanuclear clusters of metals with d10 and s2 electronic configurations. Acc. Chem. Res 1993, 26, 220–226. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Schafer FQ; Buettner GR Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radical Biol. Med 2001, 30 (11), 1191–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Morgan MT; Bourassa D; Harankhedkar S; McCallum AM; Zlatic SA; Calvo JS; Meloni G; Faundez V; Fahrni CJ Ratiometric two-photon microscopy reveals attomolar copper buffering in normal and Menkes mutant cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2019, 116 (25), 12167–12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Stefaniak E; Plonka D; Szczerba P; Wezynfeld NE; Bal W Copper Transporters? Glutathione Reactivity of Products of Cu-Abeta Digestion by Neprilysin. Inorg. Chem 2020, 59 (7), 4186–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wei Y; Mathies G; Yokoyama K; Chen J; Griffin RG; Stubbe J A Chemically Competent Thiosulfuranyl Radical on the Escherichia coli Class III Ribonucleotide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136 (25), 9001–9013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Bonini MG; Augusto O Carbon Dioxide Stimulates the Production of Thiyl, Sulfinyl, and Disulfide Radical Anion from Thiol Oxidation by Peroxynitrite*. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276 (13), 9749–9754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Mottley C; Mason RP Sulfur-centered Radical Formation from the Antioxidant Dihydrolipoic Acid*. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276 (46), 42677–42683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Adhikary A; Kumar A; Palmer BJ; Todd AD; Sevilla MD Formation of S-Cl Phosphorothioate Adduct Radicals in dsDNA S-Oligomers: Hole Transfer to Guanine vs Disulfide Anion Radical Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135 (34), 12827–12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Akasaka K Paramagnetic Resonance in L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Irradiated at 77k. J. Chem. Phys 1965, 43, 1182–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Engstrom M; Vahtras O; Agren H MCSCF and DFT calculations of EPR parameters of sulfur centered radicals. Chem. Phys. Lett 2000, 328, 483–491. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Gerfen GJ; Licht S; Willems JP; Hoffman BM; Stubbe J Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Investigations of a Kinetically Competent Intermediate Formed in Ribonucleotide Reduction: Evidence for a Thiyl Radical-Cob(II)alamin Interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118 (35), 8192–8197. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Nelson DJ; Petersen RL; Symons MCR The structure of intermediates formed in the radiolysis of thiols. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1977, 2, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Budzinski EE; Box HC The oxidation and reduction of organic compounds by ionizing radiation: L-penicillamine hydrochloride. J. Phys. Chem 1971, 75 (18), 2564–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Kou WWH; Box C Primary radiation products in cysteine hydrochloride. J. Chem. Phys 1976, 64, 3060–3062. [Google Scholar]

- (61).Kalyanaraman B; Karoui H; Singh RJ; Felix CC Detection of thiyl radical adducts formed during hydroxyl radical- and peroxynitrite-mediated oxidation of thiols–a high resolution ESR spin-trapping study at Q-band (35 GHz). Anal. Biochem 1996, 241 (1), 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Kolberg M; Bleifuss G; Gräslund A; Sjöberg BM; Lubitz W; Lendzian F; Lassmann G Protein thiyl radicals directly observed by EPR spectroscopy. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2002, 403 (1), 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kolberg M; Bleifuss G; Sjöberg BM; Gräslund A; Lubitz W; Lendzian F; Lassmann G Generation and electron para-magnetic resonance spin trapping detection of thiyl radicals in model proteins and in the R1 subunit of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2002, 397 (1), 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Covès J; Le Hir de Fallois L; Le Pape L; Décout JL; Fontecave M Inactivation of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase by 2′-deoxy-2′-mercaptouridine 5′-diphosphate. Electron paramagnetic resonance evidence for a transient protein perthiyl radical. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (26), 8595–8602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Parast CV; Wong KK; Kozarich JW; Peisach J; Magliozzo RS Electron paramagnetic resonance evidence for a cysteine-based radical in pyruvate formate-lyase inactivated with mercaptopyruvate. Biochemistry 1995, 34 (17), 5712–5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Hadley JH Jr.; Gordy W Nuclear coupling of 33S and the nature of free radicals in irradiated crystals of cystine dihydrochloride: Part II, charged radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1974, 71 (11), 4409–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]