Summary

Background

Operational tolerance is the holy grail in solid organ transplantation. Previous reports showed that the urinary compartment of operationally tolerant recipients harbor a specific and unique profile. We hypothesized that spontaneous tolerant kidney transplanted recipients (KTR) would have a specific urinary metabolomic profile associated to operational tolerance.

Methods

We performed metabolomic profiling on urine samples from healthy volunteers, stable KTR under standard and minimal immunosuppression and spontaneous tolerant KTR using liquid chromatography in tandem with mass spectrometry. Supervised and unsupervised multivariate computational analyses were used to highlight urinary metabolomic profile and metabolite identification thanks to workflow4metabolomic platform.

Findings

The urinary metabolome was composed of approximately 2700 metabolites. Raw unsupervised clustering allowed us to separate healthy volunteers and tolerant KTR from others. We confirmed by two methods a specific urinary metabolomic signature in tolerant KTR mainly driven by kynurenic acid independent of immunosuppressive drugs, serum creatinine and gender.

Interpretation

Kynurenic acid and tryptamine enrichment allowed the identification of putative pathways and metabolites associated with operational tolerance like IDO, GRP35 and AhR and indole alkaloids.

Funding

This study was supported by the ANR, IRSRPL and CHU de Nantes.

Keywords: Metabolomic, Urine, Operational tolerance, Kidney transplantation, Tryptophan, Kynurenic acid

Abbreviations: ABMR, antibody mediated rejection; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AUC, area under the curve; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CNI, calcineurine inhibitors; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; DSA, donor specific antibodies; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESI +/-, electrospray ionozation positive or negative; FDR, false discovery rate; GPR, G-coupled protein receptor; HCST, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; HILIC, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography; HV, healthy volunteers; iDDA, integrative data driven acquisition; IDO, indole 2,3-diamine oxygenase; KTR, kidney transplant recipients; KTx, kidney transplantation; MIS, minimally immuno suppressed patients; MS/MS, ultra-high-resolution mass spectometry; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; nonTOL, patients without out tolerance excluding scABMR; OCS, oral cortico steroids; PBMC, peripherial blood mononuclear cells; PC, principal component; PCA, principal component analysis; ROCC, reciever opertating characteristic curve; RP, reversed phase; RT, retention time; scABMR, subclinical anti-body mediated rejection; scABMR, subclinical antibody mediated rejection; SOT, spontaneous operational tolerance; STA, stable patient; TCMR, T-cell mediated rejection; TLRX, toll like receptor n°X; TOL, tolerant patients; UHPLC/MS, ultrahigh performance liquide chromatography in tandem with mass spectometry

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Spontaneous operational tolerance in kidney transplantation defined as a long-term and functional graft without any immunosuppressive drug intake is a rare state although it is more frequent than induced tolerance thanks to combined haplo-identical hematopoietic stem cell and kidney transplantation. It is characterized by a specific peripheral tolerance to the graft both in T and B cell compartments we previously described. Though precise mechanisms at play remain undetermined. Urine is a human body fluid that is easily accessible and directly produced by kidney, thus potentially reflecting homeostatic or pathologic mechanisms in the kidney tissue. In the field of kidney transplantation, several studies have shown that factors identified by targeted or untargeted metabolomic studies in the urine of kidney transplanted recipients were associated with allograft rejection. To date, no metabolomic signature of spontaneous operational tolerance in kidney transplantation have been described to our knowledge.

Added value of this study

We demonstrated that spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR was associated with a specific urinary metabolomic profile enriched in tryptophan-derived metabolites such as kynurenic acid and tryptamine allowing us to characterize TOL with a high sensitivity and specificity in our cohort. This metabolomic signature is independent of serum creatinine level and immunosuppressive drugs.

Implications of all available evidence

Kynurenic acid and tryptamine enrichment allowed the identification of putative pathways and metabolites associated with spontaneous operational tolerance such as IDO, GRP35 and AhR signaling and microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites such as indole alkaloids. Further studies on larger cohorts are then needed to better model the metabolomic network. In parallel, multiomic models (metabolomic and microbiomic) on several compartments (plasma, urine and kidney graft tissue if possible) coupled with in vitro/in vivo studies are mandatory to better decipher their potential roles in spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Urine is a human body fluid that is easily accessible and directly produced by kidney, thus potentially reflecting homeostatic or pathologic mechanisms in the kidney tissue. In the field of kidney transplantation, several studies have shown that factors identified by targeted or untargeted metabolomic studies in the urine of kindey transplanted recipients (KTR) were associated with allograft rejection. In T-cell mediated rejection (TCMR), several urine metabolites related to amino acids metabolism (tryptophan, proline, methionine, tyrosine, threonine, dopamine), Krebs cycle (carnitine) or even nucleotide metabolites (guanidine acetate, uric acid, xanthine) could be identified.1, 2, 3, 4 A similar urinary profile encompassing Krebs cycle (ornithine, carnitine notably), these metabolomic signatures were strongly correlated with the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and creatinine excretion.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 These preliminary results suggest that the immunological state and kidney graft dysfunction could be monitored at locoregional level in a non-invasive fashion using targeted metabolomic.

Spontaneous operational tolerance (SOT) in kidney transplantation (KTx) defined as a long-term and functional graft without any immunosuppressive drug intake6,7 is a rare state although it is more frequent than induced tolerance thanks to haplo-identical hematopoietic stem cell (HSCT) and kidney transplantation.8 Two cohorts of patients with SOT showed specific clinical features such as being for at least 2/3 of male gender with low even null rate of rejection, no donor specific antibodies and antibiotic.9,10 Additionally, they present specific immune features such as higher systemic rate of granzyme B positive regulatory B cells11 and memory regulatory T cells12 and defective NK cells13 and Tfh cells function.14 All these immune features makes an echo to transcriptomic analysis of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) that exhibited a regulatory T cell6 and an B cell profiles.6,10 More recently, our team demonstrated that SOT was associated with a unique and specific urinary proteobacteria signature mostly in males15 suggesting that a functional interplay between this specific microbiota and KTR immunoregulatory mechanisms potentially associated with a specific metabolome at a locoregional level.

Based on this, we hypothesized that operational tolerance could be associated with a specific urinary metabolomic signature. To this aim, we performed a metabolomic profiling via ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (UHPLC/MS) in the urine of spontaneous tolerant KTR (TOL) compared with stable KTR (STA), minimally immunosuppressed KTR (MIS) and healthy volunteers (HV). We could clearly identify a specific urinary signature associated with SOT encompassing tryptophan-derived metabolites from the kynurenine pathway.

Methods

Patient selection and clinical data

Fifty‐six patients were enrolled in the study and signed informed consent forms. The study groups were defined as follows: (1) sixteen spontaneously tolerant patients (TOL) with no immunosuppression for at least 1 year as previously described6,7,9; 10 with stable kidney graft function with creatinine <150 μmol/L and proteinuria <1 g/24 h plus six TOL with higher creatinine serum and/or proteinuria (150–402 μmol/L and proteinuria 1g‐1.76g/24 h) without donor specific antibodies (DSA) which was attributed to vascular nephropathy by two-independent nephrologists. Thirteen with stable kidney graft function (creatinine <150 μmol/L and proteinuria <1 g/24 h) for at least 3 years under standard immunosuppression (calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), anti‐metabolite ± corticosteroids) matched for post-transplantation time were selected16: (2) eight had normal histology (STA) whereas (3) five patients had histology proven subclinical ABMR (scABMR), (4) Thirteen minimally immunosuppressed patients (MIS) as previously described17; ten with stable kidney graft function (creatinine <150 μmol/L and proteinuria <1 g/24 h) for at least 3 years under 1 immunosuppressive drug (anti‐metabolite or corticosteroids) plus three patients with higher serum creatinine attributed to CNI toxicity by two independent nephrologists and with stable creatinine for at least 3 years (creatinine 150–406 μmol/L and proteinuria 1g‐7.4 g/24 h), (5) Fourteen healthy volunteers (HV) matched for age at sampling (+/- 5 years) without any medical history of immunosuppressive (IS) drugs in the last 6 months and without autoimmune or inflammatory disease, urinary tract infection or kidney diseases (Table 1). All the clinical data were retrospectively extracted from the DIVAT Integralis database for kidney‐grafted patients (https://integralis.chu‐nantes.fr/Default.aspx).

Table 1.

Clinical and biological characteristics of recipient groups (TOL, MIS, STA, scABMR) and healthy volunteers. * indicates significant adjusted p-value < 0.05 and NA indicates “not applicable”.

| STA | TOL | MIS | scABMR | HV | Global p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient | ||||||

| Sex | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Women (%) | 2 (25) | 3 (19) | 2 (15) | 3 (60) | 7 (50) | 0.13 |

| Men (%) | 6 (75) | 13 (81) | 11 (85) | 2 (40) | 7 (50) | |

| Sex ratio (W/M) | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 1.5 | 1 | |

| Transplantation rank | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| 1 (%) | 7 (88) | 15 (94) | 11 (85) | 4 (80) | NA | 0.77 |

| > 1 (%) | 1 (12) | 1 (6) | 2 (15) | 1 (20) | NA | |

| Initial nephropathy | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Glomerulonephritis (%) | 4 (50) | 4 (24) | 5 (38) | 1 (20) | NA | 0.64 |

| Intersitial nephropathy (%) | 3 (37) | 6 (38) | 6 (46) | 3 (60) | NA | |

| Vascular nephropathy (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | NA | |

| Unknown (%) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (16) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (38) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Age at sampling (years) | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Median | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | 0.07 |

| Min | 36 | 36 | 41 | 46 | 26 | |

| Max | 66 | 72 | 79 | 79 | 64 | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Sampling time (months after transplantation) | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Median | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | NA | 0.15 |

| Min | 168 | 176 | 60 | 160 | NA | |

| Max | 236 | 433 | 336 | 375 | NA | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| DONOR | ||||||

| Deceased | 7 (88) | 12 (75) | 9 (69) | 5 (100) | NA | 0.6 |

| Alive | 1 (12) | 4 (25) | 4 (31) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| IMMUNOSUPPRESIVE DRUGS | ||||||

| CNI at sampling | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Yes (%) | 5 (63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 1 × 10-7 |

| No (%) | 3 (37) | 16 (100) | 13 (100) | 1 (20) | 14 (100) | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Antiproliferative at sampling | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Yes (%) | 7 (88) | 0 (0) | 9 (69) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) | 9,45 × 10-9 |

| No (%) | 1 (12) | 16 (100) | 4 (31) | 2 (40) | 14 (100) | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| mTOR inhibitors at sampling | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Yes (%) | 3 (37) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 0 | 0.003 |

| No (%) | 5 (63) | 16 (100) | 13 (100) | 4 (80) | 14 (100) | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Steroids at sampling | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Yes (%) | 1 (12) | 0 (0) | 11 (85) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 2,21 × 10-8 |

| No (%) | 7 (88) | 16 (100) | 2 (15) | 4 (80) | 14 (100) | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| IMMUNOLOGY | ||||||

| DSA at sampling | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| neg | 5 (63) | 10 (62) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | NA | 1,44 × 10-5 |

| Positive class I | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Positive class II | 3 (37) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | NA | |

| Positive class I and II | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | NA | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (38) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| ROUTINE BIOLOGY | ||||||

| Creatinin (micromol/L) | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Median | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | 1,2 × 10-4 |

| Min | 100 | 53 | 107 | 86 | 64 | |

| Max | 147 | 402 | 406 | 142 | 90 | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Proteinuria (g/d) | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Median | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | MD | 0.23 |

| Min | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | MD | |

| Max | 0.90 | 1.76 | 7.41 | 0.56 | MD | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | 14 (100) | |

| Urinary pH | n = 8 patients | n = 16 patients | n = 13 patients | n = 5 patients | n = 14 patients | |

| Median | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | Err:509 | 7.12 × 10-5 |

| Min | 5 | 5 | 5.5 | 5 | 5.5 | |

| Max | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5.5 | 7 | |

| Missing data (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Ethics statement

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the National French Ethics Committee (CPP) N°337/2002 “Characterization of operational tolerance in kidney transplanted recipients without immunosuppressive drugs.” And DIVAT (Données Informatisées et VAlidées en Transplantation) (www.divat.fr, French Research Ministry: RC12_0452, last agreement No. 13 334, No. CNIL for the cohort: 891735)). All participants enrolled in this study signed informed consent forms.

Urine samples collection

Urine samples (one sample per KTR and HV) were collected from TOL, STA, MIS and HV subjects from 2003 to 2020. Samples were collected aseptically after genital disinfection and were frozen at -80°C within 1 h of sampling.

Urine samples preparation

Urine samples were thawed on ice, homogenized and centrifuged at 4°C at 750g for 5 min. Urine pH and optic density were measured. Samples were then normalized on optic density using a refractometer (Digital Urine Specific Gravity Refractometer, 4410 (PAL-l0S), Cole-Parmer, USA) with ultrapure HPLC qualified water (Sigma–Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) and ultrafiltrate to retain molecules smaller than 10kDA (VWR, Fontenay-sous-Bois, France). Internal deuterated standards (leucine-5,5,5-d3, L-tryptophan 2,3,3 d3, acide indole-2,4,5,6,7-d5-3-acétique et acide 1,14-tétradécanedioïque-d24) were added to each sample in order to assess intra- and intersample validity. They were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) and CDN Isotopes (Québec, Canada) and prepared in ethanol at 10 ng/µl.

Urine metabolome analysis by UHPLC/MS

Normalized and 10-kDa-filtered urine samples were analyzed on ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography with high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHLPC/MS) with the same apparatus and methods described in Peng et al18 and in Narduzzi et al19 for reversed phase (RP) UHPLC/MS and Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) UHPLC/MS respectively. Tacking advantage of the MS² capacities of the hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap (Q-Exactive™) mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) QC samples (ie. pooled samples) were analyzed, in ESI positive and ESI negative modes, with three cycles of iterative Data Dependent MS².20 Samples were analyzed at random with regular QC samples injection (every 5 samples), following LC-MS metabolomics guidelines.21

Metabolomic signature process (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the workflow used to identify the metabolomic signature of operational tolerance. This figure was created by BioRender.

Data processing was performed under the Galaxy environment platform workflow4Metabolomic.org (W4M)22,23 in two steps. The first step consisted of transforming raw UHPLC/MS files into a data matrix containing all the identified ions in each sample. For this purpose, each peak of mass spectrum (= an ion) in each sample was individualized using centwave algorithm based on the centroid approximation according to their mass (m/z) and retention time (RT) (“peak picking”).22,24 Then, the same peaks (= the same ions) were aligned and gathered across samples according to their m/z and RT (“peak grouping”).22,24 After grouping, missing data (= undetected ions) for each sample were integrated again according to m/z and RT in order to detect and create a new peak if available (“peak filling”). Finally, the batch effect was assessed and corrected using QC samples as an internal standard with the loess algorithm22,25,26 and ions presenting a coefficient of variation (CV) > 30% in QC samples were filtered from the final data matrix. This step was performed on both ESI-positive and ESI-negative files which are available on online repositories. The second step consisted of individualizing a specific urinary metabolomic signature for TOL from the data matrix obtained at the former step. To this aim, a sample metadata files containing anonymous clinical and biological datas were generated. OPLS-DA multivariate analyses were performed with ions’ relative intensities and the group status (TOL, MIS, STA, scABMR and HV) as the response nominal variable in order to discriminate the most impacting ions for each tested condition which was defined by a variable importance in projection (VIP) score value > 0.8.23,26, 27, 28, 29 Metabolomic signatures were then extracted from the more impacting ions using first non-parametric univariate analysis followed by a multivariate analysis with ions’ relative intensities thanks to the Biosigner algorithm.30

Metabolites identification

To identify metabolites from the TOL urinary metabolomic signature both MS and MS² data were used. In the MS data, adduct and isotopologues were searched using CAMERA annotation package.23,31 The MS² data generated on pooled samples with iterative data dependant MS² acquisitions (iDDA)20 were processed with msPurity32 package tools included in W4M. In brief, every ion detected in the first step of “metabolomic signature process” was searched in the UHPLC/MS² files. If at least one MS² spectra was recorded for an ion then the MS2 spectra was compared to several external public databases (MassBank https://massbank.eu/MassBank/, HMDB https://hmdb.ca and GNPS https://gnps.ucsd.edu) This process allows us to annotate compounds at putative level (level 2) according to Creek and al.33 We used the same process to identify tryptophan-derived metabolites: tryptophan, serotonin, melatonin, tryptamine, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleactetic acid, indoleactetic acid, xanthurenic acid at a putative level (level 2). Then, standards for those metabolites were purchased from from Sigma–Aldrich (Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). This allowed the comparison of retention time, MS² mass spectra and identification of those compounds without a doubt in LC-MS traces (level 1) according to Creek et al.33

Statistical analysis

Univariate group comparisons were performed using nonparametric tests (Wilcoxon for 2 groups and Kruskal-Wallis for 3 or more groups). Unsupervised and supervised multivariate analyses were performed with ions’ relative intensities using PCA and (O)PLS-DA respectively. Heatmaps were generated using correlation clustering and the ward aggregation algorithm26 and interaction models were performed using N-way ANOVA under the Workflow4Metabolomics plateform.23 Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROCC) comparing TOL to nonTOL were generated using GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 (GraphPad software, California). False discovery rate correction (FDR) was applied to the p-value in case of multiple testing.34 Statistical significance was considered from alpha risk < 0.1.

Role of funding source

None of the funder had any role in the present study.

Results

Clinical and biological data of KTR and controls

We compared the clinical and biological data from the 4 groups of recipients (STA, TOL, MIS and scABMR) and from HV using ANOVA analysis for independent variables. No significant difference (adjusted p-value <0.05) was found for age at sampling, sampling time, transplantation rank, proteinuria and urinary pH among the recipient groups. No significant difference in sex ratio was observed between STA, TOL, MIS whereas scABMR and HV had a higher proportion of females without statistical significance (p-value <0.05 “ANOVA”)). Furthermore, serum creatinine was not significantly different among recipient groups whereas it was significantly lower in HV (p-value = 1,2 × 10−4 “ANOVA”) (Table 1). Of important note, our KTR groups could be considered as representative of their respective wider population since no difference were noted between the clinical and routine biological parameters of our KTR groups with those consensually used to define TOL,6,7,9 MIS7 and STA.16

The urine metabolome profile of spontaneous tolerant recipients differs from that of other recipients and healthy volunteers

After processing UHPLC/MS raw data, we obtained positive (ESI+) and negative ionization (ESI-) mode chromatograms containing 2171 ions in ESI+ and 2681 ions in ESI- with different mean intensities across the 4 recipient groups and the control group. Metabolomics profiles extended from polar to apolar metabolites following the acetonitrile gradient (Figure 2a). To further assess whether or not the urinary metabolome structure differed according to each group, we used principal component analysis (PCA) with the first three components (PC) in both ionization modes. In ESI+, we found that TOL and HV clustered together apart from STA, MIS and scABMR in the three PC projections (Figure 2a and 2b). In ESI-, HV clustered apart from recipients ‘groups in the three PCs. The four recipient groups clustered in roughly parallel planes going from TOL/MIS/STA/scABMR in the three PCs as well (Figure 2a and 2c) echoing blood transcriptomic and urine microbiota data.6,15 Altogether these results suggest a specific metabolomic signature for TOL that is distinct from other KTR and HV.

Figure 2.

Richness and structure of the urinary metabolome for each group of KTR and HV with RP UHPLC-MS method. (a) Chromatogram showing showing 2161 ions and 2681 ions with a major proportion of highly polar and polar metabolites in ESI+ and ESI- modes respectively according acetonitrile gradient and retention time (RT). (b) Structure of urinary metabolome in ESI+ assessed by principal component analysis (PCA) with the first three components for recipient groups (TOL, MIS, STA, scABMR) and healthy volunteers revealing two clusters: one grouping TOL and HV and another grouping MIS, STA and scABMR. (c) Structure of the urinary metabolome in ESI- assessed by principal component analysis (PCA) with the first three components for recipient groups (TOL, MIS, STA, scABMR) and healthy volunteers revealing an isolated cluster of HV in the three PCs and KTR clustering in roughly parallel planes from TOL/MIS/STA/scABMR.

Spontaneous tolerant recipients exhibit a urine-specific metabolomic signature mostly enriched in a tryptophan-derived metabolite: kynurenic acid

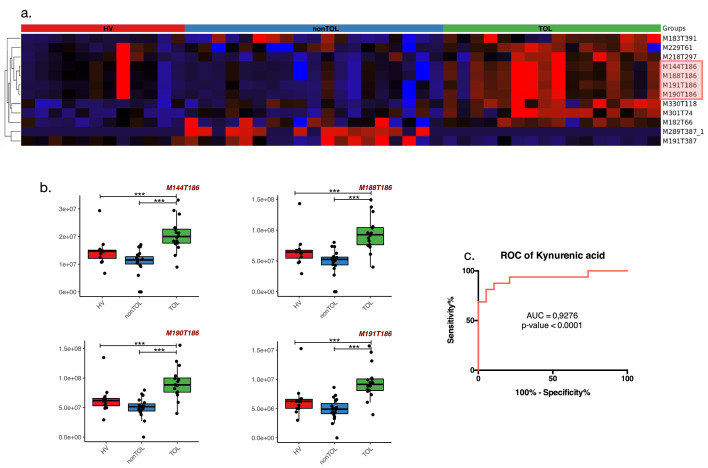

To identify a urine-specific metabolomic signature in TOL, we kept ions whose RT was greater than or equal to 60 s to avoid a high coelution rate between ions (Figure 2a). MIS and STA were grouped under non-spontaneous tolerant patients (nonTOL) since multivariate analysis (OPLS-DA) could not strictly identify impacting ions to differentiate MIS and STA as shown by the permutation diagram in both ESI+ and ESI- modes in our cohort (Supp Figure 1a) probably linked to long-term stability and time post-transplantation matching. Despite partial clustering of scAMBR in metabolomic profiling (Figure 2a and b), this group was not considered for further analysis since it was impossible to identify impacting ions to differentiate them from STA and MIS in both modes in our cohort (Supp Figure 1b) probably due to small group size and a lack of statistical power. Using that strategy, we identified twelve ions that allowed us to discriminate TOL from nonTOL and HV among which, ten were upregulated and two were downregulated in TOL patients compared to nonTOL and HV (Figure 3a). There was no interaction between those ions and clinical parameters such as gender, serum creatinine > 150µmol/L or the presence of DSA at sampling. Interestingly, two ions (M183T391 and M289T387) interacted with immunosuppressive drugs: M183T391 was significantly downregulated in the presence of CNI and mTOR inhibitors (FDR adjusted p-value = 0.03 and 0.008 respectively “N-way ANOVA”) whereas M289T387 was upregulated in the presence of CNI, antiproliferative drugs and/or oral corticosteroids (OCS) (FDR adjusted p-value = 0.0009; 0.00005; 0.0004 respectively “N-way ANOVA”) (Table 2). Among those twelve ions, eight ions were not identified since neither isotopic patterns nor matches in public databases or in our in-house bank were found. Interestingly, we identified four ions with the same RT in both modes corresponding to KYNURENIC ACID (M144T186, M188T186, M190T186, M191T186) with significantly higher intensity threshold (1,4 fold compared to HV and 1,9 compared to nonTOL) in TOL versus nonTOL (FDR adjusted p-value = 9.10−6 “Kruskal Wallis test”) and HV (FDR adjusted p-values = 0.015 “Kruskal Wallis test”). The associations of these four ions using ROCC analysis allowed us to specifically discriminate TOL from the nonTOL and HV with a high sensitivity (Se = 81%) and specificity (Sp = 95%) when considering the relative intensity threshold of 4,3 × 107 (Figure 3b and c Supp Table 1). Altogether, these results show that TOL exhibit a specific urinary metabolomic profile that is strongly driven by kynurenic acid echoing to tryptophan metabolism pathways independent of immunosuppressive drugs, eGFR and gender.

Figure 3.

Specific metabolomic signature in urine of TOL detected thanks to RP UHPLC-MS method. (a) represents the supervised clustered heatmap according to KTR (TOL, nonTOL) and HV of the twelve ions composing the specific urinary signature of TOL patients where ten are upregulated in TOL (red cluster) and two are downregulated in TOL (black to blue cluster). Among the twelve ions, four were identified as being adducts of kynurenic acid (highlighted in red) (b) as shown in boxplots (c) which allow a good discrimination of TOL compared to nonTOL patients according to the ROCC. * indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.1; ** indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.01 and ***indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.001

Table 2.

Interaction matrix of the urinary metabolomic signature of TOL detected thanks to RP UHPLC-MS method. Each column represents a tested factor among the interaction models (N-way ANOVA) for each of the twelve ions identified (in rows). A color code features either the upregulation (red) or the downregulation (blue) or the absence of change (grey) induced by the considered factor. No interaction with the tested factors was detected for kynurenic acid. There was also an inverse interaction between two ions and immunosuppressive drugs when considering TOL. The statistical significance of the interaction is represented by * indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.1; ** indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.01 and *** indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.001.

|

The urinary tryptophan metabolome of spontaneous tolerant recipients was skewed toward kynurenine pathways and tryptamine pathways

Because of the involvement of the KYNURENIC ACID and to provide an overview of the involvement of the different pathways of the tryptophan and its metabolites in TOL, nonTOL and HV, we identify in our cohort the following metabolites: tryptophan, serotonin, melatonin, tryptamine, kynurenine, kynurenic acid, anthranilic acid, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleactetic acid, indole-actetic acid and xanthurenic acid. Using RP UHPLC/MS method, we found that kynurenine, kynurenic acid and tryptamine were upregulated in TOL compared to nonTOL and HV whereas the remaining metabolites were not different between the different groups (Figure 4 and Supp Figure 3). Using HILIC UHPLC/MS method, we confirmed that kynurenic acid was significantly increased in TOL compared to HV and non TOL (FDR-adjusted p value = 0.08 and 0.01 respectively). There was no difference in kynurenine or tryptophan. We could not detect tryptamine. At last, there a significant decrease in xanthurenic acid in both TOL and non TOL compared to HV (FDR-adjusted p value = 0.02 and 0.05 respectively “Kruskal Wallis test”) (Supp Figure 4). At last, we did not highlight any interaction between the tryptophan-derived metabolites and gender, immunosuppressive drugs or the presence of DSA at sampling (Table 3). Altogether, these results suggest that kynurenine pathway (encompassing kynurenic acid) and tryptamine pathway are associated with and upregulated in spontaneous operational tolerance.

Figure 4.

Tryptophan-derived metabolites detected in the urine samples of our cohort (TOL, nonTOL and HV) and their associated metabolic pathways detected thanks to RP UHPLC-MS method. Kynurenine, kynurenic acids and tryptamine were upregulated in TOL compared to nonTOL and HV as shown in boxplots. Solid lines represent detected and identified metabolites; dashed lines represent nonidentified metabolites; grey shading indicates no change in TOL; blue-shading indicates downregulation; red shading indicates upregulation; * indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.1; ** indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.01 and *** indicates an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.001

Table 3.

Interaction matrix of the urinary tryptophan-derived metabolite in TOL detected thanks to RP UHPLC-MS method. Each column represents a tested factor among the interaction model (N-way ANOVA) for each of the twelve ions identified (in rows). A color code features either the upregulation (red) or the downregulation (blue) or the absence of change induced by the considered factor. Only tryptamine and serotonin were downregulated in the case of serum creatinine > 150µmol/L. No interaction with immunosuppressive drugs was detected. The statistical significance of the interaction is represented by * indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.1; ** indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.01 and *** indicating an FDR-adjusted p-value < 0.001.

|

Discussion

We could identify a specific urinary metabolomic profile strongly driven by the up-regulation of the tryptophan-derived metabolites; kynurenine, kynurenic acid and tryptamine independent of any immunosuppressive drugs and serum creatinine level in spontaneous tolerant patients.

Metabolomic is a recent growing field allowing to depict spatiotemporal shifts in metabolic pathways associated with homeostatic or pathologic processes. A few publications have associated metabolic changes with graft rejection in solid organ transplant immunology.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In those studies, tryptophan-derived metabolites were detected (decreased) either in blood or urine compartments suggesting that the kynurenine pathway may be involved in kidney allograft alloimmune damages. Tryptophan is decreased and correlated with eGFR in the serum of patients with chronic allograft dysfunction compared to stable KTR and HV.2 In urine, a recent study by Sigdel TK et al associated three main metabolites (increase in glycine, decrease in N-methylalanine and inulobiose) in the urine with histology proven heterogenous allo-immune dysfunctions of kidney transplants (acute rejections and IFTA).35 Interestingly, glycine has been associated with broad anti-inflammatory properties, ischemia/reperfusion and thermic shock protection.36 On the opposite, N-methylalanine was negatively correlated with active inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.37 At last, inulobiose is an exogenous metabolite derived from inuline which is not reabsorbed after glomerular filtration.38 The difference in urine inulobiose concentration during allo-immune dysfunction could be linked to a lower eGFR. Interestingly, no tryptophane derived metabolites were highlighted. Conversely, tryptophan was decreased in patients with T-cell mediated rejection (TCMR) compared with stable KTR under a standard immunosuppressive drug regimen1,4 or KTR with ABMR.5 Moreover, Duranton et al, reported on amino acid variations in the plasma and urine of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hemodialyzed patients. In particular, tryptophan and hydroxykynurenine (direct down-stream kynurenine metabolite) are modulated and associated with eGFR variations in the plasma, whereas no variation was observed in the urine of the same patients.39 Similarly, Goek et al also demonstrated that the kynurenine pathway was upregulated by eGFR impairment in the plasma but not in urine40 whereas urinary excretion of serotonin, another tryptophan-derived metabolite, was lower in KTR with eGFR impairment.3 At last, Bassi et al reported that no difference in urine tryptophan concentration according to eGFR in KTR with allograft dysfunction.2These observations suggest that (1)kynurenine pathway deviation would be associated with kidney transplant stability (either with IS drugs or SOT); (2)eGFR impairment has a different impact on the tryptophan metabolic pathways in plasma and urine, which is consistent with our data. Though, it should be born in mind that metabolomic techniques can skew the metabolomic profile.41

Back to our data, we did not observe any association between the kynurenine pathway and serum creatinine levels in our cohort whereas the serotonin pathway was downregulated by high serum creatinine levels, which is consistent with the aforementioned literature.39,40 Nor did we observe any association between the immunosuppressive regimen and tryptophan-derived metabolites (kynurenine, tryptamine or serotonin/melatonin pathways) in accordance with data in rodents and human KTR despite difference in metabolomic techniques41 Altogether, our results argue for an upregulation of the kynurenine (kynurenic acid) and the tryptamine pathways in spontaneous tolerant patients compared to HV and non-TOL suggesting their implication in spontaneous tolerance state independent of eGFR and immunosuppressive regimen.

Kynurenic acid display immunomodulatory properties mediated through GPR35 and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).42,43 GPR35 is widely expressed on myeloid cells (dendritic cells, mast cells/basophils, eosinophils and monocytes) and lymphoid cells such as natural killer T cells (NKT).44, 45, 46 In vitro studies showed that kynurenic acid-GPR35 signaling inhibited guanylate cyclase activity preventing calcium induced activation and induced β-catenin accumulation stabilizing NF-κB inhibitors.47, 48, 49 In concordance, kynurenic acid has been shown to reduce Th17 T cell polarization by reducing IL-23 production by dendritic cells after TLR4 stimulation by LPS.47 Kynurenic acid also reduces natural killer T cell activation through GPR35 signaling under inflammatory conditions,46 promoting CTLA4, PD-L1 and FOXP3 induction in naïve CD4+ T cells (i.e., regulatory T cell phenotype) cocultured with melanoma cell-lines.50 AhR is a ubiquitous receptor for aromatic endogenous and exogenous molecules acting as a transcription factor once activated and is involved in immune-regulatory mechanisms.43,51,52 Kynurenic acid was demonstrated to be a ligand of AhR with an affinity of the low micromolar range and a high stability51,53 allowing to the activation of AhR under-inflammatory conditions and inducing indole 2,3-diamine oxygenase (IDO) phosphorylation and transcription.54 IDO, the first enzyme that catalyzes the first steps in the kynurenine pathways, is well-known to promote immune-regulatory mechanisms and tolerance in solid organ transplantation. Indeed, IDO is upregulated upon endogenous or exogenous CTLA4 engagement and also in grafts infiltrated with regulatory T cells (Treg) in a mice model of kidney allograft tolerance induced by CTLA4-Ig.55 Conversely, pretransplant conditioning of the graft with adenovirus-mediated IDO gene transfer delayed T-cell mediated graft rejection.56 Recently, an in vitro study showed a role of IDO in restraining humoral allo-immune response in a AhR-independent mechanism in a one-way MLR model using PBMC from healthy donors.57

We found that the tryptophan-derived metabolites; kynurenine, kynurenic acid and tryptamine were upregulated in urine from TOL. A recent study by Piper et al in an inflammatory mice model of collagen arthritis showed that Breg generation was dependent on AhR activation.58 To our knowledge, no study has yet demonstrated any direct immunomodulatory effect of kynurenic acid on regulatory B cells, nevertheless, these data echo to immunological features such as the increase of B cells with regulatory properties,11 the Tfh defective functions13,14 and a low DSA immunization rate9 in TOL and argue for a potential role of kynurenic acid in the onset and/or maintenance of the active mechanisms such as IDO, GRP35 and AhR signaling in spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR. However, the precise mechanisms of action and main inductors remain to be determined.

Finally, we recently demonstrated that TOL had a specific urinary microbiota with an enriched fraction of Proteobacteria.15 Among those Proteobacteria, we identified Janthinobacterium lividum which is a Gram-negative soil dwelling bacteria that produces the Violacein metabolite known to have antiproliferative59 and anti‐inflammatory properties via Treg induction.60 Violacein is a bis-indole-derived alkaloid that can be synthetized from tryptophan61 and can activate AhR.62 Other microbiota indole-derived alkaloids such as pytiriazepin (Malessezia), rutaecarpine, evodiamine and dehydroevodiamine (Euodia rutaecarpa) were shown to ligate and activate AhR as well.63,64 Furthermore, microbiota-derived metabolites were recently shown to amplify AhR activation in Breg and to participate in dampening inflammation.65 With respect to our data, we demonstrated that tryptamine was upregulated in TOL without any increase either in the serotonin/melatonin pathway or in the indole-acetic acid pathway suggesting that tryptamine could fuel microbiota-derived alkaloid biosynthesis66 and would help to the onset and/or maintain of spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR. These data also echo our previous data reporting on higher levels of mTregs in TOL with higher immunosuppressive properties.12 Surprisingly, whereas the urinary microbiota was enriched in Proteobacteria mainly in males,15 no gender bias was observed in our metabolomic signature suggesting that it did not encompass microbiota-derived metabolites. Further studies comparing urine microbiota metagenome and metabolome coupled with in vitro studies on myeloid and lymphoid cells would help to better decipher the impact of microbiota on spontaneous operational tolerance and the associated immune features.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR was associated with a specific urinary metabolomic profile enriched in tryptophan-derived metabolites such as kynurenic acid and tryptamine allowing us to characterize TOL with a high sensitivity and specificity. This metabolomic signature is independent of serum creatinine level and immunosuppressive drugs. Kynurenic acid and tryptamine enrichment allowed the identification of putative pathways and metabolites associated with spontaneous operational tolerance such as IDO, GRP35 and AhR signaling and microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites such as indole alkaloids. Further studies on larger cohorts are then needed to better model the metabolomic network. In parallel, multiomic models (metabolomic and microbiomic) on several compartments (plasma, urine and kidney graft tissue if possible) coupled with in vitro/in vivo studies are mandatory to better decipher their potential roles in spontaneous operational tolerance in KTR.

Declaration of interests

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by EBioMedicine.

Acknowledgments

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in MetaboLights [https://www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/index] at [www.ebi.ac.uk/metabolights/MTBLS3105], reference number [MTBLS3105].

Contributors

LC conceptualized, created the methodology, curated data and formal analysis, wrote the original draft, reviewed, and edited. ALR, JM, AR, YG provided metabolomic formation, technical support to LC. CK managed the data. PG and MC were in charge of DIVAT-biocollection. MG conceptualized, created the methodology, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. YG and SB conceptualized, created the methodology, curated data, wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved this manuscript. LC, YG and SB curated and verified the underlying data.

Divat cohort collaborators list

Pr. Gilles BLANCHO; Dr. Julien BRANCHEREAU; Dr. Diego CANTAROVICH; Dr. Anne CESBRON; Dr. Agnès CHAPELET; Pr. Jacques DANTAL; Dr. Florent DELBOS; Dr. Clément DELTOMBE; Dr. Anne DEVIS; Dr. Lucile FIGUERES; Dr. Claire GARANDEAU; Dr. Caroline GOURRAUD-VERCEL; Pr. Maryvonne HOURMANT; Dr. Christine KANDELL; Pr. Georges KARAM; Dr. Aurélie MEURETTE; Dr. Anne MOREAU; Dr. Simon VILLE; Dr. Alexandre WALENCIK.

Acknowledgements

Luc Colas is under a Cifre contract with GlaxoSmithKline and financially supported by Institut de Recherche en Santé Respiratoire des Pays de la Loire (IRSRPL). This work was performed in the context of the IHU-Cesti project (ANR-10-IBHU-005), the DHU Oncogreffe, the ANR project PRELUD (ANR-18-CE17-0019), the ANR project BIKET (ANR-17-CE17-0008) and the ANR project KTD-innov (ANR-17-RHUS-0010) thanks to French government financial support managed by the National Research Agency. The IHU-Cesti project was also supported by Nantes Métropole and Région Pays de la Loire. The laboratory received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 754995 and from “Appel d'offre interne” of CHU de Nantes for the ICART project.

We thank the patients and their families, whose trust, support, and cooperation were essential for the collection of the data used in this study. The authors also thank Biogenouest (Western France life science and environment core facility network supported by the Conseil Régional des Pays de la Loire) for supporting the CORSAIRE-MELISA platform (Oniris), Nantes, France.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103844.

Contributor Information

Luc Colas, Email: luc.colas@univ-nantes.fr.

Anne-Lise Royer, Email: anne-lise.royer@oniris-nantes.fr.

Justine Massias, Email: justine.massias@oniris-nantes.fr.

Axel Raux, Email: axel.raux@oniris-nantes.fr.

Mélanie Chesneau, Email: melanie.chesneau@univ-nantes.fr.

Clarisse Kerleau, Email: clarisse.kerleau@chu-nantes.fr.

Pierrick Guerif, Email: pierrick.guerif@chu-nantes.fr.

Magali Giral, Email: magali.giral@chu-nantes.fr.

Yann Guitton, Email: yann.guitton@oniris-nantes.fr.

Sophie Brouard, Email: sophie.brouard@univ-nantes.fr.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kim S.Y, Kim B.K., Gwon M.R., et al. Urinary metabolomic profiling for noninvasive diagnosis of acute T cell-mediated rejection after kidney transplantation. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2019;1118–1119:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassi R., Niewczas M.A., Biancone L., et al. Metabolomic profiling in individuals with a failing kidney allograft. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landsberg A., Sharma A., Gibson I.W., Rush D., Wishart D.S., Blydt-Hansen T.D. Non-invasive staging of chronic kidney allograft damage using urine metabolomic profiling. Pediatr Transplant. 2018;22(5):e13226. doi: 10.1111/petr.13226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blydt-Hansen T.D., Sharma A., Gibson I.W., Mandal R., Wishart D.S. Urinary metabolomics for noninvasive detection of borderline and acute T cell-mediated rejection in children after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(10):2339–2349. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blydt-Hansen T.D., Sharma A., Gibson I.W., et al. Urinary metabolomics for noninvasive detection of antibody-mediated rejection in children after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101(10):2553–2561. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouard S., Mansfield E., Braud C., et al. Identification of a peripheral blood transcriptional biomarker panel associated with operational renal allograft tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(39):15448–15453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705834104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roussey-Kesler G., Giral M., Moreau A., et al. Clinical operational tolerance after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(4):736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lozano J.J., Pallier A., Martinez-Llordella M., et al. Comparison of transcriptional and blood cell-phenotypic markers between operationally tolerant liver and kidney recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(9):1916–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massart A., Pallier A., Pascual J., et al. The DESCARTES-Nantes survey of kidney transplant recipients displaying clinical operational tolerance identifies 35 new tolerant patients and 34 almost tolerant patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(6):1002–1013. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newell K.A., Asare A., Kirk A.D., et al. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Investig. 2010;120(6):1836–1847. doi: 10.1172/JCI39933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesneau M., Michel L., Dugast E., et al. Tolerant kidney transplant patients produce b cells with regulatory properties. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(10):2588–2598. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durand M., Dubois F., Dejou C., et al. Increased degradation of ATP is driven by memory regulatory T cells in kidney transplantation tolerance. Kidney Int. 2018;93(5):1154–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dugast E., David G., Oger R., et al. Broad impairment of natural killer cells from operationally tolerant kidney transplanted patients. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1721. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chenouard A., Chesneau M., Bui Nguyen L., et al. Renal operational tolerance is associated with a defect of blood tfh cells that exhibit impaired B cell help. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(6):1490–1501. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colas L., Mongodin E.F., Montassier E., et al. Unique and specific Proteobacteria diversity in urinary microbiota of tolerant kidney transplanted recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(1):145–158. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legendre C., Canaud G., Martinez F. Factors influencing long-term outcome after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2014;27(1):19–27. doi: 10.1111/tri.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouard S., Dupont A., Giral M., et al. Operationally tolerant and minimally immunosuppressed kidney recipients display strongly altered blood T-cell clonal regulation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(2):330–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng T., Royer A.L., Guitton Y., Le Bizec B., Dervilly-Pinel G. Serum-based metabolomics characterization of pigs treated with ractopamine. Metabolomics. 2017;13(6):77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narduzzi L., Royer A.-.L., Bichon E., et al. Ammonium fluoride as suitable additive for HILIC-based LC-HRMS metabolomics. Metabolites. 2019;9(12):E292. doi: 10.3390/metabo9120292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koelmel J.P., Kroeger N.M., Gill E.L., et al. Expanding lipidome coverage using LC-MS/MS data-dependent acquisition with automated exclusion list generation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017;28(5):908–917. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1608-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Want E.J., Wilson I.D., Gika H., et al. Global metabolic profiling procedures for urine using UPLC-MS. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(6):1005–1018. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giacomoni F., Le Corguillé G., Monsoor M., et al. Workflow4Metabolomics: a collaborative research infrastructure for computational metabolomics. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(9):1493–1495. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guitton Y., Tremblay-Franco M., Le Corguillé G., et al. Create, run, share, publish, and reference your LC-MS, FIA-MS, GC-MS, and NMR data analysis workflows with the Workflow4Metabolomics 3.0 Galaxy online infrastructure for metabolomics. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;93:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith C.A., Want E.J., O'Maille G., Abagyan R., Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal Chem. 2006;78(3):779–787. doi: 10.1021/ac051437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunn W.B., Broadhurst D., Begley P., et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(7):1060–1083. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thévenot E.A., Roux A., Xu Y., Ezan E., Junot C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index, and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(8):3322–3335. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galindo-Prieto B., Eriksson L., Trygg J. Variable influence on projection (VIP) for orthogonal projections to latent structures (OPLS) J Chemom. 2014;28(8):623–632. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brereton R.G., Lloyd G.R. Partial least squares discriminant analysis: taking the magic away. J. Chemom. 2014;28(4):213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wold S., Sjöström M., Eriksson L. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2001;58(2):109–130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rinaudo P., Boudah S., Junot C., Thévenot E.A. biosigner: a new method for the discovery of significant molecular signatures from omics data. Front Mol Biosci. 2016;3:26. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuhl C., Tautenhahn R., Böttcher C., Larson T.R., Neumann S. CAMERA: an integrated strategy for compound spectra extraction and annotation of liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry data sets. Anal Chem. 2012;84(1):283–289. doi: 10.1021/ac202450g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawson T.N., Weber R.J.M., Jones M.R., et al. msPurity: automated evaluation of precursor ion purity for mass spectrometry-based fragmentation in metabolomics. Anal Chem. 2017;89(4):2432–2439. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creek D.J., Dunn W.B., Fiehn O., et al. Metabolite identification: are you sure? And how do your peers gauge your confidence? Metabolomics. 2014;10(3):350–353. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol) 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sigdel T.K., Schroeder A.W., Yang J.Y.C., Sarwal R.D., Liberto J.M., Sarwal M.M. Targeted urine metabolomics for monitoring renal allograft injury and immunosuppression in pediatric patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2341. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong Z., Wheeler M.D., Li X., et al. L-Glycine: a novel antiinflammatory, immunomodulatory, and cytoprotective agent. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003;6(2):229–240. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200303000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coras R., Murillo-Saich J.D., Guma M. Circulating pro- and anti-inflammatory metabolites and its potential role in rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis. Cells. 2020;9(4):827. doi: 10.3390/cells9040827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alving A.S., Miller B.F. A practical method for the measurement of glomerular filtration rate (inulin clearance): with an evaluation of the clinical significance of this determination. Arch Intern Med. 1940;66(2):306–318. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duranton F., Lundin U., Gayrard N., et al. Plasma and urinary amino acid metabolomic profiling in patients with different levels of kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):37–45. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goek O.N., Prehn C., Sekula P., et al. Metabolites associate with kidney function decline and incident chronic kidney disease in the general population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(8):2131–2138. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khamis M.M., Adamko D.J., El-Aneed A. Mass spectrometric based approaches in urine metabolomics and biomarker discovery. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2017;36(2):115–134. doi: 10.1002/mas.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moroni F., Cozzi A., Sili M., Mannaioni G. Kynurenic acid: a metabolite with multiple actions and multiple targets in brain and periphery. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2012;119(2):133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0763-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wirthgen E., Hoeflich A., Rebl A., Günther J. Kynurenic acid: the janus-faced role of an immunomodulatory tryptophan metabolite and its link to pathological conditions. Front Immunol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01957. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5770815/ [Internet]Jan 10 [cited 2021 Mar 9];8. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y., Lu J.Y.L., Wu X., et al. G-protein-coupled receptor 35 is a target of the asthma drugs cromolyn disodium and nedocromil sodium. Pharmacology. 2010;86(1):1–5. doi: 10.1159/000314164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J., Simonavicius N., Wu X., et al. Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(31):22021–22028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fallarini S., Magliulo L., Paoletti T., de Lalla C., Lombardi G. Expression of functional GPR35 in human iNKT cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398(3):420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salimi Elizei S., Poormasjedi-Meibod M.S., Wang X., Kheirandish M., Ghahary A. Kynurenic acid downregulates IL-17/1L-23 axis in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem. 2017;431(1–2):55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11010-017-2975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walczak K., Turski W.A., Rajtar G. Kynurenic acid inhibits colon cancer proliferation in vitro: effects on signaling pathways. Amino Acids. 2014;46(10):2393–2401. doi: 10.1007/s00726-014-1790-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silva-García O., Valdez-Alarcón J.J., Baizabal-Aguirre V.M. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway controls the inflammatory response in infections caused by pathogenic bacteria. Mediat Inflamm. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/310183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rad Pour S., Morikawa H., Kiani N.A., et al. Exhaustion of CD4+ T-cells mediated by the kynurenine pathway in melanoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):12150. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48635-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiNatale B.C., Murray I.A., Schroeder J.C., et al. Kynurenic acid is a potent endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that synergistically induces interleukin-6 in the presence of inflammatory signaling. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115(1):89–97. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nguyen N.T., Nakahama T., Le D.H., Van Son L., Chu H.H., Kishimoto T. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor and kynurenine: recent advances in autoimmune disease research. Front Immunol. 2014;5:551. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murachi T., Tsukada K., Hayaishi O. Metabolic fate of kynurenic acid-C-14 intraperitoneally administered to animals. Biochemistry. 1963;2:304–308. doi: 10.1021/bi00902a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bessede A., Gargaro M., Pallotta M.T., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature. 2014;511(7508):184–190. doi: 10.1038/nature13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sucher R., Fischler K., Oberhuber R., et al. IDO and regulatory T cell support are critical for cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated Ag-4 Ig-mediated long-term solid organ allograft survival. J Immunol. 2012;188(1):37–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vavrincova-Yaghi D., Deelman L.E., Goor H., et al. Gene therapy with adenovirus-delivered indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase improves renal function and morphology following allogeneic kidney transplantation in rat. J Gene Med. 2011;13(7–8):373–381. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sounidaki M., Pissas G., Eleftheriadis T., et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase suppresses humoral alloimmunity via pathways that different to those associated with its effects on T cells. Biomed Rep. 2019;1(1):1–5. doi: 10.3892/br.2019.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piper C.J.M., Rosser E.C., Oleinika K., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor contributes to the transcriptional program of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells. Cell Rep. 2019;29(7) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.018. :121878-1892.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masuelli L., Pantanella F., La Regina G., et al. Violacein, an indole-derived purple-colored natural pigment produced by Janthinobacterium lividum, inhibits the growth of head and neck carcinoma cell lines both in vitro and in vivo. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(3):3705–3717. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verinaud L., Lopes S.C.P., Prado I.C.N., et al. Violacein treatment modulates acute and chronic inflammation through the suppression of cytokine production and induction of regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0125409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryan K.S., Drennan CL. Divergent pathways in the biosynthesis of bisindole natural products. Chem Biol. 2009;16(4):351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Maaetoft-Udsen K., Shimoda L.M.N., Frøkiær H., Turner H. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand effects in RBL2H3 cells. J Immunotoxicol. 2012;9(3):327–337. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2012.661802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Y., Yan T., Sun D., et al. Structure-activity relationships of the main bioactive constituents of euodia rutaecarpa on aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation and associated bile acid homeostasis. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46(7):1030–1040. doi: 10.1124/dmd.117.080176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mexia N., Gaitanis G., Velegraki A., Soshilov A., Denison M.S., Magiatis P. Pityriazepin and other potent AhR ligands isolated from Malassezia furfur yeast. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2015;571:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosser E.C., Piper C.J.M., Matei D.E., et al. Microbiota-derived metabolites suppress arthritis by amplifying aryl-hydrocarbon receptor activation in regulatory B cells. Cell Metab. 2020;31(4) doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.03.003. :7837-851.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao J., Xu K., Liu H., et al. Impact of the gut microbiota on intestinal immunity mediated by tryptophan metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00013. [Internet][cited 2021 Mar 12];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00013/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.