Abstract

Pediatric intussusception has been reported to be associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in the literature since the start of the pandemic in the past two years. Although this occurrence is exceptionally rare, rapid diagnosis based on recognition of gastrointestinal manifestations, clinical examination, and ultrasound confirmation can expedite appropriate care and prevent delayed complications. Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction and acute abdomen in pediatric patients. Without prompt identification, the disease process can lead to necrosis, bowel perforation, shock, and, subsequently, multiorgan failure. Intussusception has previously been associated with viral upper respiratory infections, which can cause mesenteric lymphadenopathy as a lead point to allow the bowel to telescope upon itself. The mechanism of how COVID-19 can contribute to intussusception without respiratory symptoms remains unknown. Here, we present a case of pediatric intussusception associated with COVID-19.

Keywords: pediatric intussusception, ultrasound, computed tomography, emergency department, covid-19

Introduction

Intussusception is the most common cause of acute intestinal obstruction in pediatric populations [1]. Intussusception typically affects children up to 36 months of life; however, 60% of cases occur before the age of one [2]. Adult incidence represents 5% of total cases [3,4]. Intussusception is a gastrointestinal disease described by the invagination of a proximal segment of the intestine and its mesentery (intussusceptum) into a distal segment (intussuscipiens) [5]. This blocks the passage of food and restricts blood supply to the affected area, leading to bowel obstruction and ischemia. Although any tract of the mesentery can be involved, the largest proportion of cases (85%) is due to ileocolic involvement [5].

The most common initial presenting symptom of intussusception in children and infants is colicky abdominal pain [6]. Other symptoms include nausea and vomiting (usually bilious); additionally, children may feel shortness of breath, cry, and pull their knees to their chest [7]. This combination of vague and variable symptoms, often in an infant population, can make the clinical diagnosis of intussusception challenging. The “classic triad” of intussusception includes abdominal pain, vomiting, and bloody stool; however, historically, all three features may be noted in only 21% of cases [8]. More recent studies reported that the simultaneous presence of all three symptoms is seen in 46% of presentations [8,9]. Blood in stool is a part of the triad, but it is usually seen at a late stage, as this indicates necrosis has already occurred.

Once intussusception occurs, the mesentery is pulled along the leading aspect of the invaginated segment, and the mesenteric vessels of the intussusceptum are compressed leading to venous obstruction [10]. The invaginated segment becomes engorged resulting in bleeding from the mucosa, which combined with stool resembles bloody “red currant” stool [11]. If not diagnosed and treated promptly, it can potentially be a lethal condition. Prolonged intussusception compromises perfusion to the intestine and leads to necrosis of the bowel, perforation, and shock [11].

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) can present as respiratory or non-respiratory symptoms. As discussed in Cai et al., five infants in China were hospitalized for varying concerns (e.g., severe gastrointestinal symptoms, or need for emergency surgery and/or treatment) and had non-respiratory symptoms as their first manifestation of COVID-19 infection [12]. The spectrum of symptoms and involvement of multiple organ systems may be due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (the virus which causes COVID-19 infection) affinity to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 inhibitors, which are abundantly expressed in alveolar epithelial cells, as well as gastrointestinal epithelial cells, arterial and venous endothelial cells, and arterial smooth muscle cells in all organs [13-16].

To date, there have been only 10 cases reported of intussusception in children with concomitant COVID-19 infection. Seven of the cases had no preceding respiratory symptoms, and one case developed respiratory symptoms after admission. Here, we present a rare case of pediatric intussusception following COVID-19 infection.

Case presentation

An otherwise healthy eight-month-old female with no significant medical history, born full-term, presented to the emergency department (ED) with her mother after having two bloody bowel movements along with a rash. The patient was seen in the ED two days prior where she was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and prescribed cefdinir. During the previous visit in the ED, as a general policy of public health testing everyone for COVID-19, she tested positive for COVID-19. On examination, the patient was tearful but consolable with a heart rate of 110 beats per minute, rectal temperature of 98.9°F, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation of 97% on room air.

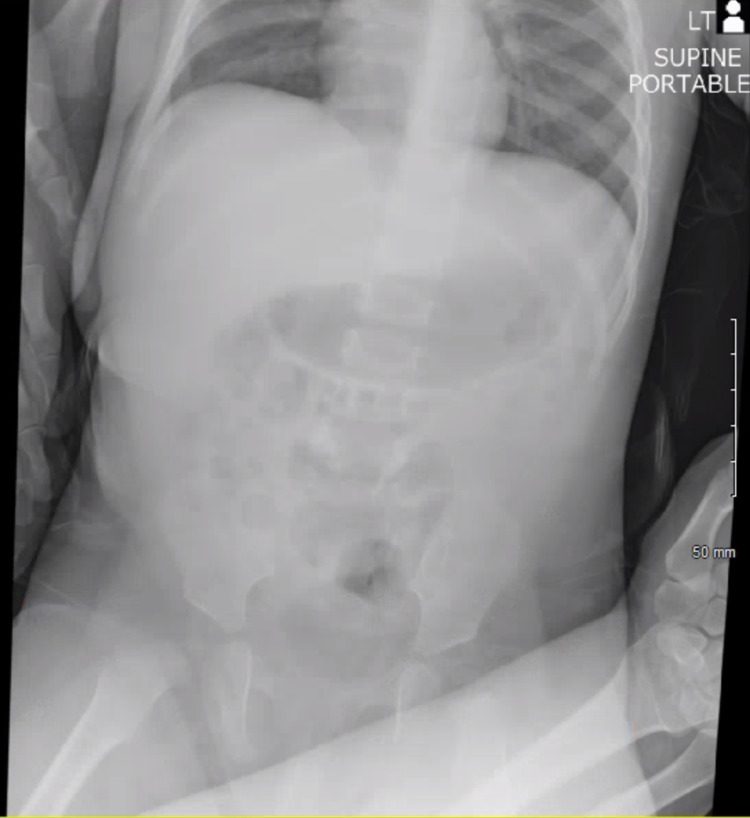

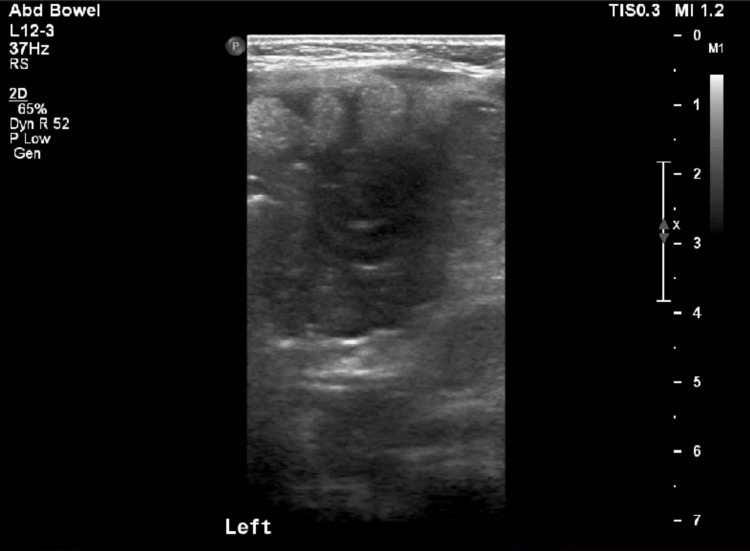

The patient’s abdomen was soft, non-distended without palpable masses. Given the reported history of bloody diarrhea, a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, abdominal X-ray, and abdominal ultrasound were ordered. Labs were significant for leukocytosis of 17,800/uL with differential showing lymphocytic predominance of 76%, signs of metabolic acidosis with bicarbonate level of 14 mEq/L, along with elevated C-reactive protein of 3.17 mg/L. No significant dilation of the small bowel, air fluid levels, or free air in the abdomen were noted on the abdominal X-ray (Figure 1). Abdominal ultrasound showed a “target sign” in the left upper quadrant (Figure 2). Given concern for intussusception, the patient was transferred to a nearby facility with higher level of capabilities and presence of pediatric gastroenterology and pediatric surgery for definitive care. A follow-up with the patient indicated an observation and bowel rest period without any surgical intervention was conducted, and after two hospital days, the patient was discharged with outpatient follow-up.

Figure 1. Abdominal X-ray reveals no evidence of ileus or obstruction.

Figure 2. Abdominal ultrasound demonstrates “target sign” suggestive of intussusception.

Discussion

The most common cause of intussusception is idiopathic, accounting for 90% of cases [7]. Other causes included altered motility, infections, and anatomical factors [7]. Infectious etiologies, specifically gastroenteritis and upper respiratory infections, can lead to mesenteric lymphadenopathy and act as a lead point; in particular, adenovirus and human herpes virus-6 have both been associated with intussusception, and rotavirus vaccination has been implicated as a risk factor [11,17].

Hypertrophy of Peyer’s patches, lymphoid follicles which line the small intestine, can also occur in common viral infections and lead to intussusception [11]. Non-infectious etiologies include Celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and neoplasia; the latter is rare in children [11]. In cases of intussusception with an identifiable etiology, a pathological lead point is a frequent cause and accounts for up to 20% of cases [18].

Several imaging modalities can assist in the diagnosis of intussusception. Plain films are useful to identify bowel obstruction and pneumoperitoneum but have low sensitivity for the detection of intussusception [19]. Ultrasound has become the modality of choice and has been shown to diagnose intussusception with 94.9% sensitivity and 99.1% specificity [20]. A positive ultrasound shows evidence of a target sign (also called doughnut sign or bull’s eye sign) which demonstrates concentric rings of mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis and represents intussusception. Computed tomography (CT) can also be used and demonstrates the appearance of bowel within the bowel, although this is sometimes an incidental finding as patients with intussusception may or may not be symptomatic [21]. CT imaging has the benefit of better characterization, including visualization of bowel edema and causative lead points, at the expense of increased cost and radiation.

The treatment of intussusception is a water-soluble contrast or air enema, given rectally, to reduce the telescoped bowel. Overall, 80% of pediatric intussusception cases are reducible with only one enema procedure, while 2.2% are not reducible after multiple attempts and require surgical intervention following enema failure [22]. When reducible, patients may be discharged home, although a more conservative approach is to observe patients in the hospital for 24 hours as the rate of recurrence is 6.5% when using a non-surgical approach [23].

A literature search revealed 10 prior cases of intussusception occurring in COVID-19-infected children that have been reported globally in the past two years. Table 1 offers a summary of all prior cases. Of note, a majority of infants (70%) presented without respiratory symptoms, and one developed respiratory symptoms following admission. Most patients were screened for COVID-19 due to hospital protocol, but one was screened due to progressively worsening respiratory status. Vomiting, cramping and intermittent abdominal pain, and red currant stool were common presenting symptoms. Infants appeared ill, showed signs of dehydration, and were described as lethargic. The majority of cases were diagnosed using ultrasound, and all cases involved infants under the age of one. Two cases ended in mortality while the remainder recovered and were doing well at follow-up.

Table 1. Summary of 10 prior cases of intussusception occurring in COVID-19-infected children.

GI: gastrointestinal; M: male; F: female; US: ultrasound; URTI: upper respiratory tract infection; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019

| Author | Gender, age; country | Contact history | Respiratory symptoms | GI symptoms | Other symptoms | Imaging | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome |

| Makrinioti et al., (2020) [24] | F, 10 months; China | None | Following admission | Vomiting, currant jelly stool | Paroxysmal crying | US | Intussusception, peritonitis, disseminated intravascular coagulation | Pneumatic reduction, surgical intervention | Deceased |

| Makrinioti et al., (2020) [24] | F, 10 months; United Kingdom | Mother with flu-like symptoms three weeks prior | Two weeks of coryzal symptoms and bilateral conjunctivitis | Bilious vomiting, currant jelly stool, lethargy | Lethargic | US | Intussusception | Pneumatic reduction, surgical intervention | Recovered |

| Rajalakshmi et al., (2020) [25] | M, 8 months; India | None | No | Non-bilious vomiting, currant jelly stools | Lethargic, signs of dehydration | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Pneumatic reduction | Recovered |

| Cai et al., (2020) [12] | F, 10 months; China | None | No | Vomiting, currant jelly stool | Paroxysmal crying, restlessness | NA | Intussusception, multiorgan failure, shock, respiratory failure | Surgical intervention | Deceased |

| Martínez-Castaño et al., (2020) [26] | M, 6 months; Spain | Relative with respiratory infection 12 days prior | No | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, currant jelly stool | US | Intussusception | Hydrostatic reduction | Recovered | |

| Moazzam et al., (2020) [27] | M, 4 months; Pakistan | None | URTI one week prior | Cramping abdominal pain, red currant stool | Inconsolable crying, drawing legs to abdomthe en | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Pneumatic reduction | Recovered |

| Athamnah et al., (2020) [28] | M, 2.5 months; Jordan, United States | Mother with flu-like symptoms | No | Vomiting, abdominal distension, cramping abdominal pain, red currant stool | Ill-appearing, fever | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Pneumatic reduction | Recovered |

| Bazuaye-Ekwuyas et al., (2020) [29] | M, 9 months; United States | None | Four days of congestion, cough, sneezing; one day of fever | Vomiting, abdominal pain, decreased oral intake, blood-streaked stool | Signs of dehydration | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Hydrostatic reduction | Recovered |

| Mercado-Martinez et al., case 1 (2021) [30] | M, 8 months; Mexico | None | No | Non-bilious vomiting, currant jelly stool | Irritable and pale | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Surgical reduction | Recovered |

| Mercado-Martinez et al., case 2 (2021) [30] | F, 7 months; Mexico | None | Rhinopharyngitis one week prior | Non-bilious vomiting, currant jelly stools | Intermittent crying, fever | X-ray | Ileocolic intussusception | Surgical reduction | Recovered |

| Noviello et al., (2021) [5] | M, 7 months; Italy | Grandmother 10 days prior who was COVID-19-positive | No | Vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, currant jelly stool | Pale, ill-appearing, signs of dehydration | US | Ileocolic intussusception | Hydrostatic reduction, surgical intervention | Recovered |

Conclusions

The number of reported cases of pediatric intussusception is increasing worldwide occurring in patients incidentally found to be COVID-19-positive. Although there are many reported gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19, the association with intussusception remains unclear. Given the severity of the disease process, intussusception should remain on the differential diagnosis for ill-appearing children with or without preceding viral upper respiratory symptoms and COVID-19 infection.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Acute intussusception in infants and children: incidence, clinical representation and management: a global perspective. [ Mar; 2022 ];https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67720/WHO_V-B_02.19_eng.pdf 2002

- 2.Intussusception: clinical presentations and imaging characteristics. Mandeville K, Chien M, Willyerd FA, Mandell G, Hostetler MA, Bulloch B. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:842–844. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318267a75e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adult intussusceptions: clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapeutic management. Maghrebi H, Makni A, Rhaiem R, et al. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;33:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adult intussusception. Azar T, Berger DL. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199708000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.COVID-19 can cause severe intussusception in infants: case report and literature review. Noviello C, Bollettini T, Mercedes R, Papparella A, Nobile S, Cobellis G. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:0–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young LL. An Online Introductory Pediatrics Textbook. Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine; 2002. Intussusception. Case based pediatrics for medical students and residents. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain S, Haydel MJ. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2017. Child intussusception. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Intussusception: evolution of current management. Bruce J, Huh YS, Cooney DR, Karp MP, Allen JE, Jewett TC Jr. https://europepmc.org/article/med/3320323. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:663–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paediatric intussusception: epidemiology and outcome. Blanch AJ, Perel SB, Acworth JP. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uncommon conditions in surgical oncology: acute abdomen caused by ileocolic intussusception. Mrak K. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5:0–9. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Intestinal intussusception: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:30–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical characteristics of 5 COVID-19 cases with non-respiratory symptoms as the first manifestation in children. Cai X, Ma Y, Li S, Chen Y, Rong Z, Li W. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:258. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-2012-7?rel=outbound. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, et al. Lancet. 2020;395:0–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. J Pathol. 2004;203:631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pulmonary angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and inflammatory lung disease. Jia H. Shock. 2016;46:239–248. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Infectious etiologies of intussusception among children & 2 years old in 4 Asian countries. Burnett E, Kabir F, Van Trang N, et al. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Systematic review shows that pathological lead points are important and frequent in intussusception and are not limited to infants. Fiegel H, Gfroerer S, Rolle U. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105:1275–1279. doi: 10.1111/apa.13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tumor spectrum of adult intussusception. Chiang JM, Lin YS. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:444–447. doi: 10.1002/jso.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound for intussusception in children presenting to the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lin-Martore M, Kornblith AE, Kohn MA, Gottlieb M. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:1008–1016. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.46241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adult intestinal intussusception: CT appearances and identification of a causative lead point. Kim YH, Blake MA, Harisinghani MG, Archer-Arroyo K, Hahn PF, Pitman MB, Mueller PR. Radiographics. 2006;26:733–744. doi: 10.1148/rg.263055100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nationwide population-based epidemiologic study on childhood intussusception in South Korea: emphasis on treatment and outcomes. Lee EH, Yang HR. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23:329–345. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2020.23.4.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Risk factors for recurrent intussusception in children: a retrospective cohort study. Guo WL, Hu ZC, Tan YL, Sheng M, Wang J. BMJ Open. 2017;7:0. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Intussusception in 2 children with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. Makrinioti H, MacDonald A, Lu X, et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2020;9:504–506. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unusual presentation of COVID-19 as intussusception. Rajalakshmi L, Satish S, Nandhini G, Ezhilarasi S. https://www.ijpp.in/Files/2020/ver2/Unusual-Presentation-of-COVID-19.pdf Indian J Pract Pediatr. 2020;22:236. [Google Scholar]

- 26.COVID-19 infection is a diagnostic challenge in infants with ileocecal intussusception. Martínez-Castaño I, Calabuig-Barbero E, Gonzálvez-Piñera J, López-Ayala JM. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:0. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Intussusception in an infant as a manifestation of COVID-19. Moazzam Z, Salim A, Ashraf A, Jehan F, Arshad M. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020;59:101533. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.COVID-19 presenting as intussusception in infants: a case report with literature review. Athamnah MN, Masade S, Hamdallah H, Banikhaled N, Shatnawi W, Elmughrabi M, Al Azzam HS. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2021;66:101779. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2021.101779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Intussusception in a child with COVID-19 in the USA. Bazuaye-Ekwuyasi EA, Camacho AC, Saenz Rios F, et al. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10140-020-01860-8. Emerg Radiol. 2020;27:761–764. doi: 10.1007/s10140-020-01860-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Intussusception and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mercado-Martínez I, Arreaga-Gutiérrez FJ, Pedraza-Peña AN. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2021;67:101808. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2021.101808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]