Abstract

The ultrarare hepatoblastoma (HB) is the most common pediatric liver cancer. HB risk is related to a few rare syndromes, and the molecular bases remain elusive for most cases. We investigated the burden of rare damaging germline variants in 30 Brazilian patients with HB and the presence of additional clinical signs. A high frequency of prematurity (20%) and birth defects (37%), especially craniofacial (17%, including craniosynostosis) and kidney (7%) anomalies, was observed. Putative pathogenic or likely pathogenic monoallelic germline variants mapped to 10 cancer predisposition genes (CPGs: APC, CHEK2, DROSHA, ERCC5, FAH, MSH2, MUTYH, RPS19, TGFBR2 and VHL) were detected in 33% of the patients, only 40% of them with a family history of cancer. These findings showed a predominance of CPGs with a known link to gastrointestinal/colorectal and renal cancer risk. A remarkable feature was an enrichment of rare damaging variants affecting different classes of DNA repair genes, particularly those known as Fanconi anemia genes. Moreover, several potentially deleterious variants mapped to genes impacting liver functions were disclosed. To our knowledge, this is the largest assessment of rare germline variants in HB patients to date, contributing to elucidate the genetic architecture of HB risk.

Keywords: hepatoblastoma, cancer predisposition, DNA repair, MSH2, VHL, ERCC5, MUTYH, CYP1A1

Introduction

The etiology of pediatric cancer is largely unknown (Saletta et al., 2015). Despite intensive research, gaps remain in our understanding of the genetic landscape of pediatric cancer susceptibility. It is assumed that germline mutations in cancer-predisposing genes (CPGs) in children and adolescents are rare events (Downing et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015; Kindler et al., 2018). However, the genetic predisposition to childhood cancer is most likely under-identified. Most investigations have focused on known CPGs and sequenced patients without parental samples, an approach that impairs a broad evaluation of the full range of genetic mechanisms underlying pediatric cancer risk, such as de novo mutations and the identification of new candidate CPGs. Recent studies of large cohorts of pediatric cancer patients have confirmed that approximately 8–18% of patients carry a germline pathogenic variant in a broad spectrum of known CPGs (Zhang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2018a; Grobner et al., 2018; Alejandro Sweet-Cordero and Biegel, 2019; Akhavanfard et al., 2020; Capasso et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2021). These studies also highlighted that isolated factors, such as tumor type and a positive family history of cancer, have low predictive power for the presence of germline CPG mutations.

HB is the most common malignant liver tumor in the pediatric population (Heck et al., 2013), although it is considered an ultrarare disease, accounting for only 1% of all pediatric tumors (Stiller et al., 2006; Czauderna and Garnier, 2018; Feng et al., 2019). In Brazil, collected data on HB are concordant with the worldwide incidence of 0.5–1.5 cases per million (Institute Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA), 2016; Aguiar et al., 2020). Most cases are diagnosed before the age of 4 years, and a male preponderance is reported (Ries et al., 1999). Nongenetic factors known to be associated with HB risk are related to very low birth weight (<1,500 g), including preterm birth (<33 weeks), small for gestational age and multiple birth pregnancies (Heck et al., 2013; Turcotte et al., 2014), and in vitro fertilization (Spector et al., 2019). A slow increase in HB incidence is observed in North America and Europe (Pateva et al., 2017), which can be partly due to the increased survival of children with low birth weight (Tanimura et al., 1998). An increased risk for HB development has been reported in association with a few specific genetic conditions, including Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (DeBaun and Tucker, 1998; Kim et al., 2017), familial adenomatous polyposis (APC gene) (Hirschman et al., 2005), Li-Fraumeni syndrome (TP53 gene) (Curia et al., 2008), Aicardi syndrome (Kamien and Gabbett, 2009), and trisomy 18 (Pereira et al., 2012).

Here, we investigated the germline exome of 30 children who developed HB, 13 of whom (43%) exhibited additional clinical signs. Our analysis provides a framework for investigating candidate genes involved in HB predisposition, as well as the tumor association with specific birth defects.

Patients and Methodology

Participants

Thirty children diagnosed with HB were enrolled in this study, which was performed at the Institute of Biosciences, University of São Paulo, Brazil. Patients were recruited from five different Brazilian institutions, most of them (n = 27) from three large pediatric cancer centers of the city of São Paulo, namely, the A. C. Camargo Cancer Center, Adolescent and Child with Cancer Support Group (GRAACC), and Pediatric Cancer Institute (ITACI). In addition, three patients were recruited from other institutions, including the Hospital da Baleia (n = 1), Hospital da Criança Conceição (n = 1), and Hospital São Lucas (n = 1). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biosciences (CAAE: 09163818.4.0000.5464), and informed consent was obtained from the parents. Patient’s clinical data were documented or recovered from medical records by the oncologists who contributed to this work. Peripheral blood samples were collected from 28 patients, and normal liver tissues were recovered from two patients. Genomic samples were also obtained from 27 available parents (19 patients).

Library Preparation and Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES)

DNA samples were extracted by phenol-chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation (Sambrook and Russell, 2006). Genomic libraries were constructed with 1 µg of genomic DNA using the following kits: Sureselect QXT V6 (Agilent Technologies), OneSeq Constitutional Research Panel (Agilent Technologies), or xGen Exome Research Panel v1.0 (IDT - Integrated DNA Technologies). The sequencing of enriched libraries was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2,500 platform using 150 base paired end reads. The sequences were aligned to the GRCh37/hg19 human genome reference with the BWA_MEM algorithm (Li, 2013). Picard tools (v.1.8, http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) were used to convert the SAM file into BAM and to mark PCR duplicates. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK 3.7) (McKenna et al., 2010) was used to realign indels, recalibrate the bases, and call (Unified Genotyper) and recalibrate variants (VQSR). Finally, multiallelic variants were split into different lines using the script split_multiallelic_rows.rb from Atlas2 (Challis et al., 2012) to obtain the VCF files used for analysis.

WES Data Analysis

SNV and indel variant annotation were conducted using VarSeq software version 1.5.0 (Golden Helix) and selected by the reading depth (>10), Phred score (>20), and alternative allele frequency (>0.35). Based on the public variant databases in ABraOM (http://abraom.ib.usp.br - (Naslavsky et al., 2020), GnomAD (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org-(Karczewski et al., 2020), and 1,000 Genomes - phase three {https://www.internationalgenome.org–(Clarke et al., 2017)}, we filtered out germline variants with frequencies below 1%, as well as those mapped to hypervariable genes (Fuentes Fajardo et al., 2012) or detected in an in-house dataset including data from 19 healthy controls.

Coding variants - Coding nonsynonymous missense and loss-of-function (LoF; frameshift, stop loss/gain, essential splice site, nonsense) variants were maintained for further analysis. In silico pathogenicity prediction for missense variants was based on six algorithms provided by the database dbNSFP (version 2.4); those predicted to be damaging to protein function by at least five different tools were prioritized. The final set of genes with rare damaging coding variants was annotated using Varelect (Stelzer et al., 2016) and HPO (Köhler et al., 2019) for ranking in association with specific phenotypes. All LoF and prioritized missense variants were validated by visual inspection of the BAM files, further annotated using the Varsome tool (Kopanos et al., 2019), and classified according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines (David Bick et al., 2015; Hampel et al., 2015).

Noncoding variants - Intronic, intergenic, 3′ and 5’ untranslated regions (UTRs), and splice region variants were annotated using SNPnexus v4 (Oscanoa et al., 2020), a web-based annotation tool for the analysis and interpretation of variants that includes databases of regulatory elements and regions, such as miRbase (ftp://mirbase.org/pub/mirbase/20/genomes/), Vista HMR (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/database/), and ENCODE (ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/grch37/release-95/mysql/regulation_mart_95/); phenotype and disease association (Genetic Association of Complex Diseases and Disorders (GAD) - http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/database/, ClinVar, and COSMIC); and noncoding scoring (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) - http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/ download, Fitness Consequences of Functional Annotation (fitCons)-http://compgen.cshl.edu/fitCons/0downloads/tracks/V1.01/i6/scores/; and Chromatin Effects of Sequence Alterations (DeepSEA)-http://deepsea.princeton.edu/help/).

Copy number variants (CNVs) - CNVs and region of homozygosity (ROH) events were derived from WES data using the software Nexus Copy Number 9 (Biodiscovery) with the SNP-FASST2 segmentation algorithm (threshold log2 Cy3/Cy5 ratio of |0.3| for gains and losses; minimum ROH length of 5 Mb). Common CNVs (Database of Genomic Variants, http://dgv.tcag.ca/dgv/app/home) were disregarded. For CNV validation, chromosome microarray analysis (CMA) was performed using the 180K platform (Agilent Technologies), as previously reported (Oliveira et al., 2018).

Results

Clinical Characterization of the HB Cohort

The clinical features of the 30 patients who developed HB are described in Table 1; the details of their tumors can be found in Supplementary Table S1. The mean age at HB diagnosis was 24 months, excluding one patient who was diagnosed at 17 years (P07). Twenty-one patients were male (70%), which agrees with the literature on sex bias in HB (Spector and Birch, 2012; Feng et al., 2019). Six patients (∼20%) presented with a family history of cancer (relatives of different degrees developed different tumors at varying ages).

TABLE 1.

Clinical description of the 30 cases of patients who developed hepatoblastoma.

| ID | Gender | Diagnosis Age | Premature | Deceased | Associated Clinical Conditions | Familial Clinical History |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | M | 42 months | N/A | ... | ... | ... |

| P02 | M | 12 months | ... | ... | Chronic hypomagnesemia and growth hormony deficiency | ... |

| P03 | F | 18 months | N/A | Yes | ... | ... |

| P04 | M | 9 months | ... | ... | ... | cancer (paternal uncle - leukemia) |

| P05 | F | 36 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P06 | M | 9 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P07 | M | 17 years | ... | Yes | Congenital hepatomegaly | ... |

| P08 | M | 54 months | ... | Yes | ... | ... |

| P09 | M | 30 months | ... | ... | Renal dysfunction (non-functional left kidney) | ... |

| P10 | F | 36 months | ... | ... | Idiopathic early telarca | ... |

| P11 | F | 1 month | ... | ... | Syndromic - congenital HB and unilateral renal agenesis | cancer (maternal grandmother - breast; paternal great-grandfather - prostate) |

| P12 | M | 19 months | … | … | … | cancer (paternal great-grandfather melanoma and maternal great-grandfather lung (smoker) |

| P13 | M | 28 months | Yes | ... | Syndromic—craniosynostosis, facial dysmorphisms, developmental delay | deceased older sisther (prematurity) |

| P14 | M | 7 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P15 | M | 7 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P16 | M | 12 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P17 | F | 58 months | ... | Yes | Syndromic—Hirschsprung disease, protruding ears, hypertelorism, nail dysplasia, developmental delay | |

| P18 | M | 17 months | Yes | ... | Syndromic—Hirschsprung disease, congenital ileal atresia, congenital bilateral cataract, sensorineural deafness, developmental delay | older sister—congenital biletaral cataract; older brother - intestinal atresia (terminal ileum) |

| P19 | M | 2 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P20 | M | 7 months | Yes | ... | Metabolic bone disease | ... |

| P21 | M | 5 months | ... | ... | Congenital HB | ... |

| P22 | M | 6 months | Yes | ... | ... | ... |

| P23 | M | 9 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P24 | F | 15 months | Yes | ... | Syndromic—craniofacial dysmorphisms, nail dysplasia, developmental delay | ... |

| P25 | M | 20 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P26 | F | 8 months | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| P27 | F | 6 years | ... | ... | ... | cancer (familial adenomatous polyposis - mother, sister, maternal uncle) |

| P28 | M | 4 months | ... | ... | Syndromic—craniosynostosis and developmental delay | ... |

| P29 | M | 17 months | … | ... | Syndromic—postnatal microcephaly, congenital malformations of the VACTERL spectrum, developmental delay | cancer (paternal cousin - central nervous system in childhood); maternal schizophrenia |

| P30 | F | 15 months | Yes | ... | Syndromic—craniofacial dysmorphisms, short neck, polysyndactyly, laryngomalacia, severe bronchodysplasia, swallowing disorder, developmental delay | cancer (several family members); paternal cousin with polysyndactyly |

F: female; M: male.

N/A- Not available; CPG, cancer predisposition gene; AD, autosomal dominant Inheritance; AR, autosomal recessive inheritance.

Sixteen patients were diagnosed with high-risk HB, classified according to the CHIC stratification (Czauderna et al., 2016; Meyers et al., 2017), and 10 presented pulmonary metastasis at diagnosis. Except for P23, who underwent surgery at diagnosis, all patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy protocols followed by tumor resection or transplantation. Eight patients received a liver transplant, and two relapsed. Four patients died from the disease.

Six out of the 30 patients were born prematurely (<37 weeks), corresponding to 20% of the group. Eleven patients had birth defects (37%), and eight of them were classified as syndromic due to the presentation of two or more congenital clinical features. Among them, five patients had craniofacial anomalies, two of whom were diagnosed with craniosynostosis (P13 and P28); two patients were born with kidney anomalies (P11 and P09); and P07, who was diagnosed with HB at an advanced age (17 years), was born with mild hepatomegaly.

P11, female, had a congenital HB diagnosed at 1 month of age; in addition, this patient was born with unilateral renal agenesis. P13, a male, was born extremely premature at 27 weeks. More details about the clinical features of both patients can be found in our previous study (Aguiar et al., 2020).

Two patients were born with Hirschsprung disease and other clinical features (P17 and P18). P17, female, was the third child of no consanguineous parents. She was born at term, and her two siblings had a normal phenotype. Abdominal volume and no evacuation were detected in the first 24 h after birth, and the diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease was made. In the clinical evaluation at 5 years old, she presented with global neuropsychomotor delay, facial dysmorphisms, clinodactyly, and nail dysplasia (hypoplastic). HB was diagnosed at the age of four and classified as an epithelial subtype with a predominance of embryonal cells, PRETEXT IV, high risk. She underwent the SIOPEL six chemotherapy protocol and died before the surgical procedure. P18, male, was the third child of a consanguineous couple; his sister was born with congenital bilateral cataracts, while his brother exhibited intestinal atresia-terminal ileus. The patient was born prematurely (28 weeks), with a syndromic phenotype composed of congenital ileal atresia, bilateral cataracts, and sensorineural deafness. His mother, who had gestational risk (cardiac defect and preeclampsia), died during his birth due to congestive heart failure. HB tumors were diagnosed at 1 year of age and classified as fetal epithelial subtype, PRETEXT II, and low risk. He underwent a chemotherapy protocol with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and ifosfamide, followed by partial hepatectomy. Currently, the patient is in post treatment follow-up, and clinical details have been previously published (Pinto et al., 2016).

P24 had facial dysmorphisms and dysplastic nails of the hands and feet, in addition to developmental delay. P29 was born with congenital malformations of the VACTERL spectrum and exhibited postnatal microcephaly and developmental delay. P30 presented craniofacial dysmorphisms, turricephaly, short neck, laryngomalacia, swallowing disorder, severe bronchodysplasia, and polysyndactyly of the right fifth digit, in addition to severe malnutrition and neuropsychomotor delay.

We performed comparisons between disease risk status and other variables (gender, premature birth, death, associated clinical conditions, familial clinical history, and age at diagnosis). When only categorical variables were considered, the non-parametric chi-square test with Yates continuity correction and Fisher exact test were applied to determine if the distribution of the data differed statistically from random expectations (null hypothesis). In cases in which continuous variables were considered, we performed the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test. Although no significant results were found, mainly due to the small size of the sample, when we compared the distribution of individuals with craniofacial or kidney defects according to risk stratification, a marginally significant result was obtained (p-value = 0.10), which can indicate a tendency of individuals with high-risk status to be more likely to present craniofacial defects, while individuals with less severe status are more prone to have kidney defects (Supplementary Figure S1).

Germline Coding and Noncoding Variants (SNVs and Indels)

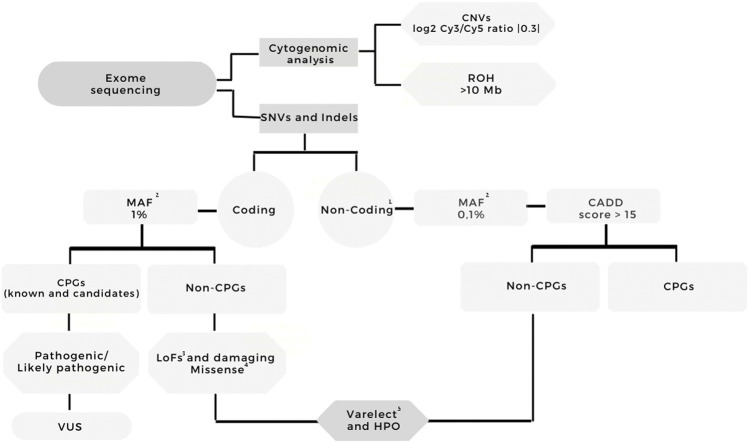

Figure 1 summarizes the analysis workflow of the WES data. The mean sequencing depth of the exomes was 92× (Supplementary Table S2 presents sequencing metrics and the type of genomic library for each sample); P03 was the only sample presenting 10x on-target coverage below 80%.

FIGURE 1.

Workflow of the exome sequencing analysis. Variants were filtered according to quality (Phred score >20, read depth >10, variant allele frequency >35%); coding and noncoding variants were separately analyzed; frequency (GnomAD, ABraOM, 1K Genomes); the effect on coding variants (frameshift, stop loss/gain, missense, splice site, nonsense); for missense variants, the prediction of pathogenicity in at least five out of six algorithms; HPO annotation (hepatoblastoma, abnormalities of the liver, and cancer). The filtered variants were visually examined using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software (http//www.broadinstitute.org/igv) to further filter out possible strand bias and homopolymeric region artifacts. All the filtered variants mapped to cancer predisposition genes were classified using the ACMG guidelines. One- Intronic variants, 3′UTR, 5′UTR; two- MAF: GnomAD, ABraOM, 1K Genomes; three- Frameshift, stop loss, stop gain, missense, splice site, nonsense variants; four- Missense variants with dbNSFP Functional Prediction of pathogenicity in at least five out of six algorithms; five- Terms used for Varelect and HPO annotation: Hepatoblastoma, abnormalities of the liver, and cancer. CNV—copy number variation, ROH - region of homozygosity, MAF—maximum allele frequency, CPG—cancer predisposition gene, VUS—variant of uncertain significance, HPO—Human Phenotype Ontology, HB—hepatoblastoma.

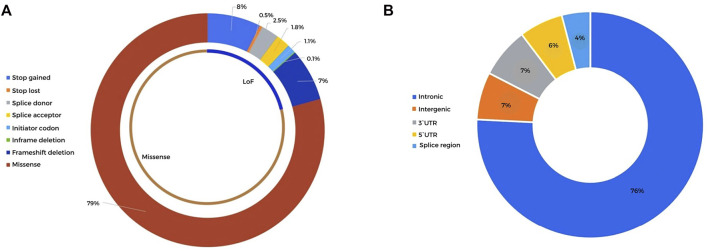

A total of 9,467 rare (population frequency <1%) germline coding nonsynonymous variants were detected in the cohort of 30 HB patients, mapping to 6,102 genes. Details of all variants can be found in Supplementary Table S3. A total of 2,107 of these rare variants, related to 1,737 different genes and including 1,671 missense mutations and 436 LoF variants (Figure 2A), met our criteria of a read depth >10, Phred score >20, and alternative allele frequency >0.35. Pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants mapped to morbid OMIM genes that could explain the syndromic phenotypes of some patients were not detected.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of the detected high-quality rare coding and noncoding variants detected in 30 HB patients (A). Sequence ontology of the rare coding variants detected after selection by the read depth (>10), Phred score (>20), alternative allele frequency (>0.35), and population frequency (<1%). A total of 2,107 variants were classified into 1,671 missense mutations and 436 LoF variants (B). Sequence ontology of the rare noncoding variants detected after selection by the read depth (>10), Phred score (>20), alternative allele frequency (>0.35), and population frequency (<0.1%). A total of 2,070 noncoding variants were distributed in intronic, intergenic, and 3′ and 5′ UTRs.

Using a list of 222 CPGs composed of 119 known CPGs (49 of them reported in OMIM), in addition to 103 candidates that were compiled by revision of recent publications (Supplementary Table S4), we investigated the presence of rare coding variants that could be related to cancer development. No homozygous or compound heterozygous pathogenic (P) or likely pathogenic (LP) variants were observed in known or candidate CPGs. Eleven heterozygous putative P/LP variants mapped to ten CPGs were detected in ten patients, comprising 33% of the group (Table 2; details provided in Supplementary Table S5); VHL variants were detected in two patients. Among the 10 patients with potentially P/LP variants in CPGs, only four presented a family history of cancer; four of them were syndromic, and three were born prematurely. One of these patients (P28) carried two variants mapped to known recessive CPGs. Eight of these variants were detected in seven autosomal-dominant CPGs (known or candidate), including an APC LoF variant (OMIM #175100 FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS one; gastrointestinal carcinomas) and six missense variants, mapped to the CHEK2 (LI-FRAUMENI SYNDROME two; colorectal, breast and prostate cancer), DROSHA (50), MSH2 (LYNCH SYNDROME I; colorectal cancer/MISMATCH REPAIR CANCER SYNDROME two; hematologic malignancy, brain tumors, and gastrointestinal tumors), RPS19 (DIAMOND-BLACKFAN ANEMIA one; osteogenic sarcoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, colon cancer), VHL (VON HIPPEL-LINDAU SYNDROME; renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, hemangioblastoma, hypernephroma, pancreatic cancer, paraganglioma, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater), and TGFBR2 (COLORECTAL CANCER, HEREDITARY NONPOLYPOSIS, TYPE 6) genes. Three variants were detected in three CPGs associated with recessive conditions: an ERCC5 LoF (XERODERMA PIGMENTOSUM, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP G; skin cancers) and missense variants mapped to FAH (TYROSINEMIA, TYPE I; hepatocellular carcinoma) and MUTYH (FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS two; colorectal carcinomas).

TABLE 2.

Description of 11 potentially pathogenic/likely pathogenic germline heterozygous variants mapped to 10 known/candidate cancer predisposition genes and detected in 10 hepatoblastoma patients.

| ID | Gene | OMIM Condition | CPG category | Genomic Coordinates (GRCh37) | HGSV Nomenclature | Frequency (GnomAD exomes/AbraOM) | Protein Change | Pathogenicity Assessment | Inheritance | Clinical Information | Literature Related to Cancer Predisposition Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P03 | TGFBR2 | #614331 COLORECTAL CANCER, HEREDITARY NONPOLYPOSIS, TYPE 6/#610168 LOEYS-DIETZ SYNDROME 2 (AD) | bona fide | 3:30733054 | NM_001024847.2:c.1742A > G | ... | p.Lys581Arg | VUS/likely pathogenic | maternal | ... |

Xu and Pasche, (2007)

Ma et al. (2012) Felicio et al. (2021) |

| P04 | DROSHA | ... | candidate | 5:31424577 | NM_013235.5:c.3218A > C | 0.000016/0 | p.Asp1073Ala | VUS/likely pathogenic | N/A | Positive familial cancer history |

Wegert et al. (2015)

Carraro et al. (2016) Felicio et al. (2021) |

| P11 | FAH | #276700 TYROSINEMIA, TYPE I (AR) | bona fide | 15:80460444 | NM_000137.2:c.506C > T | ... | p.Ser169Phe | Likely pathogenic | maternal | Positive familial cancer history; syndromic |

Zhang et al. (2015)

Carta et al. (2020) Capellini et al. (2021) |

| P13 | MSH2 | #120435 LYNCH SYNDROME I/#158320 MUIR-TORRE SYNDROME (AD); #619096 MISMATCH REPAIR CANCER SYNDROME 2 (AR) | bona fide | 2:47630464 | NM_000251.2:c.134C > A | ... | p.Ala45GLu | VUS/likely pathogenic | maternal | Premature; syndromic | Capasso et al. (2020) |

| P16 | VHL | #193300 VON HIPPEL-LINDAU SYNDROME/#171300 PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA (AD) |

bona fide | 3:10183772 | NM_000551.3:c.241C > T | 0.000218/0 | p.Pro81Ser | Likely pathogenic (modifier) | N/A | ... | Schmidt et al. (2016) |

| P21 | CHEK2 | #609265 LI-FRAUMENI SYNDROME 2/#14480 BREAST, #114500 COLORECTAL, # 176,807 PROSTATE SUSCEPTIBILITY TO CANCER | bona fide | 22:2,9091741 | NM_007194.4:c.1216C > T | 0.000060/0 | p.Arg406Cys | VUS/likely pathogenic | not maternal | Congenital tumor |

Vahteristo et al. (2002)

Bąk et al. (2014) Southey et al. (2016) |

| P22 | VHL | #193300 VON HIPPEL-LINDAU SYNDROME/#171300 PHEOCHROMOCYTOMA (AD) |

bona fide | 3:10183685 | NM_000551.3: c.154G > A | 0.000085/0 | p.Glu52Lys | VUS/likely pathogenic | maternal | Premature | Schmidt et al. (2016) |

| P27 | APC | #175100 FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS 1 (AD)/#135290 DESMOID disease, HEREDITARY (AD) | bona fide | 5:112175038 | NM_000038.6:c.3747C > A | ... | p.Cys1249* | Pathogenic | maternal | Positive familial cancer history* |

Baeg et al. (1995)

Schmidt et al. (2016) |

| P28 | ERCC5 | # 616,570 CEREBROOCULOFACIOSKELETAL SYNDROME 3 (AR)/# 278,780 XERODERMA PIGMENTOSUM, COMPLEMENTATION GROUP G (AR) | bona fide | 13:103514580 | NM_000123.3:c.1081delC | ... | p.Leu361Trpfs*18 | Likely pathogenic | not paternal | Syndromic | Fassihi et al. (2016) |

| MUTYH | #608456 FAMILIAL ADENOMATOUS POLYPOSIS 2 (AR) | bona fide | 1:45798111 | NM_001048174.1:c.656G > A | 0.000008/0 | p.Arg219GLn | VUS/likely pathogenic | paternal | Barreiro et al. (2022) | ||

| P30 | RPS19 | # 105,650 DIAMOND-BLACKFAN ANEMIA 1 (AD) | bona fide | 19:42365273 | NM_001022.3:c.164C > T | 0.000248/0 | p.Thr55Met | VUS/likely pathogenic | maternal | Positive familial cancer history; premature; syndromic | Luft, (2010) |

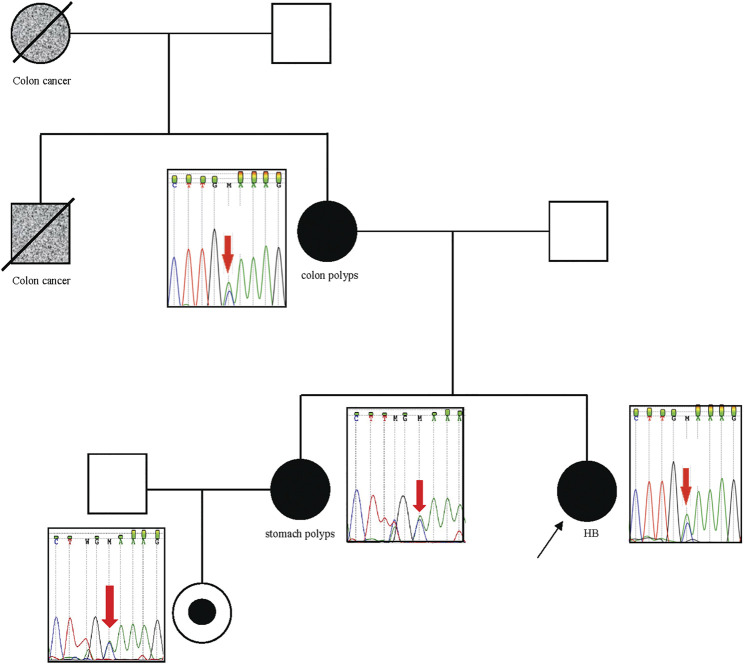

We investigated genomic data available of tumor tissues derived from three of these patients with relevant germline variants described in Table 2 (P03, P13, P21); however, additional somatic mutations in the same gene were not observed in these cases, and tumor tissue from patient P13 was no longer available to test microsatellite instability. In particular, Patient P27, who carries an APC pathogenic variant, had a strong familial cancer history, in which her mother and sister were diagnosed with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and her maternal grandmother and uncle, already dead, had colon cancer. Sanger sequencing analysis confirmed the segregation of the detected pathogenic APC variant with the cancer phenotype in this family (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

APC pathogenic variant segregates with the cancer phenotype in the family of patient P27. The patient P27 is indicated with the black arrow. P27, her mother, sister, and niece are carriers of the pathogenic p. Cys1249* variant in the APC gene, which was identified by exome sequencing in the patient, and validated by Sanger sequencing in their indicated relatives. Her mother and sister had colon polyps and stomach polyps, respectively. The maternal grandmother and uncle had colon cancer (both are dead).

In addition, 44 VUS mapped to 34 known/candidate CPGs were observed in 21 patients (70%) (Table 3), most of whom carried more than one variant. VUS mapped to the ATM, BRCA2, COL7A1, DHCR7, DOCK8, FANCs, and GLI3 genes were detected in more than one patient.

TABLE 3.

Description of 44 germline rare heterozygous variants of uncertain significance (VUS) mapped to known/candidate cancer predisposition genes detected in 21 hepatoblastoma patients.

| ID | Gene | Inheritance Pattern | CPG category | Genomic Coordinates* | HGSV Nomenclature | Variant Frequency (GnomAD) | Protein Change | ClinVar (Classification/ID) | Variant Inheritance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P09 | ATM | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 11:108121787 | c.1595G > A | 0.0002 | p.Cys532Tyr | LB (3); VUS(7)/133603 | n/a |

| P29 | ATM | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 11:108198394 | c.6998C > A | 0.00009 | p.Thr2333Lys | LB (4); VUS(2)/127434 | paternal |

| P15 | BARD1 | Dominant | bona fide | 2:215645351 | c.1247T > G | ... | p.Leu416Arg | VUS/237815 | not maternal |

| P11 | BRCA2 | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 13:32912346 | c.3858_3860delAAA | 0.00009 | p.Lys1286del | B (1); LB (9); VUS(1)/37861 | not maternal |

| P12 | BRCA2 | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 13:32906711 | c.1096T > G | 0.00003 | p.Leu366Val | LB (3); VUS(4)/89040 | Paternal |

| P02 | COL7A1 | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 3:48629243 | c.1370C > T | 0.00003 | p.Pro457Leu | VUS/345877 | maternal |

| P28 | COL7A1 | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 3:48628112 | c.1774C > T | 0.00004 | p.Arg592Cys | ... | maternal |

| P02 | DHCR7 | Recessive | candidate | 11:71152316 | c.583G > A | 0.00002 | p.Ala195Thr | ... | maternal |

| P09 | DHCR7 | Recessive | candidate | 11:71146861 | c.988G > A | 0.0004 | p.Val330Met | VUS/420113 | n/a |

| P26 | DHCR7 | Recessive | candidate | 11:71146861 | c.988G > A | 0.0004 | p.Val330Met | VUS/420113 | maternal |

| P30 | DIS3L2 | Recessive | bona fide | 2:233201216 | c.2534A > G | ... | p.Gln845Arg | ... | maternal |

| P05 | DOCK8 | Recessive | bona fide | 9:432,299 | c.4760T > C | 0.00005 | p.Met1587Thr | VUS/835366 | maternal |

| P16 | DOCK8 | Recessive | bona fide | 9:328,086 | c.959C > T | 0.000004 | p.Thr320Met | VUS/942058 | maternal |

| P30 | DOCK8 | Recessive | bona fide | 9:336,712 | c.1416C > G | 0.00002 | p.Phe472Leu | ... | maternal |

| P13 | EP300 | Dominant | candidate | 22:41565569 | c.4235C > T | 0.00002 | p.Ala1412Val | ... | paternal |

| P17 | ERCC2 | Recessive | bona fide | 19:45868145 | c.545C > T | 0.00062 | p.Ala182Val | B (1); LB (1); VUS(1)/ | maternal |

| P26 | EXT2 | Dominant | bona fide | 11:44165865 | c1242 G > A | 0.000062 | p.Trp414* | not maternal | |

| P24 | FANCA | Recessive | bona fide | 16:89811469 | c.3524C > T | 0.00032 | p.Pro1175Leu | maternal | |

| P10 | FANCD2 | Recessive | bona fide | 3:1,0132002 | c.3710T > C | 0.000008 | p.Val1237Ala | VUS/578150 | not maternal |

| P29 | FANCD2 | Recessive | bona fide | 3:10107551 | c.2273G > C | 0.00058 | p.Cys758Ser | LB (1); VUS(2)/456351 | maternal |

| P05 | FANCG | Recessive | bona fide | 9:35076975 | c.770G > A | 0.000004 | p.Arg257His | VUS/802484 | not maternal |

| P09 | FANCM | Dominant | candidate | 14:45654489 | c.4585G > A | ... | p.Asp1529Asn | ... | n/a |

| P23 | FANCM | Dominant | candidate | 14:45644816 | c.2859A > C | ... | p.Lys953Asn | LB (1); VUS(6)/313209 | maternal |

| P29 | FAS | Dominant | bona fide | 10:90773115 | c.667A > C | 0.00009 | p.Asn223His | VUS/570775 | maternal |

| P08 | FGFR3 | Dominant | candidate | 4:1801029 | c.158G > C | 0.00002 | p.Ser53Thr | VUS/501373 | n/a |

| P16 | FH | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 1:241671977 | c.664T > A | 0.00003 | p.Ser222Thr | VUS/576908 | paternal |

| P21 | FLCN | Dominant | bona fide | 17:17129602 | c.284A > G | ... | p.Tyr95Cys | ... | maternal |

| P24 | GBA | Recessive | bona fide | 1:155206060 | c.1200G > A | 0.0003 | p.Met400Ile | ... | maternal |

| P18 | GLI3 | Dominant | candidate | 7:42187947 | c.245G > A | 0.00001 | p.Arg82Lys | ... | paternal |

| P28 | GLI3 | Dominant | candidate | 7:42187959 | c.233C > T | 0.000008 | p.Ser78Leu | ... | maternal |

| P04 | JMJD1C | Dominant | candidate | 10:64949103 | c.6395A > T | 0.001 | p.Lys2132Ile | LB/571988 | maternal |

| P23 | KDR | Dominant | candidate | 4:55963918 | c.2525G > A | ... | p.Arg842His | ... | maternal |

| P30 | MET | Dominant | bona fide | 7:116395422 | c.1715G > A | 0.000501,263 | p.Ser572Asn | B (3); LB (3)/188358 | maternal |

| P29 | MRE11 | Recessive | candidate | 11:94180501 | c.1667A > G | 0.0001 | p.Asn556Ser | LB (1); VUS(5)/142425 | maternal |

| P29 | MSH6 | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 2:48018139 | c.334A > G | ... | p.Asn112Asp | VUS/220150 | paternal |

| P04 | NDRG4 | Unknown | candidate | 16:58538132 | c.358G > A | 0.00003 | p.Val120Met | ... | not maternal |

| P22 | NYNRIN | Recessive | candidate | 14:24886448 | c.5493G > C | ... | p.Gln1831His | ... | maternal |

| P22 | PTCH1 | Dominant | bona fide | 9:98231286 | c.1997C > T | 0.00001 | p.Thr666Met | VUS/820499 | maternal |

| P23 | RECQL | Dominant | candidate | 12:21636438 | c.572C > A | ... | p.Pro191GLn | ... | paternal |

| P29 | RECQL4 | Recessive | bona fide | 8:145741407 | c.1096G > C | 0.000004 | p.Gly366Arg | VUS/239691 | paternal |

| P30 | RHBDF2 | Dominant | bona fide | 17:74475818 | c.356G > A | 0.000004 | p.Ser119Asn | ... | paternal |

| P23 | SH2B3 | Recessive | candidate | 12:111856571 | c.622G > C | ... | p.Glu208GLn | VUS/30445 | paternal |

| P22 | SLX4 | Recessive | bona fide | 16:3634797 | c.4712C > T | 0.00002 | p.Thr1571Met | ... | maternal |

| P12 | TERT | Recessive; Dominant | bona fide | 5:1293676 | c.1323_1325delGGA | 0.002 | p.Glu441del | B (1); LB (9); VUS(3)/212398 | paternal |

*Genomic coordinates given according to GRCh37.

N/A- Not available; CPG, cancer predisposition gene; B- Benign; LB, Likely benign; VUS, Variant of uncertain significance.

Thirty-two genes related to liver differentiation or function were found to be affected by rare variants (ABCB11, ABCB4, ABCC2, ABCC3, AFP, ALB, CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, CYP3A7, FAH, FOXA2, KRT7, KRT8, MET, NR1I2, ONECUT1, PAH, POU5F1, PPARG, SOX17) (Supplementary Table S6).

We also investigated whether the observed sex bias in the group could be explained by an increased burden of rare damaging variants in one of the sexes; we did not detect significant differences considering the average of rare damaging variants in male and female patients (∼66.7 and 68.1, respectively), LoF variants (∼15 variants in both groups), and rare damaging CPG variants (∼8 and 6, respectively).

A total of 2,069 noncoding variants passed our filters (read depth >10, Phred score >20, alternative allele frequency >0.35, frequency in population databases >0.1%), including intronic (76%), intergenic (7%), 3′ prime UTR (7%), 5′ prime UTR (6%), and splice region (4%) variants (Supplementary Table S7; Figure 2B). These variants were annotated using SNP Nexus (Oscanoa et al., 2020), and those with CADD scores above 15 and associated with cancer (https://geneticassociationdb.nih.gov/) were prioritized for further analyses. Table 4 details the 23 prioritized rare noncoding variants. Two variants were observed in the intronic regions of the CPGs BRAF and CREBBP, but with no evidence of a functional effect. In particular, P12 carried a de novo mutation in the 5’ UTR of the TCF7 gene, an important effector protein in the Wnt pathway; this patient also carries a paternally inherited coding TCF7 VUS (c.1060C > G).

TABLE 4.

Rare germline non-coding variants detected in HB patients which were prioritized (CADD score above 15 and association with cancer).

| ID | Gene | Genomic Coordinates* | Ref/Alt | Sequence Ontology | Variants | CADD Score | Inheritance | Co-Occurrence with Coding Variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P02 | KLF12 | 13:74518363 | T/A | intron_variant | c.34–156A > T | 15.12 | N/A | |

| P02 | PRKCH | 14:61788795 | C/T | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.-25C > T | 16.91 | not maternal | |

| P02 | BLMH | 17:28575944 | G/A | 3_prime_UTR_variant | c.*91C > T | 15.7 | N/A | |

| P02 | CARM1 | 19:11030266 | C/T | splice_region_variant | c.1021–5C > T | 15.69 | not maternal | |

| P10 | IKZF3 | 17:37949260 | C/T | intron_variant | c.164-74G > A | 15.38 | maternal | |

| P10 | PTPN1 | 20:49126913 | G/A | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.-152G > A | 17.68 | N/A | |

| P10 | SEPSECS | 4:25161856 | G/A | intron_variant | c.114 + 22C > T | 16.15 | not maternal | |

| P15 | HES7 | 17:8026335 | G/A | intron_variant | c.138 + 14C > T | 15.59 | not maternal | |

| P15 | CNGB3 | 8:87755859 | C/T | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.-4G > A | 15.68 | not maternal | |

| P18 | DLGAP1 | 18:3874312 | T/C | intron_variant | c.957 + 4800A > G | 16.45 | N/A | |

| P19 | FAM65C | 20:49206219 | T/C | splice_region_variant | c.2661+4A > G | 17.98 | not maternal | |

| P19 | BRAF# | 7:140453973 | T/A | intron_variant | c.1741 + 14A > T | 17.02 | not maternal | |

| P12 | TCF7 | 5:133451301 | C/T | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.316 + 223C > T | 15.81 | de novo | yes [TCF7 VUS (c.1060C > G)] |

| P25 | UCP3 | 11:73715453 | G/T | intron_variant | c.643 + 76C > A | 19.81 | N/A | |

| P25 | ITGA7 | 12:56094605 | C/T | intron_variant | c.670 + 78G > A | 16.72 | N/A | |

| P25 | PPP1R12A | 12:80172901 | G/C | intron_variant | c.2956–521C > G | 18.05 | N/A | |

| P25 | NIN | 14:51297660 | G/C | intron_variant | c.-76 + 64C > G | 19.02 | N/A | |

| P25 | CREBBP# | 16:3811652 | G/A | intron_variant | c.3251–2679C > T | 16.15 | N/A | |

| P25 | CDK12 | 17:37618316 | G/A | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.-9G > A | 18.03 | N/A | |

| P26 | PLK3 | 1:45269400 | C/T | intron_variant | c.1164 + 37C > T | 15.47 | not maternal | |

| P26 | SERPINI2 | 3:167184804 | A/T | intron_variant | c.508 + 39T > A | 17.66 | not maternal | |

| P26 | GFRA2 | 8:21645850 | G/C | 5_prime_UTR_variant | c.-179C > G | 18.32 | not maternal | |

| P26 | ZNF462 | 9:109692049 | A/G | intron_variant | c.5847+9A > G | 18.73 | not maternal |

#known/candidate cancer predisposition genes; *given according to GRCh37; N/A: not available.

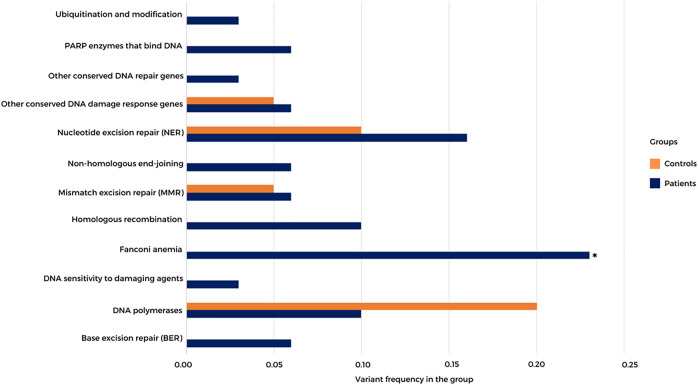

Using the exome data of HB patients and a healthy control group (n = 19, data not shown), we inspected a list of 220 DNA repair genes (distributed in 16 categories, including several bona fide CPGs; https://www.mdanderson.org/documents/Labs/Wood-Laboratory/human-dna-repair-genes.html), searching for rare LoF and missense variants with high in silico damage prediction (5 or more algorithms; (Supplementary Table S8); Figure 4 shows the frequency of rare damaging variants detected in 12 DNA repair categories in both controls and patients. Thirty-four heterozygous variants mapped to DNA repair genes were observed in 21 patients (70%), while nine heterozygous variants were detected in nine healthy controls (47%). Although not statistically significant, there was an apparent excess of damaging variants mapped to DNA repair genes in patients. Moreover, rare damaging variants affecting specific DNA repair gene categories, such as ubiquitin modification, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) enzymes that bind to DNA, nonhomologous end-joining, homologous recombination (BRCA1, EME2, SPIDR, and RAD54L), Fanconi anemia genes (BRCA2, FANCA, BRIP1, SLX4, FANCD2, and FAAP24), genes associated with DNA sensitivity to damaging agents, and base excision repair, were observed only in patients. Significant enrichment for rare damaging variants mapped to Fanconi anemia genes was detected in the group of patients (p value 0.0338; Fisher’s test).

FIGURE 4.

Frequency of high-quality rare germline coding variants mapped to DNA repair genes in HB patients and a control group. A list of 220 DNA repair genes distributed in 16 categories was analyzed; the 12 categories with variants detected in either patients or controls are represented. PARP—poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. *p value 0.0338; Fisher’s test.

Germline Copy Number Variation (CNV) and Regions of Homozygosity

Assessing germline CNVs using exome data, seven rare copy number changes were detected, four with clinical relevance, all of which were validated by CMA (Supplementary Figure S2). The encompassed genomic regions did not include CPGs or genes associated with the patients’ phenotypes (Table 5). A pathogenic Y chromosome aneuploidy was detected in P19 (Jacob syndrome 47, XYY). P21 and P28 paternally inherited 15q11.2 copy number gain and loss, respectively, which are classified as risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders, mainly global delay, and intellectual disability.

TABLE 5.

Rare germline CNVs containing coding regions and copy neutral events (>10 Mb) detected by whole-exome sequencing.

| ID | Genomic Coordinates (GRCh37) | Cytoband | Lenght (pb) | Event | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P01 | chr14:39878443-50253620 | 14q21.1q21.3 | 10375178 | ROH | N/A |

| P02 | chr12:13243647-26779469 | p13.1p11.23 | 13535823 | ROH | N/A |

| P04 | chr3:155563877-169430359 | q25.31q26.2 | 13866483 | ROH | N/A |

| chr5:82871986-93727017 | q14.3q15 | 10855032 | ROH | N/A | |

| P05 | chr3:148784725-159539084 | q24q25.33 | 10754360 | ROH | N/A |

| P16 | chr1:30815910-44569110 | p35.2p34.1 | 13753201 | ROH | N/A |

| chr1:100623391-117602935 | p21.2p13.1 | 16979545 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr4:38830037-49064655 | p14p11 | 10234619 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr5:49386907-76121142 | q11.1q13.3 | 26734236 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr7:27135316-43664239 | p15.2p13 | 16528924 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr8:30975883-43822511 | p12p11.1 | 12846629 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr8:46706294-91982327 | q11.1q21.3 | 45276034 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr11:75567951-93408344 | q13.5q21 | 17840394 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr13:77527773-113153328 | q22.3q34 | 35625556 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr16:55222478-65019075 | q12.2q21 | 9796598 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr16:69198915-89289425 | q22.1q24.3 | 20090511 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr17:1-5308028 | p13.3p13.2 | 5308028 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr17:53853305-65025445 | q22q24.2 | 11172141 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr18:1339613-12110120 | p11.32p11.21 | 10770508 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr18:60985801-78077248 | q21.33q23 | 17091448 | ROH | N/A | |

| P18 | chr1:165649300-197321158 | q24.1q31.3 | 31671859 | ROH | N/A |

| chr3:75431870-91000000 | p12.3q11.1 | 15568131 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr6:90497518-105697034 | q15q21 | 15199517 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr8:2055270-24208142 | p23.3p21.2 | 22152873 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr13:28538303-42485700 | q12.2q14.11 | 13947398 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr13:52351088-95062039 | q14.3q32.1 | 42710952 | ROH | N/A | |

| chr16:78439762-90354753 | q23.1q24.3 | 11914992 | ROH | N/A | |

| P19 | chrY:2787139-26671311 | Yp11.2q12 | 23884173 | aneuploidy | pathogenic (Jacob syndrome), de novo |

| P18 | chr14:64193920-64700120 | q23.2 | 506,201 | CN Gain | variant of uncertain significance (VUS), maternal |

| P07 | chr11:93063308-93583708 | q21 | 520,401 | CN Gain | likely benign |

| P09 | chr1:19,849,733-20154295 | p36.13 | 304,563 | CN Gain | likely benign |

| P15 | chr21:40555024-40569195 | q22.2 | 14172 | CN Loss | likely benign |

| P21 | chr15:22612422-23288771 | q11.2 | 676,350 | CN Loss | risk factor neurodevelopmental disease (https://search.clinicalgenome.org/kb/gene-dosage/region/ISCA-37448/OMIM #615656 CHROMOSOME 15q11.2 DELETION SYNDROME), paternal |

| P28 | chr15:22740164-23685606 | q11.2 | 945,443 | CN Gain | risk factor neurodevelopmental disease (https://search.clinicalgenome.org/kb/gene-dosage/region/ISCA-37448), paternal |

| P30 | chr1:39878521-39879833 | p34.3 | 1,313 | CN Gain | likely benign |

ROH: copy-neutral region of homozigozity; N/A: not applicable.

Regions of homozygosity (ROH) were also investigated in the germline exome data (Table 5). The individuals P05, P16, and P18 harbor several large ROH, evidencing parental consanguinity. Germline 11p15.5 loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was not observed in any of the patients by exome analysis. However, in one of the patients (P21), a somatic 11p LOH event was detected in the respective tumor sample (Supplementary Figure S3).

Discussion

We explored the clinical features and spectrum of rare germline variants possibly associated with cancer risk in 30 children who developed HB. We report here an enrichment of birth defects in HB patients (37%), mainly craniofacial (17%, including craniosynostosis) and kidney (7%) anomalies, as well as Hirschsprung disease (7%) and nail dysplasia (7%). There is a growing robust bulk of evidence emphasizing that various birth defects occur in association with a significant increase in the risk of developing childhood cancer (Krivit and Good, 1957; Agha et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2017). Recent studies also supported an increased risk of pediatric cancer in individuals with birth defects unrelated to chromosomal abnormalities or known genetic syndromes (Norwood et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2017). HB are reported to occur in association with a wide variety of congenital abnormalities (Narod et al., 1997; Ansell et al., 2005; Scollon et al., 2017), especially craniosynostosis and renal anomalies (de Camargo et al., 2011), which we also observed in this study. Two recent studies used large population-based linkage data to investigate the association between birth defects and childhood cancer, showing that HB are more prevalent in children with birth defects (5.0% in this group compared to 1.3% in children with cancer; Schraw et al., 2020) and frequently occurs in association with craniosynostosis (Lupo et al., 2019). It is interesting that we found in this group of patients a marginally significant result suggesting a tendency of high-risk tumors to develop in patients who also have craniofacial defects. In addition, a large case-control study confirmed the association between HB and kidney and bladder abnormalities (Venkatramani et al., 2014). In this study, we also described the cases of two patients with Hirschsprung disease and HB, a condition with extensive genetic heterogeneity (Sergi et al., 2017; Heuckeroth, 2018); most Hirschsprung disease cases are sporadic (approximately 70%), while a smaller portion of patients have other associated congenital anomalies. However, pathogenic, or likely pathogenic variants mapped to morbid OMIM genes that could explain the syndromic phenotypes of our patients were not detected, reinforcing that, despite the long-standing knowledge about the intersection between biological pathways of cancer and development, the etiology of most of these associations in specific cases remains unknown.

There is a recognized sexual dimorphism in HB, with increased prevalence in males (Spector and Birch, 2012; Williams and Spector, 2019), and this study also reflected this tendency. We investigated whether this sex bias could be explained by an increased burden of rare damaging variants in one of the sexes; however, significant differences were not detected, suggesting that most likely environmental factors modulate the sexual dimorphism in HB prevalence.

In addition to SNV/indel variants, germline CNVs were already reported as causally related to cancer (Krepischi et al., 2012), but pathogenic CNVs affecting known/candidate CPGs were not detected in this study. One patient (P19) carried a gain of an entire Y chromosome, which is associated with an increased risk of learning disabilities, behavioral disturbances, and other clinical signs (Lalatta et al., 2012; Bardsley et al., 2013). Moreover, two 15q11.2 CNVs, considered risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders (Butler, 2017; Rafi and Butler, 2020), were identified in two HB patients (P21 and P28). Only one patient (P28) presented an unspecific clinical feature related to the condition associated with its CNV (developmental delay). However, all these detected copy number alterations are known to present incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity. Importantly, germline 11p15.5 LOH, a common molecular mechanism resulting in epigenetic alterations known to increase the HB risk (Carrillo-Reixach et al., 2020; Fiala et al., 2020) as not detected in any of the patients.

Germline mutations have been detected in 8–18% of children and adolescents with cancer (Zhang et al., 2015; Akhavanfard et al., 2020; Capasso et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2021), and the most prevalent CPGs reported to be mutated are TP53, APC, BRCA2, NF1, PMS2, RB1, and RUNX1 (Zhang et al., 2015). In a very recent work about the spectrum of germline mutations in childhood cancer, most of the mutations (55%) were mapped to genes not previously associated with the patient’s tumor type (Newman et al., 2021); this work included a small number of HB patients (3 patients) with no pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Our findings revealed a high burden of damaging germline variants mapped to CPGs, with only 40% of these patients presenting a family history of cancer. Most of the variants affected autosomal-dominant CPGs not previously linked to HB, since only one mutation was detected in a known gene of HB development (APC), in a familial context of relatives diagnosed with FAP/colon cancer which segregated with the APC mutation. Interestingly, our data showed a clear predominance of CPGs related to gastrointestinal/colorectal cancer risk, such as familial adenomatous polyposis one and 2 (APC and MUTYH), nonpolyposis colorectal cancer hereditary types 1 (MSH2) and 6 (TGFBR2), Li-Fraumeni syndrome 2 (CHEK2), and Diamond-Blackfan anemia 1 (RPS19). Furthermore, the CPGs DROSHA and VHL, with putative P/LP variants, are known to be associated with renal cancer. Finally, a LoF variant was identified in the DNA repair gene ERCC5, in which homozygous mutations increase the skin cancer risk, and a damaging missense variant was mapped to FAH and causes an autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by progressive liver disease with increased liver cancer risk. Compared to previous pan-cancer studies, although not in HB patients, the findings of germline variants in APC, CHEK2, ERCC5, MSH2, MUTYH, and VHL were also detected in our work (Zhang et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2018a; Grobner et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2021).

We also observed numerous rare damaging VUS in known or candidate CPGs. Variants mapped to the ATM, BRCA2, COL7A1, DHCR7, DOCK8, FANCD2, FANCM, and GLI3 genes were observed in more than one HB patient. In particular, the same DHCR7 VUS (c.988G > A) was spotted in two patients (P09, born with only one functional kidney, and P26), both diagnosed with low-risk epithelial fetal HB; this gene encodes an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to cholesterol (Fitzky et al., 1998) and is a candidate for familial breast cancer in BRCA1-and BRCA2-negative breast cancer families (Shahi et al., 2019), in a recessive mode of action. As in our study, VUS mapped to MET, ATM, SLX4, and FANCA were also reported in HB patients in a recently published large study (Newman et al., 2021).

Strong support exists for the hypothesis that monoallelic CPG mutations confer an increased risk of cancer for adult carriers, while biallelic carriers would have a high risk of childhood cancer (Rahman and Scott, 2007). More recently, large studies have shown that variants in heterozygosity affecting recessive genes can also increase the predisposition to pediatric cancer (Savary et al., 2020), and a second hit in the tumor, such as a loss of heterozygosity or an inactivation of the second allele, has been observed in some of these patients. A highlight has been given to the role of germline monoallelic variants in cancer predisposition in genes involved in the recognition and repair of DNA damage, such as the ATM, PALB2, and Fanconi anemia genes (Thompson et al., 2005; Renwick et al., 2006; Antoniou et al., 2014; Helgason et al., 2015; Rebbeck et al., 2015; Esteban-Jurado et al., 2016; Esai Selvan et al., 2019). Since 1971 (Swift et al., 1971), it was proposed that individuals who were heterozygous for the Fanconi anemia genes might be at increased risk of cancer, and the premise would be that a modest reduction in the DNA repair efficiency could lead to tumor development. In our work, we detected relevant monoallelic variants in CPGs associated with recessive clinical conditions (FAH, ERCC5, and MUTYH) and in DNA repair genes (MSH2, CHEK2, ERCC5, and MUTYH). Recently, it has been shown that carriers of monoallelic loss of function MUTYH germline variants are at a higher risk of developing cancer, especially in tumors with frequent loss of heterozygosity events, such as adrenal adenocarcinoma, although the overall risk is still low (Barreiro et al., 2022); unfortunately, tumor sample of Patient P28, who carry a germline heterozygous MUTYH variant, was not available to check if loss of heterozygosity was present as a second hit, as suggested by authors. In addition, we observed a general enrichment of heterozygous germline damaging VUS affecting DNA repair genes related to Fanconi anemia, nucleotide and base excision repair, and homologous recombination repair. Sequencing the tumors of the carriers could contribute to changing the classification of such variants (Newman et al., 2021) and clarifying the role of these variants in cancer predisposition.

One of the most interesting findings of this study was the disclosure of rare germline damaging variants affecting genes linked to liver differentiation and function, such as FAH, that cause a recessive disorder related to hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Several rare damaging variants were observed in genes of the cytochrome P450 (CYP) family, including one pathogenic heterozygous variant in CYP21A2 (OMIM #201910 ADRENAL HYPERPLASIA, CONGENITAL, DUE TO 21-HYDROXYLASE DEFICIENCY, a recessive condition associated with testicular neoplasia in adults—P22) and two heterozygous pathogenic CYP1B1 variants (OMIM #617315, #231300; recessive conditions) detected in different patients (P03 and P30). Ten rare variants mapped to CYP1A1 (one LoF and nine missense variants), which is associated with primary liver metabolism, were present in eight patients (26%). CYP1A1 encodes a xenobiotic-metabolizing enzyme acting in the placenta (Yan et al., 2005; Suter et al., 2010; Stejskalova and Pavek, 2011), as well as in several drugs and compounds widely used in pharmacotherapy (Willis et al., 2018; Kapelyukh et al., 2019) or present in the diet (Ito et al., 2007). CYP1A1 expression is transcriptionally regulated through the AhR receptor (Kawashiro et al., 1998; Delescluse et al., 2000; Kamenickova et al., 2013) and various exogenous AhR binders, such as nitrosamines, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, and halogenated dioxins, can be found in products from combustion processes, such as chimney soot, grilled food, and cigarette smoke, or as the product of incineration waste (Larigot et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2020; Schanz et al., 2020; Shahin et al., 2020). Elevated CYP1A1 activity through AhR activation in the placentas of female smokers has been associated with pregnancy complications, including low birth weight (Stejskalova et al., 2011), a known risk factor for HB. In our previous study (Aguiar et al., 2020), in which we investigated the mutational burden of HB, a mutational signature like the COSMIC 29 signature was detected, which was initially observed only in oral gengivo-buccal squamous cell carcinoma, which develops in individuals with the habit of chewing tobacco. Currently, this mutational signature has also been detected in patients with lung, thyroid, bladder, biliary, breast, pancreas, liver, and kidney cancer and can be linked to nitrosamine exposure (Alexandrov et al., 2015). It is interesting to notice that two of the patients carrying germline CYP1A1 variants developed HBs with predominance of S29. Therefore, we can speculate that a defective response during pregnancy to xenobiotic exposure, such as nitrosamines, could be linked to CYP1A1-damaging germline variants, increasing the risk for HB development, and resulting in the mutational signature we previously found in HB.

In conclusion, our major findings in HB patients were the detection of germline variants in CPGs associated with gastrointestinal/colorectal and renal cancer risk, not always linked to a familial history of cancer; the enrichment of monoallelic variants in CPGs and DNA repair genes; and a high frequency of birth defects. One limitation of our study is the small size of the group of patients, which precludes robust statistical analysis and demands further evaluation of germline data of larger cohorts; however, HB is indeed an ultrarare condition, and this is the largest assessment of germline variants in HB patients to date. Another point that deserves to be mentioned is that we did not investigate germline 11p15.5 epimutations, which are known to be associated with increased HB risk; this limitation was only partially overcome by the investigation of 11p15 regions of homozygosity in exome data. Finally, most studies of HB tumors are from North America, Europe, and Asia, and this work is pioneering in South America and contributes to elucidating the genetic architecture of HB risk. Further validation of the genes highlighted as HB germline risk factors in other cohorts can provide new insights regarding HB development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families who enrolled in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors. Data is submitted to the https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ with identifier: SUB11168694 (SCV002103098 - SCV002103150).

Ethics Statement

Thirty children diagnosed with hepatoblastoma were enrolled in this study, and their parents, when available. Patients are from five different Brazilian`s institutes: A. C. Camargo Cancer Center, Adolescent and Child with Cancer Support Group (GRAACC), Pediatric Cancer Institute (ITACI), Baleia`s Hospital and Hospital da Criança Conceição. The Research Ethics Committee of the respective Institutions approved this research using these biological samples, and all samples were collected after informed signed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by TA, AT, JS and AK. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TA, AT and AK and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from FAPESP (CEPID - Human Genome and Stem Cell Research Center 2013/08028-1; 2018/21047-9; fellowships: 2018/05961-2, 2016/04785-0, 2019/17423-8) and CNPq (141625/2016-3). The funders had no roles in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Author IC was employed by Rede D’OR-São Luiz.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.858396/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CNV, Copy number variant; CPGs, Cancer predisposing genes; FA, Fanconi anemia; FAP, Familial adenomatous polyposis; FFPE, Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; HB, Hepatoblastoma; IGV, Integrated Genomics Viewer; LoF, Loss of function; LP, Likely pathogenic; P, Pathogenic; VUS, Variant of uncertain significance; WES, Whole-exome sequencing.

References

- Agha M. M., Williams J. I., Marrett L., To T., Zipursky A., Dodds L. (2005). Congenital Abnormalities and Childhood Cancer. Cancer 103, 1939–1948. 10.1002/cncr.20985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar T. F. M., Rivas M. P., Costa S., Maschietto M., Rodrigues T., Sobral de Barros J., et al. (2020). Insights into the Somatic Mutation Burden of Hepatoblastomas from Brazilian Patients. Front. Oncol. 10, 556. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhavanfard S., Padmanabhan R., Yehia L., Cheng F., Eng C. (2020). Comprehensive Germline Genomic Profiles of Children, Adolescents and Young Adults with Solid Tumors. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–13. 10.1038/s41467-020-16067-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov L. B., Jones P. H., Wedge D. C., Sale J. E., Campbell P. J., Nik-Zainal S., et al. (2015). Clock-like Mutational Processes in Human Somatic Cells. Nat. Genet. 47, 1402–1407. 10.1038/ng.3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell P., Mitchell C. D., Roman E., Simpson J., Birch J. M., Eden T. O. B. (2005). Relationships between Perinatal and Maternal Characteristics and Hepatoblastoma: a Report from the UKCCS. Eur. J. Cancer 41, 741–748. 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou A. C., Casadei S., Heikkinen T., Barrowdale D., Pylkäs K., Roberts J., et al. (2014). Breast-cancer Risk in Families with Mutations in PALB2. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 497–506. 10.1056/NEJMoa1400382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeg G. H., Matsumine A., Kuroda T., Bhattacharjee R. N., Miyashiro I., Toyoshima K., et al. (1995). The Tumour Suppressor Gene Product APC Blocks Cell Cycle Progression from G0/G1 to S Phase. EMBO J. 14 (22), 5618–5625. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00249.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bąk A., Janiszewska H., Junkiert-Czarnecka A., Heise M., Pilarska-Deltow M., Laskowski R., et al. (2014). A Risk of Breast Cancer in Women - Carriers of Constitutional CHEK2 Gene Mutations, Originating from the North - Central Poland. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 12, 10. 10.1186/1897-4287-12-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardsley M. Z., Kowal K., Levy C., Gosek A., Ayari N., Tartaglia N., et al. (2013). 47,XYY Syndrome: Clinical Phenotype and Timing of Ascertainment. J. Pediatr. 163, 1085–1094. 10.1016/J.JPEDS.2013.05.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro R. A. S., Sabbaga J., Rossi B. M., Achatz M. I. W., Bettoni F., Camargo A. A., et al. (2022). Monoallelic Deleterious MUTYH Germline Variants as a Driver for Tumorigenesis. J. Pathol. 256 (2), 214–222. 10.1002/path.5829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. G. (2017). Clinical and Genetic Aspects of the 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 Microdeletion Disorder. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 61, 568–579. 10.1111/jir.12382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso M., Montella A., Tirelli M., Maiorino T., Cantalupo S., Iolascon A. (2020). Genetic Predisposition to Solid Pediatric Cancers. Front. Oncol. 10, 2083. 10.3389/FONC.2020.590033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capellini A., Williams M., Onel K., Huang K.-L. (2021). The Functional Hallmarks of Cancer Predisposition Genes. Cmar Vol. 13, 4351–4357. 10.2147/CMAR.S311548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro D. M., Ramalho R. F., Ramalho R. F., Maschietto M. (2016). Gene Expression in Wilms Tumor: Disturbance of the Wnt Signaling Pathway and MicroRNA Biogenesis. Wilms Tumor 10, 149–162. 10.15586/CODON.WT.2016.CH10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Reixach J., Torrens L., Simon-Coma M., Royo L., Domingo-Sàbat M., Abril-Fornaguera J., et al. (2020). Epigenetic Footprint Enables Molecular Risk Stratification of Hepatoblastoma with Clinical Implications. J. Hepatol. 73 (2), 328–341. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta R., Del Baldo G., Miele E., Po A., Besharat Z. M., Nazio F., et al. (2020). Cancer Predisposition Syndromes and Medulloblastoma in the Molecular Era. Front. Oncol. 10, 566822. 10.3389/FONC.2020.566822/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis D., Yu J., Evani U. S., Jackson A. R., Paithankar S., Coarfa C., et al. (2012). An Integrative Variant Analysis Suite for Whole Exome Next-Generation Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 8. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke L., Fairley S., Zheng-Bradley X., Streeter I., Perry E., Lowy E., et al. (2017). The International Genome Sample Resource (IGSR): A Worldwide Collection of Genome Variation Incorporating the 1000 Genomes Project Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D854–D859. 10.1093/NAR/GKW829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curia M. C., Zuckermann M., De Lellis L., Catalano T., Lattanzio R., Aceto G., et al. (2008). Sporadic Childhood Hepatoblastomas Show Activation of β-catenin, Mismatch Repair Defects and P53 Mutations. Mod. Pathol. 21, 7–14. 10.1038/modpathol.3800977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czauderna P., Garnier H. (2018). Hepatoblastoma: Current Understanding, Recent Advances, and Controversies. F1000Res 7, 53. 10.12688/f1000research.12239.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czauderna P., Haeberle B., Hiyama E., Rangaswami A., Krailo M., Maibach R., et al. (2016). The Children's Hepatic Tumors International Collaboration (CHIC): Novel Global Rare Tumor Database Yields New Prognostic Factors in Hepatoblastoma and Becomes a Research Model. Eur. J. Cancer 52, 92–101. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David Bick M., Aziz N., Bale S., Richards L., Soma Das P., Gastier-Foster J., et al. (2015). Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology Sue. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30.Standards [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Camargo B., de Oliveira Ferreira J. M., de Souza Reis R., Ferman S., de Oliveira Santos M., Pombo-de-Oliveira M. S. (2011). Socioeconomic Status and the Incidence of Non-central Nervous System Childhood Embryonic Tumours in Brazil. BMC Cancer 11, 160. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBaun M. R., Tucker M. A. (1998). Risk of Cancer during the First Four Years of Life in Children from the Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Registry. J. Pediatr. 132, 398–400. 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70008-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delescluse C., Lemaire G., de Sousa G., Rahmani R. (2000). Is CYP1A1 Induction Always Related to AHR Signaling Pathway? Toxicology 153, 73–82. 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00305-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing J. R., Wilson R. K., Zhang J., Mardis E. R., Pui C.-H., Ding L., et al. (2012). The Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Nat. Genet. 44, 619–622. 10.1038/ng.2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esai Selvan M., Klein R. J., Gümüş Z. H. (2019). Rare, Pathogenic Germline Variants in Fanconi Anemia Genes Increase Risk for Squamous Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 1517–1525. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Jurado C., Franch-Expósito S., Franch-Expósito S., Muñoz J., Ocaña T., Carballal S., et al. (2016). The Fanconi Anemia DNA Damage Repair Pathway in the Spotlight for Germline Predisposition to Colorectal Cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 24, 1501–1505. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassihi H., Sethi M., Fawcett H., Wing J., Chandler N., Mohammed S., et al. (2016). Deep Phenotyping of 89 Xeroderma Pigmentosum Patients Reveals Unexpected Heterogeneity Dependent on the Precise Molecular Defect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (9), E1236–E1245. 10.1073/pnas.1519444113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felicio P. S., Grasel R. S., Campacci N., Paula A. E., Galvão H. C. R., Torrezan G. T., et al. (2021). Whole‐exome Sequencing of Non‐ BRCA1/BRCA2 Mutation Carrier Cases at High‐risk for Hereditary Breast/ovarian Cancer. Hum. Mutat. 42, 290–299. 10.1002/HUMU.24158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Polychronidis G., Heger U., Frongia G., Mehrabi A., Hoffmann K. (2019). Incidence Trends and Survival Prediction of Hepatoblastoma in Children: A Population-Based Study. Cancer Commun. 39, 62. 10.1186/s40880-019-0411-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala E. M., Ortiz M. V., Kennedy J. A., Glodzik D., Fleischut M. H., Duffy K. A., et al. (2020). 11p15.5 Epimutations in Children with Wilms Tumor and Hepatoblastoma Detected in Peripheral Blood. Cancer 126, 3114–3121. 10.1002/cncr.32907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzky B. U., Witsch-Baumgartner M., Erdel M., Lee J. N., Paik Y.-K., Glossmann H., et al. (1998). Mutations in the 7-sterol Reductase Gene in Patients with the Smith-Lemli-Opitz Syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 8181–8186. 10.1073/PNAS.95.14.8181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Fajardo K. V., Adams D., Mason C. E., Sincan M., Tifft C., Toro C., et al. (2012). Detecting False-Positive Signals in Exome Sequencing. Hum. Mutat. 33, 609–613. 10.1002/humu.22033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröbner S. N., Worst B. C., Worst B. C., Weischenfeldt J., Buchhalter I., Kleinheinz K., et al. (2018). The Landscape of Genomic Alterations across Childhood Cancers. Nature 555, 321–327. 10.1038/nature25480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H., Bennett R. L., Buchanan A., Pearlman R., Wiesner G. L. (2015). Guideline Development Group, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Professional Practice and Guidelines Committee and National Society of Genetic Counselors Practice Guidelines CommitteeA Practice Guideline from the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors: Referral Indications for Cancer Predisposition Assessment. Genet. Med. 17, 70–87. 10.1038/gim.2014.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck J. E., Meyers T. J., Lombardi C., Park A. S., Cockburn M., Reynolds P., et al. (2013). Case-control Study of Birth Characteristics and the Risk of Hepatoblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 37, 390–395. 10.1016/j.canep.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason H., Rafnar T., Olafsdottir H. S., Jonasson J. G., Sigurdsson A., Stacey S. N., et al. (2015). Loss-of-function Variants in ATM Confer Risk of Gastric Cancer. Nat. Genet. 47, 906–910. 10.1038/ng.3342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuckeroth R. O. (2018). Hirschsprung Disease - Integrating Basic Science and Clinical Medicine to Improve Outcomes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 152–167. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman B. A., Pollock B. H., Tomlinson G. E. (2005). The Spectrum of APC Mutations in Children with Hepatoblastoma from Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Kindreds. J. Pediatr. 147, 263–266. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA) (2016). Incidência, mortalidade e morbidade hospitalar por câncer em crianças, adolescentes e adultos jovens no Brasil: informações dos registros de câncer e do sistema de mortalidade. Rio de Janeiro: Coordenação de Prevenção e VigilânciaINCA. [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., Chen C., Satoh J., Yim S., Gonzalez F. J. (2007). Dietary Phytochemicals Regulate Whole-Body CYP1A1 Expression through an Arylhydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator-dependent System in Gut. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1940–1950. 10.1172/JCI31647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. J., Lee J. M., Ahsan K., Padda H., Feng Q., Partap S., et al. (2017). Pediatric Cancer Risk in Association with Birth Defects: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 12, e0181246. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenickova A., Anzenbacherova E., Pavek P., Soshilov A. A., Denison M. S. (2013). Effects of Anthocyanins on the AhR-Cyp1a1 Signaling Pathway in Human Hepatocytes and Human Cancer Cell Lines. Toxicol. Lett. 221, 1–8. 10.1016/J.TOXLET.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamien B. A., Gabbett M. T. (2009). Aicardi Syndrome Associated with Hepatoblastoma and Pulmonary Sequestration. Am. J. Med. Genet. 149A, 1850–1852. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapelyukh Y., Henderson C. J., Scheer N., Rode A., Wolf C. R. (2019). Defining the Contribution of CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 to Drug Metabolism Using Humanized CYP1A1/1A2 and Cyp1a1/Cyp1a2 Knockout Mice. Drug Metab. Dispos. 47, 907–918. 10.1124/DMD.119.087718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski K. J., Francioli L. C., Tiao G., Cummings B. B., Alföldi J., Wang Q., et al. (2020). The Mutational Constraint Spectrum Quantified from Variation in 141,456 Humans. Nature 581, 434–443. 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashiro T., Yamashita K., Zhao X. J., Koyama E., Tani M., Chiba K., et al. (1998). A Study on the Metabolism of Etoposide and Possible Interactions with Antitumor or Supporting Agents by Human Liver Microsomes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286, 1294–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Y., Jung S.-H., Kim M. S., Han M.-R., Park H.-C., Jung E. S., et al. (2017). Genomic Profiles of a Hepatoblastoma from a Patient with Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome with Uniparental Disomy on Chromosome 11p15 and Germline Mutation of APC and PALB2. Oncotarget 8, 91950–91957. 10.18632/oncotarget.20515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler O., Quehenberger F., Benesch M., Seidel M. G. (2018). The Iceberg Map of Germline Mutations in Childhood Cancer. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 30, 855–863. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler S., Carmody L., Vasilevsky N., Jacobsen J. O. B., Danis D., Gourdine J. P., et al. (2019). Expansion of the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) Knowledge Base and Resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1018–D1027. 10.1093/nar/gky1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopanos C., Tsiolkas V., Kouris A., Chapple C. E., Albarca Aguilera M., Meyer R., et al. (2019). VarSome: the Human Genomic Variant Search Engine. Bioinformatics 35, 1978–1980. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krepischi A. C. V., Pearson P. L., Rosenberg C. (2012). Germline Copy Number Variations and Cancer Predisposition. Future Oncol. 8, 441–450. 10.2217/fon.12.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivit W., Good R. A. (1957). Simultaneous Occurrence of Mongolism and Leukemia. AMA Am. J. Dis. Child. 94, 289. 10.1001/archpedi.1957.04030040075012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalatta F., Folliero E., Cavallari U., Di Segni M., Gentilin R., Quagliarini D., et al. (2012). Early Manifestations in a Cohort of Children Prenatally Diagnosed with 47,XYY. Role of Multidisciplinary Counseling for Parental Guidance and Prevention of Aggressive Behavior. Ital. J. Pediatr. 38, 52. 10.1186/1824-7288-38-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larigot L., Juricek L., Dairou J., Coumoul X. (2018). AhR Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Functions. Biochimie Open 7, 1–9. 10.1016/J.BIOPEN.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2013). Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. Available at: http://github.com/lh3/bwa (Accessed May 18, 2020).

- Lu J., Shang X., Zhong W., Xu Y., Shi R., Wang X. (2020). New Insights of CYP1A in Endogenous Metabolism: a Focus on Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Diseases. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 10, 91–104. 10.1016/J.APSB.2019.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft F. (2010). The Rise of a Ribosomopathy and Increased Cancer Risk. J. Mol. Med. 88, 1–3. 10.1007/s00109-009-0570-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupo P. J., Schraw J. M., Desrosiers T. A., Nembhard W. N., Langlois P. H., Canfield M. A., et al. (2019). Association between Birth Defects and Cancer Risk Among Children and Adolescents in a Population-Based Assessment of 10 Million Live Births. JAMA Oncol. 5 (8), 1150–1158. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Beeghly-Fadiel A., Lu W., Shi J., Xiang Y.-B., Cai Q., et al. (2012). Pathway Analyses Identify TGFBR2 as Potential Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene: Results from a Consortium Study Among Asians. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 1176–1184. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Liu Y., Liu Y., Alexandrov L. B., Edmonson M. N., Gawad C., et al. (2018a). Pan-cancer Genome and Transcriptome Analyses of 1,699 Paediatric Leukaemias and Solid Tumours. Nature 555, 371–376. 10.1038/nature25795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., et al. (2010). The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing Next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers R. L., Maibach R., Hiyama E., Häberle B., Krailo M., Rangaswami A., et al. (2017). Risk-stratified Staging in Paediatric Hepatoblastoma: a Unified Analysis from the Children's Hepatic Tumors International Collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 18, 122–131. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30598-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narod S. A., Hawkins M. M., Robertson C. M., Stiller C. A. (1997). Congenital Anomalies and Childhood Cancer in Great Britain. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 60, 474–485. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]