Abstract

Input from diverse stakeholders is critical to the process of designing healthcare interventions. This study applied a novel mixed-methods, stakeholder-engaged approach to co-design a psychosocial intervention for mothers expecting a baby with congenital heart disease (CHD) and their partners to promote family wellbeing. The research team included parents and clinicians from 8 health systems. Participants were 41 diverse parents of children with prenatally diagnosed CHD across the 8 health systems. Qualitative data were collected through online crowdsourcing and quantitative data were collected through electronic surveys to inform intervention co-design. Phases of intervention co-design were: (I) Engage stakeholders in selection of intervention goals/outcomes; (II) Engage stakeholders in selection of intervention elements; (III) Obtain stakeholder input to increase intervention uptake/utility; (IV) Obtain stakeholder input on aspects of intervention design; and (V) Obtain stakeholder input on selection of outcome measures. Parent participants anticipated the resulting intervention, HEARTPrep, would be acceptable, useful, and feasible for parents expecting a baby with CHD. This model of intervention co-design could be used for the development of healthcare interventions across chronic diseases.

Keywords: behavioral health, cardiovascular disease, caregiving, community engagement, patient engagement, qualitative methods

Introduction

Diagnosis of a pediatric chronic disease affects the emotional wellbeing of parents, families, and children (1). Parents of children with chronic diseases report elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and traumatic stress (2,3), which can be stronger predictors of child developmental and behavioral outcomes than medical factors (4,5). For congenital conditions, such as congenital heart disease (CHD), diagnosis may occur prenatally and can lead to substantial stress and trauma for expectant mothers and their partners (6–11). Parent and clinician stakeholders across pediatric chronic diseases emphasize the need for family-based psychosocial interventions soon after the initial diagnosis to prevent long-term negative psychological effects (9,12–18). While psychosocial interventions have previously been evaluated with families of children with CHD during hospitalization and after hospital discharge (16,17), conceptually driven prenatal psychosocial interventions for mothers expecting a baby with CHD and their partners are currently being developed and tested to address the substantial stress and trauma experienced during this critical stage (N. Kasparian, personal communication, January 20, 2022) (19).

Input from patients and parents with lived experience is critical to the process of designing and testing healthcare interventions (20). Rigorous models of intervention development include stakeholder engagement as a core component (21,22). Patient and parent input, typically obtained through qualitative interviews or focus groups, is used to define and refine the basic elements of the intervention to support feasibility and acceptability (21). Consistent with core features of participatory action research (23), patients and parents should be active partners in the research process, including developing the research questions, identifying meaningful goals and outcomes, interpreting results, and deciding what actions should occur in response to the research findings. Including patients and parents as active partners in the process of intervention design is a departure from more traditional, investigator-led approaches and is increasingly gaining momentum in pediatric research (24–27). However, included stakeholders are often not culturally, socioeconomically, linguistically, or gender diverse (24,26–28). The resources required to engage in the research process (eg, time, transportation, childcare, language translation) may deter patients and parents from underserved or minority communities from volunteering and may inhibit research teams from engaging underrepresented groups. Additionally, mistrust of the healthcare system due to historical and ongoing discrimination likely serves as a barrier (29).

Models of intervention co-design that facilitate engagement of diverse groups at every phase are needed to ensure acceptability and feasibility for all stakeholders and could result in more effective intervention strategies. This paper describes a novel five-phase, mixed-methods, virtually-based approach to co-design healthcare interventions with parent stakeholders from diverse backgrounds and demonstrates how the results inform the co-design of HEARTPrep, a psychosocial intervention to promote family wellbeing following prenatal diagnosis of CHD.

Methods

Parent Participants

Participants were parents of children with CHD (ages 6 months to 5 years) who were diagnosed prenatally and underwent cardiac surgery during infancy at 1 of 8 health systems within PEDSnet (30). PEDSnet is a national network established to support the efficient conduct of pediatric research and quality improvement across institutions (30). Inclusion criteria included the ability to read and write in English or Spanish and access to the internet on a smartphone, tablet, or computer. Only one parent per family was eligible to participate to ensure independence of participant data. Parents/guardians not involved in the child's prenatal care (eg, caregivers who assumed care after birth) were not included.

Research Partners

The research team included clinician research partners (CRPs) and parent research partners (PRPs). CRPs were 8 healthcare providers from each of the 8 health systems within PEDSnet. CRPs were selected based on their roles in the care of fetal or neonatal patients with CHD and their families within their respective health systems, while also intentionally including a range of disciplines (fetal and pediatric cardiology, neonatology, psychology, and nursing). Four parents (2 mothers and 2 fathers from 4 families) were identified by the CRPs and invited to serve as PRPs based on their relevant CHD experiences, with intentional inclusion of parents representing a range of racial and ethnic backgrounds. They were paid for their time on the project (31). CRPs assisted with participant recruitment, and both PRPs and CRPs contributed to study development, results interpretation, and intervention design through monthly phone/virtual meetings and frequent email correspondence.

Participant Recruitment

Participants were selected using maximum variation purposeful sampling to identify variation and shared patterns in perspectives across heterogeneous groups (32). Over 2 months (December 2019-February 2020), CRPs identified approximately 12 eligible parents within each health system who represented a range (ie, maximum variation) of racial and ethnic backgrounds, including both English- and Spanish-speaking mothers and fathers, with the goal of enrolling a diverse sample of 50 parents. Identified parents were provided with a flyer about the study in person or by email/text. The flyer was available in English/Spanish and included an electronic link and QR code to a REDCap survey containing a study description and electronic consent form (eConsent) (33). Parents who provided eConsent were directed to a brief demographic questionnaire (34), then emailed instructions to set up a de-identified account and join 1 of 2 private online groups (English- or Spanish-language) within Yammer.com (Version 3.4.5, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), the secure social networking platform used for qualitative data collection. This study received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, and the eConsent process and data collection, management, and analysis were conducted at Nemours Children's Hospital, Delaware.

Data Collection and Intervention Co-Design

Data collection was a multiphasic, iterative process completed between February and December 2020 and including both qualitative (Phases I-III) and quantitative (Phases IV-V) data to inform the co-design of HEARTPrep (Table 1). Qualitative data were collected through Yammer using crowdsourcing (35), which engages an online community to generate ideas and produce results (see Sood et al (36) 2021 for a review of crowdsourcing methods for qualitative data collection). Study questions were translated into Spanish by a bilingual team member and then posted to the English- and Spanish-language private online Yammer groups. Online postings included 2 to 4 questions each, with 2 weeks between postings, for a total of 28 questions. The first set of posted questions was selected a priori by the research team to elicit a range of feelings and experiences related to prenatal diagnosis of CHD (How did you learn that your baby may have a heart condition? Who told you and how did they tell you? What do you remember most about the days and weeks after finding out that your baby may have a heart condition? What stands out to you?). The 26 subsequent questions were informed by participant responses to prior questions (Table 1). Participants received notifications through the Yammer app and email when questions were posted and provided responses of any length using their mobile device or computer. Participants could also view and comment on other participants’ responses (ie, interact as a “crowd” (36)). Links to 2 REDCap surveys were also posted within Yammer for quantitative data collection. Participants were paid per question/survey response.

Table 1.

Phases of Data Collection and Intervention Co-Design with Parent and Clinician Stakeholders.

| Phase | Method | Sample questions | Parent participant contributions | PRP/CRP contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Engage Stakeholders in Selection of Intervention Goals and Outcomes | Crowdsourcing: 7 open-ended questions over 8 weeks | What do you remember most about the days and weeks after finding out that your baby may have a heart condition? Which of these feelings and experiences were most challenging for you, and why? |

|

|

| Phase II: Engage Stakeholders in Selection of Intervention Elements | Crowdsourcing: 12 open-ended questions over 8 weeks | In the time before your baby was born, what helped you feel less distressed? What conversations, experiences, or actions made you feel more distressed? | For each of the 4 intervention goals:

|

|

| Phase III: Obtain Stakeholder Input to Increase Intervention Uptake/Utility | Crowdsourcing: 9 open-ended questions over 6 weeks | At what point during the pregnancy would you have liked to receive information on how to connect with other parents of a child with CHD? |

|

|

| Phase IV: Obtain Stakeholder Input on Aspects of Intervention Design | Online survey: 6 Likert scales, 11 open-ended questions | How helpful do you think HEARTPrep will be for parents who find out that their baby has a heart condition before birth? What would make it more helpful? |

|

|

| Phase V: Obtain Stakeholder Input on Selection of Outcome Measures | Online survey: 52 forced choice questions, 6 open-ended questions | Please review the statements below and let us know which are the best fit in describing the experiences of parents expecting a baby with CHD, which are a good fit, and which are not a good fit. |

|

|

Abbreviations: PRP, parent research partners; CRP, clinician research partners; CHD, congenital heart disease.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed using an inductive thematic approach, focused on subjective perceptions and experiences (37). Parent responses to open-ended questions were extracted from Yammer and uploaded into Dedoose Version 8 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). Data were coded through an iterative process led by a three-person coding team (ES, CG, APR), with input from all research team members. To establish inter-coder reliability, the coding team independently coded 4 participants’ complete responses in English (0.86-0.88 pooled Cohen's kappa coefficient), after which coding disagreements were resolved through discussion. The remaining responses were then divided among the coders for independent coding. All Spanish-language responses were coded by one bilingual team member. Qualitative themes informed the design of HEARTPrep. Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 50 parents who enrolled in the study, 41 (30 mothers, 11 fathers; 82%) set up an account on Yammer and responded to questions to inform the co-design of HEARTPrep (Phases I-III). All 8 health systems were represented within the final sample, and parents reflected a racially and socioeconomically diverse group, including 8 whose primary language was Spanish (6 provided Spanish-language responses) (Supplemental Material 1). All parents had a living child with CHD at the time of participation. Those who responded to questions on Yammer (n = 41) did not differ from the total enrolled sample on sociodemographic factors (sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual household income). A total of 23 (19 mothers, 4 fathers) parents subsequently provided input on the preliminary design of HEARTPrep (Phase IV) and 28 (24 mothers, 4 fathers) provided input on the selection of outcome measures (Phase V). The sociodemographic composition of these subgroups did not differ significantly from the total sample.

Phase I: Engage Stakeholders in Selection of Intervention Goals and Outcomes

A total of 12 difficult feelings/experiences and 8 helpful feelings/experiences after prenatal diagnosis of CHD were identified from qualitative data (Supplemental Material 2). Based on participant input regarding which feelings/experiences should be targeted through intervention, 4 intervention goals were established: (1) reduce distress (eg, anxiety, depression, anger), (2) reduce social isolation, (3) increase parenting self-efficacy, and (4) increase hope for mothers expecting a baby with CHD and their partners (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intervention Goals and Representative Quotes Supporting the Need for Each Goal.

| Intervention goals | Representative parent quotes |

|---|---|

| Reduce distress |

|

| Reduce social isolation |

|

| Increase parenting self-efficacy |

|

| Increase hope |

|

Many parents indicated that reducing distress and increasing parenting self-efficacy were the most urgent intervention goals, while noting the interrelated nature of all 4 goals and the likelihood that addressing one would improve the others. Several parents noted that reducing distress was a necessary first step in addressing other goals (eg, to be ready to connect with others which could reduce social isolation, to be able to process information that could increase parenting self-efficacy). Many parents noted that addressing these 4 goals through intervention would have likely improved their overall wellbeing (eg, less anxiety, depression, guilt), ability to enjoy and celebrate the pregnancy, relationship with their partner, understanding of their child's medical condition, and ability to make decisions for their child.

Phase II: Engage Stakeholders in Selection of Intervention Elements

Six broad categories of intervention elements were identified from qualitative data regarding experiences/actions during the prenatal period that were perceived as helpful or not helpful for achieving each of the 4 intervention goals (Table 3). These categories included (1) normalization and processing of emotions, (2) development of coping skills, (3) strategies for engaging a supportive network, (4) peer-to-peer support, (5) CHD educational tools, and (6) exploring the role of cultural beliefs and faith. Parents who responded in Spanish tended to report a strong reliance on their faith and described fewer experiences with peer-to-peer support and educational tools compared with parents responding in English.

Table 3.

Categories of Intervention Elements and Representative Quotes Supporting Each Category.

| Categories of intervention elements | Representative parent quotes |

|---|---|

| Normalization and processing of emotions |

|

| Development of coping skills |

|

| Strategies for engaging a supportive network |

|

| Peer-to-peer support |

|

| CHD educational tools |

|

| Exploring role of cultural beliefs and faith |

|

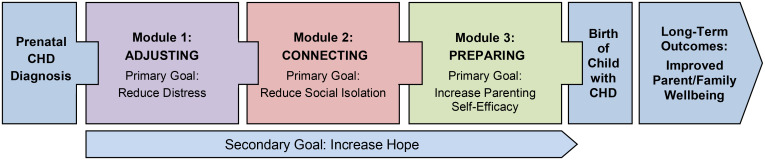

Results supported a modular intervention design, in which the intervention can be subdivided into meaningful units that are implemented in complement with one another (38). The research team determined that HEARTPrep will have 3 modules delivered during pregnancy following CHD diagnosis: the Adjusting module will focus on reducing distress, the Connecting module will focus on reducing social isolation, and the Preparing module will focus on increasing parenting self-efficacy (Figure 1). All 3 modules will focus secondarily on increasing hope. Each module will include intervention elements across the 6 broad categories listed above, aimed at achieving primary and secondary module goals (Supplemental Material 3).

Figure 1.

HEARTPrep Modular Intervention Design.

Phase III: Obtain Stakeholder Input to Increase Intervention Uptake and Utility

In Phase III, participants provided input on how HEARTPrep should be delivered to increase intervention uptake and utility. Many participants emphasized that intervention elements should be introduced by their fetal cardiac providers and embedded within their fetal cardiac care, while also being accessible at any time from anywhere. Participants generally described online support (reputable websites, peer-to-peer social networking groups) as most accessible, but added that it was difficult and time-consuming to seek out material from multiple sources. Based on this feedback, the research team decided that the optimal format for HEARTPrep would be a comprehensive mobile app, incorporating educational tools and resources that could be accessed at any time as well as live telehealth sessions with a psychosocial provider (eg, psychologist or social worker embedded within the cardiac team).

Participants provided input on the utility of including partners and other family members. Most were in favor of incorporating partners by scheduling one or more telehealth sessions with both partners to allow emotional expression, help partners understand the other person's coping styles and reactions, and address communication difficulties. Participants were less in favor of directly including other family members, noting that family members have varying levels of knowledge about CHD and sensitivity toward its emotional impact. Learning how to cope with and respond to unhelpful comments from family and friends was of interest to many parents. Examples included having access to educational tools that could be shared with family/friends with guidance on how to support expectant parents.

Participants also provided input on the optimal timing of intervention elements during pregnancy to increase uptake. Many parents wished they had received general information about intervention elements, such as professional mental health and peer-to-peer support, from the fetal cardiac team at the time of diagnosis with more detailed information provided over subsequent weeks. Several parents stated they would have been ready to access these intervention elements immediately, whereas others noted they would have appreciated the introduction at the time of diagnosis but needed time to process the diagnosis before engaging with the intervention.

Phase IV: Obtain Stakeholder Input on Aspects of Intervention Design

Twenty-three participants reviewed the preliminary description of HEARTPrep and provided input (Supplemental Material 4). Most respondents indicated that HEARTPrep would be very helpful (91%) and that the topics were very relevant (96%) for mothers and partners expecting a baby with CHD, though the importance of tailoring resources and supports as needed (eg, for single parents) was noted. Several parents emphasized the importance of facilitating peer-to-peer interaction (eg, providing information about peer-to-peer support options locally and through national organizations, such as Mended Little Hearts and Conquering CHD) in addition to reading about or listening to the experiences of other parents. The need for flexibility and an individualized approach to timing was a consistent theme that emerged from open-ended responses. Some parents felt the intervention could be condensed to ensure all elements have been completed in the case of preterm birth, whereas others felt that more time within a specific module would be helpful.

Most respondents (87%) reported favorable feedback regarding participation through a mobile app, with the vast majority (96%) noting that HEARTPrep would be very convenient. The need to access information and resources at any time was a consistent theme that emerged from open-ended responses. A few parents indicated that an app could allow them to participate in an intervention that they otherwise would have declined due to competing demands such as childcare responsibilities and medical appointments. While overall parents supported the use of telehealth within HEARTPrep, responses were mixed (78% liked telehealth “very much,” 17% “mostly,” and 4% “somewhat”). Many parents noted telehealth may be the most practical and accessible option for families who live far from the hospital; however, parents added that telehealth does not fully replace in-person interactions and that having an in-person option may be beneficial. The importance of ensuring accessibility for diverse families was also emphasized (eg, content provided in multiple languages, captions for individuals with hearing impairment).

Phase V: Obtain Stakeholder Input on Selection of Outcome Measures

Twenty-eight participants reviewed items from the PROMIS item banks for Emotional Distress (Depression, Anxiety, and Anger) (39), Social Isolation (40), General Self-Efficacy (41), and Meaning and Purpose (42), which were designed using item response theory to allow custom short forms to be created that yield comparable, standardized scores. Participant input regarding which items were the best fit for mothers expecting a baby with CHD and their partners informed the creation of custom PROMIS short forms to measure intervention outcomes (distress, social isolation, parenting self-efficacy, hope) (Supplemental Material 5).

Discussion

This project engaged parent and clinician stakeholders across 8 health systems to inform the co-design of an intervention to improve family wellbeing following prenatal diagnosis of CHD. The 5 phases of co-design were achieved using a combination of online crowdsourcing and survey-based methods in under 12 months. This approach could be adopted for the development of stakeholder-informed interventions across a range of chronic diseases.

Results support the need for an individualized approach to psychosocial intervention. HEARTPrep intervention elements were perceived as relevant to almost all parent participants as they are intended to address common challenges among expectant parents following prenatal diagnosis of a congenital anomaly (eg, self-blame, interpersonal challenges, lack of emotional preparedness) (9). However, participants reported varying needs regarding intervention timing and duration and the involvement of partners. Modular approaches are flexible by design (38) and may be especially useful for facilitating flexible delivery of intervention elements to culturally diverse families due to their ability to balance research evidence with individualized family needs (43). Just-in-time adaptive intervention designs, which aim to provide the right type and amount of support at the right time by adapting to the individual (44), may be particularly well suited to address the individualized needs of families affected by chronic disease.

The need for accessibility was emphasized throughout all phases. For parents expecting or caring for a child with chronic disease, competing demands, distance from the care center, and limited resources are likely to prevent many from accessing psychosocial intervention (18). Disproportionate intervention delivery to those with greater resources can widen health disparities (45). As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of virtual healthcare (eg, telehealth) has increased substantially (46). Even for families who could travel to the care center for psychosocial intervention, the ability to access intervention elements via mobile app at the time they are needed most and from a place that is comfortable and convenient is likely to enhance utility. A universally accessible app can also facilitate psychosocial intervention for families in the context of limited psychosocial resources within a particular healthcare setting. While intervention via mobile app, including telehealth, seems to meet needs for accessibility, in-person delivery of certain intervention elements should be offered as an option to facilitate the therapeutic relationship.

Many parents emphasized the importance of incorporating a focus on faith and cultural beliefs into intervention. Mental health and behavioral interventions have traditionally not included a strong emphasis on faith or cultural beliefs; however, more recent efforts to tailor interventions to specific ethnic and cultural groups have resulted in an increased focus on the role of culture and faith (47,48). The effects of cultural tailoring for intervention uptake and effectiveness are not yet well understood (48). In this study, faith was frequently described as central to the process of adjusting to and coping with CHD, particularly among Spanish-speaking parents, who were less likely to report having accessed peer-to-peer support or educational tools. Despite an increase in informational resources and peer-to-peer support options for parents of children with CHD over recent years, many of these resources are not available in languages other than English. Translation of resources initially created by and for English-speaking families may result in materials that are not optimally culturally relevant or sensitive. Intervention development research should include non-English-speaking participants to ensure intervention elements are accessible, useful, and relevant for culturally and linguistically diverse groups.

Limitations

While the ability to contribute to intervention co-design using a mobile device likely reduced barriers to participation for many parents, this methodology excluded parents with low literacy or without reliable Internet access. Despite the use of a sampling strategy that prioritized racial and ethnic diversity, the resulting sample differed from the broader population of parents of children with CHD with regard to education level (59% with college or graduate degree) and family structure (90% living with a spouse/partner). It will be important to evaluate through future research whether HEARTPrep is feasible and beneficial for underserved populations, with adaptations made as needed. Incorporating components of implementation science into future research evaluating HEARTPrep may help to promote the systematic uptake of research findings into routine care for diverse families receiving a prenatal diagnosis of CHD (49). All Spanish-language responses were coded by one bilingual team member after achieving inter-coder reliability on English-language responses. While coding in the original language is generally recommended as meaning may be lost from the participant's implicit expression when translated before coding (50), inter-coder reliability achieved with English-language responses may not fully generalize to Spanish-language responses. Lastly, while PROMIS item banks were designed to allow the creation of customized short forms with comparable standardized scores, PROMIS short forms have not previously been tested in this specific population. Future research will need to evaluate the psychometric properties of the custom short forms created to measure intervention outcomes.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that engaging parent and clinician stakeholders to inform the co-design of a psychosocial intervention is feasible over a relatively short period of time using a five-phase approach that incorporated online crowdsourcing and survey-based methods. This study resulted in the preliminary design of HEARTPrep, which is currently being pilot tested at Nemours Children's Hospital, Delaware with mothers expecting a baby with CHD and their partners. This approach to intervention co-design could be adopted for other disease groups, thereby incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives into the design of much-needed psychosocial interventions for patients and families.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the parent participants and parent research partners for their contributions to the design of HEARTPrep. The first author would also like to thank Christopher Forrest, MD, PhD for his mentorship on this project and the faculty of the PEDSnet Scholars Program for providing training in learning health systems research.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to conduct this study and report the results was obtained from the Nemours Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1395313).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number 5K12HS026393-03).

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Nemours Institutional Review Board's IRB# 1395313 approved protocol.

Statement of Informed Consent: Written electronic informed consent (eConsent) was obtained from the participating parents for their anonymized information to be published in this article. The Nemours Institutional Review Board approved the eConsent process.

ORCID iDs: Erica Sood https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8817-4213

Erin Riegel https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5403-7322

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Boat TF, Filigno S, Amin RS. Wellness for families of children with chronic health disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):825‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn LN Pechlivanoglou P Lee Y, Mahant S, Orkin J, Marson A, et al. Health outcomes of parents of children with chronic illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr. 2020;218:166‐77.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf-King SE, Anger A, Arnold EA, et al. Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(2):e004862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMaso D, Labella M, Taylor G, et al. Psychiatric disorders and function in adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries. J Pediatr. 2014;165(4):760‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCusker CG, Armstrong MP, Mullen M, et al. A sibling-controlled, prospective study of outcomes at home and school in children with severe congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2013;23(4):507‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, Kapse K, Jacobs M, et al. Association of maternal psychological distress with in utero brain development in fetuses with congenital heart disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):e195316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasparian N. Heart care before birth: a psychobiological perspective on fetal cardiac diagnosis. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;54:101142. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole JC Moldenhauer JS Berger K, Cary MS, Smith H, Martino V, et al. Identifying expectant parents at risk for psychological distress in response to a confirmed fetal abnormality. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(3):443‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dempsey AG, Chavis L, Willis T, et al. Addressing perinatal mental health risk within a fetal care center. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(1):125‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rychik J, Donaghue DD, Levy S, et al. Maternal psychological stress after prenatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2013;162(2):302‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lisanti AJ. Parental stress and resilience in CHD: a new frontier for health disparities research. Cardiol Young. 2018;28(9):1142‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickles DM, Lihn SL, Boat TF, et al. A roadmap to emotional health for children and families with chronic pediatric conditions. Pediatrics. 2020;145(2):e20191324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hynan MT, Hall SL. Psychosocial program standards for NICU parents. J Perinatol. 2015;35 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Utens E, Callus E, Levert E, et al. Multidisciplinary family-centred psychosocial care for patients with CHD: consensus recommendations from the AEPC Psychosocial Working Group. Cardiol Young. 2017;28(2):192‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasparian N, Winlaw D, Sholler G. “Congenital heart health”: how psychological care can make a difference. Med J Aust. 2016;205(3):104‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasparian N, Kan J, Sood E, et al. Mental health care for parents of babies with congenital heart disease during intensive care unit admission: systematic review and statement of best practice. Early Hum Dev. 2019;139:104837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tesson S, Butow P, Sholler G, et al. Psychological interventions for people affected by childhood-onset heart disease: a systematic review. Health Psychol. 2019;38(2):151‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearney JA, Salley CG, Muriel AC. Standards of psychosocial care for parents of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(Suppl 5):S632‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinosa KM, Julian M, Wu Y, Lopez C, Donofrio MT, Krishnan A, et al. “The mental health piece is huge”: perspectives on developing a prenatal maternal psychological intervention for congenital heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2021. 10.1017/S1047951121004030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(7):509‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Czajkowski S, Powell L, Adler N, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34(10):971‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J. 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flynn R, Walton S, Scott SD. Engaging children and families in pediatric health research: a scoping review. Res Involv Engagem. 2019;5:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox ED, Jacobsohn GC, Rajamanickam VP, et al. A family-centered rounds checklist, family engagement, and patient safety: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):e20161688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shelef DQ, Rand C, Streisand R, et al. Using stakeholder engagement to develop a patient-centered pediatric asthma intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1512‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michelson KN, Frader J, Sorce L, et al. The process and impact of stakeholder engagement in developing a pediatric intensive care unit communication and decision-making intervention. J Patient Exp. 2016;3(4):108‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckert A, Forsythe LP, Carman KL, et al. Researchers, patients, and other stakeholders’ perspectives on challenges to and strategies for engagement. Res Involv Engagem. 2020;6:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forrest CB Margolis PA Bailey LC, Marsolo K, Del Beccaro MA, Finkelstein JA, et al. PEDSnet: a National Pediatric Learning Health System. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):602‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Financial compensation of patients, caregivers, and patient/caregiver organizations engaged in PCORI-funded research as engaged research partners. June 10, 2015. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Compensation-Framework-for-Engaged-Research-Partners.pdf

- 32.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Department of Health and Human Services: Food and Drug Administration & Office for Human Research Protections. (2016, December 15). Use of electronic informed consent—questions and answers. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-12-15/pdf/2016-30146.pdf

- 34.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brabham DC. Crowdsourcing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sood E Wysocki T Alderfer M, Aroian K, Christofferson J, Karpyn A, et al. Crowdsourcing as a novel approach to qualitative research. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021;46(2):189‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Appl Prev Psychol. 2005;11(3):141‐56. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, et al. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hahn EA, Devellis RF, Bode RK, et al. Measuring social health in the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): item bank development and testing. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(7):1035‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salsman JM, Schalet BD, Merluzzi TV, et al. Calibration and initial validation of a general self-efficacy item bank and short form for the NIH PROMIS®. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(9):2513‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salsman JM Schalet BD Park CL, George L, Steger MF, Hahn EA, et al. Assessing meaning & purpose in life: development and validation of an item bank and short forms for the NIH PROMIS®. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(8):2299‐310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyon AR, Lau AS, McCauley E, et al. A case for modular design: implications for implementing evidence-based interventions with culturally-diverse youth. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2014;45(1):57‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, et al. Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(6):446‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lion KC, Raphael JL. Partnering health disparities research with quality improvement science in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):354‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasparian NA, Sadhwani A, Sananes R, et al. Telehealth services for cardiac neurodevelopmental care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a site survey. Cardiol Young. 2022. 10.1017/S1047951122000579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrera M, Jr, Castro FG, Strycker LA, et al. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: a progress report. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81(2):196‐205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pina AA, Polo AJ, Huey SJ. Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for ethnic minority youth: the 10-year update. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48(2):179‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nurjannah I, Mills J, Park T, et al. Conducting a grounded theory study in a language other than English: procedures for ensuring the integrity of translation. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1). 10.1177/2158244014528920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-jpx-10.1177_23743735221092488 for Partnering With Stakeholders to Inform the Co-Design of a Psychosocial Intervention for Prenatally Diagnosed Congenital Heart Disease by Erica Sood, Colette Gramszlo, Alejandra Perez Ramirez, Katherine Braley, Samantha C Butler, Jo Ann Davis, Allison A Divanovic, Lindsay A Edwards, Nadine Kasparian, Sarah L Kelly, Trent Neely, Cynthia M Ortinau, Erin Riegel, Amanda J Shillingford and Anne E Kazak in Journal of Patient Experience