Abstract

For an in vitro mutant of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected on moxifloxacin four- to eightfold-increased MICs of new fluoroquinolones, only a twofold-increased MIC of ciprofloxacin, and a twofold-decreased MIC of novobiocin were observed. This phenotype was conferred by two mutations: Ser81Phe in GyrA and a novel undescribed His103Tyr mutation in ParE, outside the quinolone resistance-determining region, in the putative ATP-binding site of topoisomerase IV.

Clinical isolates resistant to new fluoroquinolones (FQs) have been described (6, 15, 16, 17, 19), and in vitro mutants with cross-resistance to all FQs have been selected by various FQs (15, 19, 21–23, 26). FQ resistance is mediated either by active efflux (4, 7, 31) or, as the main mechanism, by alteration of two closely related type II topoisomerases, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, which regulate DNA topology using free energy derived from ATP hydrolysis (11). Gyrase is composed of two GyrA and two GyrB subunits, and topoisomerase IV is composed of two ParC and two ParE subunits; the GyrA and ParC subunits contain the catalytic sites of the topoisomerases (18), while GyrB and ParE catalyze the hydrolysis of ATP (1, 5, 11). Mutations in these enzymes are located mostly in the so-called quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of subunit A of gyrase, between amino acids 67 and 106 (Escherichia coli numbering [30]), and in the homologous region of the ParC subunit of topoisomerase IV (13). Different mutations in ParE of FQ-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, Arg447Ser, Glu474Lys, and Asp435Asn, have been described, but only the last has been demonstrated to confer low-level resistance (10, 17, 24). We report here a new mutation in the N-terminal region of ParE (outside the QRDR), which leads to a particular phenotype of resistance.

In vitro one-step mutants were selected on 0.5 μg of moxifloxacin (Bayer Pharma, Puteaux, France) per ml from the FQ-susceptible pneumococcal clinical isolate 5714. They showed (Table 1) two different phenotypes. 5714-M1 (M1), which was selected at a frequency of ca. 10−8, showed a 2-fold increase in the MIC of moxifloxacin and 4-fold increases in the MICs of sparfloxacin (Rhône-Poulenc Rorer, Vitry-sur-Seine, France) and grepafloxacin (GlaxoWellcome, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France); 5714-M2 (M2), which was selected at a frequency of less than 10−9, was characterized by a 4-fold increase in the MIC of moxifloxacin and a 16-fold increase in the MICs of sparfloxacin and grepafloxacin but also by a reproducible 2-fold decrease in the MIC of novobiocin. Interestingly, no change in the MICs of pefloxacin and at most twofold increases in the MICs of ciprofloxacin were observed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

MICs of tested FQs for strains used in this study and amino acid changes found in topoisomerase subunits

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

Amino acidb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEF | CIP | MXF | SPX | GRX | NOV | GyrA | ParE | |

| 5714 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | Ser81 | His103 |

| 5714-M1 (M1) | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | Phe81 | His103 |

| 5714-M2 (M2) | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.125 | Phe81 | Tyr103 |

| R6 | 8 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | Ser81 | His103 |

| R6M1 | 8 | ND | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Phe81 | His103 |

| R6gyrA-M1 or R6gyrA-M2 | 8 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | ND | Phe81 | His103 |

| LL-R6M2 | 8 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | Phe81 | His103 |

| HL-R6M2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | Phe81 | Tyr103 |

| R6gyrA-M2/parE-M2 | ND | ND | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | Phe81 | Tyr103 |

PEF, pefloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; MXF, moxifloxacin; SPX, sparfloxacin; GRX, grepafloxacin; NOV, novobiocin; ND, not determined.

In order to determine the number of determinants implicated in the acquisition of resistance, we transformed the susceptible S. pneumoniae laboratory strain R6 with DNAs from the mutants M1 and M2, as previously described (15). Transformants (R6M1; Table1) with the same phenotype as that of the donor strain were obtained on sparfloxacin or grepafloxacin (0.40 μg/ml) at high frequency (3 × 10−2) with DNA from M1, suggesting that resistance in the mutant M1 was due to one mutation. In contrast, using DNA from M2, we selected two different types of transformants: first, at a frequency of 5 × 10−2 on sparfloxacin or grepafloxacin (0.40 μg/ml), a population expressing the same low-level resistance as M1 (LL-R6M2); second, at a frequency of 10−5 on sparfloxacin or grepafloxacin (1 μg/ml), a population expressing the same high-level resistance as M2 (HL-R6M2). These results suggested that resistance in M2 was due to two mutations located in two independent genes. To explore these mutations further, we amplified the entire gene of either the topoisomerase subunit GyrA, GyrB, ParC, or ParE from M1 and M2 using the following pairs of primers: SPgyrA1 (5′-TTTAGTGGTTTAGAGGCTGA-3′, positions −81 to −62 before the ATG start codon) and SPgyrA3 (5′-CTGCTAGGATATTTGTCAG-3′, positions +64 to +45 after the stop codon) for gyrA (3), PNC4 (5′-CGGAATTCGCAGGACTTGATACCC-3′, positions −85 to −62 before ATG) and PNC5 (5′-CGGGATCCATGGTTGTTTCC-3′, positions +1807 to +1788 in the gyrB gene) for gyrB (20), PNC12 (5′-AGCGGCTAAGACACAAACT-3′, positions −267 to −249 before ATG) and PNC20 (5′-TTCTCCAATAAAAACCAGC-3′, positions +50 to +32 after the stop codon) for parC (21), and SPparE1 (5′-CTGCTGAAATTGTCACATC-3′, positions −92 to −74 before ATG) and SPparE2 (5′-GTCATTCACATCCGACTCT-3′, positions +53 to +35 after the stop codon) for parE (21).

In a first set of experiments, we transformed the susceptible strain R6 with these amplified fragments. Resistant transformants with the M1 phenotype were obtained only with the gyrA fragment from M1 (R6gyrA-M1) and M2 (R6gyrA-M2) (frequency of 5 × 10−3), suggesting again that one mutation in gyrA was responsible for the low-level resistance. Indeed, sequencing of the QRDRs of the gyrA genes from these strains (M1, M2, R6gyrA-M1, and R6gyrA-M2, as well as LL-R6M2) using the primer PNC7 (15) revealed a single transition, TCC→TTC, leading to the Ser81Phe change (S. pneumoniae numbering [3]) (Table 1). Sequencing of the QRDRs of gyrB, parC, and parE from these strains using the primers PNC8 (15), PNC11 (15), and PNC17 (5′-GAAGGTTCAGACTATCGTG-3′), respectively, revealed no mutation.

In a second set of experiments, using R6gyrA-M2 as the recipient strain, transformants expressing the M2 phenotype (R6gyrA-M2/parE-M2) (Table 1) were obtained with the whole parE fragment from M2 at a frequency of 5 × 10−3 but not with the fragment restricted to the QRDR covering amino acids 316 to 565 (amplified with the oligonucleotides PNC16 [5′-GAAGGTTCAGACTATCGTG-3′] and PNC17) or with the C-terminal region of parE (amplified with the oligonucleotides PNC17 and PNC11 [15]). These results suggested that the second mutation in M2 was localized in the N-terminal region of ParE. This was confirmed by sequencing the N-terminal parE region from M2 and HL-R6M2 using the oligonucleotides SPparE1 and SPparE3 (5′-TTGTAAACTGCGCCATCAC-3′), which revealed a transition, CAT→TAT, leading to the His103Tyr change (Table 1), and by transformation of R6gyrA-M1 to the M2 phenotype (frequency of 10−4) using the same N-terminal parE region. Adversely, no FQ-resistant transformant could be selected using the whole parE fragment as the donor, the susceptible R6 strain as the recipient, and the following selectors: sparfloxacin or grepafloxacin (0.40, 0.50, or 0.75 μg/ml), moxifloxacin (0.25 or 0.5 μg/ml), and ciprofloxacin (1.25 or 1.5 μg/ml).

We have selected from a susceptible clinical strain of S. pneumoniae one-step mutants on moxifloxacin with two different phenotypes. The mutant 5714-M1 showed a low level of resistance to FQs due to the classical Ser81Phe change in GyrA previously described for mutants obtained on sparfloxacin (23, 27), suggesting as proposed by Varon et al. (27) that moxifloxacin could also target the gyrase. This could be explained by the particular structure of its C-7 residue, as suggested by Alovero et al. (2). The second mutant, 5714-M2, which showed a higher level of resistance to some FQs, had two modified targets with the same GyrA Ser81Phe change as in M1 and a new undescribed mutation, His103Tyr, localized outside the QRDR in the N-terminal region of ParE. The His103Tyr mutation in ParE combined with the Ser81Phe mutation in GyrA led not only to higher FQ resistance but also to a reproducible twofold increase in novobiocin susceptibility.

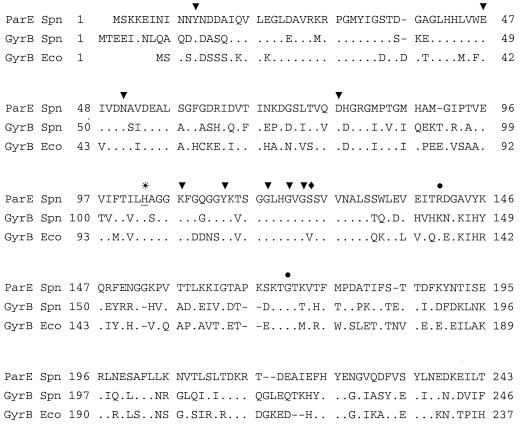

ParE, which shows 50% identity to GyrB of S. pneumoniae (20), with up to 61% identity in its N-terminal domain, also shows 54% identity to GyrB of E. coli. Many conserved amino acids, which in GyrB of E. coli are involved in the ATPase site and the coumarin-binding domain (28), also lie in the N-terminal domain of ParE (Fig. 1). The position Lys103, which in GyrB of E. coli has been demonstrated to be important for ATP binding (25), is equivalent in S. pneumoniae to Lys110 in GyrB and Lys107 in ParE. Other positions in the N-terminal domain of GyrB were shown to be involved in coumarin resistance, in particular, substitution of Arg136 in E. coli (equivalent to Arg140 in ParE) and Ser127 in S. pneumoniae (equivalent to Ser124 in ParE), but they did not confer resistance to FQs (9, 20). Therefore, the His103Tyr substitution, which lies near the coumarin-binding site, may alone be responsible for the increase in susceptibility to novobiocin in M2. However, this was not demonstrated using transformation since more susceptible transformants could not be easily selected.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the ParE region from S. pneumoniae (Spn) with the GyrB regions from S. pneumoniae and E. coli (ECO) involved in ATP binding or hydrolysis. ▾, residues of GyrB from E. coli involved in ATP binding or hydrolysis (9); ●, residues of GyrB from E. coli involved in coumarin resistance (20); ⧫, residue of GyrB from S. pneumoniae involved in coumarin resistance (20); ∗, residue of ParE (underlined) involved in the new phenotype of FQ resistance described in this paper.

The mechanism by which the ParE mutation His103Tyr increases the resistance to FQs is unknown. It may be a consequence of a modification of the quinolone-binding pocket of the topoisomerases, as proposed for mutations in the QRDRs of GyrA and ParC (18, 29) and from structural studies which suggest that, in a certain conformation, the QRDRs of GyrA and GyrB may be in proximity (12). However, it is difficult to assess if position 103, located near the ATP-binding site of the enzyme, is close to the QRDR of ParE. Our hypothesis concerning the role of the His103Tyr mutation in ParE is that it modified the environmental electric charges and, therefore, may impair the function of the enzyme. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that His99 of E. coli GyrB, equivalent in S. pneumoniae to His107 of GyrB and His103 of ParE, is an important residue for the stabilization of the dimer structure of GyrB in the presence of ATP. This residue, in association with others from the same loop (residues 99 to 117), is part of a larger network which participates in intra- and intermolecular interactions between the two subunits (8). A His103Tyr substitution may impair ATP hydrolysis and, subsequently, the turnover of the enzyme during the catalytic process of DNA.

Moxifloxacin selects for ParE mutants that are different from those previously described in which a mutation at position 435 in ParE was associated with increases in the MICs of pefloxacin and ciprofloxacin, leading to a higher level of resistance when this mutation is associated with a GyrA mutation at position 81 (24). Indeed, this was not the case for the mutants we obtained since with the entire parE gene as the DNA donor, no transformant could be selected on FQ from R6, and almost no increase in the MICs of pefloxacin and ciprofloxacin was observed for both mutants M1 and M2. This finding suggests that the His103Tyr mutation in ParE either is lethal alone or, more likely, confers FQ resistance only when associated with a gyrA mutation. Therefore, mechanisms leading to resistance might be very different according to the FQ. In this matter, it is noteworthy that Fournier and Hooper (14) have obtained an FQ-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus with a mutation in GrlA (ParC) at position Ala116, close to the active site Tyr119 and outside the quinolone-binding pocket of the enzyme. This mutation, also believed to impair the activity of topoisomerase IV, led to an increase in FQ resistance and a twofold increase in novobiocin susceptibility. Nevertheless, the correlation between impairment of catalytic activity of topoisomerase IV and increase in resistance to some FQs remains to be elucidated. Finally, as far as the selection of this particular His103Tyr ParE substitution is concerned, it may be related to a structural feature of the moxifloxacin molecule which may show unusual links to the ParE domain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) (CRI 950601 and EMI 0004).

We thank C. Harcour for secretarial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali J A, Jackson A P, Howells A J, Maxwell A. The 43-kilodalton N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein hydrolyses ATP and binds coumarin drugs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2717–2724. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alovero F L, Pan X S, Morris J E, Manzo R H, Fisher L M. Engineering the specificity of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: benzenesulfonamide modifications at C-7 of ciprofloxacin change its primary target in Streptococcus pneumoniae from topoisomerase IV to gyrase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:320–325. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.320-325.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balas D, Fernandez-Moreira E, de la Campa A G. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding the DNA gyrase A subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2854–2861. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2854-2861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranova N N, Neyfakh A A. Apparent involvement of a multidrug transporter in the fluoroquinolone resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1396–1398. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.6.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger J M, Gamblin S J, Harrison S C, Wang J C. Structure and mechanism of DNA topoisomerase II. Nature. 1996;379:225–232. doi: 10.1038/379225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard L, Nguyen Van J-C, Mainardi J-L. In vivo selection of Streptococcus pneumoniae, resistant to quinolones, including sparfloxacin. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1994;1:60–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenwald N P, Gill M J, Wise R. Prevalence of a putative efflux mechanism among fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2032–2035. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brino L, Urzhumtsev A, Mousli M, Bronner C, Mitschler A, Oudet P, Moras D. Dimerization of Escherichia coli DNA-gyrase B provides a structural mechanism for activating the ATPase catalytic center. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9468–9475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contreras A, Maxwell A. gyrB mutations which confer coumarin resistance also affect DNA supercoiling and ATP hydrolysis by Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1617–1624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies T A, Pankuch G A, Dewasse B E, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. In vitro development of resistance to five quinolones and amoxicillin-clavulanate in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1177–1182. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377–392. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fass D, Bogden C E, Berger J M. Quaternary changes in topoisomerase II may direct orthogonal movement of two DNA strands. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:322–326. doi: 10.1038/7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Lagneaux D, Crouzet J, Famechon A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fournier B, Hooper D C. Effects of mutations in GrlA of topoisomerase IV from Staphylococcus aureus on quinolone and coumarin activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2109–2112. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janoir C, Zeller V, Kitzis M-D, Moreau N J, Gutmann L. High-level fluoroquinolone-resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2760–2764. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones M E, Sahm D F, Martin N, Scheuring S, Heisig P, Thornsberry C, Kohrer K, Schmitz F J. Prevalence of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE mutations in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with decreased susceptibilities to different fluoroquinolones and originating from Worldwide Surveillance Studies during the 1997-1998 respiratory season. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:462–466. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.462-466.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorgensen J H, Weigel L M, Ferraro M J, Swenson J M, Tenover F C. Activities of newer fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates including those with mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE loci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:329–334. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morais Cabral J H, Jackson A P, Smith C V, Shikotra N, Maxwell A, Liddington R C. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. Nature. 1997;388:903–906. doi: 10.1038/42294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz R, de la Campa A G. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz R, Bustamante M, de la Campa A G. Ser-127-to-Leu substitution in the DNA gyrase B subunit of Streptococcus pneumoniae is implicated in novobiocin resistance. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4166–4170. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4166-4170.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae encoding DNA topoisomerase IV: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4060–4069. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4060-4069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan X-S, Ambler J, Mehtar S, Fisher L M. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2321–2326. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan X-S, Fisher L M. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:471–474. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perichon B, Tankovic J, Courvalin P. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1166–1167. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamura J K, Gellert M. Characterization of the ATP binding site on Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21342–21349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varon E, Janoir C, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L. ParC and GyrA may be interchangeable initial targets of some fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:302–306. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wigley D B, Davies G J, Dodson E J, Maxwell A, Dodson G. Crystal structure of an N-terminal fragment of the DNA gyrase B protein. Nature. 1991;351:624–629. doi: 10.1038/351624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willmott C J R, Maxwell A. A single point mutation in the DNA gyrase A protein greatly reduces binding of fluoroquinolones to the gyrase-DNA complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:126–127. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida H, Bogaki M, Nakamura M, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1271–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeller V, Janoir C, Kitzis M-D, Gutmann L, Moreau N J. Active efflux as a mechanism of resistance to ciprofloxacin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1973–1978. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]