Summary

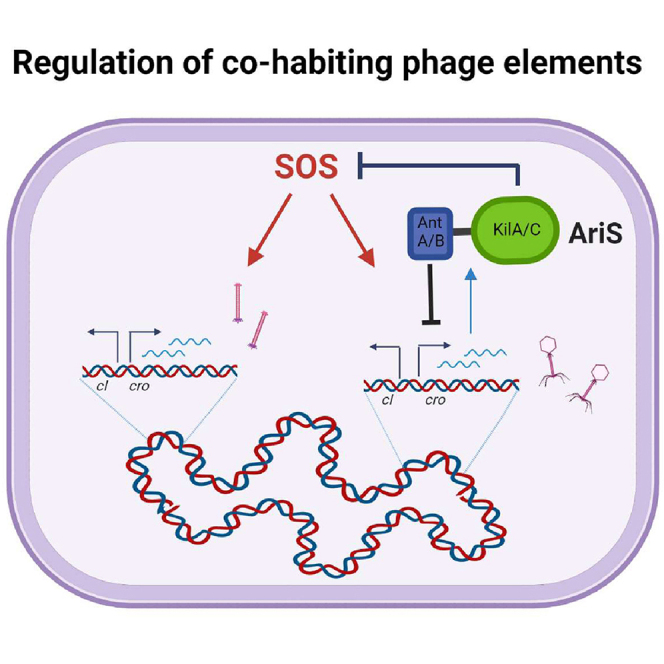

Listeria monocytogenes strain 10403S harbors two phage elements in its chromosome; one produces infective virions and the other tailocins. It was previously demonstrated that induction of the two elements is coordinated, as they are regulated by the same anti-repressor. In this study, we identified AriS as another phage regulator that controls the two elements, bearing the capacity to inhibit their lytic induction under SOS conditions. AriS is a two-domain protein that possesses two distinct activities, one regulating the genes of its encoding phage and the other downregulating the bacterial SOS response. While the first activity associates with the AriS N-terminal AntA/AntB domain, the second associates with its C-terminal ANT/KilAC domain. The ANT/KilAC domain is conserved in many AriS-like proteins of listerial and non-listerial prophages, suggesting that temperate phages acquired such dual-function regulators to align their response with the other phage elements that cohabit the genome.

Keywords: bacteriophage, Listeria monocytogenes, SOS response, ant, KilAC, lysogeny, phage, pathogen

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Listeria monocytogenes strain 10403S harbors two phage elements in its chromosome

-

•

The lytic response of the phage elements is synchronized under SOS conditions

-

•

AriS, a dual-function phage regulator, fine-tunes the elements’ response under SOS

-

•

Aris regulates both its encoding phage and the bacterial SOS response

Azulay et al. describe a phage factor that regulates cohabiting phage elements by controlling the bacterial SOS response.

Introduction

Most bacterial pathogens, and bacteria in general, are lysogens, namely, they carry prophages within their genome; in many cases, they carry more than one (Burns et al., 2015; Casjens, 2003). Under stress conditions, the prophages can switch into the lytic cycle, producing infective virions that are released via bacterial lysis, a process referred to as phage induction (Oppenheim et al., 2005). In λ phage, it was shown that this induction is achieved by inactivation of the phage main repressor (the CI repressor), a process that is linked to the bacterial SOS response (Ptashne, 2004). The SOS response is triggered upon severe DNA damage caused, for example, by ultraviolet (UV) irradiation or chemical reagents (e.g., mitomycin C) and is regulated by RecA and LexA (Kreuzer, 2013; Ptashne, 2004; Sutton et al., 2000). RecA binds to single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) at the site of the lesion, forming active RecA-ssDNA complexes (RecA∗) that then trigger the autocleavage of LexA, the main repressor of the SOS genes, thereby activating the SOS response (including, for example, umuC, umuD, uvrA, and lexA and recA themselves) (Little, 1991). Notably, RecA∗ complexes were also shown to trigger the autocleavage of phage repressors, particularly those that share some structural homology with LexA, such as the CI repressor of λ phage, thus triggering phage induction under SOS conditions (Ptashne, 2004; Casjens and Hendrix, 2015). While this mechanism of repressor inactivation was originally identified in lambdoid phages, it is now evident that additional mechanisms exist in lambdoid and non-lambdoid phages that involve anti-repressor proteins that either cleave the main phage repressor, inhibit it via direct binding, or compete with its binding to DNA (Argov et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2016; Lemos Rocha and Blokesch, 2020; Mardanov and Ravin, 2007; Silpe et al., 2020). Importantly, these anti-repressors were still shown to be linked to the SOS response, indicating an intimate interaction between temperate phages and the bacterial SOS system.

The role of the SOS system in phage induction is even more intriguing when considering polylysogenic strains, whose genomes carry multiple prophages and phage-derived elements that can independently trigger bacterial lysis (Davies et al., 2016). In such strains, the SOS system essentially induces all the phage elements that inhabit the genome, activating their lytic cycles and, hence, bacterial killing (Burns et al., 2015). While this scenario may trigger a direct competition between neighboring phage elements (i.e., for the production of progeny), a competition that can lead to the loss of some of them, it can also lead to the development of inter-phage cross-regulatory interactions that support their coexistence. In this regard, previous studies from our group identified such an inter-phage cross-regulatory interaction in the human bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) (Argov et al., 2019; Pasechnek et al., 2020; Rabinovich et al., 2012).

Lm is a saprophyte and a facultative intracellular pathogen that invades a wide array of mammalian cells, including immune cells (Freitag et al., 2009). It resides in the soil and on food products and infects humans via the consumption of contaminated food. Upon traveling to the gut, the bacteria can colonize the intestine and translocate across the epithelial barrier into the lamina propria and invade phagocytic cells such as macrophages (Cossart, 2011). Upon invasion, the bacteria are initially found in phagosomes, from which they escape into the host cell cytosol in order to replicate (Portnoy et al., 2002). Notably, most Lm strains carry prophages and phage-derived elements in their genome, yet the interaction between these elements and their impact on Lm survival in the mammalian environment, are not well understood. Previous studies from our group discovered that Lm strain 10403S carries two lytic phage elements in its chromosome, which are perfectly adapted to the pathogenic lifestyle of this bacterium (Argov et al., 2019; Pasechnek et al., 2020; Rabinovich et al., 2012). The first element is an infective prophage of the Siphoviridae family (φ10403S) that is integrated within the comK gene, and the other is a highly conserved cryptic phage element that encodes phage tail-like bacteriocins (tailocins), named monocins (Argov et al., 2017b; Lee et al., 2016; Rabinovich et al., 2012; Zink et al., 1995). Under SOS conditions, the two phage elements are simultaneously activated, producing virions and monocins that are released via bacterial lysis, independently driven by each phage element (Argov et al., 2019). Interestingly, upon Lm infection of macrophage cells, the two phage elements are also activated, although their lytic pathway is arrested halfway (i.e., their late genes encoding structural and lysis proteins are not expressed), thereby avoiding the production of virions and monocins, as well as bacterial lysis in the intracellular niche (Argov et al., 2019; Pasechnek et al., 2020). This partial response of the phage elements was shown to promote the excision of φ10403S from the comK gene, yielding an intact comK gene that produces a functional ComK protein (Pasechnek et al., 2020; Rabinovich et al., 2012). In Bacillus subtilis, ComK functions as the activator of the competence system (the com genes) (Dubnau, 1999), yet it was considered non-functional in Lm owing to the phage insertion. Further experiments uncovered that upon Lm invasion into macrophage cells, the phage excises its genome, resulting in the expression of ComK, which in turn activates the expression of the com genes, some of which were found to promote Lm escape from the macrophage phagosome, to the cytosol (i.e., comG and comEC) (Rabinovich et al., 2012). During Lm replication in the macrophage cytosol, the phage DNA, which is maintained as an episome, was found to integrate back into comK, thereby shutting off its transcription in the cytosolic niche (Pasechnek et al., 2020). While these findings revealed an intriguing bacteria-phage adaptive behavior that supports the survival of the bacterial host in the mammalian environment, they further demonstrated that prophages can serve as regulatory switches of bacterial genes via a mechanism of excision and re-integration, a phenomenon named active lysogeny (Argov et al., 2017a; Feiner et al., 2015).

It was recently demonstrated by our group that φ10403S is tightly linked to the monocin (mon, in short) element (Argov et al., 2019). Bioinformatic and experimental data uncovered that φ10403S lost its main anti-repressor and became fully dependent on the anti-repressor of the mon element, a metalloprotease named MpaR. MpaR was shown to simultaneously cleave the CI-like repressors of both elements, thereby synchronizing their lytic induction under SOS conditions and during Lm infection of macrophage cells. While the evolutionary forces that drove this inter-phage cross-regulatory interaction remain unclear, this finding implied an intimate interaction between φ10403S and the mon element that requires their coordination. In light of this premise, we hypothesized that the two phage elements further “communicate” via ancillary interactions that balance or align their lytic pathways. To address this hypothesis, we searched for φ10403S genes that concomitantly affect the lytic pathway of the two phage elements under SOS conditions. Using this approach, we identified a phage regulator, named here AriS, that has the capacity to control the phage elements via regulation of the bacterial SOS response.

Results

φ10403S encodes a protein that blocks the production of virions and monocins

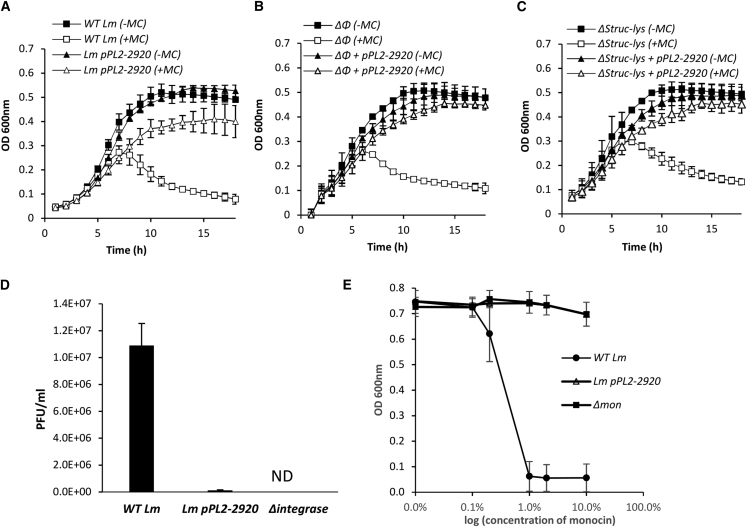

In a search for φ10403S genes that concomitantly affect the lytic pathway of φ10403S and mon, we ectopically expressed specific phage genes, mostly early genes with unknown function, and examined their impact on the elements’ lytic response under SOS. To this end, each gene was cloned into the integrative pPL2 plasmid, under the control of a Tet repressor (TetR)-regulated promoter (PTetR), and introduced into Lm strain 10403S (wild-type [WT] Lm). Bacteria expressing each gene were grown in rich brain heart infusion (BHI) medium and subjected to mitomycin C (MC) treatment to trigger phage and mon induction. It was previously demonstrated that under MC treatment, the bacteria undergo lysis, which is independently driven by each phage element (Argov et al., 2017b, 2019). When monitoring for bacterial lysis under MC treatment, it was noted that a strain overexpressing the early gene LMRG_02920 (annotated in public databases as a putative phage anti-repressor) failed to undergo bacterial lysis like WT Lm (Figure 1A). To examine whether LMRG_02920 expression indeed inhibits bacterial lysis that is driven by each phage element independently, the gene was expressed in bacteria that were cured of φ10403S-phage (Δφ) or that were deleted of the mon structural and lysis genes (Δstruc-lys mutant), and lysis of these bacteria under MC treatment was then evaluated. Ectopic expression of LMRG_02920 effectively prevented bacterial lysis that was driven by each phage element in an independent manner (Figures 1B and 1C). In accordance, expression of LMRG_02920 was associated with reduced virion and monocin release, as determined using a plaque-forming assay and a monocin killing assay, respectively (Figures 1D and 1E). In these experiments, a mutant deleted of φ10403S integrase gene (Δint, which fails to produce infective virions) and a mutant deleted of the mon element (Δmon) were used as controls. Taken together, these findings demonstrated that φ10403S encodes an early protein that has the capacity to concomitantly block the lytic pathway of the two phage elements.

Figure 1.

Ectopic expression of LMRG_02920 inhibits the production of virions and monocins

(A–C) Growth analysis of WT L. monocytogenes (Lm) (A) and mutants harboring deletions of the φ10403S-prophage (Δφ) (B) or of the structurallysis module of the monocin element (LMRG_02368-0278, ΔStruc-lys) (C) with or without ectopic expression of LMRG_02920 from pPL2-plasmid (pPL2-2920). Bacteria were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium in the presence (+) or absence (-) of MC at 30°C. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments and are sometimes hidden by the symbols.

(D) A plaque-forming assay (PFU) of WT Lm, WT Lm overexpressing LMRG_02920 (pPL2-2920), and a mutant deleted of the φ10403S integrase gene (LMRG_01511, Δintegrase) as a control. Virions obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment) were tested on the indicator Lm strain Mack861 for plaque formation (numerated PFUs). The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(E) A monocin killing assay performed with monocins obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment) of WT Lm, Lm over-expressing LMRG_02920 (pPL2-2920) and a mutant lacking the mon element (Δmon), as a control. A diluted overnight culture of the indicator Lm strain ScottA was supplemented with serial dilutions of filtered supernatants containing monocins and grown at 30°C. Optical density (OD)600 was measured after 10 h. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

LMRG_02920 inhibits the induction of the two phage elements under SOS

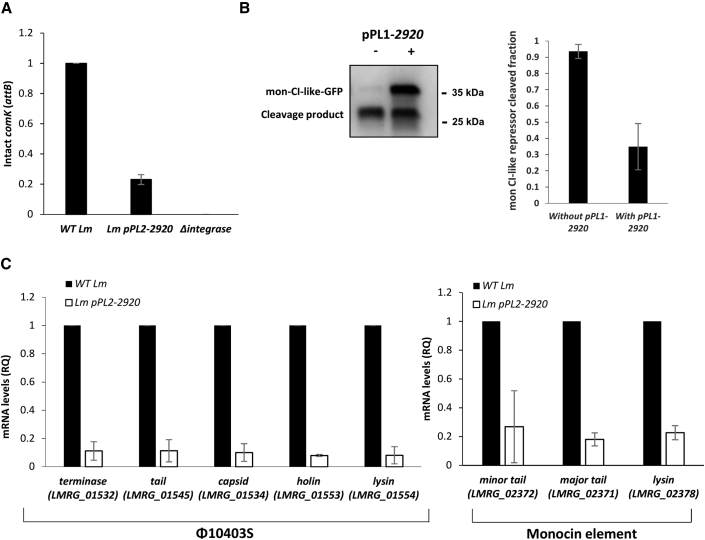

Having discovered this role of LMRG_02920, we tried to relate it to previous data published by our group, characterizing a mutant deleted of this gene (ΔLMRG_02920) (Pasechnek et al., 2020). ΔLMRG_02920 was shown to exhibit reduced production of virions (∼60% less) and a differential transcription profile of the phage compared with WT Lm. More specifically, late into the lytic pathway (i.e., 4–5 h post induction), it demonstrated a high transcription of the early genes and a low transcription of the late genes, suggesting that it coordinates the transcription of the phage in the course of the lytic pathway (i.e., tuning down the early genes while upregulating the late genes). While the low production of virions accorded with the low transcription of the late genes, the mechanism by which LMRG_02920 differentially regulated the phage early- and late-lytic gene modules remained unclear. To gain a better understanding of LMRG_02920 activity, we next aimed to decipher how it inhibits the lytic pathway of the two phage elements. We first investigated whether LMRG_02920 interferes with early stages of induction. Quantitative real-time PCR analyses indicated that ectopic expression of LMRG_02920 largely prevented phage excision, as determined by quantification of the formation of intact comK genes (the phage attB site), demonstrating that it holds the capacity to attenuate the induction of the phage (Figure 2A). To examine whether this is also the case with the mon element, we evaluated its induction by monitoring the cleavage of its CI-like repressor (LMRG_02363) by MpaR, using an in vivo system that was previously designed (Argov et al., 2019). In this system, the mon CI-like repressor was fused to GFP and coexpressed with MpaR from pPL2 plasmid (pPL2-mon-cI-gfp-mpaR) in a strain deleted of both phage elements (Δφ/Δmon). LMRG_02920 was then introduced into this strain using the pPL1 integrative plasmid (pPL1-2920), and cleavage of the mon CI-like repressor was monitored during bacterial growth in the presence of MC. The full-length repressor and its cleavage product were detected and quantified using anti-GFP antibodies on western blots. Comparison of the cleaved fraction of the mon CI-like repressor in bacteria expressing versus not expressing LMRG_02920 indicated that LMRG_02920 inhibits the cleavage of the mon CI-like repressor (Figure 2B, right panel). Of note, the western blots also demonstrated that the full-length CI-like repressor accumulates in LMRG_02920-expressing bacteria, indicating that LMRG_02920 somehow stabilizes the mon CI-like repressor (Figure 2B, left panel). To corroborate these findings, we analyzed the transcription level of representative phage and mon genes (e.g., genes encoding capsid, tail, and lysis proteins) under MC treatment in bacteria expressing or not expressing LMRG_02920. In line with the observation that ectopic expression of LMRG_02920 prevented the induction of the two phage elements, their corresponding genes were not expressed (Figure 2C). These results demonstrated that LMRG_02920 holds the capacity to inhibit the induction of the two phage elements.

Figure 2.

LMRG_02920 inhibits the lytic induction of the phage and the mon element

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the intact comK gene (representing φ10403S attB site) in WT Lm, Lm bacteria harboring pPL2-2920, and a mutant deleted of the φ10403S integrase gene (Δintegrase) as a control. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. The data are presented as relative quantity (RQ) relative to the levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(B) Analysis of mon CI-like repressor cleavage by MpaR in the presence or absence of coexpression of LMRG_02920. Δφ/Δmon bacteria harboring a pPL2 plasmid expressing a translational fusion of mon CI-like-GFP under the Pconst promoter and MpaR under the PTetR promoter (pPL2-mon-cI-gfp-mpaR) were used in this experiment. This strain was also conjugated with the integrative pPL1 plasmid expressing LMRG_02920 under the PTetR promoter (pPL1-2920). To detect the in vivo cleavage of the mon CI-like repressor, equal amounts of total proteins from bacteria grown in the presence of MC were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE, blotted, and probed with anti-GFP antibody on western blots (a representative blot is shown in the left panel). Using ImageJ software, the amounts of the cleaved and non-cleaved mon CI-like repressors were quantified, and the mon CI-like cleaved fraction was calculated (right panel). The experiment was performed three times; error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of select late-lytic genes of φ10403S (left panel) and the mon element (right panel) in WT Lm and Lm bacteria expressing LMRG_02920 (using pPL2-2920). Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

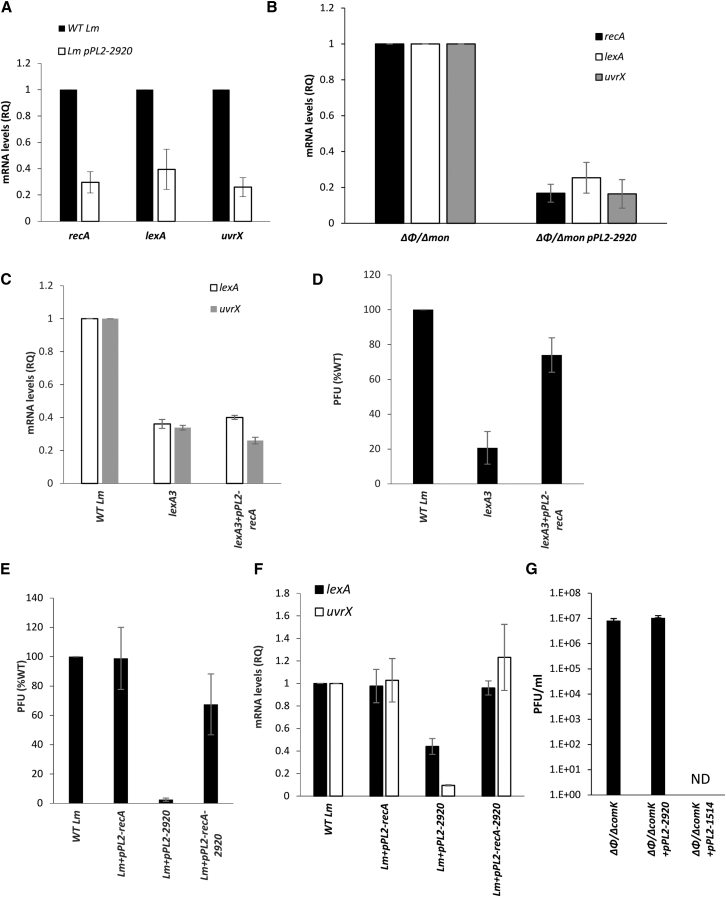

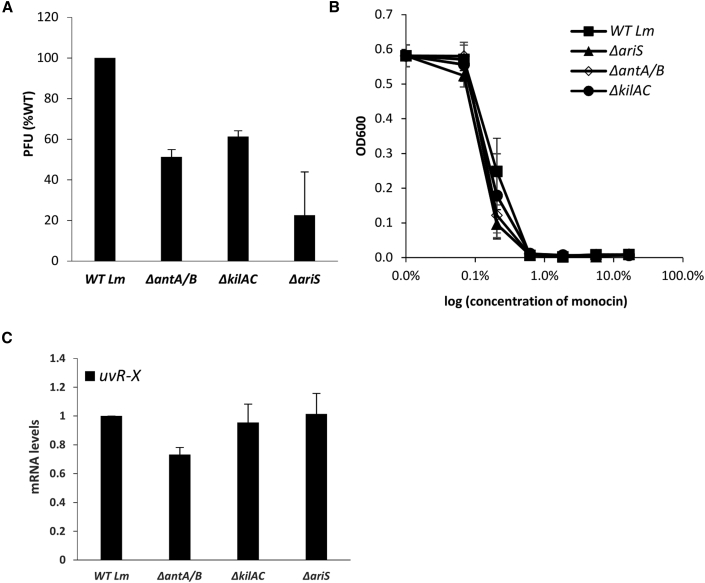

LMRG_02920 inhibits the bacterial SOS response

Given the observation that overexpression of LMRG_02920 inhibits the induction of the two phage elements, we hypothesized that it either interferes with MpaR activity, or operates upstream of MpaR, by inhibiting the bacterial SOS response. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we examined whether LMRG_02920 has any effect on the induction of SOS response. The transcription levels of key SOS genes, i.e., lexA, recA, and uvrX, were analyzed under MC treatment in bacteria expressing or not expressing LMRG_02920. As shown in Figure 3A, the transcription level of the SOS genes was significantly reduced (by >60%) in bacteria expressing LMRG_02920, demonstrating that this protein downregulates the SOS response. Notably, a similar downregulation of the SOS genes was observed in Δφ/Δmon bacteria expressing LMRG_02920 (Figure 3B), indicating that this activity of LMRG_02920 is independent of the phage elements. In light of these observations, we speculated that LMRG_02920 targets RecA or LexA, thereby preventing the induction of the SOS response and the induction of the phage elements. To address this hypothesis, we first investigated the role of LexA and RecA in the induction of the phage elements under MC treatment. For this purpose, we used a lexA3 mutant that encodes a non-cleavable variant of LexA (i.e., insensitive to RecA∗) (Argov et al., 2019; Lin and Little, 1988) and a plasmid ectopically expressing RecA under the regulation of the PTetR promoter (pPL2-recA). Transcription of SOS genes and φ10403S virion production were analyzed under MC treatment in lexA3 bacteria expressing or not expressing RecA compared with WT Lm. As expected, lexA3 bacteria exhibited low transcription of SOS genes (shown on uvrX and lexA itself) and produced less virions compared with WT Lm (∼ 80% less) (Figures 3C and 3D). However, when these bacteria ectopically expressed RecA, virion production was restored to nearly WT levels without further activating the SOS genes (Figures 3C and 3D). These results indicated that RecA is the SOS determinant that is responsible for the induction of φ10403S, acting upstream to MpaR. We next investigated whether ectopic expression of RecA can also rescue the inhibition of the phage and the SOS response caused by LMRG_02920. For this purpose, we conjugated WT bacteria with pPL2 plasmids expressing either recA, LMRG_02920, or both genes (under the regulation of the PTetR promoter, pPL2-recA, pPL2-2920, and pPL2-recA-2920) and monitored for virion production and SOS gene transcription under MC. Ectopic expression of RecA alleviated all the inhibitory effects of LMRG_02920, bringing phage induction (shown by plaque-forming units [PFUs]) and SOS gene transcription (shown on uvrX and lexA) to WT levels (Figures 3E and 3F). Of note, ectopic expression of RecA in WT bacteria (not expressing LMRG_02920) did not lead to higher virion production or SOS gene transcription, implying that the WT level of RecA protein is sufficient to trigger their full induction. These findings suggested that LMRG_02920 interferes with RecA activity, thereby affecting both the phage elements and the bacterial SOS response. Furthermore, the observation that RecA expression failed to restore the induction of the SOS genes in lexA3 bacteria, yet fully recovered their induction in bacteria expressing LMGR_02920 (Figures 3D and 3F), supported the premise that LMRG_02920 acts as a RecA inhibitor rather than as a LexA corepressor.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of LMRG_02920 inhibits the bacterial SOS response

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative SOS genes (recA, lexA, and uvrX/LMRG_02221) in WT Lm and Lm bacteria expressing LMRG_02920 (using pPL2-2920). Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative SOS genes (recA, lexA, and uvrX/LMRG_02221) in Δφ/Δmon and Δφ/Δmon bacteria expressing LMRG_02920 (using pPL2-2920). Indicated strains were grown in BHI with MC treatment at 30°C for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative SOS genes (lexA and uvrX/LMRG_02221) in WT Lm and lexA3 bacteria expressing or not expressing recA from pPL2 plasmid (pPL2-recA). Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(D) A plaque-forming assay of φ10403S virions produced by WT Lm and lexA3 bacteria expressing or not expressing recA from pPL2 plasmid (pPL2-recA). Virions obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment at 30°C) were tested on an indicator strain for plaque formation (numerated as PFUs). The data are presented as percentage of the levels measured for WT Lm. The experiment was performed three times and error bars represent the standard deviation of independent experiments.

(E) A plaque-forming assay of φ10403S virions produced by WT Lm and bacteria expressing recA and LMRG_02920 (alone or together) from the pPL2 plasmid. Virions obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment at 30°C) were tested on an indicator strain for plaque formation (numerated as PFUs). The experiment was performed three times, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(F) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative SOS genes (lexA and uvrX/LMRG_02221) in WT Lm and in bacteria expressing recA and LMRG_02920 (alone or together) from pPL2 plasmid. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment, at 30°C, for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ, relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(G) Virions obtained from lytic induction of WT Lm were used to infect Δφ/ΔcomK, Δφ/ΔcomK expressing LMRG_02920 (Δφ/ΔcomK + pPL2-2920), and Δφ/ΔcomK expressing the φ10403S main repressor (Δφ/ΔcomK + pPL2-1514) as a control. The number of virions produced upon infection is presented as PFU/mL. The experiment was performed three times, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of independent experiments.

To confirm that LMRG_02920 prevents virion production by inhibiting the SOS system rather than by interfering with the phage lytic pathway per se, we compared virion production upon φ10403S infection of Lm bacteria expressing versus not expressing LMRG_02920 using free phage particles, a process that does not require the SOS system. To avoid possible phage immunity or lysogenization, we infected a strain that was cured of the phage and lacked the comK gene (Δφ/ΔcomK). In this model, LMRG_02920 expression did not interfere with the phage lytic pathway, as a comparable number of virions were produced in bacteria expressing or not expressing LMRG_02920 (Figure 3G). In contrast, in a control experiment, no virions were detected upon infection of bacteria expressing the phage CI-like repressor (LMRG_01514) instead of LMRG_02920 (using pPL2-1514) (Figure 3G). These results supported the conclusion that LMRG_02920 is a phage protein that targets the bacterial SOS system.

The ANT/KilAC domain of LMRG_02920 is responsible for inhibition of the SOS response

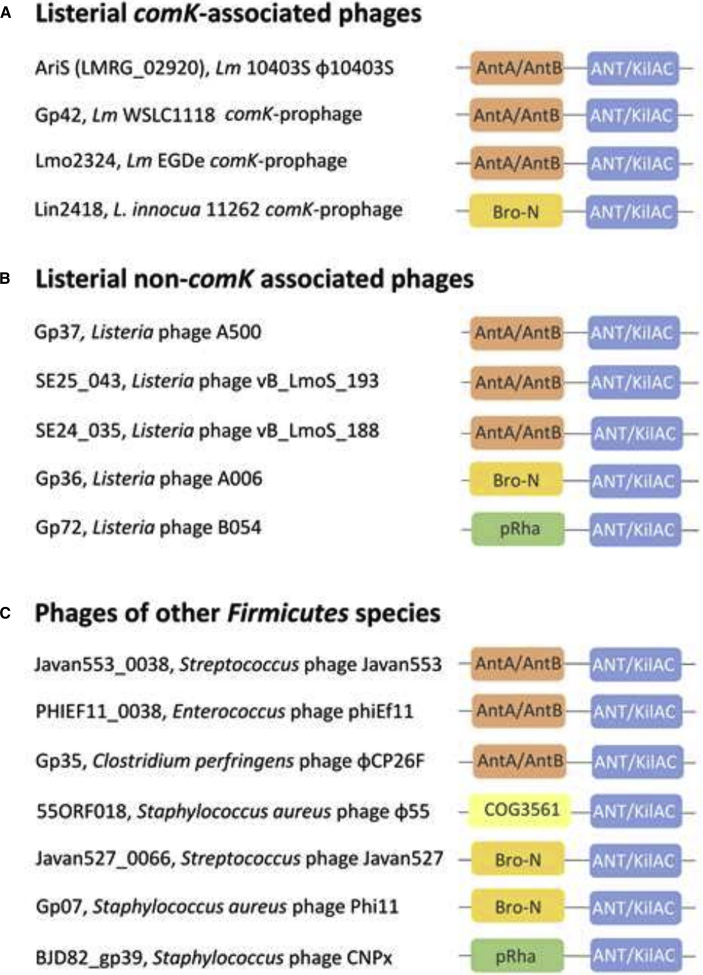

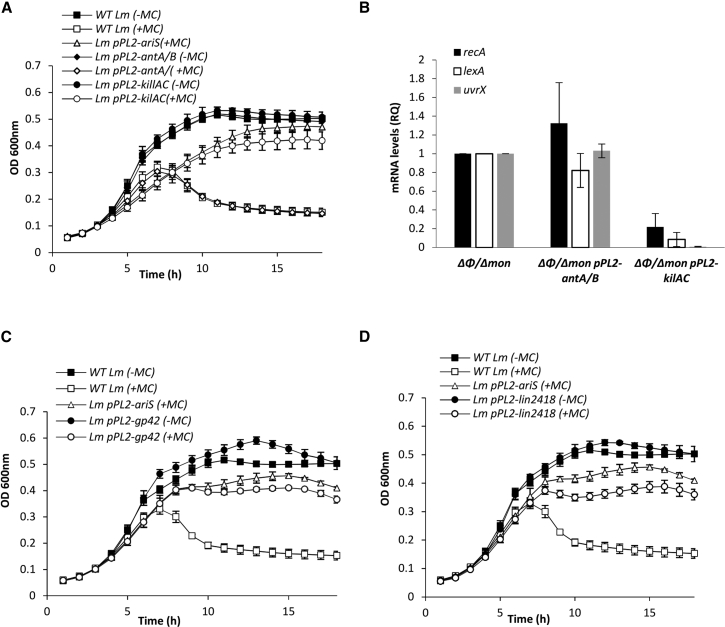

As mentioned, LMRG_02920 is annotated as a putative phage anti-repressor. It possesses two distinct structural domains (based on the Pfam database), one at the N terminus, belonging to the AntA/AntB family (Pfam database: pfam08346), and the other at the C terminus, belonging to the ANT/KilAC family (Pfam database: pfam03374) (Figure 4A). While both of these domains are associated with known phage anti-repressors (e.g., Ant1 and Ant2 of E. coli phages 1 and 7 [P1 and P7]) (Hansen, 1989; Iyer et al., 2002; Riedel et al., 1993), their exact function is still unclear. Since our data indicated a novel function for LMRG_02920, i.e., inhibition of the bacterial SOS response, hereafter it is referred to as AriS, for ant-regulator inhibitor of the SOS response. To determine whether AriS is conserved in other listerial comK prophages, we examined all the available complete Listeria genomes that contain a comK prophage (∼132 out of 356 complete Listeria genomes that were available) and found that all of them encode an AriS homolog that is located at a similar position in the early-lytic gene module (examples are shown in Figures 4A and S1). Interestingly, based on amino-acid-sequence similarity and gene location, we found AriS homologs also in other listerial prophages (i.e., non-comK associated) such as A500 (GenBank: NC_009810.1), A006 (GenBank: DQ003642.1), and B054 (GenBank: NC_009813.1) (examples are shown in Figure 4B), as well as in phages of other bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum, e.g., phage Javan553 of Streptococcus suis (GenBank: MK448804.1), phage φEf11 of Enterococcus faecalis (GenBank: NC_013696.1), phage φCP26F of Clostridium perfringens (GenBank: NC_019496.1), and phage φ11 of Staphylococcus aureus (GenBank: NC_004615.1) (Das and Biswas, 2019) (Figure 4C). Comparing these AriS-like proteins, we noticed that they all possessed a C-terminal ANT/KilAC domain, while their N-terminal domain varied between three different structural domains, AntA/AntB (Pfam database: pfam08346), Bro-N (SMART and COG databases: either smart01040 or COG3617), and pRha (Pfam and COG databases: either pfam09669 or COG3646), all of which are putative regulatory domains that associate with phage and viral regulators (Figures 4A–4C) (Iyer et al., 2002). Intrigued by this finding, we analyzed the distribution of these N-terminal domains in comK prophages and found that the AntA/AntB domain was the most prevalent, found in ∼87% of the AriS-like proteins, while Bro-N was found in ∼11% of the AriS-like proteins and pRha in only few prophages. To determine which of the two structural domains of AriS drives the SOS-inhibitory activity, we cloned each domain alone, i.e., the AntA/AntB domain (residues 1 to 144) and the ANT/KilAC domain (residues 144 to 259) in pPL2 plasmid, under the regulation of the PTetR promoter (pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC, respectively), and evaluated the ability of each domain to prevent bacterial lysis and to inhibit the SOS response under MC treatment. The results indicated that the ANT/KilAC domain is responsible for the inhibition of the SOS response, as its overexpression effectively prevented bacterial lysis and SOS gene transcription similarly to the AriS protein, whereas overexpression of the AntA/AntB domain failed to do so (Figures 5A and 5B). To examine whether this activity of ANT/KilAC is conserved in other AriS-like proteins, Gp42 of Lm strain WSLC1118 comK phage (sharing 77.48% sequence identity with AriS) (Loessner et al., 2000), comprising AntA/AntB and ANT/KilAC domains, and Lin2418 of L. innocua strain CLIP 11262 comK phage (sharing 30.45% sequence identity with AriS), comprising Bro-N and ANT/KilAC domains (Figures 4A and S1A–S1C), were cloned in the pPL2 plasmid (pPL2-gp42 and pPL2-lin2418, respectively) and expressed in Lm strain 10403S. As shown in Figures 5C and 5D, both proteins effectively prevented bacterial lysis under MC treatment, similar to AriS of φ10403S, therefore demonstrating that the ANT/KilAC SOS-inhibitory activity is conserved. These findings establish a new family of phage regulators that control the bacterial SOS response.

Figure 4.

Domain architecture in AriS homologous proteins of different phages

(A) Examples of AriS homologous proteins of different Listeria comK-associated prophages.

(B) Examples of AriS homologous proteins of Listeria non-comK-associated phages.

(C) Examples of AriS homologous proteins encoded by phages of other Firmicutes species. The N- and C-terminal domains shown here are not to scale.

Figure 5.

The ANT/KilAC domain is responsible for the SOS inhibitory activity of AriS

(A) Growth analysis of WT Lm and Lm bacteria overexpressing LMRG_02920 (Lm pPL2-ariS [the same plasmid as pPL2-2920]), the N-terminal AntA/B domain (Lm pPL2-antA/B), or the C-terminal ANT/KilAC domain (Lm pPL2-kilAC). Bacteria were grown in BHI medium in the presence of anhydrotetracycline (AT) to induce the PTetR promoter and in the presence (+) or absence (-) of MC at 30°C. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments and are sometimes hidden by the symbols.

(B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative SOS genes: recA, lexA, and uvrX (LMRG_02221) in Δφ/Δmon and Δφ/Δmon bacteria expressing each domain encoded by pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC plasmids. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(C) Growth analysis of WT Lm with or without overexpression of Gp42 of the comK-phage of Lm WSLC1118 (Lm pPL2-gp42) in the presence (+) or absence (-) of MC at 30°C. Overexpression of ariS (Lm pPL2-ariS) was used as a control. The experiment was performed three times, and the figure shows a representative result. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments and are sometimes hidden by the symbols.

(D) Growth analysis of WT Lm with or without overexpression of Lin2418 of the comK phage of Listeria innocua Clip 11262 (Lm pPL2-lin2418) in the presence (+) or absence (-) of MC at 30°C. Overexpression of ariS (Lm pPL2-ariS) was used as a control. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments and are sometimes hidden by the symbols.

The AriS N-terminal AntA/AntB domain regulates the phage and not the mon

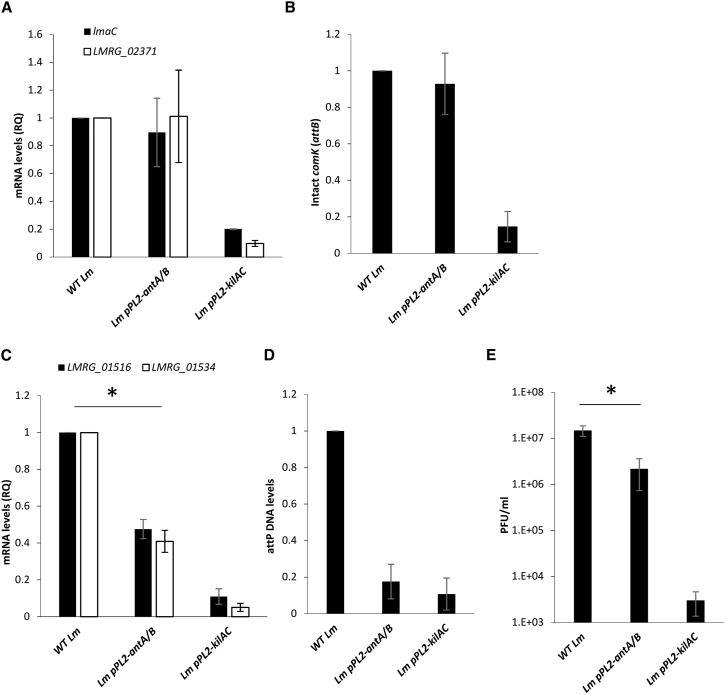

Since the bioinformatic analysis indicated that the N-terminal domain of AriS varies between prophages, we speculated that it holds a distinct activity that is specific to the encoding phage. To assess this hypothesis, we overexpressed the N-terminal AntA/AntB domain of AriS in WT bacteria (using pPL2-antA/B) and examined its impact on the transcription of phage and mon genes under MC treatment. We also examined its influence on phage excision, phage DNA replication, and virion production. Overexpression of AntA/AntB had no effect on the transcription of the mon genes (shown on two representative genes, lmaC and LMRG_02371) or on φ10403S excision (as shown by quantification of intact comK genes/attB sites), indicating that this domain does not affect the induction of the phage elements in contrast to the ANT/KilAC domain (Figures 6A and 6B). However, bacteria expressing this domain exhibited reduced transcription of the phage genes (∼50% less), as shown for the early gene LMRG_01516 and the late gene LMRG_01534 encoding a capsid protein (Figure 6C). In accordance, these bacteria demonstrated reduced phage DNA replication (∼80% less, shown by quantification of the phage DNA attP site) and ∼10-fold less virion production compared with WT bacteria (Figures 6D and 6E). These findings implied that the AntA/AntB domain acts specifically on the phage and not on the mon, regulating its lytic genes post induction.

Figure 6.

The N-terminal AntA/AntB domain regulates the phage genes and not the mon genes

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative mon genes, lmaC and LMRG_02371, in WT Lm and Lm bacteria expressing each domain separately via pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of φ10403S attB site (representing the intact comK gene) in WT Lm and in Lm bacteria expressing each domain separately via pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC. Indicated strains were grown in BHI with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. The data are presented as RQ relative to the levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of representative phage genes: the early gene LMRG_01516 and the late gene LMRG_01534 encoding a capsid in WT Lm, and Lm bacteria expressing each domain separately using pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(D) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of the φ10403S attP site in WT Lm and in Lm bacteria expressing each domain separately via pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC. Indicated strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 3 h. The data are presented as RQ relative to the levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(E) A plaque-forming assay of WT Lm and Lm bacteria expressing each domain separately via pPL2-antA/B and pPL2-kilAC. Virions obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment) were tested on an indicator strain for plaque formation (numerated as PFUs). The experiment was performed three times, and the error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments. Asterisks represent p values (p < 0.05).

To examine the impact of each domain on the phage and the mon element, mutants deleted of each one of AriS domains were generated (ΔantA/B and ΔkilAC). The mutants were tested for virion and monocin production and SOS gene transcription under MC treatment compared with ΔariS and WT Lm. As shown in Figure 7, ΔantA/B and ΔkilAC behaved similarly to ΔariS, producing fewer virions and a WT level of monocins (Figures 7A and 7B). Moreover, the mutants exhibited a WT level of SOS gene transcription, indicating that AriS or the ANT/KilAC domain fail to inhibit the SOS response under these conditions (shown on uvrX; Figure 7C). Nevertheless, these data demonstrated that under these conditions, the native level of AriS promotes the lytic pathway of the phage. Taken together, these findings characterized AriS as a dual-function phage regulator that holds the capacity to regulate both phage and bacterial genes, which likely evolved to fine tune the response of the phage in the course of the lytic pathway, aligning it with the other phage elements that inhabit the genome.

Figure 7.

AriS affects only the phage and not the mon under MC treatment

(A) A plaque-forming assay of φ10403S. Virions were obtained from MC-treated cultures (6 h after the addition of MC) of WT Lm, ΔariS, and bacteria deleted of each AriS domain separately: ΔantA/B and ΔkilAC. Virions were used to infect an indicator strain and are numerated as PFUs. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(B) A monocin killing assay performed with monocins obtained from MC-treated bacterial cultures (6 h after MC treatment) of WT Lm, ΔariS, ΔantA/B, and ΔkilAC. A diluted overnight culture of the indicator Lm strain ScottA was supplemented with serial dilutions of filtered supernatants containing monocins and was grown at 30°C. OD600 was measured after 10 h. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

(C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of uvrX in WT Lm and indicated mutants. The strains were grown in BHI medium with MC treatment at 30°C for 45 min. mRNA levels are presented as RQ relative to their levels in WT bacteria. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Coordination between cohabiting phage elements in polylysogenic strains is a prerequisite not only for the survival of the phage elements but also for the survival of the bacteria, as it minimizes the bacterial lysis events and maximizes the chance that the elements will produce virions/particles before the host cells lyse. Such coordination requires both bacteria-phage and phage-phage cross-regulatory interactions that collectively align the response of the phage elements with that of the host. In this study, we uncovered yet another example of a cross-regulatory interaction between Lm strain 10403S and its resident phage elements and identified a phage protein that controls the bacterial SOS response, hence holding the capacity to regulate all the phage elements that inhabit the genome. Previous studies from our group indicated that the two phage elements of Lm strain 10403S are evolutionarily interlinked. They are both induced by the same anti-repressor (MpaR) and simultaneously trigger bacterial lysis, hence concomitantly releasing virions and monocins to the environment (Argov et al., 2019). While these findings demonstrated that the lytic cycles of the two phage elements are well coordinated (from start to finish), they raised the hypothesis that the elements further “communicate” via auxiliary cross-regulatory interactions that support their coexistence. With this in mind, we set out to search for phage factors that affect the lytic pathway of the two elements, which led to the discovery of AriS, a conserved phage protein that regulates both phage and bacterial genes.

AriS was identified based on its ability to inhibit the induction of the two phage elements under MC treatment when overexpressed. It was further found to inhibit the bacterial SOS response, independently of the phage elements, indicating that it functions upstream of MpaR, by inhibiting one of the key regulators of the SOS system (e.g., RecA or LexA). Examining the role of RecA and LexA in the induction of the phage elements, we found that RecA, and not LexA, is directly involved in their induction. Further experiments suggested that AriS inhibits RecA (directly or indirectly) thereby preventing induction of the phage elements and the SOS response. In these experiments, ectopic expression of RecA rescued the induction of the phage in lexA3 bacteria without triggering the SOS response, yet it rescued both the phage induction and the SOS response in bacteria expressing AriS. These findings, together with the observation that RecA is not limited in bacteria not expressing AriS (i.e., in WT bacteria), supported the premise that AriS most likely inhibits RecA rather than acting as a LexA corepressor. Interestingly, this SOS inhibitory activity of AriS was associated with its C-terminal ANT-KilAC domain, a domain that was found to be conserved in many AriS-like proteins of listerial and non-listerial prophages. Examining the AriS-like proteins of Lm strain WSLC1118 and L. innocua CLIP 11262 comK phages, we demonstrated that both the ANT-KilAC domain and its SOS inhibitory activity are conserved, indicating that inhibition of the SOS response is a common strategy of temperate phages. Moreover, we found the AriS-like proteins to possess a distinct structural domain at their N terminus, which alternates between a set of three phage-related structural domains, AntA/AntB, Bro-N, and pRha. Investigating the N-terminal AntA/AntB domain of AriS, we found that it holds a distinct activity that specifically regulates the phage and not the mon element. Interestingly, all of these structural domains were suggested to be DNA-binding domains like those that are commonly found in multidomain proteins of large DNA viruses (Iyer et al., 2001, 2002). Comparative studies suggested that these phage-related domains originated from eukaryotic DNA viruses, which carry transcription regulators with a similar domain architecture (Iyer et al., 2002). The phenomenon of combinatorial domain shuffling was also observed in these studies, demonstrating limited sets of domains that combine in regulatory proteins of bacterial and eukaryotic viruses, increasing their diversity and repertoire of activities (Iyer et al., 2002). In line with these reports, our discovery that the alterable N-terminal domain of AriS is the one that specifically regulates the phage (and not the mon or the SOS response) supports the hypothesis that its modularity evolved to fit the encoding phage and not the host, providing a molecular insight into the evolution of the AriS-like proteins. Taken together, the characterization of the two activities of AriS and their corresponding structural domains uncovered yet another mechanism by which prophages can directly and indirectly modulate their lytic response, taking into account the other phage elements that inhabit the genome. In this regard, we hypothesize that AriS did not evolve to completely block the host SOS response under conditions of DNA damage, as it wouldn’t benefit the bacteria or the phage, but rather it evolved to manipulate it post induction, providing the phage with other means to control its lytic pathway. This may explain why the SOS inhibitory activity of AriS was observed only when overexpressed, as the native level of AriS does not have the capacity to prevent the robust induction of the SOS response.

As mentioned, a mutant deleted of the ariS gene was previously generated by our group and investigated for its behavior under SOS conditions (Pasechnek et al., 2020). This mutant exhibited impaired virion production and differential phage gene transcription, demonstrating high transcription of early genes and low transcription of late genes compared with WT bacteria. Interestingly, this differential transcriptional response was detected late into the lytic pathway (i.e., 4–5 h post induction), suggesting that AriS acts as a temporal regulator that fine tunes the phage lytic response (i.e., downregulating the early genes and upregulating the late genes) (Pasechnek et al., 2020). While the mechanism by which AriS executes this activity is still unclear, the results presented here support this hypothesis, as they demonstrate that AriS holds both direct and indirect means of regulating the phage transcriptional response. For example, downregulation of the early genes can be mediated by the ANT/KilAC domain, which attenuates RecA. Unfortunately, we could not differentiate between the two activities of AriS using deletion mutants of each domain as they exhibited phenotypes that were similar to ΔariS. It remains to be determined when and where AriS executes each one of its activities and how they are regulated in the course of the lytic pathway. In this regard, the regulation of the two activities may be even more complex. A previous study identified a tyrosine residue (Tyr98) that was phosphorylated in the AriS-like protein of Lm strain EGD-e comK phage (sharing 83.40% amino-acid-sequence identity with AriS; Figure S1D) (Misra et al., 2011). In an attempt to examine if this phosphorylation affects AriS activities, we substituted the corresponding tyrosine in the AriS of φ10403S with alanine (AriS-Y99A). Yet, this substitution yielded a non-functional protein that failed to inhibit the SOS response, reminiscent of ΔariS (Figure S2). While this result made it difficult to decipher the effect of this tyrosine on AriS activities, it is still possible that AriS is regulated by protein phosphorylation, a hypothesis that requires further investigation.

Several reports demonstrated phage-mediated manipulation of the SOS system. For example, in Salmonella enterica, it was shown that infection with lytic mutants of P22 and SE1 phages results in the activation of the SOS response, which, in turn, triggers the induction of resident prophages (Campoy et al., 2006). This phenotype was linked to the kil gene, which is carried by both phages. Overexpression of this gene was shown to inhibit bacterial cell division. However, since finding that it activates the SOS response, this phenotype was suggested to relate to the expression of SulA, a known SOS-regulated cell-division inhibitor (Schoemaker et al., 1984). While the biological benefit of SOS induction upon phage infection remains unclear, it was proposed to serve as a fail-proof mechanism to prevent the loss of prophages in the evolutionary arms race with lytic phages (Campoy et al., 2006). Another example of a viral protein that interacts with the SOS system is gp7 of Bacillus thuringiensis temperate phage GIL01. Protein gp7 was shown to directly interact with LexA and act as its corepressor, hence preventing induction of the SOS genes. Notably, in this case, it was shown that GIL01 is missing a CI-like repressor and that it uses the bacterial LexA as its main repressor, albeit only in the presence of gp7. Further, it was demonstrated that gp7 forms a stable complex with LexA, enhancing its binding to the phage operator sites in a way that interferes with its autocleavage by RecA (Caveney et al., 2019; Fornelos et al., 2015). Such a mechanism appears to also exist in other phages, e.g., in CTXφ of Vibrio cholerae, where its XRE-family repressor RstR similarly interacts with LexA (Quinones et al., 2005). As described, our data favor the possibility that AriS inhibits the activity of RecA rather than acting as a LexA corepressor. Although, RecA plays a critical role in the induction of prophages, rendering it a perfect target for phage manipulation, we did not find in the literature examples of phage proteins that interfere with RecA activity. Notwithstanding, we found one report on a protein encoded by a conjugative plasmid (PsiB) that inhibits RecA activity, hence enabling recipient cells to accept ssDNA by conjugation without triggering the SOS response, which can be deleterious (Petrova et al., 2009). In light of this example, we surmise that temperate phages also acquired mechanisms to manipulate RecA for their own benefit. The examples presented here suggest that regulation of the SOS system by temperate phages and other mobile genetic elements is a common strategy driving their interaction with the host. In this respect, AriS represents yet another player in the intricate interaction between bacteria and temperate phages.

Limitations of the study

In Figure 2B, we observed an accumulation of the mon CI-like repressor in bacteria overexpressing AriS. It appears that AriS stabilizes the mon repressor, and this can be done directly or indirectly. It is possible that there is another interaction between AriS and the mon CI-repressor. It is important to note that the system used in this experiment is, in a way, artificial, as MpaR, AriS, and the mon CI-like repressor are overexpressed in a strain that is deleted of the two phage elements. The purpose of using this system was to examine whether AriS has any effect on the cleavage of the mon CI-repressor, and after calculating the cleaved fraction of the CI-like repressor, the answer was yes. In addition, in this study, we do not provide the precise mechanism by which AriS inhibits RecA and the SOS response. Several attempts to find the direct interactor(s) of AriS using various pull-down techniques have failed. Moreover, the main observations in this study are based on overexpression of AriS and its related domains.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-6His tag antibody | Abcam | ab9108; RRID:AB_307016 |

| Anti-GFP antibody | BioLegend | 902601 (MMS-118P); RRID:AB_2565021 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Lm 10403S | Prof. Daniel Portnoy (University of California, Berkley) | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| mitomycin C | Sigma | M4287 |

| Brain Heart Infusion Broth | Sigma | 53286-500G |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| qScript cDNA Synthesis Kit | Quantabio | 95047-025 |

| PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix ROX | Quantabio | 95073-012 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Source file including raw experimental data | This study | Mendeley Data, V1, https://doi.org/10.17632/63pm8ctx22.1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| StepOne V2.1 | Applied Biosystems | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Synergy HT | BioTek | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Anat Herskovits (anathe@tauex.tau.ac.il).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents. The plasmids and strains used in this study will be made available on request, but we may require a payment and/or a completed Materials Transfer Agreement if there is potential for commercial application.

Experimental model and subject details

Bacterial strains

Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) strain 10403S was obtained from Prof. Daniel Portnoy (University of California, Berkley) and used as the WT strain. Lm 10403S strain cured of φ10403S phage (DPL-4056) was generated by Prof. Richard Calendar (University of California, Berkley) by biological curing. E. coli XL-1 Blue (Stratagene) was utilized for vector propagation. E. coli SM-10 was utilized for conjugative plasmid delivery to Lm bacteria. Lm strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) (Merck) medium at 37°C or 30°C as specified, and E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (Acumedia) medium at 37°C.

Method details

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

L. monocytogenes strain 10403S was used as a WT strain and as a parental strain for the generation of all mutants in this study, unless otherwise indicated. E. coli XL-1 Blue (Stratagene, Agilent) was utilized for vector propagation. E. coli SM-10 was utilized for conjugative plasmid delivery to L. monocytogenes bacteria. Listeria strains were grown in BHI (Merck) medium, at 37°C or 30°C, and E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) (Acumedia) medium at 37°C. Phusion DNA polymerase was used for all cloning purposes and Taq polymerase for verification of the different plasmids and strains by PCR. Antibiotics were used as follows: chloramphenicol (Cm), 10 μg/mL; streptomycin (Strep), 100 μg/mL; kanamycin (Km), 30 μg/mL; and mitomycin C (MC) (Sigma), 1.5 μg/mL. All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs. Strain, plasmids and primers used in this study are described in Table S1.

Bacterial lysis under MC treatment

Bacteria were grown overnight (O.N.) at 37°C, with agitation, in BHI broth, and then diluted to an OD at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.15 and pipetted in triplicates into a 96-well plate with or without MC (1.5 μg/mL). The plates were incubated at 30°C, in a Synergy HT BioTek plate reader, and the OD600 was measured every 15 min after 2 min of shaking. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Plaque-forming assay

Bacteria were grown O.N. at 37°C, with agitation, in BHI broth, then diluted by a factor of 10 in fresh BHI broth, incubated without agitation at 30°C, to reach an OD600 of 0.4, then diluted to an OD600 of 0.15, and the lytic cycle was induced by the addition of MC (1.5 μg/mL) and incubation at 30°C for 6 h, without agitation. Bacterial cultures were passed through 0.22 μm filters that do not allow the passage of bacteria. Dilutions of the filtered supernatants (100 μL) were added to 3 mL melted LB-0.7% agar medium at 56°C, supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2, and 300 μL of an O.N. culture of L. monocytogenes Mack861 or Δφ/ΔcomK (used as indicator strains), and quickly overlaid on BHI-agar plates. Plates were incubated for 3–4 days at room temperature to allow plaques to form.

Monocin killing assay

10403S Lm bacteria were grown O.N. at 37°C, with agitation, in BHI broth, then diluted 1:10 in BHI broth, incubated without agitation at 30°C to reach an OD600 of 0.4, and diluted again to an OD600 of 0.15. Thereafter, the lytic cycle was induced by the addition of MC (1.5 μg/mL) and bacteria were incubated for 6 h. Bacterial cultures were then passed through 0.22 μm filters. An O.N. culture of Lm strain ScottA was inoculated 1:100 in BHI medium supplemented with indicated dilutions of the monocins filtrate obtained after lytic induction of Lm strain 10403S. Technical duplicates were pipetted into 96-well plates and were incubated at 30°C in a Synergy HT BioTek plate reader. OD600 was measured every 15 min after 2 min of shaking. The OD of the cultures after 10 h of incubation was plotted against the monocin concentration. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Generation of gene deletion mutants, complementation and overexpression strains

To prepare gene deletion mutants, upstream and downstream regions of the target gene were amplified using Phusion DNA polymerase, and cloned into the pBHE vector (pKSV-oriT). Cloned plasmids were verified by PCR and their PCR-amplified inserts were sequenced. The plasmids were then conjugated to L. monocytogenes using the E. coli SM-10 strain. Transconjugants were selected on BHI agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol and streptomycin and transferred to BHI supplemented with chloramphenicol, for 2 days, at 41°C, to allow plasmid integration into the bacterial chromosome by homologous recombination. The bacteria were passed several times in fresh BHI medium without chloramphenicol, at 30°C, to promote plasmid curing and the generation of an in-frame gene deletion. The bacteria were plated on BHI plates and on BHI plates supplemented with chloramphenicol. The sensitive colonies were validated for gene deletion by PCR. For overexpression strains, the gene was cloned into the pPL2 integrative vector under regulation of the PTetR promoter (Pasechnek et al., 2020). Of note, once pPL2 is integrated in the bacterial chromosome, no antibiotic selection is used. The PCR-amplified insert was sequenced, and the plasmid was conjugated to L. monocytogenes using the E. coli SM-10 strain. Overexpression was performed without further induction with anhydro-tetracycline (AT), unless otherwise indicated (in this case AT was added at a concentration of 100 ng/mL). Details about the cloning of plasmids and strains that were generated for this study are described in Supplementary File 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Bacteria were grown at 37°C O.N., with agitation, in BHI broth, then diluted 1:10 in BHI broth, incubated, without agitation, at 30°C to reach an OD600 of 0.4, and then diluted to an OD600 of 0.15. Thereafter, a lytic cycle was induced by addition of MC (1.5 μg/mL). Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at indicated time points and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total nucleic acids were isolated using standard phenol-chloroform extraction methods. For analysis of attB levels by RT-qPCR, 0.04 ng total nucleic acids were used, while the Lm 16S rRNA gene was used as a reference for sample normalization. For gene expression analysis, the samples were treated with DnaseI, and 1 μg RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a qScript (Quanta) kit. RT-qPCR was performed on 10 ng cDNA. The relative expression of bacterial genes was determined by comparing their transcript levels with those of the Lm 16S rRNA or rpoD gene, which served as a reference. All RT-qPCR analyses were performed using the PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix (Quanta) on the StepOnePlus RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems), as per the standard ΔΔCt method. Statistical analysis was performed using StepOne V2.1 software. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Analyzing mon CI-like repressor cleavage by western blot

The mon-CI-like repressor was tagged by translational fusion of GFP to the C-terminus of the protein under the regulation of a constitutive promoter (Argov et al., 2019). The tagged CI-like repressor was cloned on the integrative pPL2 plasmid harboring the MpaR protease, under the regulation of the inducible PTetR promoter. The resulting plasmid (pPL2-mon-cI-gfp-mpaR) was delivered by conjugation into Δφ/Δmon L. monocytogenes bacteria. For co-expression of LMRG_02920, the gene under the regulation of the inducible PTetR promoter was cloned on the integrative pPL1 plasmid harboring a kanamycin-resistance gene for selection, and the resulting plasmid (pPL1-LMRG_02,920) was delivered by conjugation into Δφ/Δmon Lm + pPL2-mon-cI-gfp-mpaR. Bacteria were grown at 30°C, in 100 mL BHI broth, to OD600 of 0.3. The cultures were then supplemented with MC (1.5 μg/mL) and anhydrotetracycline (AT) (100 ng/mL), and grown for an additional 2.5 h, harvested, washed with Buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl pH = 8, 0.5 M NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA), resuspended in 1 mL Buffer A supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, and lysed by ultra-sonication. Total protein content was quantified using a modified Lowry assay, and samples with equal amounts of total proteins were separated on 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and then trans-blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Proteins were probed with rabbit anti-GFP antibodies (BioLegend 902601) at a 1:5000 dilution, for the detection of mon-CI-GFP, followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) at a 1:20,000 dilution. Western blots were developed using homemade enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents. Images were obtained using an Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Genome analysis of Listeria comK-associated prophages

A number of complete Listeria genus and individual Listeria species genomes were retrieved from the NCBI Genomes database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome accessed on November 1, 2021). Particularly, the website Genome Assembly and Annotation report (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/browse/#!/prokaryotes/159/accessed on November 1, 2021) provides a list of both complete genomes and incomplete genome assemblies of Listeria monocytogenes strains. The above-mentioned website also provides a filter option by which, one can analyze exclusively complete genomes of L. monocytogenes (for that "Chromosome" and "Complete" should be selected); this approach revealed a number of complete genomes of other Listeria species (e.g. L. innocua, L. seeligeri, L. ivanovii). To determine the number of complete Listeria genomes that carry intact comK-associated prophages, we developed an approach that is based on a comK-phage-specific query (the integrase gene sequence of the Listeria phage A118) and the customized Nucleotide BLAST machine setup at the NCBI (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi accessed on November 1, 2021), using the following filters: i) Nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database (consists of GenBank + EMBL + DDBJ sequences, excluding WGS data); ii) Max target sequences (500); iii) Expect threshold (either 10 or 100). The result of this search yielded a list of complete genomes of Listeria species as well as the two known Listeria phages, A118 and PSU-VKH-LP019, that possess an entire sequence of the integrase gene. A similar approach was used to verify a number of complete Listeria genomes using the nucleotide sequence of either dnaA or dnaN gene of the reference L. monocytogenes strain 10403S. As for May 2021, 356 complete Listeria genomes were identified, of which 132 were found to contain a prophage in the comK gene. Having these genomes the sequences of the comK-associated prophages were extracted and further analyzed.

Bioinformatic analysis of AriS homologs

The different functional domains of AriS and its homologues were identified using the Pfam 34.0 protein family database (http://pfam.xfam.org/accessed on November 1, 2021), the integrated resource of Protein Domains (InterPro) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/accessed on November 1, 2021), the database of protein families and domains PROSITE (https://prosite.expasy.org/accessed on November 1, 2021), and the SMART database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/accessed on November 1, 2021). BLAST analyses of protein amino acid sequences were performed using the NCBI server (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi accessed on November 1, 2021) (Altschul et al., 1990). BlastP search for AriS homologues distinguished in their N-terminal sequences was conducted by using the following Reference Sequences as queries: WP_014601097.1 (AntA/AntB/pfam08346 and KilAC/pfam03374), WP_031644323.1 (Bro-N/COG3617 and KilAC/COG3645), WP_010991177.1 (COG3617 and KilAC/COG3645), WP_050018552.1 (COG3561 and KilAC/pfam03374), and WP_003731503.1 (Phage_pRha/pfam09669 and KilAC/COG3645).

Quantification and statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean of three biological repeats (n = 3) ± 1 standard deviation, unless indicated otherwise. Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t test. For western blotting analysis a representative experiment is shown, and additional biological repeats can be found in the provided raw data file. Details of statistical analysis can be found in the Figure Legends.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) starting and consolidator grants (Patho-Phage-Host 335400 and Co-Patho-Phage 817842) and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF 1381/18) to A.A.H.

Author contributions

G.A. and A.A.H. designed the study. G.A., A.P., O.S., S.R.-S., A.M.F., and N.S. performed the experiments. N.S. validated the results. I.B. performed bioinformatic analysis, and A.A.H. wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and diversity

We worked to ensure diversity in experimental samples through the selection of the genomic datasets. One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. While citing references scientifically relevant for this work, we also actively worked to promote gender balance in our reference list.

Published: April 19, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110723.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

The accession number for the underlying data (source file) of this paper is Mendeley Data doi: https://doi.org/10.17632/63pm8ctx22.1.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argov T., Azulay G., Pasechnek A., Stadnyuk O., Ran-Sapir S., Borovok I., Sigal N., Herskovits A.A. Temperate bacteriophages as regulators of host behavior. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017;38:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argov T., Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Herskovits A.A. An effective counterselection system for Listeria monocytogenes and its use to characterize the monocin genomic region of strain 10403S. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;83:e02927–e03016. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02927-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argov T., Sapir S.R., Pasechnek A., Azulay G., Stadnyuk O., Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Borovok I., Herskovits A.A. Coordination of cohabiting phage elements supports bacteria-phage cooperation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:5288. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13296-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns N., James C.E., Harrison E. Polylysogeny magnifies competitiveness of a bacterial pathogen in vivo. Evol. Appl. 2015;8:346–351. doi: 10.1111/eva.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy S., Hervas A., Busquets N., Erill I., Teixido L., Barbe J. Induction of the SOS response by bacteriophage lytic development in Salmonella enterica. Virology. 2006;351:360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S. Prophages and bacterial genomics: what have we learned so far? Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:277–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S.R., Hendrix R.W. Bacteriophage lambda: early pioneer and still relevant. Virology. 2015;479-480:310–330. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caveney N.A., Pavlin A., Caballero G., Bahun M., Hodnik V., de Castro L., Fornelos N., Butala M., Strynadka N.C.J. Structural insights into bacteriophage GIL01 gp7 inhibition of host LexA repressor. Structure. 2019;27:1094–1102.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart P. Illuminating the landscape of host-pathogen interactions with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:19484–19491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112371108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A., Biswas M. Cloning, overexpression and purification of a novel two-domain protein of Staphylococcus aureus phage Phi11. Protein Expr. Purif. 2019;154:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E.V., Winstanley C., Fothergill J.L., James C.E. The role of temperate bacteriophages in bacterial infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016;363:fnw015. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnw015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau D. DNA uptake in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1999;53:217–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiner R., Argov T., Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Borovok I., Herskovits A.A. A new perspective on lysogeny: prophages as active regulatory switches of bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:641–650. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornelos N., Butala M., Hodnik V., Anderluh G., Bamford J.K., Salas M. Bacteriophage GIL01 gp7 interacts with host LexA repressor to enhance DNA binding and inhibit RecA-mediated auto-cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:7315–7329. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag N.E., Port G.C., Miner M.D. Listeria monocytogenes - from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E.B. Structure and regulation of the lytic replicon of phage P1. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;207:135–149. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90445-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L.M., Aravind L., Koonin E.V. Common origin of four diverse families of large eukaryotic DNA viruses. J. Virol. 2001;75:11720–11734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11720-11734.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L.M., Koonin E.V., Aravind L. Extensive domain shuffling in transcription regulators of DNA viruses and implications for the origin of fungal APSES transcription factors. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-3-research0012. RESEARCH0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Kim H.J., Son S.H., Yoon H.J., Lim Y., Lee J.W., Seok Y.J., Jin K.S., Yu Y.G., Kim S.K., et al. Noncanonical DNA-binding mode of repressor and its disassembly by antirepressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E2480–E2488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602618113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer K.N. DNA damage responses in prokaryotes: regulating gene expression, modulating growth patterns, and manipulating replication forks. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a012674. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Chakraborty U., Gebhart D., Govoni G.R., Zhou Z.H., Scholl D. F-type bacteriocins of Listeria monocytogenes: a new class of phage tail-like structures reveals broad parallel coevolution between tailed bacteriophages and high-molecular-weight bacteriocins. J. Bacteriol. 2016;198:2784–2793. doi: 10.1128/JB.00489-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos Rocha L.F., Blokesch M. A vibriophage takes antirepression to the next level. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:493–495. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.L., Little J.W. Isolation and characterization of noncleavable (ind-) mutants of the lexa repressor of escherichia-coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1988;170:2163–2173. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2163-2173.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J.W. Mechanism of specific LexA cleavage: autodigestion and the role of RecA coprotease. Biochimie. 1991;73:411–421. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90108-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loessner M.J., Inman R.B., Lauer P., Calendar R. Complete nucleotide sequence, molecular analysis and genome structure of bacteriophage A118 of Listeria monocytogenes: implications for phage evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:324–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardanov A.V., Ravin N.V. The antirepressor needed for induction of linear plasmid-prophage N15 belongs to the SOS regulon. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:6333–6338. doi: 10.1128/JB.00599-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra S.K., Milohanic E., Ake F., Mijakovic I., Deutscher J., Monnet V., Henry C. Analysis of the serine/threonine/tyrosine phosphoproteome of the pathogenic bacterium Listeria monocytogenes reveals phosphorylated proteins related to virulence. Proteomics. 2011;11:4155–4165. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim A.B., Kobiler O., Stavans J., Court D.L., Adhya S. Switches in bacteriophage lambda development. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2005;39:409–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.113656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasechnek A., Rabinovich L., Stadnyuk O., Azulay G., Mioduser J., Argov T., Borovok I., Sigal N., Herskovits A.A. Active lysogeny in Listeria monocytogenes is a bacteria-phage adaptive response in the mammalian environment. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107956. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova V., Chitteni-Pattu S., Drees J.C., Inman R.B., Cox M.M. An SOS inhibitor that binds to free RecA protein: the PsiB protein. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy D.A., Auerbuch V., Glomski I.J. The cell biology of Listeria monocytogenes infection: the intersection of bacterial pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunity. J. Cell Biol. 2002;158:409–414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004. A Genetic Switch–Phage Lambda Revisited. [Google Scholar]

- Quinones M., Kimsey H.H., Waldor M.K. LexA cleavage is required for CTX prophage induction. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich L., Sigal N., Borovok I., Nir-Paz R., Herskovits A.A. Prophage excision activates Listeria competence genes that promote phagosomal escape and virulence. Cell. 2012;150:792–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel H.D., Heinrich J., Heisig A., Choli T., Schuster H. The antirepressor of phage P1. Isolation and interaction with the C1 repressor of P1 and P7. FEBS Lett. 1993;334:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker J.M., Gayda R.C., Markovitz A. Regulation of cell division in Escherichia coli: SOS induction and cellular location of the sulA protein, a key to lon-associated filamentation and death. J. Bacteriol. 1984;158:551–561. doi: 10.1128/JB.158.2.551-561.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silpe J.E., Bridges A.A., Huang X., Coronado D.R., Duddy O.P., Bassler B.L. Separating functions of the phage-encoded quorum-sensing-activated antirepressor qtip. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:629–641.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M.D., Smith B.T., Godoy V.G., Walker G.C. The SOS response: recent insights into umuDC-dependent mutagenesis and DNA damage tolerance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000;34:479–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink R., Loessner M.J., Scherer S. Characterization of cryptic prophages (monocins) in Listeria and sequence analysis of a holin/endolysin gene. Microbiology. 1995;141:2577–2584. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

The accession number for the underlying data (source file) of this paper is Mendeley Data doi: https://doi.org/10.17632/63pm8ctx22.1.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.