Key Points

Question

What are the risks of comorbidities in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris or pompholyx?

Findings

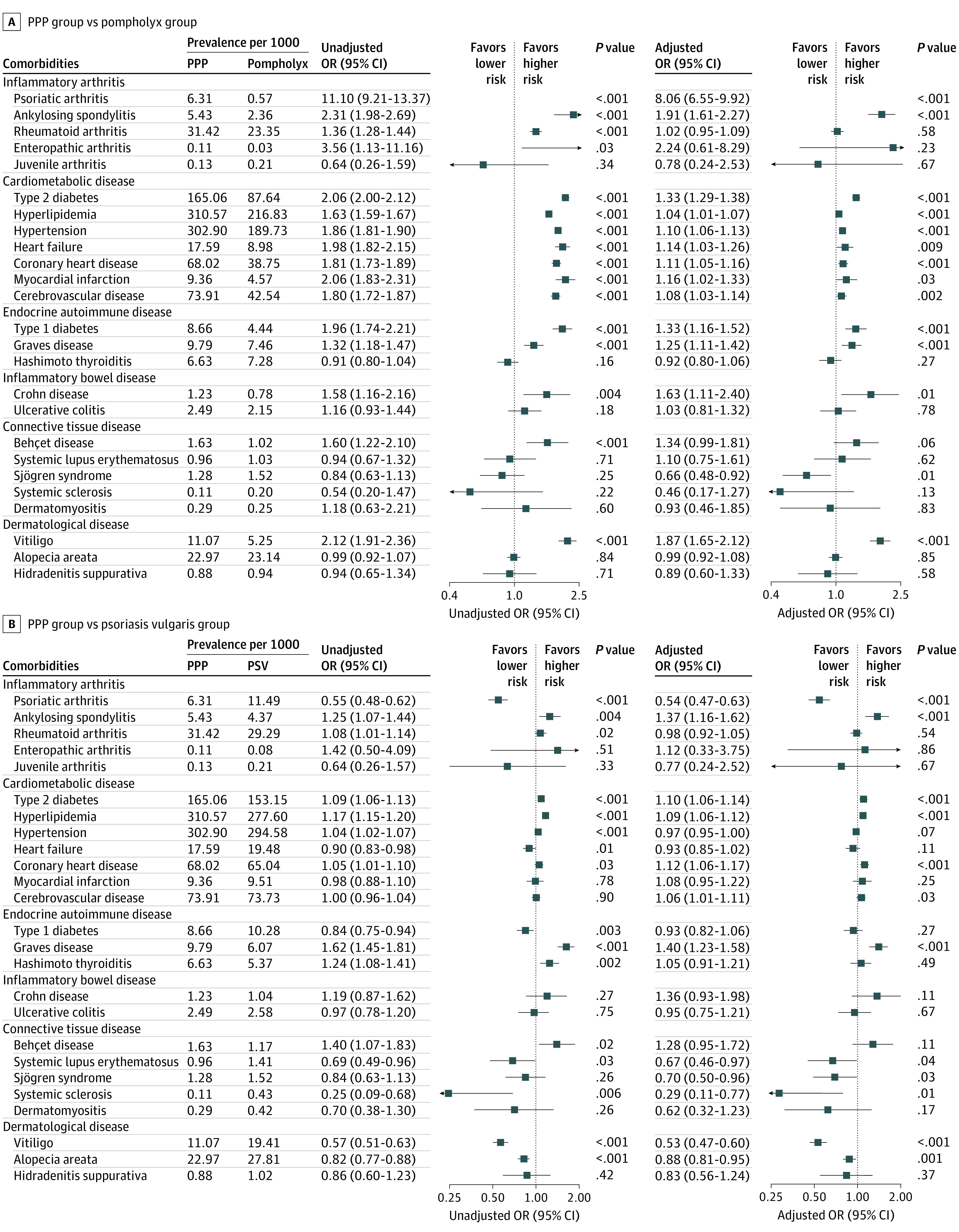

In this cross-sectional study of 37 399 patients with PPP, 332 279 patients with psoriasis vulgaris, and 365 415 patients with pompholyx in Korea, a diagnosis of PPP was associated with inflammatory arthritis, cardiometabolic diseases, autoimmune diseases, and vitiligo compared with the presence of pompholyx. Among patients with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris, the risks of ankylosing spondylitis and Graves disease were higher, whereas the risks of psoriatic arthritis and vitiligo were lower.

Meaning

These results suggest that patients with PPP have an overlapping comorbidity profile with patients with psoriasis vulgaris but not with patients with pompholyx; however, the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP may be significantly different from those in patients with psoriasis vulgaris.

Abstract

Importance

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) has been reported to be accompanied by systemic conditions. However, the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP have rarely been evaluated.

Objective

To assess the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris or pompholyx.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This nationwide population-based cross-sectional study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance database and the National Health Screening Program collected from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019. Data were analyzed from July 1, 2020, to October 31, 2021. Korean patients diagnosed with PPP, psoriasis vulgaris, or pompholyx who visited a dermatologist between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019, were enrolled.

Exposures

Presence of PPP.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The risks of comorbidities among patients with PPP vs patients with psoriasis vulgaris or pompholyx were evaluated using a multivariable logistic regression model.

Results

A total of 37 399 patients with PPP (mean [SD] age, 48.98 [17.20] years; 51.7% female), 332 279 patients with psoriasis vulgaris (mean [SD] age, 47.29 [18.34] years; 58.7% male), and 365 415 patients with pompholyx (mean [SD] age, 40.92 [17.63] years; 57.4% female) were included in the analyses. Compared with patients with pompholyx, those with PPP had significantly higher risks of developing psoriasis vulgaris (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 72.96; 95% CI, 68.19-78.05; P < .001), psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 8.06; 95% CI, 6.55-9.92; P < .001), ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.61-2.27; P < .001), type 1 diabetes (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.16-1.52; P < .001), type 2 diabetes (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.29-1.38; P < .001), Graves disease (aOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11-1.42; P < .001), Crohn disease (aOR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.11-2.40; P = .01), and vitiligo (aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.65-2.12; P < .001) after adjusting for demographic covariates. The risks of ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.62; P < .001) and Graves disease (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58; P < .001) were significantly higher among patients with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris. However, the risks of psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.47-0.63; P < .001), systemic lupus erythematosus (aOR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97; P = .04), Sjögren syndrome (aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50-0.96; P = .03), systemic sclerosis (aOR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11-0.77; P = .01), vitiligo (aOR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.47-0.60; P < .001), and alopecia areata (aOR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.95; P = .001) were significantly lower among those with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris.

Conclusions and Relevance

The results of this cross-sectional study suggest that patients with PPP have an overlapping comorbidity profile with patients with psoriasis vulgaris but not patients with pompholyx. However, the risks of comorbidities among patients with PPP may be substantially different from those among patients with psoriasis vulgaris.

This cross-sectional study uses data from the Korean National Health Insurance database and the National Health Screening Program to assess the risks of comorbidities among patients with palmoplantar pustulosis compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris or pompholyx in Korea.

Introduction

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP), also known as pustulosis palmaris et plantaris, is a chronic relapsing pustular dermatosis affecting the palms and/or soles.1 Its prevalence has been reported as 0.01% to 0.05% in Western countries and 0.12% in Asia.1,2,3 Although the origin of PPP is unclear, recent studies on its immunological and genetic pathogenesis suggest systemic involvement of the disease.4

Whether PPP is a variant of psoriasis or a distinct inflammatory disease remains controversial.5 The disease was previously classified as a clinical subtype of psoriasis.6 However, many epidemiological, genetic, and etiopathogenetic studies have found differences between PPP and psoriasis.7,8

Psoriasis is associated with various systemic diseases.9,10,11 Similar to psoriasis, PPP is occasionally accompanied by systemic conditions, including psoriatic arthritis and autoimmune diseases.1,12,13 However, to our knowledge, the association of comorbidities with PPP has not been evaluated, and adjustment for possible confounders has not been performed.5,14,15 In this study, we assessed the risks of comorbidities among patients with PPP using data from the Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) database; patients with PPP were compared with patients with the 2 major differential diagnoses of PPP: psoriasis vulgaris and pompholyx.1

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

Before beginning this cross-sectional study, we performed a pilot study comparing patients with PPP to a 1:4 age- and sex-matched general population using data from the NHI Service National Sample Cohort, a population-based cohort consisting of 1 million Koreans followed up from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2015 (eMethods in the Supplement).16,17 The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul National University Hospital. The requirement for informed consent was waived because all data were deidentified. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

We conducted a nationwide population-based cross-sectional study using data from the Korean NHI claims database (which records diagnoses based on codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) collected from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2019. Patients diagnosed with PPP, psoriasis vulgaris, or pompholyx who visited a dermatologist between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2019, were enrolled. Data were analyzed from July 1, 2020, to October 31, 2021. The Korean NHI provides data on all NHI claims, including sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses, and results from the National Health Screening Program, comprising regular standardized medical examinations recommended to all insured adults in the country (eMethods in the Supplement).18 Because approximately 98% of the Korean population is covered by the NHI database, it has been used to assess reliable approximations of the prevalence of certain diseases in Korea.19,20

Identification of Study Population

Patients were identified as having PPP, psoriasis vulgaris, or pompholyx if they had 3 or more documented dermatologist visits with a diagnosis of one of those specific diseases recorded between 2010 and 2019. To minimize misclassification, 14 746 patients diagnosed with pompholyx were excluded from the PPP group, and 26 151 patients diagnosed with PPP were excluded from the pompholyx group. Patients with PPP were subclassified according to the presence of concomitant psoriasis vulgaris.

To validate diagnostic accuracy, we examined several algorithms based on the number of dermatologist visits with a diagnosis of PPP, considering that patients with PPP visit clinics regularly like those with other chronic diseases (eMethods and eTable 1 in the Supplement).19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 The algorithm used in our study had a sensitivity of 74.19% and a specificity of 85.71%.

Prevalence of PPP

The prevalence of PPP during the study period was calculated based on the assumption that the entire Korean population in 2015 was at risk. We assessed the age-adjusted prevalence using world standard population data from the World Health Organization for 2000 to 2025.30,31

Assessment of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Age, region of residence, income, insurance type, health-related behaviors (smoking and alcohol consumption), and laboratory data from the National Health Screening Program were obtained from January 1 to December 31, 2015. Because the study population was Korean, assessments according to race and ethnicity were not possible. Detailed criteria for the categorization of variables are summarized in eMethods in the Supplement.

Comorbidities Associated With PPP

We evaluated 4 categories of comorbidities: (1) inflammatory arthritis, (2) cardiometabolic diseases, (3) autoimmune diseases (subdivided into endocrine autoimmune diseases, inflammatory bowel diseases, and connective tissue diseases), and (4) dermatological diseases. Patients were identified as having a certain disease if they had 3 or more physician visits during the study period (2010-2019) with a diagnosis of each disease. Diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, for each disease are provided in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed according to sex and age (<20 years, 20-59 years, and ≥60 years). To assess the robustness of our results, sensitivity analyses were conducted among patients who had 1 or more, 2 or more, 4 or more, and 5 or more dermatologist visits with a diagnosis of PPP, psoriasis vulgaris, or pompholyx recorded during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using t tests, and categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. All continuous data were reported as means with SDs, and categorical data were reported as numbers with percentages.

The primary outcome was the risk of comorbidities in patients with PPP compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris or pompholyx. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the associations between PPP and various clinical factors and comorbidities after adjusting for demographic covariates (age, sex, region of residence, income, and insurance type). The outcomes from the logistic regression analysis were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs.

To minimize potential bias, we conducted an additional analysis with 1:5 propensity score matching. Propensity scores were computed using a nonparsimonious logistic regression model considering demographic covariates. A multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), smoking, and alcohol consumption was performed.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc). Statistical tests were 2-sided, and results were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

Results

A total of 37 399 patients with PPP, 332 279 patients with psoriasis vulgaris, and 365 415 patients with pompholyx in Korea were included (Table 1). Among those with PPP, the mean (SD) age was 48.98 (17.20) years; 51.7% were female, and 48.3% were male. Among those with psoriasis vulgaris, the mean (SD) age was 47.29 (18.34) years; 41.3% were female, and 58.7% were male. Among those with pompholyx, the mean (SD) age was 40.92 (17.63) years; 57.4% were female, and 42.6% were male.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Population.

| Characteristic | No./total No. (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPP | PSV | Standardized difference in PPP vs PSV | Pompholyx | Standardized difference in PPP vs pompholyx | P valueb | |||||

| Without PSV | With PSV | Standardized difference in PSV vs no PSV | P valuea | Total | ||||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||||

| Total participants, No. | 28 978 | 8421 | NA | NA | 37 399 | 332 279 | NA | 365 415 | NA | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 48.22 (17.78) | 51.60 (14.71) | 0.197 | <.001 | 48.98 (17.20) | 47.29 (18.34) | 0.093 | 40.92 (17.63) | 0.459 | <.001 |

| Age group, y | ||||||||||

| 0-19 | 2239/28 978 (7.7) | 224/8421 (2.7) | 0.184 | <.001 | 2463/37 399 (6.6) | 21 953/332 279 (6.6) | 0.085 | 46 321/365 415 (12.7) | 0.431 | <.001 |

| 20-39 | 6255/28 978 (21.6) | 1404/8421 (16.7) | 7659/37 399 (20.5) | 94 288/332 279 (28.4) | 122 374/365 415 (33.5) | |||||

| 40-59 | 12 571/28 978 (43.4) | 4327/8421 (51.4) | 16 898/37 399 (45.2) | 128 051/332 279 (38.5) | 142 378/365 415 (39.0) | |||||

| 60-79 | 7193/28 978 (24.8) | 2299/8421 (27.3) | 9492/37 399 (25.4) | 76 208/332 279 (22.9) | 50 465/365 415 (13.8) | |||||

| ≥80 | 720/28 978 (2.5) | 167/8421 (2.0) | 887/37 399 (2.4) | 11 779/332 279 (3.5) | 3877/365 415 (1.1) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 13 793/28 978 (47.6) | 4287/8421 (50.9) | −0.066 | <.001 | 18 080/37 399 (48.3) | 195 084/332 279 (58.7) | 0.210 | 155 580/365 415 (42.6) | −0.117 | <.001 |

| Female | 15 185/28 978 (52.4) | 4134/8421 (49.1) | 19 319/37 399 (51.7) | 137 195/332 279 (41.3) | 209 835/365 415 (57.4) | |||||

| Region of residence | ||||||||||

| Urban | 14 140/28 940 (48.9) | 3918/8418 (46.5) | 0.071 | <.001 | 18 058/37 358 (48.3) | 153 670/331 883 (46.3) | −0.050 | 174 623/365 167 (47.8) | −0.005 | <.001 |

| Suburban | 12 176/28 940 (42.1) | 3540/8418 (42.1) | 15 716/37 358 (42.1) | 142 147/331 883 (42.8) | 156 319/365 167 (42.8) | |||||

| Rural | 2624/28 940 (9.1) | 960/8418 (11.4) | 3584/37 358 (9.6) | 36 066/331 883 (10.9) | 34 225/365 167 (9.4) | |||||

| Income | ||||||||||

| Low | 7602/28 394 (26.8) | 2346/8233 (28.5) | −0.045 | .03 | 9948/36 627 (27.2) | 84 066/324 260 (25.9) | −0.032 | 85 614/356 078 (24.0) | −0.086 | <.001 |

| Middle | 7403/28 394 (26.1) | 2175/8233 (26.4) | 9578/36 627 (26.2) | 84 112/324 260 (25.9) | 90 081/356 078 (25.3) | |||||

| High | 13 389/28 394 (47.2) | 3712/8233 (45.1) | 17 101/36 627 (46.7) | 156 082/324 260 (48.1) | 180 383/356 078 (50.7) | |||||

| Insurance type | ||||||||||

| Health | 27 781/28 978 (95.9) | 8041/8421 (95.5) | 0.019 | .12 | 35 822/37 399 (95.8) | 318 231/332 279 (95.8) | −0.001 | 355 436/365 415 (97.3) | 0.089 | <.001 |

| Medical aid | 1197/28 978 (4.1) | 380/8421 (4.5) | 1577/37 399 (4.2) | 14 048/332 279 (4.2) | 9979/365 415 (2.7) | |||||

| Clinical | ||||||||||

| Smoking history | ||||||||||

| Nonsmoker | 12 086/22 448 (53.8) | 2913/6945 (41.9) | 0.263 | <.001 | 14 988/29 372 (51.0) | 128 161/252 847 (50.7) | 0.024 | 174 694/270 361 (64.6) | 0.314 | <.001 |

| Ex-smoker | 4083/22 448 (18.2) | 1320/6945 (19.0) | 5402/29 372 (18.4) | 53 473/252 847 (21.1) | 44 310/270 361 (16.4) | |||||

| Current | 6279/22 448 (28.0) | 2712/6945 (39.0) | 8982/29 372 (30.6) | 71 213/252 847 (28.2) | 51 357/270 361 (19.0) | |||||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||||

| Light | 2955/22 437 (13.2) | 965/6944 (13.9) | −0.003 | .11 | 3915/29 360 (13.3) | 32 220/252 761 (12.7) | −0.070 | 39 510/270 235 (14.6) | 0.042 | <.001 |

| Moderate | 15 802/22 437 (70.4) | 4801/6944 (69.1) | 20 603/29 360 (70.2) | 170 430/252 761 (67.4) | 188 917/270 235 (69.9) | |||||

| Heavy | 3680/22 437 (16.4) | 1178/6944 (17.0) | 4842/29 360 (16.5) | 50 111/252 761 (19.8) | 41 808/270 235 (15.5) | |||||

| Weight status | ||||||||||

| Underweight or normal | 13 842/22 453 (61.6) | 4194/6946 (60.4) | 0.026 | .16 | 18 023/29 378 (61.3) | 157 313/252 963 (62.2) | 0.017 | 178 724/270 472 (66.1) | 0.097 | <.001 |

| Overweight | 7281/22 453 (32.4) | 2320/6946 (33.4) | 9594/29 378 (32.7) | 80 976/252 963 (32.0) | 78 011/270 472 (28.8) | |||||

| Obese | 1330/22 453 (5.9) | 432/6946 (6.2) | 1761/29 378 (6.0) | 14 674/252 963 (5.8) | 13 737/270 472 (5.1) | |||||

Abbreviations: PPP, palmoplantar pustulosis; PSV, psoriasis vulgaris.

P value was calculated by comparing 2 groups (PPP without PSV and PPP with PSV) using a t test for continuous variables and a χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

P value was calculated by comparing 3 groups (PPP, PSV, and pompholyx) using analysis of variance for continuous variables and a χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Prevalence of PPP

Patients aged 40 to 59 years represented 45.2% of all patients with PPP (Table 1; eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The unadjusted prevalence of PPP was 72.58 patients per 100 000 persons (95% CI, 71.84-73.31 patients per 100 000 persons), and the standardized prevalence (adjusted in terms of the world standard population) was 58.60 patients per 100 000 persons (95% CI, 57.97-59.23 patients per 100 000 persons) (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Clinical Characteristics of Patients With PPP

Among patients with PPP, 49.0% had a history of smoking (ie, ex-smoker or current smoker), 16.5% drank alcohol heavily, and 38.7% were overweight or obese. Of those with PPP, 22.5% had psoriasis vulgaris. Compared with patients without psoriasis vulgaris, those with psoriasis vulgaris were older (mean [SD], 51.60 [14.71] years vs 48.22 [17.78] years; P < .001), and fewer were women (49.1% vs 52.4%; P < .001). More patients who had PPP with psoriasis vulgaris were current smokers (39.0%) compared with those without psoriasis vulgaris (28.0%; P < .001). No significant difference in alcohol consumption or obesity was found between the 2 groups (Table 1). Similar results were found in a pilot study comparing patients with PPP with the general population (eResults and eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Risk Factors of PPP vs Psoriasis Vulgaris and Pompholyx

We assessed the risk of developing PPP compared with the risk of developing pompholyx or psoriasis vulgaris based on the presence of various conditions (Table 2; eTable 5 in the Supplement). A logistic analysis adjusted for demographic covariates revealed that current smokers and individuals with obesity had a higher risk of developing PPP than pompholyx (current smoking: adjusted OR [aOR], 2.44 [95% CI, 2.35-2.53; P < .001]; obesity: aOR, 1.30 [95% CI, 1.24-1.37; P < .001]) or psoriasis vulgaris (current smoking: aOR, 1.71 [95% CI, 1.65-1.77; P < .001]; obesity: aOR, 1.09 [95% CI, 1.04-1.15; P = .001]). Patients who drank heavily had a higher risk of developing PPP than pompholyx (aOR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.08-1.19; P < .001) and a lower risk of developing PPP than psoriasis vulgaris (aOR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96; P < .001). Higher levels of glucose (eg, ≥126 mg/dL [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555]: aOR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.41-1.55; P < .001), cholesterol (eg, ≥240 mg/dL [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259]: aOR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.15-1.24; P < .001), and triglycerides (eg, ≥500 mg/dL [to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113]: aOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62; P < .001) were associated with a higher risk of developing PPP than pompholyx.

Table 2. Risk of PPP vs Pompholyx or Psoriasis Vulgaris Among Patients With Various Conditions.

| Characteristic | PPP vs pompholyx | PPP vs PSV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysisa | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysisa | |||||

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Smoking history | ||||||||

| Nonsmoker | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Ex-smoker | 1.42 (1.38-1.47) | <.001 | 1.54 (1.48-1.60) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.84-0.89) | <.001 | 1.34 (1.29-1.39) | <.001 |

| Current | 2.04 (1.98-2.10) | <.001 | 2.44 (2.35-2.53) | <.001 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | <.001 | 1.71 (1.65-1.77) | <.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||||

| Light | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Moderate | 1.10 (1.06-1.14) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | .66 | 1.00 (0.96-1.03) | .78 | 1.00 (0.97-1.04) | .78 |

| Heavy | 1.17 (1.12-1.22) | <.001 | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | <.001 | 0.80 (0.76-0.83) | <.001 | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) | <.001 |

| Weight status | ||||||||

| Underweight or normal | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Overweight | 1.22 (1.19-1.25) | <.001 | 1.08 (1.05-1.11) | <.001 | 1.03 (1.01-1.06) | .01 | 1.09 (1.06-1.12) | <.001 |

| Obese | 1.27 (1.21-1.34) | <.001 | 1.30 (1.24-1.37) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | .08 | 1.09 (1.04-1.15) | .001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||||||

| <140 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| ≥140 | 1.46 (1.40-1.53) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.05-1.15) | <.001 | 0.91 (0.87-0.95) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.84-0.92) | <.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | ||||||||

| <100 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 100-125 | 1.39 (1.35-1.43) | <.001 | 1.14 (1.11-1.17) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.06-1.13) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) | <.001 |

| ≥126 | 2.06 (1.97-2.15) | <.001 | 1.48 (1.41-1.55) | <.001 | 1.15 (1.10-1.20) | <.001 | 1.14 (1.10-1.20) | <.001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | ||||||||

| <200 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 200-239 | 1.14 (1.11-1.17) | <.001 | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | <.001 | 1.10 (1.07-1.13) | <.001 | 1.09 (1.05-1.12) | <.001 |

| ≥240 | 1.33 (1.28-1.38) | <.001 | 1.19 (1.15-1.24) | <.001 | 1.16 (1.12-1.21) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.08-1.17) | <.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | ||||||||

| <150 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 150-199 | 1.45 (1.40-1.51) | <.001 | 1.27 (1.22-1.32) | <.001 | 1.08 (1.04-1.12) | <.001 | 1.12 (1.08-1.17) | <.001 |

| 200-499 | 1.60 (1.55-1.66) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.36-1.46) | <.001 | 1.08 (1.04-1.12) | <.001 | 1.18 (1.14-1.22) | <.001 |

| ≥500 | 1.51 (1.33-1.72) | <.001 | 1.43 (1.25-1.62) | <.001 | 0.83 (0.73-0.94) | .004 | 0.99 (0.87-1.12) | .81 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PPP, palmoplantar pustulosis; PSV, psoriasis vulgaris.

SI conversion factors: To convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555; to convert cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113.

Adjusted by age, sex, region of residence, income, and insurance type.

Comorbidities in Patients With PPP vs Psoriasis Vulgaris and Pompholyx

The prevalence of comorbidities in the PPP, psoriasis vulgaris, and pompholyx groups are presented in eTable 6 in the Supplement. After adjustment for demographic covariates, patients with PPP had a significantly higher risk of developing psoriasis vulgaris (aOR, 72.96 [68.19-78.05]; P < .001), psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 8.06; 95% CI, 6.55-9.92; P < .001), ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.61-2.27; P < .001), type 1 diabetes (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.16-1.52; P < .001), type 2 diabetes (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.29-1.38; P < .001), Graves disease (aOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11-1.42; P < .001), Crohn disease (aOR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.11-2.40; P = .01), and vitiligo (aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.65-2.12; P < .001) compared with patients with pompholyx (Figure 1A). The risks of ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.62; P < .001) and Graves disease (aOR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.23-1.58; P < .001) were higher in patients with PPP compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris (Figure 1B). However, the risks of psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 0.54; 94% CI, 0.47-0.63; P < .001), systemic lupus erythematosus (aOR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.97; P = .04), Sjögren syndrome (aOR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.50-0.96; P = .03), systemic sclerosis (aOR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.11-0.77; P = .01), vitiligo (aOR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.47-0.60; P < .001), and alopecia areata (aOR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81-0.95; P = .001) were lower among patients with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris. The risk of Crohn disease was higher among those with PPP (aOR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.93-1.98) vs those with psoriasis vulgaris, although this difference was statistically insignificant (P = .11).

Figure 1. Risk of Comorbidities Among Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis vs Patients With Pompholyx or Psoriasis Vulgaris.

Odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted for demographic covariates (age, sex, region of residence, income, and insurance type). Outlier values over the range of plots were omitted. Arrows indicate 95% CI values that were beyond those shown on the x-axis. The analysis included 37 399 patients in the palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) group, 365 415 patients in the pompholyx group, and 332 279 patients in the psoriasis vulgaris group.

Analyses of propensity score–matched patients yielded consistent results. We selected 5 patients with psoriasis vulgaris and 5 patients with pompholyx for propensity score matching based on demographic covariates. After matching, covariates were comparable between the groups in each comparison (eTable 7 and eTable 8 in the Supplement). The risks of psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 7.62; 95% CI, 5.90-9.85; P < .001), ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.52-2.30; P < .001), type 1 diabetes (aOR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.15-1.57; P < .001), type 2 diabetes (aOR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.23-1.34; P < .001), Crohn disease (aOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.10-2.62; P = .02), and vitiligo (aOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.64-2.22; P < .001) were significantly higher in patients with PPP than in those with pompholyx after adjusting for body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption. Compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris, patients with PPP had higher risks of ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.11-1.61; P = .002), Graves disease (aOR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.55; P < .001), and Crohn disease (aOR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.10-2.59; P = .02) and lower risks of psoriatic arthritis (aOR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.41-0.57; P < .001), Sjögren syndrome (aOR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.44-0.96; P = .03), systemic sclerosis (aOR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.12-0.92; P = .03), vitiligo (aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.48-0.62; P < .001), and alopecia areata (aOR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.79-0.94; P = .001). The risk of cardiometabolic diseases was comparable (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

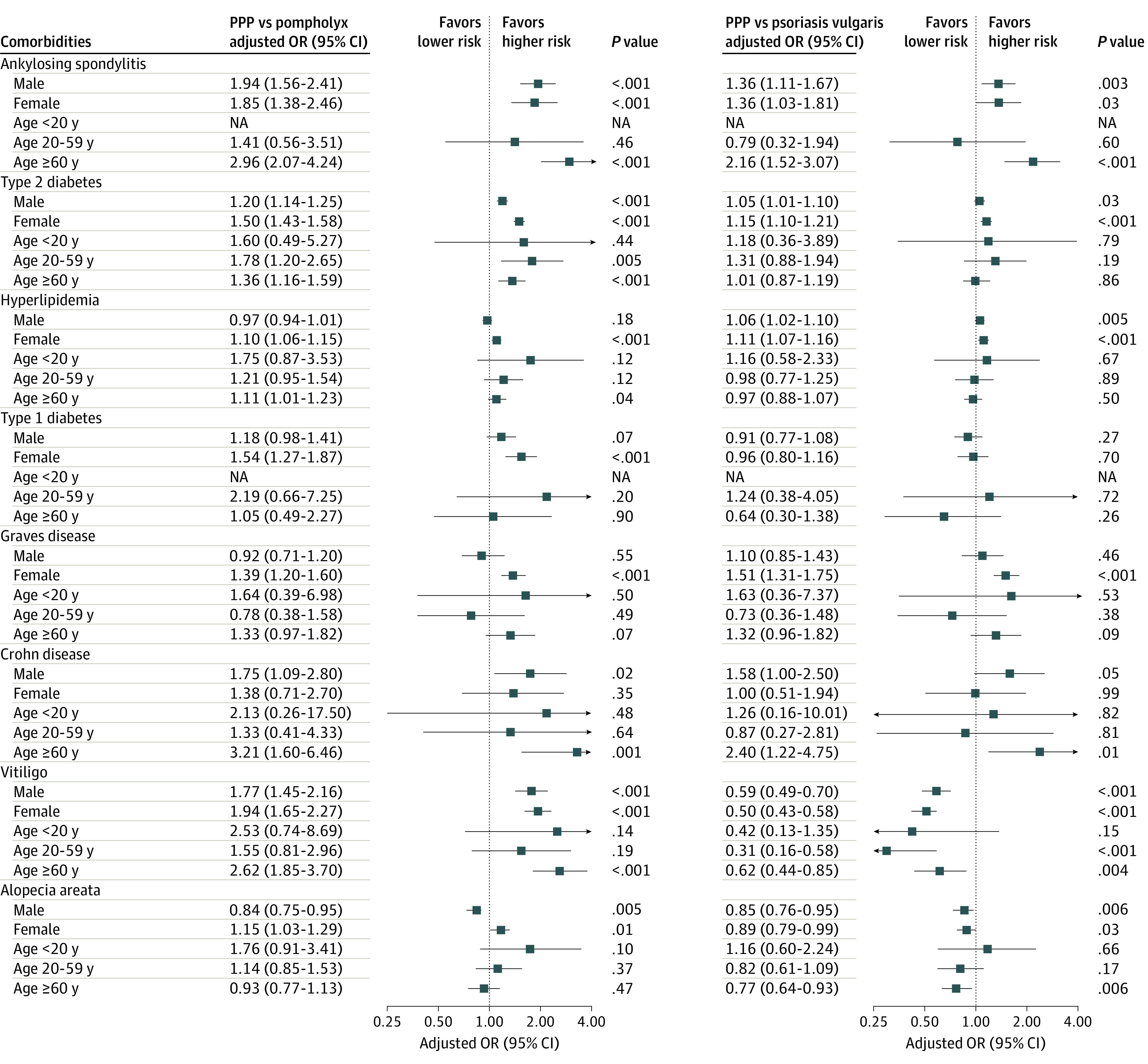

Subgroup analyses revealed differences in comorbidities according to sex and age (eTable 9 in the Supplement). Compared with patients with pompholyx, male patients with PPP had a significantly higher risk of Crohn disease (aOR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.09-2.80; P = .02), and female patients with PPP had significantly higher risks of hyperlipidemia (aOR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.06-1.15; P < .001), type 1 diabetes (aOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.27-1.87; P < .001), and Graves disease (aOR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.20-1.60; P < .001); the risk of alopecia areata was higher in women with PPP (aOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03-1.29; P = .01) and lower in men with PPP (aOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.75-0.95; P = .005). Compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris, male patients with PPP had a higher risk of Crohn disease (aOR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.00-2.50; P = .049), whereas female patients with PPP had a higher risk of Graves disease (aOR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.31-1.75; P < .001).

In the subgroup analysis by age, the risks of ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 2.96; 95% CI, 2.07-4.24; P < .001), Crohn disease (aOR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.60-6.46; P = .001), and vitiligo (aOR, 2.62; 95% CI, 1.85-3.70; P < .001) were significantly higher in patients with PPP who were 60 years and older compared with patients with pompholyx. The risks of ankylosing spondylitis (aOR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.52-3.07; P < .001) and Crohn disease (aOR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.22-4.75; P = .01) were higher in patients with PPP who were 60 years and older compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Although statistically insignificant, the risks of hyperlipidemia and alopecia areata were higher in younger patients with PPP vs patients with pompholyx (eg, hyperlipidemia at age <20 years: aOR, 1.75 [95% CI, 0.87-3.53; P = .12]; alopecia areata at age <20 years: aOR, 1.76 [95% CI, 0.91-3.41; P = .10]) or psoriasis vulgaris (hyperlipidemia at age <20 years: aOR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.58-2.33; P = .67]; alopecia areata at age <20 years: aOR, 1.16 [95% CI, 0.60-2.24; P = .66]) (Figure 2). Additional subgroup analyses in propensity score–matched patients yielded consistent results (eFigure 3 and eTable 10 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Subgroup Analysis by Sex and Age.

Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were adjusted for demographic covariates (age, sex, region of residence, income, and insurance type). Outlier values over the range of plots were omitted. Arrows indicate 95% CI values that were beyond those shown on the x-axis. Not applicable (NA) indicates aOR could not be calculated because there was no patient in certain subgroups. PPP indicates palmoplantar pustulosis.

All sensitivity analyses of the study populations by number of dermatologist visits with certain diagnoses consistently revealed that the risks of psoriatic arthritis (eg, ≥5 visits: aOR, 8.73; 95% CI, 6.82-11.18; P < .001), ankylosing spondylitis (≥5 visits: aOR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.73-2.63; P < .001), type 2 diabetes (≥5 visits: aOR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.31-1.43; P < .001), Graves disease (≥5 visits: aOR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.32-1.75; P < .001), and vitiligo (≥5 visits: aOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.68-2.24; P < .001) were higher in patients with PPP compared with patients with pompholyx. The risks of ankylosing spondylitis (eg, ≥5 visits: aOR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.17-1.72; P < .001) and Graves disease (≥5 visits: aOR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.44-1.91; P < .001) were higher in patients with PPP compared with those with psoriasis vulgaris, whereas the risks of psoriatic arthritis (≥5 visits: aOR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.44-0.61; P < .001) and vitiligo (≥5 visits: aOR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.47-0.61; P < .001) were lower in those with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris (eTables 11-14 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study found that the prevalence and age distribution of PPP in Korea were comparable to data reported in previous studies.1,2,3,12,32,33 Unlike previous studies, the male to female ratio in the current study was relatively even, which may be a result of differences in study design, sample size, or participant race.12,14,32,34 Further studies on the prevalence of PPP by sex are warranted.

Smoking and obesity were significant risk factors associated with PPP in the pilot study, and the aORs for smoking and obesity were higher among patients with PPP than those with pompholyx in the main study, which was consistent with findings from previous studies.1,35,36 We found higher aORs between smoking and PPP than between smoking and psoriasis vulgaris. Smoking can induce both PPP and psoriasis through oxidative, inflammatory, and genetic mechanisms.37,38 The overexpressed α-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the eccrine gland of patients with PPP may explain the higher aOR between smoking and PPP.32,39

We found an increased risk of psoriasis vulgaris in patients with PPP compared with patients with pompholyx. The common pathogenesis of these diseases further supports an association between PPP and psoriasis. However, immunological and genetic differences have been reported.4,40 Expression of interleukin 17 was increased in PPP lesions compared with healthy skin, whereas expression of interleukin 12/23 was not.41 The biologic therapies that target these cytokines in psoriasis vulgaris are often ineffective for the treatment of PPP.1,42,43,44 Genetic studies have reported that interleukin 36RN, the AP1S3 gene, and the CARD14 gene may be associated with PPP, whereas the PSORS1 gene is not, unlike psoriasis vulgaris.1,4,34 Because of these differences in underlying pathogenesis, PPP and psoriasis vulgaris would be expected to have both similarities and differences in their comorbidities.

Pompholyx is a common vesicobullous disorder that resembles PPP clinically and histopathologically.45 Systemic involvement of pompholyx is rare; only a few skin conditions (eg, atopic dermatitis and contact sensitivity) and infections (eg, herpes zoster) have been reported to be associated with pompholyx.46,47 Therefore, we assumed that estimating the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP compared with the risks of comorbidities in the general population would be similar to comparing the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP vs pompholyx, which was confirmed through the pilot study.

Joint diseases have been frequently reported in patients with PPP,14,34 and psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis were associated with PPP in the current study. We found a decreased risk of psoriatic arthritis in patients with PPP compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Contrary to scarce reports of ankylosing spondylitis in patients with PPP,33 our study found the risk of ankylosing spondylitis was significantly higher in patients with PPP vs psoriasis vulgaris. The spinal column is commonly affected in articular syndromes, such as synovitis-acne-pustulosis-hyperostosis-osteomyelitis syndrome and pustulotic arthro-osteitis, that are accompanied by PPP, which suggests PPP is associated with spondyloarthritis.1,34,48

Consistent with previous reports,2,13,14,34,49 the risk of cardiometabolic diseases was higher in patients with PPP compared with patients with pompholyx. We found that the risk of type 2 diabetes was higher in patients with PPP compared with propensity score–matched patients with pompholyx, even after adjusting for body mass index, smoking, and alcohol consumption. In addition, the risk of cardiometabolic diseases in patients with PPP was comparable with that in propensity score–matched patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Therefore, PPP may be an independent risk factor associated with cardiometabolic diseases, similar to psoriasis vulgaris.50,51

We found that type 1 diabetes, Graves disease, and Crohn disease were associated with PPP. This finding was consistent with previous studies reporting that PPP is associated with several autoimmune diseases.4,13,52 The risks of Graves disease and Crohn disease were higher in patients with PPP, whereas the risks of Hashimoto thyroiditis and ulcerative colitis were not. This finding may be partially explained by the opposing consequences of smoking for the immune system.53,54 Smokers have higher risks of Crohn disease and Graves disease and lower risks of ulcerative colitis and Hashimoto thyroiditis.55,56 Shared immune pathways may contribute to the pathogenesis of psoriasis and connective tissue diseases.57,58,59 However, in our study, the risk of connective tissue diseases was lower in patients with PPP than in those with psoriasis vulgaris, implying that PPP and psoriasis vulgaris have different immunopathogenesis.

Patients with PPP had a higher risk of vitiligo than patients with pompholyx and a lower risk than patients with psoriasis vulgaris. The association between PPP and vitiligo has been rarely reported compared with the association between psoriasis and vitiligo.60,61 The association between psoriasis and vitiligo may be explained by the common T cell–mediated autoimmunity or Koebner phenomenon.60,62 The immunopathogenic differences from psoriasis and the less pronounced Koebner phenomenon in PPP may explain the decreased risk of vitiligo in patients with PPP vs those with psoriasis vulgaris.63,64

In our study, the risk of autoimmune diseases (with the exception of Crohn disease) was higher in female patients with PPP, which is consistent with the male predominance of Crohn disease in Asia.55 The risk of cardiometabolic diseases in patients with PPP was higher in female vs male individuals. The risks of hyperlipidemia and alopecia areata in patients with PPP was higher in the younger (<20 years) population, although these risks were not statistically significant. These age and sex discrepancies require further study.

This study’s results were confirmed using 2 different statistical approaches (multivariable logistic regression analysis and analysis using propensity score matching). Multivariable regression analysis has an advantage because it simultaneously controls for many confounders. However, it might produce biased aORs, particularly when assessing rare comorbidities. Analysis using propensity score matching produces less biased, more robust, and more precise estimates, even when assessing rare events.65 However, it has the potential weaknesses of residual confounding and loss of statistical efficiency.66,67 The consistency of these 2 approaches increased the reliability of the results.66

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because the NHI claims database was used, misdiagnoses might have been included, and patients with subclinical or minimal disease might have been undetected. To overcome these limitations, we included only diagnoses made by dermatologists and defined strict diagnostic criteria based on validation. Second, disease severity and treatment modality were not recorded; thus, we could not adjust for those factors. Third, the study population was Korean, and further studies involving other ethnic groups are needed for generalizability. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this study is one of the largest epidemiological analyses of PPP and the first to report adjusted risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP compared with patients with psoriasis vulgaris.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, patients with PPP had an overlapping comorbidity profile (including inflammatory arthritis, cardiometabolic diseases, autoimmune diseases, and vitiligo) with patients with psoriasis vulgaris but not with patients with pompholyx. However, the risks of comorbidities in patients with PPP compared with those with psoriasis vulgaris revealed substantial differences; among patients with PPP, the risks of ankylosing spondylitis and Graves disease were higher, and the risks of psoriatic arthritis, connective tissue diseases, and vitiligo were lower. Further studies to explore the pathogenetic mechanisms of these comorbidities and elucidate their associations with PPP are warranted.

eMethods. Data Sources, Validation of Diagnostic Accuracy, and Categorization of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

eResults. Pilot Study

eTable 1. Validation Algorithms of PPP

eTable 2. List of Collected ICD-10 Codes of Studied Diseases and Comorbidities

eTable 3. Period Prevalence of Palmoplantar Pustulosis in Korea (2010-2019)

eTable 4. Comparison Between Patients With PPP and Age- and Sex-Matched Controls Without PPP in the NHIS-NSC

eTable 5. Risk of Palmoplantar Pustulosis in Various Conditions Compared With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris

eTable 6. Prevalence of Comorbidities in Palmoplantar Pustulosis, Psoriasis Vulgaris, and Pompholyx

eTable 7. Comparison Between Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Propensity Score–Matched Controls With Pompholyx

eTable 8. Comparison Between Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Propensity Score–Matched Controls With Psoriasis Vulgaris

eTable 9. Subgroup Analysis Comparing Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis With Patients With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris by Sex and Age

eTable 10. Subgroup Analysis Comparing Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis With Propensity Score–Matched Patients With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris by Sex and Age

eTable 11. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 1 or More Documented Dermatologist Visit During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 12. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 2 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 13. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 4 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 14. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 5 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eFigure 1. Distribution and Prevalence of Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis by Age and Sex in the Korean Population

eFigure 2. Forest Plots of the Risks of Comorbidities in Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis Compared With Propensity Score–Matched Patients With Pompholyx or Psoriasis Vulgaris

eFigure 3. Subgroup Analysis by Sex and Age After Propensity Score Matching

References

- 1.Misiak-Galazka M, Zozula J, Rudnicka L. Palmoplantar pustulosis: recent advances in etiopathogenesis and emerging treatments. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(3):355-370. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00503-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006450. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JY, Kang S, Park JS, Jo SJ. Prevalence of psoriasis in Korea: a population-based epidemiological study using the Korean National Health Insurance Database. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(6):761-767. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.6.761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murakami M, Terui T. Palmoplantar pustulosis: current understanding of disease definition and pathomechanism. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98(1):13-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunasso AMG, Massone C. Psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: an endless debate? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(7):e335-e337. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, et al. ; ERASPEN Network . European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1792-1799. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misiak-Galazka M, Wolska H, Rudnicka L. Is palmoplantar pustulosis simply a variant of psoriasis or a distinct entity? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(7):e342-e343. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Waal AC, van de Kerkhof PCM. Pustulosis palmoplantaris is a disease distinct from psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22(2):102-105. doi: 10.3109/09546631003636817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and treatment of psoriasis: a review. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1945-1960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho SI, Kim YE, Jo SJ. Association of metabolic comorbidities with pediatric psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Dermatol. 2021;33(3):203-213. doi: 10.5021/ad.2021.33.3.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lønnberg AS, Skov L, Skytthe A, Kyvik KO, Pedersen OB, Thomsen SF. Association of psoriasis with the risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(7):761-767. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trattner H, Blüml S, Steiner I, Plut U, Radakovic S, Tanew A. Quality of life and comorbidities in palmoplantar pustulosis—a cross-sectional study on 102 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(10):1681-1685. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becher G, Jamieson L, Leman J. Palmoplantar pustulosis—a retrospective review of comorbid conditions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(9):1854-1856. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunasso AMG, Puntoni M, Aberer W, Delfino C, Fancelli L, Massone C. Clinical and epidemiological comparison of patients affected by palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a case series study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(6):1243-1251. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YE, Jo SJ. [Clinical characteristics of palmoplantar pustulosis patients in Korea: a single-center retrospective study]. J Korean Soc Psoriasis. 2020;17(1):5-9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Lee JS, Park SH, Shin SA, Kim K. Cohort profile: the National Health Insurance Service–National Sample Cohort (NHIS-NSC), South Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):e15. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boo S, Yoon YJ, Oh H. Evaluating the prevalence, awareness, and control of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia in Korea using the NHIS-NSC database: a cross-sectional analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(51):e13713. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24(1):63-71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin JW, Kang T, Lee JS, et al. Time-dependent risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with alopecia areata in Korea. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(7):763-771. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JH, Kwon HS, Jung HM, Kim GM, Bae JM. Prevalence and comorbidities associated with hidradenitis suppurativa in Korea: a nationwide population-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(10):1784-1790. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noe MH, Wan MT, Mostaghimi A, et al. ; Pustular Psoriasis in the US Research Group . Evaluation of a case series of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(1):68-72. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ham SP, Oh JH, Park HJ, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes for identification of psoriasis patients in Korea. Ann Dermatol. 2020;32(2):115-121. doi: 10.5021/ad.2020.32.2.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung JM, Lee KH, Kim YJ, et al. Assessment of overall and specific cancer risks in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):844-853. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, Khan N, Walker R, Quan H. Validating ICD coding algorithms for diabetes mellitus from administrative data. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(2):189-195. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, Avina-Zubieta JA. Validity of heart failure diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park J, Kwon S, Choi EK, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes of major clinical outcomes in a national health insurance database. Int J Arrhythm. 2019;20:5. doi: 10.1186/s42444-019-0005-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang KL, Yeh CC, Wu SI, et al. Risk of dementia among individuals with psoriasis: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(3):18m12462. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18m12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauden A, Geishin A, Merzon E, et al. Higher rates of allergies, autoimmune diseases and low-grade inflammation markers in treatment-resistant major depression. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tung TH, Hsiao YY, Shen SA, Huang C. The prevalence of mental disorders in Taiwanese prisons: a nationwide population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(3):379-386. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1614-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. World Health Organization; 2001. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf

- 31.Cho SH, Kang G, Kim HC. Illustration of calculating standardized rates utilizing logistic regression models: the National Health Insurance Service–National Health Screening Cohort (NHIS-HEALS). J Health Info Stat. 2017;42(1):70-76. doi: 10.21032/jhis.2017.42.1.70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang CM, Tsai TF. Clinical characteristics, genetics, comorbidities and treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis: a retrospective analysis of 66 cases in a single center in Taiwan. J Dermatol. 2020;47(9):1046-1049. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oktem A, Uysal PI, Akdoğan N, Tokmak A, Yalcin B. Clinical characteristics and associations of palmoplantar pustulosis: an observational study. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95(1):15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2019.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misiak-Galazka M, Wolska H, Rudnicka L. What do we know about palmoplantar pustulosis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(1):38-44. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Doherty CJ, MacIntyre C. Palmoplantar pustulosis and smoking. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291(6499):861-864. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6499.861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benzian-Olsson N, Dand N, Chaloner C, et al. ; ERASPEN Consortium and the APRICOT and PLUM Study Team . Association of clinical and demographic factors with the severity of palmoplantar pustulosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(11):1216-1222. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engin B, Aşkın Ö, Tüzün Y. Palmoplantar psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(1):19-27. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(2):304-314. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagforsen E, Edvinsson M, Nordlind K, Michaëlsson G. Expression of nicotinic receptors in the skin of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146(3):383-391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04640.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, Okuyama R. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45(3):264-272. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bissonnette R, Nigen S, Langley RG, et al. Increased expression of IL-17A and limited involvement of IL-23 in patients with palmo-plantar (PP) pustular psoriasis or PP pustulosis; results from a randomised controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(10):1298-1305. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poortinga S, Balakirski G, Kromer C, et al. The challenge of palmoplantar pustulosis therapy: are interleukin-23 inhibitors an option? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(12):e907-e911. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Terui T, Kobayashi S, Okubo Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in Japanese patients with palmoplantar pustulosis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(10):1153-1161. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong AW, Puig L, Joshi A, et al. Comparison of biologics and oral treatments for plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):258-269. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Masuda-Kuroki K, Murakami M, Kishibe M, et al. Diagnostic histopathological features distinguishing palmoplantar pustulosis from pompholyx. J Dermatol. 2019;46(5):399-408. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wollina U. Pompholyx: a review of clinical features, differential diagnosis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11(5):305-314. doi: 10.2165/11533250-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsu CY, Wang YC, Kao CH. Dyshidrosis is a risk factor for herpes zoster. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(11):2177-2183. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hung CT, Wu BY. Palmoplantar pustulosis presenting with chest pain. synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(4):475-480. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.1998a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Misiak-Galazka M, Wolska H, Galazka A, Kwiek B, Rudnicka L. General characteristics and comorbidities in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2018;26(2):109-118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377-390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold KA, Treister AD, Lio PA, Alenghat FJ. Association of atherosclerosis prevalence with age, race, and traditional risk factors in patients with psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(5):622-623. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hagforsen E, Pihl-Lundin I, Michaëlsson K, Michaëlsson G. Calcium homeostasis and body composition in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(1):74-81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10622.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(3):J258-J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nizri E, Irony-Tur-Sinai M, Lory O, Orr-Urtreger A, Lavi E, Brenner T. Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory system by nicotine attenuates neuroinflammation via suppression of Th1 and Th17 responses. J Immunol. 2009;183(10):6681-6688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mak WY, Zhao M, Ng SC, Burisch J. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: east meets west. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(3):380-389. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiersinga WM. Smoking and thyroid. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;79(2):145-151. doi: 10.1111/cen.12222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bunte K, Beikler T. Th17 cells and the IL-23/IL-17 axis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3394. doi: 10.3390/ijms20143394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akiyama S, Sakuraba A. Distinct roles of interleukin-17 and T helper 17 cells among autoimmune diseases. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100104. doi: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2021.100104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto T. Psoriasis and connective tissue diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(16):5803. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sandhu K, Kaur I, Kumar B. Psoriasis and vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(1):149-150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carubbi F, Chimenti MS, Blasetti G, et al. Association of psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis with autoimmune diseases: the experience of two Italian integrated dermatology/rheumatology outpatient clinics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(11):2160-2168. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aghamajidi A, Raoufi E, Parsamanesh G, et al. The attentive focus on T cell–mediated autoimmune pathogenesis of psoriasis, lichen planus and vitiligo. Scand J Immunol. 2021;93(4):e13000. doi: 10.1111/sji.13000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamamoto T. Extra-palmoplantar lesions associated with palmoplantar pustulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(11):1227-1232. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamamoto T, Yokozeki H, Tsuboi R. Koebner’s phenomenon associated with palmoplantar pustulosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21(7):990-992. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cepeda MS, Boston R, Farrar JT, Strom BL. Comparison of logistic regression versus propensity score when the number of events is low and there are multiple confounders. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(3):280-287. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shiba K, Kawahara T. Using propensity scores for causal inference: pitfalls and tips. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(8):457-463. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20210145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seeger JD, Williams PL, Walker AM. An application of propensity score matching using claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(7):465-476. doi: 10.1002/pds.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Data Sources, Validation of Diagnostic Accuracy, and Categorization of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

eResults. Pilot Study

eTable 1. Validation Algorithms of PPP

eTable 2. List of Collected ICD-10 Codes of Studied Diseases and Comorbidities

eTable 3. Period Prevalence of Palmoplantar Pustulosis in Korea (2010-2019)

eTable 4. Comparison Between Patients With PPP and Age- and Sex-Matched Controls Without PPP in the NHIS-NSC

eTable 5. Risk of Palmoplantar Pustulosis in Various Conditions Compared With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris

eTable 6. Prevalence of Comorbidities in Palmoplantar Pustulosis, Psoriasis Vulgaris, and Pompholyx

eTable 7. Comparison Between Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Propensity Score–Matched Controls With Pompholyx

eTable 8. Comparison Between Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis and Propensity Score–Matched Controls With Psoriasis Vulgaris

eTable 9. Subgroup Analysis Comparing Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis With Patients With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris by Sex and Age

eTable 10. Subgroup Analysis Comparing Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis With Propensity Score–Matched Patients With Pompholyx and Psoriasis Vulgaris by Sex and Age

eTable 11. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 1 or More Documented Dermatologist Visit During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 12. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 2 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 13. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 4 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eTable 14. Sensitivity Analysis of Patients With 5 or More Documented Dermatologist Visits During Study Period With a Diagnosis of PPP, PSV, or Pompholyx

eFigure 1. Distribution and Prevalence of Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis by Age and Sex in the Korean Population

eFigure 2. Forest Plots of the Risks of Comorbidities in Patients With Palmoplantar Pustulosis Compared With Propensity Score–Matched Patients With Pompholyx or Psoriasis Vulgaris

eFigure 3. Subgroup Analysis by Sex and Age After Propensity Score Matching