Abstract

Obesity is a disease characterized by the exacerbated increase of adipose tissue. A possible way to decrease the harmful effects of excessive adipose tissue is to increase the thermogenesis process, to the greater energy expenditure generated by the increase in heat in the body. In adipose tissue, the thermogenesis process is the result of an increase in mitochondrial work, having as substrate H+ ions, and which is related to the increased activity of UCP1. Evidence shows that stress is responsible for increasing the greater induction of UCP1 expression via β-adrenergic receptors. It is known that physical exercise is an important implement for sympathetic stimulation promoting communication between norepinephrine/epinephrine with membrane receptors. Thus, the present study investigates the influence of short-term strength training (STST) on fatty acid composition, lipolysis, lipogenesis, and browning processes in the subcutaneous adipose tissue (sWAT) of obese mice. For this, Swiss mice were divided into three groups: lean control, obesity sedentary, and obese strength training (OBexT). Obese animals were fed a high-fat diet for 14 weeks. Trained obese animals were submitted to 7 days of strength exercise. It was demonstrated that STST sessions were able to reduce fasting glycemia. In the sWAT, the STST was able to decrease the levels of the long-chain fatty acids profile, saturated fatty acid, and palmitic fatty acid (C16:0). Moreover, it was showed that STST did not increase protein levels responsible for lipolysis, the ATGL, ABHD5, pPLIN1, and pHSL. On the other hand, the exercise protocol decreased the expression of the lipogenic enzyme SCD1. Finally, our study demonstrated that the STST increased browning process-related genes such as PGC-1α, PRDM16, and UCP1 in the sWAT. Interestingly, all these biomolecular mechanisms have been observed independently of changes in body weight. Therefore, it is concluded that short-term strength exercise can be an effective strategy to initiate morphological changes in sWAT.

Subject terms: Cell signalling, Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Diabetes, Diabetes complications, Type 2 diabetes, RNA metabolism, Endocrine system and metabolic diseases, Obesity, Cell biology, Molecular biology, Diseases, Endocrinology, Disease prevention, Nutrition

Introduction

Obesity is a pandemic condition affecting different populations worldwide, exceeding one billion people1,2. It is a disease characterized mainly by a disruption in insulin signaling in the hypothalamus and peripheral tissues, culminating in exacerbated body fat accumulation by changes in food intake and energy expenditure, which leads to several physiological and molecular disarrangement3. The increment of fatty acids in the adipose tissue exacerbates the subclinical inflammatory process associated with saturated fatty acid intake, leading to the decrease of insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake, which can culminate in diseases such as type 2 diabetes4,5.

In this sense, increasing the thermogenesis process can be a strategy to reduce the harmful effects of adipose tissue accumulation6. This is due to the greater energy expenditure generated by the increase in heat in the body7,8. In adipose tissue, the thermogenesis process is the result of an increase in mitochondrial work, having as substrate H+ ions, which is processed by uncoupling proteins (UCPs)7,8. The process occurs due to increased activity of the uncoupling protein-1 (UCP1), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARγ), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α), and PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16) on brown adipose tissue (BAT)9,10. Therefore, due to pharmacological effects, stress, hypothermia, and physical exercise, the subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT) can undergo modifications, such as increasing the UCP1 and PGC-1α levels and thermogenesis11–13. This molecular process is known as the browning of sWAT, and originates a new adipose tissue, the beige adipose tissue14,15. Derived from white adipose tissue, beige adipose tissue has similar molecular characteristics to BAT16.

Consequently, knowing molecules that can stimulate mainly UCP1 expression becomes important to increase the range of strategies to fight against obesity and diabetes15,17. Knowing this, Granneman et al. investigated the effects of β-adrenergic receptor stimulant (CL316,243) in mice C57BL/6, the authors observed that regardless of the increase in UCP1 expression, there was a temporary increase in fatty acid esterification, fatty acid catabolism, and glycerol metabolism after 7 days of intervention characteristic aspects of de novo lipogenesis (DNL)18. In contrast, Guilherme and colleagues observed that the absence of FASN (FASNKO) production reduces the differentiation of white adipose tissue and the increase of thermogenesis in FASNflox/flox mice, however, when treated β-adrenergic receptor stimulant (CL316,243) and exposed to a temperature of 22 °C the animals were able to promote greater activation of the sympathetic nerves increasing the activity of de novo lipogenesis in iWAT19. In addition, the author also observed the increased differentiation of white adipose into multilocular, the increased protein, and gene expression of UCP1 in iWAT19,20. Concomitantly, according to Syrový and colleagues, the activation of the proteins responsible for the Ucp1 gene transcription reduces the Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and Fatty acid synthase (FAS) enzyme activities16. Thus, a mechanism that increases UCP1 expression is capable of reducing the ACC protein involved in the hepatic lipogenesis process21. Furthermore, the expression of UCP1 and browning stimulus in sWAT promotes the decrease of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), insulin resistance, and regulates mitochondrial dysfunction22.

Therefore, knowing non-pharmacological strategies or molecules that stimulate UCP1 increasing is important to increase the basal energy expenditure of obese people23. Nonetheless, it is well known that aerobic physical exercise is an essential non-pharmacological stimulus responsible for generating genetic, physiological, and morphological adaptations, such as increased energy expenditure by enhancing the degradation of fatty acids and improving insulin signaling in several tissues24–26. However, the effects of strength exercise on the induction of factors related to the increase of UCP1 expression in the sWAT were not explored yet.

Moreover, it has been shown that the browning of sWAT is dependent on PPARγ/PGC-1α/PRDM complex protein activity leading to increased Ucp1 gene expression both in vivo and in vitro26. This phenomenon is stimulated by irisin derived from skeletal muscle of chronic animal training (swimming or running exercise) that can increase caloric expenditure and insulin sensitivity27,28. However, the effects of strength training on browning of sWAT, without body weight alterations, have not been described in the scientific literature. Therefore, firstly, the present study aims to assess whether 7 days of strength training can stimulate the browning process in subcutaneous adipose tissue. Secondly, to analyze whether there was an alteration in fat tissue profile and its synthesis and degradation in this fat tissue. Importantly, all observations were carried out without interference of body adipose changes.

Results

The effects of obesity and STST on physiological parameters

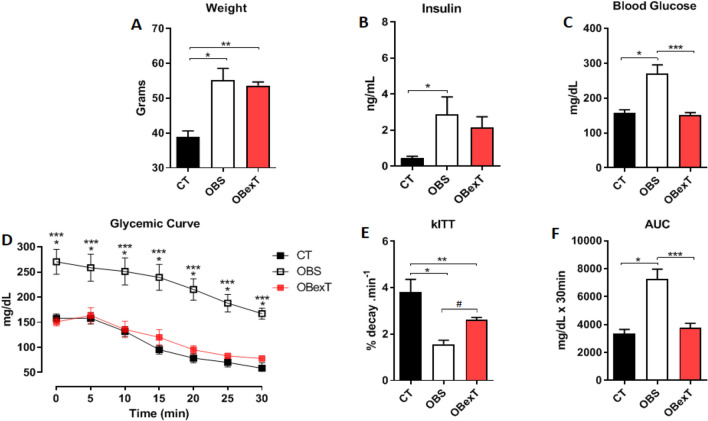

Initially, during 14 weeks, the animals were induced to obesity and insulin resistance conditions. After that, the animals of the obese trained group (OBexT) initiated the short-term strength training protocol. After 14 weeks on a high-fat diet, as expected, the obese group demonstrated a series of harmful characteristics resulting from obesity, such as increased body weight (Fig. 1A), fasting hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 1B), hyperglycemia (Fig. 1C), and insulin resistance (Fig. 1D–F). On the other hand, it was shown that this training protocol decreased fasting hyperglycemia (Fig. 1C). The insulin resistance condition was verified by using the glucose decay curve graph. It was possible to observe that the obese group decreased the rate of glucose uptake after insulin administration and that the STST ameliorated this condition (Fig. 1D–F). As expected, there was no difference in body weight between both obese groups at the end of the study.

Figure 1.

Effects of obesity and strength training on (A) Body weight, (B) Fasting insulin (8 h), (C) Fasting blood glucose (8 h), (D) Glycemic curve, (E) kITT and (F) AUC. The signal of statistical difference are represented as follows *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT, #p = 0.054 (n = 4 CT group; n = 5 OBS group; n = 5 OBexT group). Anova one-way statistical analysis was used, (Glycemic curve used Anova two-way) followed by Tukey’s post-test.

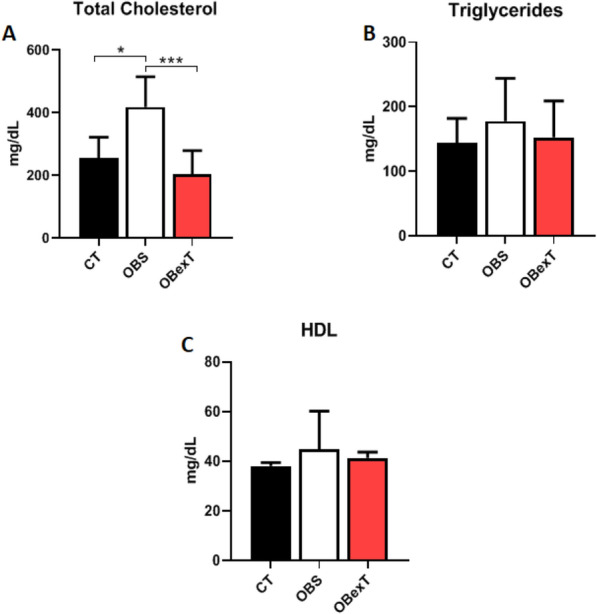

Furthermore, it was analyzed the serum lipid profile. Obese animals increased total cholesterol (Fig. 2A) levels when compared to the control group and the exercise protocol decreased these parameters. Moreover, no difference was found in serum triglycerides (Fig. 2B) and HDL (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of obesity and strength training on (A) Total Cholesterol, (B) Triglycerides, (C) High-Density Lipoproteins (HDL). The signal of statistical difference are represented as follows *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 5 CT group; n = 6 OBS group; n = 6 OBexT group). One-way Anova statistical analysis was used, followed by Bonferroni post-test.

The effects of obesity and STST on the sWAT fatty acids profile

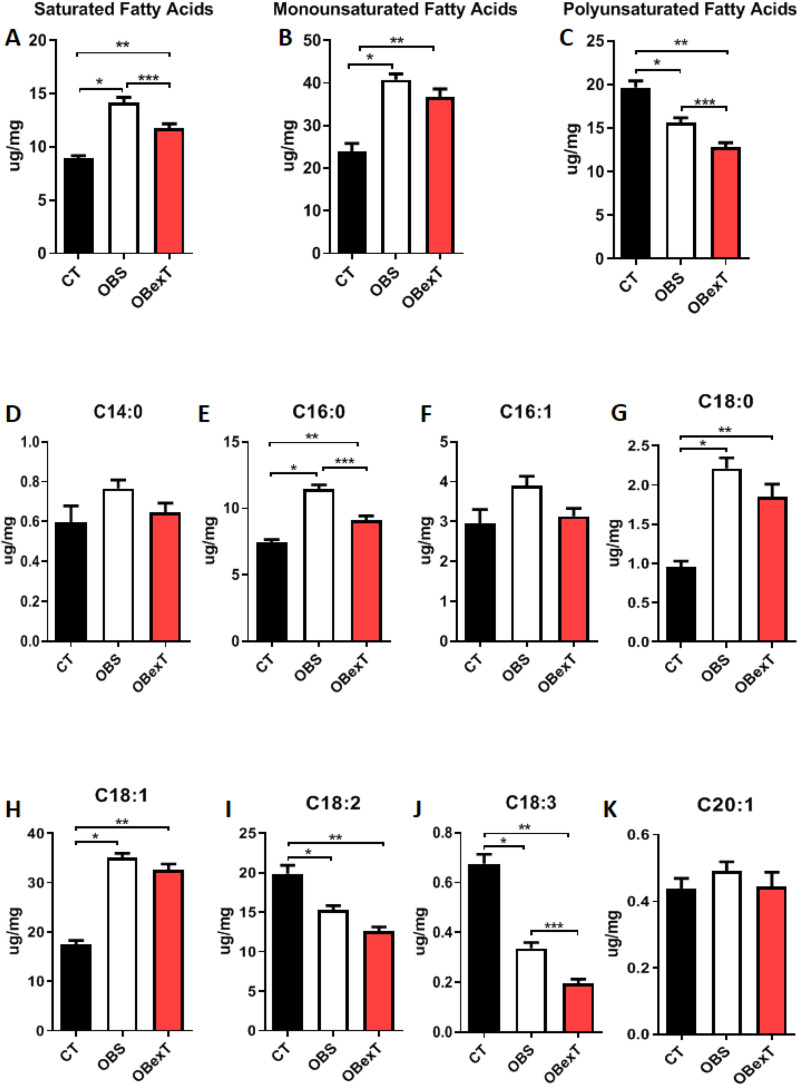

To assess a more accurate fatty acid profile in the sWAT, it was carried out the gas-chromatography technique coupled to mass-spectrometer to understand the modulation of the lipid profile of sWAT induced by obesity and short-term strength training. It was observed that obesity increased the amount of total saturated and monounsaturated fatty acid, while STST significantly decreased the saturated fatty acids parameters. On the other hand, the total polyunsaturated fatty acids were reduced by obesity and even more by the short-term strength training. When each fatty acid component was stratified, it was possible to observe that obesity increased palmitic (C16:0) and stearic (C18:0) fatty acids, while STST significantly decreased palmitic fatty acids. As expected, due to the high-fat diet, obese animals increased oleic fatty acid (C18:1), and it was not changed by the 7 days of strength training. The omega 6 and omega 3, such as linoleic (C18:2) and alpha-linolenic (C18:3) fatty acids, respectively, were reduced significantly by obesity and even more reduced by the short-term strength training. Other fatty acids, such as mirystic (C14:0), palmitoleic (C16:1), and eicosanoic (C20:1), were not changed by obese and exercise protocol (Fig. 3A–K).

Figure 3.

Subcutaneous adipose tissue fatty acids profile. (A) Total saturated fatty acids, (B) Total monounsaturated fatty acids, (C) Total polyunsaturated fatty acids, (D) Myristic fatty acids (C14:0), (E) Palmitic fatty acids (C16:0), (F) Palmitoleic fatty acids (C16:1), (G) Stearic fatty acids (C18:0), (H) Oleic fatty acids (C18:1), (I) Linoleic fatty acids (C18:2), (J) α-Linolenic fatty acids (C18:3) and (K) Eicosanoic fatty acids (C20:1). The signal of statistical difference are represented as follows indicated, *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 5 CT group; n = 6 OBS group; n = 6 OBexT group). One-way Anova statistical analysis was used, followed by Bonferroni post-test.

The effects of obesity and STST on the lipolysis pathway of sWAT

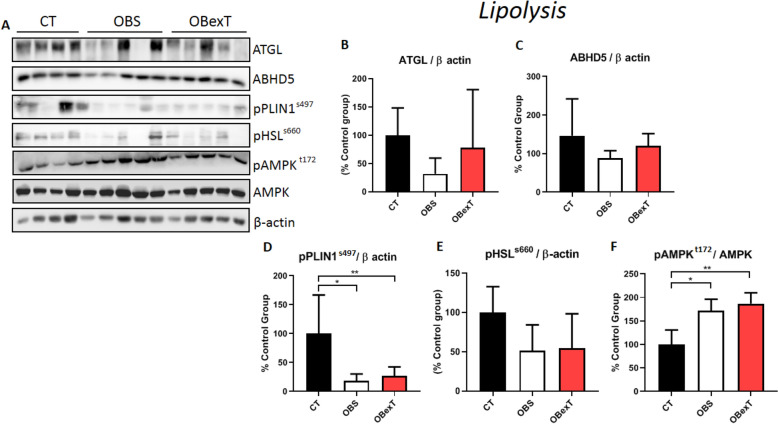

After the experimental period, the subcutaneous adipose tissue was removed to analyze the lipolysis pathways (Fig. 4A). Regarding lipolytic activities, it was possible to observe that both obesity and exercise groups did not alter the ATGL (Fig. 4B) and ABHD5 levels (Fig. 4C). However, when the phosphorylated Perilipin1 (pPLIN1ser497) was evaluated, it was shown that obesity reduced pPLIN1ser497 levels and that the seven sessions of exercise were not effective in reversing this parameter (Fig. 4D). Also, when analyzing the pHSLs660 protein it was not possible to observe a change in expression levels in both the obese and the exercised group (Fig. 4E). Moreover, when the pAMPKt172 was analyzed, it was shown that obesity increased its levels and that the STST was not effective in reversing this parameter (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Total protein extract obtained from the subcutaneous adipose tissue was used for Western Blotting experiments. Uncut images can be viewed in the supplementary material. The membranes were cut at the specific height of the target protein. (A) The protein content of (B) ATGL, (C) ABHD5, (D) pPLIN1ser497, (E) pHSLs660 and (F) pAMPKt172. The signal of statistical difference are represented as follows, *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 4 CT group; n = 5 OBS group; n = 5 OBexT group). One-way Anova statistical analysis was used, followed by Tukey's post-test.

The effects of obesity and STST on the lipogenesis pathway of sWAT

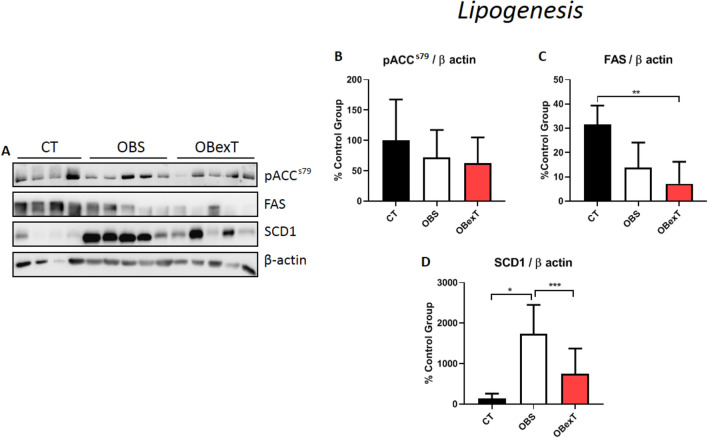

In Fig. 5, it was observed the influence of obesity and strength training on the proteins responsible for lipogenesis in sWAT (Fig. 5A). It was possible to verify that all groups did not show any difference in pACCs79 (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, obese trained animals decreased FAS levels when compared to the control group (Fig. 5C). However, when the levels of SCD1 were analyzed, it was observed that the sedentary obese group increased its levels when compared to lean control. Also, it was shown that after seven strength exercise sessions, the levels of SCD1 reached the control level, showing efficient effects of STST in reducing its levels (Fig. D).

Figure 5.

Total protein extract obtained from the sWAT was used for Western Blotting experiments. Uncut images can be viewed in the supplementary material. The membranes were cut at the specific height of the target protein. (A) The protein content of (B) pACCser79, (C) FAS, and (D) SCD1. The signal of statistical difference are represented as follows, *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 4 CT group; n = 5 OBS group; n = 5 OBexT group). One-way Anova statistical analysis was used, followed by Tukey's post-test.

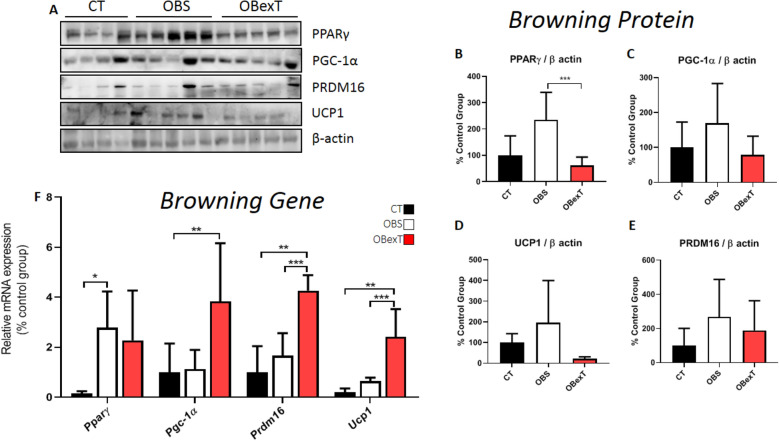

The effects of obesity and STST on browning of sWAT

In addition, it was evaluated the genes and proteins responsible for the browning of sWAT (Fig. 6A). Firstly, it was observed the PPARγ metabolism. It was possible to verify that the sedentary obese group showed a significant increase in this gene compared to the control. However, after short-term strength training, it was not possible to identify any difference in gene levels compared to the obese sedentary group (Fig. 6F). When the total PPARγ was analyzed, it was observed that the obese group increased its levels when compared to the obese trained group, demonstrating the effect of 7 days of training reduced the expression levels (Fig. 6B). Secondly, it was observed the PGC-1α metabolism. It was possible to verify that the gene expression of Pgc-1α was increased in the obese animals after the STST only when compared to the control group (Fig. 6F). However, it was not possible to identify any difference between all groups in their total protein levels (Fig. 6C). Thirdly, it was possible to observe that the trained animals increased the Prdm16 gene when compared to the control and obese groups (Fig. 6F). Subsequently, analyzing PRDM16 protein, no difference was found between all groups (Fig. 6D). Ultimately, the sedentary obese group showed no difference in Ucp1 gene and protein content compared to the control group. However, when the trained animals were observed, this protocol increased the Ucp1 gene compared to the control and obese groups (Fig. 6F). However, no differences were found in UCP1 protein levels for all groups (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6.

Total protein extract obtained from the subcutaneous adipose tissue was used for Western Blotting experiments. Uncut images can be viewed in the supplementary material. The membranes were cut at the specific height of the target protein. (A) The protein content of (B) PPARγ, (C) PGC-1α, (D) PRDM16, and (E) UCP1. The bars were relativized by the CT group (100%). In browning pathway, the signal of statistical difference are represented as follows *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 4 CT group; n = 5 OBS group; n = 5 OBexT group). In (F), the effect of strength training protocols on the induction of mRNA expression of genes involved in browning subcutaneous adipose tissue. Representative analysis in control, obese sedentary, and obese training swiss animals. Gene expression analysis of Pparγ, Pgc-1α, Prdm16, and Ucp1. In browning gene, the signal of statistical difference are represented as follows *p < 0.05 CT versus OBS, **p < 0.05 CT versus OBexT and ***p < 0.05 OBS versus OBexT (n = 7 CT group; n = 4 OBS group; n = 4 OBexT group). One-way Anova statistical analysis was used, followed by Tukey's post-test.

Discussion

The present study firstly aimed to assess whether seven strength training sessions promote sWAT browning. If so, secondly, to observe if this thermogenic adaptation can change lipid profile, increase lipolysis, and reduce the lipogenesis activity pathway in this tissue. At the end of this study, it was possible to observe that 7 days of strength training was able to change the fat tissue profile and moderately decrease the lipogenesis pathway. These findings were associated with the slightly beginning of the browning process in exercised obese animals.

It was identified that 14 weeks of obesity induction was able to increase fat mass, develop insulin resistance, and increase fasting glycemia and insulinemia. Corroborating our findings, Nakandakari and colleagues showed that 4 weeks of HFD in mice induces insulin resistance, body weight gain, and increased fasting glucose29. Moreover, it was possible to observe that obese exercised animals reduced fasting blood glucose, the area under the glycemic curve, and total cholesterol. In a study conducted by Pereira et al. fifteen sessions of strength exercise were able to reduce fasting glucose, hepatic triglyceride, and lipogenesis pathway in the liver of the obese mice30. For a chronic period, Marson and colleagues demonstrated that chronic aerobic, resistance, or combined training is associated with reduced fasting insulin in overweight or obese children, as mentioned in the present study31.

Subsequently, it was analyzed the effects of the high-fat diet on altering the lipid profile of fatty acids of subcutaneous adipose tissue. It sought to understand the composition of fatty acids in sWAT and the potential effect of strength training on altering this lipid profile.

The increment in the total saturated and monounsaturated fatty acid was expected in the sWAT of the groups treated with a high-fat diet, once the main source of lipids in the diet was from pork lard. We followed the American Institute of Nutrition32, in planning the modified high-fat diet, in accordance with Cintra et al.33. This diet contains ~ 21% of palmitic fatty acid and ~ 40% of oleic fatty acid in its composition. However, when compared to the content of these fatty acids in the commercial food for rodents, palmitic fatty acid reaches only 13 and ~ 27% of oleic fatty acid33. Then, these fatty acids are incorporated into adipose tissue depots, proportionally to founded in the diet. Interestingly, in the group performing the physical exercise protocol, the saturated fatty acids profile was changed in the subcutaneous adipose tissue, but not the monounsaturated fat profile, including its representants, palmitoleic and oleic fatty acids. We believe that palmitic fatty acid was driven to the β-oxidation process. This affirmative is corroborated by the partial reduction in the FAS and pACC protein contents but strongly correlated to a decrease in the SCD1 protein. With the absence of the SCD1 protein, the desaturation and elongation processes are compromised. It is certified once more due to the non-changes in the palmitoleic content (the first product after SCD1 action in palmitic fatty acid) or oleic fatty acid content.

The balance between synthesis and oxidation of fatty acids is a dynamic process, and during the exercise practicing, it is poorly understood. Besides, it could variates significantly in accordance with the experimental model adopted or tissue analyzed. For example, Rodrigues et al. (2017) evaluated the effects of voluntary physical exercise and aerobic training for 8 weeks in the composition of the fatty acid profile, in lean rats. They demonstrated that both the voluntary exercise protocol and aerobic training were not effective in reducing the levels of saturated fatty acids (C16:0 and C18:0) even reducing the visceral adiposity. However, both protocols were able to decrease the amount of unsaturated fatty acid (C16:1) in the epididymal adipose tissue30. It is known that there are significant differences among rat models (i.e. Fischer, Wistar, Sprague–Dawley) related to lipid metabolism or ability to retain or metabolize/mobilize fatty acids, under or not to HF-diet conditions34. Here, Swiss mice were chosen due to being a recognized model to accumulate fat mass and advance to obesity and its comorbidities, mimicking humans35. In parallel to our findings, Sutherland and colleagues, analyzing trained men to four months of high volume aerobic training (marathon), observed that the training load was able to reduce the levels of fatty acids palmitic (C16:0) and oleic (C18:1) in the subcutaneous adipose tissue when compared to sedentary individuals32. A reasonable explanation about fatty acids mobilization after exercise protocols could be related to the fatty acid desaturases (FADS1/2) or elongases (ELOV5/6) enzymes. While Rodrigues et al. (2017)31 observed the increased FADS1 and ELOV5 activity in adipose tissue after exercise training followed by reduced inflammatory markers (TNFα, IL6, and MCP1), Petridou et al., (2005) noticed a different activity of these enzymes in a tissue-specific manner. After exercise training, elongases were significantly higher and desaturases lower in adipose tissues (epididymal and subcutaneous) and muscle, while no differences were found in the liver36. The ability of exercise to induce modulation of FADS gene expression needs to be more explored as a very innovative field. Here, the exercise decreased the content of alpha-linolenic fatty acid (C18:3) an omega-3 species. In general, omega-3 fatty acids have been showing a protective effect in several conditions due to their anti-inflammatory properties37. However, as shown by Rodrigues et al., if the exercise increases FADS and ELOV enzymes, then it is possible that alpha-linolenic has a reduced content because it has been elonged and desaturated to another omega-3 species such as EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid [C20:5]) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid [C22:6]). The role of individual fatty acids species modulation is an interesting field that needs more investigation. From a general perspective, we found a reduction of total saturated fatty acids induced by exercise. It could be understood as a desirable profile, such as noticed by Choi and colleagues, which found that the reduction of saturated fatty acids in the sWAT increased the insulin sensitivity in the tissue1. The lipolysis of sWAT can be controlled by AMPK. When phosphorylated, AMPK activates two lipases proteins, the hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL)38. Knowing this, Thirupathi et al. compared the effects of strength and aerobic training on the pAMPK in white adipose tissue. They showed that both exercise protocols were successful in increasing the activity of AMPK in trained animals when compared to the sedentary group24. Corroborating these findings, Higa and colleagues evaluated the effects of chronic aerobic exercise on the pAMPK levels in the visceral adipose tissue of obese mice. They showed that the exercise protocol was efficient in increasing the phosphorylation of AMPK39. On the other hand, Kurauti et al. observed that acute aerobic exercise was not effective in improving the AMPK phosphorylation in the subcutaneous white adipose tissue of obese animals40. In the present study, obese animals increased pAMPK levels in the subcutaneous adipose tissue, and the short-term training protocol was not sufficient to change this parameter. In our study, such changes may be observed if the training period was longer, as shown by the literature. Another limiting factor for not observing changes in pAMPK after exercise was the time of tissue collection after the exercise session. As demonstrated by Halling, immediately after the exercise session, the pAMPK is elevated in adipose tissue. However, 2 h after, its phosphorylation already reaches baseline values41.

After AMPK activation, lipolysis is induced by HSL phosphorylation42. In this regard, Wei and colleagues investigate the effects of dose-dependent induction of Isoproterenol (ISOP), ApoA-I, and HDL in 3T3-L1 adipocyte cells, it was observed that the combined incubation of ISOP + ApoA-I, or ISOP + HDL, was able to increase the expression of pHSL in adipocyte cells43. However, Lehnig et al. induced mice to 3 weeks of voluntary aerobic exercise and evaluated the effects of exercise on pHSL modulation in mesenteric adipose, after the period of physical exercise the authors did not observe an increase in the expression of pHSL in the mesenteric adipose tissue44. In contrast, Geng and colleagues induced Klbf/f and Klbadi mice, to aerobic training to evaluate the expression of pHSL in the epididymal adipose, at the end of 4 weeks it was possible to observe a significant increase in the expression of pHSL in eWAT of young mice45. However, in the present study, it was not possible to observe changes in the expression of pHSL in response to obesity and after an STST protocol.

Wohlers and colleagues evaluated the effects of acute aerobic exercise on the phosphorylation Perilipin1 (PLIN1) in the visceral adipose tissue of obese mice. It was observed that the exercised animals did not increase the phosphorylation of PLIN146. On the other hand, Ko et al. showed that after chronic aerobic exercise, the activation of PLIN1, HSL, and ATGL was increased47. Corroborating the findings of Ko et al. Americo and colleagues observed that 8 weeks of aerobic exercise was able to significantly reduce the diameter of adipocytes through the modulation of proteins PLIN1 and pHSL in obese animals48. In this sense, these findings suggest that the PLIN1 phosphorylation in the subcutaneous adipose tissue seems to be exercise time-dependent47. Thus, in the present study, it was observed that obese animals decreased the phosphorylation of PLIN1. Moreover, the short-term protocol was not able to revert this condition in sWAT. In this sense, it seems that the 7 days of STST may not be enough to increase the PLIN phosphorylation in subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Regulation of ATGL is known to be mediated by perilipin, which works by releasing ABHD5 protein for a physical binding with ATGL49. Therefore, Stephenson et al. evaluated the effects of short-term aerobic training on ATGL expression in epididymal adipose tissue of the old rats, after 6 weeks of physical effort it was possible to observe the increase in the ATGL in the epididymal adipose tissue of the runner’s rats50. In contrast, Nielsen and colleagues investigated the effects of short-term exercise on ATGL expression in sWAT in healthy men and concluded that moderate aerobic exercise was not able to promote the alteration of ATGL expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue51. However, Mendhan et al. observed an increase in ATGL gene expression in subcutaneous adipose tissue after 12 weeks of combined training in young adult women52. Interestingly, in the present study, it was not possible to observe changes in ATGL levels in response to obesity and after a strength training protocol.

Studies have demonstrated the influence of exercise on ABHD5 protein in subcutaneous adipose tissue. The ABHD5, when associated with ATGL, results in more significant fatty acid degradation in adipose tissue53,54. Stephenson et al. showed that 6 weeks of strength exercise was not enough to change the ABHD5 levels in visceral adipose tissue of obese animals. Moreover, Yao and colleagues showed that 12 weeks of aerobic training was not sufficient to alter the Cgi-58 gene transcription (ABHD5) in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of overweight humans55. Corroborating these results, it was not possible to observe changes in ABHD5 levels in response to obesity and after an STST protocol.

Regarding the lipogenesis pathway, Pereira and colleagues evaluated the effects of short-term strength training (15 days of exercise) on ACC and FAS in the liver tissue of obese mice. They demonstrated that exercised obese animals were able to reduce the levels of fat accumulation and inflammation in the liver, due to the reduction of ACC and FAS activity when compared with the sedentary obese group30. Moreover, Chen et al. evaluated the effect of chronic moderate aerobic training on pACC levels in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese mice and observed that the exercise protocol was not effective in increasing the levels of pACC56. On the other hand, Arnt et al. evaluated patients with metabolic syndrome and submitted them to 16 weeks of exercise (high-intensity training "HIIT" vs. moderate exercise). After that, the white adipose tissue was evaluated, and the HIIT group presented a greater effect in decreasing post-training FAS levels when compared to the moderate training protocol group57. In the present study, seven sessions of strength training were not enough to observe a difference for the pACC and FAS proteins in comparison with the sedentary obese group. Based on other studies, it is believed that the time of intervention was not enough to activate these enzymes in the sWAT of obese trained animals58,59.

Lee and colleagues demonstrated that the high activity of the SCD1 enzyme in 3T3-L1 cells (adipose cells) is responsible for increasing the fatty acid synthesis process60. Pereira et al. showed that 15 days of strength exercise decreased the SCD1 levels in the liver of obese mice30. In parallel, Stotzer et al. evaluated the effects of chronic aerobic exercise on subcutaneous and mesenteric adipose tissue of obese rats. They observed that exercised animals decreased Scd1 gene levels in mesenteric adipose tissue, but with no difference in the subcutaneous adipose tissue61. In the present study, it was demonstrated that obese animals increased SCD1 levels in sWAT and that only seven sessions of strength training were sufficient to reverse this parameter.

The browning process of white adipose occurs through the modulation of the PPARγ/PGC-1α/PRDM16 pathway that stimulates the synthesis of UCP162. Reynolds et al. evaluated the effects of chronic aerobic exercise on the expression of Pparγ mRNA in epididymal adipose tissue of obese animals. The author demonstrated that the exercise protocol was not efficient in increasing the transcription of the Pparγ gene when compared with sedentary obese animals51. On the other hand, Petridou and colleagues showed that 8 weeks of voluntary running increased the expression of PPARγ in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of lean rats. In the present study, it was possible to observe that the sedentary obese group increased the levels of the Pparγ gene compared to the control group, but that the STST protocol was not effective in changing its levels in relation to the obese sedentary. However, when the total protein content of PPARγ was evaluated, obese groups increased their levels, and short-term strength training was responsible for decreasing the protein expression of PPARγ in the sWAT.

Stephenson and collaborators demonstrated that 6 weeks of aerobic exercise was not efficient in increasing the protein content of PGC-1α in sWAT of ovariectomized rats when compared to sedentary50. Norheim et al.13 analyzing healthy and overweight men submitted to 12 weeks of combined training (strength + endurance training), found no difference in the expression of the Pgc-1α gene in the subcutaneous adipose tissue. However, in the present study, it was possible to observe that short-term strength training was able to induce an increase in Pgc-1α gene transcription compared to the control group. However, it was not observed changes in the protein expression for PGC-1α for all groups.

The PRDM16 is the protein responsible for regulating the transcription of UCP164. Lee et al.65 demonstrated that the PRDM16 collaborates with the browning of WAT in adipocyte cell culture (3T3-L1). Stanford and colleagues demonstrated that 11 days of aerobic running was able to increase the gene levels of Prdm16 in the white adipose tissue of obese mice23. Still, Khalafi et al. evaluated the effects of 12 weeks of HIIT in obese male rats on PRDM16 expression. They demonstrated that the HIIT exercise was efficient in increasing the protein content of PRDM16 in subcutaneous adipose tissue66. In the present study, it was shown that STST was able to increase gene levels of Prdm16 when compared to sedentary obese mice. However, seven strength training sessions were not able to increase the protein expression of PRM16. Probably, the time of intervention with training was not enough to find a difference in the protein content of PRM16 between the obese groups.

Finally, UCP1 is transcribed by the PPARγ/PGC-1α/PRMD16 complex62. It is a transmembrane protein located between the inner membrane and the mitochondrial matrix, responsible for modulating the proton gradient by removing H+ ions from the intramembranous space to the matrix and generating energy in the form of heat67. Schaalan and colleagues showed that 6 weeks of swimming training increased the expression of the Ucp1 gene in the inguinal adipose tissue of obese rats68. On the other hand, after submitted obese mice to HIIT, Davis et al. did not observe any UCP1 modulation in the epididymal and retroperitoneal adipose tissue69. However, in the sWAT, Diaz and colleagues showed that 12 weeks of aerobic training increased Ucp1 gene expression in the subcutaneous adipose tissue of overweight and obese humans (women and men)70. It was demonstrated that strength exercise was able to increase the Ucp1 gene levels compared to the sedentary obese group. Interestingly, we did not observe any difference between the groups analyzing the UCP1 total protein content in sWAT. Our findings do not present a relationship between gene transcription and its protein expression. Thus, it is believed that the time of the strength training was not effective in promoting the necessary gene mRNA translation. Furthermore, the effects of strength training are still not well described in the literature as influencing changes in the sWAT genotype.

Therefore, we can conclude that the seven sessions of strength exercise were able to collaborate with the glucose homeostasis in obese mice. Also, this protocol decreased the levels of saturated, polyunsaturated, palmitic fatty acids and α-Linolenic fatty acids in sWAT. The 7 days strength exercise protocol did not change the lipolysis and slightly reduced the lipogenic pathways. Finally, our study demonstrated that the STST increased browning processes-related genes such as PGC-1α, PRDM16, and UCP1 in the sWAT. Interestingly, all these physiological and biomolecular mechanisms have been observed independently of changes in body weight. Thus, it is concluded that 7 days of strength training can be an effective strategy to initiate molecular changes and the browning process in sWAT.

Methods

Experimental animals

In the present study, it was used 8-week-old swiss mice from the UNICAMP Central Animals Facility (CEMIB). Animal experiments were carried out under Brazilian legislation on the scientific use of animals (Law No. 11,794, October 8, 2008) and were accepted by the Animal Ethics Committee (CEUA) of Biological Sciences, State University of Campinas, UNICAMP-Campinas-SP, No. 4773-1. In addition, our study followed the norms proposed by the ARRIVE guidelines. The animals were individually maintained in polyethylene cages in an enriched environment (PVC tubes were sawed into the medium yielding a 10 × 10 cm base and 5 cm high shelter) under controlled cycle conditions (12/12 h) with free access to water and conventional food, the light was switched on from 06:00 am to 06:00 pm, the temperature was controlled at 22 ± 2 °C, the relative humidity was 45–55%, and the noises were below of 85 decibels. Initially, the animals were divided into two groups, the chow diet (CT) and the high-fat diet (HFD). The animals from HFD were fed a high-fat diet (HFD, 60% of the calorie derived from lipids33) for 14 weeks, that were subdivided into two groups: obese sedentary (OBS) and obese strength training (OBexT).

Seven days of training adaptation

Before starting the training protocol, the animals were adapted to exercise and its apparatus. The procedures were performed for 5 consecutive days. Before the first attempt to climb with the empty conic tube used to carry the load, the animal was kept inside the chamber at the top of the ladder for 60 s. In the first attempt of climbing, the animal was positioned on the stairs 15 cm away from the entrance of the chamber. For the second attempt, the animal was placed 25 cm away from the chamber. By the third attempt, the animal was placed at the base of the ladder, 70 cm away from the chamber. When the animal reached the chamber, an 60 s resting period was given. Attempts from the bottom of the ladder continued until the animal successfully completed three attempts without any stimulus.

Maximal voluntary carrying capacity determination—MVCC

To control exercise intensity, the animals performed the test to determine the maximum voluntary carrying capacity (MVCC), proposed for rats25,71, and standardized for mice30. It consisted of an incremental test aiming to identify the maximum individual load with which the animal can perform a series of climbs of 70 cm. After the adaptation protocol, the animals rested for 1 day before starting the test. During the trial, the animals left the base of the ladder, and the attempt was considered successful when they reached the minimum distance proposed of 70 cm.

The initial series of the exercise were performed with 75% of the animal’s body weight overload. If the animal reached the desired height, increments of 5 g were added to the tube within each new attempt to climb until the animal could not complete the entire course, being considered exhaustion. In each successful attempt, the animal was removed from the ladder and placed in an individual cage resting for 5 min until the next attempt. The maximum load of the last successful attempt was considered the MVCC and was used to prescribe the individual loads during the experiment.

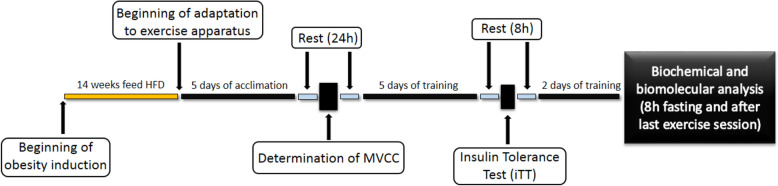

Exercise protocol

Twenty-four h after the MVCC determination, the strength training protocol was initiated. The exercise sessions consisted of 20 climbing series, with an overload of 70% of the MVCC and with a rest interval of 60–90 s between sets. After completing a series, the animal was removed from the ladder and placed in an individual cage during rest time. The animals were exercised for 5 consecutive days. Then, 8 h after their last exercise session, they performed the insulin tolerance test and more 8 h of rest. After that, they performed more 2 days of exercise. Lastly, 8 h after their last exercise session, they were euthanized for tissue sample harvest and biomolecular analyses (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Experimental design. Schematic representation of the duration of the experiment.

Intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test (ITT)

After a fasting period of 8 h and after the 5th physical exercise session, the animals were submitted to ITT to estimate glucose uptake capacity. Before starting the test, baseline blood glucose was assessed. Then the insulin (1U/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.), and blood samples were collected at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min from the tail to determine blood glucose. Glucose levels were determined using a glucometer (Accu-Chek®; Roche Diagnostics, Jaguaré-SP, Brazil). Results were evaluated by determining areas under capillary glucose curves (AUC) by the trapezoidal method72 using Microsoft Excel®(Washington, USA).

Adipose tissue extraction

After the ITT, all animals were submitted to two additional strength exercise session, and 8 h after the 7th exercise session, they were anesthetized via i.p. injection of chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg, ketamine, Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, MI) and xylazine (30 mg/kg, Rompun, Leverkusen, Germany). After this, the corneal reflexes were verified and assured. After that, the blood was collected, and the subcutaneous adipose tissue was rapidly removed and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. During the experiments, the total number of animals analyzed varies according to the physical and material capacity of each equipment/ technique. The tissue was homogenized in extraction buffer (1% Triton-X 100, 100 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 100 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium vanadate, 2 mM PMSF and 0.1 mg of aprotinin/mL) at 4 °C with a TissueLyser II (QUIAGEN®, Hilden, Germany) operated at maximum speed for 240 s.

Western blotting

The lysates were centrifuged (Eppendorf 5804R) at 12.851 g at 4 °C for 45 min to remove insoluble material, and the supernatant was used for the assay. The protein content was determined according to the bicinchoninic acid method73. The samples were applied to a polyacrylamide gel for separation by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were cut at the specific height of the target protein. The membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk at room temperature for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies against the protein of interest ([Cell® (Danvers, MA, USA) UCP1#14,670, PPARγ#2435, SCD1#2794 s, β-actin#3700, pACCs79#3661, pHSLs660#4126, ATGL#2138], [Vala Sciences® (San Diego, CA, USA) pPLIN1s497#4855], [Abcam® (Cambridge, LON, UK) PRDM16#ab106410], [Santa Cruz® (Dallas, TX, USA) PGC-1α#sc13067, pAMPKt172#sc33524, AMPK#sc25792, FAS#sc48357], [Proteintech® (Rosemont, IL, USA) ABHD5#12,201–1-ap]). After that, a specific secondary antibody was used, according to the primary antibody. The specific bands were labeled by chemiluminescence, and visualization was performed by photo documentation system in G:box (Syngene, Bangalore, IND). The bands were quantified using the software UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (Orem, UT, USA).

Spectrophotometry

Blood serum was obtained through the collection with a collecting tube after the animal was decapitated, and the levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose, and HDL were determined according to the manufacturer's instructions using a commercial kit (Laborlab, Guarulhos, São Paulo, Brasil) and using (Biotek Gen5™, Winooski, VT, USA) LDL determination by manufacturer's instructions method and Friedewald formula74.

Quantitative real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). An amount of 2 µg total RNA was used as a template for cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript® III First Chain Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real-time PCR reactions were performed using 150 ng cDNA, 300 nM primers (Exxtend®, Paulínia-SP, Brazil), and SYBR® Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystem, Warrington, UK). Thermocycling parameters were: 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. The relative expression of mRNAs was determined after normalization with Ywhaz using the ΔΔCt method. Each primer set was designed to recognize unique regions of gene sequences, according to Table 1.

Table 1.

This table represents the browning pathway gene sequence used for qPCR analysis.

| Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|

| Pparg | 5′GTACTGTCGGTTTCAGAAGTGCC3′ | 5′ATCTCCGCCAACAGCTTCTCCT3′ |

| Pgc-1(alpha) | 5′GAATCAAGCCACTACAGACACCG3′ | 5′CATCCCTCTTGAGCCTTTCGTG3′ |

| Prdm16 | 5′ATCCACAGCACGGTGAAGCCAT3′ | 5′ACATCTGCCCACAGTCCTTGCA3′ |

| Ucp1 | 5′GCTTTGCCTCACTCAGGATTGG3′ | 5′CCAATGAACACTGCCACACCTC3′ |

| Ywhaz | 5′GAACTCCCCAGAGAAAGCCT3′ | 5′CCGATGTCCACAATGTCAAGT3′ |

Adipose tissue lipid profile analyses

Lipids from subcutaneous adipose tissue were extracted following the proposed by Folch et al.75. About 50 mg of tissue was added to 1 mL of chloroform: methanol (2:1 v/v). The samples were homogenized in the TissueLyser (QIAGEN® Hilden, Germany), centrifuged at 13.000 × g for 2 min, and then the supernatant was collected. The esterification of the lipid fraction was performed according to the method adopted by Shirai et al.76. The fatty acids methyl esters were analyzed with a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (Shimadzu® GCMS-QP2010 Ultra, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan) and a fused-silica capillary Stabilwax column (Restek Corporation, Bellefonte, PA, USA) with dimensions of 30 m × 0.25 mm internal diameter coated with a 0.25-μm thick layer of polyethylene glycol. High-grade pure helium (He) was used as the carrier gas with a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Using an automatic injector (AOC-20i), sample volumes of 1 μL were injected at 250 °C using a 20: 1 split ratio. The injector temperature was maintained at 250 °C, while the oven heating schedule started at 80 °C, with heating speed programmed in a ramp from 5 °C/min to 175 °C, followed by a heating rate of 3 °C /min until 230 °C, where the temperature was maintained for 20 min77. Mass conditions were as follows: ionization voltage, 70 eV; ion source temperature, 200 °C; full scan mode in the 35–500 mass range with 0.2 s/scan velocity.

Statistical analysis

Before all the analysis, the Gaussian distribution of the data was assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The Anova one-way with Bonferroni multiple comparison tests was performed for total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, and adipose tissue profile. Anova one-way with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed for body weight, fasting insulin, fasting blood glucose, RT qPCR, and Western Blot data analysis. Anova two-way with Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed to compare ipITT glycemic curve time points. All results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) and the statistical significance level adopted was p < 0.05 for all analyses. The statistical analysis and the construction of the graphs were performed using the software GraphPad Prism7® (San Diego, CA, USA).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research support agency National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPQ), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), and São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (FAPESP) (2015/07199-2). The authors would like to thank Fernando Moreira Simabuco for all the assistance during the experiments.

Author contributions

L.P.M designed the manuscript; D.G.M. was responsible for the physiological tests, animal training, data analysis, physiological, protein and gene results, writing and written work development and had the overall responsibilities of the experiments in this study; C.P.A physiological results, physiological tests and animal training; K.C.C.R. project organization, physiological tests, and animal training; R.M.P. project organization, physiological tests, and animal training; T.D.P.C. physiological tests and animal training; R.S.C. physiological tests and animal training; C.O.R. contributed by performing the analysis and statistical treatment of chromatography data. A.S.R.S, D.E.C, E.R.R., J.R.P, and L.P.M contributed to the discussion, review, and supported the financial costs.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-10688-w.

References

- 1.Chooi YC, Ding C, Magkos F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith KB, Smith MS. Obesity statistics. Prim. Care: Clin. Office Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geserick M, et al. Acceleration of BMI in early childhood and risk of sustained obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerji MA, Chaiken RL. Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Princ. Diabetes Mellit. 2010 doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09841-8-34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montonen J, et al. Food consumption and the incidence of type II diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baskin AS, et al. Regulation of human adipose tissue activation, gallbladder size, and bile acid metabolism by A b3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Diabetes. 2018 doi: 10.2337/db18-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao L, et al. Cold-inducible SIRT6 regulates thermogenesis of brown and BEIGE Fat. Cell Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blondin DP, et al. Human brown adipocyte thermogenesis is driven by β2-AR stimulation. Cell Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fromme T, Klingenspor M. Uncoupling protein 1 expression and high-fat diets. Am. J. Physiol.: Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00411.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S, et al. Sildenafil induces browning of subcutaneous white adipose tissue in overweight adults. Metabolism. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pérez-Martí A, et al. A low-protein diet induces body weight loss and browning of subcutaneous white adipose tissue through enhanced expression of hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norheim F, et al. The effects of acute and chronic exercise on PGC-1α, irisin and browning of subcutaneous adipose tissue in humans. FEBS J. 2014;281:739–749. doi: 10.1111/febs.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nedergaard J, Cannon B. The browning of white adipose tissue: Some burning issues. Cell Metab. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartelt A, Heeren J. Adipose Tissue Browning and Metabolic Health. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Syrový I, et al. Decreased fatty acid synthesis due to mitochondrial uncoupling in adipose tissue. FASEB J. 2002;14:1793–1800. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0965com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thyagarajan B, Foster MT. Beiging of white adipose tissue as a therapeutic strategy for weight loss in humans. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Invest. 2017 doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mottillo EP, et al. Coupling of lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis in brown, beige, and white adipose tissues during chronic β3-adrenergic receptor activation. J. Lipid Res. 2014 doi: 10.1194/jlr.M050005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guilherme A, et al. Neuronal modulation of brown adipose activity through perturbation of white adipocyte lipogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilherme A, et al. Adipocyte lipid synthesis coupled to neuronal control of thermogenic programming. Mol. Metab. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mottillo EP, et al. FGF21 does not require adipocyte AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) or the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) to mediate improvements in whole-body glucose homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mi Y, et al. EGCG stimulates the recruitment of brite adipocytes, suppresses adipogenesis and counteracts TNF-α-triggered insulin resistance in adipocytes. Food Funct. 2018 doi: 10.1039/c8fo00167g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanford KI, Middelbeek RJW, Goodyear LJ. Exercise effects on white adipose tissue: Beiging and metabolic adaptations. Diabetes. 2015;64:2361–2368. doi: 10.2337/db15-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thirupathi A, et al. Strength training and aerobic exercise alter mitochondrial parameters in brown adipose tissue and equally reduce body adiposity in aged rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019;75:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s13105-019-00663-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornberger TA, Farrar RP. Physiological hypertrophy of the FHL muscle following 8 weeks of progressive resistance exercise in the rat. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1139/h04-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boström P, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. 2012;481:463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, et al. Irisin exerts dual effects on browning and adipogenesis of human white adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol.: Endocrinol. Metab. 2016 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00094.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, et al. Exercise-induced irisin in bone and systemic irisin administration reveal new regulatory mechanisms of bone metabolism. Bone Res. 2017 doi: 10.1038/boneres.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakandakari SCBR, et al. Short-term high-fat diet modulates several inflammatory, ER stress, and apoptosis markers in the hippocampus of young mice. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pereira RM, et al. Short-term strength training reduces gluconeogenesis and NAFLD in obese mice. J. Endocrinol. 2019 doi: 10.1530/JOE-18-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marson EC, Delevatti RS, Prado AKG, Netto N, Kruel LFM. Effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined exercise training on insulin resistance markers in overweight or obese children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reeves PG, Nielsen FH, Fahey GC. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: Final report of the American institute of nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993 doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cintra DE, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids revert diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation in obesity. PLoS One. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muñoz VR, et al. The effects of aging on rho-kinase and insulin signaling in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue of rats. J. Gerontol.: Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020;75:432–436. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Souza GFP, et al. Defective regulation of POMC precedes hypothalamic inflammation in diet-induced obesity. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petridou A, et al. Effect of exercise training on the fatty acid composition of lipid classes in rat liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;94:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1294-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira V, et al. Diets containing α-linolenic (ω3) or oleic (ω9) fatty acids rescues obese mice from insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2015;156:4033–4046. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarc E, Petan T. Lipid droplets and the management of cellular stress. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2019;92(3):435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higa TS, Spinola AV, Fonseca-Alaniz MH, Evangelista FS. Remodeling of white adipose tissue metabolism by physical training prevents insulin resistance. Life Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurauti MA, et al. Acute exercise restores insulin clearance in diet-induced obese mice. J. Endocrinol. 2016 doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halling JF, Ringholm S, Nielsen MM, Overby P, Pilegaard H. PGC-1α promotes exercise-induced autophagy in mouse skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rep. 2016 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang NH, Mukherjee S, Yun JW. Trans-cinnamic acid stimulates white fat browning and activates brown adipocytes. Nutrients. 2019;11:577. doi: 10.3390/nu11030577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei H, et al. Modulation of adipose tissue lipolysis and body weight by high-density lipoproteins in mice. Nutr. Diabetes. 2014;4:e108–e118. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2014.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lehnig AC, et al. Exercise training induces depot-specific adaptations to white and brown adipose tissue. iScience. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Geng L, et al. Exercise alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction via enhancing FGF21 sensitivity in article exercise alleviates obesity-induced metabolic dysfunction via enhancing FGF21 sensitivity in adipose tissues. Cell Rep. 2019;26:2738–2752.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wohlers LM, Jackson KC, Spangenburg EE. Lipolytic signaling in response to acute exercise is altered in female mice following ovariectomy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcb.23302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ko K, et al. Exercise training improves intramuscular triglyceride lipolysis sensitivity in high-fat diet induced obese mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0730-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Américo ALV, et al. Aerobic exercise training prevents obesity and insulin resistance independent of the renin angiotensin system modulation in the subcutaneous white adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2019 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granneman JG, Moore HPH, Krishnamoorthy R, Rathod M. Perilipin controls lipolysis by regulating the interactions of AB-hydrolase containing 5 (Abhd5) and adipose triglyceride lipase (Atgl) J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34538–34544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephenson EJ, et al. Exercise training enhances white adipose tissue metabolism in rats selectively bred for low- or high-endurance running capacity. Am. J. Physiol.: Endocrinol. Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00544.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nielsen TS, et al. Fasting, but not exercise, increases adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) protein and reduces G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 (G0S2) protein and mRNA content in human adipose tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:1293–1297. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mendham AE, et al. Exercise training results in depot-specific adaptations to adipose tissue mitochondrial function. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60286-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanders MA, et al. Endogenous and synthetic ABHD5 ligands regulate ABHD5-perilipin interactions and lipolysis in fat and muscle. Cell Metab. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel S, Yang W, Kozusko K, Saudek V, Savage DB. Perilipins 2 and 3 lack a carboxy-terminal domain present in perilipin 1 involved in sequestering ABHD5 and suppressing basal lipolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318791111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao-Borengasser A, et al. Adipose triglyceride lipase expression in human adipose tissue and muscle. Role in insulin resistance and response to training and pioglitazone. Metabolism. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen N, et al. Effects of treadmill running and rutin on lipolytic signaling pathways and TRPV4 protein expression in the adipose tissue of diet-induced obese mice. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13105-015-0437-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tjønna AE, et al. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2008;118:346–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.la de Fuente FP, et al. Exercise regulates lipid droplet dynamics in normal and fatty liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta: Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.158519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montenegro ML, et al. Effect of physical exercise on endometriosis experimentally induced in rats. Reprod. Sci. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1933719118799205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee HJ, Le B, Lee DR, Choi BK, Yang SH. Cissus quadrangularis extract (CQR-300) inhibits lipid accumulation by downregulating adipogenesis and lipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells. Toxicol. Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stotzer US, et al. Resistance training suppresses intra-abdominal fatty acid synthesis in ovariectomized rats. Int. J. Sports Med. 2015 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song NJ, Chang SH, Li DY, Villanueva CJ, Park KW. Induction of thermogenic adipocytes: Molecular targets and thermogenic small molecules. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017 doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynolds TH, et al. Effects of a high fat diet and voluntary wheel running exercise on cidea and cidec expression in liver and adipose tissue of mice. PLoS One. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang S, Pan MH, Hung WL, Tung YC, Ho CT. From white to beige adipocytes: Therapeutic potential of dietary molecules against obesity and their molecular mechanisms. Food Funct. 2019 doi: 10.1039/c8fo02154f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee HE, et al. Anti-obesity potential of Glycyrrhiza uralensis and licochalcone A through induction of adipocyte browning. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khalafi M, et al. The Impact of moderate-intensity continuous or high-intensity interval training on adipogenesis and browning of subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese male rats. Nutrients. 2020 doi: 10.3390/nu12040925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chi J, et al. Three-dimensional adipose tissue imaging reveals regional variation in beige fat biogenesis and PRDM16-dependent sympathetic neurite density. Cell Metab. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schaalan MF, Ramadan BK, Abd Elwahab AH. Synergistic effect of carnosine on browning of adipose tissue in exercised obese rats; a focus on circulating irisin levels. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018 doi: 10.1002/jcp.26370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Davis RAH, et al. High-intensity interval training and calorie restriction promote remodeling of glucose and lipid metabolism in diet-induced obesity. Am. J. Physiol.: Endocrinol. Metab. 2017 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00445.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otero-Díaz B, et al. Exercise induces white adipose tissue browning across the weight spectrum in humans. Front. Physiol. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Speretta GF, et al. Resistance training prevents the cardiovascular changes caused by high-fat diet. Life Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matthews JNS, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. Br. Med. J. 1990 doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6725.680-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walker JM. The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay for protein quantitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1994;32:5–8. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-268-X:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972 doi: 10.1093/clinchem/18.6.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957 doi: 10.3989/scimar.2005.69n187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shirai N, Suzuki H, Wada S. Direct methylation from mouse plasma and from liver and brain homogenates. Anal. Biochem. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cintra DEC, et al. Lipid profile of rats fed high-fat diets based on flaxseed, peanut, trout, or chicken skin. Nutrition. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.