Summary

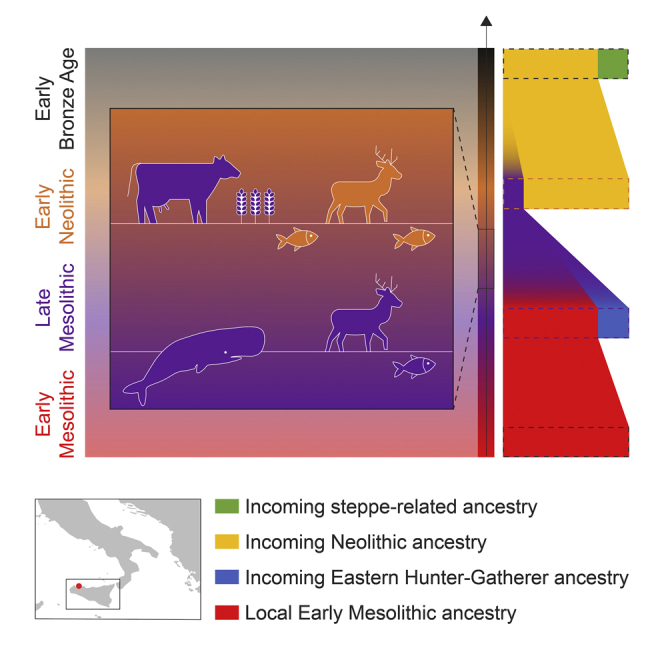

Sicily is a key region for understanding the agricultural transition in the Mediterranean because of its central position. Here, we present genomic and stable isotopic data for 19 prehistoric Sicilians covering the Mesolithic to Bronze Age periods (10,700–4,100 yBP). We find that Early Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (HGs) from Sicily are a highly drifted lineage of the Early Holocene western European HGs, whereas Late Mesolithic HGs carry ∼20% ancestry related to northern and (south) eastern European HGs, indicating substantial gene flow. Early Neolithic farmers are genetically most similar to farmers from the Balkans and Greece, with only ∼7% of ancestry from local Mesolithic HGs. The genetic discontinuities during the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic match the changes in material culture and diet. Three outlying individuals dated to ∼8,000 yBP; however, suggest that hunter-gatherers interacted with incoming farmers at Grotta dell’Uzzo, resulting in a mixed economy and diet for a brief interlude at the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Evolutionary biology, Paleobiology, Paleogenetics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Genetic transition between Early Mesolithic and Late Mesolithic hunter-gatherers

-

•

A near-complete genetic turnover during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition

-

•

Exchange of subsistence practices between hunter-gatherers and early farmers

Biological sciences; Evolutionary biology; Paleobiology; Paleogenetics

Introduction

One of the most impactful changes in human history was the transition in subsistence practices from comparably mobile hunting and gathering to sedentary farming. The primary zone of Neolithization in western Eurasia spanned the Fertile Crescent and eastern Anatolia, whereas the role of central and western Anatolia, as secondary recomposition areas or as a distinct primary core, is still being debated (Bar-Yosef, 2002; Binder, 2002; Özdoğan, 2008). By ∼8,700–8,500 yBP, several groups of early farmers with or without knowledge of ceramics had established communities around the Aegean (Douka et al., 2017; Horejs et al., 2015; Perlès, 2001). Some of these developed the later Starčevo-Körös-Criș, Karanovo, and Sesklo complexes ∼8,100–8,000 yBP through the Balkans (Karamitrou-Mentessidi et al., 2015; Lichardus-Itten, 2009; Perlès, 2001). Farming practices spread across Europe and Mediterranean northwestern Africa along archaeologically distinct routes (Price, 2000; Whittle, 1996). Early farmers associated with the Neolithic Starčevo-Körös-Criș-complex and the successive Linear Pottery culture (Linearbandkeramik, LBK) followed a continental route out of the Balkan Peninsula along the Danube river into central Europe and from there further north and west (so-called Danubian/Continental Route). In parallel, agricultural practices and pottery spread westwards out of Greece and the Balkans along the Mediterranean coastline (so-called Mediterranean Route). Since ∼8,100–8,000 yBP, the Neolithization process in the Mediterranean region was shaped by the succession of various local, Neolithic horizons (Guilaine, 2007; Leppard, 2021). Interactions between the various farming and local hunter-gatherer groups as well as cultural drift resulted in a complex Neolithic mosaic involving the Impressa and Cardial horizons in the eastern and western Mediterranean, respectively (Binder et al., 2017; Guilaine and Manen, 2007; Manen et al., 2019; Zilhão, 2014).

Ancient DNA (aDNA) studies have contributed substantially to the understanding of the Neolithization of Europe. The general picture that has emerged is that large-scale expansions of early farmers facilitated, and even originated, the agricultural transition in Europe (Haak et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016; Mathieson et al., 2015; Olalde et al., 2015; Omrak et al., 2016; Skoglund et al., 2012, 2014). Nearly all of the farmer ancestry in European early farmer (EEF) groups, including those associated with the Mediterranean Route, represents a subset of the genomic diversity found among early farmers from northwestern Anatolia (Barcın) and the northern Aegean (Revenia) (Hofmanová et al., 2016; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016, 2017; Mathieson et al., 2015). However, early farmers from Diros in Peloponnese Greece might have harbored an ancestral component that placed them outside of the genetic diversity found in those from Barcın (Mathieson et al., 2018).

Moreover, aDNA studies have also indicated that the underlying Neolithization demographic processes likely differed among regions within Europe (González-Fortes et al., 2017; Lipson et al., 2017b; Mathieson et al., 2018; Rivollat et al., 2020; Skoglund et al., 2014). Early farming in central, western and northern Europe along the Continental Route contained characteristic elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic, including domesticated animals and plants. The early farmers in these regions carried only a very minor genomic contribution from local European HGs (Haak et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Mathieson et al., 2015; Skoglund et al., 2012). In contrast, there is archaeological evidence for a more gradual appearance of agricultural elements along the Mediterranean Route (Isern et al., 2017; Mulazzani et al., 2016; Sánchez et al., 2012). Notably, the contribution of Mesolithic forager ancestry to EEF varied regionally and was higher in some communities in the Balkans, southern France, and Iberia but not in Italy (Antonio et al., 2019; Fregel et al., 2018; Lipson et al., 2017b; Mathieson et al., 2018; Olalde et al., 2019; Rivollat et al., 2020; Valdiosera et al., 2018; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). However, it is important to note that the majority of EEF genetic data comes from groups that spread along the Continental Route. For the Mediterranean Route, the main uncertainties revolve around the expansion of the Impressa Ware culture in Italy. Recently, it was shown that some Early Neolithic farmers from peninsular Italy might retain an additional ancestral component related to early farmers from Iran (Ganj Dareh) and/or HGs from the Caucasus (CHG) (Antonio et al., 2019). This raises the possibility that they descended from a different group compared to the known western Mediterranean and central European farmers (Antonio et al., 2019; Mathieson et al., 2018).

The island of Sicily marks a central position in the Mediterranean and features some of the earliest evidence for farming starting as early as ∼8,000 cal BP (Binder et al., 2017; Mannino et al., 2015) (calibrated radiocarbon years before present) or even earlier (∼8,200 cal BP) (García-Puchol et al., 2017). However, to date, no ancient genomes are available for Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic individuals from Sicily. As such, the demographic processes underlying the initial emergence of farming practices as well as the origins of the early farmer groups along the European and North African Mediterranean coastlines remain unknown.

Grotta dell’Uzzo in northwestern Sicily is a unique site for understanding human prehistory in the Central Mediterranean. The cave stratigraphy at G. dell’Uzzo covers the late Upper Paleolithic, a continuous occupation during the Mesolithic, and up to the Middle Neolithic, with traces of later occupation (STAR Methods) (Mannino et al., 2015). This provides direct and unprecedented insights into the cultural, subsistence, and dietary changes that took place in the transition from hunting and gathering to farming (Mannino et al., 2007, 2015; Tagliacozzo, 1993). In addition, two Impressa Ware horizons associated with elements of Early Neolithic farming appeared rapidly in a time frame of ∼500 years. The first horizon of Impressa Wares appeared 8,000–7,700 cal BP followed by the Impressed Ware of the Stentinello group (Stentinello/Kronio) around 7,800–7,500 cal BP (Binder et al., 2017; Guilaine, 2018; Mannino et al., 2015; Natali and Forgia, 2018). The continuous stratigraphy across the different Mesolithic and Early Neolithic material horizons with a large set of radiocarbon (14C) dates is a unique feature in the context of Mediterranean Mesolithic-Neolithic sites and allows us to investigate 1) the genomic structure of the Mesolithic Sicilian foragers, and 2) the demographic processes underlying the transition from foraging to farming directly.

Results

To investigate the biological processes underlying the transition from foraging to agropastoralism in Sicily, we jointly analyzed ancient genome-wide data and stable isotopic data for dietary inferences for a chronological transect of 19 individuals from G. dell’Uzzo in northwestern Sicily. We obtained direct 14C dates on the skeletal elements that were used for genetic analysis and determined carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope values from the same bone collagen for dietary reconstruction (Tables S1, S2, Data S1.1). We extracted DNA from bone and teeth in dedicated clean room facilities, built DNA libraries, and enriched for ∼1240k single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the nuclear genome and independently for the complete mitogenome (Fu et al., 2015) using in-solution hybridization enrichment techniques (Fu et al., 2013a). All libraries were checked for endogenous human aDNA content, aDNA damage patterns, and nuclear and mitogenome contamination. We restricted our analyses to individuals with evidence of authentic human aDNA and removed ∼300k SNPs on CpG islands to minimize the effects of residual postmortem DNA deamination (Seguin-Orlando et al., 2015). The final dataset includes 868,755 intersecting autosomal SNPs for which our newly reported individuals cover 53,352–796,174 SNP positions with an average read depth per target SNP of 0.09–9.39X (Data S1.1). We compared our data to a global set of contemporary (Lazaridis et al., 2014; Mallick et al., 2016; Patterson et al., 2012) and ancient individuals from Europe, Asia, and Africa (Allentoft et al., 2015; Antonio et al., 2019; Brace et al., 2019; Broushaki et al., 2016; Brunel et al., 2020; Catalano et al., 2020; Damgaard et al., 2018; Feldman et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2020; Fregel et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2014, 2016; Gamba et al., 2014; Günther et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2015, 2017, 2015; Keller et al., 2012; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016, 2017; Lipson et al., 2017b; Llorente et al., 2015; Mallick et al., 2016; Marcus et al., 2020; Mathieson et al., 2018; Meyer et al., 2012; Mittnik et al., 2018; Olalde et al., 2015, 2018, 2019; Omrak et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2014; Rivollat et al., 2020; Saag et al., 2017; Sikora et al., 2017; Skoglund et al., 2014; Valdiosera et al., 2018; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). Here, we provide population genomic and dietary isotope analyses for 19 individuals that cover a time transect of over 6,000 years from the Early Mesolithic (EM; ∼10,700 cal BP) to the Early Bronze Age (EBA; ∼4,100 cal BP) (Data S1.1). An Epigravettian HG individual (OrienteC) from the Grotta d’Oriente on Favignana island in western Sicily (14,200–13,800 cal BP, 14C date on charcoal from the deposit) is co-analyzed with our data (Catalano et al., 2020; Mathieson et al., 2018).

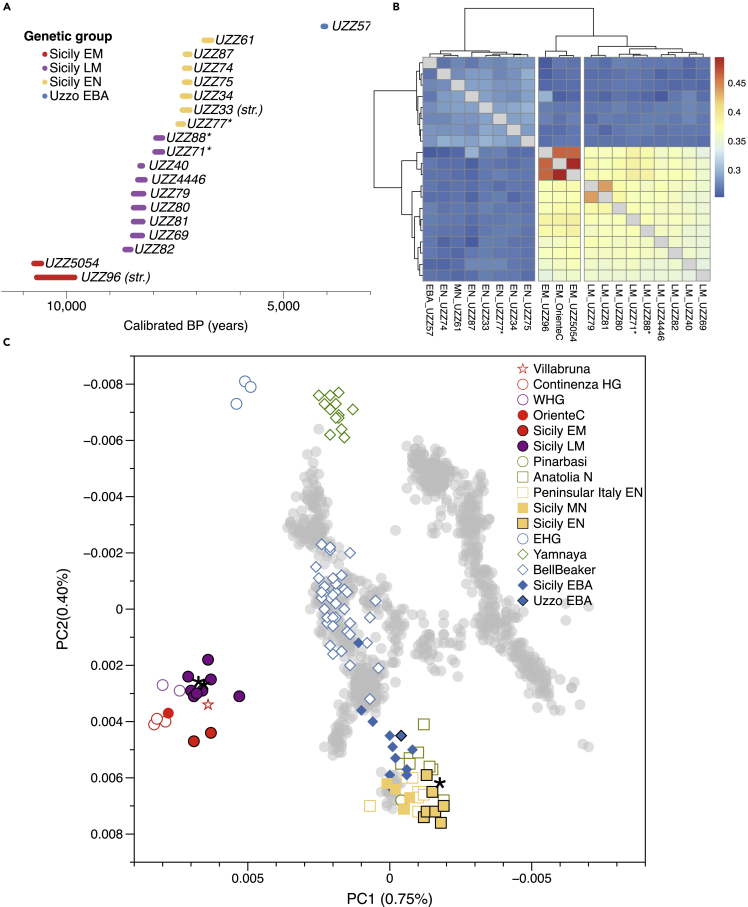

Genetically distinct groups of prehistoric Sicilians

The newly generated 14C dates confirm that the prehistoric Sicilians in our time transect can be attributed to five groups that correspond to different archaeological periods (Early Mesolithic, Castelnovian Late Mesolithic, Early Neolithic, Middle Neolithic, and Early Bronze Age) attested at G. dell’Uzzo (Figure 1A, STAR Methods). When analyzed in conjunction with genetic data from published ancient and present-day Europeans, the Uzzo individuals are clustered into four groups based on the principal component analysis (PCA, Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Chronology and genomic structure of prehistoric Sicilians

(A) Calibrated date ranges (2-sigma) of the prehistoric Sicilians determined from direct radiocarbon (14C) measurements, or stratigraphy (str.) in the case of UZZ96 and UZZ33, with correction for marine reservoir effect for some individuals (STAR Methods). The individuals are colored according to their assigned genetic group. Individuals UZZ71, -88 and -77 may be contemporaneous with the early Impressa Ware phase at the site (marked by ∗).

(B) Heat plot showing three genetic groups among the prehistoric Sicilians, including previously published OrienteC individual from Sicily. Genetic distances were measured with pairwise outgroup statistics of the form f3(Mbuti; Ind1, Ind2) (Data S1.2).

(C) PCA plot of 43 modern West Eurasian groups (gray crosses), on which the newly reported prehistoric Sicilians (colur-filled symbols with black outlines) together with relevant previously published individuals are projected: from Sicily (filled symbols with no outline), and from other regions (open symbols).

The two oldest groups fall within a cluster of western European Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (WHG) with a subtle distinction in their genetic ancestry as shown by both PCA positioning and pairwise outgroup-f3 statistics (Figure 1B). The first group contains the two oldest individuals (one directly dated to 10,750–10,580 cal BP, Figure 1A) from G. dell’Uzzo, who produced a lithic industry that was typologically and stylistically similar to the preceding Epigravettian tradition (STAR Methods (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2016)) and closely associated with the previously published Epigravettian OrienteC (14,200–13,800 cal BP) (Catalano et al., 2020; Mathieson et al., 2018). These three individuals all carried mitogenome lineages that fall within the U2′3′4′7′8′9 branch (Data S1.1), which was closely related to an Epigravettian-associated Sicilian from San Teodoro and also reported for an older Gravettian-associated Paglicci108 from the Italian peninsula (Modi et al., 2021; Posth et al., 2016). They also shared a large amount of genetic drift with each other, compared to other individuals in the WHG cluster (Data S5.3, Figure S3). We labeled this group as Sicily Early Mesolithic (Sicily EM, n = 3).

The second, chronologically younger HG group includes nine individuals dated to ∼8,650–7,790 cal BP. Seven of them correspond archaeologically to the Late Mesolithic and probably for part of the Castelnovian, a variety of the Late Mesolithic blade-and-trapeze horizon in southern France, Italy, and Dalmatia, as well as Sicily (Clark, 1958). In the western Mediterranean, the Castelnovian has strong chronological, stylistic, and technical connections with the Iberian Geometric Mesolithic and with the upper Capsian in the Maghreb (Binder et al., 2012; Marchand and Perrin, 2017), but the blade-and-trapeze horizon also extends eastwards into the Pontic Region and further into the Eurasian landmass (Biagi and Starnini, 2016; Gronenborn, 2017). The other two younger individuals (UZZ71 and UZZ88, dated to 7,960–7,790 cal BP) overlap with the supposed earliest emergence of Neolithic aspects at G. dell’Uzzo (Archaic Impressa, STAR Methods). These two individuals fall within the diversity of the foragers attributed to the LM Castelnovian in PC space (Figure 1C) and pairwise outgroup-f3 statistics (Figure 1B). Moreover, the mitogenome haplogroups carried by these individuals are all typical for European Late Mesolithic WHG (Bramanti et al., 2009; Posth et al., 2016), falling in haplogroups U4 and U5, different from the first group (Data S5.2). As a consequence, we grouped UZZ71 and UZZ88 with the Sicily LM HG individuals, and labeled this group as Sicily Late Mesolithic (Sicily LM, n = 9).

The third group contains individuals directly dated to ∼7,430–6,660 cal BP, overlapping chronologically with Early Neolithic to Middle Neolithic farmer horizons at G. dell’Uzzo, characterized by Impressed Wares (Sicily EN, n = 7). In PC space, these individuals group with early farmers from southeastern Europe and Anatolia, and not with the preceding Sicilian HGs (Figure 1C). All the farmer individuals with sufficient coverage on the mitogenome carried haplogroups characteristic for European early farmers: U8b1b1 (n = 2), N1a1a1 (n = 1), J1c5 (n = 1), K1a2 (n = 1) and H (n = 1) (Data S1.1) (Brandt et al., 2013). They showed a subtle distinction in PC space from the Middle Neolithic farmers from Fossato di Stretto Partanna, Sicily (Sicily MN, 6,940–6,660 cal BP), which are contemporaneous with the Middle Neolithic individual (UZZ61) from G. dell’Uzzo (Fernandes et al., 2020).

The fourth and youngest group includes one individual (UZZ57) dated to 4,150–3,970 cal BP and is attributed to the Early Bronze Age (Uzzo EBA). This individual is displaced from the Early Neolithic toward the direction of individuals associated with the Bell Beaker phenomenon and other Late Neolithic and BA groups that carry the so-called “steppe”-related ancestry. This ancestry was characteristic for the steppe-nomads from western Eurasia and spread across Europe during the Bronze Age (Haak et al., 2015). A similar shift was also found in published Early Bronze Age individuals from Sicily (Fernandes et al., 2020). This individual UZZ57 carried the Y-haplogroup R1b1a1b1a1a2, commonly found in Bronze Age Europe, and also previously reported in Sicilian Bronze Age individuals (Data S1.4, Data S5.2) (Fernandes et al., 2020).

Genomic and dietary transitions in Sicily during the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic

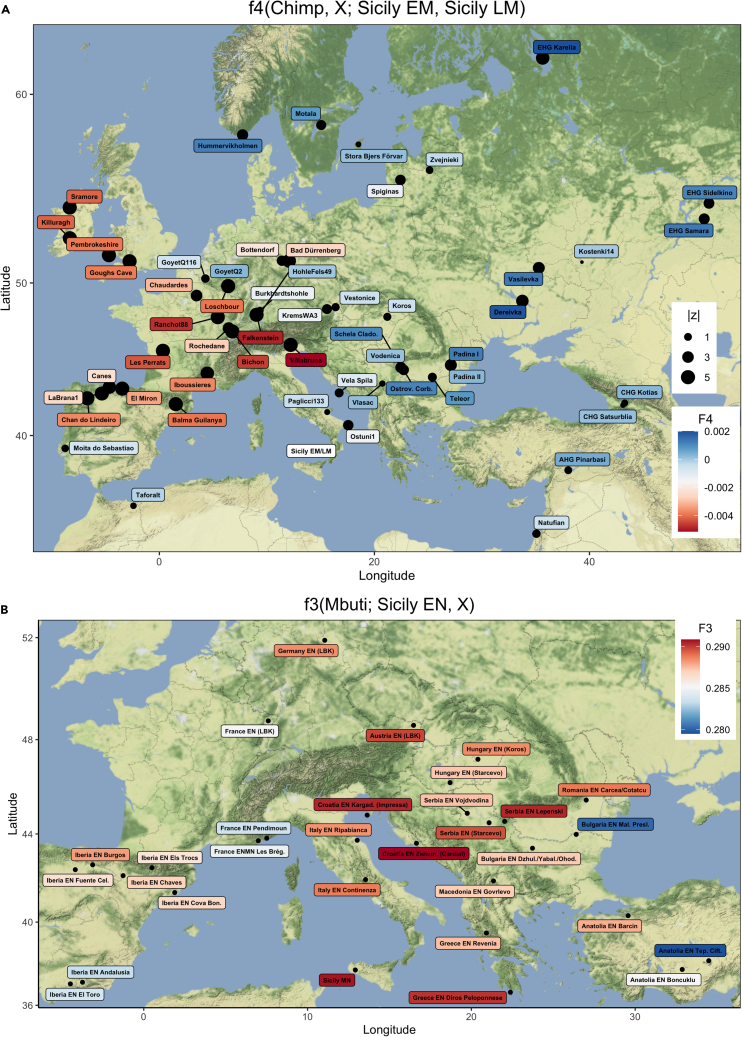

Our Mesolithic time transect of 11 individuals, spanning around 3,000 years, provides a unique opportunity to explore changes in genomic substructure over time. A more direct comparison of the ancestries in the Sicily EM and LM HGs with f4-cladality statistics of the form f4(Chimp, X; Sicily EM HG, Sicily LM HG) for various West Eurasian HGs (X) reveals a pattern that is linked to geography (Figure 2A, Data S2.2). Here, significantly negative f4-values show that Sicily EM HGs share more alleles with HGs from (south-)western Europe, including WHGs from the Villabruna cluster, as well as Iberian Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic HGs carrying Magdalenian-associated ancestry (Fu et al., 2016; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). In contrast, the Sicily LM HGs share significantly more alleles with Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic HGs from northern Europe, (south-)eastern Europe, and Russia (Data S2.2). This indicates a change in genetic affinities on Sicily during the Mesolithic.

Figure 2.

Genomic affinity of the prehistoric Sicilians

(A) Comparing the ancestry in Sicily EM and LM HGs to various West Eurasian HGs (X), as measured by f4(Chimp, X; Sicily EM HG, Sicily LM HG). Warmer colors indicate that X shares more genetic drift with Sicily EM HGs than with Sicily LM HGs, and cooler colors the opposite. Point sizes reflect |z|-scores.

(B) Early Neolithic Sicilian farmers show the highest genetic affinity to contemporaneous farmers from the Balkans (Croatia and Serbia) and Middle Neolithic Sicily, as measured by f3(Mbuti; Sicily EN, X). Warmer colors indicate higher levels of allele sharing. For standard errors, see Data S2.2 and S3.1.

The difference in affinity to West-Eurasian HGs between Sicily EM and LM HGs could be explained by residual, (Magdalenian-associated) GoyetQ2-like ancestry present in Sicily EM HGs or alternatively by the small proportion of Eastern Hunter-gatherer (EHG)-related ancestry in Sicily LM HGs or by both. As such, we characterized the Sicily EM and LM genetic ancestries more explicitly using qpWave- and qpAdm-based admixture models (Lazaridis et al., 2016). We found that the ancestry of Sicily EM HGs can be modeled as a clade with Continenza HGs from peninsular Italy with regards to the outgroup set used (Pwave = 0.191, see STAR Methods) to the exclusion of all other tested West-Eurasian HGs, including ∼14,000 yBP Villabruna from northern Italy (Pwave = 5.98E-05). Subsequent two-way qpAdm admixture models that tested for a mixture of various proxies for WHG ancestry and Magdalenian-related ancestry were rejected for the Sicily EM HG gene pool (Data S2.5). The admixture graphs based on qpGraph modeling also fitted the Sicily EM HGs as a sister branch of Villabruna, with potential contribution to Magdalenian-related ancestries (Figures S7–S9).

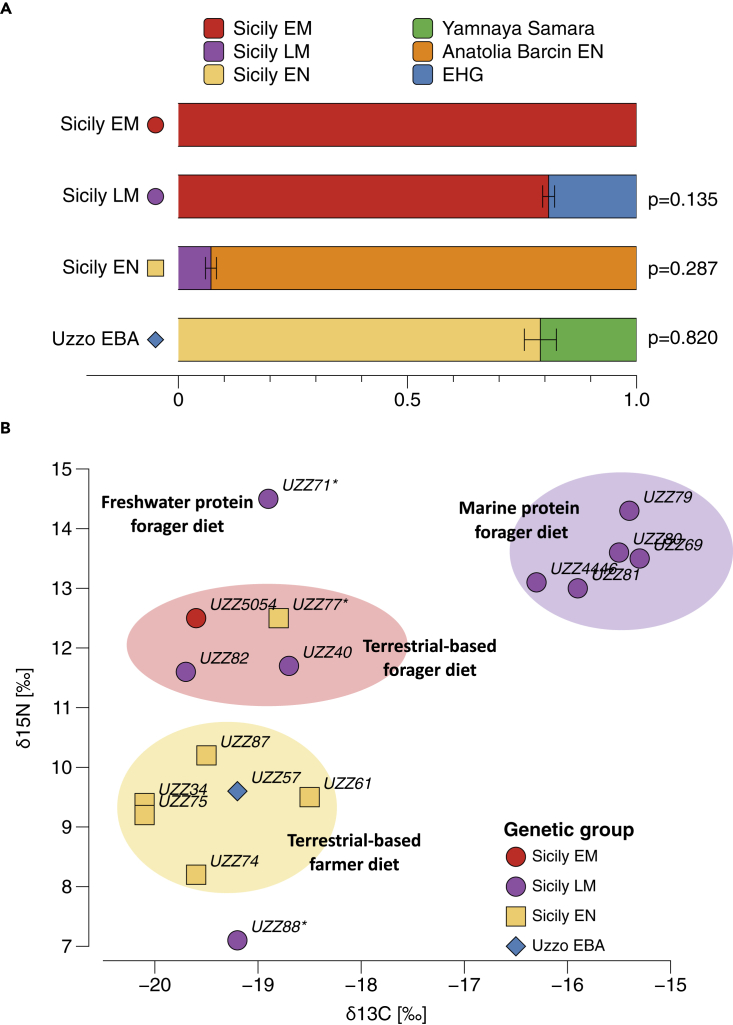

Subsequently, we investigated the degree of genetic continuity between the Sicily EM and LM HGs and explicitly tested whether the latter derive distinct ancestry from an EHG-related source with qpWave and qpAdm-based ancestry models. We found that neither the ancestry in Sicily EM HGs nor Italian HGs from Continenza or Villabruna can provide a full fit to the ancestry of the Sicily LM HGs (max. PWave-value: 1.90E-04, Data S2.5). Instead, a dual ancestry of 80.8 ± 1.3% Sicily EM HGs and 19.2 ± 1.3% EHG resulted in a supported model (PAdm = 0.135, Figure 3A, Data S2.5). Notably, only Sicily EM HGs can be used as a proxy for the WHG-related ancestry in Sicily LM HGs. All other models with West-Eurasian HGs, including Continenza and Villabruna HGs from peninsular Italy, were rejected at p < 0.05 (Data S2.5). This indicates that the WHG-related ancestry in Sicily LM HGs most likely derived from the preceding local Sicilian foragers. The admixture between Sicily EM HGs and EHGs was dated to 20 ± 5 generations ago, corresponding to ∼8,800 years ago, which coincides with the beginning of Late Mesolithic in G. dell’Uzzo (Data S5.3, Table S4).

Figure 3.

Genomic and dietary discontinuities at Grotta dell’Uzzo, Sicily, during the Mesolithic and Early Neolithic

(A) Genomic profiles determined from qpAdm-based ancestry models. The length of colored bars showed the estimated proportion of each ancestry, with error bars showing the standard errors of estimation, and p values showing the support for the model.

(B) Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios for diet reconstruction. For European ecosystems, carbon stable isotopes are mostly used to distinguish terrestrial from marine foods. Nitrogen isotopes ratios incrementally increase in organisms at every trophic level of the food chain, and can therefore give an indication of the amount and trophic level of the consumed protein (herbivorous, carnivorous, and omnivorous). Colored symbols indicate the individuals’ assigned genetic group. Individuals UZZ88, UZZ71, and UZZ77 have outlier diets (outlined) and are contemporaneous to the earliest Impressa Ware phase (marked with∗).

We further investigated the observed affinity of Sicily LM HGs to HGs in northern and (south-)eastern Europe as indicated by the f4-cladality statistics in more detail (Figure 2B). Congruent with the observed affinities, we found that in the two-way admixture model the EHG-related ancestry in Sicily LM HGs can be approximated by the ancestry found in HGs from Scandinavia (SHG), Latvia, Ukraine, and Romania Iron Gates (Data S2.5). This confirms a minor contribution of nonlocal ancestry alongside the persistent local ancestry in Sicily during the Mesolithic.

Of note, we found that the global nucleotide diversity (π) for the Sicily EM HGs is ∼25% lower compared to the subsequent Sicily LM HGs (95% confidence intervals 0.161–0.170 and 0.217–0.223, respectively, Figure S4). Furthermore, we detected an extremely large amount (>350 cM) of runs of homozygosity (ROH) segments in Sicily EM HGs, especially the shortest 4–8 cM segments that represent background relatedness (Ringbauer and Novembre, 2020). The amount of short ROH segments is much larger compared to all other European Upper Paleolithic or Mesolithic HGs, including the later Sicily LM HGs, and contemporaneous Continenza HGs and Villabruna from peninsular Italy (Figure S5). Taken together, these results suggest a small effective population size in the Sicily EM HGs that could result from a population bottleneck (Data S5.3) and an effective population size increase in the Late Mesolithic, potentially because of the influx of non-local ancestry.

The Sicilian early farmers (Sicily EN) fall closest to European Early Farmers (EEF) and not with the preceding local Sicilian HGs in PC space (Figure 1C). Using an outgroup-f3 statistic of the form f3(Mbuti; Sicily EN, and X), we explored which of the other contemporaneous ancient groups show the highest genetic affinity to Sicily EN (Figure 2B). Congruent with the PCA results, the Sicilian early farmers share most genetic drift with various EN farmers from the Balkans and Greece, as well as central Europe. In contrast, Sicily EN farmers have less genomic affinity with individuals from the western Mediterranean coast such as France, Iberia, and northwestern Africa (Figure 2B, Data S3.1), who carried a higher proportion of HG ancestry as a result of admixture with local HG groups (Lipson et al., 2017b; Olalde et al., 2019; Rivollat et al., 2020; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). This supports the finding of a major turnover of genetic ancestry during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in Sicily, similar to what has been reported for EN farmers from peninsular Italy (Antonio et al., 2019) and many other regions in Europe (Günther et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016; Lipson et al., 2017b; Mathieson et al., 2015; Olalde et al., 2015; Omrak et al., 2016; Skoglund et al., 2012, 2014).

To explore this further, we used f4-admixture statistics of the form f4(Chimp, Sicily LM HG; Anatolia EN Barcin, Sicily EN) to test whether the Sicily EN farmers retained an excess of shared alleles with the preceding Sicily LM HGs, when using Anatolia EN Barcin as a baseline for EEF ancestry. The statistic was significantly positive, suggesting excess local HG ancestry in Sicily EN farmers (z = 5.051, Data S3.2). Indeed, with qpAdm-based admixture models, we estimate that local Sicilian LM HGs contributed 7.5 ± 0.9% of the ancestry to the Sicilian EN farmer gene pool (Figure 3A, Data S3.3). Of note, the local HG admixture signal is significantly lower when compared to previously published Sicily MN farmers from Fossato di Stretto Partanna (Fernandes et al., 2020) (f4(Chimp, Sicily LM HG; Sicily EN, and Sicily MN): z = 5.381, Data S3.2), which carried an estimated 11.9 ± 0.9% local Sicily LM HG ancestry (Data S3.3). Overall, this suggests a subtle, yet detectable, contribution and potential resurgence of local HG ancestry in Sicilian farmers during the Neolithic. Importantly, the published Sicily MN farmers are contemporaneous with the youngest farmer individual UZZ61 (6,830–6,660 cal BP) in our Sicily EN group, which indicates that the resurgence may have taken place elsewhere in Sicily (e.g., at Fossato di Stretto Partanna) by the mid-seventh-millenium BP, but not yet in G. dell’Uzzo.

The Early Bronze Age individual UZZ57 shows a shift in PC space toward individuals that are associated with the Late Neolithic Bell Beaker phenomenon and EBA groups that carry steppe-related ancestry (Figure 1C), similar to what has been observed in other EBA individuals from Sicily (Fernandes et al., 2020). This is also confirmed by qpAdm, in which individual UZZ57 could be modeled as a two-way mixture between local Sicily EN ancestry and ‘steppe ancestry’ represented by Yamnaya Samara (Figure 3A). The steppe ancestry contribution in UZZ57 was estimated to 21.0 ± 3.5%, which falls within the range of other published Sicily EBA groups (Data S3.4).

Did Sicilian Late Mesolithic foragers adopt some aspects of early farming?

To shed further light on the processes underlying the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in Sicily, we jointly analyzed the stable isotope data for dietary inference (δ13C/δ15N) and the ancestry profile for each individual in our time transect (Data S5.1, Figure S2, Table S3). We find that individuals from different time periods carrying different genetic ancestries also consumed isotopically different diets (Figure 3B). The isotopic data show that the Early Mesolithic HGs from G. dell’Uzzo relied mainly on hunting terrestrial game with substantial contributions of plant foods but limited consumption of marine resources (Mannino et al., 2015). In contrast, the diet of the Sicily LM HGs carrying EHG ancestry was characterized by a significantly higher intake of marine-based protein. The isotopic values for the Sicilian EN farmers are congruent with them having a terrestrial-based farming diet. Overall, the isotopic and ancestry profiles per individual show that diets correspond broadly with the assigned genomic cluster and attested subsistence per archaeological time period.

However, two individuals (UZZ71, UZZ88) chronologically overlap with the period when the Impressa Ware made its appearance at the site (Mannino et al., 2015). The two oldest individuals (UZZ71 and UZZ88), genetic females dated to ∼7,960–7,790 cal BP, fall fully within the genomic diversity of the Late Mesolithic HGs associated with the Castelnovian sensu lato, despite postdating them by ∼200 years (Figure 1C, Data S5.1). Both these individuals show isotope values that are different from the preceding Late Mesolithic HGs as well as from the later Sicily EN farmers associated with Stentinello/Kronio pottery (Figure 3B, Data S5.1). The dietary profile of individual UZZ71 (δ13C = −18.9‰, δ15N = 14.5‰) indicates an intake of freshwater protein, similarly to what has been reported for Mesolithic HG from the Iron Gates on the Balkan Peninsula (Bonsall et al., 2015; Borić and Price, 2013). On the other hand, individual UZZ88 shows an isotopic composition (δ13C = −19.2‰, δ15N = 7.1‰) that suggests a terrestrial-based farming diet with very low levels of animal protein consumption (EN farmers analyzed from G. dell’Uzzo): mean δ13C = −19.4 ± 0.5‰, mean δ15N = 9.1 ± 1.2‰). The observed combination of HG ancestry profile and terrestrial farming diet for UZZ88 can be explained in two ways: agro-pastoralism had strongly influenced local subsistence practices and/or some foragers had become part of the incoming farming groups. Conversely, UZZ77, an individual whose genetic makeup is typical of the incoming farmers, has a dietary profile (δ13C = −18.8‰, δ15N = 12.5‰) more similar to that of the Mesolithic terrestrially-based foragers. The combined genetic and isotopic data for UZZ88 and UZZ77 point to some degree of interaction between local hunter-gatherers and incoming farmers, which is also compatible with the small proportion of HG ancestry present in Sicily after the introduction of farming, as also attested at the MN site of Fossato di Stretto Partanna (Fernandes et al., 2020).

Discussion

The Apennine Peninsula (today’s Italy) has long been viewed as one of the refugia during the LGM (Feliner, 2011; Schmitt, 2007), ∼25,000–18,000 years ago, from where Europe was repopulated (Fu et al., 2016; Posth et al., 2016). The earliest evidence for the presence of Homo sapiens in Sicily dates to ∼19,000–18,000 cal BP, following the time when a land bridge connected the island to peninsular Italy (Antonioli et al., 2016; Di Maida et al., 2019). Although there are many sites in peninsular Italy and Sicily with evidence of Late Upper Paleolithic occupation, forager populations seemed to have decreased during the Mesolithic (Biagi, 2003), congruent with the observation that EM HGs from G. dell’Uzzo produced a lithic industry derived from the Epigravettian tradition (STAR Methods) (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2016). The profoundly reduced population genomic diversity (Figure S4), large quantity of short ROH tracts in the Sicily EM HGs (Figure S5), together with a high level of shared genetic drift with Mesolithic foragers from Continenza (Figure S3, Data S2.1), hint at a population bottleneck that affected foragers in Sicily and potentially also central Italy.

Some Late Epigravettian sites in Sicily contain rock panels with engraved animal figures that are similar to those of the Franco-Cantabrian, including Magdalenian (Mussi, 2001). Here, we showed that compared to the ∼14,000 yBP Epigravettian-associated HG Villabruna in northern Italy, the Sicily EM HGs have a higher genetic affinity to Iberian HGs associated with the Magdalenian and Azilian, such as El Mirón and Balma Guilanyà (Data S2.2). Antonio et al. reported similar affinities for Mesolithic HGs from Continenza (Antonio et al., 2019). Compared to Villabruna, no extra Magdalenian-related ancestry has been found in Continenza or G. dell’Uzzo (Data S2.2) (Antonio et al., 2019), whereas Iberian HGs including El Mirón and Balma Guilanyà have been suggested to carry Epigravettian-related ancestry (Figure S6) (van de Loosdrecht, 2021; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). This suggests the Epigravettian-related ancestry in Iberian HGs was likely derived from southern/central Italy. Both archaeological and genomic results suggest a deep connection between the Epigravettian of southern Italy and the Magdalenian and Azilian in Iberia (van de Loosdrecht, 2021), which warrants further investigation.

Compared to Sicily EM HGs, Sicily LM HGs derived ∼18–21% of their ancestry from an EHG-related source, providing evidence for shifting ancestry during the Mesolithic (Figure 3A). After the LGM, foragers associated with Epigravettian assemblages expanded in both Italy and southeastern Europe (Djindjian, 2016; Maier, 2015). Similar to southern Italy, the Balkans were also a glacial refugium. Currently, there are no genomes available for Epigravettian foragers from the Balkans. However, the Mesolithic HGs from this region are among the oldest HGs carrying EHG-related ancestry in southeastern Europe (Figure S6C) and suggest the Balkans as a candidate region for the excess EHG ancestry found in LM Sicily HGs. From the start of the Early Holocene, ∼11,700 yBP onward, an EHG/Anatolia HG (AHG) mixture can be found among HGs from Scandinavia, the Baltic, Ukraine, and the Balkans (Figure S6) (van de Loosdrecht, 2021). This underlines previous reports for a long-standing interaction sphere of HGs with EHG and AHG-related ancestry from northern and eastern Europe toward the Near East and the Caucasus (Feldman et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2016; Mathieson et al., 2018). This population may well have expanded into Sicily in the course of the westward shift of the blade-and-trapeze horizon into central and southern Europe, which seems to have begun after the climatic anomaly around 9,300 yBP (Gronenborn, 2017; van de Loosdrecht, 2021).

In contrast, the ancient genome-wide data for the Sicily EN farmers point to a near-complete genetic turnover during the transition from foraging to farming. The preceding Late Mesolithic HGs have contributed at most ∼7% ancestry to the EN farmers from G. dell’Uzzo (Figure 3A). This indicates that the transition to agriculture involved population replacement of local foragers by early farmers to a large extent during the Early Neolithic, similar to previous results for early farmers from Ripabianca and Continenza in peninsular Italy and other regions in Europe (Antonio et al., 2019; Bramanti et al., 2009; Günther et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016, 2017). However, the distinct diets and the intermediate 14C dates of a few individuals from the period around the beginning of the Neolithic provide tentative evidence that HGs and farmers initially exchanged their subsistence practices in Sicily, as was hypothesized by Tusa (Tusa, 1985, 1996). We observed individuals with HG ancestry and a farming/fishing diet, while one individual with farmer ancestry had a terrestrially-based forager diet (Figure 3B). In the absence of strontium isotope analyses on each of these individuals, we cannot exclude that one or more of them were not locals, although this seems unlikely on genetic grounds in the case of UZZ71 and UZZ88, who have the same genetic makeup as the LM hunter-gatherers from G. dell’Uzzo. This may lead to the question of whether a mixed forager/fishing/farming economy may have become established at G. dell’Uzzo for up to a couple of centuries after the introduction of agropastoralism. This possibility is compatible with the zooarchaeological evidence from the site, which indicates that fishing may have been more commonly practiced in the Early Neolithic than in the Mesolithic (STAR Methods).

Although rather rare, cases of HGs adopting elements of farming have been reported before in the Balkans, such as at the Iron Gates in Serbia and Romania, Malak Preslavets in Bulgaria, and very recently for the French Mediterranean coast (Bonsall et al., 2015; Forenbaher and Miracle, 2006; Gronenborn, 2017; Lipson et al., 2017b; Mathieson et al., 2018; Perlès, 2001; Rivollat et al., 2020).In addition, the few available ancestry profiles for Early Neolithic farmers in the Maghreb showed a strong population genomic continuity with the ∼15,000 yBP Iberomaurusian foragers from this region (Fregel et al., 2018; van de Loosdrecht et al., 2018). Taken together, these cases provide joint evidence of generally heightened interaction between HGs with early farmers in central and western Mediterranean regions, such as north-western Sicily (Isern et al., 2017; Mulazzani et al., 2016; Rivollat et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2012; van de Loosdrecht, 2021). Future research could explore the possibility that in Mediterranean coastal regions, acculturation of local foragers played a more significant role in the process of Neolithisation compared to regions along the Continental Route (van de Loosdrecht, 2021).

The expansion routes into the central and western Mediterranean form an integral part of archaeological discourse on the Mediterranean Neolithic transition. Congruent with previous results for EN farmer groups in Iberia, we show that the Sicilian EN farmers also shared genetic affinity with EN groups from the Balkans, as well as groups in central Europe associated with the Continental Route, rather than North African groups from the southern Mediterranean (Figure 2B, Data S3.1, Data S5.5, Figure S10) (Haak et al., 2015; Olalde et al., 2015; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). It is therefore most parsimonious that the majority of early farmers in Sicily and Iberia descended from groups that expanded along a northern Mediterranean route, which share the same origin with the Continental Route in the Balkans and did not cross the Strait of Gibraltar and/or Sicily (van de Loosdrecht, 2021).

Overall, our study presents genetic and dietary transitions over a 6,000 years time transect from the same archaeological site. The genomic data from individuals from Grotta del’Uzzo show evidence for at least three genetic incursions during the Late Mesolithic, Early Neolithic, and Early Bronze Age, with the most significant population shift happening during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition. Combining genomic and isotopic evidence, we reveal that during the earliest Neolithic phase, resident HGs and incoming farmers were not only genetically interacting but also may have affected each others’ subsistence practices. It is important to note that the analysis of genomic ancestry alone may not detect acculturation. In this study and many previous reports for forager-farmer interactions, the acculturation of foragers could be detected only because of the joint analyses of genomic ancestry, stable isotope data and precise AMS radiocarbon dates together with archaeological context descriptions (Lipson et al., 2017b; Mathieson et al., 2018; Rivollat et al., 2020; van de Loosdrecht, 2021). Hence, multidisciplinary approaches form the most powerful research strategy to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the transition from foraging to sedentary farming in the Mediterranean (van de Loosdrecht, 2021).

Limitations of the study

An important merit of our study is to provide a view on genetic and dietary change in the early to middle Holocene at a single site in the center of the Mediterranean. Our sampling strategy succeeded in covering different phases of the Mesolithic and Neolithic, enabling us to detect key transitions in genomes and diet. However, the nature of prehistoric bone assemblages, especially when spread out across at least five millennia, makes it difficult to have at our disposal more than a few specimens for each phase. The transition from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic is a key time for our study, which has shown it to have been a short-term phase, likely lasting less than the age ranges detectable by means of radiocarbon dating. This implies that in archaeological terms, and particularly for a cave site with a complex stratigraphy and palimpsest-like deposits, we are dealing with a “needle in a haystack” scenario. Our interpretation of what may have happened around the time of contact between hunter-gatherers and early farmers thus relies mainly on genetic and isotopic data from three individuals (i.e., UZZ71, UZZ77, and UZZ81). Nevertheless, our reconstructions are not only based on the genetic and isotope data presented here but also on published isotope data (Mannino et al., 2015) as well as on a considerable amount of archaeological, zooarchaeological, and archaeobotanical research undertaken on G. dell’Uzzo (Costantini et al., 1987; Piperno et al., 1980a, 1980b; Tagliacozzo, 1993; Tusa, 1985, 1996). Another limitation that this kind of investigation has to contend with is the dearth of sites and deposits dating to the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition, which in the Mediterranean are represented by less than a handful of contexts (Biagi, 2003; Biagi and Starnini, 2016; Binder et al., 2012).

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Biological samples | ||

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ26 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ33 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ34 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ40 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ44 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ45 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ46 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ50 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ51 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ52 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ53 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ54 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ57 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ61 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ69 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ71 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ74 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ75 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ77 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ79 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ80 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ81 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ82 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ87 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ88 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ96 |

| Ancient skeletal element | This study | UZZ99 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| D1000 ScreenTapes | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067-5582 |

| D1000 Reagents | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5067-5583 |

| PfuTurbo Cx Hotstart DNA Polymerase | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 600412 |

| Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 600679 |

| 1x Tris-EDTA pH 8.0 | AppliChem | Cat# A8569,0500 |

| Sodiumhydroxide Pellets | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 10306200 |

| Sera-Mag Magnetic Speed-beads Carboxylate-Modified (1 mm, 3EDAC/PA5) | GE LifeScience | Cat# 65152105050250 |

| 0.5 M EDTA pH 8.0 | Life Technologies | Cat# AM9261 |

| 10x Buffer Tango | Life Technologies | Cat# BY5 |

| GeneRuler Ultra Low Range DNA Ladder | Life Technologies | Cat# SM1211 |

| Isopropanol | Merck | Cat# 1070222511 |

| Ethanol | Merck | Cat# 1009832511 |

| USER enzyme | New England Biolabs | Cat# M5505 |

| Uracil Glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0281 |

| Bst DNA Polymerase2.0, large frag. | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0537 |

| BSA 20 mg/mL | New England Biolabs | Cat# B9000 |

| T4 Polynucleotide Kinase | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0201 |

| T4 DNA Polymerase | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0203 |

| PEG-8000 | Promega | Cat# V3011 |

| 20% SDS | Serva | Cat# 39575.01 |

| Proteinase K | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# P2308 |

| Guanidine hydrochloride | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# G3272 |

| 3M Sodium Acetate (pH 5.2) | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# S7899 |

| Water | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# 34877 |

| Tween-20 | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# P9416 |

| 5M NaCl | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# S5150 |

| Denhardt’s solution | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# D9905 |

| ATP 100 mM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# R0441 |

| 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15568025 |

| dNTP Mix | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# R1121 |

| SSC Buffer (20x) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# AM9770 |

| GeneAmp 10x PCR Gold Buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 4379874 |

| Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 65602 |

| Salmon sperm DNA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 15632-011 |

| Human Cot-I DNA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15279011 |

| 0.5M HCl | Carl Roth | Cat# 9277.1 |

| HNO3 | Merck | Cat# 1.00456.2500 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| High Pure Viral Nucleic Acid Large Volume Kit | Roche | Cat# 5114403001 |

| HiSeq 4000 SBS Kit (50/75 cycles) | Illumina | Cat# FC-410-1001/2 |

| DyNAmo Flash SYBR Green qPCR Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# F415L |

| MinElute PCR Purification Kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 28006 |

| Quick Ligation Kit | New England Biolabs | Cat# M2200L |

| Oligo aCGH/Chip-on-Chip Hybridization Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 5188-5220 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data (European nucleotide archive) | This study | ENA: PRJEB50762 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| EAGER 1.92.21 | Peltzer et al., (2016) | https://eager.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ |

| AdapterRemoval 2.2.0 | Schubert et al. (2016) | https://github.com/MikkelSchubert/adapterremoval |

| BWA 0.7.12 | Li and Durbin (2009) | http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/ |

| DeDup 0.12.1 | Peltzer et al., (2016) | https://github.com/apeltzer/DeDup |

| DamageProfiler v0.3 | https://github.com/apeltzer/DamageProfiler | https://github.com/apeltzer/DamageProfiler |

| bamUtil 1.0.13 | https://github.com/statgen/bamUtil | https://github.com/statgen/bamUtil |

| CircularMapper v1.93.4 | Peltzer et al., (2016) | https://github.com/apeltzer/CircularMapper |

| Schmutzi v1.0 | Renaud et al. (2015) | https://github.com/grenaud/schmutzi |

| ContaMix v1.0.10 | Fu et al., 2013b | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044 |

| HaploGrep2 v2.1.1 | Weissensteiner et al. (2016) | https://haplogrep.i-med.ac.at/category/haplogrep2/ |

| SAMtools 1.3 | Li et al., (2009) | http://www.htslib.org/doc/samtools.html |

| pileupCaller v1.4.0 | https://github.com/stschiff/sequenceTools | https://github.com/stschiff/sequenceTools |

| ANGSD 0.910 | Korneliussen et al. (2014) | http://www.popgen.dk/angsd/index.php/ANGSD |

| EIGENSOFT 6.0.1 | Patterson et al. (2006) | https://github.com/DReichLab/EIG |

| ADMIXTOOLS v5.1 | Patterson et al. (2012) | https://github.com/DReichLab/AdmixTools |

| DATES 753 | Narasimhan et al., (2019) | https://github.com/priyamoorjani/DATES |

| HapROH 0.1 | Ringbauer et al. (2021) | https://pypi.org/project/hapROH/ |

| OxCal 4.4 | Bronk Ramsey (2009) | https://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/oxcal/OxCal.html |

| Geneious v9.0.5 | http://www.geneious.com | http://www.geneious.com |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Johannes Krause (krause@eva.mpg.de).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Grotta dell’Uzzo: Archaeology and stratigraphic sequence

The site, its burial ground and human remains

Grotta dell’Uzzo is a large shelter-like cave located in northwestern Sicily, along the eastern cliffs of the San Vito lo Capo peninsula (Figure S1). The site was visited hastily in 1927 by the French archaeologist Raymond Vaufrey, who did not realize its importance. The discovery of the deposit and its stratification was made in the early 1970s by Giovanni Mannino (Mannino, 1973), who excavated a small test trench in the cave, exposing a sequence of in situ Mesolithic deposits (identified as Epipaleolitico). Prehistoric deposits were excavated during the 1970s, 1980s and in 2004 in a number of trenches both inside and outside the overhang of the cave (Figure S1). This revealed that the site was occupied from at least the late Upper Palaeolithic through the Mesolithic and into the Neolithic (Conte and Tusa, 2012; Piperno et al., 1980a; Piperno and Tusa, 1976; Tagliacozzo, 1993). The cave was also occupied during the Bronze Age and throughout history, and until recently was used by shepherds as a stable for sheep.

This long stratigraphic sequence covering the transition from hunter-gatherer to agro-pastoral economies make Grotta dell’Uzzo a key site for understanding Mediterranean prehistory (Mannino et al., 2007, 2015; Piperno et al., 1980b; Tagliacozzo, 1993; Tusa, 1985, 1996). It is a unique site, given that Mediterranean sites with such continuous and intact sequences covering the late Mesolithic to the early Neolithic are rare, possibly as a consequence of a decrease in hunter-gatherer populations at the end of the Mesolithic (Biagi, 2003).

Another important feature of this cave site is that during the Mesolithic it was used as a burial ground. A total of 11 burials and 13 inhumated individuals (six males, four females and three infants) have been recovered at Grotta dell’Uzzo in the course of excavations in the 1970s, 1980s and 2004, close to the walls of the ‘inner part’ of the cave (Borgognini Tarli et al., 1993; Conte and Tusa, 2012; Di Salvo et al., 2012). Studies on the dental pathologies of the inhumated humans established that plant foods were an important component of the diet of the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (Silvana et al., 1985). On the other hand, isotopic and zooarchaeological investigations show that the occupants of Grotta dell’Uzzo relied heavily on animal protein, which through time originated increasingly from marine ecosystems (Mannino et al., 2015; Tagliacozzo, 1993).

Human remains at the cave were, however, also found scattered through the deposits of Grotta dell’Uzzo. Radiocarbon dating ascertained that these remains were not only Mesolithic but dated to all the main phases of cave occupation, including the so-called Mesolithic-Neolithic transition phase and Neolithic phases (Mannino et al., 2015). As part of the same study, 70 human bones were sampled, of which 57 were recovered from the burials and 13 commingled within the deposits. In total, only 33 bones yielded collagen extracts and 10 of these were from the bones recovered outside of the burials. Only 40% of the bones from the burials yielded collagen extracts and not all of these met the quality criteria established by van Klinken (van Klinken, 1999), which is indicative of the poor state of preservation of the human skeletal remains from the burials (Mannino et al., 2015). On the other hand, 77% of the commingled bones yielded collagen extracts, all of which are well preserved. For this reason, and because our aim was to obtain genetic and further isotopic information on the main periods of cave occupation, we decided to target the loose human remains, many of which have been directly dated within the remit of this project.

Cultural succession at Grotta dell’Uzzo from the Mesolithic to Early Neolithic

Mesolithic

The lithic industries from the two oldest two phases of the Mesolithic at Grotta dell’Uzzo have not been studied in detail, but they are contemporary to the occurrence in Sicily of facies of Epigravettian tradition across the island, followed by Sauveterrian-like facies (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2016). In north-western Sicily, microlithic industries of Epigravettian tradition (labelled as Epigravettiano indifferenziato) have been identified at Grotta dell’Uzzo in the Mesolithic phases I and II (Guerreschi and Fontana, 2012), as well as at Grotta dell’Isolidda (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2016) and Grotta di Cala Mancina (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2012) on the western coast of the San Vito lo Capo peninsula. These industries demonstrate strong techno-cultural affinities between the Late Epigravettian and early Holocene hunter-gatherers of Sicily. On the other hand, Sauveterrian industries have not been clearly identified at Grotta dell’Uzzo, but Sauveterrian-like facies have been retrieved from the nearby site of Grotta dell’Isolidda (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2012) and at the westernmost end of Sicily on the island of Favignana at Grotta d’Oriente (Lo Vetro and Martini, 2012).

Levels 14 to 11 in both Trench F and Trench M have previously been defined as the so-called ‘Mesolithic-Neolithic transition phase’ (Costantini et al., 1987; Mannino et al., 2006, 2015, 2007; Piperno et al., 1980a; Piperno and Tusa, 1976; Tagliacozzo, 1993; Tusa, 1985), because this was an essentially Mesolithic phase with some Neolithic elements in its upper spits. A recent study of the lithic industry from these layers assigns this phase of cave occupation to the blade-and-trapeze techno-complex of the western Mediterranean Castelnovian tradition (Collina, 2015). The oldest date available for the lowermost spits of this phase obtained on charcoal from spits 14 and 13 of Trench F attributes this part to 9,000-8,580 cal BP (P-2734: 7,910 ± 70 BP (Piperno, 1985)), which is one of the oldest chronological attributions for a blade-and-trapeze industry (Castelnovian sensu lato). The most recent reassessment of the radiocarbon chronology for Grotta dell’Uzzo, based on Bayesian modelling of the sequence of dates available for Trench F, suggests that the phase associated with the Castelnovian facies may have spanned ∼8,770-7,850 cal BP (Mannino et al., 2015). The following phase is the Neolithic phase I, which according to the above-mentioned Bayesian model may have spanned ∼8,050-7,400 cal BP (Mannino et al., 2015).

The blade-and-trapeze Castelnovian (sensu lato) complex of the ninth millennium BP is in technical continuity with the Neolithic complexes of the following Impressed Ware and Stentinello/Kronio culture of the VI millennium BCE. The production of trapezes constitutes the defining element of the lithic techno-complexes between the VII and VI millennia BCE. This was achieved through a notable standardization of the production processes, particularly through the application of pressure by different modalities (Collina, 2015). Nevertheless, the variability in some technical behaviours (e.g., bladelet fracturing techniques, presence/absence of the microburin technique, façonage processes of the trapeze truncations) is linked with a break and discontinuity in the Mesolithic-Neolithic technical traditions (Collina, 2015).

Early Neolithic

The early Neolithic in Sicily has been defined based on sites in the western part of the island (i.e., Grotta dell’Uzzo, Grotta del Kronio) and is characterized by three main cultural horizons, which in chronological order are: ‘Archaic Impressed Ware’ (ceramiche impresse arcaiche), ‘Advanced Impressed Ware’ (ceramiche impresse evolute) of facies Stentinello I and ‘Advanced Impressed Ware’ (ceramiche impresse evolute) of facies Stentinello II (Natali and Forgia, 2018). The chronology of these horizons is largely based on the dating at Grotta dell’Uzzo, which for this part of the sequence does not see full consensus between the different scholars who worked on the site, depending on whether the beginning of the Neolithic is taken to coincide with Spit 12 of Trench F, as proposed by Tiné and Tusa (Tiné and Tusa, 2012), or with Spit 10 of Trench F, as proposed by Tagliacozzo (Tagliacozzo, 1993) and Collina (Collina, 2015).

The early Neolithic witnessed the introduction of agro-pastoralism, with domestic cereals and animals playing a role in the local economy from the very inception of this cultural phase (Costantini et al., 1987; Tagliacozzo, 1993). However, it should be noted that hunting was still practiced and fishing actually increased following the introduction of farming, with a focus on species such as grouper that could be caught onshore. The early Neolithic was, thus, a phase with a very mixed economy based on a combination of hunting, fishing and agro-pastoralism.

In the course of the middle and late Neolithic, the subsistence economy became increasingly less reliant on wild recources and more focussed on domesticates (Tagliacozzo, 1993). This tendency continued through the Copper Age and Bronze Age, when pastoralism seems to have played a more pronounced role within an almost terrestrially based agro-pastoral economy (Tusa, 1999). The deposits at Grotta dell’Uzzo do not allow us to ascertain whether this site was occupied continuously from the Neolithic through the Copper Age, when the Bell Beaker Culture (Campaniforme) dominated western Sicily, and into the Bronze Age. Nevertheless, pottery fragments attributable to the Rodì-Tindari-Vallelunga and Thapsos-Milazzese cultures suggest that the cave was also frequented in the Early and possibly Middle Bronze Age.

Method details

Ancient DNA processing

All pre-amplification laboratory work was performed in dedicated clean rooms (Gilbert et al., 2005) at the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for the Science of Human history (SHH) in Jena and MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology (EVA) in Leipzig, Germany. At the MPI-SHH the individuals were sampled for bone or tooth powder, originating from various skeletal elements (e.g., petrous, molars, teeth, humerus, phalange, tibia, see Data S1.1). The outer layer of the skeletal elements was removed with high-pressured powdered aluminium oxide in a sandblasting instrument, and the element was irradiated with ultraviolet (UV) light for 15 min on all sides. The elements were then sampled using various strategies, including grinding with mortar and pestle or cutting and followed by drilling into denser regions (Data S1.1). Subsequently, for each individual 1-8 extracts of 100uL were generated from ∼50mg powder per extract, following a modified version of a silica-based DNA extraction method (Dabney et al., 2013) described earlier (Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019) (Data S1.1). At the MPI-SHH, 20uL undiluted extract aliquots were converted into double-indexed double stranded (ds-) libraries following established protocols (Meyer et al., 2012; Meyer and Kircher, 2010), some of them with a partial uracil-DNA glycosylase (‘ds UDG-half’) treatment (Rohland et al., 2015) and others without (‘ds non-UDG’).

At the MPI-EVA, 30uL undiluted extract aliquot was converted into double-indexed single-stranded (ss-) libraries (Gansauge et al., 2017) with minor modifications detailed in (Slon et al., 2017), without UDG treatment (‘ss non-UDG’) (Data S1.1). At the MPI-SHH, all the ds- and ss-libraries were shotgun sequenced to check for aDNA preservation, and subsequently enriched using in-solution capture probes following a modified version of (Fu et al., 2013a, 2013b) (described in (Feldman et al., 2019)) for ∼1240k single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the nuclear genome (Fu et al., 2015) and independently for the complete mitogenome. Then the captured libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq4000 platform using either a single end (1x75bp reads) or paired end configuration (2x50bp reads).

The sequenced reads were demultiplexed according to the expected index pair for each library, allowing one mismatch per 7 bp index, and subsequently processed using EAGER v1.92.21 (Peltzer et al., 2016). We used AdapterRemoval v2.2.0 (Schubert et al., 2016) to clip adapters and Ns stretches of the reads. We merged paired end reads into a single sequence for regions with a minimal overlap of 30 bp, and single end reads smaller than 30 bp in length were discarded. The reads obtained from the nuclear capture were aligned against the human reference genome (hg19), and those from the mitogenome captured against the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS). For mapping we used the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA v0.7.12) aln and samse programs (Li and Durbin, 2009) with a lenient stringency parameter of ‘-n 0.01’ that allows more mismatches, and ‘-l 16500’ to disable seeding. We excluded reads with Phred-scaled mapping quality (MAPQ) < 25 using SAMtools 1.3 (Li et al., 2009). Duplicate reads, identified by having identical strand orientation, start and end positions, were removed using DeDup v.0.12.1 (Peltzer et al., 2016).

Isotope analyses and radiocarbon dating

For the present research, we have undertaken collagen extraction for isotope analysis and radiocarbon dating of all specimens that have been genetically-typed. The isotopic and elemental data obtained by analyzing the collagen extracts from the Grotta dell’Uzzo humans are shown in Table S1, whilst the results of the radiocarbon dating are listed in Table S2.

In total, 22 samples were pretreated using the method proposed by Talamo and Richards (Talamo and Richards, 2011), which is based on the pretreatment originally established by Longin (Longin, 1971) and modified by Brown et al. (Brown et al., 1988). Two samples (R-EVA 3521,3523) were extracted using the method for small samples in Fewlass et al. (Fewlass et al., 2019). All of the sampled specimens yielded extracts, which can be considered well-preserved collagen according to the quality criteria established by van Klinken (van Klinken, 1999). All individuals can, thus, be used for isotopic dietary reconstructions and AMS radiocarbon dating.

Direct AMS 14C bone dates

We obtained a direct 14C date from 19 skeletal element and 17 of them were used in genetic analysis (Table S2). All bone samples were pretreated at the Department of Human Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA), Leipzig, Germany, using the method described in (Talamo and Richards, 2011). For each skeletal element, 200-500mg of bone/tooth powder was decalcified in 0.5M HCl at room temperature ∼4 h until no CO2 effervescence was observed. To remove humic acids, in a first step 0.1M NaOH was added for 30 min, followed by a final 0.5M HCl step for 15 min. The resulting solid was gelatinized following a protocol of (Longin, 1971) at pH 3 in a heater block at 75°C for 20h. The gelatin was then filtered in an Eeze-Filter™ (Elkay Laboratory Products (UK) Ltd.) to remove small (>80 um) particles, and ultrafiltered (Brown et al., 1988) with Sartorius “VivaspinTurbo” 30 KDa ultrafilters. Prior to use, the filter was cleaned to remove carbon containing humectants (Brock et al., 2007). The samples were lyophilized for 48 h. In order to monitor contamination introduced during the pre-treatment stage, a sample from a cave bear bone, kindly provided by D. Döppes (MAMS, Germany), was extracted along with the batch from Grotta dell’Uzzo (Korlević et al., 2018). In marine environments the radiocarbon is older than the true age, usually by ∼400 years (marine reservoir effect). Dates were calibrated with the OxCal 4.4 software (Bronk Ramsey, 2009) using the IntCal20 curve (Reimer et al., 2020) and, in addition, the Marine20 curve (Heaton et al., 2020) for individuals that had clearly consumed marine protein. The estimation of the amount of marine protein consumed is based on calculations made for specimen S-EVA 8010 (40 ± 10% marine) by Mannino et al. (Mannino et al., 2015). The individuals for which a correction was necessary are UZZ4446 (40 ± 10% marine), UZZ81 (45 ± 10% marine), UZZ69, UZZ79 and UZZ80 (50 ± 10% marine). Corrections were made using the reservoir correction estimated for the Mediterranean Basin by Reimer and McCormac (Reimer and McCormac, 2002), which is ΔR = 58 ± 85 14C yr.

Isotope analysis

For 19 individuals we determined the carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope values for dietary inference (Table S1). To assess the preservation of the collagen yield, C:N ratios, together with isotopic values are evaluated following the limits of van Klinken 1999 (van Klinken, 1999). The details for Isotope analysis are provided in Data S5.1.

Quantification and statistical analysis

aDNA authentication and quality control

We assessed the authenticity and contamination levels in our ancient DNA libraries (unmerged and merged per-individual) in several ways. First, we checked the cytosine deamination rates at the end of the reads (Briggs et al., 2007) using DamageProfiler v0.3 (https://github.com/apeltzer/DamageProfiler). After merging the libraries for each individual, we observed 21-52% C > T mismatch rates at the first base in the terminal nucleotide at the 5′-end, an observation that is compatible with the presence of authentic ancient DNA molecules.

Second, we tested for contamination of the nuclear genome in males based on the X-chromosomal polymorphism rate. We determined the genetic sex by calculating the X-rate (coverage of X-chromosomal SNPs/ coverage of autosomal SNPs) and Y-rate (coverage of Y-chromosomal SNPs/ coverage of autosomal SNPs) (Fu et al., 2016). Six individuals for which the libraries showed a Y-rate ≥ 0.49 we assigned the label ‘male’ and 14 individuals with Y-rates 0.07 as ‘female’. The individual UZZ26.cont with an intermediate Y-rate of 0.17 we excluded from further genetic analyses. Then we tested for heterozygosity of the X-chromosome using ANGSD v0.910 (≥200 X-chromosomal SNPs, covered at least twice)(Korneliussen et al., 2014). Based on new Method1, we found a nuclear contamination of 0.9-4.4% for five male individuals (Data S1.1) and 18.5% in individual UZZ99, which was also excluded from further analyses.

Third, we obtained two mtDNA contamination estimates for genetic males and females, using ContaMix v1.0.10 (Fu et al., 2013b) and Schmutzi v1.0 (Renaud et al., 2015). Before running Schmutzi, we realigned the reads to the rCRS using CircularMapper v1.93.4 filtering with MAPQ <30. After removing duplicate reads, we downsampled to ∼30,000 reads per library. With Schmutzi we found low contamination estimates of 1-3% for all individuals with sufficient coverage (Data S1.1). ContaMix returned estimates in the range of 0.0-5.6% for all individuals except for UZZ69 (3.7-10.6%) and the lower coverage individual UZZ096 (0.3-13.5%).

Dataset

For genotyping we extracted reads with high mapping quality (MAPQ ≥37) to the autosomes using samtools v1.3. The DNA damage plots indicated that misincorporations could extend up to 10 bp from the read termini in non-UDG treated and up to 3bp in UDG-half treated libraries. We hence clipped the reads accordingly, thereby removing G > A transitions from the terminal read ends in ds-libraries and C > T transitions in both ss- and ds-libraries. For each individual, we randomly chose a single base per SNP site as a pseudo-haploid genotype with our custom program ‘pileupCaller’ (https://github.com/stschiff/sequenceTools). We intersected our data with a global set of high-coverage genomes from the Simon Genome Diversity Project (SGDP) for ∼1240k nuclear SNP positions (Mallick et al., 2016), including previously reported ancient individuals (Allentoft et al., 2015; Antonio et al., 2019; Brace et al., 2019; Broushaki et al., 2016; Brunel et al., 2020; Catalano et al., 2020; Damgaard et al., 2018; Feldman et al., 2019; Fernandes et al., 2020; Fregel et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2014, 2016; Gamba et al., 2014; Günther et al., 2015; Hofmanová et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2015, 2017, 2015; Keller et al., 2012; Kılınç et al., 2016; Lazaridis et al., 2014, 2016, 2017; Lipson et al., 2017b; Llorente et al., 2015; Mallick et al., 2016; Marcus et al., 2020; Mathieson et al., 2018; Meyer et al., 2012; Mittnik et al., 2018; Olalde et al., 2015, 2018, 2019; Omrak et al., 2016; Raghavan et al., 2014; Rivollat et al., 2020; Saag et al., 2017; Sikora et al., 2017; Skoglund et al., 2014; Valdiosera et al., 2018; Villalba-Mouco et al., 2019). To minimize the effects of residual ancient DNA damage, we removed ∼300k SNPs on CpG islands from the data set. CpG dinucleotides, where a cytosine is followed by a guanine nucleotide, are frequent targets of DNA methylation (Kennett et al., 2017). Post-mortem cytosine deamination was shown to occur more frequently at methylated than unmethylated CpGs (Seguin-Orlando et al., 2015) resulting in excess of CpG → TpG conversions. The final data set includes 868,755 intersecting autosomal SNPs for which our newly reported individuals cover 53,352-796,174 SNP positions with an average read depth per SNP of 0.09-9.39X (Data S1.1). For principal component analyses (PCA) we intersected our data and published ancient genomes with a panel of worldwide present-day populations, genotyped on the Affymetrix Human Origins (HO) (Lazaridis et al., 2014; Patterson et al., 2012). After filtering out CpG dinucleotides this data set includes 441,774 SNPs.

Biological relatedness and individual assessment

We determined pairwise mismatch rates (PMRs) (Kennett et al., 2017; Kılınç et al., 2016) for pseudo-haploid genotypes to check for genetic duplicate individuals and first-degree relatives. If two samples show similar levels of PMR for inter- and intra-individual library comparisons, then this indicates a genetic duplicate. Moreover, the expected PMR for two first-degree related individuals falls approximately in the middle of the baseline values for comparison between genetically unrelated and identical individuals (van de Loosdrecht et al., 2018). We found a genetic triplicate (UZZ44, -45, −46) and quintuplicate (UZZ50-54) (Data S1.4). After confirmation from uniparental marker analyses for similar haplotypes and an absence of detectable (cross-)contamination for each of the libraries within these library sets, we merged the sets into UZZ4446 and UZZ5054, respectively (Data S1.1). In addition, UZZ79 and UZZ81 showed an elevated PMR indicative of a close biological relationship (Data S1.4). We therefore remove from UZZ81 the group-based f-statistics and DATES analysis.

Mitogenome haplogroup determination

We could reconstruct the mitochondrial genomes for 17 individuals (Data S1.1). To obtain an automated mitochondrial haplogroup assignment we imported the consensus sequences from Schmutzi into HaploGrep2 v2.1.1 (available via: https://haplogrep.i-med.ac.at/category/haplogrep2/) (Weissensteiner et al., 2016) based on phylotree (mtDNA tree build 17, available via http://www.phylotree.org/) (van Oven and Kayser, 2009). In parallel, we manually haplotyped the reconstructed mitogenomes, based on a procedure described in (Posth et al., 2016). We imported the bam.files for the merged libraries into Geneious v.9.0.5 (http://www.geneious.com) (Kearse et al., 2012). After reassembling the reads against the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS) we called SNP variants with a minimum variant frequency of 0.7 and 2.0X coverage.

Using phylotree, we double-checked whether the called variants matched the expected diagnostic ones based on the automated HaploGrep assignment. We did not consider known unstable nucleotide positions 309.1C(C), 315.1C, AC indels at 515-522, 16093C, 16182C, 16183C, 16193.1C(C) and 16519. We extracted the consensus sequences based on a minimum of 75% base similarity. Using this approach, we identified a total of twelve lineage-specific and private variants in the high coverage UZZ5054 mitogenome. Four of the lineage-specific variant positions were covered by only one or two reads in the low coverage UZZ96 and OrienteC genomes, and hence fell initially below our frequency threshold for variant detection. However, since these variants were covered by a large number of reads in the closely related UZZ5054 mitogenome, for UZZ96 and OrienteC we based the variant calls at these positions on the few reads available and adjusted their consensus sequences accordingly (Data S1.3).

Y-chromosome haplogroup determination

To assign Y haplogroups, for each individual, we assembled pileups of every covered site, filtered for sites found on the ISOGG SNP list v14.48 (https://isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_YDNA_SNP_Index.html). For each individual we manually inspected this list to determine to which Y haplogroup our individuals most likely belonged, using the script published in Rohrlach et al. 2021 (Rohrlach et al., 2021). The output CSV files with ancestral and derived alleles coverage on ISOGG SNPs are provided in Data S4.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

We computed principal components from individuals from 43 modern West Eurasian groups in the Human Origin panel (Lazaridis et al., 2014; Patterson et al., 2012) using the smartpca program in the EIGENSOFT package v6.0.1 (Patterson et al., 2006) with the parameter ‘numeroutlieriter:0’. Ancient individuals were projected using ‘lsqproject:YES’ and ‘shrinkmode:YES’.

f-statistics

We performed f-statistics on the 1240k data set using ADMIXTOOLS 5.1 (Patterson et al., 2012). For f3-outgroup statistics (Reich et al., 2009) we used qp3Pop and for f4-statistics qpDstat with f4mode:YES. Standard errors (SEs) were determined using a weighted block jackknife over 5Mb blocks. F3-outgroup statistics of the form f3(O;A,B) test the null hypothesis that O is a true outgroup to A and B. The strength of the f3-statistic is a measure for the amount of genetic drift that A and B share after they branched off from a common ancestor with O, provided that A and B are not related by admixture. F4-statistics of the form f4(X,Y; A,B) test the null hypothesis that the unrooted tree topology ((X,Y)(A,B)), in which (X,Y) form a clade with regard to (A,B), reflects the true phylogeny. A positive value indicates that either X and A, or Y and B, share more drift than expected under the null hypothesis. A negative value indicates that the tree topology under the null-hypothesis is rejected into the other direction, due to more shared drift between Y and A, or X and B.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS)

We performed MDS using the R package cmdscale. Euclidean distances were computed from the genetic distances among West-Eurasian HG, as measured by f3(Mbuti; HG1, HG2) for all possible pairwise combinations (Fu et al., 2016). The two dimensions are plotted. We restricted the analyses to individuals with >30,000 autosomal SNPs covered. Relevant previously published West Eurasian HGs were pooled in groups according to their geographical or temporal context, following their initial publication labels.

Nucleotide diversity

We determined the nucleotide diversity (π) from pseudo-haploid genotypes by calculating the proportion of nucleotide mismatches for overlapping autosomal SNPs covered by at least one read in both individuals. We hence determined π from all possible combinations of individual pairs, rather than from all possible chromosome pairs, within a given group. We filtered out individual pairs that shared less than 30,000 SNPs covered. We calculated an average over all the individual pairs within a group and determined standard errors from block jackknifes over 5Mb windows and 95% confidence intervals (95CIs) from 1,000 bootstraps.

HapROH

The ROH segments were detected using HapROH (Ringbauer et al., 2021), for selected ancient individuals with >400k SNPs covered in pseudo-haploid genotyping.

Inference of mixture proportions

To characterize the ancestry of the ancient Sicilians we used the qpWave (Haak et al., 2015) and qpAdm (Lazaridis et al., 2016) programs from the Admixtools v5.1 package, with the ‘allsnps: YES’ option. qpWave tests whether a set of Left populations is consistent with being related via as few as N streams of ancestry to a set of Outgroup populations. qpAdm tries to fit a Target as a linear combination of the Left/Source populations, and estimates the respective ancestry proportions that each of the Left populations contributed to the Target. Both qpWave and qpAdm are based on f4-statistics of the form f4(X,O1;O2,O3), where O1, O2, O3 are all the triplet combinations of the Outgroup populations, and X is a Target or Left/Source population. Since missing data may inflate the P-values for this test, we required a test result to be smaller (less extreme) than p = 0.1 in order to reject the null-hypothesis of a full ancestry fit between the Target and the Left/Source population(s). Prior to running qpAdm we used qpWave to check whether the pairs of Left/Source populations are not equally related to the Outgroups.

For the modeling of the HGs we used the Outgroup set: Mbuti, Mota, Iberomaurusian, CHG, Natufian, Mal’ta, AfontovaGora3, GoyetQ116, Ust Ishim, Kostenki14, Vestonice16, Villabruna, Karitiana, Papuan, Onge. For the modeling of the early farmers, we extended the above OG set with EHG and Pinarbasi (AHG) to differentiate more strongly between the European HG and EEF ancestry on one hand, and any underlying WHG-EHG/AHG admixture structure in European HGs. For a generalised European HG ancestry to model the European early farmers, we combined the following HG into one gene pool: Ukraine (I5876), Iron Gates (I5771), Sicily (UZZ69), peninsular Italy (R15), Iberia (LaBrana1, CMS001), Germany (BOT005, Falkenstein), Luxembourg (Loschbour), Hungary (I1507), France (PER3023, Ranchot), England (I3025).

Admixture dating

The admixture event in Sicily LM HGs was dated using an ancestry covariance pattern-based DATES 753 program (Narasimhan et al., 2019), with Sicily EM HGs and EHGs as two ancestors. The bin size for covariance calculation was 0.1cM and exponential fitting started at 0.5cM. The standard error was determined using jackknife and a generation time of 29 years was used for admixture date calculation.

Phylogeny modelling

We used the qpGraph program (Patterson et al., 2012) to construct a phylogeny of ancestry lineages found among Palaeolithic and Mesolithic West-Eurasian HG to clarify the genetic history of Sicily EM HGs. For our modelling we used the parameters ‘useallsnps: YES’, ‘hires: YES’ to improve the resolution and used Mbuti.DG as the outgroup. We started from a published skeleton graph with six populations: 1) Mbuti, 2) Ust Ishim, 3) Kostenki14, 4) GoyetQ116-1, 5) Mal’ta, 6) Villabruna (Fu et al., 2016), then added Sicily EM HGs, GoyetQ2 or ElMiron on the graph (Data S5.4). After getting the best fitted model with Sicily EM HGs, we further added GoyetQ2, ElMiron and Loschbour on the model to examine the relationship between Villabruna, Sicily EM HGs with Magdalenians and WHG.

Acknowledgments