Abstract

The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is currently ongoing. It is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). A high proportion of COVID-19 patients exhibit gastrointestinal manifestations such as diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. Moreover, the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts are the primary habitats of human microbiota and targets for SARS-CoV-2 infection as they express angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) at high levels. There is accumulating evidence that the microbiota are significantly altered in patients with COVID-19 and post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS). Microbiota are powerful immunomodulatory factors in various human diseases, such as diabetes, obesity, cancers, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and certain viral infections. In the present review, we explore the associations between host microbiota and COVID-19 in terms of their clinical relevance. Microbiota-derived metabolites or components are the main mediators of microbiota-host interactions that influence host immunity. Hence, we discuss the potential mechanisms by which microbiota-derived metabolites or components modulate the host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Finally, we review and discuss a variety of possible microbiota-based prophylaxes and therapies for COVID-19 and PACS, including fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), probiotics, prebiotics, microbiota-derived metabolites, and engineered symbiotic bacteria. This treatment strategy could modulate host microbiota and mitigate virus-induced inflammation.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Infectious diseases

Introduction

There are tenfold more bacterial cells in the human microbiota than there are human tissue cells and there are 100-fold more bacterial than human genes.1–4 These bacteria inhabit all surfaces of the human body including the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts.5–8 The human body selectively permits certain bacteria to colonize it, and it furnishes them with a suitable habitat. Microbiota serve multiple important functions in and on the human body such the decomposition of indigestible carbohydrates and proteins, nutrient digestion and absorption, vitamin biosynthesis, and host immunity induction, instruction, and function.9–13 The microbiota influence human health and are associated with several diseases.

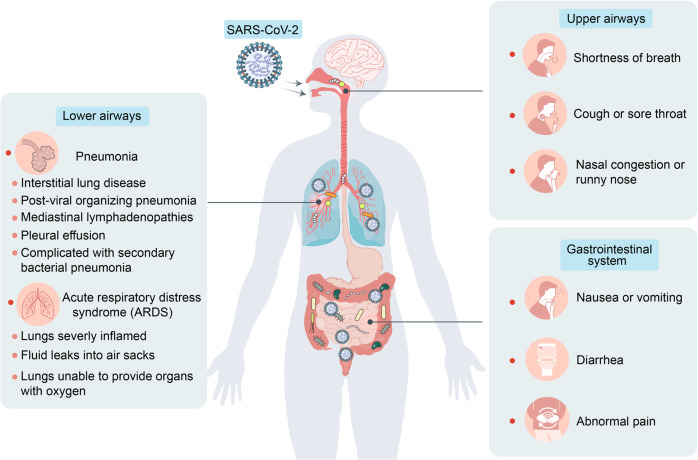

The global coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and has posed serious threats to public health and the global economy.14 Patients with COVID-19 present with symptoms of respiratory infection including fever, fatigue, abnormal chest X-ray, cough, and shortness of breath.15–18 Furthermore, a high proportion of COVID-19 patients also exhibit gastrointestinal manifestations such as diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, anorexia, and abdominal pain (Fig. 1).19–21 Evidence from clinical studies suggests that respiratory and gastrointestinal microbiota homeostasis is disrupted in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.22–27 SARS-CoV-2 may predispose patients to secondary pathogen infections of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. These are responsible for much of the morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19.28,29 Therefore, microbiota may play important roles in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19-associated respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms. Various respiratory and gastrointestinal manifestations occur in patients with COVID-19 including shortness of breath, cough or sore throat, nasal congestion or runny nose, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain

The aim of this review was to summarize the relationships between microbiota and COVID-19 in terms of their clinical relevance and immunological mechanisms. We also explored various interventions that target microbiota, are based on the immunological interplay between the microbiota and COVID-19, and could optimize anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapies.

Microbiota and COVID-19

Respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts are primary habitats of human microbiota and targets for SARS-CoV-2 infection

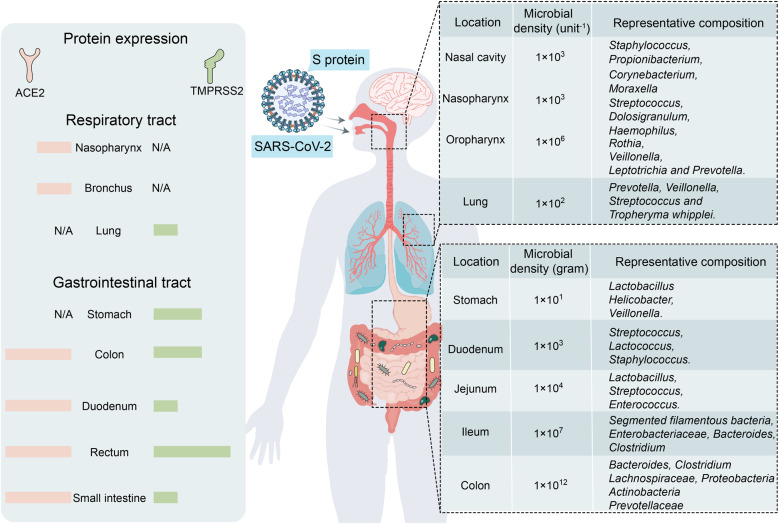

SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent of COVID-19. It is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus of the genus Betacoronavirus.30,31 It encodes membrane (M), nucleocapsid (N), spike (S), and envelope (E) structural proteins and multiple non-structural proteins.32 SARS-CoV-2 obligately requires the S protein to penetrate host cells.33 On the virion, the S protein is a homotrimer comprising S1 and S2 subunits. The former binds host angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) while the latter mediates membrane fusion.34–36 The virus hijacks host cell-surface proteases such as transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) which, in turn, activates viral S protein, cleaves ACE2 receptors, and facilitates viral binding to the host cell membrane.37–39 In addition to ACE2 and TMPRSS2-mediated entry, SARS-Cov-2 can also utilize the phagocytosis or endocytosis function of host cells to invade certain immune cell types such as macrophages.40 ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are strongly expressed in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. As the latter communicates with the external environment, they are the major targets of SARS-CoV-2 invasion (Fig. 2).41–46 Moreover, both of these organ systems harbor large microbial populations.

Fig. 2.

Primary habitats of human microbiota: respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts as SARS-CoV-2 infection targets. SARS-CoV-2 receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are expressed mainly in respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts which provide many suitable habitats for microorganisms. The right side of the figure lists representative bacterial populations in different parts of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts

Gas exchange is the primary function of the respiratory tract. To perform gas exchange efficiently, adult human airways have approximately 40-fold larger surface area than skin.47 However, this tissue surface also provides numerous habitats suitable for microorganisms. High bacterial densities (103–106 U−1) occur in healthy upper airways including the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, and oropharynx. In contrast, the lung has slightly lower bacterial densities (~102 U−1).48 Healthy upper airways are typically populated by Staphylococcus, Propionibacterium, Leptotrichia, Rothia, Dolosigranulum, Haemophilus, Moraxella, Veillonella, and Corynebacterium. Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Haemophilus are the main genera inhabiting healthy lungs. Prevotella and Streptococcus occur in both upper airways and lungs.5,48–50 Evidence from prior research demonstrated that commensal bacteria in the respiratory tract help prevent pathogens from establishing infections and spreading on the mucosal surfaces.48,51 This phenomenon is known as “colonization resistance”. Hence, respiratory tract microbiota might help prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection. By preventing SARS-CoV-2 colonization on the mucosal surfaces, microbiota could inhibit the virus infection to a certain degree.

Respiratory droplet and fomite transmission may be the primary modes of SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nevertheless, a recent study suggested that SARS-CoV-2 may also be spread via the fecal–oral route.52 As ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are highly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract, SARS-CoV-2 also targets the gut.45,46 Several studies reported that stool samples from patients with COVID-19 were positive for SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA. Endoscopy revealed colon damage in these patients. Thus, SARS-CoV-2 can infect the gastrointestinal tract.53–58 A population-based study conducted in China showed that viral RNA was detected in the stool samples of ≤53% of all COVID-19 patients.59 A biopsy performed on a COVID-19 patient disclosed the SARS-CoV-2 protein coat in the stomach, duodenum, and rectum.59 Therefore, both SARS-CoV-2 and its close relative SARS-CoV can infect the gut. The gut microflora are more abundant and diverse than those in the respiratory tract.60 A few studies confirmed that gut microbiota help regulate intestinal immune homeostasis and pathogen infection.61–63 For this reason, gut bacteria may be vital to the host immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 link microbiota with SARS-CoV-2 infection

The disease course of COVID-19 is characterized by the incubation, symptomatic, hyperinflammation, and resolution periods.64 The incubation period is usually ~1–14 d. In most cases, though, it is 3–7 d.16 Approximately 97.5% of all COVID-19 patients develop symptoms within 14 d of infection. Only 2.5% of them remain asymptomatic.16 The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 are highly variable but commonly include shortness of breath (53–80%), sputum production (34.3%), dry cough (60–86%), and sore throat (13.9%).19

Several clinical studies reported that 11–39% of all COVID-19 patients have gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain (Fig. 1).21,55,65–81 A study conducted in Chile reported that out of 7,016 patients with COVID-19, 11% displayed gastrointestinal symptoms.74 Jin et al. reported that among 651 patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China, 8.6% exhibited diarrhea while 4.15% presented with nausea or vomiting.21 Gastrointestinal symptoms are associated with a relatively higher risk of hospitalization and/or greater disease severity. In severe and/or critical patients, the disease progresses and causes complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, secondary pathogen pneumonia and end-stage organ failure. As microbiota maintain respiratory and gastrointestinal homeostasis and health, the foregoing COVID-19-associated symptoms may link microbiota with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Microbiota eubiosis is disturbed in patients with COVID-19

Emerging evidence suggests that the microbiota of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts are dramatically altered in COVID-19 patients. An early study in Guangdong Province, China revealed that the respiratory microbiota in COVID-19 patients have reduced α-diversity and elevated levels of opportunistic pathogenic bacteria.82 The researchers detected concomitant rhinovirus B, human herpes alphavirus 1 and human orthopneumovirus infection in 30.8% (4/13) of all severe COVID-19 patients but not in any mild cases. The major respiratory microbial taxa in the critically ill COVID-19 patients consisted of Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), Staphylococcus epidermidis, and/or Mycoplasma spp. In 23.1% (3/13) of all severe COVID-19 cases, clinical sputum and/or nasal secretion cultures confirmed the presence of BCC and S. epidermidis. In a critical COVID-19 patient, there was a time-dependent secondary Burkholderia cenocepacia infection and expression of multiple virulence genes that might have accelerated disease progress and hastened eventual death. A study conducted at Huashan Hospital in Shanghai, China reported that among 62 COVID-19 and 125 non-COVID-19 pneumonia cases, potentially pathogenic microbes were detected in 47% of the former, and 58% of the pathogens were respiratory viruses.24 A recent study demonstrated a link between respiratory microbiota and COVID-19 disease severity.23 Several potential confounding factors contributed to microbiota alteration in COVID-19. These included time spent in the intensive care unit (ICU), antibiotic administration, and type of oxygen support. The authors integrated microbiome sequencing, viral load determination, and immunoprofiling, and identified specific oral bacteria associated with relatively higher levels of proinflammatory markers in COVID-19 patients.

Gut dysbiosis in COVID-19 patients was also investigated. A shotgun metagenomics analysis of 15 COVID-19 patients hospitalized in Hong Kong disclosed that their fecal microbiomes were deficient in beneficial commensals and abundant in opportunistic pathogens.26 The researchers showed that compared with the gut microbiomes of healthy persons, those of patients with COVID-19 had low abundances of the anti-inflammatory bacteria Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia, Eubacterium, and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. The feces of COVID-19 patients were enriched in opportunistic pathogens known to cause bacteremia such as Clostridium hathewayi, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus, Actinomyces viscosus, and Bacteroides nordii. Gut dysbiosis persists even after clearance of SARS-CoV-2 infection or recovery from it. The gut fungi and virome comprise parts of the gut microbiota and are also altered in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Another study observed relatively increased proportions of opportunistic fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans, C. auris, and Aspergillus flavus in the feces of COVID-19 patients.25 Previous investigations showed that the foregoing fungal pathogens are associated with pneumonia and other respiratory infections.83–85 Therefore, gut fungi dysbiosis might contribute to fungal co-infections and/or secondary fungal infection in COVID-19 patients. Aspergillus co-infection was recently isolated from the respiratory tract secretions and tracheal aspirates of COVID-19 patients.86–90

The gut virome helps regulate intestinal immune homeostasis.91–93 A recent study used in-depth shotgun sequencing to investigate relative changes in the fecal virome of COVID-19 patients.27 There were increased proportions (11/19) of eukaryotic DNA viruses and decreased proportions (18/26) of prokaryotic DNA viruses (and especially bacteriophages) in the feces of COVID-19 patients possibly because of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The abundance of fecal eukaryotic viruses may increase to take advantage of the host immune dysfunction that may occur in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Analysis of the modifications in gut virome functionality revealed that in COVID-19 patients, stress, inflammation, and virulence responses were comparatively increased and included arginine repressor, hemolysin channel protein, and DNA polymerase IV expression and DNA repair.

The foregoing studies helped elucidate the relationships between microbiota and SARS-CoV2 infection and could, therefore, disclose possible gut microbiota interventions that reduce disease severity in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Gut dysbiosis is associated with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS)

Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS) is characterized by long-term complications and/or persistent symptoms following initial disease onset.94–99 The symptoms of PACS may be respiratory (cough, expectoration, nasal congestion/runny nose, and shortness of breath), neuropsychiatric (headache, dizziness, loss of taste, anosmia, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, insomnia, depression, poor memory, and blurred vision), gastrointestinal (nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal and epigastric pain), dermal (hair loss), musculoskeletal (arthralgia and muscle pain) and may also include fatigue.96,100–109 The underlying reasons for the emergence of PACS are unclear. A recent study revealed that gut dysbiosis might play a vital role in PACS.110 Stool samples were collected from 68 COVID-19 patients of whom 50 (73.5%) presented with PACS at six months after the initial COVID-19 diagnosis. There was no significant correlation between fecal or respiratory viral load and PACS development. However, a six-month follow-up indicated differences in the gut microbiota between patients with PACS and those without it. The gut microbiota of patients without PACS were comparable to those of healthy controls whereas those of patients with PACS substantially differed from those of the healthy controls at six months. In addition, patients with PACS have reduced bacterial diversity and richness than the healthy individuals. In contrast, the foregoing parameters did not significantly differ between patients without PACS and healthy controls. In the PACS patients, 28 and 14 gut bacterial species had decreased and increased, respectively, compared with the healthy controls. The authors examined the associations between the gut microbiome composition and the various PACS symptoms at six months. The R package MaAsLin2 (https://github.com/biobakery/Maaslin2) revealed that different PACS symptoms were related to different gut microbiota patterns. Eighty-one bacteria were associated with various PACS classes and many of these taxa were associated with at least two persistent symptoms.

The authors also investigated whether the gut microbiota profile at admission can influence PACS development. Analyses of stool samples at admission disclosed that bacterial clusters distinctly differed between patients with and without PACS. Compared with the PACS patients, those without PACS-COVID-19 presented with gut bacterial compositions that were enriched for 19 bacteria and characterized by Bifidobacterium, Brautia, and Bacteroidetes. Patients with PACS displayed significantly lower gut bacterial diversity and richness than those of healthy controls. Thirteen bacterial species including Blautia wexlerae and Bifidobacterium longum were negatively associated with PACS at six months. Hence, these species may have protective roles during recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. In contrast, Actinomyces sp S6 Spd3, Actinomyces johnsonii, and Atopobium parvulum were positively correlated with PACS. The authors also reported that certain bacterial species such as Ruminococcus gnavus, Clostridium innocuum, and Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum remained variable from admission to the 6-month follow-up and were associated with several PACS symptoms.

Taken together, the foregoing findings suggest that gut microbiota composition upon patient admission may reflect the susceptibility of the individual to long-term COVID-19 complications. As millions of people have been infected during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the discoveries of the preceding studies strongly suggest that gut microbiota modulation could facilitate timely recovery from COVID-19 and reduce the risk of acute PACS development.

Potential roles of microbiota in COVID-19

Microbiota may contribute to cytokine storms in COVID-19 patients

Inflammation is a protective immune response that helps clear sources of infection. However, chronic or excessive inflammation can cause autoimmune damage.111,112 In the early stages of the pandemic, inflammatory cytokine storms were observed in certain COVID-19 patients.113–115 Cytokine storms are also known as inflammatory factor storms or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).116 Excessive immunocyte activation releases large numbers of intracellular inflammatory factors including IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN, and complement protein. Consequently, immunocytes mount storm-like suicide attacks on pathogens and infected cells, cause collateral damage to healthy cells and tissues, increase vascular permeability, and disturb circulation.117 The underlying mechanisms of the inflammatory factor storms induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection are assigned to the following three categories.

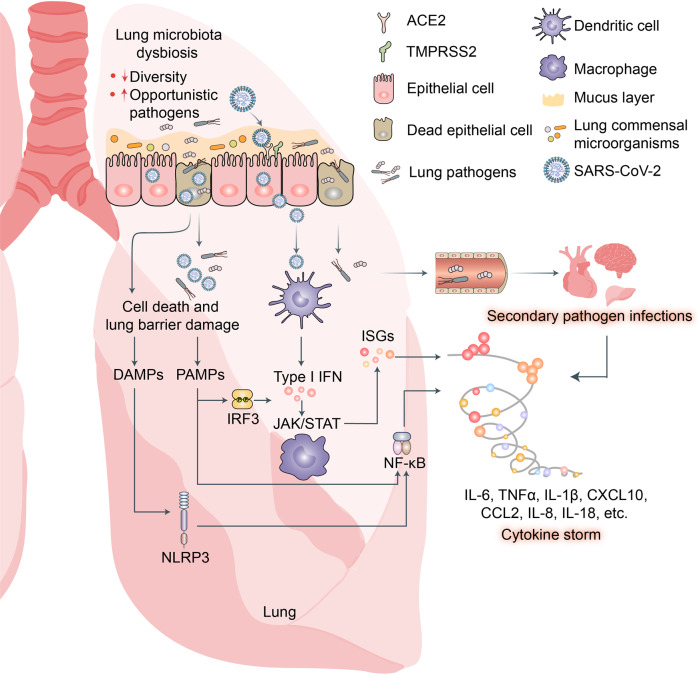

SARS-CoV-2 invades epidermal cells by binding the cell-surface receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2, hijacks host cells, and undergoes self-replication. After large numbers of viruses are produced and released from the epithelial cells, innate lymphocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DC) recognize and bind viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). These PRRs induce the expression of proinflammatory factors, IFNs, and numerous IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Fig. 3).118,119

Cells killed by SARS-CoV-2 infection release multiple danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that activate the RLRs and NLRs and, by extension, promote the expression of various proinflammatory factors.118,120

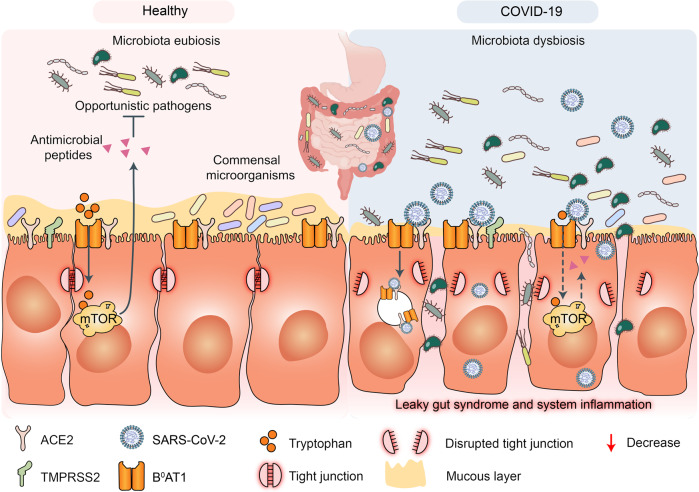

SARS-CoV-2 infection disrupts respiratory and gastrointestinal microbiota eubiosis by decreasing the proportions of probiotics and increasing the abundance of opportunistic pathogens. It damages the respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelial cell mucosal layers.121,122 It also destroys the tight junctions (TJs) between epidermal cells (Fig. 4).123 These vital physical barriers prevent opportunistic pathogen invasion.124–127 In their absence, opportunistic pathogens may enter circulation and cause systemic inflammation and infection. The sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter B0AT1 or SLC6A19 may also be implicated in the disruption of the foregoing physical barriers and/or homeostasis by SARS-CoV-2 infection.128 B0AT1 is also a molecular ACE2 chaperone.129 ACE2 was required for B0AT1 expression on the luminal surfaces of murine intestinal epithelial cells.130,131 B0AT1 mediates neutral amino acid uptake by the luminal surfaces of intestinal epithelial cells.132 B0AT1 substrates such as tryptophan and glutamine activate the release of antimicrobial peptides, promote TJ formation, downregulate lymphoid proinflammatory cytokines, and modulate mucosal cell autophagy via mTOR signaling.133,134 As ACE2 is a molecular B0AT1 chaperone, both molecules may be co-internalized during SARS-CoV-2 infection and the net amount of B0AT1 on the cell membrane surface may decrease. A recent study corroborated this hypothesis.135 Cryoelectron microscopy was used to examine the ultrastructures of the ACE2-B0AT1 complex as well as another one involving the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD). The analysis disclosed that the ACE2-B0AT1 complex exists as a heterodimer and the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S1) may interact with it.135 SARS-CoV-2-induced B0AT1 downregulation on the luminal surfaces of intestinal epithelial cells might contribute to microbiota dysbiosis which, in turn, promotes pathogen invasion and ultimately facilitates cytokine storms and COVID-19 exacerbation.134

Fig. 3.

Potential mechanisms of cytokine storm and secondary pathogen infections resulting from lung microbiota dysbiosis in patients with COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 infection disrupts lung microbiota eubiosis. Increased abundance of opportunistic pathogens may intensify lung cytokine storm and cause secondary pathogen infections in patients with COVID-19. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) released from invading opportunistic pathogens may be recognized by host innate lymphocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) via pattern recognition receptors (PRR) including Toll-like receptors (TLRs), RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), and NOD-like receptors (NLRs). These induce expression of proinflammatory factors via NF-κB signaling, interferons via IRF3 signaling, and numerous interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) via JAK/STAT signaling. Excess cytokines may exacerbate COVID-19 symptoms

Fig. 4.

Potential mechanisms of cytokine storm and secondary pathogen infections resulting from gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with COVID-19. Gut microbiota are also disrupted by SARS-CoV-2 infection which potentially triggers cytokine storm and secondary pathogen infections. B0AT1 mediates neutral amino acid uptake by luminal surfaces of intestinal epithelial cells. It is also a molecular ACE2 chaperone. B0AT1 substrates such as tryptophan and glutamine activate antimicrobial peptide release, promote tight junction (TJ) formation, downregulate lymphoid proinflammatory cytokines, and modulate mucosal cell autophagy via mTOR signaling. As ACE2 is a molecular B0AT1 chaperone, ACE2-associated B0AT1 may be internalized during SARS-CoV-2 infection, decrease B0AT1 on cell membranes, promote gut opportunistic pathogen invasion, facilitate cytokine storms, and exacerbate COVID-19

Gut commensal-derived metabolites and components modulate lung antiviral immune responses via the gut–lung axis

Gut microbiota metabolites are small molecules produced as intermediate or end products of gut microbial metabolism. They are derived either from the bacterial metabolism of dietary substrates or directly from the bacteria themselves.136 Gut microbiota-derived metabolites are the main mediators of gut microbiota-host interactions that influence host immunity. Hence, we will discuss the potential mechanisms by which gut microbiota-derived metabolites modulate the host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Host defense in the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection

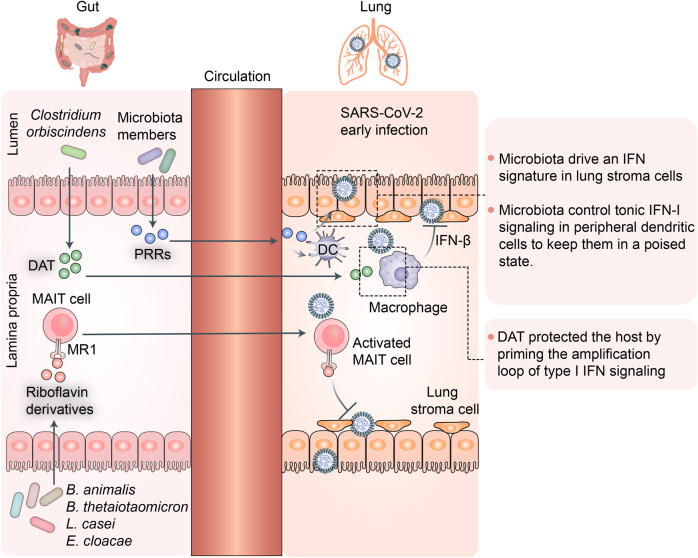

Mucosal-associated T cells (MAIT) constitute an evolutionarily conserved T-cell subset with innate functions resembling those of innate natural killer T cells (iNKT) cells.137 They are localized mainly to the spleen, lymph nodes, and liver. Nevertheless, they may also inhabit barrier tissues such as the lung, skin, and gut.138 They respond to pathogens via restrictive major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-related protein-1 (MR1)-mediated recognition of riboflavin derivatives produced by gut microbiota such as Bifidobacterium animalis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Lactobacillus casei, and Enterobacter cloacae.139,140 These microbially-derived signals affect all stages of MAIT cell biology including intrathymic development, peripheral expansion, and organ function.141,142 In tissues, MAIT cells integrate multiple signals and display effector functions associated with defense against infectious pathogens.143 A recent study showed that MAIT cells are highly involved in the host immune response against COVID-19.144 MAIT cells participate in both local and systemic immune responses in the airways during the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection. They are recruited by proinflammatory signals from the blood into the airways and rapidly promote an innate immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Gut commensal-derived metabolites or components potentially promote lung antiviral immune responses via gut–lung axis during the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut microbiota such as Bifidobacterium animalis, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Lactobacillus casei, and Enterobacter cloacae generate riboflavin derivatives that activate mucosal-associated T cells (MAIT) via restrictive major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-related protein-1 (MR1)-mediated recognition. Activated gut MAIT cells may participate in lung antiviral immune responses via gut–lung axis during early stages of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Deaminotyrosine (DAT) generated by gut bacterium Clostridium orbiscindens may protect host from viral infection by initiating amplification loop of type I interferon (IFN) signaling. Microbiota-derived components are required to program DCs during steady state so they can rapidly initiate immune responses to pathogens. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites and components may play vital roles in inhibiting early SARS-CoV-2 infection

Deaminotyrosine (DAT) is a bacterial metabolite derived from flavonoids. It was recently demonstrated that DAT protects the host from influenza infection by initiating a type I interferon (IFN) signaling amplification loop.145 The authors used a reporter cell line harboring multiple type I IFN response elements to screen a library of 84 microbe-associated metabolites and found that DAT significantly affected IFN signaling. Mice administered DAT after influenza infection exhibited reduced mortality, lower viral gene expression, and decreased proportions of apoptotic cells in their airways. The authors analyzed changes in fecal and serum DAT content in antibiotic-treated mice and confirmed that their gut microbiota produced this compound. The researchers also reported that the human gut bacterium Clostridium orbiscindens degrades flavonoids to DAT. Gut microbiota-derived components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) also help protect lungs from viral infections.146 Recent evidence from Schaupp et al. suggested that microbiota-derived components are required to program dendritic cells (DCs) in steady-state so that they rapidly respond to pathogens and initiate immune responses against them.147 Another study showed that gut microbiota-driven tonic IFN signals in lung stromal cells protect the host against influenza virus infection.148 SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus are similar in many ways. Thus, gut microbiota-derived metabolites and components might help inhibit early SARS-CoV-2 infection.149

Anti-inflammation

Proinflammatory cytokine storms caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection are associated with severe disease and high mortality rates. Several drugs suppressing or attenuating proinflammatory cytokine storms have been administered in the clinical treatment of severe or critical COVID-19 patients.150,151 Siltuximab is a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-6R.152 Numerous studies showed that various microbial metabolites inhibit inflammation. Therefore, in this section, we will discuss the putative mechanisms by which these substances suppress COVID-19-related inflammation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Anti-inflammatory immunomodulation by gut microbiota-derived metabolites and components. Left to right: polysaccharide A (PSA) capsular component of gut commensal Bacteroides fragilis can be transported to gut lamina propria via autophagy-related protein 16-like 1 (ATG16L1) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2)-dependent autophagy. PSA signals promote FOXP3 + regulatory T-cell (Treg) proliferation and IL-10 production and induce an anti-inflammatory state. Vitamin A or retinoic acid (RA) derived from gut commensal Bifidobacterium infantis upregulates Aldh1a2 encoding retinal dehydrogenase 2 in DCs. Aldh1a2-expressing DCs produce high levels of RA which collaborates with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) to promote naive T cell differentiation into FOXP3 + Treg cells and inhibit inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut microbiota may produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) acetate, propionate, and butyrate to inhibit inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Butyrate promotes M2-like macrophage polarization and anti-inflammatory activity by upregulating arginase 1 (ARG1), suppressing tumor necrosis factor (TNF) production, and downregulating Nos2, Il6, and Il12b. Butyrate inhibits histone deacetylases, increases transcription at Foxp3 promoter and related enhancer sites in naive T cells, and promotes naive T cell differentiation into Treg cells. Propionate activates GPR43 on Treg cells, thereby enhancing their proliferation. Acetate promotes anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production in B cells, thereby inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Microbiota members induce CX3CR1 + macrophages that inhibit T helper 1 (TH1) and promote Treg cell responses. Cell-surface β-glucan/galactan (CSGG) polysaccharide produced by Bifidobacterium bifidum may induce Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell generation and inhibit inflammation caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut commensals such as Helicobacter spp. and Clostridium ramosum induce RORγt expression in Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, thereby suppressing TH1, TH2, and TH17 cell-type inflammatory responses

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are produced by various bacterial groups. They include acetate (50–70%; formed by many bacterial taxa), propionate (10–20%; synthesized by Bacteroidetes and certain Firmicutes), and butyrate (10–40%; generated by a few Clostridia).153 SCFAs influence immune responses in the gut and those associated with peripheral circulation and distal body sites154–158 A recent study by Kim et al. found that the SCFAs produced by microbiota enhanced B cell metabolism and gene expression and supported optimal homeostatic and pathogen-specific antibody responses.159 SCFAs have these effects on the B cells in the gut and systemic tissues. Therefore, SCFAs derived from gut microbiota may promote anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production in B cells and inhibit COVID-19 development. Another study revealed that the gut microbiome of patients with COVID-19 presented with impaired SCFA capacity even after disease resolution.160,161 Thus, there may be a direct link between the severity of COVID-19 infection and persistent impairment of gut microbiota metabolism.

SCFAs also inhibit inflammation by modulating various immunocytes. Butyrate promotes M2-like macrophage polarization and, by extension, anti-inflammatory activity by upregulating arginase 1 (ARG1) and ultimately downregulating TNF, Nos2, IL-6, and IL-12b.162 Regulatory T cells (Treg cells) comprise a T-cell subset with significant immunosuppressive effects and the capacity to express Foxp3, CD25, and CD4. A variety of anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted from Treg cells can inhibit auto-inflammatory responses, and prevent pathological immune responses from causing tissue damage.163 Defective or absent Treg cell function may result in inflammatory disease.164–166 Butyrate can promote the differentiation of naive T cells into Treg cells by inhibiting histone deacetylase or increasing the transcription of Foxp3 promoter in naive T cells.155,157 Propionate activates GPR43 on Treg cells and enhances their proliferation.167 Other microbiota-derived metabolites and components also modulate Treg cells.

Bifidobacterium infantis-derived vitamin A or retinoic acid (RA) upregulates Aldh1a2 encoding retinal dehydrogenase 2 in DCs.168–170 Aldh1a2-expressing DCs produce high levels of RA and this substance collaborates with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) to promote naive T cell differentiation into FOXP3+ Treg cells.168,169,171 The capsular component polysaccharide A (PSA) of the gut commensal Bacteroides fragilis can be transported to the gut lamina propria via autophagy-related protein 16-like 1 (ATG16L1) and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2)-dependent autophagy pathway.172–174 Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) on FOXP3+ Treg cells recognize PSA signals which, in turn, induce FOXP3+ Treg cell proliferation, IL-10 production, and an anti-inflammatory state.175–177 Cell-surface β-glucan/galactan (CSGG) polysaccharide produced by Bifidobacterium bifidum promotes Foxp3+ Treg cell generation.178 Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma t (RORγt; a nuclear hormone receptor) may induce proinflammatory T helper 17 (TH17) cell differentiation.179 Recent studies showed that certain gut commensals such as Helicobacter spp. and Clostridium ramosum can induce RORγt expression in Foxp3+ Treg cells.180,181 RORγt+ Foxp3+ Treg cells downregulate TH1-, TH2-, and TH17 cell-type immune responses.180–182

Various gut commensal-derived metabolites and components such as vitamins, carbohydrates, amino acid derivatives, and glycolipids have been proved to modulate multiple host immunocyte subsets by different mechanisms. The immunomodulatory effects of gut commensals are potential targets for the design and administration of SARS-CoV-2 prophylaxes and therapies.

Targeting microbiota as an auxiliary for COVID-19 prevention and treatment

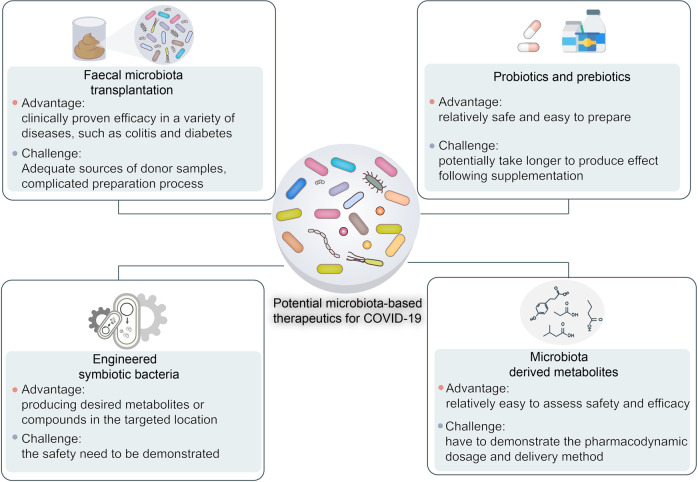

Gut microbiota are vital to immunomodulation. Thus, microbiota-based therapies such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), probiotics, and prebiotics have been used in the clinical treatment of various human diseases such as diabetes, obesity, cancers, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and certain viral infections.183 Recent studies have manipulated gut microbiota to treat COVID-19 and its complications.184–190 Here, we review and discuss putative microbiota-based COVID-19 therapies (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Potential microbiota-based COVID-19 therapies include fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), probiotics and prebiotics, engineered symbiotic bacteria, and microbiota-derived metabolites

In FMT, feces or complex microbial communities derived from in vitro culture or purification of fecal material from a healthy donor are inoculated into the intestinal tract of a patient. FMT has demonstrated efficacy against colitis, diabetes, and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection.191–194 Recently, a registered clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier No. NCT04824222) attempted to validate the efficacy of FMT as an immunomodulatory risk reducer in COVID-19 disease progression associated with escalating cytokine storms and inflammation. The control group is administered standard pharmacological treatments while the experimental group is also orally administered FMT in the form of 30–50 dose-in, double-cover, gastro-resistant, enteric-release frozen 60-g capsules.195 A main outcome measure is the incidence of adverse events in the safety pilot group up to day 30 after administration. Another outcome metric is the percentage of patients in the study and control groups requiring escalation of non-invasive oxygen therapy modalities such as increasing FiO2, administering high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNOT), continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), or invasive ventilation, ventilators, and/or ICU hospitalization corresponding to grades 5–7 disease exacerbation on the COVID-19 performance status scale. This trial is still in progress. Nevertheless, considering the vital roles of gut microbiota in immune regulation, we believe that FMT is a possible therapeutic option for suppressing COVID-19-induced cytokine storms and inflammation.

Supplementation with microbiota-targeted substrates (prebiotics) such as specific dietary fibers and/or direct transfer of one or several specific beneficial microbiota (probiotics) are promising COVID-19 treatment approaches that modulate the gut microbiota.186,196 Treatment with probiotics and/or prebiotics is relatively safer and easier to prepare and administer than FMT. The National Health Commission of China has recommended the clinical administration of probiotics to patients with severe COVID-19 for the purposes of restoring and maintaining gut microflora balance and preventing secondary infection. Indeed, numerous clinical trials are validating the efficacy of probiotics and/or prebiotics at reducing COVID-19 duration and symptoms (Table 1). One clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier No. NCT05043376) is investigating the efficacy of the probiotic Streptococcus salivarius K12 (BLIS K12)197 in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Investigators in a phase II randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier No. NCT05175833) are assessing the efficacy of BLIS K12 and Lactobacillus brevis CD2 in the prevention of secondary bacterial pneumonia in patients with severe COVID-19. Another randomized trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier No. NCT04399252) at Duke University Hospital is evaluating the efficacy of the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG at preventing COVID-19 transmission and symptom development in exposed household contacts. None of the foregoing clinical trials has yet published the results. However, it has already been empirically demonstrated that certain probiotic stains have antiviral activity against other coronaviruses. Therefore, probiotics could potentially be used in the prevention and/or adjuvant treatment of COVID-19.

Table 1.

Examples of completed clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of probiotics or prebiotics in the treatment of COVID-19

| Title | Interventions | Population | Locations | Clinical trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy of Probiotics in Reducing Duration and Symptoms of COVID-19 |

• Dietary supplement: probiotics (2 strains 10 × 109 UFC) • Dietary supplement: placebo (potato starch and magnesium stearate) |

Enrollment: 17 | • CIUSSS de L’Estrie-CHUS Hospital, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada | NCT04621071 |

| Study to Evaluate the Effect of a Probiotic in COVID-19 |

• Dietary supplement: probiotic • Dietary supplement: placebo |

Enrollment: 41 |

• Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó, Elche, Alicante, Spain • Hospital Universitario de Torrevieja, Torrevieja, Alicante, Spain |

NCT04390477 |

| Efficacy of Intranasal Probiotic Treatment to Reduce Severity of Symptoms in COVID-19 Infection |

• Dietary supplement: probiotic • Dietary supplement: saline solution |

Enrollment: 23 | • Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), Montreal, Quebec, Canada | NCT04458519 |

| The Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Response After COVID-19 |

• Dietary supplement: L. reuteri DSM 17938 + vitamin D • Dietary supplement: placebo + vitamin D |

Enrollment: 161 | • Örebro University, Örebro, Örebro Län, Sweden | NCT04734886 |

|

Study to Investigate the Treatment Benefits of Probiotic Streptococcus Salivarius K12 for Hospitalized Patients (Non-ICU) With COVID-19 |

• Drug: standard of care • Dietary supplement: BLIS K12 |

Enrollment: 50 | • King Edward Medical University Teaching Hospital, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan | NCT05043376 |

|

Oral Probiotics and Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia in Severe COVID-19 |

• Combination product: oral probiotics • Other: oral placebo |

Enrollment: 70 | • University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, RS, Brazil | NCT05175833 |

|

Live Microbes to Boost Anti-Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Immunity Clinical Trial |

• Dietary supplement: OL-1, standard dose • Dietary supplement: OL-1, high dose • Dietary supplement: placebo |

Enrollment: 54 | • Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States | NCT04847349 |

| Efficacy of Probiotics in the Treatment of Hospitalized Patients With Novel Coronavirus Infection |

• Dietary supplement: probiotic • Dietary supplement: placebo |

Enrollment: 200 | • I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russian Federation | NCT04854941 |

| Efficacy of L. plantarum and P. acidilactici in Adults With SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 |

• Dietary supplement: probiotic • Dietary supplement: placebo |

Enrollment: 300 | • Hospital General Dr. Manuel Gea Gonzalez, Mexico city, Mexico | NCT04517422 |

|

Effect of Lactobacillus on the Microbiome of Household Contacts Exposed to COVID-19 |

• Dietary supplement: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG • Dietary Supplement: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG placebo |

Enrollment: 182 | • Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, United States | NCT04399252 |

|

Effect of a NSS to Reduce Complications in Patients With Covid-19 and Comorbidities in Stage III |

• Dietary supplement: nutritional support system (NSS) • Other: conventional nutritional support designed by hospital nutritionists |

Enrollment: 80 | • ISSEMYM “Arturo Montiel Rojas” Medical Center, Toluca de Lerdo, Mexico State, Mexico | NCT04507867 |

All of the data from https://clinicaltrials.gov/

Advances in synthetic biology and gene manipulation are facilitating and realizing the design of microorganisms based on therapeutic requirements for COVID-19. We can now engineer symbiotic bacteria with desired functions, the ability to produce the required metabolites, and the capacity to target the correct locations in the host. A Lactococcus lactis strain was engineered to express and secrete the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 to treat colitis.198 The biosafety of this strain was ensured by making it require exogenous thymidine for survival and IL-10 production.199 The cytokine storms caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection have a close relationship with COVID-19 severity and mortality. Hence, the design and application of similarly engineered strains to produce anti-inflammatory metabolites in the lungs and suppress proinflammatory storms could culminate in a promising COVID-19 treatment. While much further clinical study is required to validate the safety and efficacy of this technology. Direct supplementation of beneficial microbiota-derived metabolites such as SCFAs are also promising candidates for COVID-19 treatment.

Emerging evidence from interventional studies and animal models suggests that the microbiota plays a crucial role in antibody responses to vaccination.200–205 For example, antibiotic-treated and germ-free mice had reduced antibody responses to the seasonal influenza vaccine.206 Therefore, in addition to the COVID-19 treatment, considering microbiota as a vital factor modulating immune responses to vaccination, microbiota-targeted interventions are a promising way to optimize the COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness. However, so for, relatively few studies have evaluated the effects of the microbiota on immune responses to COVID-19 vaccination and further work is required in this area.

Conclusions and perspectives

Symptoms associated with the initial phase of COVID-19 include dry cough, shortness of breath, vomiting, and diarrhea.15,20,207 The respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts are the primary habitats of human microbiota and targets for SARS-CoV-2 infection as they express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 at high levels.44,46,208–212 There is growing evidence that the substantial perturbation of these microbiota during COVID-19 is associated with disease severity and mortality and post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS).26–28,110,160,213 Microbiota are powerful immunomodulatory factors in human health and disease.214–217 Hence, targeting microbiota manipulation is a promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 and PACS. Numerous clinical trials are evaluating the efficacy of adjuvant therapy with probiotics as well as other microbiota-based treatments. However, the outcomes of these clinical trials have not yet been published. Additional clinical data are required to validate the safety and efficacy of microbiota-based therapies for patients with COVID-19 or PACS.

The SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant has recently and rapidly spread worldwide.218 Notably, the Omicron variant is not a single strain, but evolved into three lineages: BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3.219 BA.1 was once the most widely prevalent strain in the world; however, BA.2 is suggested to be more transmissible than the BA.1 and BA.2 is gradually replacing BA.1 in several countries, such as Denmark, Nepal, and the Philippines.220 The transmissibility of BA.3 is very limited, with very few cases, at most a few hundred cases. Certain studies proposed that the omicron variant can evade infection- and vaccination-induced antibodies and exacerbate existing public health risks.221–227 In contrast, other studies demonstrated comparatively lower hospitalization rates associated with the omicron variant than the wild type SARS-CoV-2.228–230 However, the differences among the omicron and wild type strains in terms of their relative impact on host microbiota alterations are unknown. Future investigations might help develop microbiota-based therapeutics customized for omicron variant infections.

Not only various intrinsic host factors (such as age, sex, genetics, and comorbidities), but also extrinsic factors (such as rural versus urban location, geographical location, season, and toxins) have been shown to influence the composition of the microbiota.231 Moreover, microbiota composition varies widely among individuals and populations.232 They also greatly differ in terms of their SARS-CoV-2 symptoms. Cases may range from asymptomatic to acute pneumonia.17 However, there is little data available on the associations among microbiota composition and coronavirus susceptibility. Thus, clarification of the relationships between SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and microbiota composition may facilitate the design and deployment of prophylactic and therapeutic measures against the new SARS-CoV-2 strains. It is clear that microbiota are strongly implicated in host immune responses to various diseases including COVID-19. Nevertheless, it remains to be determined whether microbiota-based therapeutics influence COVID-19 outcome. This research focus should be prioritized as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to be severe in certain parts of the world.

Acknowledgements

We would like to apologize to those researchers whose related work we were not able to cite in this review. This work was supported by a special program from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2021YFA101000), the Chinese National Natural Science Funds (U20A20393, U20A201376, 31925013, 3212500161, 82041009, 31871405, 31701234, 81902947, 82041009, 31671457, 31571460, and 91753139), Jiangsu Provincial Distinguished Young Scholars award (BK20180043), the Key Project of University Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (19KJA550003), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LBY21H060001 and LGF19H180007), Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Program (2020RC115), and A project Funded by the Priority Acadamic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX17_2036).

Author contributions

B.W. conceived and drafted the manuscript. B.W. drew the figures. Lei Zhang discussed the concepts of the manuscript. Long Zhang and F.Z. provided valuable discussion and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Bin Wang, Lei Zhang

Contributor Information

Fangfang Zhou, Email: zhoufangfang@suda.edu.cn.

Long Zhang, Email: L_Zhang@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature486, 207–214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Qin J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Round, J. L. & Palm, N. W. Causal effects of the microbiota on immune-mediated diseases. Sci Immunol. 3, eaao1603 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wampach L, et al. Colonization and succession within the human gut microbiome by archaea, bacteria, and microeukaryotes during the first year of life. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:738. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wypych TP, Wickramasinghe LC, Marsland BJ. The influence of the microbiome on respiratory health. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:1279–1290. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickson RP, Erb-Downward JR, Martinez FJ, Huffnagle GB. The microbiome and the respiratory tract. Annu Rev. Physiol. 2016;78:481–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pattaroni C, et al. Early-life formation of the microbial and immunological environment of the human airways. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch SV, Pedersen O. The human intestinal microbiome in health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:2369–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belkaid Y, Harrison OJ. Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity. 2017;46:562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016;16:341–352. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiota in adaptive immune homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2016;535:75–84. doi: 10.1038/nature18848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020;30:492–506. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0332-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ansaldo E, Farley TK, Belkaid Y. Control of immunity by the microbiota. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021;39:449–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-093019-112348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romagnoli S, Peris A, De Gaudio AR, Geppetti P. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: from the bench to the bedside. Physiol. Rev. 2020;100:1455–1466. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan WJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauer SA, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiersinga WJ, et al. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020;324:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Morales AJ, et al. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;34:101623. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao R, et al. Manifestations and prognosis of gastrointestinal and liver involvement in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:667–678. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin X, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69:1002–1009. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sulaiman I, et al. Microbial signatures in the lower airways of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients associated with poor clinical outcome. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:1245–1258. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloréns-Rico V, et al. Clinical practices underlie COVID-19 patient respiratory microbiome composition and its interactions with the host. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6243. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu R, et al. Temporal association between human upper respiratory and gut bacterial microbiomes during the course of COVID-19 in adults. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:240. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-01796-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuo T, et al. Alterations in fecal fungal microbiome of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization until discharge. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1302–1310. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuo T, et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:944–955. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuo T, et al. Temporal landscape of human gut RNA and DNA virome in SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity. Microbiome. 2021;9:91. doi: 10.1186/s40168-021-01008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeoh YK, et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021;70:698–706. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox MJ, Loman N, Bogaert D, O’Grady J. Co-infections: potentially lethal and unexplored in COVID-19. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e11. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu N, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu R, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu A, et al. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:325–328. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:562–569. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shang J, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lan J, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wrapp D, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ou T, et al. Hydroxychloroquine-mediated inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry is attenuated by TMPRSS2. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009212. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q, et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lv J, et al. Distinct uptake, amplification, and release of SARS-CoV-2 by M1 and M2 alveolar macrophages. Cell Discov. 2021;7:24. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sungnak W, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat. Med. 2020;26:681–687. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou X, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front. Med. 2020;14:185–192. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, et al. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;202:756–759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lukassen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are primarily expressed in bronchial transient secretory cells. EMBO J. 2020;39:e105114. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zang, R. et al. TMPRSS2 and TMPRSS4 promote SARS-CoV-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabc3582 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Intestinal inflammation modulates the expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and potentially overlaps with the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2-related disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:287–301. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weibel ER. Morphometry of the human lung: the state of the art after two decades. Bull. Eur. Physiopathol. Respir. 1979;15:999–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Man WH, de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Bogaert D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15:259–270. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bassis CM, et al. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio. 2015;6:e00037. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charlson ES, et al. Lung-enriched organisms and aberrant bacterial and fungal respiratory microbiota after lung transplant. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;186:536–545. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0693OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogaert D, De Groot R, Hermans PW. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4:144–154. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guo M, Tao W, Flavell RA, Zhu S. Potential intestinal infection and faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:269–283. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00416-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheung KS, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong Cohort: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin W, et al. Association between detectable SARS-COV-2 RNA in anal swabs and disease severity in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:794–802. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Y, et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat. Med. 2020;26:502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xing YH, et al. Prolonged viral shedding in feces of pediatric patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J. Microbiol Immunol. Infect. 2020;53:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu Y, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:434–435. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen Y, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the feces of COVID-19 patients. J. Med Virol. 2020;92:833–840. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiao F, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet. 2003;361:512–519. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pickard JM, Zeng MY, Caruso R, Núñez G. Gut microbiota: role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol. Rev. 2017;279:70–89. doi: 10.1111/imr.12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Budden KF, et al. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017;15:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ost KS, et al. Adaptive immunity induces mutualism between commensal eukaryotes. Nature. 2021;596:114–118. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03722-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oberfeld B, et al. SnapShot: COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:954–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin L, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69:997–1001. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papa A, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and digestive comorbidities in an Italian cohort of patients with COVID-19. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2020;24:7506–7511. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_21923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou F, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen A, et al. Are gastrointestinal symptoms specific for coronavirus 2019 infection? A prospective case-control study from the United States. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1161–1163. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ferm S, et al. Analysis of gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection in 892 patients in Queens, NY. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;18:2378–2379. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Remes-Troche JM, et al. Initial gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in 112 patients from Veracruz in Southeastern Mexico. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1179–1181. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Redd WD, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in the United States: a multicenter cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:765–767. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wan Y, et al. Enteric involvement in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 outside Wuhan. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;5:534–535. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cholankeril G, et al. High prevalence of concurrent gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2: early experience from California. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:775–777. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Díaz LA, et al. Symptom profiles and risk factors for hospitalization in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a large cohort from South America. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1148–1150. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hajifathalian K, et al. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of 2019 novel coronavirus disease in a large cohort of infected patients from New York: clinical implications. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1137–1140. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jiehao C, et al. A case series of children with 2019 novel coronavirus infection: clinical and epidemiological features. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:1547–1551. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu X, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1663–1665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fakiri KE, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of coronavirus disease 2019 in Moroccan children. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:808–810. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1958-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.de Ceano-Vivas M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in ambulatory and hospitalised Spanish children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020;105:808–809. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Children—United States, February 12-April 2, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 69, 422–426 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D. Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:187–190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang H, et al. Metatranscriptomic characterization of coronavirus disease 2019 identified a host transcriptional classifier associated with immune signaling. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:376–385. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kosmidis C, Denning DW. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2015;70:270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zuo T, et al. Gut fungal dysbiosis correlates with reduced efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3663. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06103-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Erb Downward JR, et al. Modulation of post-antibiotic bacterial community reassembly and host response by Candida albicans. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2191. doi: 10.1038/srep02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang X, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lescure FX, et al. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Arkel ALE, et al. COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;202:132–135. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1038LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Alanio A, et al. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:e48–e49. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30237-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koehler P, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2020;63:528–534. doi: 10.1111/myc.13096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Virgin HW. The virome in mammalian physiology and disease. Cell. 2014;157:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neil JA, Cadwell K. The intestinal virome and immunity. J. Immunol. 2018;201:1615–1624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shkoporov AN, et al. The human gut virome is highly diverse, stable, and individual specific. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:527–541. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259–264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang C, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397:220–232. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crook H, et al. Long covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Korompoki E, et al. Late-onset hematological complications post COVID-19: an emerging medical problem for the hematologist. Am. J. Hematol. 2022;97:119–128. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.The L. Understanding long COVID: a modern medical challenge. Lancet. 2021;398:725. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01900-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lewis D. Long COVID and kids: scientists race to find answers. Nature. 2021;595:482–483. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-01935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Leta V, et al. Parkinson’s disease and post-COVID-19 syndrome: the Parkinson’s long-COVID spectrum. Mov. Disord. 2021;36:1287–1289. doi: 10.1002/mds.28622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol. Med. 2021;27:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Naeije R, Caravita S. Phenotyping long COVID. Eur. Respir J. 2021;58:1–5. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01763-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Adeloye D, et al. The long-term sequelae of COVID-19: an international consensus on research priorities for patients with pre-existing and new-onset airways disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021;9:1467–1478. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00286-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Auwaerter PG. The race to understand post-COVID-19 conditions. Ann. Intern Med. 2021;174:1458–1459. doi: 10.7326/M21-3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nolen LT, Mukerji SS, Mejia NI. Post-acute neurological consequences of COVID-19: an unequal burden. Nat. Med. 2022;28:20–23. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Taquet M, et al. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: a 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Khunti K, Davies MJ, Kosiborod MN, Nauck MA. Long COVID - metabolic risk factors and novel therapeutic management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021;17:379–380. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00495-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.The Lancet, N. Long COVID: understanding the neurological effects. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:247. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00059-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nalbandian A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu Q, et al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut. 2022;71:544–552. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sims JT, et al. Characterization of the cytokine storm reflects hyperinflammatory endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;147:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nigrovic PA. COVID-19 cytokine storm: what is in a name? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021;80:3–5. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Caricchio R, et al. Preliminary predictive criteria for COVID-19 cytokine storm. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021;80:88–95. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bone RC. Immunologic dissonance: a continuing evolution in our understanding of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) Ann. Intern Med. 1996;125:680–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Broderick L, et al. The inflammasomes and autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2015;10:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Khanmohammadi S, Rezaei N. Role of Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:2735–2739. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:355–362. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Onofrio L, et al. Toll-like receptors and COVID-19: a two-faced story with an exciting ending. Future Sci. OA. 2020;6:Fso605. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Velikova T, et al. Gastrointestinal mucosal immunity and COVID-19. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5047–5059. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i30.5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Amorim Dos Santos J, et al. Oral mucosal lesions in a COVID-19 patient: new signs or secondary manifestations? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;97:326–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tian W, et al. Immune suppression in the early stage of COVID-19 disease. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5859. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19706-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009;1:a002584. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Walsh SV, Hopkins AM, Nusrat A. Modulation of tight junction structure and function by cytokines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2000;41:303–313. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00048-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Otani T, Furuse M. Tight junction structure and function revisited. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30:805–817. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Buckley, A. & Turner, J. R. Cell biology of tight junction barrier regulation and mucosal disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 10, a029314 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 128.Penninger JM, Grant MB, Sung JJY. The role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in modulating gut microbiota, intestinal inflammation, and coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:39–46. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kowalczuk S, et al. A protein complex in the brush-border membrane explains a Hartnup disorder allele. FASEB J. 2008;22:2880–2887. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Camargo SM, et al. Tissue-specific amino acid transporter partners ACE2 and collectrin differentially interact with hartnup mutations. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:872–882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hashimoto T, et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Verrey F, et al. Novel renal amino acid transporters. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005;67:557–572. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.153949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Perlot T, Penninger JM. ACE2 - from the renin-angiotensin system to gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]