Abstract

Poverty threatens child health. In the United States, financial strain, which encompasses income and asset poverty, is common with many complex etiologies. Even relatively successful anti-poverty programs and policies fall short of serving all families in need, endangering health. We describe a new approach to address this pervasive health problem: antipoverty medicine. Historically, medicine has viewed poverty as a social problem outside of its scope. Increasingly, health care has addressed poverty’s downstream effects, such as food and housing insecurity. However, strong evidence now shows that poverty affects biology, and thus, merits treatment as a medical problem. A new approach uses Medical-Financial Partnerships (MFPs), in which healthcare systems and financial service organizations collaborate to improve health by reducing family financial strain. MFPs help families grow assets by increasing savings, decreasing debt, and improving credit and economic opportunity while building a solid foundation for lifelong financial, physical, and mental health. We review evidence-based approaches to poverty alleviation, including conditional and unconditional cash transfers, savings vehicles, debt relief, credit repair, financial coaching, and employment assistance. We describe current national MFPs and highlight different applications of these evidence-based clinical financial interventions. Current MFP models reveal implementation opportunities and challenges, including time and space constraints, time-sensitive processes, lack of familiarity among patients and communities served, and sustainability in traditional medical settings. We conclude that pediatric health care practices can intervene upon poverty and should consider embracing antipoverty medicine as an essential part of the future of pediatric care.

Keywords: Child poverty, medical financial partnerships, social determinants of health, child health

Background

Poverty is a grave threat to child health. The child poverty rate may increase by 50% (to 21%) in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Prepandemic, 60% of Americans were without sufficient savings to cover three months of expenses.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed financial strain’s serious harm: millions of families have been unable to manage sudden loss of income without financial resources to mitigate the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Poverty causes material hardship and psychological stress. It is linked to poor health outcomes throughout the life course.3 The American Academy of Pediatrics calls for a paradigm shift whereby health care providers address childhood poverty directly within their clinical practices to improve child health.4,5 Thus, pediatric clinicians are already beginning to adopt the rationale and tools of a new clinical paradigm, which we term antipoverty medicine, as an upstream approach to address poverty and its harmful health effects.6

Antipoverty Medicine: A Frameshift to Address Disparities due to Poverty

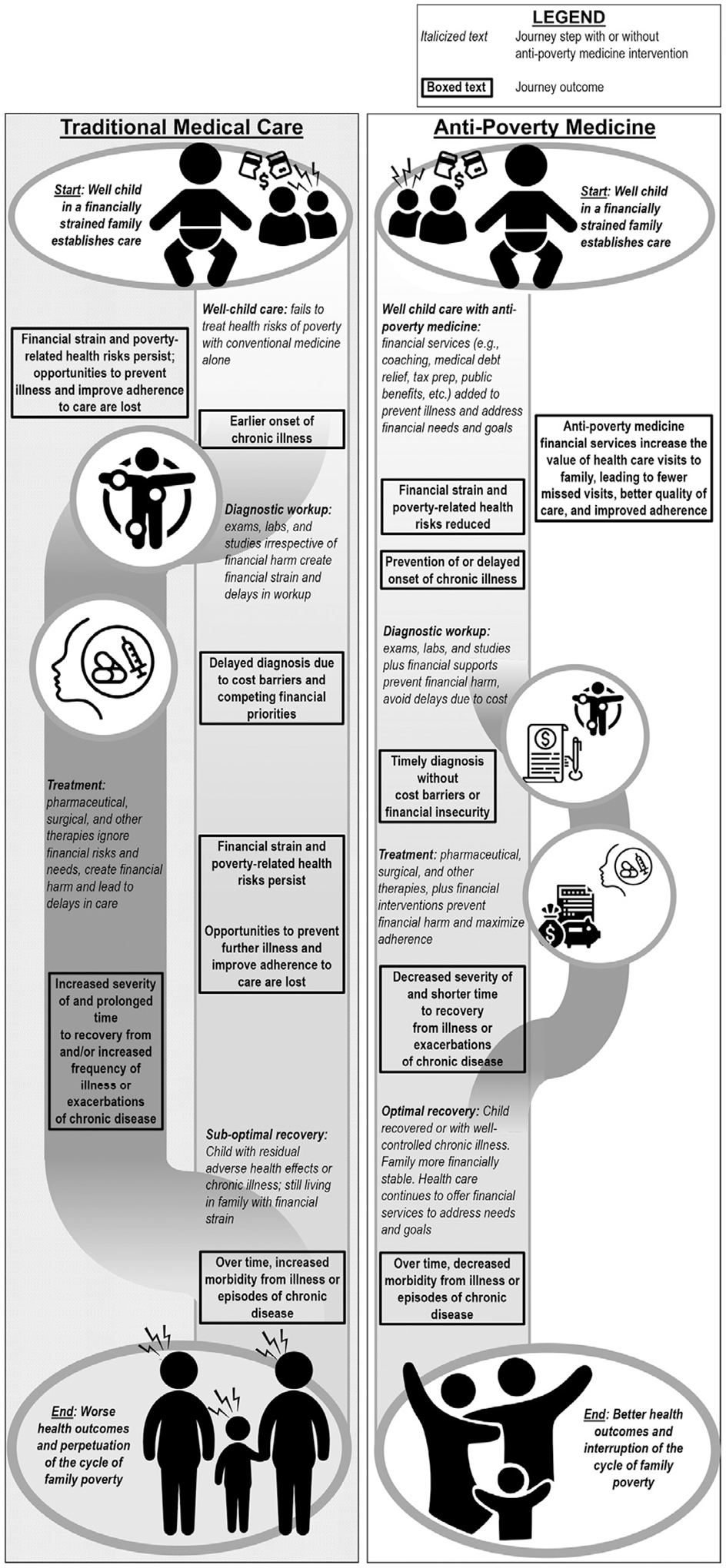

Antipoverty medicine is a concept that shifts health care’s approach by recognizing poverty as a key driver of morbidity and mortality requiring “treatment,” similar to the management of other health risks (Fig. 1). Medical Financial Partnerships (MFPs), defined as cross-sector collaborations in which health care systems and financial service organizations work together to improve health by reducing patient financial stress, offer tools for practitioners of antipoverty medicine.”5

Figure 1.

Health care’s new model: Antipoverty medicine.

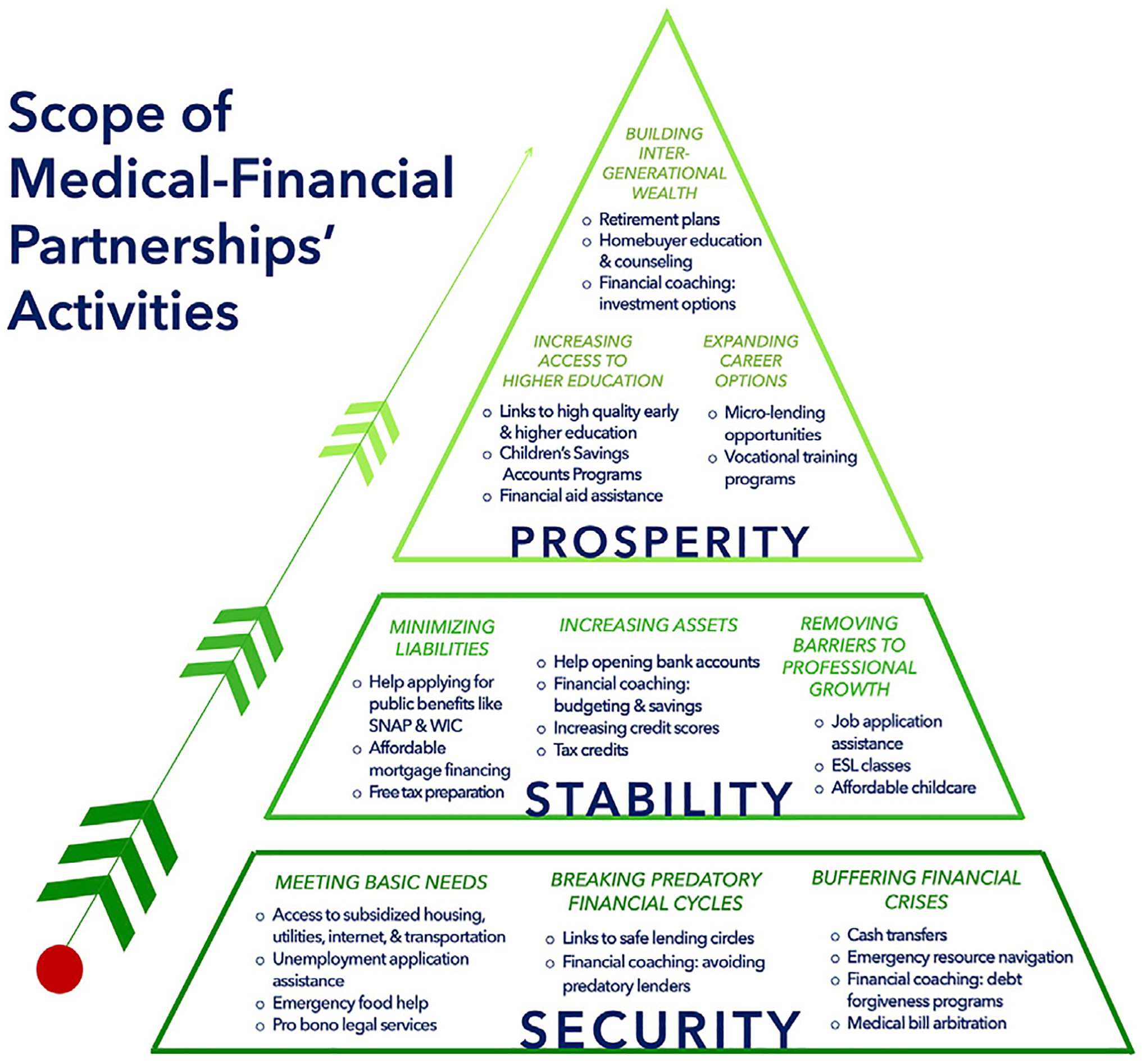

MFPs hold great promise to improve child health. A strength of MFPs is their connection with and, often, colocation within trusted pediatric health care settings accessed by the vast majority of low-income families. MFPs help families grow assets by providing resources, knowledge, and skills to reduce expenses, increase income, decrease debt, and/or increase savings to build a solid foundation for lifelong health (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Scope of medical-financial partnerships’ activities.

Antipoverty Medicine Is Needed

Financial strain, pervasive in the United States, encompasses income poverty (ie, not earning enough to get by), asset poverty (ie, low or negative net worth), and subjective stress from finances regardless of objective economic position.7 In the US, one-third of adults report substantial financial strain, over half of families are income or asset poor, and young adults hold less wealth than prior generations at this stage of life, particularly those with a college degree.7,8 Economic policies systematically excluding people of color strongly influence risk of financial strain. Different contributors to financial strain (income, savings, debt, credit, intergenerational finances) link to health outcomes and MFPs may address these financial domains.5

US antipoverty policies can be effective, but they are limited.3 Unconditional cash transfer programs (social security income, tax credits) and conditional cash transfer programs (child care and housing vouchers, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or SNAP) serve as supplements to permanent solutions such as accessing work training, increasing the minimum wage, and eliminating immigration-related welfare restrictions. All of these programs lift families from poverty.3 However, they do not fully meet families’ needs. For example, disposable diapers, a significant expense for low-income families, are not covered by federal assistance programs, leading to financial strain, trade-offs with other basic necessities, and some families leaving diapers on their children for unhealthy amounts of time.9

Additionally, some programs are difficult to access given onerous enrollment requirements.2, 10 Further, available financial capability services, like financial coaching and child development accounts (ie, savings accounts), often fail to reach those who could benefit.5 Integration into health care makes antipoverty programs more scalable and accessible.

Impact of Alleviating Poverty on Child Health

The effectiveness of poverty alleviation and financial services is well established.3,4 Evidence-based approaches include: (1) conditional cash transfers, including means-tested benefits access (ie, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant, and Children or WIC; SNAP); (2) unconditional cash transfers, such as tax credits (Earned Income Tax Credit or EITC; Child Tax Credit or CTC) and Social Security Income; (3) savings vehicles, including tax-advantaged and those designated for specific uses, such as emergencies or higher education; (4) debt relief; (5) credit repair; (6) employment assistance; and (7) financial coaching to connect and navigate these services in alignment with families’ financial needs and goals. Financial services delivered through MFPs, in particular, have the potential to impact economic mobility and family health.5

The argument for poverty alleviation is supported by data that suggests in states with higher expenditures on social services and public health measures significantly improve population health outcomes as measured by a lower percentage of adults with obesity, asthma, mentally unhealthy days or days with activity limitations, and lower mortality rates from diabetes, acute myocardial infarction, and lung cancer.11 Higher incomes are independently associated with longer life expectancy; the richest 1% of women and men live 10 and 14 years, respectively, longer than the poorest 1% in the US.12 Poverty reduction through cash transfers like the EITC, a federal, refundable tax credit supplementing income for low-to-moderate income workers, is associated with improved home environment quality for children, child development, and maternal mental health; decreased rates of smoking; lower stress biomarkers; increased prenatal care.13 Evidence of a dose-dependent effect exists. As EITC payment increases, infant outcome measures, such as term birth and breast-feeding rates, significantly improve and have been shown to mitigate perinatal disparities by disproportionately decreasing LBW births in Black mothers.14

Similarly, a cross sectional survey at 5 urban hospitals of families with children <3 years old receiving support from Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) demonstrated that children are less likely to be underweight (mean z-score weight/age 0.076 vs −0.033, p=0.01) and have reduced risk of hospitalization compared to eligible children not enrolled (1.00 vs 1.32, P = .05).15 When SNAP benefits are reduced both caregivers and children experience increased odds of fair/poor health.16 These effects likely occur through increased ability to afford basic needs, decreased stress, increased self-care, and increased access to medical care.11

Beyond public benefits programs, financial services focused on increasing savings, decreasing debt, and improving credit scores also improve financial well-being, both within MFPs and on their own. One rigorous study of financial coaching, a service helping consumers achieve self-defined financial goals, found participants increased savings (average savings account balance for intervention group $1187 +/− $1021 (90% CI) higher than control), improved credit scores (intervention group scores increased 21+/−13 points), and decreased debt (intervention group reduction of debt of $10,644 +/− $7891), including medical debt.17 Similarly, credit-building initiatives, such as lending circles, decrease debt and improve credit scores.18 Preliminary data from an RCT of 181 mothers receiving financial coaching for 1 year found decreased financial strain.19 In a qualitative study of adult caregivers and adolescents visiting an academic-based pediatric clinic, an MFP providing embedded employment services was highly desired.20

Evidence is promising on the health impact of financial services MFPs often deploy. A rigorous study of tax-protected children’s 529 college savings accounts found improved social-emotional development for young children in low-income families, decreased punitive parenting scores and decreased rates of maternal depression.21–23 An observational cohort of 30 women receiving financial coaching showed participants, from baseline to year 2 postintervention, had increased income ($8,026, P = .03), a trend toward decreased consumption of fast food (1.5 vs 2.2 visits per week, P = .07), improved physical and psychological health-related quality of life.24 Studies on credit-building initiatives also show improvements in overall self-reported health.25 While few experimental studies of MFPs exist, a randomized trial of an MFP delivering wraparound financial and social services for housing-unstable families with medical complexity improved child health status and parent mental health, consistent with preliminary evidence from a community-based randomized trial of financial coaching.26

MFPs Offer a Range of Financial Services in Clinical Settings

For health care practices interested in moving beyond social needs screening to address poverty directly through financially-focused interventions, multiple MFP models exist. An MFP builds an intentional connection between health care delivery and asset building opportunities and may include a limited or broader range of services, depending on what is available to each clinic. MFPs range from leveraging clinical resources to providing on-site financial services to building strong community partnerships and comprehensive economic ecosystems supporting families’ multidimensional financial needs. Available services (embedded or in the community) may include free tax preparation, enrollment in savings accounts, employment assistance and workforce development, financial coaching, or assistance with applying for benefits programs. Moreover, some MFPs collaborate with Medical-Legal Partnerships (MLP). MLPs are fully-embedded legal services addressing health-harming legal needs, including legal barriers to financial wellness, such as benefit or disability appeals, workplace discrimination, and family medical leave. MFPs serve a range of clients to include hospital and clinic patients, employees, and community members.

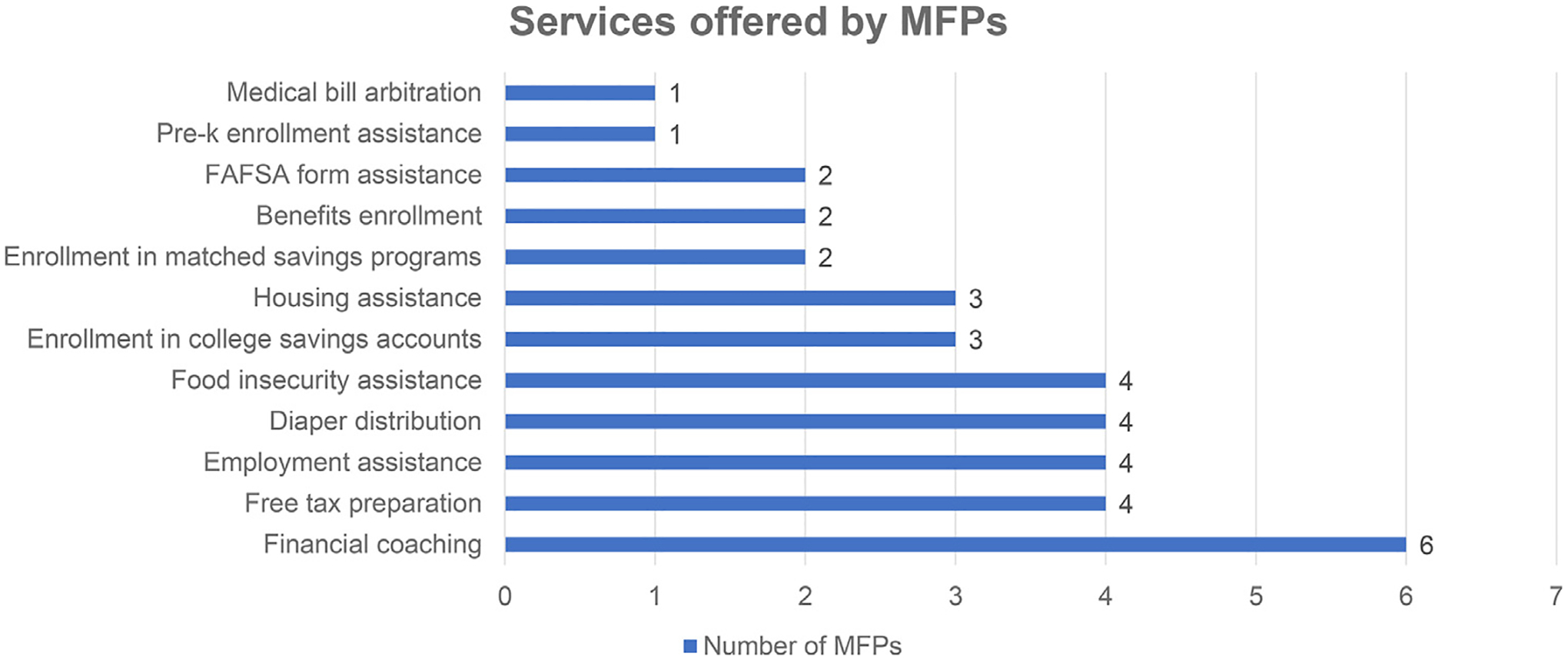

For this review, we surveyed pediatric MFPs nationally. To be considered an MFP, the program had to provide financial services (onsite or in the community) designed to directly impact financial stability as part of its health care model. Under this definition, an MFP could be a financial service (eg, tax preparation, financial coaching) or address a material need (eg, food pantry). However, to qualify as an MFP, a material resource service such as a food pantry could not focus solely on hunger alleviation but had to include referrals or education about using the resource to build financial stability. Survey questions focused on services delivered, types of clients served, and funding mechanisms. Table 1 summarizes successful MFPs. Figure 3 summarizes MFPs’ service portfolios.

Table 1.

MFPs Serving Pediatric Institutions Nationally

| MFP Name and Institution | MFP Location | Year MFP Started | Founding Sources | Population(s) Served | MFP Services Offered | Financial Coaching Services | MFP Benefits Enrollment | Total # Clients Served |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Bird | Clinic | 2020 | Grants/philanthropy, hospital/clinic | Hospital/clinic families, low income | Enrollment in savings accounts, employment assistance/workforce development, financial coaching, referral to outside community organizations, enrollment in pre-kindergarten | Credit repair, budget, debt reduction, expense management, financial literacy, banking, other savings products | 188 | |

| The Harbor UCLA Medical Financial Partnership | Clinic | 2017 | Grants/philanthropy | Hospital/clinic families | Enrollment in matched savings programs, employment assistance/workforce development, financial coaching, enrollment in benefits, housing assistance, diaper distribution, food insecurity assistance, referral to outside community organizations, medical bill arbitration | Credit repair, budget, debt reduction, expense management, financial literacy, banking, other savings products, public/nonprofit benefits, utilities assistance | SNAP, WIC, COVID economic incentive payment, social security, TANF/CalWORKS, utilities assistance, rent relief | 2500 |

| Johns Hopkins Community Connection | Clinic | 2016 | Grants/philanthropy, hospital/clinic | Hospital/clinic families, low income | Employment assistance/workforce development, enrollment in benefits, diaper distribution, food insecurity assistance, referral to outside community organizations | SNAP, WIC, COVID economic incentive payment, disability, social security | 549 | |

| Yale School of Medicine Medical Financial Partnership | Clinic | 2017 | Grants/philanthropy, hospital/clinic | Hospital/clinic families, all community members, low income | Free tax preparation (vita), referral to outside community organizations | 500 | ||

| Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families- Nationwide Children’s Hospital | Clinic, Hospital, Community Organization | 2010 | Grants/philanthropy, hospital/clinic, government, loans/interest | Hospital/clinic families, hospital/clinic employees, all community members, low income | Free tax preparation (vita), employment assistance/workforce development, financial coaching, FAFSA form assistance, housing assistance, food insecurity assistance, referral to outside community organizations, investment in community-driven projects. | Credit repair, budget, debt reduction, expense management, financial literacy, banking, other savings products | 27,772 | |

| StreetCred & Medical Tax Collaborative- Boston Medical Center | Hospital | 2016 | Grants/philanthropy, hospital/clinic, government | Hospital/clinic families, hospital/clinic employees, low income | Free tax preparation (vita), enrollment in college savings accounts, financial coaching, diaper distribution | Credit repair, budget, debt reduction, expense management, financial literacy, banking, other savings products | 1300 |

Figure 3.

Services offered by MFPs.

Recently developed MFPs include interventions offering asset-building opportunities while incentivizing health-promoting behaviors. For example, Early Bird, an MFP built by The Impact Factory at The University of Texas at Austin, offers conditional cash transfers tied to health, educational, and financial achievement, often aligned with health insurance priorities. Dollar rewards, up to $500 per child, are placed in 529 college savings accounts as families achieve milestones like physician and dentist appointment attendance, enrollment in prekindergarten, and participation in financial coaching.

Some MFPs take a place-based approach to improving health by increasing access to housing, employment, and financial services. Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families, an MFP of Nationwide Children’s Hospital, treats the neighborhood surrounding the hospital. The economically-distressed Southern Orchards neighborhood underwent extensive resuscitation through the renovation of homes, creation of outdoor spaces, and embedding employment and financial services as core community offerings.27

Another MFP strategy focuses on increasing access to pre-existing federal, state, and community programs via their integration into clinical workflows. The Medical Tax Collaborative, founded by StreetCred, an MFP at Boston Medical Center, provides technical support to health care institutions (30 in 15 states to-date) integrating IRS-sponsored Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) free tax preparation services into clinical settings.28 Successful integration requires strong relationships with not only the IRS but also a community organization with VITA expertise. StreetCred New Haven, for example, partnered closely with their local VITA partner, the Connecticut Association for Human Services. Likewise, the Harbor-UCLA Medical-Financial Partnership embeds financial coaches into pediatric well child visits in partnership with LIFT, a national antipoverty nonprofit, to provide families with behavioral science-driven financial coaching and connections to health system and community-based financial resources.26

The Case for MFPs

Given the evidence that poverty threatens health and financial services increase families’ financial stability, MFPs are expected to impact health through their antipoverty and asset-building services. Health care is one of the only sectors reaching the vast majority (90%) of families in the preschool years;29 only 12% of children, by contrast, are in out-of-home daycare.30 The reliance on health care is even more stark during the COVID-19 pandemic, as most other services are now virtual. Even the IRS interacts with fewer families: only 80% file annually.31 Poverty exerts its strongest impact on health trajectories in these early years, which implies antipoverty medicine could play an important role.

Receiving financial services in conjunction with the trusted clinical setting may deepen patients’ relationships and trust with their medical home.29 Just as important, patients’ parents have stated they appreciate the convenience of financial services embedded in clinical settings.20 They identify financial strain as a critical driver of their own poor mental health and changes to their ideal parenting practices.7

Nascent evidence shows incorporating financial services into the medical home is feasible. For example, New York City Health and Hospitals, a member of the Medical Tax Collaborative (Table 1), filed 1,156 tax returns in 2019, returning $1.8 million to clients and yielding a social return on investment, defined as the ratio of the value generated for society to the cost of the program,32 of 673%.33 Similarly, 21% of surveyed StreetCred (Table 1) clients in 2016 and 2017 reported new receipt of the EITC.28 Moreover, Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Family (Table 1) has addressed neighborhood employment via establishing paths to employment at Nationwide Children’s and other area employers.34 Through this program, the hospital has successfully employed over 1,000 community members. A differences-in-differences analysis found a trend toward a reduction in emergency department utilization and hospitalizations in the intervention neighborhood compared to two comparison neighborhoods.35 The science of implementing MFPs is still developing, but experience from early adopters shows MFPs are feasible, complementary to routine care practices, and supported by patients, families, and clinicians.

Opportunities and Challenges for MFPs

How to Get Started

Clinics should first survey their current services. Practitioners of antipoverty medicine will recognize existing embedded services aligned with the broader concept of MFPs. For example, many material resource programs could undergo a framework shift from a focus on meeting basic and emergency needs (eg, food, transportation) to building longer-term financial stability and mobility. Simple changes in the language framing (eg, “We’re providing you with food to decrease food costs in your budget.”) could help. Next, clinics should identify community financial service nonprofits and investigate opportunities for collaboration, which could be as simple as providing connections (eg, “If you’re interested in working on your budget to reach your goals, here is a financial coaching organization.”) or as complicated as physically embedding the service in the clinical space.

Challenges

Several structural challenges exist to achieving full integration of MFP’s into health care. One overarching challenge, cultural differences between medicine and financial services, could be addressed through open, frequent communication.

Limited Time and Space in Medical Encounters

Medical visits are time-constrained. Providers juggle competing priorities, including preventive care discussions and achieving quality metrics while documenting care into complex electronic medical records (EMRs). Practitioners of antipoverty medicine must use performance improvement methods to address these challenges. Involving operations and technology leaders and frontline staff in MFP design, equipping providers with knowledge about MFPs, and integrating MFPs into EMRs are critical to maximizing efficiency and effectiveness. Using this framework improves patient screening rates and engagement with follow-up interventions.24

EMRs are evolving to capture social needs data, which could include screens for financial need and become part of routine care. Screening could occur prior to a medical visit, enabling MFP staff to connect with the patient before the scheduled appointment, saving time for patients and clinicians.

Identifying physical space in clinics for MFPs is challenging. Solutions include waiting room redesign, using exam rooms while patients wait for providers, incorporating services into home-visiting programs, and virtual models.36 Although in-person connections increase resource navigation success, more contacts, regardless of location, are associated with more uptake; thus, patients could be introduced to MFPs during clinic visits, then have follow-up contacts virtually.37

History, Perceptions, and Trust

To receive financial services, individuals must share sensitive personal and financial information. Trust is important. Historically, many BIPOC communities have been disenfranchised from financial institutions and wealth-building opportunities (eg, home ownership, GI bill). Many continue to experience the financial sector as predatory (eg, payday loans, banking, tax services). Acknowledging these experiences is important because negative experiences hinder trust. Health care seeks to build trusting relationships with patients and offers a setting where individuals are accustomed to disclosing sensitive information. New research shows families view primary care as an appropriate place to discuss financial needs.20,28

Sustainable Funding

Limited funding for MFPs is a barrier to expanding this work. Existing MFPs use grants, hospital and clinic funds, philanthropic donations, loans, and in-kind gifts from community partners. Corporate partnerships and revenue-generating social enterprise business models are largely unexplored for MFPs.

Similarly, alignment with health insurance payers’ financial incentives is untapped. Medicaid is a main source of funding for social determinants of health work but focuses on care management for high-need, high-cost adult patients.38 Opportunity exists for greater investments by Medicaid via the Section 1115 waiver program to support social determinants of health work, including MFPs. Other reimbursement mechanisms for upstream clinical services are growing for public and private payors.39 Such interventions could result in improved health, education, and future financial outcomes for children.

Antipoverty Medicine and Social Justice

In addition to considering the above challenges, we recommend considering the following opportunities when launching an MFP. First, antipoverty medicine uses MFPs as an opportunity to apply a racial equity lens and further address inequities based on financial marginalization.40 Second, MFPs afford health systems and financial service organizations the opportunity to build deeper partnerships with historically underserved communities. Third, MFPs are an opportunity for clinic leaders to add a single, new service offering in the medical setting, such as tax preparation, or a chance to redesign the clinic’s entire approach to impacting health, by offering a suite of bundled services such as tax preparation alongside financial coaching, enrollment in 529 college savings accounts, and job training.

Antipoverty Medicine to Impact Policy

Practitioners of antipoverty medicine can also engage in advocacy to change policies to impact the financial well-being of patients. Health care and community-based organizations are well-positioned to influence policy given their areas of expertise, frontline connections to social determinants of health, and passionate workforces. For example, the Healthy Families EITC Coalition, run by Children’s HealthWatch at Boston Medical Center with the MFP, StreetCred, as a member, helped advocate to increase Massachusetts’ state EITC to 30% of the federal EITC.

As another example, the Healthcare Anchor Network, a 700+ hospital network committed to addressing economic and racial inequities via inclusive hiring and place-based investment, has used their collective influence to advocate for affordable housing policies. Through a combination of congressional visits and coalition-building with national healthcare organizations, philanthropic organizations, and housing advocacy groups, health system leaders are pointing to successful cases of MFPs in their appeals for support of federal policies such as Low-Income Housing Tax Credits and HOME Investment Partnerships.41

Beyond providing service delivery and elevating patients’ lived experience, practitioners of antipoverty medicine can use MFPs to acquire more evidence to support policy change. Examples of policy priorities include health insurance, housing, food, antipoverty public benefits, and cash transfer programs (including tax credits and baby bonds). The American Academy of Pediatrics and others are already pursuing many of these policies.38

Conclusion

Antipoverty medicine is an ambitious but necessary frameshift needed to protect the health of children and families. Pediatric practices can and should intervene upon poverty directly. Current MFPs show robust feasibility and are quickly building a national movement. National health-wealth collaboratives, such as Prosperity NOW, SIREN, and StreetCred’s Medical Tax Collaborative, are bringing innovators, clinicians, and experts together to ensure antipoverty medicine becomes a key strategy for sustainable, measurable gains in child health in the United States.

The current fiscal challenges of our health care system require a systematic approach to evaluating the impact of MFPs.42 The variety of MFP models presents opportunities for evaluation of the best approaches to build collaborations between health care and financial services, financial sustainability models, and effectiveness with respect to health and financial well-being.43

Increased national attention on health equity establishes a growth environment for MFPs in both scale and scope.44 As the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed, we cannot wait to address structural economic disparities. Let us pursue antipoverty medicine now and create a healthier future for America’s children.

What This Narrative Review Adds.

We present the approach of anti-poverty medicine, which encompasses use of Medical-Financial Partnerships (MFPs) between health care system and financial capabilities organizations. This approach “treats” poverty and its associated poor health outcomes.

Acknowlogments

We would like to acknowledge Abbey Glick for her assistance with manuscript editing and formatting. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Reference

- 1.Parolin Z, Wimer C. Forecasting Estimates of Poverty during Covid-19 Crisis. 4. 20202020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5743308460b5e922a25a6dc7/t/5e9786f17c4b4e20ca02d16b/1586988788821/Forecasting-Poverty-Estimates-COVID19-CPSP-2020.pdf.

- 2.Bhutta N, Dettling L. Money in the Bank? Assessing Families’ Liquid Savings Using the Survey of Consumer Finances. 2018. 10.17016/2380-7172.2275. Washington, DC. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan G A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. (Duncan G, Le Menestrel S, eds.). Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2019. doi: 10.17226/25246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137: e20160339–e20160339. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell ON, Hole MK, Johnson K, et al. Medical-financial partnerships: cross-sector collaborations between medical and financial services to improve health. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:166–174. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schickedanz A, Gottlieb L, Szilagyi P. Will social determinants reshape pediatrics? Upstream clinical prevention efforts past, present, and future. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19:858–859. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marcil LE, Campbell JI, Silva KE, et al. Women’s experiences of the effect of financial strain on parenting and mental health. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2020. 10.1016/j.jogn.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bialik K, Fry R. How Millennials Compare with Prior Generations Pew Research Center. February 2019.

- 9.Berry WS, Blatt SD. Diaper need? You can bank on it. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:188–189. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keith-Jennings B, Llobrera J, Dean S. Links of the supplemental nutrition assistance program with food insecurity, poverty, and health: evidence and potential. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:1636–1640. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E, et al. Variation in health outcomes: the role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–09. Health Aff. 2016;35:760–768. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA. 2016;315:1750. 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon D, McInerney M, Goodell S. The Earned Income Tax Credit, Poverty, And Health.; 2018. doi: 10.1377/hpb20180817.769687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komro KA, Markowitz S, Livingston MD, et al. Effects of state-level earned income tax credit laws on birth outcomes by race and ethnicity. Heal Equity. 2019;3:61–67. 10.1089/heq.2018.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank DA, Neault NB, Skalicky A, et al. Heat or eat: the low income home energy assistance program and nutritional and health risks among children less than 3 years of age. Pediatrics. 2006;118: e1293–e1302. 10.1542/peds.2005-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ettinger de Cuba S, Chilton M, Bovell-Ammon A, et al. Loss of SNAP is associated with food insecurity and poor health in working families with young children. Health Aff. 2019;38:765–773. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Theodos B, Simms M, Treskon M, et al. An Evaluation of the Impacts and Implementation Approaches of Financial Coaching Programs.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyes B, López E. How a Culturally Relevant Social-Lending Program Benefits People with Low or Nonexistent Credit Scores.; 2016.

- 19.White ND, Packard K, Kalkowski J. Financial education and coaching: a lifestyle medicine approach to addressing financial stress. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13:540–543. 10.1177/1559827619865439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quinn C, Johnson K, Raney C, et al. “In the clinic they know us”: preferences for clinic-based financial and employment services in urban pediatric primary care. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18:912–919. 10.1016/j.acap.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beverly SG, Clancy M, Sherraden M. Testing Universal College Savings Accounts at Birth: Early Research from SEED for Oklahoma Kids. Vol CSD Resear.; 2014. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/233232789.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Nam Y, Sherraden M, et al. Impacts of child development accounts on parenting practices: evidence from a randomised statewide experiment. Asia Pacific J Soc Work Dev. 2019;29:34–47. 10.1080/02185385.2019.1575270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang J, Sherraden M, Kim Y, et al. Effects of child development accounts on early social-emotional development: an experimental test. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:265–271. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White ND, Packard KA, Flecky KA, et al. Two year sustainability of the effect of a financial education program on the health and wellbeing of single, low-income women. J Financ Couns Plan. 2018;29:68–74. 10.1891/1052-3073.29.1.68. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Neill B, Sorhaindo B, Xiao JJ, et al. Financially distressed consumers: their financial practices, financial well-being, and health. J Financ Couns Plan. 2005;16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schickedanz A, Perales L, Avarenga C, et al. Financial coaching plus social needs navigation leads to improved health-related quality of life: a community-partnered randomized trial. In: Toronto, CA; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelleher K, Reece J, Sandel M. The healthy neighborhood, healthy families initiative. Pediatrics. 2018;142: e20180261. 10.1542/peds.2018-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcil LE, Hole MK, Wenren LM, et al. Free tax services in pediatric clinics. Pediatrics. 2018;141. 10.1542/peds.2017-3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Well-Child Visits. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/indicator_1460473904.404.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed January 26, 2021.

- 30.Paschall K. Nearly 30 percent of infants and toddlers attend home-based child care as their primary arrangement. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/blog/nearly-30-percent-of-infants-and-toddlers-attend-home-based-child-care-as-their-primary-arrangement. Published 2019. Accessed January 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.EITC Fast Facts. Internal Revenue Service. https://www.eitc.irs.gov/partner-toolkit/basic-marketing-communication-materials/eitc-fast-facts/eitc-fast-facts. Published 2021. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- 32.An Introduction to Social Return on Investment. Stanford Graduate School of Business. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/gsb-cmis/gsbcmis-download-auth/354066. Published 2004. Accessed January 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black S, Sisco S, Williams T, et al. Return on investment from co-locating tax assistance for low-income persons at clinical sites. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323. 10.1001/jama.2020.0545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franz B, Skinner D, Kerr AM, et al. Hospital–community partnerships: facilitating communication for population health on Columbus’ south side. Health Commun. 2018;33:1462–1474. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1359033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chisolm DJ, Jones C, Root ED, et al. A community development program and reduction in high-cost health care use. Pediatrics. 2020;146: e20194053. 10.1542/peds.2019-4053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottlieb LM, Adler NE, Wing H, et al. Effects of in-person assistance vs personalized written resources about social services on household social risks and child and caregiver health. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e200701. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manian N, Wagner CA, Placzek H, et al. Relationship between intervention dosage and success of resource connections in a social needs intervention. Public Health. 2020;185:324–331. 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Addressing Social Determinants of Health via Medicaid Managed Care Contracts and Section 1115 Demonstrations. Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.chcs.org/media/Addressing-SDOH-Medicaid-Contracts-1115-Demonstrations-121118.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed January 28, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Policy Guidance. ACES Aware. https://www.acesaware.org/about-aces-aware/policy-guidance/. Published 2021. Accessed January 28, 2021.

- 40.Raphael JL, Oyeku SO. Implicit bias in pediatrics: an emerging focus in health equity research. Pediatrics. 2020;145: e20200512. 10.1542/peds.2020-0512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pham BH. Health systems and housing: collaborating to promote affordable housing policy opportunities. Democr Collab. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gottlieb L, Sandel M, Adler NE. Collecting and applying data on social determinants of health in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1017. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fichtenberg C, Delva J, Minyard K, et al. Health and human services integration: generating sustained health and equity improvements. Health Aff. 2020;39:567–573. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horwitz LI, Chang C, Arcilla HN, et al. Quantifying health systems’ investment in social determinants of health, by sector, 2017–19. Health Aff. 2020;39:192–198. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]