Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that was first identified during the outbreak in Wuhan, China in 2019. It is an acute respiratory illness that can transfer among human beings. Natural products can provide a rich resource for novel antiviral drugs. They can interfere with viral proteins such as viral proteases, polymerases, and entry proteins. Several naturally occurring flavonoids were reported to have antiviral activity against different types of RNA and DNA viruses. A methanolic extract of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves is rich in phenolic compounds, mainly flavonoids. Metabolic profiling of the secondary metabolites of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves methanolic extract (MLME), and bark ethyl acetate (MBEE) extract using LC-HRESIMS resulted in the isolation of 18 compounds belonging to a variety of constituents, among which phenolic compounds, flavones, flavonol glycosides and triterpenes were predominant. Besides, four compounds (I–IV) were isolated and identified as myricetin I, myricitrin II, mearnsitrin III, and mearnsetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside IV (compound IV is isolated for the first time from genus Manilkara) and dereplicated in a metabolomic study as compounds 3, 5, 6, and 12, respectively. The molecular docking study showed that rutin, myricitrin, mearnsitrin, and quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside have strong interaction with SARS-CoV-2 protease with high binding energy of −8.2072, −7.1973, −7.5855, and −7.6750, respectively. Interestingly, the results proved that rutin which is a citrus flavonoid glycoside exhibits the strongest inhibition effect to the SARS-CoV-2 protease enzyme. Consequently, it can contribute to developing an effective antiviral drug lead against the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus that was first identified during the outbreak in Wuhan, China in 2019.

1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is the main cause of the 2019–2020 viral pneumonia outbreak that appeared first in Wuhan.1–4 Finding a known drug that inhibits the SARS-CoV-2 virus main protease (Mpro) will have a pivotal role in controlling viral replication and transcription.5,6 Zhenming Jin, et al., determined the crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 virus Mpro in complex with N3 mechanism-based inhibitor.7 The functional polypeptides are released from the polyproteins by extensive proteolytic processing, predominantly by a 33.8 kDa main protease (Mpro), also referred to as the 3C-like protease. Mpro digests the polyprotein at no less than 11 conserved sites, starting with the autolytic cleavage of this enzyme itself from pp1a and pp1ab.8 The functional importance of Mpro in the viral life cycle, together with the absence of closely related homologs in humans, identify Mpro as an attractive target for antiviral drug design.9 Several naturally occurring flavonoids possess variable antiviral activity against certain RNA viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza virus type 3 (Pf-3), polio-virus type 1 (polio) and DNA viruses such as Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1).10 Antiviral activity of the myricetin derivatives and methoxy flavones was evaluated against Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 (HSV-1), and Poliovirus type 1 (PV-1); it showed antiviral activity without cytotoxic effects. The methoxy flavones were the most active compounds, showing an antiviral effect against all the evaluated viruses.11 Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the total phenolic and flavonoid content, metabolic profiling with LC-HRESIMS-assisted chemical investigation of the secondary metabolites of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard (family: Sapotaceae), isolation, and structure elucidation of four flavonol compounds. Additionally, a molecular docking study was performed to study the inhibitory effect of these flavonoids against SARS-CoV-2 main protease enzymes.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Metabolic profiling

Metabolomics is a valuable and comprehensive analysis tool that is used to study the metabolite profiles of unicellular and multicellular biological systems.14 Plants represent a major challenge in metabolomics due to the high chemical diversity of their metabolites.14 Consequently, no single analytical method can determine all plant metabolites simultaneously, but LC-HRESIMS is a powerful analytical tool for metabolic profiling that can detect/dereplicate a wide range of chemical compounds at the same time without tedious isolation procedures.15,16

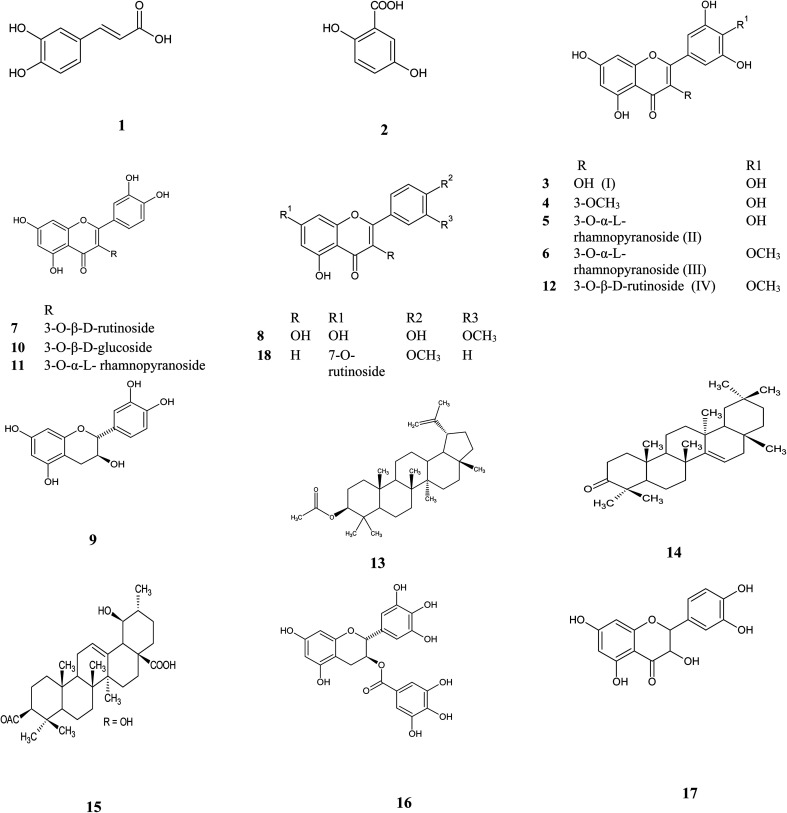

Metabolic profiling of the secondary metabolites of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves methanolic extract (MLME), and bark ethyl acetate (MBEE) extract using LC-HRESIMS (ESI, Fig. S18†) resulted in the annotation of eighteen compounds belong to a variety of constituents, among which phenolic, flavones, flavonol glycosides and triterpenes were predominant,12,13 with qualitative and quantitative variation in each extract (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

The LC-HR-ESIMS annotation results of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves and bark extractsa.

| No. | Metabolites name | Original source | Chemical class | Mode | MF | RT (min) | m/z | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Caffeic acid | Manilkara zapota | Phenolic acid | + | C9H8O4 | 3.27 | 181.0489 | 17 |

| 2 | 2,5-Dihydroxy benzoic acid | Alchornea cordifolia | Unsaturated carboxylic acid | + | C7H6O4 | 2.11 | 155.0332 | 18 |

| 3 | Myricetin I | Mimusops laurifolia | Flavonol | + | C15H10O8 | 2.65 | 319.0441 | 21 |

| 4 | Myricetin-3-O-methyl ether | Pteroxygonum giraldii | Flavonol | + | C16H12O8 | 2.97 | 333.0608 | 19 |

| 5 | Myricitrin II | Manilkara Subsericea | Flavonol glycoside | + | C21H20O12 | 4.31 | 465.1026 | 19 |

| 6 | Mearnsitrin III | Mimusops laurifolia | Flavonol glycoside | + | C22H22O12 | 4.51 | 479.1179 | 21 |

| 7 | Rutin | Mimusops laurifolia | Flavonol glycoside | + | C27H30O16 | 1.88 | 611.1604 | 21 |

| 8 | 3′-Methoxy-4′,5,7-trihydroxy flavonol | Cuscuta reflexa | Flavonol | + | C16H12O7 | 3.81 | 317.0653 | 22 |

| 9 | (+) Catechin | Manilkara zapota | Flavan-3-ol | + | C15H14O6 | 2.49 | 291.0787 | 25 |

| 10 | Quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside | Mimusops laurifolia | Flavonol glycoside | + | C21H20O12 | 3.38 | 465.1026 | 21 |

| 11 | Quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside | Manilkara Subsericea | Flavonol glycoside | + | C21H20O11 | 2.69 | 449.1073 | 41 |

| 12 | Mearnsetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside IV | Manilkara hexandra | Flavonol glycoside | + | C28H32O17 | 5.55 | 641.1713 | 21 |

| 13 | Lupeol-3-acetate | Mimusops elengi | Triterpene | + | C32H52O2 | 4.32 | 469.4034 | 28 |

| 14 | Taraxerone | Mimusops elengi | Triterpene | + | C30H48O | 5.62 | 425.3785 | 42 |

| 15 | 3-Acetyl ursolic acid | Mimusops obtusifolia | Triterpene | + | C32H50O4 | 4.04 | 499.3736 | 27 |

| 16 | Gallocatechin-3-O-gallate | Camellia sinensis | Catechin | + | C22H18O11 | 6.35 | 459.0846 | 26 |

| 17 | Taxifolin | Mimusops elengi | Flavanonol | + | C15H12O7 | 2.86 | 305.0657 | 24 |

| 18 | Acacetin-7-O-rutinoside | Origanum syriacum | Flavonoid-7-O-glycoside | + | C28H32O14 | 3.39 | 593.1873 | 23 |

MF: molecular formula, RT: retention time, min: minute.

Fig. 1. Isolated and annotated metabolites from the LC-HRESIMS analysis of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves and bark extracts.

From the metabolomics data, the mass ion peak at m/z 181.0489 for the predicted molecular formula C9H8O4 was dereplicated as caffeic acid, which was previously detected in Manilkara zapota and first reported in Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard,17 whereas that at m/z 155.0332, corresponding to the suggested molecular formula C7H6O4 was dereplicated as 2,5 dihydroxy benzoic acid, which was formerly reported from the African tree Alchornea cordifolia and first reported from Manilkara genus.18 Likewise, a flavone aglycon with the molecular formula C15H10O8 was characterized as 3,5,7,3′,4′,5′-hexahydroxy-flavone (myricetin) I from the mass ion peak at m/z 319.0441, which was previously obtained from Mimusops laurifolia.19 Moreover, the mass ion peak at m/z 333.0608, in agreement with the predicted molecular formula C16H12O8 was dereplicated as myricetin-3-O-methyl ether. This has been isolated earlier from Pteroxygonum giraldii.20 The mass ion peaks at m/z 465.1026 and 479.1179, for the predicted molecular formulas C21H20O12, C22H22O12, and were dereplicated as the flavonol glycoside myricetin 3-O-α-l-1C4 rhamnopyranoside (myricitrin) II and myricetin-4′-O-methyl ether-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (mearnsitrin) III, respectively, which were previously detected in Manilkara Subsericea and Mimusops laurifolia respectively, and were first reported in Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard.19,21 Whereas, the mass ion peaks at m/z 641.1713, corresponding to the suggested molecular formula C28H32O17, was identified as mearnsetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside IV, which was the first report for this metabolite in Manilkara genus and Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard. Likewise, another flavonol glycosides with the molecular formulas C27H30O16, C21H20O12 and C21H20O11 were characterized as quercetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside (rutin), quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside and quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (quercitrin), from the mass ion peak at m/z 611.1604, 465.1026 and 449.1073, were previously obtained from Mimusops laurifolia and Manilkara Subsericea.19,21 Additionally, a compound at m/z 317.0653, corresponding to the suggested molecular formula C16H12O7 was dereplicated as 3′-methoxy-4′,5,7 trihydroxy flavonol, which was formerly reported from the species Cuscuta reflexa and was first reported in the Manilkara genus.22 Likewise, a flavonoid-7-O-glycosides compound with the molecular formula C28H32O14 was characterized as acacetin-7-O-rutinoside from the mass ion peak at m/z 593.1873 and was previously obtained from Origanum syriacum.23 Furthermore, a compound at m/z 305.0657, corresponding to the suggested molecular formula C15H12O7 was dereplicated as taxifolin (5,7,3′,4′-flavan-on-ol), which was formerly reported from the Mimusops elengi.24 Another mass ion peaks at m/z 291.0787 and 459.0846 for the predicted molecular formula C15H14O6 and C22H18O11, respectively was dereplicated as (+) catechin and, gallocatechin-3-O-gallate respectively, the two compounds were previously detected in Manilkara zapota and Camellia sinensis,25,26 and first reported in Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard. In addition to the above-mentioned molecules, triterpenoid compounds at the mass ion peaks at m/z 469.4034, 425.3785 and 499.3736 for the suggested molecular formulas C32H52O2, C30H48O and C32H50O4 were annotated as lupeol-3-acetate, taraxerone, and 3-acetyl ursolic acid, respectively, which were previously reported in Mimusops elengi and Mimusops obtusifolia.27,28

2.2. Structure elucidation of the isolated compounds

Based on the physicochemical, chromatographic properties, and spectral analysis using (UV, MS, 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR), as well as comparison with the literature and some authentic samples, four compounds were isolated and identified as 3,5,7,3′,4′,5′-hexahydroxy-flavone (myricetin) (I),29 myricetin 3-O-α-l-1C4 rhamnopyranoside (myricitrin) (II),30 myricetin-4′-O-methyl ether-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (mearnsitrin) (III),19 and mearnsetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside (IV).19 Compounds I–III were previously isolated from Manilkara species, but they were isolated for the first time from the species Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard.17,19,21 Compound IV was isolated for the first time from Manilkara species as well as Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard.

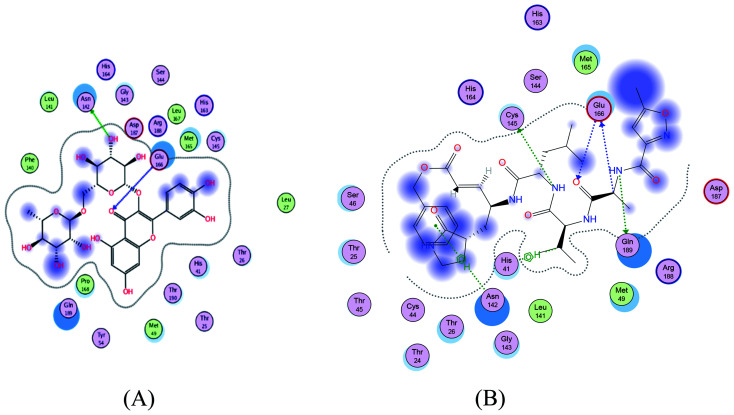

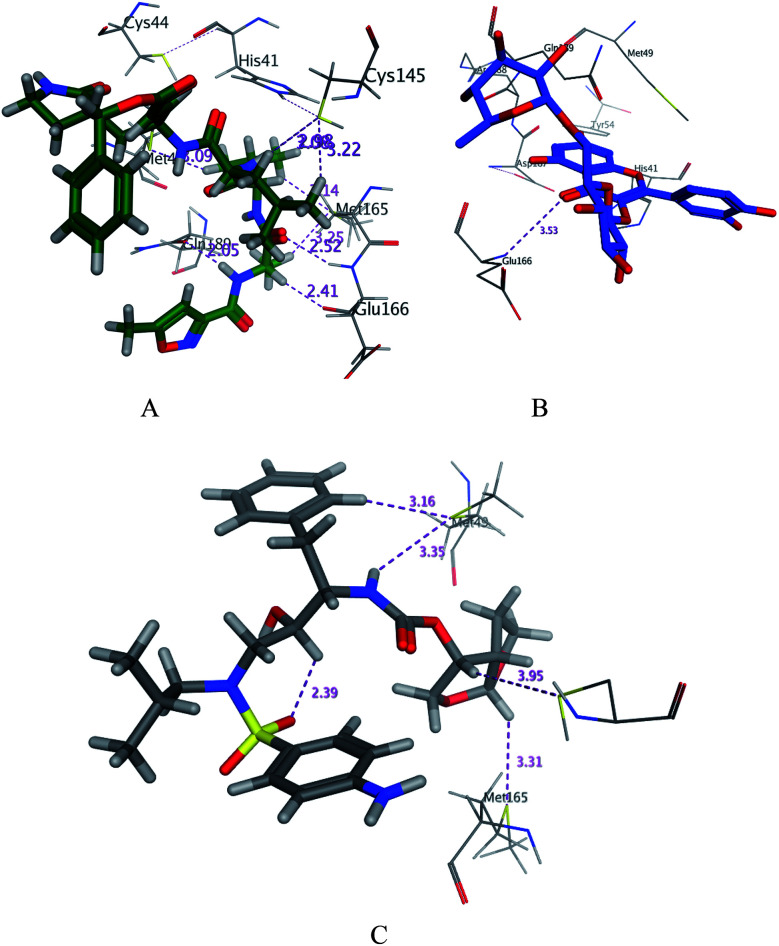

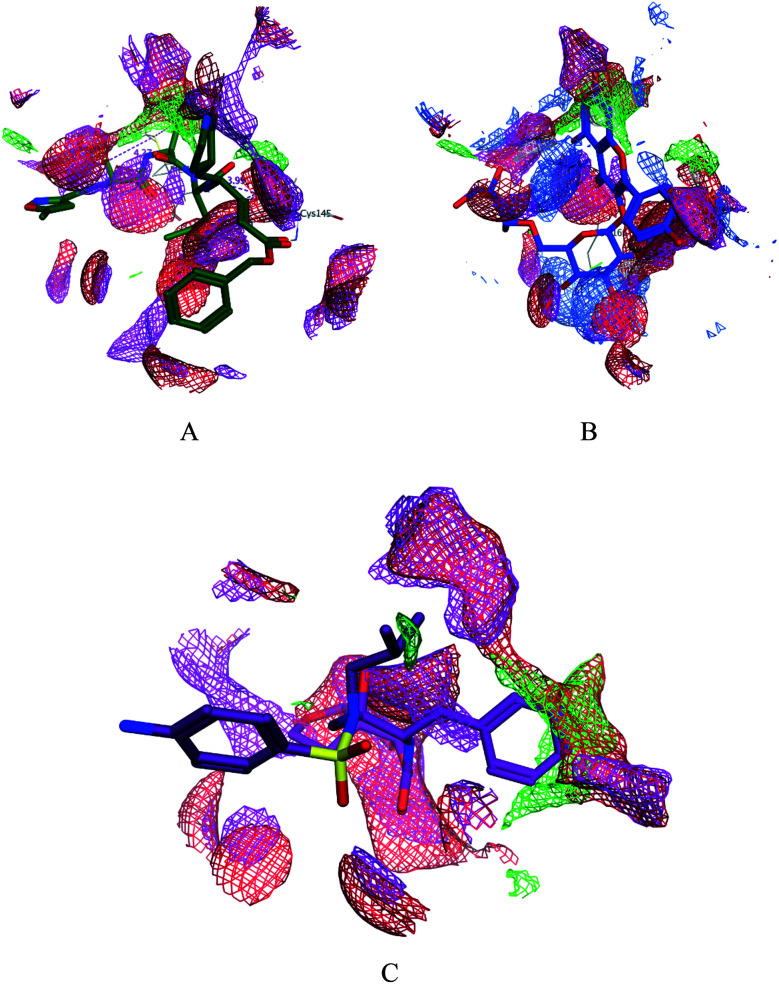

2.3. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 molecular docking study

SARS-CoV-2 virus Mpro has a Cys–His catalytic dyad, and the substrate-binding site is located in a cleft between domain I and II. A Michael acceptor inhibitor known as N3 was developed using computer-aided drug design.31,32 N3 is fitted inside the substrate-binding pocket of SARS-CoV-2 virus Mpro showing asymmetric units containing only one polypeptide. All compounds showed nearly bindings like N3. Results of interaction energies with Mpro are shown in Table 2. Molecular docking simulation of the compounds, darunavir and N3 into Mpro active site was performed. They got stabilized at the N3-binding site of Mpro by variable several electrostatic bonds (Fig. 2–4). The order of strength of binding was as follows:N3> 7 > 10 > 6 > 5 > darunavir > 11 > 4 > 3 > 9 > 8 > 1 > 2

The receptor interaction of and the binding energy scores of the identified compounds, darunavir, and N3 into the N3 binding site in the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

| Compound | dG, kcal mol−1 | E_Conf., kcal mol−1 | E_Place, kcal mol−1 | E_Refine | Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dG, kcal mol−1 | Amino acid/type of bonding/distance (Å)/binding energy (kcal mol−1) | ||||

| 1 | −5.1104 | −20.7880 | −7.4002 | −8.2307 | Met49/H-donor/3.51/−0.2 |

| 2 | −3.6132 | 31.6316 | −15.5250 | −17.3981 | — |

| 3 (I) | −5.9328 | 31.6316 | −15.5250 | −17.3981 | Met165/H-donor/3.26/−0.4 |

| 4 | −6.2258 | 48.0913 | −15.3310 | −19.7152 | Gln189/Pi-H/4.25/−0.7 |

| 5 (II) | −7.1973 | 122.4130 | −18.0611 | −21.2239 | Met165/H-donor/2.71 and 3.28/−0.3 and −0.2 and Cys145/H-donor/3.68/−0.2 |

| 6 (III) | −7.5855 | 145.0424 | −19.1410 | −26.5002 | Phe140/H-donor/2.93/−1.8 and Gln189/H-donor/3.29/−0.7, Met49/H-donor/3.58/−1.0 |

| 7 | −8.2072 | 211.5644 | −24.6113 | −30.4412 | Asn142/H-donor/3.05/−2.2 and Glu166/H-acceptor 3.53/−0.8 |

| 8 | −5.7864 | 62.4023 | −11.8787 | −17.1581 | Thr190/H-donor/2.25/−0.4 |

| 9 | −5.8134 | 23.4276 | −12.6033 | −18.7543 | His164/H-donor/2.56/−0.3, Met165/H-donor/3.75/−1.6 and Gln189/H-donor/2.47/−0.2 |

| 10 | −7.6750 | 126.5861 | −15.3358 | −25.6531 | Met165/H-donor/3.65/−0.4 and His163/H-acceptor 3.09/−2.3 |

| 11 | −6.9873 | 128. | −21.1809 | −20.2922 | Met165/H-donor/1.75/−1.5, Met49/H-donor/1.95/−0.99, Cys145/H-donor/1.81/−0.51, Gln189/H-donor/2.01/−0.63 and His 163/H-donor/2.4/−0.41 |

| Darunavir | −7.0415 | −26.4826 | −18.8722 | −12.8003 | Cys145/H-donor/3.95/−0.4, Met49/H-donor/3.35/−0.7, Gln189/H-donor/2.2/−0.42 and His41/H-Pi/3.33/−0.1 |

| N3 | −8.4767 | −4.5013 | −18.6098 | −24.9301 | Gln189/H-donor 2.96/−2.3, Glu166/H-donor/3.34/−0.6, Cys145/H-donor/3.99/−2.0, Glu166/H-acceptor 3.48/−0.6, His41/H-Pi/3.71/−0.7 and Asn/Pi-H/4.16/−1.2 |

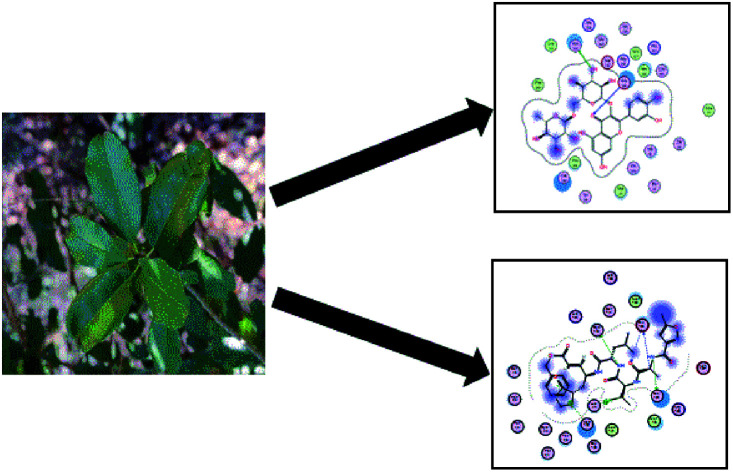

Fig. 2. 2D representation of docking of compounds 7 (A), and N3 (B) into the N3 binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Fig. 3. 3D docking poses of compounds 7 (A), and N3 (B) and darunavir (C) into the N3 binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Fig. 4. Surface and maps of the interaction potential of compounds 7 (A) and N3 (B) and darunavir (C) with the N3 binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

The glycosidic compounds were promising as protease inhibitors than the other aglycone phenolic compounds. Rutin was the most promising compound with high binding energy in comparison with the other compounds.

It worth mentioning that several molecular docking studies were performed to systematically investigate the effect of flavonoids on SARS-CoV-2 target proteins.33,34 Owis et al.35 reported that flavonoid compounds narcissin, kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-[α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)]-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, and isorhamnetin-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-O-[α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→2)]-O-β-d-galactopyranoside showed high stability in the N3 binding site. Additionally, Jo et al.36 reported that herbacetin, rhoifolin, and pectolinarin were found to efficiently block the enzymatic activity of SARS-CoV 3C like protease (3CLpro). Moreover, kaempferol, quercetin, and rutin were also able to bind at the substrate-binding pocket of 3CLpro with high affinity (105–106 M−1). Additionally, they interact with the active site residues such as His41 and Cys145 through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions.37 These results suggest the potential effect of flavonoids as novel inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 with comparable potency as that of darunavir.

3. Experimental

3.1. Plant material

Leaves and bark of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard (family: Sapotaceae) was collected in October plants cultivated in the Zoo. The plant was identified by Mrs Terase Labib, Taxonomist of Orman Garden, Giza, Egypt. The identity of the plant was kindly confirmed by Dr Mohamed El-Gebaly, Lecturer of Plant Taxonomy, National Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Voucher specimens (code: M-04-2016) are kept in the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy (Girls), Al-Azhar University.

3.2. Extraction and purification of the plant material

The air-dried powdered leaves of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard (3 kg) were extracted with hot 70% aqueous MeOH under reflux (3 kg, 5 × 6 L) refluxed for 72 hours at 70 °C then evaporation of MeOH under vacuum to get (521 g) dry extract. The concentrated methanolic extract (521 g) was suspended in 100 mL distilled water and successively extracted with methylene chloride (3 × 750 mL) under reflux for 4 hours on a water bath at 40 °C then separation of the organic layer with the separating funnel and evaporation to obtain (5 g), re-evapourate the aqueous residue via a rotary evaporator till dryness and extraction by refluxing with ethyl acetate for 12 hours (4 × 750 mL) on a water bath at 70 °C (10 g), then complete evaporation of the remaining aqueous part, followed by fractionation with butanol by refluxing on a water bath for 36 hours at 70 °C (3 × 1000 mL) which give (12 g), finally re-evaporation of the remaining aqueous part via rotary evaporator and extraction with 100% methanol to precipitate sugars and inorganic salts by refluxing on a water bath for 48 hours at 70 °C (6 × 1000 mL) to obtain (210 g). The methanolic extract (210 g) is then applied on polyamide column chromatography using H2O then H2O/MeOH mixture up to 100% MeOH by using paper chromatography, UV-light, and spray reagents similar fractions of polyamide columns were collected (collected fraction from 1–3). Fractions 1 and 2 were eluted at 20% aqueous methanol then concentrated under vacuum and the residue of collected fraction 1 was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography using (butanol : isopropyl alcohol : water) (4 : 1 : 5) as a solvent system then the eluted fraction (6–8) are applied on cellulose column chromatography using gradient elution from 30% aqueous methanol (compound III). While collected fraction 2 residue was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography using gradient elution started with 15% aqueous methanol till 100% methanol to obtain compound IV which was eluted at 30% aqueous methanol. Collected fraction 3 eluted with 30% methanol from polyamide column was then submitted to gel filtration on Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography using 100% methanol to obtain compound II. Compound I was eluted at 40% aqueous methanol from the polyamide column. Then absolute ethanol on Sephadex LH-20 was used for purification of the isolated compounds I–IV. Sub-fractions were collected based on comparing paper chromatography and TLC and visualized with UV and sprayed with different reagents.

3.3. Metabolomic analysis procedure

Air-dried and finely powdered Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves and bark (2 g each). Leaves were exhaustively extracted with 70% aqueous methanol (3 × 5 ml) at room temperature and concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C to afford 80 mg crude methanolic extract, while the bark was extracted first with 70% aqueous methanol followed by fractionation with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL) at room temperature and concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C to afford 50 mg ethyl acetate extract. The crude extracts were subjected to metabolomic analysis using analytical techniques of LC-HRESIMS.38–40 LC-HRESIMS metabolomics analyses were performed on an Acquity Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography system coupled to a Synapt G2 HDMS quadrupole time-of-flight hybrid mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was carried out on a BEH C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a guard column (2.1 × 5 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) and a linear binary solvent gradient of 0–100% eluent B, over 6 min, at a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1, using 0.1% formic acid in water (v/v) as solvent A and acetonitrile as solvent B. The injection volume was 2 μL and the column temperature was 40 °C. After chromatographic separation, the metabolites were detected by mass spectrometry using electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive mode; the source was operated at 120 °C. The ESI capillary voltage was set to 0.8 kV, the sampling cone voltage was set to 25 V and nitrogen (at 350 °C, a flow rate of 800 L h−1) was used as the desolvation gas and the cone gas (flow rate of 30 L h−1). The mass range for TOF-MS was set from m/z (mass-to-charge ratio) 50–1200. In MZmine 2.12, the raw data were imported by selecting the ProteoWizard converted positive files in the mzML format. Mass ion peaks were detected and followed by a chromatogram builder and a chromatogram deconvolution. The local minimum search algorithm was applied, and isotopes were also identified via the isotopic peaks grouper. Missing peaks were detected using the gap-filling peak finder. An adduct search, as well as a complex search, was performed. The processed data set was then subjected to molecular formula prediction and peak identification. The positive and negative ionization mode structures from each of the respective plant extracts were dereplicated against the DNP database Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) database.

3.4. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 docking studies

3.4.1. Target compounds optimization

The target compounds were constructed into a 3D model by Molecular Operating Environment® 2019 program. After checking their structures and the formal charges on atoms by the 2D depiction, the following steps were carried out: the target compounds were subjected to a conformational search. All conformers were subjected to energy minimization, all the minimizations were performed until an RMSD gradient of 0.01 kcal mol−1 and RMS distance of 0.1 Å with MMFF94X force-field and the partial charges were automatically calculated. The obtained database was then saved as an MDB file to be used in the docking calculations.41

3.4.2. Optimization of the enzymes active site

The X-ray crystallographic structure of Mpro complexed with N3 was obtained from the Protein Data Bank through the internet (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/, code 6LU7).7 Molecular Operating Environment® 2019 program was used for the preparation of the enzyme for the docking studies by adding hydrogen atoms to the system with their standard geometry. The atoms' connection and type were checked for any errors with automatic correction. The selection of the receptor and its atoms potential were fixed. Site Finder was used for the active site search in the enzyme structure using all default items. Dummy atoms were created from the site finder of the pocket. The docking was validated by the redocking of the energetically minimized ligand N3 and the root mean square deviation that obtained was 1.4228 Å2.

3.4.3. Docking of the target molecules to viral main protease binding site

Docking of the conformation database of the target compounds was done after the removal of the ligand N3. The following methodology was generally applied: the enzyme active site file was loaded, and the docking tool was initiated. The program specifications were adjusted to dummy atoms as the docking site, alpha triangle as the placement methodology to be used. The scoring methodology London dG is used and was adjusted to its default values. The MDB file of the ligand to be docked was loaded and dock calculations were run automatically. The poses that showed best ligand–enzyme interactions were selected and stored for energy calculations.42

4. Conclusion

This study demonstrated the high efficiency of LC-HRESIMS in metabolomic profiling of Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard different leaves and bark, which dereplicated different chemical metabolomic compounds belonging to different classes, including phenolic, flavones, flavonol glycosides, and triterpenes. A phytochemical investigation of the Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard leaves afforded isolation of four flavonols for the first time from Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard and one of them are isolated for the first time from the Manilkara genus, which identified as mearnsetin-3-O-β-d-rutinoside. Investigating the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of compounds (1–11) using molecular docking simulation study showed that rutin, myricitrin, mearnsitrin, and quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside are promising SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. The study high lights that rutin which is a citrus flavonoid glycoside and can be found in green tea, grape seeds, red pepper, apple, citrus fruits, berries, and peaches34 have the highest activity as SARS-CoV-2 protease inhibitor followed by quercetin 3-O-β-d-glucoside, mearnsitrin, and myricitrin which can be found in vegetables, fruits, nuts, and spices.43 It worth mentioning that rutin has a very impressive pharmacological profile and can possess different therapeutic activities e.g. anti-inflammatory and antiviral activity.44 So, based on the above information, there is an urgent need for in vivo studies of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 potential of rutin which will give a hopeful and safe insight in discovering a targeting drug against the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank M. Müller and M. Krischke (The University of Würzburg) for instrumental support.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/d0ra05679k

References

- Zhu N. Zhang D. Wang W. Li X. Yang B. Song J. Zhao X. Huang B. Shi W. Lu R. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. Guan X. Wu P. Wang X. Zhou L. Tong Y. Ren R. Leung K. S. Lau E. H. Wong J. Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P. Yang X.-L. Wang X.-G. Hu B. Zhang L. Zhang W. Si H.-R. Zhu Y. Li B. Huang C.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F. Zhao S. Yu B. Chen Y.-M. Wang W. Song Z.-G. Hu Y. Tao Z.-W. Tian J.-H. Pei Y.-Y. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Yang M. Ding Y. Liu Y. Lou Z. Zhou Z. Sun L. Mo L. Ye S. Pang H. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand K. Palm G. J. Mesters J. R. Siddell S. G. Ziebuhr J. Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra α-helical domain. EMBO J. 2002;21:3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Du X. Xu Y. Deng Y. Liu M. Zhao Y. Zhang B. Li X. Zhang L. Peng C. Structure of Mpro from COVID-19 virus and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi A. Ziebuhr J. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:595–599. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-3-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar T. Manickam M. Namasivayam V. Hayashi Y. Jung S.-H. An Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) 3CL Protease Inhibitors: Peptidomimetics and Small Molecule Chemotherapy. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:6595–6628. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul T. Middleton E. Ogra P. Antiviral effect of flavonoids on human viruses. J. Med. Virol. 1985;15:71–90. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890150110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. Luisa M. Isabel A. Baptista J. Helene F. Vicenta L. Rodolfo H. Rafael H. Antiviral activity of flavonoids present in aerial parts of Marcetia taxifolia against Hepatitis B virus, Poliovirus, and Herpes Simplex Virus in vitro. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Science. 2019;18:1037–1048. doi: 10.17179/excli2019-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singletone V. Orthofer R. Lamuela-Raventose R. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. Yang M. Wen M. Chern C. Estimation of Total Flavonoid Content in Propolis by Two Complementary Colorimetric Methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2002;10:178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Rambla L., Lopez P., Belles M. and Granell A., Metabolomic Profiling of Plant Tissues, in Plant Functional Genomics, Springer, New York, NY, USA, 2015, pp. 221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J. Haselden N. Metabolic profiling as a tool for understanding mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicol. Pathol. 2008;36:140–147. doi: 10.1177/0192623307310947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allwood W. Goodacre R. An introduction to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry instrumentation applied in plant metabolomic analyses. Phytochem. Anal. 2010;21:33–47. doi: 10.1002/pca.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayek M. Abdel Monem R. Mossa Y. Meselhy R. Shazly H. Chemical and biological study of Manilkara zapota (L.) Van Royen leaves (Sapotaceae) cultivated in Egypt. Pharmacogn. Res. 2012;4:85–91. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.94723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante I. Amuzu N. Donkor A. Annan K. Screening of Some Ghanaian Medicinal Plants for Phenolic Compounds and Radical Scavenging Activities. Pharmacogn. J. 2009;1:201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel V. Bailleul F. Waterman P. (Rel)-1b,2a-di-(2,4-dihydroxy-6-methoxybenzoyl)-3b,4a-di-(4-methoxyphenyl)-cyclobutane and other flavonoids from the aerial parts of Goniothalamus gardneri and Goniothalamus thwaitesii. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:439–446. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. Su Y. Yan S. Wu Z. Zhang X. Wang T. Gao X. Hexaoxygenated flavonoids from Pteroxygonum giraldii. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010;5:223–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes P. Corrêa L. Lobo R. Caramel P. Almeida B. Castro S. et al., Triterpene Esters and Biological Activities from Edible Fruits of Manilkara subsericea (Mart.) Dubard, Sapotaceae. BioMed Res. Int. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/280810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S. Dandopani C. Chemical Characterization of the Flavonoid Constituents of Cuscuta reflexa. J. Pharm. BioSci. 2014;2:13–16. doi: 10.20510/ukjpb/2/i3/91163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Desouky S. Lamyaa I. Kawashtya S. Young-Kyoon K. Phytochemical Constituents and Biological Activities of Origanum syriacum. Z. Naturforsch. 2009;64:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Kadam V. Yavada S. Shivatare S. Patil J. Mimusops elengi: A Review on Ethnobotany, Phytochemical and Pharmacological Profile. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2012;1:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. Luo X. Protiva P. Yang H. Ma C. Basile I. Weinstein B. Kennelly J. Bioactive novel polyphenols from the fruit of Manilkara zapota (Sapodilla) J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:983–986. doi: 10.1021/np020576x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S. Chatterjee J. Efficient extraction strategies of tea (Camellia sinensis) biomolecules. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015;52:3158–3168. doi: 10.1007/s13197-014-1487-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simelane C. Shonhai A. Shode O. Smith P. Singh M. Opoku R. Anti-Plasmodial Activity of Some Zulu Medicinal Plants and of Some Triterpenes Isolated from Them. Molecules. 2013;18:12313–12323. doi: 10.3390/molecules181012313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roqaiya M. Begum W. Majeedi F. Saiyed A. A review on traditional uses and phytochemical properties of Mimusops elengi Linn. Int. J. Tradit. Herb. Med. 2015;2:20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.-S. Shen C.-C. Hott L.-K. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of 5,7 dihydroxyflavonoids. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:843–845. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85370-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud M. Moharram F. El-Gindi M. Hassan A. Acylated flavonol glycosides from Eugenia jambolana leaves. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:1239–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00365-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Du X. Xu Y. Deng Y. Liu M. Zhao Y. Zhang B. Li X. Zhang L. Peng C. Duan Y. Yu J. Wang L. Yang K. Liu F. Jiang R. Yang X. You T. Liu X. Yang X. Bai F. Liu H. Liu X. Guddat L. Xu W. Xiao G. Qin C. Shi Z. Jiang H. Rao Z. Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. Xie W. Xue X. Yang K. Ma J. Liang W. Zhao Q. Zhou Z. Pei D. Ziebuhr J. Hilgenfeld R. Yuen K. Wong L. Gao G. Chen S. Chen Z. Ma D. Bartlam M. Rao Z. Design of Wide-Spectrum Inhibitors Targeting Coronavirus Main Proteases. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(10):1743–1752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed A. Khattab A. AboulMagd A. Hassan H. Rateb M. Zaidg H. Abdelmohsen U. Nature as a treasure trove of potential anti-SARSCoV drug leads: a structural/mechanistic rationale. RSC Adv. 2020:19790–197802. doi: 10.1039/D0RA04199H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayed A. Alhadrami H. El-Gendy A. Shamikh Y. Belbahri L. Hassan H. Abdelmohsen U. Rateb M. Microbial Natural Products as Potential Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) Microorganisms. 2020;8(970):1–17. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8070970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owis I. El-Hawary S. El Amir D. Aly M. Abdelmohsen U. Kame S. Molecular docking reveals the potential of Salvadora persica flavonoids to inhibit COVID-19 virus main protease. RSC Adv. 2020;10:19570–19575. doi: 10.1039/D0RA03582C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. Kim S. Shin D. Kim M. Inhibition of SARS-CoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020;35(1):145–151. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1690480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman M. AlAjmi M. Hussain A. Natural Compounds as Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (3CLpro): A Molecular Docking and Simulation Approach to Combat COVID-19. Chemrxiv. 2020;2 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv.12362333.v2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmohsen U. Cheng C. Viegelmann C. Zhang T. Grkovic T. Ahmed S. Quinn J. Hentschel U. Edrada-Ebel R. Dereplication strategies for targeted isolation of new antitrypanosomal actinosporins A and B from a marine sponge associated-Actinokineospora sp. Mar. Drugs. 2014;12:1220–1244. doi: 10.3390/md12031220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggag E. Elshamy A. Rabeh M. Gabr N. Salem M. Youssif K. Samir A. Muhsinah A. Alsayari A. Abdelmohsen U. Antiviral potential of green synthesized silver nanoparticles of Lampranthus coccineus and Malephora lutea. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019;14:6217–6229. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S214171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssif K. Haggag E. Elshamy A. Rabeh M. Gabr N. Seleem A. Salem M. Hussein A. Krischke M. Mueller M. Abdelmohsen U. Anti-Alzheimer potential, metabolomics profiling and molecular docking of green synthesized silver nanoparticles of Lampranthus coccineus and Malephora lutea aqueous extracts. PLoS One. 2019:1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy O. Smieško M. Searching for bioactive conformations of drug-like ligands with current force fields: how good are we? J. Cheminf. 2017;9:29. doi: 10.1186/s13321-017-0216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohning E. Levonis M. Noonan B. Schweiker S. A Practical Guide to Molecular Docking and Homology Modelling for Medicinal Chemists. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017;17:1–18. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170130110827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panche A. N. Diwan A. D. Chandra S. R. Flavonoids: an overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016;5:1–15. doi: 10.1017/jns.2015.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K. and Patel D. K., The Beneficial Role of Rutin, A Naturally Occurring Flavonoid in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: A Systematic Review and Update, Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Arthritis and Related Inflammatory Diseases, 2nd edn, 2019, pp. 457–479 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.