Abstract

Although immigrant mothers from some Latinx subgroups initially achieve healthy birth outcomes despite lower socioeconomic status, this advantage deteriorates across generations in the US. Interpersonal discrimination and acculturative stress may interact with economic hardship to predict an intergenerational cascade of emotional and biological vulnerabilities, particularly perinatal depression. Network analyses may elucidate not only how and which psychosocial experiences relate to depressive symptoms, but which symptom-to-symptom relationships emerge. This study aims to understand (1) how economic, acculturative, and discrimination stressors relate to prenatal depression and low birth weight (2); and how Latinas may respond to and cope with stressors by exploring symptom-symptom and symptom-experience relationships. A sample of 151 pregnant Latinas (predominantly foreign-born and Mexican and Central American descent) completed the Edinburgh Perinatal/Postnatal Depression Scale and psychosocial questionnaires (discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, economic hardship) during pregnancy (24–32 weeks). Birth weights were recorded from post-partum medical records. We created network models using the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion Graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator to estimate the relationship between variables. Discrimination exposure connected psychosocial stressors to depressive symptoms, particularly worry, crying, sadness, and self-blame. Discrimination also revealed a connection between acculturation and low birth weight. Furthermore, younger age of migration and greater acculturation levels were correlated to greater discrimination stress and low birth weights. Perinatal research in Latinas must account not only for measures of cultural adaptation but recognize how developmental exposures across the life span, including discrimination, may be associated with adverse health trajectories for a mother and her child.

Keywords: Latina, Prenatal Depression, Acculturative Stress, Discrimination, Network Analysis

Introduction

Depending on post-migration and socioeconomic status, Latina mothers may experience numerous psychosocial stressors such as economic hardship, acculturative stress, and discrimination (Ayón et al., 2018), thus increasing vulnerability to prenatal depression and subsequent adverse birth outcomes (D’Anna-Hernandez et al., 2015; Earnshaw et al., 2013; Novak et al., 2017). Although Mexican immigrant mothers initially achieve healthy birth outcomes despite lower socioeconomic status, this advantage deteriorates across generations in the United States (US) (de la Rosa, 2002; Gálvez, 2011; Page, 2004). In fact, greater time spent in the US has been linked to an increased prevalence of mother-child health disparities sharing stress-related pathways, particularly prenatal neuroendocrine dysfunction (D’Anna-Hernandez et al., 2012; Ruiz et al., 2007; Scholaske et al., 2018), higher levels of prenatal (Ruiz et al., 2012) and postpartum depression (Alhasanat & Giurgescu, 2017), and infants with low birth weights (de la Rosa, 2002). Most research in perinatal health has focused on cultural and behavioral explanations for this phenomenon, such as the loss of protective cultural values (Campos et al., 2008; Page, 2004). Although such research recognizes cultural strengths, this focus detracts from multiple dimensions of inequity that may drive the intergenerational cascade of emotional and biological vulnerabilities (Castañeda et al., 2015; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). Psychosocial responses to the sociocultural context of immigration, such as interpersonal discrimination and acculturative stress, may interact with economic hardship to predict prenatal depressive symptoms (Ponting et al., 2020; Santos et al., 2020) and adverse birth outcomes in Latinas (Earnshaw et al., 2013).

Acculturative stress refers to psychosocial stress induced by acculturation, the process of adapting to a host culture. Acculturative stress includes the inherent challenges of navigating a new country, such as learning new language skills. However, acculturative stress may also include additional interrelated components, such as emotional loss, psychological conflicts, and discrimination. Emotional loss may stem from social isolation, separation from loved ones, and loss of heritage culture (Hurtado-de-Mendoza et al., 2014; Pike & Crocker, 2020). Psychological conflicts may arise from shifting gender roles and ethnic identities within a discriminatory societal context (Viruell-Fuentes, 2011). Familial acculturative stress may be more closely linked to depressive symptoms for women than men (Cervantes et al., 2019), a link that may be exacerbated during pregnancy and motherhood when social support may be especially critical (Ornelas et al., 2009). In fact, acculturative stress was associated with elevated prenatal depressive symptoms in a sample of primarily immigrant Mexican women (D’Anna-Hernandez et al., 2015).

Although some components of acculturative stress may diminish with greater acculturation, discrimination persists. Among a sample of primarily US-born Mexican American women, perceived discrimination was a stronger predictor of prenatal depressive symptoms than acculturative stress or sociodemographic variables, such as income and education (t (502) = 5.44, p <.001) (Walker et al., 2012). In fact, discrimination may be recognized and felt most profoundly for women who have most integrated into US culture, as measured by length of residency in the US and English language skills (Finch et al., 2000; Flippen & Parrado, 2015). Similarly, US-born and immigrant Latinas who spent their childhood in the US were more likely to report discrimination than Latinas who immigrated to the US as adults (Pérez et al., 2008; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). As such, discrimination stress may be dose dependent. Longer periods and greater levels of exposure may accumulate to impede social and economic mobility, worsen health outcomes (Williams et al., 2019), and perpetuate a cycle of worsened physical and emotional health across generations. However, those relationships are complex and have been largely understudied.

Network theory allows us to conceptualize psychosocial stressors (acculturative stress, discrimination, economic hardship) and depressive symptoms as chains of mutually reinforcing (or inhibiting) entities in a network cascade (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). For instance, discrimination or acculturative stress may precipitate depressive symptoms, but the symptom-to-symptom cascade (e.g., sadness > worry > fatigue) may differ based on the etiology (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). Such a theoretical approach not only recognizes that symptoms differ based on precipitating factors but challenges the premise that depressive symptoms are interchangeable passive indicators of an overarching disease (Fried et al., 2017). In fact, growing evidence suggests that individual symptoms and their clinical significance differ based on sociological and societal influences. Specifically, psychometric network models have elucidated how stressful life events (Cramer et al., 2012) and motherhood (Phua et al., 2020) shape symptom-to-symptom cascades, which may inform subsequent interventions. For instance, negative self-perceptions (low self-esteem, self-blame) may be the most distressful symptoms during pregnancy and most associated with adverse birth and child developmental outcomes (Phua et al., 2020).

Although depressive symptom-to-symptom and symptom-to-biomarker relationships have been explored in pregnant Latinas using a nursing symptom science approach, symptoms were not contextualized in relation to psychosocial experiences (Santos et al., 2017). In fact, network analyses have not yet explored how Latinas may respond to and cope with psychosocial experiences although substantial evidence has entwined emotional and physical health with chronic societal stressors in Latinx populations (Vernice et al., 2020). These psychological pathways cannot be captured with depression sum-scores. The Surgeon General Report on minority mental health recommended that more epidemiological studies extend beyond mental health diagnoses and focus on symptoms and symptom clusters specific to Latinx populations (Office of the Surgeon General, 2001). A network analysis may identify which stressors and symptom pathways may be most socio-culturally relevant. By exploring the connections between symptoms and experiences, this study may generate critical and nuanced insights into maternal experiences during the prenatal period -- a period that intimately and consequentially connects two generations.

Present Study

Our present study examines psychosocial stressors, depressive symptoms, and birth outcomes through a network analysis. The purpose of this study is to understand (1) how economic, acculturative, and discrimination stressors relate to prenatal depression scores and low birth weight (2); and how Latinas may respond to and cope with stressors by exploring symptom-symptom and symptom-experience relationships. Given the well-established evidence of worsening Latina perinatal heath across length of residency in the US, this study will also explore whether prevalence and patterns of symptoms and psychosocial experiences differ based on age of arrival to the US.

Methods

Participants

Participants included the full sample of 151 women who participated in a parent study to evaluate the association between discrimination exposure and psychological distress (Santos et al., 2018). The sample was recruited from maternity clinics in a county health department in North Carolina between May 2016 and March 2017. Healthy pregnant Latina women were enrolled in the study. Inclusion criteria included: (1) 18–45 years old, (2) Spanish- or English-speaking, (3) carrying a singleton pregnancy, (4) available for follow-up at 6 weeks postpartum. Exclusion criteria were: (1) currently experiencing severe depressive symptoms as determined by psychiatric interview, (2) history of psychotic or bipolar disorder, or receiving psychotropic therapy, (3) substance dependence in the last two years, (4) fetal anomaly, or (5) life-threatening conditions. Exclusion criteria were chosen to minimize confounders and control for severe mood symptoms prior to the study time frame.

The mean age of the participants was 27.7 years (standard deviation [SD] = 6.4). Most participants were foreign-born (85%), reported an income of less than $30,000 a year (90%), and were married or living with a partner (77%). Participants were predominantly of Mexican (56%), Honduran (17%), and El Salvadorian (13%) origin. Sample demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics N=151

| Sociodemographic | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign-born | 122 | 85 | ||

| Age of migration (foreign-born) | 18.55 | 1.46 | ||

| Income | ||||

| ≤ $15,000 | 59 | 39 | ||

| $15,000 -- $29,999 | 77 | 51 | ||

| $30,000 - $39,999 | 14 | 9 | ||

| >= $40,000 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/ Partner | 112 | 77 | ||

| Single | 39 | 26 | ||

| Maternal education | ||||

| 0 – 8th grade | 55 | 36 | ||

| Some high school | 43 | 28 | ||

| Graduated high school | 31 | 21 | ||

| Some college | 12 | 8 | ||

| Maternal education | n | % | M | SD |

| 4-year college degree | 10 | 7 | ||

| Work outside home | ||||

| Yes | 49 | 32 | ||

| No | 102 | 68 | ||

| Health insurance | ||||

| None | 102 | 68 | ||

| Medicare/Medicaid | 47 | 31 | ||

| Private | 2 | 1 | ||

| Maternal age | 27.7 | 6.4 | ||

| Number of children | ||||

| 0 | 44 | 29 | ||

| 1 | 33 | 22 | ||

| ≥2 | 74 | 59 |

Data Collection

Data were collected during pregnancy because mothers may experience increased psychological distress due to nature of pregnancy, social and family relationships, and increased need to access medical services (Biaggi et al., 2016). Additionally, chronic maternal stressors, anxiety, and depressive symptoms are well-established risk factors for adverse maternal and child health outcomes (Dunkel Schetter & Tanner, 2012).

Trained bilingual and bicultural research assistants assessed mothers for eligibility during routine prenatal visits at the health department. Women who demonstrated interest in the study were given information about the study. Enrollment was coordinated with the healthcare providers of the maternity clinics and took place before or after the prenatal care visit. We were able to recruit the target number of participants. Data collection was completed in English or Spanish, depending on participant’s preference, by a research assistant at the prenatal visit (24–32-weeks gestation) and at 4–6 weeks postpartum. Measures used in this study were validated in English and Spanish. A psychiatrist was part of the research team and was available to assess the participant’s need for a referral. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study. Full details on recruitment procedures have been previously described (Santos et al., 2018).

Measures

Prenatal Depressive Symptoms

The widely used 10-item Edinburgh Perinatal/Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screens women for postnatal (Cox et al., 1987) and antenatal (Alvarado et al., 2015) depressive symptoms as well as anxiety. Depressive symptoms occurring during the past seven days are reported on a four-point Likert scale (0=No, never, to 3=Yes, most of the time). The convergent validity with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-I) is rho = 0.850 (Alvarado et al., 2015). The full scale has been validated with English-speaking (Yonkers et al., 2001) and Spanish-speaking Latinas living in the US (Hartley et al., 2014). In this sample, the standardized Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the full EPDS was 0.79 during pregnancy. Items 3–5 (EPDS-3A) may also be used to screen for perinatal anxiety, as previously described (Matthey, 2008).

Acculturation

The 27-item Bidimensional Acculturation Scale (BAS) (Marín & Gamba, 1996) was used to measure the degree to which individuals have adapted to U.S. culture, as measured by three subscales: language use, language proficiency, and electronic media. Sample questions include, “How often do you think in English?” and “How well do you understand TV programs in Spanish?” and uses a 1–4 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher frequency or better ability (1=Almost Never to 4=Very Well). The scale has been tested for reliability (alpha .90–.96) and validated in English and Spanish. (Marín & Gamba, 1996). In this sample, the standardized Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for item consistency was 0.85 during pregnancy.

Psychosocial Stressors

Discrimination:

The 9-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS) (Williams et al., 1997) was used to measure routine, day-to-day, experiences of discrimination. The EDS is a widely used measure of perceived discrimination and is validated in Spanish (Park et al., 2018). It correlates with measures of institutional racial discrimination and interpersonal prejudice (Krieger et al., 2005) and does not prime the subjects to think about race (Deitch et al., 2003). Likert response scale for frequencies range from 0 (“never”) to 5 (“almost every day”). Higher scores indicate a higher frequency of perceived discrimination. In this sample, the standardized Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for item consistency was 0.88 during pregnancy.

Acculturative Stress:

The 9-item Acculturative Stress Scale (ACS) (Gil et al., 1994) was used to assess the psychological impact and emotional strain of acculturation (i.e., process of adapting to the host culture). These stressful experiences include language stress (ACS items 1–2), psychological conflicts (ACS items 3–6), and discrimination stress (ACS items 7–9). Participants report the frequency of certain emotions and experiences regarding acculturation to the US in the past year on a Likert scale of 1–5 (1=Not at all to 5=Almost always). Higher scores indicate a greater degree of stress. In this sample, the standardized Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for item consistency was 0.69 during pregnancy.

Economic Hardship:

The 6-item Economic Hardship measure (Zilanawala & Pilkauskas, 2012) was used to assess objective experiences of economic hardship, such as “Were you unable to pay a full gas or electricity bill?” A sum score from 0–6 is calculated based on responses. Higher scores indicate higher levels of economic hardship.

Low Birth Weight

Data on birth weight were retrieved from hospital delivery records. Low birth weight was determined based on the World Health Organization’s definition of low birth weight: an infant born less than five pounds eight ounces regardless of gestational age (Cutland et al., 2017).

Data Analysis

Except for birth outcomes, our network models included prenatal measures collected at 24 to 32-weeks gestation from 151 mothers. Regularized partial correlation network models can graphically estimate a correlation matrix in which each variable (symptom or psychosocial experience) is a node and each correlation is an edge (Epskamp et al., 2012).

We created network models using Extended Bayesian Information Criterion Graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (EBICglasso) to estimate the relation between variables (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). The EBICglasso estimates the partial correlations between all variables, shrinks small edges, and sets small edges to zero to limit spurious (false positive) edges. Because polychoric correlations may lead to less stable networks at lower sample sizes, we used Pearson’s correlations (Epskamp, 2020). We excluded missing values pairwise, set the tuning parameter to 0.5, and bootstrapped the network 1000 times. Non-parametric bootstrapping allows us to evaluate edge-weight variability and the subsequent stability of estimated network connections (Epskamp et al., 2018). Bootstrap confidence intervals (95% CI) for networks are provided in the Supplementary materials (Supplementary Figure S2 and S3). For this study, we employed network analysis as an exploratory approach to generate hypotheses rather than measure statistical significance between variables. We used JASP (Version 0.14.1) computer software to draw models, which uses the R package, qgraph 1.6.3 and the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm to visualize the networks (Epskamp et al., 2012). Finally, to evaluate whether the prevalence and patterns of psychosocial experiences and depressive symptoms differed based on age of migration, we conducted Pearson correlation and descriptive analyses.

Results

Networks of Depressive Symptoms, Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, Economic Hardship, and Low Birth Weight

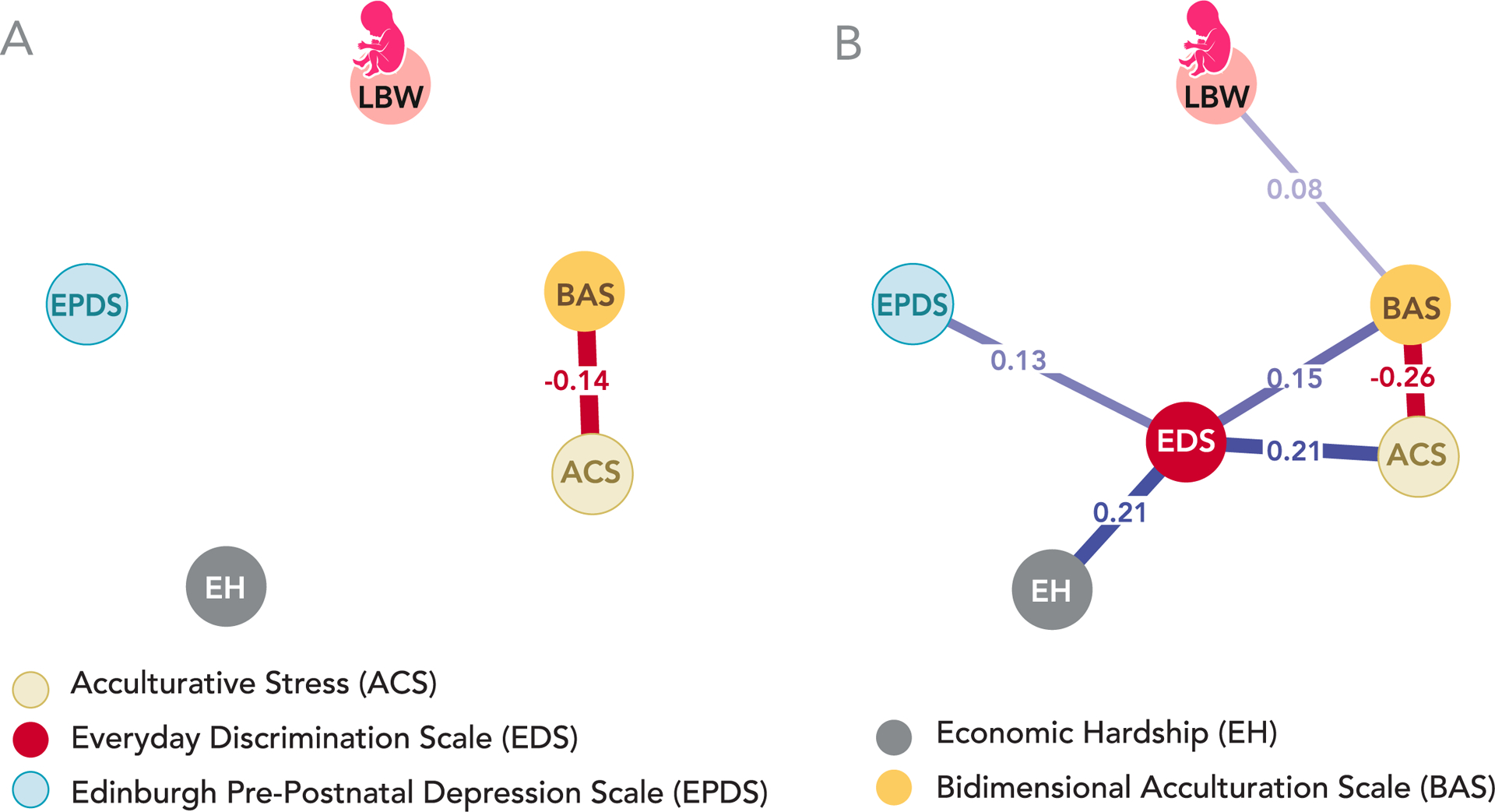

First, we aimed to broadly understand how psychosocial stressors related to prenatal depression and low birth weight. Therefore, we included prenatal depression score (EPDS), low birth weight (LBW), acculturative stress (ACS), acculturation (BAS), everyday discrimination (EDS), and economic hardship (EH) into the model (see Figure 1). The network initially shows only one association, in which acculturation (BAS) is negatively correlated with acculturative stress (ACS) (r = −0.144) (see Figure 1a). However, when EDS is introduced into the model, we observe that discrimination served as a bridge linking all experiences and low birth weight outcomes (see Figure 1b). Centrality and stability for these networks are provided in Supplementary Figures S1 and S2. Partial correlation coefficients for all edges (connections) in Figure 1 are reported in the Supplementary Tables S1–S2.

Figure 1.

Network of Depressive Symptoms, Discrimination and Acculturative Stress, Economic Hardship, and Low Birth Weight. Edges, the connections between nodes, represent the strength of the relationship between nodes in which thicker and darker lines represent stronger relationships. Blue edges represent positive correlations, whereas red edges represent negative correlations. Partial correlation coefficients are shown on all edges. Panel A: Network of prenatal depression (EPDS), low birth weight (LBW), acculturative stress (ACS), acculturation (BAS), and economic hardship (EH) Panel B: Introducing the discrimination node (EDS) to the model bridged all experiences and low birth weight outcomes together (n = 151).

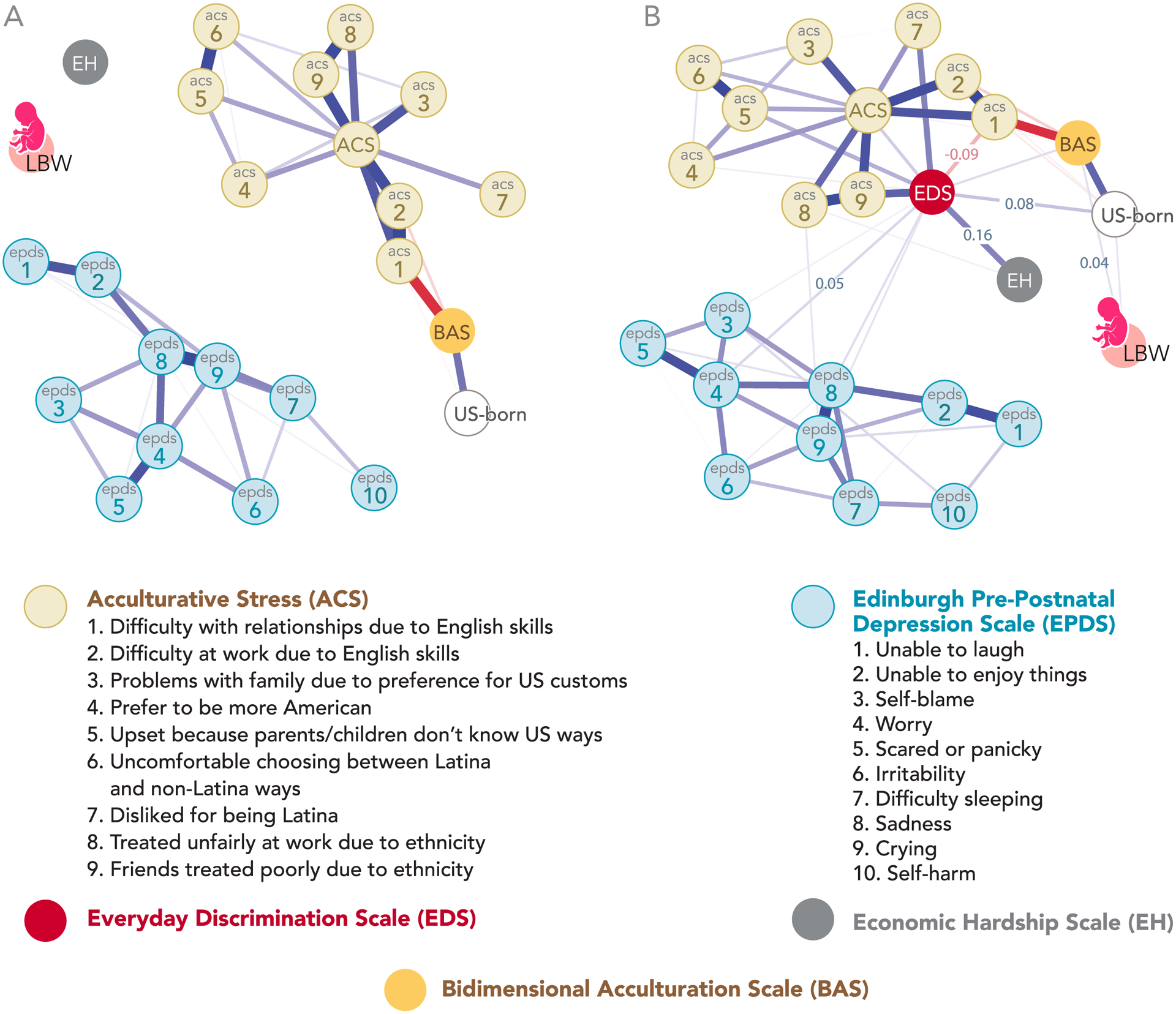

Networks of Symptom-Symptom and Symptom-Experience Relationships and Low Birth Weight

Second, we aimed to understand how Latinas may respond to and cope with psychosocial stressors by exploring symptom-to-symptom and symptom-to-experience relationships. Therefore, we introduced individual depressive symptoms and acculturative stressors into the network model (see Figure 2a). As in the previous model, we observed that introducing the discrimination node connected acculturative stressors to depressive symptoms and enabled connections for economic hardship and low birth weight (see Figure 2b). Discrimination correlated to the depressive symptoms, “worry” (EPDS4) (r = 0.050), “crying” (EPDS9) (r = 0.032), “sadness” (EPDS8) (r = 0.042), and “self-blame” (EPDS3) (r = 0.018). Additionally, these symptoms are all directly correlated to “worry” (EPDS4).

Figure 2.

Network of Symptom-Symptom and Symptom-Experience Relationships and Low Birth Weight. Edges, the connections between nodes, represent the strength of the relationship between nodes in which thicker and darker lines represent stronger relationships. Blue edges represent positive correlations, whereas red edges represent negative correlations. Partial correlation coefficients are shown along selected edges. Panel A: Prenatal depressive symptoms (EPDS) and acculturative stressors (ACS) are separate clusters. Panel B: Introducing the discrimination node (EDS) to the model bridged acculturative stressors to depressive symptoms and enabled connections for economic hardship and low birth weight (n = 151)

US-born status and acculturation correlated with low birth weight (r = 0.029; r = 0.038) and discrimination (r = 0.075; r = 0.041). In other words, both US-born and more acculturated participants were more likely to have an infant with low birth weight and to report discrimination.

Acculturative stressors were closely tied to discrimination, whereby more than half the acculturative stress nodes directly linked to discrimination. However, “difficulty getting along with others due to poor English proficiency” (ACS1) was negatively correlated with discrimination (r = −0.093). “Unfair treatment at work due to ethnicity” (ACS8) was the only acculturative stressor that correlated directly to either economic hardship (r = 0.019) or the depressive symptom, “crying” (EPDS9) (r = 0.031).

Partial correlation coefficients for all edges (connections) in Figure 2b are reported in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Table S3). Stability checks for these networks are provided in the Supplementary Figure S3.

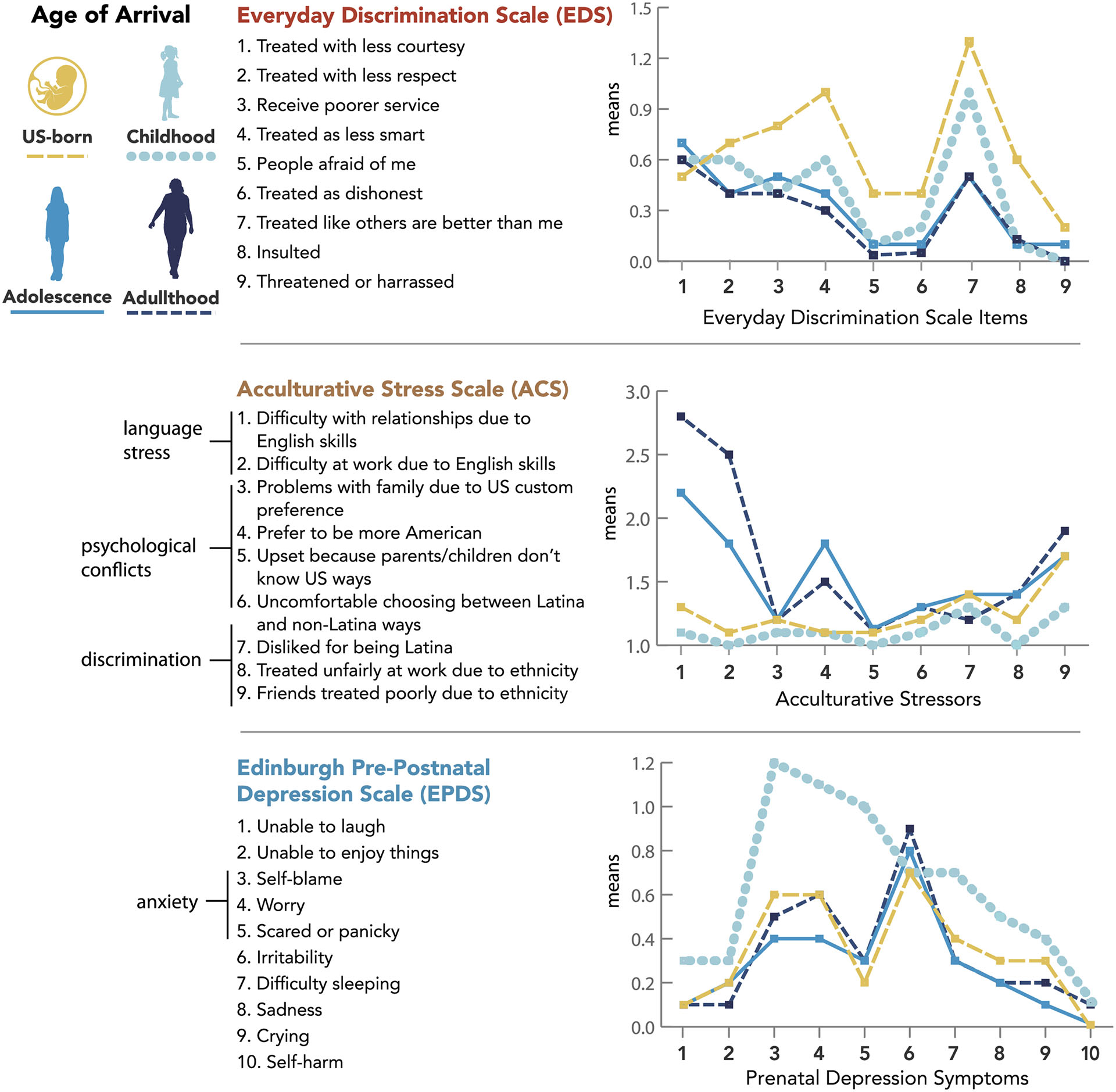

Correlation Patterns for Age of Arrival to US: Everyday Discrimination, Prenatal Depressive Symptoms, and Acculturative Stress

Since our network analysis indicated that acculturation and US-born status were related to psychosocial stressors, we explored whether prevalence and patterns of symptoms and psychosocial stressors differed based on age of arrival to the US. Older age of arrival was negatively correlated with everyday discrimination (r = −0.199, 95% CI [−0.348, −0.041]) and positively correlated with acculturative stress (r = 0.443, 95% CI [0.305, 0.563]). To further explore these findings, participants were then categorized based on the developmental period during which they arrived in the US (U.S. born, arrival during childhood, adolescence, adulthood). US-born participants were more likely to have health insurance and higher levels of education, to work outside the home, and to be younger (Supplemental Table S4).

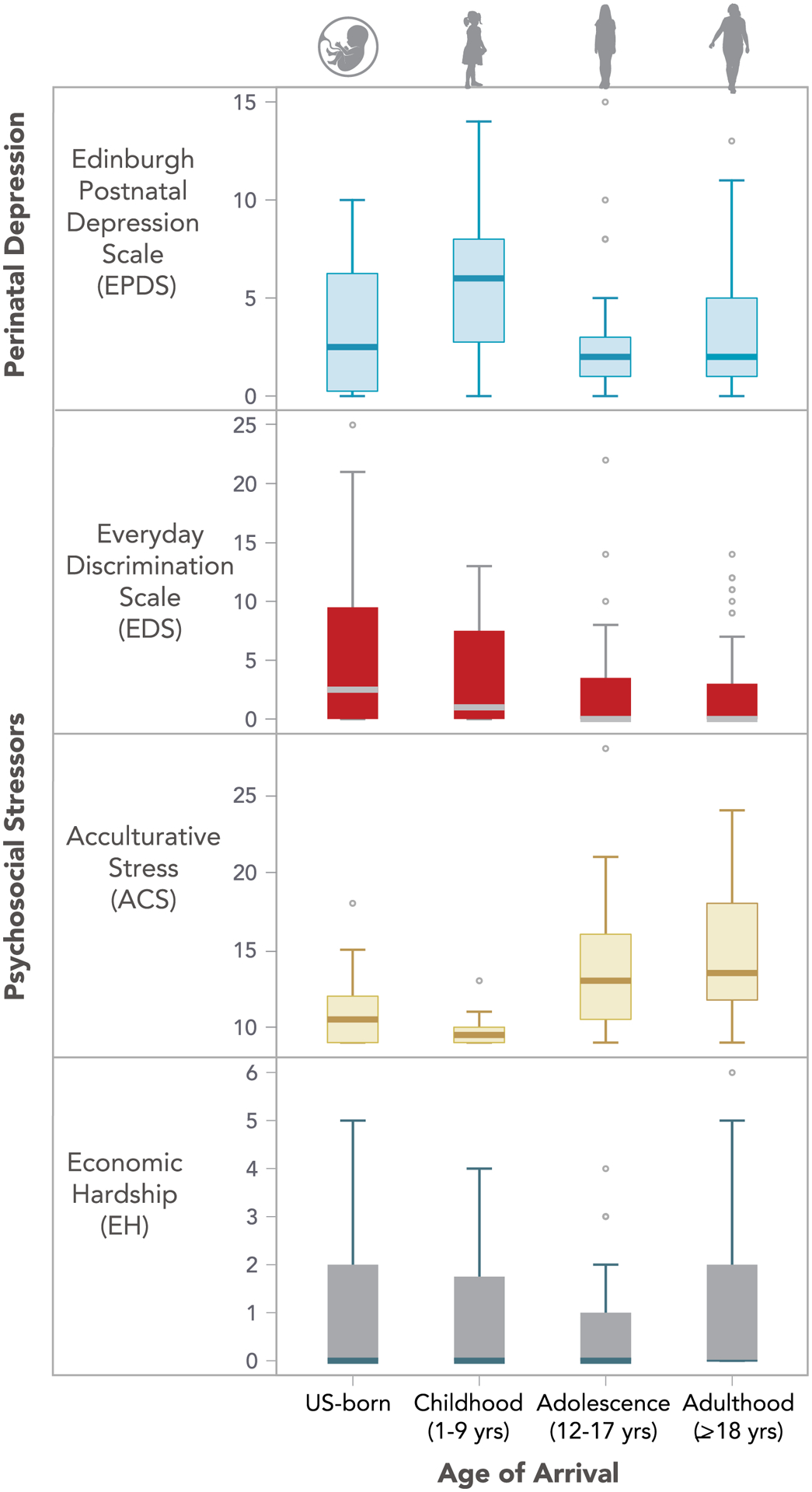

To visually display differences among the groups, we plotted mean responses of depressive symptoms, everyday discrimination items, and acculturative stressors by developmental periods at age of arrival (see Figure 3). US-born participants reported the highest levels of everyday discrimination. Participants who spent their childhood in US (US and foreign-born) were most likely to report “people act as if they think you are not smart” (EDS4) and “people act as if they’re better than you are” (EDS7). For prenatal depression, prevalence and pattern of symptoms differed only for participants who arrived in the US as young children; this group reported noticeably higher levels of all anxiety-related symptoms, “self-blame” (EPDS3), “worry” (EPDS4), and “scared” (EPDS5). For acculturative stress, participants who arrived during adolescence and adulthood reported higher levels of language stress (ACS 1–2). Unlike everyday discrimination, however, group responses did not differ widely on discrimination-based items of the Acculturative Stress Scale (ACS 7–9). Finally, Figure 4 demonstrates how stressors and summed depression scores differed among groups. Participants who migrated to the US during childhood reported more depressive symptoms than other groups, and self-reported discrimination increased incrementally with longer residency in the US.

Figure 3.

Age of Arrival: Everyday Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Depressive Symptoms. US-born participants (n=22); Age of arrival during childhood (n=14; 1–9 years old); adolescence (n=39; 12–17 years old); adulthood (n=76; ≥ 18 years old). No participants arrived at 10–11 years old.

Figure 4.

Box Plots for Age of Arrival: Depressive Symptoms, Everyday Discrimination, Acculturative Stress, and Economic Hardship

Discussion

Well-established evidence has indicated that perinatal emotional and physical health deteriorates across generations of Latina women living in the US, particularly for women of Mexican descent, but the underlying psychosocial mechanisms have remained elusive (de la Rosa, 2002; Fox et al., 2015; Osypuk et al., 2010). Scholars have suggested that the loss of protective cultural values (Page, 2004) and worsening health behaviors (Cobas et al., 1996; Giuntella, 2017) may contribute to the decline in health over time. Behavioral explanations, however, do not tell the full story and can lead to victim blaming (Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012). We employed a network approach to understand how depressive symptoms and low birth weight outcomes may interconnect with psychosocial experiences. Our results indicate that discrimination was the bridge that bound together psychosocial stressors, low birth weights, and depressive symptoms, suggesting that discrimination is interwoven into all these experiences. Furthermore, younger age of migration and greater acculturation levels were correlated to greater discrimination stress and low birth weights. At the symptom level, worry emerged as a particularly salient symptom, followed by sadness, crying, and self-blame.

Our analyses suggest that worry may be an important precipitating symptom for Latinas experiencing discrimination, regardless of acculturation levels or post-migration generation. For pregnant Latina women, discrimination may provoke anxiety-related symptoms (worry, self-blame), which precede other depressive symptoms. Similarly, pervasive worry about racism emerged as a central theme in a qualitative study with child-bearing Black women (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009), suggesting generalizability of our findings to other populations. Specifically, Black women ruminated about past discrimination experiences and felt vigilant about experiencing future racism (Nuru-Jeter et al., 2009). The sociopolitical context of this study may have also heightened the relationship between anxiety-related symptoms and discrimination. Specifically, data were collected during the 2016 presidential election (May 2016 to March 2017), which included inflammatory rhetoric about immigrants from Latin America. Interestingly, participants who migrated to the US as young children were the most likely to endorse anxiety-related depressive symptoms. Although they have grown up in the US, like US-born participants, they may not have been documented citizens and, thus, may have been more vulnerable to anti-immigrant sentiment. A prior study also found that Mexican American women who spent their childhood in the US reported significantly higher levels of postpartum depressive symptoms than women who migrated as adults (Heilemann et al., 2004). Yet limited research has explored perinatal depressive symptoms in women who have migrated to the US as young children, in part, because the singular focus on acculturation scales has precluded a life course approach to understanding generational perinatal patterns.

Depressive symptoms were not precipitated by economic hardship, per se, but by the stigma and inferior treatment associated with poverty, particularly among women who spent their childhood in the US. Furthermore, after the discrimination node was added to the model, unfair treatment at work due to ethnicity correlated directly with economic hardship and the depressive symptom, crying. Immigrant mothers who are undocumented may feel unable to advocate for themselves due to fear of losing employment or of deportation (Non et al., 2019). Interestingly, participants who reported poor English proficiency were less likely to report discrimination and subsequent depression. This finding suggests that understanding verbal forms of discrimination (e.g., name calling, overheard comments) may, in part, contribute to the relationship between greater acculturation and increased self-reported discrimination. Qualitative research in Mexican American women across generations has also suggested that explicitly identifying subtle forms of discrimination is a learned process that may be more difficult to quantify among first generation immigrants (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Second generation women, however, may grow up “with an implicit sense of stigmatized difference,” which may originate in early childhood (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007).

Growing up in the US during childhood determined the prevalence and pattern of responses on the Everyday Discrimination Scale. However, participants reported more similar levels of discrimination on the Acculturative Stress Scale’s discrimination-based questions, irrespective of post-migration status. The Acculturative Stress Scale asks broad questions about “bad” or “unfair” treatment, suggesting that recognizing ethnic-based discrimination in general is not necessarily limited to women who grow up in the US. The Everyday Discrimination Scale, however, asks about a specific subset of experiences associated with inferior treatment, which may require familiarization with a country’s societal hierarchy. Although immigrants from Latin America may be familiar with discrimination based on skin color (i.e., colorism) and social class in their country of origin, well-defined racial categories may be uniquely salient in the US (Dixon, 2019). Greater awareness of US -based ethnic/racial hierarchies may result in a “specific process of stigmatization” (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2016, p. 224), particularly for families attempting to create a sense of belonging in the US. Over time, women may psychologically and biologically internalize these negative perceptions, with potentially far-reaching consequences for maternal and child health.

Lifetime experiences of discrimination, including witnessing a caregiver discriminated against, have been linked to having a low birth weight infant (Larrabee Sonderlund et al., 2021). Although low birth weights were more closely tied to growing up in the US as a young child than with prenatal discrimination, the discrimination node indirectly enabled the connection between greater acculturation and low birth weight. Similarly, a prior paper based on the parent study found that higher levels of DNA methylation of TNF-α, a key regulator of inflammatory processes, was correlated to greater levels of acculturation rather than self-reported discrimination (Sluiter et al., 2020); methylation of inflammation-related genes, however, increased vulnerability to depressive symptomology and discrimination stress. Specifically, chronic discrimination and systemic inflammation may form a reinforcing feedback loop (Cuevas et al., 2020). Everyday experiences of discrimination provoke emotional (depression, anxiety) and inflammatory responses. Over time, chronic inflammation may increase sensitivity to future experiences of social threat, including discrimination (Slavich, 2020). This cycle may begin in early childhood, whereby early psychosocial stress may become biologically embedded through epigenetic mechanisms (Miller et al., 2011). The resulting proinflammatory state may underlie multiple stress-related health conditions, including depressive symptomology and obstetric complications during the child-bearing years (Larrabee Sonderlund et al., 2021). In this way, childhood exposures as women arrive and acculturate to the US may increase not only biological vulnerability to depressive symptoms but vulnerability to having an infant with low birth weight. In fact, a mother’s childhood environment may be as relevant as her own child’s environment for predicting emotional and biological risk and resilience (Dunn et al., 2019; Gillespie et al., 2019; Miller et al., 2017). These linked experiences may initiate a generational cascade of poor health outcomes and perpetuate the cycle of poverty.

Limitations

Many parameters are estimated in the network models, as previously described (Santos et al., 2017). Even though our findings based on 151 mothers showed at least moderate stability and accuracy, results should be considered exploratory in nature. Thus, we did not provide measures of statistical significance for the network models due to the limited sample size and the exploratory nature of this study. The interpretation of the associations themselves is informative on their own and avoids misuses of p values in complex analysis like network models; moving beyond p-values has been recommended by several disciplines, including nursing (Hayat et al., 2019). Our findings may generate important hypotheses for future research examining patterns of depressive symptoms and psychosocial stressors post-migration. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to identify how discrimination and acculturative stress experiences may relate to symptom-to-symptom relationships in the prenatal period. The sample was from one metropolitan area in North Carolina, which may limit generalizability to other regions of the US. Discrimination experiences and acculturation-health relationships among Latinas likely differ based on socioeconomic status, country-of-origin, and historical socio-political context. Furthermore, although the Everyday Discrimination Scale has been widely used and is considered valid and reliable, self-reported discrimination, nonetheless, relies on participant’s willingness to report discrimination.

Clinical and Research Implications

Our network theory analysis suggests that external events, including psychosocial stressors, activate a cascade of depressive symptoms in this population, which over time, may result in self-sustaining depressive states. The discrimination node linked economic hardship and acculturative stress to depressive symptoms. Social support is a well-established protective factor for mother-child health in Latinas (Luecken et al., 2013), which may mitigate psychosocial stress by counteracting the social exclusion underlying both discrimination and acculturative stress. Although brief nurse-led psycho-education programs may mitigate postpartum depressive symptoms in the general population (Fisher et al., 2010), vulnerable families may benefit from interventions that explicitly integrate social support, such as community-based volunteer home visiting (Grace et al., 2019). In fact, the company of other women with similar experiences may create a sense of community and belonging (Small et al., 2011). For instance, Mexican immigrant mothers of young children have found solace in immigrant parenting support groups, primarily because it enables mothers to rebuild social networks and access community resources (Non et al., 2019). Group counseling or mentoring programs with local bi-cultural and bilingual mothers have also been suggested (Non et al., 2019). Furthermore, a midwife-designed intervention that integrated instrumental and emotional social support, as well as interpersonal respect and empowerment, helped mitigate health disparities in birth outcomes for both Black and Latina mothers (Visionary Vanguard Group Inc., 2017).

In addition to identifying interpersonal and community levels of social support, future research must also continue to identify how community and macro-levels of discrimination contribute to mother-child health. For instance, structural discrimination, such as exclusionary immigrant policies, have been associated with heightened stress, parental distress, increased food insecurity,(Perreira & Pedroza, 2019; Toomey et al., 2014; Vernice et al., 2020) and low birth weights in infants of immigrant (Tome et al., 2021; Torche & Sirois, 2018) and US-born Latina mothers (Novak et al., 2017). Future perinatal research in Latinas must account not only for measures of cultural adaptation but recognize how developmental exposures across the life span, including multiple ecological levels of discrimination, may be associated with adverse health trajectories for a mother and her child.

Conclusion

This study adds to accumulating evidence linking discrimination to depressive symptoms during the perinatal period. Well-established epidemiological evidence indicates that Mexican immigrant women initially defy the odds by giving birth to healthy infants despite sociodemographic factors associated with poorer health, such as lower levels of education, health insurance, and income. Across length of residency in the US, however, a mother and her infant’s health may begin to align with or become worse than her current socioeconomic status, an outcome that should not be inevitable. If society continues to racialize Latinx immigrants and their children, “it is not immigrant families but those of us who receive them who are responsible for diluting the nation’s identity and promise” (Gálvez, 2011, p. 168). Future research should identify and address how discrimination may shape emotional and biological health across generations through social and economic opportunities and experiences of belonging and exclusion.

Supplementary Material

Funding Information

This work was supported by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award, North Carolina Translational & Clinical Sciences Institute (UL1TR001111; #550KR131619), the Senich Innovation Award and the SPARK pilot program from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing, and the Caroline H. and Thomas S. Royster Fellowship

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Echeverría SE, & Flórez KR (2016). Latino Immigrants, Acculturation, and Health: Promising New Directions in Research. Annu Rev Public Health, 37, 219–236. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhasanat D, & Giurgescu C (2017, Jan/Feb). Acculturation and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms among Hispanic Women in the United States: Systematic Review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs, 42(1), 21–28. 10.1097/nmc.0000000000000298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado R, Jadresic E, Guajardo V, & Rojas G (2015, 2015/August/01). First validation of a Spanish-translated version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) for use in pregnant women. A Chilean study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 18(4), 607–612. 10.1007/s00737-014-0466-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Messing JT, Gurrola M, & Valencia-Garcia D (2018, Jun). The Oppression of Latina Mothers: Experiences of Exploitation, Violence, Marginalization, Cultural Imperialism, and Powerlessness in Their Everyday Lives. Violence Against Women, 24(8), 879–900. 10.1177/1077801217724451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, & Pariante CM (2016, Feb). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord, 191, 62–77. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, & Cramer AOJ (2013). Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos B, Schetter CD, Abdou CM, Hobel CJ, Glynn LM, & Sandman CA (2008, Apr). Familialism, social support, and stress: positive implications for pregnant Latinas. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 14(2), 155–162. 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young ME, Beyeler N, & Quesada J (2015, Mar 18). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health, 36, 375–392. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Gattamorta KA, & Berger-Cardoso J (2019, Feb). Examining Difference in Immigration Stress, Acculturation Stress and Mental Health Outcomes in Six Hispanic/Latino Nativity and Regional Groups. J Immigr Minor Health, 21(1), 14–20. 10.1007/s10903-018-0714-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobas JA, Balcazar H, Benin MB, Keith VM, & Chong Y (1996, Mar). Acculturation and low-birthweight infants among Latino women: a reanalysis of HHANES data with structural equation models. Am J Public Health, 86(3), 394–396. 10.2105/ajph.86.3.394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, & Sagovsky R (1987, Jun). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer AO, Borsboom D, Aggen SH, & Kendler KS (2012, May). The pathoplasticity of dysphoric episodes: differential impact of stressful life events on the pattern of depressive symptom inter-correlations. Psychol Med, 42(5), 957–965. 10.1017/s003329171100211x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, Ong AD, Carvalho K, Ho T, Chan SWC, Allen JD, Chen R, Rodgers J, Biba U, & Williams DR (2020, Oct). Discrimination and systemic inflammation: A critical review and synthesis. Brain Behav Immun, 89, 465–479. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutland CL, Lackritz EM, Mallett-Moore T, Bardají A, Chandrasekaran R, Lahariya C, Nisar MI, Tapia MD, Pathirana J, Kochhar S, & Muñoz FM (2017, Dec 4). Low birth weight: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine, 35(48 Pt A), 6492–6500. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna-Hernandez KL, Aleman B, & Flores AM (2015, May 1). Acculturative stress negatively impacts maternal depressive symptoms in Mexican-American women during pregnancy. J Affect Disord, 176, 35–42. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna-Hernandez KL, Hoffman MC, Zerbe GO, Coussons-Read M, Ross RG, & Laudenslager ML (2012, Apr). Acculturation, maternal cortisol, and birth outcomes in women of Mexican descent. Psychosom Med, 74(3), 296–304. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318244fbde [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa IA (2002, Fall). Perinatal outcomes among Mexican Americans: a review of an epidemiological paradox. Ethn Dis, 12(4), 480–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Barsky A, Butz RM, Chan S, Brief AP, & Bradley JC (2003). Subtle Yet Significant: The Existence and Impact of Everyday Racial Discrimination in the Workplace. Human Relations, 56(11), 1299–1324. 10.1177/00187267035611002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon AR (2019, 2019/March/01/). Colorism and classism confounded: Perceptions of discrimination in Latin America. Social Science Research, 79, 32–55. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel Schetter C, & Tanner L (2012, Mar). Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 25(2), 141–148. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Soare TW, Zhu Y, Simpkin AJ, Suderman MJ, Klengel T, Smith A, Ressler KJ, & Relton CL (2019, May 15). Sensitive Periods for the Effect of Childhood Adversity on DNA Methylation: Results From a Prospective, Longitudinal Study. Biol Psychiatry, 85(10), 838–849. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.12.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Lewis JB, Stasko EC, Tobin JN, Lewis TT, Reid AE, & Ickovics JR (2013, Feb). Maternal experiences with everyday discrimination and infant birth weight: a test of mediators and moderators among young, urban women of color. Ann Behav Med, 45(1), 13–23. 10.1007/s12160-012-9404-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S (2020). Bootnet version 1.4. Retrieved July 1, 2021 from http://psychonetrics.org/2020/05/13/bootnet-version-1-4/

- Epskamp S, Borsboom D, & Fried EI (2018, Feb). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods, 50(1), 195–212. 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, & Borsboom D (2012, 2012-May-24). qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. 2012, 48(4), 18. 10.18637/jss.v048.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, & Fried EI (2018, Dec). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods, 23(4), 617–634. 10.1037/met0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, & Vega WA (2000, Sep). Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav, 41(3), 295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JR, Wynter KH, & Rowe HJ (2010, Jul 23). Innovative psycho-educational program to prevent common postpartum mental disorders in primiparous women: a before and after controlled study. BMC Public Health, 10, 432. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA, & Parrado EA (2015, Dec). Perceived discrimination among Latino immigrants in new destinations: The case of Durham, NC. Sociol Perspect, 58(4), 666–685. 10.1177/0731121415574397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox M, Entringer S, Buss C, DeHaene J, & Wadhwa PD (2015, Jul). Intergenerational transmission of the effects of acculturation on health in Hispanic Americans: a fetal programming perspective. Am J Public Health, 105 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), S409–423. 10.2105/ajph.2015.302571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried EI, van Borkulo CD, Cramer AO, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, & Borsboom D (2017, Jan). Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, 52(1), 1–10. 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez A (2011). Patient citizens, immigrant mothers : Mexican women, public prenatal care, and the birth-weight paradox. New Brunswick, NJ: : Rutgers University Press, c2011. http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unc/detail.action?docID=858959 https://catalog.lib.unc.edu/catalog/UNCb8079549 [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Vega WA, & Dimas JM (1994). Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(1), 43–54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SL, Cole SW, & Christian LM (2019, Aug). Early adversity and the regulation of gene expression: Implications for prenatal health. Curr Opin Behav Sci, 28, 111–118. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuntella O (2017, Jul). Why does the health of Mexican immigrants deteriorate? New evidence from linked birth records. J Health Econ, 54, 1–16. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace R, Baird K, Elcombe E, Webster V, Barnes J, & Kemp L (2019, Nov 21). Effectiveness of the Volunteer Family Connect Program in Reducing Isolation of Vulnerable Families and Supporting Their Parenting: Randomized Controlled Trial With Intention-To-Treat Analysis of Primary Outcome Variables. JMIR Pediatr Parent, 2(2), e13023. 10.2196/13023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley CM, Barroso N, Rey Y, Pettit JW, & Bagner DM (2014, Dec). Factor structure and psychometric properties of english and spanish versions of the edinburgh postnatal depression scale among Hispanic women in a primary care setting. J Clin Psychol, 70(12), 1240–1250. 10.1002/jclp.22101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat MJ, Staggs VS, Schwartz TA, Higgins M, Azuero A, Budhathoki C, Chandrasekhar R, Cook P, Cramer E, Dietrich MS, Garnier-Villarreal M, Hanlon A, He J, Hu J, Kim M, Mueller M, Nolan JR, Perkhounkova Y, Rothers J, Schluck G, Su X, Templin TN, Weaver MT, Yang Q, & Ye S (2019). Moving nursing beyond p < 0.05. Research in Nursing & Health, 42(4), 244–245. 10.1002/nur.21954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilemann M, Frutos L, Lee K, & Kury FS (2004, Jan). Protective strength factors, resources, and risks in relation to depressive symptoms among childbearing women of Mexican descent. Health Care Women Int, 25(1), 88–106. 10.1080/07399330490253265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Gonzales FA, Serrano A, & Kaltman S (2014, Mar). Social isolation and perceived barriers to establishing social networks among Latina immigrants. Am J Community Psychol, 53(1–2), 73–82. 10.1007/s10464-013-9619-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inc., V. V. G. (2017). Community-Based Maternity Center, Final Evaluation Report. Retrieved June 30 2021, from http://www.commonsensechildbirth.org/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/The-JJ-Way%C2%AE-Community-based-Maternity-Center-Evaluation-Report-2017-1.pd

- Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, & Barbeau EM (2005, Oct). Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med, 61(7), 1576–1596. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee Sonderlund A, Schoenthaler A, & Thilsing T (2021, Feb 4). The Association between Maternal Experiences of Interpersonal Discrimination and Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(4). 10.3390/ijerph18041465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, & Gamba RJ (1996). A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18(3), 297–316. 10.1177/07399863960183002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S (2008). Using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to screen for anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety, 25(11), 926–931. 10.1002/da.20415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011, Nov). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychol Bull, 137(6), 959–997. 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Culhane J, Grobman W, Simhan H, Williamson DE, Adam EK, Buss C, Entringer S, Kim KY, Felipe Garcia-Espana J, Keenan-Devlin L, McDade TW, Wadhwa PD, & Borders A (2017, Oct). Mothers’ childhood hardship forecasts adverse pregnancy outcomes: Role of inflammatory, lifestyle, and psychosocial pathways. Brain Behav Immun, 65, 11–19. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Non AL, León-Pérez G, Glass H, Kelly E, & Garrison NA (2019, May). Stress across generations: A qualitative study of stress, coping, and caregiving among Mexican immigrant mothers. Ethn Health, 24(4), 378–394. 10.1080/13557858.2017.1346184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak NL, Geronimus AT, & Martinez-Cardoso AM (2017, Jun 1). Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol, 46(3), 839–849. 10.1093/ije/dyw346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, Jones CP, & Braveman P (2009, Jan). “It’s the skin you’re in”: African-American women talk about their experiences of racism. an exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Matern Child Health J, 13(1), 29–39. 10.1007/s10995-008-0357-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General, Center for Mental Health Services, & National Institute of Mental Health. (2001). Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General. In Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Bates LM, & Acevedo-Garcia D (2010, Feb). Another Mexican birthweight paradox? The role of residential enclaves and neighborhood poverty in the birthweight of Mexican-origin infants. Soc Sci Med, 70(4), 550–560. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RL (2004, Nov-Dec). Positive pregnancy outcomes in Mexican immigrants: what can we learn? J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs, 33(6), 783–790. 10.1177/0884217504270595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IJK, Du H, Wang L, Williams DR, & Alegría M (2018, Apr). Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Mental Health in Mexican-Origin Youths and Their Parents: Testing the “Linked Lives” Hypothesis. J Adolesc Health, 62(4), 480–487. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegria M (2008, May 1). Prevalence and Correlates of Everyday Discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J Community Psychol, 36(4), 421–433. 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, & Pedroza JM (2019, Apr 1). Policies of Exclusion: Implications for the Health of Immigrants and Their Children. Annu Rev Public Health, 40, 147–166. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua DY, Chen H, Chong YS, Gluckman PD, Broekman BFP, & Meaney MJ (2020, 2020-August-06). Network Analyses of Maternal Pre- and Post-Partum Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(785). 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike IL, & Crocker RM (2020, Oct). “My own corner of loneliness:” Social isolation and place among Mexican immigrants in Arizona and Turkana pastoralists of Kenya. Transcult Psychiatry, 57(5), 661–672. 10.1177/1363461520938286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting C, Chavira DA, Ramos I, Christensen W, Guardino C, & Dunkel Schetter C (2020, Oct). Postpartum depressive symptoms in low-income Latinas: Cultural and contextual contributors. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol, 26(4), 544–556. 10.1037/cdp0000325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz RJ, Stowe RP, Brown A, & Wommack J (2012, Jul-Sep). Acculturation and biobehavioral profiles in pregnant women of Hispanic origin: generational differences. ANS Adv Nurs Sci, 35(3), E1–E10. 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182626199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz RJ, Stowe RP, Goluszko E, Clark MC, & Tan A (2007, Spring). The relationships among acculturation, body mass index, depression, and interleukin 1-receptor antagonist in Hispanic pregnant women. Ethn Dis, 17(2), 338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos H Jr., Fried EI, Asafu-Adjei J, & Ruiz RJ (2017, Jun). Network Structure of Perinatal Depressive Symptoms in Latinas: Relationship to Stress and Reproductive Biomarkers. Res Nurs Health, 40(3), 218–228. 10.1002/nur.21784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos HP Jr., Adynski H, Harris R, Bhattacharya A, Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Cali R, Yabar AT, Nephew BC, & Murgatroyd C (2020, Dec 31). Biopsychosocial correlates of psychological distress in Latina mothers. J Affect Disord, 282, 617–626. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos HP Jr., Nephew BC, Bhattacharya A, Tan X, Smith L, Alyamani RAS, Martin EM, Perreira K, Fry RC, & Murgatroyd C (2018, Dec). Discrimination exposure and DNA methylation of stress-related genes in Latina mothers. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 98, 131–138. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholaske L, Buss C, Wadhwa PD, & Entringer S (2018, Oct). Acculturation and interleukin (IL)-6 concentrations across pregnancy among Mexican-American women. Brain Behav Immun, 73, 731–735. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM (2020, May 7). Social Safety Theory: A Biologically Based Evolutionary Perspective on Life Stress, Health, and Behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 16, 265–295. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter F, Incollingo Rodriguez AC, Nephew BC, Cali R, Murgatroyd C, & Santos HP Jr. (2020, Nov). Pregnancy associated epigenetic markers of inflammation predict depression and anxiety symptoms in response to discrimination. Neurobiol Stress, 13, 100273. 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small R, Taft AJ, & Brown SJ (2011, Nov 25). The power of social connection and support in improving health: lessons from social support interventions with childbearing women. BMC Public Health, 11 Suppl 5(Suppl 5), S4. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-s5-s4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tome R, Rangel MA, Gibson-Davis CM, & Bellows L (2021). Heightened immigration enforcement impacts US citizens’ birth outcomes: Evidence from early ICE interventions in North Carolina. PLoS One, 16(2), e0245020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0245020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, & Updegraff KA (2014, Feb). Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 immigration law on utilization of health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Am J Public Health, 104 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S28–34. 10.2105/ajph.2013.301655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torche F, & Sirois C (2018). Restrictive Immigration Law and Birth Outcomes of Immigrant Women. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(1), 24–33. 10.1093/aje/kwy218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernice NA, Pereira NM, Wang A, Demetres M, & Adams LV (2020). The adverse health effects of punitive immigrant policies in the United States: A systematic review. PLoS One, 15(12), e0244054. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA (2007, Oct). Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med, 65(7), 1524–1535. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA (2011). “IT’S A LOT OF WORK”: Racialization Processes, Ethnic Identity Formations, and Their Health Implications. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 37–52. 10.1017/S1742058X11000117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, & Abdulrahim S (2012, Dec). More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med, 75(12), 2099–2106. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visionary Vanguard Group Inc. (2017). Community-Based Maternity Center, Final Evaluation Report. Retrieved June 30 2021, from http://www.commonsensechildbirth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/The-JJ-Way%C2%AE-Community-based-Maternity-Center-Evaluation-Report-2017-1.pd

- Walker JL, Ruiz RJ, Chinn JJ, Marti N, & Ricks TN (2012, Autumn). Discrimination, acculturation and other predictors of depression among pregnant Hispanic women. Ethn Dis, 22(4), 497–503. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3503150/pdf/nihms419442.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, & Vu C (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54(S2), 1374–1388. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1475-6773.13222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health:Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Ramin SM, Rush AJ, Navarrete CA, Carmody T, March D, Heartwell SF, & Leveno KJ (2001, Nov). Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. Am J Psychiatry, 158(11), 1856–1863. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilanawala A, & Pilkauskas NV (2012, Apr 1). Material Hardship and Child Socioemotional Behaviors: Differences by Types of Hardship, Timing, and Duration. Child Youth Serv Rev, 34(4), 814–825. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.