Abstract

Study Objective:

The purpose of this study was to examine feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a mindfulness-based healthy lifestyle self-management intervention with adolescents and young adults diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Design:

A pilot randomized controlled trial using a pre-post design was used.

Setting:

Central Texas. Participants: Individuals aged 14–23 with a diagnosis of PCOS.

Interventions:

The PCOS Kind Mind Program integrates a manualized mindfulness training program (Taming the Adolescent Mind) with health education in four key areas of self-management and health promotion; (1) medication adherence, (2) nutrition, (3) physical activity, and (4) sleep.

Main Outcome Measures:

Psychological distress, mindfulness, physical activity strategies, nutrition and exercise self-efficacy.

Results:

Linear regression models revealed that those in the PCOS Kind Mind condition reported significantly higher nutrition self-efficacy (β = 6.50, 95% CI = 1.71 – 11.28, p = 0.013, d = 0.48), physical activity strategies (β = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.04 – 0.79, p = 0.040, d = 0.67), and physical activity self-efficacy (β = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.07 – 0.88, p = 0.028, d = 0.46).

Conclusion:

The PCOS Kind Mind Program improved self-efficacy in the key areas of nutrition and physical activity and increased physical activity strategies in adolescents and young people with PCOS. These findings are encouraging and suggest the need for larger scale, randomized controlled trials with longer-term follow-up in order to more robustly evaluate the PCOS Kind Mind Program on the psychological and physiological health of adolescents and young people with PCOS.

Keywords: POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME, MINDFULNESS, SELF-MANAGEMENT, ADOLESCENTS, YOUNG ADULTS, HEALTHY LIFESTYLE

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common female endocrine disorder, affecting up to 6–26% of reproductive-aged women.1–3 Research has linked PCOS to a myriad of physical and mental health consequences across developmental stages, however, it has been suggested that the onset of PCOS may be earlier than previously thought.4–6 The emergence of PCOS during adolescence and young adulthood can be particularly distressing because the phenotype commonly associated with this condition (e.g., excessive, dark hair growth, acne, frequent/irregular menstruation) manifests during the critical period of identity formation and increased desire for significant peer relationships. These important milestones can be impacted by an individual’s feeling “different” from their peers. It follows that, in addition to increased risk for chronic medical conditions and cancer, PCOS is associated with elevated rates of psychological and psychosocial dysfunction.7

Medically, PCOS is often associated with overweight/obesity status, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, infertility, endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, and type 2 diabetes.4,8–12 Psychologically, PCOS has been empirically linked to poor self-esteem, bipolar disorders, social withdrawal, eating disorders, internalizing symptoms, negative body image, and psychosexual dysfunction.6,12–16 Indeed, a recent large-scale retrospective study found that individuals with PCOS reported higher levels of depressive, anxiety, and bipolar disorders than matched controls.7

Nevertheless, despite research linking comorbid mental health problems with worse physical outcomes for people with PCOS, clinical guidelines fail to incorporate mental health promotion or prevention efforts. Instead, they rely on secondary prevention recommendations (e.g., screening, referral) in the event that significant distress is identified.17 The failure to consider the intersection of mental and physical health in clinical guidelines is particularly detrimental for those with PCOS, given the hallmark of PCOS self-management includes engaging in lifestyle behaviors such as healthy nutrition, routine physical activity, and medication adherence.17 Self-management requires self-regulatory cognition (e.g., self-monitoring, emotional response management, reflective thinking) and self-efficacy.18–21 Mental health sequelae often comorbid with PCOS (e.g., depressogenic cognitions, poor self-esteem, anxiety) may undermine the self-regulatory processes and self-efficacy vital to self-management. Given that poor psychological health threatens the self-regulatory processes necessary to manage PCOS and that suboptimal management of PCOS is empirically linked to increased deterioration of physical health, there is a clear need for synergistic interventions to address both physical and mental health in this population.22–24

Research demonstrates that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) improve physical, emotional, and mental health symptoms among individuals with chronic conditions for which young people with PCOS are at particularly high risk (e.g., cardiovascular disease, T2D, obesity).25,26 Mindfulness comprises two primary components: (1) focused attention on one’s present experience, and (2) dispassionate, curious, and nonevaluative acceptance of mental states and processes involved in that experience.27,28 The mind–body model purports that the psychological (e.g., enhanced coping skills, stress acceptance) and psychosocial (e.g., improved self-regulation and self-efficacy) gains of MBIs may simultaneously promote positive health behaviors and improved physical health among chronically ill individuals.29–31 Meta-analytic findings show strong effect sizes for MBIs in reducing medical symptoms, depression and anxiety symptoms, stress, and disordered eating, and in improving coping, well-being, and quality of life among patients with cardiovascular disease, chronic pain, obesity, and eating disorders.30, 32–34

Particularly relevant to individuals with PCOS, a recent systematic review found that MBIs promoted lifestyle modifications and self-management of diabetes (e.g., physical activity, medication adherence, weight maintenance) among adults by reducing stress, anxiety, and depression and improving well-being, health status, and quality of life.35 To our knowledge, only one randomized controlled trial has reported the efficacy of an MBI with PCOS patients.36,37 Pilot work is promising; reproductive-aged females with PCOS randomized to an 8-week MBI (vs. control group) reported lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression and higher quality of life.37

Comparatively, far less work has examined the efficacy of MBIs for self-management among adolescents and young adults diagnosed with chronic physical conditions.38,39 However, research suggests that MBIs used with adults may have similar relevance for self-management among chronically ill adolescents and young adults. Pilot work indicates the feasibility and acceptability of MBIs for adolescent women with chronic pain.40 Similarly, pilot work links MBIs with reduced depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up among adolescent women with overweight status, depression, and a family history of T2DM.41 As an emerging area of research, there is a clear need for intervention studies examining the efficacy of MBIs for use with adolescents suffering from chronic physical conditions, particularly those exacerbated by stress (i.e., PCOS, diabetes).38,40,42

To date, no known work has examined MBIs as a self-management strategy specifically for adolescents and young adults diagnosed with PCOS. This is a significant limitation in that although PCOS may not be formally diagnosed until later in life, the onset of PCOS can often be traced back to the events of puberty.43Likewise, there are no known integrated interventions for PCOS that concurrently address and prevent physical and mental health complications.15,22 Therefore, the present study seeks to examine the acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy of a holistic intervention integrating a mindfulness-based intervention with healthy lifestyle activities and education as an approach to encourage effective self-management among adolescents and young adults with PCOS.

Methods

Design

This was a pilot randomized controlled trial using a pre/post design, comparing a 5-week mindfulness-based healthy lifestyle self-management intervention (the PCOS Kind Mind Program) with a wait-list-control condition.

Procedures

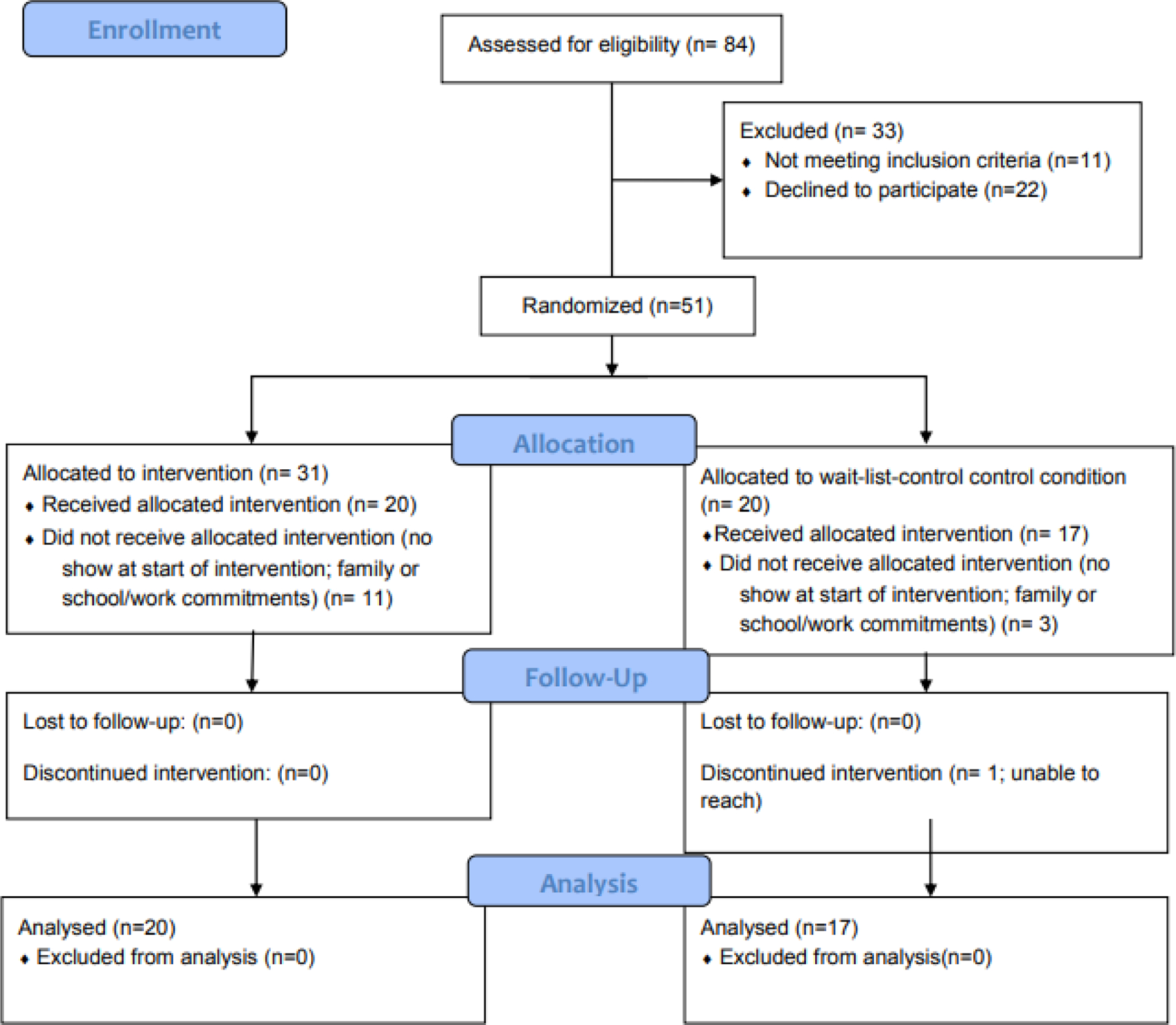

After obtaining university institutional review board approval, potential participants were screened for eligibility. Participants were aged 14–23 years, with a diagnosis of PCOS located in central Texas. Participants were ineligible if they (1) were unable to commit to attending all intervention sessions, (2) had lost a loved one within the last year, or (3) had a history of post-traumatic stress disorder. Recruitment was (1) clinic-based (i.e., an adolescent medicine and pediatric endocrinology practice), (2) via a large university email list-serve, and (3) via Facebook. After potential participants were screened and basic eligibility was determined, parental permission and adolescent assent were obtained for participants who were <18 years, informed consent was obtained from those who were ≥18 years, and participants were assigned to condition via block randomization. See CONSORT Diagram (Figure 1) for flow of participants through the study. Intervention sessions were initiated in a rolling fashion after 4 participants were assigned to each condition. Difficulties with recruitment and timing of group initiation prompted a major protocol modification during the conduct of this pilot RCT. Initially, clinic-based recruitment at an adolescent medicine clinic (with a pediatric PCOS specialist physician) began in summer of 2018 and six groups were conducted (n=3 intervention & n=3 wait-list control) by April 2019. The age range of participants in these groups was 14–17 with one 18-year-old. With this population, a diagnosis of PCOS was confirmed via medical record. After clinic-based recruitment failed to yield a sufficient number of participants, the protocol was modified to (1) increase the age range to 24, (2) include those with a self-reported diagnosis of PCOS, (3) offer intervention sessions online, and (4) expand recruitment methods to social media and listserves. The subsequent six groups were completed in the fall of 2019 and early spring of 2020 and consisted of participants ranging in age from 18–24 years. Time between recruitment and group initiation varied as a function of group assignment (i.e., intervention vs. wait-list control), however, for those in the intervention group, they began within an average of two weeks. All participants completed a battery of standardized measures at baseline and again immediately following the intervention.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Initially, group intervention sessions were held in person on Saturday mornings, at an adolescent medicine practice that served as a primary recruitment site. After difficulties were encountered with travel and competing demands for participants’ time, the study protocol was modified to utilize online delivery of intervention sessions via Zoom on a weekday evening. All participants received the following intervention materials: (1) the Taming the Adolescent Mind (TAM) manual,44 (2) the PCOS Kind Mind manual, (3) a Fitbit tracker, and (4) various arts and crafts supplies. Participants who missed an intervention session were invited to attend a make-up session before the start of the next week’s session while the intervention was in person, or, subsequently, online via Zoom at a time/day mutually agreed upon by the interventionist and participant. A very few number of make-up sessions were conducted (i.e., <5). One of these sessions had two participants as both had missed the weekly session and the others were conducted one-on-one. Upon completion of the intervention, participants were given the option to complete an exit interview to discuss their experiences of the intervention.

Intervention

This 5-week, mindfulness-based healthy lifestyle intervention was developed through holding a series of focus group meetings24,45 and in collaboration with Dr. Lucy Tan, the developer of TAM, a mindfulness intervention for adolescents with mental health difficulties. See Table 1 for overview of intervention components. The original TAM protocol was piloted and further tested in a randomized controlled trial for its efficacy and effectiveness.46,47 The key components in the TAM program are for participants to master ROAM (R: regulate attention; O: observe inside [i.e., body, sensations, etc.] and outside [i.e., environment]; A: acceptance without judgments; M: be mindful). The format for each weekly session is set out in the manual, characterized by two formal mindfulness exercises (at the start and at the end of each session) and a review of homework practice followed by group discussions of session themes. Mindfulness skills training activities are experientially designed to enhance awareness of one’s body and mind to teach participants to notice automatic reactions with consciously chosen responses, and to bring greater awareness and skill to interpersonal communications. Experiential exercises allow participants to experience mindfulness practices with the use of various materials and activities (e.g., food, plasticine, movement, drawing)

Table 1.

PCOS Kind Mind Intervention Outline

| Weeks/Topic | Intervention Domains and Associated Activities* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness | Nutrition Content | Physical Activity (PA) | Sleep | |

| 1. Introduction to ROAM & Learning to regulate attention |

|

|

|

|

| 2. Observer of the present moment |

|

|

|

|

| 3. Acceptance |

|

|

|

|

| 4. Being mindful |

|

|

|

|

| 5. Mindfulness & beyond |

|

|

|

|

Medication adherence was tracked via a free app and discussed at each session.

TAM provided the structure and informed the development of the intervention, the PCOS Kind Mind Program (i.e., five 60- to 75-minute consecutive weekly sessions), within which the TAM mindfulness activities/exercises were tailored to meet the needs of the PCOS population (e.g., awareness of and reflection on condition-specific symptoms and broader health concerns). In PCOS Kind Mind, the healthy lifestyle content covered (1) medication adherence, (2) physical activity, (3) sleep, and (4) nutrition (see Table 1 for program components). A mindfulness approach was taken in discussing each of these components to bring non-judgmental attention to, and promote awareness of, participants’ behaviors within each area of health promotion. Participants were encouraged to use their smartphones to record the guided mindfulness exercises that were provided during the session and then use the recordings for daily practice. Intervention sessions were led by an interventionist trained in psychology, nursing, and/or social work. All interventionists received training on the delivery of TAM by Dr. Tan and on the healthy lifestyle components by the principal investigator A total of three interventionists were involved in intervention delivery. Two were psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners enrolled in a nursing PhD program and one was a master’s student in social work.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic variables included age, family history of PCOS, parental marital status, race/ethnic background of self and family members, and number of people living in the home. Socioeconomic status was determined using a combined approach based on Hollingshead’s Two Factor Index of Social Position48 and Barratt’s Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS),49 which was developed based on Hollingshead’s measure. The BSMSS provides an updated list of occupations to maintain present-day relevance. Ultimately, 5 classifications are produced using level of educational attainment and current employment of participants’ parents, with Class I the highest class (i.e., major business professionals) and Class V the lowest (i.e., unskilled laborers).

Self-Esteem

The 10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale50 was used to assess participants’ self-esteem. Participants rate their level of agreement with each statement on a scale ranging from 0 = “strongly disagree” to 3 = “strongly agree.” Sample items include “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself,” and “I feel that I have a number of good qualities.” Five items are reverse scored, with the total score summed from all items; higher scores indicate greater self-esteem (range: 0–30). Cronbach’s α for the present study was 0.88.

Psychological Distress

The 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale51 (DASS-21) was used to assess level of psychological distress within three domains: (1) depression, (2) anxiety, and (3) stress. Ratings for each item range from 0 = “Did not apply to me at all” to 3 = “Applied to me very much or most of the time.” Scores are summed and then doubled to achieve equivalence to the longer 42-item DASS. Possible scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more distress within a given domain. The scale has been tested in older adults, adults, and children in clinical and nonclinical settings, and it has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity.51,52 Cronbach’s α for the present study was 0.87.

Mindfulness

The 10-item Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure53 was used to assess dispositional mindfulness. On a 5-point scale from 0 = “never” to 4 = “always true,” participants rate how often each item is true for them. Scores on the 10 items are summed, with a possible range from 0 to 40; lower scores indicate more mindfulness behaviors. Cronbach’s α of 0.81 has been reported.53 For the present study, internal consistency reliability was 0.87.

Nutrition Self-Efficacy

The 11-item Diet Self-Efficacy Scale (DIET-SE)54 is a scenario-based measure of dieting self-efficacy in which participants are asked to imagine themselves in a certain situation and indicate their level of confidence in their ability to overcome that situation. Each scenario is rated on a scale from 0 = “not at all confident” to 4 = “very confident.” Scores are summed, with a possible range of 0–44; higher scores indicate higher levels of self-efficacy. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability have been reported as adequate.55 Cronbach’s α for the present study was 0.88.

Physical Activity Self-Efficacy and Strategies

Two subscales of the PACE Adolescent Physical Activity Survey56 were used to assess physical activity within the domains of self-efficacy for overcoming barriers to physical activity (6 items) and strategies for physical activity (15 items), respectively. On the self-efficacy subscale, items are rated on a scale from 1 = “I’m sure I can’t” to 5 = “I’m sure I can.” The total score is calculated by computing the mean of all six items, with high scores reflecting higher physical activity self-efficacy. The items for physical activity strategies are rated from 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Many times,” to show how often an individual uses that strategy. The mean of the items is calculated, with higher scores indicating use of more physical activity strategies. Cronbach’s α for the present study was 0.85 for self-efficacy and 0.87 for strategies.

Data Analysis

The target sample size for this study (N = 40) was selected to make estimates of effect size upper limits57 rather than to power statistical tests for certain effect sizes. A total of 37 participants (92.5% of target N) completed the study. Power analyses showed that the sample size of 37 can detect medium-large effect sizes (f2 ≥ 0.23), with 80% power and a significance level of alpha of 0.05. Group differences in self-esteem, psychological distress (i.e., symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety, perceived stress), mindfulness, nutrition self-efficacy, and physical activity self-efficacy at the end of the intervention were evaluated with linear regression models, controlling for baseline scores; age, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. others) were control variables. Unadjusted effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were estimated at the end of the intervention.

Results

Sample/Baseline Characteristics

A total of 37 participants (71.2% of those who enrolled) completed at least some of the assessments at the end of the intervention and were included in our analyses. Demographic and baseline variables across conditions are presented in Table 2. Compared with the 37 who completed the follow-up assessment, those who dropped out (n = 15) had marginally lower depressive symptoms at baseline (M = 8.8, SD = 7.6, vs. M =14.4, SD = 10.5, for completers, p = 0.084). Only 1 participant who started the intervention (i.e., attended at least 1 session) did not complete all 5 sessions, yielding a completion rate of over 97% (see Figure 1). All other participants who were randomized but did not receive the allocated intervention were either no shows on the intervention’s first day or those who notified study personnel that competing demands precluded their participation after enrollment but prior to initiation of intervention.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics (N = 37)

| Intervention (n = 20) | Control (n = 17) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years [Mean (SD)] | 18.5 (2.5) | 17.4 (2.3) | 0.18 |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Latinx | 8 (40.0) | 8 (47.1%) | 0.75 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 7 (35.0) | 6 (35.3) | 1.00 |

| Black or African American | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.8) | 0.46 |

| Asian | 3 (15.0) | 3 (17.6) | 1.00 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1.00 |

| Family member(s) with PCOS (Yes/No) | 9 (45) | 4 (23.5) | 0.31 |

| SES | 0.03 | ||

| II | 1 (5.0) | 4 (23.5) | |

| III | 2 (10.0) | 3 (17.6) | |

| IV | 12 (60.0) | 2 (11.8) | |

| V | 4 (20.0) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (5.0) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Parents’ marital status | 0.26 | ||

| Single | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.8) | |

| Married | 16 (80.0) | 12 (70.6) | |

| Divorced | 3 (15.0) | 1 (5.8) | |

| Living with a partner | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Other | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Feasibility and Acceptability

Exit interview data obtained from 14 participants indicated acceptability of the intervention. Participants reported using mindfulness techniques to examine more than just their health behaviors. For example, 1 participant stated that during one intervention session, she was able to identify a significant source of stress (i.e., working too many hours as a high school senior) and realized that although she enjoyed making money, her long hours were contributing to lack of sleep and exhaustion. She cut back on her work hours, and in her interview 1-month post-intervention, she reported that she had sustained better sleep and less psychological stress. Feasibility and acceptability were further demonstrated by participants’ high attendance and completion rates.

Intervention Effects

Linear regression models revealed that those in PCOS Kind Mind reported significantly higher nutrition self-efficacy (β = 6.50, 95% CI = 1.71–11.28, P = 0.013, d = 0.48), increased physical activity strategies (β = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.04–0.79, P = 0.040, d = 0.67), and higher physical activity self-efficacy (β = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.07 – 0.88, P = 0.028, d = 0.46) at the end of the intervention, in comparison with those in the control condition and controlling for corresponding baseline values, age, and racial minority status. No significant group differences were found for depression (n = 33, P = 0.48), anxiety (n = 33; P = 0.85), perceived stress (n = 34; P = 0.72), mindfulness (n = 36, P = 0.27), or self-esteem (n = 35; P = 0.15), controlling for the same covariates.

Discussion

The PCOS Kind Mind Program demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and improved nutrition self-efficacy, physical activity self-efficacy, and confidence in physical activity strategies among adolescents and young adults with PCOS. Given that a hallmark of PCOS self-management consists of engagement in healthy lifestyle behaviors, the finding that self-efficacy improved in these key areas is highly encouraging. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate a mindfulness-based healthy lifestyle intervention with a developmental lens for adolescent and transition-aged individuals with PCOS. These findings, considered within the broader literature on MBIs for improving chronic health conditions, point to the potential effectiveness of the PCOS Kind Mind intervention for improving self-management in this population.

This study’s findings contribute to the literature on the role of mindfulness in relation to health behaviors (i.e., nutrition and physical activity) by extending its positive benefits to adolescents and young adults. Among adults, MBIs targeting eating behaviors and physical activity have received increasing attention. A literature review of MBIs for obesity-related eating behaviors identified 21 papers, 18 of which (86%) reported improvements in eating behaviors (binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating).26 Similarly, a systematic review of MBIs in relation to physical activity identified 20 MBIs that identified positive between-subjects effects on physical activity.58

The lack of group differences on the psychological variables of interest (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety, perceived stress, and self-esteem) was surprising, and it warrants further evaluation. A randomized controlled trial testing the TAM treatment protocol with adolescents aged 13–18 years (N = 108) found significant decreases in psychological distress immediately post-intervention and sustained effects at 3-month follow-up.47 Additionally, at 3-month follow-up, there were significant improvements in self-esteem and mindfulness. Similarly, Shomaker and colleagues41,59 tested an MBI with adolescent females with overweight/obesity status and found that for symptoms of depression, improvements were sustained over one year. It may be that with additional longitudinal assessments, significant group differences would have emerged as the participants continued to engage in mindfulness and healthy lifestyle practices. Clearly, more evaluation with longer follow-up assessments is warranted.

Limitations

Although efforts were made to ensure the rigor of this study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, a major protocol modification was undertaken in response to difficulties with clinic-based recruitment and delivery of the intervention that impacted our ability to obtain biometric data, required a self-reported diagnosis of PCOS, and may have resulted in selection bias. Additionally, it is unknown whether the differences in intervention delivery methods (i.e., in-person vs. online) or the differences between the interventionists influenced study outcomes. Online delivery improved convenience, but certain aspects of a face-to-face therapeutic milieu may have been lacking. However, the forced acceptance and increased utilization of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that the online delivery of therapeutic interventions is feasible and, for many, preferable. In addition, all participants were recruited from a single geographic area, with a relatively small sample size that did not quite meet the intended number of participants. We did not obtain physiological data from the participants’ Fitbits to evaluate the impact of the intervention on physical health outcomes. Additional objective data (e.g., step count, sleep quality/hours of sleep) will be important to obtain as the effectiveness of MBIs for the health and well-being of adolescents and young women continues to be investigated.

Recommendations for future research

As a pilot study, much was learned regarding delivering a mindfulness-based healthy lifestyle intervention for adolescents and young adults with PCOS. In order to advance the science in this area, several key components should be addressed. In alignment with the limitations noted above, participants’ physiologic data must be collected to assess the impact of the intervention on aspects of physical health. Which types of data and the timing of these collections needs significant consideration due to the developmental stage at which these individuals find themselves. It may be that, for example, maintaining a BMI or HbgA1c level vs. gaining weight or HbgA1c increase across the study period is indeed a significant finding because weight gain and increase in HbgA1c over time is the expected trajectory. To this end, cohort-level research examining the trajectories of health parameters over time would provide a foundation for answering these important questions related to evaluating health promotion interventions among individuals with PCOS. Future research should include (1) objective measures (e.g., step count, hours of sleep) as a part of study outcomes, (2) study designs, sampling plans, and data analytic strategies that allow for comparisons between obese and non-obese participants, and (3) further piloting of the intervention with additional tailoring of length, content, and delivery in order to most meet the needs of this vulnerable population.

Conclusions

The PCOS Kind Mind Program was feasible and acceptable; it improved self-efficacy in nutrition and physical activity and increased physical activity strategies in adolescents and young women with PCOS. These encouraging findings suggest the need for larger scale, randomized controlled trials with longer term follow-up in order to evaluate the effect of the PCOS Kind Mind Program on the psychological and physiological health of adolescents and young women with PCOS more robustly.

Table 3.

Baseline and Post-Intervention Scores

| Intervention (n = 20) | Control (n = 17) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Measure (Possible Range) | T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 |

| Self-Esteem (0–30) | 13.9 (4.0) | 17.8 (3.9) | 18.8 (5.0) | 19.4 (6.0) |

| Depression Score (0–21) | 16.5 (11.1) | 15.0 (8.2) | 11.8 (9.4) | 9.7 (9.1) |

| Stress Score (0–21) | 16.2 (9.0) | 16.9 (9.7) | 17.5 (8.2) | 15.9 (9.5) |

| Anxiety Score (0–21) | 12.8 (8.9) | 13.7 (10.0) | 12.3 (8.5) | 13.3 (11.8) |

| Mindfulness (0–40) | 20.3 (6.4) | 18.6 (6.6) | 17.2 (5.3) | 14.5 (6.7) |

| Nutrition Self-efficacy (0–44) | 20.0 (9.3) | 25.7 (10.0) | 20.1 (8.7) | 21.1 (9.0) |

| Physical Activity Self-efficacy (1–6) | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.2 (0.7) |

| Physical Activity Strategies (1–15) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.1 (0.5) |

Note. SD = Standard deviation; T1 = Baseline; T2 = Post-Intervention

Table 4.

Intervention effects on Outcome Variables

| Outcome Measures | Estimates (β) | 95%CI | p value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Esteem (RSE) | 2.10 | −0.67 – 4.88 | 0.15 | (0.31) |

| Depression Score (DASS) | 2.19 | −3.86 – 8.25 | 0.48 | (0.61) |

| Stress Score (DASS) | 1.19 | −5.32 – 7.71 | 0.72 | (0.11) |

| Anxiety Score (DASS) | 0.65 | −6.20 – 7.50 | 0.85 | (0.04) |

| Mindfulness (CAMM) | 2.30 | −1.73 – 6.43 | 0.27 | 0.61 |

| Nutrition Self-efficacy (DIET) | 6.50 | 1.71 – 11.28 | 0.01* | 0.48 |

| Physical Activity Self-efficacy (PACE Confidence) | 0.48 | 0.07 – 0.88 | 0.03* | 0.46 |

| Physical Activity Strategies (PACE Strategies) | 0.41 | 0.04 – 0.79 | 0.04* | 0.67 |

Note: d = Unadjusted Cohen’s d at post-intervention.

indicates a statistically significant p value. All analyses included corresponding baseline score, age, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white vs. others) as covariates. ds in parentheses are the opposite effect from the predicted direction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from NINR through the (Center for Transdisciplinary Collaborative Research in Self-Management Science (P30NR015335-01; Kim, PI.). We would also like to thank the graduate research assistants, interventionists, and clinical staff that contributed to the successful completion of this study.

Funding for this project was awarded to Dr. Young by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research, P30NR015335-01 (Center for Transdisciplinary Collaborative Research in Self-Management Science, Kim PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Location of study

Austin, Texas

Previous presentation of findings

A portion of these findings were presented at the 42nd Annual Meeting & Scientific Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Virtual, April 12–16, 2021

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest Statement

No authors report any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Skiba MA, Islam RM, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Understanding variation in prevalence estimates of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2018; 24(6):694–709. 10.1093/humupd/dmy022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.March WA, Moore VM, Wilson KJ, Phillips DIW, Norman RJ, Davies MJ. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 2010; 25(2):544–51. 10.1093/humrep/dep399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tehrani FR, Simbar M, Tohid M, Hosseinpanah F, Azizi F. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample of Iranian population: Iranian PCOS prevalence study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2011; 9:39. 10.1186/1477-7827-9-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates GW, Legro RS. Longterm management of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013; 373(1–2):91–7. 10.1016/j.mce.2012.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bronstein J, Tawdekar S, Liu Y, Pawelczak M, David R, Shah B. Age of onset of polycystic ovarian syndrome in girls may be earlier than previously thought. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2011; 24(1):15–20. 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trent ME, Rich M, Austin SB, Gordon CM. Quality of life in adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002; 156(6):556–60. 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berni TR, Morgan CL, Berni ER, Rees DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome is associated with adverse mental health and neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2018; 103(6):2116–25. 10.1210/jc.2017-02667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chittenden BG, Fullerton G, Maheshwari A, Bhattacharya S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of gynaecological cancer: a systematic review. Reprod Biomed Onine 2009; 19(3):398–405. 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60175-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrmann DA, Barnes RB, Rosenfield RL, Cavaghan MK, Imperial J. Prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance with diabetes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes Care 1999; 22(1):141–6. 10.2337/diacare.22.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrell K, Antoni MH. Insulin resistance, obesity, inflammation, and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: biobehavioral mechanisms and interventions. Fertil Steril 2010; 94(5):1565–74. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 201(6):1–13. 10.2147/CLEP.S37559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med 2010; 8:41. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Açmaz G, Albayrak E, Acmaz B, Başer M, Soyak M, Zararsiz G, İpekMüderris İ. Level of anxiety, depression, self-esteem, social anxiety, and quality of life among the women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Scientific World J 2013; 851815. 10.1155/2013/851815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dokras A, Clifton S, Futterweit W, Wild R. Increased prevalence of anxiety symptoms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2012; 97(1):225–30.E2. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollinrake E, Abreu A, Maifeld M, Van Voorhis BJ, Dokras A. Increased risk of depressive disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2007; 87(6):1369–76. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trent M, Austin SB, Rich M, Gordon CM. Overweight status of adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome: body mass index as mediator of quality of life. Ambul Pediatr 2005; 5(2):107–11. 10.1367/A04-130R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deeks AA, Gibson-Helm ME, Teed HJ. Anxiety and depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive investigation. Fertil Steril 2010; 93(7):2421–3. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandura A Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vohs KD, Baumeister RF. Undertanding self-regulation: an introduction. In Baumestier RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: research, theory, and applications. New York: The Guilford Press Press; 2004. pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the structure of behavioral self-regulation. In: Bookaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 41–84. 10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50032-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Coping processes and adjustment to chronic illness. In: Christensen AJ Antoni MH, editors. Chronic physical disorders: behavioral medicine’s perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2002. pp. 47–68. 10.1002/9780470693513.ch3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Himelien MJ, Thatcher SS. Polycystic ovary syndrome and mental health: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006; 61(11):723–32. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000243772.33357.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolf WM, Wattick RA, Kinkade ON, Olfert MD. The current description and future need for multidisciplinary PCOS clinics. J Clin Med 2018; 7(11):395. 10.3390/jcm7110395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young CC, Sagna AO, Monge M, Rew L. (2020). A theoretically grounded exploration of individual and family self-management of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Compr Child Adolesc Nurs 2020; 43(4):348–62. 10.1080/24694193.2019.1679278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007; 75(2):336–43. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Reilly GA, Cook L, Spruijt-Metz D, Black DS. Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obes Rev 2014; 15(6):453–61. 10.1111/obr.12156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2004; 11(3):230–41. 10.1093/clipsy.bph077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabat-Zinn J Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Dell Publishing, Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dreger LC, Mackenzie C, McLeod B. Feasibility of a mindfulness-based intervention for aboriginal adults with type 2 diabetes. Mindfulness 2015; 6(2):264–80. 10.1007/s12671-013-0257-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2004; 57(1):35–43. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitebird RR, Kreitzer MJ, O’Connor PJ. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and diabetes. Diabetes Spectr 2009; 22(4):226–30. 10.2337/diaspect.22.4.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abbott RA, Whear R, Rodgers LR, Bethel A, Coon JT, Kuyken W, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychosom Res 2014; 76(5):341–51. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 2003; 10(2):125–43. 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katterman SN, Kleinman BM, Hood MM, Nackers LM, Corsica JA. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: a systematic review. Eat Behav 2014; 15(2):197–204. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noordali F, Cumming J, Thompson JL. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on physiological and psychological complications in adults with diabetes: a systematic review. J Health Psychol 2017; 22(8):965–83. 10.1177/1359105315620293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooney LG, Dokras A. Depression and anxiety in polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017; 19(11):83. 10.1007/s11920-017-0834-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefanaki C, Bacopoulou F, Livadas S, Kandaraki A, Karachalios A, Chrousos GP, Diamanti-Kandarakis E. Impact of a mindfulness stress management program on stress, anxiety, depression and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Stress 2015; 18(1):57–66. 10.3109/10253890.2014.974030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abujaradeh H, Safadi R, Sereika SM, Kahle CT, Cohen SM. Mindfulness-based interventions among adolescents with chronic diseases in clinical settings: a systematic review. J Pediatr Health Care 2018; 32(5):455–72. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wild RA, Carmina E, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Dokras A, Escobar-Morreale F, Futterweit W, et al. Assessment of cardiovascular risk and prevention of cardiovascular disease in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome: a consensus statement by the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (AE-PCOS) Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95(5):2038–49. 10.1210/jc.2009-2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chadi N, McMahon A, Vadnais M, Malboeuf-Hurtubise C, Djemli A, Dobkin PL, et al. (2016). Mindfulness-based intervention for female adolescents with chronic pain: a pilot randomized trial. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016; 25(3):159–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shomaker LB, Pivarunas B, Annameler SK, Gulley L, Quaglia J, Brown KW, et al. One-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial piloting a mindfulness-based group intervention for adolescent insulin resistance. Front Psychol 2019; 10:1040. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahola Kohut S, Stinson J, Davies-Chalmers C, Ruskin D, van Wyk M. Mindfulness-based interventions in clinical samples of adolescents with chronic illness: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med 2017; 23(8):581–9. 10.1089/acm.2016.0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang RJ, Coffler MS. Polycystic ovary syndrome: Early detection in the adolescent. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 50(1):178–87. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31802f50fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan LBG. Taming the adolescent mind: a mindfulness-based training program for adolescents: workbook for adolescents; 2014.

- 45.Young CC, Rew L, Monge M. (2019). Transition to self-management among adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome: parent and adolescent perspectives. J Pediatr Nurs 2019; 47:85–91. 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan L, Martin G. Taming the adolescent mind: preliminary report of a mindfulness-based psychological intervention for adolescents with clinical heterogeneous mental health diagnoses. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013; 18(2):300–12. 10.1177/1359104512455182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan L, Martin G. Taming the adolescent mind: a randomised controlled trial examining clinical efficacy of an adolescent mindfulness-based group programme. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2015; 20(1):49–55. 10.1111/camh.12057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of social position. Privately printed manuscript. New Haven, CT; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barratt W About the Barrat Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS). Indiana State University; 2006. http://socialclassoncampus.blogspot.com/2012/06/barratt-simplified-measure-of-social.html [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenberg M Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005; 44(2):227–39. 10.1348/014466505X29657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of he 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in cinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess 1998; 10(2):176–181. 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greco LA, Baer RA, Smith GT. Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychol Assess 2011; 23(3):606–14. 10.1037/a0022819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knäuper B The diet self efficacy scale (DIET-SE). Measurement Instrument Database for the Social Sciences; 2013. https://www.midss.org/content/diet-self-efficacy-scale-diet-se [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stitch C, Knäuper B, Tint A. A scenario-based measure of dieting self-efficacy scale: the DIET-SE. Assessment 2009; 16(1):16–30. 10.1177/1073191108322000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prochaska JJ, Sallis JF, Long B. A physical activity screening measure for use with adolescents in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001; 155(5):554–9. 10.1001/archpedi.155.5.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, Tinklenberg J, Yesavage JA. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63(5):484–9. 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider J, Malinowski P, Watson PM, Lattimore P. The role of mindfulness in physical activity: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2019; 20(3):448–63. 10.1111/obr.12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shomaker LB, Bruggink S, Pivarunas B, Skoranski A, Foss J, Chaffin E, et al. (2017). Pilot randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness-based group intervention in adolescent girls at risk for type 2 diabetes with depressive symptoms. Complement Ther Med 2017; 32:66–74. 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]