Abstract

Background

Children with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and their families deal with challenging circumstances. While numerous studies have shown that both patients and parents in these families can experience a variety of challenges and concerns, the experience of siblings is less well understood. The focus of this scoping review was on research addressing the experiences and well-being of siblings of children with CKD.

Methods

Following scoping review methodology, five databases were searched for peer-reviewed research or graduate theses published in English that addressed the experience or well-being of siblings aged 25 years or younger (biological, step or foster) of children with CKD; studies from any year or location were included. Two independent coders identified relevant studies. Findings were summarized and synthesized.

Results

Of the 2990 studies identified, 19 were chosen for full text review and eight fit the inclusion criteria. Five of the selected studies were qualitative, two were quantitative and one used mixed-methods. Four broad themes across studies were identified including family functioning, significant relationships, psychological well-being, and coping strategies. While there was some convergence between qualitative and quantitative findings, these linkages were weak.

Conclusions

Several unmet needs of siblings were uncovered by this review. Sibling perceptions of differential parental treatment and desire for information about CKD emerged as priorities for practice. Using a strength-based approach in order to better understand sibling experiences and well-being was also recommended for future research.

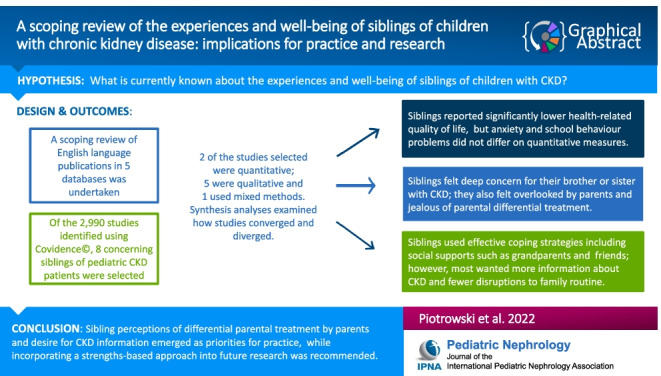

Graphical abstract

A higher resolution version of the Graphical abstract is available as Supplementary information.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00467-022-05559-5.

Keywords: Children, Chronic kidney disease, Siblings, Well-being

Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in children is estimated at 15 to 75 cases per million children [1]. Children living with CKD and their families deal with very challenging circumstances on a daily basis [2]. Past research has shown that these children are at risk for a wide variety of difficulties in emotional and behavioral functioning, (e.g., depression), educational and occupational functioning (e.g., learning disabilities), and physical and social functioning (e.g., social activities) [2]. The well-being of their parents and other caregivers has also garnered research attention [3]; however, to date the experiences and well-being of siblings in these families have been understudied [4].

Although there is a rigorous body of work concerning sibling experiences across diverse family illness contexts (e.g., complex care needs, chronic conditions, life-limiting and life-threatening conditions) [5, 6], siblings of children with CKD are rarely focused upon specifically. This is surprising as the course and scope of CKD can differ markedly from other pediatric illnesses. For example, peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis can demand daily treatment lasting several hours or overnight therapy [7]. While diverse pediatric chronic illnesses share some characteristics [8, 9], it is important to understand the specific contexts that families experience in order to design effective support programs. Therefore, we undertook a scoping review of studies focused on sibling experiences and well-being in families affected by CKD in order to: (1) summarize and synthesize current findings with a view to identifying potential avenues for support programs, and (2) to identify current gaps in order to provide directions for future research. Our review was broadly defined; it included all aspects of sibling experience as reported by siblings themselves, or by their parents. Our approach to well-being included adjustment difficulties and mental health issues, as well as positive aspects such as resilient characteristics, processes and outcomes [10], and posttraumatic growth.

Methods

Search strategy

We followed the five steps of conducting a scoping review, including: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results [11, 12]. Our research question was: “What is known from the existing literature about the experiences and well-being of siblings of children with chronic kidney disease?”.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria included any graduate thesis or published peer-reviewed study written in English and published in any year or location within five databases (Medline, Scopus, PsychInfo, CINAHL and Embase). Any type of sibling relationship (biological, step or foster) in young people aged 25 years or younger was included. Search concepts included: (1) age range (i.e. pediatrics through young adulthood), (2) siblings, (3) chronic kidney disease (i.e. “renal insufficiency, chronic,””kidney failure, chronic”), (4) kidney transplant (i.e. “renal replacement therapy,””renal dialysis,” “kidney transplant”) and (5) experience (i.e. “quality of life,” “mental health,” “resilience,” “posttraumatic growth, psychological,””social support”). Please see Appendix 1 for an example of the search terms used for one database.

Study selection

All identified articles were screened using Covidence© which is an online data extraction and screening tool designed to facilitate the review process by supporting the import of citations, removal of duplication, as well as title, abstract and full-text screening. Two reviewers (DJ and MW) independently screened titles and abstracts of all identified articles. Any selection differences were resolved through discussion (DJ, MW and CP) following full-text review. Eight studies were selected, including two quantitative studies, five qualitative studies, and one mixed-methods study. The ages of siblings in these studies ranged from six to 18 years. No research on young adults was identified.

Data charting

Data were initially extracted from each article by one reviewer (DJ); details were checked for accuracy by a second reviewer (CP). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Extracted data included country of study, study approach (qualitative, quantitative or mixed), study design, number and age of sibling participants, method of data collection, and findings related to sibling experiences living with a child with CKD.

Data synthesis

Study characteristics (e.g. approach, design, country and main findings) were descriptively summarized to create a high-level overview of research conducted to date on siblings’ experiences and well-being. Key findings from each study were iteratively reviewed to identify themes across qualitative studies. Lastly, we conducted a synthesis in which we analyzed the manner and extent to which the quantitative and qualitative findings converged, diverged or complemented one another in order to create a more complete understanding of the well-being and experiences of siblings of children with CKD.

Results

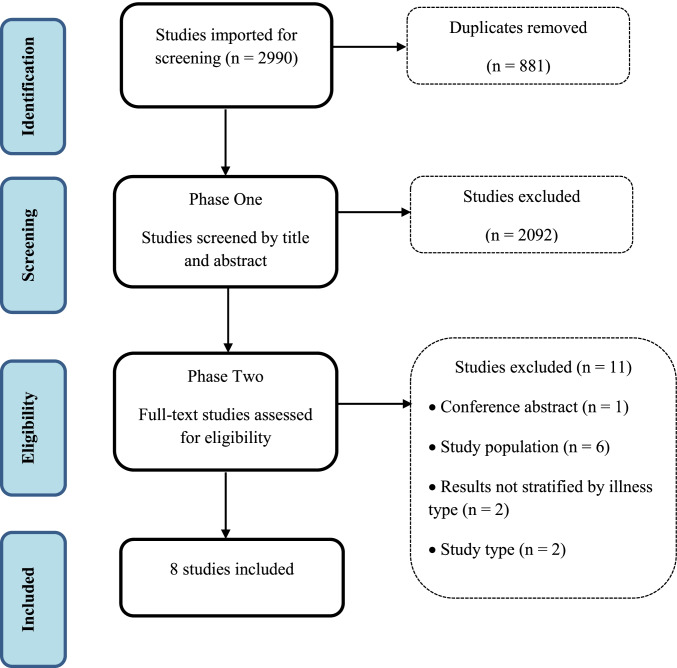

From our initial and updated searches, we identified a total of 2990 potentially relevant articles. After 881 duplicates were removed, 2109 titles were screened and 19 full-text studies were chosen for a more detailed review. Eight studies were identified as meeting our criteria and relevant to our review question. An overview of the study selection process and reasons for exclusion are provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart outlining the study selection process

Characteristics of studies

The eight selected studies included two quantitative studies [13, 14], five qualitative studies [15–19] and one mixed-methods study [4] that were published in four countries. Most (75%) but not all studies included information obtained directly from siblings; three were published by the same research team with overlap in participants. All studies included siblings of children with CKD, with two studies including post-transplant families. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Summary of publications selected for review

| Authors/Year | Country | Design/measures | Participants | Health status | Sibling ages | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agerskov et al. 2019 [17] | Denmark | Qualitative: semi-structured individual interviews | 7 mothers and fathers, 5 siblings and 5 patients | CKD stages 4 or 5 | 6–13 years | 2 main themes: (1) the significance of dealing with the disease in everyday life and (2) the disease leaves a number of marks |

| Agerskov et al. 2020 [18] | Denmark | Qualitative: semi-structured individual interviews | 7 mothers and fathers, 5 siblings and 5 patients | CKD stages 4 or 5 | 6–18 years | Felt alone, worried, and neglected; monitored, worried about and felt empathy for sibling including special ties and togetherness with sibling |

| Agerskov et al. 2021 [19] | Denmark | Qualitative: semi-structured individual interviews | 7 siblings | CKD stages 4 or 5/post-transplant | 7–13 years | 3 main themes: (1) illness in the background, (2) concerned for and taking care of sibling, (3) importance of bonds with relatives or adults |

| Altschuler et al. 1991 [15] | UK | Qualitative: semi-structured individual interviews | 6 families | CKD | Unknown | Parents reported neglect of siblings |

| Batte et al. 2006 [4] | UK | Mixed: semi-structured individual interviews and SCASa | 15 siblings | CKD/post-transplant | 8–12 years | No differences in comparisons between siblings and norms on anxiety scale. Expressed concerns about separation from parents & patient health; felt protective toward patient & need to be more grown up |

| Fielding et al. 1985 [13] | UK | Quantitative: School behavior problems reported by teachers | 15 siblings | CKD/post-transplant | Unknown | No differences in comparisons between siblings and patients or age matched school control group |

| Karabudak et al. 16 | Turkey | Qualitative: semi-structured individual interview | 10 siblings | CKD stages 4 or 5 | 12–19 years | Main themes included: (1) Information and opinions, (2) Changes, including emotional responses, and (3) Solutions |

| Velasco et al. 14 | Argentina |

Quantitative: KIDSCREEN-52b |

50 siblings | Post-transplant | 8–18 years | Siblings reported lower physical well-being, financial resources, parent relations/home life and autonomy than controls |

aSpence Children’s Anxiety Scale; bHealth-related quality of life measure

Quantitative findings

Findings from two studies found that siblings were not significantly more anxious in comparison to clinical norms on the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale [4] and did not demonstrate significantly more behavioral problems at school than a control group of same age peers as reported by teachers using a behavioral rating scale [13]. In contrast, a more recent study that utilized a standardized self-report health-related quality of life measure (KIDSCREEN-54) which assessed ten dimensions found that siblings reported significantly lower autonomy (opportunities to create leisure and social time) and financial resources (perceptions of their own financial resources, such as enough money to do the same activities as their friends), but higher social acceptance (feeling less rejected by peers) in comparison to children with CKD [14]. In comparison to controls, siblings reported lower physical well-being (level of physical activity, energy and fitness), lower autonomy, lower parent relations and home life (quality of parent–child relationships and atmosphere at home), and lower financial resources [14].

Qualitative findings

Four broad themes emerged from the qualitative studies, including: (1) family functioning, (2) significant relationships, (3) sibling psychological well-being, and (4) sibling coping strategies. Family functioning included two subthemes of: (a) disruption to routine, and (b) adherence. Significant relationships included the subthemes of: (a) siblings, (b) parents, (c) grandparents, and (d) friends. See Table 2 for a summary of broad themes.

Table 2.

Synthesis of themes across qualitative and mixed-methods publications

| Theme | Study reference number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

| Significant relationships | ||||||

| Parents | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Siblings | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Grandparents | • | • | ||||

| Friends | • | • | • | |||

| Family functioning | ||||||

| Disruption to routine | • | • | • | |||

| Adherence | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Psychological well-being | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Coping strategies | • | • | ||||

Family functioning

Disruption to routine

One major characteristic of family functioning was the disruption to routine for siblings (e.g., school activities) and for the entire family (e.g., family time together) when the health of the child with CKD declined, and particularly when they were hospitalized [4, 16, 17, 19]. For lower income families, hospitalization could result in siblings temporarily or even permanently leaving school to assume greater responsibilities at home, but this effect was gendered and impacted older sisters only [16]. Disruption to family vacation, especially travel, due to hospitalization or treatment demands (e.g., dialysis) was also identified in several studies [4, 17, 19].

Adherence

Another major characteristic of family functioning was the impact of medication or treatment adherence (or lack of adherence) by the child with CKD on the family, which was expressed in several ways. Parent–child conflict regarding non-adherence created stress and heightened concerns for siblings [17, 19]. Any noticeable lack of adherence escalated sibling anxieties about disease progression [17–19] and sometimes provoked an angry reaction from siblings [16]. Finally, some siblings felt responsible for and tried to encourage adherence during their caregiving activities [16].

Significant relationships

Siblings

Most siblings expressed considerable concern for their sister or brother with CKD; fear, worry and anxiety were noted in seven of the selected studies. Concerns ranged from side effects due to treatment (e.g., damage caused by fistulas) [16] to disease progression and mortality risk [4]. Some siblings reported physical symptoms accompanying their fear or anxiety, including increased heart rate [16]. Many reported paying close attention to the well-being of their brother or sister with CKD [17], with their concerns typically exacerbated either by non-adherence (e.g., nutrition or medication) [16] or by hospital admission [16–19].

Siblings reported caring and positive relationships with their sister or brother with CKD [16], as well as feeling protective of them [4, 16]. Siblings valued the time spent and activities they engaged in with them, but felt constrained by their symptoms and fatigue [16, 18]. Feelings of jealousy concerning the time and attention parents spent on and with their brother or sister with CKD was common [4, 16, 17, 19]. Parents reported that, when the child with CKD was hospitalized, those siblings who remained at home enjoyed their time together [18]. Lastly, as noted above, some siblings reported engaging in caregiving for their sister or brother with CKD, which involved a variety of activities including accompanying them on medical visits, assisting with nutrition and medication, and helping with schoolwork [16].

Parents

Without exception, siblings in each of the qualitative studies felt overlooked and neglected by parents at times, but particularly when their sister or brother with CKD was hospitalized [4, 17–19]. This was less the case if siblings spent time at the hospital with the parent, including overnight stays [19]. Most siblings indicated that their brother or sister with CKD was overprotected and shown more interest by parents, and that parents tolerated their misbehavior to a greater extent [16–18]. Siblings also felt overlooked when parents paid special attention to relationships outside the home (e.g., with teachers at school) for the child with CKD but not for themselves [18].

Grandparents

Only one study investigated the role of grandparents, and found that this relationship was particularly important for siblings, as it provided a sense of security and familiarity, especially when the child with CKD was hospitalized and parents were less available [18]. Parents reported that grandparents were an important source of support for siblings and provided special attention when serious health events occurred [18].

Friends

Some siblings reported that their social activities with friends were curtailed [16], and that social comparisons made with friends were negative; specifically, family trips and holidays were disrupted or missed [4, 16, 19]. Other siblings reported that talking to friends or peers could be an important source of support [16, 19].

Psychological well-being

Some siblings reported feeling they had to be more mature than others their age [4], in addition to the feelings of fear, anxiety and neglect outlined above. Some reported feeling hope and optimism concerning their sister or brother with CKD’s illness [16], while others were worried about their own and their parents’ mortality [4]. As outlined above, negative social comparisons with friends, combined with feelings of jealousy of the patient and feeling overlooked by parents were consistent themes across the selected studies. Finally, also as noted above, siblings felt stressed and anxious by conflicts between parents and their brother or sister with CKD concerning adherence.

Coping strategies

Some siblings indicated that they were not as fully informed about details of the status of their sister or brother’s illness as they wished, including reasons underpinning the CKD diagnosis as well as realistic information about the course of the disease and treatment [4, 16]. Others valued and paid close attention to information about the progress of the disease, including specific blood and urine test results, when it was provided [17, 19]. Additional strategies included trying to behave in a more mature manner than peers [4, 16], sharing experiences with friends or peers [16], talking to the patient or parents about the situation [4], engaging in activities [16], and expressing negative feelings or praying when alone [16].

Synthesis of quantitative and qualitative findings

Taken together, the results of both qualitative and quantitative sources of data synergistically provided insights that would not arise from the use of either source alone; some findings converged, while others diverged. For example, several qualitative studies indicated that siblings felt considerable concern for their sister or brother with CKD, accompanied by fear, worry and anxiety; these findings diverged from the results of a quantitative study that indicated siblings did not report significantly greater anxiety than norms. While concern for their brother or sister with CKD may or may not contribute to generalized feelings of anxiety for siblings, the small sample size may have precluded the ability to detect differences.

Qualitative and quantitative studies converged in several ways. A quantitative study found that siblings reported the quality of their relationships with parents and the atmosphere at home was significantly worse than the control group. Qualitative studies echoed siblings’ feelings of being overlooked and neglected by parents. Both types of studies also found that siblings reported that their opportunities for leisure and social activities were restrained. Other issues were addressed by one type of study only. For instance, siblings’ perceptions of their personal financial resources, social acceptance by peers, and perceptions of their physical well-being, such as energy and physical activity level, were addressed using quantitative methods only [14]. The quality of sibling relationships including the brother or sister with CKD, as well as with other siblings in the household, was addressed by qualitative methods only. In summary, the results of this scoping review indicated that siblings of children with CKD were significantly affected by their circumstances in a variety of ways, with the impact felt especially deeply in their family relationships, as well as affecting their psychological well-being.

Discussion

Overall, our scoping review provided an emerging picture of the experiences and well-being of siblings of children with CKD. We identified four broad themes across qualitative and mixed-methods studies, including family functioning, significant relationships, psychological well-being, and coping strategies; synthesis analyses further revealed how the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies converged and diverged. Overall, our review detected several unmet needs of siblings of children with CKD, as well as gaps in the literature that need to be addressed by future research.

The theme of family functioning included two subthemes of disruption to routines and adherence. Daily routine disruptions were most likely to occur when the child with CKD was hospitalized, while broader restrictions of family activities, such as taking a vacation or travel, were due to treatment demands or availability. Disruptions to routine are common for families of children with chronic conditions [5]; however, missing out on shared family time during vacation or travel experiences may be more specific to families who manage significant daily treatment demands such as peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis [5, 6]. The importance of maintaining family routines and rituals for adaptive individual and family functioning and resilience has been well established [20]. Therefore, the significance of these disruptions for siblings should not only be acknowledged, but mitigated as much as possible. Some siblings expressed anger about conflicts between their parents and their brother or sister with CKD concerning medication, diet and other non-adherence issues. While the psychosocial and medical consequences of non-adherence for young people with CKD [21, 22] and their parents are well documented, the consequences for siblings are less well understood. Developmental research has shown that prolonged exposure to chronic interparental conflict can exacerbate adjustment issues for children and adolescents [23]. It is currently unknown if exposure to chronic parent–child conflict about non-adherence can also amplify sibling psychosocial adjustment issues; future research needs to address this issue.

Significant relationships were also a main theme, which included the subthemes of sibling, parent–child, grandparent and friend sibling relationships. The importance of sibling relationships emerged frequently across studies, and included both positive and negative aspects of the relationship. It should be noted that most studies focused on the relationship between one target sibling and their brother or sister with CKD, with other sibling relationships within the family rarely addressed. Regardless of their age, siblings were well aware of and sensitive to the health status of their sister or brother with CKD; this included closely monitoring their adherence to medication and self-care practices. Some siblings actively participated in caregiving — some to the degree where it significantly curtailed their ability to spend time with friends or attend school [16]. In contrast, recent research has suggested that caretaking by siblings may benefit their own well-being [24]. This difference may be due to variation in relationship norms and expectations based on ethno-cultural or societal differences. It should be noted that the eight selected studies were conducted in four countries where these norms may have varied considerably. Taken together, these findings highlighted sibling warmth and prosocial interaction [25] in families affected by CKD, which may not only enhance the quality of the sibling relationship [24] but also siblings’ resilience characteristics and behaviors.

Negative aspects of the sibling relationship were also identified. Feelings of jealousy concerning the greater time and attention their brother or sister with CKD received from parents were especially striking across studies. Past research on children’s perceptions of parental differential treatment (PDT) in families affected by chronic illness is congruent with our findings [5, 6]. What remains unknown is how sibling perceptions of PDT are related to their own well-being or to their relationship with their sister or brother with CKD. While research examining family-related risk factors for psychological functioning of pediatric kidney transplant patients have routinely included parental psychosocial functioning, few if any have investigated the potential impact of sibling well-being for patient mental and physical health outcomes [2]. Sibling perceptions of PDT may also negatively impact the quality of the sibling relationship, as well as erode the quality of the parent–child relationship over time [26]. These issues need closer attention from researchers.

The parent–child relationship was also an important relationship subtheme. As noted, parental differential treatment was a highly salient issue for siblings, particularly when parents were physically absent from the home due to hospitalization of their child with CKD. However, this concern was somewhat mitigated if they were included in care, including overnight hospital stays. Unfortunately, not all hospitals accommodate overnight stays for family members, and during the COVID-19 pandemic hospital visitations have often been canceled or restricted to a single family member, exacerbating the negative impact of family separations [27]. Findings of qualitative and quantitative studies converged to show that siblings of children with CKD perceived the quality of their relationships with parents and the atmosphere at home to be significantly poorer than siblings in unaffected families. Previous research has found that parents are aware of sibling differential treatment concerns, and worry about feelings of jealousy and neglect [22]. How parents address and reduce sibling perceptions of PDT in families affected by CKD would be critically important — not only for sibling well-being [28], but also for the quality of the sibling and parent–child relationships and family functioning overall. While some previous interventions targeting families of children with chronic conditions have addressed the quality of communication between family members [29], it is less common for sibling-specific issues such as PDT to be addressed, and even more rare for the quality of the sibling relationship itself to be investigated [30].

Grandparents and friends were also significant relationships for siblings, although both were investigated less often than parents. In one study, grandparents were familiar caregivers who offered support and security when parents were less available. Friends also offered social support; however, the curtailment of social activities or negative social comparisons had a negative impact on siblings. Although norms and expectations for grandparents and friends may vary due to ethno-cultural or societal differences, both relationships have significant potential for promoting resilience in siblings of children with CKD [31], and should be studied in greater depth in future research.

Across all of the studies reviewed, sibling psychological well-being was primarily addressed using a risk or deficit-approach rather than a strength-based perspective that incorporated aspects of resilience and/or posttraumatic growth [32]. The focus of sibling psychological well-being typically included a variety of negative feeling states, including anxiety, fear, frustration, jealousy, and anger. Anxiety has been identified in past reviews [5, 6] as an important issue for siblings of children with chronic conditions, although siblings were not found to be significantly more anxious than controls in the selected quantitative studies. However, it should be noted that quantitative studies characterized by small sample sizes did not find significant results, while more recent work using larger samples did find significant differences in self-reported quality of life between siblings and controls.

While other researchers have found that siblings reported depressive [5] or traumatic stress symptoms [33], these adjustment issues were not found in the present review as they were not assessed either by standardized measures or identified by qualitative themes. While some mediators or moderators of sibling psychosocial adjustment in families affected by chronic illness have been identified, such as caregiving responsibilities [24] and perceptions of differential parental treatment [24], further work is needed to identify factors that influence the psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with CKD.

Positive aspects of sibling psychological well-being were noticeably absent from the selected studies, with feelings of hope and optimism reported in just one study. Resilience has not been widely studied in siblings [34] or in families of children with chronic conditions [10, 35] which may contribute to pathologizing of the experience of living with a brother or sister with a chronic illness or life-limiting condition. To date, the quantitative assessment of resilience has been limited to the absence of adjustment problems [34] or low risk profiles of adjustment [36] in families affected by chronic illness; however, more direct assessments of individual resilient characteristics, behaviors and traits and family resilience are emerging in the literature [37]. Clearly, more research is needed to address positive aspects of sibling well-being and adjustment in families affected by CKD.

Several sibling coping strategies were identified in the present review. Coping strategies are broadly viewed as either active, in that they are problem-focused and oriented toward altering the situation or the thoughts or emotions in response to a stressful situation, or avoidant, in that they are oriented toward staying away from the problem or repressing thoughts or feelings about it [38]. Both types were found; siblings engaged in active coping by seeking emotional, instrumental, and informational support, as well as avoidant coping by using activities for distraction. Overall, these strategies mirrored some previous findings of siblings of children with chronic illness [5], although it should be noted that some siblings avoided discussing their concerns with their parents for fear of increasing stress or sadness [6]. Factors influencing sibling coping strategies such as parental coping strategies, and the availability of supportive relationships and support systems outside the home [31] need to be addressed in future research.

Limitations

While our search strategy was designed to capture all relevant studies, it is possible that some were missed. For example, siblings of children with CKD may have been included in research focusing more broadly on family well-being, which may not have been identified through our review process. It should be noted that three qualitative studies that were included in our review drew participants from the same sample of families; therefore, similarities in themes across these studies should be interpreted with caution. In addition, because of the limited number of studies identified, synthesis analyses addressing convergence and divergence between qualitative and quantitative studies were limited.

Implications for practitioners

The present review identified several unmet needs of siblings of children with CKD that have important implications for practitioners. Siblings’ desire for more information about the etiology and course of CKD, as well as regular updates about their sister or brother’s condition emerged as a significant unmet need that could be addressed through developmentally appropriate educational materials, as well as through parent education. Elevated levels of anxiety were frequently discussed, therefore early and ongoing screening [39] for anxiety and other psychosocial adjustment concerns (e.g., depression, traumatic stress) would be useful to help identify those who are in need of support from a mental health professional as early as possible.

While some siblings used effective coping strategies, other less beneficial strategies for long-term mental health were also identified. Therefore, interventions concerning effective coping strategies offered by sibling support groups, individual programming with hospital-based child life specialists or social workers, and/or annual events such as summer camps, may be beneficial for siblings [40]. These supports should also emphasize minimizing disruptions to family routine, as well as sibling concerns regarding parent–child conflict about adherence issues. Given that recent findings indicated a substantial minority of parents and children with CKD experience posttraumatic stress [41], it makes sense to adopt a trauma-informed approach for programming with siblings of children with CKD [42]. Currently, there are a handful of interventions that focus on the needs of siblings of children with illnesses or disorders [43]; however, these programs commonly target parent–child communication which may or may not address sibling perceptions of PDT. Given the marked negative perceptions of PDT by siblings across the studies reviewed and the potential for significant negative impact on sibling psychosocial adjustment and the quality of family relationships, addressing PDT should be a high priority in any educational or support program designed for siblings in families affected by CKD.

Future research directions

Based on our findings, more in-depth investigations of mediators and moderators that influence the psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with CKD are needed, including parental mental health, resilience, and coping styles. Parent–child conflict management style concerning adherence, as well as strategies for minimizing disruptions to routine also emerged as significant directions for future research. Perhaps even more importantly, if or how parents engage with siblings regarding their perceptions of PDT needs further exploration, as do differences in perceptions of PDT across children in the family and how these perceptions impact their well-being [26]. A longitudinal examination of the development and effectiveness of sibling coping strategies needs to be undertaken, as well as the availability of supportive relationships within the family and support systems outside the home. Related to supports, research addressing positive aspects of sibling well-being in families affected by CKD, including aspects of individual, relational and family resilience, as well as posttraumatic growth, is sorely needed. Given that only one of the selected studies utilized a mixed–methods approach, more studies incorporating both qualitative and quantitative methods with larger and more diverse samples should be undertaken. Research also needs to address differences in timing of diagnosis (e.g., at birth as compared to during childhood) as well as the timing of transplant, including the potential role of siblings as pediatric donors, although this is rare [44]. Gender and cultural differences were not addressed in the studies reviewed due to small sample sizes; therefore, future work should be conducted in a variety of geographic locations and take ethno-cultural influences into account. Potential sources of stress for families, such as socioeconomic strain, geographic relocation for health care, adaptation as a refugee or newcomer family, and experiences of systemic racism within the health care system are also important factors influencing the well-being of siblings that future research should address [45].

In summary, the results of our scoping review confirmed that the experiences and well-being of siblings of children with CKD are under-studied. Based on the emerging literature identified, it was clear that siblings were negatively affected in a variety of ways, particularly in their family relationships and their psychological well-being. It remains for future research to explore how siblings may be positively impacted, and if long-term growth and development are facilitated by their challenges.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOCX 31.7 kb)

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The literature search was performed by DJ, and study selection was performed by DJ, MW and CP. Synthesis analyses were performed by CP and the first draft of the manuscript was written by CP. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Harambat J, van Stralen K, Kim J, Tizard E. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1939-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amatya K, Monnin K, Christofferson E. Psychological functioning and psychosocial issues in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2021;25:e13842. doi: 10.1111/petr.13842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: a review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics. 2008;121:349–360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batte S, Watson A, Amess K. The effects of chronic renal failure on siblings. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:246–250. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lummer-Aikey S, Goldstein S. Sibling adjustment to childhood chronic illness: an integrative review. J Fam Nurs. 2021;27:136–153. doi: 10.1177/1074840720977177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tay J, Widger K, Stremler R. Self-reported experiences of siblings of children with life-threatening conditions: a scoping review. J Child Health Care. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13674935211026113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer A, Blanchette E, Zimmerman C, Wightman A. Caregiver burden in pediatric dialysis: application of the paediatric renal caregiver burden scale. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;36:3945–3951. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein R, Bauman L, Westbrook L, Coupey S, Ireys H. Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: the case for a new definition. J Pediatr. 1993;122:342–347. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)83414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein R, Silver E. Operationalizing a conceptually based noncategoriacl definition: a first look at US children with chronic conditions. JAMA Pediatr. 1999;153:68–74. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu Y, Xu L, Pan Y, He C, Huang Y, Xu H, Lu Z, Dong C. Family resilience, parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment of children with chronic illness: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:646421. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.646421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levac D, Coquhoun H, O'Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fielding D, Moore B, Dewey M, Ashley P, McKendrick T, Pinkerton P. Children with end-stage renal failure: psychological effects on patients, siblings and parents. J Psychosom Res. 1985;29:457–465. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velasco J, Ferraris J, Eymann A, Ghezzi L, Coccia P, Ferraris V. Health-related quality of life among siblings of kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24:e13734. doi: 10.1111/petr.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altschuler J, Black D, Trompeter R, Fitzpatrick M, Peto H. Adolescents in end-stage renal failure: a pilot study of family factors in compliance and treatment considerations. Family Syst Med. 1991;9:229–247. doi: 10.1037/h0089149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karabudak S, Conk Z. Phenomenological determination of biopsychosocial effects of diseased child under dialysis treatment on siblings in Turkey. HealthMED. 2012;6:4194–4202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agerskov H, Thiesson H, Pedersen B. Everyday life experiences in families with a child with kidney disease. J Ren Care. 2019;45:205–211. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agerskov H, Thiesson H, Pedersen B. The significance of relationships and dynamics in families with a child with end-stage kidney disease: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:987–995. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agerskov H, Thiesson H, Pedersen B. Siblings of children with chronic kidney disease: a qualitative study of everyday life experiences. J Ren Care. 2021;47:242–249. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrist A, Henry C, Liu C, Morris A (2019) Family resilience: the power of rituals and routines in family adaptive systems. In: APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan. Volume 1, edn. Edited by Fiese B, Celano M, Deater-Deckard K, Jouriles E, Whisman M. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; pp 223–239

- 21.Rich K, Johnson S, Cousino M (2021) Psychosocial adjustment and adherence to prescribed medical care of children and adolescents on dialysis. In: Pediatric Dialysis. edn. Edited by Warady B, Alexander S, Schaefer F. Switzerland: Springer

- 22.Tong A, Lowe A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics. 2008;121:349–360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Eldik W, de Haan A, Parry L, Davies P, Lujik M, Arends L, Prinzie P. The interparental relationship: meta-analytic associations with children’s maladjustment and responses to interparental conflict. Psychol Bull. 2020;146:553–594. doi: 10.1037/bul0000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelada L, Wakefield C, Drew D, Ooi C, Palmer E, Bye A, De Marchi S, Jaffe A, Kennedy S. Siblings of young people with chronic Illness: caring responsibilities and psychosocial functioning. J Chlld Health Care. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13674935211033466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes C, McHarg G, White N. Sibling influences on prosocial behavior. Currr Opin Psychol. 2018;20:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen A, McHale S. Mothers', fathers', and siblings' perceptions of parents' differential treatment of siblings: links with family relationship qualities. J Adolesc. 2017;60:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hugelius K, Harada N, Marutani M. Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;121:104000. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fredriksen T, Vatne T, Haukeland Y, Tudor M, Fjermestad K. Siblings of children with chronic disorders: family and relational factors as predictors of mental health. J Child Health Care. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13674935211052157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith M, Pereira S, Chan L, Rose C, Shafran R. Impact of well-being interventions for siblings of children and young people with a chronic physical or mental health condition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2018;21:246–265. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fullerton J, Totsika V, Hain R, Hastings R. Siblings of children with life-limiting conditions: psychological adjustment and sibling relationships. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;43:393–400. doi: 10.1111/cch.12421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Incledon E, Williams L, Hazell T, Heard T, Flowers A, Hiscock H. A review of factors associated with mental health in siblings of children with chronic illness. J Child Health Care. 2015;19:182–194. doi: 10.1177/1367493513503584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klippenstein A, Piotrowski C, Winkler J, West C. Growth in the face of overwhelming pressure: a narrative review of sibling donor experiences in pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Child Health Care. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13674935211043680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alderfer M, Logan B, DiDonato S, Jackson L, Hayes M, Sigmon S. Changes across time in cancer-related traumatic stress symptoms of siblings of children with cancer: a preliminary investigation. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2020;27:48–53. doi: 10.1007/s10880-019-09618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brennan C, Hugh-Jones S, Aldridge J. Paediatric life-limiting conditions: coping and adjustment in siblings. J Health Psychol. 2012;18:813–824. doi: 10.1177/1359105312456324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenthal E, Gillette S, DuPaul G. Pediatric siblings of children with special health care needs: well-being outcomes and the role of family resilience. Chldren's Health Care. 2021;50:452–465. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2021.1933985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharkey C, Schepers S, Drake S, Pai A, Mullins L, Grootenhuis M. Psychosocial risk profiles among American and Dutch families affected by pediatric cancer. J Pedatr Psychol. 2020;45:463–473. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaaniste T, Cuganesan A, Chin W, Tan S, Coombs S, Heaton M, Cowan S, Aouad P, Potter D, Smith P, et al. Living with a child who has a life-limiting condition: the functioning of well-siblings and parents. Child Care Health Dev. 2022;48:269–276. doi: 10.1111/cch.12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazak A, Hwang W, Chen F, Askins M, Carlson O, Argueta-Ortiz F, Barakat L. Screening for family psychosocial risk in pediatric cancer: validation of the Psychosocial Asessment Tol (PAT) version 3. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018;43:737–748. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKenzie Smith M, Pinto Pereira S, Chan L, Rose C, Shafran R. Impact of well-being interventions for siblings of children and young people with a chronic physical or mental health condiction: a systematic review and analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2018;21:246–265. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hind T, Lui S, Moon E, Broad K, Lang S, Schreiber R, Armstrong K, Blydt-Hansen T. Post-traumatic stress as a determinant of quality of life in pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2021;25:e14005. doi: 10.1111/petr.14005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piotrowski CC. ACEs and trauma-informed care. In: Asmundson G, Afifi T, editors. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Using Evidence to Advance Research, Practice, Policy and. Prevention. New York: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haukeland Y, Czajkowski N, Fjermestad K, Silverman W, Mossige S, Vatne T. Evaluation of “SIBS”, an intervention for siblings and parents of children with chronic disorders. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29:2201–2217. doi: 10.1007/s10826-020-01737-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ralph A, Butow P, Hanson C, Chadban S, Chapman J, Craig J, Kanellis J, Luxton G, Tong A. Donor and recipient views on their relationship in living kidney donation: thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69:602–616. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Genereux D, Fan L, Brownlee K. The psychosocial and somatic effects of relocation from remote Canadian First Nation communities to urban centres on indigenous peoples with chronic kidney disease (CKD) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3838. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 31.7 kb)