Abstract

Introduction

An online interactive repository of available medication adherence technologies may facilitate their selection and adoption by different stakeholders. Developing a repository is among the main objectives of the European Network to Advance Best practices and technoLogy on medication adherencE (ENABLE) COST Action (CA19132). However, meeting the needs of diverse stakeholders requires careful consideration of the repository structure.

Methods and analysis

A real-time online Delphi study by stakeholders from 39 countries with research, practice, policy, patient representation and technology development backgrounds will be conducted. Eleven ENABLE members from 9 European countries formed an interdisciplinary steering committee to develop the repository structure, prepare study protocol and perform it. Definitions of medication adherence technologies and their attributes were developed iteratively through literature review, discussions within the steering committee and ENABLE Action members, following ontology development recommendations. Three domains (product and provider information (D1), medication adherence descriptors (D2) and evaluation and implementation (D3)) branching in 13 attribute groups are proposed: product and provider information, target use scenarios, target health conditions, medication regimen, medication adherence management components, monitoring/measurement methods and targets, intervention modes of delivery, target behaviour determinants, behaviour change techniques, intervention providers, intervention settings, quality indicators and implementation indicators. Stakeholders will evaluate the proposed definition and attributes’ relevance, clarity and completeness and have multiple opportunities to reconsider their evaluations based on aggregated feedback in real-time. Data collection will stop when the predetermined response rate will be achieved. We will quantify agreement and perform analyses of process indicators on the whole sample and per stakeholder group.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval for the COST ENABLE activities was granted by the Malaga Regional Research Ethics Committee. The Delphi protocol was considered compliant regarding data protection and security by the Data Protection Officer from University of Basel. Findings from the Delphi study will form the basis for the ENABLE repository structure and related activities.

Keywords: health informatics, public health, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The diverse expertise and geographical spread of the European Network to Advance Best practices and technoLogy on medication adherencE COST Action members (39 European countries) and their wider professional network represents a unique and timely opportunity to develop a repository of medication adherence technologies that meets the needs of a diverse audience.

The scope and content of the Delphi survey represent the work of extensive literature review combined with multidisciplinary expertise of the steering committee.

The real-time Delphi approach provides improved efficiency of the process, shortens the time of study completion and is particularly suitable for managing larger groups and including people from different geographic locations.

The Delphi study will use state-of-the-art methodology to measure agreement and predetermine agreement/consensus criteria as well as stability of responses.

The real-time approach requires specialised software, which limits the range of possible survey configurations and raw data availability for detailed process analyses and requires relatively elaborate instructions for participants, which may increase participation burden.

Introduction

Taking medication as prescribed often proves difficult for people when managing their health, particularly in the long term.1 Medication adherence is suboptimal in numerous chronic conditions2 3 and has a negative impact on chronic disease management, patient’s general health status, quality of life, working ability and healthcare costs.2 4 5 Research on medication adherence has expanded and contributed to raised awareness of the prevalence of suboptimal adherence and how it affects health outcomes. Digital technologies have increasingly gained interest as new interventions for supporting medication adherence have been developed. A diversity of technologies has been proposed, from electronic monitoring devices to mobile applications, to support medication adherence measurements and empower patients with their disease management. However, the rapidly expanding offer of medication adherence technologies (MATech) makes it increasingly difficult to access, evaluate and compare different technologies to make informed decisions and select appropriate tools for specific clinical or research needs. In a 2018 review by Ahmed et al,6 5881 medication adherence apps were identified on Google Play and Apple App Stores. However, most of them lacked evidence of effectiveness and did not involve healthcare professionals (HCPs) during their development.6 Lack of collaboration between stakeholders results in a limited number of developed MATech actually being implemented into the healthcare systems and used daily by HCPs and/or patients.7 Furthermore, due to differences in healthcare systems across countries, healthcare organisations and reimbursement processes, harmonisation of implementation strategies are lagging behind, which further delays adoption of best practices across countries.4 7

The ENABLE COST Action (‘European Network to Advance Best practices and technoLogy on medication adherencE’, CA19132)8 was initiated by experts in medication adherence and digital technologies to fill these gaps regarding evidence and implementation of MATech within healthcare systems. ENABLE aims to raise awareness of available technologies, expand multidisciplinary knowledge on medication adherence at multiple levels, accelerate knowledge translation to clinical practice and collaborate towards economically viable implementation of best practices and technologies across European healthcare systems. These objectives are being pursued within a 4-year period (2020–2023), by three distinct and inter-related working groups (WGs) that map best practices available (WG1), identify and showcase adherence technologies (WG2) and identify suitable reimbursement strategies for implementation in healthcare systems (WG3), supported transversally by a WG4 coordinating communication and dissemination. At present, the ENABLE Action includes a large interdisciplinary network of experts in medication adherence from 39 European countries.8

Effective implementation of technology-supported healthcare has been facilitated by centralisation of information in public repositories or ‘solution showrooms’, where users can search for technologies that meet their specific requirements.9 Several such repositories already exist in the field of digital health, including medication adherence (eg., NHS app Library,10 MyHealthApps,11 InterventieNet,12 GGD AppStore,13 DIGA,14 Weisse Liste15), but are limited to single countries or types of technology and none represents a comprehensive resource to facilitate adoption of appropriate MATech across health systems. Therefore, ENABLE sets out to develop and maintain a public online repository of MATech where patients, HCPs, researchers and healthcare managers would be able to access and select technologies for adoption in their adherence management activities.8 For example, a patient may be interested more in the practical benefits of using a MATech in their daily lives, while a researcher may be keen to examine in detail the methodology theory and evidence base behind the MATech development. To meet this goal, the ENABLE repository would need to represent a flexible knowledge management system that would include information relevant to the needs of different stakeholders in a user-friendly format. In medical informatics, knowledge management relies on standardised terminologies, classifications and ontologies to record, share and use data on healthcare research and practice. These standards specify the types of information to encode in the form of distinct ‘entities’ representing objects or phenomena in the real world and their properties (‘attributes’), thus enabling knowledge generation through inference and learning.16 Adoption of evidence-based health innovations is also facilitated by these common standards, as new technologies need to interact with existing ecosystems in terms of both data interoperability and communicating with potential users in appropriate domain-specific language.17

The field of medication adherence is highly interdisciplinary, therefore a useful repository would cross multiple knowledge domains and align with several standards, whether medical (eg., WHO International Classification of Disease18), behavioural (eg., the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology (BCIO)19 20) or technical (eg., WHO Classification of Digital Health Interventions21). Stakeholder involvement would need to be at the core of this development process, to ensure its content is relevant, clear and complete, and meets community needs.22 The diverse and geographically spread ENABLE membership and their wider professional network represents a unique and timely opportunity to conduct this work. Considering these quality standards and following methodological recommendations,22–24 the initial version of the repository structure was prepared. A stakeholder consultation process is proposed to explore their views and level of agreement on the relevance, clarity and completeness of the initial version.22 23 The resulting improved version would represent the structure of the ENABLE repository, which will be tested and populated in subsequent steps with users and developers of available technologies.

The present manuscript describes two elements:

The proposed structure for the repository.

The protocol of the real-time Delphi study to explore stakeholder views on this structure.

Methods and analysis

Steering committee

A steering committee (SC) was established within the COST ENABLE WG2 to coordinate and perform the work. The committee includes 11 ENABLE members from 9 countries in the following areas of expertise: adherence research and education, clinical practice, policy making and technology development. Members are responsible for: (i) determination of the repository scope and framework of attributes defining repository structure, (ii) preparation of the Delphi protocol, (iii) configuration and piloting the Delphi survey, (iv) selection and invitation of stakeholders to participate in the study, (v) moderating study performance via the online tool and (vi) analysis and interpretation of results.

Determining the repository scope and framework of attributes defining its structure

The determination of scope and development of the attributes’ labels with definitions aimed to align with ontology development procedures as described by Wright et al 24 and follow a stakeholder engagement methodology as described by Norris et al 22 and Khodyakov et al.25 The principles of ontology development, actions taken when generating the framework of attributes and examples of how these principles are applied in the ENABLE project are presented in table 1. The stakeholder engagement is primarily achieved through the proposed real-time Delphi study, which is described in more detail in the next sections.

Table 1.

Principles of ontology development after Wright et al 24 and actions taken in the ENABLE project

| Principles | How they have been applied in the ENABLE project |

| Have specified scope and scientifically sound and relevant content | Selection of established definitions for delimiting the scope, consultation of stakeholders, piloting for data input and platform search. |

| Meet the needs of community of users | Consultation of stakeholders, steering committee and Action members sampled from the user community and including diverse areas of expertise. |

| Enabling users to understand the meaning of entities | Naming examples of existing ontologies, piloting Delphi survey, technology description form, user form and platform use. |

| Be logically consistent | Using the methodology recommended for attribute description, checking consistency via Ontology Web Language. |

| Be interoperable with existing ontologies | Adopting attributes and labels available in existing ontologies and classifications, expert input on additional attributes and recommendations for interoperability. |

| Reflect changes in scientific consensus and remain accurate over time | Repository in open access, sustainability plan developed with Action members and stakeholders. |

ENABLE, European Network to Advance Best practices and technoLogy on medication adherencE.

Scope and definition of MATech

Four established definitions were used to define the scope of repository and set the framework of attributes: (i) WHO definition of health technologies 26; (ii) the ABC definition of medication adherence 1; (iii) the WHO definition of adherence to long-term therapies 2 to highlight the importance of shared decision-making between the patient and the healthcare team and (iv) the definition of best practice in healthcare proposed by the European Commission to guide improvements in European health systems.27 The information in this definition denotes evidence on safety, efficacy, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, appropriateness, social and ethical values and quality of the healthcare interventions.

Therefore, we propose to define MATech as devices, procedures or systems developed based on evidence to support patients to take their medications as agreed with healthcare providers (ie, to initiate, implement and persist with the medication regimen).

Devices, procedures or systems emphasise the inclusion of all technologies, irrespective of their mode of delivery (whether based on electronic or printed supports, delivered through human interaction or a combination of these), with the aim to construct a comprehensive repository in which users can identify diverse technologies to fit their potentially diverse needs.

Developed based on evidence encompass the requirement of evidence/research that supports at least a potential contribution to either measurement or intervention on medication adherence (eg, validation or pilot studies). Thus, technologies that are not (yet) supported by evidence (eg., development and testing stages), or clinical practice protocols without an evidence base on at least one aspect (safety, efficacy, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, appropriateness, social and ethical values or quality), will not be (yet) included in the repository until such evidence is produced and reported.

Support patients to take their medications as agreed with the healthcare providers (ie, to initiate, implement and persist with the medication regimen) encompass the contribution of the technology to medication adherence management—either directly in patients’ self-management, or by supporting professionals to offer such services to patients through all phases of medication adherence. Thus, technologies that focus on other medication management goals, but do not target adherence specifically would be out of scope for this repository.

Furthermore, the technologies included would need to be described in terms of their technical characteristics and validation, their behaviour change content, format and context, as well as the characteristics facilitating appropriate implementation in care processes. Hence, evidence from behaviour,19 28 implementation29 30 and computer sciences18 21 31 32 informed the initial scope and attributes framework to ensure key features, such as user-centeredness, trustworthiness/credibility, accuracy and relevance of the presented information, tailoring to the needs of different users and interoperability with existing evidence and other sources of information on healthcare technologies.

Framework of attributes

An initial list of attributes was developed based on a literature review and knowledge from the ENABLE members activities such as (i) an ongoing systematic review of e-health interventions on medication adherence for chronic conditions,33 (ii) a checklist of e-health quality criteria under development,34 (iii) Interventienet.nl—platform showcasing evidence-based medication adherence interventions in the Netherlands12 and (iv) the ABC taxonomy—consensus-based terminology and definitions of medication adherence.1

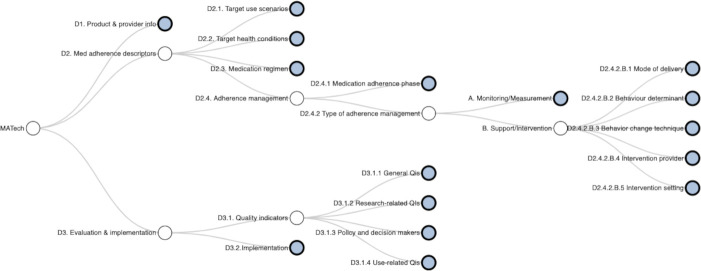

The initial list was presented to the SC and discussed via several videoconferences to generate a more detailed list of attributes grouped on several themes. Each theme was further elaborated by a subgroup of two SC members following a standard format including labels and adherence-related definitions. We adopted the approach from BCIO,19 where related attributes were searched in topic relevant ontologies/taxonomies/classifications and original definitions and codes were added. The reasons for the choice of certain attributes and labels were detailed for each attribute group. The proposed framework of attributes is graphically presented in figure 1 and, while rationale and sources used to define the labels for the MATech repository are presented in table 2 and online supplemental file 2.

Figure 1.

The interactive graph showing the framework of attributes for medication adherence technologies (MATech) (‘the MATech tree’). The MATech tree is available as interactive feature in the.

Table 2.

The proposed framework of attributes used in the MATech repository

| Domain and attribute group | Core question | Rationale | Existing ontology/taxonomy/classification used and adapted |

| D1 (D1.1) Product and provider information | What product does the entry refer to, who provides it, who entered its description in the repository and when? | Each entry in the ENABLE repository will refer to a unique product, which will be identified with a unique ID, provided by a unique organisation (manufacturer, developer) with its own unique ID and related metadata (eg, date of entry, verification process, etc) to present the identity of the described MATech and its provider. |

|

| D2.1 Target use scenario | What use scenarios and types of users is the technology intended for? | We can distinguish two general categories of users and their characteristics that might influence the choice of technology: (i) self-management use (patients and caregivers)—labels describing patients’ characteristics or their condition (age, functional status, (health) literacy, etc); (ii) adherence support use by healthcare or social care providers and health system managers, who can initiate a search for MATech to integrate in their practice. The provider and the setting are also the focus of separate attribute groups. | |

| D2.2 Target health conditions | Which health conditions could the technology be used for as part of adherence support? | MATech are usually developed and validated to be used in one or several clinical domains and potential users may search for technologies applicable to the health condition(s) they aim to manage. Since our stakeholders also include lay individuals, special focus was put on using simplified language to avoid misunderstandings and knowledge gaps. | |

| D2.3 Medication regimen | What type of medication regimen(s) is the technology intended for? | Medication regimen can take different schematic forms and be of varying complexity, which may influence the complexity and extent of medication adherence. MATech may be developed for medications with different characteristics, hence the repository users should be able to indicate the type of regimen to find a MATech that fits its specific characteristics. | |

| D2.4 Medication adherence management components | What adherence management types and phases does the technology target? | Management of adherence entails two management types, for example, monitoring/measurement (D2.4.2.A) and support/intervention (D2.4.2.B) by any stakeholder, including the patient himself. Both elements may require different approaches depending on the targeted phase of adherence (D2.4.1). |

|

| D2.4.2.A Monitoring/Measurement methods and targets | If measurement is a component, what measurement methods does the technology use and what do they measure? | A broad range of measurement methods for adherence are available. In addition to adherence behaviours, measurement can also target adherence determinants, other self-management behaviours and outcome measures (eg, HRQoL). Therefore, we have selected a range of measurement models as well as a selection of self-management behaviours to offer the possibility to describe technologies from a measurement perspective. | |

| D2.4.2.B.1 Intervention modes of delivery | If intervention is a component, how is it delivered to its users? | Mode of delivery is ‘physical or informational medium through which a given behaviour change intervention is provided’,19 can affect intervention effectiveness. Although digitalisation has entered in all aspects of everyday life, the analogue mode is still very relevant. This is especially true within the elderly, who on one hand require more support in medication adherence65 and are on the other hand less digitally literate.66 Hence, the repository should encompass all modes. | |

| D2.4.2.B.2 Target behaviour determinants | If intervention is a component, what reasons for non-adherence can the technology help address? | The MATech can address different reasons for non-adherence, defined as determinants of behaviour, which can be non-modifiable or modifiable.2 19 68 Individual-level and modifiable determinants are encompassed as capability (psychological and physical), opportunity (social and physical) and motivation (reflective and automatic), also known as the COM-B model.69 | |

| D2.4.2.B.3 Behaviour change techniques | If intervention is a component, what are the ‘active ingredients’ present in the technology that may trigger change in the reasons for non-adherence targeted? | To trigger/support change in a health behaviour, interventions act by generating change in determinants of the targeted behaviour. The ‘active ingredients’ in these interventions are labelled BCTs. We included only user-level BCTs (ie, BCTs that provide support to medication users) and mapped them according to the COM-B model and across domains.70 If considered relevant, HCPs level or system-level BCT can be included in the future. | |

| D2.4.2.B.4 Intervention providers | If intervention is a component, who delivers the intervention to users? | The provider of intervention is a role played by a person, population or organisation that provides/delivers an intervention. This includes their occupational role and type of relatedness. In medication adherence, the provider is often HCP, hence the quality of the HCP-patient relationships (communication skills, collaborative decision-making, trust in the HCP, HCPs’ cultural competences) correlate with patients’ adherence.76 | |

| D2.4.2.B.5 Intervention settings | If intervention is a component, where is the service for improving adherence delivered? | Setting is the social and physical environment in which the technology is used to manage medication adherence. Implementation29 and behavioural19 science emphasise the importance of understanding and describing the environment in which a certain intervention is delivered as it can significantly influence its outcomes. In addition, not every intervention is applicable or transferable to every setting. We can distinguish between physical and virtual settings as well as the possibility of applying the intervention in any setting. | |

| D3.1 Quality indicators | How does the technology meet key quality indicators from different perspectives? | QIs are standardised, evidence-based and measurable items for monitoring and evaluating the quality of healthcare performance.80 They describe the structure, process and outcomes of care35 and based on them the standards and review criteria are developed. The target audience of the repository is very diverse and with specific individual needs related to MATech. Thus, we decided to group quality indicators according to their different purposes of use (eg, general, research, decision making, use). | |

| D3.2 Implementation outcomes and strategies | What implementation outcomes and strategies are needed and available for adopting this technology in the intended setting? | Implementation sciences provide knowledge on how to facilitate the adoption and use of technologies in real-world settings. The development of MATech often starts without considering the actual use in real-world settings, which prevents successful adoption and scaling up into clinical care.85 Three implementation outcomes were selected for ENABLE repository: acceptability; feasibility and sustainability to target early, mid and late implementation phases. In addition, eight implementation strategies were selected and adapted to present information on training users for working with MATech, availability of education materials, expertise needed to use the MATech previous implementation experiences, financial, accreditation and other legal aspects of the use. |

Each group is presented with the core question it is addressing, rationale and sources used to create labels within the group. A detailed description of all attribute groups with labels and definitions is also available in the online supplemental file 2.

BCIO, Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology; BCT, Behaviour Change Techniques; COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behaviour; HCP, Healthcare Professional; HRQoL, Health-related Quality of Life; MATech, Medication Adherence Technologies; QI, Quality Indicator; WHO DHI, WHO Classification of Digital Health Intervention.

bmjopen-2021-059674supp002.xlsx (939.9KB, xlsx)

The final proposed framework consists of three domains: (i) product and provider information (D1), (ii) medication adherence descriptors (D2) and (iii) evaluation and implementation (D3) aligning with the three elements of the Donabedian healthcare model (i) structure, (ii) process and (iii) outcomes.35 The domains branch in 13 attributes groups, which then branch further to up to four sublevels of attributes. Each attribute is described with a label and related definition.

Choice and description of the study design

We will perform an online real-time Delphi (RT-Delphi) survey to explore the level of agreement on the MATech definition and relevance, clarity and completeness of the proposed framework of attributes defining the repository structure and gain a deeper insight into stakeholders’ distinct needs and requirements. The Delphi process is a flexible iterative process to consult and/or reach consensus among a group of people on a particular topic.36 37 The key characteristics of a Delphi study are anonymity, iteration, controlled feedback and statistical description of group response.38 The RT-Delphi approach was developed by Gordon and Pease to improve efficiency of the process and shorten the time of performance.39 Since then, several online tools have been developed to facilitate the RT-Delphi design40 and literature describing the use of RT-Delphi and comparison with the traditional multiround Delphi approach is growing.23 41–44 In contrast to the traditional Delphi, the real-time approach is round-less and offers a constant iteration by providing immediate (real-time) individual and aggregated feedback. Based on new information participants can rethink and modify their answers, which could lead to reconciliation of opinions and eventually to consensus. Participants are encouraged to revisit and engage in the survey several times during the study period.39 40 42 44 In comparison with the traditional approach, the real-time approach encompasses all key Delphi features43 and is similar from all key perspectives.23 41 43 44 Furthermore, the real-time approach is particularly suitable for managing larger groups, decreases moderators’ workload, simplifies inclusion of people from different geographic locations and can be leaner in costs.23 39 44 On the other hand, the approach requires specific software, which can sometimes be rigid in terms of survey configuration and analysis, contributes to increases study costs and requires specific instructions for participants.40 44 Acknowledging the potential challenges, the advantages of the approach outweighed them and supported a decision to adopt the real-time approach for our Delphi study.

Sampling and sample size

We aim to include stakeholders from all 39 countries, participating in the COST ENABLE, covering five different backgrounds per country: (i) adherence and eHealth research (measurement, intervention development, implementation science, health economics), (ii) clinical care (specialist and primary care practitioners providing medication adherence support), (iii) patient representation (age >18 years, active representative in patient associations or healthcare facilities), (iv) policy making and (v) technology development. Hence, the targeted sample size is at least 195 panellists to be invited in the study (39 countries×5 stakeholders).

Purposive sampling will be applied to identify potential panellists. First, requests will be sent through the ENABLE Cost Action membership list to representatives of all 39 countries, requesting them to identify suitable panellists from all five backgrounds. ENABLE members will provide the SC the name, background and email for every potential panellist. Participants’ emails will be entered in the online platform (eDelphi.org—Delphi method software45), which will enable anonymity in further steps, that is, individual’s activity and or/answers will not be linked to personal data. All communication with the panellists (invitation, reminders, etc) will be performed through the platform. If more candidates from the same background and country will be suggested, we will invite all candidates to increase the likelihood of achieving the planned sample size. If the expressed interest exceeds the planned sample size, purposeful sampling will be performed to ensure variation in expertise, country and balance other characteristics (eg, years of expertise, gender). To reach simple size and variation in sample characteristics, key international organisations from the field (eg., The International Society for Medication Adherence (ESPACOMP), Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE), European Medicines Agency (EMA), European Patient Forum (EPF), etc.) will be contacted to fill any missing gaps, if needed.

Patient and public involvement

The goal of this Delphi consultation is to involve stakeholders (patient representatives among them) in decisions regarding the development of ENABLE repository and is part of the broader approach to patient and public involvement followed in the ENABLE Action. Results will be communicated to all stakeholders, and they will be listed and acknowledged among ENABLE collaborators.

Data collection

We will use an online platform, eDelphi.org (Metodix, Helsinki, Finland45) for data collection. All survey activities—distribution, reminders, communication with and between the panellists and interim analysis of the process will be performed through the tool. The survey will be conducted from 1 October 2021 to 15 January 2022 in three stages:

Pilot stage: at least 10 members of the COST ENABLE Action, specifically members of the WG2, will be asked to test the survey (including instructions for participants) and to provide feedback on face validity as well as user experience.

First stage phase: invitation of 20 purposefully selected stakeholders (aiming for variation in expertise, geographical location and gender) to create initial aggregated feedback of the RT-Delphi.

Full-scale RT-Delphi: all remaining stakeholders will be invited to participate in the study.

Stakeholders will receive an email invitation via the eDelphi platform with a personalised link to the survey. Detailed instructions describing survey aims, rules of engagement and how to use the platform will be available on the platform.

At the beginning of the survey, participants will be encouraged to think of a hypothetical situation in which they would search for MATech applicable to their own setting/role and to assess the proposed attributes from this perspective throughout the survey. First, panellists will be asked to familiarise with the proposed structure and provide general feedback on the completeness. Furthermore, they will be asked to rate agreement with and clarity of the MATech definition and relevance and clarity of each proposed attribute group on a 9-point Likert scale, where 1 represents extremely irrelevant/unclear and 9 represents extremely relevant/clear. We will use the Live 2D format,45 where each outcome represents one of the two dimensions, that is, the x-axis stands for relevance and the y-axis stands for clarity. Additionally, an open-text field will be provided for panellists to comment on completeness of each attribute group, that is, proposing additional attributes or revising definitions. We will moderate the discussion in the following ways: (i) address technical issues with the platform by responding to the comment when the issues will be solved or provide instructions how to manage the issue and (ii) outline the progress of the study and the most commented questions in bulletins send through the platform once a week. We considered these strategies to encourage panellists to participate, taking into account the length of the survey and the complexity of the concepts they are rating. Delphi survey materials (online supplemental file 3, online supplemental file 4 and online supplemental file 5), including all attributes labels and definitions as well as participant instructions (online supplemental file 6), are shown in the online supplemental materials.

bmjopen-2021-059674supp003.pdf (3.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp004.pdf (299.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp005.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp006.pdf (444KB, pdf)

For sample description purposes, participants will be requested to provide information on their expertise (profession, years of experience, relevant professional experiences) and demographic characteristics (age, gender, country of practice). This information will also be used to examine differences in participants’ ratings and comments depending on their background and location. These data will be presented in aggregated form and not linked to the individual’s activity or answers. Revisiting and rerating will be encouraged by weekly reminders.

Data collection will be stopped on reaching adequate sample size and characteristics to achieve sufficient representability and generalisability of the opinions gathered. Therefore, we propose stopping the Delphi when three criteria will be met: (i) the total response rate to the survey is ≥30% (number of participants completing the survey, of the total number of stakeholders invited)46; (ii) a minimum of 10 panellists in each stakeholder group completed the survey; (iii) a minimum of two stakeholders from at least 2/3 of the COST ENABLE countries has completed the survey. We will operationalise survey completion as providing background data and answering at least 75% of the repository structure questions.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to characterise the sample of panellists and each stakeholder subgroup regarding profession, years of experience, age, gender and country.

Several measures can be used to determine when consensus is reached, with the percentage of agreement being the most common.47 Prespecification of the consensus measure and criteria for consensus increases trustworthiness of findings.48

Level of agreement on relevance, clarity and completeness

Stakeholder agreement on the proposed definition and attributes will guide decisions on the repository structure. Therefore, we selected a set of criteria representing different levels of agreement and consequently carrying different weights in these decisions. The level of agreement on every attribute for both outcomes (eg., relevance and clarity) will be quantified using the interpercentile range adjusted for symmetry (IPRAS) analysis technique from the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM).49 First, the disagreement index (DI) will be calculated as a ratio between the interpercentile range (IPR) and IPRAS. A DI >1 (ie, IPR >IPRAS) indicates disagreement exists. IPR is calculated using the 30th–70th percentile. IPRAS for the 9-point Likert scale is calculated according to the formula presented in the RAM User Manual.49

Second, the median and DI will define different levels of agreement and steer the decisions about the repository structure. For the relevance:

items with the median of 7–9 and no disagreement will be considered as relevant and mandatory;

items with the median of 4–6 or disagreement will be considered as optional;

items with the median of 1–3 and no disagreement will be considered not relevant and candidates for exclusion.

For an even number of participants, median ratings of, for example, 6.5 or 3.5 will be assigned to the higher level.49 Stakeholders’ responses per question will be summarised using descriptive statistics.

For clarity ratings, the above criteria will be applied as (i) sufficiently clear to remain unchanged; (ii) optional changes and (iii) candidates for rephrasing.

Panellist comments in the open-text fields will be analysed qualitatively, using content analysis. Findings will be used to rephrase and improve clarity of certain attributes or to add additional attributes proposed by stakeholders.

Subgroup analysis

Following the primary analysis on the whole sample, a subgroup analysis per stakeholder group will be conducted to examine variation in opinions and potential differences among subgroups. The same agreement criteria will be applied and descriptive statistics will be stratified by stakeholder group. In addition, we will determine the reliability of ratings per question within stakeholder group by calculating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC calculation is based on the two-way random model, considering type (average measures) and definition of relationship (consistency) and is presented in Equation 1. ICC >0.70 will indicate moderate-to-good reliability.50 51

Equation 1. Calculation of the ICC expressed in %. MSR stands for mean square for rows and MSE stands for mean square for error.

Analysis of process indicators

By analysing process data from the online tool, we will describe in more detail how stakeholders’ responses evolved through iterations and how consensus or certain level of agreement has formed.25 52

Stability of response presents the consistency of responses within the study period and between respondent group stability, which is considered a necessary precondition for determining the level of agreement or if consensus was achieved.53–55 Different measures of dispersion (eg., median, IQR) and statistical approaches (eg., descriptive, inferential) can be used44 55 to measure stability, which can be calculated between rounds (traditional Delphi) or at the end of the study (RT-Delphi).41 44

We will use the coefficient of quartile variation (CQV) as a descriptive measure of response stability. CQV will be calculated over all participants (CQVtotal) and within the same stakeholder group (CQVsub) to account for expected higher variation in response between different stakeholder groups. A CQVtotal <30% and CQVsub <15% will be considered as stable response. CQV calculation is shown in Equation 2.54 56

Equation 2. Calculation of the CQV, expressed in %. Q3 stands for value of the third quartile and Q1 for first quartile.

Final repository structure

After conducting the analyses described above (planned to be finalised at the end of April 2022), results suggesting modifications to the proposed structure will be considered for adoption by the SC in a subsequent version, which will represent the final structure of the ENABLE repository implemented on the initial ENABLE repository version. Further work will be considered to address results that might suggest ongoing debates in the field about certain attribute groups or the need for more in-depth consultation and evidence generation. This work will accompany the iterative improvement of the repository during the ENABLE Action.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations and consent to publish

The study is designed to ensure participants’ anonymity and to manage personal data in line with EU regulation. Before starting the survey, every participant will provide an informed consent electronically on the study entry page. Participants will be asked to carefully read through the statement regarding the study aim and nature as well as the data handling procedures and to mark their understanding and agreement. The results will only be published in an aggregated form and no personal details will be revealed.

An ethical approval for the activities of the COST ENABLE Action, including this Delphi study, was granted by the Malaga Regional Research Ethics Committee (‘Comite de Etica de la Investigacion Provincial de Malaga’) on 29 April 2021 (online supplemental file 7). In addition, a data protection assessment was carried out by the Data Protection Officer at the University of Basel. According to this instance, the Delphi study protocol was determined as compliant regarding data protection and security (online supplemental file 8).

bmjopen-2021-059674supp007.pdf (608.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp008.pdf (517.9KB, pdf)

Future implications and challenges

The proposed scope and framework of attributes together with findings from this Delphi study will represent the first steps on the pathway to create an evidence-based, interoperable and user-friendly MATech repository. Following the Delphi consultation and integration of the repository module on the ENABLE website,57 providers of MATech (public or private) would be invited to upload information on their products via a MATech description form based on the final repository structure. The accuracy of the information would be verified by an independent review panel through a procedure yet to be established. Important challenges lay ahead, such as how to select MATech for inclusion in the repository given the broad scope of the definitions proposed, how to ensure accurate information about the technologies included, how to provide the information in other languages than English and in non-technical language accessible for all and how to maintain a representative and varied offer of technologies in the long term. Nevertheless, the ENABLE repository promises to bring together stakeholders from different backgrounds to build a common language which can have an important positive impact on medication adherence research and practice.

Dissemination

The repository will be publicly accessible for interested parties. The use of the repository will be promoted and supported by dissemination meetings, workshops and training schools. The findings of the study will be presented via publications (reports and manuscripts in open access peer-reviewed journals) and oral presentations to different stakeholders in conferences and meetings. The spirit of COST Actions is networking and dissemination of ideas; hence, the action is open for anybody who would wish to join or would like to be informed about its activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ENABLE members for their feedback on the development of the ENABLE repository and early versions of this work, and the ENABLE Core Team for leadership and coordination of ENABLE activities, of which this work is part of.

Footnotes

Collaborators: ENABLE Collaborators: Andrei Adrian Tica, Romania; Adriana Baban, Romania; Adriana E. Chis, Ireland; Alexandru Corlăteanu, Moldova; Anna Bryndis Blöndal, Iceland; Ane Erdal, Norwaay; Anne Gerd Granås, Norway; Anthony Karageorgos, Greece; Bernard Vrijens, Belgium; Bettina S. Husebø, Norway; Bjorn Wettermark, Sweden; Christos Petrou, Cyprus; Çiğdem Gamze Özkan, Turkey; Cristina Mihaela Ghiciuc, Romania; Daisy Volmer, Estonia; Dalma Erdősi, Hungary; Darinka Gjorgieva Ackova, North Macedonia; Dragana Drakul, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Dusanka Krajnovic, Serbia; Elena Kkolou, Cyprus; Elín Ingibjorg Jacobsen, Iceland; Emma Aarnio, Finland; Enkeleda Sinaj, Albania; Enrica Menditto, Italy; Elena Kkolou, Cyprus; Eric Van Ganse, France; Esra Uslu, Turkey; Fatjona Kamberi, Albania; Fedor Lehocki, Slovakia; Francisca Leiva-Fernandez, Spain; Freyja Jónsdóttir, Iceland; Fruzsina Mezei, Hungary; Gaye Hafez, Turkey; Gregor Bond, Austria; Guenka Petrova, Bulgaria; Hendrik Knoche, Denmark; Hilary Pinnock, UK; Horacio Gonzalez-Velez, Ireland; Indrė Trečiokienė, Lithuania; Ines Potočnjak, Croatia; Ingibjörg Gunnþórsdóttir, Iceland; Ioanna Chouvarda, Greece; Ioanna Tsiligianni, Greece; Isabel Leiva Gea, Spain; Isabelle Arnet, Switzerland; Ivett Jakab, Hungary; Jaime Correia de Sousa, Portugal; Jaime Espin Balbino, Spain; Janja Jazbar, Slovenia; Jesper Kjærgaard, Denmark; Jiří Vlček, Czech Republic; Joao Gregorio, Portugal; Job van Boven; The Netherlands; Jolanta Gulbinovic, Lithuania; Josip Culig, Croatia; Jovan Mihajlović, Serbia; Juris Barzdins, Latvia; Karin Svensberg, Sweden; Katarina Smilkov, North Macedonia; Katerina Mala-Ladova, Czech Republic; Katharina Blankart, Germany; Konstantin Doberer, Austria; Konstantin Tachkov, Bulgaria; Kristiina Sepp, Estonia; Laetitia Huiart, Luxembourg; Line Iden Berge, Norway; Liset van Dijk, The Netherlands; Maja Ortner Hadžiabdić, Croatia; Manon Belhassen, France; Marcia Vervloet, The Netherlands; Maria Cordina, Malta; Marie Ekenberg, Sweden; Marie Hidle Gedde, Norway; Marie McCarthy, Ireland; Marie Schneider, Switzerland; Marie Viprey, France; Marina Odalovic, Serbia; Martin Wawruch, Slovakia; Martina Bago, Croatia; Miriam Qvarnström, Sweden; Mitar Popovic, Montenegro; Mitja Kos, Slovenia; Natasa Duborija-Kovacevic, Montenegro; Noemi Bitterman, Israel; Omar S. Usmani, UK; Ott Laius, Estonia; Panagiotis Petrou, Cyprus; Paulo Félix Lamas, Spain; Paulo Moreira, Portugal; Petra Denig, The Netherlands; Przemyslaw Kardas, Poland; Quitterie Reynaud, France; Sabina De Geest, Switzerland; Seher Çakmak, Turkey; Stefan Bruno Velescu, Romania; Susanne Reventlow, Denmark; Tamás Ágh, Hungary; Valentina Marinkovic, Serbia; Valentina Orlando, Italy; Vered Shay, Israel; Vesna Vujic-Aleksic, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Vildan Mevsim, Turkey; Yasemin Cayir, Turkey; Yingqi Gu, Ireland; Zorana Kovacevic, Serbia.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the work and formation of this manuscript. The first draft was prepared by UNM, CG, JR and AD. All other members of the steering committee (PB-F, FH, MTH, CJ, FMR, DS and IT) reviewed and upgraded the first version. All steering committee members (CG, JR, PB-F, FH, MTH, CJ, FMR, DS and IT) worked on development of the scope and framework of the attribute groups, UNM and AD coordinated the work. SPG was consulted as the expert in Delphi methodology, specifically the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. The final version of the protocol was prepared by UNM and reviewed by all other authors (CG, JR, PB-F, SPG, FH, MTH, CJ, FMR, DS, IT and AD). All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by COST Action ENABLE—European Network to Advance Best practices & technoLogy on medication adherencE’, number CA19132. CG was supported by a PhD grant financed by the Action LIONS Vaincre le Cancer. The work of IT was partially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia (project no.451-03-68/2022-14/200161). AD was supported by an IDEXLYON grant (16-IDEX-0005; 2018-2021) during the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclaimer: Funders had no role in the study design, content work and preparation or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: SPG is a research team member for ExpertLens (an online platform and methodology for conducting modified-Delphi studies). SPG's spouse is a salaried employee of, and owns stock in, Eli Lilly and Company.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the 'Methods and analysis' section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

European Network to Advance Best Practices and TechnoLogy on Medication AdherencE (ENABLE):

Andrei Adrian Tica, Adriana Baban, Adriana E. Chis, Alexandru Corlăteanu, Anna Bryndis Blöndal, Ane Erdal, Anne Gerd Granås, Anthony Karageorgos, Bernard Vrijens, Bettina S. Husebø, Bjorn Wettermark, Christos Petrou, Çiğdem Gamze Özkan, Cristina Mihaela Ghiciuc, Daisy Volmer, Dalma Erdősi, Darinka Gjorgieva Ackova, Dragana Drakul, Dusanka Krajnovic, Elena Kkolou, Elín Ingibjorg Jacobsen, Emma Aarnio, Enkeleda Sinaj, Enrica Menditto, Elena Kkolou, Eric Van Ganse, Esra Uslu, Fatjona Kamberi, Fedor Lehocki, Francisca Leiva-Fernandez, Freyja Jónsdóttir, Fruzsina Mezei, Gaye Hafez, Gregor Bond, Guenka Petrova, Hendrik Knoche, Hilary Pinnock, Horacio Gonzalez-Velez, Indrė Trečiokienė, Ines Potočnjak, Ingibjörg Gunnþórsdóttir, Ioanna Chouvarda, Ioanna Tsiligianni, Isabel Leiva Gea, Isabelle Arnet, Ivett Jakab, Jaime Correia de Sousa, Jaime Espin Balbino, Janja Jazbar, Jesper Kjærgaard, Jiří Vlček, Joao Gregorio, Job van Boven, Jolanta Gulbinovic, Josip Culig, Jovan Mihajlović, Juris Barzdins, Karin Svensberg, Katarina Smilkov, Katerina Mala-Ladova, Katharina Blankart, Konstantin Doberer, Konstantin Tachkov, Kristiina Sepp, Laetitia Huiart, Line Iden Berge, Liset van Dijk, Maja Ortner Hadžiabdić, Manon Belhassen, Marcia Vervloet, Maria Cordina, Marie Ekenberg, Marie Hidle Gedde, Marie McCarthy, Marie Schneider, Marie Viprey, Marina Odalovic, Martin Wawruch, Martina Bago, Miriam Qvarnström, Mitar Popovic, Mitja Kos, Natasa Duborija-Kovacevic, Noemi Bitterman, Omar S. Usmani, Ott Laius, Panagiotis Petrou, Paulo Félix Lamas, Paulo Moreira, Petra Denig, Przemyslaw Kardas, Quitterie Reynaud, Sabina De Geest, Seher Çakmak, Stefan Bruno Velescu, Susanne Reventlow, Tamás Ágh, Valentina Marinkovic, Valentina Orlando, Vered Shay, Vesna Vujic-Aleksic, Vildan Mevsim, Yasemin Cayir, Yingqi Gu, and Zorana Kovacevic

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

An ethical approval for the activities of the COST ENABLE Action, including this Delphi study, was granted by the Malaga Regional Research Ethics Committee (“‘Comite de Etica de la Investigacion Provincial de Malaga”’) on 29th April 2021. In addition, a data protection assessment was carried out by the Data Protection Officer at the University of Basel. According to this instance, the Delphi study protocol was determined as compliant regarding data protection and security.

References

- 1. Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;73:691–705. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487–97. 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 2009;59:56–66. 10.3322/caac.20004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. MEDI-VOICE Project . A Low Cost, Environmentally Friendly, Smart Packaging Technology to Differentiate European SME Suppliers to Service the Needs of the Blind, Illiterate and Europe’s Aging Population.: MEDI-VOICE (Project No. FP6-017893, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed I, Ahmad NS, Ali S, et al. Medication adherence Apps: review and content analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e62. 10.2196/mhealth.6432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clyne W, McLachlan S. A mixed-methods study of the implementation of medication adherence policy solutions: how do European countries compare? Patient Prefer Adherence 2015;9:1505–15. 10.2147/PPA.S85408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Boven JF, Tsiligianni I, Potočnjak I, et al. European network to advance best practices and technology on medication adherence: mission statement. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:748702. 10.3389/fphar.2021.748702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costello RW, Dima AL, Ryan D, McIvor RA, et al. Effective deployment of technology-supported management of chronic respiratory conditions: a call for stakeholder engagement. Pragmat Obs Res 2017;8:119–28. 10.2147/POR.S132316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NHS Apps library, National health service, United Kingdom, 2021. Available: https://www.nhs.uk/apps-library/ [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 11. My health Apps: patient view, 2021. Available: https://myhealthapps.net/ [Accessed 01Jul 2021].

- 12. InterventieNet; Nederland. Available: https://interventienet.nl/ [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 13. GGD AppStore: GGD GHOR Nederland. Available: https://www.ggdappstore.nl/Appstore/Homepage/Sessie,Medewerker,Button [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 14. DIGA: federal Institute for drugs and medical devices, Germany. Available: https://diga.bfarm.de/de [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 15. Weisse Liste, Germany. Available: https://www.trustedhealthapps.org/de [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 16. Bansal A, Iqbal Khan J, Kaisar Alam S. Introduction to computational health informatics. 1st ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liyanage H, Krause P, De Lusignan S. Using ontologies to improve semantic interoperability in health data. J Innov Health Inform 2015;22:309–15. 10.14236/jhi.v22i2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (ICD-11): World Health organization (who, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Human Behaviour Change Project . The behaviour change intervention ontology. ontology Lookup service (OLS), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jea M. A new ontology Lookup service at EMBL-EBI. Proceedings of SWAT4LS International Conference, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO . Classification of digital health interventions v1.0 (DHI): World Health Organisation (WHO), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Norris E, Hastings J, Marques MM, et al. Why and how to engage expert stakeholders in ontology development: insights from social and behavioural sciences. J Biomed Semantics 2021;12:4. 10.1186/s13326-021-00240-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geist MR. Using the Delphi method to engage stakeholders: a comparison of two studies. Eval Program Plann 2010;33:147–54. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wright A, Norris E, Finnerty AN. Ontologies relevant to behaviour change interventions: a method for their development [version 3; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res 2020;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khodyakov D, Savitsky TD, Dalal S. Collaborative learning framework for online stakeholder engagement. Health Expect 2016;19:868–82. 10.1111/hex.12383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO definition of health technologies. In: 60th World Health Organization (WHO) Assembly. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Perleth M, Jakubowski E, Busse R. What is 'best practice' in health care? State of the art and perspectives in improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the European health care systems. Health Policy 2001;56:235–50. 10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00138-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michie S, Wood CE, Johnston M, et al. Behaviour change techniques: the development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–188. 10.3310/hta19990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019;7:64 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. WHO . International classification of Health Interventions (ICHI): World Health Organization (WHO), 2021.

- 32. SNOMED International . Snomed clinical terminology: SNOMED international. Available: https://www.snomed.org/snomed-ct/why-snomed-ct [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 33. Goetzinger C, et al. Ehealth technologies to improve medication adherence in patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. PROSPERO - International prospective register of systematic reviews 2019.

- 34. Ribaut J, et al. Development of an evaluation tool to assess and evaluate the characteristics and quality of eHealth applications: a systematic review and consensus finding: PROSPERO - International prospective register of systematic reviews 2021.

- 35. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q 2005;83:691–729. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iqbal S, Pipon-Young L. The Delphi method: a step-by-step guide. Psychologist 2009;22:598–601. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manage 2004;42:15–29. 10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rowe G, Wright G, Bolger F. Delphi: a reevaluation of research and theory. Technol Forecast Soc Change 1991;39:235–51. 10.1016/0040-1625(91)90039-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gordon T, Pease A. RT Delphi: An efficient, “round-less” almost real time Delphi method. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2006;73:321–33. 10.1016/j.techfore.2005.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aengenheyster S, Cuhls K, Gerhold L, et al. Real-Time Delphi in practice — a comparative analysis of existing software-based tools. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2017;118:15–27. 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.01.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gnatzy T, Warth J, von der Gracht H, et al. Validating an innovative real-time Delphi approach - A methodological comparison between real-time and conventional Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change 2011;78:1681–94. 10.1016/j.techfore.2011.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Quirke FA, Healy P, Bhraonáin EN, et al. Multi-Round compared to real-time Delphi for consensus in core outcome set (COS) development: a randomised trial. Trials 2021;22:142. 10.1186/s13063-021-05074-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thiebes S, Scheidt D, Schmidt-Kraepelin M. Paving the way for real-time Delphi in information systems research: a synthesis of survey instrument designs and feedback mechanisms 2018.

- 44. Varndell W, Fry M, Elliott D. Applying real-time Delphi methods: development of a pain management survey in emergency nursing. BMC Nurs 2021;20:149. 10.1186/s12912-021-00661-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. eDelphi.org . Delphi Method Software [program]: Metodix Ltd, Helsinki, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:Mr000008. 10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grant S, Booth M, Khodyakov D. Lack of preregistered analysis plans allows unacceptable data mining for and selective reporting of consensus in Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;99:96–105. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual: RAND Corporation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Koo TK, Li MY,. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 2016;15:155–63. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods 1996;1:30–46. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khodyakov D, Chen C. Nature and predictors of response changes in Modified-Delphi panels. Value Health 2020;23:1630–8. 10.1016/j.jval.2020.08.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dajani JS, Sincoff MZ, Talley WK. Stability and agreement criteria for the termination of Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change 1979;13:83–90. 10.1016/0040-1625(79)90007-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Scheibe MSM, Schofer J. Experiments in Delphi methodology. In: Linstone HA TM, ed. The Delphi method — techniques and applications: Addison-Wesley, reading, 1975: 262–87. [Google Scholar]

- 55. von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2012;79:1525–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Trevelyan EG, Robinson PN. Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? Eur J Integr Med 2015;7:423–8. 10.1016/j.eujim.2015.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. COSTt Action ENABLE 2020-2023. Available: https://enableadherence.eu/

- 58. Moreno-Conde A, Parra-Calderón CL, Sánchez-Seda S, et al. ITEMAS ontology for healthcare technology innovation. Health Res Policy Syst 2019;17:47. 10.1186/s12961-019-0453-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. WHO . International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF): World Health Organisation ((WHO). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60. UKCRC Health Research Analysis Forum UK Health Research Classification System (UKHRCS) - Health Categories; United Kingdom, 2021. Available: https://hrcsonline.net/health-categories/ [Accessed 01 Jul 2021].

- 61. National Cancer Institute Thesaurus (NCIT) . Cancer biomedical informatics grid, unified medical language system, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 62. MeSH . Medical subject Headings (mesh): US national library of medicine (NIH), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;11:CD000011. 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Guerreiro MP, Strawbridge J, Cavaco AM, et al. Development of a European competency framework for health and other professionals to support behaviour change in persons self-managing chronic disease. BMC Med Educ 2021;21:287. 10.1186/s12909-021-02720-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cross AJ, Elliott RA, Petrie K, et al. Interventions for improving medication-taking ability and adherence in older adults prescribed multiple medications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;5:CD012419. 10.1002/14651858.CD012419.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Levy H, Janke AT, Langa KM. Health literacy and the digital divide among older Americans. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:284–9. 10.1007/s11606-014-3069-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Marques MM, Carey RN, Norris E, et al. Delivering behaviour change interventions: development of a mode of delivery ontology. Wellcome Open Res 2020;5:125. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15906.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:91. 10.3389/fphar.2013.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:37. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Carey RN, Connell LE, Johnston M, et al. Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2018;384:693–707. 10.1093/abm/kay078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schenk PM, Michie S, West R, et al. Mechanism of action ontology V1: OSF 2021.

- 73. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (V1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med 2013;46:81–95. 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pearson E, Byrne-Davis L, Bull E, et al. Behavior change techniques in health professional training: developing a coding tool. Transl Behav Med 2018;78:96–102. 10.1093/tbm/iby125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Byrne-Davis L, Bull E, Hart J. Cards for change: Manchester implementation science collaboration (MCRIMPSCI), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Enriquez M, et al. Healthcare provider targeted interventions to improve medication adherence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2015;69:889–99. 10.1111/ijcp.12632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Norris E, Wright A, Hastings J. Specifying who delivers behaviour change interventions: development of an Intervention Source Ontology [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. Wellcome Open Res 2021;6:77. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16682.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kronk CA, Dexheimer JW. Development of the gender, sex, and sexual orientation ontology: evaluation and workflow. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:1110–5. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Norris E, Marques MM, Finnerty AN, et al. Development of an intervention setting ontology for behaviour change: specifying where interventions take place. Wellcome Open Res 2020;5:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15904.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. Qual Saf Health Care 2002;11:358–64. 10.1136/qhc.11.4.358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile APP rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e27. 10.2196/mhealth.3422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Eysenbach G, CONSORT-EHEALTH Group . CONSORT-EHEALTH: improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e126. 10.2196/jmir.1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. European Network for Health Technology Assesment (EUnetHTA Joint) . EUnetHTA Joint Action 2 WP. HTA Core Model ® version 3.0 (Pdf), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 84. O'Rourke B, Oortwijn W, Schuller T, et al. The new definition of health technology assessment: a milestone in international collaboration. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2020;36:187–90. 10.1017/S0266462320000215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zullig LL, Deschodt M, Liska J, et al. Moving from the trial to the real world: improving medication adherence using insights of implementation science. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2019;59:423–45. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38:65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10:21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-059674supp002.xlsx (939.9KB, xlsx)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp003.pdf (3.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp004.pdf (299.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp005.pdf (1.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp006.pdf (444KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp007.pdf (608.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-059674supp008.pdf (517.9KB, pdf)