Abstract

The emergence of multi-drug resistant pathogenic bacteria constitutes a key threat to global health. Infections caused by multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria are particularly challenging to treat due to the ability of pathogens to prevent antibiotic penetration inside the bacterial membrane. Antibiotic therapy is further rendered ineffective due to biofilm formation where the protective Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrix limits the diffusion of antibiotics inside the biofilm. We hypothesized that careful engineering of chemical groups on polymer scaffolds could enable polymers to penetrate the barriers of Gram-negative bacterial membrane and biofilm matrix. Here, we present the use of engineered polymeric nanoparticles in combination with antibiotics for synergistic antimicrobial therapy. These polymeric nanoparticles enhance the accumulation of antibiotics inside Gram-negative bacteria and biofilm matrix, resulting in increased potency of antibiotics in combination therapy. Sub-lethal concentrations of engineered polymeric nanoparticles reduce the antibiotic dosage by 32-fold to treat MDR bacteria and biofilms. Tailoring of chemical groups on polymers demonstrate a strong-structure activity relationship in generating additive and synergistic combinations with antibiotics. This study demonstrates the ability of polymeric nanoparticles to ‘rejuvenate’ antibiotics rendered ineffective by resistant bacteria and provides a rationale to design novel compounds to achieve effective antimicrobial combination therapies.

Keywords: polymers, multi-drug resistance, biofilms, combination therapy, synergistic effect

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria causes more than 2 million cases of infections and 23,000 deaths each year in US alone.[1] Worldwide annual death toll due to multi-drug resistant (MDR) bacteria increases to 700,000 and is expected to reach 10 million by the year 2050.[2] The ‘ESKAPE’ (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter species) pathogens pose the biggest threat to global health due to their multi-drug resistance.[3] In particular, infections caused by Gram-negative species of ‘ESKAPE’ pathogens show increased resistance due to an additional highly impermeable outer membrane barrier.[4] Threat posed by MDR bacteria is further aggravated by their ability to form bacterial biofilms, rendering infections refractory to both traditional antimicrobial therapies and host immune response.[5] Biofilm-associated infections can frequently occur on medical implants, indwelling devices and wounds.[6] Conventional strategies to treat these intractable infections involve high dosage treatment with last resort antibiotics such as colistin and carbapenems, increasing the risk of neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity.[7] Rigorous antibiotic therapy is often followed by surgical debridement of infected tissue, resulting in low-patient compliance and excessive healthcare costs.[8] A significant decline in the number of approved antibiotics against MDR bacteria, with no new antibiotic developed against Gram-negative bacteria in the last fifty years, has contributed to the urgency for developing novel antimicrobial therapies.[9]

Antibiotic cocktails targeting multiple pathways in pathogens have demonstrated increased antimicrobial efficacy.[10] However, this strategy is associated with increased risk of antibiotic-resistance development. Moreover, antibiotic combination therapies often fail to treat MDR Gram-negative pathogens due to limited penetration of antibiotics inside the cells.[11] Combination therapies utilizing antibiotics with membrane-sensitizing adjuvants have shown high efficacy in treating planktonic Gram-negative infections.[12] However, these small-molecule based therapies fail to treat biofilm-associated infections due to their inability to penetrate Extracellular Polymeric Substance (EPS) matrix of biofilms.[13]

Synthetic macromolecules such as nanoparticles and polymers have demonstrated ability to strongly bind and destabilize the bacterial outer membrane.[14] In addition, amphiphilic polymers exhibited excellent potential in penetrating biofilm matrix.[15] We hypothesized that combining the membrane-sensitizing and penetration-ability of polymers with the selective activity of antibiotics could offer enhanced efficacy in combating MDR bacterial and biofilm infections. Here, we report a combination therapy using engineered polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) with colistin against resistant bacterial species. We observed 16- to 32-fold decrease in the colistin dosage required to combat planktonic and biofilm bacteria in combination therapy as compared to colistin alone. The observed synergy can be attributed to enhanced bacterial membrane permeability when the antibiotic was used in combination with PNPs. We further determined that antibiotic accumulation increases about 4-fold inside the biofilms in presence of PNPs, contributing to the enhanced efficacy. Overall, this combination therapy illustrates the ability of functionalized polymers to enhance the potency of antibiotics against resistant bacterial infections, while minimizing the side-effects associated with high dosages of therapeutics.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Generation and characterization of polymeric nanoparticles

We have recently reported that distribution of cationic and hydrophobic moieties on a polymer plays a critical role in determining the antimicrobial efficacy of membrane-disrupting polymers.[15b] We have designed a library of polymers by varying the hydrophobicity of the cationic headgroups and changing the alkyl chain length bridging the headgroup with polymer backbone, to systematically probe the bacterial membrane permeability of the polymers (Figure 1a). We observed that the polymers with an 11-carbon alkyl chain bridge self-assembled to form cationic polymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) with a size ~15 nm, as shown by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in Figure 1c and SI (Figure S2). On the other hand, polymers with smaller alkyl chain (2 and 6) bridge do not self-assemble into PNPs.

Figure 1.

a) Molecular structures of oxanorbornene polymer derivatives. Log P represents the calculated hydrophobic values of each monomer. (b) Membrane permeability induced by different polymer derivatives measured as (%) uptake of N-phenyl-1-napthylamine (NPN) plotted vs overall hydrophobicity of the polymer derivatives. (c) Schematic representation showing self-assembly of polymer derivatives (n=9) into polymeric nanoparticles. Characterization of polymer nanoparticles (P7) using TEM. (d) Bar graphs demonstrating membrane disruption as a function of polymer nanoparticles with different alkyl chain length bridging polymer backbone and cationic headgroup. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of ≥ 3 replicates.

2.2. Membrane disrupting ability of polymers and combination therapy with antibiotic

Next, we screened the membrane perturbation ability of polymers (P1–P9) against Uropathogenic clinical isolate of E. coli using N-phenyl-1-napthylamine (NPN) uptake assays.[16] We observed that membrane permeation ability of the polymers increases with the increase in the overall hydrophobicity of the structure. However, increasing the length of alkyl chain bridging the polymer backbone to cationic headgroup has a stronger effect in membrane-sensitizing ability of polymers, as compared to increasing the hydrophobicity of the cationic headgroup alone (Figure 1d). A strong structure-activity relationship was observed with the most hydrophobic polymers (P6–P9) demonstrating highest membrane perturbation activity against bacteria (Figure 1b).

After establishing the membrane perturbing ability of the polymers, we tested these polymers (P4–P9) for synergistic therapy in combination with colistin antibiotics against bacteria. We evaluated the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for polymers and colistin using broth dilution methods as reported in Figure 2d.[17] Next, we performed checkerboard titrations for varied combinations of polymers and colistin and evaluated their FICI (Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index) scores. A FICI score of ≤ 0.5 is defined as a synergistic interaction, whereas an additive interaction has FICI score between 0.5 and 4.[18] Interactions are additive if the effect of the combination is approximately the independent contribution of the individual components. In contrast, synergistic interactions are when the combined effect is greater than that of the individual components administered individually.[19] Polymers (P7–P9) with higher membrane-sensitizing ability exhibited synergistic response in combination with colistin antibiotic (FICI scores ranging from 0.375 – 0.5) as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, an 8- to 16-fold reduction in colistin dosage was observed when used in combination with P7–P9 (Table S1). While polymers (P4–P6) with lesser membrane permeation ability showed additive response (0.5 < FICI < 1, SI Figure S3). We further investigated the cytotoxicity of the most potent polymers (P7–P9) by performing cytotoxicity assays on human fibroblast cell line.[15b] We determined the IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) of the cells to calculate therapeutic selectivity of polymers (ability to kill bacteria while causing minimal toxicity to mammalian cells). Least hydrophobic polymer P7 demonstrated an IC50 of ~22 μM, providing a therapeutic selectivity (IC50/MIC) of ~360. While polymer P8 and P9 demonstrated an IC50 ~ 20 and 2.5 μM, generating a therapeutic selectivity of ~160 and ~20, respectively.

Figure 2.

Checkerboard broth microdilution assays between colistin and polymer derivatives (a) P7, (b) P8 and (c) P9 against uropathogenic E. coli (CD-2). Dark cells represent higher bacterial cell density. Checkerboard data are representative of ≥2 biological replicates. (d) Table showing Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of colistin and different polymer derivatives. FIC indices were calculated using checkerboard broth microdilution assays as described in the methods section. (e) Cell viability of 3T3 fibroblast cells after treatment with PNPs. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of at ≥3 replicates.

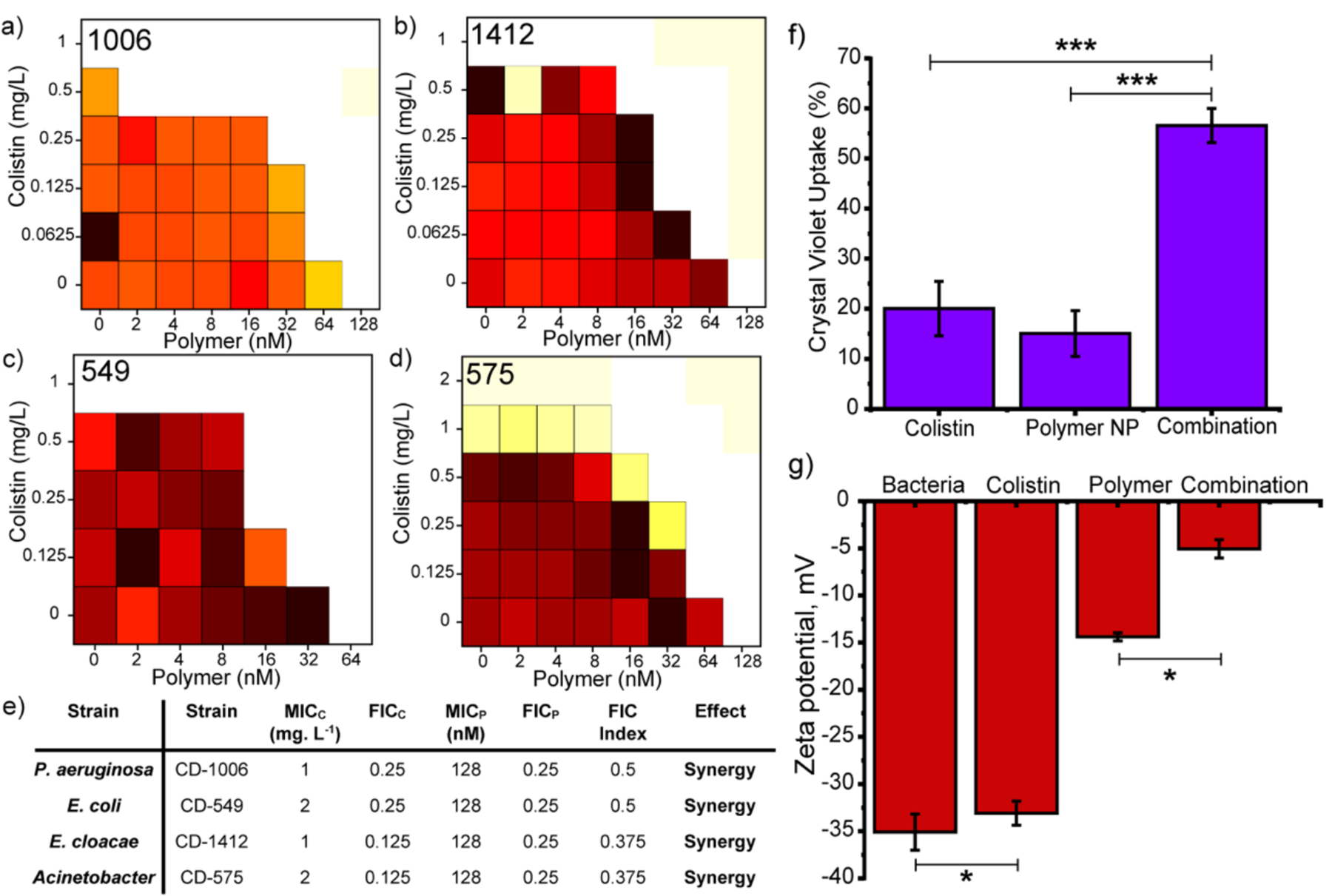

After establishing synergistic interaction between PNPs and colistin antibiotic against E. coli, we tested PNP-colistin combination against multiple uropathogenic clinical isolates to determine their broad-spectrum applicability. P7 PNPs showed synergistic effect against Gram-negative clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, E. cloacae complex, MDR E. coli and Acinetobacter species (Figure 3), yielding up to 16-fold reduction in colistin dosage to combat the resistant bacteria. Similarly, other analogues of PNPs (P8) also demonstrated synergistic response with colistin against Gram-negative strains of P. aeruginosa (SI Figure S5). On the other hand, PNP-colistin combination tested against Gram-positive strains (methicillin-resistant S. aureus, B. subtilis and S. epidermidis) exhibited additive interactions (SI Figure S7). These results indicate that using membrane-sensitizing polymeric nanoparticles can be used as a general strategy to generate synergistic antimicrobial therapy against Gram-negative MDR bacteria.

Figure 3.

Checkerboard broth microdilution assays between colistin and P7 PNPs against uropathogenic (a) P. aeruginosa (CD-1006), (b) En. cloacae complex (CD-1412), (c) MDR E. coli (CD-549), (d) Acinetobacter species (CD-575). Checkerboard data are representative of at ≥2 biological replicates. (e) Table showing MICs (Minimum Inhibitory Concentration) and FICI (Fractional Inhibitory Concentration) scores obtained for PNP-colistin combination against different strains of bacteria. Change in bacteria membrane permeability assayed by (f) crystal violet uptake and (g) zeta potential in presence of PNP, colistin and PNP-colistin combination. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation of at least threee replicates. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001.

We hypothesized that PNP-colistin combination disrupted Gram-negative bacterial membranes at sub-inhibitory dosages, owing to the strong cationic and hydrophobic nature of the PNPs.[15b] Our claims were supported by staining assays using membrane impermeable crystal violet (CV) dye where PNP-colistin combination showed increased CV accumulation inside cells as compared to PNPs and colistin alone (Figure 3f).[20] Additionally, bacterial membrane disruption was further monitored by measuring the zeta potential of bacterial surface. Bacteria treated with PNP-colistin combination (at sub-lethal dosages) showed sharp shift towards neutral charge as compared to the controls, indicating increased membrane disruption and decreased bacterial viability (Figure 3g, SI Figure S8).[20a,21]

2.3. Combination therapy for penetration and treatment of biofilms

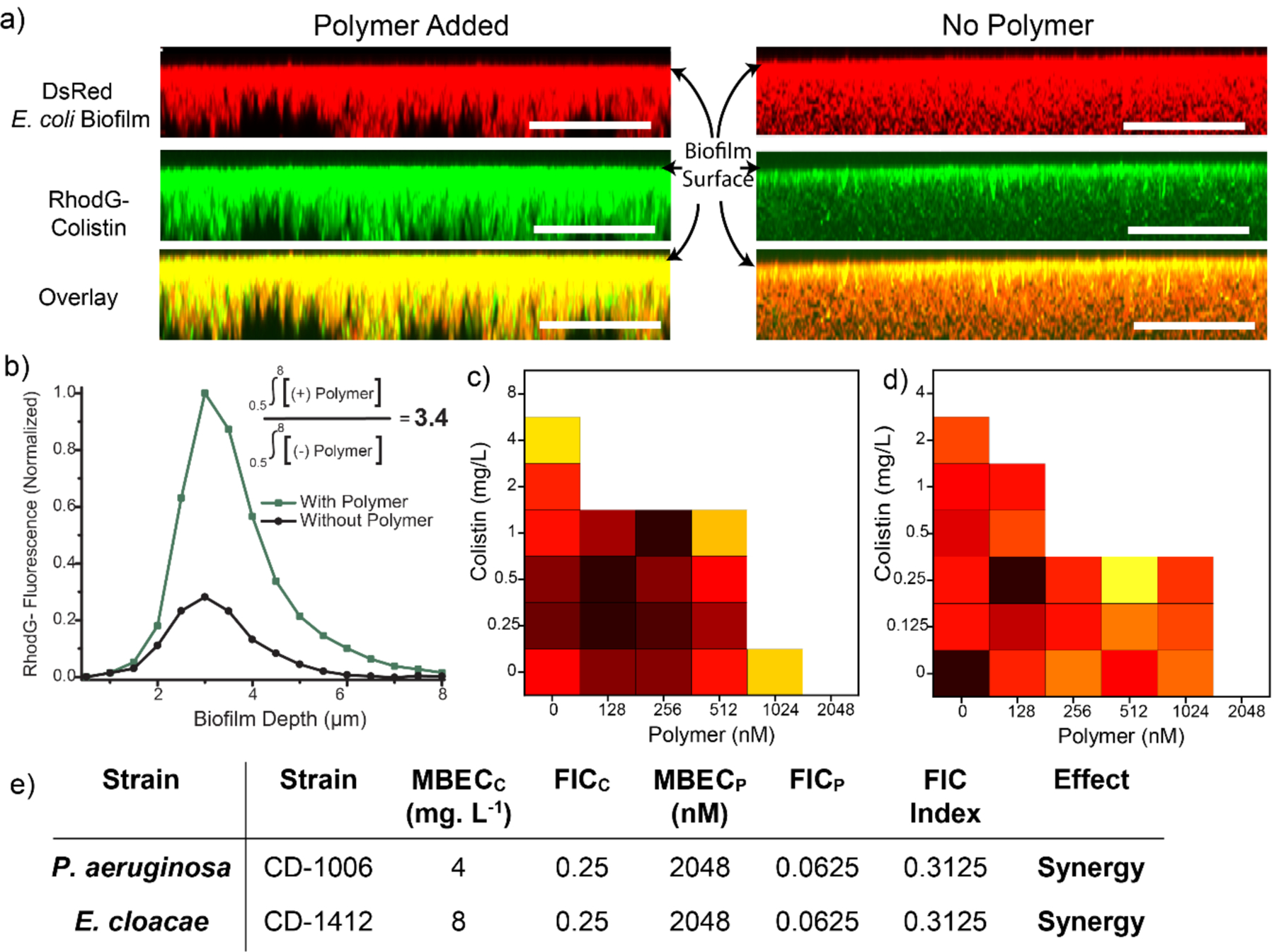

After establishing the ability of PNP-colistin combination against planktonic “superbugs”, we investigated the combination against resistant biofilms. Biofilms are three-dimensional micro-colonies of bacteria embedded inside an extra polymeric substance (EPS) matrix that prevents the penetration of antibiotics inside the biofilms.[5,6,7] Limited biofilm penetration plays a major role in rendering antibiotics ineffective against biofilm-associated infections. On the other hand, amphiphilic PNPs have shown excellent ability to penetrate biofilms. We hypothesized that using colistin in combination with PNPs would be able to enhance the penetration and accumulation of colistin inside the biofilms, thereby increasing the overall therapeutic effect of the combination therapy.[22] We treated DsRed-expressing E. coli biofilm with Rhodamine Green-tagged colistin in presence and absence of PNPs and examined using confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 4, antibiotic accumulation inside biofilms increased by ~4-fold in presence of polymers as compared to the controls. Furthermore, fluorescent-tagged colistin was homogenously distributed throughout the biofilms when used in combination with PNPs, whereas in absence of PNPs colistin was confined to the top layer of the biofilm. These results demonstrate that cationic PNPs can increase the accumulation of antibiotics inside the biofilms.

Figure 4.

(a) Representative 3D projection of confocal images stacks of DsRed (Red Fluorescent Protein) expressing E. coli DH5α biofilm after 1-hour treatment with Rhodamine Green-tagged colistin (1 mg. L−1) in presence and absence of PNP. The panels are projection at 90° angle turning along X axis. Scale bars are 20 μm. (b) Integrated intensity of Rhodamine Green and DsRed biofilm where 0 μm represents the top layer and ~8 μm the bottom layer. Checkerboard broth microdilution assays between colistin and P7 PNPs against uropathogenic biofilm (c) P. aeruginosa (CD-1006), (d) E. coli (CD-2). Checkerboard data are representative of ≥2 biological replicates. (e) Table showing MBECs (Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration) and FICI (Fractional Inhibitory Concentration) scores obtained for PNP-colistin combination against biofilms.

Next, we investigated the therapeutic efficacy of the PNP-colistin combination against biofilms. We evaluated minimum biofilm inhibition concentration (MBIC) and minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) for PNPs and colistin using broth dilution methods as reported in Figure 4.[23] We then performed checkerboard titrations using PNP-colistin combination against biofilms and evaluated the FICI (Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index) scores to evaluate the efficacy of combinations. FICI scores for PNP-colistin combinations demonstrated synergistic effect as compared to the FICI scores for the individual components, with ~32-fold decrease in colistin dosage. Similar checkerboard studies performed using colistin with other PNP analogues (P8) also showed synergistic effect against biofilms (SI Figure S10). These results further indicate that using cationic and hydrophobic PNPs can be used a general strategy to increase the accumulation of antibiotics inside the biofilms, thereby increasing their potency.

3. Conclusion

We have designed bacterial membrane-sensitizing and biofilm penetrating polymeric nanoparticles that exhibit synergistic interaction with last-resort antibiotic colistin. The bacterial membrane permeability of these polymeric nanoparticles can be regulated by incorporating hydrophobic moieties in the polymer structure. PNPs can enhance the potency of colistin up to 16-fold, owing to the increased susceptibility of bacterial membrane to the polymers. Moreover, polymeric nanoparticles enhance the accumulation of antibiotics inside the biofilms, resulting in synergistic effect of PNP-colistin combination in eradicating biofilms. PNPs render biofilms susceptible to colistin and reduce the antibiotic dosage by 32-fold as compared to antibiotic alone. Taken together, strong membrane permeability and biofilm penetration ability of PNPs make them promising candidates to enhance the efficacy of standard antibiotic therapies while circumventing the concerns associated with high antibiotic dosage. Moreover, combination therapies using PNPs have the potential to rejuvenate antibiotics that are rendered ineffective due to antibiotic-resistance.

4. Experimental Section

Membrane permeability assay using N-Phenyl-1-naphthylamine (NPN) assay:

NPN assays were performed using previously established protocols.[16] Briefly, bacteria were grown overnight in LB media at 37 °C and 275 rpm until reached stationary phase. The bacterial cells were then harvested and washed using 0.85% NaCl solution three times and then resuspended in PBS. Concentration of bacterial cells was determined by measuring the optical density at 600 nm. 100 μL (0.1 OD) bacterial solution was added to 50 μL of test materials in a black 96-well plate. After a 30-minute incubation at room temperature, 50 μL of 40 μM NPN was added followed by fluorescence measurement (excitation= 350 nm; emission=420 nm) using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2. Cells without treatment served as the negative control while 100 mg/L colistin was used as the positive control. %NPN uptake was calculated as follows:

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs):

MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent required to inhibit the growth of bacteria overnight as observed from the naked eye.[17] Bacteria cell were grown using the protocol described above. Next, bacterial solutions with concentrations of 1×106 cells/mL were prepared in M9 media. 50 μL of prepared bacteria solution were mixed with 50 μL of polymer/antibiotic prepared in M9 media in a 96-well clear plate resulting in final bacterial concentration of 5×105 cells/mL. Polymers were tested with half-fold variations in concentrations as per the standard protocols in concentration ranging from 64,000 nM – 4 nM. A sterile control group with no bacterial cells present and growth control group without addition of any polymers were carried out at the same time. The prepared 96-well plates were incubated for 16 hours. The experiments were performed in triplicates with two individual runs performed on different days.

Checkerboard titrations for combination therapy:

We performed two-dimensional checkerboard titrations using micro-dilution method to determine the synergy between antibiotics and polymers.[18] The concentration of Polymers and colistin were varied using 2-fold serial dilutions. The wells without any visual growth were considered as a combination that inhibits bacterial growth. For the colistin-polymer combinations, concentrations of the components were varied according to their MIC against the respective bacterial strains. The checkerboard titrations were performed in a set of three independent plates and repeated on different days. A schematic for a checkerboard titration plate is given in Figure S4. Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) for Colistin-polymer combination was calculated using FICs of colistin and polymer independently using the following equation:

FICI values ≤ 0.5 corresponds to synergistic combination, whereas FICI values between >0.5 and 4.0 indicates additive effect. FICI values > 4.0 respond to antagonistic effect.[18b]

Mammalian cell viability assay:

Cell viability studies performed using the previously established protocols.[13c] Briefly, 20,000 NIH 3T3 Fibroblast cells (ATCC CRL-1658) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, ATCC 30–2002) with 1% antibiotics and 10% bovine calf serum in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 48 hours. Media was replaced after 24 hours and the cells were washed (one-time) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before incubation with polymers. Polymer solution were prepared in 10%serum containing media (pre-warmed) and incubated with cells in a 96-well plate for 24 hours in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C. Alamar Blue assays were performed to assess the cell viability as per the established protocol of Invitrogen Biosource (manufacturer). Red fluorescence resulting upon the reduction of alamar blue agent was quantified using a Spectromax M5 microplate reader (Ex: 560 nm, Em: 590 nm) and used to determine cell viability. Cells incubated with no polymers were considered as 100% viable. Each experiment was performed in triplicates and repeated on two different days.

Membrane penetration using crystal violet assay:

Bacteria cells were cultured, and their concentrations were measured using the methodology reported above. Crystal violet assay were performed using the previously reported protocols.[20] Briefly, 0.1 OD bacterial solution was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution then, incubated with the test material for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Untreated cell which served as the negative control was prepared similarly without treatment. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 9300×g for 5 minutes at 4 °C followed by redispersion in PBS with 5 μg/mL crystal violet. After incubation at 37 °C for 10 minutes, the bacterial cell solution was centrifuged at 13,400×g for 15 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 80:20 ethanol: acetone and the OD of the solution was measured at 590 nm using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2. OD value from the normal untreated cell was used as blank while the OD value of crystal violet solution was considered as 100%. The percentage of crystal violet uptake was expressed as follows:

Monitoring zeta potential of bacterial membrane:

Zeta potential for bacteria membrane was monitored using previously reported protocol.[21] Briefly, bacteria were cultured and harvested as per the above-mentioned protocols. Next, 0.01 OD of bacteria cells in phosphate buffer (PB) solution (5 mM, pH=7.4) was incubated with the test materials (colistin only, polymer only and their combinations) at 37 °C for 15 minutes. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (7000×g for 5 minutes, 4 °C), then the resulting pellets were resuspended in PB. Solutions were then subjected to zeta potential measurements using Zetasizer Nano ZS. Untreated bacteria were used as the negative control.

Biofilm formation and penetration studies using confocal microscopy:

DsRed-expressing bacteria were inoculated in lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37 °C until stationary phase. The cultures were then harvested by centrifugation and washed with 0.85% sodium chloride solution three times. Concentrations of resuspended bacterial solution were determined by optical density measured at 600 nm. 108 bacterial cells/mL of DsRed (fluorescent protein) expressing E. coli, supplemented with 1 mM of IPTG ((isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside), were seeded (2 mL in M9 media) in a confocal dish and were allowed to grow.[13c] After 3 days media was replaced by a combination of 1 mg. L−1 of Rhodamine Green-Colistin and P7 PNPs (150 nM) and incubated for 1 hour. Biofilm samples incubated with only Rhodamine Green-Colistin (1 mg. L−1) were used as control. The cells were then washed with PBS three times. Confocal microscopy images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta microscope by using a 63× objective. The settings of the confocal microscope were as follows: green channel: λex=488 nm and λem=BP 505–530 nm; red channel: λex=543 nm and λem=LP 650 nm. Emission filters: BP=band pass, LP=high pass.

Determination of Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC):

MBEC is defined as the minimum concentration of an antimicrobial agent at which there is no bacteria (biofilm) growth. We used previously established protocols to determine the MBECs for the polymers and antibiotics.[23] Briefly, bacterial cells from an overnight culture were diluted to 1/5th using tryptic soy broth (TSB) and incubated at 275 rpm, 37 °C until they reach mid-log phase. 150 μL of bacteria solution was added to each row of a 96-well microtiter plate with pegged lid. Biofilms were cultured by incubating the plate for 6 hours in an incubator-shaker at 37 °C at 50 rpm. Then, the pegged lid was washed with 200 μL PBS for 30 seconds and transferred to a plate containing the test material prepared in a separate 96-well plate using M9 minimal media. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Then, the biofilms on the peg-lid were washed with PBS and transferred to a new plate containing only M9 minimal media. The plate was further incubated at 37 °C to determine the Minimum Biofilm Eradication Concentration (MBEC).

Checkerboard titration for synergy testing: Eradication of Biofilms:

Two-dimensional checkerboard titrations similar as described above were used testing synergy against biofilms. The concentration of Polymers and colistin were varied using 2-fold serial dilutions and MBEC was determined using the above-mentioned protocol.[18] The 96-well plates for the combinations were prepared using the layout described in Figure S4. The wells without any visual growth were considered as a combination that eliminates biofilm formation. For colistin-polymer combinations, concentrations of the components were varied according to their MBEC against the respective bacterial strains.

Statistical Analysis:

The data in checkerboard experiments are representative of at least two biological replicates. For all membrane permeability and fibroblast viability experiments, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation of at least three replicates. Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. A p value < 0.05 is considered as statistically significant. GraphPad Prism was used to perform statistical analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Clinical samples obtained from the Cooley Dickinson Hospital Microbiology Laboratory (Northampton, MA) were kindly provided by Dr. Margaret Riley. This research was supported by NIH Grants EB022641 and AI134770.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library. Synthesis and characterization of polymer nanoparticles and RhodamineGreen-Colistin, additional experiments for minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBECs) and checkerboard titrations.

References

- [1].Li B and Webster TJ, J. Orthop. Res, 2018, 36, 22–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Willyard C, Nature, 2017, 543, 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a). CDC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019, 63–107. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kunishima H, Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi, 2014, 102, 2839–2845. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rice LB, Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol, 2010, 31, S7–S10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].(a) Zgurskaya HI, López CA and Gnanakaran S, ACS Infect. Dis, 2016, 1, 512–522. [Google Scholar]; (b) Michael CA, Dominey-Howes D and Labbate M, Front. Public Health, 2014, 2, 145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Van Acker H, Van Dijck P and Coenye T, Trends Microbiol, 2014, 22, 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Flemming H and Wingender J, Nat. Rev. Microbiol, 2010, 8, 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lebeaux D, Chauhan A, Rendueles O and Beloin C, Pathogens, 2013, 2, 288–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].(a) Norrby SR, J. Antimicrob. Chemother, 2002, 45, 5–7. [Google Scholar]; (b) Spapen H, Jacobs R, Van Gorp V, Troubleyn J and Honoré PM, Ann. Intensive Care, 2011, 1, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Ventola CL, P&T, 2015, 40, 344–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arciola CR, Campoccia D and Montanaro L, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2018, 16, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Parsons B and Strauss E, Am. J. Surg, 2004, 188, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ventola CL, P&T, 2015, 40, 277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].(a) Tängdén T, Ups. J. Med. Sci, 2014, 119, 149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE and Maragakis LL, Clin. Microbiol. Rev, 2012, 25, 450–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Brown ED and Wright GD, Nature, 2016, 529, 336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Delcour AH, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2009, 1794, 808–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].(a) Stokes JM, French S, Ovchinnikova OG, Bouwman C, Whitfield C and Brown ED, Cell Chem. Biol, 2016, 23, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stokes JM, Macnair CR, Ilyas B, French S, Côté JP, Bouwman C, Farha MA, Sieron AO, Whitfield C, Coombes BK and Brown ED, Nat. Microbiol, 2017, 2, 17028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].(a) Tseng BS, Zhang W, Harrison JJ, Quach TP, Song JL, Penterman J, Singh PK, Chopp DL, Packman AI, Parsek MR, Environ. Microbiol, 2013, 15, 2865–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Anderl JN, Franklin MJ and Stewart PS, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother, 2000, 44, 1818–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gupta A, Das R, Yesilbag Tonga G, Mizuhara T and Rotello VM, ACS Nano, 2018, 12, 89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Gupta A, Mumtaz S, Li CH, Hussain I and Rotello VM, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2019, 48, 415–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tew GN, Scott RW, Klein ML and Degrado WF, Acc. Chem. Res, 2010, 43, 30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jain A, Duvvuri LS, Farah S, Beyth N, Domb AJ and Khan W, Adv. Healthc. Mater, 2014, 3, 1969–1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hajipour MJ, Fromm KM, Akbar Ashkarran A, Jimenez de Aberasturi D, de Larramendi IR, Rojo T, Serpooshan V, Parak WJ and Mahmoudi M, Trends Biotechnol, 2012, 30, 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ng VWL, Ke X, Lee ALZ, Hedrick JL and Yang YY, Adv. Mater, 2013, 25, 6730–6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].(a) Takahashi H, Nadres ET and Kuroda K, Biomacromolecules, 2017, 18, 257–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gupta A, Landis RF, Li CH, Schnurr M, Das R, Lee YW, Yazdani M, Liu Y, Kozlova A and Rotello VM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 12137–12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].(a) MacNair CR, Stokes JM, Carfrae LA, Fiebig-Comyn AA, Coombes BK, Mulvey MR and Brown ED, Nat. Commun, 2018, 9, 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Helander IM and Mattila-Sandholm T, J. Appl. Microbiol, 2000, 88, 213–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].(a) Wiegand I, Hilpert K and Hancock REW, Nat. Protoc, 2008, 3, 163–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li X, Robinson SM, Gupta A, Saha K, Jiang Z, Moyano DF, Sahar A, Riley MA and Rotello VM, ACS Nano, 2014, 8, 10682–10686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].(a) Odds FC, J. Antimicrob. Chemother, 2003, 52, 1–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gupta A, Saleh NM, Das R, Landis RF, Bigdeli A, Motamedchaboki K, Campos AR, Pomeroy K, Mahmoudi M and Rotello VM, Nano Futur., 2017, 1, 015004. [Google Scholar]

- [19].(a) Yilancioglu K and Cokol M, Sci. Rep, 2019, 9, 11876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang S-K, Yusoff K, Mai C-W, Lim W-M, Yap W-S, Lim S-HE and Lai K-S, Molecules, 2017, 22, 1733. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bollenbach T, Curr. Opin. Microbiol, 2015, 27, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].(a) Halder S, Yadav KK, Sarkar R, Mukherjee S, Saha P, Haldar S, Karmakar S and Sen T, Springerplus, 2015, 4, 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Plesiat P and Nikaido H, Mol. Microbiol, 1992, 6, 1323–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].(a) Bai H, Yuan H, Nie C, Wang B, Lv F, Liu L and Wang S, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed, 2015, 54, 13208–13213. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tian J, Zhang J, Yang J, Du L, Geng H and Cheng Y, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2017, 9, 18512–18520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].(a) Gupta A, Landis RF and Rotello VM, F1000Research, 2016, 5, 364. [Google Scholar]; (b) Landis RF, Li CH, Gupta A, Lee YW, Yazdani M, Ngernyuang N, Altinbasak I, Mansoor S, Khichi MAS, Sanyal A and Rotello VM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 6176–6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].(a) Ceri H, Olson ME, Stremick C, Read RR, Morck D and Buret A, J. Clin. Microbiol, 1999, 37, 1771–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Harrison JJ, Stremick CA, Turner RJ, Allan ND, Olson ME and Ceri H, Nat. Protoc, 2010, 5, 1236–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Li J, Zhang K, Ruan L, Chin SF, Wickramasinghe N, Liu H, Ravikumar V, Ren J, Duan H, Yang L and Chan-Park MB, Nano Lett., 2018, 18, 4180–4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.