Abstract

Social media has rapidly transformed the ways in which adolescents socialize and interact with the world, which has contributed to ongoing public debate about whether social media is helping or harming adolescents today. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified both the challenges of and opportunities of adolescents’ social media use, which necessitates a revisiting of the conversation around teens and social media. In this article, we discuss key aspects of adolescent social media use and socioemotional well-being, and outline how these issues may be amplified in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use this as a springboard to outline key future research directions for the field, with the goal of moving away from reductionist approaches and toward a more nuanced perspective to understand the who, what, and when of social media use and its impact on adolescent well-being. We conclude with a commentary on how psychological science can inform the translation of research to provide evidence-based recommendations for adolescent social media use.

Keywords: adolescence, social media, mental health, well-being, COVID-19 pandemic

Social media has rapidly transformed the ways in which adolescents interact with one another, sparking intense scholarly and public debate around its potential impact on teens’ socioemotional well-being and mental health. This has left many parents, educators, providers, and teens without clear guidance on how to understand and approach adolescents’ social media use. In the context of the unique challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need to address this gap in knowledge has become increasingly clear. The pandemic has fundamentally altered the way teens live their lives – online and offline. Adolescents are now turning to social media for social connection, news and information, self-expression, and academics. Many of these changes may be long-lasting; for even as physical distancing guidelines gradually subside, many teens’ and parents’ relationships with digital media may have evolved during the pandemic, and will continue to do so in the future. Thus, we argue that the field must move toward research on social media that is both nuanced and applicable. In this review, we discuss the importance of moving away from reductionist approaches that see social media as merely “helpful or harmful” and instead, consider the nuances of for whom, in what ways, and when social media use impacts adolescent well-being. Further, we must design and disseminate our research with its direct applicability to families and providers in mind, so that evidence-based recommendations for adolescents’ engagement with social media are at the forefront. More than ever before, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated physical distancing measures have revealed the necessity of changing the conversation around teens and social media use, shifting toward a more balanced understanding of risks and benefits that directly informs guidelines for parents and teens.

Thus, the current article seeks to outline the potential ways in which COVID-19 has magnified the existing challenges and opportunities of teens’ social media use, and to use this as a springboard for outlining future directions for adolescent social media research. First, we discuss key aspects of adolescent development and socioemotional well-being to provide context for a focus on social media use in this population. Second, we outline the specific ways in which COVID-19 has amplified considerations regarding the challenges and opportunities of social media use in teens, reshaping these considerations in ways that extend beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we outline recommended steps for future research on social media use and adolescent well-being so that psychological science can inform the public conversation and recommendations around teens’ social media use.

While COVID-19 may affect adolescent development and socioemotional well-being across numerous domains at the individual (e.g., cognitive, affective, behavioral) and system (e.g., peer network, family, school) levels, a full review of these changes is beyond the scope of this review (see Orben et al., 2020). Our goal is to provide necessary context for our specific focus on social media in adolescents’ lives, during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. We focus on four key domains of adolescents’ socioemotional well-being: social connection, peer influence and risky behaviors, self-presentation and self-expression, and social stressors and mental health. Notably, in this article, the terms “adolescents,” “teenagers,” and “teens” are used interchangeably to refer to youth in the period of adolescence. The developmental phenomena discussed in this article are especially relevant for the period of life when youth have begun pubertal development (Patton & Viner, 2007), but still live with parents or other caregivers (rather than on their own or with peers or romantic partners); in the U.S. and many other nations, this developmental period captures roughly ages 10–18. While our article focuses on adolescent social media use and socioemotional well-being in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we believe the core components of this review and future directions remain relevant to the periods before, amidst, and in the aftermath of COVID-19.

Setting the Stage: Adolescent Development and Socioemotional Well-being

Adolescence is a time of significant and rapid biological, social, and psychological changes, which is characterized by identity exploration, increasing autonomy from parents and reliance on peers, heightened sensation-seeking and risk-taking, and the initiation of romantic and sexual relationships (Dahl et al., 2018). Adolescence also is the developmental period in which teens are exposed to more interpersonal stress (Hamilton et al., 2015), experience more emotional intensity and dysregulation (Guyer et al., 2016), and are at heightened risk for first onset and worsening of nearly all mental health problems (Kessler et al., 2005; Patton & Viner, 2007), including depression (Hankin et al., 1998; Salk et al., 2017), anxiety (Merikangas et al., 2010), disordered eating (Holm-Denoma et al., 2014), substance use (Chen & Kandel, 1995; NIDA, 2020), and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Centers for Disease Control, 2018). These changes and vulnerabilities create a unique developmental phase of heightened risk and opportunities, for which understanding social media use and subsequent socioemotional well-being in the context of COVID-19 is particularly relevant.

One of the most prominent changes of adolescence involves how and with whom youth spend their time. In general, peer relationships take on paramount importance during adolescence, and adolescence is often referred to as a period of “social reorientation” (Nelson et al., 2005). Pubertal hormones, patterns of brain development, and social changes influence social information processing and teens become particularly sensitive to peer feedback (including both reward and rejection), status, and connection (Kilford et al., 2016; Schriber & Guyer, 2016). As youth transition from childhood to adolescence, they spend increasing amounts of unsupervised time with peers (Lam et al., 2014). Peers become extremely important for identity, self-concept, and self-worth (Harter et al., 1996). Furthermore, negative interactions, events, or sensitivities with peers (e.g., conflict, rejection, bullying, social comparison) confer heightened risk for internalizing symptoms (Hamilton et al., 2015). Adolescence also is the period in which many youth begin their first romantic relationships, with these relationships offering important opportunities for development of social skills (e.g., conflict negotiation, assertion of needs) and sexual identities (Collins, 2003; Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2015).

Yet, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted teens’ social environment and normative socioemotional developmental tasks in profound ways. For many youth around the globe, schools have been closed (Lee, 2020), extracurricular activities and milestones (e.g., graduation, dances, sporting events) have been canceled, and peer socializing has been limited for families and states who are adhering to policy recommendations and mandates. While children and adults of all ages may be experiencing feelings of loneliness during this time of physical distancing (Groarke et al., 2020), the effects of being isolated from peers may be especially pronounced for teens (Laursen & Hartl, 2013). The inability to see one’s peers in school and other in-person contexts presents a developmental mismatch that is likely to affect adolescents’ mood and overall socioemotional well-being (Orben et al., 2020). Put simply, teens are now forced to remain physically isolated with their families during the developmental period when they are biologically and psychologically driven to be with peers (Schriber & Guyer, 2016).

Adolescence also is a stage in which youth are highly attuned to peer status (e.g., the level of popularity of themselves and their peers) and peer norms (e.g., the behaviors and attitudes of peers), which makes them more susceptible to peer influence (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011). Consequently, adolescents are likely to engage in behaviors that lead to social rewards such as increased popularity or peer feedback (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011), particularly when in the presence of peers (Steinberg, 2008). Engaging in high-risk behavior is a normative part of adolescence (Steinberg, 2004), in part due to peer influence processes that provide adolescents with social rewards for risk-taking (Blakemore, 2018; Chein et al., 2011), and partially due to teens’ “personal fable” mindset: believing oneself to be uniquely invulnerable to risks (i.e., “this won’t happen to me”; Buis & Thompson, 1989). This mindset is particularly dangerous in the context of COVID-19, as it may lead to teens’ perception that COVID-19 transmission will not affect them (Ellis et al., 2020) or that symptoms may be relatively minor if infected. Further exacerbating this problem is that teens are indeed less susceptible to COVID-19 infection and account for a smaller proportion of severe cases and deaths than adults (Viner et al., 2020). This perception of invincibility, combined with lower risk of severe COVID symptoms (Viner et al., 2020), developmentally-normative social risk-taking (Blakemore, 2018), and rapidly spreading misinformation about COVID-19 on social media (Kouzy et al., 2020), could potentially lead teens to engage in behaviors that are unsafe for themselves, their families, and the general public (Andrews et al., 2020).

So how can teens cope with this new and uncertain reality of COVID-19, physical distancing, and stages of reopening? Understandably, many adolescents around the world are turning to social media to stay socially connected with their peers and the world at large, while physically distant (Common Sense Media, 2020; Ellis et al., 2020; Munasinghe et al., 2020), which highlights existing and new challenges and opportunities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical and empirical perspectives on adolescent social media use

Social media has become central to the social context of adolescence, and COVID-19 has only magnified this reality. Over the past 15 years, the advent and rapid growth of social media has transformed the ways in which adolescents interact with peers and the world around them (Shapiro & Margolin, 2014). Broadly, social media refers to digital platforms, including websites, apps, and electronic tools, that allow for users to create and share content, particularly for social networking (Carr & Hayes, 2015). These platforms may include social networking sites (e.g., Instagram, Snapchat, Tiktok), video sharing sites (e.g., Youtube), social gaming tools (e.g., Fortnite, Minecraft), and messaging apps, and may be used for a multitude of purposes, including posting photos and videos, sending individual messages, playing games, and video chatting with one or more friends. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many adolescents reported an increase in the use of digital technologies to communicate with family and friends (e.g., Common Sense Media, 2020).

Several basic features differentiate most social media from traditional, in-person interactions. Indeed, multiple theoretical frameworks have aimed to characterize social media sites, and their effects on adolescent development, based on sites’ affordances or features (Boyd, 2011; Moreno & Uhls, 2019; Nesi et al., 2018a). For example, compared to face-to-face conversations, social media tends to be more public, allowing for simultaneous interactions with many people at once. It also tends to be more “quantifiable”: the things individuals do online are often characterized by numbers of likes, followers, and views, and social media tends to involve fewer “interpersonal cues,” including tone of voice, facial expressions, and gestures.

Prior research examining the effects of social media use on adolescent well-being has often collapsed across these various sites, tools, and activities, typically estimating associations between overall “screen time” and well-being. Not surprisingly, findings have been mixed (Odgers & Jensen, 2020). While many studies have found significant, albeit small, associations between time on social media and higher levels of depression, anxiety, sleep problems, body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and health-risk behaviors (Carter et al., 2016; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Twenge & Campbell, 2018; Vannucci et al., 2020), others have found no such associations for screen time and socioemotional well-being (Cohen et al., 2017; Jensen et al., 2019; Orben & Przybylski, 2019). Still others have found the opposite effect – that social media, particularly when used to facilitate direct social interactions with friends – can have a positive effect on teens’ well-being (Clarke et al., 2018; Hamilton et al., 2020).

A consensus is now emerging that, perhaps, the sheer amount of time youth spend on social media is less important than the specific behaviors in which they engage online (Prinstein et al., 2020), yet gaps in knowledge remain. The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified these gaps, as more than ever before, the public needs clear, evidence-based guidelines for how to understand and navigate teens’ social media use. Through this review, we aim to highlight the importance of applying a more nuanced approach to understanding teen social media use and its effects on socioemotional well-being to inform the development of such guidelines.

Social Media Use and Adolescent Socioemotional Well-being in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

With the COVID-19 pandemic causing abrupt and prolonged social disruption for adolescents, many are turning to social media with increased frequency (Ellis et al., 2020; Munasinghe et al., 2020) and developing new ways of using social media to connect with their peers and the world. In many ways, COVID-19 has magnified existing challenges and opportunities of social media use for teens’ socioemotional well-being. Social media has had a profound impact on youth well-being for many years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the pandemic shedding new and urgent light on these critical issues. Furthermore, the risks and benefits of social media that have been exacerbated by the pandemic will only continue to increase in relevance in the future. Thus, in this section we outline challenges and opportunities of social media use for adolescent socioemotional well-being, highlighting the ways in which COVID-19 has amplified these concerns. We focus on domains of well-being especially relevant to the core socioemotional developmental tasks of adolescence, including establishing more intimate and complex relationships, exploring and building identity, and navigating increased autonomy from adults and reliance on peers. These four domains of socioemotional well-being include: social connection, engagement in health-risk behaviors, self-presentation and expression, and social stressors and mental health.

Social Connection

Social media is a primary mode of peer interactions and communication among adolescents (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic has further magnified the ubiquity and importance of peer interactions that occur via social media. As the COVID-19 pandemic disrupts teens’ typical social experiences, social media may offer invaluable opportunities for social connection (Orben et al., 2020), and emerging research suggestions that perceived social connection may be protective against negative mental health effects of COVID-19 (Magson et al., 2020). Adolescents may connect with peers in a variety of ways using social media, and in some ways, teens may be better equipped to maintain and explore new ways of social connection than other age groups given their status as “digital natives.” Adolescents can stay connected with their peers by video chatting, texting, commenting on posts or “stories,” social gaming, sharing videos, or sending memes for an easy way to stay in touch. Even without direct connection, social media provides teens the opportunity to stay “in the loop” of their social network by browsing peers’ Instagram feeds or passively viewing friends’ recent posts or “stories.” Although teens often connect on social media with peers in their existing social network, social restrictions and the temporary dissolution of school may present youth the opportunity to expand their networks to peers within their communities and more broadly. However, it also may promote social connection for peers with whom there is already a strong and stable connection (e.g., friends), and might weaken connections with classmates or more loosely-connected or tenuous peer relationships. This may have the unintended effect of further cementing existing social circles or hindering the development of new friendships during a developmental period that is typically characterized by friendship transitions and changes (Poulin & Chan, 2015). As youth navigate social media for their primary form of social connection, this also may broaden how they use social media and connect with peers, as well as potentially strengthen the perceived importance of in-person socializing.

Each option for connection via social media offers a range of potential benefits and drawbacks, based partially on their features or affordances (Moreno & Uhls, 2019; Nesi et al., 2018a). For example, passively browsing memes or TikTok videos may relieve boredom and provide entertainment, but, due to the lack of synchronous interaction and shared interpersonal cues, does not represent an intimate social interaction. Meeting up with a friend or romantic partner on video chat, on the other hand, may more closely resemble an in-person interaction and provide stronger social connection. Some youth, particularly younger adolescents, might feel more comfortable with text-based communication (Anderson & Jiang, 2018), due to existing social norms and the increased time and space to formulate responses. This may offer the benefit of maintaining social connection, within a safer context at certain times. Social gaming, to the extent that it does not occur in addictive or problematic ways, may also increase feelings of connection and sense of community (Sublette & Mullan, 2012). Indeed, gaming may provide opportunities to practice cooperation and prosocial skills (Granic et al., 2014), which may be especially important when such in-person opportunities are limited due to COVID-19. This may be especially true among adolescent boys, compared to girls, who are more likely to play video and online games (Anderson & Jiang, 2018).

Prior research has identified numerous benefits of technology-facilitated social connection for teens (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2020), and these benefits may be further magnified during the COVID-19 crisis. By interacting with others outside the family context, teens can practice the autonomy and independence that are essential to their development. They can share their feelings about the crisis, receive support, and distract themselves from current stressors and challenges (Cauberghe et al., 2020). Social media can connect teens to resources in their local communities or help teens feel part of a global community by participating in large-scale social media “challenges” such as those common on TikTok (Taylor, 2020) or broader social movements.

Finally, social media presents unique challenges and benefits related to adolescents’ romantic and sexual relationships. While many adults live with romantic partners or have the autonomy to remain physically in contact during the period of physical distancing, adolescents who live with their parents are likely to be separated from their romantic partners during COVID-19. Social media may provide a critical way to stay connected during this time, allowing youth to connect with partners (or to flirt with potential partners) in the ways discussed above. Research suggests that adolescents very frequently use social media to communicate with romantic and sexual partners—both general communication (Nesi et al., 2017; Rueda et al., 2015) and sexuality specifically (Widman et al., 2014)—and this communication may be even more frequent during COVID-19. However, the increased reliance on social media for connection and intimacy may add pressures to engage in sexting behaviors, which may lead to decreases in socioemotional well-being (Alonso & Romero, 2019). Importantly, it is unclear how the displacement of in-person with technology-based communication during COVID-19 may affect adolescent romantic development and intimacy. One study found that early adolescents who communicated with romantic partners primarily through technology were more likely to report poorer romantic relationship competencies one year later (Nesi et al., 2017). Given that a key developmental task of adolescence is to explore and develop one’s romantic and sexual identity, questions regarding how social media use affects relationship development will be critically important, particularly through the lens of COVID-19.

Peer Influence and Risky Behaviors

The majority of teens use social media to access news and health information (Anderson & Jiang, 2018). Yet, the degree to which this practice may be helpful and harmful for teens depends on a number of factors, including individual adolescents’ susceptibility to media and peer influence and the accuracy and source of the information. In particular, exposure to peers’ content on social media creates a context for peer influence processes. Teens’ perceptions of other teens’ behaviors can influence both risky (Blakemore, 2018) and prosocial behaviors (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2015), and this influence has been demonstrated through social media specifically (Sherman et al., 2016). On the one hand, peers sharing information on social media may encourage more prosocial motivations, which may promote health and safety behaviors during COVID-19 (Oosterhoff et al., 2020). Short, steady streams of information are readily available on most social media sites, which can enhance access to and dissemination of accurate information, and may protect teens against internalizing symptoms (Zhou et al., 2020). Indeed, many social media platforms have adopted strategies for promoting health information, such as a COVID-19 Information Center available at the top of the screen on Facebook-owned apps (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp). Some social media apps also include tips on how to prevent the spread of the disease and answers to common questions. Further, when individuals search or hashtag “covid”, social media apps feature reputable health organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO). Given the importance of peer influence in adolescence (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011), youth who share this accurate information or share personal stories with COVID-19 may promote the seriousness of the virus in one’s social network, which is more effective in promoting positive health behaviors than citing statistics (Wickman et al., 2008). Further, peers depicting safe physical distancing practices may shift the social norms in a peer group (Andrews et al., 2020), thereby making these behaviors more acceptable and reducing social influence towards engaging in risky behaviors.

COVID-19 represents an extreme example of the risks and opportunities of using social media for public health information with teens. Social media may impact teens’ perceptions of COVID-19, physical distancing, and re-opening. While teens may influence one another to engage in healthy behaviors, images and videos shared by peers who are engaging in risky behaviors (such as not practicing physical distancing) may encourage other teens to do the same. Memes or posts that make light of COVID-19 also may reduce teens’ adherence to the guidelines. This is particularly risky given that many teens report limited to no concern about their own likelihood of becoming infected with COVID-19 (Ellis et al., 2020) and that teens often overestimate their peers’ risky behavior (Prentice & Miller, 1993), which can increase teens’ likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors. Most problematic, however, is that many adolescents may be unaware that they are promoting risky behavior. The COVID-19 pandemic has been subject to an unprecedented spread of misinformation and “fake news” about COVID-19 (Kouzy et al., 2020; Zarocostas, 2020), which was recently labeled by the WHO to be an “infodemic” (United Nations Department of Communications, 2020). Many teens struggle to distinguish between “fake news” and accurate information (Breakstone et al., 2019), which may be particularly relevant if information is posted and shared by peers. False information can easily infiltrate teens’ social networks as friends share “click-bait” posts, and teens may be more likely to believe news and information if shared by a high-status peer (based on research regarding peer influence from high-status peers; Choukas-Bradley et al., 2015; Cohen & Prinstein, 2006). This problem may be further exacerbated in contexts with quickly evolving or urgent health and safety recommendations such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which may further contribute to teens’ engagement in risky behaviors.

Self-Presentation and Self-Expression

Self-presentational theories describe how individuals engage in impression management strategies to present themselves in the most positive light (Schlenker & Pontari, 2000). Teens are especially motivated to self-present in favorable ways, given the imaginary audience phenomenon, in which adolescents feel as if others are watching their every move (Zheng et al., 2019). Social media uniquely allows teens to carefully curate their self-presentation. The ability to present oneself on social media provides novel and unique outlets for many aspects of adolescent identity development, including experimentation with self-presentations and expression (Davis & Weinstein, 2017). While adolescents are not seeing their peers in school during the COVID-19 pandemic, they can still post and experiment with self-presentational photos, videos, and text. Sharing videos and ideas has become even easier with the rise of platforms like TikTok, where teens can create and post brief video clips, fostering creativity and new social identities, which may also be involved with bridging and bonding social capital to new peers or strengthening peer relationships in offline spaces (Ahn, 2012).

Social media also can facilitate the development of intellectual ideas and collective action (Middaugh et al., 2017), as teens become increasingly aware of the world and the way in which policies affect them. The social media audience also can provide adolescents with social rewards for exploring and presenting new socially-engaged identities, as well as for participating in movements for social justice (Weinstein, 2014). This is particularly relevant in the context of COVID-19 and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous, and Latinx families in the U.S., which sheds light on systemic racism contributing to these disparities (Webb Hooper et al., 2020). In this way, social media provides readily-accessible tools for teens to share developing thoughts and experiment with new social identities, particularly without access to traditional methods (e.g., school, extracurricular activities, in-person social activities). Yet, the larger context in which individuals are embedded also matters, as experimentation may negatively affect teens who are challenging the sociocultural norms of their peer networks or greater communities. Furthermore, in some cases, efforts to experiment with various forms of self-presentation online can lead adolescents toward participation in destructive movements, such as white nationalist and supremacy movements and other extremist groups (Frissen, 2021).

Importantly, teens are especially attuned to self-presentation related to physical appearance; attractiveness is often central to adolescents’ self-concept and self-worth, especially for girls (Thompson et al., 1999). Social media sites may exacerbate physical appearance concerns among adolescents due to the visualness of these media, the ability to carefully select and edit visual images, and the presence of an audience of peers who provide reinforcing feedback (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2020). Social media apps now allow for a broad range of editing techniques, including tools to change one’s body shape on photos and touch up one’s appearance in live videos. While this may allow teens to experiment with new identities and self-expression, teens also can engage in endless upward social comparison with the carefully curated and edited photos of peers, celebrities, and “influencers” (Fardouly et al., 2017). Many studies have demonstrated links between social media use – especially photo-focused behaviors – and body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating among adolescents and young adults (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016). However, certain self-presentational tactics, such as selfie sharing, likely affect youth differently depending on their motivations and peer feedback. For instance, “selfie” posting may reflect both positive self-esteem and attempts at social acceptance and reassurance-seeking (McLean et al., 2019; Rosenthal-von der Puetten et al., 2019).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when almost all interpersonal interaction with peers occurs through social media, these self-presentational concerns may be further exacerbated. With teens spending more time on social media in the absence of in-person contact with peers, they also may be spending more time on self-presentational tactics, and the “social media self” may feel even more central to one’s identity. A lack of structure or activities outside of the home, may cause adolescents to find it difficult to disengage from self-presentational tactics, since any given moment provides an opportunity for curating one’s social media presence. Indeed, teens think about the “social media audience” even when offline (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2020), which may influence teen behaviors and has implications for mental health during COVID-19. The “social media audience” may lead teens, particularly girls, to feel pressured to engage in beauty rituals even when stuck at home with their parents. Some teens may experience anxiety about limits to their typical routines for maintaining physical appearance, such as the inability to exercise or access professional services such as gyms or salons. Similarly, as youth view carefully crafted and edited images and videos of their peers, they may engage in upward social comparisons regarding physical appearance, lifestyles, and material possessions because in-person interactions cannot correct false self-presentations. In turn, youth may feel increased pressure to present a certain image of themselves to live up to those portrayed by others (Yau & Reich, 2019) and to obtain online indicators of social status, such as likes and views (Nesi & Prinstein, 2019). At the same time, however, it is possible that staying home may relieve the social or time pressures of in-person beauty or material standards for some youth, thereby having a positive impact on self-esteem and body image.

Social Stressors and Mental Health

Social media provides a novel context through which adolescents may be prone to encounter social stressors, such as peer conflict, “drama,” cyber-victimization, and harassment and discrimination, which are known to negatively impact mental health (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Fisher et al., 2016; Rose & Tynes, 2015; Tynes et al., 2019; Underwood & Ehrenreich, 2017). Even ambiguous peer responses (or lack of response) may be potentially threatening for teens, given their heightened sensitivity to peer acceptance and rejection (Nesi et al., 2018a). With more time on social media during COVID-19 (Common Sense Media, 2020; Ellis et al., 2020), the ability to escape these stressors or apply typical coping strategies may be further diminished. Given that peers’ online networks may mirror those of their offline environment, teens from disadvantaged neighborhoods may have social problems further amplified on social media (Stevens et al., 2017). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, new stressors and fears related to social media use may arise as well. Much of the content adolescents view on social media during this time may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic or the inequities that have been exposed. Content may contain references to the virus itself, photos and videos of others’ physical distancing practices or illness, updates on recent news, and descriptions of their peers’ experiences with the pandemic. Much of this content may be scary, sad, or overwhelming. As teens spend more time passively scrolling through social media to relieve boredom, they may come across a barrage of upsetting content, perhaps exacerbating anxieties, creating a sense of loneliness and helplessness, and negatively impacting mood. For instance, youth may be more likely to come across inappropriate or distressing content, depicting, for example, peers engaging in risky behaviors (Vannucci et al., 2020), visual displays of individual and systemic racism (Tynes et al., 2019), or even self-injurious behaviors (Marchant et al., 2019), which may contribute to the onset and worsening of mental health symptoms.

Given that social media provides constant access to a social space during COVID-19, teens may develop an even greater attachment and sensitivity to the status and quality of their peer relationships via social media. For some, this may contribute to a heightened sense of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), which often occurs via social media, and is associated with anxiety, loneliness, and depression (Przybylski et al., 2013; Scott & Woods, 2018). Specifically, youth may worry that, at any time, peers are engaged in rewarding social interactions on social media without them, prompting increased time online and pressure to respond to posts and messages (Nesi et al., 2018b). Without in-person interactions to provide reassurance about these relationships, teens may rely more on social media to understand their social status and strength of relationships. FoMO may be even more pronounced as parents vary in adherence and physical distancing practices, and it may be more challenging for teens whose peers are spending time together in person. Further, youth may feel pressured by peers to reply or be continuously available on social media given that there are limited options for other activities or those outside the home. Thus, while these interactions may help teens feel supported and connected to peers, social media also may become an unanticipated source of chronic and acute stressors (Steele et al., 2020). For some teens, the social threat and reward available on social media might be difficult to disengage from, or may contribute to psychological stress, particularly given adolescents’ ongoing cognitive development. Distancing practices also may prevent teens from gaining in-person social support to cope with these emerging anxieties, and teens may have fewer distractions readily available. However, for some youth, physical distancing practices and increased time at home may reduce anxieties and stressors, such that youth may now have more agency in when and how they participate in social activities.

Yet, youth are not only passive consumers of media, but actively seek and contribute to their social environments (Flynn & Rudolph, 2011), both online and offline (Subrahmanyam et al., 2006). Thus, COVID-19 and its related stressors (e.g., missing typical activities and friends; Rogers et al., 2021) may impact youth and their mental health differently (Zhou et al., 2020). Specifically, teens’ cognitive and affective states may influence social media use and teens’ online experiences, which may be exacerbated during COVID-19. For instance, COVID-19 may heighten depressogenic and anxious thoughts and behaviors, which, in turn, may impact how and when teens use social media (Drouin et al., 2020). Indeed, research indicates that teens with depression or depressive symptoms use social media in a way that further exacerbates these problems (Radovic et al., 2017), such as by excessive reassurance-seeking posting behaviors and passively browsing content. Similarly, teens’ anxious thoughts may make youth seek out, share, or be more affected by COVID-related news and information (Rogers et al., 2021), contributing to panic or general worries about what might happen or perpetuating misinformation on social media to their peer network. As teens spend more time on social media and experience more negative affective states, these youth may be more likely to seek out and react negatively to content, which may subsequently lead youth to encounter more of that content. Further, the need to rely on video tools for socialization may create new anxieties due to a lack of established social rules and comfort with these platforms, particularly for anxious teens, which will be important to explore among individuals across development. Importantly, social media may serve as a valuable tool for improving mental health, such that teens may use social media to seek out online support groups or mental health resources, including psychoeducation, screening tools, and even digital mental health interventions (Hamilton et al., 2020). This may be particularly pronounced during COVID-19, which may prompt mental health and related fields to further improve online engagement with teens for mental health prevention and early intervention (Gruber et al., 2020).

Individual Differences and Vulnerabilities for Teens’ Social Media Use during COVID-19

The use and effects of social media depend on a number of factors specific to individual teens (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity, personalities, and pre-existing emotional or mental health difficulties), as well as the broader sociocultural context of their lives. Growing research has examined gender differences in social media use and its effects on various domains of well-being and mental health (e.g., McCrae et al., 2017), and emerging research specific to COVID-19 suggests that the effects of COVID-19 on mental health may be particularly pronounced for adolescent girls, compared to boys (Magson et al., 2020; Racine et al., 2020). COVID-19 has further highlighted the importance of considering other individual factors in how social media may impact adolescents. Broadly, COVID-19 has intensified considerations involving the greater social and geopolitical context of adolescents’ lives such as families, communities, culture, laws, and policies (e.g., different rates of infection or local policies and enforcement of physical distancing during COVID-19), which may affect social media use and experiences.

Importantly, COVID-19 has not equally affected all adolescents and families, which highlights the systemic racism that has contributed to the disproportionate rates and effects of COVID-19 among racial and ethnic minorities in high-income or developed countries (Razai et al., 2021; Sze et al., 2020). Specifically, a meta-analytic review of studies from the United States and United Kingdom found that individuals of Black and Asian ethnicity are at increased risk of COVID-19 infection compared to White individuals (Sze et al., 2020). In the United States, individuals who are Black, Latinx, and Indigenous are two to four times more likely to be hospitalized due to COVID-19 than White communities (as of December 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). The personal, financial, and emotional costs of COVID-19 are likely exacerbated for adolescents who identify as a racial or ethnic minority (Novacek et al., 2020). In addition to the COVID-related stressors that may affect all teens, social media may have unique effects for youth with marginalized identities during this time. As youth are using more social media (Common Sense Media, 2020; Ellis et al., 2020), teens may be more likely to be exposed to content or videos circulating on the internet that are discriminatory or that highlight violence and systemic racism, which may be a unique form of racial trauma that impacts mental health (Saleem et al., 2020; Tynes et al., 2019). At the same time, however, social media may provide a much-needed sense of community and action, uniting youth across the world to use their voices and tools to demand change.

While social media may be beneficial for many teens, particularly during COVID-19, it may be a “lifeline” for teens who are isolated or who live in unsafe or unhealthy environments and are in need of social support. For example, teens who are immuno-compromised or have pre-existing medical conditions may be even more socially isolated and anxious about COVID-19 and re-opening practices. Social media may provide these teens with a much-needed space to connect with similar peers and provide coping resources and support for teens navigating the complex emotions of fear, grief, loss, and trauma. Further, a large body of work documents that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth are at heightened risk for mental health concerns, especially if they are rejected by their families or experience abuse (Choukas-Bradley & Thoma, In press). These concerns may be exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, when some LGBTQ teens are living in close quarters with families in high-conflict situations, and with no natural escape to school, work, or time with peers. In these challenging times, it is possible that social media offers teens an opportunity to seek social support from online communities. For example, LGBTQ adolescents may use social media to connect with friends and romantic partners, or with online-only LGBTQ support networks (Kuper & Mustanski, 2014).

Finally, it is important to note that the potential social, psychological, and financial stressors associated with COVID-19, as well as adolescents’ access to and use of social media during this time, are largely affected by families’ socioeconomic status. Adolescents from economically disadvantaged households are more likely to experience negative effects from social media (George et al., 2020), and to engage in more unstructured and unsupervised screen time (Mascheroni & Ólafsson, 2014), particularly if parents work in essential fields. At the same time, physical distancing measures may be more burdensome for families with fewer resources, who may live in smaller spaces, unsafe neighborhoods, or crowded conditions. As unemployment rates continue to soar during COVID-19, there also may be new financial hardship and stress experienced by youth during an already uncertain time. These youth may thus rely even more heavily on social media to meet basic needs for social connection and autonomy, or, alternatively, have more limited access to social media as financial constraints impact smartphone and internet services. As the economic fallout of the pandemic disproportionately affects lower income families, these disparities may be further magnified in the wake of COVID-19 and for years to come. Thus, individual and systemic factors have become exacerbated in the context of COVID-19 and warrant careful examination when examining adolescents’ social media use and socioemotional well-being.

Key Future Directions for Research

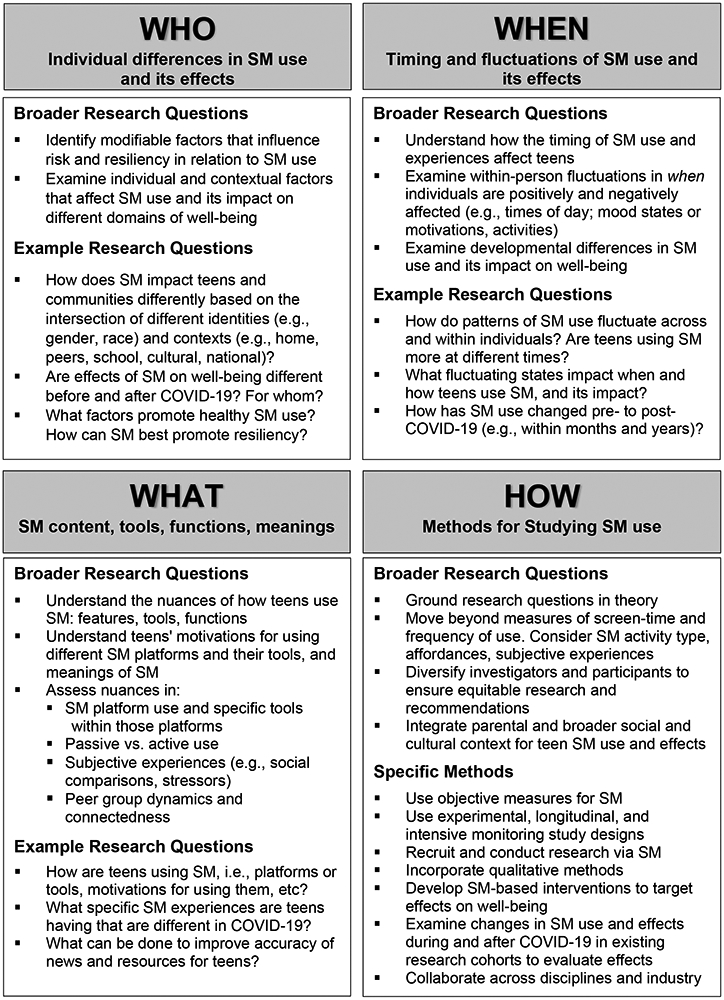

As the pandemic has reshaped teens’ daily lives, so too has it reshaped their use of social media, magnifying existing challenges and opportunities of social media use, across multiple domains of social and emotional well-being. In doing so, the pandemic has laid bare the limitations in our current understanding of how social media affects adolescent well-being. It also provides an opportunity for a renewed commitment to research that is nuanced (i.e., considers the who, what, and when of social media’s impact on teens’ socioemotional well-being), and also applicable (i.e., directly relevant to teens, families, and providers working with teens). Recent work has outlined critical future directions for research on adolescent social media use (Odgers & Jensen, 2020; Orben, 2020; Prinstein et al., 2020). Here, we build on this prior work to address the ways in which COVID-19 has elicited new research questions that inform the research agenda. We consider specific research questions related to teens’ social media use during COVID-19, and we use these as a springboard for addressing broader future directions in the field of adolescent social media use and well-being (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Key research questions for adolescent social media use in the era of COVID-19 and beyond. SM = social media.

Who: Individual differences in social media use and its effects

Media effects scholars have long recognized that media does not impact all youth in the same way, and that youth are active contributors in constructing their digital environments (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). Yet progress in the field of social media research has often been stymied by a focus on main effect models that seek to generalize the impact of digital media on all teens. Empirical work investigating the effect of COVID-19 on adolescent social media use and related well-being outcomes should seek to understand not only how teens are using social media differently in the era of COVID-19, but also which teens are using social media in certain ways. We must examine how social media use during COVID-19 impacts teens differently, as some may be especially vulnerable, or resilient, to its effects. In particular, it will be critical to consider factors of identity and context, including race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, age, socioeconomic status, health and disability, and family structure, that intersect with COVID-19 and related stressors. As a worldwide pandemic, COVID-19 may provide a context in which to evaluate the cross-cultural similarities and differences in adolescent social media use, including how the sociocultural and geopolitical forces of adolescents’ environments (e.g., messaging from public health and government officials) shape social media use and its impact on teens’ well-being. Examining the broader context of these identities and systemic inequities during COVID-19 may shed light on processes that influence how adolescents use and respond to social media. How do these factors influence a given teen’s experiences of social media use during COVID-19, and what effect does this have on their health? How does this inform the broader risk and resiliency factors and processes that impact adolescents’ social media use and well-being?

Building on these considerations, progress within the broader field of adolescent social media use requires a consideration of individual differences as both predictors of social media use and moderators of its effects. The field must seek to understand which youth are more likely to use social media in ways that can be problematic and productive, and how this influences the effects that social media has on them. Adolescents’ particular strengths and needs must be considered in light of individual and broader social-ecological differences, including individual factors (e.g., identity, strengths, vulnerability), surrounding family and peer contexts (e.g., familial rules/structure around social media, peer group dynamics, parental and peer relationships), and larger societal and cultural influences (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007; Sanders-Phillips et al., 2009). It is particularly important to identify modifiable factors that moderate or influence social media use and its effects. For instance, parents’ relationships and attitudes towards social media use and technology may have direct implications for teens’ use and experiences. An important consideration in the context of COVID-19 will be if and how parents’ and adults’ own relationships with social media have changed during this time, and its subsequent impact on teens’ use and experiences, which may provide a critical path forward for research and public health guidelines. It is important to recognize, however, that parents’ rules and guidelines for teens’ social media use may vary depending on individual characteristics of youth, such as demographic factors (e.g., age, gender) and vulnerabilities and strengths (e.g., self-regulation, coping), and that their approach may differ across adolescents in the same household. Further, research is needed to understand how and for whom efforts to change social media use (i.e., through prevention and intervention) may be most beneficial, which may also provide critical targets for selective and indicated prevention. In an effort to conduct science with its direct applicability to families in mind, we must investigate which evidence-based recommendations for teen social media use are most appropriate for whom, taking into consideration individual, family, and sociocultural factors.

What: Social media content, tools, functions, and meanings

Social media does not represent a monolithic entity, but rather a broad and diverse array of tools that can be used in a multitude of ways. It is essential to understand exactly what teens are doing on social media and why, and this may be especially important in light of new types of social media content that have arisen in relation to COVID-19 (e.g., rapid transmission of health information and misinformation, peers’ opinions related to the pandemic and associated crises) or uses of social media (e.g., more regular use of videochatting or social gaming). In this sense, COVID-19 has spurred questions relating to how teens’ use and experiences of social media have been impacted by the pandemic and its disruptions. This may include how the pandemic has affected the content to which teens are exposed, the content they are sharing, the ways they are using social media to interact with one another, how this varies within and across peer networks, and the functions that each of these behaviors serve. Further, research must closely examine these social media experiences, exploring the accuracy of information shared and consumed, and the benefits and challenges of media-based social interaction in conjunction with or in lieu of other modes of social interactions. Further, research must examine social media in the broader context of adolescents’ lives and social interactions. Each of these questions will provide valuable information about the very function and nature of teens’ social media use, and potentially in-person social interactions, which may alter the questions we ask in future research.

Although overall considerations of “screen time” are important, the field must continue building on these narrower investigations to examine in what ways teens are using social media, and why they may be engaging in specific behaviors. This must go beyond an examination of differences between platforms (i.e., TikTok versus Instagram), and must take into account what teens are doing, their motivations for doing so, and their subjective experience of these behaviors. Focusing on the affordances provided by the various platforms (Nesi et al., 2018a) also may provide a more generalizable approach for social media research moving forward, as these platforms and functions continue to grow and evolve. Thus, it is important to consider these nuances within social media rather than examining “social media” as a whole. For instance, this may mean taking into account both the researcher-defined examination of social media and allowing for variability in what teens themselves consider to be their social media. Understanding the specific types of features and functions that affect different domains of adolescent well-being, particularly using an affordance-based approach, may provide critical information to guide the development of the next wave of social media applications. The field has made progress in beginning to understand some specific social media experiences (e.g., cybervictimization, social comparison, passive versus active use), but significantly more work is needed to advance the field and improve our ability to translate this work into actionable agendas to promote adolescent health and well-being across multiple domains.

When: Timing of social media use and its effects

Understanding when adolescents are using social media and its subsequent effects involves attention to timing at the micro-level (i.e., day to day, hour to hour) and the macro-level (i.e., developmental changes). In regard to COVID-19, it is important to understand not only how much teens are using social media, but also when (at what times of day and in what mood states), as well as how this is impacted by factors that are COVID-specific (e.g., physical distancing; increasing rates of infection; re-opening practices), and more general (e.g., changes in self-regulation, distraction, environment). For instance, the use and impact of social media is likely not a static or uniform experience within a person; it is a time-varying process that fluctuates depending on teens’ internal and external contexts (Jensen et al., 2019). Thus, individual changes within and across COVID-19 may be a microcosm of an individual’s larger experience with social media. It will be important to understand how these patterns of social media use and its subsequent effects compare to pre-and post- COVID-19 usage, and how these patterns vary across the months (and potentially years) of COVID-19. For instance, will we see a change in the function and use of social media post-COVID-19, as teens grow tired of certain types of social media and strive for face-to-face interactions? Will teens develop new ways of using social media that further strengthen the closeness and connections that can be enhanced by social media? These are important questions that may shape the future of research in this area. It is also important to consider adolescents’ developmental stage, and the ways in which COVID-19 and associated stressors may impact them differently over time depending on their ongoing biological, cognitive, affective development. The degree to which this influences their use of social media and its effects is a critical area for investigation.

Generalizing these considerations to the larger research agenda on adolescent social media use, understanding timing speaks to the relevance of both within-person and between-person differences. Thus far, the majority of investigations of adolescent social media use have emphasized between-person differences, testing whether teens who use more social media, including at specific times of day (e.g., nighttime), are affected differently than those who do not. These studies remain important, and we need more research that teases apart the factors (e.g., circadian, social) that influence social media use within and across days, such as daytime and nighttime, weekend and weekday, and school and non-school days. Additionally, we must also examine within-person differences, considering for each adolescent, when they are most positively or negatively affected by certain social media experiences using intensive monitoring designs (Jensen et al., 2019; Stange et al., 2019). For example, studies might examine whether an adolescent’s fluctuations in mood impact their patterns of social media use, or whether certain types of social media use at different points during the day (e.g., before bedtime, during remote instruction) shape the impact of social media on their health and across domains of well-being (e.g., socioemotional, physical health, academics). Understanding the time-varying processes of social media use and its impact within individuals across multiple domains of well-being and functioning also may provide information to translate research into the design and development of tools for teens to better understand and alter their own use.

How: Methods for studying social media use

Beyond the substantive questions of who, what, and when adolescents are using and affected by social media, the field must take into consideration how it tests these questions. First and foremost, research examining social media use during COVID-19 and beyond should be grounded in theory to better understand the complexities of adolescent social media use and well-being. Although the field of adolescent social media research is beginning to evolve, the majority of studies have relied on cross-sectional methods and self-report measures. This has hindered researchers’ ability to make meaningful conclusions with direct applicability to the public. In regard to COVID-19, the field has not yet had time to rigorously test its effects on adolescent social media use and related psychosocial outcomes. In this paper, we have discussed potential impacts of COVID-19 on social media use and socioemotional well-being from the lens of processes and mechanisms (e.g., social interactions, developmental tasks), rather than focusing on only maladjustment or a singular outcome (e.g., anxiety, depression). This approach may serve as one example of how research can seek to understand the complex relationships of social media and one critical domain of adolescent well-being. Thus, empirically investigating the theoretical propositions outlined in this paper will be an important first step, and extended into other areas of well-being (e.g., physical health, academics). This will require a multi-method approach, drawing on qualitative and focus group work, intensive sampling methods (EMA), and longitudinal work, some of which may draw on existing (i.e., pre-COVID-19) longitudinal cohort designs. It will also require exploring the ways in which social media may act as a tool for recruitment and data collection in a world where virtual and remote designs are increasingly required.

Broadly, progress in the field of adolescent social media research requires evolving the conversation beyond reductionist characterizations of social media as “all good” or “all bad.” By continuously refocusing efforts on uncovering the nuances of what, when, and for whom social media use influences different domains of adolescent well-being, research can produce insights with direct relevance to teens, families, and providers. Methodologically, the field must move toward greater diversity of rigorous methods, including qualitative interviews and focus groups, content analyses, experimental, longitudinal, and intensive monitoring, and aim to incorporate more objective measures of use (e.g., smartphone sensing of social media usage, direct analysis of adolescents’ social media content). A bottom-up approach should be employed as well, and should be sure to include adolescents’ voices in the methods and questions we are asking. Further, the field would benefit from supplementing “screen time” measures with measures of specific social media behaviors, affordances, and teens’ subjective experiences. These approaches can be further enhanced by the use of open science frameworks and repositories that promote accessibility and transparency among research teams to continually and jointly improve the methodological approaches used in the field (e.g., validated study measures for different research designs and questions).

Finally, research designs need to increase the diversity of both investigators and participants, including the perspectives and experiences of individuals from various backgrounds, identities, and nationalities, which has implications for the equitability, generalizability and applicability of the research and ensuing recommendations. Considering the broader sociocultural and systemic contexts that shape teens’ social media experiences is important, such as the geopolitical news and policies that may directly affect social media content and teens’ experiences with it. Further, there is a need for multidisciplinary collaborations in social media research, and for active participation by industry in these endeavors, given the richness of information to which they already have access. Disciplines (e.g., psychological science, computer engineering, public health, education, medicine), policymakers, and people in industry have a unique skillset and perspective that can jointly inform this future research agenda, as well as improve the translation of research into direct recommendations and resources for the public.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

Adolescents are a unique population within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, both in terms of their developmental stage and as the “digital native” generation best equipped to use social media to stay socially-connected while physically distant. COVID-19 has magnified many of the existing considerations of social media use and its potential effects on adolescent health and well-being. In doing so, it has provided an opportunity for the field to re-evaluate current research approaches and work towards a more nuanced understanding of adolescent social media use and socioemotional well-being. We must move away from the false dichotomy of whether social media is helping or harming teens today, and instead consider the who, what, and when of social media, as well as how to rigorously examine these questions.

We conclude with a call to action for psychological science. We argue that the field should actively use our science to shape the conversation around adolescent social media use and well-being. First, psychological science around adolescent social media use should be translated into clinical and health guidelines. Second, the field must work to disseminate accessible information to the public. Finally, researchers should take an active approach towards using science to inform policies and the development of social media applications that promote adolescent well-being. While the field has come a long way in a relatively short time, COVID-19 has demonstrated that it still has a long way to go toward enacting a research agenda regarding social media use and adolescent well-being that is both more nuanced and applicable.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Jessica L. Hamilton, PhD was supported by a NIMH grants K01MH121584 and L30MH117642. Jacqueline Nesi, PhD was also supported by NIMH [K23MH122669] and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention [PDF-010517]. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIH or AFSP.

References

- Ahn J (2012). Teenagers’ experiences with social network sites: Relationships to bridging and bonding social capital. The Information Society, 28, 99–109. 10.1080/01972243.2011.649394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso C, & Romero E (2019). Sexting behaviors in adolescents: Personality predictors and psychosocial consequences in a one-year follow-up. Annals of Psychology, 35, 214–224. 10.6018/analesps.35.2.339831 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M, & Jiang J (2018). Teens, social media, and technology. Pew Research Center. pewresearch.org [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JL, Foulkes L, & Blakemore SJ (2020). Peer influence in adolescence: Public-health implications for COVID-19. Trends in Cognitive Science, 24, 585–587. 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S (2018). Avoiding social risk in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 116–122. 10.1177/0963721417738144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd D (2011). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Papacharissi Z (Ed.), Networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Breakstone J, Smith M, Wineburg S, Rapaport A, Carle J, Garland M, & Saavedra A (2019). Students’ civic online reasoning: A national portrait. https://purl.stanford.edu/gf151tb4868 [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald WA, & Prinstein MJ (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 166–179. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Morris PA (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In Damon W, Lerner RM, & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology. John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buis JM, & Thompson DN (1989). Imaginary audience and personal fable: a brief review. Adolescence, 24, 773–781. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2692409 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr CT, & Hayes RA (2015). Social media: Defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23, 46–65. 10.1080/15456870.2015.972282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B, Rees P, Hale L, Bhattacharjee D, & Paradkar MS (2016). Association between portable screen-based media device access or use and sleep outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 170, 1202–1208. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauberghe V, Van Wesenbeeck I, De Jans S, Hudders L, & Ponnet K (2020). How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 10.1089/cyber.2020.0478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2018). Injury Prevention and Control: WISQARS. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019: Racial & ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html

- Chein J, Albert D, O'Brien L, Uckert K, & Steinberg L (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain's reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14, F1–10. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, & Kandel DB (1995). The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 41–47. 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukas-Bradley S, Giletta M, Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2015). Peer influence, peer status, and prosocial behavior: An experimental investigation of peer socialization of adolescents' intentions to volunteer. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 2197–2210. 10.1007/s10964-015-0373-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukas-Bradley S, Nesi J, Widman L, & Galla BM (2020). The Appearance-Related Social Media Consciousness Scale: Development and validation with adolescents. Body Image, 33, 164–174. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choukas-Bradley S, & Thoma BC (In press). Mental health among LGBT youth. In Wong WI & VanderLaan D (Eds.), Gender and Sexuality Development: Contemporary Theory and Research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JL, Algoe SB, & Green MC (2018). Social network sites and well-being: The role of social connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 32–37. 10.1177/0963721417730833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2006). Peer contagion of aggression and health risk behavior among adolescent males: an experimental investigation of effects on public conduct and private attitudes. Child Development, 77, 967–983. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Newton-John T, & Slater A (2017). The relationship between Facebook and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Body Image, 23, 183–187. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA (2003). More than myth: the developmental significance of romantic relationships during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 1–24. 10.1111/1532-7795.1301001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Common Sense Media. (2020). SurveyMonkey Poll: How teens are coping and connecting in the time of the coronavirus. www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/pdfs/2020_surveymonkey-key-findings-toplines-teens-and-coronavirus.pdf

- Dahl RE, Allen NB, Wilbrecht L, & Suleiman AB (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554, 441–450. 10.1038/nature25770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, & Weinstein E (2017). Identity development in the digital age: An Eriksonian perspective. In Wright MF (Ed.), Identity, sexuality, and relationships among emerging adults in the digital age (pp. 1–17). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Drouin M, McDaniel BT, Pater J, & Toscos T (2020). How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23, 727–736. 10.1089/cyber.2020.0284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, & Forbes LM (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 52, 177–187. 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly J, Pinkus RT, & Vartanian LR (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women's everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31–39. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BW, Gardella JH, & Teurbe-Tolon AR (2016). Peer cybervictimization among adolescents and the associated internalizing and externalizing problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1727–1743. 10.1007/s10964-016-0541-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn M, & Rudolph KD (2011). Stress generation and adolescent depression: contribution of interpersonal stress responses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 1187–1198. 10.1007/s10802-011-9527-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frissen T (2021). Internet, the great radicalizer? Exploring relationships between seeking for online extremist materials and cognitive radicalization in young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 114. 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, Jensen MR, Russell MA, Gassman-Pines A, Copeland WE, Hoyle RH, & Odgers CL (2020). Young adolescents' digital technology use, perceived impairments, and well-being in a representative sample. Journal of Pediatrics, 219, 180–187. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Lobel A, & Engels RC (2014). The benefits of playing video games. American Psychologist, 69, 66–78. 10.1037/a0034857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groarke JM, Berry E, Graham-Wisener L, McKenna-Plumley PE, McGlinchey E, & Armour C (2020). Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLoS One, 15, e0239698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Prinstein MJ, Abramowitz JS, Albano AM, Aldao A, Borelli JL, Chung T, Clark LA, Davila J, Forbes EE, Gee DG, Hall GCN, Hallion LS, Hinshaw SP, Hofmann SG, Hollon SD, Joormann J, Kazdin AE, Klein DN, …, & Weinstock LM (2020). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. American Psychologist. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Silk JS, & Nelson EE (2016). The neurobiology of the emotional adolescent: From the inside out. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Review, 70, 74–85. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Coulter RA, & Radovic A (2020). Mental health benefits and opportunities. In Moreno MA & Hoopes AJ (Eds.), Technology and Adolescent Health: In Schools and Beyond (pp. 305–345). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Stange JP, Abramson LY, & Alloy LB (2015). Stress and the development of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression explain sex differences in depressive symptoms during adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science, 3, 702–714. 10.1177/2167702614545479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, & Angell KE (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 128–140. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9505045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Stocker C, & Robinson NS (1996). The perceived directionality of the link between approval and self-worth: The liabilities of a looking glass self-orientation among young adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Holland G, & Tiggemann M (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm-Denoma JM, Hankin BL, & Young JF (2014). Developmental trends of eating disorder symptoms and comorbid internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 15, 275–279. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, George M, Russell M, & Odgers C (2019). Young adolescents' digital technology use and mental health symptoms: Little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 1416–1433. 10.1177/2167702619859336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, & Walters EE (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilford EJ, Garrett E, & Blakemore SJ (2016). The development of social cognition in adolescence: An integrated perspective. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 106–120. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzy R, Abi Jaoude J, Kraitem A, El Alam MB, Karam B, Adib E, Zarka J, Traboulsi C, Akl EW, & Baddour K (2020). Coronavirus goes viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 misinformation epidemic on Twitter. Cureus, 12, e7255. 10.7759/cureus.7255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper LE, & Mustanski BS (2014). Using narrative analysis to identify patterns of internet influence on the identity development of same-sex attracted youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29, 499–532. 10.1177/0743558414528975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CB, McHale SM, & Crouter AC (2014). Time with peers from middle childhood to late adolescence: developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development, 85, 1677–1693. 10.1111/cdev.12235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, & Hartl AC (2013). Understanding loneliness during adolescence: developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1261–1268. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J (2020). Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4, 421. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, & Fardouly J (2020). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant A, Turner S, Balbuena L, Peters E, Williams D, Lloyd K, Lyons R, & John A (2019). Self-harm presentation across healthcare settings by sex in young people: an e-cohort study using routinely collected linked healthcare data in Wales, UK. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascheroni G, & Ólafsson K (2014). Net children go mobile: Risks and opportunities (2nd ed.). Educatt. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae N, Gettings S, & Purssell E (2017). Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 2, 315–330. 10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean SA, Jarman HK, & Rodgers RF (2019). How do "selfies" impact adolescents' well-being and body confidence? A narrative review. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12, 513–521. 10.2147/PRBM.S177834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, & Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49, 980–989. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middaugh E, Clark LS, & Ballard PJ (2017). Digital Media, participatory politics, and positive youth development. Pediatrics, 140, S127–S131. 10.1542/peds.2016-1758Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, & Uhls YT (2019). Applying an affordances approach and a developmental lens to approach adolescent social media use. Digital Health, 5, 2055207619826678. 10.1177/2055207619826678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]