Summary

K. pneumoniae sequence type 258 (Kp ST258) is a major cause of healthcare-associated pneumonia. However, it remains unclear how it causes protracted courses of infection in spite of its expression of immunostimulatory lipopolysaccharide, which should activate a brisk inflammatory response and bacterial clearance. We predicted that the metabolic stress induced in the host cells by the bacteria shapes an immune response that tolerates infection. We combined in situ metabolic imaging and transcriptional analyses to demonstrate that Kp ST258 activates host glutaminolysis and fatty acid oxidation. This response creates an oxidant-rich microenvironment conducive to the accumulation of anti-inflammatory myeloid cells. In this setting, metabolically active Kp ST258 elicits a disease-tolerant immune response. The bacteria, in turn, adapt to airway oxidants by upregulating the Type VI Secretion System, which is highly conserved across ST258 strains worldwide. Thus, much of the global success of Kp ST258 in hospital settings can be explained by the metabolic activity provoked in the host that promotes disease tolerance.

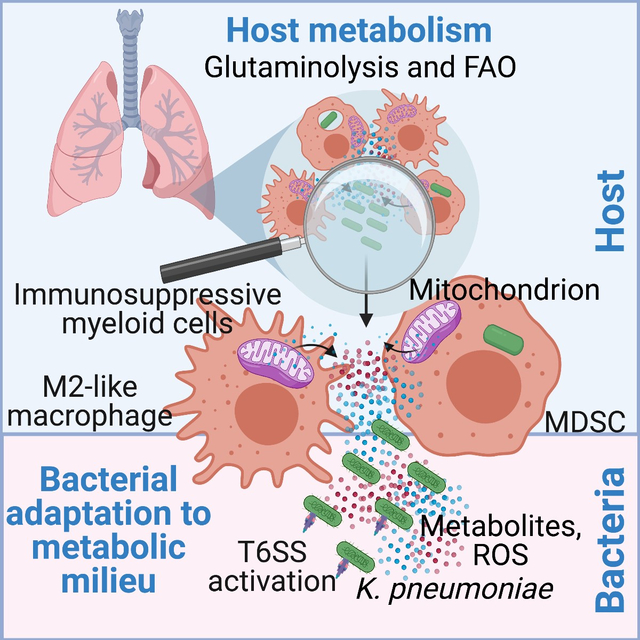

eTOC blurb:

Wong et al. reveal that the highly prevalent multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 strain induces activation of host glutaminolysis and fatty acid oxidation, oxidant-generating metabolic pathways that promote disease tolerance. The bacteria in turn adapt to the oxidant stress for survival by upregulating their Type VI Secretion System.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Kp ST258 causes healthcare-associated pneumonia worldwide (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators, 2022; Navon-Venezia et al., 2017), often complicating the course of SARS-CoV2 infection and contributing to excess morbidity and mortality (Arcari et al., 2021; Buehler et al., 2021). This Gram-negative pathogen is expected to elicit a robust lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated proinflammatory immune response, associated with efficient bacterial clearance, albeit with ancillary host damage from inflammation. Instead, Kp ST258 induces a more indolent course of infection that is nonetheless often fatal (Poe et al., 2013; Rojas et al., 2017). A major component of the immune response to Kp ST258 are monocytes that express the surface markers of the immature myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (Ahn et al., 2016; Poe et al., 2013). These cells typically arise from the local microenvironment shaped by tumors and are associated with immunosuppression and tumor progression (Marvel and Gabrilovich, 2015). We postulated that bacterial metabolism similarly impacts the nature of the host metabolic response evoked in the lung, which in turn would direct innate immune signaling and bacterial adaptation. In this study, using metabolomic analyses, we report that live Kp ST258 induces an airway metabolome distinct from that stimulated by a hypervirulent Kp strain or purified LPS. Our data reveal that this metabolic milieu promotes host immunosuppression and drives pathogen adaptation for survival via the activation of the bacterial Type VI Secretion System (T6SS), which is more renowned for its crucial role in killing non-kin competing bacteria (Jana and Salomon, 2019).

Results

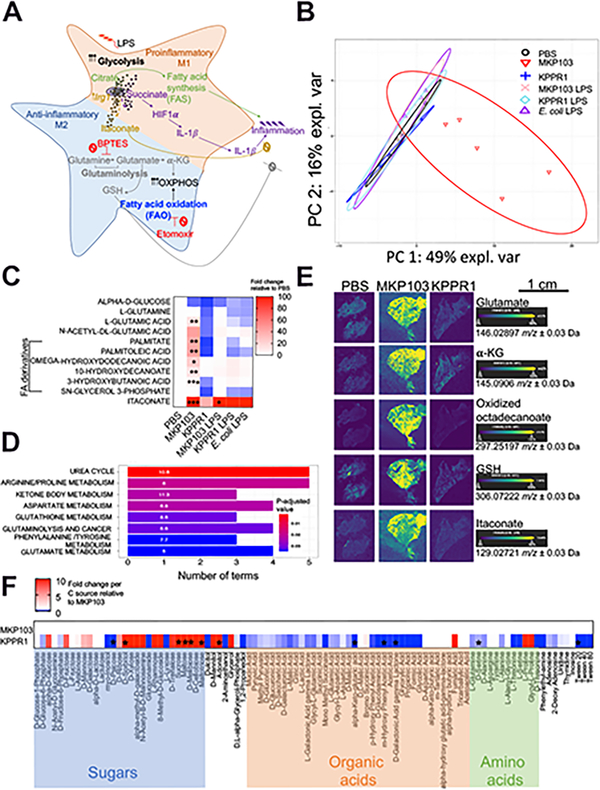

A representative Kp ST258 strain stimulates a distinct airway metabolic response compared to a hypervirulent Kp strain

We compared the metabolites in the murine airway (bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, BALF) during infection with a representative Kp ST258 isolate, MKP103 (Ramage et al., 2017) or a hypervirulent Kp strain, KPPR1 (Broberg et al., 2014), and during stimulation with purified LPS from each Kp strain or E. coli as control. The inoculum of KPPR1 was adjusted to avoid acute lethality but allow for similar burdens of Kp infection, numbers of airway immune cells, murine weight loss, and cytokine levels (Figure S1A–E). The immunometabolic response to Kp is expected to be dominated by LPS-induced proinflammatory signaling mediated by increased glycolysis, stabilization of HIF-1α and production of IL-1β (Tannahill et al., 2013) (Figure 1A). However, despite both Kp strains possessing LPS, the overall metabolome associated with MKP103 infection was entirely distinct from that elicited by KPPR1 or LPS alone (Figure 1B). The depletion of glucose and abundance of the products of glutaminolysis and fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) were notable consequences of MKP103 infection with increased L-glutamic acid and medium chain fatty acid (FA) derivatives, palmitate and decanoates (Figure 1C). Pathway enrichment analyses also revealed the activation of the urea cycle and metabolism of arginine, ketone bodies, aspartate, phenylalanine and glutathione (GSH), a major cellular antioxidant, by MKP103 infection (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Live MKP103 induces a host metabolic response distinct from that stimulated by PAMPs or KPPR1.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the metabolic activities that fuel pro- and anti-inflammatory effector functions in immune cells.

(B) Principal component analysis (PCA) score plot showing principal component 1 (PC1) versus PC2 of the metabolites extracted from the BALF of uninfected mice (PBS, n = 4 mice/biological replicates) and mice treated intranasally 48 h earlier with live MKP103 (n = 5 mice) or KPPR1 (n = 5 mice) or with purified LPS from each Kp strain and E. coli (n = 4, 4 and 6 mice respectively). The above-mentioned biological replicates were from 2 independent experiments and the data represent the median with 95% confidence interval.

(C) Heatmap showing specific BALF metabolites from (B). The level of each metabolite in response to the different stimuli is compared by fold increase over the uninfected control (PBS). Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA for each metabolite; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

(D) Pathway enrichment analysis of BALF metabolites depicting significantly upregulated pathways in MKP103-infected versus uninfected mice.

(E) DESI-MS spectral images of glutamate, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), oxidized octadecenoate (FA derivative), glutathione (GSH) and itaconate in 10 μm representative lung sections from uninfected (n = 2 mice, i.e., 1 spectral image/technical replicate of 2 biological samples from 2 experiments) and MKP103 (n = 2 mice, i.e., 1 technical replicate of 2 biological samples from 2 experiments) or KPPR1 (n = 1 mouse, i.e., 1 technical replicate of 1 biological sample)-infected mice. Scale bar (E): 1cm.

(F) Carbon source assimilation of KPPR1 relative to MKP103 (PM1 Biolog, n = 3 biological replicates from 3 independent experiments). The color intensity in the heatmap corresponds to the absorbance of KPPR1 (OD590nm) as a readout of bacterial respiration in the presence of the indicated carbon source, normalized to the absorbance (OD590nm) of MKP103 in the same carbon source. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences as determined by multiple t-test (two-stage step-up method of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, one unpaired t-test per carbon source) with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1%.

We further demonstrated marked differences in the metabolic responses to infection by the two Kp strains using desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (DESI MS) imaging of infected lungs (Figure 1E). Glutamate, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and oxidized octadecanoate were readily visualized in MKP103 but not KPPR1-infected lung tissues, consistent with energy generation through glutaminolysis and FAO, as was GSH (Figure 1E). The mitochondrial metabolite itaconate was especially prominent during live MKP103 infection (Figure 1C, E). Itaconate, the product of Irg1/Acod1, is associated with FAO-mediated ROS production (Weiss et al., 2018) and has a major role in anti-inflammatory responses (Bambouskova et al., 2018; Hooftman et al., 2020; Lampropoulou et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2019; Mills et al., 2018; Qin et al., 2019). Thus, metabolically active MKP103 induces a distinctive metabolic response characterized by increased glutaminolysis and FAO.

Differences in LPS do not account for the distinctive metabolome associated with MKP103 infection

As strain-specific modifications in LPS might influence the immunometabolic response, we analyzed the immunogenic lipid A portion of LPS from both Kp strains by MALDI-TOF MS. We identified only minor modifications (aminoarabinose and palmitate additions, Figure S1F), neither of which significantly affected the airway metabolome (Figure 1B–C) nor immunogenicity, as measured by the induction of immune cells, murine weight loss and cytokines (Figure S1B–E). Importantly, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from heat-killed (HK) MKP103 induced a similar metabolome as MKP103 LPS (Figure S1G), which was distinct from that associated with viable MKP103 (Figure 1B–C). Thus, the distinctive metabolome associated with MKP103 infection is not due to strain-specific differences in LPS.

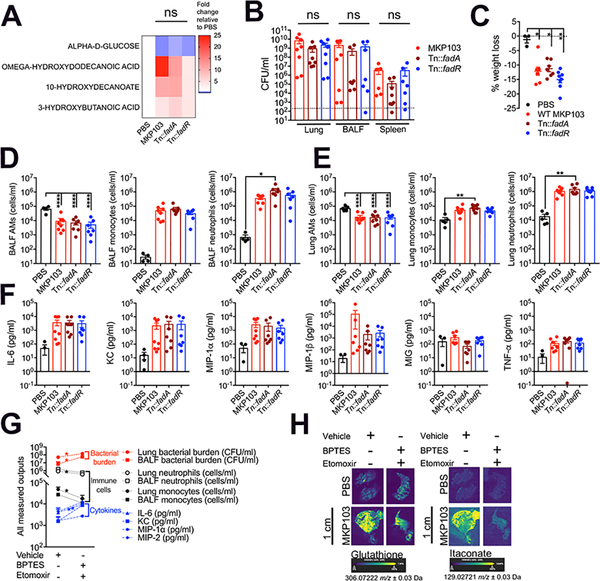

Host metabolic activities define the airway metabolome

Metabolites in the infected airway are generated by both host and pathogen. The metabolites produced by each Kp strain could account for differences in the overall airway metabolome. Alternatively, the host response during infection could be the predominant factor in shaping the metabolome. We established that MKP103 and KPPR1 have substantial differences in their substrate preferences (Figure 1F), as has been noted for the Kp ST258 strains (Ahn et al., 2021). However, we established that MKP103 mutants deficient in bacterial FA oxidation and synthesis, Tn:fadA and Tn::fadR respectively, were not associated with significantly different airway metabolomes (Figure 2A), nor were they impaired in their ability to cause infection (Figure 2B–F), indicating that bacterial metabolic activity by itself was unlikely to be the predominant source of the differences in the airway metabolome.

Figure 2. Host metabolic responses to infection predominantly dictate the airway metabolome.

(A) Heatmap showing BALF metabolites from mice treated intranasally with PBS (n = 5 mice), WT MKP103 (n = 5 mice) or transposon mutants impaired in bacterial fatty acid oxidation (Tn::fadA, n = 5 mice) and synthesis (Tn::fadR, n = 5 mice) 48 h earlier. The above-mentioned total number of mice per group were from 2 independent experiments. The level of each metabolite in response to the different stimuli is compared by fold increase over the uninfected control (PBS); ns: not significant.

(B) Bacterial burden from the lung, BALF and spleen of WT BL/6 mice infected with MKP103 (n = 8 mice), Tn::fadA (n = 8 mice) or Tn::fadR (n = 8 mice) 48 h earlier. The above-mentioned total number of mice per group were from 3 independent experiments. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection.

(C) Percentage of murine body weight loss 48 h post treatment.

(D-E) Innate immune cells (alveolar macrophages (AMs), monocytes and neutrophils) from the (D) BALF and (E) lungs of uninfected (PBS, n = 5 mice from 3 independent experiments) and infected mice (same number of replicates as in (B)) at 48 h pi.

(F) Cytokine measurements from the BALF of uninfected and infected mice at 48 h pi.

(G) Bacterial burden and host immune cells and cytokines from the airway of mice infected with MKP103 48 h earlier and treated with BPTES and etomoxir (n = 6 mice) or the vehicle control (n = 8 mice). The above-mentioned total number of mice per group were spread across 2 independent experiments.

(H) DESI-MS spectral images of GSH and itaconate in 10 μm lung sections from uninfected (n = 1 technical replicate of 1 biological sample) and MKP103-infected (n = 1 technical replicate of 1 biological sample) mice (48 h post infection, pi) treated with BPTES and etomoxir or the vehicle control. Scale bar (H): 1cm.

The data represent mean values ± SEM, statistical analysis for (A), (C-F) and (B), (G) was performed by one-way ANOVA; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001 and Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, respectively.

To establish that the host activates glutaminolysis and FAO in response to MKP103 infection, we treated mice with inhibitors of glutaminase-1 (BPTES) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1 (etomoxir), the rate-limiting enzymes for glutaminolysis and FAO, respectively, and assessed the outcomes. We confirmed the expected activities of both drugs using the Seahorse extracellular flux assay and DESI-MS (Figure S2A–B) and established that neither inhibited MKP103 growth (Figure S2C–D). The treated mice had higher bacterial loads and pro-inflammatory cytokines without significant alterations in the recruitment of airway phagocytic cells (Figure 2G, Figure S3A–B). Of note, lower induction of both glutathione and itaconate, major components of the host antioxidant response activated by MKP103 infection, was observed in the lungs of the treated mice (Figure 2H). Limiting either FAO or glutaminolysis individually did not significantly alter bacterial clearance (Figure S3C–D). Altogether, the host response to MKP103 infection predominantly defines the immunometabolic milieu in the airway.

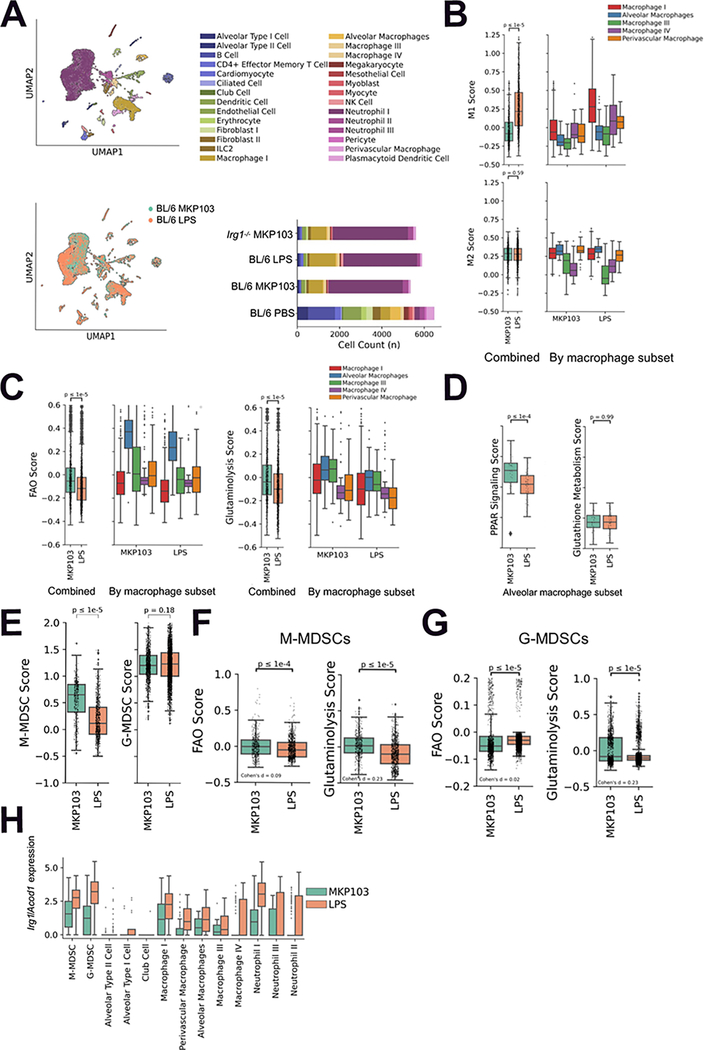

MKP103 infection recruits fewer M1-like myeloid cells and more MDSCs than LPS stimulation

The biological significance of the distinctive metabolic response to live MKP103 is its role in shaping immune responses, specifically the lack of effective bacterial clearance. Using single-cell (sc) RNA-seq, we defined immune cell populations in murine lungs (Figure 3A, Table S1–2), including the monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs) and granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs) that are interspersed with macrophages and neutrophils respectively (Sangaletti et al., 2019; Vanhaver et al., 2021; Veglia et al., 2021) (Figure S4A–D). We also determined cell counts in response to infection or LPS stimulation (Figure 3A bottom right). We observed major differences in the immune transcriptional landscape in response to live MKP103 versus its LPS alone (Figure 3A bottom left). We focused on macrophages with proinflammatory (M1) versus anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes, as defined by previously published markers (Table S2). Macrophages associated with MKP103 infection, particularly macrophage subset I, were found to have a significantly lower M1 score compared to those from LPS-stimulated mice (Figure 3B). Similar M2 scores were observed, resulting in an overall higher M2/M1 ratio during infection, consistent with the continuum between M1 and M2 phenotypes rather than a strict dichotomy. We next compared the expression of metabolic genes and found that the macrophage subsets, particularly alveolar macrophages, from MKP103 infection had significantly upregulated FAO and glutaminolysis scores (Figure 3C). Transcription of genes involved in PPAR signaling, which promotes FAO, but not glutathione metabolism, was also upregulated in alveolar macrophages during MKP103 infection (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Viable MKP103 induces both metabolic and immune changes that promote immunosuppression.

(A) UMAP embedding of cells from MKP103 and MKP103 LPS-stimulated BL/6 mice, colored by annotated cell type (top-left) and sample (bottom-left). Absolute cell counts colored by annotated cell type for all study samples (bottom-right). For each of the above conditions, n = 1 mouse.

(B) M1 (top) and M2 (bottom) macrophage scores for MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mouse macrophage populations combined (left) and stratified by sub-cluster (right).

(C) Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and glutaminolysis scores for MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mouse macrophage populations combined (left) and stratified by sub-cluster (right). (D) PPAR signaling and glutathione metabolism scores for MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mouse alveolar macrophage subset.

(E) M-MDSC and G-MDSC scores for MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mice.

(F-G) FAO and glutaminolysis scores for MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mouse (F) M-MDSC and (G) G-MDSC subpopulations.

(H) Irg1/Acod1 expression in M/G-MDSC, macrophage and neutrophil subpopulations as well as epithelial alveolar and club cells in MKP103 and LPS-stimulated BL/6 mice.

We next addressed the more complex MDSC populations. There is tremendous variability associated with these cells (Hegde et al., 2021), as well as overlap with mature granulocytes (Veglia et al., 2021). M-MDSCs were enriched during MKP103 infection compared to LPS stimulation, unlike G-MDSCs (Figure 3E). The metabolic impact of these MDSC populations in MKP103 infection included substantially upregulated glutaminolysis (Cohen’s d > 0.2) rather than FAO (Cohen’s d < 0.2 standard deviations, indicating a negligible difference despite statistical significance achieved due to high sample counts) as compared with the response to LPS alone (Figure 3F–G). We also queried the distribution of Irg1/Acod1 expression in the immune cell populations, as itaconate was a prominent component of the metabolome in response to the immune stimuli tested (Figure 1C, E). We noted its robust expression in numerous myeloid cells, especially the MDSC populations (Figure 3H). Overall, the scRNA-seq analysis provides strong evidence that specific metabolic pathways, especially glutaminolysis, FAO and the generation of itaconate, are associated with the host response to live bacterial infection.

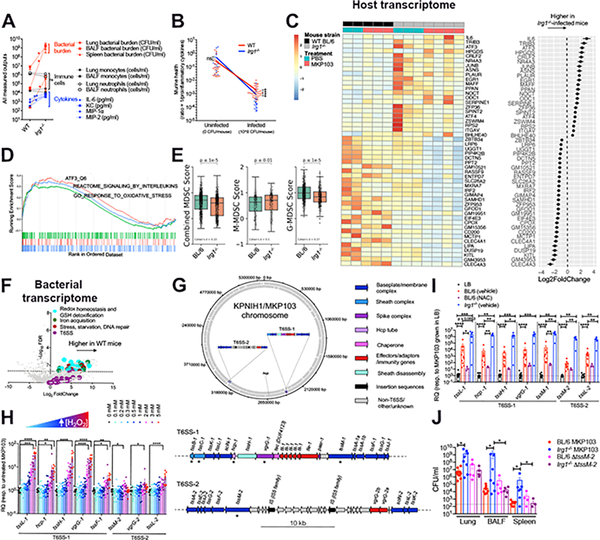

Irg1 expression directs host responses to MKP103

The abundance of itaconate in the MKP103-infected airway (Figure 1C), prompted further analysis of its role during infection. We observed significantly higher bacterial loads in the airways of Irg1−/− mice with dissemination to the spleen (Figure 4A), as well as increased cytokine induction in comparison to WT mice, despite similar overall numbers of recruited immune cells (Figure 4A, Figure S5A–C). The slope of the curve relating host health to infection state demonstrated greater disease tolerance in the WT compared to the Irg1−/−-infected mice (Figure 4B). Bulk RNA-sequencing of lung tissue from the infected-Irg1−/− mice revealed significant increases in the expression of genes associated with inflammation and stress responses, including il6, atf3/4 and their negative feedback regulator trib3 (Figure 4C), which were validated by qRT-PCR (Figure S5D). Although biological variability was noted, especially in the Irg1−/− mice (Figure 4C), enrichment analyses identified increased ATF3 (stress-induced transcription factor)-mediated signaling in the absence of Irg1, as well as positive enrichment of genes designated as responders to increased oxidative stress and inflammation (Figure 4D). In addition, in the absence of Irg1, there were decreased numbers of MDSCs, specifically G-MDSCs (Figure 4E), and increased alveolar collapse and edema (Figure S5E–F) in the lungs, consistent with increased inflammation. Taken together, these results suggest that itaconate inhibits excessive inflammation, contributing to bacterial persistence, and enables the host to tolerate this infection.

Figure 4. Itaconate dictates both host and pathogen responses during MKP103 infection.

(A) Bacterial burden and host immune cells and cytokines from the airway of WT BL/6 or Irg1−/−-infected mice (at 48 h pi), n = 10 mice and 8 mice respectively (from 3 independent experiments). Statistical analysis was performed by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

(B) Murine health (inversely proportional to proinflammatory cytokine levels) plotted against infection state. The slope of the curves indicates stronger disease tolerance in WT versus Irg1−/−-infected mice. Statistical analysis was performed by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

(C) Heatmap showing top 50 differentially expressed murine genes (Padj < 10−4, ordered by effect size) between infected WT and Irg1−/− mice (48 h pi), with each gene also normalized for basal expression in the respective uninfected mice (n = 2 uninfected and 3 infected WT BL/6 mice versus 3 uninfected and 4 infected Irg1−/− mice, 1 experiment). Biological replicates are adjacently grouped. The accompanying dot plot (right of heatmap) shows the direction and magnitude of expression change in infected Irg1−/− versus WT mice as log2-transformed fold change ± SEM.

(D) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of ranked genes from (C) against KEGG and GO gene sets involved in atf3-mediated (orange) or oxidative (green) stress responses and interleukin production (blue). The top portion plots the enrichment scores for each gene.

(E) Combined and stratified M/G-MDSC score plots for MKP103-infected BL/6 and Irg1−/−mice (n = 1 mouse per condition).

(F) Volcano plot of bacterial transcriptome displaying the pattern of gene expression values from MKP103 isolated from WT BL/6 mice (n = 3 mice, 1 experiment) at 48 h pi relative to in vitro LB culture (n = 3 biological replicates, 1 experiment). Significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR-corrected P≤ 0.05) are shown above the dotted line. Selected genes related to oxidative stress detoxification (cyan), iron acquisition (green), stress and repair (maroon) and T6SS (purple) are indicated.

(G) Schematic diagram showing the distribution of T6SS genes in the chromosome of KPNIH1, the parental strain of MKP103. The top panel shows the position and orientation of T6SS genes in the KPNIH1/MKP103 chromosome. The bottom panel shows both of these loci in detail; all T6SS-associated genes are annotated and the asterisk (*) indicates the T6SS genes of interest that were initially used to identify each of these regions. Genes are colored according to their role in T6SS. This figure was made using DNAplotter (Carver et al., 2009) in R (v3.6.0) using the R package genoplotR (v0.8.10) (Guy et al., 2010).

(H-I) Expression of T6SS genes from MKP103 (H) grown in increasing concentrations of H2O2 in LB, n = 10 biological samples per condition from 4 independent experiments or (I) harvested directly from the lungs of infected-WT BL/6 mice (48 h pi) treated (n = 10 biological samples from 3 independent experiments) or untreated with NAC (n = 3 biological samples from 1 experiment) and infected-Irg1−/− mice (n = 5 biological samples from 2 independent experiments), by qRT-PCR. RQ, relative quantification to MKP103 grown in LB only. For (H-I), columns represent mean values ± SEM, statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA for each condition; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

(J) Bacterial burden (WT MKP103 or ΔtssM-2) from the lung, BALF and spleen of WT and Irg1−/− mice (n = 9 BL/6 mice infected with WT MKP103, n = 5 BL/6 mice infected with the ΔtssM-2 mutant, n = 8 Irg1−/− mice infected with WT MKP103 and n = 5 Irg1−/− mice infected with the ΔtssM-2 mutant, 2 independent experiments), at 48 h pi, *P < 0.05 by Mann Whitney non-parametric U-test.

MKP103 upregulates the T6SS in response to oxidant stress

Just as the host upregulates Irg1 expression to counter inflammation, bacterial pathogens also adapt to the local microenvironment. Substantial differences in the expression of bacterial genes were observed in MKP103 harvested directly from the lungs of WT or Irg1−/− mice as compared with MKP103 grown in vitro (Figure S5G–H, Figure 4F). Upregulated genes included those involved in counteracting oxidative stress (GSH-mediated ROS detoxification and siderophore production) or responding to oxidant-induced DNA or protein damage (Ezraty et al., 2017; Kertesz, 2000; Li et al., 2019; Peralta et al., 2016). Increased expression of entS, fepA/D/G and fes that mediate iron sequestration via enterobactin recycling and hydrolysis was observed in the presence of oxidant stress (H2O2) in vitro (Figure S5I), consistent with the antioxidative role of enterobactin (Bogomolnaya et al., 2020; Peralta et al., 2016). These were confirmed in vivo upon treatment of mice with the anti-oxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) (Figure S5J). Of particular interest were increases in MKP103 T6SS gene expression observed in vivo versus in vitro (Figure 4F), albeit at lower false discovery rate (FDR).

The T6SS is known primarily for its function in killing bacterial competitors (Basler et al., 2013), but also senses and responds to oxidant stress in a contact-independent manner (Liaw et al., 2019; Si et al., 2017a; Si et al., 2017b; Wan et al., 2017). We identified two distinct T6SS loci (T6SS-1 and −2) in the parental strain of MKP103, KPNIH1 (Figure 4G). We observed a dose-dependent increase in T6SS gene expression in response to H2O2 in vitro (Figure 4H). We confirmed the response to oxidant stress in vivo, by demonstrating increased T6SS gene expression in bacteria harvested from murine lungs compared to liquid culture, which was significantly decreased upon treatment of the mice with NAC (Figure 4I). Upregulation of T6SS gene expression in Irg1−/− mice (Figure 4I), was also consistent with a role for the T6SS in bacterial sensing of excess oxidant stress encountered during excess inflammation.

To confirm the importance of Kp T6SS in vivo, we tested the ability of an MKP103 mutant lacking the functional activity of the T6SS, ΔtssM-2, to infect WT and Irg1−/− mice (Figure 4J). TssM (alias IcmF/VasK), encoded by genes present in both T6SS loci (Figure 4G), is a baseplate component critical for the assembly of the T6SS (Durand et al., 2012; Hsieh et al., 2018). We confirmed that tssM-1 and tssM-2 are responsive to oxidant stress in vivo (Figure 4I). The ΔtssM-2 mutant, although not impaired in its ability to infect WT mice, was significantly attenuated compared to the WT strain in the Irg1−/− mice (Figure 4J), consistent with the requirement for an intact T6SS to survive in the microenvironment of the Irg1−/− airways. Thus, MKP103 activates the expression of T6SS genes specifically in the setting of increased oxidant stress as is generated during airway infection.

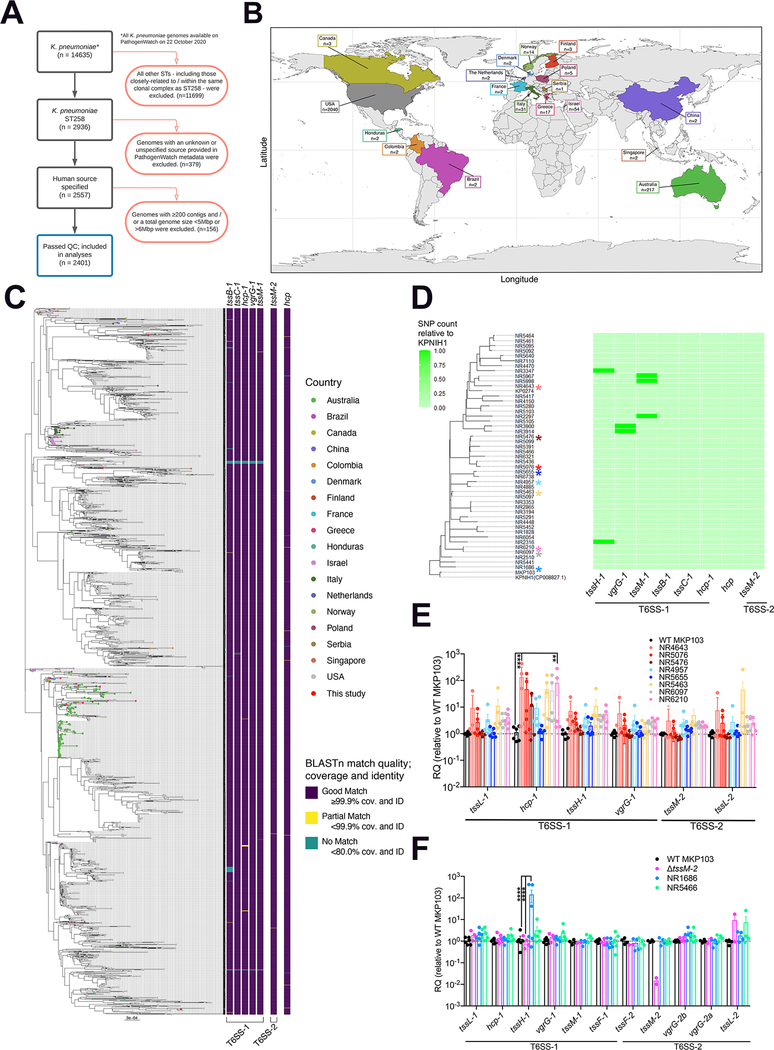

Conservation of T6SS genes including tssM-2 in Kp ST258 worldwide

While the participation of the T6SS in interbacterial competition is well established (Basler et al., 2012), this function is perhaps more critical in the gut microbiome (Sana et al., 2017), than in the much less densely colonized lung, where multiple species of resident Gram-negative commensals are infrequent. To better understand the importance of the T6SS in the overall pathogenesis of Kp ST258 infection, we investigated the conservation of T6SS genes across publicly available and geographically diverse Kp ST258 isolates (Figure 5A–C), appreciating that genome databases are frequently skewed towards strains associated with hospital outbreaks. In the vast majority of isolates, all of the selected T6SS marker genes were present in each isolate (Figure 5C), including tssM1/2, which we had demonstrated to be oxidant-sensitive (Figure 4I). Notably, Kp ST258 isolates from pulmonary infections all conserved the T6SS genes with minimal SNPs (Figure 5D, no SNP identified in tssM-2) and expressed them (Figure 5E–F). While these findings do not indicate a direct role for the T6SS in pulmonary pathogenesis, their conservation in Kp ST258 isolates associated with healthcare-related pneumonias is consistent with participation in pathogenesis.

Figure 5. T6SS-encoding genes are conserved and expressed by Kp ST258 isolates worldwide.

(A) Decision tree showing inclusion (black boxes) and exclusion (red boxes) criteria used to determine which genome assembly samples were included for T6SS key gene screening (blue box) of publicly available dataset.

(B) Country of isolation for the K. pneumoniae ST258 genome assemblies from Pathogenwatch included in analysis (date of analysis − 22nd October 2020).

(C) The phylogenetic tree, created from Mash distances, has been midpoint-rooted and has tips coloured by country of sample isolation according to Pathogenwatch metadata. The figure was made in R using the R packages ggplot2 (v3.3.2,) (Wickham, 2009), sf (v0.9–7), rnaturalearth (v0.2.0), and rnaturalearthdata (v0.2.0). The heatmap shows the conservation of seven T6SS genes according to BLASTn results; ‘Good match’ in purple indicates a minimum 99.9% query coverage and nucleotide identity, ‘Partial match’ in yellow indicates coverage and identity of less than 99.9% but more than 80%, ‘No match’ in green indicates coverage and identity of less than 80%. The heatmap has been separated according to which T6SS loci the genes were located in, in the KPNIH1 chromosome (parental strain of MKP103): T6SS-1 includes tssB-1, tssC-1, hcp-1, vgrG-1, tssM-1; T6SS-2 includes tssM-2; and the additional hcp gene which did not sit in a region with other T6SS-associated genes. The phylogenetic tree and BLASTn results were visualized in R using the R packages ape (v5.4–1) (Paradis et al., 2004), phytools (v0.7–70) (Revell, 2012), ggplot2 (Wickham, 2009), ggtree (v1.16.6) (Yan et al., 2019), RColorBrewer (v1.1–2), and viridis (v0.5.1).

(D) The heatmap shows SNP counts in each of eight T6SS genes relative to KPNIH1. Colored asterisks indicate clinical Kp ST258 isolates (NR4643, NR5476, NR5076, NR5655, NR4957, NR5463, NR6210, NR6097, NR1686) which were also tested for T6SS gene expression in (E-F).

(E-F) Expression of T6SS genes from MKP103, Kp ST258 respiratory isolates and ΔtssM-2 (control for tssM-2 expression) by qRT-PCR, n = 6 biological samples from 3 independent experiments except for ΔtssM-2, whereby n = 4 biological samples from 2 independent experiments, columns represent mean values ± SEM, statistical analysis for (E-F) was performed by one-way ANOVA for each gene; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Among the many healthcare-associated pathogens, few have achieved the global prominence of Kp ST258 (Wyres et al., 2020). Our findings indicate that these pathogens stimulate a distinctive host metabolic profile compared to the hypervirulent KPPR1 strain or purified LPS. This metabolic response promotes tolerance to Kp ST258 infection. Disease tolerance, an inherent host response intended to limit pathogen-induced tissue damage, is indeed exploited by various pathogens for their persistence in the host (Martins et al., 2019; Medzhitov et al., 2012; Raberg et al., 2007; Schneider and Ayres, 2008). The metabolic stress associated with Kp ST258 infection contributes to the depletion of local glucose (Ahn et al., 2021). This drives host FAO and glutaminolysis, pathways that generate ROS via OXPHOS (Rashida Gnanaprakasam et al., 2018), creating a milieu that supports the polarization of macrophages with a higher M2/M1 ratio and the accumulation of immunosuppressive MDSCs. These cells, unlike mature neutrophils and monocytes, are not active participants in bacterial clearance (Ahn et al., 2016), and produce itaconate which further limits inflammation. MDSCs, which are difficult to accurately identify due to the lack of unique surface or intracellular markers, typically arise in oxidative stress-prone microenvironments, such as in tumors, and suppress the activation of immune effector cells (Groth et al., 2019), thereby promoting tumor growth (Veglia et al., 2021). Our data suggest that metabolically active Kp ST258 in the airway acts in a similar manner to proliferating tumor cells, inducing metabolic stress and promoting immunosuppressive MDSCs and macrophages. Thus, the metabolic milieu and accumulated immunosuppressive myeloid cells are sufficient to override the LPS-induced proinflammatory response, enabling indolent infection.

OXPHOS-induced ROS are as damaging to the pathogen as they are to the host. Kp ST258 adapts to this oxidant-replete milieu through the upregulation of the T6SS genes, although the specific effectors involved remain to be defined. Therapeutic strategies to manipulate the metabolic activities of immune cells, as has been successful in oncology, may be appropriate in the setting of infection, particularly with highly antibiotic-resistant opportunists, such as Kp ST258. While altering the metabolome to foster an immunostimulatory monocyte response may activate locally damaging inflammation, it should be possible to tailor the airway metabolome to both prevent bacterial adaptation and enhance the clearance of inhaled pathogens.

Limitations of study

The complex immunometabolic environment of the human airway is not fully represented by murine models of pneumonia. A more comprehensive study using human samples would strengthen the conclusions of our current study. In order to assess the biological relevance of host FAO during infection, we used the FAO inhibitor, etomoxir, which we appreciate has multiple off-target effects. These include the inhibition of the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) and mitochondrial complex I (Divakaruni et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2018), which were not assessed in this study. Such off-target effects were observed at high concentrations (Agius et al., 1991; Ceccarelli et al., 2011; Divakaruni et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2018), which far exceed what is required to inhibit Cpt activity. We tried to administer a lower dose of etomoxir in mice compared to other studies (Hossain et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the exact concentration of etomoxir in the lungs after the drug is metabolized is difficult to ascertain in vivo. In addition, the intricate airway metabolic milieu during Kp infection suggests that metabolic products other than ROS might also stimulate Kp T6SS expression and bacterial adaptation.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Requests for materials and resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Alice Prince (asp7@cumc.columbia.edu).

Materials availability

Bacterial strains used in this study are available from the lead contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

Dual and single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO (accession numbers GSE184563 and GSE190262 respectively) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession numbers are also listed in the Key Resources Table.

This paper does not report original code.

Data S1 represents an Excel file containing the values that were used to create all the graphs in the paper, as well as a processing script for the analysis of Figures 3, 4E and S4 (scRNA-seq analysis). Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD45 AF700 | BioLegend | Cat#103128; RRID:AB_493715 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b AF594 | BioLegend | Cat#101254; RRID:AB_2563231 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c BV605 | BioLegend | Cat#117333; RRID:AB_11204262 |

| Anti-mouse SiglecF AF647 | BD Biosciences | Cat#562680; RRID:AB_2687570 |

| Anti-mouse MHC II APC/Cy7 | BioLegend | Cat#107628; RRID:AB_2069377 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6C BV421 | BioLegend | Cat#128032; RRID:AB_2562178 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G PerCP/Cy5.5 | BioLegend | Cat#127616; RRID:AB_1877271 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| For all bacterial strains, see Table S1 | ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Chloramphenicol | Sigma | Cat#C0378 |

| Kanamycin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BP906–5 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Sigma | Cat#H1009 |

| Live/Dead Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain | Invitrogen | Cat#L23105A |

| Formalin free tissue fixative | Sigma | Cat#A5472 |

| Paraformaldehyde 32% | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat#15714-S |

| BPTES | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S7753 |

| Etomoxir | Sigma | Cat#E1905 |

| Isobutyric acid | Sigma | Cat#I1754 |

| Ammonium hydroxide | Sigma | Cat#221228 |

| Methanol | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A456–1 |

| Methanol | Alpha Aesar | Cat#22909 |

| Chloroform | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#C606SK-4 |

| Trypan blue stain | Invitrogen | Cat#T10282 |

| Glutamine | Agilent | Cat#103579–100 |

| Pyruvate | Agilent | Cat#103578–100 |

| Glucose | Agilent | Cat#103577–100 |

| N-acetyl cysteine | Sigma | Cat#A9165 |

| Carboxymethylcellulose | Sigma | Cat#419273 |

| Sodium acetate | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#S209 |

| Bovine serum albumin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#BP9705 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| E.Z.N.A Total RNA Kit I | Omega Bio-tek | Cat#R6834–01 |

| DNA-free DNA Removal Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#AM1906 |

| MICROBEnrich kit | Invitrogen | Cat#AM1901 |

| PM1 Microplate | Biolog | Cat#12111 |

| Seahorse XFe24 FluxPaks | Agilent Technologies | Cat#102340–100 |

| Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test Kit | Agilent Technologies | Cat#10301–100 |

| Mouse Cytokine Array / Chemokine Array 31-Plex | Eve Technologies | MD31 plex |

| Universal Prokaryotic AnyDeplete Kit | Tecan | Cat#0363–32 |

| AnyDeplete probe against mouse rRNA | Tecan | Cat#ADU002–32 |

| AnyDeplete probe against MKP103 rRNA | Tecan | Cat#ADU038–32 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Dual RNA-seq data (MKP103 and mouse transcriptional data) | This paper | GEO; GSE184563 |

| ScRNA-seq data (mouse) | This paper | GEO; GSE190262 |

| Raw genomic sequence data (MKP103) | This paper | ENA; PRJEB47143 |

| Raw data | Data S1 | |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J/N | Jackson Laboratories | JAX: 005304 |

| Mouse: C57BL/6 Irg1−/−/Acod1−/− | Jackson Laboratories | JAX: 029340 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| For all oligonucleotides, see Table S2 | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8.3.1 | GraphPad Software | www.graphpad.com |

| FlowJo X Flow cytometry | FlowJo | https://www.flowjo.com |

| Python | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org |

| R (version 4.0) | The R Project for Statistical Computing | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| R package: DESeq2 (version 1.20.0) | Love et al., 2014 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

| R package: biomaRt (version 2.46.0) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/biomaRt | |

| R package: fgsea (version 1.16.0) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/fgsea | |

| R package: ReactomePA (version 1.34.0) | Yu et al., 2016 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/ReactomePA |

| R package: enrichplot (version 1.14.2) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/enrichplot.html | |

| R package: clusterProfiler (version 3.18.1) | Yu et al., 2012 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html |

| R package: DOSE (version 3.20.1) | Yu et al., 2015 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DOSE.html |

| R package: org.HS.eg.db (version 3.14.0) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/org.Hs.eg.db.html | |

| R package: org.Mm.eg.db (version 3.14.0) | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/org.Mm.eg.db.html | |

| R package: msigdbr (version 7.4.1) | https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=msigdbr | |

| R package: STRINGdb (version 2.2.0) | Szklarczyk et al., 2019 | https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/STRINGdb.html |

| R package: pheatmap (version 1.0.12) | https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html | |

| R package: graphite (version 1.40.0) | Sales et al., 2018 | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/graphite.html |

| Other | ||

| RNAprotect bacteria reagent | QIAGEN | Cat#76506 |

| RNAprotect cell reagent | QIAGEN | Cat#76526 |

| Lysozyme | Sigma | Cat#L6876 |

| Proteinase K | QIAGEN | Cat#19131 |

| Multiscribe reverse transcriptase | Applied Biosystems | Cat#43–688-14 |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Mastermix | Applied Biosystems | Cat#25742 |

| Phosphate buffered saline | Corning | Cat#20–031 |

| ACK lysis buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A1049201 |

| RBC lysis buffer | Invitrogen | Cat#501129751 |

| DMEM medium | Corning | Cat#10–013-CV |

| Fetal bovine serum | Sigma | Cat#F4135 |

| Penicillin/streptomycin | Corning | Cat#30–002-CI |

| Murine GM-CSF | PeproTech | Cat#315–03 |

| Murine G-CSF | PeproTech | Cat#250–05 |

| Dispase | Gibco | Cat#17105–041 |

| Collagenase Type I | Invitrogen | Cat#17100–017 |

| Elastase | Worthington Biochemical Corporation | Cat#LS006365 |

| DNase | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#18068015 |

| Dragon beads 15.45 um | Bangs Laboratories Inc. | Cat#FS07F |

| Irradiated regular chow mouse diet | Purina | Cat#5053 |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Bacterial strains:

The bacterial strains used in this study are shown in Table S3. All strains were grown at 37°C on plates of Luria-Bertani (LB, Becton Dickinson (BD), 244610) supplemented with 1% agar (w/v, Acros Organics, 400400010). Overnight cultures and subcultures were grown in LB broth at 37°C with shaking. For the transposon mutants Tn::fadA and Tn::fadR, the LB agar contained 100 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Sigma, C0378). For the experiments that used LB broths supplemented with hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, (Sigma, H1009), the pH of the media was corrected to 7.0 prior to filter sterilization using 0.20 μm filters (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 725–2520). Bacterial inocula were estimated on the basis of the optical density at 600 nm, OD600nm, and verified by retrospective plating on agar plates to determine colony forming units (CFUs). K. pneumoniae MKP103 recovered from the mouse airways were selected on LB agar plates with and without kanamycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, BP906–5) at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml.

Mouse experiments:

All animal experiments were performed following institutional guidelines at Columbia University. Animals were housed and maintained at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) under regular rodent light/dark cycles at 18–23°C, and fed with irradiated regular chow diet (Purina Cat#5053, distributed by Fisher). Animal health was routinely checked by an institutional veterinary. The animal work protocol (AC-AABD5602) was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH, the Animal Welfare Act, and US federal law. Mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (C57BL/6NJ; stock number 005304, Irg1−/−; stock number 029340). WT BL/6NJ mice were purchased at 10–11 weeks old and maintained in our facilities (CUIMC) until 15–20 weeks old. Irg1−/− mice were bred and aged to 15–20 weeks (25–30 g) in our facilities. WT and Irg1−/− mice are immunocompetent animals. When using Irg1−/− mice, WT BL/6NJ mice were used as controls (not littermate controls). In vivo experiments were performed using roughly 50% female and 50% male animals. Sex was not expected to influence the final results of experiments. During studies, animals were randomly assigned to cages.

Primary cell culture (MDSC isolation):

Murine MDSCs were differentiated as described previously (Ahn et al., 2016). The femurs and tibias were surgically removed from C57BL/6 mice. The bone exterior was sterilized with 70% ethanol and the bone marrow was recovered by flushing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Corning, 20–031). The cell suspension was centrifuged for 6 min at 500 x g and resuspended in ACK lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A1049201) to remove the red blood cells. The lysis solution was quenched with PBS, and the cells were centrifuged again and resuspended in DMEM medium (Corning, 10–013-CV) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS v/v, Sigma, F4135) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, v/v, Corning, 30–002-CI)) supplemented with 40 ng/ml murine GM-CSF (PeproTech, 315–03) and 40 ng/ml G-CSF (PeproTech, 250–05). The GM-CSF/G-CSF-supplemented medium was replenished 3 days after isolation, and the MDSCs were mechanically detached on day 7, centrifuged, resuspended in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS (Sigma), and counted using trypan blue stain (Invitrogen, T10282). The cells were seeded at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml in a Seahorse XF24 well plate (Agilent, 102340–100) and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. For experiments using bone-marrow derived MDSCs, 50% of experiments were done using males and the other 50% using females.

METHOD DETAILS

Primers

The primers used in this study are listed in Table S4.

Construction of ΔtssM-2 MKP103 mutant using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing

To allow for efficient genetic manipulation in K. pneumoniae, we utilized our recently optimized single plasmid CRISPR-Cas9/lambda red recombineering system (Jiang et al., 2013; McConville et al., 2020; McConville et al., 2021). We used a pUC19 origin of replication, Streptococcus cas9 controlled by an araBAD promoter, a guide RNA (sgRNA) specific to the tssM-2 gene controlled by a pTAC promoter for constitutive expression, a 737-base pair (bp) area of homology to tssM-2, lambda red recombineering genes to improve the efficiency of homologous recombination and a zeocin resistance cassette. We first analyzed the wild type tssM-2 sequence via the CRISPRdirect website to identify an appropriate N20 sequence, which was incorporated into tssM-2 sgRNA. The homology was engineered to contain a 122-bp deletion surrounding the Cas9 cut site. The tssM-2 specific sgRNA and homology cassettes were cloned into the pUC19_CRISPR vector. The sequence confirmed plasmid was inserted into the K. pneumoniae MKP103 isolate via electroporation and appropriate transformants were identified through colony PCR. Transformants were grown at 30 °C under zeocin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, R25001) selection in LB and induced with 0.2% arabinose (v/v, Sigma, A3256) after 2 h. Following 6–8 h of induction, the cultures were diluted 1:100 and plated on LB supplemented with zeocin at 1000 μg/ml and 0.2% arabinose. Appropriate mutants were identified with colony PCR and Sanger sequencing (Genewiz). Mutants were cured of the CRISPR plasmid with serial passage on non-selective LB media.

Isolation of RNA from bacterial cultures

RNAprotect bacteria reagent (QIAGEN, 76506) was added to bacterial cultures, which were vortexed and incubated at room temperature (RT) for 10 min prior to centrifugation. Bacterial pellets were incubated in lysis buffer pH 8 (30 mM Tris (Corning, 46–030-CM), 1 mM EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1861283), 15 mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma, L6876) and 200 μg/ml proteinase K (QIAGEN, 19131)) at RT for 10 min followed by the addition of TRK lysis buffer (Omega Bio-tek, R6834–02) and 70% ethanol (v/v). The samples were transferred to E.Z.N.A. RNA isolation columns (Omega Bio-tek). RNA was isolated following the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with DNase using the DNA-free DNA removal kit (Invitrogen, AM1906).

Isolation of bacterial RNA from mouse lungs

Infected mouse lungs were excised and homogenized in PBS on ice. RNAprotect cell reagent (QIAGEN, 76526) was added to the lung homogenates, which were vortexed, incubated at RT for 10 min and pelleted. The pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (as above) and incubated at RT for 5 min prior to sonication (Fisher Scientific sonic dismembrator model 100) on ice. TRK lysis buffer and 70% ethanol (v/v) were then added and the samples were transferred to E.Z.N.A. RNA isolation columns (Omega Bio-tek). Total RNA (mixed RNA from host and bacteria) was isolated following the manufacturer’s instructions and treated with DNase using the DNA-free DNA removal kit (Invitrogen, AM1906). The RNA was precipitated and bacterial RNA was enriched using the MICROBEnrich kit (Invitrogen, AM1901) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and qRT–PCR

Multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, 43–688-14) was used to generate cDNA from RNA. qRT-PCR was performed using primers for genes of interest or housekeeping genes (Table S4), PowerUp SYBR Green Mastermix (Applied Biosystems, 25742) and a StepOne Plus thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems). Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method.

Growth assays

For bacterial growth curves, a U-bottomed, clear 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One, 650161) was prepared with either LB or LB supplemented with BPTES (Selleck Chemicals, S7753) and/or etomoxir (Sigma, E1905). Each well was inoculated with 1 μl overnight bacterial culture standardized to an OD600nm of 4. Absorbance at 600 nm was read every 10 min for 18 h on the SpectraMax M2 plate reader (Molecular Devices), as the plate incubated at 37°C with shaking.

Carbon source utilization assays

For Carbon Source Phenotype Microarray™ (Biolog) assays, a stock solution of 2 × 107 bacteria/ml was prepared in 1X IF-Oa buffer (Biolog, 72268) supplemented with 1X Redox Dye Mix A (Biolog, 74221). 100 μl of this stock solution (delivering 2 × 106 bacteria) was added to each well of a PM1 Microplate™ (Biolog, 12111) and the plate was incubated at 37°C overnight with shaking. Absorbance was read at 590 nm on the infinite M200 plate reader (TECAN).

LPS purification

Large-scale K. pneumoniae LPS preparations were isolated using a hot phenol/water extraction method after growth in LB broth supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C (Westphal and Jann, 1965). Subsequently, LPS was treated with RNase A, DNase I and proteinase K to ensure purity from contaminating nucleic acids and proteins (Fischer et al., 1983). Contaminating phospholipids and TLR2 were also removed (Folch et al., 1957; Hirschfeld et al., 2000). LPS preparations were resuspended in water, frozen on dry ice and lyophilized.

Lipid A isolation and analysis

K. pneumoniae strains were cultured for 18 h at 37°C with shaking in 5 ml LB. Lipid A was extracted from cell pellets using an ammonium hydroxide-isobutyric acid-based procedure (El Hamidi et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2017). Briefly, approximately 5 ml of cell culture was pelleted and resuspended in 400 μl of 70% isobutyric acid (Sigma, I1754) and 1 M ammonium hydroxide (Sigma, 221228), (5:3 v/v). Samples were incubated for 1 h at 100°C and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were collected, added to endotoxin-free water (1:1 v/v), snap-frozen on dry ice, and lyophilized overnight. The resultant material was washed twice with 1 ml methanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A456–1), and lipid A was extracted using 80 μl of a mixture of chloroform (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C606SK-4), methanol, and water (3:1:0.25 v/v/v). Once extracted, 1 μl of the concentrate was spotted on a steel re-usable MALDI plate (Hudson Surface Technology, PL-PD-000040-P) followed by 1 μl of 10 mg/ml norharmane matrix (Sigma, NG252) in chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v, Sigma) and air dried. All samples were analyzed on a Bruker Microflex mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics) in the negative-ion mode with reflectron mode. An electrospray tuning mix (Agilent, G2421A) was used for mass calibration. Spectral data were analyzed with Bruker Daltonics FlexAnalysis software (v4.30). The resulting spectra were used to estimate the lipid A structures present in each strain based on their predicted structures and molecular weights.

Extracellular flux analysis

An XFe24 sensor cartridge (Agilent, 102340–100) was calibrated as per the manufacturer’s instructions overnight at 37°C without CO2. On the day of infection, the MDSCs were washed once in Seahorse XF DMEM medium (Agilent, 103575–100) supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (Agilent, 103579–100), 1 mM pyruvate (Agilent, 103578–100) and 10 mM glucose (Agilent, 103577–100) 1 h before infection. The cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 and incubated at 37°C without CO2 for 3 h. The oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured using a Seahorse XFe24 analyzer (Agilent). Each measurement cycle consisted of a mixing time of 3 min and a data acquisition period of 3 min (total of 17 data points). BPTES (Selleck Chemicals) and etomoxir (Sigma) were added at final concentrations of 3 μM and 4 μM respectively to inhibit glutaminolysis and FAO. This was followed by the addition of oligomycin (Agilent, 103015–100) at 1.5 μM to suppress OXPHOS, FCCP (Agilent, 103015–100) at 2 μM to increase electron flow and OCR, and rotenone/antimycin A (Agilent, 103015–100) at 0.5 μM to inhibit OXPHOS.

Mouse infection

Mice were infected intranasally with 1 × 108 CFUs of K. pneumoniae MKP103 or 1 × 106 CFUs of K. pneumoniae KPPR1 in 50 μl PBS. Purified LPS was administered intranasally at 50 μg/mouse. PBS alone was used as a control. For experiments inhibiting FAO or glutaminolysis, mice were treated with 20 mg/kg etomoxir (Sigma) or 10 mg/kg BPTES (Selleck Chemicals) 24 h prior to and on the day of infection by intraperitoneal (IP) injection. Whenever both FAO and etomoxir were blocked, the mice were treated with 10 mg/kg BPTES 24 h prior to infection and with both 10 mg/kg BPTES and 20 mg/kg etomoxir on the day of infection. Similarly, mice were treated with the ROS scavenger, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC, Sigma, A9165), at 150 mg/kg by IP injection 24 h prior to and on the day of infection. The mice were sacrificed at 48 h post infection (peak of infection) and the BALF, lung and spleen were collected. The lung and spleen were homogenized through 40 μm cell strainers (Falcon, 352340). Aliquots of the BALF, lung and spleen homogenates were serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates to determine the bacterial burden. The BALF and lung homogenates were spun down and the BALF supernatant was collected for cytokine and untargeted metabolomic analysis. After hypotonic lysis of the red blood cells, the remaining BALF and lung cells were prepared for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis as described below. No calculation was used to determine the number of mice required. No data blinding was performed.

Histopathology of mouse lungs

Following euthanization, a canula was inserted into the trachea and tied with ligature. The thorax was opened and the lungs were fixed by gentle infusion of formalin free tissue fixative (Sigma, A5472) through the canula, which was connected to a fixative-filled syringe positioned 5 cm above the mouse, for 3–4 min. The whole mouse lung was excised, placed in formalin free tissue fixative for 24 h, 70% ethanol for 24 h and prepared in paraffin blocks. H&E staining was performed on 5 μm sections (two sections cut 25 μm apart for each mouse lung) for gross pathology.

Flow cytometry of mouse BALF and lung cells

For the identification of immune cell populations, mouse BALF and lung cells were stained in the presence of counting beads (15.45 μm DragonGreen, Bangs Laboratories Inc., FS07F) with LIVE/DEAD stain (Invitrogen, L23105A) and an antibody mixture of anti-CD45-AF700 (BioLegend, 103127), anti-CD11b-AF594 (BioLegend, 101254), anti-CD11c-Bv605 (BioLegend, 117334), anti-SiglecF-AF647 (BD, 562680), anti-MHCII-APC Cy7 (BioLegend, 107628), anti-Ly6C-Bv421 (BioLegend, 128032), and anti-Ly6G-PerCP-Cy5.5 (BioLegend #127616), each at a concentration of 1:200 in PBS, for 1 h at 4°C. After washing, the cells were stored in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Electron Microscopy Sciences, 15714-S) until analysis on the BD LSRII (BD Biosciences) using FACSDiva v9. Flow cytometry was analyzed with FlowJo v10. Mouse BAL and lung cells were identified as follows:

alveolar macrophages: CD45+CD11b+/−SiglecF+CD11c+;

monocytes: CD45+CD11b+SiglecF−MHCII−CD11c−Ly6G−Ly6C+/−;

neutrophils: CD45+CD11b+SiglecF− MHCII−CD11c−Ly6G+Ly6C+/−.

Cytokine analysis

Cytokine concentrations in mouse BALF supernatants were quantified by Eve Technologies (Calgary, Canada) using a bead-based multiplexing technology.

Untargeted metabolomic analysis

Metabolites in the BALF were identified and quantified by high-resolution liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) at the Calgary Metabolomics Research Facility (Calgary, Canada). The metabolites were extracted in a 50% methanol (Alpha Aesar #22909):water (v/v) solution. Sample runs were performed on a Q Exactive™ HF Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to a Vanquish™ UHPLC System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Syncronis HILIC UHPLC column (2.1 mm × 100 mm × 1.7 μm, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a binary solvent system at a flow rate of 600 μl/min. Solvent A consists of 20 mM ammonium formate pH 3 in mass spectrometry grade water and solvent B consists of mass spectrometry grade acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (v/v). The following gradient was used: 0–2 min, 100% B; 2–7 min, 100–80% B; 7–10 min, 805% B; 10–12 min, 5% B; 12–13 min, 5–100% B; 13–15 min, 100% B. A sample injection volume of 2 μl was used. The mass spectrometer was run in negative full scan mode at a resolution of 240,000 scanning from 50–750 m/z. Metabolites were identified by matching observed m/z signals (+/−10ppm) and chromatographic retention times to those observed from commercial metabolite standards (Sigma-Aldrich). The data were analyzed using E-Maven (Clasquin et al., 2012; Melamud et al., 2010) v0.10.0.

Metabolite set enrichment analyses

Differential metabolite abundance between samples was assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Differentially abundant metabolites (P < 0.05) were then used as input query sets in ‘clusterProfiler’ (Yu et al., 2012) using over-representation analysis based on the hypergeometric distribution to probe reference metabolite sets housed at HMDB and KEGG (compiled using ‘graphite’ in R), with reported P values adjusted for multiple comparison using Benjamini-Hochberg method. Enrichment plots and network diagrams were generated using ‘clusterProfiler’ and ‘DOSE’ (Yu et al., 2015).

DESI-MS

DESI-MS, an ambient ionization imaging technique, was performed to detect metabolites and their spatial distributions in situ. Prior to data acquisition, murine lungs were embedded in 2% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC, w/v, Sigma, 419273) (Nguyen et al., 2018; Stoeckli et al., 2007), sectioned to 10 μm thickness using a Leica CM3050 S cryostat (Columbia University Molecular Pathology Shared Resource (MPSR) histology service) and stored at −80°C. The frozen 10 μm lung tissues were dried for 20 min at 300 torr using a vacuum dessicator (Bel-Art). Briefly, DESI-MS was performed in the negative ion mode (−0.6 kV) from m/z 50–1000 using the Waters Synapt G2-Si QTOF coupled to a Waters DESI source with a motorized stage. The lung tissues were scanned under charged droplets generated from the electrospray nebulization of a histologically compatible solvent, methanol:acetonitrile 1:1 (v/v) containing 40 pg/μl of the internal standard leucine enkephalin (Leu-Enk) (Waters Corp.), that is used as a lock mass to correct any mass drifts during imaging runs (flow rate 1.5 μl/min). Raw MS files are processed using the HDI software (version 1.5, Waters Corp.) or exported to imzML (Schramm et al., 2012) to be used in SCiLS Lab MVS Pro (2020 version).

Generation of single-cell suspensions from whole mouse lung

Single-cell suspensions were prepared as described previously (Angelidis et al., 2019). Briefly, mouse lungs were excised and minced (approximately 1 mm2) in 1 ml of an enzyme mixture containing 20 mg/ml dispase (Gibco, 17105–041), 2 mg/ml collagenase type I (Invitrogen 17100–017), 1 mg/ml elastase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, LS006365), and 1 unit/ml DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 18068015). The minced lungs were digested at 37°C for 30 min and homogenized through a 70 μm strainer (Falcon, 352350), which was rinsed with 1 ml PBS containing 10% FBS four times to quench enzyme activity. The strained contents were centrifuged at 1,400 rpm for 7 min at 4°C and the supernatants were discarded. The cell pellets were resuspended in RBC lysis buffer (Invitrogen, 501129751) and incubated on ice for 3 min prior to the addition of PBS containing 10% FBS and centrifugation to remove red blood cells. The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in PBS containing 0.04% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA, Thermo Fisher Scientific BP9705) to a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml for 10x Genomics Chromium 3’ sc-RNA-seq microfluidic cell processing, library preparation, and sequencing. Libraries were prepared using Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3ʹ Reagent Kits v3.1 (10x Genomics) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Dual indexed libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) at a target read depth of at least 50,000 reads per cell. The data was processed using cellranger (v5.0.1) from 10x Genomics using the Mus musculus reference genome mm10–2020-A, and deposited to GEO (accession number GSE190262).

Single-Cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis

Preprocessing

10× 3’ scRNA-seq data was preprocessed and analyzed using the python package scanpy 1.8.1. Briefly, cell ranger outputs for four samples (lungs from an uninfected (PBS) BL/6 mouse or from BL/6 mice treated with live MKP103 or purified MKP103 LPS or an Irg1−/− mouse treated with live MKP103) were imported using the scanpy read_10x_mtx function, concatenated and indexed by sample ID. Cells with total counts less than 500 and greater than 100,000, as well as those with less than 200 unique genes or more than 50,000 were excluded from further analysis. Cells with mitochondrial read fractions of greater than 20% were assumed to be damaged or dying cells, and removed from further analysis. Genes with fewer than 3 unique counts in any cell were similarly filtered out. Read counts were normalized to 10,000 counts per cell and counts were subsequently log scaled. Highly variable genes were selected for downstream clustering analysis based upon mean expression of 0.1 – 20 (log scale) and a minimum dispersion of 0.1. Highly variable gene counts were then normalized for read depth and cell cycle effects by linear regression. Lastly, normalized highly variable gene counts were z-scored, with scale clipped to ± 10.

Dimensionality Reduction

Dimensionality reduction was performed first using Principle Component Analysis, with 50 returned components. Batch integration was performed using harmony 0.0.5 resulting in a batch-corrected PCA component matrix. Harmony-corrected PCA components were used for nearest neighbor detection with n_neighbors set to 30. Final dimensionality reduction using UMAP was done with min_dist set to 0.3.

Cell Type Annotation

Unbiased cell type annotation was performed using a proprietary multilayer deep neural network (DNN) trained to resolve single-cell expression data into cell type probabilities using pseudo-bulk combinations of 256 unique cell types collected from publicly available scRNA-seq databases, comprising >6M unique cells collected from 100+ atlas studies. Unbiased cell type scores were subsequently validated using established cell type marker genes prior to further analysis (Tables S1–2).

Gene set enrichment and scoring

Gene set scoring was performed using the scanpy rank_gene_groups function with enrichment calculated using a t-test score and benjamini-hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed using gseapy 0.10.5 using KEGG and GO Term gene sets as described.

Dual RNA-seq

Total RNA was isolated and treated with DNase as described above. The RNA was precipitated with 0.1 volume 3 M sodium acetate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, S209) and 3 volumes of 100% ethanol, recovered by centrifugation and washed with ice cold 70% ethanol. A ribosomal RNA (rRNA)-depleted cDNA library was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a customized Universal Prokaryotic RNA-seq Prokaryotic AnyDeplete kit (TECAN, 0363–32) to which specific probes against mouse rRNA (TECAN, ADU002–32) and Kp MKP103 (TECAN, ADU038–32) rRNA were added. The library was sequenced with Illumina HiSeq. Raw base calls were converted to fatsq files using Bcl2fastqs. The raw reads were aligned and filtered for quality using the RNA-Seq Advanced Pipeline Deployment (RAPiD) pipeline (Shah et al., 2015). The raw reads were aligned to the genome of Mus musculus (GRCm38 Gencode vM21), using STAR-Aligner v2.7.3a. The raw counts for each gene were quantified using Subreads:FeatureCounts v1.6.3 and processed for differential gene expression using DEseq2 (Love et al., 2014) in R v3.5.3. Using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), transcript abundance was modeled as a function of mouse genotype (WT vs Irg1−/−) and infection status (PBS vs Kp), with reported P-values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Heatmaps of row-normalized expression data were generated using ‘pheatmap’. Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) (Subramanian et al., 2005) were conducted in R, employing preranked GSEA (‘fgsea’) using the Wald statistic from expression modeling to assign gene rank. We used ‘msigdbr’ to query reference gene sets at MSigDB (Broad Institute/MIT) (Liberzon et al., 2011), including global analysis of KEGG, GO, and Reactome gene sets, and targeted analyses within specific Biocarta, WikiPathways, hallmark and transcription factor target gene sets. GSEA plots were generated using ‘fgsea’ and ‘clusterProfiler’ (Yu et al., 2012). Reported P values were adjusted for multiple comparison using Benjamini-Hochberg method.

An in-house python script (https://github.com/AnnaSyme/genbank_to_kallisto.py) was used to generate a reference transcriptome for bacterial transcriptional analyses. A count table was generated by pseudo-aligning RNA sequence data to the reference transcriptome using Kallisto (Bray et al., 2016) with default settings. Differential gene expression analysis was computed using Degust (v4.1.1) (Powell, 2019) with the minimum read count set to 10, and analysis method set to Voom/Limma. The bacterial transcriptional data were plotted as a volcano plot and a parallel coordinates plot using GraphPad Prism (v7.0c) and Degust (Powell, 2019) respectively. Bulk sequencing data have been deposited to GEO (accession number GSE184563).

Whole genome sequencing of MKP103 and alignment with KPNIH1

Hybrid genome assembly of the Kp ST258 representative strain MKP103 was computed using PacBio and Illumina-derived sequences and Unicycler (Wick et al., 2017) with default settings. The assembled genome was annotated using Prokka (Seemann, 2014) against the publicly available genome of the parental strain KPNIH1 (accession number NZ_CP008827.1) as a reference. Snippy (https://github.com/tseemann/snippy) was used to identify any variants in the assembled MKP103 genome against the parental strain KPNIH1 as reference. Raw sequence data were submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under accession number PRJEB47143. Given that no major differences were observed between the genomes of MKP103 and KPNIH1 other than the expected deletion of the blaKPC3 (Ramage et al., 2017) and blaTEM1 genes on the pKpQIL plasmid from MKP103, we used the KPNIH1 genome to identify the T6SS genes.

Identification and annotation of T6SS loci in the KPNIH1 genome

We selected seven conserved putative T6SS genes that were previously identified in silico in the genomes of other Kp strains (Sarris et al., 2011; Storey et al., 2020) (hereon referred to as tssB-1, tssC-1, hcp-1, vgrG-1, tssM-1, tssM-2, and hcp). We screened the KPNIH1 genome for these orthologues via a nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (v2.11.0) search (minimum query coverage and nucleotide identity of 80%) (Altschul et al., 1990). The positional information for each BLAST hit (start and stop sites) was used to identify the position and corresponding coding sequence (gene) in the genome of KPNIH1. The upstream and downstream sequences around these genes/gene clusters were extracted. Predicted genes were submitted for the identification of T6SS-associated signatures and curated manually. An initial sequence length of 25 kbp both upstream and downstream of each key gene was extracted; in cases where this region included another of the key genes, the regions were concatenated. Similarly, if manual curation of the coding sequencing revealed the presence of a T6SS-associated gene adjacent to the end of the region, this was extended by a further 10 kbp. For visualization purposes the two T6SS-regions were ‘trimmed’ to the final T6SS-associated gene in either direction; non-T6SS-associated flanking regions were removed from the image (Figure 4G).

Genomic analysis of public data

These same seven key genes (tssB-1, tssC-1, hcp-1, vgrG-1, tssM-1, tssM-2, and hcp) were used in order to identify their presence and conservation, and therefore that of the two main T6SS loci (T6SS-1 included tssB-1, tssC-1, hcp-1, vgrG-1, and tssM-1; T6SS-2 included tssM-2) in a larger more temporally and geographically diverse dataset. We downloaded and analyzed all genome assemblies meeting our inclusion criteria (Figure 5A) from the Pathogenwatch platform (https://pathogen.watch) as of the 22nd October 2020. These genome assemblies (n=2401) underwent a nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (v2.11.0) analysis (Altschul et al., 1990) (minimum query coverage and nucleotide identity of 80%) to identify the presence and conservation of the seven key genes. Concurrently, to infer the population structure, mashtree (v1.2.0, https://github.com/lskatz/mashtree) (Katz et al., 2019) was run on all genome assemblies (2401 from Pathogenwatch, 2 from this study, NR1686 and NR5466 (Macesic et al., 2020), and KPNIH1).

Analysis of T6SS marker genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in Kp ST258 clinical pulmonary isolates.

We screened the genomes of 47 deidentified clinical Kp ST258 isolates from pulmonary infections for the same seven T6SS marker genes as above, as well as tssH-1 encoding the ClpV ATPase. Sequencing reads from each isolate were aligned to the KPNIH1 genome using Snippy to identify SNPs across the genome and in the genes of interest. Core genome concatenated SNPs were used to generate a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction of isolates from this study (Figure 5D) with RAxML. SNPs in each isolate relative to KPNIH1 in the T6SS marker genes are shown as a heatmap (Figure 5D).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We modelled the number of independent experiments required to reach significance between groups using the computer program JMP. This simulation was based on experimental design, preliminary data and past experience. Analyses were performed assuming a 20% standard deviation and equivalent variances within groups. Significance < 0.05 with power 0.8 was used. Experiments in this study were not performed in a blinded fashion with the exception of the histopathology scoring. All analyses and graphs were performed using the GraphPad Prism 7a and 8 software. Values in graphs are shown as average ± SEM and data were assumed to follow a normal distribution. For comparison between average values for more than two groups, we performed one-way ANOVA with a multiple posteriori comparison. When studying two or more groups along time, data was analyzed using two-way ANOVA with a multiple posteriori comparison. Differences between two groups were analyzed using a Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test otherwise. Differences were considered significant when a P value under 0.05 (P < 0.05) was obtained. Statistical details of experiments are indicated in each figure legend. No data points were excluded.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

This study did not generate additional resources.

Supplementary Material

Data S1. Source data, related to Figures 1–5 and S1–S5 (unprocessed source data underlying graphs for Figures 1–5, S1–S3 and S5 and processing script for the analysis of scRNA-seq shown in Figures 3, 4E and S4)

Document S1. Figures S1–S5

Table S1. List of genes expressed by each cell type in scRNA-seq analysis, related to STAR Methods

Table S2. List of markers used as selection criteria, related to STAR Methods

Table S3. Bacterial strains used in this study, related to STAR Methods

Table S4. Primers used in this study, related to STAR Methods

Research highlights:

Kp ST258 stimulates a distinct host metabolic response versus a hypervirulent strain

Live Kp ST258, not LPS, induces host glutaminolysis and fatty acid oxidation

Kp infection promotes the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and M2-like macrophages

Kp ST258 activates the Type VI Secretion System in response to host oxidants

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Kwintkiewicz (TECAN) for technical support with the customized Universal Prokaryotic RNA-seq library preparation kit. This work was supported by NIH grants 1R35HL135800 to A.P., K08 HL138289 to D.A., T32 AI100852-04 and K08 AI146284 to T.H.M., R01AI116939 (NIAID) to A.C.U., NIH grants NCI P01CA87497, NCI R35CA209896, NINDS R61NS109407 and NINDS R33NS109407 to B.R.S. and NHMRC Investigator grant (Australia) APP1196103 to B.P.H. This study was also supported by NIH grant S10RR027050 to the Columbia Center for Translational Immunology (CCTI) Flow Cytometry Core, NIH (NCI) grant P30CA013696 to the Molecular Pathology Shared Resource (MPSR) of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University and NIH (CTSA) grant UL1TR001873 to the Single Cell Analysis Core at the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center. The Calgary Metabolomics Research Facility (CMRF) is supported by the International Microbiome Centre and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI-JELF 34986). I.A.L is supported by an Alberta Innovates Translational Health Chair. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

B.R.S. is an inventor on patents and patent applications related to GPX4 and ferroptosis, a consultant to and co-founder of Inzen Therapeutics and Nevrox Limited, and a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Weatherwax Biotechnologies Corporation. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agius L, Meredith EJ, and Sherratt HS (1991). Stereospecificity of the inhibition by etomoxir of fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis in isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochem Pharmacol, 42, 1717–20. 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn D, Bhushan G, Mcconville TH, Annavajhala MK, Soni RK, Wong Fok Lung T, Hofstaedter CE, Shah SS, Chong AM, Castano VG, et al. (2021). An acquired acyltransferase promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 respiratory infection. Cell reports, 35, 109196. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn D, Penaloza H, Wang Z, Wickersham M, Parker D, Patel P, Koller A, Chen EI, Bueno SM, Uhlemann AC, et al. (2016). Acquired resistance to innate immune clearance promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 pulmonary infection. JCI Insight, 1, e89704. 10.1172/jci.insight.89704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, and Lipman DJ (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol, 215, 403–10. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelidis I, Simon LM, Fernandez IE, Strunz M, Mayr CH, Greiffo FR, Tsitsiridis G, Ansari M, Graf E, Strom TM, et al. (2019). An atlas of the aging lung mapped by single cell transcriptomics and deep tissue proteomics. Nat Commun, 10, 963. 10.1038/s41467-019-08831-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. (2022). Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet, 399, 629–655. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcari G, Raponi G, Sacco F, Bibbolino G, Di Lella FM, Alessandri F, Coletti M, Trancassini M, Deales A, Pugliese F, et al. (2021). Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in COVID-19 patients: a 2-month retrospective analysis in an Italian hospital. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 57, 106245. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambouskova M, Gorvel L, Lampropoulou V, Sergushichev A, Loginicheva E, Johnson K, Korenfeld D, Mathyer ME, Kim H, Huang LH, et al. (2018). Electrophilic properties of itaconate and derivatives regulate the IkappaBzeta-ATF3 inflammatory axis. Nature, 556, 501–504. 10.1038/s41586-018-0052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Ho BT, and Mekalanos JJ (2013). Tit-for-tat: type VI secretion system counterattack during bacterial cell-cell interactions. Cell, 152, 884–94. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler M, Pilhofer M, Henderson GP, Jensen GJ, and Mekalanos JJ (2012). Type VI secretion requires a dynamic contractile phage tail-like structure. Nature, 483, 182–6. 10.1038/nature10846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolnaya LM, Tilvawala R, Elfenbein JR, Cirillo JD, and Andrews-Polymenis HL (2020). Linearized Siderophore Products Secreted via MacAB Efflux Pump Protect Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium from Oxidative Stress. mBio, 11. 10.1128/mBio.00528-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, and Pachter L (2016). Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol, 34, 525–7. 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberg CA, Wu W, Cavalcoli JD, Miller VL, and Bachman MA (2014). Complete Genome Sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain ATCC 43816 KPPR1, a Rifampin-Resistant Mutant Commonly Used in Animal, Genetic, and Molecular Biology Studies. Genome Announc, 2. 10.1128/genomeA.00924-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler PK, Zinkernagel AS, Hofmaenner DA, Wendel Garcia PD, Acevedo CT, Gomez-Mejia A, Mairpady Shambat S, Andreoni F, Maibach MA, Bartussek J, et al. (2021). Bacterial pulmonary superinfections are associated with longer duration of ventilation in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep Med, 2, 100229. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, and Parkhill J (2009). DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics, 25, 119–20. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]