Abstract

Background

Substance use disorder (SUD) is the continued use of one or more psychoactive substances, including alcohol, despite negative effects on health, functioning, and social relations. Problematic drug use has increased by 10% globally since 2013, and harmful use of alcohol is associated with 5.3% of all deaths. Direct effects of music therapy (MT) on problematic substance use are not known, but it may be helpful in alleviating associated psychological symptoms and decreasing substance craving.

Objectives

To compare the effect of music therapy (MT) in addition to standard care versus standard care alone, or to standard care plus an active control intervention, on psychological symptoms, substance craving, motivation for treatment, and motivation to stay clean/sober.

Search methods

We searched the following databases (from inception to 1 February 2021): the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Specialised Register; CENTRAL; MEDLINE (PubMed); eight other databases, and two trials registries. We handsearched reference lists of all retrieved studies and relevant systematic reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing MT plus standard care to standard care alone, or MT plus standard care to active intervention plus standard care for people with SUD.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard Cochrane methodology.

Main results

We included 21 trials involving 1984 people. We found moderate‐certainty evidence of a medium effect favouring MT plus standard care over standard care alone for substance craving (standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) –1.23 to –0.10; 3 studies, 254 participants), with significant subgroup differences indicating greater reduction in craving for MT intervention lasting one to three months; and small‐to‐medium effect favouring MT for motivation for treatment/change (SMD 0.41, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.61; 5 studies, 408 participants). We found no clear evidence of a beneficial effect on depression (SMD –0.33, 95% CI –0.72 to 0.07; 3 studies, 100 participants), or motivation to stay sober/clean (SMD 0.22, 95% CI –0.02 to 0.47; 3 studies, 269 participants), though effect sizes ranged from large favourable effect to no effect, and we are uncertain about the result. There was no evidence of beneficial effect on anxiety (mean difference (MD) –0.17, 95% CI –4.39 to 4.05; 1 study, 60 participants), though we are uncertain about the result. There was no meaningful effect for retention in treatment for participants receiving MT plus standard care as compared to standard care alone (risk ratio (RR) 0.99, 95% 0.93 to 1.05; 6 studies, 199 participants).

There was a moderate effect on motivation for treatment/change when comparing MT plus standard care to another active intervention plus standard care (SMD 0.46, 95% CI –0.00 to 0.93; 5 studies, 411 participants), and certainty in the result was moderate. We found no clear evidence of an effect of MT on motivation to stay sober/clean when compared to active intervention, though effect sizes ranged from large favourable effect to no effect, and we are uncertain about the result (MD 0.34, 95% CI –0.11 to 0.78; 3 studies, 258 participants). There was no clear evidence of effect on substance craving (SMD –0.04, 95% CI –0.56 to 0.48; 3 studies, 232 participants), depression (MD –1.49, 95% CI –4.98 to 2.00; 1 study, 110 participants), or substance use (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.29; 1 study, 140 participants) at one‐month follow‐up when comparing MT plus standard care to active intervention plus standard care. There were no data on adverse effects.

Unclear risk of selection bias applied to most studies due to incomplete description of processes of randomisation and allocation concealment. All studies were at unclear risk of detection bias due to lack of blinding of outcome assessors for subjective outcomes (mostly self‐report). We judged that bias arising from such lack of blinding would not differ between groups. Similarly, it is not possible to blind participants and providers to MT. We consider knowledge of receiving this type of therapy as part of the therapeutic effect itself, and thus all studies were at low risk of performance bias for subjective outcomes.

We downgraded all outcomes one level for imprecision due to optimal information size not being met, and two levels for outcomes with very low sample size.

Authors' conclusions

Results from this review suggest that MT as 'add on' treatment to standard care can lead to moderate reductions in substance craving and can increase motivation for treatment/change for people with SUDs receiving treatment in detoxification and short‐term rehabilitation settings. Greater reduction in craving is associated with MT lasting longer than a single session. We have moderate‐to‐low confidence in our findings as the included studies were downgraded in certainty due to imprecision, and most included studies were conducted by the same researcher in the same detoxification unit, which considerably impacts the transferability of findings.

Keywords: Humans, Anxiety, Anxiety/therapy, Bias, Craving, Music Therapy, Substance-Related Disorders, Substance-Related Disorders/therapy

Plain language summary

Music therapy for people with substance use disorder

What was the aim of this review?

We aimed to assess if music therapy given in addition to standard care was effective for people with substance use disorders, in terms of impacting substance craving, motivation for treatment, and motivation for staying sober/clean. We were also interested in evidence about effects on depression and anxiety, as these are risk factors for relapse.

Key messages

Music therapy as 'add on' treatment to standard care likely reduces substance craving and increases motivation for treatment for adults in detoxification and rehabilitation settings. Music therapy lasting longer than a single session is associated with greater reductions in substance craving. There is no evidence of an effect on depressive symptoms, anxiety, motivation to stay sober/clean, or retention in treatment. There were no data on adverse events.

Why is it important to do this review?

This review can help determine if music therapy has a beneficial impact on certain aspects of problematic substance use and motivation for treatment.

What did this review study?

Substance use disorder is the continued use of drugs, both illegal drugs and prescription medicines, with or without alcohol, even when these substances cause health problems or negatively affect social functioning. Approximately 35 million people worldwide engage in problematic drug use, and more than three million deaths each year are attributed to the harmful consumption of alcohol. Music therapy addresses the mental and physical needs of people undergoing substance use treatment, through use of a range of active and receptive forms of musical engagement that enable various health‐promoting neurobiological, psychological, and social processes. Music therapists are health professionals who use specific music interventions to help their clients manage emotions, cope with triggers, experience mastery, and form healthy interpersonal relationships.

What were the main results of the review?

We included 21 studies with 1984 people. All participants were diagnosed with substance use disorder, with 52% reporting alcohol as their substance of choice. In two studies, participants had co‐occurring mental health diagnoses. All studies were completed in either detoxification settings or longer‐term substance use treatment facilities. Studies compared music therapy added to standard care to standard care alone or to other types of intervention that would be a typical part of treatment for substance use, such as verbal therapy. The quality of the performed trials and the reported results varied, which affected our confidence in the results.

Our findings suggest that music therapy added to standard care likely reduces substance craving when compared to standard care alone for people with substance use disorders receiving treatment in detoxification and short‐term rehabilitation settings. Music therapy intervention lasting longer than a single session is associated with greater reduction in craving. Furthermore, music therapy likely improves motivation for treatment/change more than standard care alone, and may improve motivation for treatment/change more than other active treatments. We found no evidence of an effect of music therapy on depressive symptoms, anxiety, and motivation to stay sober/clean.

We have low‐to‐moderate confidence in our findings, and caution that it might be difficult to transfer our findings to other settings, since most included studies were conducted by the same researcher in the same detoxification unit.

We know that substance craving is diminished better when there is more than one session of music therapy, but we do not know if the number of music therapy sessions received impacts other outcomes. Additionally, we do not know if one form of music therapy works better than others for these outcomes.

Only one study reported a source of funding (National Key R&D Program of China, primary funder).

How up‐to‐date is this review?

This evidence is current to 1 February 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Music therapy plus standard care versus standard care alone for people with substance use disorders.

| Music therapy plus standard care versus standard care alone for people with substance use disorders | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with substance use disorders Setting: detox and inpatient/outpatient rehabilitation settings Intervention: music therapy plus standard care Comparison: standard care alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with music therapy | |||||

|

Psychological symptoms (depression) Assessed with: various scales Scale: various (higher score worse) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean depression in music therapy was 0.33 standard deviations lower (0.72 lower to 0.07 higher) |

— | 100 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

— |

|

Psychological symptoms (anxiety) Assessed with: Self‐report Anxiety Scale Scale: 20–80 (higher score worse) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

The mean anxiety score for standard care was 46.1 | Music therapy was 0.17 lower (4.39 lower to 4.05 higher) |

— | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb |

— |

|

Substance craving Assessed with: Scale: various (higher score worse) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean substance craving in music therapy was 0.66 standard deviations lower (1.23 lower to 0.10 lower) |

— | 254 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

— |

|

Motivation for treatment/change Assessed with: various scales Scale: various (higher score better) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean motivation for treatment in music therapy was 0.41 standard deviations higher (0.21 higher to 0.61 higher) |

— | 408 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

— |

|

Motivation to stay sober/clean Assessed with: various scales Scale: various (higher score better) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean motivation for sobriety in music therapy was 0.22 standard deviations higher (0.02 lower to 0.47 higher) |

— | 269 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

— |

|

Retention in treatment Assessed with: number participants retained at end of treatment |

Study population | RR 0.99 (0.93 to 1.05) | 199 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea |

Higher retention better. | |

| 725 per 1000 | 718 per 1000 (674 to 761) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | — | — | — | — | — | No studies reported serious adverse events. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for imprecision: optimal information size not met. bDowngraded two levels for imprecision: very low sample size.

Summary of findings 2. Music therapy plus standard care compared to active intervention plus standard care.

|

Patient or population: people with substance use disorders Setting: detox and inpatient/outpatient rehabilitation settings Intervention: music therapy plus standard care Comparison: active intervention plus standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with active intervention | Risk with music therapy | |||||

|

Psychological outcomes (depression) Assessed with: Beck Depression Inventory Scale: 0–63 (higher score worse) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

Mean depression for active intervention was 20.3 | Music therapy was 1.49 lower (4.98 lower to 2.00 higher) |

— | 110 (1 RCT)a | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— |

|

Substance craving Assessed with: various scales Scale: various (higher score worse) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean substance craving in music therapy was 0.04 standard deviations lower (0.56 lower to 0.48 higher) |

— | 232 (3 RCTs)a | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c |

— |

|

Motivation for treatment/change Assessed with: various scales Scale: various (higher score better) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

— | Mean motivation for treatment in music therapy was 0.46 standard deviations higher (0 lower to 0.93 higher) |

— | 411 (5 RCTs)a | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— |

|

Motivation to stay sober/clean Assessed with: Likert Scale: 1–7 (higher score better) Follow‐up: end of treatment |

Mean motivation to stay sober in active intervention ranged from 6.2 to 6.4 | Music therapy was 0.34 higher (0.11 lower to 0.78 higher) |

— | 258 (3 RCTs)a | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb |

— |

| Retention in treatment | — | — | — | — | — | No studies reported retention in treatment. |

| Serious adverse events | — | — | — | — | — | No studies reported serious adverse events. |

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aNumber of participants adjusted for cluster randomisation. bDowngraded one level for imprecision: optimal information size not met. cDowngraded one level for inconsistency: substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 70%) likely affecting interpretation of results and with no plausible explanation.

Background

Description of the condition

Problematic substance use and related high‐risk behaviour have a negative impact on individuals, families, and global public health. The burden of problematic substance use to systems such as healthcare, criminal justice, and unemployment/welfare is substantial (WHO 2018). The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 cited 3.0 million deaths in 2016 were attributable to the harmful use of alcohol, representing 5.3% of all deaths (WHO 2018, p.63). In addition, 5.1% of the global burden of disease, expressed as 132.6 million net disability‐adjusted life years, can be attributed to alcohol consumption (WHO 2018, p.64). Problematic use of drugs and alcohol is a widespread issue; approximately 35.6 million people worldwide experienced drug use disorder in 2018, amounting to 0.62% of the adult population (aged 15 to 64 years) (UNODC 2020), and 4.9% of the world's population aged 15 years or older demonstrated either harmful use of alcohol or alcohol dependence (WHO 2018). While both the number of deaths related to alcohol use and the number of people engaging in harmful alcohol consumption appear to have stabilised from 2013 to 2018, the number of people engaging in problematic drug use increased by approximately 10% since 2013 (UNODC 2018). This increase is mainly attributed to the increase in opioid use, where global opium production has more than doubled between 2015 and 2017 (UNODC 2018). Opioids also continue to cause the most harm, as 66% of deaths that are directly drug‐related are caused by opium and its derivatives (UNODC 2020).

Substance use disorders (SUDs) may be defined as the use of one or more psychoactive substances, medically prescribed or not (WHO 1994), in a manner that results in continued use despite significant substance‐related problems in areas of the person's cognitive, behavioural, physiological, or social functioning (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM‐5), APA 2013). People who inject drugs are at higher risk of death. This harm is partly due to fatal overdoses or the transmission of lethal infectious diseases (UNODC 2018). More than half of people who inject drugs live with hepatitis C and approximately 12% of them are diagnosed with HIV (UNODC 2018). Worldwide, an estimated one in every six people with problematic drug use receives necessary treatment; if all people with problematic drug use sought treatment, the resulting cost would represent 0.3% to 0.4% of the global gross domestic product (INCB 2019). Although the economic burden of treatment is considerable, the costs of crime‐related law enforcement and judiciary services and healthcare provision for untreated problematic drug use remain far higher than that of prevention and treatment (INCB 2019).

Research‐based principles of substance use addiction treatment suggest that SUD is a complex but treatable disease (NIDA 2018). Successfully treating people who have SUDs demands a diversity of treatment procedures and areas of treatment focus, due to the diversity of personal characteristics and substance(s) used. Treatment must meet the complex biopsychosocial needs of the person involved, and thus must be multidisciplinary in nature. Longer lengths of residential substance use treatment are associated with better engagement in aftercare programmes and lower levels of substance use at long‐term follow‐up (Arbour 2011; Moos 2007). Improved treatment retention also predicts lower recidivism rates in criminally convicted individuals with co‐occurring substance use and mental health disorders (Jaffe 2012). Supporting retention in multidisciplinary treatment remains a crucial aspect of addressing the harms caused by SUDs, but at the same time remains one of the greatest challenges. In the USA, approximately 26% of people with problematic substance use drop out of public treatment programmes (SAMHSA 2019). People with problematic substance use who have co‐occurring mental health disorders demonstrate even lower treatment retention rates. Gender‐specific retention strategies are an important means of promoting treatment retention among people with problematic substance use with co‐occurring mental health disorders (Choi 2015).

People with SUDs often experience emotional dysfunction, which can contribute to the development of the disorder. People with SUDs commonly experience co‐occurring affective disorders such as depression and anxiety (London 2004), as well as post‐traumatic stress disorder (Ouimette 2005; van Dam 2012). In addition, people with SUDs demonstrate dysfunction in emotion regulation, such as dampened inhibition of intense affects and abnormal emotional reactions to emotional stimuli (Chen 2018; O'Daly 2012; Wilcox 2016). Research demonstrates functional changes in emotion‐related brain areas in people with SUDs, including abnormalities in the activation of the insula and amygdala, as well as hypoactivity in the anterior cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Gilman 2008; Salloum 2007).

Description of the intervention

Music therapy (MT) is "the systematic use of specific musical interventions (based upon musical, aesthetic, clinical, scientific, and practice‐based research as well as tacit knowledge) by an accredited music therapist to realise individual treatment goals within a therapeutic alliance" (NVvMT 2017, pp.11–12). In MT, therapeutic change occurs via engagement in musical experiences and by the relationships that develop through them (Bruscia 1998). Music therapists engage participants in a range of active and receptive approaches to listening to, discussing, creating, improvising, and performing music. MT may incorporate varying levels of verbal processing, depending upon the needs of the participant(s) and the theoretical orientation of the music therapist. Sessions can occur with individuals, groups, or with communities, and may include various approaches such as songwriting; discussion and analysis of song lyrics; instrumental or vocal improvisation, or both; music performance; and music‐assisted relaxation. MT may be practised from a variety of theoretical orientations, and in the setting of substance use treatment may include elements of cognitive‐behavioural; humanistic; psychodynamic or neurobiological theory, or both; among others. MT is an integrated part of multidisciplinary substance use treatment in many countries. Music therapists work within abstinence‐based, controlled use, and harm reduction contexts (Aldridge 2010; Ghetti 2004), in inpatient treatment centres, community mental health centres, adult day and ambulant healthcare centres, state and general hospitals, therapeutic communities, and aftercare programmes (Aldridge 2010; Ghetti 2004; Silverman 2009).

The modern profession of MT began in the 1940s and 1950s, with the establishment of academic and clinical training programmes in the USA, Austria, and the UK, followed by developments in other parts of Europe, North and South America, Africa, Australia, and Asia (Bunt 2014). The academic preparation required for professional practice currently varies by country, although many countries require master's level training in MT.

How the intervention might work

MT addresses the biopsychosocial needs of people undergoing multidisciplinary substance use treatment. Various forms of engagement in musical experiences are systematically and intentionally employed by music therapists to trigger specific neurological, biological, psychological, and social mechanisms. Music therapists understand and utilise the various ways that music induces emotions, including via brain stem reflexes, rhythmic entrainment, evaluative conditioning, emotional contagion, visual imagery, episodic memory, musical expectancy, and aesthetic judgement (Juslin 2013; Juslin 2019). This emotional activation and improved emotion regulation can then lead to increased motivation and sustained engagement in the therapeutic music process, enabling progress towards therapeutic goals (Bruscia 2014). MT approaches are sequenced over time in direct relation to participants' needs and readiness, building upon their resources (Rolvsjord 2010) and introducing therapeutic challenges when appropriate (Bruscia 2014).

Music therapy as emotion regulation

Music therapists are informed by an awareness of the neurobiological impacts of music on human emotions, and consider this level of influence as they engage with participants in music‐making. At a neurobiological level, music that provokes peak experiences stimulates neural reward and emotion systems similar to those that are activated by (illicit) drug use (Blood 2001), which can result in dopamine release (Salimpoor 2011). Owing to these patterns of neural activity, music can be shaped by a qualified music therapist to promote positive mood states, including euphoria, and to enable emotion regulation (Hakvoort 2020; Koelsch 2015; Salimpoor 2011; Sena Moore 2013). As music provides a means of promoting positive mood states (Koelsch 2014), it may consequently buffer against the risk of relapse that is associated with negative mood states (Koob 2013). Furthermore, pleasurable music can promote the release of dopamine to positively affect the reward system (Blum 2010), and can inhibit activity in areas of the limbic system in a way that inhibits transmission of pain perception (Neugebauer 2004). Music therapists intentionally utilise musical experiences to enable these mechanisms of emotion regulation, reward, and pain relief.

People with SUD often use substances as a strategy for coping with difficult emotions. In addition to impacting neurological systems associated with emotion regulation and reward, MT enables the development of a broader and more flexible array of strategies for coping with emotions (Dijkstra 2010). MT offers a means for expressing and working through a broad range of emotions in an adaptive way, which is particularly helpful for participants who have difficulty expressing emotions verbally (Baker 2007). Some participants may need to experience and work through emotions non‐verbally as a prerequisite to being able to benefit from verbal forms of therapy.

Music therapy and substance craving

Since music readily acts upon neural activity, special consideration is necessary when using music therapeutically in people with SUDs. Individuals with SUDs can experience a decrease in substance craving after listening to songs they identify as helping them stay clean/sober, but they may also experience an increase in substance craving after listening to songs they identify as making them want to use substances (Short 2015). Thus, important aims of MT within substance use treatment include gaining awareness of healthy and unhealthy uses of music, and understanding how context impacts perception of the music (Hohmann 2017; McFerran 2016). Furthermore, strong personal associations between music and substance use, some of which can contribute to relapse when left unexamined, can be successfully addressed and reversed in MT (Horesh 2010). Individuals learn to recognise, retrain, and integrate state‐specific emotional responses to music as part of their lifestyle (Fachner 2017).

Music therapy for motivation

People with SUDs who participate in MT may experience increased motivation to engage in treatment, which may then generalise to other facets of substance use treatment (Hohmann 2017; Horesh 2010). Gains in motivation for change are also evident in people with co‐occurring mental health disorders who engage in MT (Ross 2008). Motivation for treatment may be understood in terms of the distinct dimensions of readiness and resistance, where readiness represents the level of interest in and commitment to substance use treatment, and resistance represents scepticism towards the potential benefits of treatment or opposition to engaging in treatment (Longshore 2006). The degree of readiness serves as a significant predictor of treatment retention, while the level of resistance predicts actual drug use (Longshore 2006). Promoting treatment retention as a means of enabling better overall outcomes therefore requires improving readiness for treatment and reducing resistance to treatment.

Music therapy for social engagement

MT provides a broad range of effects for people with SUDs, from neurobiological to social and cultural levels (Aldridge 2010). The social and interpersonal benefits of engaging in music provide communal experiences that offer opportunities for connection and expression, while also enabling coping, stress reduction, and re‐activation. MT in group settings enables participants to become aware of maladaptive coping and interpersonal patterns, to have these challenged within a supportive context, and to practice new ways of relating to their emotions and to other people (Dijkstra 2010). Participants who have difficulty forming relationships with others may find that MT offers a non‐verbal means of being with and relating to others. Expansion of positive social experiences through MT can be an essential factor in increasing motivation for continued treatment.

In summary, MT has a direct neurobiological impact on areas of the brain implicated in substance use, including emotion regulation and reward. MT also indirectly impacts substance use behaviour by supporting social engagement, improving coping skills, and increasing motivation for treatment. As a large number of people with SUD also have co‐occurring mental health disorders, the effects of MT for mental health disorders may have relevance in the context of substance use treatment. Active engagement in MT can alleviate anxiety and depression in people with serious mental health disorders (Geretsegger 2017), and those with depression, where it can also improve global functioning (Aalbers 2017). A reduction in depression and anxiety, and improvement in social, occupational, and psychological functioning may then improve adherence to treatment and enable better outcomes for substance users. By motivating engagement in treatment, facilitating development of therapeutic rapport, and musically approaching strong emotions as a means of expanding coping skills (Dijkstra 2010; Ghetti 2013) and attention span (van Alphen 2019), MT may promote readiness for treatment and reduce resistance, while also equipping people with emotional, interpersonal, cognitive, and musical skills that can help them positively manage their SUD.

Why it is important to do this review

MT is used as a non‐pharmacological psychotherapeutic intervention in a variety of multidisciplinary substance use treatment settings ranging from acute‐phase treatment for detoxification through community aftercare programmes for people with SUDs (Aldridge 2010; Silverman 2009). Individual studies demonstrate improvements in motivation to engage in treatment and reduction in psychological symptoms (Albornoz 2011; Silverman 2012). Previous systematic reviews of MT for SUDs are either out of date or did not include quantitative meta‐analysis of study outcomes (Carter 2020; Hohmann 2017; Mays 2008; Megranahan 2018; Silverman 2003). Due to the increasing volume of international research into MT for SUDs, and the need to establish an evidence base for practice and policy, a rigorous and comprehensive systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) specific to MT within multidisciplinary treatment is warranted.

Objectives

Main objective

To compare the effect of music therapy (MT) in addition to standard care versus standard care alone, or to standard care plus an active control intervention, on psychological symptoms, substance craving, motivation for treatment, and motivation to stay clean/sober.

Secondary objective

To assess the impact of the number of MT sessions on study outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs, including the first phase of cross‐over trials, and cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

People with problem substance use, with a formal diagnosis of SUD. Substances considered were illicit drugs, medication, and alcohol. We excluded nicotine addiction, due to the dissimilar impact on social and functional domains. We excluded non‐substance addiction (e.g. Internet addiction, gambling addiction). Diagnosis of SUD was based upon diagnostic criteria from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM‐IV‐TR; APA 2000) or DSM‐5 (APA 2013), and from the International Classification of Diseases 10th Version: Online 2019 (ICD‐10) (WHO 2019), codes F10 to F16 (mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use) (with the exclusion of caffeine (part of F15)), and F18 to F19 (mental and behavioural disorders due to use of volatile solvents or multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances). There were no restrictions by age or other participant characteristics, thus we included both adolescents and adults. Participants could have been dual‐diagnosed with mental health problems or learning problems. Participants could have received intervention in inpatient, outpatient, therapeutic community, or supportive aftercare settings.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Music therapy added to standard care

To be included, the intervention must have been labelled 'music therapy', and conducted by a qualified music therapist. MT involves a music therapist and one or more participants, engaging in specifically created music experiences to help them achieve their highest potentials of health (Bruscia 2014). MT interventions could have consisted of a variety of receptive or active approaches that use music to promote therapeutic change. Receptive approaches could have included listening to music as a basis for guided discussion and examination of feelings and thoughts or to impact mood, as well as other aims. Active approaches could have included opportunities for the participant to interact with music and music‐making processes through songwriting, singing, or playing instruments. We included both individual and group MT interventions. MT could have been offered as a part of multidisciplinary substance use treatment, and could have been practised from an integrated treatment orientation (e.g. cognitive behaviour therapy). MT could have been any length of session and course of treatment.

Control intervention

Standard care alone

Standard care represented treatment as usual, and included any conventional treatment (including pharmacotherapy) offered at the treatment setting as long as that treatment did not involve MT. Examples of services offered as part of standard care for SUDs include: psychotherapy, relapse prevention counselling, peer‐led groups including 12‐step programmes, case management, pharmacological detoxification, pharmacotherapy including methadone maintenance treatment, and recreational and sports activities. Wait‐list control occurred in conjunction with standard care, and consisted of participants assigned to a waiting list to receive MT after the active treatment group.

Active control intervention

Participants allocated to an active control intervention received a structurally equivalent condition that lasted the same duration as the MT intervention and controlled for non‐specific effects of the therapist's presence and attention, presence of the music, or presence of some other therapeutic element. Only participants assigned to the active control intervention received this particular intervention. An example of an active control intervention is verbal therapy that is provided in addition to standard care, and consists of discussion of themes related to motivation for change, relapse prevention, and managing substance use triggers. In this case, verbal therapy serves to control for the presence of the therapist and the discussion of treatment‐related themes, but it lacks a key proposed element of therapeutic change, namely musical engagement.

Types of comparisons

MT plus standard care versus standard care alone.

MT plus standard care versus standard care plus another active intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Outcomes could have been measured and reported either dichotomously or continuously. Data sources could have included both standardised and non‐standardised instruments. We included data from rating scales when they were from participant self‐report or rated by an independent evaluator (i.e. not the music therapist).

Primary outcomes

Psychological symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety, anger; e.g. measured by Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1996), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton 1960), state portion of the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), or visual analogue scales).

Substance craving (e.g. measured by Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS; Somoza 1995), or visual analogue scales).

Motivation for treatment/change (e.g. measured by Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RTCQ; Heather 1999), Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES; Miller 1996), University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (URICA; McConnaughy 1983), or visual analogue scales).

Motivation to stay sober/clean (e.g. measured by Commitment to Sobriety Scale (CSS; Kelly 2014), or visual analogue scales).

We collected outcomes reported immediately following completion of the intervention, short‐term follow‐up up to three months after completion of the intervention, and long‐term follow‐up at more than three months after completion of the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Alcohol or substance use, or both, in terms of amount, frequency, or peak use (as measured by self‐report, report by independent evaluators, urine analysis, or blood samples, as appropriate).

Retention in treatment (as measured by number of participants remaining in treatment at the end of the study).

Severity of substance dependence/use, as measured by validated scales (e.g. Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan 1992), Drinking Inventory Consequences (DrInC; NIAA 2003), or the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS; Gossop 1995)).

Serious adverse events (e.g. relapse requiring hospitalisation, suicide attempts, or suicide).

We measured serious adverse events as a binary variable related to the presence or absence of adverse events, including relapse requiring hospitalisation, suicide attempts, or suicide.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The electronic searches included the following databases:

the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group's Specialised Register of Trials (1 February 2021);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, Issue 1 2021);

MEDLINE (PubMed) (January 1966 to 1 February 2021);

Embase (embase.com) (January 1974 to 1 February 2021);

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1982 to 1 February 2021);

ERIC (eric.ed.gov) (1964 to 8 February 2021);

ISI Web of Science (1 February 2021);

PsycINFO (EBSCOhost) (1872 to 1 February 2021);

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) (1951 to 8 February 2021);

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (1997 to 8 February 2021);

Google Scholar (8 February 2021, first 100 hits).

We searched the following trials registries on 30 January 2021:

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov);

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

We imposed no restrictions by language, date, gender, age, or tag terms. See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Handsearching and reference searching

We handsearched the reference lists of all included studies. We also examined the reference lists of relevant review articles (e.g. Hohmann 2017; Mays 2008; Megranahan 2018; Silverman 2003).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

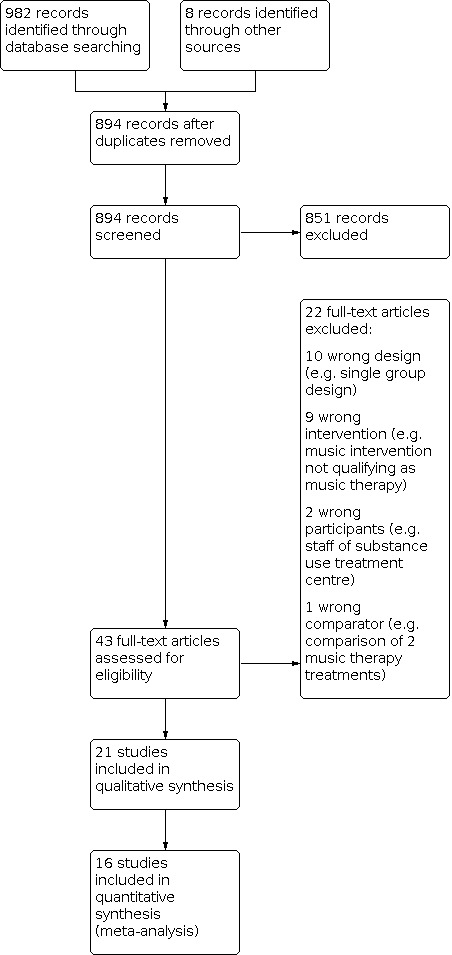

We used the Covidence software platform for citation screening, including merging search results and removing duplicates, and for full‐text review (Covidence). Two review authors and content area experts (XJC, CGh) independently examined each title and abstract to remove obviously irrelevant reports, and a third review author (LH or CGo) resolved disagreements. We then obtained full texts for all potentially relevant reports, and linked multiple reports of the same study, when applicable. Two review authors (XJC, CGh) independently examined each full‐text report to determine eligibility, and resolved disagreements in consultation with two other review authors (LH, CGo). We contacted study investigators when necessary, to clarify study eligibility. We illustrated the study selection process in a PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (XJC, CGh) independently performed data extraction using Covidence (Covidence), and exported data to Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2021). When necessary, we contacted study investigators to obtain missing data. We resolved disagreements in consultation with two review authors (LH, CGo), and archived their content and resolution. We extracted information from each study regarding:

methods (including design and aspects related to assessing risk of bias);

country and setting;

characteristics and number of participants;

characteristics of experimental and comparison groups, including the number of participants allocated to each, and length of MT in minutes/hours/sessions;

outcomes and time points;

results;

funding of the study;

conflict of interest of study authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (XJC, CGh) independently assessed risks of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011), in conjunction with the Covidence software platform (Covidence). We resolved disagreements by consulting two review authors (AB, CGo). The first part of the tool describes what was reported to have happened in the study, while the second part assigns a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry, as low, high, or unclear risk. We made such judgements using the criteria indicated by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), adapted to the addiction field. Appendix 2 includes a detailed description of the risk of bias criteria that we used. The eight domains include:

sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and providers (performance bias) (objective outcomes);

blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias);

blinding of participants and providers (performance bias) (subjective outcomes);

blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias) (subjective outcomes).

We considered blinding of participants and providers, and blinding of outcome assessors (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) separately for objective outcomes (e.g. alcohol or substance use, or both, as measured by urine analysis or blood samples; retention in treatment; serious adverse events) and subjective outcomes (e.g. psychological symptoms, substance craving, motivation for treatment/change, motivation to stay sober/clean, participant self‐report of substance use, participant self‐report of severity of substance dependence/use). We assessed incomplete outcome data for each outcome (avoidance of attrition bias), with the exception of 'retention in treatment'. We included all eligible studies, regardless of the level of the risks of bias, when presenting main findings for each outcome; however, we discussed the risks of bias and provide a cautious interpretation within the Discussion and Authors' conclusions sections of the review. We rated a study as being at a high risk of attrition bias when attrition was greater than 20%.

Measures of treatment effect

We assessed serious adverse events and retention in treatment at the end of treatment, while we measured efficacy measures at three different time points: immediately post‐intervention, short‐term follow‐up (up to three months after completion of the intervention), and long‐term follow‐up (more than three months after completion of the intervention).

Dichotomous data

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous data.

Continuous data

For continuous data from parallel‐group and cluster‐randomised RCTs, we selected the mean and standard deviation (SD) endpoint data for experimental and control groups. When outcomes were measured on the same scale or could be transferred to the same scale in all studies, we calculated the mean difference (MD) on the original metric. When studies used different scales to measure the same outcome, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) and corresponding 95% CI for continuous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over trials

When appropriate, we planned to combine results of cross‐over trials with those of parallel‐group trials, analysing data from the first phase only (i.e. before cross‐over) to avoid carry‐over effects.

Cluster‐randomised trials

When studies accounted for clustering in their analysis, inclusion of the data in meta‐analysis was straightforward. When clustering was not accounted for in an included study, we attempted to contact the study investigators to obtain the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of their clustered data. When we could not obtain the ICC, we used external estimates from similar studies (Higgins 2011). If no such estimates were available, we assumed ICC = 0.05; this is likely to lead to conservative estimates as lower values than that are typical (Higgins 2011, Section 16.3.4).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

When studies had more than one relevant MT intervention, we planned to combine all such experimental groups into a single group, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We followed intention‐to‐treat principles and included all known data from all randomised participants. We used the following sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of missing data. For continuous outcomes, we planned to remove studies with high attrition (more than 20%). For dichotomous outcomes, we assumed that the unobserved cases had a negative outcome. We reported on the potential impact of missing data when assessing risks of bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If the number of included studies is low or studies have small sample size, or both, statistical tests for heterogeneity may have low power and be difficult to interpret (Higgins 2011). We conducted descriptive analyses of heterogeneity by visually examining forest plots for consistency of results and by calculating the I2 statistic, which represents the percentage of effect estimate variability that is due to heterogeneity instead of sampling error (Higgins 2011). We planned to supplement the I2 statistic with a calculation of the Chi2 statistic to assess the likelihood that the heterogeneity was genuine, and to consider possible sources of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to test for asymmetry of funnel plots when there were at least 10 studies in a meta‐analysis, and to explore likely reasons for asymmetry when it was present. However, none of our meta‐analyses contained a sufficient number of studies to warrant assessment of asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We combined the outcomes from the individual trials through meta‐analysis where possible (comparability of intervention and outcomes between trials), using a random‐effects model, because we expected a certain degree of heterogeneity among trials. In cases where meta‐analysis was not appropriate, we reported results for each individual study.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity in the included studies was interpreted in accordance with the approximate guide for interpretation of the I2 statistic provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Section 9.5.2; Higgins 2011). Heterogeneity of 0% to 40% was considered to most likely not be important, 30% to 60% was considered moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity.

When there was significant heterogeneity, we planned to use subgroup analyses to examine the impact of the number of sessions, type of substance, and presence of dual‐diagnosis (i.e. SUD and mental disorder). For subgroup analysis of the number of sessions, we planned to use the following cut‐off points for respective subgroups: three sessions or more versus one or two sessions for outcomes that might show an effect of short intervention, such as are found in detoxification settings (i.e. retention in treatment, reduction in psychological symptoms, improvement in motivation for treatment/change, substance craving); and 10 or more sessions versus fewer than 10 sessions for outcomes typically requiring longer‐term treatment, such as those within rehabilitation settings (i.e. reduction in substance use, severity of substance dependence/use, cessation of substance use, serious adverse events).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis of the review outcomes, removing trials with high attrition rates (i.e. studies with attrition rates higher than 20%), as unequal attrition from studies may indicate unsatisfactory or intolerable treatment.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Grading of the evidence

We assessed the overall certainty of the evidence for the primary outcome using the GRADE system. The GRADE Working Group developed a system for grading the certainty of evidence, which takes into account issues related both to internal and external validity, such as directness, consistency, imprecision of results, and publication bias (Atkins 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011).

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

high: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect;

moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different;

low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect;

very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Grading is decreased for the following reasons:

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) study limitation for risk of bias;

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) inconsistency between study results;

some (–1) or major (–2) uncertainty about directness (the correspondence between the population, the intervention, or the outcomes measured in the studies actually found and those under consideration in our systematic review);

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) imprecision of the pooled estimate;

publication bias strongly suspected (–1).

Summary of findings table

We included summary of findings tables to present the main findings of the review in a transparent and simple tabular format. The summary of findings tables include:

main findings from the primary outcomes: psychological symptoms, substance craving, motivation for treatment/change, motivation to stay sober/clean; and findings from outcomes that might reflect undesirable effects: retention in treatment, and serious adverse events;

a measure of the typical burden of these outcomes (e.g. illustrative comparative risk);

absolute and relative magnitude of effect;

number of participants and studies addressing these outcomes;

a rating of the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome;

space for comments.

We used GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro) to assist in the preparation of the summary of findings tables (GRADEpro GDT).

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Results of the search

Electronic searches of the 11 databases (see Electronic searches) retrieved 982 records. We identified two additional studies that met inclusion criteria by handsearching systematic reviews and contacting authors. Our searches of the trials registers identified six eligible records. Our screening of the reference lists of the included publications did not reveal additional RCTs. Therefore, we had 990 records.

Once duplicates had been removed, we had 894 records. We excluded 851 records based on titles and abstracts. We obtained the full text of the remaining 43 records. We excluded 22 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We identified no studies awaiting classification or ongoing studies.

We included 21 studies reported in 23 references in the qualitative synthesis, and 16 of those in quantitative synthesis (meta‐analysis). For a further description of our screening process, see the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

Included studies

We included 21 studies (1984 participants), all of which used a parallel design and offered MT in addition to standard care. Fifteen studies were cluster‐RCTs (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021). Eleven studies had two arms and compared MT plus standard care to standard care alone (Albornoz 2009; Heiderscheit 2005; James 1988; Murphy 2008; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021; Wu 2020), or to an active control intervention (i.e. verbal therapy) (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a). Five studies had three arms, either comparing MT plus standard care to another active intervention plus standard care and to standard care alone (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2017), or comparing MT plus standard care to two active interventions plus standard care (Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2019a). One study had four arms comparing two MT interventions to two active control interventions (Silverman 2016a).

Full description of the included studies is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table, and a summary of study characteristics is described below.

Participants

Participants in all included studies met criteria for diagnosis of SUD. Studies confirmed diagnosis according to DSM‐IV or ICD‐10 criteria in the study report. In cases where such information was lacking, study investigators confirmed diagnosis via email (Albornoz 2009; Heiderscheit 2005; Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2017). In addition to SUD, participants in Albornoz 2009 were diagnosed with comorbid depression, and in Heiderscheit 2005 most had comorbid mental health diagnoses.

The participants' substances of choice were varied, including alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and prescription drugs. Fourteen studies reported on substance of choice with weighted means across the studies of 51.6% alcohol, 30.1% heroin, 14.7% prescription tablets, 1.6% cocaine/crack, and 10.8% other drugs (Heiderscheit 2005; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021; Wu 2020).

Ages of participants were heterogeneous across studies but mainly included adults older than 18 years. One study included adolescents only (James 1988), while a second included both adolescents and adults with an age range of 16 to 60 years (Albornoz 2009). In the studies including adults only, weighted mean age across studies was 38.8 years with mean ages ranging from 34.9 years (Silverman 2020) to 55.9 years (Heiderscheit 2005).

Two studies recruited only males (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020), and one study recruited only females (Wu 2020). The rest of the studies included both males and females. Weighted mean percentage of males across studies including both men and women was 55%, with studies ranging from 43.9% (Silverman 2009) to 78.9% (Heiderscheit 2005).

Two studies reported number of years of substance use: Heiderscheit 2005 reported a range of substance use from one year to 44 years and mean 20.8 (SD 10.9) years, and Wu 2020 reported mean 5.41 (SD 2.1) years. Fifteen studies reported the number of times that participants were admitted to a rehabilitation/detoxification facility ranging from once to nine times (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021).

All studies with the exception of four (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; James 1988; Wu 2020) reported on race of participants. Across studies reporting participant race, all of which took place in the USA, a weighted mean of 82.7% of participants identified as Caucasian (assumed to be white people), 5.1% African American, 5% Native American, and 8.7% other race. Two studies documented level of education: Heiderscheit 2005 reported 89% of participants held at least a high school degree, and Wu 2020 reported mean 10 (SD 1.6) years of education.

Setting

Fifteen studies occurred in a short‐term inpatient detoxification setting (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021), two in a residential substance use treatment facility (Murphy 2008; Wu 2020), one in a chemical dependency treatment programme within a residential health facility (Heiderscheit 2005), and two in facilities offering inpatient and outpatient substance use treatment (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020). One study took place in China (Wu 2020), one in Iran (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020), and one in Venezuela (Albornoz 2009), with the remaining studies taking place in the USA.

Sample size

There were 1984 participants in the 21 included studies. Sample size in individual studies ranged from 19 (Heiderscheit 2005) to 144 (Silverman 2016b). In the analyses, we reduced the effective sample size of three cluster‐RCTs where there was no adjustment for clustering (Silverman 2009 – 16 clusters; Silverman 2011a – 28 clusters; Silverman 2011b – 27 clusters) using an imputed ICC (as described in Unit of analysis issues).

Duration and frequency of intervention

There were two populations of studies in the review, those with interventions spanning from one week (James 1988) to 13 weeks (Wu 2020), and those consisting of a single session. Within the first category, studies offered MT either once per week (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Heiderscheit 2005; Wu 2020), approximately twice per week (Murphy 2008), or four times per week (James 1988). The remaining 15 studies were single‐session interventions (all studies by Silverman). The five studies with duration of MT longer than three weeks had MT session lengths of approximately 60 (Murphy 2008), 90 (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Heiderscheit 2005; Wu 2020), and 120 minutes (Albornoz 2009). The single‐session studies had MT session length of approximately 45 minutes (all studies by Silverman).

Interventions

We included the following comparisons: MT plus standard care versus standard care alone (including wait‐list control) and MT plus standard care versus active control intervention plus standard care.

Music therapy

MT interventions that were included in our analyses were labelled as "music therapy," were conducted by a trained music therapist, and were consistent with the definition of MT provided in our inclusion criteria. MT methods varied across the included studies. Eleven studies used lyric analysis, which consisted of singing through or listening to a particular song and discussing lyrics in relation to a chosen substance use‐related theme (e.g. promoting motivation for change or relapse prevention, or both) and most often with a cognitive‐behavioural psychotherapeutic orientation (James 1988; Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2021; Wu 2020). Seven studies used a semi‐structured songwriting process with themes related to identifying motivators for change, addressing substance use triggers, identifying coping skills and developing strategies to promote change and abstinence (Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020). Two studies used a highly specialised psychodynamically oriented receptive approach known as Guided Imagery and Music (GIM), in which participants listen to programmes of therapist‐selected classical music and engage in free associated imagery to work through unconscious material (Heiderscheit 2005; Murphy 2008). The therapist brings images to participants' awareness and guides participants to explore, deal with, and solve specific unconscious issues. Three studies used improvisational MT consisting of instrumental improvisation followed by processing of emotions and thoughts verbally or through other expressive means (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Wu 2020). Two studies used combinations of the aforementioned methods (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Wu 2020), where singing, instrument playing and analysis of music lyrics or poems was used as a means for emotional expression and paired with verbal processing.

All studies offered MT within a group of two to 10 participants. One study included a reflective homework assignment with the aim of encouraging participants to continue contemplating the topics addressed during MT after conclusion of the session (Silverman 2011b).

Comparator interventions

Comparator interventions consisted of either standard care or an active control.

Standard care

All studies offered MT in addition to standard care. Standard care consisted of an array of standard services within the substance use treatment programme including individual or group (or both) psychotherapy, peer‐led groups including 12‐step programmes, pharmacotherapy, recreational and sports activities, medical care, and social work services. Fourteen studies compared MT plus standard care to standard care alone (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Heiderscheit 2005; James 1988; Murphy 2008; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021; Wu 2020).

Verbal therapy

Eight studies used verbal therapy as an active control (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2016a). One study used a two‐month course of group cognitive behaviour therapy as a comparative intervention (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020), verbal therapy consisted of identifying goals, discussing triggers and craving, evaluating coping strategies, practising health decision‐making, and learning problem‐solving skills. In the remaining seven studies, all of which had single‐session interventions, verbal therapy consisted of non‐music, scripted verbal therapy group focused on themes such as relapse prevention, motivation for change, drug avoidance self‐efficacy, and discussion of triggers and coping skills. In these seven Silverman studies, themes used in verbal therapy corresponded with content offered during the course of the MT intervention within the same study. Thus, in the Silverman studies, verbal therapy served as a non‐musical equivalent of the MT intervention (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2016a).

Recreational music

Five studies used recreational music as an active control (Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a). In these studies, recreational music consisted of a "Rock and Roll" music bingo game with accompanying discussion of musical artists, songs, and memories; it did not include a focus on issues specifically related to substance use. As such, the recreational music groups controlled for the non‐specific effects of therapist attention and for the presence of music, but lacked the therapeutic mechanism thought to be necessary to enable change in substance use behaviour. A music therapist, who was also the primary researcher, conducted recreational music groups.

Thus, 10 studies compared MT plus standard care to another active intervention plus standard care; either verbal therapy (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2016a), or recreational music (Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Psychological symptoms (depression)

Depression symptoms were assessed using various standardised and non‐standardised scales.

The BDI is a self‐report measure of depression consisting of 21 items with total scores ranging from 0 to 63, and higher scores indicating more severe depression (Beck 1996). Three studies used the BDI (Albornoz 2009; Murphy 2008; Silverman 2011a), one of which also used the HRSD (Albornoz 2009).

The HRSD is a clinician‐rated scale to assess depressive symptoms, consisting of either 17 or 21 items (scoring is based on the first 17), with total scores ranging from 0 to 54 and higher scores indicating more severe depression (Hamilton 1960). Albornoz 2009 used the 17‐item version of the HRSD.

The SDS is a self‐report measure of depression consisting of 20 items with total scores ranging from 20 to 80, and higher scores indicating more severe depression (Zung 1965). One study used the SDS (Wu 2020).

One study used the Likert scale self‐report measurement of depression (Silverman 2011a), which is a 7‐point scale with higher scores indicating more severe depression.

Psychological symptoms (anxiety)

Anxiety was measured by a standardised scale.

Substance craving

Substance craving was measured by three standardised scales. Lower scores on each of the standardised scales were indicative of lower levels of substance craving.

The BSCS is a 16‐item self‐report scale that measures level of craving for substances over the previous 24 hours, with lower scores indicating less substance craving (Somoza 1995). The BSCS evaluates the intensity, frequency, and duration of substance craving, and has a score ranging from 0 to 12. The BSCS includes two separate craving scales, so that respondents can complete separate forms to rate cravings for two different substances. When data were available from more than one scale (Silverman 2011b), we included only the first scale since not all participants had completed a second scale. Two studies used the BSCS and asked participants to evaluate current level of substance craving (Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2016b).

The Alcohol Craving Questionnaire‐Short Form Revised (ACQ‐SF‐R) is a 12‐item self‐report scale that assesses current craving for alcohol, with lower scores indicating less intense craving (Singleton 2003). One study used the ACQ‐SF‐R (Silverman 2017), and substituted "drug use" in place of "drinking" within the form, in order to accommodate diversity of problematic substance use among participants.

The Obsessive Compulsive Drug Use Scale (OCDUS) is a 13‐item self‐report scale that assesses level of craving drugs in the past weeks, lower scores indicate less intense craving (Franken 2002). One study used the OCDUS (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020).

Motivation for treatment/change

Motivation for treatment/change was measured by six standardised self‐report scales. High scores on all scales were indicative of better motivation for treatment/change.

The Texas Christian University Treatment Motivation Scale – Client Evaluation of Self at Intake (CESI) is a 29‐item self‐report scale with 5‐point Likert scales for each item and higher scores indicating greater motivation for change (Simpson 2008). The CESI is composed of four subscales: problem recognition, desire for help, treatment readiness, and pressures for treatment; the four subscales can be added for a total motivation score. One study used the CESI, where we used the total motivation score (Silverman 2015b).

The CMR is an 18‐item self‐report scale (DeLeon 1993). Each item is rated on a 5‐point Likert scale (from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree"; negatively worded items are reversed in the scoring, so that higher scores indicate greater motivation. The items are summed into four subscales reflecting different aspects of motivation. One study used the CMR, which reported data for subscales only (Silverman 2012). For the purpose of this review, we selected the two subscales most closely related to our included outcome "motivation for treatment/change," namely the "Motivation (internal recognition of the need to change)" and "Readiness (readiness for treatment)" subscales, and we calculated a mean effect size across the two.

The Importance, Confidence, Readiness Ruler (ICR) consists of three 10‐point Likert scales that measure overall motivation to change (including readiness to change), and total scores range from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating higher motivation for change (Miller 2002). The ICR may be completed in an interview or self‐completion format. One included study used the ICR, and we used the total score (Murphy 2008).

The Readiness to Change Questionnaire – Treatment Version (RTCQ‐TV) consists of a 15‐item self‐report scale to assess level of motivation and readiness to stop or control drinking (Heather 1999). The scale contains subscales aligning with Prochaska and DiClemente's stages of change model (Prochaska 1983), namely, Precontemplation, Contemplation and Action stages. One included study used the RTCQ‐TV, and reported data for subscales only (Silverman 2011b). For the purpose of this review, we selected the two subscales most closely related to our included outcome "motivation for treatment/change," namely the "Contemplation" and "Action" subscales, and we calculated a mean effect size across the two subscales.

The SOCRATES is a 19‐item self‐report scale that assesses motivation for change, treatment eagerness, and readiness to change (Miller 1996). A total score can be computed and ranges from 19 (low) to 95 (high), with higher scores indicating greater motivation to change. The SOCRATES has versions for alcohol and for drug use. Two included studies used the SOCRATES, one providing total scores (Silverman 2009), and the other providing scores for subscales of Recognition and Taking Steps, which we combined to calculate a mean effect size across the two subscales (Silverman 2021).

The University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) is a 32‐item self‐report scale that assesses motivation for change (McConnaughy 1983). The URICA has four subscales aligning with Prochaska and DiClemente's stages of change model (Prochaska 1983), namely, Precontemplation, Contemplation, Action, and Maintenance. The subscales can be combined arithmetically (Contemplation + Action + Maintenance – Precontemplation) to yield a Readiness to Change score, with higher scores indicating greater readiness for change. Each subscale consists of eight items using 5‐point Likert scales ranging from 1 to 5 (resulting in scores ranging from 8 to 40). Subscale scores can be used to trace changes in attitudes related to the specific stages of change. One included study used the URICA, and reported data for subscales only (Silverman 2011a). For the purpose of this review, we selected the two subscales most closely related to our included outcome "motivation for treatment/change," namely the "Contemplation" and "Action" subscales, and we calculated a mean effect size across the two.

Total scores were available for CESI, ICR, and SOCRATES. In the other scales, we combined the subscales that were most closely related to the constructs of motivation and action (e.g. Contemplation and Action scales of RTCQ‐TV and URICA; Motivation and Readiness in the CMR) by calculating mean effect size.

In addition to standardised scales, two studies used self‐report Likert scales for motivation for treatment/change, both of which used a 7‐point scale with higher scores indicating greater motivation for treatment (Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a).

Motivation to stay sober/clean

Motivation to stay sober/clean was measured by two standardised scales and by Likert scale.

The CSS is a 5‐item self‐report scale that measures degree of motivation to cessation and abstinence from drug or alcohol use (Kelly 2014). Total scores range from 5 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater commitment to abstinence. One study used the CSS (Silverman 2021).

The Questionnaire of Motivation for Abstaining from Drugs (QMAD) is a 36‐item self‐report measure of motivation for abstaining from drugs (Wu 2008). Total scores range from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating greater motivation. One study used the QMAD (Wu 2020).

Three studies used a 7‐point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater motivation to stay sober/clean (Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a).

Given that participants had assumedly entered substance use treatment in order to change problematic substance use behaviour, in this review 'motivation to stay sober/clean' is considered to be a specific manifestation of the construct 'motivation to change,' and therefore warrants both inclusion as an outcome and separate analysis.

Secondary outcomes

Alcohol or substance use

One study assessed substance use during a follow‐up telephone call at one month after discharge from substance use treatment by asking participants if they had maintained sobriety (Silverman 2011a). Respondents could reply: yes, somewhat, or no. We scored this outcome as a dichotomous variable with the responses 'somewhat' and 'no' scored as 'no'.

Retention in treatment

The review authors calculated retention in treatment for six studies based on the number of participants remaining at the end of treatment (Albornoz 2009; Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; Heiderscheit 2005; James 1988; Murphy 2008; Wu 2020). The remaining included studies used single‐session interventions, and thus, it was not possible to calculate this outcome for those studies. Retention in treatment was defined as the number of participants remaining in each group at the end of treatment.

Severity of substance dependence/use

None of the included studies examined severity of substance dependence/use.

Serious adverse events

None of the included studies reported data on serious adverse events.

Excluded studies

We excluded 22 studies. Ten studies required full‐text review to confirm that they were not RCTs or controlled clinical trials (Baker 2007; Bibb 2018; Dingle 2008; Gardstrom 2013; Howard 1997; Moe 2011; Murphy 2015; Oklan 2014; Taylor 2005; Wheeler 1985). Nine studies did not use MT as the intervention, either using music but not qualifying as MT (Chandrasekar 2020; Gallant 1997; Lu 2005; Mathis 2017; Sewak 2018; Stamou 2016; Stamou 2017), using combination of therapies (Malcolm 2002), or not having music intervention (Haddock 2003). Two studies included an ineligible population, such as a mix of patients and staff (Hammer 1996), or mental health patients without diagnosis of SUD (Silverman 2016c). One study did not include a relevant control intervention (Jones 2005).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the assessment of risk of bias are represented in the risk of bias section of the Characteristics of included studies tables, in Figure 2, and in Figure 3.

2.

Review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Objective outcome was only assessed in six of the included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation was achieved in individually randomised studies, via use of random number blocks (Albornoz 2009), coin toss (Heiderscheit 2005), computer program (Murphy 2008), or an independent statistician not directly involved with the research (Wu 2020). We judged these four studies at low risk of bias. Two individually randomised studies did not specify method of sequence generation (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; James 1988), and these studies were judged at unclear risk of selection bias. Of 15 cluster‐randomised trials, four specified that the randomisation sequence was generated with a computer (Silverman 2014; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2021); in the remaining 11 cluster‐randomised trials this was unclear. We judged the four studies at low risk of bias, and the remaining 11 studies at unclear risk of bias (Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020).

Allocation concealment

One study used sequentially numbered envelopes, so that participants and investigators involved could not have foreseen treatment assignment (Albornoz 2009). One study used coin toss for randomisation, which does not assure adequate concealment of allocation, and thus was judged at unclear risk of selection bias (Heiderscheit 2005). In the remaining 19 studies, information about allocation was either insufficient or not further specified (Eshaghi Farahmand 2020; James 1988; Murphy 2008; Silverman 2009; Silverman 2010; Silverman 2011a; Silverman 2011b; Silverman 2012; Silverman 2014; Silverman 2015a; Silverman 2015b; Silverman 2016a; Silverman 2016b; Silverman 2017; Silverman 2019a; Silverman 2019b; Silverman 2020; Silverman 2021; Wu 2020). Therefore, we judged them to be at unclear risk of bias.

Blinding