Abstract

Active biological containment systems are based on the controlled expression of killing genes. These systems are of interest for the Pseudomonadaceae because of the potential applications of these microbes as bioremediation agents and biopesticides. The physiological effects that lead to cell death upon the induction of expression of two different heterologous killing genes in nonpathogenic Pseudomonas putida KT2440 derivatives have been analyzed. P. putida CMC4 and CMC12 carry in their chromosomes a fusion of the PA1-04/03 promoter to the Escherichia coli gef gene and the φX174 lysis gene E, respectively. Expression of the killing genes is controlled by the LacI protein, whose expression is initiated from the XylS-dependent Pm promoter. Under induced conditions, killing of P. putida CMC12 cells mediated by φX174 lysis protein E was faster than that observed for P. putida CMC4, for which the Gef protein was the killing agent. In both cases, cell death occurred as a result of impaired respiration, altered membrane permeability, and the release of some cytoplasmic contents to the extracellular medium.

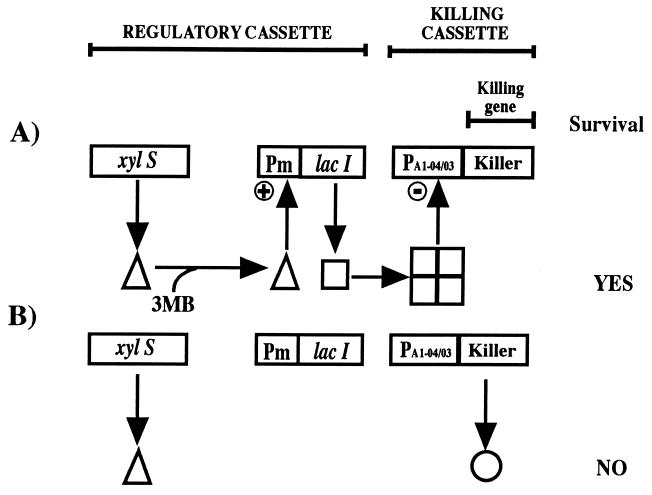

Active biological containment (ABC) systems have been envisaged as a way to control the survival of genetically modified microorganisms and the putative consequences of their introduction into the environment (Fig. 1) (for reviews, see references 20 and 26). ABC systems are based on the use of genes that encode killing proteins regulated by a control element that activates (or derepresses) the killing function under defined environmental conditions (1, 21).

FIG. 1.

Detail of the biological containment system for alkylbenzoates. This model consisted of the Pm promoter, which drives the transcription of the meta-cleavage pathway of the TOL plasmid, and the xylS gene, which encodes the sensor protein that interacts with alkylbenzoates and stimulates transcription from Pm. In the containment system, the lacI gene, coding for the LacI repressor protein, was cloned downstream from Pm. The lethal element consisted of the PA1-04/03 promoter fused to the gef gene of E. coli or φX174 gene E, each of which codes for pore-forming proteins. The system was shown to perform as follows. In the presence of 3-methylbenzoate, the XylS protein became active and stimulated the synthesis of the LacI protein, which in turn prevented the expression of the killing gene; concomitantly, degradation of the alkylaromatic compound took place. Once the compound was exhausted, the XylS protein became inactive, the LacI protein was not made any longer, and expression from PA1-04/03 led to the synthesis of Gef or E protein, which in turn collapsed the cell membrane potential and led to the death of the cell.

The development of ABC systems for the Pseudomonadaceae is of interest because of the potential applications of these microbes under field conditions. The so-called fluorescent Pseudomonas group includes strains whose biochemical, physiological, and genetic properties have been well characterized (7, 27, 35). A number of genetic tools have made it possible to design recombinant derivatives of this group of bacteria for the biological control of pests (4, 24), the promotion of plant growth (13, 17, 18), and the detoxification of polluted sites (8, 27, 35).

Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is a DNA restriction-modification system-negative strain derived from the soil bacterium P. putida mt-2, the natural host for the archetypal TOL plasmid pWW0 (39). Strain KT2440 has been shown to be a nonaggressive soil rhizosphere colonizer (22, 25, 28). In addition, this strain stably maintains and expresses heterologous genes, including catabolic segments for the expansion of its metabolic versatility and killing genes of interest for biological containment (5, 21, 26–28). The genes encoding killing functions successfully used in P. putida were those that encode lysis proteins (1, 11, 14, 30), nucleases (3), and streptavidin (34). In previous studies, we demonstrated that the regulatory gene expression system of the TOL plasmid meta-pathway for the metabolism of alkylbenzoates could be combined with the gef gene of Escherichia coli, which encodes a porin-like protein, in such a way that cell killing became a consequence of the absence of the substrate (and inducer) 3-methylbenzoate both under laboratory conditions (1, 11, 30, 31) and in soil microcosms (11, 30). We also showed that a P. putida strain carrying an ABC system on the host chromosome functioned as expected under field conditions (23). A modified version of this system based on lysis gene E of bacteriophage φX174 has also been constructed (30). However, the above studies have not dealt in detail with the physiological phenomena that lead to cell death in P. putida upon induction of the expression of killing genes in this heterologous host. In E. coli, the natural host for φX174 phage protein E-mediated cell lysis, killing occurs as the consequence of the formation of a transmembrane tunnel made of E protein; the tunnel fuses the outer and inner membranes and allows the escape of cytoplasmic material (36–38). In E. coli, the Gef protein forms dimers that are anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane and lead to the collapse of the cell membrane potential (reviewed in reference 20).

In this study, we show that once the Gef protein or the φX174 E protein is expressed in P. putida, cell death occurs as a consequence of the formation of membrane holes, which impair respiration, alter membrane permeability, and release cell material.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The P. putida strains used or constructed in this study are derivatives of P. putida KT2440 (6). Their relevant characteristics are given in Table 1. P. putida EEZ29 (31), CMC4 (23), and EEZ15K-3 (29) were described before; these three strains bear the archetypal TOL plasmid pWW0, which confers on them the ability to grow on 3-methylbenzoate. Strains that were constructed in the course of this study are described below. P. putida strains were grown with shaking at 30°C in modified M9 minimal medium (1) with 28 mM glucose or 5 to 15 mM 3-methylbenzoate as the sole carbon source.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| Mv1190λpir | F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacZΔM15 lacIq) thi Δ(lac-proAB) Tn10λpir | 9 |

| JM109 | F′ (traD36 proAB+ lacZΔM15 lacIq) thi Δ(lac-proAB) recA1 gyrA96 | 19 |

| Pseudomonas putida | ||

| CMC4 | (pWW0) Kmr 3MB+ mini-Tn5-Km (xylS Pm::lacI PA1-04/03::gef) | 23 |

| CMC12 | (pWW0) Kmr Telr 3MB+ EEZ29::mini-Tn5-Tel (PA1-04/03::gene E) | This study |

| CMC13 | (pWW0) Telr Kmr 3MB+ EEZ29::mini-Tn5-Tel | This study |

| EEZ15K-3 | (pWW0) Kmr 3MB+ mini-Tn5-Km | 29 |

| EEZ29 | (pWW0) pCC102 Kmr 3MB+ | 31 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCC102 | KmrxylS2 Pm::lacI | 1 |

| pJMSB4 | Apr Telr mini-Tn5-Tel R6K oriV mob+ | 33 |

| pMCC26 | pUHE24-1 derivative; Apr Cms | This study |

| pMCC27 | Apr PA1-04/03::gene E | This study |

| pMCC30 | Apr PA1-04/03::gene E fragment of pMCC27 inserted between SalI and HindIII sites of pUC18Not | This study |

| pMCC31 | Apr Telr mini-Tn5 PA1-04/03::gene E R6K oriV mob+ | This study |

| pRK600 | Cmr ColE1 oriV RK2 mob+ tra+ | 12 |

| pUC18Not | Apr | 2, 9 |

| pUHE24-1 | Apr Cmr ColE1 oriV | 16 |

| pWW0 | IncP9 mob+ tra+ 3MB+ | 39 |

Kmr, Apr, Cmr, and Telr indicate resistance to kanamycin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and potassium tellurite, respectively; Cms indicates sensitivity to chloramphenicol; 3MB+ indicates the ability to grow on 3-methylbenzoate. PA1-04/03 is a synthetic lactose promoter (16).

In cloning experiments, E. coli Mv1190λpir was used to replicate the pMCC plasmids (Table 1). These plasmids are based on the R6K plasmid origin of replication, which is not recognized in P. putida strains, and behaves as a suicide replicon. E. coli JM109 was used to maintain other plasmids or in cloning experiments with vectors that did not require the Pir protein for replication. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in LB medium (19). The plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1.

Antibiotics were used at the following final concentrations (micrograms per milliliter): ampicillin, 100; chloramphenicol, 30; and kanamycin, 50. Potassium tellurite was used at 5 to 30 μg per ml.

Construction of the killing cassette bearing the PA1-04/03::gene E fusion.

Plasmid pUHE24-1 was described before (16). It carries ampicillin and chloramphenicol resistance and exhibits two NcoI sites. One of them lies 3′ with respect to the synthetic isopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter PA1-04/03, and the other lies at the chloramphenicol resistance gene. To ensure that the plasmid contained only the NcoI site 3′ with respect to the synthetic PA1-04/03 promoter, the plasmid was partially digested with NcoI and treated with the Klenow enzyme and the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates to fill in the sticky NcoI ends. Apr clones were selected after ligation and transformation. A Cms clone was selected, and the plasmid that it bore was called pMCC26. We confirmed that the single NcoI site remaining in this plasmid was located 3′ with respect to the synthetic PA1-04/03 promoter.

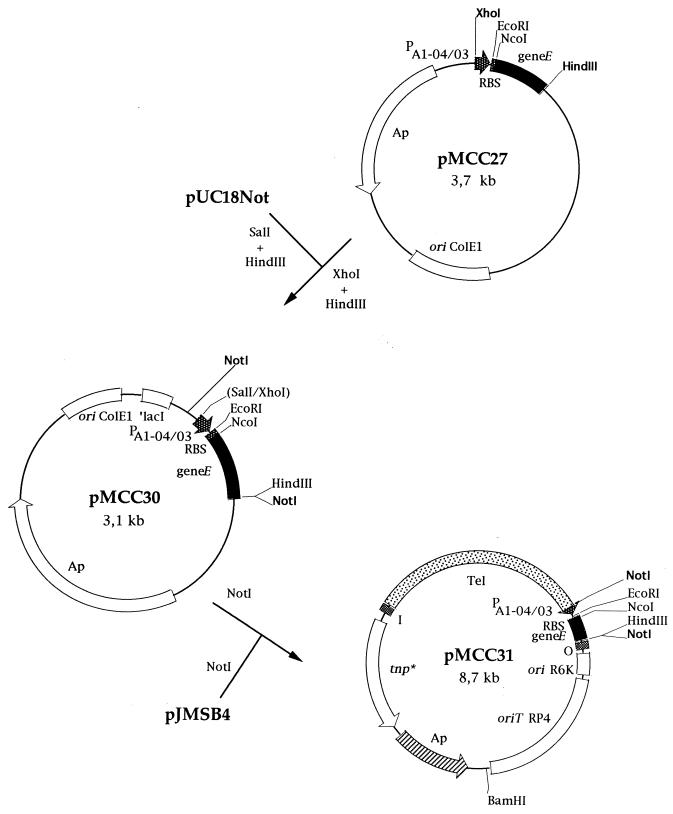

φX174 gene E was amplified by the PCR method with phage DNA as a template. The oligonucleotides used for amplification (5′-GTTTCTGGCCATGGTACGCTGGACTTTGTG-3′ and 5′-TCATTATCTTAAGCTTACGTTTTTTACCTTTAGA-3′) were partly complementary to the ends of gene E and were designed so that NcoI and HindIII sites would be generated near the ends of the amplified DNA fragment. The amplified gene E DNA was cleaved with NcoI and HindIII and cloned into pMCC26 cut with NcoI and HindIII, so that the amplified promoterless φX174 gene E was read from the synthetic PA1-04/03 promoter. The resulting plasmid was called pMCC27 (Fig. 2). A 418-bp region from pMCC27 containing the PA1-04/03::gene E fusion was isolated after digestion with XhoI and HindIII and cloned in pUC18Not digested with SalI and HindIII. The resulting plasmid, pMCC30, was selected after transformation of the ligation mixture into E. coli JM109 (Fig. 2). Plasmid pMCC30 was digested with NotI, and a 430-bp fragment containing the PA1-04/03::gene E fusion was cloned into the unique NotI site of pJMSB4 and transformed into E. coli Mv1190λpir. The resulting plasmid carried a PA1-04/03::gene E fusion and the tellurite-resistant determinant within mini-Tn5. This plasmid was called pMCC31 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Construction of a Tn5-based insertion delivery plasmid containing an inducible cell lysis system based on lysis gene E from bacteriophage φX174. Restriction sites relevant for the constructions are shown. Plasmid pUC18Not and the pUT-based plasmid pJMSB4 have been described elsewhere (9, 33). Abbreviations: geneE, lysis gene E of bacteriophage φX174; RBS, ribosome binding site from the E. coli expression plasmid pUHE24-1 (16); PA1-04/03, synthetic lactose promoter from plasmid pUHE24-1; ori, origin of replication; ori R6K, origin of replication dependent on the Pir protein; ori ColE1, origin of replication from plasmid ColE1; oriT RP4, origin of transfer; tnp*, transposase; ′lacI, gene encoding the repressor protein for the lac operon.

Triparental matings.

Triparental matings were performed as described by Herrero et al. (9). Equal numbers (about 108 cells) of the recipient strain P. putida EEZ29, the donor strain E. coli Mv1190λpir(pMCC31) or E. coli Mv1190λpir(pJMSB4), and the helper strain E. coli HB101(pRK600) were mixed and deposited on a nitrocellulose filter placed on the surface of an LB medium plate supplemented with 5 mM 3-methylbenzoate. Appropriate controls with unmixed cells, otherwise treated identically to the mixture, were always included. P. putida transconjugants were selected on M9 minimal medium plates containing kanamycin and tellurite and supplemented with 3-methylbenzoate as the sole carbon source. One random transconjugant of P. putida EEZ29 that had received the minitransposon mini-Tn5-Tel from pJSB4 was selected and called CMC13; another random transconjugant that had received mini-Tn5-Tel PA1-04/03::gene E from pCMC31 was selected and called CMC12.

Tests of killing efficiency.

Killing efficiency was tested with liquid medium. Bacteria were grown in M9 minimal medium containing glucose and 3-methylbenzoate and supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. Cells in the early exponential phase were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 15 min), washed twice in M9 minimal medium without a C source, and resuspended in M9 minimal medium with glucose. The sample was divided in half. To one half, 5 mM 3-methylbenzoate was added; 1 mM IPTG was added to the other half. All samples were then incubated at 30°C with shaking. For determination of viable counts, triplicate samples from a series of dilutions of the cultures were plated on LB medium plates containing 5 mM 3-methylbenzoate and the appropriate antibiotics.

Transmission electron microscopy.

P. putida cells were harvested by centrifugation, immediately fixed with 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde–1% (vol/vol) formaldehyde in cacodylate buffer, postfixed with osmium tetroxide in the presence of 2% (wt/vol) potassium ferrocyanide, and embedded in Eponate 12. Thin sections were poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined in a Zeiss transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

High-resolution scanning electron microscopy.

Scanning electron micrographs were taken with a Hitachi S-800 field-emission scanning electron microscope. The cells were fixed and prepared for electron microscopy essentially as described previously (38).

Protein analysis.

Proteins in culture supernatants of P. putida were analyzed as follows. Whole cells were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was concentrated by precipitation with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Cells were then resuspended in Laemmli buffer and analyzed by electrophoresis on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels with the discontinuous buffer system of Laemmli (15). After electrophoresis, the gels were silver stained (32).

Rubidium efflux.

P. putida cells were grown in 30 ml of M9 minimal medium containing 15 mM 3-methylbenzoate as the sole carbon source and supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and 1 mCi of 86RbCl (1 mCi/mmol). Cells were harvested by centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 min), washed in M9 minimal medium without a C source, and resuspended in the same minimal medium with either 15 mM 3-methylbenzoate or 28 mM glucose plus 5 mM IPTG. The amount of 86RbCl retained intracellularly by the cells was measured by harvesting 200-μl aliquots of the culture by filtration. The pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of M9 minimal medium and mixed with 500 μl of scintillation liquid, and emission was counted with a Packard scintillation counter.

Oxygen uptake assays.

Oxygen consumption rates of whole cells of P. putida were determined with a polarographic Clark oxygen electrode. A 0.1-ml aliquot of a P. putida culture was transferred to 1 ml of fresh medium kept at 30°C in the chamber of the oxygen electrode. The rate of oxygen consumption was then recorded for 5 to 10 min.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Loss of viability of P. putida strains that express heterologous killing genes.

Two different killing genes were incorporated separately into the chromosome of P. putida KT2440 cells. P. putida CMC4 carries mini-Tn5-Km with a PA1-04/03::gef fusion integrated in the host chromosome (23). P. putida CMC12 carries mini-Tn5-Tel with a PA1-04/03::gene E fusion on the chromosome (this study). To control expression of the killing genes, the lacI gene, encoding the LacI repressor, was expressed from the Pm promoter for the meta-cleavage pathway of the P. putida TOL plasmid pWW0, whose expression is in turn controlled by the xylS gene (10, 30). In the presence of XylS effectors, such as 3-methylbenzoate, expression of the killing proteins is prevented and the strains survive. However, in the absence of effectors and in the presence of IPTG, cell growth is rapidly arrested as a consequence of expression of the lethal proteins from the PA1-04/03 promoter (1, 11, 30). Such is not the case with the control strains P. putida EEZ15-K3 and CMC13, which do not bear the killing genes. (Note that in this series of assays, IPTG was added to rapidly titrate out the LacI protein in the cells).

In order to analyze whether cell growth arrest in cells bearing the containment system was the result of a loss of cell viability, we counted viable cells after induction of the system by transferring cells to a culture medium without 3-methylbenzoate and with IPTG. Cells of P. putida EEZ15-K3, CMC4, CMC13, and CMC12 growing exponentially (about 106 to 107 CFU/ml) in M9 minimal medium with glucose and 3-methylbenzoate were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 50 mM phosphate buffer, and then resuspended at the same cell density in M9 minimal medium containing glucose and either 3-methylbenzoate or IPTG. The number of cells of the two control strains increased with time regardless of the growth medium (data not shown). In contrast, the number of CFU of CMC4 and CMC12 per milliliter increased with time in medium with 3-methylbenzoate (Fig. 3) but not in the presence of IPTG. After an initial lag, the number of viable cells decreased in both strains. One hour after induction, about 33 and 4% of the initial cells were viable in cultures of P. putida CMC4 and CMC12, respectively (Fig. 3). The initial lag probably represents the time required for LacI turnover and synthesis and accumulation of the killer proteins. The fact that φX174 lysis protein E-mediated killing of P. putida CMC12 cells was faster than that of P. putida CMC4 cells, which expressed the gef gene, might indicate that the critical concentration of protein E needed to trigger killing is lower than that of the Gef protein or that lysis protein E is more efficient than the Gef protein in provoking cell death when the cells are growing exponentially. We assumed that there were equal levels of expression of the killing genes in both strains, because the two killing genes used in this study were expressed from the same promoter and the respective fusions were located on the host chromosomes. Nonetheless, prolonged incubation of CMC4 and CMC12 with IPTG led to a steady reduction in cell viability. The number of viable cells was on the order of 0.01% the initial number for strain CMC12 7 h after induction of the system, and the number was even lower for strain CMC4. Prolonged incubation led to a further decrease in cell viability in both strains, although in some cases killing-resistant mutants appeared.

FIG. 3.

Cell viability of P. putida strains after induction of the expression of killing genes. Cells of P. putida CMC4 (PA1-04/03::gef) (A) and CMC12 (PA1-04/03::gene E) (B) growing exponentially in M9 minimal medium with glucose and 3-methylbenzoate were transferred at time zero to medium containing glucose and either 3-methylbenzoate (closed symbols) or IPTG (open symbols). At the indicated times, viable cells were counted on LB medium plates containing 3-methylbenzoate and the appropriate antibiotics.

Physiological consequences of the expression of killing genes.

As stated in the introduction, the cytoplasmic membrane is the ultimate target of both φX174 lysis protein E and Gef in E. coli. The insertion of these proteins in the cell membrane of this microorganism leads to cell death, most likely via an alteration of cell membrane permeability.

To test the physiological consequences of the expression of the heterologous E. coli proteins in P. putida, we first monitored oxygen consumption in P. putida cells expressing each of these two killing proteins. At 30 min after induction of expression of the killing proteins, the rate of oxygen consumption by P. putida CMC12 and CMC4 (about 0.2 ± 0.1 μmol of O2/mg of cell protein per min) was about 8% that in noninduced, control cultures kept in the presence of 3-methylbenzoate (3.0 ± 0.4 μmol of O2/mg of cell protein per min). The rate of respiration in the control strains was not significantly affected by the removal of 3-methylbenzoate or the presence of IPTG and was about 3.5 ± 0.5 μmol of O2/mg of protein per min. These results suggest that the cytoplasmic membrane of P. putida is indeed the target of Gef and φX174 lysis protein E and that the expression of these proteins leads to alterations in cell respiration.

This hypothesis is also supported by the observation that induction of the synthesis of these killing proteins in P. putida CMC4 and CMC12 led to a rapid loss of K+ ions from the cytoplasm. To model K+ loss, cells were preloaded with 86Rb+ as described in Materials and Methods and then transferred to culture medium with or without 3-methylbenzoate. We found less retention of 86Rb+ ions in the cytoplasm of cells incubated without 3-methylbenzoate (less than 3% the loaded 86Rb+) than in that of cells kept in culture medium containing 3-methylbenzoate (about 20 to 30% the loaded 86Rb+). Control cells in culture medium with or without 3-methylbenzoate retained similar amounts of loaded 86Rb+, which were in the same range as those retained by strains bearing the containment system and kept in culture medium with 3-methylbenzoate.

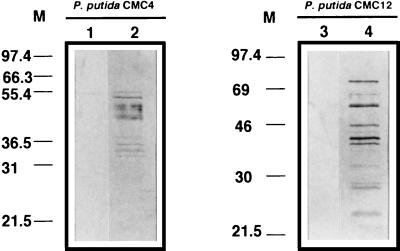

The release of cellular material due to Gef- and φX174 lysis protein E-mediated membrane damage was investigated. We used SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to analyze the release of proteins to the culture supernatants of P. putida EEZ15-K3, CMC4, CMC13, and CMC12 in cultures with and without IPTG. No proteins could be detected in culture supernatants of control strains EEZ15-K3 and CMC13 during the 6-h experiment regardless of the growth medium or in culture supernatants of CMC4 and CMC13 grown with 3-methylbenzoate but without IPTG (data not shown). However, in culture supernatants of CMC4 and CMC12 incubated in the absence of 3-methylbenzoate but in the presence of IPTG, proteins were detected 90 min after the addition of IPTG (data not shown). In both cases, the total amounts of proteins detected increased with time, as deduced by the number and density of the bands in the gels (Fig. 4). These results indicate that lysis of P. putida cells occurs after the expression of Gef and φX174 lysis protein E. The differences in the patterns of proteins released (Fig. 4) from each of the two P. putida strains after the induction of killing suggest that Gef-mediated lysis and φX174 protein E-mediated lysis may occur through different mechanisms.

FIG. 4.

Protein release from P. putida CMC4 (PA1-04/03::gef) and CMC12 (PA1-04/03::gene E) after induction of the expression of killing genes. P. putida cells growing exponentially in M9 minimal medium with glucose and 3-methylbenzoate were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in M9 minimal medium without a C source, and resuspended in M9 minimal medium with glucose and 1 mM IPTG. Samples were taken at 0 h (lanes 1 and 3) and 6 h after induction (lanes 2 and 4). The released proteins were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers to the left of each panel indicate molecular masses (M) in kilodaltons.

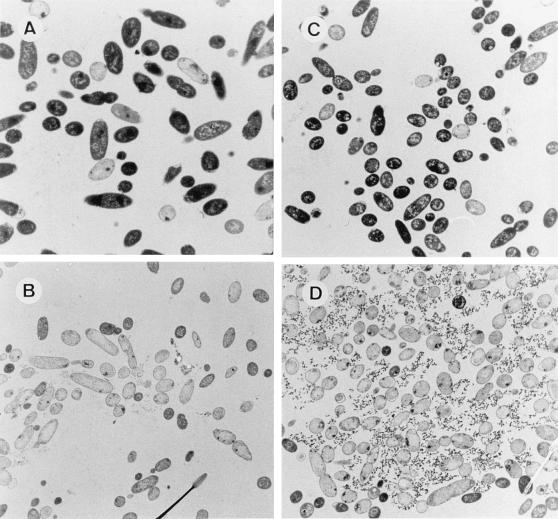

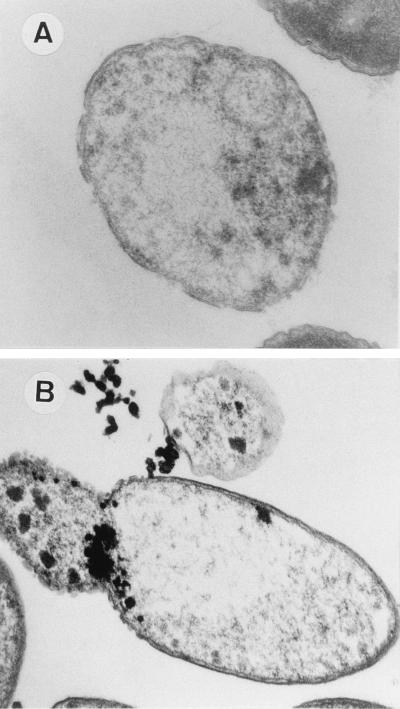

Ultrastructure of P. putida bacteria that express killing genes.

The ultrastructure of P. putida EEZ15-K3, CMC4, CMC13, and CMC12 cells was analyzed before and after transfer to 3-methylbenzoate-free medium. The ultrastructure of the control strain was not significantly affected by the culture medium; almost 100% of the cells appeared electron dense when examined by transmission electron microscopy (data not shown). In contrast, significant differences were observed in CMC4 and CMC12, depending on the culture medium. Before the induction of the killing genes, more than 92% of the cells (counted in six different field exposures) of these two strains were electron dense. These cells exhibited well-defined outer and inner membranes and showed the typical rod morphology of Pseudomonas (Fig. 5A and C). Induction of the expression of Gef or φX174 lysis protein E was typically followed by a change in the appearance of the cells; in both cases, the cells became almost completely transparent (Fig. 5B and D). The occurrence of ghost cells is evidence that cytoplasmic material has been lost, as discussed above. Three hours after transfer to medium lacking 3-methylbenzoate, 80% of the cells (counted in six different field exposures) were lysed and appeared as ghosts (Fig. 5B and D).

FIG. 5.

Transmission electron micrographs of ultrathin sections of P. putida CMC4 (A and B) and P. putida CMC12 (C and D) cells. A and C, noninduced cells growing in M9 minimal medium with glucose and 3-methylbenzoate. B and D, Induced cells 3 h after transfer to M9 minimal medium with glucose and IPTG. Magnification, ×4,000.

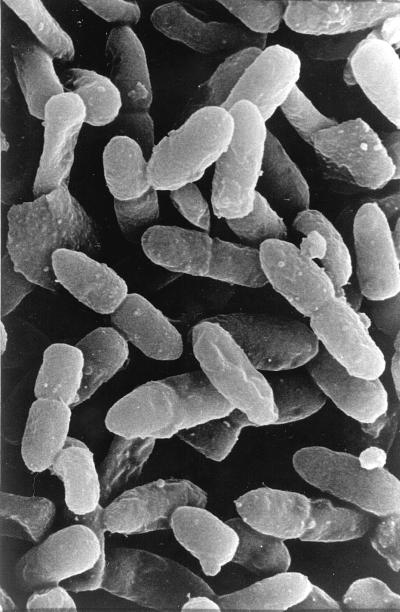

P. putida CMC4 cells expressing the gef gene showed numerous holes in the cell envelope (Fig. 6A). In P. putida CMC12, which expressed gene E, the holes appeared to be grouped together instead of distributed along the cell envelope. Cytoplasmic material was observed leaking out through these holes (Fig. 6B). Lysed cells of P. putida CMC12 were also observed by high-resolution scanning electron microscopy. Bleb-like structures could be seen emanating from some of the cells (Fig. 7). It is well known that in E. coli, protein E forms a unique transmembrane hole through which cytoplasmic material is released to the external medium (37, 38). The protein may act in a similar way in P. putida.

FIG. 6.

Transmission electron micrographs of ultrathin sections of lysed P. putida CMC4 (A) and P. putida CMC12 (B) cells after the expression of killing genes. Magnification, ×40,000.

FIG. 7.

Scanning electron micrograph of lysed P. putida CMC12 cells after the expression of gene E from bacteriophage φX174. Magnification, ×3,500.

The results presented in this study indicate that the cytoplasmic membrane is the target of Gef and φX174 lysis protein E in P. putida. After the expression of the genes for these two E. coli killing proteins in P. putida cells, the cell envelope of the heterologous host loses its integrity, numerous holes appear, and the cytoplasmic content is released to the extracellular medium; as a consequence, cell death occurs. Comparative studies on the efficiency of host killing by these two genes under environmental conditions should provide new insights into the potential of these genes for the biological containment of P. putida strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Commission of the European Communities (BIO4-CT97-2270), GX-Biosystems España S.L., and Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (BIO97-0657).

Footnotes

Corresponding author. Mailing address: Estación Experimental del Zaidín, CSIC, Apdo. de Correos 419, E-18008 Granada, Spain. Phone: 34-58-121011. Fax: 34-58-129600. E-mail: carmen@eez.csic.es.

REFERENCES

- 1.Contreras A, Molin S, Ramos J L. Conditional suicide containment system for bacteria which mineralize aromatics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1504–1508. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1504-1508.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Analysis and construction of stable phenotypes in gram-negative bacteria with Tn5 and Tn10-derived mini-transposons. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:386–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díaz E, Munthali M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Universal barrier to lateral spread of specific genes among microorganisms. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:855–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowling D N, O’Gara F. Metabolites of Pseudomonas involved in the biocontrol of plant disease. Trends Biotechnol. 1994;12:133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duque E, Marqués S, Ramos J L. Mineralization of p-methyl-14C-benzoate in soils by Pseudomonas putida (pWW0) Microb Releases. 1993;2:175–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franklin F C H, Bagdasarian N M, Bagdasarian M, Timmis K N. Molecular and functional analysis of the TOL plasmid pWW0 from Pseudomonas putida and cloning of the genes for the entire regulated aromatic ring meta cleavage pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7458–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galli E, Barbieri P, Bestetti G. Potential of pseudomonads in the degradation of methylbenzenes. In: Galli E, Silver S, Withold B, editors. Pseudomonas. Molecular biology and biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 268–276. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haby P A, Crowley D E. Biodegradation of 3-chlorobenzoate as affected by rhizodeposition and selected carbon substrates. J Environ Qual. 1996;25:304–310. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Molecular cloning of gene xylS of TOL plasmid: evidence for positive regulation of the xylDEGF operon by xylS. J Bacteriol. 1981;148:413–418. doi: 10.1128/jb.148.2.413-418.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen L B, Ramos J L, Kaneva Z, Molin S. A substrate-dependent biological containment system for Pseudomonas putida based on the Escherichia coli gef gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3713–3717. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3713-3717.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler B, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. A general system to integrate lacZ fusions into the chromosomes of gram negative eubacteria: regulation of the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid studied with all controlling elements in monocopy. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:293–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00587591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kloepper J W, Liffshitz R, Zablotowicz R M. Free living bacterial inocula for enhancing crop productivity. Trends Biotechnol. 1989;7:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knudsen S M, Karlström O H. Development of efficient suicide mechanisms for biological containment of bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:85–92. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.85-92.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanzer M, Bujard H. Promoters largely determine the efficiency of repressor action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8973–8977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lugtenberg B J J, de Weger L A. Plant root colonization by Pseudomonas spp. In: Galli E, Silver S, Witholt B, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformation, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1992. pp. 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lugtenberg B J J, de Weger L A, Bennett J W. Microbial stimulation of plant growth and protection from disease. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1991;2:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molin S, Boe L, Jensen L B, Kristensen C S, Givskov M, Ramos J L, Bej A K. Suicidal genetic elements and their use in biological containment of bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:139–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molin S, Klemm P, Poulsen L K, Biehl H, Gerdes K, Andersson P. Conditional suicide system for containment of bacteria and plasmids. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:1315–1318. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molina, L., E. Duque, C. Ramos, and J. L. Ramos. 1998. Unpublished results.

- 23.Molina L, Ramos C, Ronchel M C, Molin S, Ramos J L. Construction of an efficient biologically contained Pseudomonas putida strain and its survival in outdoor assays. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2072–2078. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2072-2078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Sullivan D J, O’Gara F. Traits of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. involved in suppression of plant root pathogens. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:662–676. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.4.662-676.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos, C., L. Molina, S. Molin, and J. L. Ramos. 1998. Unpublished results.

- 26.Ramos J L, Andersson P, Jensen L B, Ramos C, Ronchel M C, Díaz E, Timmis K N, Molin S. Suicide microbes on the loose. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:35–37. doi: 10.1038/nbt0195-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos J L, Díaz E, Dowling D, de Lorenzo V, Molin S, O’Gara F, Ramos C, Timmis K N. The behavior of bacteria designed for biodegradation. Bio/Technology. 1994;12:1349–1356. doi: 10.1038/nbt1294-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos J L, Duque E, Ramos-González M I. Survival in soils of an herbicide-resistant Pseudomonas putida strain bearing a recombinant TOL plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:260–266. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.260-266.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos-González M I, Ramos-Díaz M A, Ramos J L. Chromosomal gene capture mediated by the Pseudomonas putida TOL catabolic plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4635–4641. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4635-4641.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronchel M C. Construcción de cepas de Pseudomonas putida portadoras de sistemas condicionales de contención biológica para la eliminación de contaminantes ambientales. Ph.D. thesis. Granada, Spain: Universidad of Granada; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ronchel M C, Ramos C, Jensen L B, Molin S, Ramos J L. Construction and behavior of biologically contained bacteria for environmental applications in bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2990–2994. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2990-2994.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sammons D W, Adams L D, Nishizawa E E. Ultrasensitive silver-based color staining of polypeptides in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis. 1981;2:135. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez J M. Desarrollo de herramientas moleculares para el análisis genético y la generación de nuevos fenotipos en Pseudomonas. Ph.D. thesis. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szafranski P, Mello C M, Sano T, Smith C L, Kaplan D L, Cantor C R. A new approach for containment of microorganisms: dual control of streptavidin expression by antisense RNA and the T7 transcription system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1059–1063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walton B T, Anderson T A. Microbial degradation of trichloroethylene in the rhizosphere: potential application to biological remediation of waste sites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1012–1016. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.4.1012-1016.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witte A, Lubitz W. Biochemical characterization of φX174-protein-E-mediated lysis of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1989;180:393–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Witte A, Wanner G, Bläsi U, Halfmann G, Szostak M, Lubitz W. Endogenous transmembrane tunnel formation mediated by φX174 lysis protein E. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4109–4114. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.4109-4114.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witte A, Wanner G, Sulzner M, Lubitz W. Dynamics of Phix174 protein E-mediated lysis of Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:381–388. doi: 10.1007/BF00248685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worsey N J, Williams P A. Metabolism of toluene and xylenes by Pseudomonas putida (arvilla) mt-2: evidence for a new function of the TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:7–13. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.7-13.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]