Abstract

The specific factors and response strategies that affect COVID-19 transmission in local communities remain under-explored in the current literature due to a lack of data. Based on primary COVID-19 data collected at the community level in Wuhan, China, our study contributes a community-level investigation on COVID-19 transmission and response strategies by addressing two research questions: 1) What community factors are associated with viral transmission? and 2) What are the key mechanisms behind policy interventions towards controlling viral transmission within local communities? We conducted two sets of analyses to address these two questions—quantitative analyses of the relationship between community factors and viral transmission and qualitative analyses of policy interventions on community transmission. Our findings show that the viral spread in local communities is irrelevant to the built environment of a community and its socioeconomic position but is related to its demographic composition. Specifically, groups under the age of 18 play an important role in viral transmission. Moreover, a series of community shutdown management initiatives (e.g., group buying, delivering supplies, and self-reporting of health conditions) play an important role in curbing viral transmission at the local level that can be applied to other geographic contexts.

Keywords: COVID-19, Community transmission, Community shutdown management, Response strategy, Wuhan

1. Introduction

On December 2019, Chinese health authorities reported the discovery of the novel coronavirus, later named ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO). Due to the virus' high rate of transmission via respiratory droplets, governments across the world have resorted to restricting human mobility (Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020) by employing methods such as closing public transit and requiring residents to stay at home (Wang et al., 2020). Yet mere city-level lockdowns might not prevent viral transmission between individuals (e.g., between family members and neighbours) at the local community level (a community in China is synonymous with the geographical designation of neighbourhoods in western countries) (Byambasuren et al., 2020). Thus, the built environment of a local community was thought to be an important mediator of the COVID-19 transmission, particularly at the early stage of the outbreak (Honein et al., 2020). We hereafter term the viral transmission that occurs at the local community level as community transmission. Despite the urgent need to understand the mechanism of viral transmission at a micro-level, few literatures have studied this due to the lack of available community level data.

Due to privacy concerns, COVID-19 data acquired by governments and healthcare authorities are only available at the aggregated population level (Kapa et al., 2020). Hence, most of existing studies have largely been based upon data at a relatively coarse level, such as that of the US county level, Australia's state level, and China's city level (Wang et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). This prevents researchers and officials from researching and understanding pertinent factors that can be manipulated to curb viral transmission within local communities. Although studies have found that the built environment (e.g. green spaces and walkability) is associated with the incidence of chronic diseases (e.g. obesity and diabetes) (e.g., Booth et al., 2005; Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007; Papas et al., 2007), whether such associations can be extrapolated to explain the transmission of infectious diseases (such as COVID-19) remains questionable. Given that residents are most frequently mobile within their local communities during a city-level lockdown, this poses a higher chance of infection or exposure to COVID-19 via an individual's close contact with neighbours. Based upon this observation, we hypothesize that the environmental infrastructure of a local community may mediate viral transmission. Hence, exploring factors and mechanisms that can effectively curb community transmission will aid governments and health authorities in combating future pandemics and public emergencies.

To tackle the knowledge deficit, our study provides a community-level investigation of COVID-19 transmission. Here, we examine the effect of variables at the community level on viral transmission and explore the mechanisms by which implemented public health policies control viral spread within local communities. Our study has two research questions to address: 1) Which community factors are associated with viral transmission? and 2) What are the key mechanisms of controlling viral transmission within local communities through policy interventions? Drawing on the primary COVID-19 data collected at the community level in Wuhan, China, we conduct two sets of analyses to address these two research questions: 1) quantitative analyses of the relationship between community factors (i.e. built environment, demographic composition, and socioeconomic position) and viral transmission to address the first research question; and 2) qualitative analyses of the implementation and effectiveness of policy interventions against community transmission to address the second research question. These quantitative and qualitative evidence provided in our study deepen the understanding of the micro-level mechanisms of viral transmission and can be integrated with existing methods as well as knowledge of public health interventions to combat COVID-19.

The remainder of our paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews current studies on COVID-19 within a global and Chinese context, respectively, and reiterates the contribution of our study. Section 3 presents the data and methods used in our analysis. Section 4 discusses the findings from quantitative and qualitative analyses. Section 5 provides a discussion of the key findings, policy implications and limitations of our study, followed by a conclusive remark.

2. Literature review

2.1. COVID-19 policy interventions in the international context

Although conducting a systematic literature review of the current COVID-19 policy interventions is beyond the scope of our research, synthesizing several popular review papers (e.g., AlTakarli, 2020; Harapan et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2021b) enables us to produce a holistic picture of various COVID-19 policy interventions that are currently implemented across the world. A large body of policy-oriented studies on COVID-19 have found major policy interventions repetitively used across many countries include lockdown orders, travel restrictions, social distancing, and border control—all of which have effectively reduced COVID-19 transmission (Chen et al., 2020; Djurović, 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). These papers provide empirical studies in China (Chen et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Kraemer et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020), in Italy, Spain, France and multiple other European countries (Dickson et al., 2020; Salje et al., 2020; Tobías, 2020), and in the U.S (Banerjee & Nayak, 2020; Courtemanche et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2021a; Huang et al., 2022).

Another common finding from these worldwide studies is that the effect of policy interventions on viral spread has both temporal and spatial heterogeneity, along with the observed time-lag effect of social restrictions (e.g., reducing or impeding human mobility). Policy interventions, despite being globally effective in reducing the rate of viral transmission, have had heterogeneous impacts at a local level (Dickson et al., 2020; O'Sullivan et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). For example, large capital cities and metropolitan areas encounter more disruptions and challenges towards controlling infection because they cannot be easily broken down into separately managed regions due to the administrative boundary (O'Sullivan et al., 2020). Highly populated cities in countries with a large population base (e.g., India and China) are compelled to take stronger measures to prevent a potential resurge in COVID-19 cases and to prudently control the degree by which restrictive policies are relaxed (Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). Lockdown on public transport (e.g., metro, railway, bus, and flight) in high density cities with large population bases has the most profound impact on viral spread, compared to locking down other public spaces (Zheng, 2020). The aftermaths in India show that a cautious post-lockdown strategy should be flexible and spatially varied, by easing physical distancing restrictions within high-risk places while maintaining restrictions between high-risk places (DeFries et al., 2020). In terms of their implementation, stringency, and scales, policy interventions need to be adjusted across different phases of the pandemic. For example, at the initial stage of the outbreak, human mobility was observed to be highly relevant to the growth rate of the COVID-19 cases. However, this association became weaker and marginal after the implementation of large-scale lockdowns and other national travel restrictions (Kraemer et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). Despite their effectiveness, public health interventional policies, if not implemented within a timely manner, has a reduced ability to curb viral transmission (Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). Though effective, the aforementioned policy interventions were typically implemented at a larger scale (e.g., travel ban and border closure at the country and state, or city-level lockdown orders). Relatively less attention has been given to how policy interventions were implemented at a community or neighbourhood level, which can be potentially attributed to the lack of specificity from the available data.

2.2. COVID-19 policy interventions in the Chinese context

China has a long history of combatting coronaviruses, as evidenced by health crises such as the SARS in 2003 and COVID-19 in 2020 (AlTakarli, 2020). Wuhan, one of China's mega-cities, experienced the first wave of COVID-19 and soon became the epicentre in early 2020. Here, policy interventions were designed, implemented, and tested by different levels of the governmental hierarchy (Kraemer et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). A multitude of studies have come to a general consensus that China's national-level policy interventions (e.g., impeding air flights, closing the railway and the road network, and closing the national border during the early stages of the pandemic) have had prompt, timely, and positive effects on reducing and slowing down viral transmission (Chen et al., 2020; Chinazzi et al., 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). At the provincial and municipal levels, early policy interventions and response strategies adopted by the Wuhan local government (e.g., early reporting and situation monitoring, quarantining at home, large-scale surveillance, and the preparation of medical facilities and supplies) were successful in reducing and slowing down the pandemic's spread into other cities and provinces in China (Kong et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Wu, Leung, et al., 2020). Such interventional policies have been implemented differently across social groups with different demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds (Kusuma et al., 2020) as well as with different access to protective gears (Qiu et al., 2020). After city-level lockdown, a series of management plans for community shutdown, at the community and neighbourhood level, were implemented locally, although such community-level policy interventions are relatively less explored compared to the aforementioned policy interventions at above the community level. This may be because the effectiveness and stringency of policy interventions above the community level can be quantified relatively easily in the pandemic simulation and modeling. For example, police intervention on mobility control can be quantified as the Policy Stringency Index to be integrated in the SEIR model (e.g., set up as a parameter) (Gatto et al., 2020; Peirlinck et al., 2020; Rainisch et al., 2020). In contrast, policy interventions at the community level involve detailed planning and the arrangement of various labour forces (e.g., volunteers and property managers), the distribution of resources, dissemination of information, and the provision of service—all of which are difficult to quantify and access in quantitative studies.

2.3. COVID-19 policy interventions: from blanket lockdowns to delicacy measures

Apart from regular measures such as adhere to good hand hygiene, beware of social distance to others, recent literatures of policy interventions have been directed towards the combinations of ‘lockdown’ measures and their impacts. These interventions vary from city-level lockdowns to cancellations of public events and school and workplace closures (Glover et al., 2020). On the one hand, the significance of the full/partial lockdown in controlling the spread of Covid-19 has been underscored (Iddrisu et al., 2020; Ren, 2020; You, 2020). On the other hand, the problem of unprecedented disruption to daily lives and economic activity caused by lockdowns has been examined and wildly discussed (Adams-Prassl et al., 2020; Balmford et al., 2020; Luijten et al., 2021). For example, Glover et al. (2020) argue that blanket lockdowns may come with physical and psychological health harms, group and social harms, and opportunity costs. In order to minimize the negative impact of large-scale lockdowns, delicacy measures for epidemic prevention such as big-data-based epidemiological surveys or limited lockdowns have been proposed and drawn an increasing attention (Cai et al., 2020; Wu, Zhang, et al., 2020). An enlightening study comes from Alon et al. (2020), revealing that age-specific policies are more effective in developing countries rather than lockdowns on the basis of national scale data. There is an immediate implication that delicacy policy interventions at the community level would contribute to more efficient epidemic prevention.

When evaluating community-level policy interventions, another perspective that is neglected is how the built environment of a local community affects viral transmission. Before a city-level lockdown, community transmission had often occurred and became the main way of transmission after the lockdown as the residents' mobility was limited to within their local communities (largely gated communities) (Oka et al., 2021). Here, the built environment of a local community becomes a crucial mediator and pathway through which residents may unintentionally expose themselves to the virus via close contacts with neighbours who have been infected but are not tested or confirmed. The built environment has been widely incorporated in health geography and urban epidemiology studies to examine how the built environment of neighbourhoods affects the incidence of chronic diseases (e.g. obesity and diabetes) (Booth et al., 2005). However, whether such effects of the built environment on chronic diseases (e.g. Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007; Papas et al., 2007) can be further applied to control and prevent the incidence of infectious diseases such as COVID-19 remains under-explored. Because local communities play a crucial role in viral transmission by providing a space and place where residents can go out, exercise, and have interactions with their surroundings, it is important to understand the pathways and mechanism through which policy interventions function to control viral spread at the community level – one of the objectives that our study aims to achieve.

2.4. Contribution of this study

Given the aforementioned knowledge gaps, our study contributes a community-level investigation on viral transmission within local communities in Wuhan—the first Chinese city in which COVID-19 was reported and monitored. Given its large number of communal COVID-19 cases at the initial stage of the pandemic, Wuhan serves as a good pilot study to examine the effectiveness and stringency of policy implementation. The experiences derived from Wuhan's efforts in combatting COVID-19 have provided evidential support for the interventional policies that were later widely employed in other Chinese cities and in many countries. Our study has two objectives—to examine the effect of community factors on COVID-19 transmission and to explore the key mechanisms behind using policy interventions to control viral transmission within communities. By conducting quantitative analyses of the relationship between community factors and viral transmission as well as qualitative analyses of interventional policies on communal transmission, our study provides an in-depth, micro-level investigation on viral transmission in local communities. The key mechanisms and community shutdown initiatives suggested in our study have great potential to be applied to other geographic contexts towards combatting against the resurgence of COVID-19 in the post-pandemic era. Furthermore, our findings can be employed to prevent and control future public health emergencies, such as a viral outbreak that may arise due to heightening extents of globalisation, urbanisation, and the human invasion of ecosystems.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data

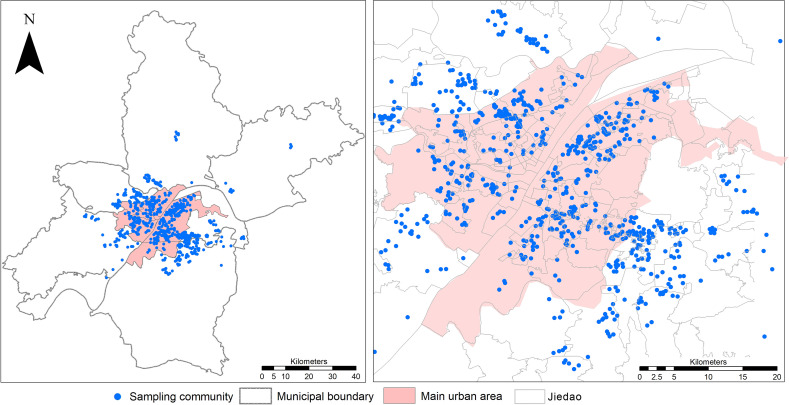

China has a vertical system in urban governance, which consists of three levels of administrative units: administrative district, subdistrict (jiedao), and community (Gao et al., 2021). Our study took ‘community’ as the spatial unit in order to examine how COVID-19 transmits within communities—a topic less commonly explored in current literature. The primary COVID-19 data were retrieved from ‘Notification Boards’ that were placed within local communities. During the lockdown period in Wuhan, residential communities began to implement ‘community shutdown management’ and reported daily COVID-19 cases to the government beginning in 12 February 2020. The records of confirmed cases, suspected cases and other information reported by community committees were posted at the gate of each residential building within local communities. These records were anonymous, and their reliability was checked and approved by the local health commissions. We manually collected these records dated from 12 February to 17 February 2020, which totalled to 11,932 COVID-19 cases (including 6491 confirmed cases and 5441 suspected cases) in 386 communities located in the main urban area of Wuhan (Fig. 1 ). Given that suspected cases were largely confirmed within two weeks (Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020), our study included both confirmed and suspected cases to better reflect the actual transmission of COVID-19 at the community level. The communities with reported COVID-19 cases were geocoded using the Application Programming Interface of Amap (2020) based on the communities' names and corresponding geographic coordinates. Our sample data accounted for 15.18% of 42,752, the total number of COVID-19 cases confirmed in Wuhan by 17 February 2020 (National Health Commission, 2020) and covered most communities in Wuhan. Thus, the primary sample data were reasonably reliable and representative in reflecting how communities responded to the viral spread at the community level.

Fig. 1.

Study area and the locations of sample communities.

Next, we collected multi-source datasets from AnJuKe (2020), one of China's biggest real estate websites, and the Wuhan Bureau of Statistics (2015). Using the current existing literatures as reference, (e.g. Gordon-Larsen et al., 2006; Li et al., 2007; Papas et al., 2007), we quantified seven variables to measure each community's built environment, socioeconomic position, and demographic composition. These variables included housing prices to represent the socioeconomic position of each community; the age brackets of residents represent the demographic composition of a community; green coverage and underground parking represent the openness of space within a community; building age represents the configuration of elevators in buildings (e.g., buildings built before 2000 rarely equipped with elevators—locations where viral transmission is easier than that in open space).

3.2. Methodology

We conducted two sets of analyses: 1) quantitative analyses to examine which community factors (e.g. built environment, socioeconomic position and demographic composition) affect viral transmission; and 2) qualitative analyses to summarise the implementation and effectiveness of three core policy interventions on community transmission. The qualitative analyses were conducted via archive searching and reviewing the response strategies and policies implemented within the Hubei Province and Wuhan City. The quantitative analyses included a global spatial autocorrelation analysis, a correlation analysis, a spatial lag regression (SLR) analysis and a three-dimensional visualisation to examine the relationship between viral spread and community factors that are related to the built environment, socioeconomic position, and demographic composition.

Statistically, a global Moran's Index was first applied to analyse the spatial pattern of the sample communities. The global Moran's Index was an indicator of the spatial autocorrelation across an entire study area. To obtain more robust results, the number of permutations was set to 999 along with a threshold significance level of p = 0.05. Then, a bivariate Pearson correlation was used as a pre-test of the relationship among selected variables to reduce the effect of variables' collinearity on the calculations. A Pearson correlation coefficient ranges between −1 and 1; 1 means total positive correlation, 0 means no correlation and −1 means total negative correlation. Next, we performed a spatial-lag regression (SLR), which is a linear spatial autoregressive method with the advantage of capturing spatial dependency in regression analyses, thus avoiding statistical problems such as unstable parameters and unreliable significance tests (Anselin, 2013). We established this SLR model in GeoDa using the first-order rook's move contiguity (i.e. adjacent edges) and allowing the diagnostics from GeoDa to determine the most appropriate spatial weight matrix (Anselin & Le Gallo, 2006). The spatial lag model is specified as follows (Anselin, 2013):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Y is the spatially lagged dependent variable (i.e. the number of COVID-19 cases normalised by the number of population at the community level); α is the spatial autoregressive structure of the disturbance φ; W y represents the spatial weight matrix of the dependent variable Y; X is a matrix containing a set of independent variables (age group in our study); β is the coefficient of X; and ε is the normally distributed error.

Finally, we built two three-dimensional visualisation models in ArcGlobe, both with the height representing the number of COVID-19 cases, and one horizontal axis representing the SLR model residuals and the other horizontal axis representing the percentage of a certain age group in a community.

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative analysis to reveal the effect of community factors on COVID-19 transmission

We tested the spatial autocorrelation of COVID-19 cases using the Moran's Index, which shows that the confirmed cases are significantly clustered (Moran's Index = 0.10, Z-score = 32.35, and p < 0.001), indicating there is a need to utilize a spatial lag regression at the later stage as a local regression model in order to reduce the effect of spatially autocorrelated data on the modeling performance.

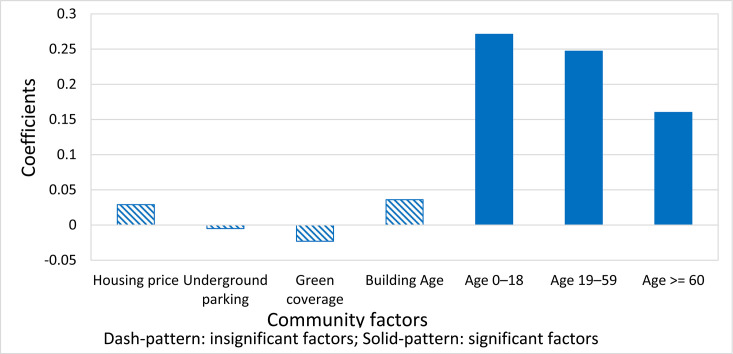

We then explored the correlation between COVID-19 cases and housing price, green coverage, underground parking, building age, as well as the age structure of the community (Fig. 2 and Table 1 ). Our results indicate that three age groups were positively (p < 0.01) correlated with COVID-19 cases. The magnitude of the correlation coefficients of the three age groups decreases from 0.271 (age 0–18) to 0.247 (age 19–59) and 0.16 (age older than 60) (Fig. 2), reflecting that COVID-19 transmission varies across age groups is more highly correlated with the population under the age of 18 than with the older population. This may be due to the increased mobility of individuals under the age of 18 during the early stage of the epidemic. Additionally, the increased risk of infection among the youth may also be due to the shortage of masks and other preventive equipment during the early stage of the epidemic. The remaining factors are insignificantly correlated with COVID-19 cases, which indicates that a community's socioeconomic position and its built environment have no significant impact on COVID-19 transmission. In other words, the built environment does not play a crucial role in controlling COVID-19, potentially due to the virus' highly infectious nature.

Fig. 2.

Correlation coefficients.

Table 1.

Results of correlation analysis.

| Socioeconomic position |

Built environment |

Demographic composition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing price | Underground parking | Green coverage | Building Age | Age 0–18 | Age 19–59 | Age ≥60 | |

| Coefficient | 0.029 | −0.001 | −0.023 | 0.036 | 0.271 | 0.247 | 0.160 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.570 | 0.985 | 0.679 | 0.510 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| N | 385 | 322 | 331 | 337 | 386 | 386 | 386 |

Note: Bold: p < 0.01 at the significant level of 99% (2-tailed) and N = 386.

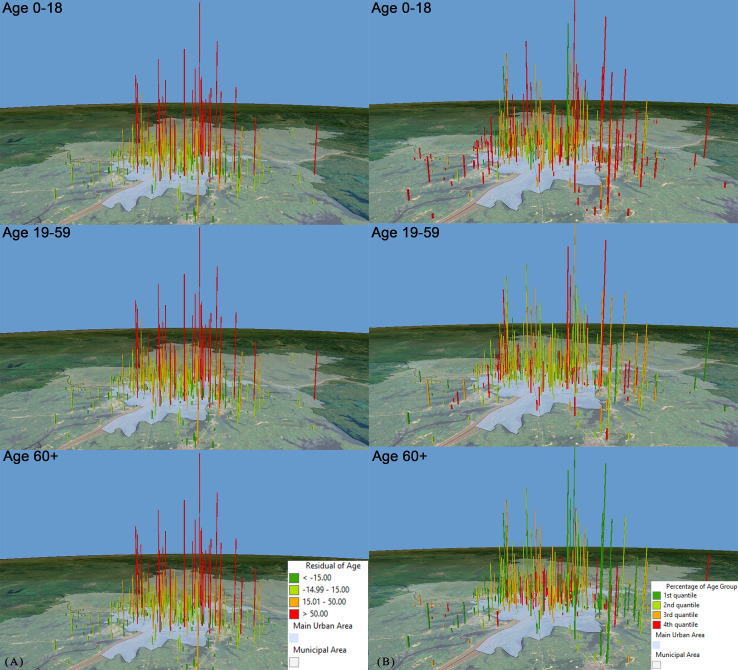

We filtered out those insignificant factors and further conducted the SLR analysis to reveal the relationship between COVID-19 cases and significant community factors (age groups). The SLR result further confirms that age is the only significant factor (p < 0.01) associated with COVID-19 cases. The R-squares of the regression based on age 0–18 is the highest (0.144), followed by 0.132 (age 19–59) and 0.1 (age >60). In Fig. 3A, the height of cylinders represents the number of COVID-19 cases in a community, and the colour of cylinders represents the ranges of the regression residuals. More specifically, the red colour marks the communities with larger values of standardised residuals (>50) where age is not associated with COVID-19 cases; the green colour marks the communities with smaller residual values (−15<residual<15), where age is associated with COVID-19 cases. In Fig. 3B, the height of the cylinders stands for the number of COVID-19 cases and the colour of the cylinder represents the proportion of each age group in a community, classified by quartile. More specifically, the red colour indicates that population in a given age group accounts for a larger proportion in a community, compared to the green colour representing a smaller proportion. The result shows that communities with a larger proportion of population at age 0–18 have more COVID-19 cases reported, and the communities with a larger proportion of population at age 19–59 and at age older than 60 have fewer cases reported. This aligns with the findings from the preceding correlation analysis.

Fig. 3.

Results of the spatial lag regression between COVID-19 cases and age groups.

(A) Standardised residuals; (B) percentage of population in a given age group over the total population.

In summary, there was no significant relationship between COVID-19 cases and the built environment factors during the lockdown period in Wuhan, while age 0–18 is the sole significant factor associated with the COVID-19 transmission. However, this quantitative analysis is not able to reveal how policy interventions function in controlling COVID-19 transmission, which will be further explored and explained in the following section through a qualitative investigation.

4.2. Qualitative analysis to reveal policy intervention for community transmission

4.2.1. Summary of policies implemented along the four-phase pandemic timeline

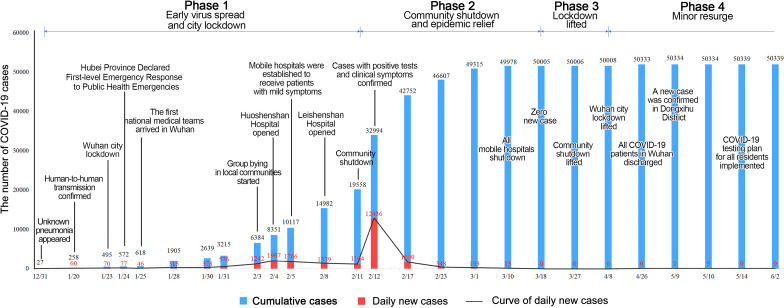

The evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan can be roughly divided into four phases along the timeline from 31 December 2019 to 1 June 2020 (Fig. 4 ): 1) early virus spread and city lockdown; 2) community shutdown and epidemic relief; 3) lockdown lifted; and 4) minor resurge. The COVID-19 policies implemented in each phase are detailed as follow.

Fig. 4.

Policies implemented along the pandemic timeline over four phases in Wuhan.

Phase 1: early virus spread and city lockdown (31 December 2019–10 February 2020)

On 31 December 2019, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (2020a) first announced that an unknown pneumonia appeared in Wuhan. Whether this pneumonia could be transmitted from human to human was unclear and without medical verdict. On 20 January 2020 though, the pneumonia, identified as a novel coronavirus disease, was confirmed as transmissible via human-to-human contact and named the COVID-19. Since then, policies to combat COVID-19 were proposed and urgently implemented by the Chinese central government, with the Wuhan lockdown as the first pilot site on 23 January 2020. Wuhan quickly entered the highest level of emergency with public transit fully shut down and city residents restricted within their local communities. The Chinese central government and the National Health Commission simultaneously initiated a range of policies to support Wuhan, including providing medical professionals from external regions, providing nucleic acid test kits, protective equipment, drugs, medical appliances, and other supplies that were most needed by healthcare systems. Unfortunately, given the large number of people moving from and to Wuhan before the formal announcement of the COVID-19 outbreak on 20 January 2020, the virus had already been transmitted, at a large scale, to other regions in China.

Phase 2: community shutdown and epidemic relief (11 February 2020–17 March 2020)

After a city-level lockdown, the virus began to transmit within local communities. In response to the community transmission, the local government began to implement a policy termed community shutdown management on 11 February 2020 as an additional measure to reduce the viral transmission within Wuhan. The Community shutdown management was not a single policy, but consisted of two significant initiatives: unifying the deployment of living materials and ensuring the testing, quarantining, and treatment for people in need (Wuhan Municipal Health Commission, 2020b). From 3 February 2020, the local government began to organise community-based group buying and the delivering of essentials (e.g. food and hygiene products). The delivery was organised by community workers and volunteers. Residents waited in queues to receive their supplies while maintaining social distancing. To remind local residents to regularly record their body temperature and report to community leaders (by completing a background-check questionnaire), WeChat (a popular mobile phone application for messaging and communication in China) groups were created. Residents with suspected symptoms (e.g. fever, cough and difficulty breathing) were transported to designated isolation sites and received nucleic acid tests along with a pulmonary computed tomography scan to diagnose for COVID-19. Based on the test result, patients would be sent to different places depending on their degree of infection—designated hospitals (for centralized treatment), mobile cabin hospital (for patients with mild symptoms), observation stations, or quarantining at home (Wu, Zhao, et al., 2020).

Phase 3: lockdown lifted (18 March 2020–8 April 2020)

On 18 March 2020, Wuhan, for the first time, had a zero increase of confirmed cases. Shortly after on 27 March 2020, the policy for the reopening of local communities and lifted lockdown orders was implemented. Under this policy, every community was required to collect the statistics for COVID-19 cases in the past 14 days and report that information to the local government. As of 27 March 2020, residents were allowed to go outside of local communities and travel within the city by keeping social distances and wearing masks. However, some community shutdown initiatives continued (e.g., community group buying and case reporting). Residents with suspected symptoms were transferred to hospitals and their close contacts were quarantined. On 8 April 2020, the public transit and road networks reopened, marking the entire city of Wuhan as fully open.

Phase 4: minor resurge (9 April 2020–2 June 2020)

After 9 April 2020, the transport system, production, work, and life in Wuhan had been fully restored. However, Wuhan encountered a minor resurge of sporadic cases that appeared and linked to asymptomatic infection. Meanwhile, the focus of COVID-19 policies shifted from comprehensive prevention and control to regular prevention and control (Steering Group of CPC Central Committee, 2020). A large-scale lockdown was not reinstated. Instead, a range of flexible policies were implemented, including shutting down communities with confirmed cases, lifting restrictions after quarantine, and helping the public quickly return to normal. Moreover, Wuhan residents were required to install and register a contact-tracing mobile application to obtain a health QR code, which enabled them to travel outside of the local community. The QR code of residents who have had close contact with COVID positive individuals would be marked as high risk, inhibiting their mobility to the outside of the community instantly.

4.2.2. Three key mechanisms for controlling community transmission

Based on the discussion of the aforementioned policies that were implemented in Wuhan and effectively diminished community transmission, we summarise three key mechanisms below to explain how such policy interventions impede community-level viral transmission.

Controlling the mobility of young population

The population under the age of 18 was observed to be significantly associated with viral transmission in the preceding quantitative analysis. The higher mobility rate of younger groups made them more likely to be exposed to the virus than the other age groups. Thus, infected individuals composing the population under 18 years old were more likely to transmit the virus within its incubation period. Specifically, individuals under 18 were more likely to be asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, which may have led to their lack of precautionary measures and awareness of the danger in spreading the virus. Their high mobility facilitates viral transmission to the elderly who are most vulnerable to being infected and more likely to suffer severe symptoms or mortality. For example, the Sanmin Community in Wuhan had 6590 permanent residents and is located 11 km away from the Huanan Seafood Market (reported to be the location where the earliest case appeared in Wuhan). The Sanmin Community was thought to be the centre of the epidemic's second wave. In the Sanmin Community, individuals from the younger population (age younger than 18) accounted for 18.19% of the total population, which was higher than the city average (16.93%). The five confirmed cases in the Sanmin Community were all asymptomatic and caused wider infection in surrounding communities. Thus, it is suggested that social restriction policies should be strictly implemented in the younger population (age younger than 18) if community transmission occurs given to the following two reasons. First, online teaching that can be mainly applied to young populations so they can stay at home for schooling which lowers the social cost of restricting their mobility. Second, if young populations were well controlled, the most vulnerable group (i.e., the elderly), will be less likely to be infected by the highly mobile younger ones as they are the main source of asymptomatic infections within local communities. Measuring one's body temperature has been the most widely adopted measure for detecting COVID-19, but it has been observed that the second wave of the pandemic in Wuhan was primarily caused by an asymptomatic group in which the presence of COVID-19 could not be confirmed by merely measuring these individuals' body temperature. Instead, effective and prompt nucleic acid tests, comprehensive body scans, and temperature checking should be used for COVID-19 diagnosis.

Community shutdown as a low-cost and small-scale initiative for virus control

The city-level lockdown implemented in Wuhan on 23 January 2020 was critical in curbing the virus' spreading, given that it successfully reduced the outflow of populations from Wuhan to other Chinese cities and also controlled the large-scale migration flow that would have occurred in the following Chinese New Year holiday, on January 25, 2020. However, the large-scale lockdown resulted in numerous social and economic costs, which led to this approach being less readily implemented in foreign cities due to differing urban governance systems and degrees of stringency with which policies are implemented (Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). Alternatively, the community shutdown management policy can be implemented as a low-cost and small-scale initiative for viral control due to its ability to effectively reduce the infection rate during pandemic's second phase in Wuhan. While the stringency of community shutdown was eased during the pandemic's third and fourth phases in Wuhan, this strategy can be implemented across a longer period to cope with minor resurges. Community shutdown could incorporate flexible initiatives such as delineating different levels of risk areas in urban space. Instead of implementing a large-scale lockdown, community shutdown would be a more efficient and manageable policy to curb viral spread on a small scale, with less social and economic costs.

Detailed plan for community shutdown management and service delivery

Wuhan's local government made a detailed plan to guide the community shutdown management and help residents cope with the restricted mobility and their new day-to-day lifestyles. To facilitate prompt and effective diagnosis of COVID-19, community-wide nucleic acid testing was organised in a timely manner, such that everyone was tested in the early phase. In the later phase of the pandemic though, this testing was only provided only in medium- or high-risk communities. Different levels of treatments would be decided based on people's contact tracing results, and treatment priority was given to those who had close contact with individuals confirmed to have COVID-19. Residents with different severities of infection were tested, isolated, transferred, or treated in different locations (e.g., designated hospitals, mobile cabin hospitals, observation stations). To better serve their residents, the local government organised group grocery purchasing efforts and delivered food along with other household essentials to the entrance of a community. Then, social workers and volunteers distributed these supplies door-to-door to residents according to their order requests. To remind residents to consistently measure their temperatures and to report the results to their community leaders, WeChat text groups were established among the residents. At the later stage of the epidemic, residents were required to install and register a contact-tracing mobile application to obtain a health code if they needed to go outside of the local community. If anyone had close contact with confirmed cases, their health codes would be quickly spotted and tracked. These individuals would not be allowed to leave their house and were required to quarantine for 14 days. If confirmed cases were identified within a local community, other residents in that community would not be allowed to go outside either. For most communities without cases, contact tracing by health code and mobile application is the most effective and economical method to eliminate any subtle resurgence.

5. Discussion

Our study contributes a number of novel findings by quantitatively examining the effect of community factors on viral transmission and qualitatively exploring the key mechanisms of how policy interventions can control viral spread in local communities. First, we delineated the period of COVID-19 transmission in Wuhan into four phases and found that active policy intervention is beneficial to epidemic prevention and control at all times. In particular, community shutdown management, as a supplement to the city-level lockdown, played an important role in curbing viral transmission at the local level. Second, the viral spread in local communities is irrelevant to the built environment of a community and its socioeconomic position but is related to its demographic composition. Specifically, groups under the age of 18 play an important role in viral transmission. There is an immediate implication that, although the elderly is more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and has a higher mortality rate, the mobility of the young population is more associated with the viral transmission in local communities. Third, the community serves as the basic unit for epidemic prevention and control. Once the community has been put on lockdown, how to ensure the daily life and medical care of all residents has become an important issue. The implementation of a series of community shutdown management initiatives (e.g., group buying, delivering supplies, and self-reporting of health conditions) is recommended from the experience of Wuhan.

The above novel and nuanced findings enrich the current scholarship in several ways. First, our study provides the quantitative evidence on the effect of community factors (e.g., built environment) on viral transmission that have not be covered in the existing studies (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Chinazzi et al., 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Kraemer et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020). Our finding that the built environment of a community (e.g., green spaces and parking spaces) does not play a crucial role in controlling virus spread. The reason for this finding may lie to the high transmissibility of COVID-19. Such new evidences about the relationship between the built environment and infectious diseases may help to guide through the prevention of new COVID-19 variants. Second, our study further confirms the relationship between community transmission and the age structure of residents, which extends the current findings at the national, provincial and municipal scale (e.g., Alon et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Kong et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020; Wu, Zhao, et al., 2020) to the community scale. Third, we delineated the progress and timeline of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, in relation to when, how, and to what extent policy interventions were implemented. In doing so, our study explains the practical experience of viral control and intervention within Wuhan that has been borrowed by other Chinese cities or can be compared to empirical studies in other countries (e.g., Dickson et al., 2020; Salje et al., 2020; Tobías, 2020; Yang et al., 2020). In addition to general medical measures revealed in existing studies (Chen et al., 2020; Djurović, 2020; Jiang & Luo, 2020; Tian et al., 2020), we suggest that more emphasis should be put on ensuring the supply of basic living materials and medical cares in the closed communities to minimize the impact of the closure on daily life of residents. Otherwise, a long-term community shutdown may lead to serious secondary disasters, such as delays in seeking medical attention for residents with other medical conditions, which requires special attentions.

Our findings also reveal the uniqueness of policies implemented in Wuhan in the community level—known as community shutdown management—which have been witnessed to be successful and effective in controlling and preventing viral transmission. It provides evidence to other cities and countries on which and when police implementations may be effective in viral control. Herein, we provide several directions for future policy implications. First, we would recommend that governments and public health authorities adopt the experiences from Wuhan with great cautions given to the different social institutions and management rules across geographic contexts, however, they could take the findings of our study as the evidence to guide through their policy making to fit into the local contexts. Although large-scale city lockdowns might be less practical for the countries and regions that lack the centralized power for supervision (e.g., DeFries et al., 2020; Dickson et al., 2020; Kraemer et al., 2020; O'Sullivan et al., 2020; Zhang, Litvinova, et al., 2020), community shutdown can be a more economical alternative that can be implemented flexibly in different contexts. Second, informing the public through social media platforms and mobile applications (e.g., WeChat) turned out to be an effective approach in disseminating pandemic information and supporting their lockdown lives with sufficient living materials. This approach can be readily implemented towards social media users living in other countries (e.g., establishing Facebook and Twitter community groups). Third, monitoring human mobility through mobile applications (e.g., scanning health QR code) can help with effectively contact tracing and ensuring that the public instant responds to potential infection, followed by timely testing. Such a method of monitoring can be applied to other countries to improve the efficiency of contact tracing (e.g., making phone calls manually) and reduce the labour and economic cost spent in contact tracing. Fourth, age-specific policies may play a significant role in community transmission of COVID-19. This conclusion is drawn not only because COVID-19 has a higher fatality rate for the elderly with underlying diseases, but also because the most effective way to control the transmission of COVID-19 is to control the direct contact between infected people, close contacts and uninfected people (as summarized in Zhang, Wang, et al., 2022; Harapan et al., 2020; AlTakarli, 2020; Lin et al., 2020). Considering the relatively low social cost of controlling the movement of minors and the elderly, it should be a priority for anti-epidemic policies.

There are several limitations in our study that can aid future studies in extending our findings. First, the primary COVID-19 data used in our study are limited by the sampling approach and location—covering only 386 communities in Wuhan. Thus, the data may not reveal information about community transmission in the urban fringes or rural areas where data are not available. Further studies can be extended to such areas using social surveys and questionnaires. Second, we used the built environment factors of green space, underground parking, and the age of buildings due to the availability of data in these categories. However, future studies can include more diverse built environment factors as defined by Liu et al. (2019) in the ‘5D’ dimensions: diversity, design, density, destination, and distance. Third, our study did not provide a comparison study of COVID-19 community transmission between different regions and countries. Such comparison studies can focus on how much the experience of policy implementation in one area can be applied to others in relation to effectiveness, timeline, and stringency. Fourth, our study does not account for the impact of urban resilience on the control and intervention towards COVID-19. Future studies can integrate the factor of urban resilience as an emerging topic in current urban studies into COVID-19 transmission studies. Such research can provide long-term policy suggestions on viral control and intervention by building resilient communities and cities that are prepared to combat epidemics and establishing systems in place for post-pandemic health planning, reconstruction and management.

6. Conclusion

The data of confirmed cases in the Wuhan communities provide us with good insight for understanding the community transmission of COVID-19. The conclusions are drawn by addressing two research questions we proposed in the begin: 1) What community factors are associated with viral transmission and 2) What are the key mechanisms behind anti-epidemic policy interventions. First, the viral spread in local communities is irrelevant to the built environment of a community and its socioeconomic position. In other words, the transmission of COVID-19 has little to do with the financial situation of families and the levels of local facilities. Second, younger population especially groups under the age of 18 play an important role in viral transmission. A reasonable guess is that young people have higher mobility than other groups. Third, community shutdown is a resilient and economic policy intervention when community transmission occurs. Its success depends on a good supply of living materials and medical cares for local residents to some extends. All the findings derive from the Wuhan data, which can be used for comparative urban research in different countries and regions.

With the ongoing pandemic and prevalence of multiple COVID-19 new variants, the mechanisms of community transmission and community management initiatives suggested in our study have potentials to be applied to other geographic contexts towards combatting against the resurgence of COVID-19 in the post-pandemic era. Furthermore, our findings can be employed to prevent and control future public health emergencies, such as a viral outbreak that may arise due to heightening extents of globalisation, urbanisation, and the human invasion of ecosystems.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhe GAO: Investigation, Resources, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original draft, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Siqin Wang: Methodology, Software, Visualisation, Writing-Original draft, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Jiang GU: Conceptualization, Writing-Original draft, Validation, Project administration. Chaolin GU: Supervision. Regina LIU: Proofreading.

References

- Adams-Prassl A., Boneva T., Golin M., Rauh C. The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on mental health: Evidence from the US. Economic Policy. 2020 doi: 10.17863/CAM.81910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alon T., Kim M., Lagakos D., VanVuren M. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. How should policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic differ in the developing world? (No. w27273) [Google Scholar]

- AlTakarli N.S. China’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak: A model for epidemic preparedness and management. Dubai Medical Journal. 2020;3(2):44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Amap Application programming interface of Amap. 2020. https://lbs.amap.com/ Available at.

- AnJuKe Chinese real estate transaction platforms. 2020. https://wuhan.anjuke.com/ Available at.

- Anselin L. Vol. 4. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. Spatial econometrics: Methods and models. [Google Scholar]

- Anselin L., Le Gallo J. Interpolation of air quality measures in hedonic house price models: Spatial aspects. Spatial Economic Analysis. 2006;1(1):31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Balmford B., Annan J.D., Hargreaves J.C., Altoè M., Bateman I.J. Cross-country comparisons of COVID-19: Policy, politics and the price of life. Environmental and Resource Economics. 2020;76(4):525–551. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee T., Nayak A. US county level analysis to determine if social distancing slowed the spread of COVID-19. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2020;44 doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth K.M., Pinkston M.M., Poston W.S.C. Obesity and the built environment. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(5):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byambasuren O., Cardona M., Bell K., Clark J., McLaws M.L., Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Official Journal of the Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada. 2020;5(4):223–234. doi: 10.3138/jammi-2020-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Mi Y., Chu Z., Zheng Y., Chen F., Liu Y. Demand analysis and management suggestion: Sharing epidemiological data among medical institutions in megacities for epidemic prevention and control. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science) 2020;25(2):137–139. doi: 10.1007/s12204-020-2166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Chen Y., Lian Z., Wen L., Sun B., Wang P., Pan G.… Correlation between the migration scale index and the number of new confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 cases in China. Epidemiology & Infection. 2020;148 doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6491):4. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche C., Garuccio J., Le A., Pinkston J., Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate: Study evaluates the impact of social distancing measures on the growth rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases across the United States. Health Affairs. 2020;39(7):1237–1246. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFries R., Agarwala M., Baquie S., Choksi P., Dogra N., Preetha G.S., Urpelainen J.… Post-lockdown spread of COVID-19 from cities to vulnerable forest-fringe villages in Central India. Current Science. 2020;119(1) [Google Scholar]

- Dickson M.M., Espa G., Giuliani D., Santi F., Savadori L. Assessing the effect of containment measures on the spatio-temporal dynamic of COVID-19 in Italy. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2020;101(3):1833–1846. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05853-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurović I. Epidemiological control measures and predicted number of infections for SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: Case study Serbia March–April 2020. Heliyon. 2020;6(6) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Wang S., Gu J. Identification and mechanisms of regional urban shrinkage: A case study of Wuhan City in the heart of rapidly growing China. Journal of Urban Planning and Development. 2021;147(1):05020033. [Google Scholar]

- Gatto M., Bertuzzo E., Mari L., Miccoli S., Carraro L., Casagrandi R., Rinaldo A. Spread and dynamics of the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy: Effects of emergency containment measures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(19):10484–10491. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004978117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover R.E., van Schalkwyk M.C., Akl E.A., Kristjannson E., Lotfi T., Petkovic J., Welch V.… A framework for identifying and mitigating the equity harms of COVID-19 policy interventions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2020;128:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P., Nelson M.C., Page P., Popkin B.M. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–424. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu C., Zhu J., Sun Y., Zhou K., Gu J. The inflection point about covid-19 may have passed. Science Bulletin. 2020;65(11) doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harapan H., Itoh N., Yufika A., Winardi W., Keam S., Te H., Mudatsir M.… Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A literature review. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2020;13(5):667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honein M.A., Christie A., Rose D.A., Brooks J.T., Meaney-Delman D., Cohn A., Williams I.… Summary of guidance for public health strategies to address high levels of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and related deaths, December 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(49):1860. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T., Wang S., Luo W., Zhang M., Huang X., Yan Y.…Li Z. Revealing public opinion towards COVID-19 vaccines with Twitter data in the United States: Spatiotemporal perspective. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23(9) doi: 10.2196/30854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T., Wang S., She B., Zhang M., Huang X., Cui Y.…Li Z. Human mobility data in the COVID-19 pandemic: Characteristics, applications, and challenges. International Journal of Digital Earth. 2021;14(9):1126–1147. [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Xu Y., Liu R., Wang S., Wang S., Zhang M.…Li Z. Exploring the spatial disparity of home‐dwelling time patterns in the USA during the COVID‐19 pandemic via Bayesian inference. Transactions in GIS. 2022;14(9):1126–1147. doi: 10.1111/tgis.12918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iddrisu W.A., Appiahene P., Kessie J.A. 2020. Effects of weather and policy intervention on COVID-19 infection in Ghana. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00106. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Luo L. Influence of population mobility on the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic: Based on panel data from Hubei, China. Global Health Research and Policy. 2020;5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00151-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapa S., Halamka J., Raskar R. Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 95, No. 7) Elsevier; 2020. Contact tracing to manage COVID-19 spread—Balancing personal privacy and public health; pp. 1320–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W.H., Li Y., Peng M.W., Kong D.G., Yang X.B., Wang L., Liu M.Q. SARS-CoV-2 detection in patients with influenza-like illness. Nature Microbiology. 2020;5(5):675–678. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0713-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer M.U., Yang C.H., Gutierrez B., Wu C.H., Klein B., Pigott D.M., Scarpino S.V.… The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6490):493–497. doi: 10.1126/science.abb4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuma D., Pradeepa R., Khawaja K.I., Hasan M., Siddiqui S., Mahmood S., Chambers J.C. 2020. Low uptake of COVID-19 prevention behaviours and high socioeconomic impact of lockdown measures in South Asia: Evidence from a large-scale multi-country surveillance programme. medRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Leung G.M., Tang J.W., Yang X., Chao C.Y., Lin J.Z., Sleigh A.C.… Role of ventilation in airborne transmission of infectious agents in the built environment-a multidisciplinary systematic review. Indoor Air. 2007;17(1):2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2006.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.F., Duan Q., Zhou Y., Yuan T., Li P., Fitzpatrick T., Zou H. Spread and impact of COVID-19 in China: A systematic review and synthesis of predictions from transmission-dynamic models. Frontiers in Medicine. 2020;7:321. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang S., Xie B. Evaluating the effects of public transport fare policy change together with built and non-built environment features on ridership: The case in South East Queensland, Australia. Transport Policy. 2019;76:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Luijten M.A., van Muilekom M.M., Teela L., Polderman T.J., Terwee C.B., Zijlmans J., Haverman L.… The impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and social health of children and adolescents. Quality of Life Research. 2021;30(10):2795–2804. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02861-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission The report of COVID-19 in China. 2020. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqtb/202002/261f72a74be14c4db6e1b582133cf4b7.shtml Available at:

- Oka T., Wei W., Zhu D. The effect of human mobility restrictions on the COVID-19 transmission network in China. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan D., Gahegan M., Exeter D.J., Adams B. Spatially explicit models for exploring COVID-19 lockdown strategies. Transactions in GIS. 2020;24(4):967–1000. doi: 10.1111/tgis.12660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papas M.A., Alberg A.J., Ewing R., Helzlsouer K.J., Gary T.L., Klassen A.C. The built environment and obesity. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2007;29(1):129–143. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirlinck M., Linka K., Costabal F.S., Kuhl E. Outbreak dynamics of COVID-19 in China and the United States. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2020;19(6):2179–2193. doi: 10.1007/s10237-020-01332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainisch G., Undurraga E.A., Chowell G. A dynamic modeling tool for estimating healthcare demand from the COVID19 epidemic and evaluating population-wide interventions. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;96:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X. Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Eurasian Geography and Economics. 2020;61(4–5):423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Salje H., Kiem C.T., Lefrancq N., Courtejoie N., Bosetti P., Paireau J., Cauchemez S.… Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. Science. 2020;369(6500):208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steering Group of CPC Central Committee Adhere to both prevention and release, strengthen normalization and precision prevention and control. 2020. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2020-02/21/c_1125604097.htm

- Sun G.Q., Wang S.F., Li M.T., Li L., Zhang J., Zhang W., Feng G.L.… Transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: Effects of lockdown and medical resources. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2020;101(3):1981–1993. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H., Liu Y., Li Y., Wu C.H., Chen B., Kraemer M.U., Dye C.… An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science. 2020;368(6491):638–642. doi: 10.1126/science.abb6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A. Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Science of the Total Environment. 2020;725 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Liu Y., Hu T. Examining the change of human mobility adherent to social restriction policies and its effect on COVID-19 cases in Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(21):7930. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Huang X., Hu T., Zhang M., Li Z., Ning H.…Li X. The times, they are a-changin’: Tracking shifts in mental health signals from early phase to later phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Zhang Z., Mo Y., Wang D., Ning B., Xu P., Qian C.… Recommendations for control and prevention of infections for pediatric orthopedics during the epidemic period of COVID-19. WorldJournal of Pediatric Surgery. 2020;3(1) doi: 10.1136/wjps-2020-000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F., Zhao S., Yu B., Chen Y.M., Wang W., Song Z.G., Zhang Y.Z.… A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., Leung K., Bushman M., Kishore N., Niehus R., de Salazar P.M., Leung G.M.… Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan,China. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(4):506–510. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuhan Bureau of Statistics Population survey in 2015. 2015. http://tjj.wuhan.gov.cn Available at:

- Wuhan Municipal Health Commission 2020. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/gsgg/202004/t20200430_1199576.shtml Available at.

- Wuhan Municipal Health Commission Interim measures for the prevention and control of epidemic of COVID-19 in Wuhan. 2020. http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/zwgk_28/zc/gfxwj/202011/t20201128_1520758.shtml available at.

- Yang H., Chen D., Jiang Q., Yuan Z. High intensities of population movement were associated with high incidence of COVID-19 during the pandemic. Epidemiology & Infection. 2020;148 doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J. Lessons from South Korea's COVID-19 policy response. The American Review of Public Administration. 2020;50(6–7):801–808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Litvinova M., Liang Y., Wang Y., Wang W., Zhao S., Yu H.… Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368(6498):1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Wang S., Hu T., Fu X., Wang X., Hu Y.…Bao S. Human mobility and COVID-19 transmission: A systematic review and future directions. Annals of GIS. 2022:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. Estimation of disease transmission in multimodal transportation networks. Journal of Advanced Transportation. 2020;2020(8898923) doi: 10.1155/2020/8898923. 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]