Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disproportionately impacted lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities. Many disparities mirror those of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS epidemic. These health inequities have repeated throughout history due to the structural oppression of LGBTQ+ people. We aim to demonstrate that the familiar patterns of LGBTQ+ health disparities reflect a perpetuating, deeply rooted cycle of injustice imposed on LGBTQ+ people. Here, we contextualize COVID-19 inequities through the history of the HIV/AIDS crisis, describe manifestations of LGBTQ+ structural oppression exacerbated by the pandemic, and provide recommendations for medical professionals and institutions seeking to reduce health inequities.

Keywords: LGBTQ+, COVID-19, health disparities, HIV/AIDS

This perspective describes the impact that COVID-19 has had on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer communities and how the history of this group’s advocacy from the HIV/AIDS epidemic can inform the care of this highly minoritized population.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disproportionately impacted lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) communities. The Movement Advancement Project is an independent nonprofit advocacy group committed to health equity. It summarized critical findings from a poll evaluating the impact of COVID-19 in United States (US) households [1], finding that LGBTQ+ families have less secure access to financial, medical, and educational resources than non-LGBTQ+ populations. Sixty-four percent of LGBTQ+ individuals stated they or a household member experienced employment loss compared to 45% of non-LGBTQ+ individuals. Additionally, 47% of LGBTQ+ individuals indicated severe concerns about severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) acquisition at work, compared with 28% of non-LGBTQ+ individuals. One in 4 LGBTQ+ households experienced challenges affording medical coverage, and 2 in 5 LGBTQ+ households experienced barriers to medical care, compared with 19% of non-LGBTQ+ households.

Few studies have highlighted disparities in LGBTQ+ communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. This population has long been subject to medical oppression and deprivation, as reflected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS crisis. This is the result of structural oppression. To call oppression structural is to recognize that disparities faced by a marginalized group are woven into the very fabric and systems core to our society. This includes access to healthcare, economic stability, social safety, and physical sovereignty. LGBTQ+ communities mobilized to disseminate this information and ignited biomedical innovation and healthcare activism that defined the national HIV response beginning in the 1980s. Here, we provide a history of the HIV/AIDS crisis, elucidate mechanisms by which LGBTQ+ health inequities occur, and describe recommendations for fostering LGBTQ+ health equity in the COVID-19 pandemic.

HISTORY OF THE HIV/AIDS CRISIS AND COVID-19: THE MARGINALIZED AND ENERGIZING LGBTQ+ POPULATIONS

The HIV epidemic has spanned 4 decades and provides rich historical context for the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. During the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, no drugs were available, and HIV infection had a nearly 100% mortality rate [2]. Today, biomedical advances have given us the optimism to foresee the end of the AIDS epidemic [3–5]. When HIV/AIDS was first described, it was referred to as the “gay plague” [2]. Stigma resulted in public indifference and governmental inaction. Then-president Ronald Reagan did not publicly acknowledge the epidemic until 1985, 4 years after the deaths had begun.

Lack of governmental AIDS response galvanized LGBTQ+ communities to adopt mutual aid and community-driven action strategies to care for the dying and disabled [6]. AIDS activists in New York City formed the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which disseminated the message “silence = death” through demonstrations, “die-ins,” media campaigns, and protests at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and National Institutes of Health [6–10].

Pushed by the tenacity of HIV/AIDS activists, scientific communities began to collaborate with activists by including people with HIV on clinical trial advisory boards, expediting therapeutic pipelines, and expanding access to emergency-use drugs [2]. HIV/AIDS advocacy radically transformed science and medicine in support of patient-centered care and highlighted the impact of structural racism and discrimination on healthcare and health outcomes [11, 12].

In contrast to the unseen HIV/AIDS pandemic, COVID-19 advocacy benefits from unprecedented international attention, leading to expeditious progress of clinical trials, therapeutics, and vaccine developments. One year into the pandemic, the FDA approved a drug for the treatment of COVID-19 and granted emergency use authorization for several therapeutics and 3 vaccines [13, 14]. The history of HIV/AIDS shows that far more sweeping changes are possible and necessary to eliminate the inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic [3, 15–17].

Activists have long stressed that community devastation from HIV/AIDS was not solely due to the unprecedented nature of the epidemic. Instead, injustices embedded within our social structures drove disparate morbidity, mortality, and the permanent public health crisis faced by minoritized communities [18, 19] during both the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics [2]. COVID-19 is an opportunity to further activism in the HIV/AIDS movement and enact longitudinal change that uniformly addresses disparities and preventable consequences of infectious diseases.

LGBTQ+ HEALTH DISPARITIES

Despite LGBTQ+ health being understudied, there is evidence demonstrating worse health outcomes and barriers to medical care in this population compared with nonminority groups [20]. These factors predispose LGBTQ+ communities to severe COVID-19 disease and higher mortality than the general population [21, 22]. A survey of 13 562 people in 138 countries conducted during April–May 2020 demonstrated that COVID-19 has had “a devastating impact” globally on LGBTQ+ communities [23]. The pandemic has interrupted vital services upon which LGBTQ+ people rely [24]. More than 20% of people with HIV indicated limited access to healthcare, with 7% at risk of running out of antiretrovirals. Even with tangible access to medical care, many feel unsafe going to a medical facility. One in 6 LGBTQ+ people and nearly a quarter of transgender people avoid medical care because of fear of discrimination [25].

Testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, decreased by 85% during the pandemic despite increased test positivity [26]. STI treatment, hormonal therapy, gender-affirming surgery, and HIV preventive care such as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), condoms, and self-testing have also decreased during the pandemic [27]. Such service cuts worsen preexisting healthcare inequities in Black, Latinx, transgender, gender-nonconforming, and nonbinary patient populations [28].

In both the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics, income has determined an individual’s ability to access needed therapeutics. Today, HIV PrEP is essential to end the ongoing epidemic, yet only 8% of US patients who could benefit from the drug receive it. Despite costing an estimated $6 per month to manufacture, PrEP is sold for prices as high as $2000 per month in the US [29]. Similar patterns exist in the manufacture and sale of COVID-19 drugs [30].

LGBTQ+ SOCIOECONOMIC AND WORKFORCE DISPARITIES

COVID-19 has increased unemployment and worsened housing instability [31], compounding LGBTQ+ socioeconomic disparities [9, 32, 33]. LGBTQ+ people earn less money on average and are subject to higher poverty rates than cisgender heterosexual people, with transgender men facing the highest poverty rates [34]. One in 5 LGBTQ+ adults lives in poverty. In California, >55% of LGBTQ+ adults live in poverty [35].

Unemployment rates are also higher within LGBTQ+ communities, translating to worse overall health outcomes, especially for those who receive care through employer health insurance plans [36]. LGBTQ+ people of color are more than twice as likely as white LGBTQ+ people to face discrimination in applying for jobs [25]. According to the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, up to 40% of LGBTQ+ people in the US work in industries affected by the pandemic, including healthcare, food service, education, and retail [37]. The high risk of COVID-19 exposure among front-line or essential workers has significantly increased physical, psychological, and financial burdens due to work, and health coverage loss. One in 3 LGBTQ+ adults reported a reduction in work hours due to the pandemic, compared to 1 in 5 non-LGBTQ+ adults [37, 38]. LGBTQ+ adults are less likely to have access to paid sick leave, which is not federally guaranteed in the US [39].

COVID-19 EXPOSURE AND THE LGBTQ+ HOMELESSNESS-INCARCERATION CYCLE

LGBTQ+ people are systematically denied access to the right to safe and adequate housing [40]. Shelters are often inaccessible to LGBTQ+ communities; this is particularly true for transgender people [41]. Beyond acceptance and respect, many have experienced violence, abuse, exploitation, and discrimination in shelters [42], aggravated by policy changes that allow sex-segregated shelters to discriminate against transgender people [43]. Up to 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ+ [44]. In the COVID-19 pandemic, LGBTQ+ youth have navigated discrimination and violence without the schools, community centers, libraries, and shelters they rely on for physical and psychological safety [45, 46].

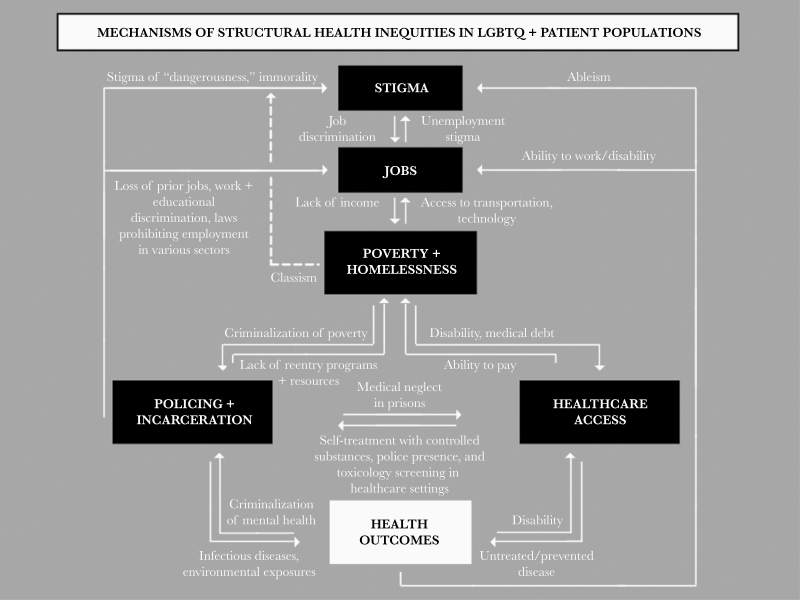

Homelessness and poverty among LGBTQ+ people are deeply intertwined with the mass incarceration of LGBTQ+ communities [40, 42]. People without housing are incarcerated at elevated rates, and many for crimes of existence, including sitting on the sidewalk, possessing an oversized cart, or rummaging through trash [43]. In tandem, people who have been incarcerated face stigma when applying for jobs and acceptance to academic institutions [47, 48]. Denials of employment and education create poverty and homelessness. This cycle demonstrates why oppression is structural. These oppressive constructs (homelessness and incarceration) are associated with poverty, food insecurity, healthcare deprivation, and social and cultural exclusion. These interconnected statuses form a web of oppressions from which it is nearly impossible to escape (Figure 1). These determinants of health are redundant and pervasive; this is why healthcare reform must be paired with sweeping changes to our social structures to achieve health equity.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of structural health inequities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) patient populations. Disparate health outcomes in the LGBTQ+ patient populations are fueled by structural inequities such as healthcare deprivation, policing, and criminalization of poverty and homelessness that are tied to employment instability and stigma. These forms of oppression are interconnected and redundant. Manifestations of these injustices include increased rates of untreated and preventable disease and disability, ultimately resulting in disparate health outcomes.

Jails and prisons impose substantial risks to LGBTQ+ health. LGBTQ+ youth are overrepresented in the juvenile justice system, making up nearly 20% of the juvenile justice population [49]. The confined nature of carceral facilities, often with limited access to hygienic products and delayed medical care, creates an environment highly permissive to disease spread [50, 51]. LGBTQ+ people are also overrepresented and disproportionately at risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission because of the nature of mandated prison labor. Incarcerated people, for example, were required to dig graves for and bury the deceased of both the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics in the nation’s largest mass grave (Hart Island, New York) [52–54]. In response to COVID-19, incarcerated people have functioned as front-line workers, producing pandemic-related items such as hand sanitizer for wages between $0.16 and $0.65 per hour. Ironically, prisons cannot use these products to mitigate transmission risks, as products with alcohol content are banned within carceral facilities [53, 55–57].

Incarcerated people experience disproportionately high rates of HIV, tuberculosis, and hepatitis C [50, 51]. Incarcerated people with HIV often face delays in treatment, receive low-quality care, and do not receive treatment for preexisting conditions [57–61]. In addition to infectious diseases, incarcerated populations face higher rates of hypertension, asthma, arthritis, and cervical cancer [62].

Incarceration rates are 3 times higher for LGBTQ+ adults than the general population [63]. More than 40% of incarcerated women are lesbian or bisexual. Prisons and jails incarcerate 21% of transgender women [64]. Carceral violence against LGBTQ+ people of color is staggering: 47% of Black transgender people are incarcerated at least once [65]. Furthermore, transgender people, especially Black transgender people, are profoundly absent from medical professions [66]. It is for this reason that advocates must recognize how this structural oppression limits representation, advocacy, and prioritization in data collection. The lack of analyses on the medical impacts of incarceration limits our ability to understand the extent to which mass incarceration is detrimental to the health of LGBTQ+ communities, but it is clear that an urgent public health response is necessary.

The disparities in COVID-19 prison-related health risks and outcomes showcase the multifaceted ways in which LGBTQ+ people are subject to medical oppression. Within carceral facilities, mechanisms include acute illness, longitudinal effects from environmental exposures, and reduced accessibility of medical care during and following imprisonment. Models suggest that imprisonment and mortality exhibit a dose-dependent relationship in which each year of incarceration results in a 2-year reduction in an individual’s life expectancy [67]. The growth of the incarceration rate has reduced the average US life expectancy by 1.79 years [68].

LGBTQ+ DATA COLLECTION: BENEFITS, METHODS, AND CAUTIONS

Difficulties understanding the demographics and mechanisms of LGBTQ+ health disparities extend beyond incarceration. Accurate health data in LGBTQ+ communities can be challenging due to the lack of uniform mechanisms to identify sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in healthcare settings [25–28]. Further research and insights are needed to inform strategies to ensure equity in our COVID-19 response. SOGI data collection has garnered increasing support in identifying individuals at risk, as this may provide valuable information on social determinants of health [69–71].

There is also potential for harm in collecting SOGI data, and we must remain cognizant of patient safety. Unauthorized protected health information (PHI) disclosures are common; these breaches impacted approximately 112 million Americans in 2015 [72]. Privacy breaches place patients at social and societal risk including stigma, anti-LGBTQ+ violence, and job loss [73]. Even Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)–compliant SOGI documentation can have devastating impacts on minoritized individuals. Patient medical records are frequently acquired by subpoena. SOGI and language describing patient behavior may endorse common anti-LGBTQ+ tropes (“noncompliant,” “nonconforming,” “difficult”) and may contribute to court bias and worse outcomes for LGBTQ+ patients [65, 74, 75]. Documentation of a pediatric patient’s SOGI, accessible to a child’s parents/guardians, produces alarming youth abuse and homelessness risks. Risks of SOGI data must be contextualized by lessons from the HIV/AIDS epidemic, during which anti-LGBTQ+ sentiments were expressed in a New York Times op-ed calling for people with HIV to be tattooed for public identification [76, 77]. Violence and acceptance of violence against LGBTQ+ remain rampant in our society.

SOGI documentation may come at the expense of patient safety and comfort. In 2020, the US Supreme Court determined that it is permissible to discriminate against transgender people in offering health services, providing care consistent with their gender identity, and covering transition-related medicine [78]. In the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 28% of transgender people reported being harassed in a medical setting, 19% were refused care, and 10% were sexually assaulted in a healthcare setting [79]. Anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes among providers are common, and there is a dearth of evidence to suggest that increased SOGI documentation would reduce provider discrimination.

When collecting SOGI data, medical professionals must provide an opt-in method in which LGBTQ+ patients may choose to disclose SOGI. Patients should dictate whether they consent to SOGI documentation in electronic health records and to whom this information is visible (eg, single practitioner, individual healthcare system, interinstitutional) [80]. In assessing COVID-19 LGBTQ+ health disparities, healthcare systems may wish to consider collecting anonymized aggregate patient SOGI data at the point of care when administering COVID-19 tests and vaccines for data collection.

SUMMARIZING MECHANISMS OF STRUCTURAL HEALTH INEQUITIES IN LGBTQ+ PATIENT POPULATIONS

Injustices faced by LGBTQ+ individuals define interconnected cycles of oppression involving stigma, job loss, poverty, homelessness, incarceration, and limited access to healthcare that impact health outcomes. Figure 1 describes these cycles that fuel each other. Stigma impacts jobs and education, causing poverty and homelessness, which feed incarceration and limited healthcare access. These result in untreated and preventable diseases that compromise health outcomes. Multilayered interventions will be necessary to break this cycle and improve how health outcomes can be improved in LGBTQ+ communities.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO REDUCE COVID-19 HEALTH DISPARITIES IN LGBTQ+ PATIENT POPULATIONS

Recommendation 1: Create Medical Environments Safe for LGBTQ+ Patient Populations

Creating safe environments requires recognizing and respecting patient pronouns, understanding gender as an identity distinct from sex assigned at birth, and being open to learning new LGBTQ+ identities and patient concerns. Providers should understand deep-rooted connections between LGBTQ+ identities and forms of structural violence (policing, prisons, denial of jobs, and social services) and consider how practices may affect patient comfort and safety in receiving medical care, including documentation of social/behavioral notes, ordering toxicology screens, and maintaining police presence in clinics and hospital settings. Health systems may benefit from partnerships with patient legal advocates [81].

Recommendation 2: Use Practice-Engaged, Patient-Centered Care to Better Understand How to Serve LGBTQ+ Patients

Large-scale COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites may offer exceptional opportunities to collect aggregated, anonymized SOGI data for health disparities analysis. SOGI survey questions should be indicated as optional and anonymized, as marginalized populations have cited individually identifiable data collection as a concern contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [82–84]. Understanding LGBTQ+ health requires providers to encourage patients to discuss access barriers they have faced in seeking medical care. These discussions require providers to acknowledge their knowledge gaps and actively seek to learn from the patients they treat. LGBTQ+ care competency may require training and tools for providers and clinic staff.

Recommendation 3: Remove Access Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccination and Testing in Marginalized Communities

COVID-19 vaccines and routine SARS-CoV-2 testing must be offered in clinics and communities. Common appointment-only vaccine administration strategies are inaccessible to patients without the time or technological resources to schedule appointments. Community-based vaccination and testing sites are needed to remove transportation barriers. Elimination of proof-of-residency requirements to receive COVID-19 vaccination is required for vaccine access by undocumented LGBTQ+ immigrants. It is also essential for vaccine access by transgender, gender-nonconforming, and gender-nonbinary patients, who may lack government identification matching correct names, genders, and addresses. Sufficient medical care and resources must be provided to people in congregate living facilities, including those held in carceral institutions. Initiatives to reduce jail and prison populations to halt the spread of SARS-CoV-2 have garnered broad endorsement [55].

Recommendation 4: Ensure Access to Comprehensive Medical Care Regardless of Immigration Status, Insurance Coverage, or Financial Resources

The healthcare community needs to provide medical care for preexisting conditions to treat and prevent COVID-19 effectively. Populations with limited healthcare access have expressed concern that they will not be offered future treatment for side effects as they would free vaccination [82]. Encouraging vaccination among marginalized populations requires dedication to treating patients before, during, and following COVID-19 interventions. Administration of equitable and comprehensive medical care, including essential primary care, will enable providers to promote and provide personal protective equipment, social distancing, and vaccination. This will foster continuity of care, equitable health outcomes, and reason for patients to trust medical institutions.

Recommendation 5: Communicate Healthcare Information in Accessible Formats

Side effects and questions about the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines have been cited as the primary reason for declining vaccination [85]. The Latinx community has voiced concern regarding whether vaccination outcomes may differ across demographics [82, 83, 86]. Lack of diversity in clinical trials has been a long-standing challenge [87–89] and was a paramount concern of HIV/AIDS activists in the 1980s–1990s [90]. This activism successfully increased racial and ethnic minorities’ representation in HIV drug trials and set expectations for demographic diversity in future FDA trials [91]. Patients from marginalized groups should be provided information regarding subgroup-specific data on vaccine side effects and efficacies. To effectively disseminate this information, point-of-care locations must be equipped with language translators. Written communications and infographics should be offered in multiple languages. Availability of comprehensive medical care (see recommendation 4) should be communicated through community centers, schools, libraries, and social media platforms. Outreach and enrollment workers are a necessary and evidence-based strategy [92].

Our recommendations seek to ensure access to care, patient safety, and effective dissemination of medical information to understand patients’ unique intersecting identities. Proposed areas of intervention are defined by the fundamental restructuring of healthcare provision to treat all patients comprehensively. We propose healthcare provider education and understanding of documented access barriers that have plagued LGBTQ+ communities for decades. These initiatives are limited in scope and insufficient to achieve equitable COVID-19 outcomes. Disproportionate job loss and workplace exposure, for example, will not be solved by these measures. We advocate for strengthened healthcare laws and policies to support LGBTQ+ individuals and families.

CONCLUSIONS

The HIV/AIDS epidemic illuminated failures of the medical community to care for LGBTQ+ patients adequately. COVID-19 has continued to expose medical and societal inequities that we have yet to acknowledge or mobilize resources to solve. It is crucial to note that these outcomes—including greater rates of COVID-19, underemployment, poverty, and adverse health outcomes—are akin to symptoms of an underlying disease.

Combating such systems of oppression is complex. Even when equipped with data, our efforts to achieve health equity are inhibited by a dire lack of representation of marginalized communities in medical careers and policy. This lack of representation renders data utility limited, as results are interpreted primarily by those without experience navigating core foundations of structural violence, including poverty, homelessness, incarceration, and medical neglect. Because of the extent to which diversity and representation are absent from medicine, perhaps the most crucial lesson to be learned from the HIV/AIDS epidemic is the activists’ demand of “nothing about us without us” [93], that no policy should be decided without representation of the group impacted by that policy. Healthcare providers need education about medical disparities and social determinants of health that affect LGBTQ+ communities. Healthcare providers should empower patients for whom injustices are most pronounced to lead educational initiatives. When we seek to learn from patients, we must remain mindful of exacerbated barriers to health faced by those with additional marginalized identities; diversity in consulted patient groups is paramount. These forms of diversity include gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, age, religion, immigration status, housing status, socioeconomic status, disability, geographic distribution, education, and parental status. Our responsibility is to encourage marginalized individuals to pursue medical careers and provide them with the necessary support.

We should aspire to earn the trust of our LGBTQ+ patients and the privilege of learning from them. This requires universal adoption of inclusive practices, including addressing patients by their correct names and pronouns, creating intake forms and an office environment that recognizes LGBTQ+ identities, provider knowledge of LGBTQ+-specific medical care, and provider comfort with diverse sexual and gender identities, orientations, practices, and opinions [94]. Actions by and disseminated messages from healthcare providers and the healthcare community should demonstrate that diverse patients are heard, are valued, and will uniformly receive the highest standard of care. Individuals, clinicians, and organizations must ensure equitable administration of medical care. In tandem, we must amplify our patients’ voices, experiences, and guidance essential to understanding what it means to serve this patient population faithfully and what we must change to do so.

The Roles and Challenges of LGBTQ+ Providers in the Infectious Diseases Workforce

Thomas Fekete, MD, MACP, FIDSA

Chair, IDSA Foundation

The 5 June 1981 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) described 5 gay men with pneumocystis pneumonia and other unusual opportunistic infections. This began the first public reckoning with the AIDS pandemic, which has to date killed >30 000 000 people worldwide and continues to kill more than half a million people a year. For those of us who specialize in the care of people with infectious diseases (ID), this changed everything. The early years of the HIV era were challenging because the cause was unknown, it was highly lethal, early diagnosis was impossible, there were no effective treatments, and it preferentially affected minority and marginalized communities. The year 1981 was also pivotal for gay men worldwide since this new infection spread quickly and resulted not only in excess death but also increased stigma.

Even before 1981, a mysterious disease affecting gay men had been rumored for a few years. This was known to clinicians with many gay men in their practice, and some of these doctors were, themselves, gay. Even prior to the discovery of HIV infection, there were clinics around the US, sometimes open in the evenings, that largely served gay men. These clinics varied in their mission, but they were usually geared to screening for and treating sexually transmitted infections. These clinics were often staffed by volunteers including medical students and residents who were members of the local gay community. In some instances, these doctors pursued training in ID. It is impossible to know how many LGBTQ providers were members or fellows of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)/HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) before the 1980s, but there was clearly a mutually beneficial relationship for LGBTQ providers and the organization.

It was clear from the beginning that treatment of people with HIV would require an openness to understanding sexuality. For many LGBTQ physicians, it was helpful to be open about their own orientation to maintain credibility with their patients and to advocate for resources and compassion within the larger medical community. This stance could be a threat to their practices since some patients felt threatened by even a visit to a potentially HIV-infected provider. It is hard to conceive that it took 4 years from the 1981 MMWR announcement to have a blood test for HIV.

Much of organized medicine was slow to accept the care of patients with HIV. In some parts of the country, especially remote rural areas, there were few providers willing or able to provide even basic HIV medical care. Fear of contagion was widespread. As an example, even in our urban HIV clinic, a patient with AIDS brought a homemade cake to clinic and there was an uncomfortable conversation about whether clinic staff would be willing to eat it. A network of clinicians including primary care providers and specialists formed the HIVMA under the umbrella of the IDSA. IDSA/HIVMA (hereafter “IDSA”) was also in dialogue with the public on matters relevant to testing and treatment of HIV, trying to deal with fear and stigma and provide scientifically sound screening and treatment. IDSA was welcoming to members and fellows of sexual minority communities. This is not to say that the ID medical community was fully “woke” in the 1980s, but an important set of steps was taken to protect our members and the public. In some medical centers, the need to care for patients with complications of HIV was contrasted with a concern about being seen as an institution that might accidentally expose other patients or providers to infection. To some extent the sympathy of “innocent victims” such as Ryan White and the establishment of national studies of HIV treatment such as the AIDS Clinical Trials Group CTG and Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS in prestigious medical centers were keys to reducing institutional stigma. But the uncomfortable reality is that many patients struggled to find compassionate and competent care, especially in the era before reliable HIV suppressive medications.

Being willing to practice in communities where HIV was prevalent was frightening for some providers, and seeing IDSA members use the best science to protect themselves while advocating for their patients set a powerful example, as discretion and a nonjudgmental approach have always been vital attributes of ID clinicians. In the 1980s and 1990s, ID doctors were often approached by their friends or colleagues regarding their anxiety about HIV and personal concerns about sexually transmitted infection, highlighting, again, the role of ID doc as the “clinician’s clinician.”

The larger social backdrop for the early years of the HIV pandemic is relevant since the US government had become more conservative with the election of Ronald Reagan. While Reagan offered assurance of vaccine development, his administration was reluctant to advance policies that could have diminished the spread of HIV. For gay people who lived through the 1980s, this lack of leadership is still unforgiveable. Currently there is a strong healthcare infrastructure around HIV and sexually transmitted infections, and this is well aligned with the needs of the LGBTQ community. But there is also a demand for primary care and specialty services for LGBTQ individuals, especially in rural areas where there may not be a wide range of providers. In the realm of medical education, it is important to remember these needs and not to present LGBTQ folks only through the lens of ID.

Things are much better now for most but not all people. Anyone attending an IDSA meeting would be unlikely to find overt homophobia. In fact, many young people ask, why focus on equity issues for LGBTQ people when there is still work to be done in other areas of inclusion and diversity? However even in 2021, there are several reasons why IDSA should continue to address and review its stance on LGBTQ issues, as follows.

First, even now, many young health professionals are worried about being open in their sexuality as they enter medical school, residency, or the job market. For many LGBTQ people, the battles are over, but some still experience discrimination. It may be hard to find someone who admits to being homophobic, but there can be uncomfortable conversations or jokes that make the workplace unsafe or, at least, awkward. This behavior can also come from nonphysicians or from patients, enhancing the vulnerability of the LGBTQ provider. This can make being “out” at work more difficult and that, in turn, can lead to stress and burnout.

Second, politics can be tribal. This makes it potentially awkward to try to work closely with or trust people of different backgrounds. Keeping political discourse out of the workplace is nigh impossible. In some contexts, it is necessary to keep defending one’s right to exist and to have a normal personal and family life. This is a problem for many minorities, but the ability to hide sexual orientation is a double-edged sword in this setting. LGBTQ people who cannot or choose not to be subtle about their identity should have access to all privileges that are available, but it is hard to determine if this ideal is being met. Implicit discrimination and even internalized homophobia can still be present and powerful.

Third, acceptance for various parts of the LGBTQ community can be variable. Even in liberal areas, there is prejudice and violence against transgender people. For transgender people of color, this problem is magnified further. When popular figures such as J. K. Rowling openly question the existence of trans identity, there is cover for further discrimination. Pennsylvania’s Secretary of Health, Dr Rachel Levine, is a transgender woman who has conducted herself in an exemplary and professional manner and has been nominated as US Assistant Secretary of Health. But this does not stop regular manifestations of disrespect that flow from her status, including one from a Pennsylvania state legislator in January 2021. So even professional accomplishment is not protective.

Fourth, some LGBTQ people face rejection and discrimination from within their families. This can lead to homelessness and suicidality in gay youth, but it can also be a lifelong stress for many adults. Having a safe harbor in professional life can mitigate that stress, but a hostile work environment can aggravate it.

Since 1981, there have been many aspects of the “culture wars” that have called into question the equality and humanity of LGBTQ people. The long fight for marriage equality in the US was debated again and again in legislatures before being narrowly settled by the Supreme Court. There is ample reason to believe that the current state of affairs could be reversed by a less accepting Court. In the meantime, LGBTQ people had to structure complicated financial instruments to achieve a simulacrum of marriage and often were not allowed to visit partners in the hospital or to get custody of children after the death of a partner, etc. But as awful as these things are for individuals, it was clear that many referenda on marriage equality were designed to mobilize conservative forces. This was used to advance an agenda hostile to reproductive freedom and personal expression and often ran counter to the ideals of inclusion and diversity in general. It is hard to decide which is worse: an animus against LGBTQ individuals or the cynical manipulation of homophobia to advance a political agenda.

Being against discrimination is easy and yet it is still very important for organizations to make explicit their promise to evaluate people based only on their qualifications. On a personal level, I have never experienced any sense of rejection or inequality by my colleagues at work or by the IDSA. I have had occasion to see other LGBTQ people embraced by the Society, and to have their partners and/or spouses warmly welcomed as was mine. But there are still subtle barriers out there. When traveling internationally, it can still be hard for same-sex couples to get equal treatment. This is especially a concern when one of the partners is not American and thus subject to even greater scrutiny when reentering the country.

IDSA and IDSA Foundation are inclusive and accepting organizations. This is vital for people to know before they join so they can be free to be themselves. It is also important for our organizations to reach out and advocate for acceptance and nondiscrimination for all minority groups since all have been under some degree of attack, rejection, or marginalization since the US was founded. The 14th, 15th, 19th, 24th, and 26th amendments to the US Constitution all address the right to vote, and it was just over 100 years ago that women won the right to vote! But voting, as important as it is, does not reflect the speed bumps that affect day-to-day life. No one person can speak for the LGBTQ community, and like other minority communities its needs and priorities are subject to change. But I believe that as a matter of policy, the IDSA and IDSA Foundation should be vocal in support of human rights in the US and abroad, that they should strive for LGBTQ nondiscrimination, and that they create safe spaces for members of sexual minorities—especially those without or with limited protection. My pride in IDSA is strong and I know that the needs of sexual minorities are valued, as are those of other underrepresented minorities (and of course, women) in all aspects of the organization. I believe that our overall success will be judged by a commitment to fairness across the board even when it is not easy or convenient. IDSA can provide leadership and set an example as it has for years with complete representation in growing a diverse and healthy ID workforce to better serve the people and public health of the nation.

Notes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Movement Advancement Project. The disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on LGBTQ households in the U.S.: results from a July/August 2020 national poll. 2020. https://www.lgbtmap.org/file/2020-covid-lgbtq-households-report.pdf. Accessed 1 February 2021.

- 2. Fauci AS, Lane HC. Four decades of HIV/AIDS—much accomplished, much to do. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edelman EJ, Aoun-Barakat L, Villanueva M, Friedland G. Confronting another pandemic: lessons from HIV can inform our COVID-19 response. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:1977–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Quinn KG, Walsh JL, John SA, Nyitray AG. “I feel almost as though I’ve lived this before”: insights from sexual and gender minority men on coping with COVID-19. AIDS Behav 2020; 25:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Small E, Sharma BB, Nikolova SP. Covid-19 and gender in LMICs: potential lessons from HIV pandemic. AIDS Behav 2020; 24:2995–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matthews DD. Leveraging a legacy of activism: Black Lives Matter and the future of HIV prevention for black MSM. AIDS Educ Prev 2018; 30:208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coates TJ. The fight against HIV is a fight for human rights: a personal reflection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 82(Suppl 2):91–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Curran JW. Activism combatting AIDS. Am J Public Health 2017; 107:1196–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earnshaw VA, Rosenthal L, Lang SM. Stigma, activism, and well-being among people living with HIV. AIDS Care 2016; 28:717–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rabkin JG, McElhiney MC, Harrington M, Horn T. Trauma and growth: impact of AIDS activism. AIDS Res Treat 2018; 2018:9696725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med 2019; 45:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. The Lancet HIV. Racial inequities in HIV. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Connors M, Graham BS, Lane HC, Fauci AS. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: much accomplished, much to learn. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174:687–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA issues emergency use authorization for third COVID-19 vaccine. Silver Spring, MD: FDA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kullar R, Marcelin JR, Swartz TH, et al. . Racial disparity of coronavirus disease 2019 in African American communities. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:890–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salerno JP, Williams ND, Gattamorta KA. LGBTQ populations: psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12:239–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tan TQ, Kullar R, Swartz TH, Mathew TA, Piggott DA, Berthaud V. Location matters: geographic disparities and impact of coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis 2020; 222:1951–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. AIDS history research: new ArchiveGrid available. AIDS Treat News 2006; 418:4–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keefe RH, Lane SD, Swarts HJ. From the bottom up: tracing the impact of four health-based social movements on health and social policies. J Health Soc Policy 2006; 21:55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ard K, Makadon HJ.. Improving the health care of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people: understanding and eliminating health disparities. Boston, MA: Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Phillips Ii G, Felt D, Ruprecht MM, et al. . Addressing the disproportionate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and gender minority populations in the United States: actions toward equity. LGBT Health 2020; 7:279–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruprecht MM, Wang X, Johnson AK, et al. . Evidence of social and structural COVID-19 disparities by sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in an urban environment. J Urban Health 2021; 98:27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lamtontagne E DT, Howell S, et al. . COVID-19 pandemic increases socioeconomic vulnerability of LGBTI+ communities and their susceptibility to HIV. In: 23rd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2020), Virtual, 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rao A, Rucinski K, Jarrett B, Ackerman B, et al. . 2020. Global interruptions in HIV prevention and treatment services as a result of the response to COVID-19: results from a social media-based sample of men who have sex with men. In: 23rd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2020), Virtual, 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Public Radio, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Discrimination in America: experiences and views of LGBTQ Americans.https://legacy.npr.org/documents/2017/nov/npr-discrimination-lgbtq-final.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2021.

- 26. Krakower DS, Solleveld P, Levine K, Mayer KH. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on HIV preexposure prophylaxis care at a Boston community health center. In: 23rd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2020), Virtual, 6–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herman JL, O’Neill K.. Vulnerabilities to COVID-19 among transgender adults in the U.S. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. 2020. The economic impact of COVID-19 on the LGBTQ community. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/COVID19-EconomicImpact-IssueBrief-042220.pdf?_ga=2.169186401.1174201493.1589206693-124555597.1585079069. Accessed 1 February 2021.

- 29. Kay ES, Pinto RM. Is insurance a barrier to HIV preexposure prophylaxis? clarifying the issue. Am J Public Health 2020; 110:61–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wise J. Remdesivir: US purchase of world stocks sparks new “hunger games,” warn observers. BMJ 2020. 370:m2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chatterjee S, Biswas P, Guria RT. LGBTQ care at the time of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2020; 14:1757–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Making admission or placement determinations based on sex in facilities under community planning and development housing programs. Washington, DC: Office of the Federal Register, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morton MH, Dworsky A, Matjasko JL, et al. . Prevalence and correlates of youth homelessness in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2018; 62:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. James S. Coronavirus economy especially harsh for transgender people. New York Times, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/16/us/coronovirus-covid-transgender-lgbtq-jobs.html. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Badgett MVL, Choi SK, Wilson BDM.. LGBT poverty in the United States. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Charlton BM, Gordon AR, Reisner SL, Sarda V, Samnaliev M, Austin SB. Sexual orientation-related disparities in employment, health insurance, healthcare access and health-related quality of life: a cohort study of US male and female adolescents and young adults. BMJ Open 2018; 8:e020418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. The lives and livelihoods of many in the LGBTQ community are at risk amidst COVID-19 crisis. 2020. https://hrc-prod-requests.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/files/assets/resources/COVID19-IssueBrief-032020-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2021.

- 38. Wypler J, Hoffelmeyer M. LGBTQ+ farmer health in COVID-19. J Agromedicine 2020; 25:370–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Human Rights Campaign Foundation. 2018 U.S. LGBTQ paid leave survey. 2018. https://assets2.hrc.org/files/assets/resources/2018-HRC-LGBTQ-Paid-Leave-Survey.pdf?_ga=2.8068666.907999101.1612204424-2107794699.1612204424. Accessed 1 February 2021.

- 40. McCann E, Brown M. Homelessness among youth who identify as LGBTQ+: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2019; 28:2061–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McCann E, Brown MJ. Homeless experiences and support needs of transgender people: a systematic review of the international evidence. J Nurs Manag 2021; 29:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pedrosa AL, Bitencourt L, Fróes ACF, et al. . Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol 2020; 11:566212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. National Homelessness Law Center. Housing not handcuffs: ending the criminalization of homelessness in U.S. cities. 2019. https://nlchp.org/housing-not-handcuffs/. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waguespack D, Ryan B.. State index on youth homelessness. Washington, DC: True Colors United and the National Homelessness Law Center, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. NBC New York. Covenant house gears up for surge in runaway youth. 2020. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/covenant-house-gears-up-for-surge-in-runaway-youth/2431831/. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Green A, Price-Feeny M.. LGBTQ youth face unique challenges amidst COVID-19. Boston, MA: Harvard Medical School Center for Primary Care,2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gillespie S, Batko S;. Urban Institute. Five charts that explain the homelessness-jail cycle—and how to break it. 2020. https://www.urban.org/features/five-charts-explain-homelessness-jail-cycle-and-how-break-it. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Couloute L. Getting back on course: educational exclusion and attainment among formerly incarcerated people. Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative,2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Annie E. Casey Foundation. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in the juvenile justice system: a guide to juvenile detention reform. Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation,2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Séraphin MN, Didelot X, Nolan DJ, et al. . Genomic investigation of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis outbreak involving prison and community cases in Florida, United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018; 99:867–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. Am J Public Health 2002; 92:1789–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hennigan W. Lost in the pandemic: inside New York City’s mass graveyard on Hart Island. TIME 2020. https://time.com/5913151/hart-island-covid/. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gross D. The transformation of Hart Island. New Yorker 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-local-correspondents/the-transformation-of-hart-island. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 54. New York City Council. Hart Island: the city cemetery. 2018. https://council.nyc.gov/data/hart-island/. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice. Advocates demand people in New York’s jails and prisons be released, not exploited to manufacture hand sanitizer, amid COVID-19 concerns. Brooklyn, NY: Katal Center for Equity, Health, and Justice, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cuomo AM. At novel coronavirus briefing, Governor Cuomo announces state will provide alcohol-based hand sanitizer to New Yorkers free of charge. 2020. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/novel-coronavirus-briefing-governor-cuomo-announces-state-will-provide-alcohol-based-hand. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Carrega C, ABC News. Nearly 100 prison inmates in NY to produce 100K gallons of hand sanitizer weekly. 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/health/prison-inmates-ny-produce-100k-gallons-hand-sanitizer/story?id=69501815. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Loeliger KB, Meyer JP, Desai MM, Ciarleglio MM, Gallagher C, Altice FL. Retention in HIV care during the 3 years following release from incarceration: a cohort study. PLoS Med 2018; 15:e1002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hawks LC, McGinnis KA, Howell BA, et al. . Frequency and duration of incarceration and mortality among US veterans with and without HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020; 84:220–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bose S. Demographic and spatial disparity in HIV prevalence among incarcerated population in the US: a state-level analysis. Int J STD AIDS 2018; 29:278–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Remien RH, Bauman LJ, Mantell JE, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to engagement of vulnerable populations in HIV primary care in New York City. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(Suppl 1):S16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health & Justice 2013; 1:3. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Khan MR, McGinnis KA, Grov C, et al. . Past year and prior incarceration and HIV transmission risk among HIV-positive men who have sex with men in the US. AIDS Care 2019; 31:349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ledesma E, Ford CL. Health implications of housing assignments for incarcerated transgender women. Am J Public Health 2020; 110:650–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. National Center for Transgender Equality. LGBTQ people behind bars: a guide to understanding the issues facing transgender prisoners and their legal rights. 2018. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/TransgenderPeopleBehindBars.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fields EL, Long A, Silvestri F, et al. . #ProjectPresence: highlighting black LGBTQ persons and communities to reduce stigma: a program evaluation. Eval Program Plann 2021:101978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Patterson E. The dose-response of time served in prison on mortality: New York State, 1989–2003. Am J Public Health 2013; 103:523–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wildeman C. Incarceration and population health in wealthy democracies. Criminology 2016; 54:360–82. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Grasso C, Goldhammer H, Funk D, et al. . Required sexual orientation and gender identity reporting by US health centers: first-year data. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:1111–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haider A, Adler RR, Schneider E, et al. . Assessment of patient-centered approaches to collect sexual orientation and gender identity information in the emergency department: the Equality Study. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1:e186506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Patel K, Lyon ME, Luu HS. Providing inclusive care for transgender patients: capturing sex and gender in the electronic medical record. J Appl Lab Med 2021; 6:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Koch DD. Is the HIPAA security rule enough to protect electronic personal health information (PHI) in the cyber age? J Health Care Fin 2017; 43. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lee LM. Ethics and subsequent use of electronic health record data. J Biomed Inform 2017; 71:143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Parker CM, Hirsch JS, Philbin MM, Parker RG. The urgent need for research and interventions to address family-based stigma and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth. J Adolesc Health 2018; 63:383–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Movement Advancement Project. Equality maps: foster and adoption laws. 2015. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/foster_and_adoption_laws. Accessed 30 July 2021.

- 76. Sember R, Gere D. “Let the record show”: art activism and the AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health 2006; 96:967–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fox DM. AIDS and the American health polity: the history and prospects of a crisis of authority. Milbank Q 1986; 64:7–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Department of Health and Human Services. HHS finalizes rule on section 1557 protecting civil rights in healthcare, restoring the rule of law, and relieving americans of billions in excessive costs. Washington, DC: HHS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL.Keisling M.. Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force,2011. [Google Scholar]

- 80. UC Davis Health. LGBT questions in electronic health records. Sacramento, CA: UC Davis Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Vanjani R, Martino S, Reiger SF, et al. . Physician-public defender collaboration—a new medical-legal partnership. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2083–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Artiga S, Ndugga N, Pham O.. Immigrant access to COVID-19 vaccines: key issues to consider. San Francisco, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Heffernan O. Misinformation is harming trust in the COVID vaccine among Latinos in New York. New York: Documented, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Visram T. How will undocumented immigrants get the COVID-19 vaccine? 2021. https://www.fastcompany.com/90595912/how-will-undocumented-immigrants-get-the-covid-vaccine. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination—United States, September and December 2020. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kaiser Family Foundations. KFF Health Tracking Poll/ KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor December 2020. San Francisco, CA. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Topline-KFF-COVID-19-Vaccine-Monitor-December-2020.pdf. Accessed 29 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Borno HT, Zhang S, Gomez S. COVID-19 disparities: an urgent call for race reporting and representation in clinical research. Contemp Clin Trials Commun 2020; 19:100630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Swartz TH, Titanji B. Deconstruct racism in medicine—from training to clinical trials. Nature 2020; 583:202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mak WW, Law RW, Alvidrez J, Pérez-Stable EJ. Gender and ethnic diversity in NIMH-funded clinical trials: review of a decade of published research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2007; 34:497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Bass SB, D’Avanzo P, Alhajji M, et al. . Exploring the engagement of racial and ethnic minorities in HIV treatment and vaccine clinical trials: a scoping review of literature and implications for future research. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2020; 34:399–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hubbard J. United in anger: a history of ACT UP [film]. 2012. https://www.unitedinanger.com/. Accessed 30 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kaiser Family Foundation. Connecting eligible immigrant families to health coverage and care: key lessons from outreach and enrollment workers. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Charlton JI. Nothing about us without us: disability oppression and empowerment. Oakland: University of California Press,2000. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Deutsch MB, Green J, Keatley J, Mayer G, Hastings J, Hall AM; World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group . Electronic medical records and the transgender patient: recommendations from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health EMR Working Group. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013; 20:700–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]