Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia. AD brain pathology starts decades before the onset of clinical symptoms. One early pathological hallmark is blood-brain barrier dysfunction characterized by barrier leakage and associated with cognitive decline. In this review, we summarize the existing literature on the extent and clinical relevance of barrier leakage in AD. First, we focus on AD animal models and their susceptibility to barrier leakage based on age and genetic background. Second, we re-examine barrier dysfunction in clinical and postmortem studies, summarize changes that lead to barrier leakage in patients and highlight the clinical relevance of barrier leakage in AD. Third, we summarize signaling mechanisms that link barrier leakage to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in AD. Finally, we discuss clinical relevance and potential therapeutic strategies and provide future perspectives on investigating barrier leakage in AD. Identifying mechanistic steps underlying barrier leakage has the potential to unravel new targets that can be used to develop novel therapeutic strategies to repair barrier leakage and slow cognitive decline in AD and AD-related dementias.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Blood-brain Barrier, Barrier Dysfunction, Barrier Leakage, Neurovasculature, Cerebrovasculature

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Alzheimer’s Disease: Background, Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Current Challenges

Background.

More than 100 years ago, German physician Dr. Alois Alzheimer described “a peculiar disease” that was later named after him (Alzheimer’s disease, AD). Alzheimer defined the disease as presenile dementia with plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) as the characteristic pathological hallmarks (Alzheimer, 1906, 1907; Fischer, 1907, 1910). “Dementia” is a general term that refers to loss of cognitive function such as attention, memory, communication, problem-solving, visual perception, and self-management (“Dementia Fact Sheet,”). AD is the most common type of dementia and an irreversible, progressive disease that turns patients into helpless individuals depending on others for performing everyday activities (“Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet,”). In the initial stages, AD patients experience agitation, anxiety, loss of appetite, mood swings, sleep disturbances, and, importantly, a decline in their cognitive abilities (“Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet,”; Ehrenberg, et al., 2018). With the progression of the disease, agitation in patients increases, and episodes of memory loss become more frequent. These episodes come with reduced executive function, deficits in visuospatial skills, as well as speech problems. Anxiety, loss of appetite, mood swings, and sleep disturbances tend to subside at this advanced AD stage. In the late and more severe stages of AD, delusions and hallucinations set in, and patients become vegetative with minimal activity. Based on the age at diagnosis, AD is classified as early-onset or late-onset AD. Specifically, early-onset AD starts between the ages of 30 – 60 years and is due to familial genetic mutations. In contrast, late-onset AD begins after the age of 60 due to various unknown environmental and lifestyle factors.

Diagnosis.

A proper AD diagnosis involves a series of cognitive, imaging, and laboratory tests (Sabbagh, Lue, Fayard, & Shi, 2017). Usually, a clinician recommends cognitive evaluation if the patient or caregiver reports memory-related concerns. In this evaluation, the patient is assessed through one or more standardized tests such as the Mini-Cognitive Assessment, the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS), a Clinical Dementia Rating, or the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The clinician may also perform neurological exams and metabolic tests to exclude other causes that could impair cognition. Further assessment involves looking for amyloid and tau deposits in the brain with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker analysis, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET). Despite all these state-of-the-art diagnostic methods, a final, definitive diagnosis of AD is based on clinical symptoms, neuropathological markers, and the distribution of plaques and tangles and can only be made postmortem by a team of neuropathologists, neuropsychologists, and neurologists (Braak & Braak, 1991; Ehrenberg, et al., 2018; Nelson, et al., 2012).

Pathophysiology.

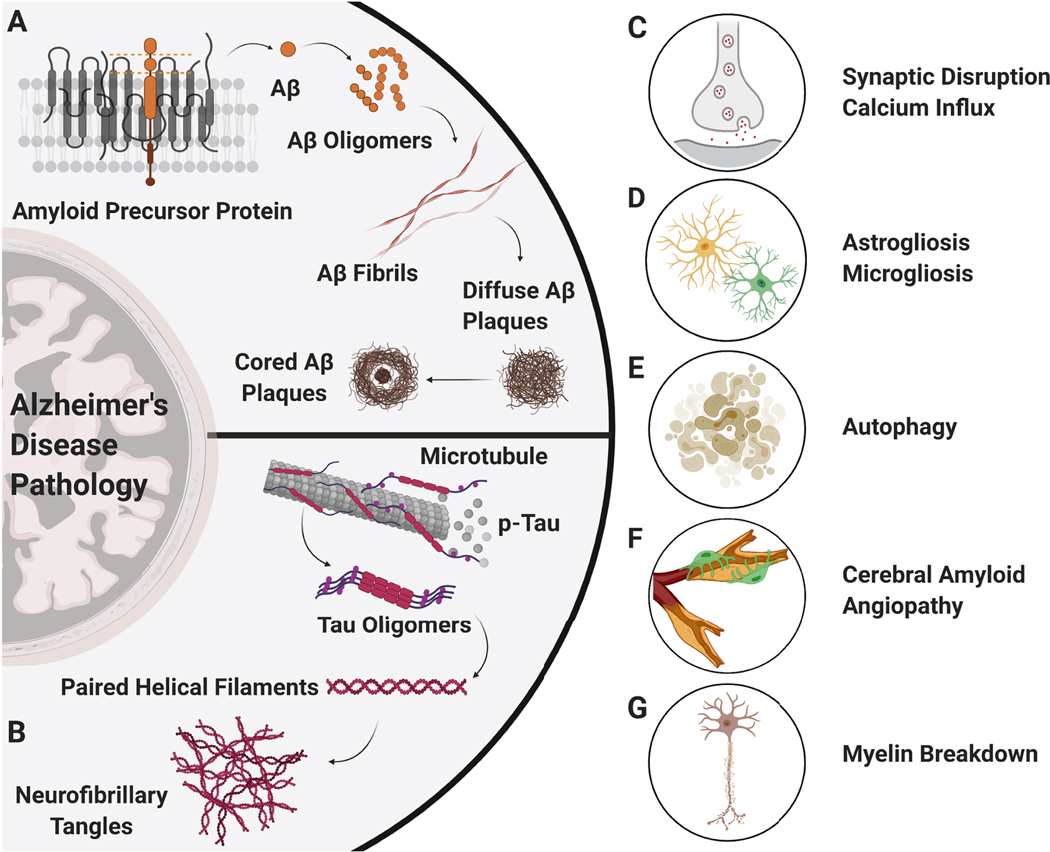

Historically, plaques and tangles have been observed in and around degenerating neurons and blood vessels in brain autopsy samples from AD patients (Divry, 1927; Morel, 1954; Scholz, 1938). Electron microscopy and diffraction studies in the 1960s demonstrated that plaques and NFTs are large, organized structures of β-pleated and paired helical filaments (Eanes & Glenner, 1968; Terry, 1963; Terry, Gonatas, & Weiss, 1964). By the 1980s, multiple biochemical studies found that amyloid-beta (Aβ, 4 kDa) accumulates in these plaques as oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrillar sheets (Figure 1A) (Glenner & Wong, 1984; Masters, 1984; Masters, et al., 1985; Roher, et al., 1996). Aβ is a 36–43 amino acid peptide that forms when amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cleaved by alpha- and gamma-secretases within the transmembrane region (Esch, et al., 1990; Sisodia, Koo, Beyreuther, Unterbeck, & Price, 1990). In AD, altered APP processing and impaired Aβ clearance result in 4- to 6-fold higher Aβ brain levels compared to Aβ brain levels typically found in individuals that age (De Strooper, et al., 1998; Funato, et al., 1998; Paresce, Chung, & Maxfield, 1997; Roher, et al., 2009; Scheuner, et al., 1996). Data from several studies showed that NFTs contain the microtubule-associated protein tau (~50 kDa) that is abnormally hyperphosphorylated and forms tau oligomers, granular tau aggregates, and paired helical filaments that accumulate in the brain of AD patients (Figure 1B; Grundke-Iqbal et al. 1986a; Grundke-Iqbal et al. 1986b; Grundke-Iqbal et al. 1979; Köpke et al. 1993; Maeda et al. 2006; Maeda et al. 2007(Grundke-Iqbal, Iqbal, Quinlan, et al., 1986; Grundke-Iqbal, Iqbal, Tung, et al., 1986; Grundke-Iqbal, Johnson, Terry, Wisniewski, & Iqbal, 1979; Kopke, et al., 1993; Maeda, et al., 2007). Tau peptides are 31–32 amino acids long with 2–3 phosphate molecules per peptide that are maintained by tau-specific kinases and phosphatases in the brain (Goedert & Crowther, 1989; Kopke, et al., 1993). In AD, the levels of total tau protein and abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau proteins can be 4- to 8-fold higher than tau protein levels found in the brain of healthy control individuals (Iqbal, Liu, & Gong, 2016). Brain accumulation of both Aβ and tau causes several pathophysiological changes that affect cognitive function in AD patients (Figure 1C-G). One of these pathophysiological changes involves intracellular calcium dysregulation in neurons and astrocytes, leading to excitotoxicity and astrogliosis (Figure 1C) (Abdul, et al., 2009; Bales, et al., 1998; Mattson, et al., 1992). Another pathophysiological change involves astrogliosis and microgliosis, where reactive astrocytes and microglia affect synaptic transmission, which contributes to cognitive impairment (Figure 1D; (DeKosky & Scheff, 1990; Hong, et al., 2016; Itagaki, McGeer, Akiyama, Zhu, & Selkoe, 1989; Terry, et al., 1991; Vogels, Murgoci, & Hromadka, 2019). A third pathophysiological change is a reduced lysosomal degradation capacity of neurons that leads to autophagy and neuronal loss (Figure 1E) (Cataldo, Barnett, Mann, & Nixon, 1996; Nixon, et al., 2005)). The fourth change is development of cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), where Aβ builds up in cerebral blood vessels resulting in ruptured vessel walls over time (Figure 1F) (E. E. Smith & Greenberg, 2009; Vinters, 1987). While plaques and tangles directly affect neurons in the brain, CAA disrupts synaptic and neurovascular networks by causing microhemorrhages, infarcts, and white matter lesions in the brain (E. E. Smith & Greenberg, 2009; Vinters, 1987). Fifth, CAA causes neurovascular dysfunction, which worsens cognitive function in AD patients (Brenowitz, Nelson, Besser, Heller, & Kukull, 2015; K. Jellinger, 2002). Besides these changes, myelin breakdown also affects synaptic connectivity in AD (Figure 1G) (Bartzokis, et al., 2003). Collectively, these pathophysiological changes make AD a multifactorial disease and add to the challenges in finding an effective treatment for patients.

Figure 1. Pathological Changes in the Central Nervous System in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

Amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau have been proposed to be the two key players that drive pathological progression in AD. A) Aβ, formed by the abnormal and sequential cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP), binds to other Aβ subunits to form oligomers, protofibrils, fibrils, diffused Aβ plaques (surrounded by glial inflammation), and Aβ plaques with a neuritic core causing neurodegeneration. B) In contrast, microtubule-associated tau proteins get abnormally hyperphosphorylated to form tau oligomers, paired helical filaments (PHF), and neurofibrillary tangles that drive AD pathology. Together, Aβ, tau, and their protein aggregates affect both neuronal and glial cells in the brain leading to C) elevated calcium influx and disruption in synaptic transmission, D) astrocytic and microglial inflammation, E) autophagy, F) cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and G) breakdown of the myelin sheath around neurons.

Current Challenges.

AD drug development is focused on 5 areas: 1) neurotransmitter systems (38%), 2) Aβ pathology (33%), 3) neuroinflammation (17%), 4) tau pathology (10%), and 5) cholesterol metabolism (2%; (“Therapeutics”)). Despite all efforts, only 5 FDA-approved drugs are currently available, and they all target the neurotransmitter system (Di Santo, Prinelli, Adorni, Caltagirone, & Musicco, 2013; Molino, Colucci, Fasanaro, Traini, & Amenta, 2013). Three of these drugs, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, are cholinesterase inhibitors that increase acetylcholine levels in the synaptic cleft, thereby improving cholinergic neurotransmission and counteracting cognitive decline in AD. The fourth drug, memantine, is an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist that blocks the effect of excess glutamate, thereby preventing glutamate-mediated calcium excitotoxicity in the brain. The fifth drug, aducanumab, targets parenchymal Aβ aggregates in the brain (Salloway, et al., 2009). All these drugs have a modest effect on cognition at best and lower dementia-related symptoms in only 40–70% of AD patients (Di Santo, et al., 2013; “Effects of Alzheimer’s disease drugs,”). Moreover, these improvements tend to subside after 6–12 months of pharmacotherapy as symptoms worsen, and none of these drugs influence the underlying pathophysiological processes (“Effects of Alzheimer’s disease drugs,”). To date, experimental drugs developed to have a disease-modifying effect show no significant improvement in cognitive performance in clinical studies (Cummings, Lee, Ritter, Sabbagh, & Zhong, 2019). Despite tremendous research efforts, none of these experimental drugs has made it to the market. Thus, there is a critical need for effective disease-modifying strategies that slow the progression of AD pathology and cognitive decline in AD patients.

1.2. Anatomy and Physiology of the Blood-Brain Barrier

Anatomy.

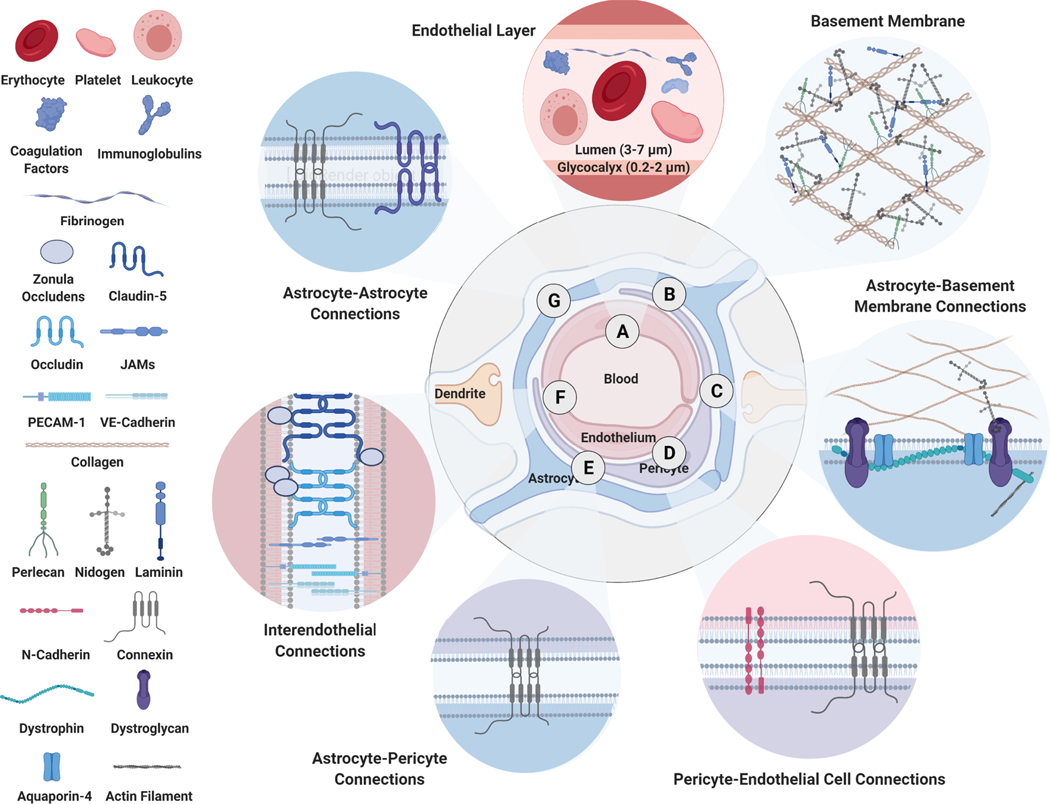

The cerebrovascular network originates from large pial arteries (diameter: 200–1,000 μm) that are surrounded by the CSF and the three meningeal layers at the brain surface (Bevan, Dodge, Walters, Wellman, & Bevan, 1999). Branches from the large pial arteries form penetrating arteries (70–200 μm) that dive deep into the brain parenchyma. These descending arteries feed parenchymal arterioles (20–70 μm) that subdivide into smaller precapillary arterioles (< 35 μm) and eventually form capillaries (3–7 μm). These capillaries are a unique part of the cerebrovascular network. With a diameter of 3–7 μm and a thickness of 0.1 μm, brain capillaries are the smallest vessels of the cerebrovascular system and form the structural basis of the blood-brain barrier (Figure 2) (Rodriguez-Baeza, Reina-de la Torre, Poca, Marti, & Garnacho, 2003). Structurally, brain capillary endothelial cells are covered by a 0.2–2 μm thick glycocalyx layer on the inner luminal side and a 50–100 nm vascular basement membrane on the outer abluminal side (Figure 2A, 2B) (Chappell, Westphal, & Jacob, 2009; L. Xu, Nirwane, & Yao, 2019). The glycocalyx layer on the luminal side is a scaffold of short membrane-bound glycoproteins as well as long, sulfated, and non-sulfated glycosaminoglycan chains that adsorb other proteins, water molecules, enzymes, and cells to nourish and protect the endothelial cell from injury, blood flow changes, and toxic substances (Chappell, et al., 2009; Schaefer & Schaefer, 2010). On the abluminal side, the basement membrane is composed of fibrous proteoglycans like collagen, laminin, nidogen, and fibronectin. Here, collagen and laminin isoforms self-assemble to create primary scaffolds held together by nidogen, fibronectin, thrombospondin, and other proteins and enzymes (Figure 2B) (Thomsen, Routhe, & Moos, 2017; L. Xu, et al., 2019)). Proteoglycans such as perlecan and agrin further stabilize this network, modulate signaling mechanisms, and regulate cell-matrix interactions (Barber & Lieth, 1997; Liebner, Czupalla, & Wolburg, 2011; Martin & Sanes, 1997; Osada, et al., 2011; Thomsen, et al., 2017). Proteoglycans in the basement membrane also recruit, anchor, and embed pericytes for each capillary to regulate capillary blood flow and neurovascular responses. They also adhere to and anchor astrocytes to coordinate oxygen and glucose delivery (Attwell, et al., 2010; Hirschi & D’Amore, 1996). Adhesion molecules that help proteoglycans mediate these interactions include immunoglobulin-cell adhesion molecules (IgCAMs), junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), integrins, as well as cadherins and selectins (Hynes, 1986; Kramer & Marks, 1989; Pytela, Pierschbacher, Ginsberg, Plow, & Ruoslahti, 1986; Sarelius & Glading, 2015). Connexins and other junctional proteins further seal the junctions between astrocytes and pericytes (Figure 2C-G) (Zhao & Gong, 2015). Together, endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons form the “Neurovascular Unit” (NVU) that regulates barrier function and controls what goes in and out of the brain (Figure 2C-G) (Iadecola, 2004; McConnell, Kersch, Woltjer, & Neuwelt, 2017).

Figure 2. Blood-Brain Barrier in Health.

A healthy neurovascular unit at the capillary endothelium forms the structural basis of the blood-brain barrier. A) Brain capillary endothelial cells are covered with a 200–2,000 nm thick glycoprotein-rich glycocalyx layer on the luminal side and B) a 50–100 nm thick proteoglycan-rich vascular basement membrane on the abluminal side. Proteoglycans in the vascular basement membrane anchor C) astrocytes and D) pericytes around capillary endothelial cells. E) Adhesion molecules further seal the connections among and between astrocytes and pericytes. F-G) At the endothelial interface, interendothelial junctions are further sealed by proteins such as claudin-5, occludin, zonula occludens-1, 2, 3, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), vascular endothelial (VE) – cadherins and form an intact blood-brain barrier.

Physiology.

The blood-brain barrier represents 1) a physical barrier that prevents passive brain uptake of endogenous and exogenous compounds, 2) a biochemical barrier that actively restricts brain uptake of xenobiotics and regulates nutrient supply, 3) a metabolic barrier that degrades neurotoxins, drugs, and other compounds at the blood-brain interface, and 4) an immunological barrier that limits immune cell entry into the brain. By forming a tight seal, tight junctions create a physical barrier between adjacent endothelial cells. This physical barrier lacks intercellular clefts and has low pinocytotic activity making it extremely difficult for compounds to cross it (Figure 2F). A myriad of influx and efflux transporters at the luminal and abluminal membrane of the endothelial cells constitute a biochemical barrier (Abbott, 2013; Daneman & Prat, 2015; Hartz & Bauer, 2011). The transporters at the barrier rigorously regulate what goes in and out of the brain. Phase I and phase II metabolic enzymes in endothelial cells comprise the metabolic barrier (Agundez, Jimenez-Jimenez, Alonso-Navarro, & Garcia-Martin, 2014). Initially, it was thought that there was an immunological barrier that prevents immune cells from entering the brain, and thus, the brain is an “immune-privileged organ”. This concept was proven incorrect; instead, the immunological barrier tightly regulates the migration of immune cells into and out of the brain (Greenwood, et al., 2011).

In a healthy brain, the blood-brain barrier is an active and dynamic barrier that separates the periphery from the CNS, prevents entry of a broad spectrum of compounds into the brain, maintains brain homeostasis, supplies the brain with oxygen and nutrients, and takes care of waste removal. In disease, however, this barrier is often damaged and can no longer maintain the functions required to maintain brain homeostasis and proper brain function.

1.3. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage in Alzheimer’s Disease

In this review, we define barrier dysfunction as an umbrella term for pathophysiological changes that occur at the blood-brain barrier in AD. These changes include structural alterations at the NVU, changes in Aβ and glucose influx/efflux transport mechanisms and leakage of bloodborne proteins for more detail we refer the reader to existing reviews (Kyrtata, Emslet, Sparasci, Parkes, & Dickie, 2021; Kirabali, et al., 2020; Kadry, Noorani, & Cucullo, 2020; Jia, et al., 2020; Chagnot, Barnes, & Montagne, 2021; Wang, et al., 2021). In the remainder of this article, we specifically focus on barrier leakage.

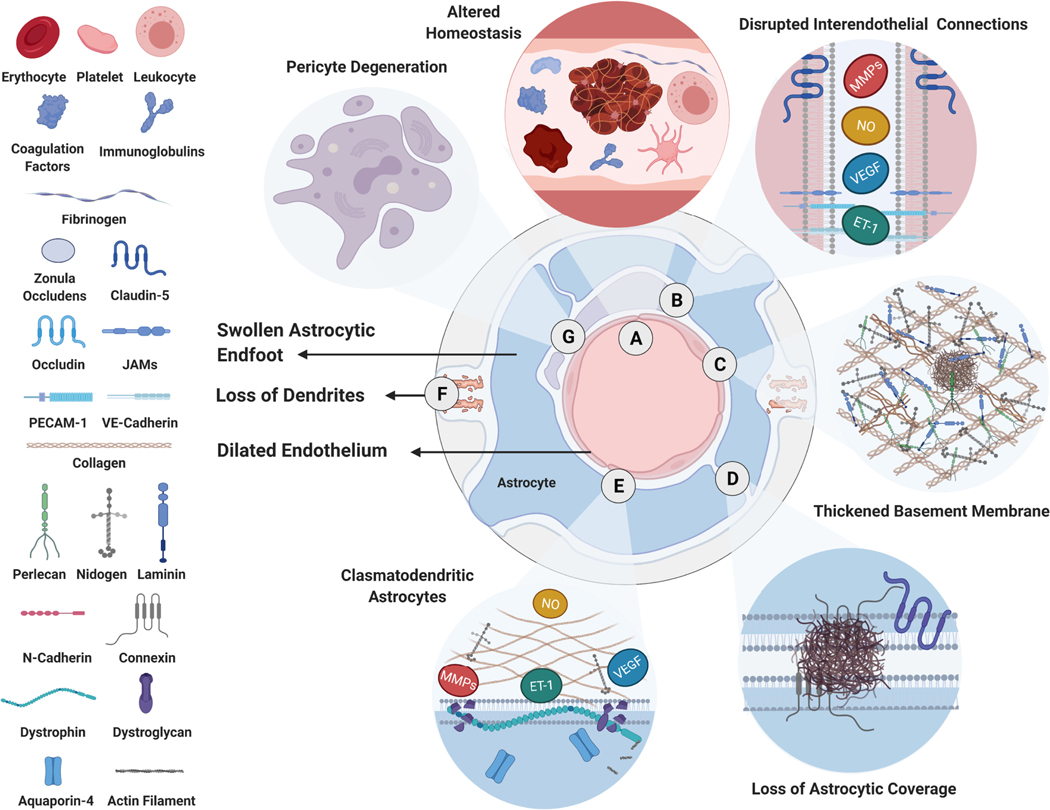

Blood-brain barrier leakage in AD was first observed more than 40 years ago, but it was not established until recently that a leaky barrier contributes to AD pathology (Glenner, 1979; Iadecola, 2013). A series of pathophysiological changes in AD affect the NVU and alter blood-brain barrier properties, thus leading to barrier dysfunction and ultimately leakage (Figure 3) (Kalaria & Harik, 1992; Montagne, et al., 2020; Richard, et al., 2010). Over the past decade, numerous studies have indicated a link between barrier leakage and cognitive decline in AD (de la Torre, 2017; Di Marco, Farkas, Martin, Venneri, & Frangi, 2015; Love & Miners, 2016; Montagne, et al., 2020; Nation, et al., 2019; Zhao & Gong, 2015). In this section, we will outline the most prominent changes that occur in each of these NVU components during AD.

Figure 3. Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease.

Pathological changes at the neurovascular unit in AD include A) increased coagulation and thrombosis, B) structural changes in endothelial cells and disruption of interendothelial junctions, C) altered proteoglycan and glycoprotein levels in the basement membrane, D) structural changes in astrocytes such as swollen astrocytic end-feet, loss of astrocytic coverage around endothelial cells, E) clasmatodendrosis, F) in addition to a loss of dendritic connections and G) pericytes around endothelial cells.

Endothelial Cells.

In AD, endothelial cells undergo structural changes that disrupt interendothelial junctions and thus limit their connections and interactions with other NVU components (Figure 3A, 3B) (Oikari, et al., 2020). For example, data from several studies show that in conditions like CAA, shedding of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1/CD31) and apoptosis occur in endothelial cells (Magaki, et al., 2018; Nielsen, Londos, Minthon, & Janciauskiene, 2007; Xue, et al., 2012). In addition, other adhesion molecules such as the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and the vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) contribute to the disruption of tight-junction proteins, increased actin stress fiber formation, and altered endothelial cell (Clark, Manes, Pober, & Kluger, 2007; Haarmann, et al., 2015). These changes disrupt paracellular transport at the blood brain barrier. In addition, endothelial cells also show increased transcellular movement of bloodborne substances via macropinocytosis, clathrin-dependent endocytosis, caveolae-mediated transcytosis, or vesicular trafficking (Zhou et al., 2021; Pandit et al., 2020; De Bock et al., 2016; Gurnik et al., 2016). Increased paracellular and transcellular pathways contribute to a leaky NVU in AD. Altered Glycocalyx and Basement Membrane. Structural and biochemical alterations in the glycocalyx and basement membrane change cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion at the entire NVU in AD (Figure 3B, C). Data from multiple studies indicate that these alterations are due to elevated proteoglycan levels in the brain. Fillit et al. (Fillit, Kemeny, Luine, Weksler, & Zabriskie, 1987) and Jenkins and Bachelard (Jenkins & Bachelard, 1988) showed that total proteoglycan levels are elevated in brain samples of AD patients compared to levels in samples of non-demented subjects. For instance, small cell-surface proteoglycans such as glypican (60–70 kDa) and syndecan (20–30 kDa) are located more frequently around capillaries that display CAA pathology (Lashley, et al., 2006; Lorente-Gea, et al., 2020; van Horssen, et al., 2001; Watanabe, et al., 2004). Hyaluronic acid (HA) is another glycocalyx and capillary basement membrane proteoglycan that is elevated in CSF samples from AD patients (Nagga, Hansson, van Westen, Minthon, & Wennstrom, 2014; Nielsen, Palmqvist, Minthon, Londos, & Wennstrom, 2012). In this regard, it is noteworthy that elevated HA protein levels are associated with increased Braak staging and a greater extent of cognitive decline in AD patients (Reed, et al., 2019). Collagen and agrin are two other proteoglycans that contribute to basement membrane thickening and fragmentation in AD (Christov, Ottman, Hamdheydari, & Grammas, 2008; Keable, et al., 2016; Magaki, et al., 2018; Merlini, Wanner, & Nitsch, 2016; Szpak, et al., 2007). Agrin shows “ragged and irregular” immunoreactivity within the cerebral microvasculature of AD patients compared to a uniform immunoreactivity along the cerebral microvasculature of cognitively normal subjects (Donahue, et al., 1999; van Horssen, et al., 2001). Agrin fragmentation also increases with AD progression, leading to higher soluble/fragmented agrin levels and reduced concentrations of insoluble/full-length agrin in brain samples (Berzin, et al., 2000; Salloway, et al., 2002). Collectively, altered proteoglycan composition in the capillary basement membrane affects barrier integrity in AD.

Astrocytes.

In AD, astrocytes undergo structural changes that lead to “clasmatodendrosis”, i.e., beading and disintegration of astrocyte projections along with cytoplasmic vacuolization, atrophy, and swelling of astrocytic end-feet (Figure 3D, 3E) (Boespflug, et al., 2018; Cullen, 1997; Higuchi, Miyakawa, Shimoji, & Katsuragi, 1987; Mancardi, Perdelli, Rivano, Leonardi, & Bugiani, 1980; Montagne, Zhao, & Zlokovic, 2017; Sweeney, Sagare, & Zlokovic, 2018; Yamashita, Miyakawa, & Katsuragi, 1991). At the end feet, reduced levels of anchoring proteins such as aquaporin-4 (AQP4), inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir4.1), and dystrophin 1 further limit astrocyte-endothelial connections (Boespflug, et al., 2018; Wilcock, Vitek, & Colton, 2009; Zeppenfeld, et al., 2017). These structural changes reduce astrocyte anchoring at the NVU, decreasing cerebral blood flow and neurovascular interactions (Iadecola, 2013).

Neurons.

Neurons regulate cerebrovascular organization and cerebral blood flow by secreting neurotransmitters such as glutamate, acetylcholine, or γ-aminobutyric acid at the neuronal-glial interfaces near synapses (Girouard & Iadecola, 2006; Hendrikx, et al., 2019; Lacoste, et al., 2014; Muoio, Persson, & Sendeski, 2014; Petzold & Murthy, 2011). Extensive synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss in AD can thus affect cerebrovascular tone and cerebral blood flow (Figure 3F) (Babic, 1999; Hamel, 2004; Kirkwood, et al., 2016; Mesulam, et al., 2019; Oh, et al., 2019; Van Beek & Claassen, 2011). Initial postmortem studies also showed that cortical neurons in brain tissue slices from AD patients are immunoreactive for proteins like agrin and occludin at the NVU (Berzin, et al., 2000; Romanitan, Popescu, Winblad, Bajenaru, & Bogdanovic, 2007). In contrast, CSF analysis does not indicate a strong association between markers of neuronal injury and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in AD (Muszynski, et al., 2017). Thus, the relationship between neurodegeneration and barrier dysfunction requires more research.

Pericytes.

In AD, pericytes undergo aggressive degradation (Halliday, et al., 2016; Wilhelmus, et al., 2007). In addition, cell surface receptors such as neural/glial antigen-2 (NG2) expressed along pericytes undergo extensive shedding, rendering these receptors unfunctional (Figure 3G) (Halliday, et al., 2016; Wilhelmus, et al., 2007). Data from postmortem studies using human tissue samples indicate that pericytes along degenerated vessels accumulate lipofuscin-like material and Aβ fibrils in AD (Baloyannis & Baloyannis, 2012; Raha, et al., 2017; Szpak, et al., 2007). As Aβ pathology progresses, these pericytes do not fully adhere to the vascular basement membrane loaded with Aβ clusters and collagen fibrils (Szpak, et al., 2007). In vitro, Aβ fibrils reduce soluble NG2 levels, a proteoglycan that supports pericyte-basement membrane interactions (Schultz, Nielsen, Minthon, & Wennstrom, 2014). Hippocampal slices from AD patients (n=13) have 1.5-fold lower (p < 0.05) NG2-positive pericytes per capillary compared to hippocampal slices from non-demented subjects (n=9) (Schultz, et al., 2018). Moreover, low levels of pericyte-specific soluble proteins are directly associated with lower cognitive scores for episodic memory, semantic memory, perceptual speed, visuospatial ability, and global cognition in AD patients (Bourassa, Tremblay, Schneider, Bennett, & Calon, 2020).

Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Leads to Barrier Leakage.

While we defined barrier dysfunction as an umbrella term for all pathophysiological changes at the NVU, barrier leakage specifically refers to increased transcellular and paracellular movement of bloodborne substances into the brain. Persistent stressors such as impaired perivascular Aβ clearance, oxidative stress, and reduced proteasomal degradation can cause sustained injuries and degeneration at the NVU, causing blood-brain barrier leakage. Meta-analyses indicate that barrier leakage is a common clinical and postmortem observation in AD that worsens cognitive decline and affects outcomes of experimental therapeutic strategies in enrolled AD patients (Farrall & Wardlaw, 2009; Janelidze, et al., 2017).

2. Preclinical Evidence of Barrier Leakage in Animal Models of Alzheimer’s Disease

Animal models are essential in preclinical AD research to study mechanisms underlying pathological processes and test novel therapeutic strategies to facilitate their translation into the clinic. In this section, we first introduce transgenic mouse AD models and describe their usefulness to study blood-brain barrier leakage. We then shift the focus to other animal models, including transgenic rats, dogs, and macaques that develop Aβ pathology and describe how these models could be used to investigate barrier leakage in AD.

2.1. Barrier Leakage in Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease

Transgenic mouse models are specifically designed for AD research to mimic certain aspects of disease pathology. Transgenic AD mice aggressively accrue neuropathological changes and cognitive decline over their lifetime. Recent studies found that transgenic AD mice also develop blood-brain barrier dysfunction that causes varying degrees of barrier leakage at different ages depending on the genetic make-up of the respective model (Figure 4). These pathological changes make transgenic mouse models suitable for 1) studying underlying mechanism(s) that link barrier leakage to cognition and 2) testing mechanism-based therapeutic strategies to repair barrier leakage and slow cognitive decline in AD. In the following paragraphs, we summarize characteristic features of commonly used mouse AD models, outline the extent and timeline of barrier leakage, and highlight potential mechanisms that lead to barrier leakage in these mice.

Figure 4. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage & Pathological Changes in Transgenic Mouse Models of AD.

Overview of eleven of the most frequently used transgenic mouse models of AD and the onset (in months) of different pathological changes in each model. Pathological changes include cognitive dysfunction (beige), Aβ pathology (grey), cerebral amyloid angiopathy (tan), cerebral blood flow reduction (light red), and microhemorrhages (light blue). An exhaustive literature search (1970 – 2020) revealed that barrier leakage has been previously characterized in these mice using tracers like albumin (dark red, 70 kDa), dextrans (4–150 kDa), IgG (150 kDa), Evans Blue dye (0.96 kDa) and Gadolinium (0.33 kDa). The extent of leakage for these tracers is depicted as log (fold-change) of the leakage value for transgenic mice compared to that of age-matched non-transgenic mice.

2.1.1. PDAPP Model.

In 1995, Games et al. (Games, et al., 1995) generated PDAPP mice, the first transgenic mouse AD model (background strain: C57B6 x DBA2). The model is called PDAPP (short for “PDGF promoter plus APP”) because PDAPP mice harbor a human amyloid precursor protein (hAPP) gene segment containing the Indiana mutation V717F and the neuronal platelet-derived growth factor β (PDGF-β) promoter that drives hAPP overexpression in the brain, heart, and lungs (Caroni, 1997; Games, et al., 1995). With increasing age, PDAPP mice develop spatial working memory deficits (4 months) followed by recognition memory deficits (6 months), Aβ deposits (6–9 months), and neuronal dystrophy (14 months) (Dodart, Mathis, Bales, Paul, & Ungerer, 1999; Hartman, et al., 2005; Masliah, Sisk, Mallory, & Games, 2001). Seubert et al. (Seubert, et al., 2008) showed that insoluble Aβ plaques drive cerebral Aβ deposition in PDAPP mice, and Kim et al. (Kim, Basak, & Holtzman, 2009) showed that PDAPP mice do not develop tauopathies or have neuronal loss and cognitive changes in young (< 6-months) PDAPP mice precede Aβ deposition. Thus, interpretation of the nature of the cognitive impairment in this model requires careful consideration. Neurovascular pathology in PDAPP mice, specifically CAA and microhemorrhages, occurs at 15 months but is not as widespread as in other mouse AD models such as the Tg2576 or APP23 models described below (Racke, et al., 2005; Schroeter, et al., 2008). Fryer and co-workers showed that knocking out apolipoprotein-E (APOE) prevents development of CAA and microhemorrhages in 15- and 24-month-old PDAPP mice (Fryer, et al., 2005). Paul et al. (J. Paul, Strickland, & Melchor, 2007) showed that Evans blue (0.96 kDa) extravasation in 6-month-old PDAPP mice is 10-fold higher than in age-matched wild type mice. Since Evans blue binds to large endogenous molecules like IgG and albumin among other proteins, it is unclear if these changes reflect extravasation of free dye or protein-bound dye (Saunders, Dziegielewska, Mollgard, & Habgood, 2015). In contrast, Blockx et al. (Blockx, et al., 2016) used dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) and detected trace amounts of gadolinium leakage in the brain parenchyma of 12-to-16-month-old PDAPP and wild type mice that received the contrast agent gadolinium by intravenous bolus injection. In summary, the mouse PDAPP model is suitable for studying the link between neurovascular Aβ pathology, CAA, and blood-brain barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.2. Tg2576 Model.

In 1996, Hsiao et al. (Hsiao, et al., 1996) described the Tg2576 mouse AD model (background strain: Swiss-Webster x C57B6/DBA2). To date, this model is one of the most commonly used and best-characterized mouse models in preclinical AD research. Tg2576 mice harbor the Swedish double-mutation KM670/671NL on the hAPP gene. In patients, this double-mutation causes early-onset familial AD. The mouse-hamster prion protein promoter non-specifically drives hAPP overexpression in Tg2576 mice in the brain and several peripheral tissues such as the heart, kidney, and lungs (Boy, et al., 2006). Unlike PDAPP mice that overexpress neuronal hAPP, non-specific hAPP overexpression in Tg2576 mice causes brain-wide and early Aβ pathology. Specifically, Tg2576 mice develop soluble Aβ pools (< 3 months) followed by spatial working memory deficits (5 months), reduced cerebral blood flow (8 months), Aβ plaques (11–13 months), and tau oligomers associated with cerebrovascular Aβ deposits (22 months) (Castillo-Carranza, et al., 2017; Irizarry, McNamara, Fedorchak, Hsiao, & Hyman, 1997; Kawarabayashi, et al., 2001). Eventually, these soluble Aβ pools drive cognitive decline and CAA in Tg2576 mice by 9–10 months (S. W. Park, et al., 2014; Robbins, et al., 2006; Shin, et al., 2007; Westerman, et al., 2002). Using Tg2576 mice, Gregory et al. (Gregory, et al., 2012) showed intravenous administration of the γ-secretase inhibitor LY411575 and the high-affinity Aβ-binding protein gelsolin prevented CAA formation but did not clear pre-existing CAA deposits. This finding suggests that CAA spreads in the anterior brain regions of these mice and propagates laterally between 10–16 months of age along leptomeningeal vessels and develops globally by 23 months of age (Domnitz, et al., 2005). Further, CAA develops along existing networks of affected vessels instead of forming new foci in unaffected vessels (Robbins, et al., 2006). Microhemorrhages start to appear in Tg2576 mice at about 15 months of age, and the number of microhemorrhages increases with age (Fisher, et al., 2011). Fryer et al. (Fryer, et al., 2005) showed that knocking in the APOE4 allele in Tg2576 mice exacerbates CAA pathology but not parenchymal Aβ plaque deposition, which indicates that APOE4 expression triggers CAA and microhemorrhages in this mouse model.

Paul et al. (J. Paul, et al., 2007) showed that in 6-month-old Tg2576 mice, Evans blue leakage is 10-fold higher compared to that in age-matched wild type mice. Likewise, Goldman et al. (Elhaik Goldman, et al., 2018) reported a 2-fold higher leakage for gadolinium-based tracers in 8-month-old Tg2576 mice compared to age-matched wild type mice. Data from both studies also show that leakage of the respective vascular marker is 2-fold higher in 12-month-old Tg2576 mice than in wild type mice (Elhaik Goldman, et al., 2018; J. Paul, et al., 2007). Over time, older (10–25 months) Tg2576 mice show dense vascular Aβ deposits that are immunoreactive for IgG, plasminogen (84–90 kDa), tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; 70 kDa), and albumin (70 kDa), indicating that barrier leakage contributes to extravasation of blood-borne substances in the brain (Kumar-Singh, et al., 2005; J. W. Lee, et al., 2007). Together, these studies show that in the microvasculature of Tg2576 mice, barrier leakage follows CAA.

Despite ample evidence showing barrier leakage in Tg2576 mice, a leaky barrier does not necessarily imply easier brain access for intravenously injected tracers or therapeutic drugs. Thakker et al. (Thakker, et al., 2009) first observed this phenomenon for the anti-Aβ antibody 6E10, which was more effective in resolving CAA after intracerebroventricular infusion using osmotic minipumps compared to intravenous injection. Data from a study by Hawkes et al. (Hawkes, et al., 2011) support this finding: fluorescent-labeled dextran (10 kDa) was intravenously injected into 22-month-old Tg2576 and wild type mice, but the marker reached fewer capillaries in Tg2576 mice than in wild type mice (~1 vs. 12%). The biochemical changes underlying barrier leakage in capillaries of Tg2576 mice include reduced protein expression levels and disrupted expression patterns of tight junctions, including zonula occludens (ZO-1) and occludin (Biron, Dickstein, Gopaul, & Jefferies, 2011; Hartz & Bauer, 2011). Consistent with this, Keaney et al. (Keaney, et al., 2015) found that treating Tg2576 mice with claudin-5 and occludin siRNAs increased paracellular barrier permeability for smaller (3 kDa) but not larger (10 kDa) dextrans.

In summary, soluble Aβ drives blood-brain barrier leakage and vascular injury in Tg2576 mice. Hence, the Tg2576 mouse model is useful for studying soluble Aβ changes across the blood-brain interfaces, the impact of CAA, barrier leakage, and cognitive impairment in AD.

2.1.3. APP23 Model.

In 1997, Sturchler-Pierrat et al. (Sturchler-Pierrat, et al., 1997) described the APP23 mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL/6). Like the Tg2576 mouse model, APP23 mice harbor the Swedish double-mutation on the hAPP gene, but the neuronal Thy1 promoter drives hAPP overexpression (Caroni, 1997; Sturchler-Pierrat, et al., 1997). Differences in the promoter between the APP23 (Thy1) and Tg2576 (PrP) models reflect several differences in the onset and severity of Aβ pathology in these mice. First, in contrast to Tg2576 mice, soluble Aβ blood levels do not increase in APP23 mice over time (Calhoun, et al., 1999; Kuo, et al., 2001; Thal, Griffin, & Braak, 2008). Second, APP23 mice develop spatial memory deficits 3 months earlier and Aβ plaques and tauopathy 6 months earlier than Tg2576 mice. Thus, the timeline and extent of Aβ pathology differ between these two models. (Calhoun, et al., 1999; Kelly, et al., 2003; Reuter, Venus, Heiler, et al., 2016; Sturchler-Pierrat, et al., 1997; Van Dam, et al., 2003). Third, knocking out the APOE allele leads to vascular damage and oxidative stress in APP23 mice (Tibolla, et al., 2010). In contrast, overexpressing APOE4 leads to vascular injury and oxidative stress in Tg2576 mice (Fryer, et al., 2005).

Vascular abnormalities are evident in APP23 mice at 6 months of age. One of these abnormalities is activated platelets that overexpress integrin on their surface, which facilitates the adhesion of activated platelets with fibrinogen and collagen, leading to vessel occlusion (Jarre, et al., 2014). In addition, IgG levels are elevated (1.2-fold) in neurons, glial cells, and blood vessels of 6-month-old APP23 mice compared to age-matched wild type mice, suggesting that IgG synthesis occurs in various brain cells in these mice (Beckmann, et al., 2003; J. Shang, et al., 2016). By 11 months of age, reduction in cerebral blood flow is evident, whereas CAA and microhemorrhages occur around 18 months (Beckmann, et al., 2003; Kuo, et al., 2001; Winkler, et al., 2001). Around the same time, APP23 mice also have other vascular irregularities such as kinked, twisted, and/or studded blood vessels with knobs and protrusions and missing vascular networks in the frontal and temporal cortices (Meyer, Ulmann-Schuler, Staufenbiel, & Krucker, 2008; Winkler, et al., 2001). Additionally, multiple studies indicate that in APP23 mice, cerebral blood flow changes and CAA precede vascular injury (Luth, Holzer, Gartner, Staufenbiel, & Arendt, 2001; Mueggler, Baumann, Rausch, Staufenbiel, & Rudin, 2003; Mueggler, et al., 2002; Thal, et al., 2008). Hence, APP23 mice are a suitable AD model to study cerebrovascular changes and the mechanism leading to barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.4. APP(V717I) Model.

In 1999, Moechars et al. (Moechars, et al., 1999) described the APP(V717I) mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL/6 x FVB/N). These mice harbor the hAPP gene with the APP London (V717I) mutation, one of the earliest known and most common familial AD mutations worldwide (Cruts, Theuns, & Van Broeckhoven, 2012; Goate, et al., 1991). The neuronal Thy1 promoter drives hAPP overexpression leading to spatial memory deficits (6 months), which is followed by the formation of Aβ plaques (10 months), CAA (15 months), and microhemorrhages (25–30 months) (Caroni, 1997; Van Dorpe, et al., 2000). However, the onset and extent of barrier leakage in APP(V717I) mice is not well-understood. A recent clinical report by Lloyd et al. (Lloyd, et al., 2020) highlighted the role of the hAPP (V7171) mutation in leptomeningeal CAA, which sparked interest in this mutation because this may affect leakage at the blood-CSF interface. Hence, APP(V717I) mice are suitable for exploring how the hAPP (V717I) mutation contributes to CAA at the blood-CSF barrier in AD.

2.1.5. J20 Model.

In 2000, Mucke et al. (Mucke, et al., 2000) described the J20 mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL6). This model harbors the Indiana (V717F) mutation and the Swedish double-mutation in the hAPP gene with the PDGF-β promoter driving neuronal hAPP overexpression (Mucke, et al., 2000; Sasahara, et al., 1991). J20 mice develop high soluble Aβ brain levels (1–2 months), neuronal loss (3 months), and spatial memory impairment (4 months) before Aβ plaques occur (5–7 months) (I. H. Cheng, et al., 2007; Hong, et al., 2016; Shabir, et al., 2020; Wright, et al., 2013). At about 11 months of age, J20 mice have reduced cerebral blood flow, CAA, and microhemorrhages (Lin, et al., 2013), which is followed by barrier leakage (12 months), as is evident from 2-fold higher extravasation of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled dextran (150 kDa) compared to age-matched wild type mice (Van Skike, et al., 2018). Van Skike et al. ((Van Skike, et al., 2018)) also observed that junctional adhesion molecule-A protein levels are reduced by 50% in brain capillaries of 10-month-old J20 mice compared to age-matched wild type mice. By 15–19 months of age, J20 mice display a 20% reduced pericyte function and 20% lower AQP-4 immunoreactivity compared to age-matched wild type mice (Kimbrough, Robel, Roberson, & Sontheimer, 2015). These studies indicate that Aβ pathology precedes barrier dysfunction and leakage. Thus, the J20 mouse model is ideal for evaluating how Aβ pathology causes barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.6. TgCRND8 Model.

In 2001, Chishti et al. (Chishti, et al., 2001) described the TgCRND8 mouse AD model (background strain: C3H/He-C57Bl/6). This model harbors the hAPP gene with the Swedish and Indiana mutations, and the hamster PrP promoter drives hAPP overexpression in neurons and non-neuronal tissue (Boy, et al., 2006). TgCRND8 mice develop spatial deficits (3 months) before the development of Aβ plaques (5 months), neuronal loss (6 months), and tauopathies (7–12 months) (Bellucci, et al., 2007; Brautigam, et al., 2012; Chishti, et al., 2001). CAA and reduced cerebral blood flow develop earlier in TgCRND8 mice than in J20 mice (6 months vs. 11 months) due to impaired perivascular Aβ clearance (Cortes-Canteli, et al., 2019; Lin, et al., 2013). By 12 months, TgCRND8 mice have developed capillary CAA, a 2-fold increase in hypertrophied pericytes, and a 20% reduction in perivascular AQP-4 immunoreactivity compared to age-matched wild type mice (Cortes-Canteli, Mattei, Richards, Norris, & Strickland, 2015). Permeability studies also indicate that Evans blue has 12-fold higher intensity levels in 6-month-old TgCRND8 mice than in age-matched wild type mice (J. Paul, et al., 2007). Evans blue permeability values were 7.5-fold higher in 12-month-old TgCRND8 mice than in age-matched wild type mice. At 12 months, brain capillaries from TgCRND8 mice also become tortuous and develop fragmented perivascular fibrin deposits (Durrant, Ruscher, Sheppard, Coleman, & Ozen, 2020; J. Paul, et al., 2007). More recently, Yuan et al. (Yuan, et al., 2020) have reported that intrathecally infused tracers colocalize with CAA sites in TgCRND8 mice. It remains to be seen if CAA contributes to barrier leakage in TgCRN8 mice. In summary, TgCRND8 mice are a suitable model to study the link between CAA and barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.7. 3xTg-AD Model.

In 2003, Oddo et al. (Oddo, et al., 2003) developed the triple transgenic mouse model 3xTg-AD (background strain: C57BL/6). This model harbors the human APP gene segment with the 1) Swedish mutation, 2) the human MAPT gene segment with the P301L mutation, and 3) the human presenilin-1 gene segment bearing the M146V mutation. All three genes are under the control of the neuronal Thy1.2 promoter, and 3xTg-AD mice develop long-term memory retention deficits (4 months) before Aβ deposition (6 months) and tauopathy (12 months) occur (Billings, Oddo, Green, McGaugh, & LaFerla, 2005; Oddo, et al., 2003). Zerano et al. (Zenaro, et al., 2015) further showed that neutrophils infiltrate the brain in 4–6-month-old 3xTg-AD mice, causing early cognitive decline. The age at CAA onset and the extent of microhemorrhages is not known for 3xTg-AD mice. However, multiple studies indicate that barrier leakage in 3xTg-AD mice is subtle. First, data from a study by Do et al. (Do, et al., 2014) show that the diffusion rate of the highly lipophilic drug diazepam (0.3 kDa) is unchanged in 3–18-month-old 3xTg-AD mice. Second, St-Amour et al. (St-Amour, et al., 2013) found that intravenously infused IgGs remain in the capillary lumen of 3xTg-AD mice at 10–11 months of age. Third, Bourassa et al. (Bourassa, Alata, Tremblay, Paris-Robidas, & Calon, 2019) observed that antibody internalization by transferrin receptors is not significantly different between 12, 18, and 22-month-old 3xTg-AD mice. In contrast, with DCE-MRI, Chiquita et al. (Chiquita, et al., 2019) found a 2-fold higher leakage value in 3xTg-AD mice compared to wild type mice. This study, however, had a small sample size, and mice were pooled across ages (4–12 months). One potential explanation for the minimal barrier leakage observed in 3xTg-AD could be the 20% increase in collagen protein levels and the 32% increase in basement membrane thickness (Bourasset, et al., 2009). Hence, 3xTg-AD mice are a suitable model for evaluating the effect of basement membrane changes on barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.8. TgSwDI Model.

In 2004, Davis et al. (Davis, et al., 2004) described the TgSwDI mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL/6). This model harbors an hAPP gene segment with three mutations (Swedish, Dutch (E693Q), and Iowa (D694N)), and hAPP overexpression is driven by the neuronal Thy1 promoter (Davis, et al., 2004). TgSwDI mice simultaneously develop Aβ pathology, memory deficits, and reduced cerebral blood flow as early as 3 months of age, but it is unknown if TgSwDI mice develop tauopathies or neuronal loss (Davis, et al., 2004; Searcy, Le Bihan, Salvadores, McCulloch, & Horsburgh, 2014; F. Xu, et al., 2007). Data from several studies show that the Dutch and Iowa mutations drive Aβ deposition in the cerebrovasculature, which leads to CAA and microhemorrhages in TgSwDI mice at age 6 months (Davis, et al., 2004; Davis, et al., 2006; Van Vickle, et al., 2008). Xu et al. (F. Xu, et al., 2007) demonstrated that knocking out the APOE allele causes a shift from microvascular to parenchymal Aβ deposits without changing the overall Aβ burden indicating that APOE is the driving force for CAA and microhemorrhages in this AD model. Searcy et al. (Searcy, et al., 2014) conducted a longitudinal study and showed that APOE protein levels increased 3-fold in 9-month-old TgSwDI mice compared to 3-month-old wild type mice, indicating that CAA may also increase with age in these mice. Choi et al. (S. Choi, Singh, Singh, Khan, & Won, 2020) recently found that inhibiting endothelial nitric oxide synthase with dimethylarginine (50 mg/kg/day, 56 days) in 8-month-old TgSwDI mice reduces cerebral blood flow, increases Evans blue brain levels, causes loss of tight junction proteins, leads to stress fiber formation, and reduces capillary density compared to age-matched wild type mice. Capillaries from 12-month-old TgSwDI mice display reduced pericyte coverage and decreased perivascular AQP-4 expression (Duncombe, et al., 2017). These changes occur before any changes in basement-membrane protein levels (e.g., nidogen-1, laminin, collagen) (Searcy, et al., 2014). Hence, TgSwDI mice are ideal to evaluate the mechanism underlying barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.9. Tau P301L Model.

In 2005, Terwel et al. (Terwel, et al., 2005) described the Tau P301L mouse AD model that harbors the human tau gene with the P301L mutation. In this model, tau overexpression is driven by the neuronal Thy1 promoter (background strain: FVB/N). As a result, Tau P301L mice develop sensorimotor and learning deficits (5 months) before displaying tangle-like pathology in the hindbrain and cortex (8 months). Further, Bennet et al. (Bennett, et al., 2017) demonstrated that Tau P301L mice have decreased cerebral blood flow by age 12 months, which is accompanied by obstructed capillaries, a reduced capillary diameter, and increased vascular density. The authors also showed in 2–18-month-old mice that angiogenic markers such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) are upregulated, suggesting that increased vascular density is linked to angiogenesis (Bennett, et al., 2017). In addition, MMPs degrade the basement membrane and tight junction proteins and contribute to barrier leakage in other mouse AD models (Hartz, et al., 2012). In summary, Tau P301L mice are suitable for evaluating tau-mediated changes of barrier dysfunction in AD.

2.1.10. APP/PS1 Model.

In 2004, Jankowsky et al. (Jankowsky, et al., 2004) described the APP/PS1 mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL/6). This model harbors the hAPP gene with the Swedish mutation and the human presenilin-1 (PSEN-1) gene segment without exon 9; the overexpression of both hAPP and PSEN-1 is driven by the mouse PrP promoter (Jankowsky, et al., 2004). APP/PS1 mice develop Aβ pathology and CAA (6 months) before neuronal loss (8–10 months) and spatial memory deficits and microhemorrhages (12 months) (Jackson, et al., 2016; Jankowsky, et al., 2004; Lefterov, et al., 2010; Liao, et al., 2014; Volianskis, Kostner, Molgaard, Hass, & Jensen, 2010). In addition, Garcia-Alloza et al. (Garcia-Alloza, et al., 2009) and other groups have shown that neuroinflammation plays a role in barrier dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice (Harcha, et al., 2015; Xie, et al., 2020). Specifically, these groups showed microglial activation, reduced microvascular blood flow, and decreased ZO-1 protein expression levels in 6 to 11-month-old APP/PS1 mice before parenchymal Aβ deposition and CAA occurred (Garcia-Alloza, et al., 2009; Harcha, et al., 2015; Xie, et al., 2020). Other researchers conducted gadolinium-based DCE-MRI studies in 14- and 24-month-old APP/PS1 mice and showed that interferon-gamma (IFNγ)-producing cells shift APP/PS1 microglia to an activated state that results in more cytokine production leading to barrier leakage with aging (Minogue, et al., 2014). In summary, APP/PS1 mice are appropriate for investigating the effect of neuroinflammatory changes on barrier leakage in AD.

2.1.11. 5xFAD Model.

In 2005, Oakley and colleagues (Oakley, et al., 2006) developed the 5xFAD mouse AD model (background strain: C57BL6). This model is named after the five familial AD mutations it harbors: 1) human APP gene with the Swedish mutation, 2) human APP gene with the Florida (I716V) mutation, 3) human APP gene with the London (V717I) mutation, 4) human PSEN1 gene with the M146L mutation, and 5) the human PSEN1 gene with the L286 mutation. The neuronal Thy1 promoter drives overexpression of hAPP and human PSEN1, and consequently, 5xFAD mice develop aggressive amyloid pathology (1.5–2 months) before spatial memory deficits (4–5 months) and neuronal loss (6–12 months) (Devi & Ohno, 2010; Jawhar, Trawicka, Jenneckens, Bayer, & Wirths, 2012; Oakley, et al., 2006; Xiao, et al., 2015). In addition, 5xFAD mice also develop meningeal CAA, and the deletion of endothelial nitric oxide synthase can further enhance this pathology (Hu, Kotarba, & Van Nostrand, 2013). Reduced cerebral blood flow occurs at 5–6 months of age and develops simultaneously with stalled brain capillaries, increased adhesion of neutrophils, and neuroinflammation (Cruz Hernandez, et al., 2019). Hence, data from barrier leakage studies in 5xFAD mice present a rather complex picture. For example, some studies report that tracers like thioflavin-S (318 Da) and sodium fluorescein (332 Da) were not detectable in the brain of 5xFAD mice (Barton, et al., 2019; Marottoli, et al., 2017). In contrast, other studies using FITC-labeled albumin (70 kDa) showed an age-dependent increase in microvascular leakage and reduced capillary length across multiple brain regions in 4 to 12-month-old 5xFAD mice (Giannoni, et al., 2016).

Microglia regulate many of the changes observed at the blood-brain barrier in 5xFAD mice. In a recent study, Spangenberg et al. (Spangenberg, et al., 2019) used clodronate to deplete microglia in 5xFAD mice. As a result, they found reduced claudin-5 protein levels in endothelial cells, increased number of microhemorrhages, and a shift from parenchymal to vascular Aβ deposition. Hence, 5xFAD mice are suitable for evaluating the effects of vascular Aβ depositions on barrier function.

2.1.12. SAMP8 Mice.

In 1988, Yagi and colleagues (1988) developed the Senescence-Accelerated Mouse (SAMP8) model (background strain: AKR/J). SAMP8 mice develop oxidative stress (2 months) before tau hyperphosphorylation (3 months), learning and memory deficits (4 months), inflammation (5 months), Aβ deposition (6 months), synaptic degeneration (8 months) and neuronal loss (10 months; Liu and Shi, 2020). Studies by Ueno et al. show a 1.6-fold increase in hippocampal permeability for 125I-human serum albumin and horseradish peroxidase in 13-month-old mice compared to 3-month-old mice (Ueno et al., 1993; Ueno et al., 1997). Ultrastructural studies by Ueno et al. (2001) also show extravasated horseradish peroxidase near endothelial cells with thickened cytoplasm, collagen depositions, and damaged pericytes. These findings were observed in 12-month-old SAMP8 mice but not in 3- or 6-month-old SAMP8 mice, indicating that barrier leakage in SAMP8 mice was associated with aging instead of learning and memory deficits (Ueno et al., 2001). Confocal imaging studies by Pelegri et al. also show significant IgG extravasation in the hippocampi in 6-to-15-month-old SAMP8 mice (Pelegri et al., 2007; del Valle et al., 2009). In contrast, Banks and colleagues did not find age-related differences in the brain uptake of various bloodborne molecules such as albumin, insulin, interleukin, tumor necrosis factor and IgM antibodies (Banks et al., 2000; Moinuddin et al., 2000; Banks et al., 2001, Banks et al. 2007). Nonaka et al. (2002) observed differences in brain uptake values of 131I-labeled pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide between 2-month-old and 12-month-old SAMP8 mice; these differences were attributed to differences in Aβ pathology between the two groups. Taken together, these studies indicate a lack of consensus on blood-brain barrier intactness and the role of Aβ pathology on barrier leakage in SAMP8 mice.

2.2. Barrier Leakage in Other Models of Alzheimer’s Disease

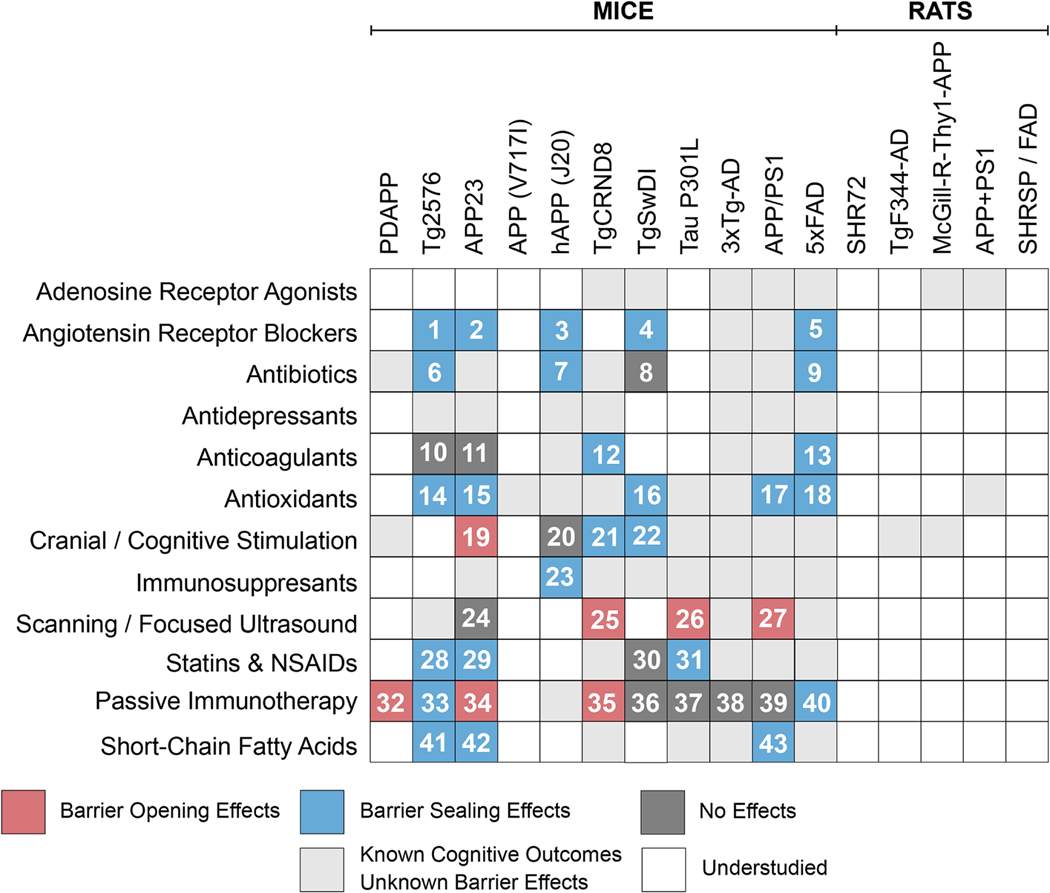

Barrier dysfunction and cerebrovascular abnormalities are also present in aged and cognitively impaired human APP-overexpressing transgenic rats, aged dogs, and aged non-human primates. In aged macaques, capillary CAA is more commonly observed near mature Aβ plaques and collapsing or degenerating capillaries (D’Angelo, Dooyema, Courtney, Walker, & Heuer, 2013; Latimer, et al., 2019; Nakamura, et al., 1998; Ndung’u, et al., 2012). Aged dogs with cognitive impairment develop CAA, and collagen fibrils build up between astrocyte endfeet and capillary basement membranes leading to cerebral hemorrhages (Kimotsuki, et al., 2005; Morita, Mizutani, Sawada, & Shimada, 2005; Rodrigues, et al., 2018). With age, transgenic AD rats develop a thickened capillary basement membrane, disrupted tight junction proteins, detached astrocytes, and capillary endothelial cell deformation, which is why transgenic AD rats represent a suitable model to investigate barrier leakage (Bors, et al., 2018; Mooradian, 1988). Data from several transgenic rat AD models that overexpress hAPP (TgF344, McGill-R-Thy1-APP, APP+PS1) and/or human tau (SHR72, SHRSP/FAD) indicate that microvascular abnormalities are directly associated with AD pathology. For example, SHR72 rats develop cerebral blood flow impairment before Aβ accumulation, vascular changes, or cognitive deficits (Koson, et al., 2008). In these rats, gene expression levels of MMP-9, coagulation factors, angiogenic, and adhesion molecules (selectins, ICAM-1, VCAM-1) increase in brainstem capillaries with aging (Grammas & Ovase, 2002; Majerova, et al., 2019). Another example is the APP+PS1 model, where rats develop abluminal Aβ and collagen deposits within enlarged perivascular spaces in the brain (Klakotskaia, et al., 2018). A third example is the SHRSP/FAD rat model where AQP-4 shifts from a perivascular to a neuronal expression pattern, PECAM-1 protein levels are elevated around tight junction proteins, and collagen thickness is increased compared to wild type rats (Denver, et al., 2019). A fourth example is the McGill-R-Thy1-APP rat that displays increased vessel branching, collagen thickness, and angiogenesis when the Notch signaling pathway is genetically activated (Galeano, et al., 2018). Another example is the TgF344-AD rat that has reduced mural cell repairing capacity in arterioles compared to wild type rats (Bazzigaluppi, et al., 2019). Due to the limited number of studies in non-murine AD models, it is unclear when and how blood-brain barrier leakage develops in these species. In summary, these studies show that blood-brain barrier dysfunction is associated with pathological changes in AD across multiple animal models.

Although transgenic models have been widely used to study pathological processes associated with barrier leakage in AD, certain challenges limit further investigation of the mechanisms underlying barrier leakage in AD. First, transgenic models are a tool for studying pathological changes that follow protein expression but not the events preceding protein expression. Second, transgenic models that overexpress human APP and/or PS proteins develop widespread Aβ pathology but may not develop aggressive tangle pathology, neuronal loss, and cognitive deficits (Sabbagh et al., 2013). In contrast, transgenic models that overexpress human tau proteins may not develop Aβ pathology and fail to capture the entire spectrum of pathological changes in AD. Transgenic models that overexpress human Aβ and tau pathology do not inform us about pathological changes linked to sporadic or late onset AD. These models provide very different mechanistic information about barrier dysfunction and leakage that can be relevant but difficult to compare across studies and provide translational value.

3. Clinical Evidence of Barrier Leakage in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients

Detection of blood-brain barrier leakage in AD patients goes back to the 1980s when researchers discovered serum-borne proteins such as IgG and albumin in the brain parenchyma, indicating a compromised blood-brain barrier in AD patients (Alafuzoff, Adolfsson, Bucht, & Winblad, 1983; Alafuzoff, Adolfsson, Grundke-Iqbal, & Winblad, 1987). Although the idea that barrier leakage could play a role in AD pathology was controversial for decades, recent clinical data emphasizes a link between barrier leakage and cognitive decline in AD patients. In the following section, we will summarize the studies that identified barrier leakage in AD.

3.1. Cerebrospinal Fluid-to-Plasma Ratio

The CSF-serum ratio, also referred to as Q value, is one of the first and most commonly used clinical parameters to characterize barrier leakage. In a healthy individual, protein levels of blood-borne proteins such as IgG (150 kDa) and albumin (70 kDa) are 100- to 200-fold higher in the blood (IgG: 7–16 g/L; Albumin: 35–50 g/L) compared to that in the CSF (IgG: 0–0.08 g/L; Albumin: 0–0.03 g/L) (Mayo Clinic Family Health Book 5th Edition). Thus, an elevated Q value for albumin (Qalb) reflects extravasated albumin in the CSF (Rothschild, Oratz, & Schreiber, 1980). The QIgG reflects both extravasated and intrathecally synthesized IgG in the central nervous system (CNS). Except for one study by Elovaara et al. (Elovaara, Seppala, Palo, Sulkava, & Erkinjuntti, 1988), QIgG values are not significantly different between AD patients and age-matched non-demented individuals (Table 1). A 100- to 200-fold difference in these concentrations (QIgG value < 0.007) is likely due to intact CNS barriers that restrict blood-borne proteins from entering the CSF (Garton, Keir, Lakshmi, & Thompson, 1991). Depending on the severity of the pathology, QIgG values indicate slight to moderate barrier leakage (0.01–0.03), severe barrier leakage (0.03–0.10), or even complete barrier breakdown (QIgG > 0.1) (Schliep & Felgenhauer, 1978). Over the past 50 years, multiple research groups have estimated that Qalb and QIgG are slightly elevated (> 0.007) in AD patients compared to non-demented individuals (Tables 1 and 2). More systematic meta-analyses have identified that increased Qalb and QIgG values are 0.65 to 1.3-fold-higher (p < 0.05) in AD patients compared to non-demented individuals (Farrall & Wardlaw, 2009; Jankowsky, et al., 2004; Musaeus, et al., 2020; Muszynski, et al., 2017; Olsson, et al., 2016; Skillback, et al., 2017). Collectively, these studies indicate that CSF-to-serum ratios are a surrogate marker for barrier leakage in AD. Careful interpretation is required when using CSF-to-serum ratio since the rate of CSF turnover is reduced in aging which causes IgG and albumin accumulation in the CSF and, in turn, a higher-than-expected CSF-to-plasma ratio (Sakka, Coll, & Chazal, 2011).

Table 1. IgG Quotient (QIgG) values for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Nondemented (ND) Subjects.

Table 1 lists historical studies and more recent meta-analyses that indicate minimal to no barrier impairment for IgG (i.e., QIgG < 0.01) in AD and ND subjects. References: (Elovaara, Icen, Palo, & Erkinjuntti, 1985; Elovaara, et al., 1983; Frolich, et al., 1991; Hampel, Kotter, Padberg, Korschenhausen, & Moller, 1999; Kay, et al., 1987; Leonardi, Gandolfo, Caponnetto, Arata, & Vecchia, 1985; Muszynski, et al., 2017; Sjögren, et al., 2001).

| Study | Age (ND) | Age (AD) | N (ND) | N (AD) | QIgG (ND) | QIgG (AD) | Fold-change (AD / ND) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| Elovaara et al. (1983) | 67.4 | 1.3 | 67.1 | 1.3 | 22 | 22 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 1.42 | < 0.01 |

| Elovaara et al. (1985) | 71.5 | 1.4 | 73 | 2.2 | 10 | 10 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.63 | < 0.01 |

| Leonardi et al. (1985) | 43.1 | 17.4 | 64.6 | 7.9 | 64 | 52 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 1.14 | NS |

| Kay et al. (1987) | 71.5 | 12 | 66.4 | 8.4 | 14 | 31 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.16 | NS |

| Frolich et al. (1991) | 68.8 | 5.7 | 69.1 | 8.3 | 25 | 25 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.23 | NS |

| Hampel et al. (1999) | 72.8 | 6.9 | 67.8 | 12 | 11 | 51 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 1.22 | NS |

| Sjögren et al. (2001) | 73.8 | - | 71.8 | - | 17 | 41 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 1.02 | NS |

| Muszynski et al. (2017) | - | - | - | - | 45 | 23 | 0.002 | - | 0.003 | - | 1.11 | 0.121 |

| No Impairment (0 < QIgG < 0.01) | Moderate Impairment (0.01 < QIgG < 0.03) | Severe Impairment (0.03 < QIgG < 0.1) | Breakdown (QIgG > 0.1) | |||||||||

Table 2. Albumin Quotient (QAlb) values for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Nondemented (ND) Subjects.

Table 2 lists historical studies and more recent meta-analyses that indicate minimal to moderate barrier impairment for albumin (i.e., 0.01 < Qalb < 0.03) in AD and ND subjects. References: (Alafuzoff, et al., 1983; Bjerke, et al., 2011; Blennow, Wallin, & Chong, 1995; Blennow, Wallin, Uhlemann, & Gottfries, 1991; Chalbot, et al., 2011; Elovaara, et al., 1985; Frolich, et al., 1991; Hampel, et al., 1999; Janelidze, et al., 2017; Kay, et al., 1987; Kim, et al., 2009; Leonardi, et al., 1985; Mecocci, et al., 1991; Musaeus, et al., 2020; Rösler, Wichart, & Jellinger, 2001; Sjögren, et al., 2001; Sjögren, et al., 2002; Sjogren, Gustafson, Wikkelso, & Wallin, 2000; Skillback, et al., 2017; Skoog, et al., 1998; Sun, Liu, Nguyen, & Bing, 2003; Sundelöf, et al., 2010; Wada, 1998).

| Study | Age (ND) | Age (AD) | N (ND) | N (AD) | QIgG (ND) | QIgG (AD) | Fold-change (AD / ND) | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| Kim et al. (2015) | 60.6 | 2.3 | 60.4 | 6.2 | 25 | 32 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 1.18 | NS |

| Sjögren et al. (2000) | 71.1 | 7.3 | 62 | 5.6 | 18 | 21 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.21 | NS |

| Leonardi et al. (1985) | 43.1 | 17.4 | 64.6 | 7.9 | 64 | 52 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 1.1 | NS |

| Alafuzoff et al. (1983) | 69 | - | 65 | - | 16 | 20 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 1.27 | < 0.05 |

| Sjögren et al. (2000) | 71.5 | 5.2 | 66 | 7.8 | 32 | 60 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.97 | NS |

| Kay et al. (1987) | 65.4 | 12 | 66.4 | 8.4 | 14 | 31 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.08 | NS |

| Elovaara et al. (1985) | 67.4 | 1.3 | 67.1 | 1.3 | 22 | 22 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 1.39 | <0.01 |

| Hampel et al. (1999) | 72.8 | 6.9 | 67.8 | 12 | 11 | 51 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.02 | - |

| Bjerke M et al. (2011) | 68 | - | 68 | - | 30 | 30 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 1.01 | NS |

| Rösler et al. (2001) | 45.2 | 2.1 | 68.7 | 2.1 | 49 | 27 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 1.27 | NS |

| Rösler et al. (2001) | 45.2 | 2.1 | 68.7 | 2.1 | 49 | 27 | 0.003 | 0 | 0.004 | 0 | 1.4 | NS |

| Frolich et al. (1991) | 68.8 | 5.7 | 69.1 | 8.3 | 25 | 25 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 1.23 | NS |

| Chalbot et al. (2011) | 59.4 | 9.2 | 69.3 | 4.3 | 21 | 54 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.92 | NS |

| Sjögren et al. (2002) | 68.6 | 7.5 | 70.6 | 5.3 | 17 | 19 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 1.12 | NS |

| Blennow et al. (1991) | 71.5 | 11 | 71.8 | 7.3 | 50 | 118 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 1.2 | - |

| Sjögren et al. (2001) | 78.9 | - | 71.8 | - | 17 | 19 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 1.49 | NS |

| Rosengren et al. (1999) | 66 | 6.4 | 71.9 | 5 | 39 | 37 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 1.11 | NS |

| Blennow et al. (1995) | 64.6 | 6.2 | 72 | 7.5 | 32 | 45 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 1.31 | < 0.01 |

| Elovaara et al. (1985) | 71.5 | 1.4 | 73 | 2.2 | 10 | 10 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 1.67 | <0.01 |

| Mecocci et al. (1991) | 60 | 4.1 | 73.3 | 1.3 | 17 | 46 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.86 | - |

| Sjögren et al. (2000) | 71.1 | 7.3 | 73.4 | 3 | 18 | 21 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 1.25 | NS |

| Janelidze et al. (2017) | 75 | 6 | 76 | 7 | 65 | 75 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.003 | 1.21 | <0.001 |

| Wada (1998) | 78.6 | 2.4 | 77.6 | 0.3 | 7 | 14 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Sundelöf et al. (2010) | 70.1 | 9.7 | 77.7 | 9.2 | 28 | 101 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 1.12 | NS |

| Chalbot et al. (2011) | 59.4 | 9.2 | 80.4 | 3.3 | 21 | 54 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 1.02 | NS |

| Skoog et al. (1998) | 85 | - | 85 | - | 29 | 13 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 1.37 | 0.046 |

| Sun et al. (2003) | 61 – 77 | - | 52 – 85 | - | 11 | 141 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0 | 1.23 | - |

| Musaeus et al. (2020) | 65.9 | 7.5 | 72.6 | 8.9 | 34 | 289 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 1.33 | 0.004 |

| Skillback et al. (2017) | 73 | 5 | 75 | 6 | 292 | 666 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.003 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| Skillback et al. (2017) | 73 | 5 | 75 | 6 | 292 | 130 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 1.15 | NS |

| No Impairment (0 < Qalb < 0.01) | Moderate Impairment (0.01 < Qalb < 0.03) | Severe Impairment (0.03 < Qalb < 0.1) | Breakdown (Qalb > 0.1) | |||||||||

3.2. Permeability Coefficients

Perfusion-based neuroimaging provides another alternative for measuring barrier leakage in AD patients. The rationale for perfusion-based imaging is that intravenously infused contrast agents (i.e., water-soluble paramagnetic compounds) alter the properties of water as it reaches different parts of the brain, resulting in an increased contrast during brain scans. Before the 2000s, barrier leakage was assessed by X-ray or CT imaging using iodinated contrast agents such as Hypaque-76 (1.45 kDa) or Conray-60 (0.81 kDa), or by PET imaging using 68Ga-EDTA (1.23 kDa) to obtain blood-to-brain transfer coefficients. In 1987, Schlageter et al. (Schlageter, Carson, & Rapoport, 1987) took the first PET-based measurements of barrier leakage in AD patients (n=5) and non-demented individuals (n=5) following an infusion of 2.5–5 mCi 68Ga-EDTA. In their study, Schlageter et al. (Schlageter, et al., 1987) acquired radioactivity-based PET scans over 90 minutes and found that k1 values (1.2 × 10−3 min−1) were similar for both cohorts. In 1990, Dysken et al. (Dysken, Nelson, Hoover, Kuskowski, & McGeachie, 1990) used a dynamic computed tomography (CT) scan setup with enough sensitivity to be able to capture Hypaque-76 (45 mL, 76% solution) leakage into the brain tissues of AD patients (n=26) and non-demented individuals (n=26). Dysken et al. (Dysken, et al., 1990) observed that the washout rate for Hypaque-76 was 3.7-fold lower (p > 0.05) in AD patients compared to that in non-demented individuals when brains were scanned at a higher spatial resolution (0.3 cm compared to 2.89 cm in Schlageter et al. (Schlageter, et al., 1987)) and over multiple regions of interest (16 compared to 2 in (Schlageter, et al., 1987). Under the current AD diagnostic criteria, the AD patients studied by Schlageter and co-workers would fall under the mixed dementia category. In 1998, Caserta et al. (Caserta, Caccioppo, Lapin, Ragin, & Groothuis, 1998) further improved the spatial resolution of dynamic CT scans and found in AD patients (n=14) a higher leakage rate for Conray-60 (2 mL/kg; 60% solution; ~ 0.005 min−1) compared to 68Ga-EDTA (~ 0.0012 min−1 in (Schlageter, et al., 1987)). However, k values for AD patients (n=14) were not significantly different from those of non-demented individuals (n=9). Despite improved imaging methods, PET and dynamic CT imaging are limited by long scan times (Raja, Rosenberg, & Caprihan, 2018) that can be overcome by DCE-MRI-based imaging methods (Raja, et al., 2018). While CT or MRI-based methods detect tracer concentrations in the sub-millimolar range, PET-based methods can detect tracer concentrations in the picomolar range. T1 signal intensities can then be used to obtain permeability coefficient (Ktrans) using comprehensive pharmacokinetic models such as the Tofts standard model, Tofts extended models, and the Patlak model (Patlak, Blasberg, & Fenstermacher, 1983; Tofts, et al., 1999). In the next two paragraphs, we will briefly discuss advances in DCE-MRI studies in 1) patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and in 2) AD patients.

MCI Patients.

Early DCE-MRI analyses by Wang et al. (H. Wang, Golob, & Su, 2006) show that Ktrans values were similar in the cerebelli and hippocampi of MCI patients (7 males, 4 females) and non-demented individuals (5 males, 6 females). In this study (H. Wang, et al., 2006), both treatment groups received Omniscan (Gd-DTPA-BMA; 0.57 kDa; 0.11mmol/kg i.v.) prior to a 5-minute T1-weighted DCE-MRI scan (1.5 T). More recent DCE-MRI studies revealed significant differences in the hippocampal Ktrans values between MCI patients and non-demented individuals at a higher magnetic field strength (3 T) (Barnes, et al., 2016; Montagne, et al., 2015; Montagne, et al., 2020; Nation, et al., 2019). In these studies, subjects were infused with gadobentate dimeglumine (1.06 kDa; 0.05 mmol/kg), and scans were acquired over 10–30 minutes at a temporal resolution of 15.4 s per scan (Barnes, et al., 2016). At these settings, mean Ktrans values were in the range of 0.5 – 2 × 10−3 min-1. Further, mean Ktrans values in the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus were 1.2-fold higher in MCI patients (20 females, 19 males) compared to mean Ktrans values in non-demented individuals (130 females, 76 males; (Montagne, et al., 2020)). In contrast, in other brain regions, Ktrans values were not significantly different. This pattern was consistent even after adjusting for several cofactors such as age, APOE status, Aβ and tau pathology, vascular risk factors, tissue volume, and cognitive scores. Taken together, in MCI patients, barrier leakage occurs in the hippocampus and is subtle (~ 1 kDa; ~10−3 min−1).

AD Patients.

A DCE-MRI analysis by Starr et al. (Starr, Farrall, Armitage, McGurn, & Wardlaw, 2009) shows that gadobentate dimeglumine (1.06 kDa; 20 ml administered intravenously at a rate of 5 ml/s) distributes differently in the CNS of AD patients (5 males, 10 females) compared to non-demented individuals (10 males, 5 females). Specifically, T1 signal intensities in the gray matter reached a local maximum value 15 minutes post-injection in AD patients compared to 26 minutes in non-demented individuals. A similar trend was observed in the CSF of both groups. Data from recent DCE-MRI studies show that low molecular weight gadobutrol (0.6 kDa; 0.1 mmol/kg) provided detectable Ktrans values for AD patients and non-demented individuals under a dual-time resolution MRI sequence scanning protocol (Freeze, et al., 2020; van de Haar, Burgmans, et al., 2016; van de Haar, et al., 2017; van de Haar, Jansen, et al., 2016; Verheggen, et al., 2020). This approach provides temporal resolution at the expense of reduced spatial resolution for the first 2 minutes of scanning. Consequently, Ktrans values across different brain regions were 10-fold lower in AD patients (~10−4 min−1; n=7) than in MCI patients (~10−3 min−1; n=9) (van de Haar, Burgmans, et al., 2016). After noise correction, Ktrans values were 13-fold higher (p=0.014) in AD patients (n=16; 9 males, 7 females) compared to non-demented subjects (n=17; 11 males, 6 females) (van de Haar, et al., 2017). This difference was significant for longer scan times (>14 minutes), indicating that noise can lead to an underestimation of Ktrans values for shorter scan times (< 15 min). Taken together, these studies show that barrier leakage is subtle (< 1 kDa) but significantly higher in AD patients compared to MCI patients or non-demented individuals.

3.3. Cerebral Microbleeds

Non-perfusion-based neuroimaging allows detection of cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) as indirect evidence for barrier leakage in patients and postmortem brain tissue. CMBs are 2–10 mm round, hemosiderin-rich deposits that appear as dark spots under a T2-weighted gradient echo or susceptibility-weighted MRI scan (Greenberg, et al., 2009; Nakata, et al., 2002). Anatomically, CMBs are associated with arteries, arterioles, and capillaries, but the association between CMBs and each vascular segment is unclear (Fisher, French, Ji, & Kim, 2010). Multiple studies indicate that CMBs are common in AD and CAA patients and are significantly (p < 0.05) more prevalent in AD patients compared to non-demented control individuals (Table 3) (K. Jellinger, 2002; K. A. Jellinger, 1997; Kalaria, 1997; Nakata, et al., 2002). Among AD patients, the number of CMBs increase with age (> 75+ years), severity of CAA pathology, cerebrovascular burden, and the presence of the APOE e4 allele (Benedictus, et al., 2013; Graff-Radford, et al., 2017; Kester, et al., 2014; Kimberly, et al., 2009; S. Lee, et al., 2018; Nakata-Kudo, et al., 2006; Pettersen, et al., 2008; Sparacia, et al., 2017; Vernooij, et al., 2008; Yates, et al., 2014). Regionally, CMBs are more prevalent in the lobar region compared to deep or infratentorial brain regions. Between the different lobes, CMBs are more prevalent in the occipital lobe, followed by the temporal lobe, frontal lobe, basal ganglia, parietal lobe, and cerebellum in AD patients (Banerjee, et al., 2017; Goos, et al., 2009; Nagasawa, Kiyozaka, & Ikeda, 2014; Olazaran, et al., 2014; Pettersen, et al., 2008; Shams, et al., 2015; Vernooij, et al., 2008). The prevalence of lobar CMBs is directly associated with severe white matter changes, low Aβ42 levels in the plasma, and high tau levels (p < 0.05) in the CSF of AD patients (Goos, et al., 2012; S. Lee, et al., 2018; Noguchi-Shinohara, et al., 2017; Sparacia, et al., 2017). Further, lobar CMBs are specific to AD and have not been observed in other dementias (Gungor, et al., 2015; Uetani, et al., 2013). CMBs are also closely related to barrier leakage in MCI. Specifically, Poliakova et al. (Poliakova, Levin, Arablinskiy, Vasenina, & Zerr, 2016) observed that MCI patients who develop CMBs (n=13) had 1.5-fold higher Qalb values (p < 0.05) compared to MCI patients without CMBs (n=12). In another study, Goos et al. (Goos, et al., 2012) found that AD patients with lobar CMBs (n=20) and non-lobar CMBs had similar Qalb values (n=15).

Table 3. Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs) in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Nondemented (ND) Subjects.

Table 3 lists selected studies that show CMB incidences in AD and ND subjects. References: (Brundel, et al., 2012; Doi, et al., 2014; Duits, et al., 2015; Goos, et al., 2012; Hanyu, Tanaka, Shimizu, Takasaki, & Abe, 2003; Kester, et al., 2014; Nagasawa, et al., 2014; Pettersen, et al., 2008; Uetani, et al., 2013).

| Study | Age (ND) | Age (AD) | N (ND) | N (AD) | MRI Settings | CMBs (ND, %) | CMBs (AD, %) | Fold-change (AD / ND) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||||

| Hanyu et al. (2003) | 75.6 | 6.6 | 77.3 | 6.5 | 55 | 59 | T2* GRE (1.5 T) | 7% | 68% | 9.32 | < 0.01 |

| Pettersen et al. (2008) | - | - | - | - | 25 | 80 | T2* GRE (1.5 T) | 12% | 29% | 2.4 | - |

| Brundel et al. (2012) | 72 | 4.5 | 74.3 | 8.6 | 18 | 18 | T2*GRE (7.0 T) | 57% | 78% | 1.36 | < 0.05 |

| Goos et al. (2012) | 65 | 6 | 67 | 6 | 22 | 52 | T2* GRE (3.0 T) | 0% | 50% | - | - |

| Uetani et al. (2013) | 54 | 108 | 6 | 24 | 75 | 71 | SWI (3.0 T) | 48% | 22% | 0.46 | < 0.001 |

| Kester et al. (2014) | 254 | 293 | 194 | 143 | 67 | 59 | T2* GRE (1.0, 1.5, 3.0 T) | 21% | 14% | 0.67 | < 0.05 |

| Yates et al. (2014) | 74.2 | 7.3 | 74.6 | 8.4 | 97 | 40 | SWI (3.0 T) | 22% | 43% | 1.96 | < 0.05 |

| Nasagawa et al. (2014) | 59 | 9 | 67 | 8 | 337 | 547 | T2* GRE (1.5 T) | 14% | 21% | 1.53 | - |

| Doi et al. (2015) | - | - | - | - | 18 | 72 | SWI (3.0 T) | 13% | 33% | 2.67 | < 0.05 |

| Duits et al. (2015) | 65 | 6 | 67 | 6 | 26 | 52 | T2* GRE (3.0 T) | 0% | 50% | - | - |

| GRE: Gradient Echo MRI | SWI : Susceptibility-weighted Imaging | ||||||||||