Abstract

Aims

To examine the effects of nursing deans/directors' transformational leadership behaviours on academic workplace culture, faculty burnout and job satisfaction.

Background

Transformational leadership is an imperative antecedent to organizational change, and employee well‐being and performance. However, little has been espoused regarding the theoretical and empirical mechanisms by which transformational leaders improve the academic workplace culture and faculty retention.

Design

A cross‐sectional survey design was implemented.

Methods

Nursing faculty employed in Canadian academic settings were invited to complete an anonymous online survey in May–July 2021. A total of 645 useable surveys were included in the analyses. Descriptive statistics and reliability estimates were performed. The moderated mediation model was tested using structural equation modelling in the Analysis of Moment software v24.0. Bootstrap method was used to estimate total, direct and indirect effects.

Result

The proposed study model was supported. Transformational leadership had both a strong direct effect on workplace culture and job satisfaction and an inverse direct effect on faculty burnout. While workplace culture mediated the effect of leadership on job satisfaction and burnout, the moderation effect of COVID‐19 was not captured in the baseline model.

Conclusion

The findings provide an in‐depth understanding of the factors that affect nursing faculty wellness, and evidence that supportive workplace culture can serve as an adaptive mechanism through which transformational leaders can improve retention. A transformational dean/director can proactively shape the nature of the academic work environment to mitigate the risks of burnout and improve satisfaction and ultimately faculty retention even during an unforeseen event, such as a pandemic.

Implication

Given the range of uncertainties associated with COVID‐19, administrators should consider practicing transformational leadership behaviours as it is most likely to be effective, especially in times of uncertainty and chaos. In doing so, academic leaders can work towards equitable policies, plans and decisions and rebuild resources to address the immediate and long‐term psychological and overall health impacts of COVID‐19.

Keywords: burnout, COVID‐19, faculty shortage, job satisfaction, nursing faculty, retention, transformational leadership, workplace culture

Why is this research needed?

Parallel to the global clinical nursing shortage, emerging studies allude to similar trends in the nursing faculty workforce.

The shortage of nurse faculty directly impacts and threatens the supply of clinical nurses available to provide quality patient care.

Employment conditions have long been identified as key factors affecting nursing faculty satisfaction and retention.

Transformational leadership has been associated with positive nurse job outcomes, however, its influence on nursing faculty burnout and satisfaction is limited.

What are the key findings?

Findings suggest that transformational leadership could improve faculty satisfaction and reduce burnout.

Drivers of the burnout epidemic and dissatisfaction among faculty are largely rooted in the work environment.

Supportive workplace culture is important to ensuring faculty engagement and retention.

This research contributes to the extant literature on leadership by identifying the mechanisms through which transformational leadership can improve the academic work environment and, ultimately, increase faculty retention.

1. INTRODUCTION

In its global scope and voracity, the COVID‐19 pandemic has profoundly impacted the nursing practice and academic workforce and has amplified pre‐existing issues in the work environment (e.g. staff shortages and heavy workload). Confronting these unparalleled challenges require immediate and far‐reaching organizational restructuring in workforce planning and modernization of traditional education content and delivery (WHO, 2020). As such, nursing leaders and educators are faced with enormous pressure to ensure a healthy workforce ready to respond to the ongoing public health crisis (WHO, 2020). In parallel with the frontline response, nurse academics have had to rapidly pivot to online teaching and learning following social distancing directives with little to no preparation. The sudden shift to the online educational system has placed new prohibitions on faculty, especially precarious (e.g. pre‐tenure) academics, and their ability to conduct research without lessening the demands/pressure to publish (Kınıkoğlu & Can, 2021). Concerns about the nursing workforce shortages coupled with the pressures of COVID‐19 and its multitudinous effects on the nursing profession may further exacerbate nursing attrition.

While the pandemic has been disastrous in many regards, it has presented a need for transformative leadership practices especially in nursing academia. During the last several decades, transformational leadership has emerged as one of the most effective operational leadership paradigms for 21st century leaders (WHO, 2020). Transformational leadership is particularly relevant in the context of high uncertainty, as the efficacy of such leaders is actualized during periods of chaos and change (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Through appreciation of context, transformational leaders focus on the relational aspects of leadership by building trust between themselves and their followers. Empirically, transformational leadership has been found to be effective in many settings, industries and organizations, including healthcare, government and public sectors (Boamah et al., 2018; Kim, 2014). Despite the wealth of research demonstrating the significance of transformational leadership, there is a dearth of empirical studies confirming its efficacy and relevancy in the nursing academic settings, and in the context of the COVID‐19 crisis. In this era of unprecedented change, transformational leadership may be ideologically suited for academic organizations.

This research was designed to investigate the effectiveness of transformational leadership in the nursing academic work environment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The present study proposes a moderated mediation model to signify the mechanism that underlies the effects of nursing deans/directors' transformational leadership on faculty job satisfaction and burnout, with workplace culture mediating the association between leadership and culture, and COVID‐19 as a moderator.

2. BACKGROUND

The conceptual and theoretical perspectives that informed this study are based on the tenets of Bass' (1985) transformational leadership theory and Leiter and Maslach's (2004) theory of burnout.

2.1. Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership is a process‐based leadership approach that focuses on empowering employees through inspirational motivation for employees to exert extra efforts for the benefit of the organization (Bass, 1985). Transformational leadership behaviours advance beyond the notion of economic and social exchanges (e.g. reward‐based systems) between leaders and followers by focusing on fostering collective optimism, stimulating team efficacy and energizing employees to achieve collective goals/visions beyond their capacity (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leadership theory suggests a four‐fold classification of leader behaviours: (1) idealized influence (emphasizes role modelling behaviours), (2) inspirational motivation (asserting purposes and expectations), (3) intellectual stimulation (instilling knowledge and creative thinking) and (4) individualized consideration (providing individualized approach to coaching and mentorship) (Bass, 1985). Each of the dimensions of transformational leadership serves as antecedents to employee empowerment and creativity (Boamah et al., 2018; Masood & Afsar, 2017), whereby the leader conveys a clear vision and builds trust and respect to motivate subordinates to forfeit their personal growth for the betterment of the team (Bass, 1985).

Transformational leadership has consistently been correlated with a wide range of work outcomes in the nursing clinical setting, such as enhanced nurse satisfaction, psychological engagement, innovative work behaviour (Boamah et al., 2018, Masood & Afsar, 2017), organizational commitment, reduced burnout (Wu et al., 2020), employee well‐being and willingness to stay in organization (Xie et al., 2020). In a sample of 378 Canadian nurses, Boamah et al. (2018) found that clinical nurses were most satisfied with their leaders who had a transformational leadership style. Experts credit successful outcomes of transformational leadership to its positive influence on workplace culture. Transformational leaders are known to create a culture of inclusivity and emphasize positive behaviours in the workplace. Such leaders provide structurally empowering working conditions that promote collegiality, autonomy and rational thinking. Given the positive effects of transformational leadership on clinical nurses, understanding its influence on the academic work environment/workplace culture is important to promoting retention.

2.2. Organizational (workplace) culture

Organizational/workplace culture refers to commonly held beliefs, standards, ideas and attitudes shared among individuals in organizations (Lund, 2003). These shared expectations, assumptions, implicit and explicit norms have a significant influence on employees' perceptions, attitudes and behaviours, which in turn, affect their performance (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006). Organizationally shared values and norms reflect employees' judgements of how things are and widely accepted practices that exist in the organization. The culture of an organization is inextricably bound to its diverse characteristics and inherent policies and practices that are perpetuated by top management (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006). Culture evolves over time and is important to sustaining and retaining the workforce.

Existing literature alludes to positive associations between supportive organizational culture and positive work outcomes such as employee well‐being, organizational commitment and intent to stay, and job satisfaction and reduced burnout (Burns et al., 2021; Masood & Afsar, 2017). In a 2020 study, Park and Pierce discovered an interesting result whereby the workplace culture mediated the association between transformational leadership and employees' commitment to the organization and lowered turnover intentions. Other investigators (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006; Xie et al., 2020) found that organizations with constructive/clan culture to be more successful as these environments foster supportiveness and embrace collective values, customs and social behaviour, while negative or defensive culture creates conformity and submissiveness and is associated with poor work attitudes such as divergence from evidence‐based practice, job burnout and staff turnover (Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006). Supportive organizational/workplace culture is an influential factor that has a profound effect on the efficacy and effectiveness of the organization in alleviating negative work‐related outcomes (Lund, 2003), and may potentially exacerbate or moderate the impact of COVID‐19 on mental health of faculty. Without a supportive workplace culture, stressful events such as COVID‐19, can weaken the effects of leadership, resulting in employee burnout.

2.3. Burnout

Burnout is a negative psychological disorder that arises from prolonged response to persistent ‘emotional and interpersonal job‐related stressors’ (Leiter & Maslach, 2004). Burnout is categorized as the triad of high emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a low sense of personal accomplishment (Leiter & Maslach, 2004). Emotional exhaustion is described as the main component of burnout characterized by feelings of fatigued and limited emotional resources. Depersonalization represents interpersonal dimension of burnout and is described as feelings of frustration, anger and cynicism and callousness towards others and about the profession. Reduced personal accomplishment refers to lack of self‐fulfilment and a sense of incompetence and a propensity to view oneself negatively in reference to work (Leiter & Maslach, 2004). Employees suffering from burnout symptoms tend to express lower level of work engagement and withdraw from providing input on organizational policies and operations.

Conceptually, burnout occurs when job demands (e.g. excessive workload) exceed job resources (e.g. professional relationships, autonomy and organizational culture). In a sample of 146 nursing faculty, Aquino et al. (2018) found that 27.52% of their study participants had desire to leave academia and among that group, up to 68.2% intend to leave in the next 6 years due to burnout. Female academics are reported to have higher likelihood of burnout and dissatisfaction because of dichotomy of work–life balance and unresolved interpersonal conflicts (Aquino et al., 2018). In a 2020 study, Wu et al. found positive associations between university faculty members' sleep hygiene and their experience of job burnout. Most studies on faculty burnout emphasize the effect of stress and excessive job‐related stressors, mainly heavy workload (Aquino et al., 2018), as causes of decline in mental and physical health (Alves et al., 2019), reduced performance and high staff turnover (Johnson, 2021). In contrast, others have found that those experiencing less burnout have more collegial support and wider social network in addition to having an open and transparent manager (Leiter & Maslach, 2004). Given that stress is related to burnout syndrome which gradually develops over time, it is especially important to understand the root causes/triggers of burnout to alleviate employee stress and improve job satisfaction.

2.4. Job satisfaction

The concept of job satisfaction has been well studied in the field of organizational behaviour because it is a key performance measure/outcome in an organization. Job satisfaction is defined as congruence between one's appraisal of their work and their work situations. Job satisfaction has been associated with the domains and demands of a person's job including task, workload and relationships with co‐workers, supervisor and organization (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). There are two dimensions of satisfaction: intrinsic satisfaction is a qualitative or subjective aspect of an individual's job contentment including autonomy, whereas extrinsic satisfaction relates to rewards, recognition and incentives that one receives in the work, and this may include work–life balance.

A host of studies have correlated higher levels of job satisfaction with key organizational outcomes including faculty autonomy, productivity, organizational commitment and quality of students and programme (Mamiseishvili & Lee, 2018; McNaughtan et al., 2022). In a Canadian province‐wide study, Tourangeau et al. (2014) found that nursing faculty had intention to remain employed in academia only if they were satisfied with these specific aspects of employment (e.g. job status, balanced work and life). Although job satisfaction is widely discussed in the nursing literature, dissatisfaction is still a persistent issue that affects retention (Boamah et al., 2021). In lieu of the rising concerns about the nursing faculty shortage and projections for future shortages in the nursing workforces, it is important to identify the key structural/organizational factors that influence job satisfaction among nurse academics as it is important to improving retention.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aims

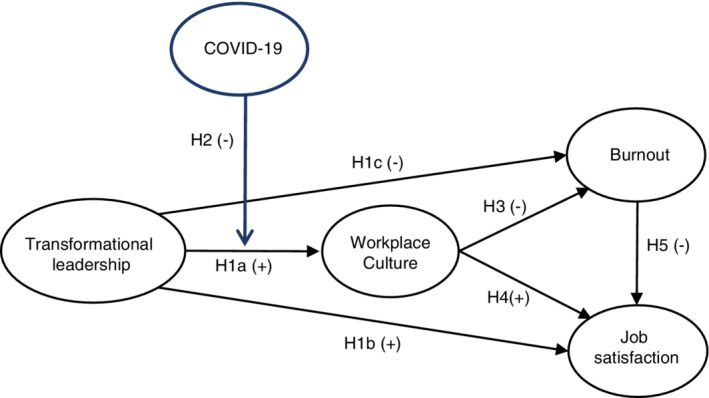

Based on the preceding discussion, this study was designed to test a hypothesized model in which workplace culture mediates the relationship between deans/directors' transformational leadership on the one hand, and nurse faculty burnout and job satisfaction on the other, with COVID‐19 predicted to moderate these relationships (see Figure 1). As such, the following hypotheses were proposed:

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized model

H1a Transformational leadership is positively related to supportive workplace culture.

H1b Transformational leadership is positively related to job satisfaction.

H1c Transformational leadership is negatively related to burnout.

H2 COVID‐19 pandemic moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and workplace culture.

H3 Supportive workplace culture is negatively related to burnout.

H4 Supportive workplace culture is positively related to job satisfaction.

H5 Burnout is negatively related to job satisfaction.

3.2. Design

A cross‐sectional design was implemented using data collected through a nationwide online survey of Canadian nursing faculty.

3.3. Participants

The target population were nurse faculty employed in both Canadian college and university settings. Eligibility included faculty members who held full‐time or part‐time instructional/teaching and/or research appointment (e.g. lecturer, teaching track and tenure track professor). Adjunct or visiting professors were excluded from analyses. No age restriction was placed on potential participants.

3.4. Data collection

Nursing faculty were identified through their institution's online faculty profile. Eligible participants were sent a recruitment request via email to complete an anonymous web‐based questionnaire using a Qualtrics survey link. Participants were provided a brief description about the study, study purpose and inclusion criteria. The survey contained a letter of information (LOI) explaining the study risks and benefits of participating in the study and measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of respondents (e.g. no names, institutional affiliation or tracking of electronic information). After reading the LOI, participants had an option to either exit the survey or consent to participate by completing the survey. Six weeks were allotted for the completion of the survey between May and July 2021. Non‐responders were sent an email reminder 3 weeks after their first invitation, and a subsequent remainder message 4 weeks thereafter to optimize response rates and ensure an adequate sample size (see Study Protocol for additional information). While there is no established formula to calculate sample size estimation in structural equation modelling, in the general filed, a sample of 200 participants or larger is preferred (see Kline, 2016).

3.5. Data analyses

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlations and reliability estimates were calculated for all the major variables using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS®) v.25.0. As part of data cleaning, univariate and multivariate assumptions, including normality (skewness and kurtosis), and other collinearity diagnostics were performed (Kline, 2016). All other maximum likelihood assumptions were met, indicating trustworthiness of the data. There were no missing values on any of the primary variables of interest.

To test the hypotheses, the main, indirect, moderating and moderated mediating effects were examined. The mediation effects were assessed using covariance‐based structural equation modelling (SEM) in the Analysis of Moment version 25.0 statistical software package. This analytical approach is preferred as it provides a direct and indirect test of the significance for testing mediation hypotheses (Kline, 2016). In this analysis, bias‐corrected non‐parametric bootstrapping techniques with 5000 bootstrap samples were used, which is a more robust test of the mediation hypothesis. If the 95% confidence intervals did not include 0, the point estimates of the indirect effects were considered statistically significant (see Hayes, 2018). Because mediation implies longitudinal causality, we cannot test for causal relationships in this present cross‐sectional study. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as non‐directional relationships (see Hayes, 2018).

To confirm the factorial validity and determine the psychometric properties of all the study instruments, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. The fit indices considered in the analyses were as follows: Chi‐square (χ 2) and significance (p), Chi‐square/degrees of freedom ratio (χ 2/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). While a low non‐significant Chi‐square value is preferred, the test of the difference between the proposed model and the ideal/just identified version of the model often produces a significant value (Hayes, 2018). According to Kline (2016), CFI and IFI values ≥.90 indicate good fit. However, for RMSEA, lower values (between 0 and .06) are optimal as they suggest a good fitting model.

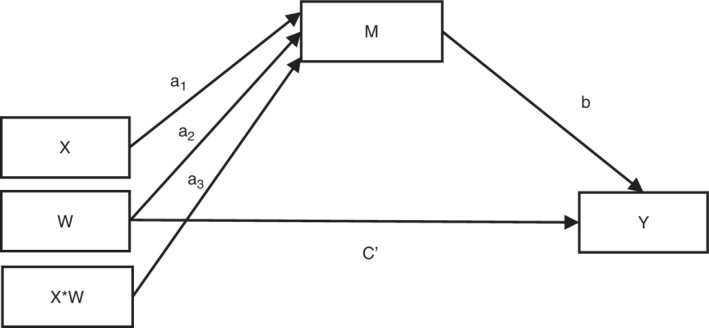

To test the moderation effect (Hypothesis 2), a normal theory‐based approach was used (Hayes, 2018). In the first step, the standardized values for the exogenous variables (transformational leadership and workplace culture) and the moderator variable (COVID) were computed. The variables were grand mean centred before completing the analysis to reduce the covariance between intercepts and slopes, thereby decreasing potential risk of multicollinearity in the interaction term (Hayes, 2018). In the second step, the interaction term was created using the mean‐centred values, which was entered into the model (see Figure 2). This inclusion of interaction term provided a test of the moderation effect. Moderated mediation occurs when ‘as the indirect effect changes, the value of the moderator variable also changes’ (see Hayes, 2018). If the null hypothesis is rejected, it provides support for the hypothesized moderation of the mediated, which means that there is an indirect effect (Hayes, 2018).

FIGURE 2.

The conceptual framework of the (first stage) moderated mediation model (statistical diagram by Preacher & Hayes, 2008)

3.6. Validity, reliability and rigour

The variables in this study were tested using well‐validated survey questionnaires.

3.6.1. Transformational leadership

Faculty perceptions of their deans/directors' transformational leadership were measured using the 20‐item Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ‐5X)–Short Rater Form (Bass & Avolio, 2000). The MLQ‐5X is a well‐established questionnaire consisting of four items from each of the dimensions of transformational leadership. Respondents rated the items on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (frequently, if not always). The MLQ‐5X has shown a satisfactory fit in a sample of nurses (Boamah et al., 2018). In this study, Cronbach's alpha of the scale was .97.

3.6.2. Workplace culture

While there are many classifications and measures of organizational/workplace culture, there are no consensus on which instrument best captures the essence of the construct, and certainly none exist in the nursing academic context. Hence, workplace culture was assessed using a six‐item measure created for the purposes of this study. The scale was designed to measure aspects of the academic work environment including role expectations, and process for promotion and/or tenure. Sample items include: ‘There is a sense of community within my department’ and ‘The process for promotion and/or tenure in my department is transparent’. The items were pre‐tested among a small sample of faculty members to establish surface/face validity and confirm that the items reflect the construct. All items were measured on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘Strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘Strongly agree’. Coefficient alpha derived from the sample was .85.

3.6.3. COVID‐19

The COVID‐19 variable was ascertained by six items dealing with the added demands and pressure of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Participants reported how the pandemic may have affected their job indicated by items such as: ‘COVID‐19 pandemic has disrupted my regular work responsibilities’ or ‘COVID‐19 pandemic has made my work responsibilities very challenging’. Prior to implementing the questionnaire, face validity was conducted to ensure that the content was suitable. Items were rated on a scale from 1 ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘Strongly agree’. The final scale had a range 6–30 and achieved an acceptable reliability (Cronbach's α of .85).

3.6.4. Burnout

Burnout was measured using the two dimensions/subscales of burnout—emotional exhaustion and depersonalization/cynicism of the Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey (MBI‐GS) (Leiter & Maslach, 2004), each consisting of five items. Items in this scale are proposed as statements relating to one's feelings about their work. For instance, emotional exhaustion is captured by questions such as ‘I feel emotionally drained from my work’ and ‘I feel burned out by my work’; and cynicism with questions such as ‘I have become less enthusiastic about my work’. Responds were rated on a 6‐point Likert scale from 0 = never to 6 = daily, which were added to form a score for each subscale/component of burnout. Burnout is identified with higher scores (≥3.0) on exhaustion and cynicism, whereas the opposite pattern reflects greater engagement (Leiter & Maslach, 2004). Each of these subscales have been well validated in past studies with nurses and have shown acceptable reliability. In this study, Cronbach's α was .95.

3.6.5. Job satisfaction

The Global Job Satisfaction (GJS) Questionnaire derived from the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman and Oldham, 1976) was used to assess job satisfaction. This is a four‐item scale that assesses perception of congruence or incongruence between oneself and the job (e.g. ‘I feel very satisfied with my job’). Responses were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale with higher scores indicating greater job satisfaction. To calculate the scores, the four items were summed and averaged. The GJS is well validated in CFA showing a good fit for the hypothesized factor structure and have achieved Cronbach's alphas of .79 and .86 in nursing samples (Boamah et al., 2018). In this study, there was an acceptable internal reliability (α = .88), with all item total correlations above r = .70.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Demographic characteristics

Of the 1649 eligible participants invited, 645 responded equating a 39.1% response rate. The vast majority of faculty self‐identified as females (93.6%) and White (83.1%). Eighty one percent reported being employed in a university, and over three‐quarters (76.1%) were either pre‐tenured or non‐tenured track faculty. Predominantly, respondents worked full‐time (70.2%), for more than 46 h per week (48.9%) and were either master's (54.9%) or PhD (31.9%) prepared. Overall, the study sample demographics/characteristics are comparable to that of the national demographic statistics of clinical nurses, indicating that our sample is reflective of the Canadian nursing population (Tourangeau et al., 2014). Additional sample demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents (n = 645)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤39 years | 145 | 22.5 |

| 40–49 years | 191 | 29.6 |

| 50–59 years | 195 | 30.2 |

| ≥60 years | 106 | 16.4 |

| Prefer not to say | 8 | 1.2 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 604 | 93.6 |

| Male | 36 | 5.6 |

| Other | 5 | .8 |

| Highest education | ||

| PhD | 206 | 31.9 |

| Masters | 354 | 54.9 |

| Bachelor | 79 | 12.2 |

| Diploma | 6 | 1.0 |

| Academic rank | ||

| Lecturer | 230 | 35.7 |

| Assistant Professor | 144 | 22.3 |

| Associate Professor | 82 | 12.7 |

| Full Professor | 88 | 13.6 |

| Clinical/sessional instructor | 101 | 15.7 |

| Tenure status | ||

| Tenured | 152 | 23.6 |

| Tenure track | 82 | 12.7 |

| Teaching track | 168 | 26.0 |

| Non‐tenure track | 149 | 23.1 |

| Clinical track | 92 | 14.3 |

| Employment status | ||

| Full‐time permanent | 453 | 70.2 |

| Full‐time temporary | 75 | 11.6 |

| Part‐time | 117 | 18.2 |

| Years worked in current organization | ||

| ≤1 year | 45 | 7.0 |

| 2–5 years | 200 | 31.0 |

| 6–10 years | 136 | 21.1 |

| >10 years | 264 | 40.9 |

| Hours worked per week | ||

| ≤35 h | 85 | 13.2 |

| 36–40 h | 122 | 19.0 |

| 41–45 h | 121 | 18.8 |

| >46 h | 314 | 48.9 |

| Institution type | ||

| University | 524 | 81.2 |

| College | 121 | 18.8 |

| Institution size | ||

| Small (<12,000) | 185 | 28.7 |

| Mid‐size (12,000–22,000) | 215 | 33.3 |

| Large (>22,000) | 245 | 38.0 |

4.2. Descriptive results for major study variables

Descriptive and inferential statistics including frequencies, means, standard deviations, reliability estimates and inter‐correlation matrix for each scale are presented in Table 2. All Cronbach's alphas were in acceptable ranges. On average, faculty reported moderate levels of transformational leadership in their deans/directors (= 2.04, SD 1.06) and workplace culture ( = 3.37, SD .74). Faculty reported high degree of burnout ( = 3.1, SD 1.65; score ≥3.0) (Leiter & Maslach, 2004), and were moderately satisfied with work (= 3.15, SD .99).

TABLE 2.

Correlations, means, standard deviations and reliabilities of major study variables

| Study variable |

|

SD | Number of items | Range | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transformational leadership | 2.04 | 1.06 | 20 | 0–4 | .97 | — | .62** | −.39** | .54** | |

| 2. Workplace culture | 3.37 | .74 | 9 | 1–5 | .85 | — | −.43** | .63** | ||

| 3. Burnout | 3.09 | 1.66 | 10 | 0–6 | .95 | — | −.66** | |||

| 4. Job satisfaction | 3.15 | .99 | 4 | 1–5 | .88 | — |

Abbreviations: , mean; α, Cronbach's alpha; SD, standard deviation.

Significant, p ≤ .001.

4.3. Mediation and moderated mediation analyses

In the SEM analyses, the independent variable (transformational leadership), mediator (workplace culture) and dependent variables (e.g. burnout and job satisfaction) were modelled along with their reflective indicators (items). All the correlation coefficients were in the expected direction, ranging from −.39 to .63. To simplify the presentation, only standardized coefficients are discussed here (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Estimated coefficients for path model

| Structural paths | β | CR | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | |||

| Transformational leadership ➔ Workplace culture | .631 | 17.492 | <.001 |

| Transformational leadership ➔ Burnout | −.248 | −4.887 | <.001 |

| Transformational leadership ➔ Job satisfaction | .185 | 5.048 | <.001 |

| Workplace culture ➔ Burnout | −.320 | −6.405 | <.001 |

| Workplace culture ➔ Job satisfaction | .307 | 8.429 | <.001 |

| Burnout ➔ Job satisfaction | −.515 | −13.217 | <.001 |

| Indirect effects | |||

| Transformational leadership ➔ Workplace culture ➔ Burnout | −.202 | — | <.001 |

| Transformational leadership ➔ Workplace culture ➔ Job satisfaction | .165 | — | <.001 |

Note: β = Standardized coefficient, CR, Critical ratio, p < .001.

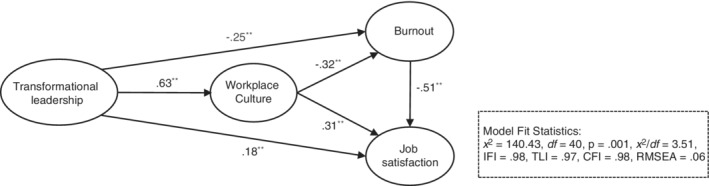

Results of the mediation analysis are presented in Figure 3. The study hypothesized model was supported as indicated by the model fit statistics: χ 2 = 140.43, df = 40, p = .001, χ 2/df = 3.51, IFI = .98, TLI = .97, CFI = .98 and RMSEA = .06. All path estimates were significant and in the hypothesized direction. Consistent with the hypotheses, transformational leadership had a strong and significant positive direct effect on workplace culture (β = .63, p < .001) [H1a] and job satisfaction (β = .18, p < .001) [H1b], and a negative effect on burnout (β = −.25, p < .001) [H1c]. Supportive workplace culture had a direct positive effect on job satisfaction (β = .29, p < .001) and a direct negative effect on burnout (β = −.29, p < .001), supporting Hypotheses 3 and 4 respectively. In turn, burnout had a strong negative effect on job satisfaction (β = −.52, p < .001), confirming support for Hypothesis 5.

FIGURE 3.

Mediation model predicting the effects of transformational leadership on burnout and job satisfaction through workplace culture. Standardized coefficients (**p < .001; *p ≤ .05). Bootstrap resample = 5000; percentile and bias‐corrected confidence intervals are on 95%

The effect of the moderator (COVID‐19) on workplace culture was negative and significant (β = −.29, p < .012); however, the moderated mediation effect, specifically the conditional indirect effect of the three‐way interaction term (transformational leadership × COVID‐19) on job satisfaction and burnout, through workplace culture was not significant (β = −.01, p < .102); therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

5. DISCUSSION

In this study, the role of transformational leadership and organizational/workplace culture as two possible factors on faculty job satisfaction and burnout was analysed to understand the dynamics of the academic work environment and strategies to improve nurse faculty retention. An important finding pertains to the direct and indirect effects of transformational leadership on faculty job satisfaction and burnout through workplace culture. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show such relationships among these constructs and in this setting. The findings not only lend support for suppositions of previous research on transformational leadership and workplace culture (Kim, 2014; Xie et al., 2020) but also go beyond earlier work by clarifying the underlying process of how transformational leadership directly and indirectly improves the work environment.

The analyses provide support for the hypotheses stated earlier, except for the three‐way interaction effect. The robust positive relationship found between transformational leadership and workplace culture has been confirmed in previous studies in various industries and disciplines, including healthcare (Boamah et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2020), business and other public sectors (Kim, 2014). The analyses revealed that deans/directors' who possess transformational leadership attributes can directly and indirectly influence faculty satisfaction and mitigate their risks of burnout by creating inclusive and supportive work environments. This is in line with the results reported by Wilkes et al. (2015) where 30 nursing deans from three countries (Canada, Australia and England) reported healthy workplace culture by exhibiting different ranges of transformational leadership styles, suggesting that transformational leadership may be an effective leadership style among academic nursing deans.

Consistent with previous research (Burns et al., 2021; Aarons & Sawitzky, 2006), supportive workplace culture was positively related to faculty satisfaction and lower burnout. This is a logical expectation in that a transformational dean/director is likely to create healthy workplace culture for faculty to thrive by displaying and reinforcing normative appropriate conduct including open communication, trust and respect among employees (Bass & Riggio, 2006). A 2020 study by Pavlovic et al. helps illustrate this point. They found university academicians/professors in three countries (Serbia, Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina) who perceived their organization to have positive culture were more satisfied. Both in and outside of academia, organizational culture is seen as the primary mechanism for improving employee motivation, satisfaction, productivity and longevity (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Burns et al., 2021). This implies that given the fluidity of the academic work environment, transformational deans/directors can develop, as well as sustain, effective policies and practices to ensure faculty well‐being and satisfaction.

Unsurprisingly, the analyses revealed a negative relationship between supportive workplace culture and faculty burnout, which in turn led to decreased job satisfaction. Similar results were reported by Burns et al. (2021), who found that supportive workplace culture reduces the risks of burnout among academic physicians, especially women. Other undesirable outcomes linked to faculty burnout in previous studies include work–life conflict, turnover and turnover intentions (Johnson, 2021), and reduced well‐being and quality of life (Alves et al., 2019). Given that drivers of the burnout epidemic are largely rooted in work environment, namely excessive workloads, work–life conflicts, lack of organizational support and leadership culture, it is important that effective solutions align with these drivers.

This study sought to go beyond simply examining the mediation in the transformational leadership–workplace culture linkage, by further identifying the three‐way moderation effect of COVID‐19, as it is relevant to the current context. Contrary to expectation, while the moderator was negatively and directly associated with workplace culture, it did not exert a moderating effect. In other words, the effect of COVID‐19 on the transformational leadership–culture linkage was not significant in the moderated mediated model. One possible reason for this finding is that faculty may have been drawing on their long‐standing perceptions and experiences of their work environment prior to the pandemic, as COVID‐19 is a relatively new phenomenon. Another possibility might be that COVID‐19 is viewed as temporary at the time of the study and that additional supports may have been put in place to deal with the immediate effects of the pandemic. Furthermore, the robust relationship between transformational leadership and culture (β = .63) may have suppressed the negative effects of COVID‐19. The non‐significant finding of the model could also be the lack of sufficient power desired to produce a significant three‐way interaction rather than lack of true population effect (Lorah, 2020). While there was no support found, the preliminary result is still meaningful as it provides a more comprehensive picture of how transformational leaders may be influential in sustaining a healthy workplace culture even during an unforeseen event, such as a pandemic.

5.1. Implication of the results and future research

The work presented in this study offers several theoretical and empirical contributions to extant leadership literature, along with practical/managerial implications. From a theoretical perspective, the findings may enable a better understanding of the role that work environment/culture play in the relationship between transformational leadership and nursing academic work outcome. From the perspective of theory development and advancement, the study posits that the effects of transformation leadership on faculty engagement, satisfaction and subsequent retention can be attributed to its ability to influence the academic workplace culture, thereby challenging the implicit assumption that leadership is context free. From a managerial standpoint, several conclusions drawn offer some guidance for academic leaders.

First, academic institutions should provide more leadership training for those in administrative positions. Those in direct supervisory roles (e.g. deans/directors) should consider learning transformational leadership as it is most likely to be effective, especially in times of uncertainty and chaos (Bass & Riggio, 2006). To be successful, transformational deans/directors need to be supported by senior administrators (e.g. Vice Provost, Provost and President). In the context of higher education, transformational leaders are needed to function as role models and ideal influencers to inspire and build confidence (trust) in their followers. Such leaders are employee centred, and therefore, will provide employees with empowerment, and individuation by creating working conditions that foster a sense of community, openness and flexibility, and establish a culture that helps support work–life integration.

Second, academic leaders and policy makers must be proactive in their approach and be mindful of the tone they set in the organizational culture and take it into account how these conditions affect employee satisfaction and retention. Nursing administrators/leaders must take active steps to build team‐based culture, provide positive feedback about faculty performance, maintain cohesion and prevent isolationism and ostracism. Furthermore, there needs to be institutional commitment for changes to organizational structure, policies and processes to address workload issues. Given the demands of the work, academic organizations must ensure that metrics for institutional success include faculty satisfaction and well‐being.

Third, this research provides further impetus for academic institutions to prioritize well‐being initiatives and implement strategies that promote positive workplace culture and prevent the exacerbation and risks of harm or burnout among faculty. Regardless of the locale of the organization, deans/directors should strive to endorse and improve aspects of organizational culture (in‐person or otherwise) that aid nursing faculty in achieving their goals and satisfaction and minimize those aspects of the culture that develop defensive reactions in employees. Given the range of uncertainties associated with COVID‐19, administrators should work towards equitable policies, plans and decisions and rebuild resources to address the immediate and long‐term psychological and overall health impacts of COVID‐19. Last, individually focused solutions, such as attention to self‐care, self‐efficacy training and stress management programmes, protected time, interpersonal relationship building and mentorship programmes (Boamah et al., 2021), must be employed as they have been shown to be effective in promoting a sense of community and connectedness among faculty, especially the pre‐tenured.

Although this study offers a unique perspective and focus on nursing faculty, with implications for the current workforce shortages, future studies should build on the findings of this study and develop and test other comprehensive models of transformational leadership and nursing faculty outcomes, including psychological and mental health impact of COVID‐19, and include other antecedents to leadership, burnout and job satisfaction as reciprocal causality may be a possibility when considering relationships among these variables. Future works on transformational leadership in Canadian academy should consider including other disciplines, such as medicine, STEM and rehabilitation, to further validate the outcomes of transformational leadership. More research is needed to examine how academic workplace culture mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and career satisfaction post‐COVID‐19.

6. LIMITATIONS

The following limitations need to be acknowledged: first, the data were based on faculty's subjective views/perspectives of their ‘leaders’ and organization. Although some critics of this type of study design may call for a more objective evaluation/assessment of leadership and the related outcomes, individual perceptions are central to the employee experience, and also self‐reported leadership is inherently biased due to overestimation of one's personal effectiveness. Another potential limitation is that the data were collected from Canadian nursing faculty, which may limit generalizability to academics in all disciplines and/or countries; however, the findings could still be readily generalized to a variety of different institutional climates. It is worth noting that other critical elements that may contribute to dissatisfaction and higher likelihood of burnout (e.g. being female, pre‐tenure and minority faculty) were not segregated in the analyses. Although the posited model was supported and suggests a direction of influence, it fails to conclusively support causation.

7. CONCLUSION

The main conclusion that can be drawn from this study is that nursing deans/directors should model transformational leadership in their daily behaviours, decisions and actions, especially during these unprecedented times, by creating inclusive workplace culture that embraces diversity, empowers faculty and improves their well‐being and satisfaction. With the awareness that the nursing workforce is at a tipping point with the ongoing workforce shortages, these findings have important implications for faculty, students, patient care and society at large. Thus, there is a need for evidence‐based interventions and strategies to address the drivers of burnout among nursing faculty. These interventions must be tailored to addressing the underlying causes and/or antecedents of burnout in the academic environment and extend beyond developing policy documents on social and professional conduct.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have agreed on the final version and meet at least one of the following criteria (recommended by the ICMJE [http://www. icmje.org/recommendations/]):

Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; and

Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

None.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15198.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#1477) prior to initiating the study and renewed annually throughout the study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sincere thanks are extended to the faculty members who participated in the study, and to Drs. Godwin Arku and Vanina Dal‐Bello Haas for commenting on and editing the initial draft.

Boamah, S. A. (2022). The impact of transformational leadership on nurse faculty satisfaction and burnout during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A moderated mediated analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 00, 1–12. 10.1111/jan.15198

Funding information

This work was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, grant number [430–2020‐01042].

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, SB. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (e.g. contains information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).

REFERENCES

- Aarons, G. A. , & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 33(3), 289–301. 10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, P. C. , Oliveira, A. D. F. , & Paro, H. B. M. (2019). Quality of life and burnout among faculty members: How much does the field of knowledge matter? PLoS One, 14(3), e0214217. 10.1371/journal.pone.0214217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, E. , Lee, Y. , Spawn, N. , & Bishop‐Royse, J. (2018). The impact of burnout on doctorate nursing faculty's intent to leave their academic position: A descriptive survey research design. Nurse Education Today, 69, 5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. (1985, 1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. , & Avolio, B. J. (2000). MLQ multifactor leadership questionnaire for research: Permission set (2nd ed.). Mind Garden. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. , & Riggio, R. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Routledge Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Boamah, S. A. , Callen, M. , & Cruz, E. (2021). Nursing faculty shortage in Canada: A scoping review of contributing factors. Nursing Outlook, 69, 574–588. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah, S. A. , Laschinger, H. K. , Wong, C. , & Clarke, S. (2018). Effect of transformational leadership on job satisfaction and patient safety outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 66(2), 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, K. , Pattani, R. , Lorens, E. , Straus, S. E. , & Hawker, G. A. (2021). The impact of organizational culture on professional fulfillment and burnout in an academic department of medicine. PLoS One, 16(6), e0252778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J. R. , & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. D. (2021). Predictors of teachers' turnover and transfer intentions: A multiple mediation model of teacher engagement. Journal of Education Human Resources, 39(3), 322–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. (2014). Transformational leadership, organizational clan culture, organizational affective commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior: A case of South Korea's public sector. Public Organizational Review, 14, 397–417. [Google Scholar]

- Kınıkoğlu, C. N. , & Can, A. (2021). Negotiating the different degrees of precarity in the UKacademia during the Covid‐19 pandemic. European Societies, 23(S1), S817–S830. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M. P. , & Maslach, C. (2004). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In Perrewé P. & Ganster D. C. (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and wellbeing (Vol. 3, pp. 91–134). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lorah, J. A. (2020). Interpretation of main effects in the presence of non‐significant interaction effects. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 16(1), 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, D. B. (2003). Organizational culture and job satisfaction. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(3), 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Mamiseishvili, K. , & Lee, D. (2018). International faculty perceptions of departmental climate and workplace satisfaction. Innovative Higher Education, 43, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, M. , & Afsar, B. (2017). Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior among nursing staff. Nursing Inquiry, 24(4), e12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughtan, J. , Eicke, D. , Thacker, R. , & Freeman, S. (2022). Trust or self‐determination: Understanding the role of tenured faculty empowerment and job satisfaction. The Journal of Higher Education, 93(1), 137–161. 10.1080/00221546.2021.1935601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, N. , Ivanis, M. , & Crnjar, K. (2020). Organizational culture and job satisfaction among university professors in the selected central and eastern European countries. Studies in Business & Economics, 15(3), 168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Park, T. , & Pierce, B. (2020). Transformational leadership and turnover intention in child welfare: A serial mediation model. Journal of Evidence‐Based Social Work, 17(5), 576–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J. , & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau, A. E. , Saari, M. , Patterson, E. , Ferron, E. M. , Thomson, H. , Widger, K. , & MacMillan, K. (2014). Work, work environments and other factors influencing nurse faculty intention to remain employed: A cross‐sectional study. Nurse Education Today, 34(6), 940–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, L. , Cross, W. , Jackson, D. , & Daly, J. (2015). A repertoire of leadership attributes: An international study of deans of nursing. Journal of Nursing Management, 23, 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020). State of the world's nursing 2020. Investing in education, jobs and leadership. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. , Dong, Y. , Zhao, X. R. , He, S. C. , & Zhang, X. Y. (2020). Burnout in university faculty: An interaction between subjective sleep quality and the OXTR rs2268498 polymorphism. Journal of Affective Disorders, 276, 927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y. , Gu, D. , Liang, C. , Zhao, S. , & Ma, Y. (2020). How transformational leadership and clan culture influence nursing staff's willingness to stay. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1515–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, SB. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions (e.g. contains information that could compromise the privacy of research participants).