Abstract

Purpose:

For reproductive-age women, medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) decrease risk of overdose death and improve outcomes but are underutilized. Our objective was to provide a qualitative description of reproductive-age women’s experiences of seeking an appointment for medications for OUD.

Methods:

Trained female callers placed telephone calls to a representative sample of publicly listed opioid treatment clinics and buprenorphine providers in Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia to obtain appointments to receive medication for OUD. Callers were randomly assigned to be pregnant or non-pregnant and have private or Medicaid-based insurance to assess differences in the experiences of access by these characteristics. The callers placed 28,651 uniquely randomized calls, 10,117 to buprenorphine-waivered prescribers and 754 to opioid treatment programs. Open-ended, qualitative data were obtained from the callers about the access experiences and were analyzed using a qualitative, iterative inductive-deductive approach. From all 28,651 total calls, there were 17,970 unique free-text comments to the question “Please give an objective play-by-play of the description of what happened in this conversation.”

Findings:

Analysis demonstrated a common path to obtaining an appointment. Callers frequently experienced long hold times, multiple transfers, and difficult interactions. Clinic receptionists were often mentioned as facilitating or obstructing access. Pregnant callers and those with Medicaid noted more barriers. Obtaining an appointment was commonly difficult even for these persistent, trained callers.

Conclusions:

Interventions are needed to improve the experiences of reproductive-age women as they enter care for OUD, especially for pregnant women and those with Medicaid coverage.

As the US opioid crisis has grown, women have been increasingly affected, with an exponential increase in the rate of overdose deaths among women of reproductive age over the last 20 years (Kochanek, Murphy, Xu, & Arias, 2019; Wilson, 2020). Treatment involving medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is highly effective in reducing overdose death and improving quality of life (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2019). For pregnant women, MOUD improve pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017; Maeda, Bateman, Clancy, Creanga, & Leffert, 2014; Price, 2017). Despite their effectiveness, there are substantial barriers in obtaining MOUD for reproductive-aged women (Patrick et al., 2018; Patrick et al., 2019). There are few studies of MOUD access for reproductive age women that include the qualitative assessment of individuals’ access experiences, yet this is an essential component of healthcare access and utilization (Phillippi, 2009). While some barriers to MOUD may be specific to communities (Sharp et al., 2018), there may be commonalities that could be addressed through local, state, and federal action.

Reproductive-age women are more likely than older women to have characteristics associated with decreased access to MOUD, including low socioeconomic status and public, rather than private, health insurance (Brown, Goodin, & Talbert, 2018; Dick et al., 2015; Martin, Hamilton, Osterman, & Driscoll, 2019; Saloner & Cook, 2013). Importantly, pregnancy can be a turning point that catalyzes women’s desire to reduce or stop opioid use (Goodman, Saunders, & Wolff, 2020); however, pregnant individuals may struggle to obtain MOUD during pregnancy and face criminal prosecution for drug use in pregnancy (Atkins & Durrance, 2020; Patrick et al., 2018). Women struggling with OUD have higher rates of previous trauma (Dube et al., 2003) and mental illness (Davis, Lin, Liu, & Sites, 2017) than the general population, potentially increasing the challenge of overcoming barriers to treatment.

The two primary medications for OUD prescribed in the United States for reproductive-age and pregnant women are methadone and buprenorphine (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017). Methadone is commonly prescribed and dispensed at federally regulated facilities, known as opioid treatment programs (OTPs), which require on-site dosing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2019). In contrast, buprenorphine can be prescribed by a broad range of outpatient providers who have received training and a waiver to prescribe it. Buprenorphine prescriptions can be filled at regular pharmacies (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2019). Buprenorphine-prescribing clinics are more common than OTPs. Despite evidence supporting MOUD, many of those who could benefit from MOUD do not receive it (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2019; Patrick et al., 2018; Patrick, Davis, Lehmann, & Cooper, 2015; Patrick et al., 2019). Few nationwide studies include the experiences of women seeking MOUD to understand the access process and improve utilization.

This research builds upon our previous quantitative research finding that pregnant women are less likely than non-pregnant women to receive appointments with buprenorphine prescribers (Patrick et al., 2020). To generate information that could help improve access, this study analyzes qualitative caller experience data collected during multi-state research to assess reproductive-age women’s experiences of obtaining appointments for MOUD. Randomization permitted systematic assessment of how experiences differed by characteristics associated with utilization differences in observation studies (Brown et al., 2018; Dick et al., 2015; Patrick et al., 2018; Saloner & Cook, 2013).

Materials and Methods

Design

Qualitative data were obtained as part of a randomized field experiment that used trained callers to attempt to obtain appointments for MOUD (Patrick et al., 2020). A hierarchical qualitative coding system, developed using an iterative, inductive-deductive approach based on the work of Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (2006) and Azungah (2018), was used to assess and distill the experiences of women obtaining MOUD.

Setting

In December 2018, we used publicly available sources maintained by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)—the Buprenorphine Practitioner Locator (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018a), and the Opioid Treatment Program Directory (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2018b)—to produce a comprehensive list of clinics/facilities from 10 states (Florida, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia). States were selected to obtain a diversity of the prevalence of opioid-related complications including overdose deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018) and state policies such as Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020). The research was deemed exempt from human subjects review by the University of Chicago and Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Data Collection

We used a ‘secret shopper’ approach where trained individuals mimicked patients (Bisgaier & Rhodes, 2011; Polsky et al., 2015; Tipirneni et al., 2015). Nine women ages 25–30 from diverse backgrounds and with vocal features consistent with White, Hispanic, or Black individuals were trained to call MOUD clinics, ask for an appointment, and log results. Calls were conducted between March 7th and September 5th2019. For each call, callers were assigned a clinic using a blocked randomization (Patrick et al., 2020). For each clinic, callers were assigned a name and a nearby address; each call was randomly assigned a pregnancy status (non-pregnant/pregnant) and an insurance status (private insurance/Medicaid insurance). Consistent with previous research, calls to OTP clinics were all assigned Medicaid (Patrick et al., 2018). If the assigned insurance was not taken by the clinic, the caller was instructed to ask to pay out-of-pocket as ‘self-pay.’

Scripts to standardize each caller’s queries and responses to questions were developed with input from experienced MOUD staff and providers at clinics outside of the target sample and then pilot tested (Patrick et al., 2020). Scripts were visible within a computer-assisted telephone interviewing system that permitted callers to enter information. Callers were instructed to not participate in lengthy screening beyond the script to avoid taking valuable clinic time. Appointments were cancelled at the end of the call.

The trained callers made 10,871 uniquely-randomized calls, 10,117 to buprenorphine-waivered prescribers and 754 to OTPs. They conducted an additional 17,780 repeat calls when the initial call did not result in a definitive answer. During and after the brief calls, callers could provide open-ended comments using text boxes for two questions: “Please give an objective play-by-play description of what happened in this conversation.” and “What did the clinic tell you about the waitlist?” From 28,651 total calls, there were 17,970 unique free-text comments.

Analysis

To understand women’s experiences of accessing MOUD appointments, we analyzed the qualitative data. Qualitative data coding and analysis were managed by a Qualitative Research Core, led by a PhD-level psychologist. Coding and analysis were conducted according to Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007). A hierarchical coding system was developed using a descriptive approach to describe the experiences of access and was based on the open-ended questions and a preliminary review of caller notes (RS) (Azungah, 2018; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Three experienced qualitative coders coded one-fourth of the callers’ notes. Coding was compared, and discrepancies resolved through discussion. After establishing reliability in using the coding system through independent coding by each team member and comparison of codes, one author completed the coding of remaining notes using the established coding system. Each caller note was treated as a separate quote and could be assigned up to 12 codes. Caller notes were combined and sorted by code. The coded quotes were managed using Microsoft Excel 2016 and SPSS version 26.0.

We then used an iterative inductive/deductive approach (Azungah, 2018; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Inductively, we sorted the coded notes by coding category and used the sorted quotes to identify higher order themes and relationships between themes. Deductively, we were guided by knowledge of the health care system and clinical knowledge of opioids and pregnancy. Major categories that emerged from the data included cost information, securing an appointment, referral, treatment information, and conversations. Major categories were further divided from one to eight subcategories, with each subcategory having additional hierarchical divisions. Definitions and rules were written for the use of each category. The coding system is included as an online supplement.

We organized the data describing the experiences of accessing an appointment for MOUD and arranged these comments in approximate chronological order as to when they took place within the call. Consistent with our qualitative methodology (Azungah, 2018; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006), we did not precisely quantify the number of responses in categories. We provide overarching comments on frequency if they reflect insurance status, pregnancy, or drug treatment type as a component of access. This approach is to validate all experiences, as each call would be meaningful to an individual seeking MOUD.

Results

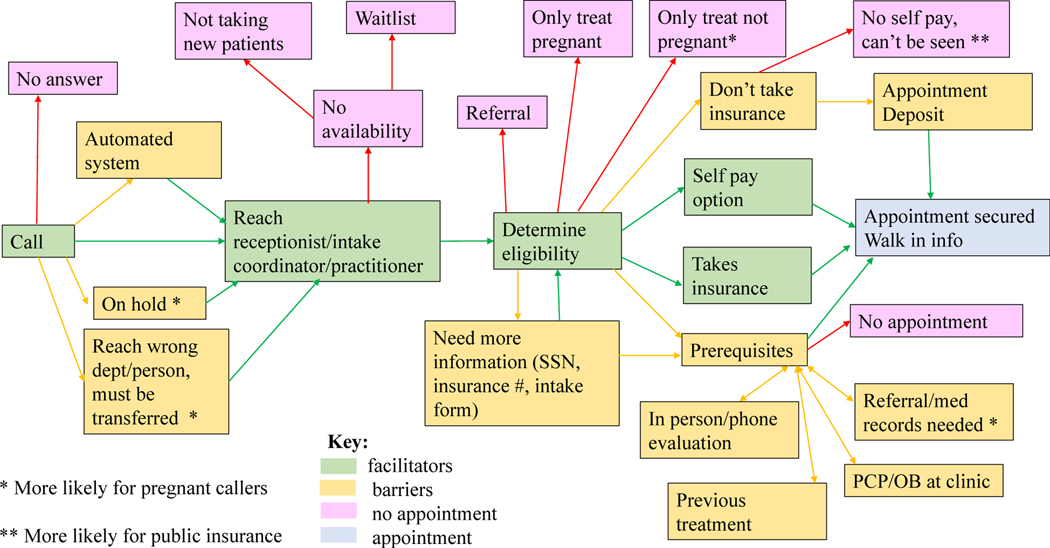

Consistent with COREQ guidelines, we use exemplar quotes to highlight women’s experiences. To contextualize the data for each quote, we note the numeric call identifier, the assigned pregnancy and insurance status, and the medication prescribed at the clinic (Tong et al., 2007). A visual synopsis of the experiences of attempting to make appointments is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Visual depiction of women’s experiences of obtaining an appointment for medications for opioid use disorder.

Call Process

The most straightforward process for the telephone interaction was for the caller to talk immediately to a staff member to secure an appointment. An easy path to an appointment was described by Caller 120031 (private insurance, buprenorphine). “I spoke with the receptionist, who confirmed that I would be seeing the listed provider. I was asked for my name, birthday, phone number, email, and whether or not I have insurance. I confirmed my insurance type…. I was offered an appointment at 3:00 pm (today).”

Callers were often placed on hold or transferred. Caller 111441 stated, “The wait time to speak with someone is crazy” (not pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). ‘Pregnant’ callers were more likely than ‘non-pregnant’ individuals to comment on holds and intra-office transfers as clinic staff checked if they could be seen. “I told them I was seeking addiction treatment and 4 months pregnant; they put me on the classic immediate hold” (143671, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Calls from ‘pregnant’ individuals were frequently transferred “many, many times” (140111, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). For example, caller 113382, “Waited almost 10 mins for the 1st rep to answer phone, she then transferred me to the scheduler which was an additional 5 mins. Rep eventually stated that they are not accepting new patients” (pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). Caller 143721, “was transferred maybe 4–5 times … only for me to end up talking to the 1st representative” (pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

The call could also go straight to a message stating the office did not have availability. The caller may reach an automated system that required action. Caller 143241 explained, “Automated system. Had to ask specifically for doctor on file….” (not pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). There could also be no answer to the call; less than half of first attempts resulted in an appointment (Patrick et al., 2020).

Once speaking to the correct person, some callers were told there were few open appointments, the clinic was not taking new patients, or a waitlist was the only option. Waitlist lengths were uncertain, “no idea how long it will take” (126931, nonpregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine) or ranged from “3–5 weeks” (122853, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). to “2 years” (111551, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). Limited availability was more often commented on by non-pregnant callers.

A clinic could also be at capacity fora specific insurance type or pregnancy status. For example, caller 161531 found one clinic was “not taking any NEW Medicaid patients” (pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). If the callers made it past the initial discussion, almost all were asked eligibility questions. Some clinics included questions about drug use or treatment history. Eligibility questions were more common for non-pregnant callers.

In the best-case scenarios, an appointment was rapidly secured. It was also possible that the callers were given ‘walk-in’ times and encouraged to come at their convenience. “It was walk-in hours only from 530am − 11am” (202571, pregnant, Medicaid, OTP).

The conversations between the caller and the receptionist/provider were often unremarkable. Some callers mentioned negative or positive experiences. Negative experiences included “rude” receptionists or “frustrating” calls. “The representative was not responsive” (Caller 108022, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). “She refused to give me times available before I gave her my credit card” (Caller 14776, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). Some callers received disparaging comments from the receptionist. “People usually don’t show up to appointments because they decide they want to have one last hoorah on dope before coming” (Caller 122731, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine).

Positive experiences included “warm” and welcoming conversations. For example, “Receptionist was also the owner and very friendly” (114672, non-pregnant, insurance, buprenorphine). Several women mentioned the publicly available number was the physician’s cell phone or home. Most experiences of reaching the provider directly were positive. “He … is a recovering addict, so felt he could empathize well with patients” (114861, non-pregnant, insurance, buprenorphine).

Those with public insurance sometimes described rude and abrupt comments when asking about self-pay options. Caller 133521 “inquired about self-pay with cash, she said that was against the law and very quickly hung up” (133521, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Caller 121911 was told she was “not a good fit” (non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine) after giving her insurance status and asking about selfpay. One caller’s self-pay inquiry was “[blown] off,” and staff suggested switching insurance plans (117021, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Several pregnant callers had negative experiences related to pregnancy status. “I was also told that if I did not follow this protocol, I would go into convulsions and possibly kill the baby” (102812, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Conversational tone affected some callers. “[The receptionist] spoke to me in a very slow speaking tone, as if I wouldn’t understand what she was saying. She told me I need to stop taking oxy because it’s not good for me, and I have another life to think about” (157061, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Another patient was criticized for not taking steps sooner: “I was told that I should have discussed the situation with my OB/GYN provider earlier and that I shouldn’t have waited this long” (108452, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). In contrast, other callers remarked about excellent experiences. “I would like to note that everyone I spoke with throughout the call (including the receptionist) was deeply empathetic, knowledgeable, and helpful” (101263, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Prerequisites to Treatment

Commonly noted barriers to securing an appointment were questionnaires or in-depth physical or mental health evaluations. “The result of the evaluation determines whether or not a patient qualifies” (104342, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Other clinics did not conduct evaluations but required referrals and/or records before establishing an appointment for all types of callers. Pregnant callers might need a referral from a maternity care provider; “they can’t progress to the appointment until [they get] a referral from the OB/GYN” (128951, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

For both pregnant and non-pregnant callers, some clinics asked for medical records for approval or to demonstrate necessity such as “proof of addiction” (114921, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). Clinics could require all medical care or primary care to be at their facility. This also included maternity care if pregnant: “I would need to start seeing the OB/GYN at their location, and I needed to switch it before I can be seen” (128172, pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine).

An additional barrier for some callers was a requirement for previous treatment. “You must first have completed an in-patient detox program” (146931, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). “They do not accept patients seeking treatment for the first time” (140301, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Pregnancy Status

While pregnant callers were not always given reasons why they could not be seen, some received information that the clinic did not have the ‘correct’ medication, and/or remarks about previous poor experiences with pregnant patients. “Find a provider who prescribes Subutex instead as it’s safer for the baby” (139022, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine). “Pregnant patients only should take Methadone, and he does not offer that” (102202, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Providers did not feel always comfortable treating pregnant patients, saying they were “afraid” (155282, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine), “didn’t feel comfortable” (103921, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine), or pregnant individuals were “too much of a high risk” (122031, pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). A few providers were adamant about not treating pregnant patients: “Absolutely not—would not treat you” (150701, pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine) or “Whoaaaaah, we don’t do that here, I won’t get into that mess again” (103921, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Pregnancy sometimes facilitated access as clinics offered to make special arrangements including coming in the day of call, Medicaid exception, and even price reduction. “I was told that pregnant patients take priority, and that I should be seen right away” (201771, pregnant, Medicaid, OTP). “My cost would be $35 weekly vs. the normal $118” (201241, Medicaid, OTP). There were also some cases in which clinics only treated pregnant patients and excluded non-pregnant individuals.

Insurance Status

Insurance status affected ability to get an appointment for MOUD. Callers with Medicaid reported more difficulties than those with private insurance. If callers assigned to have Medicaid reached a clinic that did not take their insurance, they were often unable to get an appointment. Callers with private insurance were often allowed to self-pay: “doesn’t take my insurance but offers cash pay” (119981, pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). Some Medicaid patients were told they could not pay out-of-pocket, as it would be illegal or fraud. This happened to both pregnant and non-pregnant callers. “A law passed preventing them from accepting cash from Medicaid patients” (112493, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine provider in Virginia). “It is considered fraud to allow patients to self-pay if they have insurance” (126211, non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine provider in Tennessee). However, it was not always the case that if Medicaid was not accepted, the patient could not be seen. Caller 158771 could not use her Medicaid, but could pay an “intake fee of $408” for an appointment (non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine provider in Florida).

Not all callers assigned private insurance were free from difficulties, as some clinics could take only Medicaid and not did provide a self-pay option. For example, caller 120142 “was told that I could not pay out-of-pocket. This is a public health organization that only accepts Medicaid recipients” (pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). Other clinics accepted some forms of private insurance but not the caller’s type: “This clinic does not accept my insurance and did not offer a self-pay option” (136811, non-pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine).

For callers with both private and Medicaid-based insurance, clinics did not always allow health insurance to pay for provider visits, but permitted its use for other aspects of treatment such as medication or laboratory tests. It was also possible that having Medicaid could result in subsidized, lower-cost treatment. For example, caller 203002 was informed she “may be eligible for a grant depending on my income, as [state Medicaid] is only partially accepted” (not pregnant, Medicaid, OTP). Other Medicaid-assigned callers were offered additional services, such as caller 200702, who was told “since I had Medicaid, if I needed a ride one could be arranged for free” (non-pregnant, Medicaid, OTP). Insurance type was one reason women were given a referral to another facility.

Clinics sometimes required money to secure an appointment. The need for immediate payment was more likely for non-pregnant patients, though it occurred across demographics. For example, caller 122732 was “told that in order to secure an appointment, I would need to either come in and make a cash payment of $250 or pay over the phone for an additional $10. I was told that this is required due to patients running off to party one last time and then not showing up” (non-pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Referrals

Women who could not be seen at a given clinic were sometimes given a referral to another provider or facility. Referrals included other substance use disorder treatment clinics, mental health services, specific doctors, and OB/maternal care, along with SAMHSA internet resources or telephone hotlines. Pregnant callers were sometimes referred to clinics that specialized in care of pregnant women. Others were told to “find someone through their OB/GYN” (107181, pregnant, private insurance, buprenorphine). However, regardless of patient status, referrals were not common, and many left the calls with no appointment or advice: “the receptionist very snappily said ‘We don’t treat pregnant women.’ I barely had enough time to thank her and say goodbye before she hung up” (119162, pregnant, Medicaid, buprenorphine).

Clinic Type

Callers encountered a wide range of different clinic types in their calls. Many barriers callers faced were the same across clinic types, including lack of availability, “not currently accepting new patients and no waitlist was offered” (200361, non-pregnant, Medicaid, OTP), or needing an initial evaluation. However, there were differences between OTP clinics and buprenorphine providers that affected access, including requirement for prior treatment and how care was scheduled and provided.

OTP clinics were more likely to require previous treatment than buprenorphine clinics, and women were sometimes required to have initial inpatient treatment then graduate to outpatient care. Caller 200172 explained, “I have to start detox first and then be transitioned into the outpatient addiction program” (non-pregnant, Medicaid, OTP).

Callers reaching OTP clinics were much more likely to be offered walk-in appointments, while buprenorphine providers more often had scheduled appointments. After intake, many of the OTP clinics had “dosing hours” to receive treatment, and occasional appointments with a provider or mental health personnel, while outpatient dosing was common for buprenorphine clinics.

Discussion

Reproductive-age women are increasingly being diagnosed with OUD (Kochanek et al., 2019; Patrick et al., 2015; Patrick et al., 2019; Wilson, 2020). MOUD treatment improves a range of short-and long-term outcomes and can vastly improve quality of life for women and their families (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2019). The moment of first contact is a unique opportunity to facilitate women’s entry into treatment and enhance their motivations to receive care (Heuston et al., 2001; Phillippi & Roman, 2013). Individuals needing MOUD may be experiencing stigma or shame, and the quality of these initial interactions may relieve or exacerbate these feelings, especially for women with anxiety or prior trauma (Stone, 2015; Stringer & Baker, 2018).

This multi-state randomized field experiment of MOUD access provides valuable information on the experiences of women, especially pregnant and low-income women, attempting to obtain MOUD. Qualitative findings revealed barriers of hold times, waits for appointments, unhelpful staff, and conflicting information about treatment and payment options as well as positive, welcoming experiences. Results are consistent with previous access to healthcare and perinatal care frameworks (Phillippi, 2009; Ricketts & Goldsmith, 2005).

Access to medical care has multiple components, including congruence of the care with an individual’s needs and preferences (Andersen, McCutcheon, Aday, Chiu, & Bell, 1983), and pregnancy may affect these perceptions (Phillippi, 2009). Factors influencing access occur along a spectrum ranging from clinical (e.g., local clinic characteristics) (Phillippi, Myers, & Schorn, 2014; Phillippi, Holley, Payne, Schorn, & Karp, 2016) to pervasive and systematic (e.g., structural inequities in resource allocation and cultural/personal biases) (Daw et al., 2020; Hardeman, Karbeah, & Kozhimannil, 2019). However, most access frameworks neglect the very personal and hyper-local interaction at the moment individuals begin to interface with medical care, including it only as a part of the overall clinic experience (Phillippi & Roman, 2013). For example, the importance of receptionists in facilitating or decreasing MOUD access has rarely been explored (Heuston et al., 2001).

Many women seeking opioid treatment have other commitments, including jobs and children needing care. Making multiple calls, often with long hold times, can be difficult to negotiate, and dead ends or interactions with unhelpful staff could discourage women from getting needed help, consistent with studies of adults’ barriers to MOUD (Feder, Mojtabai, Musci, & Letourneau, 2018). Requirements for cash payments, even for people with insurance, may be insurmountable for many individuals. In addition, inpatient treatment as a requirement to outpatient maintenance may be difficult for women with children. While in this qualitative research we did not quantify exactly how often women encountered pregnancy or insurance-related barriers, in our quantitative research, callers assigned to be pregnant or have Medicaid were significantly less likely to secure an appointment than non-pregnant women or those with private insurance (Patrick et al., 2020).

Study limitations include that trained callers may not experience stigma or emotions in the same manner as individuals seeking OUD treatment. The callers may have had more objective responses and been more likely to persist than women with OUD. In addition, the use of a text box for data capture may not have elicited descriptions as rich as those from interviews.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our research supports the need for a greater number of MOUD providers who serve individuals regardless of their pregnancy and/or insurance status; it also supports interventions to improve the experience of entering care, especially for pregnant women and those with Medicaid. In our findings, clinic receptionists often act as gatekeepers and greatly affect the experience of entering care. Training for first-contact staff focused on improving the access experience could improve MOUD utilization.

Policy implications of this work are wide-ranging. Our findings suggest that women of reproductive age who want treatment face substantial barriers, compounded by pregnancy, insurance status, and stigma, and they sometimes received inaccurate information about medication safety in pregnancy. To meet the growing need for treatment, state and federal programs could decrease administrative barriers and increase reimbursement, along with other changes, to decrease barriers to MOUD provision. To address safety, additional licensing or education requirements or clinician support could be provided, similar to some states’ requirement for opioid-related continuing medical education credits to maintain licensure. Overcoming challenges may require increased funding and coordination at federal, state, community, and facility levels. Women received comments expressing a lack of understanding of OUD in pregnancy, which could be overcome by enhanced training and increasing the numbers of maternity providers who prescribe buprenorphine.

Conclusions

There is inadequate access compared with demand for MOUD for childbearing age women, particularly those who are pregnant and/or have Medicaid. An increase in trained providers who are comfortable caring for pregnant individuals is needed. Strategies to improve utilization should also consider the experiences of entry into care, including attention to the first contact with the healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the University of Chicago Survey Lab for their work in data collection.

Funding/Support:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DA045729 (Patrick). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data Access and Responsibility: Julia Phillippi, Rebecca Schulte, Kemberlee Bonnet, and Stephen Patrick had full access to all the data in the study and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of data analysis.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2021.03.010.

Declarations of Competing Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2017). Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(2), e81–e94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, McCutcheon A, Aday LA, Chiu GY, & Bell R. (1983). Exploring dimensions of access to medical care. Health Services Research, 18(1), 49–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DN, & Durrance CP (2020). State policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse or neglect fail to achieve their intended goals: Study examines the effect of state policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse or neglect on the incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome and other factors. Health Affairs, 39(5), 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azungah T. (2018). Qualitative research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaier J, & Rhodes KV (2011). Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(24), 2324–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Goodin AJ, & Talbert JC (2018). Rural and Appalachian disparities in neonatal abstinence syndrome incidence and access to opioid abuse treatment. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Provisional drug overdose death counts. centers for disease control and prevention. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed: June 24, 2020.

- Davis MA, Lin LA, Liu H, & Sites BD (2017). Prescription opioid use among adults with mental health disorders in the United States. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(4), 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw JR, Kolenic GE, Dalton VK, Zivin K, Winkelman T, Kozhimannil KB, & Admon LK (2020). Racial and ethnic disparities in perinatal insurance coverage. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 135(4), 917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Burns RM, Leslie D, & Stein BD (2015). Growth in buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to opioid agonist treatment, 2002–11. Health Affairs, 34(6), 1028–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, & Anda RF (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder KA, Mojtabai R, Musci RJ, & Letourneau EJ (2018). US adults with opioid use disorder living with children: Treatment use and barriers to care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 93, 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, & Muir-Cochrane E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DJ, Saunders EC, & Wolff KB (2020). In their own words: a qualitative study of factors promoting resilience and recovery among postpartum women with opioid use disorders. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman RR, Karbeah JM, & Kozhimannil KB (2019). Applying a critical race lens to relationship-centered care in pregnancy and childbirth: An antidote to structural racism birth. Birth, 47(3), 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuston J, Groves P, Nawad JA, Albery I, Gossop M, & Strang J. (2001). Caught in the middle: receptionists and their dealings with substance misusing patients. Journal of Substance Use, 6(3), 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2020). Current Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions. Available: http://kff.org/health-reform/slide/current-status-ofthe-medicaid-expansion-decision/. Accessed: June 1, 2020.

- Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, & Arias E. (2019). Deaths : Final data for 2017 Hyattsville, MD. Available: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/79486. Accessed: August 7, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, & Leffert LR (2014). Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancytemporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 121(6), 1158–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, & Driscoll AK (2019). Births: Final Data for 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports, 68(13). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine. (2019). Medications for opioid use disorder save lives. Washington DC: National Academies Press. Accessed: June 23, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Buntin MB, Martin PR, Scott TA, Dupont W, Richards M, & Cooper WO (2018). Barriers to Accessing Treatment for Pregnant Women with Opioid Use Disorder in Appalachian States. Substance Abuse, 1–18, Accessed: January 1, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann C, & Cooper WO (2015). Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. Journal of Perinatology, 35(8), 650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Faherty LJ, Dick AW, Scott TA, Dudley J, & Stein BD (2019). Association Among County-Level Economic Factors, Clinician Supply, Metropolitan or Rural Location, and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. JAMA, 321(4), 385–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Richards MR, Dupont WD, McNeer E, Buntin MB, Martin PR, & Leech AA (2020). Association of pregnancy and insurance status with treatment access for opioid use disorder. JAMA network open, 3(8), e2013456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi J. (2009). Women’s perceptions of access to prenatal care in the United States: A literature review. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(3), 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi J, Myers C, & Schorn M. (2014). Facilitators of prenatal care access in rural Appalachia. Women and Birth, 27(4), e28–e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi JC, Holley SL, Payne K, Schorn MN, & Karp SM (2016). Facilitators of prenatal care in an exemplar urban clinic. Women and Birth, 29(2), 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi JC, & Roman MW (2013). The motivation-facilitation theory of prenatal care access. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 58(5), 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, Wissoker D, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, & Rhodes KV (2015). Appointment availability after increases in Medicaid payments for primary care. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(6), 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price TE (2017). Secretary Price Announces HHS Strategy for Fighting Opioid Crisis: Atlanta, Georgia. Available: https://www.hhs.gov/about/leadership/secretary/speeches/2017-speeches/secretary-price-announces-hhs-strategyfor-fighting-opioid-crisis/index.html. Accessed: July 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts TC, & Goldsmith LJ (2005). Access in health services research: The battle of the frameworks. Nursing Outlook, 53(6), 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner B, & Cook BL (2013). Blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to complete addiction treatment, largely due to socioeconomic factors. Health Affairs, 32(1), 135–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp A, Jones A, Sherwood J, Kutsa O, Honermann B, & Millett G. (2018). Impact of Medicaid expansion on access to opioid analgesic medications and medication-assisted treatment. American Journal of Public Health, 108(5), 642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. (2015). Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice, 3(1), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer KL, & Baker EH (2018). Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse treatment among those with unmet need: an analysis of parenthood and marital status. Journal of Family Issues, 39(1), 3–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018a). Buprenorphine practitioner locator. Available: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/practitioner-program-data/treatment-practitioner-locator. Accessed: December 2018.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018b). Opioid Treatment Program Directory. Available: https://dpt2.samhsa.gov/treatment/directory.aspx. Accessed: December 2018.

- Tipirneni R, Rhodes KV, Hayward RA, Lichtenstein RL, Reamer EN, & Davis MM (2015). Primary care appointment availability for new Medicaid patients increased after Medicaid expansion in Michigan. Health Affairs, 34(8), 1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, & Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N. (2020). Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.