Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic may have a disproportionate impact on people with dementia/mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to isolation and loss of services. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the effects of the COVID‐19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in people living with dementia/MCI. Two authors searched major electronic databases from inception to June 2021 for observational studies investigating COVID‐19 and NPS in people with dementia/MCI. Summary estimates of mean differences in NPS scores pre‐ versus post‐COVID‐19 were calculated using a random‐effects model, weighting cases using inverse variance. Study quality and risk of bias were assessed by the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. From 2730 citations, 21 studies including 7139 patients (60.0% female, mean age 75.6 ± 7.9 years, 4.0% MCI) with dementia were evaluated in the review. Five studies found no changes in NPS, but in all other studies, an increase in at least one NPS or the pre‐pandemic Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) score was found. The most common aggravated NPS were depression, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and apathy during lockdown, but 66.7% of the studies had a high bias. Seven studies including 420 patients (22.1% MCI) yielded enough data to be included in the meta‐analysis. The mean follow‐up time was 5.9 ± 1.5 weeks. The pooled increase in NPI score before compared to during COVID‐19 was 3.85 (95% CI:0.43 to 7.27; P = 0.03; I 2 = 82.4%). All studies had high risk of bias. These results were characterized by high heterogeneity, but there was no presence of publication bias. There is an increase in the worsening of NPS in people living with dementia/MCI during lockdown in the COVID pandemic. Future comparative studies are needed to elucidate whether a similar deterioration might occur in people without dementia/MCI.

Keywords: COVID‐19, dementia, mild cognitive impairment neuropsychiatric symptoms

The COVID‐19 pandemic has had negative physical and psychological effects, among those who contracted the virus SARS‐CoV‐2 and subsequently COVID‐19, as well as those who simply lived through the pandemic. 1 People with dementia had high rates of hospitalisations and mortality when infected with SARS‐CoV2, but they were also impacted by COVID‐19 in other ways. 2 , 3

People living with dementia might be more vulnerable to exposure to COVID‐19 infection due to their advancing age, comorbidities, reduced cognitive and physical reserve capacities, difficulties in following and maintaining physical distance recommendations, and difficulties in understanding, following and remembering other COVID‐19 prevention measures. 4 , 5 During “lockdowns” implemented by governments to achieve a reduction in social contact, lasting approximately 2 years, physical activity and social interaction, which are considered as modifiable risk factors in the development and progression of dementia, were limited. 6 , 7 Moreover, it may be difficult for people living with dementia compared to those who are dementia‐free to use telecommunications to maintain social connections, or participate in home‐based physical activity programmes. 8 In addition, since similar limitations are experienced in terms of caregivers, the caregiver burden has increased during the lockdown. 9 Moreover, all the negative situations experienced in this COVID‐19 pandemic were not only valid for patients living with dementia, but also for patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). 4 , 10 , 11

Given the aforementioned factors, it may be hypothesized that COVID‐19 restrictions could have worsened the neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of these patients. 12 , 13 However, there are inconsistent results regarding this issue in the literature. 14 , 15 Therefore, the aim of this review is to examine the effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on NPS in people living with dementia or MCI.

METHODS

This systematic review was conducted according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) criteria, 16 and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 17 The review followed a predetermined, but unpublished protocol that can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Search strategy

Four electronic databases, MEDLINE, Scopus, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central, were searched, targeting reports published from database inception to 2 June 2021 with no language restrictions. The search terms used were (dement* OR Alzheimer* OR Lewy OR Posterior cortical atrophy OR Binswanger OR Progressive supranuclear palsy OR Frontotemporal disorder* OR Frontotemporal degeneration OR Corticobasal degeneration OR Corticobasal syndrome OR Mild cognitive impairment) AND (COVID‐19 OR Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia OR 2019 novel coronavirus OR 2019‐nCoV OR SARS‐CoV‐2).

The included studies were published as observational quantitative studies of a cross‐sectional or longitudinal design. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) being a study conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic; (ii) involving patients with a prior diagnosis of dementia or MCI; and (iii) reporting the prevalence or incidence value of one or more NPS. Studies were excluded if they were qualitative or thematic studies.

Data extraction and statistical analyses

The literature search, assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria, quality of studies, and extraction of data were independently undertaken and verified by two authors (PS, LS). The results were then compared, and, in case of inconsistency, consensus was reached with the participation of a third author (NV). Conference abstracts and minutes of relevant conferences relating to dementia or geriatric medicine included in the databases were also searched. The following information was extracted: (i) characteristics of the study population (e.g., sample size, demographics, country in which the study was performed); (ii) setting in which the study was performed; (iii) presence of MCI or dementia; (iv) dementia type; (v) type of NPS and method of evaluation; (vi) the mean time between the assessment prior to the outbreak of the pandemic and the assessment that took place during the COVID‐19 crisis.

Data regarding the incidence or prevalence of NPS were reported descriptively. Studies in which NPS were evaluated using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) before and after the pandemic were summarized using a meta‐analytic approach.

META‐ANALYSIS METHOD

Studies reporting NPI values before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown were included in the meta‐analysis. Due to the anticipated heterogeneity, a random‐effects model was applied, weighting cases using inverse variance, calculating mean differences in NPI scores pre versus post COVID‐19 with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using STATA 14.0. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the I 2 statistic for all analyses, with 0–50% being classified as low, 50%–75% moderate, and >75% high heterogeneity. 18 In cases of high heterogeneity, meta‐regression analyses were performed on available data, including mean age, percentage of females, stage of minor and major neurocognitive disorder, percentage of people having MCI, and lockdown duration. Publication bias was assessed with a visual inspection of the funnel plot and the Egger bias test. 19 Finally, to test the robustness of results, a sensitivity analysis using the one‐study removed method was conducted.

Assessment of study quality/risk of bias

Study quality was assessed independently by two investigators (MT, PS) using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). This scale has been adapted from the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies to perform a quality assessment of cross‐sectional studies and cohort studies for the systematic review. A third reviewer was available for mediation (SGT). The NOS assigns a maximum of nine points based on three quality parameters: selection, comparability, and outcome. 20 NOS scores were categorized into three groups: very high risk of bias (0 to 3 NOS points); high risk of bias (4 to 6 NOS points); and low risk of bias (≥ 7 NOS points). 21 Data of the meta‐analysis were evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) that ranked the evidence from very low to high. 22

RESULTS

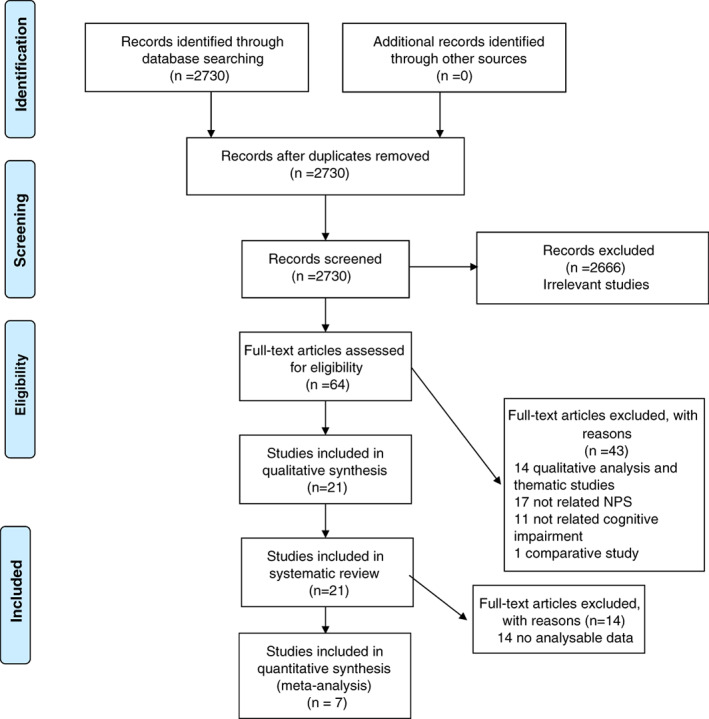

Four electronic databases, MEDLINE (n = 2090), Scopus (n = 777), EMBASE (n = 417), and Cochrane Central (n = 0) were searched, targeting reports published from database inception to 2 June 2021 with no language restrictions. The search identified 2730 non‐duplicated potentially eligible studies. The duplicates were removed both automatically and manually. Following a detailed review of title and abstracts, a total of 64 full text articles were reviewed. (Fig. 1) with 21 articles meeting the inclusion criteria (composite sample: N = 7139, range 18–4913, 4.0% MCI, mean age 75.6 ± 7.9 years, 60.0% female). The majority of the studies (n = 16) were conducted in the European continent, 13 , 14 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 and the remainder (n = 5) in the Americas. 5 , 12 , 36 , 37 , 38 Eight of these studies were cohort studies, and 13 were cross‐sectional studies (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Studies included in the analysis, investigating neuropsychiatric symptoms in people living with dementia or mild cognitive impairment during the COVID‐19 lockdown

| Author(s), Year | Country/Assessment/Confinement time | Mean Age/Female Gender (n) | Sample Size | Dementia Type /Features of patients with dementia | From first assessment to second assessment | Depression | Anxiety | Agitation | Apathy | Irritability | Aggression | Psychotic Symptoms | Sleep/night time behaviour disorder | Appetite/eating problems | Overall changes in NPI/NPS | RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CROSS‐SECTIONAL STUDIES | ||||||||||||||||

| Azevedo et al. 2021 5 |

Argentina Brazil Chile ‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

77.2 ± 9.3 / 183 | 321 |

‐Mild 50.1% ‐Moderate 23.1% ‐Severe 26.8% |

NA | NA | 37.4% | 23.1% | NA | 37.1% | 16.8% | 19.0% | 23.1% | 35.2% |

|

High |

| Baschi et al. 2020 30 |

Italy ‐patients or caregiver based telephone interview |

68.3 ± 11.5/ 35 | 62 |

MCI‐PD: 31 MCI‐no PD: 31 |

10 weeks |

|

|

‐ |

|

|

‐ |

|

|

|

|

Low |

| Borelli et al. 2021 36 |

Brazil‐caregiver‐based telephone interview |

76.5 (55–89)/ 34 | 58 |

AD: 29 Mixed Dementia: 7 VAD: 7 Others: 15 |

NA | 24.1% | 22.4% | 20.7% | 24.1% | 20.7% | NA | NA | NA | 19% |

|

High |

| Cagnin et al. 2020 31 |

Italy‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

78.3 ± 8.2/ 2934 | 4913 |

AD: 3372 DLB: 360 FTD: 415 VAD: 766 |

6.7 weeks |

25.1% 12,5† |

29.0% 13† |

30.7% 18,3† |

34.5% 17,1† |

40.2% 20,6† |

18.4% 13† |

9.9% 9,7† |

24.0% 21,3† |

11.0% 16† |

|

Low |

| Carlos et al. 2021 32 |

Italy ‐Telephone‐based survey |

83.0 (81.0–85.0) /10 | 18 | Dementia | 4 weeks | 61.5† | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Low |

| Cohen et al. 2020 12 |

Argentina ‐‐online questionnaire |

81.1 ± 7.03/ 77 | 119 |

AD: 80 Mixed dementia: 26 VAD: 7 Others: 2 |

8 weeks | 28.6% | 42% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 29.4% | NA |

|

High |

| Cohen et al. 2020 37 |

Argentina ‐online questionnaire |

80.51 ± 7.65/ 50 | 80 |

AD: 49 Mixed dementia: 16 VAD and others: 15 |

4 weeks | NA | 48% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

High |

| El Haj et al. 2021 13 |

France ‐follow up by phone or email. |

72.9 ± 7.1/ 43 | 72 | AD | NA |

|

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Low |

| El Haj et al. 2020 13 |

France ‐‐follow up by phone or email. |

71.79 ± 5.54/ 37 | 58 | AD | NA |

|

|

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Low |

| Giebel et al. 2020 14 |

United Kingdom ‐online or via phone assessment |

70 ± 10 / 27 | 61 |

AD: 20 Mixed dementia: 13 VAD: 11 Other’s: 17 |

NA | 48% | 33% | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Low |

| Pongan et al. 2020 34 |

France ‐online questionnaire |

76.9 ± 8.7/ 203 | 383 |

AD: 243 FTD: 27 DLB: 23 Others: 44 Unknown: 23 |

8 weeks | 23.3% | 44.7% | NA | 48.1% | NA | 42.6% | 18.3% | 21.7% | NA |

|

Low |

| Sorbara et al. 2020 38 |

Argentina ‐Consultations were held telephone e‐mail, video conference and at the emergency department |

56.19 ± 15.5/ 255 | 324 |

AD: 117 VAD: 32 FTD: 10 PD: 6 DLB: 3 MCI: 156 |

NA | 49.7% | 36.4% | 36.4% | 41.7% | 49.4% | 36.4% | 27.5% | 58.6 | 26.2% |

|

High |

| Thyrian et al. 2020 15 |

Germany ‐phone‐based questionnaire and semi‐structured interview assessment |

81.52 ± 6.38/ 87 | 141 | Mild dementia | NA |

|

|

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

High |

| COHORT STUDIES | ||||||||||||||||

| Alexopoulos et al. 2021 29 |

Greece ‐caregiver‐based telephone interview |

80 80.21 ± 7.70 / 47 | 67 |

AD: 45 VAD: 9 FTD: 2 Mixed dementia: 11 |

4.6 weeks |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

High |

| Barguilla et al. 2020 35 |

Spain ‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

75.4 ± 5.2/ 32 | 60 |

AD: 25 MCI: 15 FTD: 6 VAD: 3 DLB: 2 Others: 9 |

4 weeks |

|

|

|

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

|

High |

| Borges‐Machado et al. 2020 28 |

Portugal ‐caregiver‐based telephone interview |

74.28 + 6.76/ 24 | 36 |

AD: 17 Multiple Aetiologies: 6 Unspecified: 4 VAD: 2 FTD: 1 Korsakoff Syndrome: 1 MCI: 5 |

12 weeks | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

/ %44.4 |

High |

| Boutoleau‐Bretonniere et al. 2020 23 |

France ‐caregiver‐based telephone interview |

71.89 ± 8.24 / 39 | 76 |

AD: 38 FTD: 38 |

4 weeks | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

High |

| Carbone et al. 2021 24 |

Italy ‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

82.60 ± 8.91 / 22 | 35 |

AD: 6 VAD: 13 Others: 16 |

4 weeks | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

High |

| Lara et al. 2020 25 |

Spain ‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

77.4 ± 5.25/ 24 | 40 |

MCI: 20 AD: 20 |

5 weeks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

| Manini et al. 2021 26 |

Italy ‐ caregiver‐based telephone interview |

83.2 ± 5.5 / 67 | 94 |

AD: 78 Mixed dementia: 7 VAD: 3 DLB: 3 FTD:2 Corticobasal degeneration: 1 |

NA |

8.5% 1.1%† |

5.3% 9.6%† |

17.0% 4.3%† |

8.5% 1.1%† |

9.6% 2.1%† |

17.0% 4.3%† |

3.2% 3.2%† |

2.1% 4.3%† |

1.1% 2.1%† |

|

High |

| van Maurik et al. 2020 27 | Netherlands‐a self‐reported corona survey | 69 ± 6/ 40 | 121 |

AD: 43 DLB: 34 MCI: 35 Others: 9 |

NA | 20–40% | 20–40% | 30% | 40% | NA | NA | NA | 37.0% | NA |

|

High |

| 21 studies |

16 European countries 5 American countries |

75.6 ± 7.9/ 4270 | 7139 |

AD: 4312 VAD: 868 DLB: 425 FTD: 501 MCI: 293 Mixed dementia: 80 Others: 660 Cohort: 8 Cross‐sectional: 13 |

12 studies: 6.2 week, 9 studies: NA data |

Not increased changes in NPS/NPI scores: 5 Increased in NPI/NPS: 16 |

7 studies: Low RoB 14 studies: High RoB |

|||||||||

Note: Statistically significant increases in neuropsychiatric symptoms are indicated with an upward‐pointing arrow ( ); horizontal arrows (

); horizontal arrows ( ) mark insignificant changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms.

) mark insignificant changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms.

AAD, Alzheimer Disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPS, neuropsychiatric symptoms; NA, not applicable; PD, Parkinson's disease dementia; RoB, risk of bias; VAD, vascular dementia.

New onset neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Three studies did not specify the type of dementia. 5 , 15 , 32 According to data of the remaining studies, the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD), vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal dementia, and mixed type dementia were 64.7%, 12.9%, 6.4%, 7.5%, and 1.2%, respectively. NPS were most commonly evaluated by NPI (11 of the 22 included studies). 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 36 , 38 Four studies used validated scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, 13 , 14 , 15 , 32 and other studies used non‐validated questionnaires. Almost all of the evaluations were made with a caregiver‐based telephone interview or online questionnaire (Table 1).

Systematic review

Cross‐sectional studies

In cross‐sectional studies, caregivers were asked about NPS changes in patients, comparing to the period before the pandemic, and evaluated accordingly. Out of 13 studies, only 1 evaluating depressive symptoms before and after the outbreak of the COVID‐19 crisis found no change. 15 Based on the results of 12 other studies, the most common aggravated reported NPS were depression, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and apathy during lockdown. 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 The rate of incidence was not specified in three studies, only pre‐ and post‐COVID‐19 crisis outbreak values were compared. 13 , 30 , 33 The two studies including different populations and conducted by El Haj et al. determined that higher levels of depression and anxiety were recorded during compared to before the pandemic. 13 , 33 Baschi et al. demonstrated that depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, and changes in sleep behaviours revealed the most significant difference before and after lockdown. 30 Anxiety was one of the most frequent aggravated NPS in eight studies, and rate of increase in the prevalence of anxiety varied 22.4%–48%. 5 , 12 , 14 , 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 38 Seven studies showed that incidence of depression was very common during lockdown (23.3%–61.5%). 12 , 14 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 36 , 38 Four studies showed an increase in agitation and aggression (20.7%–36.4%) and showed an increase in irritability (20.7%–49.4%), 5 , 31 , 36 , 38 while four studies similarly revealed that apathy increased (24.1%–48.1%) compared to pre‐lockdown. 31 , 34 , 36 , 38 Unlike the aforementioned studies, Cagnin et al. examined the frequency of new onset NPS with aggravated NPS and showed that aggravated and new‐onset NPS were similar, but sleep disorder was one of the most commonly observed new onset NPS. 31 Most of the studies (46.1%) had a high level of bias. The reasons for this might be due to the absence of those without cognitive impairment (i.e. control group), the fact that NPS were evaluated with a caregiver‐based telephone interview instead of a validated scale, and the effect of residual confounding (Table S1 in the Supporting Information).

Cohort studies

In two of the eight cohort studies, the follow‐up period was not reported, while the follow‐up period in the others ranged from 4 to 12 weeks. In contrast to cross‐sectional studies, NPI was used in cohort studies rather than individual evaluations of NPS. In two of eight studies, there was no change in NPI scores compared to pre‐lockdown. 23 , 24 , 26 , 29 However, Manini et al. showed that agitation, aggression, depression, apathy, and irritability were among the most increased NPS. 26 In two of the four studies showing an increase in NPI scores, a statistical change for each of the NPS was shown without specifying the rate of increase, and how much proportional change there was in one study. 25 , 35 While agitation was the common NPS found to be increased in three studies, depression, apathy, and anxiety were the NPS found to be increased in two studies. Manini et al. evaluated new onset NPS and worsening of pre‐existing NPS separately, and in this study, sleep disorders were determined to be one of the most incipient NPS. 26 However, there is a high risk of bias in all cohort studies (Table 1). The reasons for this are the absence of a control group in the study that were not exposed to the pandemic, the short follow‐up time, and the initial NPI values being usually based on retrospective medical records (Table S1).

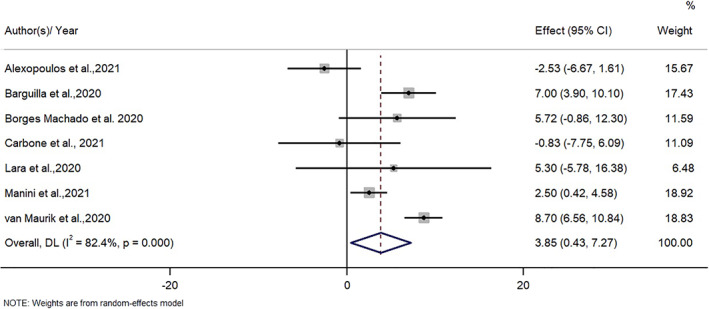

Meta‐analysis

Seven studies including 420 participants (22.1% MCI) yielded enough data to be included in the meta‐analysis, 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 35 that is, of studies reporting NPI values before and during the COVID‐19 lockdown. The mean follow‐up time was 5.9 ± 1.5 weeks. The pooled increase in NPI score before compared to during COVID‐19 was 3.85 (95% CI 0.43 to 7.27; P = 0.03; I 2 = 82.4%) (Fig. 2 ). This evidence was supported by a very low certainty of evidence according to the GRADE since all included studies had a high risk of bias, with small sample sizes included, and a high heterogeneity present. In the sensitivity analysis, the significance and magnitude of the results did not change with the removal of any one study. The removal of van Maurik et al. (2020) reduced the heterogeneity to 70%. The visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated no publication bias and the Egger's test P‐value was 0.54, suggesting no presence of publication bias (Fig. S1 ).

Figure 2.

The effect of the COVID‐19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment.

In the meta regression analyses, bivariate analyses did not moderate the associations between mean age, gender distribution (percentage female), follow‐up duration, or percentage of people with mild dementia, percentage of people with MCI, and changes in NPS scores (mean age coefficient = −0.58, 95% CI: −1.17 to 0.01, P = 0.05, r 2 = 0.62; gender distribution coefficient = −0.09, 95% CI: −0.43 to 0.24, P = 0.50, r 2 = 0.00; follow‐up duration: coefficient = 0.43, 95% CI: −2.13 to 2.99, P = 0.63, r 2 = 0.00; percentage of people with mild dementia: coefficient = −0.05, 95% CI: −0.30 to 0.22, P = 0.69, r 2 = 0.00; percentage of people with MCI: coefficient = 0.04, 95% CI: −0.26 to 0.34, P = 0.75, r 2 = 0.00).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta‐analysis of 21 studies including more than 7000 people living with dementia or MCI, NPS tended to increase during the pandemic, with aggravated NPS being most commonly depression, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and apathy. Moreover, according to the meta‐analysis results of seven studies with NPI scores before and after lockdown, a significant worsening in NPI was found. While the studies had high heterogeneity and high risk of bias, indicating low quality as data, the overall direction of the results was clear.

NPS, very common in patients with dementia, affects more than 97% of patients during the course of their disease. 39 It may cause cognitive and functional deterioration, long‐term hospitalization, mortality, and decreased quality of life for caregivers and patients. 7 Given these outcomes, it is clear that NPS can negatively affect both people living with dementia and their caregivers. However, while coping with NPS is difficult for both healthcare professionals and families, the COVID‐19 pandemic is making this more complex. In this systematic review, an increase in NPS was determined in most of the 21 studies. Although a 3‐point change from baseline in NPI scores is considered a clinically meaningful difference, no clinical score is available in the changes of NPI between two evaluations. Therefore, we could only analyse changes in NPI scores and a statistically significant worsening in NPI was found in this meta‐analysis over a mean of ~5 weeks. Possible reasons for this may be as follows. First, the inability to maintain physical activity and social interactions, which are non‐pharmacological approaches recommended for NPS prevention, due to forced lockdown at home, and the closure of outpatient rehabilitation centres that provide services such as cognitive training, occupational therapy, and group activities, may have increased the risk for development of NPS. 37 Loneliness, social isolation, and loss of routine activities are an important cause of increased depression and anxiety. 33 , 40 For example, according to one study, during the covid‐19 pandemic, two out of three older adults experienced a moderate sense of loneliness, and individuals who displayed a higher level of loneliness also had a higher severity of anxiety level depressive symptoms and irritability. 41 However, the lockdown exaggerated feelings of hopelessness, sadness, and loneliness, not only among older people, but also in the general population, leading to widespread depression and anxiety. A study comparing older people with and without dementia showed that people living with dementia mostly suffered from depressive symptoms, while cognitively normal older adults experienced more anxiety. 32 Dementia patients may show more depressive symptoms due to their inability to adapt to performing activities such as physical activity or leisure time activities. On the other hand, those who are cognitively normal may experience more anxiety because they are aware of adverse COVID‐related situations, such as health problems. Although the covid‐19 lockdown has increased NPS in the entire general population, it should be considered as a separate entity as the course of NPS in dementia patients may be different.

Second, caregiver distress itself may have increased NPS in people living with dementia, or may have affected the reporting of features of NPS by the caregiver, which was the method of data collection in the majority of studies. 9 Caregivers may have been concerned about losing paid caregivers, 37 the ability of the patient with dementia to comply with infection control precautions, 42 and less contact with their wider family to reduce the risk of virus transmission, as well as the challenges of using virtual telecommunications technology. 37 , 42 Previous studies have shown that distressed caregivers tend to use emotion‐focused rather than problem‐focused coping strategies, which appear to increase the patient’s NPS. 9 A prolonged proximity between the caregiver and his/her relative can promote tensions and mirror reactions. 34 Irritation, anger, or impatience on the part of the caregiver may cause more aggression/irritability in people living with dementia. 9 , 34 Third, the rapid cognitive deterioration in people living with dementia during the pandemic, the inability of these patients to adapt to new living conditions, and the inability of patients to continue their usual daily activities, may have led to the development of apathy and triggered depression. 4 , 32 Finally, distress factors such as loneliness and anxiety, as well as the NPS itself, such as aggravating depression and anxiety, may also result in sleep disorders due to the covid‐19 lockdown in patients. 43

It was observed that the worsening in NPS (especially anxiety) during quarantine was much greater in patients with mild dementia than in those with advanced dementia. 44 One possible explanation for this may be that subjects with relatively mild dementia may have undergone more radical changes in their lifestyle habits during quarantine than those with severe dementia, who are generally more home‐bound and less active. 12 It is possible that people with mild dementia during quarantine have a greater awareness of the pandemic and the risks of getting sick, and that this information is likely to cause more concern. 12 , 32 Indeed, it is considered that awareness of the COVID‐19 outbreak and “patients understanding the reason for wearing a mask” was more than three times greater in mild AD than in moderate–severe AD, and that due to this lessened awareness, the depressive symptoms associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic were less common in moderate and severe dementia. 44 However, comparing neuropsychiatric symptoms one by one according to the severity of dementia, Azevedo et al. determined that anxiety, psychotic symptoms, and appetite changes were more common in moderate dementia than in mild and severe dementia. 5 It is important to note that the interviews may have been influenced by the emotional state of each caregiver on the day of the survey.

According to the meta‐analysis, seven studies found that NPI scores increased in the COVID‐19 lockdown. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 35 However, in contrast to the meta‐analytic results, interestingly enough there were some studies reporting no change in NPS in the literature. One possible reason for this could be the effect of a short lockdown duration for re‐evaluating the NPI. For example, in a study in which the mean lockdown duration was 27.4 days, it was shown that a very small percentage of AD patients had a change in NPS, but there was a positive correlation between lockdown duration and both NPS severity and caregiver distress. 23 Re‐evaluation after 5 weeks (35 days) of lockdown in one of the seven studies and a mean of 32 days in the other (not clear in the others) suggests that the change in NPS may occur over a longer period of time. 25 , 29 Furthermore, although caregiving is a stressful situation that imposes physical, mental, and social constraints, it may be that the lockdown to stem the COVID‐19 pandemic had little or no additional impact on the caregivers' routines. For example, the fact that some societies, such as Italy, have supported and trained their caregivers by a formal health care network, at least until the onset of the pandemic, suggests that these caregivers have less difficulty coping with the day‐to‐day care of people with dementia, and that the way they perceive NPS has already changed, or that they do not report their own reluctance to manage NPS. 24 , 45 The lack of significant changes in NPI in two studies conducted in Italy also supports this. 24 , 26 Finally, depending on the proportion of moderate and severe dementia in the studies, it may be that risk to health of the COVID‐19 pandemic is not perceived by patients and the NPS do not change accordingly. 44 However, our meta‐analysis results did not change after adjusting for severity of dementia.

Our study has some limitations. First, most of the studies included in the review (especially the meta‐analysis) have small sample sizes and are of a cross‐sectional design; thus, there is no clear information about pre‐pandemic evaluation. Second, lockdown duration was short, and many studies do not report time from first to second assessment. Third, although NPS is seen with different severity and frequency in different dementia subtypes, analysis by dementia subtypes was not performed, except in one study. 31 Fourth, it has not been clearly determined how each of the NPS, such as depression, anxiety, and apathy, is affected separately. Fifth, no separate evaluation was made for MCI patients, as pre‐ and post‐lockdown NPI scores were given only for the total sample size in the studies. Last, the studies were clinically and statistically heterogeneous; this may be partly due to different time periods between assessments, differences in not only dementia type or severity, but also evaluation of NPS. Additionally, the variation in impact of COVID and restrictions may be different in different countries, which might be the cause of high heterogeneity and high risk of bias. The strength of our study is that it is the first compilation of results of studies conducted under difficult pandemic conditions.

In conclusion, there is an increase in the worsening of NPS, frequency of depression, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and apathy in people living with cognitive impairment during lockdown in the COVID pandemic. There is a clear need to explore the causes of NPS and how people living with dementia and their caregivers can be supported in any future pandemic and lockdown or where usual support services are not available and face‐to‐face contact is limited. Therefore, it is of substantial importance to develop appropriate strategies for preventing and coping with NPS in people living dementia. A few examples of these strategies can be listed as follows: Developing and disseminating telehealth applications in order to maintain coordination with doctors and other health professionals during the closure, educating caregivers on how to manage NPS, with or without a pandemic, arranging the necessary technological infrastructure for the continuation of socialization during the lockdown.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: PS, NV. Practical performance: PS, LS, SGT, MT. Data analysis: NV, MT. Manuscript—preparation: PS, SS, NV. Manuscript—critical review: SS, AK, PA, MB. All authors contributed to the draft and revision of the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Funnel plot showing the standard error by NPS differences in means

Table S1 The quality assessment of the included studies

Disclosure: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Douglas M, Katikireddi SV, Taulbut M, McKee M, McCartney G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid‐19 pandemic response. BMJ 2020; 369: m1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saragih ID, Saragih IS, Batubara SO, Lin CJ. Dementia as a mortality predictor among older adults with COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational study. Geriatr Nurs 2021; 42: 1230–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lozano‐Montoya I, Quezada‐Feijoo M, Jaramillo‐Hidalgo J, Garmendia‐Prieto B, Lisette‐Carrillo P, Gómez‐Pavón FJ. Mortality risk factors in a Spanish cohort of oldest‐old patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in an acute geriatric unit: the OCTA‐COVID study. Eur Geriatr Med 2021; 12: 1169–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ismail II, Kamel WA, Al‐Hashel JY. Association of COVID‐19 pandemic and rate of cognitive decline in patients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a cross‐sectional study. Gerontol Geriatr Med 2021; 7: 23337214211005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Azevedo LVDS, Calandri IL, Slachevsky A et al. Impact of social isolation on people with dementia and their family caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis 2021; 81: 607–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Demurtas J, Schoene D, Torbahn G et al. Physical activity and exercise in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: an umbrella review of intervention and observational studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21: 1415–1422.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Veronese N, Solmi M, Basso C, Smith L, Soysal P. Role of physical activity in ameliorating neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease: a narrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019; 34: 1316–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soysal P, Aydin AE, Isik AT. Challenges experienced by elderly people in nursing homes due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Psychogeriatrics 2020; 20: 914–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Isik AT, Soysal P, Solmi M, Veronese N. Bidirectional relationship between caregiver burden and neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a narrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2019; 34: 1326–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Padala KP, Parkes CM, Padala PR. Neuropsychological and functional impact of COVID‐19 on mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2020; 35: 1533317520960875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsapanou A, Papatriantafyllou JD, Yiannopoulou K et al. The impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on people with mild cognitive impairment/dementia and on their caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021; 36: 583–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cohen G, Russo MJ, Campos JA, Allegri RF. COVID‐19 epidemic in Argentina: worsening of behavioral symptoms in elderly subjects with dementia living in the community. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El Haj M, Altintas E, Chapelet G, Kapogiannis D, Gallouj K. High depression and anxiety in people with Alzheimer's disease living in retirement homes during the covid‐19 crisis. Psychiatry Res 2020; 291: 113294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giebel C, Lord K, Cooper C et al. A UK survey of COVID‐19 related social support closures and their effects on older people, people with dementia, and carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021; 36: 393–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thyrian JR, Kracht F, Nikelski A et al. The situation of elderly with cognitive impairment living at home during lockdown in the Corona‐pandemic in Germany. BMC Geriatr 2020; 20: 540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ [Internet] 2020; 2021: 372, n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wells GA, Shea B, O'connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute 2014. [Cited 13 Aug 2014]. Available from URL http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 21. Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008; 336: 924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boutoleau‐Bretonnière C, Pouclet‐Courtemanche H, Gillet A et al. The effects of confinement on neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease during the COVID‐19 crisis. J Alzheimers Dis 2020; 76: 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carbone E, Palumbo R, Di Domenico A, Vettor S, Pavan G, Borella E. Caring for people with dementia under COVID‐19 restrictions: a pilot study on family caregivers. Front Aging Neurosci 2021; 13: 652833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lara B, Carnes A, Dakterzada F, Benitez I, Piñol‐Ripoll G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and quality of life in Spanish patients with Alzheimer's disease during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Eur J Neurol 2020; 27: 1744–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manini A, Brambilla M, Maggiore L, Pomati S, Pantoni L. The impact of lockdown during SARS‐CoV‐2 outbreak on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Neurol Sci 2021; 42: 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Maurik IS, Bakker ED, van den Buuse S et al. Psychosocial effects of corona measures on patients with dementia, mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 585686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borges‐Machado F, Barros D, Ribeiro Ó, Carvalho J. The effects of COVID‐19 home confinement in dementia care: physical and cognitive decline, severe neuropsychiatric symptoms and increased caregiving burden. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2020; 35: 1533317520976720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alexopoulos P, Soldatos R, Kontogianni E et al. COVID‐19 crisis effects on caregiver distress in neurocognitive disorder. J Alzheimers Dis 2021; 79: 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baschi R, Luca A, Nicoletti A et al. Changes in motor, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson's disease and mild cognitive impairment during the COVID‐19 lockdown. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 590134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cagnin A, Di Lorenzo R, Marra C et al. Behavioral and psychological effects of coronavirus Disease‐19 quarantine in patients with dementia. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 578015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Carlos AF, Poloni TE, Caridi M et al. Life during COVID‐19 lockdown in Italy: the influence of cognitive state on psychosocial, behavioral and lifestyle profiles of older adults. Aging Ment Health 2021; 1–10. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1870210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. El Haj M, Moustafa AA, Gallouj K. Higher depression of patients with Alzheimer's disease during than before the lockdown. J Alzheimers Dis 2021; 81: 1375–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pongan E, Dorey JM, Borg C et al. COVID‐19: association between increase of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia during lockdown and Caregivers' poor mental health. J Alzheimers Dis 2021; 80: 1713–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barguilla A, Fernández‐Lebrero A, Estragués‐Gázquez I et al. Effects of COVID‐19 pandemic confinement in patients with cognitive impairment. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 589901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Borelli WV, Augustin MC, de Oliveira PBF et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia associated with increased psychological distress in caregivers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Alzheimers Dis 2021; 80: 1705–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cohen G, Russo MJ, Campos JA, Allegri RF. Living with dementia: increased level of caregiver stress in times of COVID‐19. Int Psychogeriatr 2020; 32: 1377–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sorbara M, Graviotto HG, Lage‐Ruiz GM et al. COVID‐19 and the forgotten pandemic: follow‐up of neurocognitive disorders during lockdown in Argentina. Neurologia 2021; 36: 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P et al. Point and 5‐year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008; 23: 170–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hwang TJ, Rabheru K, Peisah C, Reichman W, Ikeda M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Psychogeriatr 2020; 32: 1217–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dziedzic B, Idzik A, Kobos E et al. Loneliness and mental health among the elderly in Poland during the COVID‐19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang H, Li T, Barbarino P et al. Dementia care during COVID‐19. Lancet 2020; 395: 1190–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cipriani GE, Bartoli M, Amanzio M. Are sleep problems related to psychological distress in healthy aging during the COVID‐19 pandemic? A review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 10676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tsugawa A, Sakurai S, Inagawa Y et al. Awareness of the COVID‐19 outbreak and resultant depressive tendencies in patients with severe Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2020; 77: 539–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015; 30: 130–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Funnel plot showing the standard error by NPS differences in means

Table S1 The quality assessment of the included studies