Key Points

Question

Is transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) noninferior to surgical aortic valve replacement (surgery) in patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 913 patients at moderately increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity, all-cause mortality at 1 year was 4.6% with TAVI vs 6.6% with surgery, a difference that met the prespecified noninferiority margin of 5%.

Meaning

Among patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk, treatment with TAVI was noninferior to surgery with respect to all-cause mortality at 1 year.

Abstract

Importance

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement and is the treatment of choice for patients at high operative risk. The role of TAVI in patients at lower risk is unclear.

Objective

To determine whether TAVI is noninferior to surgery in patients at moderately increased operative risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this randomized clinical trial conducted at 34 UK centers, 913 patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity were enrolled between April 2014 and April 2018 and followed up through April 2019.

Interventions

TAVI using any valve with a CE mark (indicating conformity of the valve with all legal and safety requirements for sale throughout the European Economic Area) and any access route (n = 458) or surgical aortic valve replacement (surgery; n = 455).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 1 year. The primary hypothesis was that TAVI was noninferior to surgery, with a noninferiority margin of 5% for the upper limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI for the absolute between-group difference in mortality. There were 36 secondary outcomes (30 reported herein), including duration of hospital stay, major bleeding events, vascular complications, conduction disturbance requiring pacemaker implantation, and aortic regurgitation.

Results

Among 913 patients randomized (median age, 81 years [IQR, 78 to 84 years]; 424 [46%] were female; median Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality risk score, 2.6% [IQR, 2.0% to 3.4%]), 912 (99.9%) completed follow-up and were included in the noninferiority analysis. At 1 year, there were 21 deaths (4.6%) in the TAVI group and 30 deaths (6.6%) in the surgery group, with an adjusted absolute risk difference of −2.0% (1-sided 97.5% CI, −∞ to 1.2%; P < .001 for noninferiority). Of 30 prespecified secondary outcomes reported herein, 24 showed no significant difference at 1 year. TAVI was associated with significantly shorter postprocedural hospitalization (median of 3 days [IQR, 2 to 5 days] vs 8 days [IQR, 6 to 13 days] in the surgery group). At 1 year, there were significantly fewer major bleeding events after TAVI compared with surgery (7.2% vs 20.2%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.33 [95% CI, 0.24 to 0.45]) but significantly more vascular complications (10.3% vs 2.4%; adjusted HR, 4.42 [95% CI, 2.54 to 7.71]), conduction disturbances requiring pacemaker implantation (14.2% vs 7.3%; adjusted HR, 2.05 [95% CI, 1.43 to 2.94]), and mild (38.3% vs 11.7%) or moderate (2.3% vs 0.6%) aortic regurgitation (adjusted odds ratio for mild, moderate, or severe [no instance of severe reported] aortic regurgitation combined vs none, 4.89 [95% CI, 3.08 to 7.75]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk, TAVI was noninferior to surgery with respect to all-cause mortality at 1 year.

Trial Registration

isrctn.com Identifier: ISRCTN57819173

This randomized clinical trial assesses whether transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is noninferior to surgical aortic valve replacement in patients at moderately increased operative risk.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis requiring intervention. The first clinical use of TAVI was in 20021 and evidence from randomized clinical trials has supported its adoption as the treatment of choice for patients who are unfit for conventional surgery2 or who are at high operative risk.3,4,5,6 Early trials used first-generation TAVI devices, which were associated with a high rate of procedural complications.7,8 Technological developments, procedural refinements, and increased operator experience have subsequently resulted in improved outcomes, and there is increasing interest in the use of TAVI in patients at lower operative risk. The UK Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (UK TAVI) trial was conducted to compare TAVI with surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk due to age or comorbidity.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

This was an investigator-initiated, pragmatic, multicenter, randomized clinical trial involving all National Health Service hospitals performing TAVI in the UK. Details of the participating sites and investigators appear in the eAppendix in Supplement 1. The trial was designed by the investigators and overseen by an independent trial steering committee and an independent data monitoring committee (eMethods 1 in Supplement 2). The TAVI valves and the surgical valves were procured through standard National Health Service commissioning. The trial protocol was approved by the London Stanmore research ethics committee. All participants gave written informed consent. The trial protocol appears in Supplement 3 and the statistical analysis plan appears in Supplement 4. One-year outcomes are presented herein. Follow-up to a minimum of 5 years is ongoing.

Participants

Eligible patients were aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and increased operative risk due to comorbidity or age. Age alone was a sufficient criterion for inclusion of patients aged 80 years or older. Eligibility was determined by a multidisciplinary team at each site based on clinical equipoise regarding the choice of intervention. Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted mortality9,10 and European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II11,12 risk scores were calculated but used in a discretionary manner, with no prespecified thresholds for inclusion. Patients requiring coronary revascularization were included unless only surgical revascularization was considered appropriate. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in eMethods 2 in Supplement 2, with further details of the patient identification process in eMethods 3 in Supplement 2.

Ethnicity data were recorded to assess the diversity of the study population, which may have implications for the external validity of the trial. Ethnicity was determined by the staff at each site based on discussion with the participant or review of hospital records using a list of prespecified options that corresponded to those used by the UK Office for National Statistics.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive TAVI or surgical aortic valve replacement (surgery). Randomization was performed using an electronic web-based system developed and hosted by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials at the University of Aberdeen. The randomization used minimization, including an 80% probabilistic element with stratification for the randomization site, age group (70-79 years vs ≥80 years), and the presence of coronary artery disease considered by the multidisciplinary team to require revascularization if the patient was randomized to receive surgery. Participants and site staff were unblinded to the treatment assigned.

Interventions

Participants randomized to TAVI were treated using any valve with a CE mark (indicating conformity of the valve with all legal and safety requirements for sale throughout the European Economic Area). All aspects of the TAVI procedure, including the choice of local or general anesthesia, access route, and prior or concurrent revascularization were determined by the local clinical team. For participants randomized to surgical aortic valve replacement (surgery), the use of any commercially available valve was permitted apart from sutureless valves. All aspects of the surgical procedure and perioperative care were determined by the local clinical team. The use and choice of anticoagulant and antithrombotic therapy were at the discretion of the responsible physician.

Participants underwent clinical assessment at baseline, 6 weeks after undergoing the intervention, and 1 year after randomization. Interim telephone follow-up was performed 3 months after undergoing the intervention and 6 months after randomization. Frailty at baseline was assessed using the Fried criteria13 and the Canadian Study of Health and Aging Clinical Frailty Scale.14

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 1 year (death from any cause within 1 year from randomization). Secondary outcomes included cardiovascular death; stroke; reintervention; a composite of death or stroke; a composite of death or disabling stroke; a composite of death, disabling stroke, or reintervention; vascular complications; major bleeding events; conduction disturbances requiring permanent pacing; myocardial infarction; kidney replacement therapy; and infective endocarditis.

A list of all prespecified outcomes (eMethods 4) and the outcome definitions (eMethods 5) based on criteria from the Valve Academic Research Consortium-215 consensus document appear in Supplement 2. Only 30-day and 1-year outcomes are reported herein; longer-term follow-up is ongoing. Six of the 36 secondary outcomes are not included in this report (identified in eMethods 4 in Supplement 2). Disability after stroke was assessed using the modified Rankin Scale at 90 days.16 Outcome events were adjudicated by an end points and events committee, which was aware of the assigned treatment. The data presented are based on adjudicated outcomes.

Symptoms and functional capacity were assessed using the Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina grading system,17 the New York Heart Association classification system,18 the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale,19 and the 6-minute walk test.20 Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination.21 Quality of life was assessed using the 5-level EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L)22 instrument and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire.23 Details of these instruments, including their ranges, directionality, and minimal clinically important differences appear in eMethods 5 in Supplement 2. Participants underwent echocardiography at baseline, 6 weeks, and 1 year. Images were analyzed by an independent core laboratory. Assessors were not informed of the scan time point or the treatment allocation, but the presence of a prosthetic valve usually will have been evident and the type of valve often will have been identifiable, so blinding was incomplete.

Sample Size

The initial sample size was 808 patients based on an assumed 1-year mortality of 15% after surgery (based on age-specific data for 2004-2008 from the UK National Adult Cardiac Surgery database24), with an absolute difference noninferiority margin of 7.5% for the evaluation of whether TAVI is noninferior to surgery. However, a prespecified interim analysis of pooled data showed lower 1-year mortality than expected and the sample size was increased based on the recommendation of the trial steering committee.

The revised sample size was based on an assumed 1-year mortality of 7.5% after surgery and a noninferiority margin of 5%. It was estimated that at least 890 participants would provide 80% power to show that the upper limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI for the treatment difference would not be above the noninferiority margin, allowing for a 2% dropout rate.

The chosen noninferiority margin was based on the principle of balancing clinical preference for the lowest possible margin with the feasibility of recruitment in an acceptable time frame. Five percent was considered to be an acceptable margin in the collective opinion of the trial steering committee, which included clinical and lay members, noting that the margin relates to the upper limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI for the difference in mortality that would be accepted for TAVI to be considered noninferior to surgery.

Statistical Analysis

For the primary statistical analysis, participants were included in the groups as randomly assigned. The analysis data set included all randomized participants; however, those with unknown vital status at 1 year due to withdrawal from the trial were excluded. For the primary outcome, the absolute risk difference was derived from a logistic regression model using delta method–estimated SEs.25 The logistic regression model was adjusted for randomization minimization factors and used robust SEs to account for the clustering of outcomes by randomization site. Noninferiority was met if the upper limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI was less than 5% for the adjusted absolute difference in mortality between TAVI and surgery.

The robustness of the conclusions was assessed by a per-protocol analysis, which included the subset of participants who were treated as randomly assigned (ie, went to the catheter laboratory or operating theater for their randomly assigned intervention within 1 year of randomization even if the procedure was subsequently abandoned or converted to an alternative intervention). A sensitivity analysis also was performed in which participants with unknown vital status at 1 year were assumed to have died if randomized to TAVI and to have survived if randomized to surgery.

Event-related outcomes at 30 days after the procedure and at 1 year after randomization were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for randomization minimization factors and using robust SEs to account for the clustering of outcomes by randomization site. If applicable, participants were censored at their date of withdrawal or death. Log-log survival plots and Schoenfeld residuals were used to check the assumption of proportionality. Kaplan-Meier plots were constructed for time-to-event analyses.

Risk differences with 95% CIs also were calculated. The descriptive statistics are based on all available data. Exploratory subgroup analyses for the primary outcome were performed using logistic regression models and included covariates for the treatment, the relevant subgroup, and an interaction term for both. Unless otherwise specified, statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp).

For the statistical analysis of the secondary outcomes that were not event-related outcomes, continuous outcome variables were summarized as mean (SD) or median (IQR). Treatment effects were estimated using a multilevel mixed-effects model, including repeated measures of the secondary outcome variables at the relevant time points after randomization, nested within participants. The model was adjusted for the randomization factors in line with the primary analysis model, as well as for baseline values of the outcomes if appropriate. Time was added to the model as a categorical variable and treatment × time interactions were included. Robust SEs were used to account for clustering of the outcomes by randomization site. Categorical outcomes were analyzed similarly using multilevel, mixed-effects logistic regression models. The analyses used the available cases subset and the participants were included in the groups as randomly assigned, regardless of the treatment they received.

A post hoc sensitivity analysis also was performed using a fully adjusted Bayesian hierarchical joint model, which simultaneously adjusted for intermittent missing data and dropout due to death as well as randomization minimization factors. Additional details appear in eMethods 6 in Supplement 2.

The secondary outcomes were tested at a 2-sided significance level of .05. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory.

Results

Participants

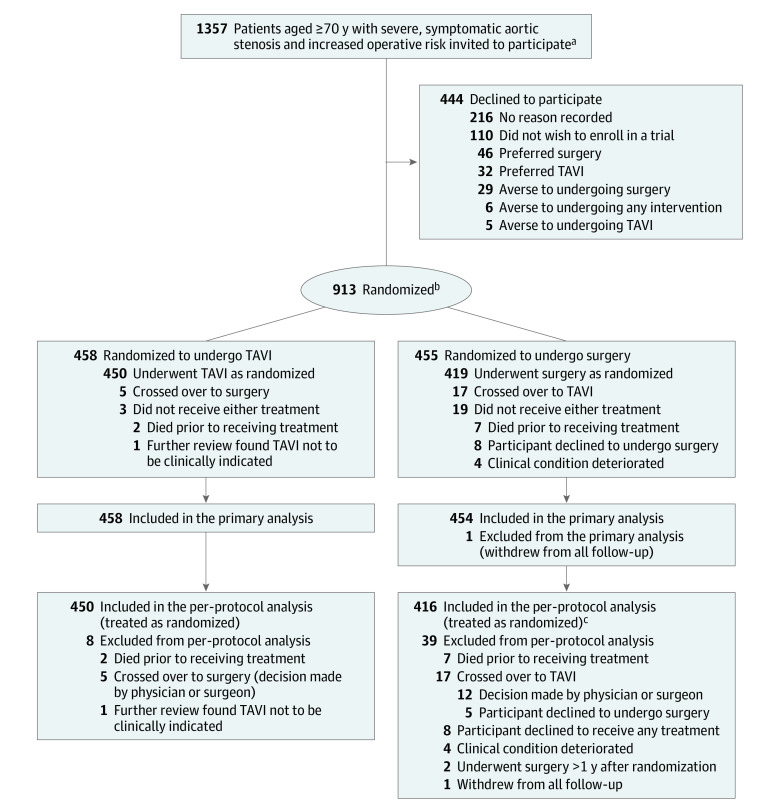

Between April 9, 2014, and April 30, 2018, 913 participants were randomly assigned to undergo either TAVI (n = 458) or surgery (n = 455) (Figure 1). In the TAVI group, 450 participants underwent TAVI, 5 crossed over to surgery, and 3 did not receive treatment. In the surgery group, 419 participants underwent surgery, 17 participants crossed over to TAVI, and 19 participants did not receive treatment.

Figure 1. Patient Selection, Allocation, and Flow in the UK Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (UK TAVI) Trial for Aortic Stenosis.

aPatients were invited to participate after multidisciplinary team review and confirmation of eligibility. Participating sites maintained monthly screening logs of patients recommended for consideration for enrollment; however, some logs were missing, with an estimated overall shortfall of 22% (based on the number of patients randomized but not included in the screening logs). This would imply that the actual number of patients reviewed by the multidisciplinary team and invited to participate was in the region of 1740 rather than the stated figure of 1357, which was derived directly from the screening logs. Data regarding overall national TAVI and surgery activity during the relevant period are available from the relevant national audits.26,27,28

bRandomization used minimization, including an 80% probabilistic element with stratification for the randomization site, age group (70-79 years vs ≥80 years), and the presence of coronary artery disease considered by the multidisciplinary team to require revascularization if the patient was randomized to receive surgery.

cThree additional participants were treated as randomized but excluded from the per-protocol analysis (2 were treated >1 year after randomization and 1 withdrew from all follow-up).

Baseline characteristics were well balanced between the groups (Table 1 and eTable 1 in Supplement 2). The median age was 81 years (IQR, 78-84 years) and 46.4% of the participants were women. The median Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality risk score was 2.6% (IQR, 2.0%-3.4%). Coronary artery disease that was considered by the multidisciplinary team to require revascularization if the patient was assigned to receive surgery was present in 19.8% of the participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Participants at Baselinea.

| Characteristic | TAVI (n = 458) | Surgery (n = 455) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 81 (79-84) | 81 (78-84) |

| Age group, No. (%) | ||

| 70-79 | 143 (31.2) | 143 (31.4) |

| ≥80 | 315 (68.8) | 312 (68.6) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 247 (53.9) | 242 (53.2) |

| Female | 211 (46.1) | 213 (46.8) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%)b | ||

| Asian or Asian British | 5 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) |

| Black, African, Caribbean, or Black British | 0 | 6 (1.3) |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| White | 447 (97.6) | 434 (95.4) |

| Other | 5 (1.1)c | 8 (1.8)d |

| Body mass index, median (IQR)e | (n = 458); 27.1 (24.0-30.5) | (n = 452); 27.7 (24.7-31.2) |

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality risk score, median (IQR), %f | (n = 458) | (n = 454) |

| Overall | 2.6 (2.0-3.5) | 2.7 (2.0-3.4) |

| By age group, y | ||

| 70-79 | 2.1 (1.6-2.8) | 2.0 (1.6-2.8) |

| ≥80 | 2.9 (2.2-3.7) | 2.9 (2.3-3.8) |

| EuroSCORE II risk score, median (IQR), %g | (n = 458) | (n = 454) |

| Overall | 2.0 (1.4-3.0) | 2.0 (1.5-3.3) |

| By age group, y | ||

| 70-79 | 1.7 (1.3-2.6) | 1.8 (1.3-2.8) |

| ≥80 | 2.2 (1.5-3.2) | 2.3 (1.6-3.4) |

| New York Heart Association class III or IV, No./total (%)h | 184/457 (40.3) | 204/451 (45.2) |

| Frailty, No./total (%) | ||

| CSHA Clinical Frailty Scale score ≥5i | 58/454 (12.8) | 60/449 (13.4) |

| Fried classificationj | ||

| Prefrail | 221/433 (51.0) | 204/417 (48.9) |

| Frail | 122/433 (28.2) | 124/417 (29.7) |

| Coronary artery disease, No./total (%)k | 133/444 (30.0) | 145/435 (33.3) |

| Echocardiographic parametersl | ||

| Aortic valve area, median (IQR), cm2 | (n = 442); 0.7 (0.6-0.9) | (n = 434); 0.7 (0.6-0.8) |

| Aortic valve peak gradient, median (IQR), mm Hg | (n = 453); 73 (59-89) | (n = 445); 74 (60-88) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, median (IQR), % | (n = 438); 57 (55-64) | (n = 437); 57 (55-64) |

| Moderate or severe aortic regurgitation, No./total (%) | 47/441 (10.7) | 58/436 (13.3) |

Abbreviations: CSHA, Canadian Study of Health and Aging; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Additional clinical details and medical history appear in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Recorded to assess the diversity of the study population, which may have implications for the external validity of the trial in different ethnic groups, and was determined by the site staff based on discussion with the participant or review of hospital records using a list of prespecified options corresponding to those used by the UK Office for National Statistics.

Specified as Italian for 2 participants and for 1 participant each as Arab, Maltese, and Polish.

Specified for 1 participant each as Arab, French, German, Greek Armenian, Greek Cypriot, Polish, and White Italian. No further details were reported for 1 participant.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Provides an estimate of the predicted 30-day mortality among patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement on the basis of a number of demographic and procedural variables.9,10

A risk model for estimating the predicted in-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery. The score is based on a combination of patient-, cardiac-, and operation-related factors. A higher score denotes a higher operative risk.11,12

Determined by site staff during the baseline clinical assessment and is a functional classification based on the extent to which the patient is limited by their symptoms (class I, no limitation of physical activity; class II, slight limitation of ordinary physical activity; class III, marked limitation of ordinary physical activity; class IV, symptoms at rest or with minimal activity).18

Evaluates function to generate a frailty score and was determined by the interviewer during the clinical assessment. Scores range from 1 (very fit) to 7 (severely frail); a higher score indicates greater frailty and an increased risk of death and other adverse outcomes.14

Identifies a frailty phenotype based on 5 criteria: unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, weakness (based on grip strength), slow walking speed, and low physical activity level. Patients are classified as not frail (did not meet frailty criteria), prefrail (met 1 or 2 criteria), or frail (met ≥3 criteria). The frailty phenotype is independently predictive of incident falls, worsening mobility or disability, hospitalization, and death.13

Presence of greater than 50% diameter stenosis in 1 or more coronary arteries on angiogram.

Reported by each study site.

Interventions

The median time from randomization to treatment was 40 days (IQR, 22-69 days) in the TAVI group and 37 days (IQR, 21-63 days) in the surgery group. In the TAVI group, a valve was deployed in 443 of the 450 participants (98.4%) who were treated as randomized. More than 1 valve was used in 5 participants. Details of the types of valves and access routes appear in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Of these 450 participants, conscious sedation or local (or regional) anesthesia was used in 313 (69.6%) and general anesthesia in 137 (30.4%). The median procedure duration was 82 minutes (IQR, 63-113 minutes). Coronary revascularization was performed as a staged procedure or during the same hospital admission in 33 of these 450 participants (7.3%).

In the surgery group, a valve was implanted in 416 of the 419 participants (99.3%) who were treated as randomized. Of these 419 participants, midline sternotomy was performed in 375 (89.5%) and minimally invasive surgery in 44 (10.5%). Details of the surgical valves appear in eTable 3 in Supplement 2. The median procedure duration was 182 minutes (IQR, 150-230 minutes), the median cardiopulmonary bypass time was 85 minutes (IQR, 66-106 minutes), and the median cross-clamp time was 63 minutes (IQR, 50-80 minutes). Concurrent coronary revascularization was performed in 90 of these 419 participants (21.5%).

After TAVI, the median stay in the intensive care unit was 0 days (IQR, 0-0 days) and was 0 days (IQR, 0-1 days) in the high-dependency unit. After surgery, the median stay in the intensive care unit was 1 day (IQR, 1-3 days) and was 1 day (IQR, 0-3 days) in the high-dependency unit. Further details appear in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. The percentage of participants discharged to home was 94.2% in the TAVI group and 82.6% in the surgery group. Details of anticoagulant and antithrombotic medication use at discharge and during follow-up appear in eTables 5-6 in Supplement 2.

Primary Outcome

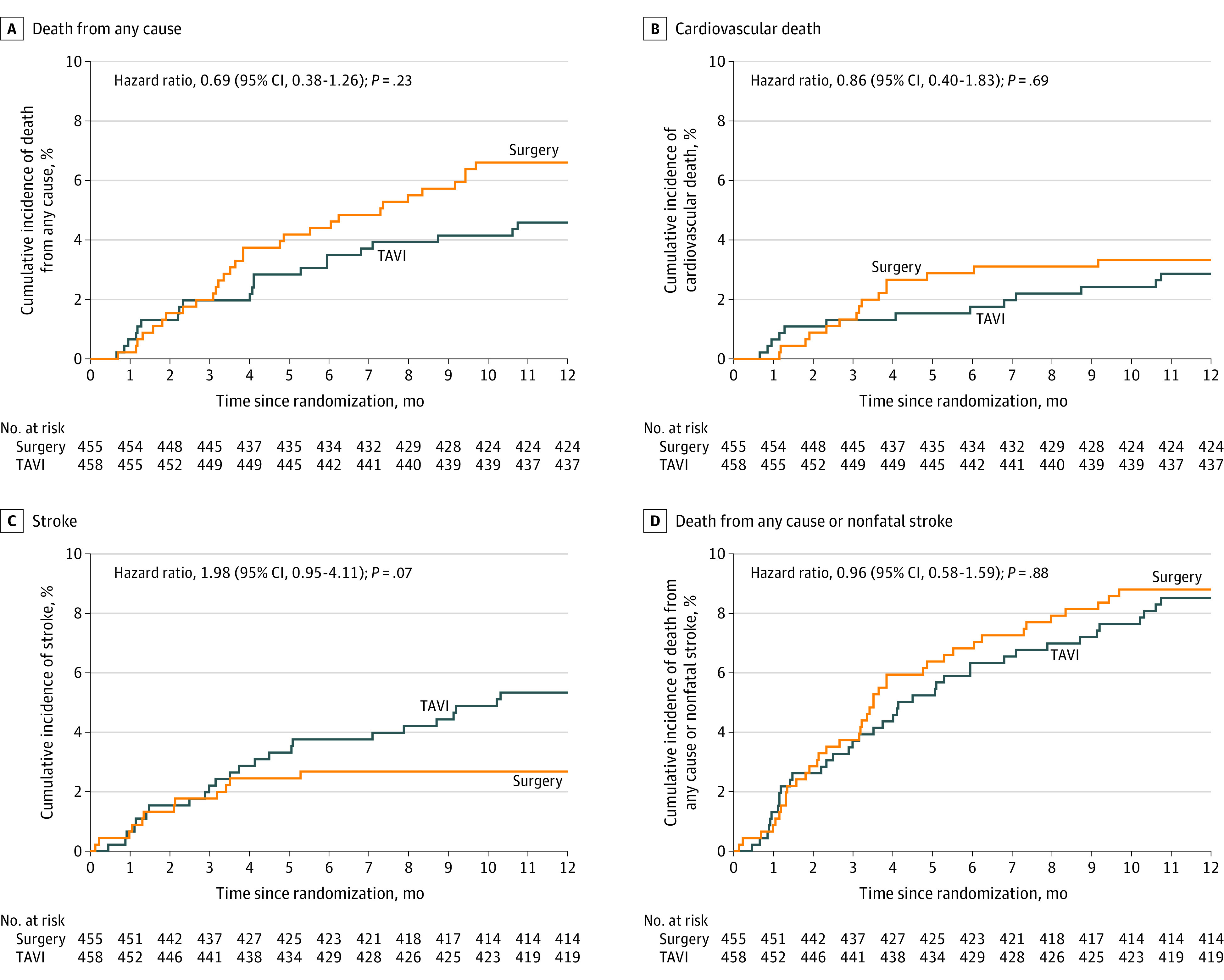

For the primary outcome, data were unavailable for 1 patient who withdrew from all follow-up. At 1 year, 21 participants (4.6%) in the TAVI group had died compared with 30 participants (6.6%) in the surgery group (adjusted absolute risk difference, −2.0% [1-sided 97.5% CI, −∞ to 1.2%]) (Table 2). The upper limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI (1.2%) was less than the prespecified noninferiority margin (5%), consistent with noninferiority of TAVI with respect to death from any cause at 1 year (P<.001 for noninferiority). The findings also were consistent with noninferiority in the sensitivity analysis allowing for missing data and in the per-protocol population (Table 2). The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for death from any cause was 0.69 (95% CI, 0.38 to 1.26; Table 3). The Kaplan-Meier plot for the primary outcome appears in Figure 2A. The treatment effect was consistent across prespecified subgroups (eFigure in Supplement 2). Details of deaths are provided in eTables 7-9 in Supplement 2.

Table 2. Noninferiority Analysis of Death From Any Cause at 1 Year (Primary Outcome).

| Analysis population | No. who died/total (%) | Absolute risk difference in death from any cause at 1 y, % (97.5% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVI | Surgery | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

| Primary analysis of population based on randomization groupb | 21/458 (4.6) | 30/454 (6.6) | −2.0 (−∞ to 1.0) | −2.0 (−∞ to 1.2) |

| Sensitivity analysis of population based on randomization group with allowance for missing datac | 21/458 (4.6) | 30/455 (6.6) | −2.0 (−∞ to 1.0) | −2.0 (−∞ to 1.2) |

| Per-protocol population (all participants who received the intervention as randomized)d | 19/450 (4.2) | 21/416 (5.0) | −0.8 (−∞ to 2.0) | −0.9 (−∞ to 2.0) |

Abbreviation: TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Adjusted for randomization minimization factors (age as a continuous variable, presence of coronary artery disease, which was considered to require revascularization if the patient was assigned to receive surgery, and clustering within sites).

One participant in the surgery group who withdrew was excluded from the noninferiority analysis of the primary outcome.

There was only 1 participant with missing data for the primary outcome; the participant was in the surgery group and was assumed to be alive at 1 year.

Includes those in whom the procedure was commenced but subsequently abandoned or converted to an alternative procedure.

Table 3. Primary Outcome and Event-Related Secondary Outcomes 1 Year After Randomization and Event-Related Secondary Outcomes 30 Days After the Procedure.

| Outcome | No. (%)a | Risk difference, % (95% CI) | Hazard ratio (95% CI)b | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVI (n = 458) |

Surgery (n = 455) |

Unadjusted | Adjustedc | Unadjusted | Adjustedc | ||

| Primary outcome 1 y after randomization d | |||||||

| Death from any cause | 21 (4.6) | 30 (6.6) | −2.0 (−5.0 to 1.0) | −2.0 (−5.2 to 1.2) | 0.69 (0.39 to 1.20) | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.26) | .23 |

| Event-related secondary outcomes 1 y after randomization d | |||||||

| Cardiovascular death | 13 (2.8) | 15 (3.3) | −0.5 (−2.7 to 1.8) | −0.5 (−2.8 to 1.9) | 0.85 (0.41 to 1.80) | 0.86 (0.40 to 1.83) | .69 |

| Stroke (fatal or nonfatal) | 24 (5.2) | 12 (2.6) | 2.6 (0.1 to 5.1) | 2.6 (0 to 5.2) | 1.98 (0.99 to 3.95) | 1.98 (0.95 to 4.11) | .07 |

| Composite outcomes | |||||||

| Death from any cause or nonfatal stroke | 39 (8.5) | 40 (8.8) | −0.3 (−3.9 to 3.4) | −0.3 (−4.4 to 3.9) | 0.96 (0.62 to 1.50) | 0.96 (0.58 to 1.59) | .88 |

| Death from any cause or nonfatal disabling stroke | 30 (6.6) | 35 (7.7) | −1.1 (−4.5 to 2.2) | −1.1 (−5.4 to 3.1) | 0.84 (0.52 to 1.38) | 0.84 (0.45 to 1.58) | .59 |

| Death from any cause, nonfatal stroke, or reintervention | 65 (14.2) | 74 (16.3) | −2.1 (−6.7 to 2.6) | −2.1 (−7.1 to 3.0) | 0.86 (0.62 to 1.20) | 0.86 (0.60 to 1.24) | .41 |

| Major bleeding events | 33 (7.2) | 92 (20.2) | −13.0 (−17.4 to −8.6) | −13.0 (−18.3 to −7.7) | 0.33 (0.22 to 0.49) | 0.33 (0.24 to 0.45) | <.001 |

| Conduction disturbances requiring permanent pacing | 65 (14.2) | 33 (7.3) | 6.9 (3.0 to 10.9) | 6.9 (2.9 to 11.0) | 2.04 (1.34 to 3.11) | 2.05 (1.43 to 2.94) | <.001 |

| Infective endocarditis | 5 (1.1) | 2 (0.4) | 0.7 (−0.5 to 1.8) | 0.7 (−0.5 to 1.8) | 2.44 (0.47 to 12.60) | 2.46 (0.54 to 11.17) | .24 |

| Kidney replacement therapy | 3 (0.7) | 8 (1.8) | −1.1 (−2.5 to 0.3) | −1.1 (−2.4 to 0.2) | 0.37 (0.10 to 1.39) | 0.37 (0.11 to 1.23) | .11 |

| Vascular complications | 47 (10.3) | 11 (2.4) | 7.8 (4.7 to 11.0) | 7.8 (4.2 to 11.4) | 4.43 (2.30 to 8.55) | 4.42 (2.54 to 7.71) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) | 0.2 (−1.2 to 1.6) | 0.2 (−1.3 to 1.7) | 1.18 (0.36 to 3.88) | 1.17 (0.33 to 4.20) | .81 |

| Any reintervention | 30 (6.6) | 37 (8.1) | −1.6 (−5.0 to 1.8) | −1.6 (−4.5 to 1.3) | 0.80 (0.49 to 1.29) | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.23) | .31 |

| Type of reintervention | |||||||

| On aortic valve complex | 10 (2.2) | 5 (1.1) | 1.1 (−0.6 to 2.7) | 1.1 (−0.5 to 2.6) | 1.98 (0.68 to 5.80) | 1.98 (0.72 to 5.42) | .19 |

| Othere | 21 (4.6) | 32 (7.0) | −2.4 (−5.5 to 0.6) | −2.5 (−5.2 to 0.3) | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.12) | 0.64 (0.37 to 1.11) | .11 |

| Event-related secondary outcomes 30 d after the procedure | |||||||

| (n = 455)f | (n = 431)f | ||||||

| Death from any cause | 8 (1.8) | 4 (0.9) | 0.8 (−0.7 to 2.3) | 0.8 (−0.9 to 2.5) | 1.90 (0.57 to 6.33) | 1.91 (0.52 to 7.03) | .33 |

| Cardiovascular death | 7 (1.5) | 3 (0.7) | 0.8 (−0.5 to 2.2) | 1.1 (−0.8 to 2.9) | 2.22 (0.57 to 8.59) | 2.22 (0.54 to 9.14) | .27 |

| Stroke (fatal or nonfatal) | 11 (2.4) | 10 (2.3) | 0.1 (−1.9 to 2.1) | 0.1 (−2.5 to 2.7) | 1.05 (0.44 to 2.46) | 1.05 (0.35 to 3.17) | .94 |

| Composite outcomes | |||||||

| Death from any cause or nonfatal stroke | 17 (3.7) | 14 (3.2) | 0.5 (−1.9 to 2.9) | 0.5 (−2.9 to 3.8) | 1.16 (0.57 to 2.35) | 1.16 (0.43 to 3.09) | .77 |

| Death from any cause or nonfatal disabling stroke | 14 (3.1) | 11 (2.6) | 0.5 (−1.7 to 2.7) | 0.5 (−2.9 to 3.9) | 1.21 (0.55 to 2.67) | 1.21 (0.35 to 4.16) | .76 |

| Death from any cause, nonfatal stroke, or reintervention | 33 (7.3) | 40 (9.3) | −2.0 (−5.7 to 1.6) | −2.0 (−6.1 to 2.1) | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.24) | 0.78 (0.46 to 1.31) | .35 |

| Major bleeding events | 25 (5.5) | 84 (19.5) | −14.0 (−18.3 to −9.7) | −14.0 (−19.4 to −8.6) | 0.27 (0.17 to 0.42) | 0.27 (0.19 to 0.37) | <.001 |

| Conduction disturbances requiring permanent pacing | 50 (11.0) | 29 (6.7) | 4.3 (0.5 to 8.0) | 4.3 (0.2 to 8.3) | 1.72 (1.09 to 2.71) | 1.72 (1.13 to 2.61) | .01 |

| Infective endocarditisg | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Kidney replacement therapy | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.6) | −1.4 (−2.7 to −0.1) | −1.4 (−2.8 to 0) | 0.13 (0.02 to 1.10) | 0.14 (0.01 to 1.24) | .08 |

| Vascular complications | 46 (10.1) | 10 (2.3) | 7.8 (4.7 to 10.9) | 7.8 (4.2 to 11.4) | 4.44 (2.24 to 8.79) | 4.43 (2.53 to 7.78) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarctiong | 3 (0.7) | 0 | |||||

| Any reintervention | 18 (4.0) | 27 (6.3) | −2.3 (−5.2 to 0.6) | −2.3 (−5.1 to 0.5) | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.15) | 0.63 (0.34 to 1.17) | .15 |

| Type of reintervention | |||||||

| On aortic valve complex | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0.6 (−0.3 to 1.6) | 0.6 (−0.3 to 1.6) | 3.82 (0.43 to 34.21) | 3.80 (0.42 to 34.20) | .23 |

| Othere | 15 (3.3) | 26 (6.0) | −2.7 (−5.5 to 0) | −2.7 (−5.4 to −0.1) | 0.55 (0.29 to 1.03) | 0.55 (0.28 to 1.08) | .08 |

Abbreviation: TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

The data were analyzed with participants included in the groups to which they were randomized, irrespective of the treatment received. Additional secondary outcomes, including duration of hospital stay, echocardiographic outcomes, functional capacity, and quality of life, are reported in eTable 4 and eTables 10-18 in Supplement 2. Cause of death (eTable 7 in Supplement 2) and all events were adjudicated by the end points and events committee, with reference to outcome definitions based on criteria from the Valve Academic Research Consortium-215 consensus document (eMethods 5 in Supplement 2). Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings for the analyses of the secondary outcomes should be interpreted as exploratory.

A visual analysis of log-log survival plots and Schoenfeld residuals was consistent with the assumption of proportional hazards.

Adjusted for randomization minimization factors (age as a continuous variable, presence of coronary artery disease, which was considered to require revascularization if the patient was assigned to receive surgery, and clustering within sites using robust SEs). Risk differences and delta method–estimated SEs were obtained from logistic regression models.

The analysis population included all randomized participants and applied censoring at the time when a participant was lost to follow-up, which is in line with the Cox proportional hazards regression model. One participant in the surgery group who withdrew and was excluded from the noninferiority analysis of the primary outcome (presented in Table 2) was included in this analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes with censoring at the time of withdrawal. The participant was assumed not to have had an event if no relevant event was reported prior to withdrawal.

Excludes permanent pacemaker implantation for conduction disturbance, which is reported separately, but includes pacemaker implantation for other indications.

The analysis population included all randomized participants who received an intervention, whether as randomized or otherwise. In the TAVI group, 3 of the randomized participants were excluded because they did not undergo an intervention. In the surgery group, 24 of the randomized participants were excluded, comprising 19 who received no intervention, 3 who received their intervention more than 1 year after randomization (1 of these participants received TAVI and is thus shown as a crossover in Figure 1), and 1 who crossed over and received TAVI, for whom the procedure date was not known.

The risk difference and hazard ratio could not be calculated.

Figure 2. Time-to-Event Curves for the Primary Outcome and Major Secondary Outcomes.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis at 1 year after randomization. All patients were followed up to the time of an event, withdrawal from the study, or 1 year after randomization. The hazard ratios are specific to the 1-year outcomes. The P values were derived from a Cox proportional hazards model, which was adjusted for randomization minimization factors and used robust SEs to account for clustering of outcomes by randomization site. Cause of death (cardiovascular vs noncardiovascular) and stroke events were adjudicated by the end points and events committee, with reference to outcome definitions based on criteria from the Valve Academic Research Consortium-215 consensus document (eMethods 5 in Supplement 2). TAVI indicates transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Secondary Outcomes

The median duration of the hospital stay was 3 days (IQR, 2-5 days) after TAVI and was 8 days (IQR, 6-13 days) after surgery. The event-related secondary clinical outcomes appear in Table 3. After the procedure, there were significantly fewer major bleeding events at 30 days in the TAVI group (5.5%) compared with in the surgery group (19.5%) (adjusted HR, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.19-0.37]; P < .001) and the incidence of major bleeding events at 1 year after randomization was 7.2% vs 20.2%, respectively (adjusted HR, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.24-0.45]; P < .001).

However, there was a significantly higher incidence of vascular complications at 30 days after the procedure in the TAVI group (10.1%) compared with the surgery group (2.3%) (adjusted HR, 4.43 [95% CI, 2.53-7.78]; P < .001) and the incidence of vascular complications at 1 year after randomization was 10.3% vs 2.4%, respectively (adjusted HR, 4.42 [95% CI, 2.54-7.71]; P < .001). The incidence of conduction disturbances requiring permanent pacing at 30 days after the procedure was 11.0% in the TAVI group vs 6.7% in the surgery group (adjusted HR, 1.72 [95% CI, 1.13-2.61]; P = .01) and the incidence at 1 year after randomization was 14.2% vs 7.3%, respectively (adjusted HR, 2.05 [95% CI, 1.43-2.94]; P < .001).

There was no significant difference in the rate of stroke at 30 days (2.4% in the TAVI group vs 2.3% in the surgery group; adjusted HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 0.35-3.17]; P = .94) or at 1 year (5.2% vs 2.6%, respectively; adjusted HR, 1.98 [95% CI, 0.95-4.11]; P = .07). There was no significant difference in the rate of cardiovascular death, the composite of death from any cause or nonfatal stroke, or for other clinical outcomes at 30 days after the procedure or at 1 year after randomization (Figure 2B, C, and D and Table 3).

Echocardiographic findings are reported in eTables 10-11 in Supplement 2. At 6 weeks, the mean aortic valve mean gradient was 10.36 mm Hg in the TAVI group vs 10.01 mm Hg in the surgery group (adjusted difference, 0.31 mm Hg [95% CI, −0.53 to 1.15 mm Hg]; P = .47) and the mean aortic valve effective orifice area was 1.53 cm2 vs 1.51 cm2, respectively (adjusted difference, 0.04 cm2 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.09 cm2]; P = .22). These hemodynamic improvements were sustained and not significantly different between the groups at 1 year (eTable 10 in Supplement 2).

At 6 weeks, mild aortic regurgitation was significantly more prevalent in the TAVI group (43.7%) than in the surgery group (12.3%) as well as moderate aortic regurgitation (2.4% vs 0.9%, respectively) (adjusted odds ratio for mild, moderate, or severe aortic regurgitation combined vs none, 5.37 [95% CI, 3.86 to 7.46]; P < .001). No instances of severe aortic regurgitation were reported. At 1 year, mild aortic regurgitation was significantly more prevalent in the TAVI group (38.3%) than in the surgery group (11.7%) as well as moderate aortic regurgitation (2.3% vs 0.6%, respectively) (adjusted odds ratio for mild, moderate, or severe aortic regurgitation combined vs none, 4.89 [95% CI, 3.08 to 7.75]; P < .001).

There was a reduction in the prevalence of angina in both groups at 6 weeks and at 1 year with no statistically significant between-group difference (eTable 12 in Supplement 2). There was a significantly greater improvement in New York Heart Association class, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire scores, and 6-minute walk distance in the TAVI group at 6 weeks; however, there was no significant between-group difference at 1 year (eTables 13-15 in Supplement 2). There was significantly greater independence in activities of daily living after TAVI at 6 weeks but no significant difference at 1 year (eTable 16 in Supplement 2). There were no significant differences in cognitive function (eTable 17 in Supplement 2). The EuroQol EQ-5D-5L utility and EQ visual analog scale scores improved within 2 weeks after TAVI and the benefits were sustained at 1 year. In the surgery group, quality of life was diminished at 2 weeks. Quality of life improved after 6 weeks but utility and visual analog scale scores were significantly higher in the TAVI group and the utility score remained so at 1 year (eTable 18 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

There were a total of 483 serious adverse events in the TAVI group and 545 in the surgery group. The number of participants with at least 1 serious adverse event was 252 (55%) in the TAVI group and 255 (56%) in the surgery group (eTable 19 in Supplement 2). Details of relatedness to the interventions and the type of events (classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) appear in eTables 20-21 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

In this trial that enrolled patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk, TAVI was noninferior to surgery with respect to all-cause mortality at 1 year. These findings are concordant with those from other trials in patients with intermediate risk29,30 or low risk31,32,33 and in recent meta-analyses.34,35

In contrast to previous trials, this trial was pragmatic, publicly funded, and designed to compare a TAVI strategy using any valve type and access route vs a conventional surgical strategy in a broad range of patients. Inclusion was based on clinical equipoise regarding the treatment options and not bound by prespecified risk scores. Entry to the trial thus reflected a site-specific assessment of risk, encompassing factors not reflected in the risk scores such as frailty. This approach also allowed for the temporal evolution of clinicians’ individual perspectives on the risk threshold for considering TAVI as an alternative to surgery, with increasing local and global experience of the procedure as recruitment progressed. The inclusion of every center performing TAVI in the UK and having few exclusion criteria further increased the likelihood that the trial outcomes reflected effectiveness in routine clinical practice in the UK rather than efficacy under optimal conditions.

When the trial was conceived in 2009, it was envisaged that it would recruit patients at intermediate or high operative risk. However, clinical practice had evolved by the time enrollment commenced in 2014. With a median Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality risk score of 2.6%, the trial population would conventionally be classified as low risk. This was reflected in the procedural outcomes, with 30-day mortality of 0.9% in the surgery group, which is similar to the 1.1% in the surgery group in the PARTNER 3 (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves 3) trial32 and the 1.3% in the surgery group in the Evolut (Evolut Surgical Replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Low Risk Patients) trial.33 However, the 1-year surgical mortality in the current trial (6.6%) was higher than in the PARTNER 3 trial (2.5%) and in the Evolut trial (3.0%) most likely reflecting the older age, increased comorbidity, and increased prevalence of frailty in the patients in the current trial. The treatment effect was consistent in a subgroup analysis assessing the interaction of these factors and in patients with vs those without the need for coronary revascularization.

Improvements in aortic valve area and gradient were similar between the groups but mild and moderate aortic regurgitation were more prevalent after TAVI. Aortic regurgitation was predominantly mild and may partly reflect the use of earlier-generation TAVI valves in the initial recruitment phase and the inclusion of patients with bicuspid valves. The prognostic significance of mild aortic regurgitation is uncertain and long-term follow-up is required to determine its clinical effect. Concerns have been raised about the increased frequency of subclinical valve leaflet thrombosis after TAVI compared with surgery.36,37 This was not examined and no specific antithrombotic or anticoagulant regimen was mandated to prevent subclinical valve leaflet thrombosis. However, the early improvements in valve areas and gradients were sustained in both groups at 1 year. There was some late divergence of the event curves for stroke with a higher frequency in the TAVI group at 1 year, but the number of events was small and the difference was not statistically significant.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the lack of site-specific screening data makes it difficult to determine what proportion of the total referrals for aortic valve replacement the trial population represents and how selected was the group that was reviewed by the multidisciplinary team at each site. Background data on all patients treated with TAVI or surgery are available from the relevant national registries26,27,28 and a comprehensive analysis is planned.

Second, the data presented in this report only address 1-year outcomes. Further follow-up is required to monitor clinical outcomes and the need for reintervention in the long-term. There is some uncertainty about the long-term durability of TAVI valves. Data from the UK TAVI registry found the incidence of moderate structural valve deterioration to be 8.7% and severe structural valve deterioration to be 0.4% after a median follow-up of 5.8 years; however, the data predominantly relate to early-generation devices and their reliability is limited by high mortality and possible survival bias.38 Five-year follow-up from the intermediate-risk PARTNER 2 trial showed more frequent aortic valve reintervention after TAVI (3.2%) compared with surgery (0.8%).39 Pending long-term follow-up, treatment selection should be individualized and take account of these uncertainties, particularly in younger patients with longer life expectancies.

Conclusions

Among patients aged 70 years or older with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis and moderately increased operative risk, TAVI was noninferior to surgery with respect to all-cause mortality at 1 year.

eAppendix. Participating Sites and Investigators

eMethods 1. Trial Management and Administration

eMethods 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 3. Patient Identification Process

eMethods 4. Primary Endpoint and Secondary Outcomes

eMethods 5. Outcome Definitions

eMethods 6. Statistical Methods

eFigure. Primary Endpoint (Death from Any Cause) Sub-Group Analysis

eTable 1. Additional Clinical Details and Past Medical History at Baseline

eTable 2. Details of TAVI Valves Deployed

eTable 3. Details of Surgical Valves Deployed

eTable 4. Length of Stay - Hospital, Intensive Care Unit & High Dependency Unit

eTable 5. Use of Anticoagulant Medication

eTable 6. Use of Antithrombotic Medication

eTable 7. Primary Causes of Death

eTable 8. Deaths in Relation to TAVI Access Route

eTable 9. Deaths in Relation to Peri-Procedural Revascularization

eTable 10. Echocardiographic Data

eTable 11. Echocardiographic Data

eTable 12. Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Angina Grade

eTable 13. New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class

eTable 14. Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)

eTable 15. Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

eTable 16. Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) Scale

eTable 17. Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE)

eTable 18. Quality of Life - EuroQol EQ-5D-5L

eTable 19. Frequency of Serious Adverse Events

eTable 20. Causality of Serious Adverse Events

eTable 21. MedDRA Classification of Serious Adverse Events

eReferences

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation. 2002;106(24):3006-3008. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047200.36165.B8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597-1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187-2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. ; PARTNER 1 Trial Investigators . 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2477-2484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al. ; US CoreValve Clinical Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1790-1798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gleason TG, Reardon MJ, Popma JJ, et al. ; CoreValve US Pivotal High Risk Trial Clinical Investigators . 5-year outcomes of self-expanding transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(22):2687-2696. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Généreux P, Webb JG, Svensson LG, et al. ; PARTNER Trial Investigators . Vascular complications after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(12):1043-1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conte JV, Hermiller J Jr, Resar JR, et al. Complications after self-expanding transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;29(3):321-330. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Brien SM, Shahian DM, Filardo G, et al. ; Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force . The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 2—isolated valve surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1)(suppl):S23-S42. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Society of Thoracic Surgeons . STS short-term risk calculator. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://www.sts.org/resources/risk-calculator

- 11.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41(4):734-744. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EuroSCORE Study Group . EuroSCORE II calculator. Accessed February 5, 2022. http://www.euroscore.org/calc.htm

- 13.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. ; Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group . Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489-495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(15):1438-1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(12):1497-1500. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.19.12.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campeau L. Letter: grading of angina pectoris. Circulation. 1976;54(3):522-523. doi: 10.1161/circ.54.3.947585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Criteria Committee of the American Heart Association Affiliate NYC . Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. 9th ed. Little Brown & Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lincoln NB, Gladman JR. The extended activities of daily living scale: a further validation. Disabil Rehabil. 1992;14(1):41-43. doi: 10.3109/09638289209166426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipkin DP, Scriven AJ, Crake T, Poole-Wilson PA. Six minute walking test for assessing exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6521):653-655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6521.653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.EuroQol Group . EuroQol EQ-5D-5L. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/

- 23.Rector TS, Kubo SH, Cohn JN. Patients’ self-assessment of their congestive heart failure, part 2: content, reliability and validity of a new measure, the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Heart Fail. 1987;3:198-209. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bridgewater B, Kinsman R, Walton P, et al. Demonstrating Quality: The Sixth National Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Report. Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the risk? a simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):288-302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research . National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit: 2020 summary report (2016/17-2018/19 data). Accessed February 5, 2022. https://www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National-Adult-Cardiac-Surgery-Audit-NACSA-FINAL.pdf

- 27.Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery in Great Britain and Ireland . National cardiac surgery activity and outcome report 2002-2016. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://scts.org/_userfiles/pages/files/sctscardiacbluebook2020_11_20tnv2.pdf

- 28.British Cardiovascular Intervention Society . United Kingdom national audit of transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Accessed February 5, 2022. https://www.bcis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BCIS-Audit-2019-20-data-TAVI-subset-as-26-04-2020-for-web.pdf

- 29.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER 2 Investigators . Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1609-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. ; SURTAVI Investigators . Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1321-1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thyregod HG, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: 1-year results from the all-comers NOTION randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(20):2184-2194. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. ; PARTNER 3 Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1695-1705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. ; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators . Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):1706-1715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siontis GCM, Overtchouk P, Cahill TJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs surgical aortic valve replacement for treatment of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(38):3143-3153. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolkailah AA, Doukky R, Pelletier MP, Volgman AS, Kaneko T, Nabhan AF. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in people with low surgical risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):CD013319. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013319.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, et al. Possible subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2015-2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarty T, Søndergaard L, Friedman J, et al. ; RESOLVE; SAVORY Investigators . Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. Lancet. 2017;389(10087):2383-2392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30757-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blackman DJ, Saraf S, MacCarthy PA, et al. Long-term durability of transcatheter aortic valve prostheses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(5):537-545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER 2 Investigators . Five-year outcomes of transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):799-809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Participating Sites and Investigators

eMethods 1. Trial Management and Administration

eMethods 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 3. Patient Identification Process

eMethods 4. Primary Endpoint and Secondary Outcomes

eMethods 5. Outcome Definitions

eMethods 6. Statistical Methods

eFigure. Primary Endpoint (Death from Any Cause) Sub-Group Analysis

eTable 1. Additional Clinical Details and Past Medical History at Baseline

eTable 2. Details of TAVI Valves Deployed

eTable 3. Details of Surgical Valves Deployed

eTable 4. Length of Stay - Hospital, Intensive Care Unit & High Dependency Unit

eTable 5. Use of Anticoagulant Medication

eTable 6. Use of Antithrombotic Medication

eTable 7. Primary Causes of Death

eTable 8. Deaths in Relation to TAVI Access Route

eTable 9. Deaths in Relation to Peri-Procedural Revascularization

eTable 10. Echocardiographic Data

eTable 11. Echocardiographic Data

eTable 12. Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) Angina Grade

eTable 13. New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class

eTable 14. Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)

eTable 15. Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

eTable 16. Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) Scale

eTable 17. Mini-Mental-State-Examination (MMSE)

eTable 18. Quality of Life - EuroQol EQ-5D-5L

eTable 19. Frequency of Serious Adverse Events

eTable 20. Causality of Serious Adverse Events

eTable 21. MedDRA Classification of Serious Adverse Events

eReferences

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement