Abstract

Background

COVID19 pandemic had a huge impact on global mental health. Health students, because of their age and status, are a more at-risk population. National survey during the first wave already found high levels of psychological distress.

Objective

This nationwide study aimed to assess health's student mental health during the third wave in France.

Methods

We did an online national cross-sectional study, which addressed all health students from April 4th to May 11th 2021. The questionnaire included sociodemographic and work conditions questions, Kessler 6 scale, and numeric scales.

Results

16,937 students answered, including 54% nurse and 16% medical students. Regarding K6 scale, 14% have moderate (8–12) and 83% high (≥13) level of psychological distress. In multivariate analysis, being a man (OR = 0.54, 95% CI [0.48; 0.60], p < 0.001) and not living alone (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.62; 0.82], p < 0.001), are associated with a reduced risk of psychological distress. Not having the ability to isolate themselves (OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.39; 1.81], p < 0.001), and having low (OR = 2.31, 95% CI [2.08; 2.56], p < 0.001) or important (OR = 4.58, 95% CI [3.98; 5.29], p < 0.001) financial difficulties are associated with an increased risk of psychological distress.

Limitations

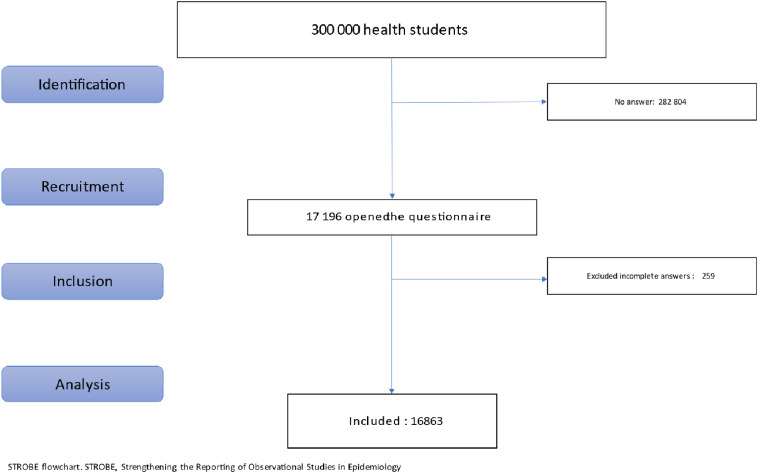

The response rate was low regarding the target population (300,000 health students).

Conclusion

Compared to the first national survey, we noticed mental health deterioration. Psychological distress (83% high level versus 21%), substance use (21% versus 13%), and psychotropic treatment use (18% versus 7.3%) hugely increased. These results highlighted the need to increase support actions for health students.

Keywords: Health students, Mental health, Psychological distress, COVID 19

1. Introduction

Since the COVID19 pandemic's beginning, psychiatrists and searchers have been worried about youths' increased suicide and mental illness rates (“Joint Statement - COVID-19 impact likely to lead to increased rates of suicide and mental illness”, 2020). In the general student population, a recent meta-analysis found the prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and sleep disturbances were 34%, 32%, and 33%, respectively (Deng et al., 2021). In France, a study during the first lockdown found the prevalence of suicidal thoughts, severe distress, high perceived stress, severe depression, and high level of anxiety were 11.4%, 22.4%, 24.7%, 16.1%, and 27.5%, respectively (Wathelet et al., 2020).

Health students (nurse, medicine, dental, pharmacist, midwife, audioprosthesist, physiotherapist…) have a special place because they are students and yet caregivers. Some were enrolled in the fight against pandemics to make up for the lack of staff, especially nurse students. During the first wave, a nationwide survey in US medical students found a decline in their overall wellness during COVID-19 and increased anxiety (OR = 3.37) and depression (OR = 2.05) (Nikolis et al., 2021). In dental students in Germany, the prevalence of moderate or severe depression, anxiety, and stress were 19.6%, 14.2%, and 15.6%, respectively (Mekhemar et al., 2021). In Saudi Arabia, a longitudinal study found dental students' mental health deterioration with significant differences in the outcomes based on gender, university, class year, and survey time during COVID-19 lockdown (Hakami et al., 2021). In nurse students, an Iceland study found that 26.4% estimated having moderate/bad mental health, and 17.6% did not receive enough support related to their studies (Sveinsdóttir et al., 2021).

In France, we did a national study on health students using Kessler 6 scale (Kessler et al., 2010) and found that 39% of students had moderate (8–12) and 21% had a high level (≥13) of distress (Rolland et al., 2022). During the second wave, a study in sixteen ICUs found anxiety and depressive symptoms were reported by 60% and 36% of caregivers, respectively (Azoulay et al., 2021). A survey after the second lockdown found anxiety and depressive symptoms in 38% and 23% of students, respectively (Roux et al., 2021).

One year after, the pandemic is still here. In Belgium, a study assessed psychiatric symptoms among higher education students one year after the pandemic. They found that 50.6% of students presented anxiety symptoms, 55.1% had depressive symptoms, 20.8% had suicidal thoughts, 42.4% felt their financial situation had deteriorated, and 39.1% had dropping out thoughts (Schmits et al., 2021).

In France, the population experimented 2 other waves and lockdowns. Most universities stayed close with online classes. Health's students continued to help in the hospital and had their teaching and exams disrupted.

This is why the Center for the Quality of Life of Health Students (Centre National d'Appui à la qualité de vie des etudiants en santé, CNA) and the Research Center in Epidemiology and Population Health (Centre de recherche en Epidémiologie et Santé des Populations, CESP) repeated their initial survey (Rolland et al., 2022). Few modifications have been made. We add a new category of students: the first year of medicine and other health studies: PASS. PASS means Parcours d'Accès Spécifique Santé (Specific Health Access Pathway) and began in September 2020, following a reform decided by the Ministry of Health. It is a 1st year common in Medicine, Midwifery, Odontology, Pharmacy, and Physiotherapy. There is a competitive exam at the end of the year with a limited number of places in each field and each university. The reform has notably removed the possibility of repeating a year in case of failure (“Les études de santé”, n.d.). We also add two questions. One on subjective financial difficulties because 33% of students declared having financial difficulties during the first lockdown (“OVE Infos n°43 | Student life in 2020”, n.d.), and it's a known risk factor for mental health (Sheldon et al., 2021); a second one on dropping out thoughts.

1.1. Aims of the study

The goal was to assess health's students' mental health during the third wave using the same questionnaire as during the first wave.

2. Material and methods

We conducted an online survey on health students from April 4th to May 11th 2021 (during the third lockdown in France, one year after the first one).

The methodology was similar to the previous investigation during the first (Rolland et al., 2022). The questionnaire link has been sent to health students by the universities' enrolment services and posted on social media (Facebook and Twitter) by students' representative organizations. Due to the health situation, students were not at the university, and therefore there were no posters of the survey in the universities.

2.1. Population

Health students came from all academic fields of health and from the first year of study to the final year. The length of health studies varied from 3 years for nurses students to 11 years for medical students. Students in the following fields were included in the study: medicine, pharmacy, nursing, midwifery, odontology (dental students), occupational therapy, orthoptic, speech therapy, psychomotricity, and hearing care (Fig. 1). Medical, pharmacist and dental students have a longer academic program, which can be divided into three stages (preclinic, clinic, and residents).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart.

2.2. Questionnaire

The questionnaire is similar to the previous study (Rolland et al., 2022). It started with sociodemographic questions including age, field of study, year of study, sex, leaving alone or not, and ability to isolate themself at home. We added questions on subjective financial difficulties and dropout thoughts.

We used numerical scales, going from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“very much”), to measure psychological distress, information level about available support systems, their need for support, and quality of sleep. We grouped data in “low” (0–4), “moderate” (5–7) and “high” (8–10). Dropping out thoughts questions used a 7 items scale: “Never,” “A few times a year”, “Once a month”, “A few times a month”, “Once a week”, “A few times a week”, “Every day”. We grouped data in “Yes” if the answer was once a week or more frequent. Questions in French and English are in supplementary data 1.

We used Kessler's K6, a validated scale in 6 items to evaluate psychological distress according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th (DSM4). For the scale's validity, a study found that K6 predicted severe mental illness, with the median value of AUC across countries equal to 0.83 (range 0.76–0.89) (Kessler et al., 2010). For the scale's reliability, the alpha Cronbach coefficient in large Canadian studies varied between 0.768 and 0.782 (Marleau et al., 2022). A study including 10,000 students at the University of Montreal, therefore mainly French-speaking, found a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.84 for the K6 (“Enquête sur la santé psychologique étudiante: quand la parole rejoint la théorie | Acfas”, n.d.). K6's French version has been used for more than a decade (Marleau et al., 2022). Answers go on Likert's scale from 1(“Every Time”) to 5 (“Never”). The result is calculated by adding the scores of each item. K6 has good psychometric properties, according to a recent study. The cut-off usually chosen is 13 to discriminate between the presence or absence of serious mental illness (Cotton et al., 2021). Few studies also used 3 categories: <8 no problem, 8–12 moderate distress and ≥13 high distress (Furukawa et al., 2003; Institut national de and santé publique du Québec, n.d.; Kessler et al., 2010).

Two Yes/No questions were also used to measure medical psychotropic drugs and non-medical psychotropic substances (alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, …) consumption.

2.3. Ethics

The questionnaires were collected anonymously, and IP addresses were not recovered. Data were stored in an offline database for further analysis. Respondents were informed, and they gave their informed consent to participate. We used LimeSurvey©, an online tool that respects European Data Protection Regulation (“General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Official Legal Text”, n.d.). This study received agreement from the Paris Saclay Ethics and Research Committee (reference: CER-Paris-Saclay-2020-035).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Descriptive information was provided as percentages. We did a visual representation of the variables (histograms) to check their normality. Statistical significance was tested in bivariate analyses using the chi-square test to compare the prevalence of the groups. Subsequently, logistic regression models were performed for statistically significant associations in bivariate analyses for the K6 scale and dropping thoughts. Statistical significance was evaluated using two-sided tests with an alpha risk set a priori at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 1.4.869.

3. Results

3.1. Population

Among the 16,937 students who answered, 54% were nurses students, and 16% were medical students. Because some specialities have few respondents (Supplementary Table 1), we regrouped them. There were significant differences between specialities for age, sex, year of study, leaving alone, ability to isolate, and subjective financial difficulties (p < 0.001 for all) (Table 1 ). The percentage of female students was higher among nurses than among dentists/pharmacists/midwives (90% vs 81%), who had a higher percentage of females than medical students (81% vs 74%). 91% of PASS students were under 22 years old compared to 46% of nursing students, 24% of dentists/pharmacists/midwives students and 18% of medical students. Nursing students had less opportunity to isolate themselves (77%) than medical or PASS students (85%) and were more likely to experience significant financial difficulties than medical, dentists/pharmacists/midwives or PASS students (37% vs 11, 17 and 18% respectively).

Table 1.

Population description by specialty.

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 16,937 (100%)a | Nurse, N = 9207 (54%)a | Medicine, N = 2623 (16%)a | Dental-pharmacist-midwife, N = 2228 (13%)a | Others, N = 2099 (12%)a | PASS, N = 780 (5%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | 14,283 (85%) | 8260 (90%) | 1933 (74%) | 1782 (81%) | 1703 (83%) | 605 (78%) |

| Men | 2509 (15%) | 882 (9.6%) | 676 (26%) | 422 (19%) | 359 (17%) | 170 (22%) |

| Unknown | 145 | 65 | 14 | 24 | 37 | 5 |

| Age | ||||||

| 19–21 | 6703 (40%) | 4276 (46%) | 484 (18%) | 536 (24%) | 697 (33%) | 710 (91%) |

| 22–24 | 5074 (30%) | 2413 (26%) | 864 (33%) | 1055 (47%) | 737 (35%) | 5 (0.6%) |

| 25–27 | 1678 (9.9%) | 478 (5.2%) | 701 (27%) | 359 (16%) | 140 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| 27 years and more | 3482 (21%) | 2040 (22%) | 574 (22%) | 278 (12%) | 525 (25%) | 65 (8.3%) |

| Year of study | ||||||

| 1–3 | 13,504 (80%) | 9104 (99%) | 886 (34%) | 1007 (45%) | 1733 (83%) | 774 (99%) |

| 4–6 | 1869 (11%) | 47 (0.5%) | 686 (26%) | 834 (37%) | 301 (14%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| 6 and more | 1564 (9.2%) | 56 (0.6%) | 1051 (40%) | 387 (17%) | 65 (3.1%) | 5 (0.6%) |

| Live alone | ||||||

| Yes | 2553 (15%) | 1452 (16%) | 555 (21%) | 307 (14%) | 215 (10%) | 24 (3.1%) |

| No | 14,053 (85%) | 7561 (84%) | 2036 (79%) | 1881 (86%) | 1834 (90%) | 741 (97%) |

| Unknown | 331 | 194 | 32 | 40 | 50 | 15 |

| Ability to isolate | ||||||

| Yes | 12,586 (80%) | 6565 (77%) | 2055 (83%) | 1763 (84%) | 1585 (82%) | 618 (85%) |

| No | 3201 (20%) | 1966 (23%) | 427 (17%) | 344 (16%) | 354 (18%) | 110 (15%) |

| Unknown | 1,15 | 676 | 141 | 121 | 160 | 52 |

| Subjective financial difficulties | ||||||

| No | 4885 (31%) | 1754 (21%) | 1373 (55%) | 868 (41%) | 578 (30%) | 312 (46%) |

| Low | 6316 (40%) | 3492 (42%) | 868 (34%) | 892 (42%) | 819 (42%) | 245 (36%) |

| High | 4436 (28%) | 3140 (37%) | 276 (11%) | 349 (17%) | 551 (28%) | 120 (18%) |

| Unknown | 1,3 | 821 | 106 | 119 | 151 | 103 |

Statistical tests performed: chi-square test of independence: all p values are <0.001.

Statistics presented: n (%).

3.2. Psychological distress: K6 scale

Regarding the K6 scale, 14% have moderate (score between 8 and 12) and 83% (score ≥ 13) high levels of psychological distress (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Population repartition regarding Kessler's score.

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 17,140a | Low, N = 406a (3%) |

Moderate, N = 2331a (14%) |

High, N = 14,403a (83%) |

p-Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.001 | ||||

| Women | 14,345 (100%) | 280 (2.0%) | 1809 (13%) | 12,256 (85%) | |

| Men | 2518 (100%) | 121 (4.8%) | 489 (19%) | 1908 (76%) | |

| Unknown | 277 | 5 | 33 | 239 | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||||

| 19–21 | 6819 (100%) | 99 (1.5%) | 778 (11%) | 5942 (87%) | |

| 22–24 | 5115 (100%) | 105 (2.1%) | 634 (12%) | 4376 (86%) | |

| 25–27 | 1695 (100%) | 46 (2.7%) | 279 (16%) | 1370 (81%) | |

| 27 years and more | 3511 (100%) | 156 (4.4%) | 640 (18%) | 2715 (77%) | |

| Live alone | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 2564 (100%) | 44 (1.7%) | 294 (11%) | 2226 (87%) | |

| No | 14,110 (100%) | 351 (2.5%) | 1972 (14%) | 11,787 (84%) | |

| Unknown | 466 | 11 | 65 | 390 | |

| Subjective financial difficulties | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 12,637 (100%) | 318 (2.5%) | 1843 (15%) | 10,476 (83%) | |

| Moderate | 3216 (100%) | 51 (1.6%) | 315 (9.8%) | 2850 (89%) | |

| High | 1287 | 37 | 173 | 1077 | |

| Unknown | <0.001 | ||||

| Ability to isolate | 4898 (100%) | 213 (4.3%) | 1062 (22%) | 3623 (74%) | |

| Yes | 6342 (100%) | 108 (1.7%) | 751 (12%) | 5483 (86%) | |

| No | 4463 (100%) | 50 (1.1%) | 294 (6.6%) | 4119 (92%) | |

| Unknown | 1437 | 35 | 224 | 1178 | |

| Specialty | <0.001 | ||||

| Nurse | 9207 (100%) | 225 (2.4%) | 1189 (13%) | 7793 (85%) | |

| Medicine | 2623 (100%) | 77 (2.9%) | 444 (17%) | 2102 (80%) | |

| Dental-pharmacy-midwife | 2228 (100%) | 37 (1.7%) | 286 (13%) | 1905 (86%) | |

| Others | 2099 (100%) | 57 (2.7%) | 299 (14%) | 1743 (83%) | |

| PASS | 780 (100%) | 5 (0.6%) | 91 (12%) | 684 (88%) | |

| Unknown | 203 | 5 | 22 | 176 |

Statistics presented: n (%).

Statistical tests performed: chi-square test of independence.

In multivariate analysis (Table 3 ), being a man (OR = 0.54, 95% CI [0.48; 0.60], p < 0.001) and not living alone (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.62; 0.82], p < 0.001), are associated with a reduced risk of psychological distress. The older you are, the less risk of psychological distress you have, compared to 19–21 years old students: 22–24 years (OR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.71; 0.91], p = 0.001), 25–27 years (OR = 0.62, 95% CI [0.53; 0.74], p < 0.001), 27 years and more (OR = 0.48, 95% CI [0.42; 0.54], p < 0.001). Not having the ability to isolate (OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.39; 1.81], p < 0.001), and having low (OR = 2.31, 95% CI [2.08; 2.56], p < 0.001) or important (OR = 4.58, 95% CI [3.98; 5.29], p < 0.001) financial difficulties are associated with an increased risk of psychological distress.

Table 3.

Logistic regression with socio-demographic data using Kessler scale (presence (≥13) or absence of psychological distress), as a dependent variable.

| Characteristic | K6 |

OR (univariable) | OR (multivariable) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0, N = 27371 | 1, N = 14,4031 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 2089 (15%) | 12,256 (85%) | – | – |

| Men | 610 (24%) | 1908 (76%) | 0.53 (0.48–0.59, p < 0.001) | 0.54 (0.48–0.60, p < 0.001) |

| Age | ||||

| 19–21 | 877 (13%) | 5942 (87%) | – | – |

| 22–24 | 739 (14%) | 4376 (86%) | 0.87 (0.79–0.97, p = 0.012) | 0.80 (0.71–0.91, p = 0.001) |

| 25–27 | 325 (19%) | 1370 (81%) | 0.62 (0.54–0.72, p < 0.001) | 0.62 (0.53–0.74, p < 0.001) |

| 27 years and more | 796 (23%) | 2715 (77%) | 0.50 (0.45–0.56, p < 0.001) | 0.48 (0.42–0.54, p < 0.001) |

| Live alone | ||||

| Yes | 338 (13%) | 2226 (87%) | – | – |

| No | 2323 (16%) | 11,787 (84%) | 0.77 (0.68–0.87, p < 0.001) | 0.71 (0.62–0.82, p < 0.001) |

| Subjective financial difficulties | ||||

| No | 1275 (26%) | 3623 (74%) | – | – |

| Moderate | 859 (14%) | 5483 (86%) | 2.25 (2.04–2.47, p < 0.001) | 2.31 (2.08–2.56, p < 0.001) |

| High | 344 (7.7%) | 4119 (92%) | 4.21 (3.71–4.79, p < 0.001) | 4.58 (3.98–5.29, p < 0.001) |

| Ability to isolate | ||||

| Yes | 2161 (17%) | 10,476 (83%) | – | – |

| No | 366 (11%) | 2850 (89%) | 1.61 (1.43–1.81, p < 0.001) | 1.58 (1.39–1.81, p < 0.001) |

| Specialty | ||||

| Nurse | 1414 (15%) | 7793 (85%) | – | – |

| Medicine | 521 (20%) | 2102 (80%) | 0.73 (0.66–0.82, p < 0.001) | 1.31 (1.15–1.51, p < 0.001) |

| Dental-pharmacy-midwife | 323 (14%) | 1905 (86%) | 1.07 (0.94–1.22, p = 0.310) | 1.58 (1.36–1.84, p < 0.001) |

| Others | 356 (17%) | 1743 (83%) | 0.89 (0.78–1.01, p = 0.068) | 1.19 (1.03–1.38, p = 0.019) |

| PASS | 96 (12%) | 684 (88%) | 1.29 (1.04–1.62, p = 0.023) | 1.62 (1.27–2.10, p < 0.001) |

1 Statistics presented: n (%).

Significative Odd Ratio (p<0.05).

Compared to nurse students, in univariate analysis, medical students have a decreased risk (OR = 0.73, 95% CI [0.66; 0.82], p < 0.001) and PASS students an increased risk (OR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.04; 1.62], p = 0.023) of psychological distress. In multivariate analysis, all health student had an increased risk of psychological distress compared to nurses students: medical (OR = 1.31, 95% CI [1.15; 1.51], p < 0.001), dental-pharmacist-midwife (OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.36; 1.84], p < 0.001), PASS (OR = 1.62, 95% CI [1.27; 2.10], p < 0.001) and others health students (OR = 1.19, 95% CI [1.03; 1.39], p = 0.019).

3.3. Distress, social support, information, and drugs

According to their answers to numeric scales, half of the health students have moderate to high distress levels (51%), low need for support (49%) and one on five substance use (21%), and psychotropic treatments use (18%), which is high compared to 18–25 years old general population (5.1%) (“Enquête nationale sur l'épidémie du Covid-19”, n.d.). PASS students have the highest need for support prevalence (moderate 38% and high 20%), and psychotropic treatments use prevalence (23%). Nurse students have the highest prevalence of substance use (23%) (Supplementary Table 2). However, they are not validated scales, and comparisons with other studies should be cautious.

3.4. Dropping out thoughts

Dropping thoughts were present in 15.5% of the students.

In multivariate analysis, having moderate (OR = 1.44, 95% CI [1.27; 1.64], p < 0.001) or high (OR = 2.39, 95% CI [2.09; 2.73], p < 0.001) subjective financial difficulties, not having the ability to isolate (OR = 1.62, 95% CI [1.45; 1.80], p < 0.001) and having psychological distress (OR = 8.86, 95% CI [6.65; 12.12], p < 0.001), are associated with an increased risk of dropping out thoughts and not living alone with a decrease risk (OR = 0.78, 95% CI [0.69; 0.89], p < 0.001). Compared to nurse, being a PASS student (OR = 1.75, 95% CI [1.41; 2.16], p < 0.001) is associated with an increased risk of dropping out thoughts whereas being in other specialties is associated with a decreased (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.69; 0.95], p = 0.008).

In univariate analysis only, being older than 21 was associated with a decreased risk of dropping thoughts (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Logistic regression with socio-demographic data and Kessler scale (presence of psychological distress (≥13) using dropping out thought), as a dependent variable.

| Drop out thoughts |

OR (univariable) | OR (multivariable) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, N = 14,3211 | Yes, N = 26251 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 11,983 (84%) | 2200 (16%) | – | – |

| Men | 2127 (85%) | 368 (15%) | 0.94 (0.84–1.06, p = 0.331) | 1.04 (0.91–1.19, p = 0.571) |

| Age | ||||

| 19–21 | 5623 (83%) | 1123 (17%) | – | – |

| 22–24 | 4297 (85%) | 768 (15%) | 0.89 (0.81–0.99, p = 0.030) | 0.92 (0.82–1.03, p = 0.156) |

| 25–27 | 1452 (86%) | 227 (14%) | 0.78 (0.67–0.91, p = 0.002) | 0.89 (0.74–1.06, p = 0.181) |

| 27 years and more | 2949 (85%) | 507 (15%) | 0.86 (0.77–0.96, p = 0.010) | 0.93 (0.82–1.06, p = 0.283) |

| Live alone | ||||

| Yes | 2073 (82%) | 466 (18%) | – | – |

| No | 11,876 (85%) | 2076 (15%) | 0.78 (0.70–0.87, p < 0.001) | 0.78 (0.69–0.89, p < 0.001) |

| Subjective financial difficulties | ||||

| No | 4416 (91%) | 446 (9.2%) | – | – |

| Moderate | 5373 (85%) | 915 (15%) | 1.69 (1.50–1.90, p < 0.001) | 1.44 (1.27–1.64, p < 0.001) |

| High | 3348 (76%) | 1057 (24%) | 3.13 (2.78–3.53, p < 0.001) | 2.39 (2.09–2.73, p < 0.001) |

| Ability to isolate | ||||

| Yes | 10,769 (86%) | 1740 (14%) | – | – |

| No | 2472 (78%) | 712 (22%) | 1.78 (1.62–1.96, p < 0.001) | 1.62 (1.45–1.80, p < 0.001) |

| Specialty | ||||

| Nurse | 7567 (83%) | 1530 (17%) | – | – |

| Medicine | 2283 (88%) | 325 (12%) | 0.70 (0.62–0.80, p < 0.001) | 0.98 (0.84–1.14, p = 0.788) |

| Dental-pharmacy-midwife | 1903 (86%) | 304 (14%) | 0.79 (0.69–0.90, p = 0.001) | 0.97 (0.83–1.13, p = 0.679) |

| Others | 1805 (87%) | 260 (13%) | 0.71 (0.62–0.82, p < 0.001) | 0.81 (0.69–0.95, p = 0.008) |

| PASS | 600 (78%) | 172 (22%) | 1.42 (1.18–1.69, p < 0.001) | 1.75 (1.41–2.16, p < 0.001) |

| Psychological distress | ||||

| Non | 2650 (98%) | 61 (2.3%) | – | – |

| Yes | 11,671 (82%) | 2564 (18%) | 9.54 (7.45–12.48, p < 0.001) | 8.86 (6.65–12.12, p < 0.001) |

1 Statistics presented: n (%).

Significative Odd Ratio (p<0.05).

4. Discussion

Compared to the first survey (Rolland et al., 2022), we obtained 4-fold more participants (4411 versus 16,937). We noticed mental health deterioration. Psychological distress' prevalence hugely increased: 85% have a high level (score ≥ 13 versus 21%) on the K6. Kessler 6 scale was also used in China during the first wave: 37% of medical staff and medical students were at high risk of serious mental illness (score ≥ 13) (Wu et al., 2020).

Substance use increased from 13% to 21%, and psychotropic treatment use from 7.3% to 18%. There is also an increased need for support (51% vs 33.5%) with a similar support information level. Sleep quality stayed similar, with only 30% having a high quality of sleep.

In agreement with the literature, women (Dumitrache et al., 2021) and younger students (Shanahan et al., 2020) have an increased risk of psychological distress. Financial difficulties are the major risk factor for psychological distress in our study (OR = 4.58 for important difficulties), consistent with previous data (Rajapuram et al., 2020). Only 31% of the students said they don't have financial difficulties. There are significant discrepancies between students: 21% of nurse students have no financial difficulties vs 55% of medical students. It could partially explain why nurse students have less psychological distress in multivariate analysis that adjusts for financial difficulties than other health students. Age is another potential explanation: 46% of nurse students are 19–21 years old versus 18% of medical students and 24% of dental-pharmacist-midwife students.

4.1. Dropping out thoughts in health students

Association between poor mental health and increased risk of dropping out was previously found in the general student population (Hjorth et al., 2016). Dropping out is a well-known problem in health studies. In UK nurse students, the non-completion rate was between 7.6% in Northern Ireland and 26.8% in England in 2016 (Jones-Berry, 2017, p.). In US medical students, searchers found: “Each one-point increase in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization score and one-point decrease in personal accomplishment score at baseline was associated with a 7% increase in the odds of serious thoughts of dropping out during the following year” (Dyrbye et al., 2010). There is no available data in France. Mental health isn't the only dropping out reason (Ahmady et al., 2019).

4.2. Support for health students

Before the pandemic, there were already many studies regarding preventive actions targeting depression, anxiety, and stress in university students (Rith-Najarian et al., 2019).

In US medical schools, wellbeing was already important, and they offer their students activities for emotional/spiritual, physical, financial, and social wellness (Dyrbye et al., 2019). They also developed mentorship to improve the life quality of students (Farkas et al., 2019). Furthermore, some universities also made institutional adjustments to improve mental health: change to pass/fail to grade in the first two years, 10% reduction of required curricular time, efforts to reduce the amount of detail taught, implementation of a three-hour resilience and mindfulness curriculum and of a confidential option for tracking depression and anxiety (Slavin and Chibnall, 2016).

Since the pandemic's beginning, doctors have alerted the importance of including medical students in mental health support (Saeki and Shimato, 2021). A systematic review found 10 studies about student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic with 2 main themes: academic support and mental health support (Ardekani et al., 2021). Because of the pandemic, new solutions had to be found. In the UK, senior medical students helped first-year medical students (Nelson-Rowe, 2021).

Because of the pandemic, classes were online. A Poland study on medical students found that online education requires more self-directed learning, which was challenging for many students: 57.9% considered this impact negative, and 49.2% reported online examinations were more stressful (Pokryszko-Dragan et al., 2021).

In Canada, they adopted in October 2020 a “National Standard for Mental Health and Well-Being for Post-Secondary Students” (“National Standard for Mental Health and Well-Being for Post-Secondary Students | Mental Health Commission of Canada”, n.d.). Even in this country which has been very active for the welfare of students for a long time, 83% of medical students reported their studies as a significant source of stress (Wilkes et al., 2019). It highlights the difficulties to deal with this problem, the impact that studies can have on the wellbeing of health students, and the need for specific actions.

4.3. French situation

In France, before the pandemic, there were few things compared to other countries. Following Donata Marra 2018 official report (DICOM_Jocelyne.M and DICOM_Jocelyne.M, 2020), the French Ministers of Health and University and Research have made 15 commitments to the wellbeing of health students, still relevant, including the creation of the Center for the Quality of Life of Health Students (Centre National d'Appui, CNA) (CAB_Solidarites and CAB_Solidarites, 2021). For two years, the CNA conducted several surveys on student wellbeing (“Covid-19”, 2020); trained health students and teachers to improve quality of life (“Qualité de vie des étudiants en santé”, 2019); helped health universities and schools to implement local support actions for health students (l'Innovation, n.d.), and created a phone line to support them (“Plateforme | CNA Santé”, n.d.).

Since the pandemic's beginning, different other actions have been implemented. For instance, for financial difficulties, the government has offered students the opportunity to buy meals for €1 in university cafeterias twice a day (“Des aides pour les étudiants en difficulté face à la crise sanitaire”, n.d.). A website with all psychological supports available was created (“Les services de soutien psychologique étudiant”, n.d.). Free psychological support was officially proposed (“Santé Psy Étudiant”, n.d.), but in practice, not enough students had access to it: the payment of the session is considered insufficient by the psychologists, so few of them have agreed to participate, and the process of gaining access is long and complex (““Chèques psy” pour les étudiants”, 2021).

Before the pandemic, there were already proposals to improve medical (Frajerman, 2020) and health students' wellbeing (DICOM_Jocelyne.M and DICOM_Jocelyne.M, 2020). The 4-fold increase in the percentage of students with high psychological stress far exceeds the recent rise in anxiety and depressive disorders due to the pandemic (COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2021). Considering the international aspect of the problem, international recommendations from experience sharing should be proposed with financial plans at the height of the problem and supported at the highest level of the state.

Quebec, for example, announced a $60 million plan over 5 years for students' mental health (“Plan d'action pour la santé mentale étudiante en enseignement supérieur 2021–2026”, n.d.).

This study encouraged an increase in financial and human resources to improve the wellbeing of health students. It provides a benchmark for future studies evaluating the impact of interventions on the mental health of health students.

4.4. Strengths and limits

Even if there are more than 16,000 subjects, the response rate stays low regarding the target population (300,000 health students). However, it remains superior to a national study on students (5.6% vs 4.3%) (Wathelet et al., 2020). Because it's an anonymous cross-sectional study, we can't know if students who answered in the first survey also answered this time. There is an overrepresentation of nurses who represent more than half of the subjects. However, nurses students also represented more than half of health students after excluded medical students (“Les étudiants en formation de santé en 2017 et 2018 | Direction de la recherche, des études, de l'évaluation et des statistiques”, n.d.). There were also many women among the study participants but representative of the national proportion. Indeed, in older French data: “83% of the students enrolled in an institution training for a non-medical health profession were women” (“Les étudiants en formation de santé en 2017 et 2018 | Direction de la recherche, des études, de l'évaluation et des statistiques”, n.d.). This is important because women had higher levels of distress than men in this study. It is also plausible that a higher level of pain was an incentive to participate in the study. The use of online questionnaires raises the question of the representativeness of the sample (in particular because of the possibility of having access to the internet). According to a French national survey during the pandemic, 92% of students reported having a computer or tablet for personal use, but only 64% had a good internet connection (“La vie d'étudiant·e confiné·e”, n.d.). Therefore, there is a possible socio-economic bias as responding to this survey required an internet connection. Furthermore, according to another study “individuals with existing or severe mental illness are less likely to participate online than those without such conditions” (Pierce et al., 2020). However, using the same questionnaire allows us to compare and notice a deterioration in mental health. Furthermore, this is the only study that includes all health students and looks at psychological distress to have an overview of mental health, rather than a specific psychiatric illness (Morvan and Frajerman, 2021) and its impact on student motivation.

5. Conclusion

After one year of pandemic, this third national survey on health students found mental health degradation. Even if there are differences regarding specialities, 4 students over 5 had a high level of psychological distress. Financial difficulties increased 4-fold risk of psychological distress. Younger students and women are more impacted. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest national study on health students' mental health and the first study during the third wave. Despite support actions already in place, mental health deterioration is an indication there is an urgent need for increased efforts to support health students.

Funding

The study was supported by Center for the Quality of Life of Health Students (Centre National d'Appui à la qualité de vie des étudiants en santé, CNA) and the Research Center in Epidemiology and Population Health (Centre de recherche en Epidémiologie et Santé des Populations, CESP).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A Frajerman: statistical analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing

Franck Rolland, Gilles Bertschy, Bertrand Diquet, Bruno Falissard and Donata Marra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Data curation, Investigation, review & editing

Donata Marra: Supervision

Conflict of interest

Franck Rolland, Gilles Bertschy, Bertrand Diquet, and Donata Marra are members of the executive committee of the National Support Center for the Quality of Life of Health Students.

Acknowledgements

All health students and their representative associations (ANEMF, ANEP, ANEPF, ANESF, FFEO, FNEK, FNEO, FNESI, FNSIP-BM, ISNAR-IMG, ISNI, UNAEE, UNECD, FAGE, FNEA).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.05.087.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ahmady S., Khajeali N., Sharifi F., Mirmoghtadaei Z.S. Factors related to academic failure in preclinical medical education: a systematic review. J. Adv. Med. Educ. Prof. 2019;7:74–85. doi: 10.30476/JAMP.2019.44711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani A., Hosseini S.A., Tabari P., Rahimian Z., Feili A., Amini M., Mani A. Student support systems for undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic narrative review of the literature. BMC Med. Educ. 2021;21:352. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay E., Cariou A., Bruneel F., Demoule A., Kouatchet A., Reuter D., Klouche K., Argaud L., Barbier F., Jourdain M., Reignier J., Papazian L., Resche-Rigon M., Guisset O., Labbé V., Van Der Meersch G., Guitton C. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care clinicians facing the COVID-19 second wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAB_Solidarites. CAB_Solidarites 15 mesures pour le bien-être des étudiants en santé [WWW Document]. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2021. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/actualites/presse/dossiers-de-presse/article/15-mesures-pour-le-bien-etre-des-etudiants-en-sante (accessed 10.26.21)

- "Chèques psy" pour les étudiants: le dispositif peine à convaincre WWW Document. 2021. https://www.rfi.fr/fr/france/20210523-ch%C3%A8ques-psy-pour-les-%C3%A9tudiants-le-dispositif-peine-%C3%A0-convaincre RFI. (accessed 9.1.21)

- Cotton S.M., Menssink J., Filia K., Rickwood D., Hickie I.B., Hamilton M., Hetrick S., Parker A., Herrman H., McGorry P.D., Gao C. The psychometric characteristics of the kessler psychological distress scale (K6) in help-seeking youth: what do you miss when using it as an outcome measure? Psychiatry Res. 2021;114182 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. S0140-6736(21)02143–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covid-19: un étudiant en santé sur deux en détresse psychologique What's Up Doc. 2020. https://www.whatsupdoc-lemag.fr/article/covid-19-un-etudiant-en-sante-sur-deux-en-detresse-psychologique (accessed 10.26.21)

- Deng J., Zhou F., Hou W., Silver Z., Wong C.Y., Chang O., Drakos A., Zuo Q.K., Huang E. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des aides pour les étudiants en difficulté face à la crise sanitaire [WWW document] https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/actualites/A14614 n.d. URL.

- DICOM_Jocelyne.M. DICOM_Jocelyne.M Rapport du Dr Donata Marra sur la Qualité de vie des étudiants en santé [WWW Document]. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé. 2020. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/ministere/documentation-et-publications-officielles/rapports/sante/article/rapport-du-dr-donata-marra-sur-la-qualite-de-vie-des-etudiants-en-sante (accessed 3.12.20)

- Dumitrache L., Stănculescu E., Nae M., Dumbrăveanu D., Simion G., Taloș A.M., Mareci A. Post-lockdown effects on students' mental health in Romania: perceived stress, missing daily social interactions, and boredom proneness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:8599. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye L.N., Sciolla A.F., Dekhtyar M., Rajasekaran S., Allgood J.A., Rea M., Knight A.P., Haywood A., Smith S., Stephens M.B. Medical school strategies to address student well-being: a national survey. Acad. Med. 2019;94:861–868. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye L.N., Thomas M.R., Power D.V., Durning S., Moutier C., Massie F.S., Harper W., Eacker A., Szydlo D.W., Sloan J.A., Shanafelt T.D. Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: a multi-institutional study. Acad. Med. 2010;85:94–102. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46aad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquête nationale sur l’épidémie du Covid-19. https://www.epicov.fr/ n.d. URL. (accessed 3.28.22)

- Enquête sur la santé psychologique étudiante : quand la parole rejoint la théorie | Acfas [WWW document] https://www.acfas.ca/publications/magazine/2016/12/enquete-sante-psychologique-etudiante-quand-parole-rejoint-theorie n.d. URL.

- Farkas A.H., Allenbaugh J., Bonifacino E., Turner R., Corbelli J.A. Mentorship of US medical students: a systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019;34:2602–2609. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05256-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frajerman A. Which interventions improve the well-being of medical students? A review of the literature. Encéphale. 2020;46:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T.A., Kessler R.C., Slade T., Andrews G. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of mental health and well-being. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:357–362. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Official Legal Text [WWW Document], General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) https://gdpr-info.eu/ n.d. URL. (accessed 3.25.22)

- Hakami Z., Vishwanathaiah S., Abuzinadah S.H., Alhaddad A.J., Bokhari A.M., Marghalani H.Y.A., Shahin S.Y. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on the mental health of dental students: a longitudinal study. J. Dent. Educ. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jdd.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth C.F., Bilgrav L., Frandsen L.S., Overgaard C., Torp-Pedersen C., Nielsen B., Bøggild H. Mental health and school dropout across educational levels and genders: a 4.8-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:976. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institut national de, santé publique du Québec Fiche 11 - Kessler Psychological Distress Scale– 6 items (K6) [WWW Document]. INSPQ. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/boite-outils-pour-la-surveillance-post-sinistre-des-impacts-sur-la-sante-mentale/instruments-de-mesure-standardises/fiches-pour-les-instruments-de-mesure-standardises-recommandes/detresse-psychologique n.d. URL. (accessed 3.25.22)

- Joint Statement - COVID-19 impact likely to lead to increased rates of suicide and mental illness Australian Medical Association. 2020. https://www.ama.com.au/media/joint-statement-covid-19-impact-likely-lead-increased-rates-suicide-and-mental-illness (accessed 6.28.21)

- Jones-Berry S. Student drop-out rates put profession at further risk. Nurs. Stand. 2017;32:12–13. doi: 10.7748/ns.32.2.12.s13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Green J.G., Gruber M.J., Sampson N.A., Bromet E., Cuitan M., Furukawa T.A., Gureje O., Hinkov H., Hu C.-Y., Lara C., Lee S., Mneimneh Z., Myer L., Oakley-Browne M., Posada-Villa J., Sagar R., Viana M.C., Zaslavsky A.M. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2010;19:4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- l’Innovation, M. de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de Lancement du Centre national d’appui à la qualité de vie des étudiants en santé [WWW Document]. Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation. https://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/cid143914/lancement-du-centre-national-d-appui-a-la-qualite-de-vie-des-etudiants-en-sante.html n.d. URL. (accessed 10.26.21)

- La vie d’étudiant·e confiné·e OVE: Observatoire de la vie Étudiante. http://www.ove-national.education.fr/enquete/la-vie-detudiant-confine/ URL. n.d.

- Les études de santé [WWW Document], Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation. https://www.enseignementsup-recherche.gouv.fr/pid25335/etudes-de-sante.html n.d. URL. (accessed 8.31.21)

- Les étudiants en formation de santé en 2017 et 2018 | Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques [WWW document] https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/communique-de-presse/les-etudiants-en-formation-de-sante-en-2017-et-2018 n.d. URL. (accessed 10.31.21)

- Les services de soutien psychologique étudiant [WWW Document], Soutien Etudiant. https://www.soutien-etudiant.info/services-soutien n.d. URL. (accessed 3.2.21)

- Marleau J., Turgeon S., Turgeon J. The kessler abbreviated psychological distress scale (K6) in Canadian population surveys : report on psychometric assessment practices and analysis of the performance of several reliability coefficients. Rev. Epidemiol. Sante Publique. 2022;70:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhemar M., Attia S., Dörfer C., Conrad J. Dental students in Germany throughout the COVID-19 pandemic: a psychological assessment and cross-sectional survey. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:611. doi: 10.3390/biology10070611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morvan Y., Frajerman A. La santé mentale des étudiants : mieux prendre la mesure et considérer les enjeux. L'Encéphale. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Standard for Mental Health and Well-Being for Post-Secondary Students | Mental Health Commission of Canada [WWW Document] https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/studentstandard n.d. URL. (accessed 8.24.21)

- Nelson-Rowe E.L. Filling in the blanks: senior medical student supporting the transition of incoming first-year UK medical students during COVID-19. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021;1–4 doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01361-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolis L., Wakim A., Adams W., Do P.B. Medical student wellness in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2021;21:401. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02837-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OVE Infos n°43 | Student life in 2020: uncertainty and vulnerability, OVE: Observatoire de la vie Étudiante. http://www.ove-national.education.fr/publication/ove-infos-n43-student-life-in-2020-uncertainty-and-vulnerability/ n.d. URL. (accessed 8.31.21)

- Pierce M., McManus S., Jessop C., John A., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S., Wessely S., Abel K.M. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plan d’action pour la santé mentale étudiante en enseignement supérieur 2021–2026 [WWW document] https://www.quebec.ca/gouv/politiques-orientations/plan-action-sante-mentale-des-etudiants n.d. URL. (accessed 9.20.21)

- Plateforme | CNA Santé [WWW Document] https://cna-sante.fr/plateforme n.d. URL.

- Pokryszko-Dragan A., Marschollek K., Nowakowska-Kotas M., Aitken G. What can we learn from the online learning experiences of medical students in Poland during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic? BMC Med. Educ. 2021;21:450. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02884-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualité de vie des étudiants en santé: un centre d’appui voit le jour What's Up Doc. 2019. https://www.whatsupdoc-lemag.fr/article/qualite-de-vie-des-etudiants-en-sante-un-centre-dappui-voit-le-jour (accessed 10.26.21)

- Rajapuram N., Langness S., Marshall M.R., Sammann A. Medical students in distress: the impact of gender, race, debt, and disability. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rith-Najarian L.R., Boustani M.M., Chorpita B.F. A systematic review of prevention programs targeting depression, anxiety, and stress in university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;257:568–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F., Frajerman A., Falissard B., Bertschy G., Diquet B., Marra D. Impact of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic on french health students. L'Encéphale. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2021.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux J., Lefort M., Bertin M., Padilla C., Mueller J., Garlantézec R., Pivette M., Tertre A.L., Crepey P. 2021. Impact de la crise sanitaire de la COVID-19 sur la santé mentale des étudiants à Rennes, France. [Google Scholar]

- Saeki S., Shimato M. Mental health support for the current and future medical professionals during pandemics. JMA J. 2021;4:281–283. doi: 10.31662/jmaj.2021-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santé Psy Étudiant: un site pour un suivi psychologique gratuit des étudiants [WWW Document] https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/actualites/A14726 n.d. URL.

- Schmits E., Dekeyser S., Klein O., Luminet O., Yzerbyt V., Glowacz F. Psychological distress among students in higher education: one year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:7445. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan L., Steinhoff A., Bechtiger L., Murray A.L., Nivette A., Hepp U., Ribeaud D., Eisner M. Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2020;1–10 doi: 10.1017/S003329172000241X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon E., Simmonds-Buckley M., Bone C., Mascarenhas T., Chan N., Wincott M., Gleeson H., Sow K., Hind D., Barkham M. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;287:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin S.J., Chibnall J.T. Finding the why, changing the how: improving the mental health of medical students, residents, and physicians. Acad. Med. 2016;91:1194–1196. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sveinsdóttir H., Flygenring B.G., Svavarsdóttir M.H., Thorsteinsson H.S., Kristófersson G.K., Bernharðsdóttir J., Svavarsdóttir E.K. Predictors of university nursing students burnout at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today. 2021;106 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathelet M., Duhem S., Vaiva G., Baubet T., Habran E., Veerapa E., Debien C., Molenda S., Horn M., Grandgenèvre P., Notredame C.-E., D’Hondt F. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes C., Lewis T., Brager N., Bulloch A., MacMaster F., Paget M., Holm J., Farrell S.M., Ventriglio A. Wellbeing and mental health amongst medical students in Canada. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2019;31:584–587. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2019.1675927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S., Li Zhe, Li Zhixiong, Xiang W., Yuan Y., Liu Y., Xiong Z. The mental state and risk factors of chinese medical staff and medical students in early stages of the COVID-19 epidemic. Compr. Psychiatry. 2020;102 doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material