Key Points

Question

What is the Danish nationwide incidence of thyroid eye disease (TED) and the cumulative incidence of strabismus and surgical interventions in TED?

Findings

In this cohort study in Denmark, the mean annual incidence of TED from 2000 to 2018 was 5.0 per 100 000 person-years overall and higher in women, with a 4:1 ratio of women to men with TED. The 4-year cumulative incidence was 10% for strabismus, 8% for strabismus surgery, and 5% for orbital decompression in patients with TED.

Meaning

These results provide empirical incidence in Denmark of TED and strabismus and surgical interventions after TED that could be used to inform patients and implement preventive health care strategies.

This cohort study examines registry-based data from Denmark to assess the nationwide incidence of thyroid eye disease and subsequent outcomes and surgical interventions.

Abstract

Importance

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a serious condition that can cause proptosis and strabismus and, in rare cases, lead to blindness. Incidence data for TED and strabismus and surgical interventions after TED are sparce.

Objective

To investigate the nationwide incidence of TED, strabismus, and surgical interventions associated with TED.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study between 2000, which marks the beginning of uniform coding for the decompression surgery nationwide, and 2018. The cohort consisted of a mean 4.3 million people aged 18 to 100 years with no prior TED diagnosis each year. Total observation time was 8.22 × 107 person-years (women, 4.18 × 107 person-years; men, 4.04 × 107 person-years).

Main Outcome Measures

The annual numeric and age-standardized incidence of hospital-treated TED and cumulative incidence of strabismus, strabismus surgery, and orbital decompression surgery in patients with TED. The incidence was stratified by sex, thyroid diagnosis, and age.

Results

A total of 4106 incident diagnoses of TED were identified during 19 years among 3344 women (81.4%) and 762 men (18.6%). The mean numeric annual nationwide incidence rate of TED was 5.0 per 100 000 person-years overall, 8.0 per 100 000 person-years in women, and 1.9 per 100 000 person-years in men, resulting in a 4:1 ratio of women to men with TED. The age-standardized incidence was similar. The mean (SD) age at onset was 51.3 (14.5) years. At the time of TED diagnosis, 611 patients (14.9%) were euthyroid, 477 (11.6%) were hypothyroid, and 3018 (73.5%) were hyperthyroid. In patients with TED who were euthyroid, the 4-year cumulative incidence was 41% for antithyroid medication and 13% for L-thyroxine. In patients with TED, the 4-year cumulative incidence for strabismus was 10%. The 4-year cumulative incidence of surgical interventions after TED was 8% for strabismus surgery and 5% for orbital decompression. At 4 years, strabismus surgery was more common in men (13.3%; 95% CI, 10.75-15.86) than in women (7.2%; 95% CI, 6.24-8.08), and the absolute difference was 6.1% (95% CI, 3.42-8.14; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study in Denmark provides nationwide empirical incidence of TED and strabismus and surgical interventions after TED that required inpatient or outpatient hospital treatment, and might be used for patient information and health care planning.

Introduction

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is a disfiguring and debilitating eye condition in 20% of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease.1 Thyroid eye disease occurs in patients with hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and euthyroidism and predominantly in women.2 In TED, the orbital content (primarily the eye muscles but also fat tissue) expands because of edema and inflammation. The condition can develop into several severe ophthalmological manifestations, such as proptosis, inflammation of the conjunctiva, keratitis, chemosis, periorbital edema, keratopathy, strabismus, and most seriously corneal melting or dysthyroid optic neuropathy, which can lead to blindness. Symptoms of TED not only cause patients daily physical discomfort but also have a negative effect on their mental health3 and quality of life.4

Mild TED symptoms improve with lubricating eye drops and with treatment of the underlying thyroid condition. Initially, moderate to severe TED symptoms can be treated with glucocorticoids but will require surgery if persistent and irreversible.5 Radiation of the orbit can be used as a second-line treatment together with glucocorticoids. Targeted biological therapies are expected to have a broader indication in the future.5,6 Strabismus surgery is performed in the chronic inactive and stable stage when a patient’s symptoms, such as diplopia, cannot be treated with other modalities.7

Decompression surgery is performed either as an acute procedure when vision is threatened because of optic nerve compression or as a rehabilitation procedure in the chronic phase and preferably before strabismus surgery. In Denmark, international guidelines were implemented and treatment centralized to 6 locations so that timely and necessary TED treatment is available to reduce long-term sequelae.8

The variation in reported incidence of TED in previous US and Scandinavian studies is most likely because of smaller selected patient populations (N = 120-447) from a single or few centers.1,2,9,10 The cumulative incidence of surgical interventions after TED was presented in only 1 previous US study with 120 patients.9

To provide a more reliable estimate of the incidence of TED, we performed a Danish nationwide study of all registered TED diagnoses from inpatient or outpatient treatment for individuals who were 18 to 100 years old between 2000 and 2018. In 2000, the National Patient Registry in Denmark began using uniform coding for decompression surgery. The study end date of 2018 means the most recently available data were included at the time of analysis. In addition, we investigated the cumulative incidence of a strabismus diagnosis, orbital decompression surgery, and strabismus surgery performed on patients with TED in the same time period to provide a realistic empirical estimate of the sequelae associated with the disease.

Methods

The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the use of the data for this study (reference number 2008-58-0028). Retrospective registry-based studies do not require approval from the research ethics committee system. This nationwide cohort study follows Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.11

The cohort comprised all Denmark residents aged 18 to 100 years from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2018 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). The Danish National Patient Registry contains discharge diagnoses from Danish hospitals from 1977 and onwards. Until 1994, the registry used codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Revision 8 (ICD-8); since 1995, the registry has used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).12

Information on date of birth, sex, demographics, and the vital status of the Danish population was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System and linked to the National Patient Registry via encrypted unique identifiers in Statistics Denmark.12,13 The population in any given year was defined to encompass all inhabitants who were alive on December 31 in the current year, at which time point their age and sex were extracted.

The first-time incidence of TED in adults was defined by a combination of recorded diagnosis in the Danish National Patient Registry and redeemed prescriptions in the National Register of Medicinal Product Statistics. Prevalent and repeated occurrences of TED dating from before the start of the study in 2000 had to be identified for exclusion. Both ICD-8 and ICD-10 codes were searched.

The main criteria for TED were either an ICD-10 diagnosis of “dysthyroid exophthalmos” or an ICD-8 diagnosis of either “morbus basedowi, struma diffusa toxica cum exophthalmos” or “exophthalmus malignus.” Thyroid eye disease was likewise considered to have occurred if an ICD-10 diagnosis of “exophthalmic conditions” or an ICD-8 diagnosis of “exophthalmus (sine thyreotoxicosi)” was preceded within 5 years by at least 2 redeemed prescriptions for either antithyroid drugs or L-thyroxine replacement therapy (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Only incident diagnoses occurring between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2018, were included. Incidence rates were calculated as both actual rates and as rates standardized to the age and sex distribution of the population in 2018. The starting point was chosen because of the beginning of uniform coding for decompression surgery nationwide, and the end point was chosen to include the most recent available data at the time of analysis.

The baseline case mix of incident cases by year in terms of thyroid status was determined from prescriptions redeemed within the 5 years preceding the diagnosis. Hyperthyroidism was defined by at least 1 redeemed prescription for antithyroid drugs (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] codes: HB03BA, HB03BA02, H03BB01, H03BB02) and hypothyroidism by at least 1 redeemed prescription for L-thyroxine therapy (ATC code: H03AA01) and no prescriptions for antithyroid medication (eTable 1 in the Supplement). If no prescriptions were redeemed, the person was considered euthyroid. Changes in the mean age of incident cases by year were analyzed by linear regression with the interaction between year and sex.

The postdiagnosis trajectory of people initially considered euthyroid was analyzed with cumulated incidence plots with death as a competing risk and with censoring at December 31, 2018. Redemption of a prescription of antithyroid medication or thyroid replacement therapy indicated that the person had become dysthyroid.

All cases were followed up to the occurrence of 1 of the TED sequelae studied or death or until December 31, 2018, whichever came first. The sequelae conditions were considered independently, but only the first occurrence of a specific outcome was considered. The sequelae studied were strabismus, strabismus surgery, and decompression surgery (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Analysis was conducted in R (R core team 2020),14 figures were produced using the package ggplot2,15 and the package cmprsk16 was used for analyses of competing risks. All P values were 2-sided, and there were no adjustments to P values for multiple analyses. The χ2 test was used to perform statistical analysis for changes in the proportion between sexes and in thyroid status over time. The Gray modified χ2 test was used for statistical analysis of changes between sexes in the cumulative incidence of strabismus, strabismus surgery, and decompression surgery.

Results

Between 2000 and 2018, a total of 21 967 TED diagnoses were recorded in the Danish National Patient registry. Of the 4106 patients with incident cases recorded in that period, 3344 (81.4%) were women and 762 (18.6%) were men (eTable 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). Thus, the sampling frame each year consisted of a mean of 4.3 million participants aged 18 to 100 years with no prior TED diagnosis. The population was examined for a total of 8.22 × 107 person-years overall (4.18 × 107 person-years in women and 4.04 × 107 person-years in men).

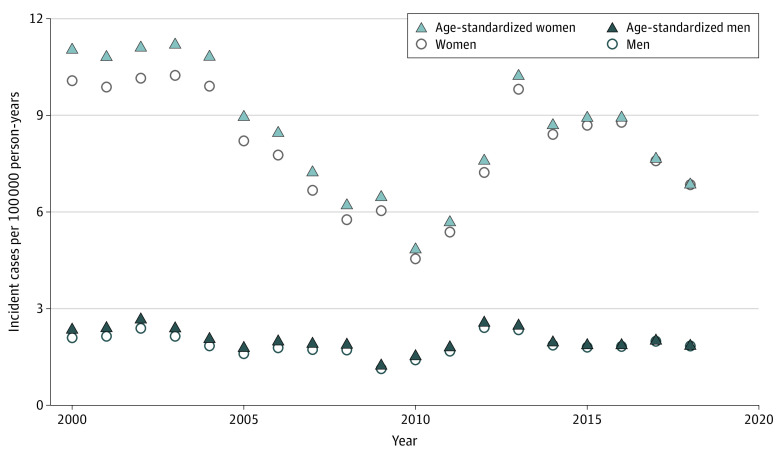

The mean annual nationwide incidence rate was 5.0 per 100 000 person-years overall, 8.0 per 100 000 person-years in women, and 1.9 per 100 000 person-years in men (Figure 1 and eTable 4 in the Supplement). The ratio of women to men with TED was 4:1 (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). There was no change in the distribution of the sexes across the time period studied (P = .11). The age-standardized incidence was similar (Figure 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). The incidence gradually decreased from 2005, with the lowest annual incidence rate at 3.0 per 100 000 person-years in 2010, and then increased until reaching a steady level between 2014 and 2018. The highest overall annual incidence rate was 6.4 per 100 000 person-years. The trend of decreasing incidence from 2004 to 2010 was seen in both sexes, albeit more in women than in men. The highest annual incidence rate was 10.2 in women and 2.4 in men per 100 000 person-years. The lowest annual incidence rate was 4.6 in women and 1.1 in men per 100 000 person-years (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age at onset was 51.3 (14.5) years overall, 51.1 (14.5) years in women, and 52.2 (14.5) years in men.

Figure 1. Incidence of Thyroid Eye Disease in Denmark (2000-2018).

The mean numerical incidence rate and age-standardized incidence rate were similar. The incidence in both sexes gradually decreased from 2005, with the lowest incidence rate in 2010, and then increased until reaching a steady level between 2014 and 2018. Women had a higher incidence of thyroid eye disease than men. Information on date of birth, sex, demographics, and vital status of the Danish population was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System and linked to the Danish National Patient Registry via encrypted unique identifiers in Statistics Denmark.

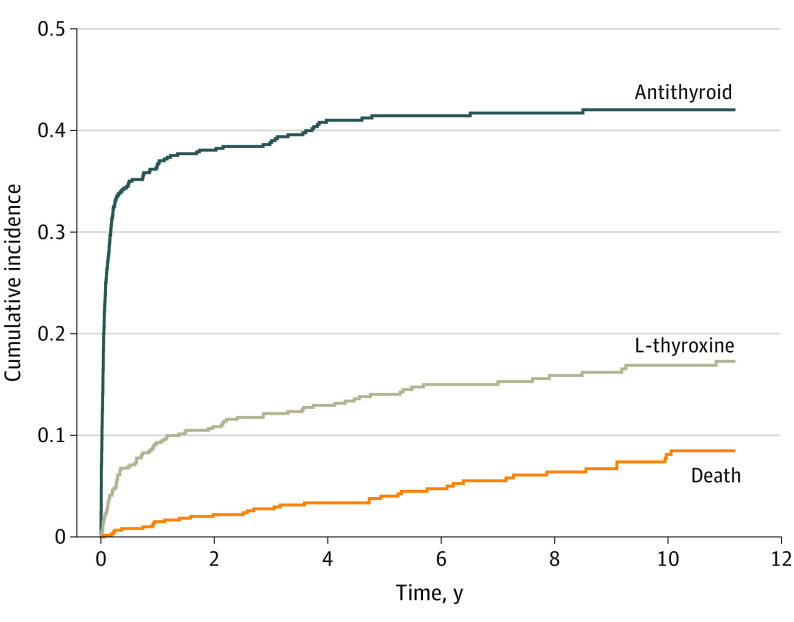

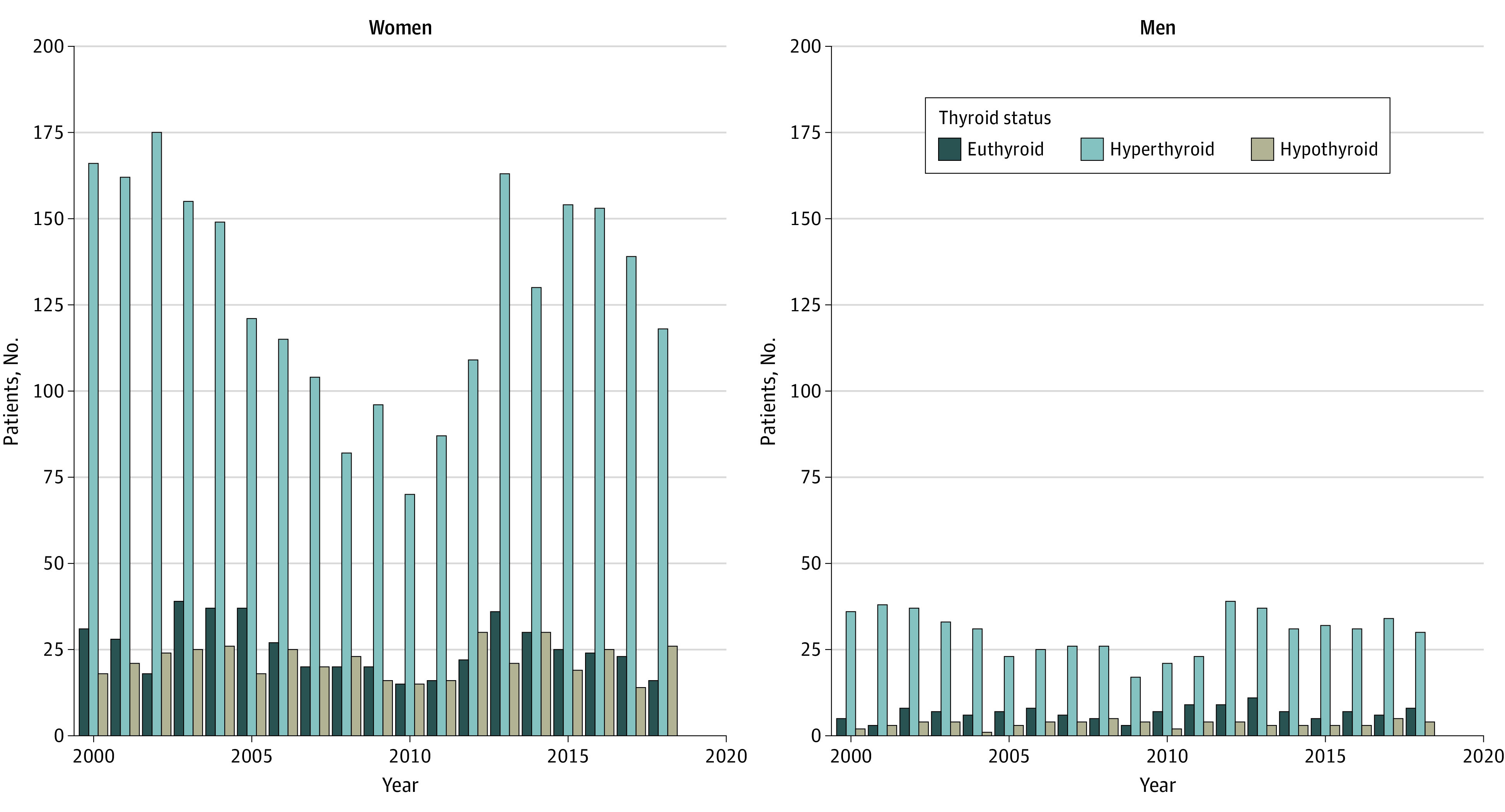

At the time of TED diagnosis, 611 patients (14.9%) were euthyroid, 477 (11.6%) were hypothyroid, and 3018 (73.5%) were hyperthyroid (Figure 2), yielding a ratio of euthyroid to hypothyroid to hyperthyroid status of 1:1:6. The proportion of patients who were hypothyroid or euthyroid did not change over the time period studied (P = .58 for euthyroid, P = .17 for hypothyroid). In patients who were euthyroid with TED, the cumulative incidence of prescriptions increased during the first years after diagnosis and then became stable. In this patient group, the 4-year cumulative incidence for redeeming a prescription was 41% for antithyroid medication and 13% for L-thyroxine (Figure 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Thyroid Status at Time of Thyroid Eye Disease Diagnosis in Denmark (2000-2018).

The majority of the patients diagnosed with thyroid eye disease were hyperthyroid. The thyroid status proportions did not change over the time studied in either men or women.

Figure 3. Cumulative Incidence of Patients Who Were Euthyroid Being Prescribed Thyroid Medication After Thyroid Eye Disease Diagnosis.

In this group of patients, there was an increase in prescriptions over the first 2 years after diagnosis, which then stabilized. The 4-year cumulative incidence for redeeming a prescription was 41% for antithyroid medication and 13% for L-thyroxine.

Strabismus and Surgical Interventions

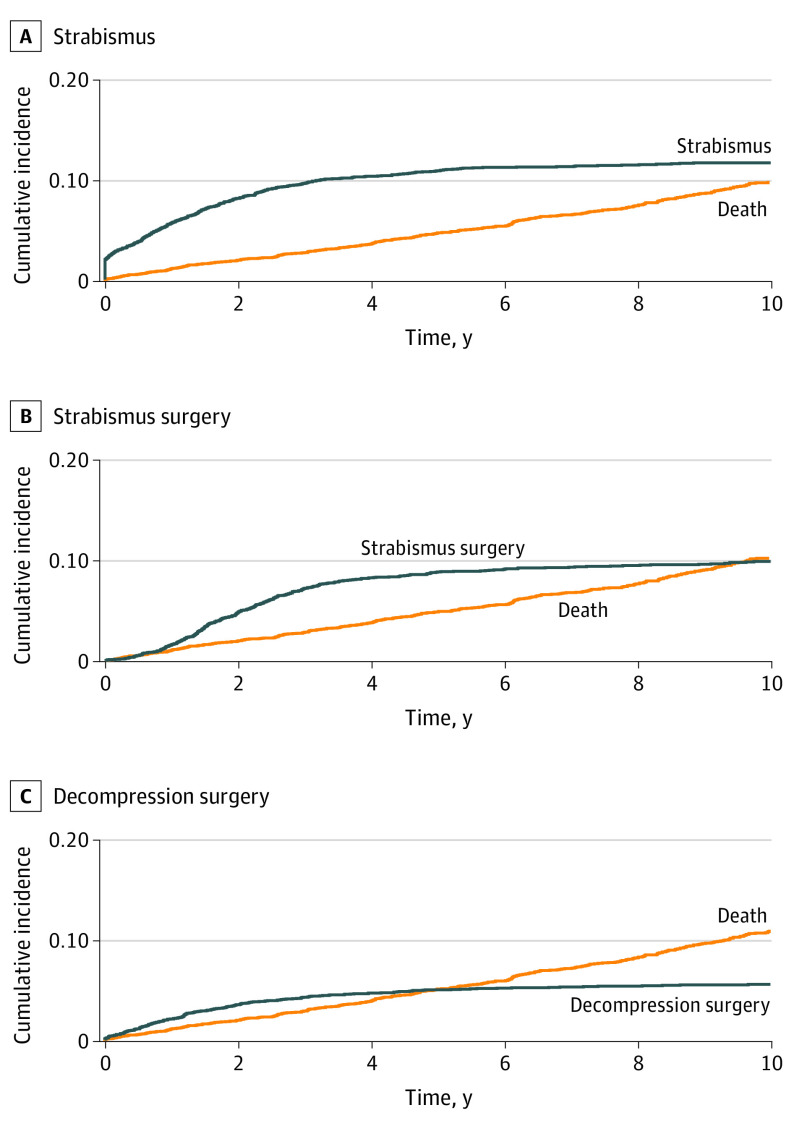

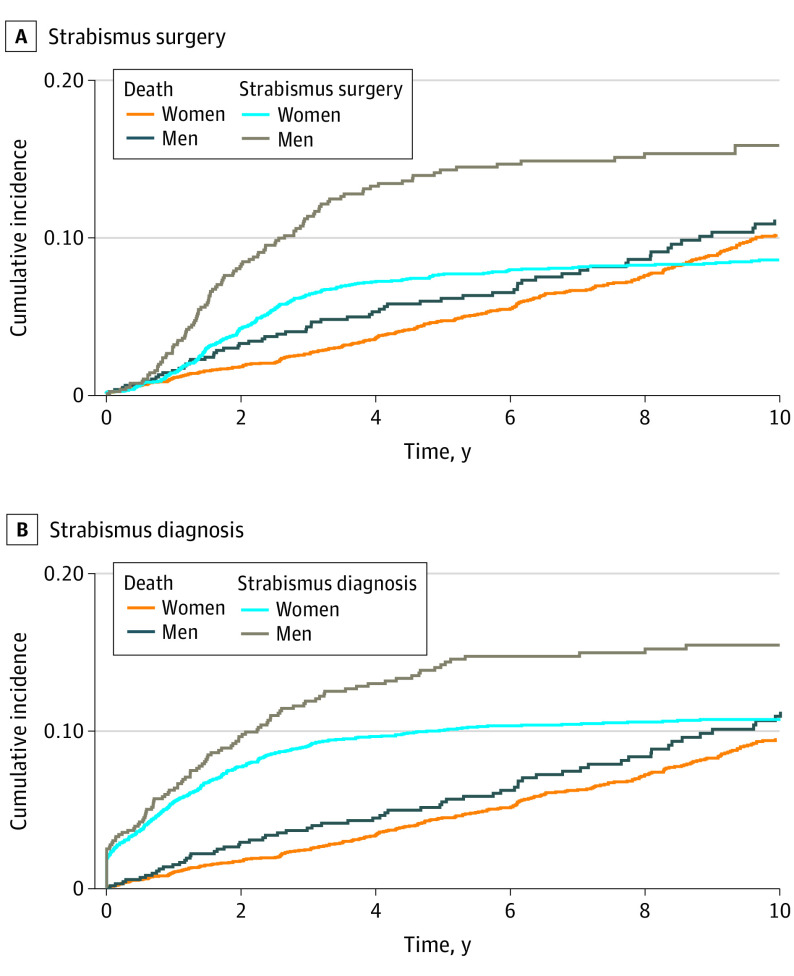

In patients with TED, the cumulative incidence of strabismus after TED increased to 10% during the first 4 years after diagnosis and then became stable at 12% (Figure 4 and eTable 6 in the Supplement). Over time, men had a higher cumulative incidence of strabismus than women. Thus, at 4 years, the cumulative incidence of strabismus in men was 13.1% (95% CI, 10.60%-15.58%) and in women, 9.7% (95% CI, 8.67%-10.73%), and the absolute difference was 3.4% (95% CI, 0.69%-5.37%; P = .001) (Figure 5 and eTable 7 in the Supplement). The cumulative incidence for strabismus surgery was 8% after 4 years and reached a maximum incidence of 10% after 8 years (Figure 4 and eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 4. Cumulative Incidence of Strabismus, Strabismus Surgery, or Orbital Decompression Surgery After Diagnosis of Thyroid Eye Disease.

The cumulative incidence of strabismus as an outcome of thyroid eye disease increased to 10% during the first 4 years after diagnosis and then became stable at 12%. The cumulative incidence of strabismus surgery was 8% after 4 years and reached a maximum incidence of 10% after 8 years. The cumulative incidence of decompression surgery was steady at 5% after 4 years.

Figure 5. Cumulative Incidence by Sex of Strabismus Surgery or Being Diagnosed With Strabismus After Thyroid Eye Disease Diagnosis.

There was a difference between the sexes in cumulative incidence of strabismus or strabismus surgery, with men having a higher incidence of either.

At 4 years, the cumulative incidence of strabismus surgery was greater in men (13.3%; 95% CI, 10.75%-15.86%) than in women (7.2%; 95% CI, 6.24%-8.08%), and the absolute difference was 6.1% (95% CI, 3.42%-8.14%; P < .001) (Figure 5 and eTables 9 in the Supplement). The cumulative incidence of decompression surgery reached a steady level of 5% after 4 years (Figure 4 and eTable 10 in the Supplement), and there was no difference in the incidence of this procedure between the sexes (eTable 11 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This nationwide study in Denmark evaluated TED and its associated conditions, wherein the mean annual incidence rate of TED was 5.0 per 100 000 person-years overall, 8.0 per 100 000 person-years in women, and 1.9 per 100 000 person-years in men. At the time of TED diagnosis, 6 times as many patients were hyperthyroid than either hypothyroid or euthyroid. Patients who were initially euthyroid were thrice as likely to become hyperthyroid than to become hypothyroid after 4 years. After a TED diagnosis, patients were twice as likely to be diagnosed with or undergo surgery for strabismus than to have orbital decompression surgery performed on them. While women developed TED 4 times more frequently than men, men were almost twice as likely to undergo strabismus surgery compared with women after TED diagnosis. Women and men were equally likely to undergo orbital decompression surgery.

The national mean annual TED incidence in our study was higher for both women and men than previously reported in other single and multicenter Scandinavian studies (2.7-3.3 per 100 000 person-years for women, 0.5-0.9 per 100 000 person-years for men).1,10,17 In contrast, it was lower than in a previous study from Minnesota (16/100 000 person-years in women and 2.9/100 000 person-years in men).9 In the only previous study of TED-associated sequelae, the 4-year cumulative incidence of strabismus surgery in 120 patients with incident TED from Minnesota was 5.2%,9 which was almost half of what we found (8%). In the same study, the 4-year cumulative incidence of orbital decompression surgery was 4.3%, which was comparable with our result of 5%. Previous studies have shown that when developing TED, the condition is more likely to advance into a severe and surgery-requiring form in men than in women.18,19,20 This was also supported by our study, in which men were more likely to develop strabismus and undergo strabismus surgery than women.

The likely reasons for the discrepancies in previous studies compared with ours could be that the patient population was selected in a way that fewer but more severe cases were included, resulting in a lower incidence, but also that the total population was either underestimated, leading to a higher incidence, or overestimated, leading to a lower incidence. Health care in Denmark is free. The clinical practice in Denmark is that all patients suspected of having TED are referred to a hospital for diagnosis and treatment. Therefore, our study included patients with TED ranging from mild to severe. The lower incidence in cumulative incidence of strabismus surgery in the US study from 19949 could be owing to a lower incentive to treat moderate TED cases if patient care depends on insurance. In all previous studies, the data for the statistical analyses were not as detailed as in this nationwide registry-based study.

We observed a wide cyclical fluctuation in the annual TED incidence during 2000 to 2018 in both women and men, but we can only speculate as to why. Compulsory iodinization of salt was introduced in Denmark in 2000, but the TED incidence did not change,10 although there was a transient increase and decrease in number of prescriptions for antithyroid medication.21 Smoking, which is an important risk factor for the development of TED and TED severity,2 has become less prevalent in Denmark over the past 19 years,22 likely due to national antismoking campaigns running from 2004 until 2008.23 This could possibly explain the parallel decrease in TED incidence in the same period. Because TED is an orbital autoimmune condition, the cyclical TED incidence observed in this long-term 19-year period may not be unusual, as other autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes also exhibit long-term cyclical incidence patterns.24

During 2000 to 2018, there was an increased clinical awareness of TED due to structural changes in the health care system. First and foremost, national guidelines were established to clarify when patients with TED should be referred by regular endocrinologists to endocrinologists who specialize in TED. Second, the treatment of TED has been centralized to 6 centers nationwide, where patients are examined by endocrinologists and ophthahlmologists who jointly plan their treatment. Third, the treatment for moderate to severe TED was changed from oral prednisolone to intravenous treatment with weekly methylprednisolone, which is known to be more effective for active TED.25 Fourth, orbital decompression was centralized and performed only at Rigshospitalet, the national hospital in Copenhagen. All of these implementations were carried out gradually over time, so we cannot pinpoint the specific effects of each factor on the incidence of TED and surgical interventions.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of our study is the use of an unbiased nationwide registry-based design that includes all diagnoses and surgical interventions from all hospitals in Denmark and all prescriptions from Danish pharmacies.26 A limitation of our study is that the registry-based TED diagnosis has not been validated. However, only endocrinological and ophtalmological specialists treat patients with TED and submit codes to the National Patient Registry. Therefore, the codes could have a higher specificity. Moreover, the clinical record systems used in Danish hospitals were partly replaced in an unsynchronized manner during the time period studied. Today, a hospital clinician is obliged to code a patient visit with an ICD-10 diagnosis by the clinical hospital system, which was not required previously. This could partly explain the shift in incidence of TED between 2004 and 2015. Furthermore, because clinicians are required to give patients a diagnosis code during the hospital visit, the most recent incidence numbers mirror the clinical reality of the incidence of patients with TED who are currently treated in the hospital.

In this registry-based study, we could not estimate procedures performed outside of the hospitals. We only included strabismus, strabismus surgery, and decompression surgery because the clinical practice for patients with TED in Denmark is that these conditions are treated at hospitals. Therefore, we have a complete registration of these procedures. The incidence of strabismus surgery is an estimate because of limitations that include differences in decisions for surgery between institutions, between surgeons, and between patients, who may choose conservative treatment with a prism or a patch. We studied these 3 diagnoses independently because patients with TED may go through several different procedures to treat their symptoms. Because the coding for the decompression surgery does not reveal if dysthyroid optic neuropathy or corneal involvement was present, we could not include these diagnoses in our study. The majority of eyelid surgeries are typically outsourced from hospitals to be performed in private clinics and could therefore not be included. Furthermore, because of the constraints of the registry-based design, we did not have access to laboratory data, histopathological information,27 or medical records and could therefore not describe the TED phenotype in any further detail. Our results can only be generalized to populations with similar ethnicity, iodine intake status, and health care access.

Conclusions

Our study provides clinical data about the Danish nationwide incidence of TED and strabismus, strabismus surgery, and decompression surgery associated with TED. Our data on the incidence of TED vary from previous studies because the nationwide design includes all patients with TED treated by a hospital clinician in Denmark from 2000 to 2018. The likelihood of strabismus (10%) or strabismus surgery (8%) was higher than of orbital decompression (5%) 4 years after being diagnosed with TED. While women were 4 times more prone to develop TED than men, men with TED were almost twice as likely to get strabismus surgery after diagnosis than women. Our results provide empirical clinical data on TED and should be used to inform patients and implement preventive health care strategies.

eFigure 1. Flowchart of the Danish nationwide register study of thyroid eye disease

eTable 1. List of diagnoses codes used in the study

eFigure 2. The distribution of sex in thyroid eye disease patients

eTable 2. Annual incidence (per 100,000) of thyroid eye disease in Denmark 2000-2018

eTable 3. Sex and the mean age of the thyroid eye disease patients in Denmark from 2000-2018

eTable 4. The calculated mean incidence (per 100,000/year) of thyroid eye disease in Denmark from 2000-2018

eTable 5. The thyroid medication prescribed in patients who were euthyroid at the time of being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 6. The cumulative incidence of being diagnosed with strabismus after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 7. The cumulative incidence of being diagnosed with strabismus after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex

eTable 8. The cumulative incidence of undergoing strabismus surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 9. The cumulative incidence of undergoing strabismus surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex

eTable 10. The cumulative incidence of undergoing decompression surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 11. The cumulative incidence of undergoing decompression surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex

References

- 1.Abraham-Nordling M, Byström K, Törring O, et al. Incidence of hyperthyroidism in Sweden. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(6):899-905. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartalena L, Piantanida E, Gallo D, Lai A, Tanda ML. Epidemiology, natural history, risk factors, and prevention of Graves’ orbitopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:615993. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.615993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Sharma A, Padnick-Silver L, et al. Physician-perceived impact of thyroid eye disease on patient quality of life in the United States. Ophthalmol Ther. 2021;10(1):75-87. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00318-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahaly GJ, Petrak F, Hardt J, Pitz S, Egle UT. Psychosocial morbidity of Graves’ orbitopathy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(4):395-402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02352.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartalena L, Kahaly GJ, Baldeschi L, et al. ; EUGOGO . The 2021 European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of Graves’ orbitopathy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021;185(4):G43-G67. doi: 10.1530/EJE-21-0479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, et al. Teprotumumab for the treatment of active thyroid eye disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(4):341-352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boulakh L, Toft-Petersen AP, Severinsen M, et al. Topical anaesthesia in strabismus surgery for Graves’ orbitopathy: a comparative study of 111 patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021. Published online September 16, 2021. doi: 10.1111/aos.15024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartalena L, Baldeschi L, Dickinson A, et al. ; European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) . Consensus statement of the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO) on management of GO. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158(3):273-285. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartley GB. The epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of ophthalmopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1994;92:477-588. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7886878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurberg P, Berman DC, Bülow Pedersen I, Andersen S, Carlé A. Incidence and clinical presentation of moderate to severe Graves’ orbitopathy in a Danish population before and after iodine fortification of salt. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(7):2325-2332. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449-490. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The R Project for Statistical Computing . A language and environment for statistical computing. Published 2020. https://www.r-project.org

- 15.Scanlon DO, Morgan BJ, Watson GW. Modeling the polaronic nature of p-type defects in Cu2O: the failure of GGA and GGA + U. J Chem Phys. 2009;131(12):124703. doi: 10.1063/1.3231869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray RJ. cmprsk: Subdistribution analysis of competing risks. Published January 6, 2022. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cmprsk

- 17.Macchia PE, Bagattini M, Lupoli G, Vitale M, Vitale G, Fenzi G. High-dose intravenous corticosteroid therapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001;24(3):152-158. doi: 10.1007/BF03343835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabi T, Rafiq N. Factors associated with severity of orbitopathy in patients with Graves’ disease. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2020;10(3):197-202. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_10_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcocci C, Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Panicucci M, Pinchera A. Studies on the occurrence of ophthalmopathy in Graves’ disease. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1989;120(4):473-478. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1200473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perros P, Crombie AL, Matthews JN, Kendall-Taylor P. Age and gender influence the severity of thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: a study of 101 patients attending a combined thyroid-eye clinic. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1993;38(4):367-372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb00516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Møllehave LT, Linneberg A, Skaaby T, Knudsen N, Jørgensen T, Thuesen BH. Trends in treatments of thyroid disease following iodine fortification in Denmark: a nationwide register-based study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:763-770. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S164824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisinger C, Jørgensen T, Toft U. A multifactorial approach to explaining the stagnation in national smoking rates. Dan Med J. 2018;65(2):A5448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verwohlt B. Fra individuelt valg til samfundsproblem: Danske forebyggelsesstrategier på rygeområdet 1950-2010 sammenlignet med Sverige. Tidsskr Forsk i Sygd og Samf. 2014;(21). doi: 10.7146/tfss.v0i21.19823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson CC, Harjutsalo V, Rosenbauer J, et al. Trends and cyclical variation in the incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in 26 European centres in the 25 year period 1989-2013: a multicentre prospective registration study. Diabetologia. 2019;62(3):408-417. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4763-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Längericht J, Krämer I, Kahaly GJ. Glucocorticoids in Graves’ orbitopathy: mechanisms of action and clinical application. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2020;11:2042018820958335. doi: 10.1177/2042018820958335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaist D, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44(4):445-448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nunery WR. Ophthalmic Graves’ disease: a dual theory of pathogenesis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1991;4(1):73-87. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Flowchart of the Danish nationwide register study of thyroid eye disease

eTable 1. List of diagnoses codes used in the study

eFigure 2. The distribution of sex in thyroid eye disease patients

eTable 2. Annual incidence (per 100,000) of thyroid eye disease in Denmark 2000-2018

eTable 3. Sex and the mean age of the thyroid eye disease patients in Denmark from 2000-2018

eTable 4. The calculated mean incidence (per 100,000/year) of thyroid eye disease in Denmark from 2000-2018

eTable 5. The thyroid medication prescribed in patients who were euthyroid at the time of being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 6. The cumulative incidence of being diagnosed with strabismus after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 7. The cumulative incidence of being diagnosed with strabismus after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex

eTable 8. The cumulative incidence of undergoing strabismus surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 9. The cumulative incidence of undergoing strabismus surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex

eTable 10. The cumulative incidence of undergoing decompression surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease

eTable 11. The cumulative incidence of undergoing decompression surgery after being diagnosed with thyroid eye disease stratified by sex