Abstract

Objective

Despite cross-sectional evidence that persons living with dementia receive disproportionate hours of care, studies of how care intensity progresses over time and differs for those living with and without dementia have been lacking.

Method

We used the 2011–2018 National Health and Aging Trends Study to estimate growth mixture models to identify incident care hour trajectories (“classes”) among older adults (N = 1,780).

Results

We identified 4 incident care hour classes: “Low, stable,” “High, increasing,” “24/7 then high, stable,” and “Low then resolved.” The high-intensity classes had the highest proportions of care recipients with dementia and accounted for nearly half of that group. Older adults with dementia were 3–4 times as likely as other older adults to experience one of the 2 high-intensity trajectories. A substantial proportion of the 4 in 10 older adults with dementia who were predicted to be in the “Low, stable” class lived in residential care settings.

Discussion

Information on how family caregiving is likely to evolve over time in terms of care hours may help older adults with and without dementia, the family members, friends, and paid individuals who care for them, as well as their health care providers assess and plan for future care needs.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Caregiving, Dementia, Longitudinal methods

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias account for a disproportionate share of care needs of the older population. One-third of caregivers provide assistance to the 10% of older adults living with dementia and account for 41% of aggregate care hours of assistance to community-residing older adults with limitations (Kasper et al., 2015). The type of assistance received from caregivers overlaps considerably for those living with and without dementia and includes help with self-care tasks such as bathing and dressing, mobility activities such as getting around inside and getting outside, household activities such as preparing meals and shopping, and medical activities such as medication and related medical care management (Schulz & Eden, 2016). In addition, older adults living with dementia may experience behavioral issues that require caregiver attention, such as wandering or not being able to be left alone (Gaugler et al., 2010).

Although estimates vary, the average number of care hours received from family and other unpaid caregivers by an older adult living with dementia is approximately twice that received by an older adult receiving assistance for other reasons. For example, analysis of the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) suggests 190 versus 111 family care or unpaid hours per month for those living with and without dementia, respectively (Kasper et al., 2015); figures based on the Health and Retirement Study are comparable at 171 versus about 85 hr per month (Friedman et al., 2015). Older adults with dementia are also more likely than other older adults to receive care hours from paid individuals alongside assistance from family caregivers and to live in residential care settings (Kasper et al., 2015).

Such cross-sectional characterizations, while informative regarding differences at a point in time between care provided to those with and without dementia, do not capture potential differences related to the progression of care. Yet to date, few longitudinal analyses have compared care trajectories for those living with and without dementia. A recent study by Jutkowitz and colleagues (2020) found that persons living with dementia experience more substantial increases in care hours in response to changes in activity limitations than do other older adults. Another study suggests dementia care recipients develop larger care networks involving more task sharing and greater reliance on more intensely engaged “generalist” caregivers (Spillman et al., 2020). These studies suggest differences in care patterns over time between those with and without dementia, but do not directly examine differences in care trajectories.

Studies examining trajectories—that is, using modeling techniques to group older adults with similar patterns over time—have rarely focused on care hours. One recent study (Hu, 2020) estimated trajectories of family care hours for the oldest-old in China and identified three classes (low, increasing, and high intensity), but the study examined only family-provided care for a subset of activities, and differences by dementia status were not explored. Other studies have focused on the physical or cognitive impairment trajectories that underlie care needs. Most studies of physical limitation trajectories, for example, find three to four prototypical patterns (or “classes”): persistently low, rising over time, and persistently high (MacNeil Vroomen et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2017; Stabenau et al., 2018). Similarly, studies of cognitive functioning trajectories also generally identify three to four classes: persistently high, gradual declines over time, and steep declines (Haaksma et al., 2018; Han et al., 2016; Wilkosz et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2020). A shift in emphasis from underlying care needs to care intensity may be able to better inform discussions of resources required to meet the aging population’s care needs as well as expectations of family members about how care hours typically evolve once care begins.

We build upon the existing literature in two ways. Substantively, our focus is on trajectories of care hours received (rather than underlying care needs) from family members and other unpaid and paid community sources, and differences in the distribution and makeup of classes for older adults with and without dementia. Second, our analysis attempts to address two common methodological issues in the existing literature that have impeded interpretation. Most studies include individuals who already have limitations and in doing so align individuals at different points in the disablement process in the same index year. That is, the time axis in most studies is years since first observation (for an exception, see Wolf et al., 2015, who model time backwards from death). In addition, studies often assume a smooth function from the initial year of observation through the end of the study observation period (or censoring or death). Together these approaches typically result in the identification of classes that monotonically increase or decrease (or remain stable) over time and that are also challenging to interpret. To obtain a more complete and more readily interpretable depiction of care progression, we model incident care hour trajectories (monthly hours each year since care began), adopting a specification that allows recovery to occur following incidence.

Using eight rounds of annual NHATS interviews, we estimate incident trajectories of care hours and examine whether having dementia when care is initiated predicts membership in particular classes. We also examine distributions across care hour classes by dementia status and compare characteristics across classes. Finally, in order to uncover heterogeneity by dementia status, where class sample sizes allow, we compare characteristics for those with and without dementia within classes. We expect those living with dementia to be more likely to experience care trajectories that are persistently increasing and, within classes, that those with dementia will have greater care needs than those without.

Data and Methods

Data

NHATS is a nationally representative panel study of U.S. Medicare enrollees aged 65 and older. NHATS has conducted annual interviews with participants each year since 2011, collecting detailed information on participants’ physical and cognitive capacity, the environment in which they live, and how activities of daily life are carried out, including the number of hours of care received from unpaid and paid caregivers. Response rates each year range between 71% and 96% (Freedman & Kasper, 2019).

Sample

We drew our analytic sample from individuals first interviewed in 2011. The 2011 cohort initially included 7,609 participants aged 65 and older in 2011 who completed a sample person interview during which care hours (defined below) were collected. Although nursing home residents were not eligible for the sample person interview in 2011, individuals in other residential care settings (e.g. independent, assisted living facilities) were interviewed as were those who subsequently moved into nursing home settings in follow-up rounds.

For this analysis, we draw upon annual interviews through 2018. We excluded 3,335 participants who reported no care hours in any survey round. We also excluded the cross-section of 2,494 participants who were already receiving care when first observed in 2011. The resulting sample consisted of 1,780 persons aged 65 and older in 2011 who began receiving care hours in any year from 2012 to 2018 (inclusive). For analyses, we realigned the data so that the first observation for each individual was the survey round in which care hours were first reported (hereinafter “index year”). We included all rounds until a sample person died or was lost to follow-up. As a result, the number of rounds varied across participants (range 1–7), with 29% having one, 22% having two, and the remaining 49% of participants having three or more rounds of observation. To provide context, we compare this analytic sample with a cross-sectional sample of individuals receiving help in 2011 (N = 2,494).

Measures

Monthly care hours

In each round, participants were asked to identify all individuals who helped them in the last month with self-care, mobility, and household activities. Hours of care were ascertained for all individuals identified as helping, with one exception. For persons living in residential care settings (including nursing home, assisted and independent living settings), hours of assistance provided by the place of residence were not collected. For all other helpers, participants were asked to report the number of days per month or per week that each person assisted and, on days when help was given, how many hours per day. From these responses, we calculated for each round the monthly hours of care provided by each person assisting.

In cases where one or more components needed to calculate monthly hours were missing, we conducted round-specific imputation using previously developed algorithms to maximize comparability across rounds (Freedman et al., 2014). After applying a logarithm transform to nonmissing hours, we estimated separate regression models for different patterns of missing information. Predictors included relationship to recipient, regularity of help provided, a set of variables characterizing the activities with which the individual assisted, and an indicator of whether the recipient was high need. Among those assisting NHATS participants in our analytic sample, across all rounds combined, approximately 18% of observations were imputed (with 5% missing information on both days and hours per day and 13% missing just the hours per day component). Among NHATS participants in our analytic sample, 39 (<2% of cases) had hours fully imputed. In sensitivity analyses, we explored whether our results were robust to the exclusion of these 39 cases.

For each participant, we summed hours across all helpers in a given round to calculate the total number of hours of care received in the prior month. If a participant only received help with household activities for reasons other than their health or functioning in a round, care hours were assigned as 0 for that round. In analyses, we transformed care hours, using its square root, to facilitate visual inspection of the data and help normalize the care hours distribution.

Probable dementia

The primary predictor of interest is whether the participant was classified as having probable dementia (hereafter “dementia”) in the index year. Participants were classified as having dementia if: (a) the participant or their proxy respondent reported that the participant had been told by a doctor that they had dementia or Alzheimer’s disease; (b) the participant received a score of 2 or more (out of 8) on the AD8 Dementia Screening Interview that is administered to a proxy respondent (Galvin et al., 2005); or (c) the NHATS participant was impaired in at least two of the three cognitive domains (memory, orientation, and executive function) assessed by NHATS’ series of cognitive tests. In this context, impairment was defined as having a score at 1.5 SDs or more below the mean. Cognitive tests included an immediate and 10-word recall, naming the date, month, year, and day of the week, naming the President and Vice-President, and a clock drawing test (for details, see Kasper et al., 2013). In sensitivity analyses, we explored whether findings were robust when we also identified individuals with possible dementia, defined as impaired in at least one of the three cognitive domains assessed by tests. Because the NHATS measure of possible dementia is less stable than probable dementia, we limited its use to sensitivity analyses.

Other measures

In models, we controlled for a number of sociodemographic characteristics of the care recipient measured at the index year, including age as a continuous variable, gender (female vs male), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White or other vs non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic), and education (less than high school, high school diploma or some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher). We also characterized opportunities for care with an indicator of whether the participant was married or cohabiting, the number of living children (no children, one child, two or more children) that the participant had, and whether the participant lived in a residential care setting. Measures of need for care at the onset included the participant’s physical capacity (scale from 0 to 12 reflecting the participant’s ability to walk, climb stairs, lift and carry, kneel, reach, and use their hands); receipt of help with self-care or mobility activities (e.g., bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, getting around inside, getting out of bed, and getting outside) or with household activities for health or functioning reasons (e.g., laundry, making meals, shopping, managing money, and managing medications); and an indicator of any behavioral issues (getting lost in familiar environments, unable to be left alone for 1 hr, wandering and not returning, and seeing and hearing things). We also constructed a measure of whether the participant received any paid help in their index year (excluding help received from the place they lived if in residential care), but models were not stable when this covariate was introduced together with others listed above. Hence, we limited our analysis of any paid care to descriptive analyses described below. Finally, for descriptive purposes, we created indicators of whether over the observation period the participant ever moved into residential care, ever developed dementia, died, or was lost to follow-up.

Analytical Approach

We estimated tobit growth mixture models (GMMs) to group participants into classes. GMM is a method for identifying and describing change in an outcome over time, in this case monthly hours of care, for multiple unobserved classes (Ram & Grimm, 2009). Model parameters provide information about the initial level and slope(s) for each class as well as coefficients for predictors of class membership (relative to an omitted class). The model also allows estimation of the probability of belonging to each class, which is used to assign a predicted class to each participant.

To determine the number of classes, we first estimated a model with three classes and then incremented the number by one until the model fit stopped improving. Bootstrapped model log-likelihood comparisons and Bayesian information criteria (BIC) were used to assess model fit. We included both intercept and slope parameters for each class and constrained residual variances of these parameters to be equivalent across classes. We censored cases in the year the death was reported or the year the participant was lost to follow-up.

We initially found support for a five-class model with linear trajectories; however, the model was unstable once covariates were introduced. We therefore opted for four classes. Before finalizing the base model, we examined individual-level trajectories within class (i.e., spaghetti plots) and identified the need for a spline specification for the slope at index year + 1. The four-class model with the spline had a lower BIC than without the spline and considerably better characterized trajectories as observed through plotting, and was thus considered a better fit. See Supplementary Table A1 for fit statistics. We next added covariates to the GMM as predictors of class membership. Based on this adjusted model, probabilities for being in each class were estimated and participants were assigned to the class for which their probability of membership was highest.

Using these assigned classes, we conducted descriptive analyses. We graphed mean hours of care in each class over time and examined the distribution of participants across predicted classes by dementia status in the index year. We then examined differences in participant characteristics across predicted classes. Finally, for the two predicted classes most common for individuals living with dementia, we examined within-class differences in mean initial care hours and sociodemographic and care-related characteristics for those with and without dementia.

We used Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017) to estimate the GMMs and Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, 2017) for descriptive analyses. All analyses were weighted using the index year weight and adjusted for the complex survey design of NHATS.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Weighted sample characteristics at care initiation are shown in Table 1 overall and by dementia status. Older adults with dementia, who comprised 14% of older adults in their incident care year, received an average of 187 care hours per month in the incident year. By comparison, those living without dementia received on average 98 care hours. Among all older adults in their initial year of help, half received assistance with self-care or mobility activities and two-thirds received assistance with household activities. By the seventh year, about 5% had moved into a residential care setting, nearly 10% developed probable dementia (11% among those without dementia initially), 22% died, and 18% were lost to follow-up. Compared with a cross-sectional sample of all individuals receiving help in 2011 (see Supplementary Table A2), the incident sample (those beginning care) initially received fewer hours of care (110 hr in the index year vs 163 hr for the 2011 cross-section) and was less likely to have dementia (14% in the index year vs 29% for the 2011 cross-section).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Older Adults Receiving Care Hours for Daily Activities by Dementia Status the Year Care Began: Weighted Percent/Mean (SD)

| Variable | All | Does not have dementia | Has dementia | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes year care began | ||||

| Mean care hours (monthly) | 110.5 (192.6) | 98.1 (170.3) | 186.7 (292.4) | <.001d |

| Mean square root of care hours (monthly) | 8.4 (6.3) | 8.0 (5.8) | 11.1 (8.3) | <.001d |

| Characteristics year care began | ||||

| Has probable dementia | 14.0 | — | — | — |

| Age (range: 66–101) | 79.3 (6.8) | 78.9 (6.6) | 81.7 (7.5) | <.001d |

| Female | 57.7 | 59.0 | 49.5 | .017e |

| Non-Hispanic White or other vs non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic | 86.3 | 87.0 | 82.4 | .035e |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high school | 20.7 | 18.6 | 33.7 | <.001e |

| High school/some college | 52.9 | 53.7 | 47.6 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 26.4 | 27.7 | 18.7 | |

| Married/cohabiting | 50.6 | 52.7 | 37.8 | .001e |

| Number of children | ||||

| 0 | 9.8 | 8.9 | 15.3 | .026e |

| 1–2 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 10.2 | |

| 2+ | 79.0 | 79.7 | 74.5 | |

| Lived in residential care | 11.1 | 9.8 | 19.3 | .001e |

| Physical capacity (range: 0–12) | 7.6 (3.5) | 7.7 (3.3) | 6.8 (4.2) | .022d |

| Gets help with: | ||||

| Self-care and mobility activitiesa | 53.1 | 52.9 | 54.4 | .627e |

| Household activitiesb | 64.2 | 63.3 | 70.3 | .062e |

| Any behavioral issuesc | 2.9 | 0.6 | 17.1 | <.001e |

| Any paid help year care began | 16.9 | 16.7 | 18.1 | .592e |

| Changes in characteristics over observation period | ||||

| Moved into residential care | 5.4 | 5.0 | 8.2 | .467e |

| Developed probable dementia | 9.8 | 11.4 | — | — |

| Died | 21.6 | 18.9 | 37.9 | <.001e |

| Lost to follow-up | 17.7 | 17.1 | 21.6 | .153e |

| N | 1,780 | 1,504 | 276 |

aGoing outside, getting around inside, getting in and out of bed, eating, bathing, dressing, and toileting.

bLaundry, shopping, preparing meals, banking, and managing medications.

cGets lost in familiar environments, cannot be left alone for 1 hr, wanders and does not return, and sees and hears things.

d F test.

eChi-squared test.

Model Results

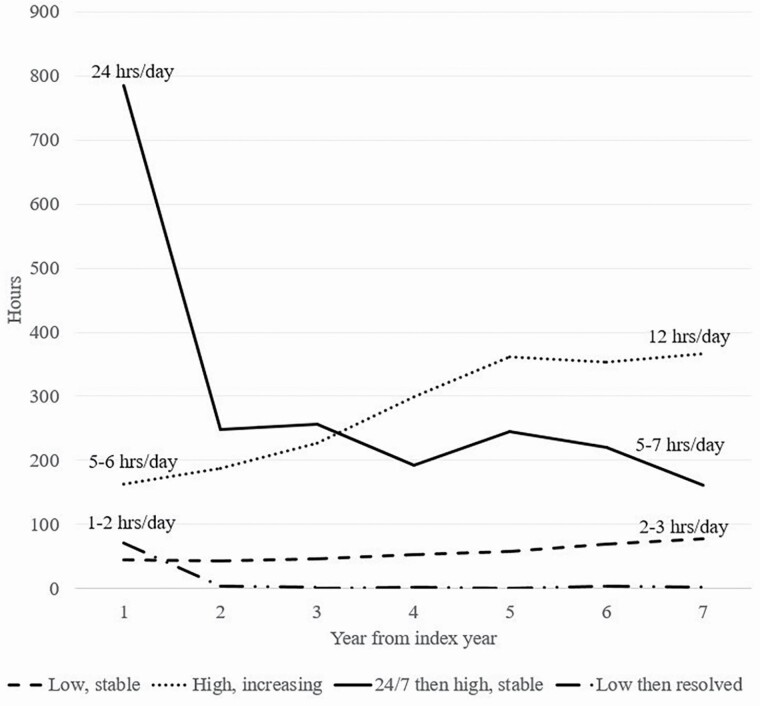

Mean hours for each class based on predictions from the full model are shown in Figure 1 over the observation period. The “Low, stable” class (dashed line) experienced an initially low number of hours (44 per month or on average 1–2 per day) that increase slowly over the period to about 2–3 hr per day. The “High, increasing” class (dotted line) had a high number of hours in the index year (162 per month or 5–6 hr per day) with hours increasing over the period (reaching 365 per month or about 12 per day). The “24/7 then high, stable” class (solid line) initially had a very high number of hours (more than 700 per month or 24 per day) followed by a drop in hours to a still substantial level of hours (about 160–260 per month or about 5–7 per day) sustained over the period. Finally, the “Low then resolved” class (dashed and dotted line) had an initially low number of hours (70 per month or about 2–3 per day) that declined to very few hours over the period.

Figure 1.

Incident monthly care hour trajectories for older adults.

Controlling for sociodemographic factors and care needs, participants with dementia when care began were considerably more likely than those without dementia of being in the two high-intensity classes (“High, increasing” and “24/7 then high, stable”) relative to the “Low, stable” class (see Table 2). Specifically, the relative prevalence in these classes versus the “Low, stable” class was 3.6 times higher [exp(1.29)] for those with versus without dementia for the “High, increasing” and 4.6 times higher [exp(1.53)] for “24/7 then high, stable” classes. Age, gender, marital status, residential care setting, physical capacity, and receipt of help with any self-care or mobility activities were also significantly associated with class membership. Excluding cases with fully imputed hours (n = 39) yields essentially identical results (Supplementary Table A3).

Table 2.

Intercept and Slope Parameters and Coefficients Predicting Class Membership From Growth Mixture Model of Square Root of Incident Monthly Care Hours (N = 1,780)

| Low, stable | High, increasing | 24/7 then high, stable | Low then resolved | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | ||||

| Intercept 1 | 5.98** (0.41) | 11.48** (2.01) | 27.38** (1.33) | 7.05** (0.48) |

| Slope 1 (year 1–2) | −3.64** (0.78) | −1.48 (1.01) | −17.50** (3.26) | −18.47** (1.97) |

| Slope 2 (years 2+) | 4.40** (0.84) | 3.30* (1.31) | 17.41** (3.44) | 18.71** (2.73) |

| Coefficients for predictors of class membership (vs low, stable) | ||||

| Has dementia | 1.29** (0.41) | 1.53* (0.59) | −0.35 (0.67) | |

| Age (years; centered on age 70) | 0.06* (0.03) | 0.03 (0.03) | −0.10** (0.02) | |

| Female | −1.23** (0.27) | −1.15** (0.35) | 0.029 (0.38) | |

| White or other (vs Black or Hispanic) | −0.79 (0.41) | −0.61 (0.40) | −0.27 (0.30) | |

| Education (vs less than high school) | ||||

| High school/some college | −0.48 (0.29) | −0.36 (0.34) | 0.01 (0.35) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | −0.25 (0.48) | −0.18 (0.42) | 0.25 (0.43) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 1.14** (0.39) | 1.61** (0.42) | 0.28 (0.39) | |

| Number of children (vs 0) | ||||

| 1 child | 0.25 (0.69) | 0.92 (0.62) | 1.05 (0.63) | |

| 2+ children | 0.03 (0.56) | 1.08 (0.59) | 0.45 (0.58) | |

| Lives in residential care | −2.22 (1.54) | −1.91* (0.77) | −2.35* (1.02) | |

| Physical capacity (range: 0–12) | −0.11** (0.04) | −0.21** (0.05) | 0.15** (0.05) | |

| Gets help with: | ||||

| Self-care and mobility activitiesa | 0.80* (0.32) | 1.59** (0.45) | 0.80 (0.42) | |

| Household activitiesb | 0.57 (0.50) | 0.51 (0.35) | 0.20 (0.47) | |

| Any behavioral issuesc | 0.55 (1.08) | 1.51 (0.91) | −0.95 (1.27) | |

| Intercept | −0.80 (0.91) | −3.29** (1.13) | −2.14* (0.89) |

aGoing outside, getting around inside, getting in and out of bed, eating, bathing, dressing, and toileting.

bLaundry, shopping, preparing meals, banking, and managing medications.

cGets lost in familiar environments, cannot be left alone for one hour, wanders and does not return, and sees and hears things.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

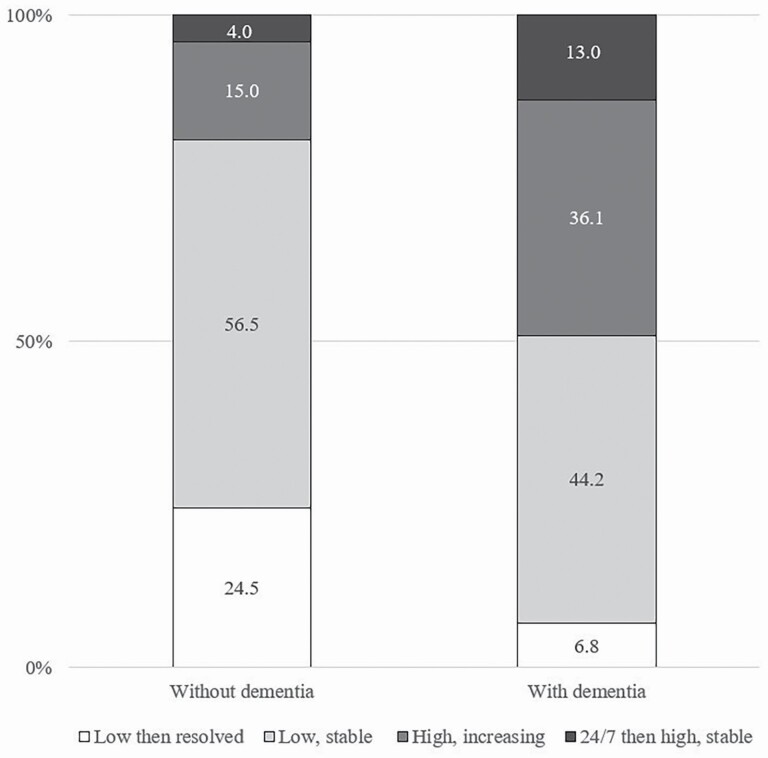

Estimated Class Distributions and Characteristics

Distributions of class membership varied markedly by dementia status (Figure 2; p < .001 for chi-squared test of difference). About half of care recipients with dementia were in the two high-intensity classes, whereas only one in five older adults without dementia was in these classes. Among older adults with dementia, 36% were in the “High, increasing” class and 13% in the “24/7 then high, stable” class, whereas 44% were in the “Low, stable” class and nearly 7% were in the “Low then resolved” class. For the group without dementia, the corresponding estimates were 15%, 4%, 57% and 25%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of older adults across incident monthly care hour trajectories by dementia status.

Characteristics of older adults receiving care differed by class (Table 3) in several notable ways. First, the “High, increasing” and “24/7 then high, stable” classes had the highest proportions of care recipients with dementia, 28.1% and 34.3%, respectively, which is two to three times higher than the prevalence in the “Low, stable” group of 11.3%. These classes also differed from the low-intensity groups in other important ways. For instance, a higher percentage of the high-intensity classes had less than a high school education (nearly three in 10). Second, the care needs of the “24/7 then high, stable” class differed in notable ways from the other three classes. These older adults had the lowest physical capacity scores and were more likely to be receiving assistance with self-care or mobility (83%), to have behavioral issues (18%), to have received paid help (42%) when care began, and to die over the observation period (43%). Third, individuals in the “Low then resolved” class were youngest (mean age about 75), had the highest physical capacity scores when care began, and were least likely to have (4%) or develop (3%) dementia or die (6%) over the observation period.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Older Adults in Each Care Hour Class: Weighted Percent/Mean (SD)

| Variable | Low, stable | High, increasing | 24/7 then high, stable | Low then resolved | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome year care began | |||||

| Mean care hours (monthly) care | 44.4 (46.7) | 162.8 (107.7) | 784.5 (351.4) | 70.4 (73.6) | <.001d |

| Index year characteristics | |||||

| Has dementia | 11.3 | 28.1 | 34.3 | 4.3 | <.001e |

| Age | 80.2 (6.7) | 81.8 (7.0) | 80.0 (7.6) | 74.7 (4.4) | <.001d |

| Female | 67.5 | 30.0 | 38.6 | 60.4 | <.001a |

| Non-Hispanic White or other (vs non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic) | 89.7 | 79.5 | 83.6 | 84.3 | <.001e |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 19.9 | 29.9 | 27.9 | 15.2 | <.001e |

| High school/some college | 57.7 | 43.7 | 48.6 | 49.3 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 23.1 | 26.4 | 23.6 | 35.5 | |

| Married/cohabiting vs not married | 36.6 | 66.0 | 71.4 | 67.8 | <.001e |

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 12.9 | 9.2 | 4.6 | 3.8 | <.001e |

| 1 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 8.9 | 17.3 | |

| 2+ | 78.0 | 80.0 | 86.5 | 78.9 | |

| Lives in residential care | 18.5 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 1.0 | <.001e |

| Physical capacity (range: 0–12) | 7.4 (3.4) | 6.8 (3.8) | 4.9 (4.1) | 9.3 (2.4) | <.001d |

| Gets help with: | |||||

| Self-care and mobility activitiesa | 41.1 | 63.6 | 83.3 | 67.2 | <.001e |

| Household activitiesb | 69.6 | 66.4 | 69.9 | 47.8 | <.001e |

| Any behavioral issuesc | 1.8 | 5.5 | 18.0 | 0.1 | <.001e |

| Any paid help | 13.6 | 19.6 | 42.1 | 17.1 | <.001e |

| Changes over observation period | |||||

| Moved into residential care | 7.0 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 1.0 | <.001e |

| Developed probable dementia | 10.9 | 14.6 | 10.6 | 2.9 | <.001e |

| Died | 22.2 | 32.2 | 43.2 | 6.2 | <.001e |

| Lost to follow-up | 16.0 | 21.2 | 13.0 | 20.3 | .141e |

| n | 981 | 377 | 115 | 307 |

aGoing outside, getting around inside, getting in and out of bed, eating, bathing, dressing, and toileting.

bLaundry, shopping, preparing meals, banking, and managing medications.

cGets lost in familiar environments, cannot be left alone for one hour, wanders and does not return, and sees and hears things.

d F test.

eChi-squared test.

For the two most common classes among those living with dementia—“Low, stable” and “High, increasing”—we found substantially similar initial hours within classes for those with and without dementia (Supplementary Table A4). However, within the “Low, stable” class, individuals with dementia were less likely to have a spouse/partner or children and substantially more likely to live in residential care (37.7% among those with dementia vs 16.1% among those without). Within the “High, increasing” class, individuals with dementia also were less likely to have a spouse or partner (but no less likely to have children), and were more likely to be female and to initially get help with household activities.

Sensitivity to Possible Dementia

Finally, in sensitivity analyses, we re-estimated the final GMM with an indicator that distinguished possible from probable dementia at the time care began (Supplementary Table A5). We found that classes and coefficients for predictors of class membership, including for probable dementia, were robust when possible dementia was included. We also found that the relative prevalence of being in the “High, increasing” class versus the “Low, stable” class was 2.3 times higher [exp(0.84)] among those with possible dementia when care began compared to those without dementia. Consequently, similar to those without dementia, among those with possible dementia, 56% were classified in the “Low, stable” class and fewer than 5% in the “24/7 then high, stable” class. For the remaining classes, prevalence fell between those with and without dementia; 29% of those with possible dementia were in the “High, increasing” class and nearly 10% in the “Low then resolved” class.

Discussion

Using a national sample of older adults followed over 7 years, we identified four patterns of incident care hour trajectories. The number of trajectories is consistent with much of the prior literature on the evolution of underlying care needs over time (MacNeil Vroomen et al., 2018; Martin et al., 2017; Stabenau et al., 2018). However, our model specification allowed identification of two dynamic classes not previously identified: one experiencing a sharp decline in hours following round-the-clock care then stabilizing at a high level and another starting with a low number of hours and declining sharply before dissipating altogether. The remaining two classes align well with previously identified care need trajectories: a stable low level of care hours (about 2 hr per day) and a high and increasing number of care hours (from about 3–4 hr per day to about 12).

Mirroring prior cross-sectional studies indicating higher hours of care (Friedman et al., 2015; Kasper et al., 2015) and larger care networks (Spillman et al., 2020) for those with dementia, we found in the year care was initiated older adults with dementia received on average twice as many care hours as those without dementia (187 vs 98). The reasons for higher-intensity hours at the outset among those living with dementia are not explored in this analysis, but could include lack of timely acknowledgment of care needs, particularly in the case of the 24/7 then high, stable class. Irrespective of the reason, we found marked differences by dementia status in the chances of experiencing a high-intensity trajectory. Nearly half of the group living with dementia at the start of care was classified in one of the high-intensity classes (compared to 19% of those without dementia); these elevated risks were even stronger after controlling for differences between those with and without dementia in sociodemographic characteristics and care-related needs. Findings underscore that about half the time an older adult with dementia may require marshaling of a network of committed caregivers able to provide a substantial number of hours of assistance over many years.

Despite greater odds of experiencing a high-intensity care trajectory, nearly four out of 10 older adults with dementia were in the “Low, stable” class in which care hours started at about 2 hr per day and remained low over time. Notably, nearly 40% of these individuals were living in residential care settings in the year when their care began, more than twice the percentage for those without dementia. Moreover, those with dementia in this class had fewer family members relative to those without dementia. Together these findings imply for a substantial proportion of older adults living with dementia that facility services may be partially substituting for family and other paid and unpaid hours and that family caregiver involvement continues in these settings, albeit at relative low levels.

Our analysis also highlights that for the one in four older adults who have dementia, live in the community, and are in the “Low, stable” care class, there is a need to better understand to what extent low levels indicate unmet need for assistance versus a lack of discernible disease progression. Unmet need is especially important to understand because studies have found generally among older adults and specifically among those living with dementia a link to various negative outcomes, including avoidable hospitalizations, nursing home admission, and death (Depalma et al., 2013; Gaugler et al., 2005; LaPlante et al., 2004).

Finally, we demonstrated in sensitivity analyses that those with possible dementia when care began—like those with dementia—were more likely than those without dementia to have high, increasing care trajectories. However, those with possible dementia differed from those with dementia in that they did not have elevated chances of initially experiencing round-the-clock care, followed by high, stable hours. This finding underscores the importance of investigating the mechanism underlying the trajectory characterized by initial 24/7 care and subsequent high care levels. Understanding what precipitates this trajectory could lead to guidance for families and care providers regarding whether initiating the diagnosis and care planning process earlier in the course of dementia may deter cascading events that exacerbate care needs over time.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because we focused on incident care hours, sample sizes were limited, so we were unable to estimate interactions between class parameters (intercepts, slopes) and dementia status. However, for the two groups that were large enough to stratify by dementia status, we confirmed that mean care hours were substantially similar for those with and without dementia at the start of care. Second, we did not attempt to model mortality or attrition. Instead, we treated these as censoring events. Although attrition levels did not vary across classes, mortality was substantially higher for those in the two high-intensity groups and twice as high for those living with (vs without) dementia at the start of care. Others have documented that in the last 10 years of life, individuals with dementia experience a steady increase in hours, whereas those without dementia experience a steep increase in the final year of life (Reckrey et al., 2021). Future research should attempt to integrate these additional nuances. Finally, we focused on dementia, but a substantial proportion of the older population is living with milder forms of cognitive impairment and progresses to more debilitating stages. One in 10 of those without dementia when care began were found to have dementia later in the study period. This group of individuals is likely to overlap considerably with individuals with milder forms of cognitive impairment at the start of care. Although we undertook sensitivity analyses distinguishing those with possible dementia, future work on care trajectories should distinguish stages of cognitive impairment including timing of diagnosis, which may influence care decisions.

Conclusions

Study results have implications for practice and related research. National efforts to improve family caregiving, generally, and dementia caregiving, in particular, have not previously been able to draw upon generalizable evidence regarding how the intensity of care progresses over time (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021a, 2021b). Our analysis finds that although the care needs of many older adults without dementia fully resolve or remain at relatively low levels, those living with dementia generally follow one of three distinct prototypical courses: beginning with 3–4 hr per day and increasing slowly to 12 or more hours per day, beginning with an initial event requiring 24/7 care followed by a stable 5–7 hr of care per day, or beginning and persisting at a low level (1–2 hr per day) often accompanied by residential care services. By classifying individuals in terms of care hour trajectories, these results provide insights into the timing of when care is received. Practitioners may be able to use this information to encourage planning for recruiting additional family caregivers as well as paid caregivers or for exploring residential care options as needs evolve.

Future research is needed to explore factors that influence the timing of care initiation and whether earlier introduction of care among those with cognitive decline is protective in preventing or delaying high-intensity care trajectories. Of particular interest is whether there are steps that might be effective in averting the “24/7” class that has likely experienced a debilitating precipitating event. Although this class is small, it involves a disproportionate and particularly demanding share of family care resources and is a more common trajectory among persons with dementia (13% vs about 4% for those without dementia and with possible dementia). Investigation is also needed concerning the consequences of care trajectories for care recipients’ and caregivers’ health and well-being. Together with the findings from this study, this information may help practitioners to better assess and counsel older adults with and without dementia and the family members and friends who care for them about future care needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the NHATS 10th Anniversary Virtual Conference, May 26–27, 2021. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent those of their employers or the funding agency.

Contributor Information

Vicki A Freedman, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Karen Bandeen-Roche, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jennifer C Cornman, Jennifer C. Cornman Consulting, Granville, Ohio, USA.

Brenda C Spillman, Urban Institute, Washington, D.C., USA.

Judith D Kasper, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jennifer L Wolff, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG054004, P30AG012846). This paper was published as part of a supplement sponsored by the University of Michigan and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health with support from the National Institute on Aging (U01AG032947 and P30AG012846).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

V. A. Freedman, K. Bandeen-Roche, and J. D. Kasper planned the study; J. C. Cornman analyzed the data with input from V. A. Freedman and K. Bandeen-Roche; V. A. Freedman, J. C. Cornman and K. Bandeen-Roche drafted the manuscript; all authors provided input on the study design, and contributed to initial drafts and revisions of the paper.

References

- Depalma, G., Xu, H., Covinsky, K. E., Craig, B. A., Stallard, E., Thomas, J.3rd, & Sands, L. P. (2013). Hospital readmission among older adults who return home with unmet need for ADL disability. The Gerontologist, 53(3), 454–461. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., & Kasper, J. D. (2019). Cohort profile: The National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1044–1045. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, V. A., Spillman, B. C., & Kasper, J. D. (2014). Hours of care in Rounds 1 and 2 of the National Health and Aging Trends Study. NHATS Technical Paper #7. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. www.NHATS.org [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, E. M., Shih, R. A., Langa, K. M., & Hurd, M. D. (2015). US prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(10), 1637–1641. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, J. E., Roe, C. M., Powlishta, K. K., Coats, M. A., Muich, S. J., Grant, E., Miller, J. P., Storandt, M., & Morris, J. C. (2005). The AD8: A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology, 65(4), 559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E., Kane, R. L., Kane, R. A., & Newcomer, R. (2005). Unmet care needs and key outcomes in dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(12), 2098–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E., Wall, M. M., Kane, R. L., Menk, J. S., Sarsour, K., Johnston, J. A., Beusching, D., & Newcomer, R. (2010). The effects of incident and persistent behavioral problems on change in caregiver burden and nursing home admission of persons with dementia. Medical Care, 48(10), 875–883. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ec557b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaksma, M. L., Calderón-Larrañaga, A., Olde Rikkert, M. G. M., Melis, R. J. F., & Leoutsakos, J. S. (2018). Cognitive and functional progression in Alzheimer disease: A prediction model of latent classes. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(8), 1057–1064. doi: 10.1002/gps.4893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, L., Gill, T. M., Jones, B. L., & Allore, H. G. (2016). Cognitive aging trajectories and burdens of disability, hospitalization and nursing home admission among community-living older persons. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(6), 766–771. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. (2020). Trajectories of informal care intensity among the oldest-old Chinese. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 266, 113338. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkowitz, E., Gozalo, P., Trivedi, A., Mitchell, L., & Gaugler, J. E. (2020). The effect of physical and cognitive impairments on caregiving. Medical Care, 58(7), 601–609. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. D., Freedman, V. A., & Spillman, B. (2013). Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Technical Paper #5. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. www.NHATS.org. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. D., Freedman, V. A., Spillman, B. C., & Wolff, J. L. (2015). The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(10), 1642–1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante, M. P., Kaye, H. S., Kang, T., & Harrington, C. (2004). Unmet need for personal assistance services: Estimating the shortfall in hours of help and adverse consequences. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59(2), S98–S108. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.2.s98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil Vroomen, J. L., Han, L., Monin, J. K., Lipska, K. J., & Allore, H. G. (2018). Diabetes, heart disease, and dementia: national estimates of functional disability trajectories. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(4), 766–772. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, L. G., Zimmer, Z., & Lee, J. (2017). Foundations of activity of daily living trajectories of older americans. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(1), 129–139. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . (2021a). Reducing the impact of dementia in America. National Academy Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26175/reducing-the-impact-of-dementia-in-america-a-decadal-survey [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . (2021b). Meeting the challenge of caring for persons living with dementia and their care partners and caregivers: A way forward. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/26026/meeting-the-challenge-of-caring-for-persons-living-with-dementia-and-their-care-partners-and-caregivers [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram, N., & Grimm, K. J. (2009). Growth mixture modeling: A method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(6), 565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey, J. M., Bollens-Lund, E., Husain, M., Ornstein, K. A., & Kelley, A. S. (2021). Family caregiving for those with and without dementia in the last 10 years of life. JAMA Internal Medicine, 181(2), 278–279. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R., & Eden, J. (Eds.). (2016). Families caring for an aging America. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillman, B. C., Freedman, V. A., Kasper, J. D., & Wolff, J. L. (2020). Change over time in caregiving networks for older adults with and without dementia. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(7), 1563–1572. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabenau, H. F., Becher, R. D., Gahbauer, E. A., Leo-Summers, L., Allore, H. G., & Gill, T. M. (2018). Functional trajectories before and after major surgery in older adults. Annals of Surgery, 268(6), 911–917. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkosz, P. A., Seltman, H. J., Devlin, B., Weamer, E. A., Lopez, O. L., DeKosky, S. T., & Sweet, R. A. (2010). Trajectories of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(2), 281–290. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209991001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, D. A., Freedman, V. A., Ondrich, J. I., Seplaki, C. L., & Spillman, B. C. (2015). Disability trajectories at the end of life: A “Countdown” model. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(5), 745–752. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., Phyo, A. Z. Z., Al-Harbi, T., Woods, R. L., & Ryan, J. (2020). Distinct cognitive trajectories in late life and associated predictors and outcomes: A systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, 4(1), 459–478. doi: 10.3233/ADR-200232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.