Abstract

Purpose:

Many young people are not aware of their rights to confidential sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care. Given that online health information seeking is common among adolescents, we examined how health education Web content about SRH for young people addresses confidentiality.

Methods:

In Spring 2017, we conducted Google keyword searches (e.g., “teens” and “sex education”) to identify health promotion Web sites operated by public health/medical organizations in the United States and providing original content about SRH for adolescents/young adults. Thirty-two Web sites met inclusion criteria. We uploaded Web site PDFs to qualitative analysis software to identify confidentiality-related content and conduct thematic analysis of the 29 Web sites with confidentiality content.

Results:

Sexually transmitted infection testing and contraception were the SRH services most commonly described as confidential. Clear and comprehensive definitions of confidentiality were lacking; Web sites typically described confidentiality in relation to legal rights to receive care without parental consent or notification. Few mentioned the importance of time alone with a medical provider. Only half of the Web sites described potential inadvertent breaches of confidentiality associated with billing and even fewer described other restrictions to confidentiality practices (e.g., mandatory reporting laws). Although many Web sites recommended that adolescents verify confidentiality, guidance for doing so was not routinely provided. Information about confidentiality often encouraged adolescents to communicate with parents.

Conclusions:

There is a need to provide comprehensive information, assurances, and resources about confidentiality practices while also addressing limitations to confidentiality in a way that does not create an undue burden on adolescents or reinforce and exacerbate confidentiality concerns.

Keywords: Confidentiality, Contraception, Sexually transmitted infections

Confidentiality is a cornerstone of adolescent health care according to professional medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine [1,2]. Recommendations for providing confidential care draw on evidence that young people are less likely to receive health services, given concerns about sensitive information, such as sexual behavior, being shared with their parents or guardians [3,4]. Specifically, young people may forgo seeking care or be less likely during clinic visits to truthfully discuss sensitive information which could indicate a need for services [5]. Confidentiality-related practices are particularly important for providing sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care, including sexually transmitted infection (STI)/HIV testing, contraception, condoms, and counseling about such topics.

Core tenets of confidential practice include ensuring time alone between adolescent patients and their providers as well as maintaining privacy of information disclosed and services received during any health-care interaction and follow-up (e.g., billing, provision of test results) [1,2]. Within the context of SRH, state laws that allow adolescents to self-consent for contraceptive and STI/HIV services without parental notification also facilitate confidentiality [6]. Despite legal protections, implementation of specific confidentiality practices is suboptimal [7,8]. For example, recent national data suggest that only about 40% of 15- to 17-year-olds receive time alone with their provider [8]. A known barrier to the delivery of confidential care is that adolescents are unaware of their right to access SRH services without parental permission or notification. Even if they are aware of legal protections, they may be uncertain about whether their provider will adhere to them [9–13].

Given this context, it is critical that young people are educated about confidentiality practices and empowered as health consumers to obtain confidential SRH care. However, we know little about the information young people receive related to confidential SRH services. Online health promotion content from public health/clinical organizations offers an opportunity to address this gap in a systematic way that yields clear practice implications. Adolescents and young adults use the Internet to seek information about SRH [14], and health-related organizations that provide health education information online likely have interest in and would benefit from recommendations to strengthen their Web sites. Insight into such an assessment can also inform health education in school and clinic settings. Accordingly, we conducted a content analysis of SRH content for adolescents and young adults on Web sites operated by organizations with a mission related to public health or clinical services. We characterize current messages about confidentiality and identify their strengths and weaknesses to inform future health promotion information that has the potential to improve receipt of confidential SRH services among adolescents and young adults.

Methods

Web site identification

Content for this study came from health promotion Web sites included as part of a project to assess the extent to which pregnancy prevention messages for adolescents and young adults also addressed STI prevention [15]. To systematically identify Web sites for that project, we conducted keyword searches combining adolescent/young adult terms (i.e., teen, young, youth, and girls) with SRH terms (i.e., sexual health, sex education, birth control, IUD, implant, the pill) in Google, the most popular search engine worldwide [16]. We turned off location services and used an “incognito” browser to minimize personalized search results. URLs from the first five pages (~ 50 links) of each keyword search were selected, yielding an initial set of 739 URLs from 425 Web sites. After removing duplicates (n=129 URLs from 65 Web sites), two individuals (R.J.S., C.N.R.) independently screened each URL to identify eligible Web sites using defined inclusion criteria. Specifically, the URL reviewed had to include (1) original health promotion content (i.e., educational information beyond just advertising SRH services); (2) content about at least one SRH-related topic (including STI prevention, pregnancy prevention, sexuality, sexual development, healthy relationships, sexual violence); and (3) content explicitly for adolescents and young adults. In addition, an eligible Web site had to be operated by a U.S.-based organization with a mission related to promoting health and/or providing clinical services based on the “About Us” or similar Web page. Any discrepancies between the two screeners regarding inclusion were resolved through discussion.

In total, 32 Web sites were eligible. We used a content selection protocol to create a single PDF for each Web site, including all pages of the Web site with informational content about SRH for young people. PDFs did not include videos, clinic locator information, birth control reminders, blogs, quizzes, and non-English-language content. Web site pages with health promotion content on other health topics (e.g., chronic conditions) and/or for other audiences (e.g., parents) were also not included. Additional details of our systematic process, including a flow diagram for Web site screening and supplemental information about search terms and inclusion criteria, are published elsewhere [15].

Confidentiality content identification

All PDFs were uploaded to MAXQDA, version 12.3 (VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany), and specific content about confidentiality was identified using the search function in MAXQDA. We searched each PDF for the following terms: confidential, priva (to capture privacy and private), anonymous, policy, law, notif (to capture notify, notified, and notification), and permission. The search process was iterative in that we started with a smaller number of terms and added additional keywords after reviewing identified content. We chose not to include “consent” as a keyword given that preliminary searches with this term primarily pulled in content about consent related to sexual activity, and content about parental consent was identified through the other search terms used. Certain content identified through keyword searches was excluded if it did not directly address confidentiality in the context of clinical health service provision (e.g., statements about certain birth control methods being private/not noticeable, information about STI-related partner notification). Of the 32 included Web sites included from the original study, 29 (91%) had content about confidentiality.

Analysis

We followed principles of thematic analysis to identify key qualitative themes from these data [17]. First, we created a codebook that included deductive codes based on existing literature on confidentiality. We included SRH topic codes (e.g., birth control, STIs, and pregnancy) and confidentiality message codes (e.g., consent, billing, and law/policy). All authors reviewed a subset of five Web sites to refine code definitions and identify inductive codes from the data. For example, the codes “action” and “resources” were added based on multiple messages encouraging specific actions adolescents should take to ensure confidentiality and the presence (or absence) of resources to do so. Two authors (R.J.S., S.P.) then double coded the remaining Web sites independently, resolving discrepancies through discussion. We reviewed coded content to identify themes and also examined descriptive statistics as appropriate to provide quantitative evidence in support of qualitative findings.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 lists the 29 Web sites with confidentiality-related content. Most of these Web sites were either operated by nonprofit education/advocacy organizations or local health systems or clinics, although most of these had a broader scope relevant to a national audience. Additional details about the sample, including the scope and audience for each Web site, is published elsewhere [15]. Of the almost 300 unique mentions of confidentiality, about one-third were statements that only advertised or encouraged use of confidential SRH (e.g., “there are places where you can get low-cost and confidential testing”), whereas the other two-thirds provided more detailed information about confidentiality, such as defining it or describing limitations. Themes that follow primarily relate to statements offering additional details about confidential services.

Table 1.

Included Web sites

| Web site URL | Operating organization |

|---|---|

| http://annexteenclinic.org/ | Annex Clinic |

| http://kidshealth.org/ | Nemours |

| http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/ | LA County Department of Public Health |

| http://stayteen.org/ | Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy) |

| http://teen411.com/home | Valley Community Healthcare |

| http://teenclinic.org/ | Boulder Valley Women’s Health Center |

| http://utteenhealth.org/ | University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio |

| http://www.acog.org/ | The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| http://www.advocatesforyouth.org/ | Advocates for Youth |

| http://www.emedicinehealth.com/script/main/hp.asp | WebMD |

| http://www.goaskalice.columbia.edu/ | Columbia University |

| http://www.helpnothassle.org/ | The Youth Project |

| http://www.iwannaknow.org/ | American Sexual Health Association |

| http://www.nysyouth.net/ | ACT Youth Network |

| http://www.pamf.org/ | Palo Alto Medical Foundation for Health Care, Research and Education (PAMF) |

| http://www.positive.org/Home/index.html | Coalition for Positive Sexuality |

| http://www.safeteens.org/ | Maternal and Family Health Services, Inc. |

| http://www.scarleteen.com/ | Scarleteen |

| http://www.summitmedicalgroup.com/ | Summit Medical Group |

| http://www.teenhealthrights.org/ | National Center for Youth Law |

| http://www.teensource.org/ | Essential Access Health |

| http://youngmenshealthsite.org/ | Boston Children’s Hospital |

| http://youngwomenshealth.org/ | Boston Children’s Hospital |

| https://sexetc.org/ | Answer |

| https://sites.google.com/site/mchdyouthsexualhealth/ | Mesa County Public Health Clinic |

| https://www.bedsider.org/ | Power to Decide (formerly The National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy |

| https://www.girlshealth.gov/ | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office on Women’s Health |

| https://www.plannedparenthood.org/ | Planned Parenthood Federation of America Inc. |

| https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/index.page | New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene |

Explicit definitions of confidentiality limited

About half (n=14; 48%) of the Web sites with information about confidentiality explicitly defined this concept (i.e., “confidentiality means…” or equivalent statements), and definitions centered on privacy of information, particularly in relation to parents. For example, one clinic Web site noted: “Confidential testing means that the health center won’t tell your parents or anyone else without your permission.” Definitions of confidentiality were more likely to be provided when distinguishing confidential from anonymous in the context of HIV testing. Of the 21 statements defining confidentiality, 57% (n=12) of them were provided in the context of HIV testing only.

Emphasis on notification and consent but not time alone

Even if not explicitly defining confidentiality, most Web sites (n=24; 83%) described it in relation to notification and/or consent. Such information focused on legal protections that limit parental notification and allow minors to consent for services without parental permission. Often these topics were addressed jointly. For example, one clinic noted: “the law states that minors can access reproductive health care services without parental notification or consent. That means it’s legal for you to take a pregnancy test, start a birth control method, or get tested for STIs without your parents knowing or agreeing to it.” Although law and policy were emphasized, only 31% of Web sites (n=9) explicitly stated that adolescents had a “right” to confidential care. Only 21% of Web sites (n=6) mentioned time alone with a provider when describing confidentiality practices. Most of these messages informed adolescents that they could request time alone (e.g., “you are allowed to ask your guardian who has accompanied you to the doctor to leave the room so that you may speak privately with your doctor.”). Only one Web site noted that young people may be uncomfortable with time alone.

Discussed primarily in relation to STI/HIV testing and contraception

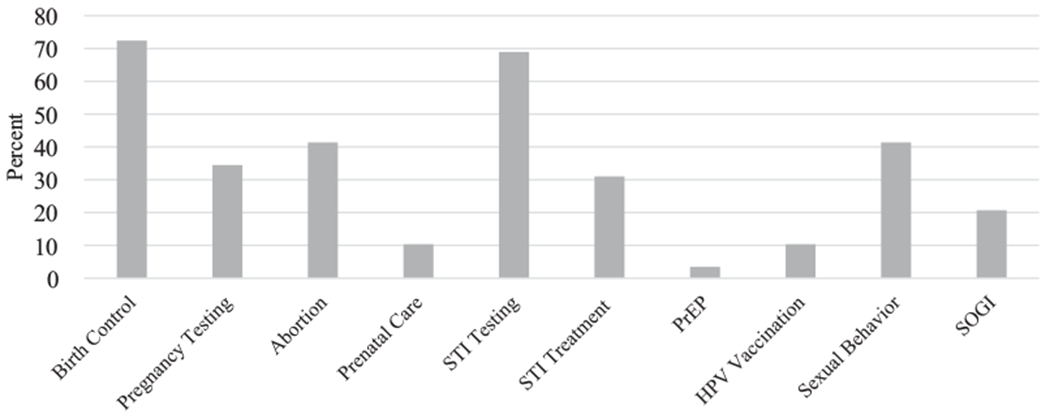

Perhaps because of the focus on notification and consent, confidentiality was predominately discussed in relation to STI/HIV (n=22 Web sites; 76%) and contraceptive services (n=21 Web sites; 72%) covered by minor consent laws (Figure 1). However, the STI/HIV content primarily focused on testing, with only about one-third of Web sites (n=9; 31%) describing STI/HIV treatment as a confidential service. Just a few sites discussed confidentiality in relation to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, for which legal protections vary based on whether a state considers this as an STI-related service. Only one site discussed HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and confidentiality, promoting “confidential clinics” in New York where young people could access PrEP. Less than half of Web sites (n=12; 41%) addressed confidentiality in relation to conversations with providers about sexual behavior (e.g., “What you tell your health care provider about your sexual behavior and exposure to STIs is confidential.”). Fewer sites mentioned this concept in relation to patient-provider discussions about sexual orientation (n=6; 21%) or gender identity (n=4; 14%).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Web sites with confidentiality content about specific sexual and reproductive health topics. STI = sexually transmitted infection; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis; HPV = human papillomavirus; SOGI = sexual orientation and gender identity.

Limitations to confidentiality not routinely discussed

Only half of Web sites (n=15; 52%) acknowledged potential breaches of confidentiality associated with billing, either directly and/or by offering actions young people could take to minimize potential billing-related confidentiality issues. Most of these statements focused on disclosure to parents, although in half of these instances it was not always clear how this would occur (i.e. explanation of benefits/insurance statements). This example from a nonprofit organization illustrates such content about billing: “Warning! If you use your parents’ insurance to pay for your visit, your parents may find out about it unless you take some additional steps.” Of the half of Web sites (n=14; 48%) that offered “additional steps,” to protect confidentiality, the most common recommendations were to pay for services in cash rather than use insurance, access a clinic where services are free or more affordable to avoid using insurance, or call the insurance company. Only a few sites (n=4; 14%) provided specific information about how to work with an insurance company to prevent breaches (e.g., completing a Confidential Communications Request available in the state of California, talking points for calling an insurance provider). Furthermore, less than half of Web sites (n=13; 45%) noted other limitations to confidentiality in the context of being a “danger to yourself or others,” with abuse and suicidality most often cited as specific examples.

Verification of confidentiality encouraged

In addition to recommending actions to minimize billing-related breaches, nearly 60% of Web sites (n=17; 59%) encouraged young people to verify confidentiality policies and practices within their state, at the clinic level, and/or with their provider. Of the eight Web sites that suggested that young people know their state’s confidentiality laws and policies, 88% (n=7) provided resources to consult. Two Web sites created a resource located within their site, whereas others referred to different Web sites. In contrast, statements encouraging young people to ask about clinic or provider policies (Box 1), such as “it’s important to ask your doctor or nurse what their office’s policies are,” generally did not include suggestions for how to have these conversations or what they should specifically address. Of the 11 Web sites with such messages, only about one-fifth (n=2; 18%) provided specific information to ask about, including whether parental consent is needed, what details are added to the medical record, and whether parents have access to the patient portal. Fourteen percent of Web sites (n=4) advised adolescents to tell providers what information they wanted kept private, implying that otherwise it would not be confidential. One Web site instructed teens to “send your doctor to [website]” if the provider was not aware of confidentiality rules.

Box 1. Example online messages encouraging adolescents to verify confidentiality.

Before making an appointment, ask a trusted adult at school about your school’s policies. Find out what you need to do to make sure what you tell them will be kept private.

When you call to make an appointment ask: Do you need to tell your parents or get their permission first?

If you are covered by your parents’ health insurance and/or they are billed for your medical visits, ask your provider if the diagnosis and treatment on bills sent to them may compromise your confidentiality and how to prevent that from happening.

There are some requirements associated with state laws that govern the confidentiality of health information for minors and thus [it is] important to ask situation-specific questions of the provider in advance.

Getting tested in a clinic can be quick, and some clinics offer free and/or anonymous testing. (Call ahead to find out.)

…it’s always a good idea to confirm the clinic’s confidentiality policy first when calling for an appointment.

If you are concerned about confidentiality, you and your doctor should talk about it before you answer any questions.

…be sure to share your worries with your doctor, who may be able to take extra steps to maintain your privacy.

When calling to make an appointment, tell your age, ask if you need parental consent for your visit and the method you want, and ask whether the clinic guarantees confidentiality.

…at your first appointment make sure to discuss confidentiality with your mental health provider and how and if information is shared with parents or others.

Ask your doctor or nurse what he or she plans to tell your parent about your exam and let them know if there’s anything you don’t feel comfortable sharing. Different states have different rules when it comes to patient confidentiality. If you’re worried about privacy, ask about the office policy when you call to make an appointment.

In general, parental permission is not needed for STD testing. However, there may be certain locations where, for one reason or another, a health care provider will require parental permission. Check with your provider about her or his policy.

Find out about what the health center offers to students, and make sure you receive confidential, non-judgmental services.

Many doctors and health clinics provide confidential services to women under age 18, but you may want to ask about their confidentiality policy to make sure.

Parent-adolescent communication promoted

For half of Web sites (n=16; 55%), content related to confidentiality also encouraged adolescents to talk with their parents. Such statements often came after describing confidentiality practices. For example, one Web site noted: “While you can access sexual and reproductive health services without getting your parents involved, getting support from your parents or another trusted adult can make that trip to the clinic a lot less intimidating.” In some cases, this information acknowledged that such conversations could be uncomfortable but challenged the assumption that parents would be unsupportive (e.g., “Many teens are surprised how supportive they [parents] can be”). A few Web sites (n=3) recommended that young people find a trusted adult or friend to speak to if they felt that talking to their parents was not an option.

Discussion

Adolescents’ low knowledge of confidentiality practices may create a barrier to health-care seeking and the delivery of recommended SRH services. Given the need for education on this topic, we conducted a systematic content analysis of public health/clinical Web sites to assess health education information about confidentiality in the context of SRH. It is promising that nearly all Web sites included in the original sample addressed confidentiality, particularly in terms of contraception and/or STI/HIV testing—two key preventive services for which there are specific legal protections in many states that are unknown to many adolescents [11]. However, content tended to focus narrowly on consent, notification, and, to some degree, billing-related breaches rather than consistently and comprehensively describing confidentiality practices, including time alone and other potential limitations. Notably, messages seemed to place an undue burden on adolescents to ensure that care is confidential, with few specific resources given. We highlight these limitations to inform ways to strengthen health education about confidential SRH care.

We found that only half of Web sites provided clear definitions of confidentiality. A specific concern is that only a few Web sites addressed time alone between adolescents and their providers, which is a necessary, albeit not sufficient, practice for confidential care. Perhaps, this finding reflects a lack of clinic-level policies and protocols in relation to time alone [18]. It is important to consistently provide comprehensive descriptions of confidentiality that include time alone, a topic particularly relevant for younger adolescents who may be learning to navigate health care with a limited degree of autonomy from parents. Evidence suggests that some may experience discomfort with time alone with a provider [12,19]; health education that introduces and normalizes this practice could help increase comfort. Addressing time alone also provides a potential opportunity to underscore the value of openly discussing sexual behavior and sexual orientation and gender identity with providers, topics not routinely addressed in the content we reviewed. In addition to emphasizing confidentiality practices in relation to providers and parents, definitions would also benefit from explicitly addressing other clinical staff who may be in the room during SRH visits, as well as peers, particularly given adolescents have concerns about being seen by their peers when accessing care [20–22].

Only half of Web sites noted limitations to confidentiality associated with billing, and even fewer discussed other restrictions. Inadvertent confidentiality breaches related to explanation of benefits have received particular attention in recent years [23,24], so it is promising to see this issue reflected in online content, which may not always be up to date. That said, it was not standard to describe the full range of potential limitations to confidentiality, including billing but also mandated reporting, certain SRH services that may require parental consent (e.g., HPV vaccination, PrEP), and state laws that allow minors to self-consent but do not prohibit subsequent parental notification. Advertising confidential services without addressing limitations may set adolescents up to expect a standard of care they do not receive, which could undermine trust in the healthcare system. Encouraging verification of confidentiality seemed to be one way that Web sites sought to temper expectations, but it may be preferable to clearly explain specific circumstances in which confidential care may not occur. Broadly implying that care may not be confidential has the potential to contribute to confidentiality-related concerns.

Across confidentiality content, messages emphasized actions adolescents should take to receive confidential care. Young people are expected to identify and understand state laws and policies related to minor consent, ask parents to leave the room to have time alone with the provider, verify whether services are confidential when scheduling appointments, call insurance companies or find alternative sources of care to avoid billing-related breaches, and even educate providers. Although it is useful to give concrete steps adolescents can take to maximize confidentiality, placing the burden on adolescents may be overwhelming and deter health-care seeking.

Such a consequence is of particular concern if resources to facilitate adolescent action are not offered, which we found to be the case in multiple instances. For example, adolescents were encouraged to verify confidentiality policies when scheduling an appointment. However, they may not be comfortable or know what to ask, especially with only a cursory understanding of confidentiality practices and restrictions. Providing example questions for young people to ask providers or clinic staff, as several Web sites did, may be useful, although doing so does not address the fact that not all staff will have adequate knowledge to respond appropriately to such queries [25,26]. We did find that most Web sites encouraging verification of state laws and policies provided specific resources to do so, such as linking to the Guttmacher Institute’s compilation of state laws related to consent and notification [6]. In contrast, recommendations to seek free sources of care to avoid billing-related issues were not usually accompanied by specific referrals. Providing clinic names and locations may not be feasible as standard practice, given that many Web sites are operated by national organizations, and content can be viewed across geographic locations. However, referencing national directories for free/low-cost services, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s STD/HIV testing locator [27], may be one option.

A particularly positive finding was the repeated emphasis on parent-adolescent communication in the context of confidentiality. Such messages align with professional medical organization recommendations and growing attention to parent-adolescent-provider interactions that can support adolescent health [2,28,29]. Routine adolescent communication with parents is associated with reductions in sexual risk behaviors [30] and may alleviate parental concern about confidentiality practices, such as time alone, by helping parents continue to feel involved.

These findings should be interpreted in the context of study limitations. It is unclear how many adolescents viewed the content we analyzed or how young people interpret it. In particular, we focused on public health and clinical Web sites identified through keywords, but research suggests that adolescents often search questions or phrases that may yield Web sites such as Wikipedia [31]. Our study was also limited to SRH content despite the fact that confidentiality is relevant to adolescent health more broadly. Even within SRH content from public health/clinical organizations, we reviewed a sample of Web sites; although systematic, our search process was not exhaustive. For example, because the parent study aimed to assess integration of STI prevention context with information about pregnancy prevention, we did not search for Web sites using STI-related search terms, such as condoms or specific STI names, to minimize selection bias. Procedures for identifying confidentiality messages within the identified Web sites may also have missed relevant content. Finally, PDFs of the Web sites were created in Summer 2017, and content may have changed since then.

Our analysis suggests that a fundamental challenge to educating young people about confidentiality is the complexity of the message. Considering the strengths and weaknesses of the content reviewed, it seems the goal should be to empower adolescents with comprehensive information and assurances about confidentiality practices and legal protections while also addressing limitations to confidentiality in a way that does not create an undue burden or reinforce or exacerbate confidentiality concerns. From a structural standpoint, health education may need to devote more space/time to this topic to appropriately cover these multiple dimensions. Specifically, in the case of online content, organizations with existing Web sites could add a stand-alone Web page devoted to confidential care in addition to brief statements integrated with other SRH topics. In addition, it seems that there is an opportunity for a national organization to develop a Web site devoted to confidentiality. Doing so would allow for a more comprehensive, nuanced presentation of information, and other sites that cursorily address confidentiality could direct viewers to such a resource for further details. In terms of framing, describing legal protections in terms of adolescents’ “right” to confidential care offers an empowering message that would also allow for describing specific and, in many states, fairly narrow restrictions to that right rather than broadly implying adolescents may not receive confidential care. In addition, tailoring confidentiality messages so they are aligned with adolescent development may facilitate comprehensive discussions of time alone and minor consent/parental notification. For example, time alone is a particularly salient practice for younger adolescents. Health communications research could help explain how young people are interpreting current messages and elicit innovative ways to both structure and frame confidentiality-related information going forward.

Ultimately, young people deserve to have clear, comprehensive information about confidential SRH services. Drawing on our findings, public health and medical organizations and professionals can consider how to improve health promotion about confidentiality, whether online or in the context of school-based efforts or clinic-based counseling. Doing so in conjunction with initiatives to address provider and clinic-level barriers to confidentiality could go a long way toward strengthening adolescent SRH care.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

This study systematically assessed confidentiality-related information provided by public health/clinical organizations in the context of sexual and reproductive health. Strengthening these messages, whether delivered online or through school-or clinic-based education, could help improve adolescent knowledge of confidentiality practices and reduce a known barrier to care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eric Buhi and Rachel Kachur for thoughtful discussions on the search strategy, and Deb Levine, Melissa Kottke, Fred Wyand, and Maria Trent for providing input on the included Web sites. They also appreciate Retze Fabre with pdfmyurl.com for providing technical assistance on data management and Jaimie Shing for her research assistant support. Findings from this study were presented at the 2018 STD Prevention Conference in Washington, D.C.

Funding Source

This work was supported by Emory University Professional Development Support Funds and Letz Funds from Emory University’s Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- [1].American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Achieving quality health services for adolescents. Pediatrics 2016;132:138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ford C, English A, Sigman G. Confidential health care for adolescents: Position paper for the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health 2004;35:160–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Leichliter JS, Copen C, Dittus PJ. Confidentiality issues and use of sexually transmitted disease services among sexually experienced persons aged 15-25 years - United States, 2013-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:237–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thrall JS, McCloskey L, Ettner SL, et al. Confidentiality and adolescents’ use of providers for health information and for pelvic examinations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:885–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ford CA, Millstein SG, Halpern-Felsher BL, et al. Influence of physician confidentiality assurances on adolescents’ willingness to disclose information and seek future health care. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1997;278:1029–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Guttmacher Institute. An overview of minors’ consent laws. 2018. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-minors-consent-law. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- [7].Adams SH, Park MJ, Twietmeyer L, et al. Association between adolescent preventive care and the role of the affordable care act. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172:43–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Copen CE, Dittus PJ, Leichliter JS. Confidentiality concerns and sexual and reproductive health care among adolescents and young adults aged 15-25. NCHS Data Brief 2016:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lim SW, Chhabra R, Rosen A, et al. Adolescents’ views on barriers to health care: A pilot study. J Prim Care Community Health 2012;3:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Loertscher L, Simmons PS. Adolescents’ knowledge of and attitudes toward Minnesota laws concerning adolescent medical care. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2006;19:205–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lyren A, Kodish E, Lazebnik R, et al. Understanding confidentiality: Perspectives of African American adolescents and their parents. J Adolesc Health 2006;39:261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kadivar H, Thompson L, Wegman M, et al. Adolescent views on comprehensive health risk assessment and counseling: Assessing gender differences. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ginsburg KR, Forke CM, Cnaan A, et al. Important health provider characteristics: The perspective of urban ninth graders.J Dev Behav Pediatr 2002;23:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].KaiserFamily Foundation. Sexual health ofadolescents and youngadults inthe United States. 2014. Available at: http://kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/sexual-health-of-adolescents-and-young-adults-in-the-united-states/. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- [15].Steiner RJ, Rasberry CN, Sales JM, et al. Do health promotion messages integrate unintended pregnancy and STI prevention? A content analysis of online information for adolescents and young adults. Contraception 2018;98:163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Search Engine Land. Google stillworld’s mostpopular search engine by far, but share of unique searchers dips slightly. 2013. Available at: https://searchengineland.com/google-worlds-most-popular-search-engine-148089. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- [17].Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pampati S, Steiner RJ, Liddon N, et al. Provider and clinic factors influencing the implementation of STI/HIV-related services: A narrative review. STD Prevention Conference. Washington DC, August 27–30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [19].McKee MD, O’Sullivan LF, Weber CM. Perspectives on confidential care for adolescent girls. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:519–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Blake DR, Kearney MH, Oakes JM, et al. Improving participation in Chlamydia screening programs: Perspectives of high-risk youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003;157:523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rose ID, Friedman DB. Schools: A missed opportunity to inform African American sexual and gender minority youth about sexual health education and services. J Sch Nurs 2017;33:109–15.28288553 [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lindberg C, Lewis-Spruill C, Crownover R. Barriers to sexual and reproductive health care: Urban male adolescents speak out. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs 2006;29:73–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine; American Academy of Pediatrics. Confidentiality protections for adolescents and young adults in the health care billing and insurance claims process. J Adolesc Health 2016;58:374–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].English A, Summers R, Lewis J, et al. Confidentiality, third-partybilling,&health insurance claims process: Implications for title X. 2015. National Famiy Planning & Reproductive Health Association. Available at: https://www.confidentialandcovered.com/file/ConfidentialandCovered_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hyden C, Allegrante JP, Cohall AT. HIV testing sites’ communication about adolescent confidentiality: Potential barriers and facilitators to testing. Health Promot Pract 2014;15:173–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Akinbami LJ, Gandhi H, Cheng TL. Availability of adolescent health services and confidentiality in primary care practices. Pediatrics 2003;111:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Get tested. Available at: https://gettested.cdc.gov/. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- [28].Ford CA, Davenport AF, Meier A, et al. Partnerships between parents and health care professionals to improve adolescent health. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dittus PJ. Promoting adolescent health through triadic interventions. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:133–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, et al. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Buhi ER, Daley EM, Fuhrmann HJ, et al. An observational study of how young people search for online sexual health information. J Am Coll Health 2009;58:101–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]