STRATEGIES OF OSMOADAPTATION IN ARCHAEA

The ability to adapt to fluctuations in external osmotic pressure (osmoadaptation) and the development of specific mechanisms to achieve this (osmoregulation) are fundamental to the survival of cells (6, 16, 67, 73, 76). Most cells maintain an osmotic pressure in the cytoplasm that is higher than that of the surrounding environment, resulting in an outward-directed pressure, turgor, whose maintenance is essential for cell division and growth. Changes in environmental osmolarity can trigger the flux of water across the cytoplasmic membrane. Thus, to avoid lysis under low-osmolarity or dehydration under high-osmolarity growth conditions, cells must possess active mechanisms that permit timely and efficient adaptation to changes in environmental osmolarity.

Eubacterial organisms have evolved several strategies that enable them to survive and proliferate in environments of varied ionic composition and salinity ranging from freshwater to hypersaline habitats: (i) the intracellular accumulation of inorganic ions such as potassium; (ii) the evolution of salt-tolerant (and in some cases salt-dependent) enzymes; and (iii) the accumulation, either by transport or synthesis, of selected organic molecules which may be negatively charged (and act as counterions for intracellular K+) or neutral. Accumulation of “compatible” solutes is a particularly ubiquitous response. The current understanding is that these compatible solutes maintain an equilibrium between macromolecule surface areas and the water phase by resisting drastic changes in intracellular water density. This is based on the ability of compatible solutes to accumulate at these interface regions (75). For example, the preferential hydration of ribonuclease is 600 mol of water per mol of protein. However, in the presence of sarcosine, a common osmolyte in eukaryotic organisms, the preferential hydration is reduced to 70 mol of water per mol of protein (51). These same solutes also protect macromolecules from thermal denaturation (e.g., glycine-based osmolytes provide an extraordinary degree of protection for hen egg white lysozyme [64]). Protein unfolding results in an increase of total protein surface area. Osmolytes oppose the increase in surface area by a preferential hydration of proteins (1) and favorable interactions with side chains (53). These interactions stabilize proteins by raising the chemical potential of the denatured protein, which leads to contraction of the random coil to a folded structure (53). A recent study quantifying the stability afforded by compatible solutes showed that the osmolyte trimethylamine oxide can increase the population of folded structures compared to denatured protein by nearly 5 orders of magnitude (3).

Archaea, which are often found in high-salt as well as high-temperature environments, use the same general strategies for osmoadaptation as eubacterial and eukaryotic organisms. However, they are notable for the unusual organic osmolytes accumulated. Specific examples of these osmolytes and factors that affect their accumulation are provided in the following sections.

Accumulation of inorganic ions. The ubiquity of K+ uptake systems in cell membranes, their high rates for ion transport, and the ability to gate this ion flow might, at first glance, make K+ a good candidate for use as an osmolyte in cells. Balanced against this is the observation that high concentrations of inorganic cations often have deleterious effects on enzyme catalytic rates (76). In most eubacteria, the accumulation of K+ is an early response to an increase in external NaCl. Glutamate is usually selectively accumulated as the counterion (2, 8). However, the increased K+ is often transient and is superseded by the accumulation of zwitterionic organic solutes such as proline or glycine betaine (GB) (16). Thus, osmoadapted eubacteria tend to use zwitterionic or nonionic solutes to counteract external osmotic pressure.

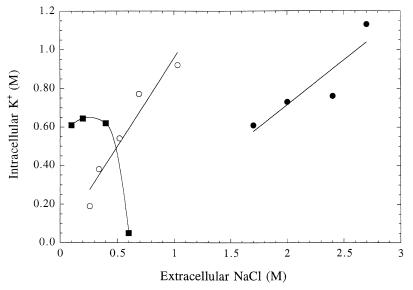

In contrast to eubacteria, most of the archaea examined have high intracellular concentrations of inorganic cations, primarily K+, under optimal growth conditions. Table 1 provides values for intracellular K+ concentrations in a range of archaea including organisms grown in low-ionic-strength media (e.g., Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum) and extreme halophiles (e.g., Halobacterium halobium and Natronococcus occultus). Even in the nonhalophiles the intracellular K+ concentration is relatively high (>0.5 M), suggesting that under normal conditions these cells exist with high turgor pressure if the intracellular K+ is free and not tightly complexed to macromolecules. While there are no published data on whether there are immediate changes in intracellular K+ levels with increased external NaCl, steady-state intracellular K+ levels have been measured in cells grown at different NaCl concentrations (for examples, see Fig. 1). In many of the halotolerant methanogens (e.g., Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus [grown in medium with less than 1 M external NaCl], Methanogenium cariaci, and Methanosarcina thermophila) and the halophilic Methanohalophilus portucalensis, intracellular K+ varies with external NaCl concentration, and hence it can be considered an osmolyte. In other methanogens (e.g., Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum), it is maintained at a constant level over a moderate range of external NaCl and contributes to high turgor pressure (15). However, in both M. thermolithotrophicus and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum there appear to be thresholds of external NaCl above which K+ accumulation (and organic counterion accumulation as well) is compromised and is seen to decrease (13, 60). At this point, if the cell is to survive (i.e., resist water efflux and dehydration) it must alter its osmoadaptation strategy. Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum is unable to adapt effectively and does not grow at high concentrations of NaCl, while M. thermolithotrophicus alters its osmolyte pool and thus can survive and grow in medium containing higher concentrations of NaCl.

FIG. 1.

Intracellular K+ as a function of external NaCl in M. thermolithotrophicus (○) (data are from reference 60 [micromoles/milligram of protein] and were converted to moles/liter by using the conversion that 0.13 μmol of solute/mg of protein corresponds to 0.1 M as determined in reference 15), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (■) (data from reference 13), and Methanohalophilus portucalensis (●) (data are from reference 36).

The highest accumulation of K+ among the archaea occurs within the halophilic family Halobacteriaceae (30). It has been reported that some Halobacterium spp. possess up to 5 M cell-associated K+, which is well beyond the solubility of KCl. This suggests that K+ is somehow bound to macromolecules in the cells, but analysis by 39K-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has indicated that the bulk of the K+ exists in a free state within these cells (66). For other Halobacterium spp., intracellular Na+ can be exchanged for K+, creating an intracellular environment that has reduced K+ and Na+ gradients (34) but which still maintains a very high monovalent cation concentration inside. The concentration of intracellular K+ need not be the same as that of extracellular Na+ in extreme halophiles. For example, N. occultus grows optimally in medium containing 3.4 M NaCl; the concentration of intracellular K+ in this organism is 1.1 M (18). Likewise, in Methanohalophilus portucalensis grown in 2.0 M NaCl, the intracellular concentration of K+ is 0.76 M (36). Presumably the cytosolic environment of these cells has other components that are effective at balancing external osmotic pressure.

Salt-tolerant enzymes. To cope with the high intracellular concentrations of K+, many archaea have evolved proteins that are exceedingly rich in acidic amino acids (glutamate and aspartate) compared to basic amino acid (arginine and lysine) residues (29). For example, the relative acidities of ribosomal proteins have been compared for a variety of archaea (primarily methanogens) and some eubacteria (29). Even archaea grown in low salt medium have acidic protein fractions (Table 2). The bias for acidic residues results in a net negative charge on the protein surface that presumably prevents folding into the native (active) structure unless a cation counterion like K+ is present. For example, malate dehydrogenase from H. halobium (67) requires high salt concentrations in order to maximize activity. In addition to this large excess of negatively charged amino acid residues, the hydrophobicity of the proteins of halophilic archaea is reduced. This in turn reduces the salting-out effects of K+ and allows the protein to retain its flexibility under conditions of extreme salinity. However, the requirement for K+ for proper protein folding and stability imposes a limit on the effectiveness of K+ as a compatible solute (76).

Accumulation of organic solutes. Eukaryotic and eubacterial organisms generally adapt to increased osmotic stress by accumulating highly soluble organic compounds such as polyols (glycerol, arabitol, mannitol, and glucosylglycerol [6, 24]), low-molecular-weight nonionic carbohydrates (sucrose, trehalose, and glucose [28, 74]), free amino acids and their derivatives (proline, glutamate, glycine, γ-aminobutyrate, taurine, and β-alanine [8, 16]), unique organic zwitterions (tetrahydropyrimidines such as ectoine [25]), methylamines (GB and trimethylamine-N-oxide [67]), and β-dimethylsulfoniopropionate (71). In general, intracellular accumulation of organic solutes by transport from the culture medium is often preferred over their biosynthesis, and indeed, for certain solutes such as GB, high-affinity uptake systems are available to scavenge any of the material present in complex media.

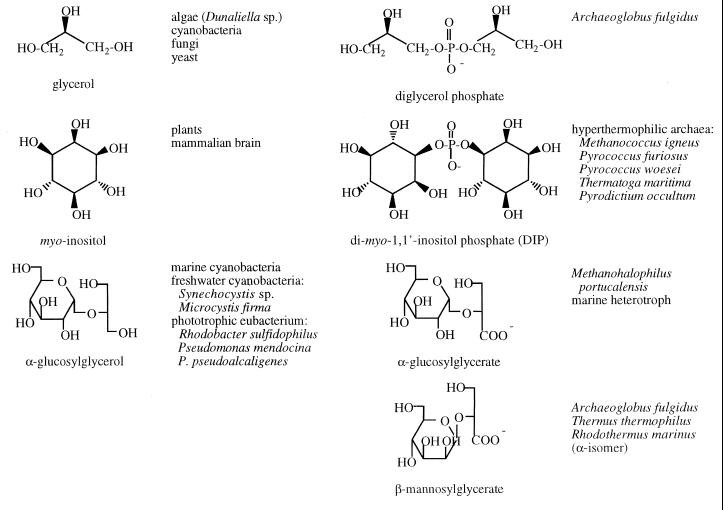

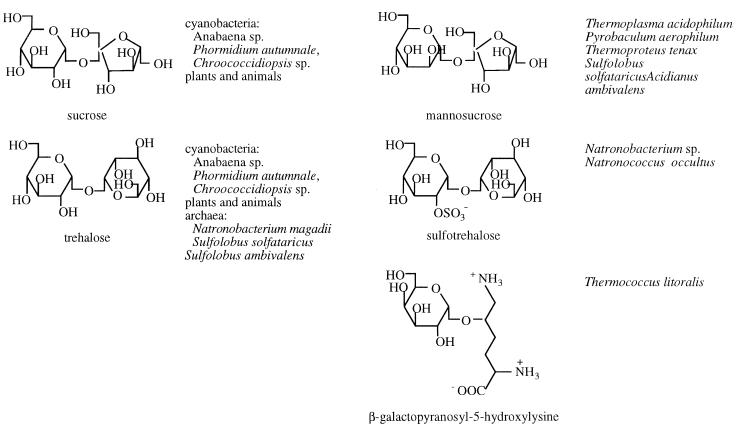

The distribution of commonly occurring organic osmolytes found in archaea falls into the same major classes as for eubacteria and eukaryotes: (i) sugars and polyhydric alcohols (Table 3) and (ii) amino acids and derivatives including methylamines (Table 4). Archaea also accumulate some very unusual solutes that have no obvious eubacterial or eukaryote counterpart (Table 5). There are striking similarities among the carbohydrates and polyols that are used as osmolytes by eubacteria and archaea (Table 3) with the exception that the majority of the solutes in archaea are modified so that they are anionic. The addition of a negative charge is accomplished with carboxylate, phosphate, and sulfate groups. In the amino acid class, there are two osmolytes common to eubacteria and archaea: anionic l-α-glutamate and zwitterionic GB. However, methanogenic archaea have developed a novel strategy to produce amino acid-like molecules that are unlikely to interact with any metabolic or biosynthetic machinery in the cells. These anaerobic organisms synthesize and accumulate several β-amino acids to balance external osmotic stress (Table 4). β-Glutamate is the anionic solute in this group with β-glutamine and Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine as zwitterionic solutes.

(i) Sugars and polyhydric alcohols.

Accumulation of polyol phosphodiesters represents a relatively unique osmolyte strategy in archaea. Glycerol is accumulated in response to external NaCl concentrations by several species of yeast and algae (6, 67, 73). The hyperthermophile Archaeoglobus fulgidus accumulates a novel charged version of this compound, diglycerol phosphate (DGP), as its major intracellular organic solute (44). In osmoadapted cells, DGP increases with both increased NaCl and growth temperature, indicating that it behaves as an osmolyte in this organism. Another common polyol used by plants and mammals for osmotic balance is myo-inositol. Archaea use a related phosphorylated inositol, di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate (DIP), for osmotic balance. This rather unusual phosphodiester compound has been identified in hyperthermophilic organisms, including Methanococcus igneus (12), Pyrococcus woesei (65), P. furiosus (42), Thermotoga maritima (43), and Pyrodictium occultum (44). T. maritima is not an archaeon but shares many characteristics with archaeal hyperthermophiles. Both inositol rings of the DIP from M. igneus and Pyrococcus sp. have l-stereochemistry; DIP isolated from T. maritima is reported to occur in chiral and meso-forms. While intracellular DIP concentrations increase in M. igneus with external NaCl, other solutes, notably β-glutamate, show a stronger increase with increasing NaCl (12, 43). Perhaps more strikingly, DIP levels also correlate with hyperthermophily. The optimal growth temperature of M. igneus is 85°C. In this organism, DIP is produced only at growth temperatures of 80°C or higher (12). This trend was also seen with P. furiosus, where the concentration of DIP was found to be higher at supraoptimal growth temperatures (98 to 101°C) and with Thermotoga neapolitana (43). These results suggest the possibility of DIP acting as a preferred thermoprotectant in addition to its role as an osmolyte.

Anionic carbohydrates that are derivatives of common eubacterial and eukaryotic osmolytes have also been found in archaea (Table 3). In each case the carbohydrates used for osmotic balance are ones where the reducing end of the sugar is involved in a glycosidic bond or is otherwise modified. High intracellular concentrations of reducing sugars could result in nonenzymatic glycation of a wide spectrum of macromolecules (23) with severe physiological consequences (48). This would be enhanced at high growth temperatures. To avoid these detrimental reactions, cells modify the reducing end of sugar moieties (e.g., by the formation of trehalose, glucosylglycerol, or glucosylglycerate) to abolish its reactivity.

Glucosylglycerol is a dominant organic osmolyte that accumulates in cyanobacteria in response to increased salinity (19, 41, 55). It is also used by other eubacteria when appropriate precursors are present in growth media. Glucosylglycerate, a negatively charged structural analogue of glucosylglycerol, has been identified at moderate concentrations in methanogenic archaea and is synthesized under nitrogen-limiting conditions in Methanohalophilus portucalensis, an extreme halophile. However, its concentration does not vary as a function of external NaCl concentration (58). Related molecules in archaea include the anionic solutes β-mannosylglycerate and mannosyl-DIP (43).

Trehalose, a nonreducing glucose disaccharide, is frequently found in organisms subject to dehydration. This disaccharide occurs at high levels in Pyrobaculum aerophilum and at lower levels in several other thermophilic archaea (44). Trehalose synthesis is favored in Sulfolobus solfataricus when it is grown on glucose as the energy and carbon source (49). In a related organism, Sulfolobus acidocalarius, the genes for the three enzymes for trehalose biosynthesis (i.e., those encoding maltooligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase, glycogen-debranching enzyme, and maltooligosyltrehalose synthase) have been cloned (45). A negatively charged version of this solute, 2-sulfotrehalose, exhibits osmotic behavior in the halophilic, alkaliphilic archaea Natronococcus and Natronobacterium spp. (18). Sulfotrehalose, a 1→1 α-linked glucose disaccharide with a sulfate group attached to one of the glucose moieties at the C-2 position, is the first sulfated sugar synthesized and accumulated as a compatible solute in any organism. In N. occultus, the intracellular concentration of sulfotrehalose provides the charge balance for intracellular K+. Sulfate groups occur in biological molecules in both carbohydrate (e.g., heparin sulfate, which contains bis-sulfated glucosamine and sulfated N-acetylglucosamine) and lipid (e.g., sulfated triglycosylarchaeol) pools (46). In both cases the sulfate is esterified to the appropriate hydroxy group by a sulfotransferase with 3-phosphoadenosine-5′ phosphosulfate as the activated sulfate donor. In the case of Natronobacteria, sulfotrehalose biosynthesis may be linked to glycolipid biosynthesis since a number of sulfated carbohydrates have been detected in the glycolipids of archaeal halophiles (35, 72). Since intracellular sulfotrehalose levels respond to external NaCl, linking osmolyte enzymology with membrane components might generate a useful regulatory scheme.

Another unusual solute accumulated by archaea as an osmotic response is β-galactopyranosyl-5-hydroxylysine (38). This unusual compound has been detected in Thermococcus litoralis. However, it is not synthesized de novo and is thought to be internalized from the peptone in the growth medium.

(ii) α-Amino acids and derivatives.

Zwitterionic amino acids, such as proline, are important osmoprotectants in a variety of bacteria. These are usually internalized from the medium by osmotically induced proline transport systems, ProP and ProU (67), that have been shown to be sodium dependent (27). To date there are no reports of proline being accumulated in response to osmotic stress in archaea. Another relatively common eubacterial zwitterionic osmolyte is the cyclic amino acid derivative ectoine. Ectoine is synthesized de novo by the majority of heterotrophic halotolerant eubacteria under conditions of high salt (17, 24, 25) and is assumed to have a protective function similar to those of proline and GB (31). However, ectoine has not been detected in archaea.

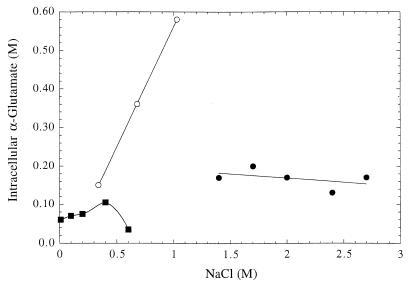

The one amino acid commonly used as an osmolyte in all types of organisms is l-α-glutamate (Table 4). l-α-Glutamate is also a precursor and a nitrogen donor for the biosynthesis of several amino acids. In eubacteria the accumulation of this amino acid can occur by transport or by de novo synthesis. Archaea also use l-α-glutamate for osmotic balance with patterns similar to those seen in eubacteria. l-α-Glutamate is often accumulated in cells grown in suboptimal NaCl-containing medium. For example, the haloalkaliphilic archaeon N. occultus accumulates glutamate when grown in a defined medium with a NaCl concentration less than 3.0 M, where its optimum NaCl is 3.4 M (18); this is supplanted by sulfotrehalose at higher NaCl concentrations. l-α-Glutamate is present at moderate concentrations (>0.02 M) in most methanogens, although in some cases its concentration does not vary strongly with external salt concentrations. For example, the l-α-glutamate concentration in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum grown in medium with no added NaCl is 0.60 M; increasing the concentration of external NaCl to 0.4 M (a rather large change) induces a relatively small increase in the concentration of l-α-glutamate to 0.10 M (Fig. 2) (13). Many thermophilic methanogens (e.g., M. thermolithotrophicus and M. igneus) synthesize and accumulate glutamate when grown on a defined inorganic medium; as shown in Fig. 2 for M. thermolithotrophicus, the l-α-glutamate concentration in these organisms varies linearly with that of external NaCl. At 1.0 M external NaCl, the l-α-glutamate concentration is ∼0.60 M. However, studies of the halotolerant, moderately halophilic, and extremely halophilic methanogens, including several Methanohalophilus strains (36), all showed moderate concentrations of glutamate which were relatively invariant with external NaCl (Fig. 2). Since glutamate is a substrate for a variety of cellular enzymes, its concentration in osmoadapted archaea may be constrained with certain limits.

FIG. 2.

l-α-Glutamate levels in M. thermolithotrophicus (○) (data are from reference 60 [micromoles/milligrams of protein] and were converted to moles/liter by using the conversion that 0.13 μmol of solute/mg of protein corresponds to 0.1 M as determined in reference 15), Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (■) (data from reference 13), and Methanohalophilus portucalensis (●) (data from reference 36).

GB, a trimethylated derivative of the amino acid glycine, is found widely in nature and is accumulated to balance osmotic pressure in species as distantly related as enterobacteria, plants, and humans. GB has been adopted by a wide variety of organisms as an efficient osmoprotectant in high-osmolarity environments (20, 39). The majority of these organisms, including most archaea (61), lack the ability to produce GB de novo and transport it from the external medium. Several methanogens, notably Methanogenium cariaci (60), Methanosarcina thermophila (69), and Methanohalophilus portucalensis (36), will preferably scavenge GB from the medium and suppress de novo synthesis of other osmolytes. The kinetic properties of GB transport in Methanosarcina thermophila have been examined in some detail (52). This transporter is very specific for GB (glycine, choline, sarcosine, and N,N-dimethylglycine do not compete effectively with GB for transport into the cell), and transport could be abolished by protonophores and ionophores. Methanohalophilus portucalensis appears to have a similar high-affinity betaine transporter (37a). De novo synthesis of GB is rarer and there are two routes known, each of which has been detected in archaea: (i) oxidation of exogenous choline (GB aldehyde is an intermediate) and (ii) methylation of glycine. The first pathway is used by a few nonhalophilic organisms (4, 32) and one nonhalophilic methanogen, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum Marburg (13). The second pathway for betaine synthesis is found in halophilic eubacteria (e.g., Ectothiorhodospira halochloris [50] and cyanobacteria [41, 55]) and in the archaeon Methanohalophilus portucalensis (36, 56).

(iii) β-Amino acids and derivatives.

Several β-amino acids, notably β-glutamate, β-glutamine, and Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine (Table 4), function as compatible solutes in methanogenic archaea (36, 56–60, 62, 68, 69). β-Glutamate (β-aminoglutaric acid), an organic anion, accumulates in response to increasing external NaCl in several halotolerant thermophilic Methanococcus species (12, 60) as well as in mesophiles (e.g., Methanogenium cariaci, a marine methanogen [60]). A zwitterionic derivative, β-glutamine, functions as the osmolyte of choice at the highest external NaCl concentrations in several Methanohalophilus species (36, 63). A rather different zwitterionic β-amino acid derivative, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, occurs as the predominant compatible solute in response to elevated external NaCl levels in various methanogenic archaea isolated from both marine and nonmarine origins (e.g., Methanosarcina thermophila, Methanogenium cariaci, Methanohalophilus sp., and Methanococcus sp. [36, 58, 60, 68, 69]). Like their l-α isomers, the β-amino acids are extremely soluble, but they are not metabolized significantly by cells. The stability of β-amino acid pools to turnover has been shown by NMR analyses of 13C-pulse/12C-chase (or 15N-pulse/14N-dilution) labeling experiments (56, 60). In these experiments, isotope in l-α-glutamate pools is rapidly lost as this solute is used to synthesize other amino acids and proteins, etc., while label in the β-amino acids turns over very slowly in growing cultures. This property makes the β-amino acids true compatible solutes.

Methanohalophilus portucalensis provides an interesting example of an organism that synthesizes and accumulates zwitterionic amino acids (GB, β-glutamine, and Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine) to counteract osmotic stress. Under adapted conditions, all three compounds (the α-amino acid derivative and the two β-amino acids) are poorly metabolized by the cells (56) and hence are excellent compatible solutes. However, any rationale for why three zwitterionic amino acids are synthesized and accumulated is lacking.

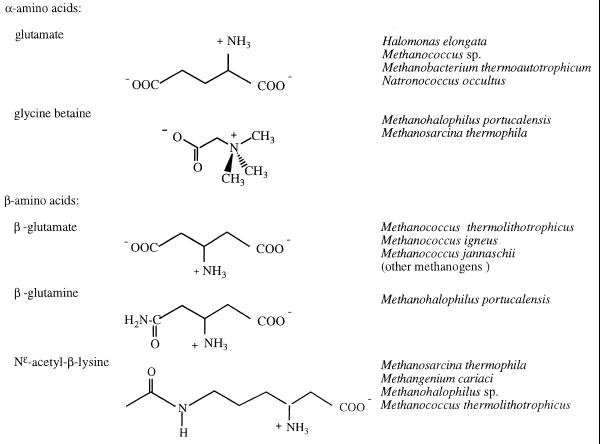

(iv) Miscellaneous osmolytes: cDPG and TCH.

Several other unusual compounds have been detected at moderate to high concentrations in archaea. These organic polyanions are counterions to the high intracellular K+ concentration and contribute to the high turgor pressure of the organisms in which they occur. As noted before, the thermophile Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum has a high intracellular K+ concentration that is relatively independent of external NaCl up to 0.4 M NaCl (see Fig. 1). The cell wall of this organism is extremely robust and is critical for maintaining cell volume under conditions where the organism is clearly not osmotically balanced. Both the Marburg and ΔH strains of this species have similar growth requirements (5). However, they balance the high K+ by using different ratios of organic polyanions (13). In Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH, the major intracellular solutes are cyclic-2,3-diphosphoglycerate (cDPG) and l-α-glutamate; 1,3,4,6-tetracarboxyhexane (TCH) is a minor component (for structures see Table 5). In the Marburg strain TCH levels are considerably higher, and the level of this solute increases in response to decreased levels of l-α-glutamate and other solutes with increased external NaCl. Since TCH has a −4 charge and cDPG has a −3 charge at physiological pH, the intracellular concentrations of these anions are far lower than that of intracellular K+. None of these anionic organic solutes exhibits a large osmotic response over a wide range of external NaCl concentrations (0.01 to 0.4 M); the total concentration of negative charges on the solutes correlates directly with the K+ concentration (13). Both K+ and organic solute concentrations begin to decrease between 0.4 and 0.65 M NaCl. The observation of these novel solutes in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum connects other cellular processes to maintenance of turgor pressure (and K+ charge balance). cDPG has been shown to be involved in carbon fixation in this organism (26). High levels of cDPG have also been detected in other more thermophilic methanogenic archaea, including Methanopyrus kandleri and Methanothermus fervidus (44), where it is likely to have a role as an osmolyte and a counterion to intracellular K+. TCH, as a structural unit of methanofuran, connects osmotic effects and/or turgor pressure with methanogenesis components in these organisms (26).

BIOSYNTHESIS OF OSMOLYTES

A detailed understanding of the osmotic behavior of archaea (or any organism for that matter) requires knowledge of the biosynthetic pathways or uptake systems for osmolytes and how they are linked to external NaCl. A number of the osmolytes used by archaea are novel compounds and as such present new wrinkles in standard biochemistry and in some cases novel enzymatic transformations. Several of these are discussed below with comments on which steps in a given pathway are the most likely to be regulated or affected by external NaCl.

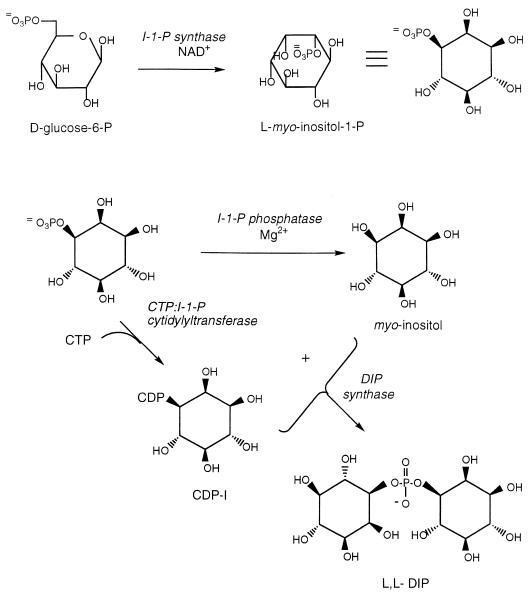

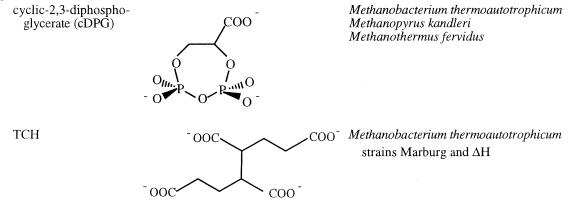

Conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to DIP: novel enzymes, novel compounds, and high temperatures. DIP biosynthesis in M. igneus (and presumably the other hyperthermophilic archaea where it occurs) consists of the following four steps (9) starting with d-glucose 6-phosphate (Fig. 3): (i) conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to l-myo-inositol-1-phosphate (I-1-P) by I-1-P synthase; (ii) conversion of I-1-P to myo-inositol by a specific phosphatase, I-1-P phosphatase; (iii) conversion of I-1-P to cytidine diphosphoinositol (CDP-I) with CTP as the carrier molecule in the phosphoryl transfer of the CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase reaction, and (iv) nucleophilic attack of the free hydroxyl group of C-1 of myo-inositol on CDP-I to produce DIP (DIP synthase). Steps i and ii have been elucidated in detail for plants and other organisms. Analogs of step iii occur in many cells as part of phospholipid biosynthesis, although this is not the way phosphatidylinositol is synthesized in cells (CDP-diacylglycerol is the activated species). Step iv, the novel DIP synthesis reaction, is based on phosphatidylinositol synthesis in both eukaryotic and bacterial cells with myo-inositol attacking CDP-I instead of the CDP-diacylglycerol. The enzymatic steps unique to DIP and not to inositol lipids are the CTP:I-1-P cytidylyltransferase and DIP synthase reactions. Thus, one might suggest that these would be steps sensitive to external osmotic pressure.

FIG. 3.

Biosynthetic pathway proposed for DIP (adapted from reference 9).

Archaea include a large number of hyperthermophiles, and these are often isolated from environments with moderate to high concentrations of NaCl. Whereas growth temperature appears to have little effect on the accumulation of amino acid type osmolytes, it can have a large impact on synthesis and accumulation of sugar and polyol solutes. The effects of growth temperature on DIP biosynthesis in M. igneus have been explored in detail. In the case of M. igneus DIP does not contribute to the osmotic balance until the growth temperature is higher than 80°C (12).

Why is DIP accumulated only at high growth temperatures? In vitro studies of the temperature dependence of enzyme activities in M. igneus involved in biosynthesis of DIP provide some insight into this question. The condensation of CDP-I and myo-inositol by DIP synthase in crude protein fractions has a high activation energy, ∼120 kJ · mol−1. For comparison, the first two steps in the DIP biosynthetic pathway, I-1-P synthase and I-1-P phosphatase, exhibit much lower activation energies, 60 to 70 and ∼50 kJ · mol−1, respectively (9). At lower growth temperatures, any I-1-P generated may be hydrolyzed to myo-inositol, possibly for incorporation into lipids. I-1-P cannot build up to levels needed for conversion to CDP-I and eventual DIP synthesis. As the growth temperature is increased, however, not only is more I-1-P generated but DIP synthase activity is enhanced. DIP synthesis in other thermophiles should be examined to see if this hierarchy of activation energies is part of a universal trend or is unique to this methanogen.

From “X” to β-glutamate to β-glutamine … . β-Glutamate is the most ubiquitous of the β-amino acids found in archaea and a few eubacteria as well. However, the biosynthetic pathway for this species is not yet known, although information is available on what potential pathways do not generate β-glutamate in methanogens. Studies of transaminase activities in M. thermolithotrophicus clearly show that β-ketoglutarate cannot be converted to β-glutamate by using alanine or aspartate as nitrogen donors in the reaction (41a). In the same fashion both 13C- and 15N-labeling experiments and incubation of crude protein extracts with α-glutamate do not yield the β-isomer (which would require a glutamate aminomutase activity) (41a). Two other routes to β-glutamate that involve soluble precursors can be proposed. (i) α-Ketoglutarate is reduced to α-hydroxyglutarate, which is then dehydrated to glutaconic acid. Addition of ammonia to the glutaconic acid would then generate β-glutamate. (ii) A three-carbon propionate unit with an aldehyde or amino group at C-3 is complexed with pyridoxal-5-phosphate and then condensed with an activated two-carbon unit (likely to be acetyl-coenzyme A). Since α-hydroxyglutarate has been detected in methanogens, it is possible that the first scheme is operational although there is at present no firm evidence. Clearly this is an area for further investigation.

Biosynthesis of β-glutamine in Methanohalophilus portucalensis occurs by the activity of a glutamine synthetase on β-glutamate. The accumulation of β-glutamine as an osmolyte at high concentrations of external NaCl is interesting in view of what is known about glutamine synthetases (GS) from a large number of organisms. In general this multimeric, highly (and diversely) regulated enzyme converts β-glutamate to β-glutamine poorly (i.e., high Km and low Vmax compared to those of α-glutamate as a substrate) (33). The one archaeal GS that has been purified (from Methanobacterium ivanovi) and characterized was not examined for its ease in converting β-glutamate to β-glutamine. In vitro, Methanohaliphilus portucalensis uses β-glutamate as a direct precursor of β-glutamine (63a), suggesting that the GS from this methanogen has different kinetic and regulatory properties from the GS of eukaryotes and eubacteria. The Vmax for this conversion is ∼0.14 that for l-α-glutamate conversion to α-glutamine. However, while cells supplemented with exogenous β-glutamate (under conditions where the β-glutamate was internalized) showed enhanced β-glutamine, the neutral β-amino acid was not the major solute (63). This might suggest that GS conversion of β-glutamate to β-glutamine and accumulation of this zwitterion (as one of the trio of GB, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, and β-glutamine) are regulated indirectly by external NaCl.

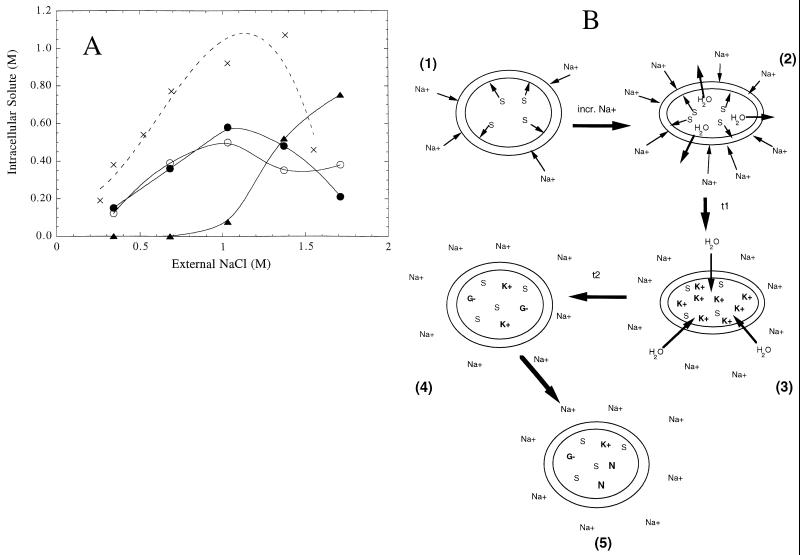

Nɛ-Acetyl-β-lysine: control of lysine aminomutase? At low osmolarity (<1 M NaCl) α-glutamate and β-glutamate are the primary organic solutes in M. thermolithotrophicus. When adapted to growth at higher salinity (Fig. 4), the organism accumulates Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, and it rapidly becomes the major solute as external NaCl is increased still further (59, 62). Nothing is known about what regulates the transition from accumulation of the anionic glutamate isomers to accumulation of the zwitterion at high external NaCl. Perhaps K+ levels reach a saturation point where further cation accumulation would be detrimental to cell function. In order to avoid this the cell adapts by accumulation of something zwitterionic. Another possibility is that Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine biosynthesis is controlled by Na+ and/or K+ and this solute is synthesized only when intracellular K+ levels are high. The synthesis of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine involves lysine 2,3-aminomutase conversion of α-lysine to β-lysine followed by acetylation of the side chain amino group (56, 60). Since α-lysine is necessary for all protein biosynthesis, it is unlikely that any of its biosynthetic enzymes are osmotically regulated. A more likely way of controlling Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine synthesis and accumulation would be to regulate lysine 2,3-aminomutase. Lysine aminomutase activities from bacteria that metabolize α-lysine as a carbon and nitrogen source have been purified and characterized (10, 22), and a very oxygen labile lysine aminomutase activity has been detected in anaerobic extracts of M. thermolithotrophicus (14).

FIG. 4.

(A) Intracellular organic osmolytes in M. thermolithotrophicus as a function of adapted growth in different concentrations of NaCl. ●, l-α-glutamate; ○, β-glutamate; ▴, Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine; ×, K+. (B) Scheme indicating how M. thermolithotrophicus responds to an increase in external NaCl. (1) Initially the cell is balanced at a particular concentration of external NaCl; S represents intracellular solutes. (2) Immediately after the cells are subjected to increased external NaCl, water will tend to rush out of the cells. (3) The most immediate osmotic response of these cells is to internalize K+ (within minutes) at a concentration that is in excess of those of the organic solute counterions available in the cell; over a time scale of 10 to 15 min a new intracellular K+ concentration is reached. (4) Over a longer period of time (25 to 60 min), l-α-glutamate is accumulated as a counterion to the K+ (cells are still not growing and are in a lag phase). (5) After cells begin to grow, there is synthesis and accumulation of the other organic osmolytes in the ratios seen in adapted cultures.

Further work must be done to better understand what controls the osmoadapted response. However, what is known is that K+ plays an important role in the immediate (and transient) response of this organism to hyperosmotic (increased NaCl) or hypoosmotic (decreased NaCl) shock (14). Within the first few minutes after transfer to the higher-NaCl-containing medium, M. thermolithotrophicus internalizes K+. This is followed by a decrease to steady-state levels over a time course of 15 to 20 min. Once the K+ reaches a new steady-state concentration, synthesis and accumulation of L-α-glutamate occur. The K+–α-glutamate pair functions as a temporary osmolyte. Once growth of the M. thermolithotrophicus culture begins, typically 60 to 90 min after the increase in NaCl concentration, the nonmetabolizable zwitterion (Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine) is synthesized and accumulated. A schematic diagram suggesting the steps in the osmotic response of this organism is shown in Fig. 4B. That Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine accumulation occurs in osmoadapted cells (i.e., after the lag phase) is consistent with the hypothesis that one of its biosynthetic enzymes is not available in cells grown and adapted to lower NaCl.

GB: methylation of glycine depends on intracellular K+. Methanohalophilus portucalensis is relatively unique in the archaeal domain in that it can synthesize GB de novo (36). The biosynthesis of GB in this organism occurs by methylation of glycine (56) with S-adenosylmethionine as the methyl donor (37). More importantly, in vitro studies show that the methylation reactions are K+ dependent, with little betaine accumulating below 0.4 M K+; at this potassium concentration sarcosine was the major product. K+ concentrations above 0.4 M enhanced GB synthesis from sarcosine and N,N-dimethylglycine (37). This observation suggests that control of betaine synthesis is modulated by intracellular K+; this cation may also function as an intracellular signal for osmoregulation in M. portucalensis.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Studies of osmoadaptation in many organisms have shown that this is a complex process that involves osmolyte accumulation, solute discrimination, control of ion flux, signaling, and change in protein expression. The last of these, change in protein expression, has been explored in yeast and mammals (7) but has not been examined in archaea, with the exception of the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii. Protein expression, as determined at the gene and protein levels, in this archaeon is affected by changes in external NaCl (21, 47). Differential expression occurs under both low and high salt conditions. Several of these proteins may be heat shock proteins, but it is possible that others may have more specific roles in osmoregulation (synthesis of osmolytes or transport of ions or solutes, etc.). The end result of osmoadaptation, specific solute accumulation, has been characterized for many archaea. However, the physiological and biochemical details of how these solutes are accumulated are not well understood. A number of unanswered questions remain regarding these cells. For example, the transient response of M. thermolithotrophicus to increased external NaCl is similar to that of the eubacterium Escherichia coli. In E. coli, there is a rapid accumulation of excess K+, which then decreases to a steady state, followed by accumulation of l-α-glutamate. Further changes in the l-α-glutamate pool over a longer time course lead to a redistribution of solutes that reflects the composition of osmoadapted cells at the higher NaCl growth conditions. Is this a general response in other archaea as well? Additionally, why do many of these cells synthesize several different solutes (i.e., Methanohalophilus portucalensis uses three zwitterions and M. igneus uses three anions) rather than produce just one solute for osmotic balance? What is the biochemical basis for why some cells change osmolyte strategies as a function of external NaCl or growth temperature (i.e., why is Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine produced in M. thermolithotrophicus only at high salt concentrations). Given the unusual collection of archaeal osmolytes, a deeper understanding of the protective effect of these solutes on macromolecular structure will also be needed to shed light on mechanisms of osmoregulation and osmoadaptation.

TABLE 1.

Extracellular Na+ and intracellular K+ concentrations in archaea

| Organism | Concn (M) of:

|

Reference(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Na+a | Intracellular K+ | ||

| Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | 0.02–0.20 | 0.65–1.1 | 13, 29, 70 |

| Methanospirillum hungatei | 0.03 | 0.15–0.20 | 70 |

| M. thermolithotrophicus | 1.0 | 0.9b | 60 |

| Methanogenium cariaci | 1.0 | 0.95c | 60 |

| Methanosarcina thermophila | ≤0.05 | 0.18 | 40, 69 |

| Methanohalophilus portucalensis | 2.0 | 0.76 | 36 |

| H. halobium | 3.4–4.3 | 2.1 | 66 |

| H. salinarium | 4.0 | 4.57 | 11 |

| N. occultus | 3.4 | 1.1 | 18 |

For NaCl concentrations of <0.5 M, the external Na+ concentrations indicated include all sodium salts in the medium.

From data (micromoles of K+/milligram of protein) presented in reference 60, with cell volume conversion as detailed in reference 15.

From data (micromoles of K+/milligram of protein) presented in reference 60, assuming a protein concentration per cell volume similar to that in M. thermolithotrophicus.

TABLE 2.

Relative acidities of the ribosomal proteins of various archaea compared to those of E. coli and correlation with external NaCl or internal K+

TABLE 3.

Eubacterial sugars and polyols used for osmotic balance and their archaeal counterparts

TABLE 4.

Distribution of commonly occurring amino acids and derivatives used as osmolytes in archaea

TABLE 5.

Other solutes found in high concentrations in archaea

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work has been supported by grant DE-FG02-91ER20025 (to M.F.R.) from the Department of Energy Biosciences Division.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa T, Timasheff S N. Preferential interactions of proteins with solvent components in aqueous amino acid solutions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin W W, Myer R, Kung T. Growth and buoyant density of Escherichia coli at very low osmolarities. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:235–237. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.235-237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baskakov I, Bolen D W. Forcing thermodynamically unfolded proteins to fold. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4831–4834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boch J, Kempf B, Bremer E. Osmoregulation in Bacillus subtilis: synthesis of the osmoprotectant glycine betaine from exogenously provided choline. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5364–5371. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5364-5371.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandis A, Thauer R K, Stetter K O. Relatedness of strains ΔH and Marburg of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Zentralbl Bakteriol Hyg Infektionskr Parasitenkd Abt 1 Orig Reihe C. 1981;2:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown A D. Microbial water stress. Bacteriol Rev. 1976;40:803–846. doi: 10.1128/br.40.4.803-846.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burg M B, Kwon E D, Kultz D. Osmotic regulation of gene expression. FASEB J. 1996;10:1598–1606. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cayley S, Lewis B A, Guttman H J, Record M T., Jr Characterization of the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli K-12 as a function of external osmolarity: implications for protein-DNA interactions in vivo. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:281–300. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90212-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Spiliotis E T, Roberts M F. Biosynthesis of di-myo-inositol-1,1′-phosphate, a novel osmolyte in hyperthermophilic archaea. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3785–3792. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3785-3792.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirpich T P, Zappia V, Costilow R N, Barker H A. Lysine 2,3-aminomutase. Purification and properties of a pyridoxal phosphate and S-adenosylmethionine-activated enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:1778–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christian J H B, Waltho J A. Solute concentrations within cells of halophilic and non-halophilic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1962;65:506–508. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciulla R A, Burggraf S, Stetter K O, Roberts M F. Occurrence and role of di-myo-inositol-1-1′-phosphate in Methanococcus igneus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3660–3664. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3660-3664.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ciulla R, Clougherty C, Belay N, Krishnan S, Zhou C, Byrd D, Roberts M F. Halotolerance of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH and Marburg. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3177–3187. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3177-3187.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciulla, R. A., D. D. Martin, P. M. Robinson, and M. F. Roberts. Switching osmolyte strategies: response of Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus to changes in external NaCl. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Ciulla R, Krishnan S, Roberts M F. Internalization of sucrose by Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:421–429. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.421-429.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csonka L N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:121–147. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cummings S P, Gilmour D J. The effect of NaCl on the growth of a Halomonas species: accumulation and utilization of compatible solutes. Microbiology. 1995;141:1413–1418. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-6-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desmarais D, Jablonski P, Fedarko N S, Roberts M F. 2-Sulfotrehalose, a novel osmolyte in haloalkaliphilic archaea. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3146–3153. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3146-3153.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdmann N, Fulda S, Hagemann M. Glucosylglycerol accumulation during salt acclimation of two unicellular cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farwick M, Siewe R M, Kramer R. Glycine betaine uptake after hyperosmotic shift in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4690–4695. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4690-4695.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrer C, Mojica F J, Juez G, Rodriguez-Valera F. Differentially transcribed regions of Haloferax volcanii genome depending on the medium salinity. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:309–313. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.309-313.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frey P A. Lysine 2,3-aminomutase: is adenosylmethionine a poor man’s adenosylcobalamin? FASEB J. 1993;7:662–670. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.8.8500691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu M-X, Wells-Knecht K J, Blackledge J A, Lyons T J, Thorpe S R, Baynes J W. Glycation, glycoxidation, and cross-linking of collagen by glucose: kinetics, mechanisms and inhibition of late stages of the Maillard reaction. Diabetes. 1994;43:676–683. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.5.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galinski E A. Compatible solutes of halophilic eubacteria: molecular principles, water-solute interaction, stress production. Experientia. 1993;49:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galinski E A, Pfeiffer H-P, Truper H G. 1,4,5,6-Tetrahydro-2-methyl-4-pyrimidinecarboxylic acid: a novel cyclic amino acid from halophilic phototrophic bacterium Ectothiorhodosphira. Eur J Biochem. 1985;149:135–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gorkovenko A, Roberts M F, White R H. Identification, biosynthesis, and function of 1,3,4,6-hexanetetracarboxylic acid in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1249–1253. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1249-1253.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Staphylococcus aureus osmoregulation: roles for choline, glycine betaine, proline, and taurine. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2711–2716. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2711-2716.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imhoff J F. Osmoregulation and compatible solutes in eubacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarrell K F, Sprott G D, Matheson A T. Intracellular potassium concentration and relative acidity of the ribosomal proteins of methanogenic bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1984;30:663–668. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Javor B. Hypersaline environments: microbiology and biogeochemistry. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1989. pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jebbar M, Talibart R, Gloux K, Bernard T, Blanco C. Osmoprotection of Escherichia coli by ectoine: uptake and accumulation characteristics. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5027–5035. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5027-5035.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaenjak A, Graham J E, Wilkinson B J. Choline transport activity in Staphylococcus aureus induced by osmotic stress and low phosphate concentrations. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2400–2406. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.8.2400-2406.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khedouri E, Meister A. Synthesis of d-β-glutamine from β-glutamic acid by glutamine synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:3357–3360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kogut M, Russell N J. Life at the limits: considerations on how bacteria can grow at extreme temperature and pressure, or with high concentration of ions and solutes. Sci Prog. 1987;71:381–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushwaha S C, Perez G J, Valera F R, Kates M, Kushner D J. Survey of lipids of a new group of extremely halophilic bacteria from salt ponds in Spain. Can J Microbiol. 1982;28:1365–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai M-C, Sowers K R, Robertson D E, Roberts M F, Gunsalus R P. Distribution of compatible solutes in the halophilic methanogenic archaebacteria. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5352–5358. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5352-5358.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai M-C, Yang D-R, Chuang M-J. Regulatory factors associated with synthesis of the osmolyte glycine betaine in the halophilic methanoarchaeon Methanohalophilus portucalensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:828–833. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.828-833.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Lai, M.-C., T.-Y. Hong, and R. P. Gunsalus. Unpublished results.

- 38.Lamosa P, Martins L O, Da Costa M S, Santos H. Effects of temperature, salinity, and medium composition on compatible solute accumulation by Thermococcus spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3591–3598. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3591-3598.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Rudulier D, Strom A R, Dandekar A M, Smith L T, Valentine R C. Molecular biology of osmoregulation. Science. 1984;224:1064–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.224.4653.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lundie L L, Ferry J G. Activation of acetate by Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:18392–18396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackay M A, Norton R S, Borowitzka L J. Organic osmoregulatory solutes in cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2177–2191. [Google Scholar]

- 41a.Martin, D. D., and M. F. Roberts. Unpublished results.

- 42.Martins L O, Santos H. Accumulation of mannosylglycerate and di-myo-inositol phosphate by Pyrococcus furiosus in response to salinity and temperature. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3299–3303. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3299-3303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martins L O, Carreta L S, Da Costa M S, Santos H. New compatible solutes related to di-myo-inositol-phosphate in members of the order Thermotogales. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5644–5651. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5644-5651.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martins L O, Huber R, Huber H, Stetter K O, Da Costa M, Santos H. Organic solutes in hyperthermophilic Archaea. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:996–1002. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.896-902.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maruta K, Mitsuzumi H, Nakada T, Kubota M, Chaen H, Fukuda S, Sugimoto T, Kurimoto M. Cloning and sequencing of a cluster of genes encoding novel enzymes of trehalose biosynthesis from thermophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1292:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(96)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsubara T, Tanaka N I, Kamekura M, Moldoveanu N, Ishizuka I, Onishi H, Hayashi A, Kates M. Polar lipids of a non-alkaliphilic extremely halophilic archaebacterium strain 172: a novel bis-sulfated glycolipid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1214:97–108. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mojica F J, Cisneros E, Ferrer C, Rodriguez-Valera F, Juez G. Osmotically induced response in representatives of halophilic prokaryotes: the bacterium Halomonas elongata and the archaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5471–5481. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5471-5481.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monnier V M. Toward a Maillard reaction theory of aging. In: Baynes J W, Monnier V M, editors; Baynes J W, Monnier V M, editors. The Maillard reaction in aging, diabetes and nutrition: an NIH conference. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss; 1989. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicolaus B, Gambacorta A, Basso A L, Riccio R, De Rosa M, Grant W D. Trehalose in archaebacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1988;10:215–217. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters P, Tel-Or E, Truper H G. Transport of glycine betaine in the extremely haloalkaliphilic sulfur bacterium Ectothiorhodospira halochloris. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1993–1998. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Plaza del Pino I M, Sanchez-Ruiz J M. An osmolyte effect on the heat capacity change for protein folding. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8621–8630. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Proctor L M, Lai R, Gunsalus R P. The methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1 possesses a high-affinity glycine betaine transporter involved in osmotic adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2252-2257.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qu Y, Bolen C L, Bolen D W. Osmolyte-driven contraction of a random coil protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9268–9273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Record M T, Courtenay E S, Cayley D S, Guttman H J. Responses of E. coli to osmotic stress: large changes in amounts of cytoplasmic solutes and water. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01196-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reed R H, Borowitzka L J, Mackay M A, Chudek J A, Foster R, Warr S R C, Moore D J, Stewart W D P. Organic solute accumulation in osmotically stressed cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts M F, Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P. Biosynthetic pathways of the osmolytes Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, β-glutamine, and betaine in Methanohalophilus strain FDF1 suggested by nuclear magnetic resonance analyses. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6688–6693. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6688-6693.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robertson D E, Roberts M F. Organic osmolytes in methanogenic archaebacteria. BioFactors. 1991;3:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robertson D E, Lai M-C, Gunsalus R P, Roberts M F. Composition, variation, and dynamics of major osmotic solutes in Methanohalophilus strain FDF1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2438–2443. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2438-2443.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robertson D E, Lesage S, Roberts M F. β-Aminoglutaric acid is a major soluble component of Methanococcus thermolithotrophicus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;992:320–326. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(89)90091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robertson D E, Noll D, Roberts M F. Free amino acid dynamics in marine methanogens. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14893–14901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robertson D E, Noll D, Roberts M F, Menaia J A G F, Boone D R. Detection of the osmoregulator betaine in methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:563–565. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.2.563-565.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robertson D E, Roberts M F, Belay N, Stetter K O, Boone D R. Occurrence of β-glutamate, a novel osmolyte, in marine methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1504–1508. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1504-1508.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson P M, Roberts M F. Effects of osmolyte precursors on the distribution of compatible solutes in Methanohalophilus portucalensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4032–4038. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4032-4038.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63a.Robinson, P. M., and M. F. Roberts. Unpublished results.

- 64.Santoro M M, Liu Y, Khan S M A, Hou L, Bolen D W. Increased thermal stability of proteins in the presence of naturally occurring osmolytes. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5278–5283. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scholz S, Sonnenbichler J, Schafer W, Hensel R. Di-myo-inositol-1-1′-phosphate: a new inositol phosphate isolated from Pyrococcus woesei. FEBS Lett. 1992;306:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81008-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shporer M, Civan M M. Pulsed nuclear magnetic resonance study of 39K within halobacteria. J Membr Biol. 1977;33:385–400. doi: 10.1007/BF01869525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Somero G N, Osmond C B, Bolis C L. Water and life: comparative analysis of water relationships at the organismic, cellular, and molecular levels. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sowers K R, Robertson D E, Noll D, Gunsalus R P, Roberts M F. Nɛ-Acetyl-β-lysine: an osmolyte synthesized by methanogenic archaebacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9083–9087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sowers K R, Gunsalus R P. Halotolerance in Methanosarcina spp.: role of Nɛ-acetyl-β-lysine, α-glutamate, glycine betaine, and K+ as compatible solutes for osmotic adaptation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4382–4388. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4382-4388.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sprott G D, Jarrell K F. K+, Na+, and Mg2+ content and permeability of Methanospirillum hugatei and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27:444–451. doi: 10.1139/m81-067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Taylor B F, Gilchrist D C. New routes for aerobic biodegradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3581–3584. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3581-3584.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Upasani V N, Vivek N, Desai S, Moldoveanu N, Kates M. Lipids of extremely halophilic archaeobacteria from saline environments in India: a novel glycolipid in Natronobacterium strains. Microbiology. 1994;140:1959–1966. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vreeland R H. Mechanisms of halotolerance in microorganisms. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;14:311–356. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warr S R C, Reed R H, Stewart W D P. Osmotic adjustment of cyanobacteria: the effects of NaCl, KCl, sucrose, and glycine betaine on glutamine synthetase activity in a marine halotolerant strain. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2169–2175. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiggins P M. Role of water in some biological processes. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:432–449. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.432-449.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yancey P H, Clark M E, Hand S C, Bowlus R D, Somero G N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982;217:1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]