Abstract

Mutations in the genes encoding calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2) isoforms cause a newly recognized neurodevelopmental disorder (ND), for which the full clinical spectrum has yet to be described. Here we report the detailed description of a child with a de novo gain of function (GoF) mutation in the gene Ca/Calmodulin dependent protein kinase 2 beta (CAMK2B c.328G > A p.Glu110Lys) who presents with developmental delay and periodic neuropsychiatric episodes. The episodes manifest as encephalopathy with behavioral changes, headache, loss of language and loss of complex motor coordination. Additionally, we provide an overview of the effect of different medications used to try to alleviate the symptoms. We show that medications effective for mitigating the child’s neuropsychiatric symptoms may have done so by decreasing CAMK2 activity and associated calcium signaling; whereas medications that appeared to worsen the symptoms may have done so by increasing CAMK2 activity and associated calcium signaling. We hypothesize that by classifying CAMK2 mutations as “gain of function” or “loss of function” based on CAMK2 catalytic activity, we may be able to guide personalized empiric treatment regimens tailored to specific CAMK2 mutations. In the absence of sufficient patients for traditional randomized controlled trials to establish therapeutic efficacy, this approach may provide a rational approach to empiric therapy for physicians treating patients with dysregulated CAMK2 and associated calcium signaling.

Keywords: case report, human genetics, ca/calmodulin dependent protein kinase 2B, Camk2b, CAMKIIβ, developmental delay, acute periodic neuropsychiatric episode, encephalopathy

Introduction

Calcium/calmodulin (Ca/CaM) dependent protein kinase II (CAMK2) is a ubiquitous serine/threonine protein kinase that is central in coordinating calcium signaling in the cell. The kinase is encoded by four genes that give rise to four classes of homologous isoforms and many alternative spliced products. The isoforms differ in part by their sensitivity to calcium and their spatiotemporal expression pattern. Whereas CAMK2A and CAMK2B are primarily found in the brain, CAMK2G and CAMK2D are found throughout the body with higher levels in the vasculature and heart (Pellicena and Schulman, 2014; Bayer and Schulman, 2019). The kinase is a 12 subunit holoenzyme generally composed of different isoforms.

The CAMK2 signaling cascade is initiated when intracellular calcium levels increase. Calcium forms a complex with calmodulin, whereupon this complex binds to CAMK2, causing a conformational change and activation of the kinase (Lisman et al., 2002; Hell 2014; Bayer and Schulman, 2019). Once the kinase is activated, there are multiple positive feedback mechanisms that enhance its own activation: 1) activated CAMK2 subunits phosphorylate neighboring calcium/calmodulin bound subunits, 2) activated kinase can anchor to proteins near the site of calcium entry, 3) activated CAMK2 can increase the influx of calcium through regulation of different calcium channels and 4) activated CAMK2 can promote calcium release from intracellular stores (Erickson, 2014; Onal et al., 2014; Pellicena and Schulman, 2014; Chia et al., 2018; Bayer and Schulman, 2019).

Recently, individuals carrying mutations in the genes coding for CAMK2A and CAMK2B have been described. (Küry et al., 2017; Akita et al., 2018) These individuals represent a “family” of disorders as each unique mutation has a different effect on CAMK2 activity and is therefore expected to be associated with a unique but overlapping neurodevelopmental phenotype. Most mutations are associated with developmental delay, seizures, and/or behavioral abnormalities (Onal et al., 2014; Küry et al., 2017; Akita et al., 2018; Chia et al., 2018; Rizzi et al., 2020). In order to be able to do proper genotype-phenotype correlation and gain insight into the full clinical spectrum associated with the different types of CAMK2 mutations, detailed reports of the clinical symptoms are required.

Here we report the detailed description of a child with a unique de novo mutation in the CAMK2B gene (CAMK2B c.328G > A p.Glu110Lys; published in Küry et al., 2017), focusing on the periodic acute neuropsychiatric episodes as a new CAMK2-related phenomenon. This CAMK2B mutation has been previously characterized as a Gain of Function (GoF) mutation (Küry et al., 2017). Despite reduced levels of expression compared to that with CAMK2B-WT in HEK-293T cells, the enzymatic activity has been shown to be significantly increased based on Thr287 autophosphorylation in vitro (Küry et al., 2017). Further supporting the dominant effect of the mutation, expression in vivo using in utero electroporation altered neuronal migration significantly when compared to that in the CAMK2B-WT.

In our report, we discuss the neuropsychiatric symptoms seen in the child and the medication regimen built on the basis of headache prophylaxis which decreased the severity of the neuropsychiatric episodes before the molecular diagnosis was known. Interestingly, after the molecular diagnosis was determined, it was realized that the effective medications potentially worked through decreasing calcium signaling and thereby CAMK2B activity. In addition to the case presentation, we provide an overview of putative therapeutics which we classify as medications that may up-regulate or down-regulate calcium signaling and associated CAMK2 activity. In conclusion, this is the first report synthesizing how common medications are thought to affect the CAMK2 activation cascade.

Case Description

The patient is a 15 year old Caucasian female with no dysmorphic features. At age 7 years, following longstanding unexplained global developmental delay and new onset acute neuropsychiatric episodes, trio whole exome sequencing was performed. Re-analysis at age 10 years revealed a de novo heterozygous pathogenic variation in the gene CAMK2B c.328G > A p.Glu110Lys encoding the protein Calcium/Calmodulin-dependent kinase II beta (CAMK2B) (Küry et al., 2017).

The patient is a product of a normal pregnancy. She was born at full term by normal vaginal delivery without signs of fetal distress or need for resuscitation. The newborn period was significant for being unable to orally coordinate nursing until 6 months of life and for daily inconsolable crying. Her subsequent development was notable for moderate to severe global developmental delay which will be briefly summarized below. Initial investigation into causes of her delays revealed normal neuroimaging, normal karyotype and microarray, and normal metabolic studies.

Development

Motor Development

This was characterized by low tone and difficulty in coordinating purposeful movement (apraxia). At age 11 months, her motor skills were formally evaluated to be at the level of a 6 month old. With intensive occupational therapy she sat on her own at 12 months, crawled at 13 months and walked unsupported at 17 months. She was continent of urine and stool at age 4. At age 15 years, she can walk and run despite an abnormal gait. She has significant trouble with complex motor planning, such as climbing a ladder, swimming, or riding a scooter. Fine motor skills are similarly difficult. At age 15, she can write her name but with large inaccurate letters.

Speech Development

Given significant difficulty with oral motor coordination, her ability to produce speech was far behind her ability to understand speech. At age 2, speech therapy (PROMPT technique) focused on producing intended single syllable sounds. With daily speech therapy, she was able to produce 2-3 word sentences by 3–4 years of age. She was ultimately narrative by 6 years of age. At age 15 years, she continues to have problems with articulation and word finding. Her language is repetitive. Language comprehension is normal or near normal.

Cognitive Development

At age 15 years, she can read but is hindered in doing so by attention deficits and/or by visual apraxia (difficulty with visual tracking/coordination). At age 15, she has profound difficulty with math and is still working on single digit addition.

Behavioral Development

From an early age, she had difficulty with self-regulation, such as calming herself and was difficult to soothe. Even at age 15 years, frustration or emotional distress can escalate into aggression towards others (hair pulling, scratching and pinching) or self-injury (causing herself to bleed with skin and nose picking). She has a limited attention span which has improved some with age. At age 15 years, she is able to watch her iPad for 20 min alone. She can be impulsive and has particular difficulty in keeping her hands still. The impulsiveness limits her ability to attend.

Social Development

Currently at age 15, she enjoys interaction with adults and peers. She displays empathy. However, she has difficulty in continuing conversation and has maladaptive ways to resolve conflict. She is at baseline mostly happy and enthusiastic.

Recurrent Neuropsychiatric Episodes

At age 7, the patient developed a week long period of encephalopathic symptoms, including confusion, agitation, and regression in skills. The episode was sudden in onset and offset without any clear triggers. Her symptoms included being disoriented, not responding to people or events around her, and inconsolable crying. She had non- purposeful behavior such as mouthing a caregiver which could then result in biting. She stopped talking other than stereotypic sentences and stopped eating and drinking. Medical evaluation was unremarkable. After 7–8 days, the patient returned to her usual state of health. Over the next several months, she had recurrent but less severe episodes lasting 7–10 days. Endocrine evaluation showed no evidence of puberty. A similar pattern of symptoms with striking sudden onset and offset would occur, always including confusion, agitation/crying, aggression and a regression in skills. Sometimes behaviors not previously seen were observed, such as spitting at a person or biting a non-food object.

Several months into these serial episodes, the patient was evaluated in the ER for inconsolable crying. She was treated presumptively for headache and was given prochlorperazine and ketorolac. Immediately after the prochlorperazine dose, the patient became severely disoriented and agitated, requiring 4 point restraints to keep her safe. Her altered mental state was presumed secondary to a drug reaction from the prochlorperazine and she was admitted to the hospital. In addition to being severely disoriented and agitated, she had stereotypic movements (pelvic thrusting and grimacing). No dystonic movements, posturing or movements suspicious for epileptic activity were observed. Similar to her first encephalopathic episode, she did not respond to outside stimuli and did not talk or eat. Autonomic features included urinary retention requiring regular catheterization and constipation requiring disimpaction. When her condition did not improve after 3 days, a comprehensive evaluation for altered mental status was done, including repeat brain imaging, EEG, an autoimmune work-up (including anti-NMDA and anti-strep antibodies in the cerebral spinal fluid) and a comprehensive metabolic evaluation (including screening for porphyria). All results were unremarkable. After 10 days this episode suddenly stopped and the patient was back to her functional baseline.

This encephalopathic pattern repeated at regular intervals (every 21–28 days) for the next 8 months with each neuropsychiatric episode requiring hospitalization to reduce self-harm via sedation, to provide nourishment and hydration, and to perform urinary catheterization.

During one of these episodes the patient complained of a severe headache, upon which re-examination revealed unilateral ptosis with ipsilateral scleral injection. Using a working diagnosis of cluster headache, verapamil and lamotrigine were prescribed with a plan to increase verapamil until limited by heart rate. With each increase in verapamil dose, the degree of symptoms experienced during the episodes decreased.

Once improvement plateaued, a child psychiatrist specialized in acute neuropsychiatric episodes recommended adding lithium based on its efficacy in another episodic neuropsychiatric syndrome, Kleine-Levin syndrome. With the addition of lithium to the verapamil and lamotrigine regimen, there was an immediate improvement noted in the level of disorientation and confusion during the episodes. As with the verapamil, with increasing doses of lithium, the patient improved. Although the episodes continued, she did well enough during them that she no longer had to be hospitalized and was able to attend school regularly.

The verapamil dose was ultimately limited by bradycardia and intermittent Wenckebach. In response, the verapamil dose was decreased and the episodes again worsened. She was put on paroxetine. The edges of the episodes became harder to distinguish and she was notably confused, agitated and aggressive most days. This decompensation was not originally recognized as being due to the paroxetine. However, after several months the paroxetine was discontinued due to prolonged QTc and the aggression/agitation between episodes resolved.

Through a process of trial and error over a 2 year period and using the treatment of headache as a guide, the combination of verapamil, lithium, lamotrigine, valproic acid, magnesium oxide, and riboflavin effectively controlled her symptoms. Currently (8 years after the recognition of episodes), the episodes continue but their severity has dramatically decreased. She continues to have 7–10 day periods every 21–28 days where she has more difficulty in calming (problems with aggression and self-injury), with concentrating, with increased impulsivity, and with loss of language and complex motor coordination (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Abbreviations: WES, whole exome sequencing.

As noted above, the child’s CAMK2B mutation was not diagnosed until age 10 years of age. She was subsequently reported in the first cohort of individuals with known CAMK2A and CAMK2B mutations associated with intellectual disability (Küry et al., 2017). Importantly, the genetic diagnosis came after her periodic neuropsychiatric episodes were recognized and treated.

Discussion

In summary, we present the detailed clinical description of a child with global developmental delay and recurrent neuropsychiatric episodes due to a de novo CAMK2B mutation, CAMK2B c.328G > A p.Glu110Lys.

Previous functional assays have shown that the CAMK2B p.Glu110Lys mutation when compared to CAMK2B-WT results in increased enzymatic activity as assessed by autophosphorylation at Thr287, but reduced expression levels in HEK293T cells (Küry et al., 2017). As such, the increased autophosphorylation of mutated protein and associated autonomous kinase activity seen in vitro arguably may not be clinically relevant given the expression of the mutated protein is reduced in vivo. However, a mutation in CAMK2B even expressed in low levels could still affect the activity of the holoenzyme given that CAMK2A and CAMK2B form heteromeric holoenzymes. A similar dominant effect has been shown for mutations in CAMK2A, e.g., the T305D or TT305/6VA mutation. In both cases protein levels are reduced, but the localisation of the whole heteromeric holoenzyme is altered due to the mutation in CAMK2A. (Elgersma et al., 2002)

The case described here is unique in that it links a CAMK2B mutation to both developmental delay and periodic neuropsychiatric episodes. Other Gain of Function CAMK2B mutations (CAMK2B p.Pro139Leu and CAMK2B p.Glu237Lys) have been described, but the presence or absence of neuropsychiatric symptoms were not discussed in the reports (Küry et al., 2017; Rizzi et al., 2020). Deep phenotyping with highly standardized questionnaires and testing needs to be performed in order to see whether the neuropsychiatric episodes are a commonality for CAMK2B mutations. Although it is still possible that our patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms are not related to CAMK2, it is compelling that medications known to reduce calcium signaling alleviated the extent of her symptoms. These results suggest that there is a potential causal link between CAMK2 hyperactivity and the neuropsychiatric symptoms.

The periodicity of the symptoms is difficult to explain. One hypothesis could be that due to the increased basal activity of CAMK2B in this patient, the threshold for CAMK2 overload is severely reduced. When this threshold is crossed, neuropsychiatric symptoms result. In this model, periodic fluctuations in calcium levels in a critical brain region would then be enough to trigger the occurrence of these symptoms. This is supported by the finding that reducing calcium signaling alleviated the symptoms in our patient. A correlation between transient increases in CAMK2 activity and episodic neuropsychiatric illnesses has been suggested before in disorders such as Syndenham’s chorea, PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal infections), and PANS (Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome). (Kirvan et al., 2003; Kirvan et al. 2006a; Kirvan et al. 2006b; Chang et al., 2015; Shimasaki et al., 2020)

Hypothetical Framework for Treatment

The neuropsychiatric episodes described here were treated by targeting symptoms of both cluster headache and Kleine-Levin syndrome-like acute neuropsychiatric episodes (Leu-Semenescu et al., 2015). In retrospect, medications that improved the symptoms (verapamil, lithium, valproic acid, lamotrigine and magnesium oxide) have been shown pre-clinically to decrease calcium signaling and/or decrease CAMK2 activity (Celano et al., 2003; Wallace 2014; Zamponi 2015; Asmara et al., 2017). In contrast, one medication that appeared to worsen the symptoms (paroxetine) has been shown pre-clinically to increase CAMK2 activity (Meshul and Tan, 1994; Celano et al., 2003). The other medication that appeared to worsen the patient’s illness was prochlorperazine. While this medication has not been specifically studied with regard to CAMK2 activity, a similar antidopaminergic medication, haloperidol, has been pre-clinically associated with increased CAMK2 activity (Meshul and Tan, 1994). Based on the patient’s response to medications alone, one might deduce that this patient’s mutation confers increased CAMK2B activity. Indeed, this was confirmed when testing the mutant CAMK2B phosphotransferase activity (Küry et al., 2017). Further, the comparable mutation in CAMK2A produces a constitutively active Ca/CaM-independent CAMK2A (Yang and Schulman, 1999).

We safely and effectively used verapamil, lithium, valproic acid, lamotrigine and magnesium in a patient with a gain of function CAMK2B mutation to mitigate neuropsychiatric symptoms. From the perspective of the child’s parents, although it took years to develop this regimen via trial and error, the child’s and the parents’ quality of life with the medication regimen is significantly improved. Rather than requiring hospitalization for 10–14 days every month for agitation/disorientation/aggression, the child is able to go to school during these episodes albeit with an increase in support. Although our regimen was developed empirically toward symptoms, we cautiously introduce the idea of targeting medications toward normalizing CAMK2 activity in other affected individuals. When considering first and second line established therapies or when there are no established therapies, a physician can take a medication’s CAMK2 profile into account. A potential strength of this approach is that it may allow for more timely intervention with a similar risk of side effects. Weaknesses of this approach include: 1) it may be an oversimplification to describe mutations as purely “gain of function” (GoF) or “loss of function” (LoF) in all downstream pathways, and 2) medication effects on CAMK2 activity may not correlate between in vitro and in vivo. As such, pharmacologic interventions may not work as predicted in all cases. A prerequisite to this approach is that the effect of the individual’s mutation on CAMK2 activity must be understood (GoF or LoF). The choice of medications may be further streamlined after putative medications are studied in in vitro and in vivo models. Medication side effects and their ability to cross the blood brain barrier should also be considered. When a medication is trialed, it may be useful to monitor patients with “n-of-1 protocols” to document efficacy.

To modify CAMK2 activity, we should also consider it within the context of cellular stimuli. CAMK2 activity is the net effect of CAMK2 calcium-dependent and calcium-independent activity. Calcium-dependent activity depends upon the level of intracellular calcium and consequent Ca/CaM activity. Once stimulated, Ca/CaM activates CAMK2 in a cooperative feed-forward manner. Thus even a small increase or decrease in calcium can markedly increase or decrease CAMK2 activity. In contrast, calcium-independent activity is intrinsic and depends upon the specific mutation. It can only be modified with a direct inhibitor. As such, we may be able to decrease CAMK2 activity by using medications that either decrease intracellular calcium, directly antagonize CaM, or directly inhibit CAMK2.

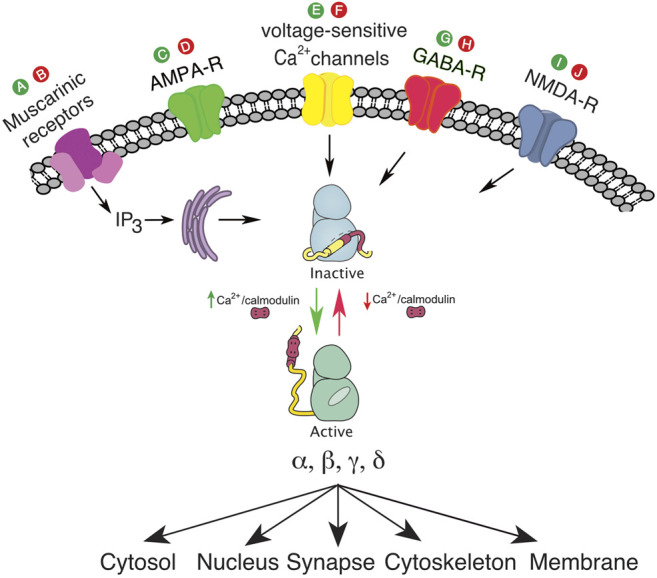

In Table 1, we list such putative drugs. Drugs which decrease intracellular calcium include: 1) drugs that directly inhibit voltage-gated calcium channels (calcium channel blockers), 2) drugs that reduce depolarization of neurons and the resultant calcium influx (antagonists of excitation e.g., ionotropic AMPA-R antagonists or agonists of inhibition e.g., GABA-R agonists), 3) drugs that antagonize other ligand-gated calcium channels (e.g., NMDA-R antagonists), 4) drugs that antagonize IP3/Calcium linked receptors e.g. muscarinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes 1/3, 5) drugs that antagonize ryanodine receptors (RyR) to decrease calcium release from intracellular stores, and 6) drugs that inhibit reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Lubeluzole and melatonin are examples of drugs that may directly antagonize CaM (Benítez-King et al., 1996; Bruno et al., 2016). Sodium oxybate is a unique example of a medication that can inhibit CAMK2 directly by inhibiting the hub domain of the CAMK2A holoenzyme. It inhibits the CAMK2A holoenzyme, but not the holoenzyme of other isoforms. (Leurs et al., 2021) See Figure 2; Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Putative medications are not limited to those listed above.

| Putative medications | Likely mechanism | Current use of medications |

|---|---|---|

| Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity | ||

| Angiotensin/aldosterone inhibitors | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓ROS (Erickson 2014) | Hypertension |

| Anti-oxidant Riboflavin | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓ROS | Riboflavin: Headache prophylaxis |

| Baclofen | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓖ↑GABA-BR inhibition (Evenseth et al., 2020) | Spasticity |

| Benzodiazepines | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓖ↑GABA-AR inhibition (Sills and Rogawski, 2020) | Anxiety, epilepsy |

| Calcium channel blockers Dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓L-, T- TypeCa++ influx (Zamponi, 2015) | hypertension, tachycardia, headache prophylaxis |

| Coenzyme Q | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓cytosolic Ca++ in HepG2 cells in vivo (Xu et al., 2017) | supplement,headache prophylaxis |

| ↓ROS shown in other settings (Xu et al., 2017) | ||

| Cox-2 inhibitors | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓NOS ( ↑NOS shown to increase CAMK2ɑ expression (Varga et al., 2009; Coultrap and Bayer 2014) | Pain relief |

| Curcurmin | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓Ca++ dependent and independent CAMK2A phosphorylation (Mayadevi et al., 2012) | Supplement |

| ↓ unclear mechanism (Hu et al., 2015) | ||

| Dantrolene | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity (in muscle) by ↓RyR1 CICR (Zhao et al., 2001) | Malignant hyperthermia |

| ↓RyR3 CICR (Zhao et al., 2001) | ||

| Ethosuximide | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓T- Type Ca++ | Epilepsy |

| Influx (Zamponi, 2015) | ||

| Ketamine | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓙ↓NMDA Ca++ influx (Cui et al., 2009) | Anesthesia |

| Lamotrigine | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓P/Q-, N-, R- Type Ca++ influx (Zamponi, 2015) | Epilepsy, mood disorders |

| ↓Presynaptic glutamine release (Deutschenbaur et al., 2016) | ||

| Lithium | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓙ↓NMDA Ca++ influx (Nonaka, Hough, and Chuang 1998; Celano et al., 2003) | Mood disorders |

| ↓presynaptic CAMK2A phosphorylation by unknown mechanism (Nonaka et al., 1998; Celano et al., 2003) | ||

| Levetiracetam | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓P/Q-, N- Type Ca++ influx (Dubovsky et al., 2015; Zamponi 2015) | Epilepsy |

| Ⓑ↓IP3 CICR (Nagarkatti et al., 2008; Zamponi, 2015) | ||

| Ⓓ↓AMPA receptor activation (Sills and Rogawski, 2020) | ||

| ↓RyR2 CICR (Nagarkatti et al., 2008; Zamponi, 2015) | ||

| Lubeluzole | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓Ca/CaM activity (Bruno et al., 2016) | Chemo-sensitization |

| Magnesium | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓Direct Ca++ antagonism | Supplement |

| Melatonin | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓Ca/CaM activity (Benítez-King et al., 1996) | Supplement |

| Perampanel | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓓ↓AMPA receptor activation (Sills and Rogawski, 2020) | Epilepsy |

| Propofol | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓙ↓NMDA Ca++ channel influx (Cui et al., 2009) | Anesthesia |

| Ⓖ↑GABA-AR inhibition (Cui et al., 2009) | ||

| Sodium Oxybate | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by ↓inhibits CAMK2A holoenzyme (Leurs et al., 2021) | Narcolepsy |

| Topiramate | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓R Type Ca++ influx (Zamponi 2015) | Epilepsy, mood disorders, headache prophylaxis |

| Ⓖ↑GABA-AR inhibition (Sills and Rogawski, 2020) | ||

| Valproic Acid | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓T Type Ca++ influx (Zamponi 2015) | Epilepsy, mood disorders |

| Zonisamide | Predicted to decrease CAMK2 activity by Ⓕ↓T Type Ca++ influx (Zamponi 2015) | Epilepsy |

| Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity | ||

| Aldosterone agonist-progestins | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑ROS (Erickson 2014) | Contraceptive |

| Haloperidol | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑CAMK2 activity by unclear mechanism (Meshul and Tan 1994; Rushlow et al., 2009) | Psychosis |

| Calcium/vitamin D | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑Ca++ | Mineral/ dietary supplement |

| Digoxin | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑Na+/Ca++ exchange, increasing Ca++ (heart) (Gonano et al., 2011) | Heart failure |

| ↑RyR CICR (heart) (Gonano et al., 2011) | ||

| SSRIs | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑presynaptic CAMK2A phosphorylation by unknown mechanism (Celano et al., 2003; Tiraboschi et al., 2004) | Depression |

| Tricyclics | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑presynaptic CAMK2A phosphorylation by unknown mechanism (Celano et al., 2003; Tiraboschi et al., 2004) | Depression, headache prophylaxis, control of nerve pain |

| Tacrolimus | Predicted to increase CAMK2 activity by ↑CAMK2 by ↓calcineurin | Immune suppression |

Table 1 Each medication’s action on CAMK2 is hypothesized by authors based on known mechanisms. Labels: Alphabetic labels refer to the site of proposed activity depicted in Figure 2.

Abbreviations: ROS, reactive oxygen species; GABA-AR, GABA-A receptor; GABA-BR, GABA-B receptor; Ca++, calcium; NOS, nitric oxide species; RyR, ryanodine receptor; Na+, sodium; CICR, calcium initiated calcium release.

FIGURE 2.

(A), putative drug to activate muscarinic receptors and IP3; (B), putative drug to inhibit muscarinic receptors and IP3; (C), putative drug to activate ionotropic AMPA-R; (D), putative drug to inhibit ionotropic AMPA-R; (E), putative drug to activate voltage sensitive calcium channel; (F), putative drug to inhibit voltage sensitive calcium channel; (G), putative drug to activate GABA-R; (H), putative drug to inhibit GABA-R; (I), putative drug to activate NMDA-R; (J), putative drug to inhibit NMDA-R. The green color denotes agonist activity at a specific receptor, and the red color denotes antagonist activity at a specific receptor.

In the absence of sufficient patients for traditional randomized controlled trials, targeting medications toward normalizing CAMK2 activity could be considered a rational approach for physicians treating patients with dysregulated CAMK2. Doing so in an organized fashion and using “n-of-1” protocols will contribute to a future data driven approach.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

BD: First author, integral in patient care, literature review, chart review, wrote manuscript, made Figure 1; Table 1, intellectual contribution regarding CAMK2 targeted therapies DV: Developmental pediatrician expert in CAMK2 gene disorders, intellectual contribution regarding CAMK2 targeted therapies, significant editing/mentorship. KC: Primary psychiatrist involved in case and significant editing/mentorship HS: Expert in CAMK2 structure, function, and activation cascade. Vetted idea regarding targeting CAMK2 therapies, significant mentorship/editing and made Figure 2 GvW: Expert in CAMK2 structure, function and activation cascade. Significant intellectual contribution regarding CAMK2 targeted therapies, vetted references, significant editing/mentorship.

Funding

GW is funded by NWO-VIDI (016.Vidi.188.014).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Akita T., Aoto K., Kato M., Shiina M., Mutoh H., Nakashima M., et al. (2018). De Novo Variants in CAMK2A and CAMK2B Cause Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 5 (3), 280–296. 10.1002/acn3.528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmara H., Micu I., Rizwan A. P., Sahu G., Simms B. A., Zhang F. X., et al. (2017). A T-type Channel-Calmodulin Complex Triggers αCaMKII Activation. Mol. Brain 10 (1), 37. 10.1186/s13041-017-0317-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer K. U., Schulman H. (2019). CaM Kinase: Still Inspiring at 40. Neuron 103 (3), 380–394. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-King G., Ríos A., Martínez A., Antón-Tay F. (1996). In Vitro Inhibition of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent Kinase II Activity by Melatonin. Biochimica Biophysica Acta 1290 (2), 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno C., Cavalluzzi M. M., Rusciano M. R., Lovece A., Carrieri A., Pracella R., et al. (2016). The Chemosensitizing Agent Lubeluzole Binds Calmodulin and Inhibits Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent Kinase II. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 116 (June), 36–45. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celano E., Tiraboschi E., Consogno E., D'Urso G., Mbakop M. P., Gennarelli M., et al. (2003). Selective Regulation of Presynaptic Calcium/calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II by Psychotropic Drugs. Biol. Psychiatry 53 (5), 442–449. 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01491-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K., Frankovich J., Cooperstock M., Cunningham M. W., Latimer M. E., Murphy T. K., et al. (2015). Clinical Evaluation of Youth with Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS): Recommendations from the 2013 PANS Consensus Conference. J. Child. Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 25 (1), 3–13. 10.1089/cap.2014.0084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia P. H., Zhong F. L., Niwa S., Bonnard C., Utami K. H., Zeng R., et al. (2018). A Homozygous Loss-Of-Function CAMK2A Mutation Causes Growth Delay, Frequent Seizures and Severe Intellectual Disability. eLife 7 (May). 10.7554/eLife.32451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coultrap S. J., Bayer K. U. (2014). Nitric Oxide Induces Ca2+-independent Activity of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II (CaMKII). J. Biol. Chem. 289 (28), 19458–19465. 10.1074/jbc.M114.558254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Li J., Li T., Ji F., Bu X., Zhang N., et al. (2009). Propofol and Ketamine-Induced Anesthetic Depth-dependent Decrease of CaMKII Phosphorylation Levels in Rat Hippocampus and Cortex. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 21 (2), 145–154. 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31819ac2c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschenbaur L., Beck J., Kiyhankhadiv A., Mühlhauser M., Borgwardt S., Walter M., et al. (2016). Role of Calcium, Glutamate and NMDA in Major Depression and Therapeutic Application. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 64 (January), 325–333. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubovsky S. L., Daurignac E., Leonard K. E., Serotte J. C. (2015). Levetiracetam, Calcium Antagonism, and Bipolar Disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 35 (4), 422–427. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgersma Y., Fedorov N. B., Ikonen S., Choi E. S., Elgersma M., Carvalho O. M., et al. (2002). Inhibitory Autophosphorylation of CaMKII Controls PSD Association, Plasticity, and Learning. Neuron 36 (3), 493–505. 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01007-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson J. R. (2014). Mechanisms of CaMKII Activation in the Heart. Front. Pharmacol. 5 (April), 59. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenseth L. S. M., Gabrielsen M., Sylte I. (2020). The GABAB Receptor-Structure, Ligand Binding and Drug Development. Molecules 25 (13), 3093. 10.3390/molecules25133093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonano L. A., Sepúlveda M., Rico Y., Kaetzel M., Valverde C. A., Dedman J., et al. (2011). Valverde, John Dedman, Alicia Mattiazzi, and Martin Vila PetroffCalcium-Calmodulin Kinase II Mediates Digitalis-Induced Arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 4 (6), 947–957. 10.1161/circep.111.964908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell J. W. (2014). CaMKII: Claiming Center Stage in Postsynaptic Function and Organization. Neuron 81 (2), 249–265. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Huang F., Szymusiak M., Liu Y., Wang Z. J. (2015). Curcumin Attenuates Opioid Tolerance and Dependence by Inhibiting Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II α Activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 352 (3), 420–428. 10.1124/jpet.114.219303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvan C. A., Swedo S. E., Heuser J. S., Cunningham M. W. (2003). Mimicry and Autoantibody-Mediated Neuronal Cell Signaling in Sydenham Chorea. Nat. Med. 9 (7), 914–920. 10.1038/nm892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvan C. A., Swedo S. E., Kurahara D., Cunningham M. W. (2006a). Streptococcal Mimicry and Antibody-Mediated Cell Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Sydenham's Chorea. Autoimmunity 39 (1), 21–29. 10.1080/08916930500484757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirvan C. A., Swedo S. E., Snider L. A., Cunningham M. W. (2006b). Antibody-Mediated Neuronal Cell Signaling in Behavior and Movement Disorders. J. Neuroimmunol. 179 (1-2), 173–179. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küry S., van Woerden G. M., Besnard T., Onori M. P., Latypova X., Towne M. C., et al. (2017). De Novo Mutations in Protein Kinase Genes CAMK2A and CAMK2B Cause Intellectual Disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101 (5), 768–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu-Semenescu S., Le Corvec T., Groos E., Lavault S., Golmard J. L., Arnulf I. (2015). Lithium Therapy in Kleine-Levin Syndrome: An Open-Label, Controlled Study in 130 Patients. Neurology 85 (19), 1655–1662. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs U., Klein A. B., McSpadden E. D., Griem-Krey N., Solbak S. M. Ø., Houlton J., et al. (2021). GHB Analogs Confer Neuroprotection through Specific Interaction with the CaMKIIα Hub Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118 (31). 10.1073/pnas.2108079118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J., Schulman H., Cline H. (2002). The Molecular Basis of CaMKII Function in Synaptic and Behavioural Memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3 (3), 175–190. 10.1038/nrn753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayadevi M., Sherin D. R., Keerthi V. S., Rajasekharan K. N., Omkumar R. V. (2012). Curcumin Is an Inhibitor of Calcium/calmodulin Dependent Protein Kinase II. Bioorg Med. Chem. 20 (20), 6040–6047. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshul C. K., Tan S. E. (1994). Haloperidol-Induced Morphological Alterations Are Associated with Changes in Calcium/calmodulin Kinase II Activity and Glutamate Immunoreactivity. Synapse 18 (3), 205–217. 10.1002/syn.890180306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkatti N., Deshpande L. S., DeLorenzo R. J. (2008). Levetiracetam Inhibits Both Ryanodine and IP3 Receptor Activated Calcium Induced Calcium Release in Hippocampal Neurons in Culture. Neurosci. Lett. 436 (3), 289–293. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka S., Hough C. J., Chuang D.-M. (1998). Chronic Lithium Treatment Robustly Protects Neurons in the Central Nervous System against Excitotoxicity by Inhibiting N -methyl- D -aspartate Receptor-Mediated Calcium Influx. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 2642–2647. 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onal B., Unudurthi S. D., Hund T. J. (2014). Modeling CaMKII in Cardiac Physiology: From Molecule to Tissue. Front. Pharmacol. 5. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicena P., Schulman H. (2014). CaMKII Inhibitors: From Research Tools to Therapeutic Agents. Front. Pharmacol. 5 (February), 21. 10.3389/fphar.2014.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi S., Spagnoli C., Salerno G. G., Frattini D., Caraffi S. G., Trimarchi G., et al. (2020). Severe Intellectual Disability, Absence of Language, Epilepsy, Microcephaly and Progressive Cerebellar Atrophy Related to the Recurrent De Novo Variant p.(P139L) of the CAMK2B Gene: A Case Report and Brief Review. Am. J. Med. Genet. 182, 2675–2679. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushlow W. J., Seah C., Sutton L. P., Bjelica A., Rajakumar N. (2009). Antipsychotics Affect Multiple Calcium Calmodulin Dependent Proteins. Neuroscience 161 (3), 877–886. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki C., Frye R. E., Trifiletti R., Cooperstock M., Kaplan G., Melamed I., et al. (2020). Evaluation of the Cunningham Panel™ in Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infection (PANDAS) and Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS): Changes in Antineuronal Antibody Titers Parallel Changes in Patient Symptoms. J. Neuroimmunol. 339, 577138. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.577138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sills G. J., Rogawski M. A. (2020). Mechanisms of Action of Currently Used Antiseizure Drugs. Neuropharmacology 168 (May), 107966. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.107966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiraboschi E., Giambelli R., D'Urso G., Galietta A., Barbon A., de Bartolomeis A., et al. (2004). Antidepressants Activate CaMKII in Neuron Cell Body by Thr286 Phosphorylation. Neuroreport 15 (15), 2393–2396. 10.1097/00001756-200410250-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga H., Pardutz A., Vamos E., Bohar Z., Bago F., Tajti J., et al. (2009). Selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Attenuates Nitroglycerin-Induced Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II Alpha in Rat Trigeminal Nucleus Caudalis. Neurosci. Lett. 451 (2), 170–173. 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. (2014). Calcium Dysregulation, and Lithium Treatment to Forestall Alzheimer's Disease - a Merging of Hypotheses. Cell. Calcium 55 (3), 175–181. 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Huo J., Ding X., Yang M., Li L., Dai J., et al. (2017). Coenzyme Q10 Improves Lipid Metabolism and Ameliorates Obesity by Regulating CaMKII-Mediated PDE4 Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 8253. 10.1038/s41598-017-08899-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E., Schulman H. (1999). Structural Examination of Autoregulation of Multifunctional Calcium/calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II. J. Biol. Chem. 274 (37), 26199–26208. 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi G. W. (2015). Targeting Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels in Neurological and Psychiatric Diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 (1), 19–34. 10.1038/nrd.2015.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F., Li P., Chen S. R., Louis C. F., Fruen B. R. (2001). Dantrolene Inhibition of Ryanodine Receptor Ca2+ Release Channels. Molecular Mechanism and Isoform Selectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (17), 13810–13816. 10.1074/jbc.M006104200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.