Purpose and Scope of This Practice Guidance

This is the first American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) practice guidance on the management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis. This guidance represents the consensus of a panel of experts after a thorough review and vigorous debate of the literature published to date, incorporating clinical experience and common sense to fill in the gaps when appropriate. Our goal was to offer clinicians pragmatic recommendations that could be implemented immediately in clinical practice to target malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in this population.

This AASLD guidance document differs from AASLD guidelines, which are supported by systematic reviews of the literature, formal rating of the quality of the evidence and strength of the recommendations, and, if appropriate, meta-analysis of results using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation system. In contrast, this guidance was developed by consensus of an expert panel and provides guidance statements based on formal review and analysis of the literature on the topics, with oversight provided by the AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee at all stages of guidance development. The AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee chose to perform a guidance on this topic because a sufficient number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were not available to support the development of a guideline.

Definitions of Malnutrition, Frailty, and Sarcopenia and Their Relationship in Patients With Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is a major predisposing condition for the development of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Multiple, yet complementary, definitions of these conditions exist in the published domain outside of the field of hepatology; but consensus definitions have not yet been established by the AASLD for patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, there has been ambiguity related to operationalization of these constructs in clinical practice. To address this, we offer definitions of the theoretical constructs of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia as commonly represented in all populations, partnered with operational definitions, developed by consensus, to facilitate pragmatic implementation of these constructs in clinical practice as applied to patients with cirrhosis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Definitions for the Theoretical Constructs of Malnutrition, Frailty, and Sarcopenia and Consensus-Derived Operational Definitions Applied to Patients with Cirrhosis

| Construct | Theoretical Definitions | Operational Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Malnutrition | A clinical syndrome that results from deficiencies or excesses of nutrient intake, imbalance of essential nutrients, or impaired nutrient use(4) | An imbalance (deficiency or excess) of nutrients that causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size, composition) or function and/or clinical outcome(1) |

| Frailty | A clinical state of decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors(2) | The phenotypic representation of impaired muscle contractile function |

| Sarcopenia | A progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes including falls, fractures, disability, and mortality(3) | The phenotypic representation of loss of muscle mass |

Malnutrition is a clinical syndrome that results from “an imbalance (deficiency or excess) of nutrients that causes measurable adverse effects on tissue/body form (body shape, size, composition) or function, and/or clinical outcome.”(1) Key to this definition is the recognition that malnutrition represents a spectrum of nutritional disorders across the entire range of body mass index (BMI)—from underweight to obese. By this definition, malnutrition leads to adverse physical effects, which, in patients with cirrhosis, are commonly manifested phenotypically as frailty or sarcopenia.

Frailty has most commonly been defined as a clinical state of decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to health stressors, a definition that has its roots in the field of geriatrics.(2) However, the weight of evidence available to date in patients with cirrhosis has focused predominantly on one component of frailty: physical frailty. Although this representation deviates somewhat from the classic “geriatric” definition of frailty as a global construct, physical frailty represents clinical manifestations of impaired muscle contractile function that are commonly reported by patients with cirrhosis such as decreased physical function, decreased functional performance, and disability.

Sarcopenia has been defined by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia as “a progressive and generalized skeletal muscle disorder associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes including falls, fractures, disability, and mortality,” combining both muscle mass and muscle strength or muscle performance in its definition.(3) However, the majority of studies in patients with cirrhosis have investigated sarcopenia using measures of muscle mass alone. Therefore, based on the evidence available to date on patients with cirrhosis, we have developed a consensus definition for operationalization of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis as the phenotypic manifestation of loss of muscle mass.

Although we have, for the purposes of this guidance, developed separate operational definitions for malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia, we acknowledge that these three constructs are interrelated and in practice are often recognized simultaneously in an individual patient. For example, a patient with cirrhosis who presents to clinic with severe muscle wasting might be described as “malnourished,” “frail,” and “sarcopenic,” each descriptor conveying similar information about the patient’s poor clinical condition and prognosis. Despite the overlap of these three constructs in clinical practice, there is value in understanding each as a separate entity as well as the relationship between the three in order to develop tailored behavioral interventions and targeted pharmacotherapies for these conditions.

Herein, we propose a conceptual framework for this relationship (Fig. 1). There are a number of factors that lead to malnutrition in patients with cirrhosis, which is challenging to identify at the bedside unless it manifests phenotypically as frailty and/or sarcopenia. Malnutrition is not the only factor that contributes to frailty and sarcopenia; other factors such as cirrhosis complications, other systems-related factors (e.g., systemic inflammation, metabolic dysregulation), physical inactivity, and environmental/organizational factors can contribute to frailty and/or sarcopenia within or independent of the malnutrition pathway. In addition, frailty and sarcopenia can contribute to each other—impaired muscle contractile function can accelerate loss of muscle mass and vice versa. It is these clinical phenotypes—frailty and sarcopenia—that ultimately lead to adverse health outcomes including hepatic decompensation, increased health care use, worse health-related quality of life, adverse posttransplant outcomes, and increased overall risk of death.

FIG. 1.

Factors contributing to malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia and the relationship between these three constructs. Cirrhosis-related and other systems-related factors, along with physical inactivity and environmental/organizational factors, contribute to malnutrition—which then leads to frailty and sarcopenia. These factors can also contribute directly to frailty and sarcopenia independently of malnutrition.

Factors That Contribute to Frailty and Sarcopenia in Patients With Cirrhosis

Here, we describe the factors that have been shown to contribute to frailty and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis. We acknowledge that these factors are, in some cases, interrelated; but for the purposes of ease of clinical implementation, we have categorized these factors broadly as (1) malnutrition, (2) cirrhosis-related, (3) other systems–related, (4) physical inactivity, and (5) environmental/organizational factors.

MALNUTRITION

Impaired Intake of Macronutrients

Reduced oral intake results from many factors including early satiety, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, dysgeusia, diet unpalatability (e.g., low sodium or low potassium), impaired level of consciousness, free water restriction, and frequent fasting due to procedures and hospitalizations.(5) Excess oral intake is a root cause of obesity and is influenced by a variety of biological, sociocultural, and psychological factors.(6) Many patients with cirrhosis have limited knowledge about disease self-management, including nutrition therapy.(7,8) Inadequate food knowledge/preparation skills and food insecurity can impact dietary intake—through either reduced or excess intake—across the spectrum of nutritional disorders from undernutrition to obesity.(7-9)

Impaired Intake of Micronutrients

Malabsorption leads to high rates of micronutrient deficiency in patients with cirrhosis. Factors leading to impaired macronutrient intake and absorption also contribute to deficiency of many micronutrients. In particular, folate, thiamine, zinc, selenium, vitamin D, and vitamin E deficiencies have been reported in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease; and fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies have been well documented in patients with cholestatic liver disease.(10-14) Several of these micronutrients have a strong link with frailty or sarcopenia. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with impaired muscle contractile function in the general population.(15) Although studies evaluating the role of vitamin D deficiency on frailty and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis are lacking, vitamin D deficiency is prevalent in patients with cirrhosis(16-18) and may contribute to the development and progression of frailty in this population. Deficiency of zinc, a cofactor in the urea cycle that metabolizes ammonium, is associated with HE, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis.(19-21) Magnesium deficiency occurs because of malabsorption of magnesium in the small intestine and is exacerbated by diuretic use. Magnesium deficiency is associated with reduced cognitive performance as well as reduced muscle strength in adults with cirrhosis(22-24) and with increased bone resorption in children with cholestatic liver disease.(25)

Impaired Nutrient Uptake

Impaired nutrient uptake is multifactorial, resulting from malabsorption, maldigestion, and altered macronutrient metabolism. Cholestasis leads to alterations in the enterohepatic circulation of bile salts and maladaptation of bile salt regulation. This may result in elevated serum and tissue levels of potentially toxic bile salts as well as impaired metabolism and malabsorption of long-chain fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamin deficiency in both adults and children.(26-28) Other contributors to malabsorption and maldigestion in patients with cirrhosis include portosystemic shunting, pancreatic enzyme deficiency, bacterial overgrowth, altered intestinal flora, and enteropathy.(5) Altered macronutrient metabolism or “accelerated starvation” occurs as a result of reduced hepatic glycogen synthesis and storage during the postprandial state, an early shift from glycogenolysis to gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and increased rates of whole-body protein breakdown.(29,30) Hypermetabolism has been variably defined in the literature (e.g., resting energy expenditure [REE] + 1 SD or REE:REE predicted + 2SD).(31,32) With its associated catabolic state, hypermetabolism also contributes to the imbalance between intake and requirements, occurring in at least 15% of patients with cirrhosis without a clear correlation of hypermetabolism with disease severity or other predictors.(32,33)

CIRRHOSIS-RELATED

Cirrhosis itself leads to frailty and sarcopenia through a number of pathways. At the pathophysiological level, the altered catabolic state in cirrhosis leads to an imbalance between energy needs and intake. Altered protein metabolism, particularly of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) that are essential for supporting glutamine synthesis and extrahepatic ammonia detoxification, results in reduced levels of circulating BCAAs, which leads to accelerated muscle breakdown.(34-36) Impaired hepatic ammonia clearance from loss of metabolic capacity, in combination with increased portosystemic shunting, increases systemic ammonia concentration with pathologic effects on the muscle.(37-39) Ammonia is myotoxic through mechanisms that include decreased protein synthesis, increased autophagy, proteolysis, and mitochondrial oxidative dysfunction in the skeletal muscle. Posttranslational modifications of contractile proteins with bioenergetic dysfunction result in muscle contractile dysfunction and loss of muscle mass.(40-42)

The etiology of liver disease has been associated with differences in the prevalence of sarcopenia.(43,44) For example, alcohol-associated liver disease has been associated with a particularly high prevalence of sarcopenia, affecting 80% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis—although sarcopenia was reported in approximately 60% of patients with cirrhosis from NASH, chronic HCV, and autoimmune hepatitis.(45) Patients with alcohol-associated cirrhosis display the most rapid rate of reduction in muscle areas compared with other etiologies.(43) Alcohol exposure increases muscle autophagy, inhibits proteasome activity, and decreases the anabolic hormone insulin-like growth factor 1.(46-48) Patients with cirrhosis secondary to NASH may be at increased risk of sarcopenia due to the additive effects of insulin resistance and chronic systemic inflammation.(49) Finally, cholestasis-predominant liver diseases, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, lead to elevated serum bile acid levels that may induce skeletal muscle atrophy through the bile acid receptor G protein–coupled bile acid receptor 1 (or TGR5) that is expressed in healthy muscles.(50)

Complications of portal hypertension also contribute to malnutrition and muscle dysfunction. HE is associated with anorexia, reduced physical activity, and frequent hospitalizations.(37,51) Ascites contributes to anorexia, early satiety, increased REE, and limited physical activity.(52,53) Both HE and ascites are strongly associated with frailty.(54)

OTHER SYSTEMS

Systemic Inflammation, Endocrine Factors, Metabolic Dysregulation, and Other Aging-Related Conditions

Circulating levels of inflammatory markers such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-10, C-reactive protein, and TNF-α are elevated in patients with cirrhosis.(55,56) Low-grade endotoxemia may result from increased gut permeability, from impaired hepatic clearance of lipopolysaccharide and portosystemic shunting, and potentially from cirrhosis-related changes in the gut microbiome.(57) This chronic systemic inflammation may promote the development of frailty, sarcopenia, and their subsequent complications through reduced muscle protein synthesis and increased protein degradation.(58-61)

Even in the absence of cirrhosis, chronic liver disease may lead to systemic inflammation and vulnerability to developing frailty and sarcopenia. Inflammatory cytokines are elevated in chronic HCV; eradication of HCV with antiviral agents results in a decrease of these markers.(62,63) Both alcohol-associated liver diseases and NAFLDs are also characterized by elevated systemic inflammatory markers.(64)

Further disruption of mediators of the “liver–muscle axis” may result from cirrhosis-related reduction in circulating levels of testosterone and changes in growth hormone secretion and sensitivity.(65) Low testosterone levels have been observed in male patients with cirrhosis and sarcopenia compared with patients who are nonsarcopenic.(66) Testosterone replacement resulted in improvements in total lean body mass,(67) further supporting the role of low testosterone in the development and progression of sarcopenia.

Obesity has been associated with frailty and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis and is of increasing relevance given the rapidly rising prevalence of obesity-related liver diseases.(6,68-71) Obesity is associated with metabolic dysregulation, visceral fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and anabolic resistance. A strong link has been demonstrated between obesity and muscle loss in patients with cirrhosis, with nearly one third of patients with obesity and cirrhosis meeting criteria for sarcopenia by skeletal muscle index (SMI).(70) With regard to muscle function, obesity has not been associated with an increased rate of frailty, although one multicenter study of patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation did demonstrate a significant interaction between obesity and frailty on clinical outcomes: patients with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 who were frail experienced a 3-fold increased risk of waitlist mortality compared with similar-weight patients who were nonfrail.(68)

Consistent with the general population, there has been a rapid rise in the prevalence of cirrhosis in older adults.(72) In older adults with cirrhosis, a combination of primary (aging-related) and secondary (chronic disease–related) sarcopenia occurs simultaneously and has been referred to as “compound sarcopenia.”(73) In hospitalized patients, compound sarcopenia was associated with higher odds of death (OR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) and greater resource use (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) than patients with cirrhosis but without compound sarcopenia.(73)

Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity and sedentary behavior are common in patients with cirrhosis and are associated with frailty and sarcopenia as well as mortality.(74-76) In one small study of 53 liver transplant candidates, participants spent 76% of their waking hours in sedentary time and completed a mean of only 3,000 steps per day.(76) Physical inactivity was significantly higher among liver transplant candidates who experienced waitlist mortality than in those who experienced other outcomes on the waitlist (e.g., transplant, removed for social reasons, or still waiting).(75) In a survey of liver transplant candidates and their caregivers, only 60% of patients and caregivers reported feeling that their clinicians “encouraged exercise,”(77) suggesting that one possible barrier to engaging in physical activity is the patient–provider communication around the benefits of physical activity.

There are no prospective longitudinal studies evaluating the direct role of physical inactivity on progressive frailty and/or sarcopenia. However, a number of trials have demonstrated a benefit of interventions to increase physical activity (in combination with nutritional counseling) on muscle function, muscle mass, and functional capacity.(78-82) These studies suggest that physical inactivity may, in part, contribute to decline in muscle function and/or muscle mass.

Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health—that is, where we live, learn, work, and play(83)—also play a role in the development of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Health literacy is primarily governed by socioeconomic factors and is associated with physical frailty among liver transplant candidates.(84) Food insecurity owing to social factors such as poverty, isolation, or limited access to nutritious food is associated with advanced liver disease in patients with NAFLD.(85) Financial strain may limit caregiver presence in the home, resulting in limited monitoring, limited supervision for physical activity, and less attentive management of cirrhosis complications (e.g., timely lactulose therapy for HE). Conversely, increased patient needs impact caregiver productivity and earning potential. Some caregivers of patients with cirrhosis lose employment,(86) potentially worsening financial strain and thus the ability to provide adequate nutrition and management of cirrhosis complications that contribute to malnutrition.

Organizational Factors

Factors at the local, community, and national levels can exacerbate the development of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in this population. Community-level barriers to access to nutritious food may accelerate the development of all of these factors, including obesity, in some populations and drive adverse outcomes. In pediatric liver transplant recipients, neighborhood deprivation, an administrative metric of socioeconomic status, has been shown to be independently associated with mortality.(87) Given the complexity of managing patients with cirrhosis, there may be insufficient time during clinical visits to devote to identifying factors and developing strategies to target the contributing causes. Although a referral to, or comanagement with, a registered dietician with expertise in managing patients with advanced liver disease is ideal, some health care systems may not offer this resource or allow for longitudinal follow-up to assess for response to treatment recommendations. Furthermore, there may be confusion about which provider is responsible for management (e.g., primary care physician, hepatologist, registered dietician), despite the importance of a multimodal, multidisciplinary approach.

Clinical Manifestations of Muscle Dysfunction: Frailty and Sarcopenia

FRAILTY

Assessment of Frailty in Adults and Children

Tools to assess frailty as a multidimensional construct (e.g., global frailty) or its individual components (e.g., physical frailty, disability, functional status) that have been studied in adults or children with cirrhosis are listed in Table 2.(115-128) The tools are organized in the table from subjective, survey-based tools assessed by the patient, caregiver, or clinician to objective, performance-based assessments. The majority of these tools have been studied in the ambulatory setting only, underscoring the original “geriatric” construct of frailty as a chronic state of decreased physiologic reserve. However, the strong prognostic value of the two tools that have been studied in the acute care setting—activities of daily living (ADLs) and Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS)—highlights the pragmatic need for tools to measure the effects of frailty and sarcopenia in patients with acute cirrhosis complications.

TABLE 2.

Tools to Assess Frailty or Individual Frailty Components that have been Studied in Patients with Cirrhosis

| Tool | Setting Studied |

Administration Time |

Equipment Needed | Component(s) of Frailty Measured |

Details Regarding Administration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective→-----------------------------------------------------------←subjective | Clinical Frailty Scale(96,115) | Ambulatory inpatient | <1 minute | None | Global frailty | Rapid survey-based instrument using clinician assessment on a scale of 1-9 where 1 = very fit, 5 = mildly frail, and 9 = terminally ill |

| ADLs (97,100,113) | Ambulatory inpatient | 2-3 minutes | None | Ability to conduct basic tasks to function within one’s home | Patient or caregiver assesses difficulty or dependence with six activities that are essential to function within one’s home (e.g., basic hygiene, eating, ambulation) | |

| KPS(88,89,116,117) | Ambulatory inpatient | <1 minute | None | Ability to carry out normal ADLs | Patient, caregiver, or clinician assesses functional limitations ranging from 100 (normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease) to 50 (requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care) to 10 (moribund, fatal processes progressing rapidly). | |

| Lansky Play-Performance Scale(94) | Ambulatory inpatient | <1 minute | None | Usual play activity in children | Studied in children aged 1-17 years listed for liver transplant. Similar to KPS scale ranging from 100 (fully active, normal) to 50 (lying around much of the day, no active playing but participates in all quiet play and activities) to 10 (does not play) | |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group(103,104,118-121) | Ambulatory | <1 minute | None | Ability to carry out normal ADLs | Patient, caregiver, or clinician assesses functional limitations ranging 0-5, where 0 = asymptomatic, 2 = < 50% in bed during the day, and 4 = bedbound. | |

| Fried Frailty Instrument(75,106) | Ambulatory | 5-10 minutes | Hand dynamometer,stopwatch,tape measure | Physical frailty | Consists of five domains: (1) weight loss (question), (2) exhaustion (question), (3) slowness (short gait speed), (4) weakness (hand grip strength), and (5) low physical activity level (questionnaire) | |

| Modified Fried Frailty Instrument(93) | Ambulatory | 60 minutes | Hand dynamometer,stopwatch,tape measure | Physical frailty | Developed for children with chronic liver disease aged 5-17 years. Consists of five domains: (1) weight loss (triceps skinfold thickness), (2) exhaustion (questionnaire), (3) slowness (gait speed), (4) weakness (grip strength), and (5) low physical activity (questionnaire) | |

| Hand grip strength(122,123) | Ambulatory | 2-3 minutes | Hand dynamometer | Physical frailty | The patient is asked to grip a dynamometer using the dominant hand with their best effort. The test is repeated 3 times, and the values are averaged. | |

| Short gait speed(105) | Ambulatory | ~1 minute | stopwatch, tape measure | Functional mobility | One of the components of the Short Physical Performance Battery | |

| 6-minute walk test(107) | Ambulatory | 6 minutes | Stopwatch, tape measure | Submaximal aerobic capacity and endurance | Distance walked on a flat surface at usual walking speed within 6 minutes | |

| Short Physical Performance Battery(75) | Ambulatory | ~3 minutes | Stopwatch,tape measure, chair | Lower extremity physical function | Consists of three components: (1) 8-foot gait speed, (2) timed chair stands (5 times), and (3) balance testing three positions (feet together, semitandem, tandem) for 10 seconds each | |

| Liver Frailty Index(54,90-92,124-127) | Ambulatory inpatient | ~3 minutes | Stopwatch, hand dynamometer, chair | Physical frailty | Cirrhosis-specific tool consisting of grip strength, chair stands, and balance testing. Changes in Liver Frailty Index are associated with outcomes. | |

| Cardiopulmonary exercise test(102,108,128) | Ambulatory | 60 minutes | Cardiopulmonary stress diagnostic system | Maximal aerobic capacity | Noninvasive test of functional capacity through measurement of gas exchange at rest and during exercise to evaluate both submaximal and peak exercise responses |

Some scales have validated thresholds to grade the severity of frailty. Specifically, patients can be categorized as having high, moderate, or low performance status using KPS thresholds of 80-100, 50-70, or 10-40, respectively.(88,89) The Liver Frailty Index also has established cut-points to define robust (Liver Frailty Index < 3.2), prefrail (Liver Frailty Index 3.2-4.3), and frail (Liver Frailty Index ≥ 4.4).(90,91) Poor performance according to some scales (e.g., ADLs), however, suggests a greater burden of functional deficits than others (e.g., walk speed). The only tools that have also evaluated the associations between longitudinal assessments and outcomes in patients with cirrhosis are the KPS scale and the Liver Frailty Index.(88,92)

When it comes to assessing frailty in children, the well-established tools for assessment of frailty in adults are challenging to administer given the need for participation in the tests (either by survey or by performance) and consideration of age-related and sex-related norms. However, a few studies have demonstrated that the concept of frailty has clear applicability to children with chronic liver disease. The traditional Fried frailty phenotype, developed in older adults and validated in patients with cirrhosis of all ages, has been modified for children.(93) Although assessment of frailty was feasible in this cohort of children 5-17 years of age, the majority of children undergoing liver transplantation are too young to use the Modified Fried Frailty Instrument (median age 18 years), highlighting the need to derive an objective pediatric frailty assessment tool for children < 2 years of age. One promising metric is the Lansky Play-Performance Scale, a measure of global functional status developed for children with cancer aged 1-16 years, which can be assessed by the patient, caregiver, or clinical provider.(94) Gaps remain in the measurement of muscle contractile function among those < 1 year of age.

Prevalence and Natural History

Frailty is common among patients with cirrhosis; its prevalence increases with liver disease severity. Estimates of frailty prevalence in this population have varied because of the use of a number of different tools to capture impaired muscle contractile function. Among patients with cirrhosis in the ambulatory setting, the reported prevalence of frailty has ranged from 17% to 43%.(54,75,95,96) Among hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, the prevalence of frailty is as high as 38% for inpatients with HE (and 18% for those without HE) when measured as disability using the ADL tool.(97,98) Rates of frailty have been reported to be as high as 68% when measured as impaired performance status using the KPS scale.(89) Using the Modified Fried Frailty Instrument, 24% of children with chronic liver disease met the criteria for frailty, with rates as high as 46% among children with more advanced/end-stage liver disease.(93)

Frailty worsens in the majority of patients with cirrhosis over time.(88,92) Among patients awaiting liver transplantation in the United States, < 20% displayed improved or stable KPS scores.(88) After liver transplantation, at least 90% experience some improvement in their KPS scores, with a median improvement of 20% by 1 year posttransplant.(88) Frailty, as measured by the Liver Frailty Index, improved in only 16% of 1,093 patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation during a median follow-up time of 10.6 months on the waitlist.(92) At 3, 6, and 12 months after liver transplantation, Liver Frailty Index scores worsened from pretransplant values in 59%, 41%, and 32% of patients, respectively. Only 20% of patients achieved functional “robustness” as defined by a Liver Frailty Index score of ≤ 3.2 by 1 year after liver transplantation.(99)

Association With Outcomes

Frailty has been strongly linked with mortality in both the ambulatory and acute care settings as well as the posttransplant setting.(54,75,88,89,92-94,96,97,100-108) For example, frailty, by the Liver Frailty Index, was associated with a nearly 2-fold increased adjusted risk of death in a study of > 1,000 ambulatory patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation at 9 US centers (sub-HR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.31-2.52).(54) In another study including 734 hospitalized patients with cirrhosis, disability, as assessed by the need for some assistance with three or more ADLs, was associated with a nearly 2-fold increased adjusted odds of 90-day mortality (OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.05-3.20).(97) In the posttransplant setting, compromised functional performance, by the KPS score, was associated with higher HRs for death after liver transplantation (for KPS 50%-70%: HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.13-1.24; for KPS 10%-40%: HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.35-1.52).(88)

Importantly, changes in frailty over time—both worsening and improvement—are informative of mortality risk.(88,92) Among 1,093 patients with cirrhosis at eight US sites, each 0.1 unit change in the Liver Frailty Index over 3 months was associated with a 2-fold increased hazard of waitlist mortality (HR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.35-3.09), independent of baseline frailty and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium (MELD-Na) score. Cumulative rates of waitlist mortality at 6 months were 12.1% among those who experienced severe worsening compared with 7% among those who remained stable. Although this was a purely observational study, it is worth noting that those who displayed improved frailty scores demonstrated a 6-month cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality of only 0.6%, suggesting the potential benefit of interventions targeting frailty to reduce mortality in this population.(92)

Baseline frailty measures have been linked with outcomes other than mortality. These outcomes include metrics of health care use in both ambulatory patients (e.g., unplanned hospitalizations, health care costs, recovery of physical function after liver transplantation) and hospitalized patients (e.g., readmissions, prolonged length of stay, discharge to a rehabilitation facility).(89,97,99,105,109) Furthermore, frailty is strongly associated with patient-reported outcomes, including development of falls, depression, disability, and global health-related quality of life.(109-114)

SARCOPENIA

Assessment of Sarcopenia in Adults and Children

Methods to assess muscle mass in patients with cirrhosis are detailed in Table 3.(171-178)

TABLE 3.

Tools to Assess Muscle Mass that have been Studied in Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease

| Method | Equipment Needed |

Advantages | Disadvantages | Outcomes Studied | Summary Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics(142,171) (MAMC, triceps skinfold thickness) | Tape measure, skinfold thickness, calipers | Safe, rapid, bedside tool, accessible, minimal training, repeatable | Low reproducibility; affected by fluid overload, adipose tissue loss; weak correlation with cross-sectional imaging | Concordance between DEXA and CT, post–liver transplant morbidity and mortality | Practical for large patient populations but poor accuracy and precision; interpret with caution |

| Anthropometrics (pediatric)(150) | Comparison between MAMC and CT | ||||

| BIA(135-139) | BIA device | Safe, rapid, accessible, minimal to moderate training, repeatable | Strict parameters around nutritional intake and exercise before the test, positioning challenging in patients with obesity | Hepatic decompensation, pretransplant mortality | Fluid retention may impact the reliability of lean body mass estimates; data using phase angle show good reliability even in patients with fluid retention |

| Ultrasound(165,172,173) | Ultrasound device |

Safe, rapid, accessible, repeatable | Operator-dependent, challenging in patients with obesity, lack of normative data | Ultrasound of psoas compared with CT-based SMI, hospitalizations and mortality, severity of liver disease | More data are needed to standardize technique; able to provide echogenicity data for tissue integrity |

| MRI(134,174) | MRI machine, image analysis software | Accurate, no radiation, measures muscle quantity and quality | Costly, limited availability | Validated against CT imaging, acute-on-chronic liver failure and mortality | Muscle mass has been defined by fat-free muscle area |

| DEXA(142,144,145,158,175) | DEXA scanner | Safe, rapid | Radiation exposure (low),edema can limit accuracy | Mortality | Low concordance between DEXA and CT in patients with cirrhosis DEXA appendicular mass improves accuracy compared with CT |

| CT(131,154,157,159,160,166,169,176,177) | CT scanner, image analysis software | Accurate, rapid, measures muscle quantity and quality, requires a high level of training to interpret | Radiation exposure, not available at bedside, varying cut-points/sites of measurement, not easily repeatable | Waitlist mortality, posttransplant mortality, decompensation, acute care use, quality of life | Has the most evidence to support its use but has challenges with radiation exposure and repeatability Muscle mass measures that have been studied:

|

| CT (pediatric)(150-152,155,156,178) | Comparison between MAMC and CT, comparison with healthy children, motor delay, infections, hospitalizations |

CT imaging is currently the gold standard for assessment of muscle mass in cirrhosis, but cost and exposure to ionizing radiation make routine use of CT solely for the purpose of detecting sarcopenia impractical in many clinical settings.(129) However, when abdominal CT imaging is performed for clinical reasons—such as in patients with HCC or for surgical planning (e.g., transplant, hepatectomy)—muscle mass measurement can be obtained from clinical scans using readily available quantitative morphomics software.(130) Muscle mass is conventionally reported as the SMI, calculated as the total skeletal muscle area at L3 normalized to height.(131) Total psoas muscle area has also been studied in patients with cirrhosis (along with psoas muscle index, calculated as total psoas muscle area normalized to height) but has been shown to be less strongly correlated with total body protein as determined by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) than skeletal muscle area.(132) Furthermore, psoas muscle index led to greater misclassification of mortality risk in adult patients with cirrhosis when compared with SMI.(133) Quantitative morphomics by MRI is less well studied in patients with cirrhosis but offers the same theoretical advantages as CT-based measures of muscle mass (and is often more costly and less readily available in resource-limited settings).(134)

Measures of muscle mass other than cross-sectional imaging have been studied in patients with cirrhosis. Assessment of fat-free mass by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), including segmental BIA, has been shown to modestly correlate with muscle mass and is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis.(71,135-140) Fluid retention impacts the reliability of lean body mass estimates by BIA.(141) Phase angle measurements have good reliability in patients with cirrhosis, even among those with ascites.(136) Availability of BIA devices for routine clinical practice is currently limited, although availability of portable BIA devices may increase the acceptability of BIA measures of body composition. Other methods to assess muscle mass, such as DEXA scanning or anthropometrics, may be more available in some practice settings worldwide but have limitations in patients with cirrhosis due to fluid retention in certain body compartments.(138,142-145) Anthropometrics, although valuable in pediatric populations,(146) are vulnerable to high interobserver variability and the inability to distinguish different body compartments (lean versus fat mass), which is of particular relevance given increasing rates of obesity in populations with cirrhosis.(142)

Sarcopenia assessment is particularly useful in the pediatric population because muscle contractile function can be difficult to assess in young children. Measures of muscle mass can provide an objective measure of growth because anthropometric measures such as weight, BMI, midarm circumference, triceps skin fold thickness, and serum markers such as albumin are often confounded by concurrent ascites, peripheral edema, and organomegaly.(147-149) This is particularly relevant in infants, for whom ascites limits the value of standard anthropometric measurements. Similar to adults, CT imaging with quantitative morphomics provides the most accurate assessment of muscle mass, with more data supporting the use of total psoas muscle versus total skeletal muscle mass, including reference values for children aged 1-16 years.(147,150-152) Longitudinal measurements, including rate of change, are even more relevant given the dynamic changes with development in children.

Prevalence

Sarcopenia is common in adults with cirrhosis, affecting 30%-70% of patients with end-stage liver disease.(153) Similar to the general population, there are strong sex-based differences in the prevalence of sarcopenia, with 21% of women and 54% of men with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation meeting criteria for sarcopenia by SMI in one large multicenter study.(131) The degree of muscle loss correlates with severity of liver disease in men but not women.(154) In children, sarcopenia has been reported in 17%-40% of those with end-stage liver disease.(151,155,156)

Association With Outcomes

Studies investigating sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis have largely focused on muscle mass assessments in the ambulatory setting. Sarcopenia has been shown to be a robust predictor of a wide spectrum of outcomes in adults with cirrhosis both with and without HCC.(70,73,131,142,147,151,154,157-165) These outcomes have included not only mortality both before and after liver transplantation(131,160,161) but also hepatic decompensation,(166) reduced quality of life, (167) increased risk of infection,(157) and prolonged hospitalization.(44,73,168) In a meta-analysis of 3,803 liver transplant candidates across 19 studies in partly overlapping cohorts published between 2000 and 2015, “sarcopenia,” as defined by a wide range of CT-assessed skeletal muscle mass cut-points, was associated with a pooled HR of 1.72 (95% CI, 0.99-3.00) for waitlist mortality and 1.84 (95% CI, 1.11-3.05) for posttransplant mortality.(159) A separate North American multicenter cohort of nearly 400 patients with cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation identified SMI cut-points to predict waitlist mortality: < 39 cm2/m2 in women and < 50 cm2/m2 in men.(131,169) These SMI cut-points were further validated in a separate cohort of all White patients.(131,169) Although the original derivation cohort consisted of patients with liver transplants in the ambulatory setting at five centers in North America, it predominantly consisted of non-Hispanic and Hispanic White patients, so additional validation in more diverse cohorts is warranted to evaluate the prognostic value of SMI across all populations. Most studies to date have used a static measure of sarcopenia, but recent data suggest that sarcopenia is progressive and that dynamic measures of rate of muscle loss from serial/longitudinal measures are predictors of clinical outcomes.(43)

In children with end-stage liver disease, sarcopenia has been associated with adverse outcomes including growth failure, hospitalizations, infections, and motor delay.(151,155,156)

Sarcopenic Obesity

“Sarcopenic obesity” refers to the state of decreased muscle mass in the setting of increased fat mass. This phenotype presents a unique clinical challenge in that it can be difficult to detect without dedicated testing because fat mass can mask underlying muscle wasting.(6) The prevalence of sarcopenic obesity in patients with cirrhosis ranges from 20% to 35%.(70,71,139) NAFLD has been shown to be a strong risk factor for sarcopenic obesity, even after adjustment for metabolic comorbidities.(69,170) Sarcopenic obesity, defined as low sex-adjusted SMI and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with cirrhosis.(70,139) Rates of sarcopenic obesity are likely to increase as cirrhosis related to NAFLD increases.

Practical Considerations for Assessing Frailty and Sarcopenia in Clinical and Research Settings

Measures of muscle mass, particularly by cross-sectional imaging, have the advantage of being objective, reliable, and more easily reproducible than measures of muscle function. However, despite the prognostic importance of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis, its clinical use is currently hampered by the lack of inexpensive, safe, and readily available tests for assessment. On the other hand, many tools to assess frailty can be administered quickly in the ambulatory setting and at low cost and, perhaps most importantly, can be repeated at follow-up intervals. Furthermore, measures of muscle contractile function may be more closely associated than measures of muscle mass, with additional patient-reported outcomes including depression and the ability to complete basic life activities.(98,111,113,179,180)

For the purposes of clinical practice, one tool does not fit all. The choice of whether to measure frailty or sarcopenia (or both) depends on the specific clinical scenario and resources available. Given the ease, low cost, and repeatability of frailty metrics, we recommend routine assessment of frailty using a standardized tool—from which there are many to choose (Table 2)—in all ambulatory patients with cirrhosis. Assessment of muscle mass, on the other hand, may be useful in select groups, especially those in whom measures of frailty are unobtainable or unreliable. Such groups may include hospitalized patients, who often cannot perform performance-based tests of muscle contractile function. In this setting, preserved muscle mass may be an indicator of underlying physiologic reserve and suggest high potential for reversal of the patient’s acute presentation. Children with end-stage liver disease represent another subgroup in whom assessment of muscle mass may be more useful than measures of muscle contractile function given the limitations of performance-based testing in very young individuals (including infants).

For the purposes of research, frailty and sarcopenia represent important and complementary endpoints because they are robust and consistent predictors of outcomes in patients with cirrhosis. Given that the pathophysiology of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis is better elucidated than frailty,(57) sarcopenia may offer more precise mechanistic targets for drug development. In addition, assessment of muscle mass does not require active patient participation and therefore may be more appropriate as a research tool in patients who are critically ill and immobilized (e.g., on mechanical ventilation). However, frailty has the advantage of directly measuring how an individual functions and correlating strongly with how the individual feels, so frailty may be a more direct measure of a patient’s quality of life than sarcopenia. For these reasons, we recommend the inclusion of both frailty and sarcopenia as complementary endpoints in research studies.

Interventions

ALGORITHM FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF MALNUTRITION, FRAILTY, AND SARCOPENIA IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

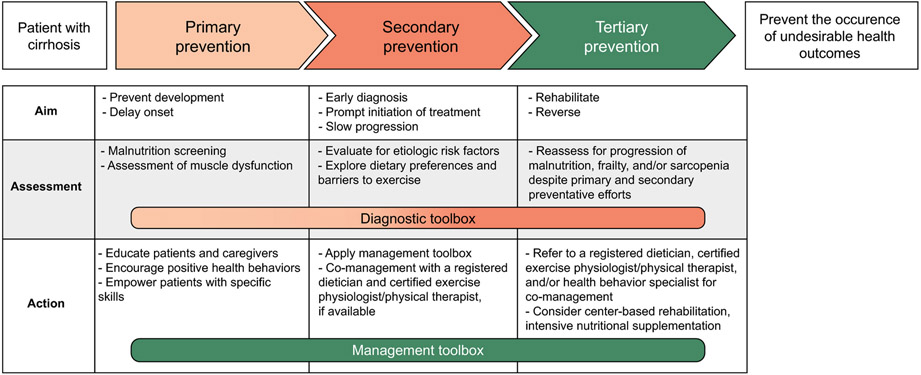

Ideally, all patients with cirrhosis would receive intensive efforts to preserve muscle mass and contractile function on diagnosis of cirrhosis, but we recognize that this is not practical in most clinical settings given resource limitations. In an effort to guide the greatest resource allocation to those with the greatest need, we have grounded our recommendations within a classic three-level framework for disease prevention and health promotion, with each level representing different aims at different stages of disease requiring increasing intensities of assessment and action (Fig. 2). “Primary prevention” refers to routine screening to identify patients with sarcopenia or frailty. “Secondary prevention” refers to the initiation of therapy in patients diagnosed with sarcopenia or frailty. “Tertiary prevention” refers to the intensification of therapy in patients with sarcopenia or frailty not responding to first-line therapy. The ultimate goal is to prevent the occurrence of adverse health outcomes attributable to malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia.

FIG. 2.

The three levels of disease prevention and health promotion as applied to management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis.

Using this framework, we have developed a clinical practice algorithm for screening, assessment, and management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis (Fig. 3). Key to this algorithm is the importance of reassessment of malnutrition risk, frailty, and sarcopenia—whether it be rescreening for the development or evaluating for worsening of these conditions. Although definitive intervals for reassessment have not been established in the literature, there are three points that have informed our recommendations for reassessment intervals. First, rates of frailty and sarcopenia increase with worsening liver disease severity, so patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be assessed more frequently than those with compensated cirrhosis. Second, clinical trials of interventions that target muscle dysfunction, such as testosterone,(67) nocturnal nutritional supplementation(181) or exercise,(79,80) evaluated outcomes at intervals no shorter than 8 weeks but as long as 3, 6, and 12 months. Third, the recent International Conference of Frailty and Sarcopenia Research consensus guidelines on frailty screening and management in primary care recommended screening for frailty (in the general geriatric population) on an annual basis.(182) Based on these points, we recommend that reassessment of malnutrition risk (refer to the “Screening for Malnutrition Risk” section), frailty, and sarcopenia occurs at least annually for patients with well-compensated disease but as frequently as every 8-12 weeks among those with decompensated cirrhosis and/or those undergoing active management for malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia.

FIG. 3.

Algorithm for screening, assessment, and management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis.

Ideally, a multidisciplinary team, consisting of the patient’s primary care provider, gastroenterologist/hepatologist, registered dietician, certified exercise physiologist/physical therapist, and health behavior specialist—especially ones with expertise in managing patients with serious medical conditions, including advanced liver disease—would be involved with each level of management; but this may not be feasible in many practice settings. At a minimum, a patient should be referred to a registered dietician and a certified exercise physiologist/physical therapist if malnutrition, frailty, and/or sarcopenia are progressive despite primary and secondary preventive efforts.

Given the interdependence of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis, interventions that target one condition likely impact the other two conditions as well. Here, we provide pragmatic guidance for the management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis (Fig. 4). This information was intended for medical providers who are not specialists in nutrition or exercise to engage in primary and secondary prevention efforts (Fig. 2).

FIG. 4.

Diagnostic and management toolboxes with specific tools to facilitate diagnosis and management of malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis.

SCREENING FOR MALNUTRITION RISK

Multiple tools to screen for malnutrition have been evaluated in patients with cirrhosis.(183-187) Of these, the Royal Free Hospital Nutrition Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT) has been the most consistently associated with a diagnosis of malnutrition.(185-187) Patients are classified into three nutritional risk categories (low, moderate, and high) based on a combination of (1) presence of acute hepatitis or need for enteral nutritional support; (2) low BMI, unexplained weight loss, or maintenance of volitional nutritional intake; and (3) whether fluid overload interferes with ability to eat. Patients at high risk for malnutrition based on the RFH-NPT classification system have been shown to experience worse clinical outcomes including reduced survival, worsened liver function, and reduced quality of life.(187) Improvement in the RFH-NPT has been associated with improved survival.(187)

CIRRHOSIS-RELATED INTERVENTIONS

Disease-Specific

When possible, the cause of underlying chronic liver disease should be addressed. Eradication of chronic HCV is associated with a reduction in systemic inflammation, although levels of inflammatory biomarkers among individuals with advanced fibrosis remained elevated above levels measured in individuals who are not infected with HCV. Alcohol-associated skeletal myopathy may be partially reversible with alcohol cessation.(188) Although the exact mechanisms linking NAFLD with sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity are not well understood, the shared pathophysiologic processes of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance (that lead to both NAFLD and sarcopenia) suggest that interventions targeting NAFLD have the potential to prevent muscle loss.

Management of HE

A strong theoretical basis exists for the management of frailty and sarcopenia with agents that lower circulating blood ammonia concentration or reduce its production. In an animal model, combined use of rifaximin and L-ornithine L-aspartate lowered plasma and muscle ammonia concentrations and improved muscle mass and function.(189) These data raise the possibility that agents used to manage HE may have a role in prevention and treatment of sarcopenia as well. However, data specifically evaluating the benefit of HE management strategies on muscle contractile function or muscle mass in patients with cirrhosis are lacking. Carnitine plays a key role in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, a process impaired by ammonia and central to mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. In small studies, administration of L-carnitine was associated with dose-related lowering of blood ammonia levels, a lower rate of muscle loss, reversal of existing sarcopenia, and increased levels of physical activity(190-192) However, a recent systematic review did not show benefit of acetyl-L-carnitine for the treatment of HE,(193) so its availability for the management of frailty and/or sarcopenia in clinical practice may be limited.

Management of Ascites

Medical therapy of fluid retention should be optimized as ascites and edema lead to early satiety, limit exercise capacity, and compromise mobility. In some patients, therapeutic paracentesis may improve anorexia, satiety, caloric intake, and exercise tolerance as well as reduce REE.(52,53,194) Use of loop diuretics in patients with cirrhosis and ascites has been associated with loss of muscle mass, although this finding is limited to one study and has not been confirmed in other cohorts (and its use must be balanced against the risk of poorly controlled fluid retention).(195)

Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt for Management of Portal Hypertension

Placement of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in patients with portal hypertensive complications has been associated with marked improvement in body composition with gain of lean body mass, lower visceral fat, and an increase in total and fat-free muscle mass.(134,196-199) However, failure to increase muscle mass after TIPS is seen in up to one third of patients and is associated with increased mortality; baseline sarcopenia is a strong risk factor for failure to improve muscle mass after TIPS.(134,197) There is currently no evidence supporting the use of TIPS explicitly for the management of frailty and/or sarcopenia, although TIPS placement for standard indications (e.g., ascites, variceal bleed) may offer indirect benefits to the patient in the form of improvement in muscle mass.

Liver Transplantation for Management of Portal Hypertension

Liver transplantation is associated with improvement of frailty and sarcopenia in some, but not all, liver transplant recipients and often not to levels of age-matched and sex-matched norms.(99,101,168,200-203) In a prospective study that included 118 liver transplant recipients without HCC, the proportion of patients who were frail (Liver Frailty Index score ≥ 4.5) decreased from 29% pretransplant to 9% at 12 months after transplant, but only 30% met criteria for “robust” by a Liver Frailty Index <3.2.(99) Rates of improvement were related to the severity of pretransplant frailty,(99) highlighting a need both for pretransplant interventions to prevent or minimize frailty and for mechanisms to identify and transplant patients before they become severely frail. With respect to sarcopenia, two separate studies including 53 and 40 liver transplant recipients demonstrated rates of improvement in muscle mass between 25% and 34% after liver transplantation; however, one of the studies demonstrated that 26% developed new-onset sarcopenia after liver transplant but did not identify any specific predictors of posttransplant muscle loss.(201,203) Similar to our recommendations regarding TIPS, liver transplantation may offer indirect benefits to improving frailty and/or sarcopenia in recipients but cannot be recommended specifically for the treatment of these two conditions.

Although frailty and/or sarcopenia may improve after liver transplantation in some patients, both pretransplant frailty and sarcopenia are associated with adverse outcomes, including mortality after liver transplantation.(88,99,160-163,204) When considering the presence of frailty or sarcopenia in the assessment of a patient’s candidacy for liver transplantation, we recommend the use of objective, standardized metrics for frailty and/or sarcopenia for transplant decision-making. However, in the absence of data demonstrating specific thresholds of objective metrics of frailty or sarcopenia that balance risk of waitlist with posttransplant mortality, we do not recommend using frailty or sarcopenia as absolute contraindications against liver transplantation.

INTAKE-RELATED INTERVENTIONS

A personalized nutrition “prescription” should be provided to all patients with cirrhosis that is tailored to current nutritional status (i.e., a patient who meets criteria for frailty or sarcopenia should receive more intensive nutritional support to reach their targets than a patient who does not meet these criteria for malnutrition). Reassessment of nutritional intake should be repeated at regular intervals, with more frequent intervals reserved for those meeting criteria for frailty or sarcopenia at baseline and/or displaying worsening impairment of muscle contractile function or mass. If clinical deterioration or lack of improvement occurs despite target calorie and protein intake, additional causes should be considered, barriers addressed, and the nutrition prescription refined.

Energy Intake

One of the most important elements of developing a personalized intake prescription is to calculate the patient’s REE. Indirect calorimetry using a metabolic cart is the gold standard for measuring actual REE but is not widely available in all practice settings. Use of handheld calorimeters, a relatively inexpensive option to measure REE, has been validated in patients with cirrhosis to quantify REE and can be used at the bedside with high reliability in measuring REE (based on the gold standard of metabolic cart indirect calorimetry).(205,206) In the absence of indirect calorimetry, predictive equations (e.g., Harris-Benedict, Mifflin-St. Jeor) can be used to estimate an individual’s daily energy expenditure; but there is considerable interindividual variation in measured versus predicted values of REE.(33)

Studies evaluating energy expenditure in patients with cirrhosis have demonstrated that total energy expenditure ranges from 28 to 38 kcal/kg/day.(207-210) Based on these data, current nutrition guidelines for patients with chronic liver diseases and/or cirrhosis recommend a weight-based daily caloric intake of at least 35 kcal/kg/day.(211-213) In patients with fluid retention, dry weight can be estimated using subjective assessments based on either (1) postparacentesis weight or (2) subtracting a percentage of weight based on the amount of fluid retention (mild, 5%; moderate, 10%; severe, 15%; additional 5% taken off with bilateral pedal edema to the knees).(211) Although data are lacking on actual energy use among patients with cirrhosis across the spectrum of BMI, there is increasing acceptance of the need for BMI-adjusted energy intake goals. In light of this, weight-based energy intake recommendations may be modified to 25-35 kcal/kg/day for individuals with BMI 30-40 kg/m2 and 20-25 kcal/kg/day for individuals with BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2.(213) Further research is required to evaluate the accuracy of weight-based equations across BMI strata. Until that time, given their ease of use in a busy clinical practice for patients who are nonhospitalized and patients who are clinically stable, we support using BMI-adjusted, weight-based energy intake calculations to develop personalized daily caloric targets when indirect calorimetry is not available and use of predictive equations (e.g., Harris-Benedict) is not practical.

Sodium restriction may reduce the palatability of food, representing a barrier to adequate nutrition intake. In a study of 120 outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites, only 31% were adherent to a 2-g-sodium diet, and adherent patients had a 20% lower daily caloric intake.(9) When patients are prescribed a sodium-restricted diet, it should be balanced with educational resources that offer suggestions to improve diet palatability. Liberalization of sodium restriction should be considered if the patient is unable to maintain nutritional targets because of diet unpalatability.

Protein Intake

Studies dating as far back as the 1980s have established that patients with cirrhosis have increased protein needs.(210,214-216) In these studies, a positive protein balance was achieved above a protein intake of 1.2 g/kg/day(214,216); another study in patients with cirrhosis demonstrated the ability to use up to 1.8 g/kg/day of protein(210) A small randomized clinical trial of 30 hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and HE who received either protein restriction (0 g/day for the first 3 days, then gradual increase to 1.2 g/kg/day for the next 2 days) versus a normal-protein diet of 1.2 g/kg/day demonstrated accelerated protein catabolism in the protein-restricted group with no difference in evolution of HE between the two groups.(217) Based on these data, we recommend a protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg/day for adults with cirrhosis because it is safe, does not worsen HE, and minimizes protein loss compared with lower protein doses.(217,218) For children with cirrhosis, protein intake of up to 4 g/kg/day has been shown to be safe and effective at improving anthropometrics (based on a single study with 10 children).(219) Although the existing literature lacks consistency on whether the weight on which to calculate protein targets should be measured, dry, or ideal body weight, we recommend using ideal body weight (based on height) for pragmatic reasons.

Data evaluating the effect of the type of protein on nutritional status in patients with cirrhosis are limited. Several studies have demonstrated the benefits of vegetable and casein-based protein diets over meat protein diets to reduce HE.(220-222) In light of the limited evidence on malnutrition and the fact that meat may be a staple protein source for many patients, we currently do not recommend limiting the intake of meat-based protein sources. However, patients should be encouraged to consume protein from a diverse range of sources, including vegetable and dairy products when possible.

Some studies support the use of BCAA supplementation (e.g., leucine, isoleucine, and valine) in the management of cirrhosis-related complications, primarily HE, some of which evaluated the effect of BCAAs on nutritional status.(223-226) Two studies have demonstrated a reduction in clinical events and an improvement in quality of life with longer-term use of BCAAs.(223,225) However, in a meta-analysis of 16 RCTs evaluating BCAA supplementation (either orally or i.v.) in patients with HE, BCAAs had no effect on mortality, quality of life, or nutritional parameters(227) Children with chronic cholestatic liver disease have significantly higher BCAA requirements than healthy children.(228) One RCT of children with end-stage liver disease demonstrated benefit of BCAA-enriched nutritional support over a standard formula with respect to midarm muscular circumference (MAMC) and triceps skinfold thickness, but this study included only 12 children(229) Given that BCAAs are naturally present in protein-containing foods, we do not recommend long-term BCAA supplementation beyond recommended protein intake targets from a diverse range of protein sources.

Several other amino acid–based treatments have been studied in patients with cirrhosis, but there is currently insufficient patient-level evidence to definitively support their use for management of malnutrition, frailty, or sarcopenia in this population. These include ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (a metabolite of leucine),(230,231) acetyl-L-carnitine (an amino acid that has been shown to reduce blood ammonia levels),(193) and L-ornithine L-aspartate (a combination of two endogenous amino acids that reduces blood ammonia levels).(232)

Timing of Nutritional Intake

Timing of nutritional intake is essential to manage nutritional status in patients with cirrhosis. Prolonged periods of fasting should be avoided in cirrhosis, with evidence supporting the benefits on muscle mass of an early morning breakfast, late evening snack, and intake of small, frequent meals and snacks every 3-4 hours while awake.(181,233,234) A landmark study randomized 103 patients to daytime or nighttime supplemental nutrition of 710 kcal/day who otherwise had isocaloric, isonitrogenous diets.(181) Although most sustained in the Child-Turcotte-Pugh A patients, significant improvement in total body protein and fat-free mass was demonstrated in patients receiving nocturnal supplementation across all Child-Turcotte-Pugh classes. A diverse range of late-night snack options have been evaluated in the literature, with snacks varying from 149 to 710 kcal with varying carbohydrate and protein composition.(233) Given the range of personal habits regarding timing of regular food intake and preferences for types of snacks, we suggest a personalized approach to providing patients with recommendations on the timing of additional snacks (e.g., early breakfast versus late-evening snack) as well as snack content (e.g., protein bar, rice ball, yogurt).

Method of Nutritional Intake

A retrospective study of 75 patients with cirrhosis and known esophageal varices who underwent enteric tube placement demonstrated that 15% of patients experienced a gastrointestinal bleed within 48 hours of placement.(235) Higher MELD-Na score was a strong predictor of gastrointestinal bleeding. On the other hand, in a study of 14 outpatients with cirrhosis, continuous feeding through an enteric tube was associated with significant improvement of ascites, need for paracenteses, and handgrip strength without any reported complications.(236) Percutaneous gastrostomy placement is associated with a high risk of complications and mortality in patients with cirrhosis.(237) Based on these data, we recommend considering an enteric tube only in patients who have failed a trial of oral supplementation; we strongly advise against placement of percutaneous feeding devices in patients with cirrhosis and ascites.

Weight Loss With Obesity

In patients who are overweight/obese with compensated cirrhosis, weight loss of 5%-10% has been associated with reduced disease progression and reduction of portal hypertension(238) but the effects of intentional weight loss on nutritional parameters, muscle contractile function, and muscle mass are less well studied. In a study of 160 dieting older adults without liver disease, intentional weight loss was associated with decreases in lean mass and bone mineral density; but this was mitigated by resistance training.(239) Given the evidence supporting the role of adequate protein intake in the preservation of overall nitrogen balance (see the “Protein Intake” section), we advise caution when recommending weight loss in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or known sarcopenic obesity.(6) If weight loss through caloric restriction must be prescribed in patients with cirrhosis for clinical reasons (e.g., to reduce NASH progression, for transplant listing), we recommend (1) ensuring adequate protein intake (1.2-1.5 g/kg/day) and (2) combination with an exercise program.

Nutritional Intake in the Hospitalized Setting

Existing meta-analyses of nutritional supplementation in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis have not been able to demonstrate an impact on mortality.(240,241) However, a subgroup analysis of three studies evaluating oral nutritional supplementation alone demonstrated a benefit in mortality in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis (risk ratio, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.18-0.90).(241) The benefit of oral supplementation is further supported by an RCT of patients hospitalized with severe acute alcohol-associated hepatitis in which enteral versus oral supplementation did not offer a benefit in mortality but adequate oral intake (defined as ≥ 22 kcal/kg/day)—regardless of mode of administration—reduced mortality by 67% (0.19-0.57) compared with patients who consumed < 22 kcal/kg/day. One study conducted at a single Veterans Affairs medical center demonstrated that a cirrhosis-specific nutrition education intervention targeted to physicians and dieticians involved in caring for inpatients with cirrhosis resulted in increased nutritional intake and reduction in 90-day hospital readmissions.(243) We recommend that all hospitalized patients with cirrhosis receive formal consultation by a registered dietician within 24 hours of admission or, if not possible, with the RFH-NPT.(213) Barriers to oral intake (e.g., fasting time, HE, nausea) should be promptly identified and addressed. In patients who screen positive for malnutrition in whom barriers have been addressed and who are unable to meet their nutrition targets through oral intake alone, enteral nutrition should be considered within 48-72 hours of hospital admission.(244,245) One common barrier is prolonged periods of fasting that result from frequent nil per os (NPO) orders for procedures; strategies to minimize this fasting period or frequency of NPO orders (e.g., prebedtime snack, early-morning snack if the procedure will be in the late afternoon, consider advancing diet rapidly when there is no indication for NPO status) should be implemented.

In the intensive care unit (ICU) population, limited cirrhosis-specific data are available to guide energy targets. Indirect calorimetry is the gold standard for determining total energy requirements in this setting. However, given the limited availability of indirect calorimetry in many hospital settings, predictive or weight-based estimations of energy needs may be used, recognizing the potential underestimation of energy needs in light of the dynamic metabolic requirements and fluid overload in patients with cirrhosis who are acutely ill.(244) In patients who are critically ill, it is generally recommended to use higher protein goals, targeting 1.2-2.0 g/kg/day.(244,246,247) Again, the literature is not clear whether these recommendations are based on dry or ideal body weight; therefore, we recommend using ideal body weight for pragmatic purposes.

For hospitalized patients with cirrhosis who are unable to meet energy needs through oral intake alone, enteral feeding should be considered (time course has not been established in the literature); for those who are critically ill and unable to maintain volitional intake, enteral feeding should be initiated within 24-48 hours of ICU admission. A meta-analysis of 21 RCTs comparing early versus delayed enteral nutrition in all patients who are critically ill (including those with cirrhosis) demonstrated a significant reduction in mortality (relative risk, 0.70; 9% CI, 0.49-1.00) and infectious morbidity (relative risk, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.58-0.93) among those receiving early enteral nutrition versus delayed enteral nutrition or standard of care.(244) In one RCT of 136 patients with severe alcohol-associated hepatitis randomized (1:1) to intensive enteral nutritional support versus oral supplementation, enteral feeding had to be discontinued early in 49% of patients and was associated with three (4%) serious adverse events that were determined to be related to the intervention (one aspiration pneumonia, one decompensated diabetes, one severe worsening of HE); mortality benefit of supplemental nutrition was demonstrated only in patients ≥ 21.5 kcal/kg body weight/day, regardless of intervention arm. In two studies of early enteral feeding in patients with cirrhosis admitted with an esophageal variceal hemorrhage, placement of a nasogastric feeding tube was associated with a 10%-33% rate of rebleeding.(235,248)

Data around the use of parenteral nutrition in cirrhosis are limited, but meta-analyses in the general critically ill population have reported a higher incidence of hyperglycemia and sepsis (but an improvement in mortality when compared with patients receiving enteral nutrition).(249,250) Parenteral nutrition should be considered as a second-line option to enteral nutrition in patients who are unable to meet their nutritional requirements by oral intake alone and is strongly preferable to no nutritional supplementation in patients who are hospitalized and meet criteria for frailty or sarcopenia.

Micronutrients

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are common in cirrhosis regardless of etiology of liver disease and are particularly prevalent in patients with advanced disease, cholestasis, or acute illness.(251,252) Routine assessment for micronutrient deficiencies and appropriate repletion are recommended in patients with cirrhosis.(253) Recommendations for repletion of certain micronutrients that have been better studied in patients with cirrhosis are detailed in Table 4.(255-261) There is little evidence to guide longer-term maintenance dosing once deficiency has been corrected. Decisions for use of longer-term maintenance dosing will depend on assessment of whether the patient remains at nutritional risk (e.g., still consuming alcohol or with low oral intake).

TABLE 4.

Micronutrient Supplementation in Cirrhosis

| Symptoms of Deficiency | Repletion | Comments/Monitoring | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat-soluble vitamins | Vitamin A |

|

Vitamin A 2,000-200,000 IU/day PO according to deficiency syndrome and severity for 4-8 weeks(255,256) | |

| Vitamin D |

|

Repletion: 50,000 IU/week vitamin D2 or D3 for 8 weeks followed by maintenance of 1,500-2,000 IU/day(259) |

|

|

| Vitamin E |

|

α-Tocopherol acetate 400-800 IU/day PO |

|

|

| Vitamin K |

|

Phytonadione 1-10 mg PO, s.c.,or i.v. |

|

|

| Water-soluble vitamins | Thiamine, vitamin B1 |

|

Asymptomatic: thiamine 100 mg/day Suspected Wernicke encephalopathy: thiamine 500 mg i.v. 3×/day on days 1 and 2, then 250 mg i.v. 3×/day on days 3-5 |

|

| Niacin, vitamin B3 |

|

300-1,000 mg/day PO for deficiency states |

|

|

| Pyridoxine, vitamin B6 |

|

Vitamin B6 100 mg PO per day |

|

|

| Folic acid, vitamin B9 |

|

Folate 1-5 mg PO per day |

|

|

| Cobalamin, vitamin B12 |

|

Vitamin B12 1,000 μg i.m. monthly or 1,000-2,000 μg PO per day |

|

|

| Ascorbic acid, vitamin C |

|

Vitamin C 500-1,000 mg PO per day |

|

|

| Trace elements | Zinc |

|

30-50 mg elemental zinc PO per day(258) |

|

| Selenium |

|

50-100 μg/day PO |

|

|

| Copper |

|

2-4 mg i.v. for 6 days, followed by 3-8 mg per day PO until level normalization or symptom resolution(261) |

|

Abbreviation: PO, per os.

However, because vitamin and mineral status may not be regularly assessed in clinical practice because of competing demands from other cirrhosis complications (e.g., management of protein-calorie malnutrition, ascites, HE, etc.)—and multivitamin supplementation is inexpensive and essentially free of side effects—we support a pragmatic approach of an empiric course of oral multivitamin supplementation in patients with cirrhosis who display any evidence of frailty or sarcopenia, as has been proposed in the general population.(254)

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY–RELATED INTERVENTIONS

Physical activity–based interventions have been shown to improve muscle contractile function and muscle mass as well as cardiopulmonary function and quality of life in patients with cirrhosis.(78-81,238,262-265) The caveat to interpretation of these studies in this population is that they have been limited by small sample size and inclusion of primarily well-compensated patients.

There are three general principles to consider when recommending activity-based interventions for patients with cirrhosis: (1) assess frailty and/or sarcopenia with a standardized tool, (2) recommend a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises, and (3) tailor recommendations based on the physical assessment and reassessments.

Assess frailty and/or sarcopenia with a standardized tool. This should occur at baseline and longitudinally to assess response to the intervention. Improvement in frailty has been associated with lower rates of mortality compared with worsening of frailty in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.(92) Data are lacking on the potential benefits of changes in sarcopenia.

Recommend a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises. Activity-based interventions in patients with cirrhosis have ranged in duration from 8 to 64 weeks.(266) Exercise prescriptions can be guided by principles of frequency, intensity, time, and type, as detailed in the management toolbox (Fig. 4) and adapted from the American College of Sports Medicine.(267) Although the type of exercise (e.g., aerobic only or combination aerobic and resistance training) has varied in these studies, the general consensus is that the optimal activity-based intervention should include a combination of aerobic and resistance training. The theoretical framework for this recommendation is that aerobic training may address impaired muscular endurance and cardiopulmonary fitness, whereas resistance training specifically addresses skeletal muscle strength and mass.(263) Data on what constitutes an adequate level of aerobic activity in patients with cirrhosis are limited, although it is reasonable to follow Centers for Disease Control guidelines to achieve 150-300 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity exercise per week and muscle-strengthening exercises at least 2 days per week.(268) The use of technology, including fitness trackers, can provide more accurate and objective data on an individual’s actual physical activity better than self-report alone.(76) Smartphone-based fitness apps designed for persons with cirrhosis may have a role in facilitating increased exercise and activity in patients with cirrhosis.(269)